Memorandum by Posner, J

Public Court Documents

January 13, 1997

25 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Campaign to Save our Public Hospitals v. Giuliani Hardbacks. Memorandum by Posner, J, 1997. a3208da7-6835-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/25179b20-ebfa-482b-8659-9875d1504dd7/memorandum-by-posner-j. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

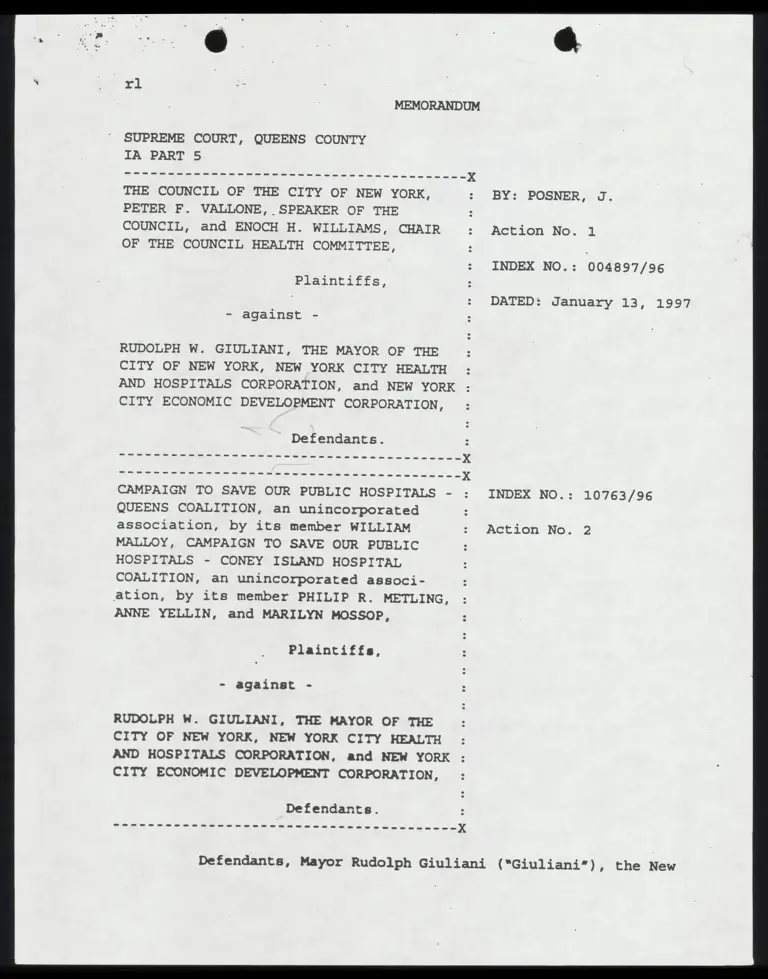

rl

MEMORANDUM

SUPREME COURT, QUEENS COUNTY

IA PART 5

ald a rt Xx

THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK, : BY: POSNER, J.

PETER F. VALLONE, SPEAKER OF THE :

COUNCIL, and ENOCH H. WILLIAMS, CHAIR : Action No. 1

OF THE COUNCIL HEALTH COMMITTEE, : :

INDEX NO.: 004897/96

Plaintiffs, :

: DATED: January 13, 1997

- against -

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HEALTH

AND HOSPITALS CORPORATION, and NEW YORK

CITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, :

Defendants.

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS - : INDEX NO. :

QUEENS COALITION, an unincorporated

association, by its member WILLIAM t.. Action No.

MALLOY, CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC

HOSPITALS - CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL

COALITION, an unincorporated associ-

ation, by its member PHILIP R. METLING,

ANNE YELLIN, and MARILYN MOSSOP,

Plaintiffs,

- against - :

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HEALTH

AND HOSPITALS CORPORATION, and NEW YORK :

CITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants.

10763/96

2

Defendants, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (“Giuliani”), the New

York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (*HCC”) and the New York

City Economic Development Corporation (*“NYCED”) have moved for

summary judgment. Plaintiffs in Action No. 1, The Council of the

City of New York (“Council”) and its principal leaders, and

plaintiffs in Action No. 2, The darpaian to Save Our Public

Hospitals, (“Campaign”) have cross-moved for summary fudonants

Both Action No. 1 and Action No. 2 were combined for joint trial,

without consolidation. (See Order of this court dated

September 18, 1996.) The parties all agree that there are no

issues of fact and that the legal issues are ripe for adjudication;

though, initially, defendants had raised the issue of "ripeness" in

their answer.

The conflict between the Mayor of the City of New York

and the Council of the City of New York is founded upon the age-old

controversy between the executive and legislative branches of

government. Fortunately, unlike the resolution adopted by the

protagonists (Cassius and Brutus) in Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar",

the authors of our State and Federal constitutions have wisely

established the third branch of government as arbiter of disputes

between the two.

IEE ISSUES

Plaintiffs in both actions originally petitioned the

2

® eo

court for a declaratory Sukumar interpreting Sect ich 7385(6) of

McKinney's Unconsolidated Laws of 1969. This section of the Health

and Hospitals Corporation Act (“HHC Act”) subjected the HHC's power

£0 sell ior lease its health facilities to the approval of the Board

of Estimate. When the Board of Estimate was abolished by the new

City Charter of 1989, no specific language was included to indicate

which person or entity inherited this particular power previously

exercised by the Board of Estimate. Furthermore, the New York

State Legislature has failed to exercise its power to amend the

statute substituting a specific officer or body to succeed the

Board. (See A.8896 and A.11048 of 1996.) Defendant Giuliani

claims that the new Charter intended that he alone should exercise

that power. Plaintiffs contend that the new Charter gives the

power to the Council acting in conjunction with the Mayor.

A second issue has arisen since November 8, 1996 when the

Board of Directors of defendant HHC voted to empower the HHC'’s

president to execute a lease with a for-profit corporation. Said

lease in effect turns over the operation of Coney Island Hospital

in toto to the lessee for eight (8) generations (198 years). As a

result of this action, plaintiffs amended their complaints to

include a new cause of action against HHC alleging it exceeded its

statutory powers.

IHE BACKGROUND

Defendant Giuliani took office as chief executive of the

City of New York in 1994. When he realized that he had inherited

a budget with fiscal problems (stretching back to the 70's), he

sought numerous ways to bring the City's expenses in balance with

its revenue. One of his proposals was for the privatization of the

City's public hospitals - a continuous drain on the City's

resources. It is his belief that a private for-profit corporation

can more efficiently run the City's hospitals. Whether the

plaintiffs agree or disagree with this philosophy is not the issue.

Nor is the debate over that philosophy one in which the court has

any right or power to immerse itself. To explore properly the

issues involved herein, it is necessary to step back and consider

the history of the HHC Act.

HISTORY

The New York State Constitution, Article Xvil, § 3

states:

“The protection and promotion of the

health of the inhabitants of the state

are matters of public concern and

provision therefor shall be made by the

state and by such of its subdivisions and

in such manner, and by such means as the

legislature shall from time to time

determine."®

Prior to 1970, in compliance with this constitutional

requirement, the City of New York constructed, maintained .and

operated hospital facilities providing care to residents of the

City, including those persons who could not otherwise Rtfcrd.

hospital services. In 1969, the New York State Legislature a,

the Health and Hospital Corporation Act ("HHC Act"), creating the

HHC and authorizing the City to transfer the municipal hospitals to

HHC for the purpose of continuing to fulfill the constitutional

mandates (L 1969, ch 101s, McKinney's Uncons Laws of NY §§ 7381 et

seq, the HHC Act).

| HHC's mission is to ensure the provision of "high

quality, dignified and comprehensive" care to the ill and infirm of

the City, and particularly chide persons who can least afford such

services (gee, McKinney's Uncons Laws of NY § 7382). HHC was

established at the behest of the City in part to permit independent

financing of municipal hospital construction and improvements and

to facilitate professional management of the hospital system.

HHC's creation was intended to overcome the "myriad of complex and

often deleterious constraints® which inhibited the provision of

care by the City in its own operation of the municipal health

system (McKinney's Uncons Laws of NY § 7382). To effect that goal,

S

* : = ®

the Legislature gave HHC a number of powers designed es provide the

"legal, financial and managerial" flexibility i. to cay :

out its purpose (McKinney's Uncons Laws of NY §§ 7382, 7385). It

was authorized "[t]o make and execute contracts and leases and all

other agreements or instruments necessary or convenient for the

exercise of its powers and the ENE nen: of its corporate

purposes" (McKinney's Uncons Laws of NY § 7385([5]). In addition,

HHC was granted the power "[t]o provide health and medical services

for the public directly or by agreement or lease with any person,

firm or private or public corporation or association through and in

the health facilities of the corporation #*** n (McKinney's Uncons

Laws § 7385(8]).

Nevertheless, some of the powers conferred on HHC were

constrained, and in some instances, subject to direct oversight and

continuing control by the City.!? Among these powers was the power

|

See, e.g., McKinney's Uncons Laws of NY § 7386 (1) (a); HHC

submits its program budget to the City in time for inclusion in the

Mayor's executive budget and culminates in the City budget which

the City Council has the sole authority to adopt;

§ 7386(2) (b); the City has the right to acquire any health

facility held by HHC;

§ 7386(7); HHC must exercise its powers in accordance with

policies and plans determined by the City;

§ 7390(S)-(8); HHC employee grievances are governed by NYC

Administrative Code;

§ 7385(19); HHC may use City agents, employees and facilities

6

relevant to the issues herein:

"To dispose of by sale, lease or

sublease, real *** property including but

not limited to a health facility, or any

interest therein for its corporate

purposes, provided, however, that no

health facility or other real property

acquired or constructed by the

corporation shall be sold, leased or

otherwise transferred by the corporation

without public hearing by the corporation

after twenty days notice and without the

consent of the board of estimate of the

Sity.”

(McKinney's Uncons Laws § 7385[6]).

(Emphasis added).

On July 1, 1970, in accordance with the HHC Act and with

the approval and authorization of the Board of Estimate, the City,

by Mayor Lindsay, and HHC entered into an agreement under which HHC

agreed to assume responsibility for maintaining and operating the

City's public hospitals. Eleven hospitals, included under that

agreement, have Sorted in operation since 1970.

In 1994, the City, through the Mayor's office, began

exploring the possibility of transferring the operation of three of

those hospitals, Coney Island Hospital (*CIH”), Elmhurst Hospital

Center and Queens Hospital Center (“the Queens Health Network”) to

private entities. J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., was retained by

subject to collective bargaining agreements and the Mayor's

consent.

Ug th : | i *

defendant EDC as financial advisor to prepare offering memoranda

for proposals to privatize the operations of the three hospitals

and to sublease their facilities.

In spring of this year, HHC began receiving proposals,

and on June 26, 1996, Peter J. CAEN Deputy Mayor of Zhe:

City, Dr. Luis R. Marcos, as President of HHC, and Steven Volla, as

Chairman of PHS New York Inc. ("PHS-NY") and of Primary Health

Systems, Inc. ("Primary") executed a letter of Yitanticaviing tor

negotiations to achieve a long-term sublease of property, plant and

equipment of CIH to PHS-NY, and a contract for PHS-NY to operate

CIH as a community based, acute care in-patient hospital during the

term of the sublease. On October 8, 1996, HHC and the New York

City Department of Health held a public hearing on the proposed

sublease of CIH. On November 8, 1996, the HHC Board of Directors

authorized and approved the sublease of CIH to PHS-NY for an

initial term of 99 years (and renewable by PHS-NY for an additional

95 year term). The sublease is rather unusual in that it recites

those service obligations being imposed upon PHS-NY, including that

PHS-NY take over HHC's operation of the hospital services and

provide access to health care to indigent persons, in addition to

the more typical tenant obligations.

Both plaintiffs claim that (1) any sale, transfer, leave

® | AREY

or sublease of any HHC facilities to private lessees requires the

approval of the Council pursuant to Unconsolidated Laws § 7385(6) ;

(2) any such disposition requires the application of and compliance

with the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure ("ULURP") process of

sections 197-c and 197-d of the New York City Charter. The

Coalition plaintiffs also originally claimed that defendants

violated section 197-b of the Charter by failing to submit their

plans for privatizing the hospitals to the New York City Planning

Commission and affected community boards and borough presidents.

On December 4, 1996, all parties stipulated, on the

record in open court, to permit plaintiffs in Actions No. 1 and 2

to amend their respective complaints to add a cause of action

against HHC asking the court to void HHC's action on November 8,

1996 as an ultra vires act.

Defendants served a second amended answer to each second

amended complaint denying various allegations and asserting

affirmative defenses based upon the failure to state a cause of

action and lack of ripeness, and sections 7385(6) and 7385(8) of

the Unconsolidated Laws.

At the outset, the affirmative defenses based upon

failure to state a cause of action are stricken. An affirmative

defense based upon the failure to state a cause of action cannot be

9

® eo

interposed in an answer, but must be raised by a mokion to dismiss

pursuant to CPLR 3211 (a) (7) (see, Propoco, Inc. v Birnbaum, 157 AD2d

774, 775).

The affirmative defense based upon lack of ripeness must

also be stricken. At the time of the commencement of the action,

the HHC Board of Directors had not yet considered the proposed

sublease of CIH, and an argument could have been made that the

suits were premature. Nevertheless, at this juncture, where the

HHC board has acted to approve the sublease, the issues raised by

the Council and Campaign plaintiffs are ripe for adjudication.

This issue will be dealt with after consideration of the issue of

the devolvement of the powers of the Board of Estimate (HHC Act

7385[6]).

IEE BOARD OF ESTIMATE ISSUE

The HHC Act elbresuly provides that the les may "dispose

of by sale, lease or sublease, real or personal property, including

but not limited to a health facility, or any interest therein for

ifs corporate purposes® (emphasis supplied) (McKinney's Uncons Laws

§ 7385(6]). Such provision goes on to condition the exercise of

that power upon the consent of the Board of Estimate of the City

10

9 Ti he

(emphasis added) .?

At the time of the passage of the HHC Act, the Board of

Estimate consisted of eight elected members; the Mayor, the City

Comptroller, the President of the City Council and the five Borough

Presidents. Each of the citywide officers had two oR and each

of the borough presidents had one vote. This voting distribution

of the Board of Estimate members was declared violative of the

constitutional requirement of one person, one vote (gee, Voriie

Board of Estimate, 592 F Supp 1462 [E.D.N.Y. 1984], affd 831 F2d

384, affd 489 US 688 [1989)).

As a consequence of such ruling, and the United States

District Court order that a plan be developed by the City to cure

the constitutional deficiency (gee, Morris v Board of Estimate, 647

F Supp 1463), the New York City Charter Revision Commission was

formed, with one of its objectives for Charter revision being to

build greater participation in policy debates and decisions (see,

Final Report of the New York City Charter Revision Commission -

3

The authority of the Board to approve or consent to terms of

leases of sales transactions was also recognized by the State

Legislature in other States laws, e.g., Urban Development

Corporation Act § 3(4), codified at Uncons Laws § 6253 (1); Not-

for-Profit Corporation Law § 1411: Racing, Pari-Mutuel Wagering &

Breeding Law §§ 607(1), (3).

11

% | i »

Tanna 1989-November 1989 p 4). Following the enactment on

November 7, 1989 at the general election of sweeping Charter

amendments Brobouat by the Commission, the Board of Estimate was

"abolished and its power distributed elsewhere.

Notwithstanding the abolition of the Board of Estimate,

: the requirement that the Board of Estimate give We natant to any

transfer of a health facility or real property by HHC remains "on

the books" (McKinney's Uncons Laws § 7385[b]) and the Legislature

has not taken the opportunity to amend it. However, the failure of

the Legislature to amend the section does not mandate a conclusion

that it prefers a statutory construction severing the consent

portion as obsolete. In fact, the contrary is true. The

Legislature, by not having acted to eliminate the "board of

estimate" language, can be said to have opted to allow the consent

power to devolve upon the body, agency or officer designated in the

revised Charter to succeed to the powers of the Board of Estimate.

The Charter itself contemplates this result.

Section 1152(e), adopted by the voters in 1989, as part

of the Charter revisions, in relevant part, provides:

the powers and responsibilities of the

board of estimate, set forth in any

state or local law, that are not

otherwise devolved by the terms of such

law, upon another body agency or officer

12

shall devolve upon the bodv, agencv or

officer of the city charged with

comparable and related powers and

responsibilities under this charter,

consistent with the purposes and intent

of this charter...."

(Emphasis supplied.)

By applying such "savings" provision to the HHC Act, the.

original intent of the Legislature (to allow a check on HHC's power

to lease or transfer a health facility or real property) may be

accomplished (see, McKinney's Statutes §§ 391-392, § 397; see also,

Matter of New York Pub, Interest Research Group v Dinkins, 83 NY2d

377, 386; Matter of Natural Resources Council v New York City Dept.

of Sanitation, 83 NY2d 215, 222; Ball v State of New York, 41 NY2d

617, 622). Moreover, none of the parties involved herein claim

that no consent by a city agency, body or officer is required.

This court concludes that section 7385(6) must be construed to

continue to retraite consent; the question to be resolved is which

Body, agency or officer, or combination thereof, has succeeded to

the Board of Estimate in this regard.

The Council plaintiffs urge that the consent power

granted the Board of Estimate in § 7385(6) has devolved upon both

the Council and the Mayor. They point to the fact that the powers

to consider land use effects and business terms have been split

under the Charter revisions between the Council, under section 197

13

°o a »

c of the Charter (“ULURP”), and the Mayor, under § 384 (a) of the

Charter, Yesnectively (see, Tribeca Community Assn. Inc. v New York

ey Supreme Court, Queens County, Index No.

20355/92, affd 200 AD2d 536, atipast dismissed 83 NY2d 905, lv to

appeal denied 84 NY2d 805). They also contend that neither the HHC

Act nor the Charter restricts the Council to ULURP considerations

only.

Defendants argue that because oi ote time of the HHC

Act's enactment, the Board of Estimate had the right to consider

business terms under the then Charter § 384 (a) and ULURP did not

yet exist, the Legislature intended that the Board of Estimate be

relegated to consideration of the business terms only of any sale

or lease of property held by HHC. According to defendants, such

consideration of business terms has been assigned to the Mayor

RENE pursuant to § 384 of the Charter, and the Council has

no role in the consent power of § 7385(6).

The HHC Act, however, did not provide guidelines or

limits on the type of issues the Board of Estimate could take into

consideration when exercising the consent power. By its silence,

the Act granted the Board of Estimate full authority to contemplate

at least those issues usually associated with property disposition,

including business terms and land use effects.

14

® | »

Defendants further argue that the Council has no land use

review role under the consent power of § 7385(6) because ULURP, as

the mechanism Zit the Council's exercise of land use review is

inapplicable to HHC. According to defendants, the "HHC Act

supersedes any Charter provision regulating its power to sublease,

citing Waybro v New York City Board of Estimate, 67 NY2d 349.

Waybro, however, is distinguishable from this case,

because unlike the statute at issue therein (the Urban Development

Corporation Act [L. 1968, ch 174, as amended], McKinney's Uncons

Law § 6251), nothing in the HHC Act indicates HHC has the authority

to override requirements of the local charter in relation to

disposition of health facilities or property (gee, Waybro v New

York City Board of Estimate, supra at 355; gee also, Connor v

Cuomo, 161 Misc 2d 889, 896). The HHC Act, by requiring consent

of the Board of Estimate under § 7385(6) for dispositions of

property, expresses, if anything, the contrary intent. Similarly,

if this court was to adopt defendants' reasoning, then it would

have to hold that the HHC Act supersedes even § 384 (a), the Charter

provision granting the Mayor the power to review business terms of

dispositions of City property. To the extent the parties agree on

anything, they agree that this section gives the Mayor the power

to review business terms of dispositions of City property,

15

including the HHC sublease.

Section 384 (a) of the Charter provides:

"No real property of the city may be

sold, leased, exchanged or otherwise

disposed of except with the approval of

the mayor and as may be provided by law

unless such power is expressly vested by

(Emphasis added.)

The section's language granting the Mayor the approval power,

however, includes the conjunctive "and," followed by "as may be

provided by law unless such power is expressly vested by law in

another agency." The phrase "as may be provided by law" can be

read without strain or force to include ULURP wherein the power

to review sales, leases and other dispositions of real property

of the City is bestowed upon the Council (gee, New York City

Charter §§ 197-c, 197-4).

ULURP was enacted in 1975, "in response to a perceived

need for informed local community involvement in land use planning,

for adequate technical and professional review of land use

decisions and for final decision making by a politically

accountable body, the City's Board of Estimate." (2 Morris, New

York Practice Guide, Real Estate § 20.04, p 20-47.) In its final

report, the Charter Revision Commission indicated that prior to the

1989 revision of the Charter, the Board of Estimate had "final

16

* jo

authority over land use decisions ***" and the Council "had no role

in the land use review process" (Final Report of the New York City

Charter Revision Commission - January 1989-November 1989, pp 7 and

19 respectively). It noted that "[t]he basic change made by the

1989 charter amendments vad re substitute the Council for the guard

as the final decision maker in land use," and that "because taoial

and language minority groups will enjoy greater representation on

the Council than they have had on the Board, they will be able to

exert more influence if there is conflict with the mayor on a land

use matter" (The Final Report, pp 20-21).

ULURP, as revised, in pertinent part, provides:

"§ 197-c. Uniform land use review

procedure. a. Except as otherwise

provided in this charter, applications

by any person or agency for changes,

approvals, contracts, consents, permits

or authorization thereof, respecting the

use, development or improvement of real

property subject to city regulation

shall be reviewed pursuant to a uniform

review procedure in the following

categories *** (10) Sale, lease (other

than the lease of office space),

exchange, or pther disposition of the

real property of the city." (Emphasis

supplied).

HHC has been held not to be an "agency" of the City (gee,

Brepnac v City of New York, S59 NY2d 791, 792), and the term

"person® is not specifically defined in § 197-c, or in the New York

17

: 6 : : PY

City Administrative Code concerning land use topics. Nevertheless,

§ 197-c of the Charter should be liberally construed (gee, Maudlin

v New York City Transit Auth., 64 AD2d 114, 177), and thus, HHC,

as a public benefit corporation, may be considered a "person" for

the purposes of ULURP (gee, General Construction Law §§ 37, 65) .

As for the meaning of "disposition," the term is not

defined by statute, charter or code provision. This court must

interpret the word. The word has been defined as "the act of

disposing, transferring to the care or possession of another. The

parting with, or alienation of, or giving up property." (Black's

Law Dictionary 471 [6th ed. 1990]). By applying this definition,

the court finds the sublease of CIH constitutes a "disposition"

under ULURP because it is a transfer of a real property interest,

as well as service duties from HHC to PHS-NY.

Defendants further argue that even assuming ULURP evinces

the partial devolvement of the consent power under § 7385(6) to the

Council, it cannot actually apply to the CIH sublease because ULURP

‘violates § 10(5) of the Municipal Home Rule Law. Section 10 (5)

states:

*e¢¢+ a local government shall not have

the power to adopt local 1daws which

impair the powers of any other public

corporation.”

18

The Court of Appeals has interpreted § 10(5) to provide that

public benefit corporations are exempt only from regulations which

would interfere with their purpose (gee, Levy v Citv Comm. on

Human Rights, 85 NY2d 740). Again, it is the HHC Act itself which

grants a check on HHC's authority to dtepohs oF real property,

albeit via the Board of Estimate, now a nonexistent body. As

explained above, the consent power of the Board of Estimate under

section 7385(6) has devolved to both the Council and the Mayor.

Hence, ULURP must be viewed as not impairing che exercise of HHC's

power to dispose of property by sublease.

Defendants alternatively contend ULURP is inapplicable

because the sublease of CIH is not the subject of any disposition

by the City, but instead, a disposition by HHC. They argue that

under traditional notions of property law, a lessee is free to

exercise possession and control over the property as against the

world, including the landlord. According to defendants, HHC is

legally allowed to sublease, and to require it to undergo ULURP

review would render its leasehold less significant. Charter §

197-c, however, is not restricted to dispositions by the City, but

instead, is applicable to any dispositions of the real property

of the City.

IEE ULTRA VIRES ISSUE

1s

The primary issue presented is whether the subleasing

of CIH, along with the wholesale turnover of HHC's service

obligations, constitutes an ultra vires act in violation of the

HHC Act.

As Mayor Lindsay pledged to the State Legislature, in

his letter to Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller,

"liln establishing a public benefit

corporation, the Citv is not getting out

of the hospital business. Rather it is

establishing a mechanism to aid it in

better managing that business for the

benefit not only of the public served by

the hospitals but the entire City health

service system. The municipal and

health care system will continue to be

the City's responsibilitv, governed by

policies, determined by the City

Council, the Board of Estimate. the

Mayor, and the Health Services

Administration on behalf of and in

consultation with the citizens of New

York City.”

(Letter of Mayor John V. Lindsay,

Governor's Bill Jacket, L. 1969,

ch. 1016.)

The Legislature, by enacting the HHC Act chose to rely upon such

pledges and created HHC, a public benefit corporation, to carry

out the City's constitutional responsibilities.

HHC, by contracting with PHS-NY by means of a 99 year

sublease, to have PHS-NY take over the operation of CIH, is

shirking its own statutorily imposed responsibility, without the

20

Legislature's approval. Although the HHC Act concededly allows

for provision of health and medical services "by agreement or

lease with any person firm or private or public corporation or

association, through and in the health facilities of [HHC] and to

make rules and regulations governing admissions and health and

medical services" (McKinney's Uncons Laws § 7385[8]), such

allowance may not be construed to permit the incongruous result

that HHC can delegate or shift all of its responsibilities to a

non-public entity as a means of "furthering its corporate

purposes." (McKinney's Uncons Law § 7385([8]). Moreover, that

reading would frustrate the purposes and obligations of the HHC

to the people of the City (see, Matter of New York Public Interest

Research Group, 83 NY2d 377, [City officials cannot frustrate a

legislative purpose by eviscerating an agency or group created by

statute for a public purpose]; Matter of Gallagher v Reagan, 42

NY2d 230, 234 ["(a) legislative act of equal dignity and import"

is required to modify a statute, and "nothing less than another

statute will suffice®)).

This situation 1s inherently different from one in which

a particular hospital property is no longer needed, usable or

affordable, requiring its closure by HHC (see, Matter of

Greenpoint Renaissance Enterprise Corp. v Citv of New York, 137

21

CY eum ; @®

AD2d 597; Raia Now. York fiey. Health 2 ms fala 419 F So

809; see also, Bryan v Koch, 627 F2d 612, affg 492 F Supp 212),

or even one in which a specific portion or service of a health

facility is leased, subcontracted or merged by HHC with a view to

saving costs or improving delivery of care. For in each of those

instances, HHC maintains the reins of control and decision-making,

and does not leave both the administration and day-to-day

operation entirely to someone else.

Put another way, HHC cannot put itself out of business

in relation to CIH by subleasing all of its assets and

staniterrins all of its duties, without the consent of the

Legislature, any more than a private corporation, by its Board of

Directors, could divest itself of its assets and property without

permission of its shareholders (gee, Business Corporation Law §

909 (a); Dukes v Davis Aircraft Prods. Co,, 131 AD2d 720, 721).

| The evidence presented on these motions makes it clear

that defendants seek to privatize all the HHC hospitals. It is

also obvious that the “turning over" of CIH to a non-public

corporation, is the first step towards defendants' ultimate goal

of disengaging the City from the municipal hospital system and

placing municipal hospital services in the hands of an outsider

or the private sector.? At the least, defendants seek to

"downsize" HHC and minimize its role (and therefore the City's

role), for an examination of the sublease terms reveals such

limited rorataed control by HHC as to raise the question of

whether HHC's continued existence could be justified if such

subleasing is repeated in connection with the other HHC hospitals.

For example, the sublease provides an arbitration process in the

event PHS-NY wishes to discontinue a core service, by which an

arbitration award can become binding on HHC. The Legislature

cannot possibly have intended or expected that by granting HHC the

right to enter into agreements or leases, HHC would be put into

a position where HHC's Board of Directors essentially stripped the

b |

"Mayor Rudolph Giulian: recently announced plans to sell

Coney Island Hospital and two other Queens hospitals into private

hands. Giuliani said he was worried about rising health-care

costs and deficits at city-owned hospitals, and wants to get the

city out of hospital business. *

(Newsday, March 5, 1995, emphasis supplied).

As the Mayor told the press:

"Twenty years from now the mayor of New York City will not

be standing here with New York City owning 11 acute-care

hospitals. That will not be the case. It is going to happen,

it's going to change. That change is either going to be forced

on us or we're going to guide it.°® .

(National Public Radio, Interview with Mayor Giuliani, Morning

Edition, September S, 1995.)

23

® »

corporation of its control over the carrying out of its duties.

The history of the creation of HHC is instructive. HHC

was borne out of the City's need to salvage a hospital system that

was floundering. If HHC likewise is confronted with a system

nearly drowning in red ink, defendants' response cannot be simply

to jump ship. They must go back to the Legislature, and seek an

amendment or repeal of the HHC Act, or devise some other plan for

managing the crisis.

By finding that HHC has domitted an ultra vires act in

entering into a sublease to privatize CIH, this court is not

attempting to second guess HHC or the other defendants ort

substitute its own beliefs for that of the HHC Board of Directors.

Instead, it is holding that HHC must give meaning to the intent

of the People as expressed through the State Legislature's

enactment of the HHC Act.

Accordingly, the summary judgment motions by defendants

In Action Nos. 1 and 2 are denied. The cross motions for summary

judgment by the Council plaintiffs in Action No. 1 and by the

Campaign plaintiffs in Action No. 2 are granted to the extent of

declaring that the subleasing of HHC facilitites requires the

application of ULURP and the approval of the Council, and further

24

8-5. ie @

declaring that the sublease of CIH to PHS-NY constitutes an ultra

vires act and violates the HHC Act.

Settle orders.

© ofe © © © © © © © © oo o

25