Frinks v. North Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Frinks v. North Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1972. 06cf877e-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/252e021b-bc0c-4512-afd7-eb25d4482182/frinks-v-north-carolina-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

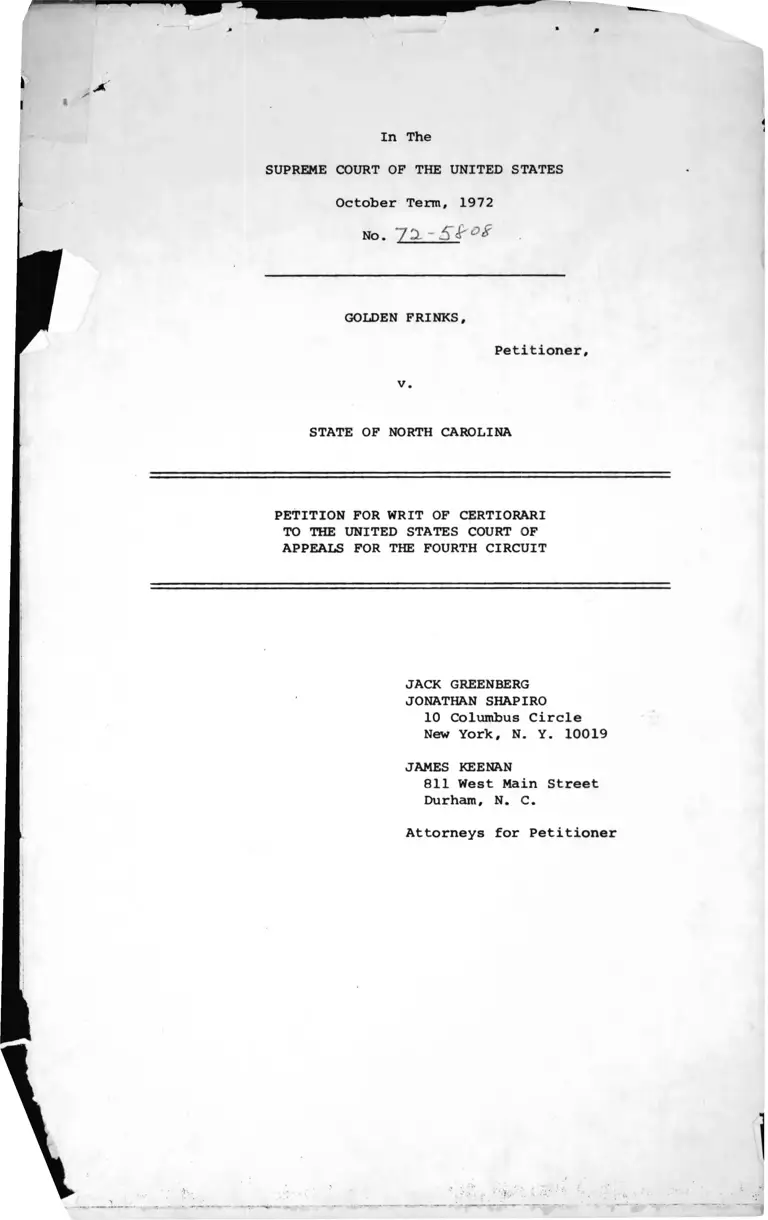

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1972

No. 7 Cl ~ S &

GOLDEN FRINKS,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

JACK GREENBERG

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

JAMES KEENAN

811 West Main Street

Durham, N. C.

Attorneys for Petitioner

V

I N D E X

Page

Opinion Below ........................................ 1

Jurisdiction ........................................ 1

Questions Presented .................................. 2

Statutes Involved .................................... 2

Statement of the C a s e ................................ 5

Reasons for Granting the W r i t ........................ 8

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted Because the

Decision of the Court of Appeals Seriously

Undermines the Protection Afforded the

Exercise of Civil Rights by This Court's

Decision in Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S.

780 (1966)................................... 8

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Resolve

the Conflict Between the Decision of the

Court Below and Decisions of the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.............. 13

Conclusion.......... 15

Appendix:

Opinion of the Court of A p p e a l s ................ la

Opinion of the District C o u r t .................. 20a

Table of Cases:

Achtenberg v. Mississippi, 393 F.2d 428 (5th Cir.

1967) 13,15

City of Baton Rouge v. Douglas, 446 F.2d 874 (5th

Cir. 1971)...................................... 13

Duncan v. Perez, 445 F.2d 557 (5th Cir. 1967) 15

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) . . . 2,8,9,10,11,12,

13,14

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966)............ 10

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 370 U.S. 306 (1965) . . . . 11

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U.S. 1 (1906)................ 11

United States v. McLeod, 385 F.2d 734 (5th Cir. 1967) . 15

►

1

i

Cases (continued) Page

Walker v. Georgia, 405 F.2d 1191 (5th Cir. 1969) . . . 13

Walker v. Georgia, 417 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1968) . . . 13,15

Wilson v. Republic Iron and Steel Co., 357 U.S. 92

(192.1) .......................................... 11

Wyche v. Hester, 431 F.2d 791 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . . 15

Wyche v. Louisiana, 394 F.2d 927 (5th Cir. 1967) . . . 13

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) 1

28 U.S.C. § 1443(1) ............................ 2,6,8,9

42 U.S.C. § 2000a (Civil Rights Act of 1964,

§ 2 0 1) ................................................ 2 ,3 ,6 , 8

42 U.S.C. § 2000a-2 (Civil Rights Act of 1964,

§ 203) 5,6,8,10,11,13

1 1

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1972

No.

GOLDEN FRINKS,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit entered on October 4, 1972.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is not yet reported

and is set forth in the Appendix (A. la). The opinion of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of North

Carolina is reported at 333 F. Supp. 169 (E.D. N.C. 1971) and

is set forth in the Appendix (A. 20a).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

was entered on October 4, 1972. Petitioner's time within which

to file a petition for writ of certiorari was extended until

December 3, 1972, by order of the Chief Justice dated

November 2, 1972. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Questions Presented

The Court of Appeals held that petitioner was not entitled

to an evidentiary hearing to prove the allegations of his

federal removal petition that state criminal prosecutions had

been commenced against him solely for the purpose of punishing

him for the exercise of rights secured by § 201 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.

1. Is this decision in conflict with this Court's decision

in Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966)?

2. Should the conflict between the decision below and

decisions of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit be

resolved in favor of the Fifth Circuit rule which entitles a

removal petitioner to such a hearing?

Statutes Involved

1. 28 U.S.C. § 1443(1) provides:

§ 1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or

criminal prosecutions, commenced in a State

Court may be removed by the defendant to

the district court of the United States for

the district and division embracing the

place wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or

cannot enforce in the courts of such State

2

a right under any law providing for the equal

civil rights of citizens of the United States,

or of all persons within the jurisdiction

thereof; . . .

2. 42 U.S.C. § 2000a (§ 201 of the Civil Rights Act of

1964) provides:

§ 2000a. Prohibition against discrimination or

segregation in places of public accom

modation— Equal access

(a) All persons shall be entitled to the full

and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facil

ities, privileges, advantages, and accommodations

of any place of public accommodation, as defined

in this section, without discrimination or segre

gation on the ground of race, color, religion, or

national origin.

(b) Each of the following establishments

which serves the public is a place of public

accommodation within the meaning of this sub

chapter if its operations affect commerce, or

if discrimination or segregation by it is sup

ported by State action:

(1) any inn, hotel, motel, or other

establishment which provides lodging to

transient guests, other than an establish

ment located within a building which con

tains not more than five rooms for rent

or hire and which is actually occupied by

the proprietor of such establishment as

his residence;

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunch

room, lunch counter, soda fountain, or

other facility principally engaged in

selling food for consumption on the prem

ises, including, but not limited to, any

such facility located on the premises of

any retail establishment; or any gasoline

station;

(3) any motion picture house, theater,

concert hall, sports arena, stadium or

other place of exhibition or entertain

ment; and

(4) any establishment (A) (i) which

is physically located within the premises

of any establishment otherwise covered by

3

this subsection, or (ii) within the premises

of which is physically located any such

covered establishment, and (B) which holds

itself out as serving patrons of such covered

establishment.

(c) The operations of an establishment affect

commerce within the meaning of this subchapter if

(1) it is one of the establishments described in

paragraph (1) of subsection (b) of this section;

(2) in the case of an establishment described in

paragraph (2) of subsection (b) of this section,

it serves or offers to serve interstate travelers

or a substantial portion of the food which it

serves, or gasoline or other products which it

sells, has moved in commerce; (3) in the case of

an establishment described in paragraph (3) of

subsection (b) of this section, it customarily

prevents films, performances, athletic teams,

exhibitions, or other sources of entertainment

which move in commerce; and (4) in the case of

an establishment described in paragraph (4) of

subsection (b) of this section, it is physically

located within the premises of, or there is

physically located within its premises, an

establishment the operations of which affect

commerce within the meaning of this subsection.

For purposes of this section, "commerce" means

travel, trade, traffic, commerce, transporta

tion, or communication among the several States,

or between the District of Columbia and any

State, or between any foreign country or any

territory or possession and any State or the

District of Columbia, or between points in the

same State but through any other State or the

District of Columbia or a foreign country.

(d) Discrimination or segregation by an

establishment is supported by State action

within the meaning of this subchapter if such

discrimination or segregation (1) is carried

on under color of any law, statute, ordinance,

or regulation; or (2) is carried on under

color of any custom or usage required or

enforced by officials of the State or political

subdivision thereof; or (3) is required by

action of the State or political subdivision

thereof.

(e) The provisions of this subchapter

shall not apply to a private club or other

establishment not in fact open to the public,

except to the extent that the facilities of

such establishment are made available to the

4

customers or patrons of an establishment within

the scope of subsection (b) of this section.

Pub.L. 88-352, Title II, § 201, July 2, 1964,

78 Stat. 243.

3. 42 U.S.C. § 2000a-2 (§ 203 of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964) provides:

§ 2000a-2. Prohibition against deprivation of,

interference with, and punishment

for exercising rights and privileges

secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l

of this title

No person shall (a) withhold, deny, or

attempt to withhold or deny, or deprive or

attempt to deprive, any person of any right

or privilege secured by section 2000a or

2000a-l of this title, or (b) intimidate,

threaten, or coerce, or attempt to intimi

date, threaten, or coerce any person with

the purpose of interfering with any right

or privilege secured by section 2000a or

2000a-l of this title, or (c) punish or

attempt to punish any person for exercising

or attempting to exercise any right or privi

lege secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l of

this title.

Pub.L. 88-352, Title II, § 203, July 2, 1964,

78 Stat. 244.

Statement of the Case

Petitioner Golden Frinks is a black civil rights worker

who has long been active in the "Wilmington Movement," an organ

ization of black citizens of New Hanover County, North Carolina,

which, through peaceful protest marches, demonstrations and

boycotts, has sought to eliminate racial discrimination and to

publicize the grievances of black citizens. On June 19, 1971,

petitioner sought to remove to federal court from the General

Court of Justice of New Hanover County two criminal prosecutions

5

charging him with the crimes of riot and inciting to riot.

Petitioner was charged with having incited and engaged in

riots in two different business establishments in Wilmington,

North Carolina, on June 9, 1971 (A. 8a-9a). In his verified

removal petition, petitioner alleged that both establishments

were places of public accommodation within the meaning of

§ 201 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (hereinafter referred to

as the "Act") and that the charges arose entirely out of his

peaceful attempts to exercise his right to nondiscriminatory

service there (A. 10a). He further alleged that the prosecu

tions themselves violated § 203 of the Act because they con

stituted an attempt to punish him for the exercise of this

right (A. 10a).

On motion of the State of North Carolina, the district

court remanded the prosecutions to the General Court of Justice

on October 29, 1971. Although the district court recognized

that the petition sufficiently alleged that petitioner was

being prosecuted because of his peaceful exercise of an equal

civil rights within the meaning of 28 U.S.C. § 1443(1), it

refused to hold an evidentiary hearing to resolve the disputed

factual issues of whether petitioner was being prosecuted

solely because of his peaceful attempt to obtain service or

because he had engaged in riotous conduct (A. 28a). Instead,

it assumed the truthfulness of the riot charges against peti

tioner and remanded the prosecutions to the state court on the

ground that petitioner had no federal right to engage in violent

conduct (A. 27a).

6

A divided Court of Appeals affirmed on much the same

reasoning. The majority concluded that for the purpose of

removal jurisdiction state charges which allege some element

of violence must be accepted as true and no evidentiary hear

ing is justified (A. 7a). Since "there is no federally

protected right to engage in a riot," the remand order was

affirmed (A. 4a).

Judge Sobeloff would have reversed on the ground that

petitioner was entitled to an evidentiary hearing to prove the

allegations of his petition. He contended that:

Whenever the state prosecutes a person and he

petitions for removal to the federal district

court, alleging that he is being prosecuted

solely for having peacefully exercised rights

immunized by Section 203(c), the district

court should hold a hearing to determine the

validity of the petitioner's claim. State

action cannot be shielded from scrutiny by a

prosecutor’s decision to choose one rather

than another appellation to denote an activity.

Only by requiring such an evidentiary hearing

can we insure that protected activity will not

be punished by criminal prosecution (A. 19a)

(emphasis in original).

7

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted Because the Decision

of the Court of Appeals Seriously Undermines the

Protection Afforded the Exercise of Civil Rights

by This Court's Decision in Georgia v. Rachel,

384 U.S. 780 (1966).

The decision of the Court of Appeals threatens the continued

vitality of civil rights removal jurisdiction as delineated by

this Court in Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966). In

Rachel, it was held that the requirements for removal under

28 U.S.C. § 1443(1) were met when the removal petitioner was

being criminally prosecuted in a state court solely because of

his exercise of a right secured by § 201 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964. In the present case, as in Rachel. petitioner

alleged that he peacefully sought to exercise his right to

obtain service in a place of public accommodation covered by

the Act and that the state criminal charges constituted an

attempt to punish him for the exercise of this right in viola

tion of § 203 of the Act.

Despite the fact that petitioner's claim is virtually

identical to the claim in Rachel, the Court of Appeals held

that petitioner was not entitled to removal because the conduct

with which he was charged— riot and inciting to riot— was not

protected by the Act. Although the court recognized that the

allegations of the removal petition raised a substantial factual

issue as to whether petitioner's federal rights were violated,

it held that he was not entitled to an evidentiary hearing for

8

the purpose of proving his claim and assumed the truth of the

criminal charges. According to the Court of Appeals, there

fore, removal is available only where a court can determine

that the petitioner is being prosecuted for conduct that is

protected by a federal equal rights statute solely upon the

basis of reading the criminal charges against him. Where,

as in the present case, the state merely alleges that the peti

tioner engaged in criminal conduct which is not so protected,

the petitioner is given no opportunity to prove that the

prosecution is merely a disguised attempt to punish him for

federally protected conduct.

But such a test for removal under 28 U.S.C. 1443(1) flies

directly in the face of Rache1 which explicitly recognized the

right of the removal petitioner to an evidentiary hearing to

establish the truth of the allegations of his petition. In

Rachel the petitioners were prosecuted for trespass based upon

their refusal to leave the restaurant at which they were seek

ing service when requested to do so. They alleged in their

removal petition that the prosecutions violated their rights

under the Act to nondiscriminatory service because they had

been refused service and asked to leave solely on account of

their race. This Court held that the prosecutions were

removable if the allegations that the denial of service was a

result of racial discrimination were true and that the peti

tioners were entitled to an evidentiary hearing at which they

would have the "opportunity to establish that they were ordered

to leave the restaurant facilities solely for racial reasons"

(384 U.S. at 805).

9

The Court of Appeals sought to distinguish the present case

from Rachel on the ground that when a person is charged with

trespass it is far more likely that he is actually being prose

cuted for conduct protected by the Act than when he is charged

with a crime of which violence is an essential element such as

riot and inciting to riot. Because of the "far greater prob-

bility" that the petitioner will be able to prove that he is

being denied rights protected by the Act when he is charged

with trespass,, an evidentiary hearing is justified (A. 6a) .

He is not entitled to such a hearing, however, where an essen

tial element of the charge against him is violence because as

an "exercise in probability prediction" it is much less likely

that he will be able to show that he is being prosecuted for

1/federally protected conduct (A. 6a).

Not only, as Judge Sobeloff points out, is the logic of

this distinction elusive, but it finds no support whatsoever

in Rachel. Rachel recognized that the removal of a state crim

inal prosecution depended upon the federal court being able to

make a "firm prediction that the defendant would 'be denied or

cannot enforce' the specified federal rights in the state

court" (384 U.S. at 804). Although past cases had required a

showing of a facially discriminatory state statute as a basis

for such a "firm prediction," Rachel held that an equally firm

1/ The Court of Appeals cites Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S.

808 (1966), in support of its denial of an evidentiary hearing

to petitioner (A. 5a). But, as Judge Sobeloff notes in his

dissenting opinion, Peacock stands only for the proposition

that removal is not available where the petitioner does not

invoke a federal equal civil rights statute containing a pro

vision, like that of § 203 of the Act, which prohibits any

prosecution for conduct protected by the statute (A. 13a).

10

prediction could be made by a showing that a pending prosecu

tion in and of itself would violate the petitioner's equal

civil rights. Since Hamm v. City of Rock Hill. 370 U.S. 306

(1965), interpreted § 203 of the Act as an absolute prohibition

of any prosecution of persons for the exercise of rights secured

by the Act, the mere pendency of the prosecution of the peti

tioners in Rachel violated their rights under § 203 and enabled

the federal court to make the "clear prediction" necessary to

support removal. Thus, the prediction that a federal court

must make under Rachel is of whether the petitioner's equal

civil rights will be denied in state court if the allegations

of his petition are true, and not, as the Court of Appeals

erroneously believed, a prediction of the likelihood that the

petitioner will be able to prove his allegations.

The difference is crucial. Rachel mandates the exercise

of civil rights removal jurisdiction whenever a person is

criminally prosecuted for the exercise of rights protected by

the Act, and directs a federal court to conduct a factual

inquiry to determine if he is being so prosecuted. Not only

does this procedure accord the respect that is due to the

important federal rights which are alleged to have been violated,

t*ut it is consistent with accepted federal practice in dealing

with removal petitions, whether in civil rights cases or

others. See Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U.S. 1, 33-35 (1906);

Wilson v. Republic Iron and Steel Co.. 357 U.S. 92, 97-98 (1921).

On the other hand, the decision of the Court of Appeals places

a staggering and unprecedented obstacle in the way of the

removal petitioner. For it requires him to somehow establish

11

the "great probability" that he will be able to prove that his

federal rights will be denied in the state court before he is

even entitled to an evidentiary hearing at which to prove the

allegations of his petition.

The practical effect, then, of the decision below is to

limit removal jurisdiction to prosecutions for trespass,

despite the removal petitioner's allegation that the prosecutor

is using a bogus criminal charge as a means of punishing peti

tioner's federally protected conduct. Such an interpretation

undermines this Court's decision in Rachel because it conditions

the important protection which removal affords to the exercise

of rights conferred by the Act upon the characterization given

by the prosecution to the conduct in question. Thus, the

arresting officer or the complainant can easily defeat the

removal of a prosecution designed to punish federally protected

conduct by charging the defendant with a crime of violence. As

Judge Sobeloff points out in his dissenting opinion:

If the State wishes to "punish" an individual

for exercising protected rights, and it is known

that a trespass prosecution will be removed to

federal court while a charge of inciting to riot

will not be removed, it seems more likely that

the State will charge the person with inciting

to riot rather than trespass" (A. 19a).

The decision of the Court of Appeals, therefore, eviscerates

one of the most effective remedies for the misuse of state crim

inal process to punish persons seeking to vindicate rights under

federal statutes providing for equal civil rights in one of the

two federal circuits where it is most needed. It severely

dilutes the rights which Congress specially sought to immunize

12

in § 203 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and all but nullifies

this Court's decision in Georgia v. Rachel, supra.

II.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Resolve

the Conflict Between the Decision of the

Court Below and Decisions of the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Attempts to nullify the protection of civil rights removal

jurisdiction by charging persons peacefully seeking to exercise

their rights under federal equal civil rights statutes with

crimes other than trespass have resulted in a line of deci

sions in the Fifth Circuit that is squarely in conflict with the

decision below. See City of Baton Rouge v. Douglas, 446 F.2d

874 (5th Cir. 1971); Walker v. Georgia, 417 F.2d 1, 5 (5th

Cir. 1969); Walker v. Georgia, 405 F.2d 1191 (5th Cir. 1969);

Wyche v. Louisiana. 394 F.2d 927 (5th Cir. 1967); Achtenberg

v. Mississippi. 393 F.2d 428 (5th Cir. 1967).

In Walker v. Georgia, 417 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1969), for

example, after the petitioner's conviction for trespass arising

out of a peaceful attempt to obtain service at a racially segre

gated place of public accommodation had been reversed by this

Court on direct appeal, she was reindicted for riot, malicious

mischief and other offenses against public order as well as for

trespass. The petitioner sought to remove these prosecutions

to federal court on the ground that they were based solely upon

the same peaceful attempt to secure nondiscriminatory service

for which she had previously been convicted of trespass.

Although the district court held that the petitioner was entitled

13

to remove the trespass prosecution on the authority of Rachel,

it remanded the other prosecutions to state court on the ground

that they did not charge conduct protected by the Act. The

Fifth Circuit reversed, holding that:

The petition for removal is to be determined not

by the appellation or euphemism of the charge,

but by what the movant was actually doing. As

we held today in Forman v. Georgia, the right

of removal of a state criminal prosecution has

not been restricted by the Supreme Court to the

small group of cases in which a state prosecu

tion for trespass seeks to forbid the enjoyment

of the right to equal accommodations guaranteed

under Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

[Citations omitted.] It is what the movant was

actually doing with respect to the exercise of

his statutory federally protected right, as

determined in a hearing for removal, that con

trols and not the characterization given to the

conduct in question by a state prosecution.

[Citations omitted.] It is well settled that

Section 1443(1) civil rights removal cases

require a sufficient evidentiary hearing on the

merits of the charges to determine whether the

defendants are actually being prosecuted solely

for peacefully attempting to gain equal access

to places of public accommodations. (417 F.2d

at 5.) (Emphasis in original.)

The conflict between the Fourth and Fifth Circuits in the

scope of protection afforded by removal jurisdiction should be

resolved in favor of the Fifth Circuit rule which entitles a

removal petitioner to an evidentiary hearing. The decision below

of the Fourth Circuit is based upon the demonstrably false

premise that criminal complaints which on

their face charge conduct that is unprotected by federal law

are likely to be true. The experience of the Fifth Circuit which

has frequently found on the basis of a factual inquiry that per

sons engaged in the peaceful exercise of federal rights have

been prosecuted in state courts on trumped up charges discredits

14

such an assumption. See, e.g., Walker v. Georgia, 417 F.2d 1

5 (5th Cir. 1969); Achtenberg v. Mississippi, 393 F.2d 428

(5th Cir. 1967); see also, Duncan v. Perez, 445 F.2d 557 (5th

Cir. 1967); Wyche v. Hester, 431 F.2d 791 (5th Cir. 1970);

United States v. McLeod, 385 F.2d 734 (5th Cir. 1967). The

Fifth Circuit rule, on the other hand, responds to the overriding

interest in insuring that the protection afforded the exercise

of important federal rights will not be circumvented by

sophisticated prosecutors and policemen.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, petitioner prays that his

petition for writ of certiorari be granted.

Respectfully submitted.

JACK GREENBERG

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

JAMES KEENAN

811 West Main Street

Durham, N. C.

Attorneys for Petitioner

15

X I d N 3 d d V

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 71-2125

Golden Frinks, Janice

Murray, and Anthony R.

Henry,

versus

Appellants,

State of North Carolina,

Appellee.

No. 72-1202

.) iI f f

George;Kirby,

) Appellant,

versus

State of North Carolina,

Appellee.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina, at Wilmington.

Algernon L. Butler, Chief Judge.

(Argued May 30, 1972 Decided October 4, 1972.)

Before SOBELOFF, Senior Circuit Judge, and WINTER and

CRAVEN, Circuit Judges.

James E. Keenan (Paul and Keenan on Brief) for Appellants

in No. 71-2125; Thomas F. Loflin, III (Loflin, Anderson

and Loflin on Brief) for Appellant in No. 72-1202; James

T. Stroud, Jr., District Solicitor, Fifth Judicial

District, for Appellee in Nos. 71-2125 and 72-1202.

CRAVEN, Circuit Judge:

Golden Frinks and George Kirby appeal from orders of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

North Carolina remanding to the North Carolina courts prose

cutions against them which they had removed to the federal

court pursuant to 28 U.S.C.A. § 1443(1). We think the district

court correctly found that their petitions did not allege

facts sufficient to sustain removal, or to require a hearing

on removability, and affirm.

Frinks and Kirby are charged by the State of North

Carolina with engaging in a riot in violation of N.C.G.S.

§ 14-288.2 (a) & (b) :

§ 14-288.2. Riot; inciting to riot;

punishments.--(a) A riot is a public dis

turbance involving an assemblage of three or

more persons which by disorderly and violent

conduct, or the imminent threat of disorderly

and violent conduct, results in injury or

damage to persons or property or creates a

clear and present danger of injury or damage

to persons or property.

(b) Any person who wilfully enages in

a riot is guilty of a misdemeanor . . . .

Frinks is charged also with inciting to riot in violation of

N.C.G.S. § 14-288.2(d):

(d) Any person who wilfully incites or

urges another to engage in a riot, so that as

a result of such inciting or urging a riot

occurs or a clear and present danger of a

riot is created, is guilty of a misdemeanor

The removal petitions rest on 28 U.S.C.A. § 1443(1), which

provides as follows:

§ 1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or

criminal prosecutions, commenced in a State

2a

court may be removed by the defendant to the

district court of the United States for the

district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied

or cannot enforce in the courts of such State

a right under any law providing for the equal

civil rights of citizens of the United States,

or of all persons within the jurisdiction

thereof . . . .

Except for references to the inciting-to-riot charges against

Frinks, the petitions for removal are identical and in perti

nent part are set out in Appendix A.

By way of summary, the petitions allege that Mr. Frinks

and Mr. Kirby have been engaged in lawful civil rights

marches, demonstrations and boycotts; that such activities

have been peaceful and nonviolent; that even so the State has

attempted to punish the petitioners for their having exercised,

i !or attempting to exercised, rights and privileges secured by

Title 2 of the 1964 Civil Rights Act; and that for the purpose

A

of chilling the exercise of such rights the State has falsely

charged petitioners with rioting in two business establishments

which are places of public accommodation within the meaning of

42 U.S.C.A. § 2000a(b).

Petitioners do not admit that they were present on the

premises of the two business establishments, but allege that

"if petitioners have ever been so present," their conduct has

been peaceful and not in violation of the laws of North

Carolina. Petitioners neither admit nor deny the charge

contained in the warrants that some 20 persons entered the

business establishments and threw merchandise on the floor and

overturned merchandise racks in violation of N.C G.S. § 14-288.2.

3a

Thus the defenses to the criminal charges, as alleged in the

petitions for removal, are that (a) these petitioners were

not present at the places of disturbance, or (b) if present,

these petitioners were nonviolent and did not participate

and did not participate in any riot that may have occurred.

We wholeheartedly agree with petitioners that they have

a federal right not to be prosecuted because of their race

for peacefully seeking to enjoy public accommodations. 42

U.S.C.A. §§ 2000a (a) & 2000a-2 (c); Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S.

306 (1964); Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966). But we

also agree with the State that there is no federally protected

right to engage in a riot.

[N]o federal law confers an absolute right on

private citizens— on civil rights advocates,

on Negroes, or on anybody else--to obstruct a

public street, to contribute to the delinquency

of a minor, to drive an automobile without a

license, or to bite a policeman. . . . [N]o

federal law confers immunity from state prose

cution on such charges.

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808, 826-27 (1966).

The problem is simply a factual one. Has the State

undertaken to persecute and oppress these petitioners because

of State antagonism to the federally protected right of all

persons to enjoy public accommodations, or has the State,

recognizing the supremacy of federal law, undertaken the prose

cutions only to protect the property and safety of its citizens

from the danger of riot?

Unfortunately, the facts are not ascertainable without

a hearing--either in a federal or state court. We agree with

Judge Godbold that "In Peacock the Supreme Court has directed

4a

the federal courts away from making factual inquiries approach

ing that of trial of the merits as an incident of determining

removability." Achtenberg v. Mississippi, 393 F.2d 468, 477

(5th Cir. 1968) (concurring in part and dissenting in part).

The practical reasons for such direction are compelling.

Mr. Justice Stewart, writing for the Court in Peacock, envi

sioned what might result:

On motion to remand, the federal court would be

required in every case to hold a hearing, which

would amount to at least a preliminary trial of

the motivationsof the state officers who

arrested and charged the defendant, of the

quality of the state court or judge before whom

' the charges were filed, and of the defendant's

innocence or guilt. And the federal court might,

of course, be located hundreds of miles away from

the place where the charge was brought. This

(hearing could be followed either by a full trial

■r:‘ in the federal court, or by a remand order.

Every remand order would be appealable as of

right to a United States Court of Appeals and,

if affirmed there, would then be reviewable by

petition for a writ of certiorari in this Court,

i If the remand order were eventually affirmed,

: iV̂ bere might, if the witnesses were still avail-

, ‘‘‘Sable, finally be a trial in the state court,

months or years after the original charge was

brought. If the remand order were eventually

reversed, there might finally be a trial in the

federal court, also months or years after the

original charge was brought.

Peacock, supra at 832-33.

This case is controlled by Peacock rather than Rachel.

Peacock, supra at 828, held:

Under § 1443(1), the vindication of the defend

ant's federal rights is left to the state courts

except in the rare situations where it can be

clearly predicted by reason of the operation of

a pervasive and explicit state . . . law that

those rights will inevitably be denied by the

very act of bringing the defendant to trial in

the state court. [emphasis added]

5a

Rachel represented direct confrontation between the 1964 Civil

Rights Act and the trespass laws of the State of Georgia.

Georgia law made it a criminal trespass offense to refuse to

leave facilities of public accommodation when asked to do so

by the owner or person in charge. The federal law invalidated

the Georgia trespass statute, at least where the request to

leave was invidiously motivated, and substituted "a right for

a crime." Hamm, supra at 314. Because the Georgia trespass

law was void in an invidious context, the federal rights of

those charged with its violation could have been denied by the

mere institution of charges. As Hamm made clear, the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 protects persons who refuse to obey an

order to leave public accommodations, not only from conviction

in state courts, but from prosecution in those courts.

A hearing was justified in Rachel by the great probability

that a federal right would be denied if the prosecution were

not removed. Such probability does not exist here. The 1964

Civil Rights Act does not in any sense void the anti-riot laws

of North Carolina. If these petitioners' federal rights are

in fact being denied, the denial is not "manifest in a formal

expression of state law." Rachel, supra at 803.

A white storekeeper may lawfully order Negro persons in

his store to discontinue destruction of his property whether or

not he is racially prejudiced. He may not, however, for racial

reasons lawfully order nonviolent persons to leave. As an

exercise in probability prediction, we may confidently assert

that there is a far greater probability that a trespass warrant

will be flawed by a policy of invidious discrimination than that

6a

a riot warrant will be similarly invalidated. This is so

because the riot warrant will be valid if violence (the essen

tial element) occurred, whereas the trespass warrant may be

void even though presence over the protest of the owner (the

essential element) is admitted. This is so, in turn, because

peaceful presence is protected and violence is not. Race,

color, or creed may well be a sufficient defense to a charge

of trespass, but are wholly irrelevant to a charge of rioting.

If these petitioners "are being prosecuted on baseless

charges solely because of their race, then there has been an

outrageous denial of their federal rights, and the federal

courts are far from powerless to redress the wrongs done to

them." Peacock, supra at 828. But removal is not the remedy,

see Peacock, supra at 828-30, unless we can clearly predict

from the operation of an explicit state law that federal rights

will inevitably be denied them, and that we cannot do.

AFFIRMED.

APPENDIX A

REMOVAL PETITION

JURISDICTION

1. Jurisdiction is conferred on the United States

District Court pursuant to the provisions of § 1443(1) of

Title 28, United States Code, this being an action in which

petitioners allege that they are being denied a right under

a law providing for equal rights, particularly § 2000a (a) of

Title 42, United States Code, and that they are denied or

cannot enforce said equal rights in the Courts of the State

of North Carolina.

PARTIES

2. Petitioners ... are Negro citizens of the United

States and the State of North Carolina.

3. Respondent is the State of North Carolina.

BASIS FOR REMOVAL

4. Petitioners are members and participants in a

coalition grouping of black citizens in the New Hanover

County area of North Carolina known as the "Wilmington

Movement." The purpose of said movement was to seek the

full enforcement and enjoyment of equal rights granted to

black citizens of the United States by the Civil Rights Act,

and in particular Titles II, IV and VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

5. As a means of publicizing their grievances, the

"Wilmington Movement," and in particular each of the peti

tioners, has engaged in protest marches, demonstrations

and boycotts. All such activities have been peaceful and

have specifically rejected violence to person or property

as a protest tactic. All such protests have been within

the ambit of protected free speech guaranteed to petitioners

by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

6. On or about the 10th or 11th day of June, 1971,

each of the petitioners was arrested and charged under the

North Carolina Anti-Riot Statute, see North Carolina General

Statute §14-288.2, with participation in a riot, and in the

case of petitioner Frinks, with the additional charge of

inciting to riot.

7. Specifically, petitioners . . . are charged with:

(a) Engaging in a riot on or about the

9th day of June, 1971, at the Piece Good Shops,

Azalea Shopping Center in Wilmington, North

8a

Carolina wherein it is alleged that some

twenty (20) persons did enter said business

and throw merchandise on the floor and over

turn merchandise racks, all in violation of

North Carolina General Statute §14-288.2(b)

(see Complaints and Warrants for Arrest at

tached as Exhibits 1, 2 and 3 to Petition);

(b) Engaging in a riot on or about the

9th day of June, 1971 at J. M. Fields, 3709

Oleander Drive, Wilmington, North Carolina

wherein it is alleged that some twenty (20)

persons did enter said business and throw

merchandise on the floor and overturn mer

chandise racks, all in violation of North

Carolina General Statute §14-288.2 (b) (See

Complaints and Warrants for Arrest attached

as Exhibits 4, 5 and 6 to Petition);

8. In addition, petitioner Frinks is charged with:

(a) Urging some twenty persons to engage

in a riot, to wit: a public disturbance

involving an assemblage of three or more per

sons at said Piece Goods Shop, it being alleged

r that petitioner Frinks led said group of per

sons into said business and urged the throwing

of merchandise on the floor and the turning

over of merchandise racks, all in violation of

North Carolina General Statute §14-288.2(d);

(see Complaint and Warrant for Arrest attached

as Exhibit # 7 to Petition);

(b) Urging some twenty persons to engage

in a riot, to wit: a public disturbance

involving an assemblage of three or more per

sons at said J. M. Fields, it being alleged

that petitioner Frinks led said group of per

sons into said business and urged the throwing

of merchandise on the floor and the turning

over of merchandise racks, all in violation of

North Carolina General Statute §14-288.2(d)

(See Complaint and Warrant for Arrest attached

as Exhibit # 8 to Petition).

9. Petitioners have advocated and personally enjoyed the

equal civil rights granted to them by Section 2000a (a) of

Title 42, United States Code, which guarantees that "all per

sons shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the

goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages and accom

modations of any place of public accommodation . . . without

discrimination or segregation on the ground of race . . . ."

10. The said Piece Goods Shop and J. M. Fields are public

accommodations within the meaning of Section 2000a (b) of Title

42, United States Code.

9a

11. The presence of petitioners on the premises of the

Piece Goods Shop or J. M. Fields, if petitioners have ever

been so present, has been peaceful and without acts or

actions in violation of the laws of the State of North Carolina

and accordingly is protected by Section 2000a(a) of Title 42,

United States Code.

12. The warrants for arrest and attempted prosecutions

of petitioners as heretofore alleged by respondent State of

North Carolina is an attempt to punish petitioners for the

exercise or attempt to exercise a right and privilege secured

by Section 201 of Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42

United States Code Section 2000a(a), and accordingly is spe

cifically prohibited by Section 203 of Title II of the 1964

Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000a-2(c).

13. Respondent has and is using unconstitutional statutes

or otherwise constitutional statutes in an unconstitutional

manner to deprive black citizens of the United States of rights

specifically granted to them by the Civil Rights Act of the

Congress of the United States. Prosecutions under said

statutes are forbidden and accordingly said black citizens,

including petitioners, cannot enforce in the Courts of the

State of North Carolina a right under a law providing for the

equal civil rights of citizens of the United States, and

accordingly are entitled to have their cases removed to the

Courts of the United States.

10a

SOBELOFF, Senior Circuit Judge, dissenting:

The State of North Carolina has charged Golden Frinks and

George Kirby, two individuals who in the past had been active

in peaceful civil rights demonstrations, with engaging in

riots at Piece Goods Shop and J. M. Fields in Wilmington,

North Carolina. Additionally, Frinks was charged with inciting

the riots.

The two men filed removal petitions under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1443 d),1 2 alleging that the prosecutions were an attempt by

the state to punish them for having exercised or attempted to

exercise rights and privileges secured by Title II of the 1964

, 2Civil Rights Act. They deny being present at the stores at

the time alleged, and alternatively contend that if present,

they were nonviolent and did not engage in any riot.

Two diametrically opposed claims are presented. On the

one hand, the State of North Carolina maintained that the

defendants are being prosecuted for entering the two stores and

tipping over clothing racks. On the other hand, Kirby and

Frinks deny these allegations of the state, and assert moreover

1. 28 U.S.C. § 1443(1) provides:

Any of the following civil actions or criminal

prosecutions, commenced in a State court may be

removed by the defendant to the district court

of the United States for the district and divi

sion embracing the place wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot

enforce in the courts of such State a right under

any law providing for the equal civil rights of

citizens of the United States, or of all persons

within the jurisdiction thereof.

2. 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000a - 2000a-6.

11a

that the charges were "trumped up" in order to punish them

for having exercised federally protected rights.

The majority recognizes the petitioners' federal right

not to be prosecuted for seeking to enjoy "public accommoda

tions."^ They point out additionally, however, that there is

no federally protected right to engage in a riot. The diffi

culty in the instant case is that the real facts cannot be

determined without an evidentiary hearing.

The question here becomes the important one under 28

U.S.C. § 1443(1) which this court expressly left open in South

Carolina v. Moore, 447 F.2d 1067 (4 Cir. 1971), "whether or not

a district court is properly required to resolve such a factual

issue [as violence] when considering a removal petition or

whether it may confine its view to the allegations of the state

charge if they unequivocally charge violent conduct * * *"

supra, 447 F.2d at 1071, n. 9. Today, this question is answered

but in a manner which accords inadvisable and unnecessary

deference to state prosecutions.

The majority would have a district court summarily dismiss

a removal petition without an evidentiary hearing whenever the

state has alleged a crime of which violence is an element. A 3

3. 42 U.S.C. § 2000a provides that:

All persons shall be entitled to the full and equal

enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities * * *

of any place of public accommodations * * * with

out discrimination or segregation on the ground of

race, religion, or national origin.

Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act is commonly called

the public accommodations section.

petitioner is thereby denied the opportunity to vindicate his

contention that, by means of a bogus prosecution, the state

is attempting to mete out punishment for the exercise or

attempted exercise of rights secured by the public accommoda

tions section of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The state

prosecutor is permitted to attach a convenient tag to a

defendant's conduct, and this labeling, rather than what the

individual was actually doing, becomes the test of removability

Such a result, according to the majority, is dictated by

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966).

Respectfully, I disagree. Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780

(1966), and not Peacock is controlling here. The petitioners

in Peacock and Rachel relied on entirely different rights. The

Supreme Court in Peacock recognized that the petitioners there

were bottoming their arguments on rights supposedly guaranteed

by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution and

the Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965. Peacock, supra, 384

U.S. at 811, n. 3. In the instant case, as in Rachel, the peti

tioners alleged violation of rights guaranteed by the public

accommodations section of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This

latter legislation, unlike the voting rights acts, contains a

specific prohibition against state action that "punish[es] or

attempts to punish."4 This significant difference was noted by

the Supreme Court in Peacock itself. The Court there declared

4. Section 203(c) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. § 2000a-2(c) declares that "No person shall punish or

attempt to punish any person for exercising or attempting to

exercise any right or privilege secured by section 2000a or

2000a-l of this title."

13a

that "Section 203(c) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 * * *

explicitly provides that no person shall 'punish or attempt

to punish any persons for exercising or attempting to exercise

any right or privilege' secured by the public accommodations

section of the Act. None of the federal statutes invoked in

the present case contains any such provision. See note 3 and

note 7 supra." Peacock, supra, 384 U.S. at 827 n. 25 (emphasis

added).

The majority apparently does not perceive it to be a

fundamental feature of this case that it deals with civil

rights legislation that bans "punishing" or "attempts to punish"

rather than legislation prohibiting "intimidating" or "attempts

to intimidate." Although New York v. Davis, 411 F.2d 750

(2 Cir. 1969), is not cited, my brethren apparently adopt

Chief Judge Friendly's equation for the purposes of removal

under § 1443(1) of the two types of statutes. Significantly,

after a year "of further study of the Peacock opinion," Judge

Friendly indicated second thoughts and emphasized that the ques

tion of whether the two types of statutes can be equated for

removal purposes was left open. The question left open by

5. Judge Friendly noted that:

[a]s a result of further study of the Peacock

opinion, we are not so sure as a year ago. New

York v. Davis, supra, 411 F.2d at 754, n. 3, that

civil rights statutes that ban intimidating,

threatening or coercing are to be equated, for

purposes of removal under § 1443(1), with a statute

that prohibits punishing or attempting to punish,

language that reads directly on the state. As

already noted, one of the two significant points

of distinction taken in Peacock was that "no

federal law confers immunity from state prosecution

14a

Judge Friendly is the central question imperatively demanding

an answer in the instant case.

To deny an evidentiary hearing to petitioners such as

Kirby and Frinks on their removal petitions solely because

the state charges them with a crime encompassing an element

of violence dilutes and severely limits the rights and privi

leges which Congress sought to specially immunize by

Section 203(c). If the allegations of the petitioners in

this case should prove correct, then the state is guilty of an

attempt to punish persons for the exercise of rights secured

by the public accommodations section— a result which Congress

specifically sought to forbid when it enacted Section 203(c).

5. (Continued)

on such charges," 384 U.S. at 827, 86 S.Ct. at

1812. Justice Stewart annotated this with a ref

erence to the provision in § 203(c) of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000a-2(c), that

no person shall "punish or attempt to punish any

person" for exercising rights to public accommoda

tions, a statement that "none of the federal

statutes invoked by the defendants in the present

case contains any such provision," and a cross-

reference to notes 3 and 7. Note 3 referred to the

provisions of the Voting Rights Acts of 1957 and

1965 described in the text, with a "See also" cita

tion to the latter. Commentators apparently believe,

although with regret, that the Court meant to con

fine the Rachel basis for removal to "unique" statutes,

see 384 U.S. at 826, 86 S.Ct. 1800, which in terms

prohibit prosecution. [Citations omitted.] On

the other hand, it is arguable that citation in a

footnote would be a rather elliptical way to decide

such an important question, and that the limitation

of removal to statutes using the words "punish or

attempt to punish" is confined to cases like Peacock

where the conduct was not within the protection of a

federal civil rights act when it occurred. We leave

the question open.

New York v. Horelick, 424 F.2d 697, 702-703, n. 4 (2 Cir. 1970).

15a

• » * " W ?

District courts must decide the truthfulness of removal peti

tions if Section 203(c) is to retain vitality and successfully

immunize from state interference this type of statutorily pro

tected conduct.

The Supreme Court in Rachel established a two-proned test

for removal under Section 1443(1), requiring that petitioners

demonstrate "both that the right upon which they rely is a

'right under any law providing for * * * equal civil rights'

and that they are 'denied or cannot enforce' that right in the

courts of [the state]." 384 U.S. at 788. The first prong of

this test is satisfied since the public accommodations section

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 creates rights "under any law

providing for * * * equal civil rights." Section 203 (c) enjoins

"any attempt to punish" persons for exercising these rights.

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306, 311 (1964) has inter

preted this section to include within its prohibition prosecu

tion in a state court. Hence, if the petitioners' allegations

in this case are found to be true and the state is indeed

attempting to punish them for exercising rights guaranteed by

the public accommodations section, then there is a "denial of

equal civil rights," the two prongs of the Rachel test are

satisfied, and removal is in order.

The existence of a conflict between allegations in a removal

petition and those in the criminal indictment is a rational

ground for holding a hearing to resolve the conflict; it is cer

tainly no reason for dismissing the petition out of hand. Only

an evidentiary hearing can insure that the state is not unduly

16a

interfering with specially protected civil rights. For "the

mere pendency of prosecutions [where such rights are involved]

enables the federal courts to make the clear prediction that

the defendants will be denied or cannot enforce in the courts

of [the] state, the right to be free of any 'attempt to punish'

them for protected activity. It is no answer in these circum

stances that the defendant might eventually prevail in the

state court. The burden of having to defend the prosecution is

itself the denial of a right explicitly conferred by the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 as construed in Hamm v. City of Rock Hill."

Rachel, supra, 384 U.S. at 805. Nor can it be said that the

interposition of a hearing would erode the state's prosecution.

If the state can establish a just basis for its prosecution, the

removal petition will be denied and the case will be remanded for

trial in the state court.

"The petition for removal [must] be determined not by the

appellation or euphemism of the charge but by what the movant

[petitioner] was actually doing." Walker v. Georgia, 417 F.2d 1,

5 (5 Cir. 1969). Whether the alleged offense be trespass as in

Rachel, or a crime encompassing an element of violence such as

aggravated battery. State of Louisiana v. Perkins, 335 F. Supp.

366 (E.D. La. 1971), the Fifth Circuit holds a hearing to deter

mine whether or not the charge is spurious, intended only to

punish the defendants for exercising protected rights. Walker,

supra; Whatley v. City of Vidalia, 399 F.2d 521 (5 Cir. 1965),

Wyche v. State of Louisiana, 394 F.2d 927 (5 Cir. 1967). I

think that Section 203(c) interdicts "attempts to punish" and

mandates an evidentiary hearing to defendants claiming that

they are being prosecuted for the exercise of rights under the

17a

public accommodations section. Any other reading of the

statute would emasculate the immunization clause of Section

203(c). Unless there is an evidentiary hearing, the defendant

charged with violent conduct will always be forced to submit

to state prosecution to vindicate his Title II rights. Such a

practice permits the characterization given by the prosecution

to the conduct in question to become the touchstone for removal

or non-removal.

It is true, as has been suggested, that the defendant may

ultimately prevail in the state courts, or that he has other

federal remedies including direct review by the Supreme Court

or habeas corpus. But the burden of having to defend a prose

cution is in itself a denial of a right immunized by Section

203(c). Rachel, supra, 384 U.S. at 780.

The majority asserts a distinction between this case and

Rachel in terms of probability. "A hearing," my colleagues con

cede, "was justified in Rachel by the great probability that a

federal right would be denied if the prosecution were not

removed." [Majority Opinion at p. 8.] But they argue in the

following paragraph that such probability does not exist in the

instant case:

As an exercise in probability prediction, we

may confidently assert that there is a far greater

probability that a trespass warrant will be flawed

by a policy of invidious discrimination than that

a riot warrant will be similarly invalidated. This

is so because the riot warrant will be valid if

violence (the essential element) occurred, whereas

the trespass warrant may be void even though presence

over the protest of the owner (the essential element)

is admitted. This is so, in turn, because peaceful

presence is protected and violence is not. (Majority

Opinion at p. 8.)

18a

The logic of the distinction adumbrated by the majority eludes

me. If the state wishes to "punish" an individual for exer

cising protected rights, and it is known that a trespass

prosecution will be removed to federal court while a charge

of inciting to riot will not be removed, it seems more likely

that the state will charge the person with inciting to riot

rather than trespass. Should we choose to analyze the instant

case in terms of probability of discriminatory state motive,

then it follows that if the allegations of the petitioner in

their removal petitions are true, just as in Rachel "the mere

pendency of [these] prosecutions enables the federal court to

make the clear prediction that defendant[s] will be 'denied

f ,■ U

or cannot enforce in the courts of [the] state the right to

be'free of any ’attempt to punish’ them for protected activity."

Veracity of the removal petition can be determined only in a

preliminary evidentiary hearing.

Whenever the state prosecutes a person and he petitions

for removal to the federal district court, alleging that he

is being prosecuted solely for having peacefully exercised

rights immunized by Section 203 (c), the district court should

hold a hearing to determine the validity of the petitioner's

claim. State action cannot be shielded from scrutiny by a

prosecutor's decision to choose one rather than another appella

tion to denote an activity. Only by requiring such an evidentiary

hearing can we insure that protected activity will not be punished

by criminal prosecution.

Therefore I dissent.

19a

OPINION OF THE DISTRICT COURT

GOLDEN FRINKS, et al., Petitioners,

v .

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA, Respondent.

No. 7188-CR.

United States District Court,

E. D. North Carolina,

Wilmington Division.

Oct. 29, 1971.

ORDER

BUTLER, Chief Judge.

Each of the petitioners was arrested on or about June 10,

1971, and charged in the General Court of Justice of New

Hanover County with violations of the North Carolina anti

riot statute. Prior to trial in the state court they filed a

petition for removal under 28 U.S.C. § 1443(1) in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of North

Carolina.

The North Carolina General Statute § 14-288.2 reads in

pertinent part: "(a) A riot is a public disturbance involving

an assemblage of three or more persons which by disorderly and

violent conduct, or the imment threat of disorderly and

violent conduct, results in injury or damage to persons or

property * * *. (d) Any person who wilfully incites or urges

another to engage in a riot, so that as a result of such incit

ing or urging a riot occurs or a clear and present danger of a

20a

riot is created, is guilty of a misdemeanor * * Petitioners

Frinks, Murray and Henry were charged in separate warrants with

engaging in a riot at Piece Goods Shop, Azalea Shopping Center,

Wilmington, North Carolina, and at J. M. Fields, 3709 Oleander

Drive, Wilmington, North Carolina, which "involved some twenty

persons entering said business and throwing merchandise on the

floor, and turning over merchandise racks." Petitioner Frinks

is charged in separate warrants with inciting a riot at Piece

Goods Shop, Azalea Shopping Center, and J. M. Fields, 3709

Oleander Drive, which "involved the said persons led by the

said defendant, entering the said business and throwing mer

chandise on the floor and turning over merchandise racks. As

the result of the urging and planning of the defendant, the

riot occurred."

The petitioners allege in their petition for removal that

"(t)he presence of petitioners on the premises of the Piece

Goods Shop or J. M. Fields, if petitioners have ever been so

present, has been peaceful and without acts in violation of the

laws of the State of North Carolina * * *." Petitioners allege

that they were exercising or attempting to exercise their rights

under Section 201 of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000a(a) which reads: "All persons shall be

entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services,

facilities, privileges, advantages, and accommodations of any

place of public accommodation, as defined in this section,

without discrimination or segregation on the ground of race,

color, religion, or national origin." Further, petitioners

allege that the "arrest(s) and attempted prosecutions * * *

21a

xs (sic) an attempt to punish petitioners for the exercise or

attempt to exercise a right and privilege secured by Section

201 of Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 United States

Code, Section 2000a (a), and accordingly is specifically pro

hibited by Section 203 of Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000a-2(c)." That subsection reads: "No

person shall * * * (c) punish or attempt to punish any person

for exercising or attempting to exercise any right or privilege

secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l of this title."

The State of North Carolina has moved to remand the cases

to the state courts.

A person is entitled to removal of a state prosecution

to the United States courts if a right phrased in terms of

racial equality will be denied him or rendered unenforceable

in the state court. The denial of equal rights must take place

in the state court and the denial must be manifest in a formal

expression of state law. It must also be clearly predictable

that equal rights will be denied or rendered unenforceable in

order for removal to be available. State of Georgia v. Rachel,

384 U.S. 780, 86 S.Ct. 1783, 16 L.Ed.2d 925 (1966); City of

Greenwood, Mississippi v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808, 86 S.Ct. 1800,

16 L.Ed.2d 944 (1966). The denial must result from the opera

tion of a pervasive and explicit state or federal law. That

the law might be selectively enforced against the petitioner by

certain officers is not a sufficient allegation under § 1443(1).

Virginia v. Jones, 367 F.2d 154 (4th Cir. 1966).

Title 42 U.S.C. § 2000a provides for equal rights in terms

of racial equality. Thus the right which the section guarantees

22a

enables citizens to assert the right with immunity from state

prosecution. It is clear, however, that only non-violent

attempts to gain admittance to places of public accommodations

defined by § 2000a are immunized. Hamm v. City of Rock Hill,

379 U.S. 306, 85 S.Ct. 384, 13 L.Ed.2d 300 (1964). "It has

been the uniform holding or assumption of all of the cases in

the lower courts that the Civil Rights Acts extend their pro

tections only to peaceful conduct." South Carolina v. Moore,

447 F .2d 1067, p. 1071 (4th Cir. 1971).

The precise question for determination by the court is

whether defendants, charged with inciting and/or engaging in a

riot, who allege in their petition that they were peaceably

exercising their rights to public accommodations are entitled

to have their cases removed under 28 U.S.C. § 1443(1). The

Fourth Circuit has recently reiterated that removal "is limited

to cases in which the charged conduct clearly enjoys federal

protection." South Carolina v. Moore, supra, 447 F.2d p. 1070.

The facts in the Rachel case, in which removal was allowed,

were markedly dissimilar to the case at bar. There, the peti

tioners entered a private restaurant and sought service. Service

was refused them and the petitioners were requested to leave.

They refused to do so. They were arrested and charged with the

crime of "Refusal to leave premises of another when ordered to

do so by owner or person in charge." Ga. Code Ann. § 26-3005

(1965 Cum. Supp.). The Supreme Court, citing Hamm v. City of

Rock Hill, supra, held that the Civil Rights Act had immunized

the very conduct with which the petitioners had been charged.

23a

Congress had substituted a right for a crime. Hamm v. City of

Rock Hill, supra. In the case now before the court, peti

tioners are charged with committing acts which are clearly

not protected by any Federal Civil Rights Act. Peacock assumes

that federal rights will be enforced in the state courts "except

in the rare situations where it can be clearly predicted by

reason of the operation of a pervasive and explicit state or

federal law that those rights will inevitably be denied by the

very act of bringing the defendant to trial in the state court."

384 U.S. at 828, 86 S.Ct. at 1812. Here, petitioners risk pun

ishment only if it be found beyond a reasonable doubt that they

did the acts charged in the warrants.

Judge Godbold, concurring in part, dissenting in part, in

Achtenberg v. Mississippi, 393 F.2d 468, 477 (5th Cir. 1968)

states:

Criminal charges are not removable on the

ground they are baseless and made to punish and

deter exercise of protected rights. Charges

are removable if quantitatively and qualita

tively they involve conduct coterminous with

activity protected under the Civil Rights Act,

i.e., "substitution of right for crime."

In Peacock the Supreme Court has directed

the Federal courts away from making factual

inquiries approaching that of trial of the

merits as an incident of determining removability.

In North Carolina v. Hawkins, 365 F.2d 559 (4 Cir. 1966),

cert. den. 385 U.S. 949, 87 S.Ct. 322, 17 L.Ed.2d 227, Chief

Judge Haynsworth, speaking for the Fourth Circuit Court of

Appeals, upheld an order of remand by the district court, noting

that the allegations in the petition were in contradiction of

the specific charges of the indictment. Judge Sobeloff concurred.

24a

but "not on the ground * * * that the allegations of the peti

tioner are 'in contradiction of the specific charges of the

indictment.' The test of removability is the content of the

petition, not the characterization given the conduct in ques

tion by the prosecutor." If the concurring opinion represented

a minority view on that point, then it is reasonable to con

clude that the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals considers such

a contradiction between the petition and indictment of some

significance. A warrant is not merely a "characterization" of

conduct by the prosecutor. It is more than that: it frames

the issues of the case and specifies the conduct which the

state seeks to punish. By so doing it effectively determines

what rights of the petitioner might be affected.

New York v. Davis, 411 F.2d 750 (2d Cir. 1969) points out

plainly that the line is drawn "between prosecutions in which

the conduct necessary to constitute the state offense is spe

cifically protected by a federal equal rights statute under the

circumstances alleged by the petitioner, and prosecutions where

the only grounds for removal are that the charge is false and

motivated by a desire to discourage the petitioner from exer

cising or to penalize him for having exercised a federal right.

* * * To apply this distinction requires the court to scrutinize

the state criminal statute and the charge thereunder as well as

the factual allegations in the removal petition * * *."

The Ninth Circuit, in California v. Sandoval, 434 F.2d 635

(1970), has stated that in order for removal to be available,

the petitioner must assert as a defense to the prosecution rights

given them by the federal statute protecting racial civil rights.

25a

The petitioner must also allege that the state courts will not

enforce the right and the allegation must be supported by ref

erence to a state statute or constitutional provision that

purports to command the state courts to ignore the federal

right. It cannot be seriously contended that the right to

seek service in a public accommodation is a defense to a charge

of violent and riotous conduct.

Petitioners allege that the State is using unconstitutional

statutes or constitutional statutes in an unconstitutional man

ner to deprive them, and other Negroes, of their civil rights.

Petitioners, admitting that they are being prosecuted for incit

ing and engaging in a riot, allege that such prosecutions are

forbidden. But there is no federal law restraining prosecu

tions for riot. See Wansley v. Virginia, 368 F.2d 71 (4th Cir.

1966). Presented with similar allegations referring to an anti

picket injunction in Baines v. City of Danville, 357 F.2d 756

(4th Cir. 1966), aff'd 384 U.S. 890, 86 S.Ct. 1915, 16 L.Ed.2d

996, the court said: "Neither does the contention that the

injunction is unconstitutional facially or as applied warrant

removal. The injunction is not obviously facially unconstitu

tional as applied to actual rioters. The constitutional question

if it arises, would come out of its application. Of course, it

would be unconstitutional if it became the basis of a convic

tion of a peaceful man whose conduct was within the protection

of the first amendment. This cannot be known until the cases

are tried." The court then concludes that such factual inquiries

should not be held since removability turns upon an obvious and

predictable denial by the state court.

26a

The court is satisfied that the cases at bar should be

remanded to the state court. While the petitioners arguably

had a right to be where they were, they had no right to commit

violent acts there, nor did petitioner Frinks have the right to

wilfully incite others to disorderly and violent conduct result

ing in damage to property. The elements of the charges in this

case are a public disturbance involving an assemblage of three

or more persons which by disorderly and violent conduct, or the

imminent threat thereof, results in injury or damage; and the

wilful incitation to such acts. The prosecution is directed

not at their presence in the store, but at their conduct in

the store. The Civil Rights Act is no defense to the charges,

and if petitioners are found not guilty it will be because they

did not commit the acts alleged, not because their acts were

protected.

The Fifth Circuit has held that an evidentiary hearing is

required when the petition alleges peaceable exercise of pro

tected conduct, regardless of the charges. This well-pleaded-

petition approach precludes consideration by the court of the

warrant or indictment or the statute. This approach to removal

has been rejected by the Ninth Circuit and the Second Circuit.

The Fourth Circuit has specifically reserved decision on the

point, but this court is of the opinion that the approach

adopted by the Fifth Circuit is not required by the Supreme

Court decisions. Indeed it would seem that the cases abjure

such a ready intrusion into the state judicial system. Where

the issue of removability is determined solely by whether or

27a

not an acknowledged right was violently exercised, this court

is not persuaded that it is more competent to determine that

issue of fact than a state court. If petitioners are to pre

vail, whether in the state court or in this court, it will be

because there is reasonable doubt that they did the acts charged,

i.e., engaged in rioting or inciting to riot. "Who among the

petitioners, if any of them, were rioters cannot be known until

there has been a factual hearing in every case. This is not

the sort of inquiry which ought to be required as an incident

of determining removability. If removability does not readily

appear without a factual inquiry tantamount to a trial on the

merits, removal should not be allowed." Baines v. City of

Danville, Virginia, 357 F.2d 756, 765 (4th Cir. 1966). Affirmed