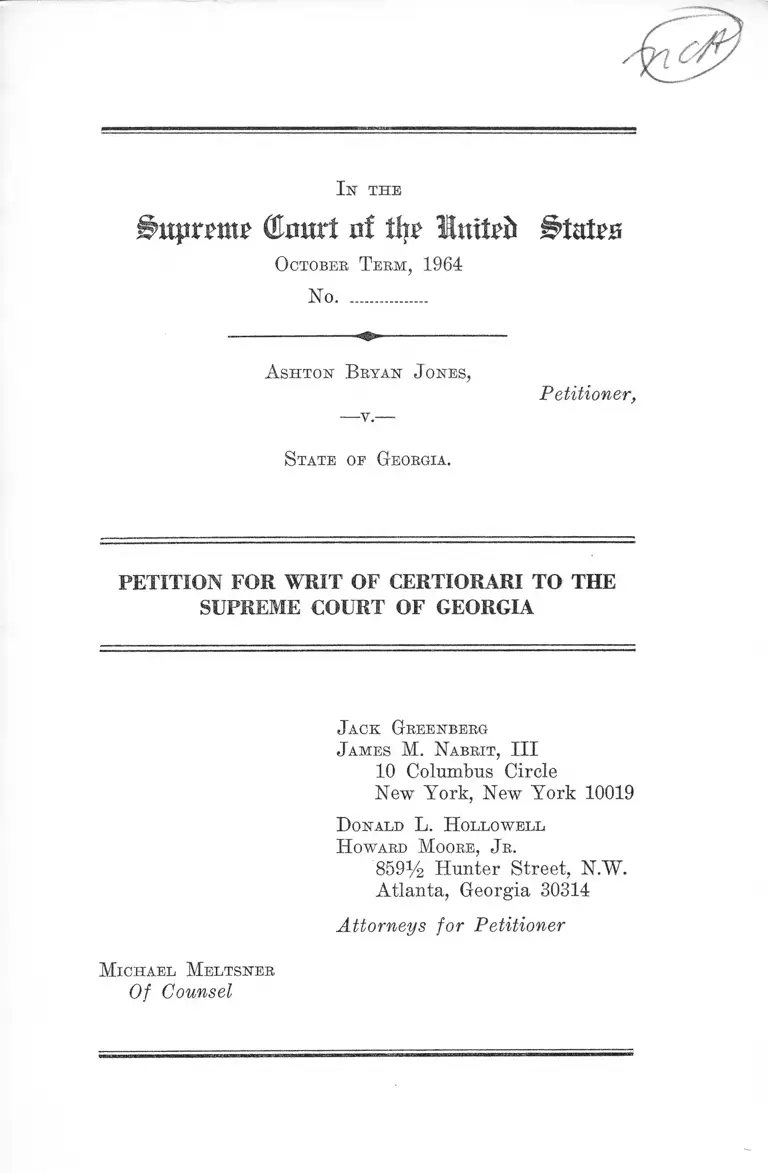

Jones v. Georgia Petition of Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jones v. Georgia Petition of Writ of Certiorari, 1964. 88302747-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2559a310-413a-4a98-83cd-51aea9c3e3b3/jones-v-georgia-petition-of-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

S u p r e m e (& m x t n f i h t H m tp ft S t a t e s

October Term, 1964

No................

Ashton B ryan J ones,

Petitioner,

■— v.—

State of Georgia.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Donald L. H ollowell

H oward Moore, J r.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioner

Michael Meltsner

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Citation to Opinion Below ............................ .......... . 1

Jurisdiction .............. 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 2

Questions Presented ........ ............ ..................... ........... 3

Statement ....................... 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below........................... .......... .......... ..................... 8

Reasons for Granting the Writ ...... ............................. 10

I. Petitioner’s Conviction Under a Vague and Over

broad Statute Violates Due Process of Law as

Secured by the Fourteenth Amendment ..... 10

II. Petitioner’s Conviction Was Affirmed Also on

the Ground That Personal Bias and Prejudice of

the Trial Judge Against Him Was Not a Basis

for Disqualification of the Judge in Violation of

His Right to Due Process of Law Under the

Fourteenth Amendment ............................ 14

A. The Supreme Court of Georgia Applied an

Improper Standard in Holding Bias and

Prejudice Was Not a Ground for Disquali

fication of the Trial Judge.......................... . 14

B. Petitioner Was Entitled to a Hearing on the

Motion to Disqualify or a Trial of the

Charges Against Him Before Another Judge 19

PAGE

Conclusion 21

11

A ppendix :

Opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia ...... la

Judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia ...... 12a

Denial of Rehearing by the Supreme Court of

Georgia ........ ......................................... .............. 13a

Table op Cases

Baggett v. Gullit. 377 U. S. 360 ................................... 10

Berger v. United States, 255 U. S. 22 ........................ 19

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U. S. 445 ..................... 10

Commercial Pictures Corp. v. Regents of University

of N. Y., reported with Superior Films, Inc. v. De

partment of Education, 346 U. S. 587 ..................... 10

Cooke v. United States, 267 U. S. 517 ........................ 20

Daniel v. State, 4 Ga. 844, 62 S. E. 567 (1908) .... 13

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 ____ 10,12,13

Folds v. State, 123 Ga. 167, 51 S. E. 305 (1905) ___ 13

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 ............................... 13

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ...................... ..10,11,13

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U. S. 717 .................................... . 18

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 303 U. S. 444 ....... . 10

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451......... .............. 11

Minter v. State, 104 Ga. 743, 30 S. E. 989 (1898) ......... 13

N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415........................ 12

Nichols v. State, 103 Ga. 61, 29 S. E. 431 (1897) .......... 12

Re Murchison, 349 U. S. 133 ................................... 18, 20

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 723 .................. ......... 18

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U. S. 534 ........................ 19

PAGE

I l l

Sacher v. United States, 343 U. S. 1 ........... ........... ..... 20

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 ...................... ..... 11

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ......... ............ ...... 13

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ............................11,12

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U. S. 510 ....... ........................... 18

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81 .. 10

United States v. Wood, 299 U. S. 123 ....... ... ............. 19

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ...................... .....10,11

T able of Statutes

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1257(3) ....... 1

United States Code, Title 28, Section 144................. 19

Georgia Code Annotated, Section 26-6901 ........2, 3, 7,10

Georgia Code Annotated, Section 24-102 ............2, 8, 9,17,

18,19

Other A uthority

Amsterdam, “The Void for Vagueness Doctrine in the

Supreme Court,” 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) .... 11

PAGE

In t h e

tour! of tty ImtTft

October Term, 1964

No.............. .

Ashton Bryan J ones,

Petitioner,

State of Georgia.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia entered in

the above entitled case April 9, 1964, infra, p. 12a, rehear

ing of which was denied on April 21, 1964, infra, p. 13a.*

Citation to Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia is re

ported a t ----- - Ga. ----- , 136 S. E. 2d 358 (1964), and is

set forth in the Appendix hereto, infra, pp. la-lla.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was

entered April 9, 1964, infra, p. 12a. Motion for rehearing

was denied by the Supreme Court of Georgia on April 21,

1964, infra, p. 13a.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and

* On July 8, 1964, Mr. Justice Goldberg signed an order extend

ing petitioner’s time for filing petition for writ of certiorari to and

including September 18, 1964.

2

asserting here deprivation of rights secured by the Con

stitution of the United States.

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves the following statutes of the

State of Georgia:

GA. CODE ANN. §26-6901. Interfering with, reli

gious worship.—Any person who shall, by cursing or

using profane or obscene language, or by being intoxi

cated, or otherwise indecently acting, interrupt, or in

any manner disturb a congregation of persons law

fully assembled for divine service, and until they are

dispersed from such place of worship, shall be guilty

of a misdemeanor.

GA. CODE ANN. §24-102. When judicial officer dis

qualified.—No judge or justice of any court, no or

dinary, justice of the peace, nor presiding officer of

any inferior judicature or commission shall sit in any

cause or proceeding in which he is pecuniarily inter

ested, nor preside, act, or serve, in any case or matter,

when such judge is related by consanguinity or affinity

to any party interested in the result of the case or

matter, within the sixth degree, as computed according

to the civil law, and relationship more remote shall not

be a disqualification; nor in which he has been of coun

sel, nor in which he has presided in any inferior judica

ture, when his ruling or decision is the subject of re

view, without the consent of all parties in interest:

Provided, that in all cases in which the presiding

judge of the superior court may have been employed

3

as counsel before Ms appointment as judge, he shall

preside in such cases if the opposite party or counsel

agree in writing that he may preside, unless the judge

declines so to do: and Provided further that no judge

or justice of any court, no ordinary, justice of the

peace, nor presiding officer of any inferior judicature

or commission shall be disqualified from sitting in any

cause or proceeding because of the fact that he is a

policyholder or is related to a policyholder of any

mutual insurance company which has no capital stock.

But nothing in the last proviso shall be construed as

applying to the qualifications of trial jurors.

Questions Presented

Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment right to

due process of law is violated:

1) by a Georgia statute which effectively prohibits ad

vocacy of church desegregation under a broad and

indefinite proscription of “interfering with religious

worship”?

2) by a decision of the Georgia Supreme Court that

under Georgia law personal bias and prejudice of the

trial judge toward the accused are never grounds for

disqualification ?

Statement

Petitioner, Reverend Ashton Bryan Jones, a 67-year-old

ordained white minister, attempted to attend the First

Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia with Negro companions.

He was arrested and convicted of violating Ga. Code Ann.

§26-6901, “interfering with religious worship.”

4

Events of Sunday M orning, June 30, 1963

At about 10:00 A.M. on June 30, 1963 (R. 365) petitioner

(R. 210, 211), together with a white girl and a Negro boy,

arrived at the Fourth Street entrance of the First Baptist

Church (R. 364) to attend the morning service (R. 233).

Petitioner and his companions were in ordinary dress

(R. 119, 181) but Reverend Jones was informed by an

usher that the main auditorium was open only to him, and

not to his Negro companion (R. 365), the church’s policy

being to seat “other than white people” in a lower, over

flow auditorium (R. 258, 365).

Reverend Jones refused to enter the church without the

Negro youth (R. 368-369) and remained in the vestibule

while people entered, asking them not to worship on a

segregated basis (R. 369):

I smilingly said to them, were you coming in to

worship in a segregated church, you see people out

there wanting to come in, certainly you must be trying

to worship a segregated God.

There is a conflict in the testimony concerning petitioner’s

conduct while in the vestibule. Mr. H. E. Watts, Chairman

of the Hospitality Committee for the First Baptist Church

(R. 223) testified that he addressed the entering congrega

tion in a “coarse and raucous voice” (R. 223). Reverend

Jones, however, testified that his tone was conversational:

It was about the same as I am testifying now, I don’t

think it was any louder, I didn’t even raise my voice

any louder as I made the comment to the people, some

of them, that I felt would accept the comment in the

manner and spirit in which I was making it—that this

is a segregated church, don’t you know this is not

right.. . . (R. 373).

5

After attempting and failing to gain admission at the

Peachtree entrance (R. 371), petitioner and his compan

ions sat down on the church steps to protest the exclusion,

and to pray (R. 315, 372). They remained on the church

steps until the congregation had left (R. 379). Once again

there is a discrepancy in the testimony concerning the cause

and the nature of the disturbance which ensued. Taylor

Washington, the Negro companion of petitioner, testified

that petitioner was accosted by an usher who said: “ You’re

the minister that has been in jail about these sit-in demon

strations” (R. 306), and who then proceeded to drag peti

tioner, an elderly man (R. 364), by the leg, down the stairs

(R. 307), tearing his trousers1 (R. 309) and causing peti

tioner to cry out “help police” (R. 308). Police had been

observing the activity from across the street (R. 375, 376).

The same incident is described by Mr. Watts:

“ . . . one of the ushers just touched him on the elbow,

just very deftly as you might touch an old lady help

ing her across the street, something like that, just

touched him on the elbow with his hand and he imme

diately dropped right down on the steps and sprawled

out there and yelled, help, help” (R. 224).

Petitioner testified to a second attack by an usher as

he was stepping onto church property (R. 377-378) after

having chatted with the policemen observing from across

the street (R. 376, 377). Petitioner sat down on the ground

and eventually the usher ceased dragging him (R. 377,

378). Watts, however, testified that he left the church after

hearing a noise outside and discovered petitioner lying

alone on the sidewalk, crying for help (R. 224-225).

1 A photograph of the torn trousers was introduced into evidence

at pp. 429, 450, of the Record.

6

Events of Sunday Evening

Around 6:00 P.M. that evening (R. 379), petitioner and

his companions, dressed appropriately (R. 291) and joined

by a young Negro girl (R. 312), returned to the church to

attend the evening service (R. 313, 380). They were pre

vented from entering by ushers who blocked the entrances

(R. 313, 380). Petitioner and his three companions then

moved to the sidewalk where they began to pray (R. 283,

318, 382-383). While thus engaged in prayer, a church

deacon unsuccessfully attempted to kick petitioner (R.

319).

After the prayer petitioner and his companions went

to the vestibule of the church (R. 286, 384), where they

encountered ushers who pushed them back out. A dis

interested witness, Jack D. Worth of Emory University,

who was filming the incident for WSB-TV (R. 278, 292)

described the occurrence:

Q. Did anything happen that you wouldn’t normally

expect to happen on church property? (R. 284)

A. Well, the only thing that you might classify as that,

after Reverend Jones and his three companions

had entered the building . . . (R. 285).

* # # # *

A. The door opened and the young Negro woman, com

panion of Reverend Jones, came tumbling out of

the door and fell on the steps (R. 286).

The young Negro woman, Miss Smith, testified that she

had been pushed by an usher (R. 348, 384). She subse

quently returned to the vestibule where Reverend McClain,

Pastor of the Church (R. 190), was criticizing the group

for its presence at the church and threatening to call the

police (R. 386). Reverend McClain then pushed Miss

7

Smith, in the direction of the door (R. 349-350). The

group then sat down on the porch of the church (R. 387),

read a portion of the scripture (R. 389), and was walking

away from the church when two plainclothesmen came and

arrested petitioner (R. 390).

The testimony of Mr. Worth concerning petitioner’s

conduct upon being arrested corresponds with that of the

defense. Worth testified that the policemen held peti

tioner’s arms and pulled him away with his heels dragging

on the ground (R. 288). At no time did Worth hear peti

tioner address the policemen loudly (R. 288-289) or begin

to walk and then drop to the ground or act violently (R.

295-296). The state’s witness, Mr. Bailey, testified that upon

being arrested, petitioner began to holler and flail (R. 272).

Mr. Worth testified that while observing the incident,

he had been threatened by members of the congregation

(R. 297-298), and that he had been restrained from taking

some pictures (R. 299).

There was no testimony that religious worship had

been “interrupted” by petitioner, and the only evidence

of “disturbance” was the testimony of Watts and Bailey

as to loud noises (R. 224, 256).

Petitioner was indicted by the Grand Jury of Fulton

County for the misdemeanor of interrupting and disturbing

religious worship in violation of Ga. Code Ann. §26-6901

“by loud talking, shouting, and by sitting on the floor of

said Church and by otherwise indecently acting” (R. 1).

In the Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia, Judge

Durwood T. Pye, presiding, petitioner was convicted and

sentenced to the maximum misdemeanor sentence: twelve

months upon the public works, six months in jail, and a

fine of one thousand dollars ($1,000.00) (R. 3, 4). After

conviction, bail was set at $20,000.00 (R. 20). TJnable to

8

make bail, petitioner remained in jail for approximately

six months (Bill of Exceptions, 1).

On appeal, the Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed peti

tioner’s conviction and sentence in the Superior Court,

infra, pp. la-12a.

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

Before pleading to the indictment, petitioner, relying,

inter alia, on the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States, filed a “motion to disqualify or

recuse” the Superior Court Judge, the Honorable Durwood

T. Pye, on the grounds of bias and prejudice (R. 5-6, 43-

45). Judge Pye overruled the motion (R. 76). Petitioner

assigned this ruling as error in the Supreme Court of

Georgia (Bill of Exceptions, 6, 7) but his Fourteenth

Amendment claim was rejected by that court, infra, pp.

la-2a:

Ga. Code Ann. §24-102 provides the circumstances un

der which a judge of the Superior Court may be dis

qualified. This Code section does not provide that bias

or prejudice is a ground to disqualify him from pre

siding in the case. The statutory grounds of disquali

fication contained in this section are exhaustive.

Before trial, petitioner demurred generally (R. 89-90)

challenging both the statute under which he was indicted

and the indictment as “so vague, indefinite and ambiguous”

(R. 8) that they failed to give him reasonable notice of the

charges against him and the acts or conduct constituting

the crime in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States (R. 8-9). The gen

eral demurrer was overruled (R. 90). After trial, peti

9

tioner again challenged the statute as violating the due

process clause a s:

. . . so vague, incomplete and indefinite as to be in

sufficient to place the defendant upon notice of the of

fense for which he was charged . . . and said statute

is so broad and inclusive and devoid of any reasonable

standards that it punishes innocent conduct as well as

guilty conduct. . . (R. 38).

On appeal to the Supreme Court of Georgia, petitioner

asked reversal of his conviction on the basis of vagueness

and indefiniteness of the statute and also alleged violation

of rights of free speech, expression and association as

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment (Rill of Ex

ceptions, 3, 4). The Supreme Court held Ga. Code Ann.

§24-102 “satisfies due process requirements,” infra, p. 4a:

. . . “Indecently acting” must be taken in the compre

hensive sense and include all improper conduct which

interrupts or disturbs a congregation of persons law

fully assembled for divine worship. Any person of

common intelligence . . . may determine whether the

particular acts and conduct charged him with improper

conduct, i.e., indecent acting.

10

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Petitioner’s Conviction Under a Vague and Overbroad

Statute Violates Due Process of Law as Secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment.

Petitioner was convicted for violating Ga. Code §26-6901:

Interfering with religious worship.—Any person who

shall, by cursing or using profane or obscene language,

or by being intoxicated, or otherwise indecently acting,

interrupt, or in any manner disturb, a congregation of

persons lawfully assembled for divine service, and un

til they are dispersed from such place of worship,

shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.

Petitioner was not charged with violating the specific

prohibitions of the statute, but convicted under the catch

all phrase: “otherwise indecently acting” (R. 459). Such

language, unconstitutionally vague and indefinite on its

face,2 is particularly offensive to the requirements of due

process when used, as here, to regulate the delicate balance

between freedom of speech and protection of the right to

worship.

2 Compare “unreasonable charges” of United States v. L. Cohen

Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81; “unreasonable” profits of Cline v. Frink

Dairy Co., 274 U. S. 445; “reasonable time” of Herndon v. Lowry,

301 U. S. 242; “sacrilegious” in Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 303

U. S. 44; “so massed as to become vehicles for excitement” (a

limiting interpretation of “indecent or obscene”) of Winters v.

New York, 333 U. S. 507; “immoral” of Commercial Pictures

Corp. v. Regents of University of N. Y ., reported with Superior

Films, Inc. v. Department of Education, 346 U. S. 587; “an act

likely to produce violence” in Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S.

229; “subversive person” in Baggett v. Bullit, 377 U. S. 360.

11

It is clear that petitioner’s purpose was to advocate

ideas; namely, the evils of segregation and the immorality

of Christians who exclude Negroes from worship (R. 369,

426). When free expression is involved, the vice of a

vague statute is not only that one cannot predict the con

duct which is criminal, cf. Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S.

451, but that the vagueness and breadth of the statute will

unduly burden protected speech.3 The case at bar exempli

fies the danger of permitting an indefinite statute to regu

late speech.

Examination of the record shows that petitioner quietly

addressed members of the church as they entered (R. 369,

373), that any loud noises were cries for assistance when

he was under assault (R. 308, 364, 377, 378), and that his

lying on the floor was in protest of his being kicked,

grabbed, beaten, and dragged down the steps (R. 283, 318,

382-83, 387-89). The evidence most favorable to the state in

dicates that petitioner threw himself on the floor and

shouted without provocation (R. 224, 225). This sweeping

statute permits prejudiced and discriminatory state en

forcement to hide under such a contested factual dispute.

Regardless of the view one takes of the actual events,

conviction under the catch-all phrase ‘‘otherwise indecently

acting” cannot be sustained, for such language necessarily

inhibits exercise of free speech and renders the statute

unconstitutionally vague on its face.4 In appraising the

3 See Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 97, 98; Herndon v.

Lowry, 301 U. S. 242; Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507; Smith v.

California, 361 U. S. 147; Amsterdam, “The Void for Vagueness

Doctrine in the Supreme Court,” 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67, 80-82

(1960).

4 Petitioner, moreover, need not prove that his conduct could not

be proscribed by a different statute:

An accused, after arrest and conviction under such a statute,

does not have to sustain the burden of demonstrating that the

12

inhibitory effect of such a statute, “this Court has not hesi

tated to take into account possible applications of the

statute in other factual contexts besides that at bar.”

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 432.

What are such different factual contexts? Had petitioner

limited his protest to a peaceful demonstration outside the

church, his activity clearly would be constitutionally pro

tected. See Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229, but

the statute, by its terms and as construed by the courts of

Georgia, applies to such protected activity. Moreover, as

consistently construed by the Supreme Court of Georgia,

“otherwise indecently acting” covers any “improper con

duct” which in any manner disturbs religious worship,

infra, p. 4a:

[T]he words “indecently acting” must be taken in

the comprehensive sense and include all improper

conduct which interrupts or disturbs a congregation

of persons lawfully assembled for divine worship.

“Improper conduct” seems to be determined solely by the

effect of the activity on the congregation:

“ [I]ndecently acting [can] signify any conduct which,

being contrary to the usages of the particular class or

worshippers interferes with their service, or is annoy

ing to the congregation in whole or in part . . . ”

Nichols v. State, 103 Ga. 61, 29 S. E. 431 (1897).

In Nichols v. State, supra, the defendant was speaking

“between a talk and a whisper” but his conduct was in

cluded within the term “indecently acting.” In another

state could not constitutionally have written a different and

specific statute covering his activities. . . . Thornhill v. Ala

bama, 310 U. S. 88, 96, 98.

13

case, one who discharged a gun near a church was guilty,

apparently, without proof that he intended to disturb

worship. Folds v. State, 123 Ga. 167, 51 S. E. 305 (1905).

The statute applies even if only one person is disturbed,

Daniel v. State, 4 Ga. 844, 62 S. E. 567 (1908), and after

the congregation has dispersed from the church. Folds v.

State, supra; Minter v. State, 104 Ga. 743, 30 S. E. 989

(1898).

Any peaceful protest against segregation outside a seg

regated church easily falls within these standards. Fur

ther confusion is introduced by the Georgia Supreme

Court’s finding that:

Any person of common intelligence (and particularly

one who claims to be an ordained minister) may deter

mine whether the particular acts and conduct charged

him with improper conduct, i.e., indecent acting (infra,

p. 4a).

What to many may be a decent and honorable exercise of

free speech may be considered by others the basest of con

duct ; what may be indecent and improper to many may fall

well within the protections of the Federal Constitution.5

It is the task of the state, not that of “any person of com

mon intelligence” to draw statutes which strike the balance

between individual freedom and needs of the state.

The following facts stare anyone in the face who would

seek to protest segregation of churches: Petitioner, a

67-year-old minister, was arrested during such a protest

and convicted on highly conflicting evidence of “otherwise

indecently acting.” He was sentenced to one year at hard

labor, six months in jail, and a $1,000.00 fine, the maximum

5 Compare conduct in Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242; Hague v.

C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496; Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1; Edwards

v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229.

14

for misdemeanor offenses (R. 3, 4). After conviction he

was subjected to enormously high bail provisions and was

forced to serve six months while his constitutional argu

ments were being heard in state courts.

In light of this vaguely written and broadly applied

Georgia Statute, one exercising the right to free speech

must determine at the peril of harsh criminal prosecution

and costly appeal the reach of that right. Who now, in

Georgia, or any other state which has a similar law, would

dare to engage in any public protest of segregation of

religious institutions? To permit such an indefinite statute

to stand is to nullify, in Georgia, freedom of speech which

strikes at so pernicious a social evil.

II.

Petitioner’s Conviction Was Affirmed Also on the

Ground That Personal Bias and Prejudice of the Trial

Judge Against Him Was Not a Basis for Disqualification

of the Judge in Violation of His Right to Due Process

of Law Under the Fourteenth Amendment.

A. The Suprem e Court o f Georgia Applied an Im proper

Standard in H olding Bias and Prejudice W as Not a

Ground for D isqualification o f the Trial Judge.

Before pleading to the merits, petitioner moved to dis

qualify Judge Durwood T. Pye of the Superior Court of

Fulton County, Georgia, on the ground that, by reason of

“repeated denunciation of the Negro race in general and

the defendant in particular” and “an extraordinary and

prejudicial interest against the defendant,” the judge could

not give petitioner a fair and impartial trial.6

6 The motion to disqualify or recuse reads as follows:

1. Defendant shows that because of a repeated denuncia

tion of the Negro race in general and the defendant in particu-

15

The motion to disqualify was submitted at the opening

of petitioner’s trial (R. 43-45). After counsel presented

lar by the Honorable Durwood T. Pye, Judge in this ease, he,

the said Judge Pye, cannot impartially try said case on its

merits.

2. That the said Judge Pye has manifested an extraordinary

and prejudicial interest against the defendant generally and

specifically in the manner that he has brought this and other

defendants to trial before him, in th a t:

a. That the said Judge Pye took it upon himself, contrary

to the normal and accepted practice, to solicit from the Chief

of Police and/or others the names of this and other defen

dants who had been charged with misdemeanor offenses re

lating to peaceful protest against discriminatory practices,

policies, customs and acts by private persons, public officials

and others as relates to the rights, privileges and immunities

of Negro citizens in the City of Atlanta, Pulton County,

Georgia.

b. ̂That this defendant was duly bound over from the

Municipal Court of Atlanta to the Criminal Court of Pulton

County as is customarily done for alleged misdemeanants;

that defendant’s ease was being processed according to stand

ard practice in said court; that according to standard prac

tice in said court, defendant would have been scheduled for

trial as the dockets and calendars of said court would permit.

c. That there are at least one hundred prisoners in the

Pulton County Jail presently awaiting trial.

d. That ordinarily the Grand Jury is empaneled and

charged by the presiding judge of the term.

e. That contrary to practice and custom the said Judge

Pye caused the misdemeanor charges against the defendant

to be presented by the Solicitor General of Pulton County to

the said grand jury which was empaneled at his instance.

f. That in charging said grand jury the said Judge did

further manifest that his basic dislike and prejudice to

Negroes by alluding to some of them as “savages.” Further,

m his charge to said grand jury he made extended remarks

concerning the crime rate among Negroes without making

any constructive suggestions, or asking for any from the

grand jurymen; he only suggested punishment “far more

severe than at present.”

g. Said Judge Pye further expounded at great length in

his charge about “property rights,” and further sought to

construe the Act approved February 18, 1960, and set forth

in Georgia Laws I960, page 142, drawing his own conclu-

16

the motion, Judge Pye proceeded immediately,* 7 without

taking testimony, to read it into the record by paragraphs,

state his reasons for denying the truth of the allegations8

(R. 45-84), and deny the motion (R. 76).9 After overruling

the motion, the court cited petitioner’s counsel for con

tempt, charging presentation of the motion was “an insult

done to the court” (R. 84) and ordered them to show cause

why they “should not be dealt with from the standpoint of

contempt and otherwise as lawyers” (R. 84, 85). Counsel

would have to “convince the court that they believe the

sion, when said Act has not yet been construed by the highest

court of this state.

h. Said Judge Pye further charged that said Act has been

“flouted, defied and violated, that these violations have been

frequent and repeated, and the results of combinations and

conspiracies.” That said language to the grand jury was

prejudicial in the manifestation of the prejudice of the said

trial judge when made to a grand jury prior to the present

ment of the facts relating to defendant’s case and those of

others similarly charged.

3. Defendant shows that the acts of said trial judge as

alleged in paragraph 2 above, are in derogation of the due

process and equal protection clauses of Article I, Section I,

Paragraph 3 of the Georgia Constitution and Section I of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

W herefore, defendant prays that the Honorable Durwood

T. Pye disqualify himself in this case and refer it back to

the presiding judge of this Court.

7 Shortly after the court addressed itself to the allegations of the

motion to disqualify, petitioner’s counsel sought to have the jury

leave the room but Judge Pye refused on the ground that he had

already begun to consider the motion to disqualify (R. 48).

8 The judge conceded, however, after checking court records at

the request of petitioner’s counsel, that when ruling on a motion to

disqualify brought some years earlier by other counsel in another

case that he had stated that he had “strong personal views against

mongrelization of the races” (R. 81, 77-80).

9 Judge Pye placed into the record a letter to the Chief of Police

and the reply of the Chief, as well as the charge to the grand jury

which indicted petitioner, reference to which was made in the mo

tion to disqualify.

17

court has any prejudice against them, against any Negro,

that they honestly believe that the court cannot afford a

fair trial for any man. . . . ” (R. 85). At this point, counsel

asked for a continuance until after the hearing on the

contempt citation, because under threat of contempt they

could not “appropriately and properly” represent their

clients (R. 85-86), but the motion was overruled (R. 86).

On appeal, despite petitioner’s express reliance on Ms

Fourteenth Amendment right to an impartial tribunal,

the Supreme Court of Georgia held that Ga. Code Ann.

§24-10210 provides the only circumstances under which a

Judge of the Superior Court may be disqualified. Peti

tioner’s motion to disqualify was held properly overruled

because: “prejudice or bias of the judge which is not based

on an interest either pecuniary or relationship to a party

affords no legal ground of disqualification,” infra, pp, la-

2a.

10 §24-102. When judicial officer disqualified.—No judge or jus

tice of any court, no ordinary, justice of the peace, nor pre

siding officer of any inferior judicature or commission shall sit in

any cause or proceeding in which he is pecuniarily interested, nor

preside, act, or serve, in any case or matter, when such judge is

related by consanguinity or affinity to any party interested in the

result of the case or matter, within the sixth degree, as computed

according to the civil law, and relationship more remote shall not

be a disqualification; nor in which he has been of counsel, nor in

which he has presided in any inferior judicature, when his ruling or

decision is the subject of review, without the consent of all parties

in interest: Provided, that in all cases in which the presiding judge

of the superior court may have been employed as counsel before his

appointment as judge, he shall preside in such cases if the opposite

party or counsel agree in writing that he may preside, unless the

judge declines so to do: and Provided further that no judge or

justice of any court, no ordinary, justice of the peace, nor presiding

officer of any inferior judicature or commission shall be disqualified

from sitting in any cause or proceeding because of the fact that he

is a policyholder or is related to a policyholder of any mutual

insurance company which has no capital stock. But nothing in the

last proviso shall be construed as applying to the qualifications of

trial jurors.

18

This holding that personal or racial bias against an ac

cused is in no circumstances sufficient to disqualify a trial

judge is a clear violation of the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. “No matter what the evidence

was against him” petitioner “had the right to have an im

partial judge.” Tumey v. Ohio, 273 U. S. 510, 535.

The occasions which give rise to bias in a trial judge

cannot be arbitrarily limited to “interest either pecuniary

or relationship to a party” as provided by Ga. Code Ann.

§24-102, infra, pp. la-2a. In Tumey, supra, the Fourteenth

Amendment required disqualification of a mayor who also

served as trial judge “because of direct pecuniary interest

in the outcome and because of his official motive to convict

and to graduate the fine to help the financial needs of the

village.” (Emphasis supplied.) But in Be Murchison,

349 U. S. 133, the court found an “interest in the outcome”

sufficient to disqualify when the same official served as

“one-man grand jury,” out of which contempt charges

arose, and as the trial judge of those charges. The Court

found that the Fourteenth Amendment requires disqualifi

cation whenever a judge’s “interest in the outcome” would

work “actual bias in the trial of cases.” Re Murchison, 349

U. S. at 136. The “interest” which disqualifies “cannot be

defined with precision,” ibid. “ [Circumstances and rela

tionships must be considered,” ibid.11

Petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment right to an impartial

trial, therefore, cannot be restricted arbitrarily to the “in

terests” set forth in Ga. Code Ann. §24-102. Tumey v.

Ohio, supra, and Re Murchison, supra, demonstrate with

respect to a trial judge (Irvin v. Doivd, 366 U. S. 717, and

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 723, with respect to the trial

11 “Every procedure which would offer a possible temptation to

the average man as a judge not to hold the balance nice, clear and

true between the state and the accused, denies the latter due process

of law.” Tumey v. Ohio, 273 U. S. 510, 532.

19

jury) that “impartiality is not a technical conception. It

is a state of mind. For the ascertainment of this mental

attitude of appropriate indifference, the Constitution lays

down no particular tests and procedure is not chained to

any ancient and artificial formula,” United States v. Wood,

299 U. S. 123,145.

Petitioner sought to disqualify the trial judge because

of a racial and personal bias sufficient to deny him a fair

and impartial trial. The courts of Georgia refused to con

sider these allegations, because Ga. Code Ann. §24-102

“does not provide that bias or prejudice is a ground to

disqualify” a trial judge, infra, pp. la-2a. Applying a

standard of disqualification impermissible under the Four

teenth Amendment, the Supreme Court of Georgia has af

firmed petitioner’s conviction, in violation of his right to

due process of law. Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U. S. 534.

B. Petitioner W as Entitled to a H earing on tlie M otion

to D isqualify or a Trial o f the Charges Against Him

B efore Another Judge.

Had petitioner alleged bias and prejudice sufficient to

deny him an impartial trial in a federal court, another

judge would have been designated immediately to try his

case. 28 IT. S. C. §144; Berger v. United States, 255 U. S.

22, 36:12

To commit to the judge a decision upon the truth of the

facts gives chance for the evil against which the section

12 Berger v. United States, 255 U. S. 22, illustrates the gap be

tween the Georgia rule applied to foreclose any consideration of

petitioner’s claim of bias and standards of fairness which prevail in

federal courts. In Berger, the Court held that under Section 21 of

the Judicial Code of 1911 (substantially carried forth in 28 U. S. C.

§144) the mere filing of an affidavit in the manner provided show

ing “objectionable inclination or disposition of the Judge,” 255

U. S. at 35, sufficiently “withdraws from the presiding judge a deci

sion upon the truth of the matters alleged,” 255 U. S. at 36, and

acts to transfer the litigation to another judge.

20

is directed. The remedy by appeal is inadequate. It

comes after the trial and if prejudice exists, it has

worked its evil and the judgment of it in a reviewing

tribunal is precarious. It goes there by presumptions

and nothing can be more elusive of estimate or decision

than a disposition of a mind in which there is a per

sonal ingredient.

Federal law withdraws from the presiding judge a deci

sion upon the truth of the matters alleged in a motion to

disqualify. No less a standard should apply under the

Fourteenth Amendment. No judge should be permitted

to try his own case, cf. Re Murchison, 349 U. S. 133. “The

risk to impartial justice is too great,” 8ocher v. U. 8., 343

IT. S. 1, 17 (Mr. Justice Black dissenting).13

Long ago, this Court recognized that where “the issue

between the judge and the parties had come to involve

marked personal feeling that would not make for an im

partial and calm judicial consideration,” the presiding

judge should properly withdraw. Cooke v. United States,

267 U. S. 517, 539. See also Mr. Justice Frankfurter dis

senting in Sacher v. United States, 343 IT. S. at 30-33. In

this case the record demonstrates the intensity of feeling

generated by the motion to disqualify (R. 84-85, 87-88).

Judge Pye took personal affront at the motion and immedi

ately after overruling it cited counsel for contempt because

they had asked him to recuse himself. Under the Fourteenth

Amendment, the right to a fair and impartial judge is of

such consequence that trial of the charges against an ac

cused alleging bias or, at least, determination of the mo

tion to disqualify should be withdrawn from the presiding

judge.

13 This case does not involve, as did Sacher, the well-established

power of courts to punish disruptive conduct occurring in open

court.

21

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, petitioner prays

tha t the petition for w rit of certiorari be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Michael Meltsner

Of Counsel

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabr.it, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Donald L. H ollowell

H oward Moore, J r.

859x/2 Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioner

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX

Opinion

(Decided: April 9, 1964)

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Ashton Bryan J ones,

—'v.—

State.

Almand, Justice. Ashton B. Jones upon his conviction

of violating Code Ann. §26-6901 (interfering with religious

worship) was sentenced by the court. His motion for a new

trial was overruled. Error is assigned on the order denying

him a new trial. Error is also assigned on (a) the refusal

of the trial judge to disqualify himself from presiding in

the case; (b) the order dismissing on motion of the State

the defendant’s plea in abatement; (c) the orders overruling

the general and special demurrers to the indictment; and

(d) the order overruling the defendant’s motion in arrest

of judgment.

1. Motion to disqualify. The defendant before pleading

to the merits moved to disqualify the trial judge on the

ground that he, by reason of bias and prejudice, could not

give him a fair and impartial trial. Code Ann. §24-102 pro

vides the circumstances under which a judge of the superior

court may be disqualified. This Code section does not pro

vide that bias or prejudice is a ground to disqualify him

from presiding in the case. The statutory grounds of dis

2a

qualification contained in this section are exhaustive. Blake-

man v. Harwell, 198 Ga. 165 (31 SE 2d 50). “Alleged prej

udice or bias of a judge, which is not based on an interest

either pecuniary or relationship to a party within a pro

hibited degree, affords no legal ground of disqualification.”

Elder v. Camp, 193 Ga. 320 (18 SE 2d 622). See also Moore

v. Dugas, 166 Ga. 493 (143 SE 591).

2. The plea in abatement. The plea alleged that the in

dictment under Code §26-6901 was being applied so as to

deny the defendant due process of law and equal protection

of the law under the Constitution of Georgia (Code Ann.

§2-103) and the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Con

stitution in that “the said statute is being applied so as to

perpetuate a scheme of racial discrimination in places of

public worship within the City of Atlanta, Fulton County,

Georgia, which has long existed under State sanction

through legislative enactments, recognized customs and

usages, and which has been aided and abetted by the dis

criminatory enforcement and application of the said

statute.” The State moved to dismiss the plea on the

grounds that all the allegations contained in the plea go

to the merits of the case and are not the proper subject

matter for a plea in abatement. This motion to dismiss was

sustained.

Pleas in abatement are dilatory pleas. They must be

strictly construed, certain in intent and leave nothing to

be suggested by intendment. Every inference must be

against the pleader. Meriwether v. State, 63 Ga. App. 667-

(1) (11 SE 2d 816). The indictment charges the defendant

with disturbing divine worship by the doing of certain acts.

There is no allegation of the absence of such acts before

the grand jury or that the indictment was returned solely

by the grand jury “to perpetuate a scheme of racial dis

Opinion

3a

crimination in places of public worship.” “It has never been

the practice in this State to go into an investigation to test

the sufficiency of the evidence before the grand jury.”

Powers v. State, 172 Ga. l-(3) (157 SE 195).

It was not error to dismiss the plea.

3. The demurrers to the indictment. The general de

murrers. Code §26-6901 provides: “Any person who shall,

by cursing or using profane or obscene language, or by

being intoxicated, or otherwise indecently acting, interrupt,

or in any manner disturb, a congregation of persons law

fully assembled for divine service, and until they are dis

persed from such place of worship, shall be guilty of a mis

demeanor.” The indictment charged the defendant with the

offense of a “misdemeanor (Sec. 26-6901) for that said ac

cused, in the County of Fulton and State of Georgia, on the

30th day of June, 1963 with force and arms, said accused

being at and on the grounds of the First Baptist Church of

Atlanta, did interrupt and disturb a congregation of per

sons then and there lawfully assembled for divine service

at said church, by loud talking, shouting, and by sitting on

the floor of said church and by otherwise indecently acting

contrary to the laws of said State, the good order, peace

and dignity thereof.”

(a) The defendant challenges the statute under which

he was indicted (Code Ann. §26-6901) on the ground that

the statute is so vague, indefinite and ambiguous that it

wholly fails to give the defendant notice of the act and

conduct which constitutes a violation of said statute as is

required by the due process clauses of the State Constitu

tion and the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Con

stitution.

Opinion

4a

Statutory language in defining a criminal offense which

conveys a definite meaning as to proscribed conduct when

measured by common understanding and practice satisfies

due process requirements. United States v. Petrillo, 332

U. S. 1. The statute under consideration proscribes the

interruption or disturbance of a congregation of persons

assembled for divine service in one of five different ways.

The defendant under this indictment is put upon notice

that he at a certain day at a named church did by “loud talk

ing, shouting and by sitting on the floor of said church and

by otherwise indecently acting” interrupt and disturb a con

gregation of persons assembled for divine worship at said

church. This court in Folds v. State, 123 Ga. 167 (51 SE

305) held that the words “indecently acting” must be taken

in the comprehensive sense and include all improper con

duct which interrupts or disturbs a congregation of persons

lawfully assembled for divine worship. Any person of com

mon intelligence (and particularly one who claims to be an

ordained minister) may determine whether the particular

acts and conduct charged him with improper conduct, i.e.,

indecent acting. See Watson v. State, 192 Ga. 679 (16 SE

2d 426); Farrar v. State, 187 Ga. 401-(2) (200 SE 803), and

Clark v. State, 219 Ga. 680 (135 SE 2d 270).

It was not error to overrule this ground of the general

demurrer.

(b) The indictment was demurred to on the grounds (1)

that it did not charge any offense under the law; (2) that

the allegations in the indictment were insufficient to charge

the defendant with any offense under any law of the State

and, (3) that the allegations in the indictment are so vague,

indefinite and ambiguous that they wholly fail to give the

defendant reasonable and adequate notice, as required by

the due process clauses of the State Constitution and the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

Opinion

Opinion

Laying the indictment by the side of the statute (Code

§26-6901) discloses that the defendant is charged with the

offense prohibited by the statute and that he is apprised

with reasonable certainty of the nature of the charge, Glover

v. State, 126 Ga. 594 (55 SE 592), and that the statute is

sufficient to withstand a general demurrer, Ruff v. State,

17 Ga. App. 337 (86 SE 784).

The charge that the allegations in the indictment are so

vague, indefinite and ambiguous as not to meet the require

ments of due process is controlled by the ruling in division

3(a) above.

4. Special demurrers. Ground 1 asserts that the indict

ment fails to allege that any person or persons were dis

turbed or give the name of any person who was disturbed.

Grounds 2 and 3 allege that the words “by loud talking,

shouting and by sitting on the floor of said church and by

otherwise indecently acting” are too vague and indefinite,

and insufficient to enable the defendant to prepare his de

fense and that there was no allegation that the “loud talk

ing” was either profane, abusive, unreasonable or willful.

Ground 4 alleges that the words in the indictment “by other

wise indecently acting” are vague and insufficient to put

defendant on notice of the nature and character of his acts.

Ground 5 asserted that the indictment fails to state the State

and county of defendant’s residence.

The court overruled all of the special demurrers escept

ground 4 which it sustained, and the words “and by other

wise indecently acting” were stricken from the indictment.

Error is assigned on the overruling of the other demurrers.

This court in considering the sufficiency of an indictment

under Code §26-6901 in Minter v. State, 104 Ga. 743, 748

(30 SE 989) said: “The terms of the statute upon which

this presentment is founded so distinctly individuate the

6a

offense which it defines, that the nse of such terms in charg

ing the offense in the presentment sufficiently notified the

accused of what he was called upon to answer. The gist of

the offense is the disturbance of a congregation lawfully

assembled for divine service; and the manner and means,

or the particular acts, by which the disturbance of such con

gregation may be effected are set out in the statute; and a

general allegation that the disturbance was caused by such

acts is all that is necessary, without entering into details.”

See also Folds v. State, 123 Ga. 167; Brown v. State, 14 Ga.

App. 21-(4) (80 SE 26).

It was not error to overrule the four special demurrers.

5. Motion in arrest of judgment. The first ground of the

motion asserted that there was no valid and sufficient in

dictment. Our ruling in Division 3 of this opinion fore

closes any further discussion of this ground. The second

ground alleged that Code 26-6901 was violative of the due

process clauses of the State Constitution and the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution. Our ruling

in Division 3(a) of this opinion settles this ground.

The third ground asserts that when the court struck the

words “and by otherwise indecently acting” from the indict

ment, it materially amended the indictment in derogation

of the due process clauses of the State Constitution and

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution,

and the indictment as amended failed to charge an offense

under the laws of Georgia.

As pointed out in our rulings on the special demurrers

the court sustained the special ground of the defendant’s

demurrer and on his motion struck the words “by otherwise

indecently acting” from the indictment. The court struck

these words from the indictment as “constituting surplus

age, in order that the jury might not be confused.” This the

Opinion

7a

court had the right to do and such action did not render

the whole indictment void. Brooks v. State, 178 Ga. 784-(3)

(175 SE 6); Patton v. State, 59 Ga. App. 871(2) (2 SE 2d

511). This is especially true where the court’s action was

at the defendant’s request. Ralston v. Cox, 123 F2d 196,

cert, denied 315 U. S. 796 (62 SC 488, 86 LE 1197).

The indictment with the words “and by otherwise in

decently acting” stricken was sufficient to charge an offense

under Code §26-6901. Folds v. State, 123 Ga. 167, supra.

The motion in arrest was properly overruled.

6. Motion for a new trial. The motion consists of the

general grounds and 14 amended grounds.

(a) Exceptions to instructions to the jury. The court

after reading Code §26-6901 to the jury charged that if

they found beyond a reasonable doubt that loud talking or

sitting on the floor or shouting be shown, provided it was

such that disturbed persons assembled for divine service,

such would constitute indecent acting within the meaning

of the law.

This charge is not subject to the exception that it con

veyed an erroneous impression or inference. The charge

was in harmony with the statute and with this court’s defini

tion of “indecent acting” in Folds v. State, 123 Ga. 167,

supra.

(b) The court charged the jury that though the indict

ment charged that the offense was committed with force

and arms, it would be sufficient if the State should prove

the remaining allegations of the indictment. The ground

of the exception is that it erroneously conveyed to the jury

the idea that the defendant had used force and violence. It

was not error for the court to inform the jury that it was

Opinion

8a

not necessary to prove tliis formal phrase of the indictment.

See Pitts v. State, 219 Ga. 222 (132 SE 2d 649).

(c) The court instructed the jury that if the state proved

that the accused did interrupt or disturb—either one was

sufficient to support the allegation in the indictment that

he did interrupt and disturb.

This charge is not subject to the objection that it was

erroneous and harmful.

(d) The court instructed the jury that if the defendant

did the acts alleged in the indictment for the purpose of

causing the church to change its rules and practice to con

form to those of the defendant’s liking, this would not con

stitute any defense.

This instruction, it is alleged, was in derogation of the

defendant’s right of free speech and association guaranteed

by the State and Federal Constitutions.

The statute under which the defendant was being pros

ecuted does not make it an offense for one to speak in a

church service. The gist of the offense is the interruption

or disturbance of the congregation while engaged in divine

service. The statute may be violated not only by the spoken

word (cursing, profane or obscene language) but by in

decent acting. One might remain mute, yet by improper

conduct interrupt or disturb the service.

The constitutional right of one to freedom of speech is

counterbalanced by the right of the many to their constitu

tional freedom in the practice of their religion. Neither

occupies a preferred position in the Constitution.

The instruction was not error.

(e) Grounds 5, 6 and 7 will be considered together. (5)

The court charged the jury that a church has the right to

establish its own practice and rules for the admission and

Opinion

9a

seating of persons and if one refused to comply with the

rules the church authorities had the right to use reasonable

force to evict him. (6) The court charged the jury that if

the defendant disagreed with the rules and practices of the

church and engaged in loud talking, shouting and sitting on

the floor to induce the church to change its rules, his desire

to cause the church to change its rules would not constitute

any defense. (7) The court charged that the jury was not

concerned with the question of segregation or integration

or with the correctness or propriety of any rule or practice

of the church. These charges were objected to as being (5)

injurious and prejudicial; (6) erroneous and incorrect and

(7) harmful because the jury should have been allowed to

consider the question as to whether the church was prac

ticing racial segregation.

From the testimony of the defendant it clearly appears

that he went to the church for the purpose of getting the

church authorities to change its rules and practices as to

seating persons. The evidence authorized these instruc

tions.

(f) The defendant alleges error because the court read

to the jury the indictment without reading the three words,

“otherwise indecently acting,” which had been stricken by

the court on motion of the defendant.

There is no merit to this contention. It was proper for

the court to read the indictment as it stood after the elimina

tion of these words.

7. Glenn Bailey testified that he was a member of the

First Baptist Church and was in the church sanctuary for

the morning service of June 30, 1963 and heard a man

hollering and that the voice was coming from the front of

the church. Defendant moved to rule out this testimony be

Opinion

10a

cause the witness did not identify the defendant as the one

who hollered. The motion was overruled. There was other

testimony that the hollering was done by the defendant.

It was not error to overrule the motion.

8. On cross-examination of the witness the court sus

tained the objection of the State’s counsel to the question

“Do you know that as a matter of fact the disorderly con

duct charge against the defendant was dismissed!” The

defendant alleges error on the ground that “the movant

was unable to solicit from the witness relevant facts within

his own knowledge which would have exculpated the

movant” and thereby limited the scope of defendant’s cross-

examination.

What action took place in another court upon a different

charge was irrelevant and immaterial. The action of the

court in confining counsel to the issues of the case on trial

does not abridge counsel’s right to a thorough cross-exami

nation. Pulliam v. State, 196 Ga. 782 (28 SE 2d 139).

9. Ground 11 alleges error in the court, over objection,

permitting the State’s counsel on cross-examination of the

defendant to question the defendant on his acts and con

duct at other places in Atlanta.

It appears from the testimony of the defendant that he

first brought into the case incidents of picketing, “sitting

in” and “lying in” at other places in Atlanta. It was not

error to permit State’s counsel to cross-examine the de

fendant as to these other incidents.

10. Grounds 12 and 13 assign error on the court’s over

ruling defendant’s motion for a directed verdict of acquit

tal. It is never error to refuse to direct a verdict of ac

quittal. Baugh v. State, 211 Ga. 863 (89 SE 2d 504).

Opinion

11a

11. The final special grounds complain that the court’s

sentence of 12 months upon the public works, 6 months in

jail and a $1,000 fine was arbitrary, capricious, unreason

able and violative of the constitutional provisions for due

process of law, and fair and impartial trial, and was ex

cessive. .. .

The sentence imposed was within the limits provided by

law. Being not greater than the maximum sentence pro

vided by law it is not excessive. Godwin v. State, 123 Ga.

569 (51 SE 598).

12. The verdict is fully supported by the evidence and

the general grounds were properly overruled.

Judgment affirmed. All the Justices concur.

Opinion

12a

Judgment

(Decided April 9,1964)

I n t h e

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA

Ashton Bryan J ones,

T he State.

The Honorable Supreme Court met pursuant to adjourn

ment. The following judgment was rendered:

Ashton Bryan Jones v. The State.

This case came before this court upon a writ of error

from the Superior Court of Fulton County; and, after

argument had, it is considered and adjudged that the judg

ment of the court below.be affirmed.

All the Justices concur.

13a

Denial of Rehearing

(Decided April 21,1964)

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Ashton Bryan J ones,

T he State.

The Honorable Supreme Court met pursuant to adjourn

ment. The following order was passed:

Ashton Bryan Jones v. The State.

Upon consideration of the motion for a rehearing filed

in this case, it is ordered that it hereby be denied.

:

38