Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Petitioners, 1988. 0100def3-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/255a670d-7d6e-4d3d-a561-4b55d81c338b/missouri-v-jenkins-brief-of-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

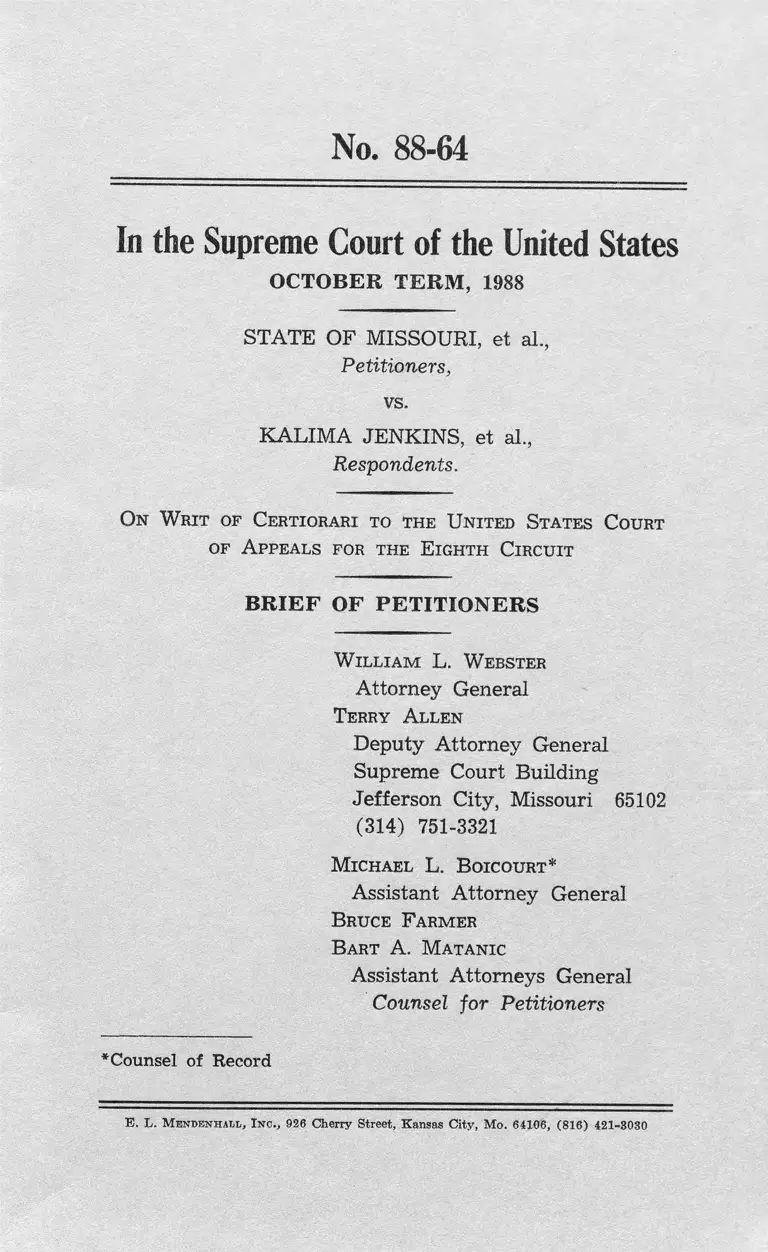

No. 88-64

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1988

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

KALIMA JENKINS, et al.,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States Court

of A ppeals for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF OF PETITIONERS

W illiam L. W ebster

Attorney General

Terry A llen

Deputy Attorney General

Supreme Court Building

Jefferson City, Missouri 65102

(314) 751-3321

M ichael L. Boicourt*

Assistant Attorney General

Bruce Farmer

Bart A. M atanic

Assistant Attorneys General

Counsel for Petitioners

* Counsel of Record

E. L. M endenhall, Inc., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, M o. 64106, (816) 421-3030

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the Eleventh Amendment prohibits an

award of attorney’s fees against a State based on current

hourly rates which include interest and a delay in pay

ment factor.

2. Whether paralegal and law clerk expenses awarded

under 42 U.S.C. § 1988 must be assessed at actual cost

rather than market rates.

II

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING IN THE

COURT OF APPEALS

The parties to the proceeding in the Court of Appeals

were as follows:

Appellants/cross-appellees

(now petitioners):

The State of Missouri

The Honorable John Ashcroft, Governor of the State of

Missouri

The Honorable Wendell Bailey, Treasurer of the State

of Missouri

Dr. Robert E. Bartman, The Commissioner of Education

of the State of Missouri

The Missouri State Board of Education: Roseann Bentley,

Dan L. Blackwell, Terry A. Bond, Thomas R. Davis,

Susan D. Finke, Raymond F. McAllister, Jr., Cynthia

B. Thompson and Roger L. Tolliver

Appellees/'cross-appellants

(now respondents):

Kalima Jenkins, by her next friend, Kamau Agyei

Carolyn Dawson, by her next friend, Richard Dawson

Tufanza A. Byrd, by her next friend, Teresa Byrd

Derek A. Dydell, by his next friend, Maurice Dydell

Terrance Cason, by his next friend, Antonia Cason

Jonathan Wiggins, by his next friend, Rosemary Jacobs

Love

Kirk Allan Ward, by his next friend, Mary Ward

Robert M. Hall, by his next friend, Denise Hall

I l l

Dwayne A. Turrentine, by his next friend, Shelia Tur-

rentine

Gregory A. Pugh, by his next friend, Barbara Pugh

Cynthia Winters, by her next friend, David Winters, on

behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated

Additional

Appellants/cross-appellees below:

The School District of Kansas City, Missouri, and Claude

Perkins, then-superintendent

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..... ........... ......................... t

PARTIES BELOW ........ n

TABLE OF CONTENTS .............. ..... .......... ................ Iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................. v

OPINIONS BELOW ............. ]

JURISDICTION_________ ,

STATUTE INVOLVED .............. 2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION ..................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................................... 2

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT............... 7

ARGUMENT........ ..... ....................................................... 9

I. The Eleventh Amendment prohibits an award

of prejudgment interest or compensation for

delay against a State as part of reasonable

attorney’s fees under 42 U.S.C. § 1988 ______ 9

A. The conflicting decisions of the Courts

of Appeals ................................................... 9

B. Legislative waiver of the Eleventh

Amendment must be unequivocal and ex

pressed in unmistakable language ........... 11

C. 42 U.S.C. § 1988 does not waive the

States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity

from prejudgment interest ........ .......... . 16

II. Reimbursing the actual cost of paralegal and

law clerk services is appropriate under the

facts of this case ............................ 24

CONCLUSION ............ . ................. . .... ..... 28

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness So

ciety, 421 U.S. 240 (1975) .................................. 24,

Atascadero State Hospital v. Scanlon, 473 U.S.

234 (1985) ............................. -......... 11-12, 13, 14, 15,

Badaracco v. C.I.R., 464 U.S. 386 (1984) ...............

Blanchard v. Bergeron, No. 87-1485 (cert, granted

June 27, 1988) ............................ ............ .................

Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886 (1984) ......................

City of Riverside v. Rivera, 477 U.S. 561 (1986)

Daly v. Hill, 790 F.2d 1071 (4th Cir. 1986) ____ ___

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. ft 9444

(C.D. Cal. 1974) ...................................................... 20,

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) .......14, 18,

Employees v. Missouri Public Health Department,

411 U.S. 279 (1973) ..............................................14,

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976) ...............

Florida Department of State v. Treasure Salvors,

Inc., 458 U.S. 670 (1982) .......... ......... .............. .

Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education,

775 F.2d 1565 (11th Cir. 1985) ..............................

Greater Los Angeles Council on Deafness v. Com

munity Television of Southern California, 813

F.2d 217 (9th Cir. 1987) ..........................................

Greenspan v. Automobile Club of Michigan, 536

F.Supp. 411 (E.D. Mich. 1982) ..............................

Grendel’s Den, Inc. v. Larkin, 749 F.2d 945 (1st

Cir. 1984) ........................... ......................................

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983) ...............

25

18

26

24

26

25

10

26

23

22

12

23

10

21

24

10

27

VI

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978) .............. passim

Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 838 F.2d 260 (8th

Cir. 1988) .....................................................1,2,9,10,20

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974) ......... .....................................20, 26

Jordan v. Multnomah County, 815 F.2d 1258 (9th

Cir. 1987) ..................................... io

Lamphere v. Brown University, 610 F.2d 46 (1st

Cir. 1979) .................................... ....... ..... ..... ........... 24

Library of Congress v. Shaw, 478 U.S. 310

(1986) ......... ........ ............. ....... ......... ........ ......... passim

Lightfoot v. Walker, 826 F.2d 516 (7th Cir. 1987) 10

Murray v. Wilson Distilling Co., 213 U.S. 151

(1909) ............................ ........ ..... ............ ................. 14

Parden v. Terminal Railway of Ala. Docks Dept.,

377 U.S. 184 (1964) ................................................ 14

Pennhurst State School and Hospital v. Halder-

man, 451 U.S. 1 (1981) .......... .......... ...... .... 15,18,22

Pennhurst State School and Hospital v. Halder-

man, 465 U.S. 89 (1984) ...................... 12,13,15,18

Poleto v. Consolidated Rail Corporation, 826 F.2d

1270 (3rd Cir. 1987) .............................................. 21

Quern v. Jordan, 440 U.S. 332 (1979) ................... 14,18

Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546 (10th Cir. 1983) ....10,24

Roe v. City of Chicago, 586 F.Supp. 513 (N.D.

111. 1984) ........................................ 24

Rogers v. Okin, 821 F.2d 22 (1st Cir. 1987) ....9,11, 18,

21,22

Ross v. Saltmarsh, 521 F.Supp. 753 (S.D. N.Y.

1981), affd, 688 F.2d 816 (2nd Cir. 1982) .. ..... 24

Sisco v. J.S. Alberici Construction Co., 733 F.2d

55 (8th Cir. 1984) 10

VII

62 Cases of Jam v. United States, 340 U.S. 593

(1951) .......................................................................... 25

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D.

Cal. 1974) ..................... 20

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Edu

cation, 66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D. N.C. 1975) ........... 20

Thompson v. Kennickell, 836 F.2d 616 (D.C. Cir.

1988) ................. 21

TV A v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978) ....................... . 26

United States v. Deluxe Cleaners and Laundry,

Inc., 511 F.2d 926 (4th Cir. 1975) ................... 26

United States v. N.Y. Rayon Importing Co., 329

U.S. 654 (1947) .................... ......................... ....... 24

Utah International, Inc. v. Department of Inte

rior, 643 F.Supp. 810 (D. Utah 1986) ............... 21

Welch v. Texas Department of Highways and

Public Transportation, ....... U.S.........., 107 S.Ct.

2941 (1987) ........................................................ 13,14,18

Constitutional Provisions:

Eleventh Amendment ..... passim

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1920 .......................................................... 19

28 U.S.C. § 2411 .......................................... ........ ...... 18

28 U.S.C. § 2412(d )(2 )(A ) .................................... 17

28 U.S.C. § 2516 .................. 18

28 U.S.C. § 2674 .......... 18

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ....... 14

42 U.S.C. § 1988 .... .......................... passim

Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 706 (k), as amended,

42 U.S.C. § 2000(e-5)k (Title VII) ................... 16

V III

Legislative Materials:

S.Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted

in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad.News 5908 _17, 18,

20, 26

Other:

C. McCormick, Damages § 50, p. 205 (1935) ..... 19

10 C. Wright, A. Miller & M. Kane, Federal Prac

tice and Procedure §§ 2666, 2670 (2d ed. 1983) 19

OPINIONS BELOW

The Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit is reported at 838 F.2d 260 (8th

Cir. 1988) and is reprinted in Petitioners’ Petition for

Writ of Certiorari in the Appendix at page A -l.

The May 11, 1987 opinion of the United States Dis

trict Court for the Western District of Missouri is un

reported but is reprinted in Petitioners’ Petition for Writ

of Certiorari in the Appendix at page A-22. The July 14,

1987 opinion of the United States District Court for the

Western District of Missouri is unreported but is re

printed in Petitioners’ Petition for Writ of Certiorari in

the Appendix at page A-44.

JURISDICTION

On January 29, 1988, the United States Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit issued its order affirming

the District Court’s judgment awarding attorney’s fees

and expenses. On April 13, 1988, the United States Court

of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit issued its order denying

Petitioners’ Motion for Rehearing En Banc.

A Petition for Writ of Certiorari was filed by Peti

tioners herein on July 5, 1988. Pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 2101(c), the Petition was timely filed. Certiorari was

granted on October 11, 1988. The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

2

STATUTE INVOLVED

In relevant part, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 provides:

In any action or proceeding to enforce a provision

of sections 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985, and 1986 of this

title, title IX of Public Law 92-318, or title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the court, in its dis

cretion, may allow the prevailing party, other than

the United States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part

of the costs.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION

The relevant constitutional provision involved in this

case is the Eleventh Amendment which provides:

The Judicial power of the United States shall not

be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity,

commenced or prosecuted against one of the United

States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens

or Subjects of any Foreign State.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case is the fee tail of the desegregation litigation

involving Kansas City, Missouri.1 This Court has granted

1. The Kansas City, Missouri desegregation litigation has

resulted in numerous published opinions. Jenkins v. State of

Missouri, 838 F.2d 260 (8th Cir. 1988), is the only published fee

decision. For information concerning the history of the under

lying litigation, the Court is referred to the following decisions:

In re Jackson County, Missouri, 834 F,2d 150 (8th Cir. 1987);

Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir, 1986) (en

banc), cert, denied, 108 S.Ct. 70 (1987); School District of Kan-

(Continued on following page)

3

certiorari on two issues concerning the fee awards. One,

whether the States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity pre

cludes a fee award based on current hourly rates which

include prejudgment interest or a delay in payment fac

tor. Two, whether 42 U.S.C. § 1988 allows reimburse

ment for paralegal and law clerk services at market rates

rather than actual cost.

The plaintiff/schoolchildren were represented through

out most of this litigation by two groups of attorneys—

Arthur A. Benson II and his staff and the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund, Inc. (LDF). While this case was orig

inally filed on May 26, 1977 (J.A. 2), the attorneys

awarded fees did not enter the case until later. Benson

entered his appearance on behalf of the plaintiffs on

March 15, 1979 (J.A. 2). The LDF entered an appear

ance in the case on May 27, 1982 (J.A. 2).

The liability litigation took a number of years. The

liability trial began on October 31, 1983 (J.A. 3). After

ninety-two trial days, the liability trial ended on June 13,

1984 (J.A. 3-9). On September 17, 1984, the plaintiff/

schoolchildren became prevailing parties when the dis

trict court issued its judgment finding the State defen

dants (Petitioners herein) and the Kansas City, Missouri

School District (KCMSD) liable (J.A. 10) (Pet.App.

A171-A215).

Footnote continued—

sas City, Missouri v. State of Missouri, 592 F.2d 493 (8th Cir.

1979) ; Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 672 F.Supp. 400 (W.D. Mo.

1987); Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 639 F.Supp. 19 (W.D. Mo.

1985); Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 593 F.Supp. 1485 (W.D. Mo.

1984); Black v. State of Missouri, 492 F.Supp. 848 (W.D. Mo.

1980) ; School District of Kansas City, Missouri v. State of Mis

souri, 460 F.Supp. 421 (W.D. Mo. 1978); School District of Kan

sas City, Missouri v. State of Missouri, 438 F.Supp. 830 (W.D.

Mo. 1977).

4

Seventeen months later, on February 5, 1986, the

attorneys filed their initial motion for attorney’s fees and

expenses (J.A. 12). Subsequent motions were filed (J.A.

13) and the fees at issue in the instant case involve

the time period through June 30, 1986 (Pet.App, A 8).

This includes the litigation in the remedial phase of the

case as well as the first year of monitoring the deseg

regation plan. The vast majority of the hours compen

sated, however, was for the period 1981-1984 when the

liability phase of the case was litigated.

The fee issues were extensively briefed by all parties

and a one-day hearing was held on February 27, 1987

(J.A. 16). On May 11, 1987, the district court issued

its order (J.A. 16) (Pet.App. A22). As modified on

July 14, 1987 (Pet.App. A44), the district court awarded

fees and expenses totalling $4,094,443.66, with Benson

awarded $1,728,567.92 and LDF $2,365,875.74 (J.A. 16-17)

(Pet.App. A9).2

The district court awarded Benson an hourly rate

of $200 per hour (Pet.App. A26-A27). The district court

determined that reasonable hourly rates for attorneys

with litigation experience and expertise comparable to

Benson range from $125 to $175 per hour and Benson

“would fall at the higher end of this range” (Pet.App.

A26). This finding was based on 1986 rates and stands

2. While the fee litigation has been pending, the State

has made partial payments to both Benson and the LDF. Of

the $1,728,567.92 awarded to Benson, Petitioners have made

periodic payments totalling $1,147,332.93 (2 /26 /86— $200,000;

6 /2 /86— $100,000; 10 /1 /86— $47,332.93; 8 /3 /87— $300,000;

4 /29 /88— $500,000). Of the $2,365,875.74 awarded to the LDF,

Petitioners have paid $1,350,000 (5 /29 /87— $850,000; 5 /2 /8 8 —

$500,000).

5

in contrast to Benson’s statement that his current billing

rate was $125 per hour,3

The district court enhanced Benson’s rate to $200

per hour, in part, because of preclusion of other employ

ment and undesirability of the case (Pet.App. A26). The

court further found it was “ essential that [Benson’s]

hourly rate include compensation for the delay in pay

ment.” (Pet.App. A26). The district court did not indi

cate what portion of the enhancement was due to delay

in payment.

For Benson’s staff, the district court awarded current

hourly rates. The court noted that for the years the

services were rendered (1982-1984) the average hourly

rate for the two main associates was $60 to $65 per

hour (Pet.App. A28). The court, however, awarded $80

per hour finding the “differential . . . necessary to com

pensate Mr. Benson for the delay in payment” (Pet.App.

A28-A29).

Concerning the LDF, the district court awarded fees

at “ current, rather than historical, rates” to compensate

for delay in payment (Pet.App. A33). The court did

not consider preclusion of other employment or undesir

ability of the case in enhancing the hourly rate for any

attorney other than Benson.

There were a substantial number of nonattorneys

assisting the plaintiffs in this case. These were charac

terized as paralegals, law clerks or recent law graduates.

These labels are irrelevant to the issues in this case and

3. See Motion for Partial Award of Attorneys’ Fees and

Expenses, filed February 5, 1986, p. 10 (Record on Appeal 293,

303).

6

Petitioners will refer to all nonattorney paraprofessionals

as “paralegals.”

The district court awarded current market rates for

paralegal services.4 The court emphasized that it was

compensating for “delay in payment by calculating this

award based upon the current, rather than historical

hourly rates” (Pet.App. A30, A34).

Evidence was presented at the February 27, 1987

fee hearing concerning the actual costs of paralegal ser

vices. LDF indicated that paralegal salaries ranged from

$18,000 to $24,000 annually, which is approximately $8.50

to $11.50 per hour (Transcript of February 27, 1987

hearing, p. 54). Benson testified that most, if not all,

of the paralegals were hired specifically to work on this

case and the average hourly salary was $7 per hour

(Tr. pp. 125-126).5 Considering benefits and other over

head associated with paralegal employees, Petitioners sug

gested that $15 per hour closely approximated the actual

costs of the paralegals hired to work on this case (Pet.

App. A15).

The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit affirmed

the district courts’ orders in all respects. Pertinent to

the issues involved herein, the Eighth Circuit found that

the use of current market rates to compensate for delay

in payment was not prohibited by the Eleventh Amend

ment (Pet.App. A13-A15). The court recognized that

paralegal reimbursement has been treated in various ways

4. The district court awarded $40 per hour for paralegals,

$35 per hour for law clerks and $50 per hour for recent law

graduates (Pet.App. A29, A34).

5. It is interesting to note that Benson’s expert witness,

Kansas City attorney Max Foust, testified that he did not bill

separately for paralegal services (Tr. pp. 73-74).

7

by the courts (Pet.App. A15), but found that the district

courts use of market rates was not clearly erroneous

(Pet.App. A15-A16).

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The controlling principle is that an increase in a fee

award to compensate for delay in payment is equivalent

to an award of interest. This Court’s Library of Congress

decision analyzed this general rule under the fee-shifting

provision of Title VII. This Court held that the federal

government’s waiver of immunity from suit did not also

waive the sovereign’s immunity from liability for interest

on fee awards.

The question is then whether the same express waiver

of immunity from liability for interest or delay required

for the United States is also required for the States’ under

the Eleventh Amendment. This Court has required that

Congress must express an unequivocal intention to waive

the States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity in unmis

takable language in the statute itself. This standard is

virtually identical and intellectually indistinguishable

from the degree of congressional clarity required to find

a waiver of the federal government’s sovereign immunity.

Thus, under 42 U.S.C. § 1988, the States’ Eleventh

Amendment immunity from interest on fee awards has

not been abrogated by Congress. The language of 42

U.S.C. § 1988 does not deal with this issue and the legis

lative history is silent. While § 1988 does allow “attor

ney’s fees as part of costs” , Library of Congress v. Shaw

clearly holds that these terms do not include interest

or compensation for delay.

8

The other issue involved in this case concerns the

proper method of reimbursing paralegal and law clerk

services. Again, there is no indication in either § 1988

or the legislative history addressing this issue. Congress

did express its intention that § 1988 not result in a

“windfall” for attorneys. Permitting reimbursement of

paralegal services at market rates would result in a sub

stantial profit to attorneys over and above the actual

cost of such employees. There is no indication that

Congress intended the attorneys for prevailing parties

to receive a substantial profit on paralegal expense from

the losing party.

Reimbursement of paralegal expense at actual cost

is particularly appropriate in the instant case. The dozens

of paralegals and law clerks employed by the attorneys

for the plaintiff/schoolchildren were hired specifically

for this case. Under such circumstances, reimbursement

at actual cost is equitable to all parties and does not

run contrary to Congress’ intent that attorneys not re

ceive a “windfall” under § 1988.

9

ARGUMENT

I. The Eleventh Amendment prohibits an award of

prejudgment interest or compensation for delay

against a State as part of reasonable attorney’s

fees under 42 U.S.C. § 1988,

In Library of Congress v. Shaw, 478 U.S. 310 (1986),

this Court held that the federal government’s traditional

sovereign immunity prohibited an award of interest or

compensation for delay as part of reasonable attorney’s

fees under Title VII. The question in the instant case

is whether the States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity

prohibits an award of prejudgment interest or compen

sation for delay as part of reasonable attorney’s fees

under 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

A. The conflicting decisions of the Courts of Ap

peals.

This issue has resulted in two conflicting decisions

in the appellate courts. In the instant case, the Court

of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit held that compensa

tion for delay in payment is not prohibited by the Elev

enth Amendment. Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 838 F.2d

260, 266 (8th Cir. 1988). This conflicts with a prior

decision by the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit

which held that prejudgment interest on fee awards or

compensation for delay is prohibited by the Eleventh

Amendment. Rogers v. Okin, 821 F.2d 22, 28 (1st Cir.

1987). In reaching opposite conclusions, the two courts

disagreed on the applicability of Library of Congress v.

Shaw.

10

In Jenkins, the Eighth Circuit declined “to extend

Shaw to the body of Eleventh Amendment law, which

was not covered by [Shaw’s] rationale.” 838 F.2d at

265. The Eighth Circuit assumed, without discussion,

that the rule of statutory interpretation applicable in

suits against the federal government was inapplicable in

an Eleventh Amendment analysis. Id. The Eighth Cir

cuit also refused to equate prejudgment interest with

compensation for delay. Finally, the Eighth Circuit em

phasized that “ courts have regularly interpreted § 1988

to permit compensation for delay in the payment of

fees.” Id.e

In contrast, the First Circuit analyzed the issue in

light of Library of Congress v. Shaw and the legislative

history of 42 U.S.C. § 1988. In addition, unlike the

Eighth Circuit, the First Circuit discussed the critical

issue of Congress’ intent. The First Circuit noted the

holding in Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978), that

§ 1988 abrogated Eleventh Amendment immunity for

attorney’s fees, but emphasized this Court’s Library of

Congress v. Shaw decision that prejudgment interest is

not considered a component of attorney’s fees or costs. 6

6. The cases cited by the Eighth Circuit in support of this

proposition are inapposite, either because a State was not in

volved, or the Eleventh Amendment issue was not raised. See

Light-foot v. Walker, 826 F.2d 516 (7th Cir. 1987) (State in

volved; no discussion of Eleventh Amendment issue); Jordan

v. Multnomah County, 815 F.2d 1258 (9th Cir. 1987) (State not

involved); Daly v. Hill, 790 F.2d 1071 (4th Cir. 1986) (county

involved, not State); Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Ed

ucation, 775 F.2d 1565 (11th Cir. 1985) (State not involved);

Grendel’s Den, Inc. v. Larkin, 749 F.2d 945 (1st Cir. 1984) (State

involved; no discussion of Eleventh Amendment issue); Sisco

v. J.S. Alberici Construction Co., 733 F.2d 55 (8th Cir. 1984)

(State not involved; private defendant); Ramos v. Lamm, 713

F.2d 546 (10th Cir. 1983) (State involved; no discussion of

Eleventh Amendment).

11

Rogers v. Okin, 821 F.2d at 27. Reviewing the legisla

tive history of § 1988, the First Circuit correctly noted

Congress’ silence on whether an attorney’s fee award

should include prejudgment interest. Because “neither

the statutory language nor the legislative history” con

tained a clear indication of Congress’ intent, the First

Circuit refused to “ infer” a waiver of the States’ Elev

enth Amendment immunity from “substantial sums of

prejudgment interest on attorney’s fee awards.” Id. at

27-28.

As discussed below, the First Circuit’s analysis is

consistent with the rationale set forth by this Court in

Library of Congress v. Shaw. More importantly, the

First Circuit’s decision is a faithful adherence to the

rigorous standards established by this Court in numerous

cases addressing congressional waivers of the States’ Elev

enth Amendment immunity.

B. Legislative waiver of the Eleventh Amend

ment must be unequivocal and expressed in

unmistakable language.

The Eleventh Amendment provides:

The Judicial power of the United States shall not

be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity,

commenced or prosecuted against one of the United

States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens

or Subjects of any Foreign State.

This Court has repeatedly emphasized the significance

of this Amendment “lies in its affirmation that the fun

damental principle of sovereign immunity limits the grant

of judicial authority in Art. I ll” of the Constitution.

Atascadero State Hospital v. Scanlon, 473 U.S. 234, 238

12

(1985); Pennhurst State School and Hospital v. Haider -

man, 465 U.S. 89, 98 (1984) (Pennhurst II).

The similarity between the States’ Eleventh Amend

ment immunity and the federal government’s sovereign

immunity is inescapable; both protect the sovereign from

liability. In Library of Congress v. Shaw, this Court

noted that waivers of immunity must be construed

“strictly in favor of the sovereign” and cautioned that

the waiver not be enlarged beyond what the language

requires. 478 U.S. at 318. The court emphasized that

a waiver requires an “affirmative congressional choice.”

Id. at 319 (emphasis added).

The language used by this Court in Eleventh Amend

ment waiver cases is virtually identical to the rigorous

standard articulated in Library of Congress v. Shaw. In

deciding whether Congress has abrogated the Eleventh

Amendment immunity, this Court has required a clear

expression of legislative intent, In Atascadero, this Court

emphasized the “ well-established” requirement that “Con

gress unequivocally express its intention to abrogate the

Eleventh Amendment bar to suits against the States in

federal court.” 473 U.S. at 242.

While this Court has recognized that the Eleventh

Amendment is “necessarily limited by the enforcement

provisions of § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment,” Fitz

patrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445, 456 (1976), this Court

has nonetheless required “ that Congress must express

its intention to abrogate the Eleventh Amendment in

unmistakable language in the statute i t s e l fA ta sc ade r o .

473 U.S. at 243 (emphasis added).

Petitioners recognize that Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S.

678 (1978), held that the Eleventh Amendment did not

prevent an award of attorney’s fees payable by the States

13

when their officials are sued in their official capacities

under § 1988, notwithstanding the fact that the statute

does not contain an express statutory waiver of the States’

immunity. Some may suggest, therefore, that the degree

of congressional clarity required to abrogate the Elev

enth Amendment immunity under § 1988 is less than

that required to waive the federal government’s sov

ereign immunity as discussed in Library of Congress v.

Shaw.

The analysis employed in Hutto v. Finney, however,

has been ignored by this Court in more recent decisions

regarding the standard for congressional waivers of the

Eleventh Amendment. For example, Atascadero repeat

edly emphasizes the requirement of “an unequivocal ex

pression of congressional intent to ‘overturn the consti

tutionally guaranteed immunity of the sovereign states’ ” .

473 U.S. at 240, citing Pennhurst II, 465 U.S. at 99. See

also Atascadero, 473 U.S. at 242 (“Congress unequiv

ocally express its intention” ); at 243 (“ incumbent upon

the federal courts to be certain of Congress’ intent before

finding that federal law overrides the guarantees of the

Eleventh Amendment” ) ; id. (“ the requirement that Con

gress unequivocally express this intention in the statutory

language ensures such certainty” ); id. (“ it is appropriate

that we rely only on the clearest indications in holding

that Congress has enhanced our power” ) ; id. (“Congress

must express its intention to abrogate the Eleventh

Amendment in unmistakable language in the statute it

self” ).7

7. See also Welch v. Texas Department of Highways and

Public Transportation, . U.S...... . , 107 S.Ct. 2941, 2948 (1987)

(“the Court consistently has required an unequivocal expres-

(Continued on following page)

14

Atascadero is a reaffirmation of this Court’s consis

tent holdings on Eleventh Amendment waiver issues. For

example, in Employees v. Missouri Public Health Depart

ment, 411 U.S. 279 (1973), this Court concluded that

Congress did not lift the sovereign immunity of the States

by enacting the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. This

Court emphasized the absence of any indication “by clear

language that the congressional immunity was swept

away.” 411 U.S. at 285. In Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S.

651 (1974), this Court acknowledged a State may waive

its immunity but such a waiver can be found “only where

stated ‘by the most express language or by such over

whelming implication from the text as [will] leave no

room for any other reasonable construction.’ ” 415 U.S.

at 673, quoting Murray v. Wilson Distilling Co., 213 U.S.

151, 171 (1909).

In Quern v. Jordan, 440 U.S. 332 (1979), this Court

held that 42 U.S.C. § 1983 does not override the States’

Eleventh Amendment immunity. This Court further

noted that “general language” used by Congress is not

sufficient to “overturn the constitutionally guaranteed

immunity of the sovereign states.” 440 U.S. at 342 (foot

note omitted).

Footnote continued—

sion that Congress intended to override Eleventh Amendment

immunity” ). In Welch, the Court held that Congress had not

abrogated the States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity under the

Jones Act. 107 S.Ct. at 2947. In so doing, the Court expressly

overruled Parden v. Terminal Railway of Ala. Docks Dept., 377

U.S. 184 (1964), which did not require waiver by “unmistakably

clear language.” Id. at 2948 (Per Justice Powell, with three

Justices concurring, and one Justice concurring in the judgment).

The repudiated Parden analysis is similar to the analysis in

Hutto v. Finney.

15

The Eighth Circuit implies that the standard is more

lenient when reviewing legislation enacted pursuant to

§ 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Atascadero and

Pennhurst cases, however, analyze the Eleventh Amend

ment in terms of Congress’ enforcement powers under

the Fourteenth Amendment. In Pennhurst State School

and Hospital v. Halderman, 451 U.S. 1 (1981) (Penn

hurst I), this Court emphasized that “such legislation

imposes congressional policy on a State involuntarily and

. . . we should not quickly attribute to Congress an

unstated intent . . 451 U.S. at 16. Pennhurst II re

emphasized the requirement of “ an unequivocal expres

sion of congressional intent to overturn the constitution

ally guaranteed immunity of the sovereign states.” 465

U.S. at 99.

Pennhurst II also acknowledges the “vital role of

the doctrine of sovereign immunity in our federal sys

tem.” Id. Atascadero expanded on this concept noting

that in determining whether Congress has abrogated the

Eleventh Amendment immunity, “the courts themselves

must decide whether their own jurisdiction has been

expanded.” 473 U.S. at 243. This Court emphasized

that “ it is appropriate that we rely only on the clearest

indications in holding that Congress has enhanced our

power.” Id.

Thus, this Court has established rigorous guidelines

for finding a congressional abrogation of a sovereign’s

immunity. These strict standards apply when analyzing

both the federal government’s sovereign immunity or

the States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity. Neither 42

U.S.C. § 1988, nor its legislative history, contains the

unmistakable language necessary to find an unequivocal

expression of Congress’ intent.

16

C. 42 U.S.C. § 1988 does not waive the States’

Eleventh Amendment immunity from pre

judgment interest.

It is undisputed that 42 U.S.C. § 1988 does not con

tain any language “ in the statute itself” addressing Elev

enth Amendment immunity. In pertinent part, § 1988

provides:

In any action or proceeding to enforce a provision

of sections 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985, and 1986 of this

title, title IX of Public Law 92-318, or title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the court, in its discre

tion, may allow the prevailing party, other than the

United States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part

of the costs.

Neither does the language of § 1988 explicitly address the

issue of prejudgment interest or compensation for delay.

The question remains whether the language actually used

in the statute includes such compensation by implication.

Again, Library of Congress v. Shaw provides unmis

takable guidance on this issue. There, this Court was con

sidering whether the Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 706 (k),

as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000(e-5)k (Title VII), waived

the federal government’s immunity from interest. 478

U.S. at 313. That statute provides in relevant part:

In any action or proceeding under this subchapter

the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing

party, other than the [EEOC] or the United States,

a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs, and the

[EEOC] and ‘the United States shall be liable for

costs the same as a private person.’

17

Emphasis added. This statute contains the language identi

cal to the relevant portion of 42 U.S.C. § 1988. In fact,

the legislative history of § 1988 notes its reliance of the

“language of Title [] . . . VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964.” S.Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted

in 1976 Code Cong. & Ad.News 5908, 5910.

The phrase “reasonable attorney’s fee as part of costs”

is found in both statutes. Library of Congress v. Shaw

expressly held that the phrase “reasonable attorney’s fee”

did not waive the federal government’s sovereign im

munity from interest. 478 U.S. at 320. This Court further

held that the term “ costs” did not waive the federal govern

ment’s sovereign immunity from interest. Id. at 321.8

If Library of Congress v. Shaw is applied consistently,

then the identical language used in 42 U.S.C. § 1988 also

does not evidence Congress’ intent to waive the States’

Eleventh Amendment immunity for prejudgment interest

or compensation for delay. It would be anomalous to

suggest that Congress intended a waiver of immunity

under § 1988 by use of the phrases “reasonable attorney’s

fee” and “costs” and did not intend such a waiver when

using the identical phrases in Title VII.

Petitioners’ position is supported by congressional ac

tion in another fee-shifting statute. The 1985 amendments

to the Equal Access to Justice Act (EAJA) explicitly per

mit adjustments to compensate attorneys for “ increasefs]

in the cost of living.” 28 U.S.C. § 2412(d )(2 )(A ). Thus,

when Congress has intended to increase fee awards to

8. Library of Congress v. Shaw further held that the phrase

“the United States shall be liable for costs the same as a private

person” did not evidence the “requisite affirmative congressional

choice” to waive sovereign immunity. 478 U.S. at 319.

18

compensate for delay, it has done so expressly in the

language of the statute.8

The First Circuit correctly noted that the “legislative

history . . . is completely silent on the subject of pre

judgment interest.” Rogers v. Okin, 821 F.2d at 22. The

Senate Report does state that “citizens must have the

opportunity to recover what it costs them to vindicate

[their civil rights] in court.” See S.Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess,, reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad.

News 5908, 5910. Hutto v. Finney also suggests that

“ Congress [may] amend its definition of taxable costs and

have the amended class of costs applied to the States . . .

without expressly stating that it intends to abrogate the

States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity.” 437 U.S. at

696.9 10

This Court, however, has emphasized that prejudg

ment interest, compensation for delay, or whatever term

9. Similarly, when Congress has intended to waive the

United States’ immunity from interest, it has done so in ex

press language. See, e.g., 28 U.S.C. § 2411 (expressly authoriz

ing pre- and post-judgment interest payable by the United

States in tax refund cases). Congress has also reiterated the

general rule that interest cannot be allowed absent express

waiver. See 28 U.S.C. § 2516 ( “Interest on a claim against

the United States shall be allowed in a judgment of the United

States Claims Court only under a contract or Act of Congress

expressly providing for payment thereof” ) ; 28 U.S.C. § 2674

(“The United States . . . shall not be liable for interest prior to

judgment” under the Federal Torts Claim Act).

10. In light of subsequent decisions by this Court, par

ticularly Atascadero, a reasonable argument could be made that

the apparently more lenient standard set forth in Hutto v. Finney

is no longer valid. Because Hutto v. Finney appears to have

been superseded in this Court’s subsequent Eleventh Amendment

waiver decisions, its scope should not be expanded. To hold

that § 1988 implicitly allows recovery of prejudgment interest or

compensation for delay in payment would cast doubt on the

Eleventh Amendment analysis set forth in Atascadero, Quern,

Edelman, Pennhurst 1, Pennhurst 11, and Welch.

19

used to describe compensation for the time value of money

is not a component of “ costs.” “Costs” is a term of spe

cific and narrow content; in federal adjudication, the word

“ costs” has never been understood to include any interest

component. 28 U.S.C. § 1920. See also 10 C. Wright, A.

Miller & M. Kane, Federal Practice and Procedure '§§

2666, 2670 (2d ed. 1983). Historically, prejudgment in

terest has been viewed as an element of damages, not as

a component of “costs.” Id. § 2664, at 159-60.

In Library of Congress v. Shaw, this Court reiterated

that “prejudgment interest is considered as damages, not

a component of ‘costs’ . . . A statute allowing costs, and

within that category, attorney’s fees, does not provide

the clear affirmative intent of Congress to waive the

sovereign’s immunity.” 478 U.S. at 321. Therefore, this

Court emphasized that the “requirement of a separate

waiver reflects the historical view that interest is an

element of damages separate from the damages on the

substantive claim.” Id. at 314 (emphasis added), citing

C. McCormick, Damages § 50, p. 205 (1935).

Hutto v. Finney actually supports, rather than dis

putes, petitioners’ position on this issue. There, this Court

indicated that “ it would be absurd to require an express

reference to State litigants whenever a filing fee, or a

new item, such as an expert witness’ fee, is added to

the category of taxable costs.” 437 U.S. at 696-97. In

a footnote, however, this Court indicated that the analysis

might be different “if Congress were to expand the con

cept of costs beyond the traditional category of litigation

expenses.” 437 U.S. at 697, note 27. Because prejudg

ment interest or compensation for delay is not a tradi

tional component of costs, but rather considered as dam

20

ages, a clear affirmative indication from Congress is nec

essary to waive immunity therefrom.

The legislative history of § 1988, however, contains

no indication that Congress intended to expand the tra

ditional components of costs to include prejudgment in

terest. The legislative history identifies four cases as

reflecting the appropriate standards for calculating fee

awards. See S.Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.,

reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad.News 5908, 5913.

None of the four cases, however, addressed the issue of

prejudgment interest or compensation for delay.11

The Eighth Circuit attempted to avoid the holding

of Library of Congress v. Shaw by refusing to equate

interest with compensation for delay. Jenkins, 838 F.2d

at 265. The court approved the district court’s consid

eration of “delay as one factor in setting the hourly

fee.” Id. In Library of Congress v. Shaw, however,

this Court cautioned that “the no-interest rule cannot

be avoided simply by devising a new name for an old

institution.” 478 U.S. at 321. There, the respondent

argued that interest and a delay factor had distinct pur

poses. Id. at 322. This Court rejected that argument

noting that interest and a delay factor share an identical

function, both “ designed to compensate for the belated

receipt of money.” Id.

11. See Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974) (sets forth twelve factors to consider in

determining fee awards, not one of which expressly or implicitly

deals with prejudgment interest); Stanford Daily v. Zurcher,

64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974) (follows modified Johnson ap

proach, no discussion of interest); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

hurg Board of Education, 66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D. N.C. 1975) (no

discussion of interest); Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D.

I 9444 (C.D. Cal. 1974) (no discussion of interest).

21

The compensation for delay is intellectually indis

tinguishable from prejudgment interest; both function to

compensate the attorney for the delayed receipt of fees.

The First Circuit analysis of this issue is consistent with

the standards this Court clearly articulated in Library

of Congress v. Shaw. See Rogers v. Okin, 821 F.2d at 26.

The lower courts have consistently applied Library

of Congress v. Shaw to prohibit interest on fee awards

against the federal government whether it be called pre

judgment interest, compensation for delay or compensa

tion at current billing rates. See, e.g., Thompson v. Ken-

nickell, 836 F.2d 616, 619 (D.C. Cir. 1988) (“ Shaw

precludes . . . use of current billing rates for work

performed under the Equal Pay Act” ); Greater Los

Angeles Council on Deafness v. Community Television of

Southern California, 813 F.2d 217 (9th Cir. 1987) (Re

habilitation Act case - Shaw “prohibit[s] the use of a

multiplier to enhance fee awards because of delay in

payment” ); Utah International, Inc. v. Department of

Interior, 643 F.Supp. 810, 830 (D. Utah 1986) (“ com

pensation for delay is the equivalent of interest” ).12

The cases discussed in Part I B, supra, hold that an

unequivocal expression of Congress’ intent is required to

override the States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity.

Hutto v. Finney recognizes that the “reasons for requiring

a formal indication of Congress’ intent . . . insures that

Congress has not imposed ‘enormous fiscal burdens on

12. While not citing Library of Congress v. Shaw, the Court

of Appeals for the Third Circuit has held that prejudgment in

terest could not be awarded under FELA. Poleto v. Consolidated

Rail Corporation, 826 F.2d 1270, 1279 (3rd Cir. 1987). While

the court recognized strong policy considerations in favor of

such an award, it noted the decision was for Congress to make.

Id. at 1274-79.

22

the States’ without careful thought.” 437 U.S. at 697,

note 27, citing Employees v. Missouri Public Health

Department, 411 U.S. 279, 284 (1973). Since Hutto

v. Finney, the Court has reemphasized that “ [t]he case

for inferring intent is at its weakest where . . . the

rights asserted impose affirmative obligations on the

States . . ., since we may assume that Congress will not

implicitly attempt to impose massive financial obligations

on the States.” Pennhurst State School and Hospital v.

Halderman, 451 U.S. 1, 16-17 (1981) (emphasis in the

original) (Pennhurst I ) .

As demonstrated above, the terms used in § 1988—

reasonable attorney’s fees and costs—do not include the

concept of prejudgment interest or compensation for delay.

Therefore, there is certainly no unequivocal evidence of

Congress’ intent to impose what could be a substantial

obligation on the States. Undeniably, prejudgment in

terest can result in a substantial financial obligation. In

Rogers v. Okin, supra, the First Circuit’s recalculation

based on historical rates resulted in a total reduction of

about 40%, or approximately $600,000 of a $1.47 million

fee award. In the case at bar, similar reductions are

anticipated although the exact calculations would be de

termined on remand.13

13. The use of current rates in the case at bar inflated

the fee award more than usual. The plaintiff/schoolchildren

became prevailing parties on September 17, 1984 when the dis

trict court issued its liability orders (Pet.App. A171), The

initial motion for attorney’s fees was not filed until seventeen

months later on February 5, 1986 (J.A. 12) and 1986 hourly

rates were requested. Had the motion been filed in 1984, the

hourly rates requested presumably would have been based on

1984 rates. Because the vast majority of the hours compensated

were spent on the discovery and liability phase of the litigation,

the attorneys were, in effect, rewarded for delaying the fee

application.

23

The use of current market rates to compensate for

delay in payment is in effect an award of prejudgment

interest. It thus becomes a retroactive award of damages,

which is clearly prohibited by the Eleventh Amendment.

Edelman v. Jordan held that a federal court’s remedial

power, consistent with the Eleventh Amendment, is lim

ited to prospective injunctive relief and may not include

a retroactive award requiring payment of damages from

the state treasury. 415 U.S. at 677.

Thus, the Eleventh Amendment is a limitation on the

type of relief a party may receive from a State. See

Florida Department of State v. Treasure Salvors, Inc.,

458 U.S. 670, 689 (1982) (“ [Eleventh] Amendment places

a limit on the relief that may be obtained by the plain

tiff” ). While under Hutto v. Finney, § 1988 allows for

recovery of attorney’s fees and costs, the Eleventh Amend

ment still protects the States from a separate assessment

of prejudgment interest.

There may be reasonable policy reasons to compen

sate civil rights attorneys for the time value of money

on fee awards. The vindication of constitutional rights

is a legitimate goal of Congress and obviously, the more

money lawyers make on civil rights cases, the more civil

rights cases will be litigated. In § 1988, however, Con

gress clearly indicated that other factors had been con

sidered and specifically cautioned that § 1988 should not

produce a windfall for attorneys.

Policy arguments, however, should be addressed to

Congress. In Library of Congress v. Shaw, this Court

emphasized that “policy, no matter how compelling, is

insufficient, standing alone, to waive . . . immunity.” 478

U.S. at 321. See also United States v. N.Y. Rayon Im-

24

porting Co., 329 U.S. 654, 662 (1947), (Courts lack the

power to award interest against the United States on

the basis of what they think is or is not sound policy).

II. Reimbursing the actual cost of paralegal and law

clerk services is appropriate under the facts of

this case.

At the current time, there are at least three different

approaches to the problem of compensating paralegal ser

vices.14 Some courts consider paralegal services a part

of normal office overhead and completely deny separate

reimbursement. See, e.g. Roe v. City of Chicago, 586

F.Supp. 513, 516 (N.D. 111. 1984). Others reimburse the

actual costs of such services. See Lamphere v. Brown

University, 610 F.2d 46, 48 (1st Cir. 1979) (reimburse

ment at actual cost when paralegals hired specifically

for purpose of a certain litigation, as in the instant case).

See also Greenspan v. Automobile Club of Michigan, 536

F.Supp. 411, 415 (E.D. Mich. 1982); Ross v. Saltmarsh,

521 F.Supp. 753 (S.D. N.Y. 1981), affd, 688 F.2d 816

(2nd Cir. 1982). Other courts have reimbursed at mar

ket rates. See, e.g. Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546, 558-59

(10th Cir. 1983). While the policies behind each of these

methods differ, one thing is clear from the confusion

between the lower courts—Congress has not clearly stated

its intention on this issue. Given such uncertainty, this

Court should not imply what could be a substantial finan

cial obligation on the States.

In Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness So

ciety, 421 U.S. 240 (1975), this Court held that absent

14. A similar issue concerning compensation for paralegal

expense is currently before this Court in Blanchard v. Bergeron,

No. 87-1485 (cert, granted June 27, 1988).

2 5

Congressional authorization, courts lack the inherent

power to award attorney’s fees to prevailing litigants.

As this Court stated, Congress has not “extended any

roving authority to the judiciary to allow counsel fees

as costs or otherwise whenever the courts might deem

them warranted.” Alyeska, 421 U.S. at 260. Congress

enacted 42 U.S.C. § 1988 as a reaction to Alyeska. See

City of Riverside v. Rivera, 477 U.S. 561 (1986). How

ever, the statute only modified the Alyeska decision

for the matters specified within it, i.e., allowing a rea

sonable attorney’s fee as a part of costs. There is no

indication whatsoever in the statute that prevailing lit

igants are entitled to a reasonable paralegal fee as part

of their costs. Therefore, Alyeska controls the result of

this case with regard to paralegal fees, and the judgment

should be reversed and the case remanded. If federal

courts do not have any power to award attorney’s fees

without Congressional authorization, they surely do not

have the power to award paralegal fees at market rates

without Congressional authorization.15

The Petitioners’ approach to this issue is also sup

ported by the ordinary rules of statutory construction.

In construing a statute, the Supreme Court construes

what Congress has written and does not add, subtract,

delete or distort the words used. 62 Cases of Jam v.

United States, 340 U.S. 593, 596 (1951). The Fourth

Circuit has stated

15. A persuasive argument could be made that paralegal

fees should be included in the attorney’s reasonable hourly rate

as numerous cases have done. In the instant case, however, the

State has taken the position that the actual cost method be used.

Because the paralegals were employed specifically for this litiga

tion, the State believes the actual cost method is an equitable

resolution of this issue.

26

[W ]e do not think it permissible to construe a stat

ute on the basis of a mere surmise as to what the

legislature intended and to assume that it was only

by inadvertence that it failed to state something

other than what it plainly stated.

United States v. Deluxe Cleaners and Laundry, Inc., 511

F.2d 926, 929 (4th Cir. 1975). Additionally, “ [cjourts are

not authorized to rewrite a statute because they might

deem its effects susceptible of improvement.” Badaracco

v. C.I.R., 464 U.S. 386, 398 (1984); TV A v. Hill, 437 U.S.

153, 194-95 (1978). Therefore, as there is no discussion

of paralegal fees in the statute, market rates should not

be awarded against the State.

Further, reimbursing paralegal services at market

rates would produce a windfall to attorneys as these mar

ket rates have a built in profit factor within them. As

the legislative history indicates, § 1988 was never intended

to produce windfalls to attorneys. See S.Rep. No. 94-1011,

94th Cong., 6, reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad.

News, 5908, 5913 (cited in Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886,

893-94 (1984)). The legislative history is also silent on

whether paralegal and law clerk fees are to be awarded

and at what rates.16 Since Congress has not spoken on

this issue, there is no clear indication of Congressional

intent and this Court should not rewrite § 1988 to serve

any policy purpose.

16. Only one case cited in the legislative history included

any reference to paralegal reimbursement. In Davis v. County

of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 9444 (C.D. Cal. 1974), paralegals and

law clerks were awarded rates of $10 per hour. The Senate

Report, however, cites the case only for its correct applicaton

of the Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714 (5th

Cir. 1974), factors, none of which deal with law clerk and para

legal fees.

2 7

The acceptance of the State’s position that paralegal

expenses should only be awarded at actual costs would

also make those costs easier to calculate. The attorney

requesting paralegal costs would simply reveal through

financial records how much the paralegals were generally

paid per hour, including benefits. This would avoid un

necessary litigation over this issue. Cf., Hensley v. Ecker-

hart, 461 U.S. 424, 437 (1983) (fee request should not

result in a second major litigation).

In the instant case, the use of market rates results

in a huge profit to the attorneys. The record reflects

that the average salary range for the paralegals was be

tween $7 and $11 per hour. For easy calculation, the

State suggested that $15 per hour closely approximated

the actual costs of such employees when benefits and

other overhead are considered. Reimbursing these hours

at $35, $40 or $50 per hour results in an unjustified wind

fall. These paralegals were hired specifically for this case

and are an expense incurred.

Therefore, reimbursement at actual cost is the ap

propriate method for compensation. This takes into ac

count the various interests indicated by Congress. Pre

vailing plaintiffs receive the reasonable costs of such

services and the attorneys do not receive a windfall at

the expense of Missouri taxpayers.

28

CONCLUSION

This case is a straightforward application of the prin

ciples discussed in Library of Congress v. Shaw. Con

gressional abrogation of immunity must be clearly ex

pressed. In the Eleventh Amendment context, Atascadero

requires an unequivocal expression of intent in unmistak

able language that the States’ Eleventh Amendment im

munity has been waived. The reasoning of the court

below is erroneous because it does not defer to the rigor

ous standards required for waivers of immunity.

42 U.S.C. § 1988 does not address, either explicitly or

by implication, compensation for delay or prejudgment

interest on fee awards. Under such circumstances, the

Eleventh Amendment retains sufficient vitality to pro

hibit the assessment of this separate, retroactive financial

obligation on the States.

Further, under the factual circumstances of this case,

paralegal services should be reimbursed at actual costs.

The paralegals were hired specifically to assist in the

prosecution of this case. Reimbursement at actual costs

results in fair compensation, but does not provide a wind

fall at taxpayer expense.

Accordingly, for all the above reasons, Petitioners

pray this honorable Court to reverse the decision of the

court of appeals and to remand this case for a redetermina

tion of the attorney’s fees award. On remand, the district

court would determine the historical hourly rates to be

used in calculating the lodestar. The court would also

29

recalculate the award for paralegal services based on

actual costs.

Respectfully submitted,

W il l ia m L. W ebster

Attorney General

T erry A llen

Deputy Attorney General

Supreme Court Building

Jefferson City, Missouri 65102

(314) 751-3321

M ichael L. B o ico ur t*

Assistant Attorney General

B ruce F ar m er

B art A. M atan ic

Assistant Attorneys General

Counsel for Petitioners

Counsel of Record

~ mm i

- ■ ' • ' ■ < : '^-;;-:: 'r ‘■"";: -v-—V . "v-v." . ' ' . . - :

: ; , < •

liSBS

; ■ - - /■• • , - /- . - . ' *-

’wmrns^mi

lip fg lii jj|l JiBSSSi

iiy tS * - ■

' , ’r̂