Lee v. Macon County Board of Education Petition for Rehearing with Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lee v. Macon County Board of Education Petition for Rehearing with Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc, 1973. 0cc7f004-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/256a9f07-8d8c-4fdf-b7d0-5b64b32be65b/lee-v-macon-county-board-of-education-petition-for-rehearing-with-suggestion-for-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

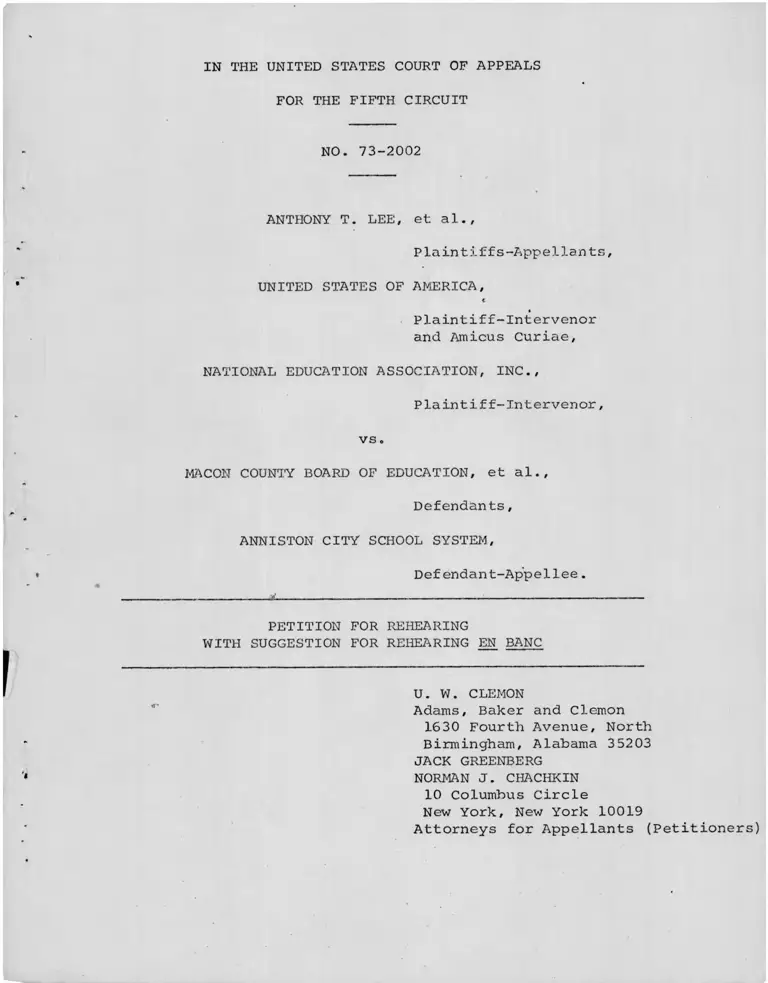

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-2002

ANTHONY T. LEE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,<

Plaintiff-Intervenor

and Amicus Curiae,

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, INC.,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

vs.

MACON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants,

ANNISTON CITY SCHOOL SYSTEM,

Defendant-Appellee.

---------- 1L----------------- ------- -----------------

PETITION FOR REHEARING

WITH SUGGESTION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

U. W. CLEMON

Adams, Baker and de m o n

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants (Petitioners)

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-2002

ANTHONY T. LEE, et al.,

«

Plaint if fs-Ap'pellan ts,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor

and Amicus Curiae,

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, INC.,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

vs.

MACON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants, •

ANNISTON CITY SCHOOL SYSTEM,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court

____ for the Northern District of Alabama

PETITION FOR REHEARING

WITH SUGGESTION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

Appellants, by their undersigned counsel, respect

fully pray that this Court grant rehearing of the August 10,

1973 decision by a panel in this cause. Appellants further

respectfully suggest the appropriateness of a rehearing en

banc in this matter, should the panel to which this Petition

is addressed in the first instance decline to disturb its

judgment, because the panel's decision is in conflict with

many other school desegregation rulings of this Circuit.

Background of the Appeal

♦This case involves school desegregation in Anniston,

Alabama; the present appeal is the first consideration by this

Court on the merits of desegregation plans for Anniston since

the Supreme Court's decisions in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Educ♦, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) and companion cases.-

Following the filing of a Motion for Supplemental

Relief by the plaintiff-intervenor United States on March 4,

1971, seeking adoption of a new plan of desegregation, the

district court on October 1, 1971 directed the school board

¥

to produce such a plan. Hearings and further proceedings

resulted, however, in an August 15, 1972 district court decree

retaining, with minor modification, the 1970 attendance scheme.

*r

The United States appealed to this Court from that decree,

1/ In 1970, the same panel of this Court approved an Anniston

plan utilizing "a strict neighborhood system" without trans

portation, relying upon Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction

of Orange County, 423 F.2d 203 (5th Cir. 1970). 429 F.2d

1218. See Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile County,

430 F .2d 883 (5th Cir. 1970), rev'd 402 U.S. 33 (1971).

-2-

but that appeal was ultimately remanded on the joint motion

of the United States and the school board to permit "the

Anniston City Board of Education to present and support a

recently adopted plan of student and faculty desegregation

• • • •" Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., No. 72-2982 (5th

Cir., December 20, 1972).

Shortly thereafter, the present appellants (the

private plaintiffs in this litigation) filed objections "to

the plan of desegregation herein before filed or hereinafter

to be filed by the Anniston School Board with the approval of

2/

the United States Department of Justice" (8a).

The objections filed by the private plaintiffs re

quested that the district court schedule an early evidentiary

hearing (9a) and also particularized opposition to the plan's

failure to alter the identifiably black character of the

ii

Cooper and Randolph Park Elementary Schools or the identifiably

white Norwood and Golden Springs Schools (8a). When the plan

was formally tendered on February 20, 1973 it was accompanied

by a joint motion signed by the United States and the school

board which asserts that it was "in conformity with the require

ments of Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) . . . ."

Private plaintiffs have never indicated any agreement with that

2/ Citations in this form are to the reproduced Record on

Appeal in this case, No. 73-2002.

-3-

proposition, but on April 9, 1973 the district court approved

the board's plan with neither an evidentiary hearing nor any

discussion of its reasoning (14a-15a). This appeal followed.

The Plan Approved Below

Anniston is a small school system in northern Ala

bama (see maps attached to Brief for the United States on this

appeal). In 1972-73 it enrolled 51.3% black students; it

operated two high schools (25% and 98% black), two junior high

schools (24% and 98% black), and 11 regular elementary schools:

four less than 5% black, three over 94.9% black, and one 85%

black (id.).

For 1973-74 the school board and the United States

projected a total student body 50.7% black; grade duplication

at the secondary level was to be ended with all students assigned

to single attendance centers for grades 7-12. The closing of

five elementary schools and transfer of their pupils to a for

mer junior high school would reduce the number of elementary

grade centers to six; of these, however, two were projected

all-white and a third more than 97% white, and two over 93%

black (id.). One black and one white school (Cooper and Norwood)

are contiguous (see map, id.).

The plan utilizes no pairing (contiguous or non

contiguous) , grouping, or non-contiguous zoning at the elem

entary level. 43% of all black elementary students will

-4-

attend the two virtually all-black schools, while 59% of

white elementary pupils will be assigned to virtually all-

white schools (id.) . 51% of all elementary students will

attend virtually one-race schools.

The district court simply approved the plan without

discussing this feature.

The Panel's Ruling

On appeal, the panel affirmed the district court's

. . . . . 3/decision m a per curiam opinion. It ruled that there was

no error in accepting the board's plan without a hearing since

ta]il of the facts concerning the several alternatives for

desegregating the Anniston schools" were developed at prior

hearings in the case. The opinion further implies that, in

any event, private plaintiffs waived their right to a hearing

on their objections to the board's plan because their counsel

a

did not participate in the earlier hearings. Finally, the

panel sustains the district court's action on the ground that

it was within the court's "reasonable discretion under the

circumstances to accept a plan which places a majority of

elementary students in the Anniston system in schools which

remain clearly identifiable, one-race schools.

—/ A copy of the panel's opinion is attached hereto as Appendix

-5-

REASONS FOR GRANTING REHEARING

Rehearing should be granted in this case to correct

the manifest injustice which has occurred, to bring to an

end as soon as possible the continuation of unconstitutional

segregation in the Anniston public schools, and to eliminate

divergent approaches to school desegregation cases among

different panels of this Court.

1. The panel evidently misconceived the nature of

the proceedings below in light of the district court's state

ment that it was modifying the board's plan upon consideration

4/

of plaintiffs' objections. The plan was presented to the

district court as a "compromise" between the United States and

. . 5/the Anniston school board. Yet despite the expressed objec

tions of the private plaintiffs, the district court approved

the plan without an evidentiary hearing, in an order which

fails to find that the plan satisfies the constitutional re

quirements .

This Court has recently held such procedures to be

4/ The changes related to reporting and transfers, and did

not affect the student assignment plan.

5 / The Brief for the United States on this appeal states (p.

18) :

The district court's order should be viewed

in the context of the prior proceedings and

negotiations. . . . Under these circumstances

each party compromised.

As we note in the text, however, each party did not compromise,

but private plaintiffs made known their serious objection to

the plan and their doubt as to its constitutionality.

-6-

inappropriate in school desegregation cases which, like this

one, are class actions brought to protect the constitutional

rights of minor black schoolchildren. Calhoun v. Cook, No.

73-2020 (5th Cir., August 21, 1973):

. . . the entry of an order enforcing

an alleged settlement agreement without

a plenary hearing is improper. Massa

chusetts Insurance Company v. Forman,

469 F .2d 259 (5th Cir. 1972). In the

present case no evidentiary hearing was

ever conducted to determine that a

viable compromise embodying a consti

tutional plan was reached. [slip op. at

p. 3]

The problem is a particularly serious one in cases

such as this where the United States seeks to compromise and

emasculate the constitutional rights of the very students

whose interests they are allegedly protecting. Cf. Alexander

v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969).

2. Private plaintiffs did not lose their right to

equal protection of the laws because their counsel did not

participate in 1971 hearings in this cause,

opinion, however, seems to indicate that the

had no obligation at all to consider private

The panel's

district court

plaintiffs 1

objections to the "compromise" desegregation plan:

. . . The district court nevertheless

considered the objections raised by

appellants and made some changes sug

gested by them. [slip op. at p. 5]

[emphasis supplied]

The reason counsel for private plaintiffs had not taken part

-7-

frankly in appellants' Reply Brief (pp. 3-4):

As counsel for the United States, the

Anniston school board and the court

below are all well aware, original

counsel for private plaintiffs herein

found themselves in the impossible

position of representing practically

all of the black school children in

more than a hundred school systems

throughout the State of Alabama by

virtue of the landmark Lee v.'Macon

County [decision], 267 F. Supp. 458.

Unlike the United States with its

legions of lawyers, original counsel

for private plaintiffs could not con

ceivably be physically present for

each hearing in every school desegre

gation case in the three federal

district courts of the State of Alabama.

In many of these cases, Anniston inclu

ded, original counsel for private plain

tiffs were limited to reviewing the

developments in the cases wherein the

United States was a party plaintiff-

intervenor, under the apparently

mistaken belief that surely after

Alexander v. Holmes County, [supra],

the United States would not again

seek to compromise the present right of

black schoolchildren to attend unitary

schools.

Surely Anniston's black pupils did not waive their constitu

tional rights to object to a 1973 desegregation plan because

their lawyers did not take part in 1971 hearings on entirely

different plans, which resulted in interim orders which were,

in fact, appealed by the Department of Justice! The inescapable

6/fact is that private plaintiffs seasonably made known to

in the 1971 district court hearings was set forth fully and

6/ The panel writes that these objections were "prematurely

filed" [slip op. at p. 3] since the plan was not formally

-8-

the district court, and the parties, their objections to the

plan agreed to by the school board and the government. What

happened in 1971 is totally irrelevant to their right to

have these objections considered by the district court and

this Court.

3. Nothing in the record supports the panel's

conclusion that an evidentiary hearing would ‘have proved

futile. Indeed, the judgment that "[a] further hearing would

not be productive of any information not already fully

available to the court as the result of prior hearings" [slip

op. at p. 5] is not merely speculative, but one which an

appellate court is hardly in a position to make. Compare

Calhoun v. Cook, supra■ We pointed out in our Reply Brief

on this appeal that the 1971 hearings did not, in fact, fully

explore all desegregation alternatives. And it should go

without saying that the closing of five elementary schools

gives rise to infinitely greater possibilities which could

not have been contemplated in 1971.«r*

4. The plan approved by the district court clearly

fails to meet constitutional standards. As we noted above,

6/ (continued) tendered until February 20, 1973. But the

plan for presentation of which the prior appeal was

remanded had been adopted by the school board as early as

November 15, 1972. See Motion for Extension of Time to File

Appellant's [United States'] Brief in No. 72-2982, dated

November 24, 1972.

-9-

Anniston is a small school system. It has traditionally

utilized bus transportation for student assignments by

subsidizing the cost of tickets on the transit system in the

city; in 1969-70, nearly 50% of Anniston students received

free tickets (Tr. of March 6 , 1970, pp. 18-19 [attached here

to as Appendix "B"]). Under the order of the district court,

more than half of all elementary students in the system will

attend schools which are more than 97% white or 93% black.

One of the white schools and one of the black schools are

contiguous. Yet the plan does not pair these, or any other,

schools— nor does it utilize pupil transportation to eliminate

the remaining one-race schools. If this Court erred in

failing to consider transportation in Davis v. Board of School

Comm'rs of Mobile, supra, surely this plan cannot pass

constitutional muster.

We recognize that the district court's order

requires further consideration of methods to eliminate the

two virtually all-black schools for the 1974-75 school year.

But'the panel's affirmance in no way suggests (quite apart

from Alexander and Carter difficulties) that these schools,

and the three white schools, must be desegregated.

5. The panel's ruling conflicts with other decision

of this Court. While there are differences of opinion among

-10-

the Judges of this Circuit, see United States v. Texas Educ.

Agency, 467 F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972) and Cisneros v. Corpus

Christi Independent School Dist., 467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972),

we are aware of no other post-Swann ruling of this Court which

accepts as constitutionally permissible such an abysmally low

level of desegregation in a system where more is clearly feasible.

We have discussed above the holding of this Court

with respect to "compromise" settlements in Calhoun v. Cook.

In its failure to require the use of transportation to

desegregate the Anniston elementary schools, the Anniston

decision conflicts with Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of

Mobile, supra, among others. Whether or not Anniston previously

used busing, and to what extent, is irrelevant to the achieve

ment of the constitutional result. Brown v. Board of Educ.

of Bessemer, 464 F.2d 382 (5th Cir. 1972); United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School Dist,, 460 F.2d 1205 (5th

Cir. 1972). In failing to require even contiguous pairing

of Cooper and Norwood, the panel retreates from even such

pre-Swann decisions as Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction

of Hillsborough County, 427 F.2d 874 (5th Cir. 1970) and

Allen v. Board of Public Instruction of Broward County, 432

F.2d 362 (5th Cir. 1970). Its acquiescence in the maintenance

of both black and white elementary schools stands in sharp

contrast to such rulings as Harrington v. Colquitt County

Bd. of Educ., 460 F.2d 193 (5th Cir. 1972).

-11-

These conflicts are serious and important. They

recall those which existed in this Circuit between the

decision of Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange

County, supra, by the same panel, and Davis v. Board of

School Comm'rs of Mobile, supra, by the Supreme Court. They

should be resolved, and the Constitution enforced, by

reconsideration of this appeal and reversal of the district

court, consistent with Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ.,

supra, and Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396

U.S. 290 (1970).

WHEREFORE, appellants respectfully pray that

rehearing, or rehearing en_ banc, be granted, and that upon

such reconsideration, the judgment belcrw be reversed and

the cause remanded to the district court with instructions

to require submission and implementation by the second

semester of the 1973-74 school year, of an plan to fully

desegregate all of the elementary schools in the Anniston

City School System. Appellants further pray that upon such

rehearing this Court grant them their costs and an award of

reasonable attorneys' fees pursuant to §718 of the Education

Amendments of 1972.

Respectfully submitted,c.

U.W. CLEMON

Adams, Baker and demon

1630 Fourth Avenue, N.

Birmingham, Ala. 35203

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants (Petitioners)

-12-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 6 th day of September,

1973, I served a copy of the foregoing Petition for Rehearing

With Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc upon counsel for the

parties herein by mailing them, air mail special delivery

postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

♦

Paul F. Hancock

Attorney

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

Walter J. Merrill

8th Floor

Commercial National Bank Bldg.

Anniston, Alabama 36201

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

¥

iT

-13-

IN T H E

United States Court of Appeals

FO R T H E FIFT H CIRCU IT

N o . 7 3 - 2 0 0 2

A N TH O N Y T. LEE, E T AL.,

P lain tiffs-A ppellan ts,

U N ITED ST A T E S O F A M ER ICA ,

Plaintiff-Intervenor

and A m icus Curiae,

N A TIO N A L ED U CATIO N A SSO CIA TIO N , INC.,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

versus

M ACON CO UNTY BO ARD O F ED U CA TIO N , E T A L .,

D efendants,

* A N N ISTO N CITY SCH O O L SY STEM ,

D efendant-A ppellee.

Appeal from the United States D istrict Court for the

Northern District of A labam a

(August 10, 1973)

Before BELL, AINSWORTH and GODBOLD,

Circuit Judges.

2 L E E , ET AL. V. MACON CTY. ED. OF EDUC

P ER CURIAM- This « £ « £ ? £ £ £

appellants involves a Alabama, City Board

desegregation o at3r,roved on April 9, 1973>Of Education which was P pf ^ Board and

the district court, on ]omi

the United States.

A short chronological history of this

niston, by our decision in th ^ implemented

1970. See 429 F.2d 12 ■ ph 4 1971, the United

in the 1970-71 schoo year. to require the Board

States moved the dist des ation. A consent or-

to prepare a new p f ̂ "g71 providing for strict

der was entered on ’ es Then, on Oc-

enforcement of attendance zon filing of

tober 1. 1971. the distnccourt o r d e r ^ ^ ^ their

a new plan by October , . ring for

obieStions to H by N ov em b er^ , a n d ^ s e ^ s ^

November 18 and 19. ■ ^ response thercl0. No

and the United States aooellants. The hear-

objection to the plan was Med J " la and 19 and ing was held by the court on November ^

l o e s s e s testified — Appellants,

the objection thereto of t hearing. There-

however, did not P ™ * » ® requested an

after, on December 28, 1971, the pf fte Ap.

order from the- court to ° School Systems

S p” / occasioned

^ ^ = - - = ^ 0 0 and sub-

mitted a voluminous report which, with a new deseg

regation plan, was filed by the Board on May 10, 1972.

A further hearing was held on June 19, 1972, after the

United States had filed its response to the alternate

plan objecting thereto, and testimony was taken. Ap

pellants did not participate in the heading. §

The district court issued its order approving the plan

with some modifications on August 15, 1972, and the

United States appealed on August 30, 1972. Appellants

who had not participated in any of the hearings l

not appeal nor did they join the United States i m s

appeal.1 While the case was on appeal the United

States and the Board jointly requested that we vacate

the August 15, 1972 order and remand the case to the

district court that a new plan might be presented. We

granted the motion on December 20, 1972.2

LEE, ET AL. v. MACON CTY. BD. OF EDUC. 3

On January 9, 1973, appellants prematurely filed ob

jections to the proposed plan, but the plan was not

actually filed with the court until February 20, 1973

4

,Thc United States asserts in its briet (p. 5) that plaintiffs were

served copies of all documents filed by the Government and

vupro notified of each hearing date.

aAfter the appeal from the August 15, 1572 order was Judged

with the court, we are informed by the Board and the United

States that voluntary negotiations were entered into in

attempt to resolve the questions presented in the appeal.

After a two-day conference in Anniston an agreemen

reached resulting in adoption by the Board of a new a

“ drastically different” plan of desegregation for the 197d-74

school year.

4 LEE, ET AL. v. MACON CTY. BD. OF E

when the Board and the t ^ e d A^ t

the district court for appr h evidentiary

1973, the district court, " tion and the

hearing, on consideration i te plaintiffs, ap-

proved the plan the private plaintiffs and

by the objections filed y Appellants then

other changes made by the cour

brought this appeal.

Anniston is a city of 31,533 operatcd

are black. In the: last schoM y ^ ( M W

15 SC'blackW The new plan of desegregation approved were black, lhe t much more integration of

by the court prov, dary schools will be com-the school system. The secon » school lo r a ll

pletely integrated by piovi ^ tw0 existed before,

students, black and > tudents where there

and one junior high school ̂ former-

were twobefore. Five elementary s“ °°* ■ b ,he

ly black and tUpoosest in physical con-

Auburn Center Study the stu-

dition in the ^ " ‘̂ ^ L ^ o l s will be trans-dents white and Ma k, ^ Junior High School

ferred to the torm .. approvedT wo all-black schools — « he P ^

by the district court of Apn ^ P

School Board recognizes their omig

appellants ^ ^ ^ 2 0 , t h f I d -

copy of the j°int m° 10lhe united States which attaches a

legation is refuted by 22, 1973, showing service

s? c^ x t s s r - * u w -ciemon'

I

the racial identity of these schools

E ^ w i l H u T a refpodrTw«h the United States District

1, 1974, indicating the steps t h a t h a v e ^ i and

achieve further desegregate future.”

detailing the efforts that will be taken,m

Aonellants’ contention that they were entitled to a

further evidentiary hearing on their objections is w further eviden y^ ̂ concerning the several al

ternatives for desegregating the Annteton tehoo^have

productive of any

i r f o r " not Mrefdy fully a t h l e t e "

as the result of Ihochose not

tended by private plaintiffs^P^^ ^ nevertheless

to participate therei . , , appellants and

considered the objections raise ^ believe

made some f ̂ T c Z o n under

the court has ex t that substantial prog-the circumstances. It is apporen district court

r'ess has been made by the ration ofhas exercised close supervision over the oper^ ^ ^

the plan in the past and we P requirement

in the future, especially in light of the q ^

that the School Distri,ct^nst

court on October 15, 1975 ana students

showing the racial composition o eachi sch .

and teachers, number of transfers

- L ^ d ̂ t e — — ed, and

l e e , EX AL. v. MACON CTY. BD. OF EDUC. 5

whether the Board has sold or abandoned any school

facility or equipment.

AFFIRMED.

6 LEE, ET AL. v. MACON CTY. BD. OF EDUC.

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts—Scofields’ Quality Printers, Inc., N. O., La.

IN HIE united states district courtFOR THE KIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA EASTERN DIVISION

Anthony T. Lee, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

| United States of America,

Pla inti ff-Int erveno r and Amicus Curiae,

!National Education ;Association, Inc.,

Pla in t i f f - Int e rv en o r,

vs

| Facon County Board of Education, et al.,

Defendants.

Civil Action

No. 604-E.

Cl IT OF ANNISTON SCHOOL SYSTEM .

Proposed modifications of Board 01 Education, filed January 13, 1970, to desegregation plan filed on December 1, 1969, by Office of Education, Department of H.E.W., and amended January 10, 1970, and the objections of the plaintiffs and the National Education Association, Inc., to said plan.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * -Jf. * * * * * * ❖ * * * # * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ̂

Heard Before:

Hon. Richard T. Rives, United States Circuit Judge;Hon. H. H. Grooms, United States District Judge; and Hon. Frank K. Johnson, Jr., United States District Judge.

A t: Montgomery, Alabama, March 6 , 1970.

for 1969-70? , +- repor-t. The number of students.A Yes, sir; as oi tne la^t P

Q And the cost?

A Yes, sir. admitted as Defendant’s

m . I1ERRILL: Ue as.c that be. act.it

Ibdiibit 4. , do you have any idea

Q Doctor - or under the suffiested changes,

*at percentage of the cost of this transportation would

reduced?

A x vould estimate approximately fifty per cent. _ ,

jUDGS CHOCKS: How lone has Anniston been transport

chiMrcn to the schools. ^ a contract

v/XTI'IEfiO: About xive ycur^,

i .rc> oin'll havo this contract, with the local transit company, and *

. JUDGE CROCKS: Yon don't have year own busses.

WITHE3S: No, sir.

JUDGE GllOOiiS: hind of unusual for a city to nav.

i-■m.nsuortation to the schools.

m . imniaiA: The transportation is for students w o ^

live two miles away, and we annexed a - to the city - territory out

.beyond Fort KcClcllan running north; there is no ^L brin„ then in from that area, and Cobb - west Annas-on area

’ ' . . tvt is roro than two miles from the Annistonserved by Cobb Avenue; that as more

' 1

High School. VTEESS: About fifty per cent of the students would be

19

tv;o miles or more. I might — ray I add

Q Certainly?

A As result of the annexation, and, of course, the promise to

transport those students in, this really cot us in tho transpor

tation business; and then we had other areas that had not had

transportation prior to this, old areas that were just as far

away, so we had to extend the transportation as to all. j

JUDGE GROOMS: County was furnishing transportation

before, I presume?

WITNESS: Yes, sir; I am sure,

Q Doctor, that - so that there will bo no question about this, j

as a part of the plan which is adopted by the Anniston City Board

of Education, nay a majority of any race in any school, a moaberj

of that majority race, transfer to any other school in the system

that he wishes ̂to? j

A Yes, sir; I believe that is a provision in the II.E.U. plan which

vjg did not object to ,

Q And your faculty, there is no particular objection to that? j

j

A No, sir,

131, MERRILL: I believe that*s all the questions I

| 1

have, your honor,

JUDGE RIVES: All ri^it, gentlemen; you ray cross

examine him; the plaintiffs,

CROSS EXAMINATION:

; BY MR. SEAY:

>

■t

o

'

i

■—

s-

A

—

..

. i

to

jb

.

.l

.w

l

jt

.