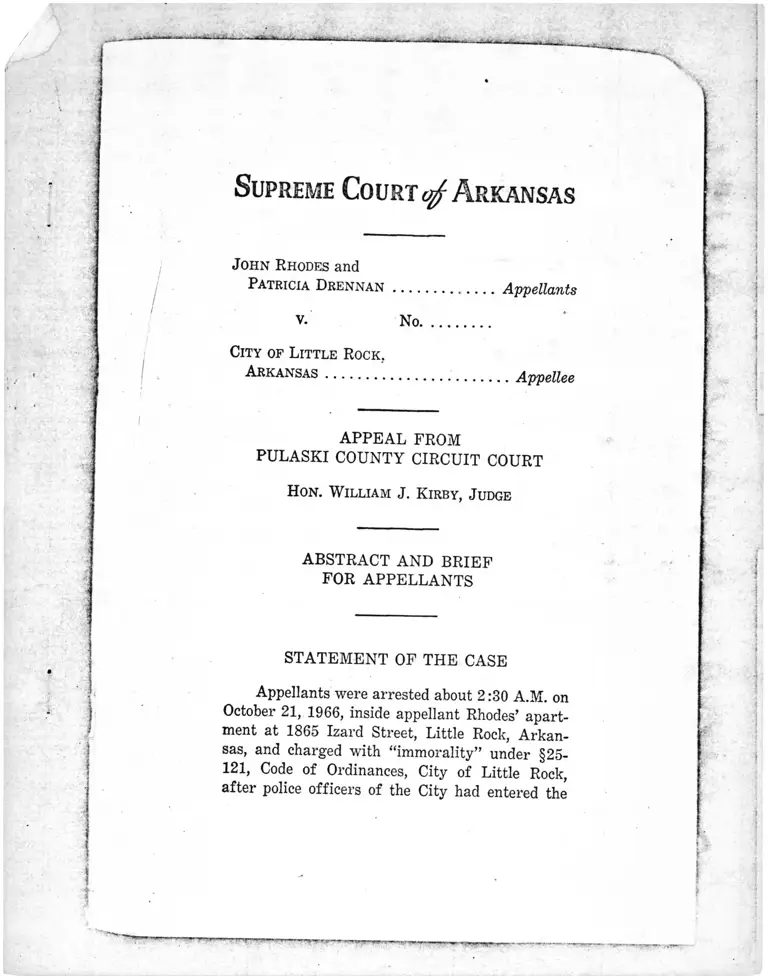

Rhodes v City of Little Rock Arkansas Abstract and Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1967

44 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rhodes v City of Little Rock Arkansas Abstract and Brief for Appellants, 1967. 18585a1f-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2598254a-314b-44c6-8794-a3722ae6b900/rhodes-v-city-of-little-rock-arkansas-abstract-and-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court ̂ A rkansas

John Rhodes and

Patricia Dr e n n a n ................ ...........Appellants

V. No...................

City of Little Rock.

A r k a n s a s .................................. ............... Appellee

APPEAL FROM

PULASKI COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT

Hon. W illiam J. K irby, Judge

ABSTRACT AND BRIEF

FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Appellants were arrested about 2 :30 A.M. on

October 21, 1966, inside appellant Rhodes’ apart

ment at I 860 Izard Street, Little Rock, Arkan

sas, and charged with “ immorality” under §25-

121, Code o f Ordinances, City of Little Rock,

after police officers of the City had entered the

apartment without a search or an arrest war

rant.

A fter pleading not guilty to the charges

against them, appellants were tried on that same

day, before Hon. John L. Sullivan, Judge of the

Municipal Court of Little Rock, found guilty, and

sentenced to thirty days’ imprisonment and a fine

of $200 plus $3 costs. On appeal to the Circuit

Court of Pulaski County, motions to quash and to

dismiss, and to declare said ordinance unconstitu

tional, were overruled. Appellants were tried

before Hon. William J. Kirby and a jury on Jan

uary 31, 1967, were found guilty, and each was

sentenced to thirty days’ imprisonment and a fine

of $100 plus $24.65 costs. Motion for New Trial

was overruled February 28, 1967.

— - — 6 - —

.... . - — - ----- ■>! * ----

\

POINTS RELIED UPON

I

The Ordinance Which Petitioners Were Convicted

of Violating is so Vague and Sweeping as to

Violate the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

H

Appellants’ Convictions Deny Them Due Process

of Law, Guaranteed by the F o u r t e e n t h

Amendment Because There is no Evidence in

this Record of an Essential Element of the

Offense and Because the Verdict is Against

the Weight of the Evidence.

Ill

Appellants Were Denied Their Rights Under the

Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution Because their

Arrest Was the Product of an Antecedent

Unreasonable Search and Because the Ar

resting Officers Were Improperly Permitted

to Testify as to their Visual Observations

During a S u b s e q u e n t Unconstitutional

Search.

IV

Little Rock City Code of Ordinances %25-121 is an

Ex Post Facto Law Forbidden by the Arkan

sas Constitution.

It1 Is

i

II

----

iflaafi a IMM lu x * - -

\

. 4

ABSTRACT

PLEA AND ARRAIGNMENT

(R.12)

Pulaski Circuit Court, First Division

September Term, 1966

Monday, December 12, 1966

City of Little R o c k ................................Plaintiff

V. No. 66392 Immorality

Patricia Ann D ren n an ........................Defendant

This day comes the City of Little Rock by

Perry Whitmore, Assistant City Attorney, and

comes the defendant in proper person and by her

attorney, John Walker, and defendant is called

to the bar of the Court and informed of the nature

of the charge filed herein, enters her plea of not

guilty thereto, and by agreement the case is

passed to January 31, 1967, for a jury trial.

--------- r ------------ -

I

PLEA AND ARRAIGNMENT

(R.13)

Pulaski Circuit Court, First Division

September Term, 1966

Wednesday, December 14, 1966

City of Little R o c k ...................................Plaintiff

v. No. 66393 Immorality

John L. Rhodes ..................................... Defendant

This day comes the City o f Little Rock by

Perry Whitmore, Assistant City Attorney, and

comes the defendant in proper person and by his

attorney, John Walker, and defendant is called

to the bar of the Court and informed of the na

ture of the charge filed herein, enters his plea of

not guilty thereto, and by agreement the case is

passed to January 31, 1967, for a jury trial.

MOTION TO DISMISS

. (R.14-15)

Defendants, by their attorney, John Walker,

hereby move that the charges against them be

dismissed, and as grounds therefor, state the fol

lowing :

1. The alleged arrest of the defendants was [

invalid because (1 ) no warrant of arrest was is-

6

sued nor delivered to any peace officer prior to

the alleged arrest; (2 ) the defendants commit

ted no public offense in the presence of any peace

officer; and (3 ) no peace officer had any reason

able ground to believe that either defendant or

both of them had committed a felony; and there

fore, the alleged arrest of defendants was in vio

lation of Ark. Stat. Anno. Sec. 43-403 (Repl.

1964).

2. The alleged arrest of the defendants took

place within the apartment of defendant John

Rhodes, while the charges against the defendants

are brought under Little Rock Ordinance No. 25-

121, concerning “ immorality” in a public place.

Defendants may not now be tried for a violation

o f another ordinance. Cole v. Arkansas, 333

U.S. 196 (1948).

3. All evidence gained from the illegal

entry by peace officers into defendant Rhodes’

apartment, including visual observations of the

police officers, Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S.

10 (1948), cannot be admitted into evidence.

U.S. Constitution Amend. 4, 14; Mapp v. Ohio,

367 U.S. 643 (1961).

Wherefore, defendants respectfully pray this

Honorable Court to dismiss the charges against

them and quash the information herein.

Respectfully submitted,

/ s / John W. Walker

h

Filed: Jan. 31, 1967

MOTION TO QUASH INFORMATION AND TO DECLARE

MUNICIPAL ORDINANCE UNCONSTITUTIONAL

(R.16)

Defendants by their attorney, John W.

Walker, hereby move the Court to Quash the In

formation herein and to declare the Municipal

Ordinance of the City of Little Rock, Arkansas

under which they were arrested, Sec. 25-121, to

be unconstitutional on the ground that said ordin

ance is too broad, too vague and too indefinite to

be objectively applied in that it fails to specify

and otherwise give notice to defendants of the

conduct or acts proscribed.

Wherefore, defendants respectfully pray this

Honorable Court to Quash the Information here

in and to Declare the Ordinance under which

they were arrested to be unconstitutional.

Respectfully submitted,

/ s / John W. Walker

Filed: Jan. 31, 1967

1—̂

s

ABSTRACT OF TESTIMONY

(Given at trial in the Pulaski County Circuit

Court, January 31, 1967 (R .45-83).)

Officer John Terry (R .45 -63 ):

I am a detective sergeant, Special Detail,

Little Rock Police Department (R .45). On

October 21, 1966, after having previously re

ceived complaints, I went to 1865 Izard Street

about 2:30 a.m. There are two separate build

ings there— a house with an apartment in the

rear (R .46). I knocked on the door of the ga

rage apartment but received no answer. I could

see someone looking at me through the Venetian

blinds. I went to the window and shined my

flashlight through the blinds; I could see a white

. female and a colored male in bed. I identified

myself as “ Sergeant Terry with the Police De

partment” and told them to open the door. After

a minute or two I told the colored male he was

under arrest and again told him to open the door.

A minute or two after that I pushed open the

door and went inside. He was out of bed (R.

47). I lifted the covers of the bed and saw that

Pat Drennan had on a brassiere and pants. I

gave her the rest of her clothes and she dressed.

I asked if they were married. Rhodes said he

was married to a Ruby Rhodes, 1800 Thayer

Street (R .48). Drennan said she was married

9

to Frank Drennan. Neither commented on the

other’s answer (R .49). I had been assigned to

this case for a week or so. I could have obtained

an arrest warrant— I had plenty o f time— but I

did not have one (R .50). I had no reason to

believe that Rhodes and Drennan were commit

ting a felony, or anything but immorality. A

neighbor, Charles Bussey, made an oral complaint

to me at his residence (R .51). I don’t know

whether his complaint to the Chief of Police was

in writing or not. I saw them together in bed

and assumed they were nude (R .52). I shined

my flashlight through the Venetian blinds, which

were not totally closed; I could get a clear view of

the bedroom (R .53). At that time I had not

told anybody that they were under arrest (R .54).

When I saw someone looking at me through the

blinds, I did not know who it was (R .56). When

the door was not opened, I pushed it open; it was

locked (R .57). I had to use force to open the

door (R .58). My understanding is that any

time any offense is committed in my presence, I

have the right to make an arrest (R .60). They

were not armed (R .61). I did not notice that

either one had been drinking; they did not use

obscene language in my presence. This was not

what I would call a public place. I had known

Drennan for several years (R .62).

10

Officer W illiam D. Gibson (T .63-73):

I am a detective with the Vice Squad. I was

with Officer Terry on the night in question. We

had received complaints about ‘ an incident oc

curring at this address” . We knocked on the

door, saw a blind being opened, and shined a

flashlight in the window. We observed two

people in bed together in a state o f undress, and

asked them to open the door (R .64). Sergeant

Terry pushed the door open. Rhodes and Dren-

nan were inside. Sergeant Terry told them they

were under arrest and we took them to the Police

Department (R .65). The building was a resi

dence, located in a residential area (R .67). I

had not seen the defendants talking together

earlier that day;-1 had never seen them before.

I had never seen Rhodes invite Drennan to his

apartment (R .69). I had never seen either

person attempt to entice the other to the apart

ment. I did not see them enter the apartment

together (R .70). At the police station we told

them what they were charged with but we did

not advise them of their right to counsel or to re

main silent. We took no statement from them

(R .71). We had to use force to get in the apart

ment; the door was locked. We had no search

warrant or arrest warrant (R .72).

THE CITY’S REQUESTED INSTRUCTION NO. 1

(R.75-76)

It is hereby declared to be a misdemeanor for

any person to participate in any public place in

any obscene or lascivious conduct, or to engage

in any conduct calculated or inclined to promote

or encourage immorality, or to invite or entice any

person or persons upon any street, alley, road or

public place, park or square in Little Rock, to

accompany, go with or follow him or her to any

place for immoral purposes, and it shall be un

lawful for any person to invite, entice, or address

any person from any door, window, porch or

portico of any house or building, 'to enter any

house or go with, accompany or follow him or her

to any place whatever for immoral purposes.

The term “ public place” is defined to mean

any place in which the public as a class is invited,

allowed or permitted to enter, and includes the

public streets, alleys, sidewalks and thorough

fares, as well as theaters, restaurants, hotels, as

well as other places. The term “ public place”

is to be interpreted liberally.

Any person found guilty of violating the pro

visions of this section shall, upon conviction, be

fined in any sum not less than ten dollars, nor

more than two hundred and fifty dollars, or im-

12

prisoned for not less than five days nor more

than thirty days, or both fined and imprisoned.

The Court gave the City’s Requested Instruc

tion No. 1.

The defendant objected to the action of the

Court in giving the City’s Requested Instruction

No. 1, and at the time asked that their excep

tions be noted of record, which was accordingly

done.

THE DEFENDANTS’ REQUESTED INSTRUCTION

NO. 1

(R.80)

You are instructed that an element of the

offense of immorality, as used in Section 25-121

of the Code of Ordinances of the City of Little

Rock, is that the offense of immorality be per

formed in a public place, as defined in the said

ordinance.

The Court refused to give the Defendants’

Requested Instruction No. 1.

CHARGE TO JURY

(R.81-83)

THE COURT*.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I am going to give you

the law in this case. It is not particularly com-

j|^K n r J— 1 •

V

13

plicated and the instructions are not long. It

is my duty to give you the law and it is your duty

to apply that law to the facts as you find them

from the evidence that is developed here from the

witness stand and bring me in a verdict m ac

cordance with both the law and the evidence.

(A t this time, the Court read to the

jury the Instructions indicated as given,

above, after which the closing arguments

were made to the jury on behalf of the City

and the defendants, after which the fol

lowing proceedings occurred.)

THE court:

Ladies and Gentlemen, I will now give you

the forms of your verdict. I f you feel like John

Rhodes is guilty of immorality, you will say:

“ We, the jury, find the defendant guilty of im

morality, as charged in the information, and fix

punishment at a fine of . . . . . . . dollars, or . . .

days imprisonment, or a fine o f ............. 0 ars

and . . . . days imprisonment.” That is any

thing not less than ten dollars nor more than two

hundred fifty dollars, or imprisonment not less

than five nor more than thirty days, or both sue

fine and imprisonment.

If you feel like he is not guilty, or you have

a reasonable doubt of his guilt on the whole case,

l i

-m .------------ ’

you will say : “ We, the jury, find the defendant

not guilty.”

Likewise, in the case o f Patricia Drennan,

if you believe she is guilty of immorality, you

will say: “ We, the jury, find the defendant

guilty o f immorality, as charged in the informa

tion, and fix her punishment at a fine o f .............

dollars o r .........days imprisonment, or a fine of

............. dollars a n d ........... days imprisonment.”

That is not less than ten or more than two hun

dred fifty dollars, and not less than five nor more

than thirty days, or both a fine and imprison

ment.

I f you feel like she is not guilty, or have a

reasonable doubt of her guilt on the whole case,

you will say: “ We, the jury, find the defendant

not guilty.”

These verdicts must be signed by one of you

ladies or gentlemen as foreman and must be unan

imous. You may retire and consider your ver

dict.

14

■ |ir; . -- ------■«*■.■■■■».». d ft . . . . . . ..M

15

TRIAL VERDICT AND JUDGMENT

(R.17-18)

Pulaski Circuit Court, First Division, September

Term, 1966

Tuesday, January 31, 1967

City of Little Rock Plaintiff,

No. 66392 & 63393 Immorality

Patricia Ann Drennan and

John L. Rhodes, Defendants

This day comes the City of Little Rock by

Perry Whitmore, Assistant City Attorney, and

come the defendants in proper persons and by

their attorney, John Walker, and by agreement

the cases are consolidated for trial, and defend

ants’ Motion to Dismiss is filed, heard and over

ruled, the defendants’ Motion to Quash is filed,

heard and overruled, and defendants exceptions

are saved, and both defendants having previously

entered a plea of not guilty, parties announce

ready for trial, thereupon comes twelve qualified

electors of Pulaski County, viz: E. B. Hearn,

Rev. Curtis Rideout, J. E. Cochran, Soloman

Johnson, Mrs. R. E. Bibby, A. T. Miller, Mrs.

Gladys Buckles, B. D. Henry, L. V. Bettis, Charles

Wade, Mrs. Haco Boyd and Alfred Treadway,

who are emapneled and sworn as a trial jury in

N

16

these cases, and after hearing the testimony of

the witnesses, the instructions of the Court and

the arguments of counsel, the jury doth retire to

consider arriving at a verdict for each defendant,

and after deliberating thereon, the jury doth re

turn into open court with the following verdicts:

“ We, the jury, find the defendant, Patricia Ann

Drennan, guilty of Immorality, as charged, and

fix her punishment at a fine of $100.00 and 30

days imprisonment. Mrs. Gladys Buckles,

Foreman.” “ We, the Jury find the defendant,

John L. Rhodes, quilty of Immorality, as charged,

and fix his punishment at a fine of $100.00 and

30 days imprisonment. Mrs. Gladys Buckles,

Foreman.” Whereupon, the Court doth dis

charge the jury from these cases, and each de

fendant is given fifteen days in which to file a

Motion for New Trial and committed to jail in

lieu o f $1,000.00 bond.

MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL

(R.31-34)

Comes the defendants, John Rhodes, a Negro

male, and Patricia Drennan, a white female, and

hereby move the court to set aside the verdicts

of the jury herein and to grant them a new trial

of this cause, and in support of same state as

follows:

1. That Little Rock Municipal Ordinance

Sec. 25-121, under which defendants were ar

rested, tried and convicted, violates the due pro

cess clause to the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution in that said ordinance

is too broad, too vague, and too indefinite or un

certain to give defendants notice of the acts

and/or conduct prescribed thereunder.

2. That the arrest of the defendants by the

police was invalid because it was made without

warrant and without “ probable cause” ; and be

cause the sole basis of the arrest was the race of

the parties involved, and thus in violation of the

equal protection and due process clauses of the

Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution.

3. That the entry,' and manner of same,

into defendant Rhodes’ apartment by the arrest

ing officers and the search and seizure therein,

without a warrant, was illegal and thus in vio

lation of the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments

to the United States Constitution.

4. That the visual observations of the ar

resting officers were improperly admitted into

evidence in violation of the Fourth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution.

5. That defendants were not advised of .

their rights to counsel, nor afforded the oppor

tunity to retain counsel at their trial in the Mu-

17

\

18

nicipal Court of Little Rock, Arkansas; and were

thus deprived of rights secured to them by the

Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution.

6. That defendants were prosecuted on the

basis of a “ personal arrest’’ and thereby de

prived of due process of law under the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution.

7. That the defendants were not properly

apprised of the charges against them because

there was no indictment, information, or warrant

filed against them in violation of their rights as

secured by the due process clauses of the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution.

8. That there was no evidence to support

defendants’ convictions in violation of the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

9. That the prosecutions under said mu

nicipal ordinance infringed upon and violated de

fendants’ rights of privacy and association guar

anteed to them by the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution.

10. That the verdicts of the jury are con

trary to law.

------- ' '

X

11. That the verdicts of the jury are con

trary to the evidence.

12. That the verdicts of the jury are against

the weight of evidence.

13. That it was error for the trial court

to deny defendants’ motion to declare the Little

Rock Municipal Ordinance Sec. 25-121 unconsti

tutional.

14. That it was error for the court to re

fuse defendants’ requested instruction No. 1,

which reads: “ You are instructed that an

element of the offense of immorality, as used in

Section 25-121 of the Code of Ordinances of the

City of Little Rock, is that the offense of im

morality be performed in a public place, as de

fined in the said ordinance.”

15. That it was error for the trial court to

refuse defendants’ requested instruction No.

2, which reads: “ You are instructed that the

word ‘immorality,’ as used in Section 25-121 of

the Code of Ordinances of the City of Little Rock,

Arkansas, does not include an act of sexual inter

course not sanctioned by marriage vows.”

Wherefore, defendants respectfully pray that

the court set the verdict of the jury herein aside

19

and that they be granted a new trial in this

cause.

Respectfully submitted,

s / John W. Walker

Jack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

Attorneys for Defendants

ORDER ON MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL

(R.35)

In the Circuit Court of

Pulaski County, Arkansas

Third Division

September Term, 1966 No. 66392 and 66393

City of Little Rock, Arkansas

V.

John Rhodes and Patricia Drennan

ORDER

Came on defendants’ Motion for a New Trial

for a hearing before this Court at 10:00 a.m.,

February 28, 1967, defendants being represented

by their attorney, Mr. John W. Walker, and the

plaintiff being represented by Mr. Perry V. Whit-

20

i . i . ... . . ------- ■ '•> '.—a t .

21

more, and after a hearing on said Motion, the

Court doth Find, Order, Adjudge, and Decree.

That defendants’ Motion for a New Trial is

denied.

/ s / Wm. J. Kirby

Circuit Judge

Dated: February 28, 1967

MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL OVERRULED

(R.36)

Pulaski Circuit Court, First Division

September Term, 1966

Tuesday, February 28, 1967

City- of Little Rock, A rkan sas............... Plaintiff

V. Nos. 66392 and 66393

Patricia Ann Drennan and

John L. Rhodes

This day comes the City of Little Rock by

Perry Whitmore Assistant City Attorney, and

come the defendants in proper persons and by

their attorney, John Walker, and defendants’ Mo

tion for New Trial is heard and overruled, and

defendants exceptions are saved and an appeal is

prayed and granted and the defendants are given

forty-five days in which to get up and file their

Bill of Exceptions.

T '#«<■ t. w « r .r r -

--- -------------------- ... ■ i . * . a . « ift» W ir ____

22

ARGUMENT

I

The Ordinance Which Petitioners Were Convicted

of Violating is so Vague and Sweeping as to

Violate the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

Petitioners were convicted of violating §25-

121 of the Code of Ordinances, City of Little Rock,

which provides as follows:

“ It is hereby declared to he a misde

meanor for any person to participate in any

public place in any obscene or lascivious

conduct, or to engage in any conduct cal

culated or inclined to promote or encourage

immorality, or to invite or entice any per

son or persons upon any street, alley, road

or public place, park or square in Little

Rock, to accompany, go with or follow him

or her to any place for immoral purposes,

and it shall be unlawful for any person to

invite, entice, or address any person from

any door, window, porch or portico of any

house or building, to enter any house or go

with, accompany or follow him or her to

any place whatever for. immoral purposes.

------ ------------ ....... ' ------------ i l l f i . i r l l . i m V -------1 ,

23

The term ‘public place is defined to

mean any place in which the public as a

class is invited, allowed or permitted to

enter, and includes the public streets, al

leys, sidewalks and thoroughfares, as well

as theaters, restaurants, hotels, as well as

other places. The term ‘public place’ is

to be interpreted liberally.

Any person found guilty o f violating

the provisions of this section shall, upon

conviction, be fined in any sum not less

than ten dollars, nor more than two hun

dred and fifty dollars, or imprisoned for

not less than five days nor more than

thirty days, or both fined and imprisoned.”

On its face, this section attempts to make

criminal four separate kinds of conduct:

(1 ) obscene or lascivious conduct in a pub

lic place;

(2 ) conduct in a public place calculated or

inclined to promote or encourage immorality;

(3 ) enticing or inviting, in a public place,

any person to follow or accompany one to any

place for immoral purposes;

(JKiuie SmiSBfb* J»T«.. M’M-l ■ 11 iMMUjlff

f r o r

!

f

j-

24

(4 ) inviting or enticing from a house, win

dow or porch, etc., to enter or accompany one to

any place for immoral purposes.

i Althoueh the ordinance seems to include within its pro-

“p0HhC:t’ No indictment was ever returned against appel-

= f r « S 3« 3 ^ p

Wp „ rp unable to agree with this disposition of the case.

The ̂ verdict “ against the appellant was a general one-JEt

?pect ^ lpanL say under whkh dause of the statute the impossible to say unoei these clauses, which

s s l i s s s ^ i

not convicted under that clause . ith the state court,

f h i f t h f verdict S be sustained if any one of the clauses

S lhe statute were found to be valid, the necessary con

clusion from the manner * * £ * < * « £ *

cannot be upheld

A statute which upon

lively construed, is 30 v^ e f t£is opportunity is repugnant

punishment of the fair use oi l w the 14th Amendment.

discloses may"have'rested upon ’that clause exclusively, must

be set aside.

_ of ctate 378 U.S. 500, 515-16 (1964).Cf. Aptheker v. Secretary of State,

■

I

25

The ordinance is phrased in broad terms not

defined therein, nor in any related sections of the

City Code. While the core of the law is “ im

morality,” a word of considerable breath whose

meaning is open to considerable disparity of views

(Cf. Ex parte Jackson, 45 Ark. 158, 164 (1885),

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 312,

313 (1966), no specific substantive content is

given the word in the ordinance or in any other

sections of the City Code.

The language of the ordinance which speci

fies what kinds of conduct are so related to “ im

morality” as to be made criminal by this law is

similarly broad and without explanation or modi

fication : e.g., “ calculated or inclined to promote

or encourage.” This ordinance presents those

who would attempt to conduct themselves within

the permissible confines of the law with a dilem

ma, because they are unable to choose a course of

action with any fair assurance that they are not

violating the ordinance.

The very application of this ordinance, de

signed to punish solicitation and prostitution (see

II infra), to the facts of this case affords the

clearest demonstration of its overbreadth. The

ordinance concerns public conduct; yet appellants

were convicted and sentenced to imprisonment on

the basis of conduct which even the arresting of-

-a—

■ . - ... - .......„ ----- -.r-.

26

ficer did not believe occurred in a public place (R.

62 ).2 Since the trial court upheld the constitu

tionality of the ordinance by overruling the Mo

tion to Quash (R.42) and the Motion for New

Trial (R .36), the convictions must be reversed.

This is a law which, because it “ forbids . . .

the doing of an act in terms so vague that men

of common intelligence must necessarily guess

at its meaning and differ as to its application,

violates the first essential of due process.”

Connally V. General Const. Co., 269 U.S. 385,

391 (1926). “ . . . No one may be required at

peril o f life, liberty or property to speculate as

to the meaning of penal statutes. All are en

titled to be informed as to what the state com

mands or forbids . . . ” Lanzetta v. New Jersey,

306 U.S. 451, 453 (1938); see also Winters v.

New York, 333 U.S. 507, 515 (1948); Gamer

v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157, 185, 207 (1961)

(concurring opinion). Where a law incorpo

rates only the general substantive standard of

morality or immorality, it necessarily affords

but minimal notice of its proscriptions. Musser

V. Utah, 333 U. S. 95, 96-97 (1948).

^Although the ordinance contains a purported definition of

“public place,” that “definition” merely creates an explicit re

quirement of broad construction, in derogation of the usual

rule that penal laws are to be strictly construed, and demon

strates that the ordinance was purposefully drafted as loosly

as possible.

27

But this ordinance is not defective solely be

cause it defines criminal conduct with insuffic

ient clarity so that its scope may be misunder

stood by those anxious to avoid its sanctions. The

unpredictability of its application infects the

judicial process as well. “ [SJince the broadness

o f the law creates an unclear, variable standard

o f guilt for the fact-finder, . . . the possibilities

o f an evenhanded application of law and of ef

fective judicial review are substantially de

creased/’ Lewis, The Sit-In Cases: Great Ex

pectations, [1963] Supreme Court Review 101,

110. In effect, this ordinance ‘ ‘licenses the jury

to create its own standard in each case,” Herndon

V. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242, 263 (1937); Musser v.

Utah, supra; see Ex parte Jackson, supra, 45

Ark. at 164.

The Supreme Court of the United States has

recently passed upon a state statute which pro

vided the jury with no standards in the imposi

tion o f sanctions save its own discretion. A

Pennsylvania statute3 allowed juries to assess

court costs against acquitted misdemeanor de

fendants. The Court held the statute to be un

constitutional, because it

contains no standards at all. nor does

it place any conditions of any kind upon

3Pa. Stat. Ann., Tit. 19 Sec. 1222.

28

the jury ’s power to impose costs. . . . Cer

tainly one of the basic purposes of the Due

Process Clause has always been to protect

a person against having the Government

impose burdens upon him except in ac

cordance with the valid laws of the land.

. . . It would be difficult, if not im

possible for a person to prepare a defense

against such general abstract charges as

“ misconduct,” or “ reprehensible conduct.”

I f used in a statute which imposed for

feitures, punishments, or judgments for

costs, such loose and unlimiting terms

would certainly cause the statute to fail

to measure up to the requirements of the

Due Process Clause. (emphasis in orig

inal) Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S.

399, 403, 404 (1966).

The teaching of Giaccio is that penal laws

may not, consistent with the Due Process clause,

- remit to the unbridled discretion of court or jury

the decision to impose sanctions, much less the

determination of criminality. §25-121 of the

_ . Little Rock Code of Ordinances does just that.

These objections are the more forceful be

cause this ordinance sweeps within its broad pro

hibition freedom of association which is protected

against infringement by the State. See Note,

___ The Void-for-Vagueness Doctrine in the Supreme

: Court, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960). The or

dinance is directed not at overt acts harmful in

themselves, but at incidents of a relationship be-

29

tween persons which becomes illegal only by the

application of a totally subjective standard. For

example, the line between what is protected as

sociation and what is invitation or enticement to

immorality depends upon the subjective compre

hension of a police officer about the ultimate in

tent of the parties in speaking to one another.

/ In this manner, the definition of the actions which

may be punished is effectively relegated to the

police, and ultimately to the courts, for ad hoc

determination after the fact in every case. A

law with such a potential for selective enforce

ment, NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 435

(1963), inevitably creates a “ chilling effect upon

the exercise of First Amendment rights,” Dom-

browski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 487 (1965), of

speech and association. The circumstances of

this case illustrate graphically the extent to

which personal privacy, Griswold v. Connecticut,

381 U.S. 479 (1965), may be invaded under this

law. For these reasons, the principle that penal

;laws may not be vague must, if anything, be

enforced even more stringently.

II

Appellants’ Convictions Deny Them Due Process

of Law, Guaranteed by the F o u r t e e n t h

Amendment Because There is no Evidence in

this Record of an Essential Element of the

Offense and Because the Verdict is Against

the Weight of the Evidence.

§25-121, Code of Ordinances of the City of

Little Rock, was plainly designed to punish solici

tation and prositution. One of its essential ele

ments is that some act— obscene or lascivious con

duct, enticement or solicitation, etc. occur on a

public street or in a public place.4 Any other con

struction of the ordinance would raise grave ques

tions of infringement of constitutionally protected

rights of association and privacy recognized in

Griswold V. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965).

See Roberts V. Clement, 252 F. Supp. 835, 848

(E D. Tenn. 1966) (concurring opinion) (anti-

nudism statute).

Yet there is no evidence on this record that

either or both of the appellants performed any

proscribed act in a public place. To the con

trary, the arresting officers testified that they

-did not arrest appellants in a public place (R.62,

67) and that they had not seen the appellants

talk to one another or invite or entice one another

to the apartment (R.69-70). The conduct de

scribed by the officers took place entirely within

a private residence, not bordering a public street,

behind a locked door, at 2:30 A.M.

— TiTThis regard,

Requested Instruction No. 1 (R.80).

*̂**̂

*—

***■

iLi

diV

i M

* ■■n

iim

. —

-

- -|

m

i l

'iI'h

n

n n

rr“

lt?

na

>

■W

M

m

tt

m

,k

t

■

. J l * « * l . i .1

31

“ Under the words of the ordinance itself,

i f the evidence fails to prove all . . . elements of

this [immorality] charge, the conviction is not

supported by the evidence, in which event it does

not comport with due process of law.” Thomp

son w. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199, 204 (1960)

(emphasis supplied).

The convictions must be reversed for failure

to prove a public act, Shuttlesworth v. Birming

ham, 382 U.S. 87 (1965); Barr v. City of

Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 (1964); Fields v. Fair-

field, 375 U.S. 248 (1963); Taylor v. Louisiana,

370 U.S. 154 (1962 ); Garner V. Louisiana, 368

U.S. 157 (1961); Thompson v. City of Louisville,

supra, and because the verdicts were against the

weight of the evidence Ark. Stat. Ann. §§43-2203,

2725 (Repl. 1964).

in

Appellants Were Denied Their Rights Under the

Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution Because their

Arrest Was the Product of an Antecedent

Unreasonable Search and Because the Ar

resting Officers Were Improperly Permitted

to Testify as to their Visual Observations

During a S u b s e q u e n t Unconstitutional

Search.

The shocking police misconduct shows on the

face o f this record requires a reversal of appel-

ji

I

!i

*

!

'i

I

1

:

i

<

i

- —

-

'•

-i

'--

---

---

---

.

,•„

, |,„,„

,

„

m i M in _ m , i. ■ a n ___ - - - - -

n ! Jr

-'/ T

y o

. i

) \ | 1! I

t 1j i. i

32

lants’ convictions. Rochin V. California, 342

U.S. 165 (1952). An unreasonable, unwar

ranted and unconstitutional invasion of privacy

and property cannot legitimize a subsequent un

lawful arrest; nor may that arrest in turn justify

a later search, without overstepping the bounds

of due process. See Johnson v. United Spates,

333 U.S. 10 (1948).

The arresting officers testified that they

were investigating a complaint previously re

ceived (R.46, 5 1 ); yet they chose to make their

investigation at a patently unreasonable houi

2:30 a.m. (R .46). They had plenty of time to

obtain a warrant (R .5 0 ); yet they failed to do

so but entered appellant Rhodes’ apartment un

lawfully, having neither a search nor an arrest

warrant (R .72). This fact alone is sufficient

to invalidate the searches o f appellant Rhodes’

home and to require a reversal here. See Agnel-

lo V. United States, 269 U.S. 20, 33 (1925). The

officers did not make their investigation on the

public streets or on public property. Appellant’s

o-arage apartment was at the rear of a house in

a residential area (R .4 6 ); thus, in walking to the

door of the apartment (R.47) the officers weie

already trespassing. “ Whatever quibbles there

may be as to where the curtilage begins and ends,

clear it is that standing on a man’s premises and

looking in his bedroom window is a violation of

*

t

ff

t

J ........ urMt i m n ifMi r r in t i » ' i i ^ f a . l , i . H M . ' i ,

33

his ‘right to be let alone’ as guaranteed by the

Fourth Amendment.” Brock V. United States,

223 F. 2d 681, 685 (5th Cir. 1955). It is clear

that the ground surrounding Rhodes’ apartment

was protected against police intrusions The

following definition of curtilage appears in

corpus juris:

In its most comprehensive and proper

legal signification it includes all that

space of ground and buildings thereon

which is usually enclosed within the gen

eral fence, immediately surrounding a

principal messuage, outbuildings, and

yard closely adjoining to a dwelling house.

(25 C.J.S. 82).

The principle has also received widespread

judicial recognition. E.g., Rosencranz v. United

States, 356 F. 2d 310, 313 (1st Cir. 1966)

(b a rn ); Kroska v. United States, 51 F. 2d 330

(8th Cir. 1931) (farm yard ); Whitley V. United

States, 237 F. 2d 787 (D.C. Cir. 1956) (porch).

The circumstances of Brock, supra, are simi

lar to the instant case. There, officers observed

a still located a quarter of a mile from the house

in question. An agent knocked at the door of

the house, received no answer, and then looked in

a bedroom window where he saw the defendant.

The agent awakened the defendant and ques

tioned him through the window while defendant

was still somnolent. The United States Court

34

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held it error to

admit the statements made by the defendant be

cause “ the agents, when they appeared outside

Brock’s bedroom window, were in violation of his

rights under the Fourth Amendment.” (223 F.

2d at 685.)

Equally relevant is the opinion of the United

States Supreme Court in Taylor v. United States,

286 U.S. 1 (1932):

During the night, November 19th,

1930, a squad (six or more) of prohibition

agents while returning to Baltimore City

discussed premises 5100 Curtis Avenue, of

which there had been complaints over a

period of about a year.” Having decided

to investigate they went at once to the ga

rage at that address, arriving there about

2:io a.m. The garage— a small metal

building— is on the corner of a city lot and

adjacent to the dwelling m which petition

er Taylor resided. The two houses are

parts of the same premises.

As the agents approached the garage

they got the odor of whiskey coming from

within. Aided by a searchlight they

looked through a small opening and saw

many cardboard cases which they thought

probably contained jars of liquor. There

upon they broke the fastening upon a door,

entered and found one hundred twnety-two

cases of whiskey. . . .

Although over a considerable period

numerous complaints concerning the use of

35

these premises had been received, the agents

had made no effort to obtain a warrant for

making a search. They had abundant op

portunity so to do and to proceed in an

orderly way even after the odor had em

phasized their suspicions; there was no

probability of material change in the sit

uation during the time necessary to secure

such warrant. Moreover, a short period

of watching would have prevented any

such possibility.

We think, in any view, the action of the

agents was inexcusable and the seizure un

reasonable. The evidence was obtained

unlaivfully and should have been suppressed.

(286 U.S. at 5-6) (italics supplied).

Evidence, including visual observations, ob

tained as a result of such a trespass, should have

been excluded. Silverman v. United States, 365

U.S. 505 (1961); Silverthome Lumber Co. v.

United States, 251 U.S. 385 (1920); McGinnis v.

United States, 227 F. 2d 598 (1st Cir. 1955);

Williams v. United States, 263 F. 2d 487 (D.C.

Cir. 1959).

Thus, the officers should not have been per

mitted to testify concerning their observations

in the window of Rhodes’ apartment. Those ob

servations likewise cannot support the arrest o f

appellants for the arrest may not be validated

by either the antecedent unconstitutional search

from the window, Taylor V. United States, 286

U.S. 1 (1932), or the subsequent forceful entry

36

and search of the apartment. Johnson V. United

States, 333 U.S. 10 (1948); cf. Chapman v.

United States, 365 U.S. 610 (1961). Further,

the conduct of the officers in this case does not

fall within their statutory authority to arrest

without a warrant. Ark. Stat. Ann §43-403

(Repl. 1964).

Since the arrest does not meet constitutional

or statutory standards, there was no justification

for breaking down the door to the apartment and

searching the premises. It was error to allow

the officers to testify concerning their visual ob

servations inside the apartment, Silverthorne

Lumber Co. V. United States, supra; Johnson v.

United States, supra. Appelants’ constitutional

rights can be vindicated only by a new trial free

of the taint of such unconstitutionally obtained

evidence. Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961 );

Kerr v. California, 374 U.S. 23 (1963).

rv

Little Rock City Code of Ordinances §25-121 is an

Ex Post Facto Laiv Forbidden by the Arkan-

\

sas Constitution.

The principle laid down by this Court in Ex

parte Jackson, 45 Ark. 158 (1885) controls this

case and requires that appellants’ convictions be

reversed and the prosecutions dismissed.

II

X

....

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

.m

m

m

\*

««

un

ns

"."

"

....

...

...

..m

um

/ - j ii i r f i i Ta f * i i i v ^ m .i. mil . .— _______ if * ■ « J ,.—■ ̂_ ___

37

§25-121 of the Code of Ordinances, City of

Little Rock, declares it to be a misdemeanor to

“ engage in any conduct calculated or inclined to

promote or encourage immorality,” and to per

form certain acts “ for immoral purposes.” How

ever, the ordinance nowhere suggests any ob

jective standard for interpreting the terms “ im

moral” and “ immorality.” Nor did the trial

court’s instructions give the jury any guide to be

applied in determining the meaning of the words.

Thus the jury was unaware of the proper stand

ards it should employ in deciding whether any

crime had in fact been committed.

The ultimate question of appellants’ guilt

or innocence was left to be decided according to

“ the moral idiosyncrasies of the individuals who

compose [d] the court and jury,” Ex parte Jack-

son, 45 Ark. at 164. Jackson was a prosecution

for the crime of committing an act injurious to

public morals. The statute was struck down

by this Court because it was ex post facto:

We cannot conceive how a crime can,

on any sound principle, be defined in so

vague a fashion. Criminality depends,

under it, upon the moral idiosyncrasies of

the individuals who compose the court and

jury. The standard of crime would be

ever varying, and the courts would con

stantly be appealed to as the instruments

of moral reform, changing with all fluctu

ations o f moral sentiment. The law is

i . n > - y i - j t i i n n n i ■ n t f - f i * > '« i i f . - n ■ — n M r i ' . i ■ d r a - a t M n i n . - f t t i t o - A i • i ^ ■ a l t l i

38

simply null. The constitution, which for

bids ex post factor laws, could not tolerate

a law which would make an act a crime,

or not, according to the moral sentiment

which might happen to prevail with the

judge and jury after the act had been com

mitted.

Ark. Const. (1874), Art. 2 §17 provides that

“ No bill of attainder, ex post facto law or law

impairing the obligation of contracts shall ever

be passed . . . . ” Appellants submit that §25-

121 of the Little Rock Code of Ordinances is in

distinguishable from the law struck down in

Jackson.' Indeed, the vices of this ordinance are

greater, since the acts here need not be injuiious

to public morals” but merely “promote or en

courage immorality.” This ordinance is clearly

beyond the power of the Legislature, or the gov

erning body of any municipality, if the worthy

principle enunciated by this Court in Ex parte

Jackson, supra, is respected. Since the trial

court took a different view in refusing to quash

and declare the ordinance unconstitutional (R.

16) the judgments of conviction should be re

versed with instructions to dismiss the prosecu

tions.

" scf Musser v. Utah, 333 U.S. 95 (1948), on remand, State

Musser U8 Utah 537, 223 P. 2d 193 (1950).

.«,. ----- "** — ,V _. --- ,

39

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for all the foregoing reasons, ap

pellants respectfully submit that the judgments

o f the trial court should be reversed and dis

missed.

Respectfully submitted,

John W. W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

... --- - • ( ! « p -----fa -

Supreme Court ̂ A rkansas

John Rhodes and

Patricia Dr e n n a n ........................... Appellants

v. No.................

City of Little Rock,

A r k a n s a s ........................................... .. Appellee

APPEAL FROM

PULASKI COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT

Hon. W illiam J. K irby, Judge

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

The Appellee’s Brief fails to respond directly

to the serious issues in this case or to Appellants’

arguments as set forth in their brief.

The defendants below were tried for an

alleged violation of Section 25-121 of the Little

Rock Code of Ordinances, and the trial judge read

the entire Ordinance to the jury as part of his

charge (R„75-76)'. The City o f Little Rock

may not confine constitutional scrutiny o f this

2

Ordinance by now stating the theory of the prose

cution to have been that Appellants were guilty

of violating only a particular part of the Ordi

nance (Brief for Appellee, p. 5). Stromberg

V. California, 283 U. S. 359 (1931); Cole V. Ar

kansas, 333 U.S. 196 (1948).

Appellee’s construction of the Ordinance is

self-contradictory. It first seeks to read the law

“ in its entirety” to discover a common denomi

nator of “unacceptable sexual behavior” and then

emphasizes the “ particular part of the Ordinance

violated” to rebut Appellants’ claim that the

Ordinance proscribes only public conduct. Ap

pellants submit that this is not “ rational inter

pretation.” 1

The unconstitutionality of a law purporting

to punish “ immorality” is clear, and while Ap

pellee has drawn this Court’s attention to cases

from other jurisdictions which have found suf

ficiently definite penal laws employing other

terms, Appellee has made no attempt to distin-

1 Appellee relies upon Beasley v. Parnell, 177 Ark. 912, 9

S.W. 2d 11 (1928). However, the statute in that case contained

no separate indication of legislative intent, while such intent is

made clear in this Ordinance by the inclusion of a paragraph

defining “public place” immediately following the paragraph-

ing setting out the criminal acts. The very title of the Ordi-

nance is revealing: Public places; immoral conduct within,

penalty (R.43). Appellants do not contend, as Appellee ap

parently believes, that this Court should read the word or as

the word “and.” Rather, the legislative intent to interdict only

public conduct is otherwise clear from the language of the

Ordinance, and proof of public misbehavior is an integral part

of any prosecution under this Ordinance.

aguish this Court’s condemnation of such

statute:

3

The standard of crime would be ever

varying, and the courts would constantly

be appealed to as the instruments of moral

reform, changing with all the fluctations

o f moral sentiment. The law is simply

null. The constitution, which forbids ex

post facto laws, could not tolerate a law

which would make an act a crime, or not,

according to the moral sentiment which

might happen to prevail with the judge

and jury after the act had been committed.

(Ex parte Jackson, 45 Ark. 158, 164

(1885 )).

Nor has Appellee sufficiently answered the

claim that the Ordinance is unconstitutionally

vague, for as pointed out in Appellants’ Brief and

as emphasized by this Court in Ex parte Jackson,

supra, the overbreadth of the Ordinance not only

causes problems of adequate notice but also leads

to unpredictable and capricious judicial applica

tion.

Finally, Appellee also mistakes the nature of

Appellants’ Fourth Amendment claims. Appel

lee as much as admits the illegality of the arrest

but argues that such an illegal arrest does not re

quire suppression of evidence previously ob

tained.2 The evidence here is in consequence

2 Appellee cites Perkins v. City of Little Rock to support

this proposition. There, however, the evidence consisted of

voluntary statements made after arrest, not before it.

■

'•

—

"■*

'--

---

---

t

r

"M

i'V

i-n

.

........... - ........ - — ...— __— . —....— .— ..... - It 11------------------------- ---

of the nighttime peeping of the officers through

the window of the apartment. Appellants con

cede the right of an officer, under Arkansas law,

to arrest when a misdemeanor is committed in

his presence. What Appellants cannot agree is

that the term ‘ ‘presence” includes the totally war

rantless, unauthorized peering into the window

o f a private apartment at 2 :30 A.M. by officers

standing within the curtilage of the property.

Such police action constitutes a violation o f the

constitutional rights to privacy which cannot

justify any prosecution based on what was ob

served. However great the harm of “ immoral”

conduct, to sanction such peeping-tom police

tactics would inflict a far greater injury upon

society and upon individual rights and the

sanctity of the home.

o

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for all the foregoing reasons, ap

pellants respectfully submit that the judgments

of the trial court should be reversed and dis

missed.

Respectfully submitted,

John W. W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants