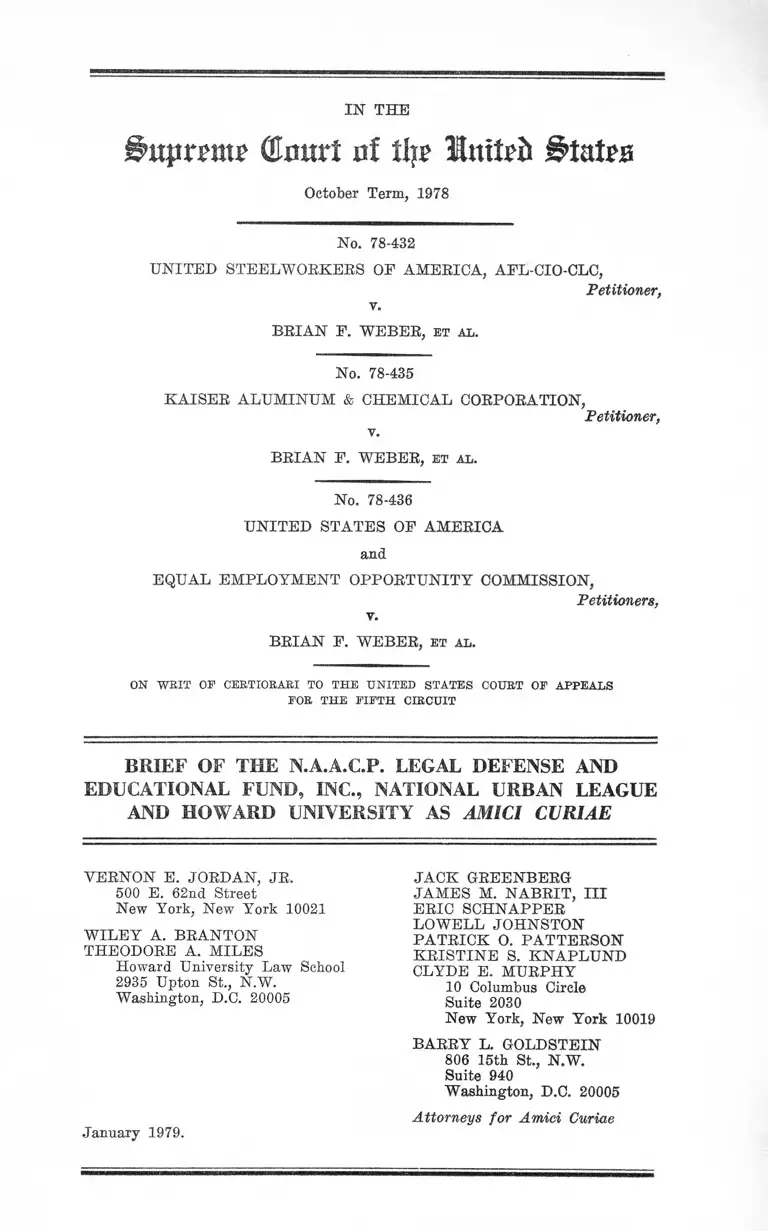

United Steel Workers of America v. Webber Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Steel Workers of America v. Webber Brief Amici Curiae, 1979. 9ed7bae8-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/25bfbe84-bb1c-4ecd-a859-662a61aaf1df/united-steel-workers-of-america-v-webber-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

GImtrf of % States

October Term, 1978

No. 78-432

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO-CLC,

Petitioner,

v.

BRIAN F. WEBER, e t a l .

No. 78-435

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION,

Petitioner,

v.

BRIAN F. WEBER, e t a l .

No. 78-436

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

and

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Petitioners,v.

BRIAN F. WEBER, e t a l .

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE

AND HOWARD UNIVERSITY AS AMICI CURIAE

YERNON E. JORDAN, JR.

500 E. 62nd Street

New York, New York 10021

WILEY A. BRANTON

THEODORE A. MILES

Howard University Law School

2935 Upton St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

January 1979.

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I II

ERIC SCHNAPPER

LOWELL JOHNSTON

PATRICK O. PATTERSON

KRISTINE S. KNAPLUND

CLYDE E. MURPHY

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

806 15th St., N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

INDEX

Page

Table of Authorit ies ...................... iii

1Interest of Amici ........................ .

Summary of Argument ........................ 6

ARGUMENT

I. Title VII Permits Employers and

Unions to Take Voluntary Race-

Conscious Affirmative Action .... 9

A. Legislative History: 1964 .... 9

B. Judicial and Executive

Interpretation: 1964-1972 .... 18

C. Legislative History: 1972 .... 21

D. EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative

Action ...................... 24

II. A Standard Permitting Employers

and Unions to Take Race-Conscious

Affirmative Action When They Have

a Reasonable Basis To Do So, Is

Consistent with Title VII and the

Constitution..................... 28

A. An Employer or Union May

Take Race-Conscious Affirma

tive Action Where It Acts Upon

a Reasonable Basis that such

Action Is Appropriate ....... 28

- 1

Page

3. An Action to Enforce the Fifth

Circuit's Construction of

Title VII Would Not Present

a "Case or Controversy" ....... 41

C. The Fifth Circuit Has Given

Title VII an Unconstitutional

Construction .................. 49

III. This Affirmative Action Plan Is

Permissible Under Title VII....... 56

A. The Plan Was Properly

Instituted ................... 56

B. The Plan Was Properly

Designed ............. 107

CONCLUSION .................................. 122

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

PAGE

Adams v. Richardson, 351 F.Supp.

636 (D.C. 1972) ................. 95

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody,

422 U.S.C. 405 (1975) ........... Passim

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1974) ........... 12,30

Associated General Contractors of

Mass., Inc. v. Altshuler,

361 F.Supp. 1293 (D.

Mass.), aff'd■, 490 F .2d 9

(1st Cir.)., cert denied,

416 U.S 957 (1974) ............. 107,115

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S 186

(1962) .......................... 43-44

Barlow v. Collins, 397 U.S.

159 (1970) ..................... 44

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S.

250 (1952) .................. . . .. 62

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497

(1954) .......................... 50

Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v.

Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017 (1st

Cir.), cert denied, 421 U.S.

910 (1975)

- iii -

23,114

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v.

Bridgeport Civil Service

Commission, 482 F.2d 1333

(2nd Cir. 1973), cert denied,

421 U.S. 991 (1975) ............. 115

Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 438 (1954) ................. 93

Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corp. , Civ. Action No. 67-86

(M.D. La. ) ...................... 33

Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum &

Chemical Corp., 408 F.2d

339 (5th Cir. 1969), re'g, 287

F. 2d 289 (E.D. La. 1968) ......... 33

Carey v. Piphus, 55 L.Ed.2d 252

(1978) .......................... 49

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482

(1977) .......................... 76

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S.

840 (1976) ...................... 34

Chicago, etc. R.R. v. Wellman, 143

U.S. 339 (1892) ................. 47

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v.

Local 542, Operating Engineers,

Civil Action No. 71-2698, (E.D.

Penn. Nov. 30, 1978) ............ 89

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Contractors Association v. Secretary

of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir.)

cert denied, 404 U.S. 854

(1971) .......................... 21,107

Crockett v. Green, 534 F.2d 715

(7th Cir. 1976) ................. 115

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321

(1977) .......................... 36,64,80,83

EEOC v. A.T.& T.’ Co., 556 F.2d

167 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied,

57 L.ed 2d 1161 ( 1978) .......... 115

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515

F.2d 301 (6th Cir.), vac and .... 49

rem on other grounds, 431

U.S. 951 ( 1977) ................. 115

Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western

Addition Community Organi

zation, 420 U.S. 50 (1975) ...... 120

Erie Human Relations Commission

v. Tullio, 493 F .2d 371

(3rd Cir. 1974) ................. 115

Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 747 (1976) ................. 2,17,49,120

Furnco Construction Corp. v.

Waters, 57 L.Ed 2d 957 (1978).... 81

PAGE

v -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Gaston County v. United States,

395 U.S 285 (1969) .............. 54-55

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert,

429 U.S 125 (1976) .............. 26

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401

U.S. 424 (1971) ................. Passim

Hazelwood School District v. United

States, 433 U.S. 299

(1977) ..................... ..... 36,65,76

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S 475

(1954) .......................... 50

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S 385

(1969) .......................... 50-51

International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977) . ............. 36,48-49,65

James v. Stockham Valves and

Fittings Co., 559 F.2d

310 (5th Cir.), cert denied,

434 U.S. 1034 (1978) ........... 99

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 U.S 189 (973) ............... 62

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v.

Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047

(5th Cir. 1969) .................. 18

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Lord v. Veazie, 8 How. 251

(1850) .......................... 47

Marchetti v. United States, 390

U.S. 39 (1968) .................. 48

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S.

39 (1971) .................. 32

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 ( 1973) ............. 11,34

Moore v. East Cleveland, 431 U.S.

494 ( 1977) ...................... 62

Moose Lodge No. 197 v. Irvis,

407 U.S. 163 (1972) ............. 54

Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053

(5th Cir.) (en banc), cert denied,

419 U.S 895 ( 1974) .............. 115

N.A.A.C.P v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th

Cir. 1974) ...................... 115

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S 415

(1963) .......................... 55

National League of Cities v.

Usery, 426 U.S 833 (1976) ....... 55

NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp.,

301 U.S 1 ( 1937) ................ 119

PAGE

- vii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

North Carolina State Board of

Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43

(1971) .......................... 49,51

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corp., 575 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir.

1978) ........................... 32,71,79

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974 ) --- 99

Railway Mail Association v. Corse,

326 U.S 88 (1945) ............. 51

Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke,

57 L.Ed.2d 750 (1978) ........... Passim

Rios v. Enterprise Association

Steamfitters Local 638, 501

F. 2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974) .......... 115

Robinson v. Union Carbide Corp.,

538 F.2d 652 (5th Cir. 1976) .... 100

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457

F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972) ........ 81

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) ..... 62

Sierra Club v. Morton, 405

U.S. 727 (1972) ................ 44

PAGE

- viii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Simon v. Eastern Kentucky Welfare

Rights Organization, 426 U.S.

26 ( 1976) ....................... 45

Sims v. Local 65 Sheet Metal Workers,

489 F.2d 1023 (6th Cir. 1973) --- 15

Skidmore v. Swift & Co,, 323 U.S. 26

134 (1944) ......................

Southern Illinois Builders Association

v. Ogilvie, 471 F,2d 680 (7th

Cir. 972) ....................... 21,115

Stevenson v. International Paper Co.,

516 F.2d 103 (5th Cir. 1975) .... 100

Swift & Co. v. Hocking Valley R.R.

Co., 243 U.S 281 (1917) ........ 46

United Jewish Organization v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 ( 1977)....... 105

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industries, Inc., 517 F.2d

826 (5th Cir.), cert. denied,

425 U.S 944 (1976) .............. 116

United States v. Allegheny-

Ludlum Industries, Inc.,

63 F.R.D. 1 (N.D. Ala. 1973) .... 117

United States v. Bethlehem Steel

Corp., 446 F .2d 652 (2nd Cir.),

(1971) .......................... 100

United States v. Carolene

Products, 304 U.S 144 (1938) ......... 62

IX

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

United States v. City of Chicago,

549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir.),

cert, denied, 434 U.S 875

(1878) .......................... 115

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86,

315 F.Supp. 1202 (W.D. Wash. 1979),

aff*d, 443 F .2d 544 (9th Cir.).

cert. denied, 404 U.S 981 (1971).. 19

United States v. Johnson, 319 U.S.

302 (1943) .......... 1 .......... 47-48

United States v. Local 38, IBEW, 428

F.2d 144 (6th Cir.) cert denied

400 U.S. 943 ( 1970) ............. 18

United States v. Local 212 IBEW, 472

F. 2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973) ........ 23,115

United States v. Masonry Contractors

Association, 497 F.2d 871 (6th

Cir. 1974) ............. 115

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc.,

479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973) .... 12,115

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers

Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th

Cir. 1969) ...................... 19

United States v. Wood Lathers Local

46, 471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir. ),

cert, denied, 412 U.S 939

(1973) ...................... H 5

United States Steelworkers of

America v. American Mfg. Co.,

363 U.S 564 (1960) .............. 119

x

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Develop

ment Corp., 429 U.S 252

(1972) .............. 88

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S 229

(1976) ......................... 88

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530

F.2d 1159 (5th Cir 1976), cert.

denied, 429 U.S 861 ( 1976) ...... 72

PAGE

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S 490

(1975) .......................... 45

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes,

Executive Orders and Regulations:

United States Constitution, Fifth

Amendment ....................... 51

United States Constitution,

Fourteenth Amendment ............ 51

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261 ........ 21

Fugitive Slave Act, 11 Stat.

462, §7 ......................... 52

42 U.S.C. §2Q00e, et seq., Title

VII of the Civil Rights

of 1964 (as amended 1972 ) ...... 13-15

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. 51996(c) ......... 56

xi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Executive Order No. 10,925, 3 C.F.R.

PAGE

443 (1959-63 Comp.) ............. 106

Executive Order No. 11,246,30 Fed.

Reg. 12319, as amended, 32

Fed. Reg. 14303.................. Passim

41 C.F.R. 60-2 (Revised Order

No. 4) .......................... 104

Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission Uniform Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures,

43 Fed. Reg. 38290, 29 C.F.R.

Part 1607 (1978) ................. 28,84-86

Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission Guidelines on Affirmative

Action, 44 Fed. Reg. 4422,

29 C.F.R. Part 1608 (1978) ....... Passim

Equal Employment Opportunity

Coordinating Council, Policy

Statement on Affirmative Action

Programs for State and Local

Governments, 41 F.R. 38

81976) .......................... 28

Executive Decisions and Opinions:

EEOC Decision 74-196,10 FEP Cases

269 (April 2, 1974) ............. 27

EEOC Decision 75-268,10 FEP Cases 1502,

(May 30, 1975) ....... 28

Xll

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Office of the Solicitor, U.S. Department

of Labor, Legal Memorandum, in Hearings

on The Philadelphia Plan and S.931 Before

the Subcomm. on Separation of Powers of

the Senate Comm, on the Judiciary, 91st

Cong., 1st Sess. 225 (1969) ..... 20

42 Opinion of Attorney General

No. 37 (Sept. 22, 1969) ......... 20

Legislative History:

110 Cong. Rec. 6549 (1964) ............ 16

110 Cong. Rec. 7214 (1964) ............ 14,16

110 Cong. Rec. 9881 (1964) ............ 14-16

110 Cong. Rec. 9882 (1964) ............ 15-16

110 Cong. Rec. 12723 ( 1964) .......... 15

118 Cong. Rec. 3460-63 ( 1972) ........ 22

Hearings on Civil Rights Before

Subcommittee No. 5 of the

House Committee on the

Judiciary, 88th Cong.

1st Sess. 2300-03 (1963) ________ 10

Hearings on Equal Empoloyment

Opportunity Before the

General Subcommittee on

Labor of the House Com

mittee on Education and

Labor 88th Cong. 1st

Sess. 3 (1963) .................. 9

- xiii -

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Hearings on Equal Empoloyment Oppor

tunity Before the Subcomm. on

Employment and Manpower of the

Senate Comm, on Labor and Public

Welfare, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

116-17, 321-29, 426-30, 449-52,

PAGE

492-94 (1963) ................... 10

H.R. Rep. 914, 88th Cong. 1st

Sess............................. 22

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong.

1st Sess. 8 (1971) .............. 22

S. Rep. No 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st

Sess. 5 (1971) .................. 9-12

Other Authorities:

Adminstrative Office of the United States

States Courts, 1976 Annual Report

of the Director .............. . 34

Administrative Office of the United States

Courts, 1977 Annual Report of

the Director ................ . 35

Administrative Office of the United

States Courts, 1978 Annual Report

of the Director ................. 35

Chayes, the Role of the Judge in Public

Law Litigation, 89 Harv. La. Rev.

1281 (1976) ............. ........ 61

Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A

Study in the Dynamics of

Executive Power, 39 U. Chi.

L. Rev. 732 ( 1972) .............. 20,22-23,41

- xiv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission Legislative History of

Titles VII and XI of Civil Rights

Act of 1964 ..................... 11,17

Committee on Government Contracts,

Patterns for Progress: Final

Report to President Eisenhower

(I960) .................. 106

Finkelstein, The Applicatin of Statisti

cal Decision Theory to the Jury

Discrimination Cases, 80 Harv.

L. Rev. 338 (1966) ............... 76

Gould, Black Workers in White Unions,

(1977) ..................... 91

Hall, Black Vocational, Technical and

Industrial Arts Education

(American Technical Society

1973) ................................ 93

Hill, Black Labor and the American Legal

System: Race, Work and the Law 91

'(1977) ...................... ...

Jones, The Bugaboo of Employment

Quotas, 1970 Wise. L. Rev.

341 ................ ............. 107

Karson and Rodosh, The American Federa

tion of Labor and the Negro Worker,

1894—1949", in The Negro and the

American Labor Movement (ed.

Jacobson, Anchor 1968) .. .............. 96

PAGE

xv -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Marshall, The Negro and Organized

' Labor, (1965) ................... 91,94

PAGE

Marshall, "The Negro in Southern Unions,"

in The Negro and the American Labor

Movement (ed. Jacobsen, Anchor

1968) ........................... 96,99

Marshall and Briggs, the Negro and

Apprenticeship (1967) ......... 91,98,102-103

McPherson., The Political History of

the United States of America

During the Period of Recon

struction (reprinted 1969) ....... 93

Mosteller, Rourke and Thomas,

Probability With Statistical

Applications, (1970) ............ 76

Myrdal, An American Dilemma, (Harper

& Row, ed., 1962) .............. 91,96-97,100

N.A.A.G.P. Legal Defense And Educa

tional Fund, Inc., Brief as

Amicus Curiae, No. 76-811 ....... 52

Northrup, Organized Labor and the

Negro (1944) ................... 91,96-97,100

Sovern, Legal Restraints on Racial

Discrimination in Employment

(1966) 7. ........................ 9,106

Spero and Harris, The Black Worker

(Atheneum, ed., 1968) ........... 91-92

xvi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

*PAGE

State Advisory Committee, U.S. Com

mission on Civil Rights,

50 States Report (1961) ......... 95

tenBroek, Equal Under Law, (1951) .... 52

United States Commission on Civil

Rights, Employment (1961) ........ 94

United States Commission on Civil

Rights, The Challenge Ahead

(1976) .......................... 98,103

United States Dept, of Commerce,

Bureau of the Census, 1970 Census

of Population; 1970, Vol. 1,

Characteristics of the Popula

tion, Part 20- Louisiana

(1973)........................... 67-68,72-74

Weaver, Negro Labor, A National

Problem, (1964) ............. 91,93-94,99,100

Weinstein, 1 Evidence ................ 61

Wright and Graham, Federal Practice

and Procedure, §5102 (1977) ..... 61

xvi 1

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1978

No. 78-432

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO-CLC,

Petitioner,

v.

BRIAN F. WEBER, et al.

No. 78-435

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION,

Petitioner,

v.

BRIAN F. WEBER,

No. 78-436

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

and

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Petitioners,

v.

BRIAN F. WEBER, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., NATIONAL

URBAN LEAGUE AND HOWARD UNIVERSITY

AS AMICI CURIAE

Interest of Amici

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation

- 2 -

established under the laws of the State of New

York. It was founded to assist black persons to

secure their constitutional and statutory rights

by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter

declares that its purposes include rendering legal

services gratuitously to black persons suffering

injustice by reason of racial discrimination. For

many years attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund

have represented parties in litigation before this

Court and the lower courts involving a variety of

race discrimination issues regarding employment.

See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 (1975); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 ( 1976). The Legal Defense Fund

believes that its experience in such litigation

and the research it has performed will assist the

Court in this case. The parties have consented to

the filing of this brief and letters of consent

have been filed with the Clerk.

The National Urban League, Incorporated, is a

charitable and educational organization organized

as a not-for-profit corporation under the laws of

the State of New York. For more than 69 years,

- 3 -

the League and its predecessors have addressed

themselves to the problems of disadvantaged

minorities in the United States by improving the

working conditions of blacks and other minorities,

and by fostering better race relations and increas

ing understanding among all persons.

Howard University was established as a

private nonsectarian institution by Act of Cong

ress on March 2, 1867. Since its inception, the

University has grown from six departments in 1867

to its present composition of seventeen schools

and colleges. Nearly 40,000 students have receiv

ed diplomas, degrees or certificates from Howard;

of that total, well over 14,000 have received

graduate and professional degrees. Throughout

this century of growth, the unique mission of the

University has been supported in the main by

congressional appropriations. Since 1928 Howard

University, while remaining a private institution,

has received continuous annual financial support

from the federal government.— ̂ Today, the Uni-

JJ The Committee on Education commenting on the

bill to amend section 8 of an act entitled "An Act

to incorporate the Howard University..." stressed:

- 4 -

versity's land, buildings and equipment are

valued at more than 150 million dollars. Thus,

both the executive and legislative branches are

sensitive to the need to maintain Howard as an

institution in service to blacks.

_1_/ Cont ' d

Apart from the precedent established by

45 years of congressional action, the commit

tee feels that Federal aid to Howard Univer

sity is fully justified by the national

importance of the Negro problem. For many

years it has been felt that the American

people owed an obligation to the Indian,

whom they dispossessed of his land, and

annual appropriations of sizable amounts

have been passed by Congress in fulfillment

of this obligation....

Moreover, financial aid has been and

still is extended by the Federal Government

to the so-called land-grant colleges of the

various States. While it is true that

Negroes may be admitted to these colleges,

the conditions of admission are very much

restricted, and generally it may be said that

these colleges are not at all available to

the Negro, except for agricultural and

industrial education. This is particularly

so in the professional medical schools, so

that the only class A school in America for

training colored doctors, dentists, and

- 5 -

Howard University has a unique interest in

the resolution of this case by the Supreme Court.

This case raises questions of great importance

about the permissible scope of voluntary affirma

tive action under Title VII. Affirmance of the

lower court's proscription against voluntary

intitatives will chill voluntary programs in

particular and affirmative action generally.

1/ Cont 'd

pharmacists is Howard University, it being

the only place where complete clinical work

can be secured by the colored student.

Committee on Education Report Accompanying

H.R. 8466 (1926). See also, 14 Stat.

1021 (1926).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. In enacting Title VII in 1964 Congress

neither expressly approved nor expressly dis

approved race-conscious efforts to correct the

effects of discriminatory practices. However,

subsequent judicial decisions and executive

actions established that Title VII permitted, and

in some circumstances required, the remedial use

of race. In amending Title VII in 1972 Congress

approved this interpretation of the statute.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's

Guidelines on Affirmative Action correctly codi

fied this interpretation authorizing employers and

unions to adopt racial preferences as remedial

measures where they have a reasonable basis for

that action.

II. Race-conscious affirmative action is

justifiable where an employer or union has a

reasonable basis for believing that it might

otherwise be held in violation of the law.

The employer or union need not admit nor prove

7

prior discrimination, and it may take race

conscious action to remedy the disadvantages

affecting minorities as a result of discrimination

by others. A more rigid standard — like that

adopted by the majority of the Fifth Circuit

requiring proof or admission of discriminatory

practices — would largely eliminate voluntary

affirmative action. Moreover, a lawsuit challeng

ing race-conscious action under that standard does

not present a case or controversy because it is

not in the interest of either litigant to prove

the central factual issue, prior discrimination.

Finally, the Fifth Circuit's standard, if accepted

by this Court, would raise serious questions as to

the constitutionality of Title VII.

III. Kaiser and the Steelworkers properly

instituted a race-conscious plan because they

had a reasonable basis to believe that their

craft selection practices had violated, and

without affirmative action would continue to

violate, both Title VII and Executive Order

11,246. Moreover, it was appropriate and socially

responsible for the Company and the Union to

design a program which would remedy some of the

- 8 -

effects of decades of discriminatory practices by

employers, unions, and govermental bodies which

had denied training opportunities to blacks in the

skilled crafts.

The affirmative action plan was proper since

it expanded the employment opportunities of all

workers, black and white. The race-conscious

component of the plan conformed to provisions

which had been approved by courts and by adminis

trative agencies and was designed as an interim

measure which would terminate after remedying the

discriminatory practices. Finally, it resulted

from collective bargaining in which the interests

of all the workers were represented and it thus

furthered the policies favoring the voluntary

resolution of both labor and discrimination

disputes.

- 9 -

ARGUMENT

I. TITLE VII PERMITS EMPLOYERS AND

UNIONS TO TAKE VOLUNTARY RACE-

CONSCIOUS AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

A. Legislative History: 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the first

comprehensive federal legislation ever to address

the pervasive problem of discrimination against

blacks in modern American society. See M. Sovern,

Legal Restraints on Racial Discrimination in

Employment 8 (1966). Extensive hearings had

focused the attention of Congress on the adverse

social and economic consequences of discrimination

2/against blacks m employment and other fields,—

and when the House Judiciary Committee issued

its report on the bill which became the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, it clearly stated that a

primary objective of the Act was to encourage

voluntary action to eliminate the effects of

discrimination against black citizens:

2/ See, e.g., Hearings on Equal Employment

Opportunity Before the General Subcomm. on Labor

of the House Comm, on Education and Labor, 88th

10

In various regions of the country

there is discrimination against some minority

groups. Most glaring, however, is the

discrimination against Negroes which exists

throughout our Nation. Today, more than 100

years after their formal emancipation,

Negroes, who make up over JO percent of our

population, are by virtue of one or another

type of discrimination not accorded the

rights, privileges, and opportunities which

are considered to be, and must be, the

birthright of all citizens.

* * *

No bill can or should lay claim to

eliminating all of the causes and conse

quences of racial and other types of dis

crimination against minorities. There

is reason to believe, however, that national

leadership provided by the enactment of

Federal legislation dealing with the most

troublesome problems will create an atmos

phere conducive to voluntary or local resolu

tion of other forms of discrimination.

2_/ Cont' d

Cong., 1st Sess. 3, 12-15, 47-48, 53-55, 61-63

(1963); Hearings on Civil Rights Before Subcomm.

No. 5 of the House Comm, on the Judiciary,

88th Cong., 1st Sess. 2300-03 (1963); Hearings on

Equal Employment Opportunity Before the Subcomm.

on Employment and Manpower of the Senate Comm, on

Labor and Public Welfare, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

116-17, 321-29, 426-30, 449-52, 492-94 (1963).

li

lt is, however, possible and necessary

for the Congress to enact legislation

which prohibits and provides the means of

terminating the most serious types of dis

crimination. .. . H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1963), reprinted in

EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VII and

XI of Civil Rights Act of 1964 at 2018.

This Court has repeatedly recognized the

purpose of the Act: "The objective of Congress in

the enactment of Title VII ... was to achieve

equality of employment opportunities and remove

barriers that have operated in the past to favor

an identifiable group of white employees over

other employees." Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424, 429-30 (1971); Albemarle Paper Co.

v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417 (1975). "The language

of Title VII makes plain the purpose of Congress

to assure equality of employment opportunities

and to eliminate those discriminatory practices

and devices which have fostered racially strati

fied job environments to the disadvantage of

minority citizens." McDonnell Douglas Corp. v .

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800 (1973). This Court also

has recognized that Congress selected "[cjoopera-

12

tion and voluntary compliance ... as the preferred

means for achieving this goal." Alexander v .

Gardner-Denver Co. , 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974). The

Court, in keeping with the intent of Congress (see

H.R. Rep. No. 914, pp. 10-11, supra), has endorsed

the imposition of judicial remedies under Title

VII as "the spur or catalyst which causes employ

ers and unions to self-examine and to self-evalu-

ate their employment practices and to endeavor to

eliminate, so far as possible, the last vestiges

of an unfortunate and ignominious page in this

country's history." Albemarle Paper Co. v .

Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 417-18, quoting United

States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354, 379

(8th Cir. 1973).

The record in this case shows that what

Congress intended and what the Court has endorsed

is precisely what happened: Kaiser and the

Steelworkers examined their practices and con

cluded that there was a reasonable basis to

believe that they would be found liable for

discrimination against blacks; they had "looked at

the large sums of money that companies were being

forced to pay, and we looked at our problem,

which was that we had no blacks in the crafts, to

13

speak of," A. 83 (English); and they volun

tarily adopted a plan to bring blacks into craft

jobs. See Section IIIA and n. 26, infra. In the

absence of compelling legislative history to the

contrary, Title VII cannot be read to foreclose

the use of such race-conscious numerical plans to

accomplish the primary purpose of the Act.

The legislative history of the orginal

enactment of Title VII in 1964 conclusively

demonstrates neither approval nor disapproval by

Congress of race-conscious efforts to correct the

effects of the past discriminatory exclusion

of blacks from training and job opportunities.

The major argument against congressional approval

of such efforts is premised upon the addition to

the bill on the Senate floor of §703(j), which

states that nothing in Title VII shall "require"

preferential treatment because of race "on account

3/of an imbalance...."—

3/ "Nothing contained in this subchapter shall

be interpreted to require any employer, employment

agency, labor organization, or joint labor-manage

ment committee subject to this subchapter to grant

preferential treatment to any individual or to any

group because of the race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin of such individual or group on

account of an imbalance which may exist with

- 14

Prior to the adoption of this amendment,

the Senate floor managers of the bill had explain

ed that Title VII would not require an employer to

maintain a racially balanced work force because,

While the presence or absence of other

members of the same minority group in the

work force may be a relevant factor in

determining whether in a given case a deci

sion to hire or to refuse to hire was based

on race, color, etc., it is only one factor,

and the question in each case would be

whether that individual was discriminated

against . 110 Cong. Rec. 7213 (1964) (inter

pretive memorandum of Senators Clark and

Case).

Notwithstanding this assurance, opponents of

the bill continued to argue "that a quota system

will be imposed, with employers hiring and unions

accepting members, on the basis of the percentage

of population represented by each specific minor

ity group." Id. at 9881 (remarks of Senator

3/ Cont ' d

respect to the total number or percentage of

persons of any race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin employed by any employer, referred

or classified for employment by any employment

agency or labor organization, admitted to member

ship or classified by any labor organization, or

admitted to, or employed in any apprenticeship or

other training program, in comparison with the

total number or percentage of persons of such

- 15

Allott). To put these doubts to rest, Senator

Allott proposed an amendment precluding a finding

of unlawful discrimination "solely on the basis of

evidence that an imbalance exists without

supporting evidence of another nature that the

respondent has engaged or is engaging in such

practice." Id_. at 9881-82. The sense of this

amendment was incorporated, in the language

of §703(j), as part of the Dirksen-Mansfield

compromise which resulted in the end of the

Senate debate and the enactment of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. As Senator Humphrey explained

in presenting the compromise amendments to the

Senate,

A new subsection 703(j) is added to deal

with the problem of racial balance among

employees. The proponents of this bill have

carefully stated on numerous occasions that

Title VII does not require an employer

to achieve any sort of racial balance in his

work force by giving preferential treatment

to any individual or group. Since doubts

have persisted, subsection (j) is added to

state this point expressly. Id. at 12723.

3\j Cont1 d

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin

in any community, State, section, or other area,

or in the available work force in any community,

State, section, or other area." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-

2(j).

16

This legislative history does not indicate

that Congress intended to forbid race-conscious

numerical action to correct the effects of past

discrimination. The concern of Congress in

enacting §703(j) was not directed to the question

whether race could be taken into account for

remedial purposes; rather, its intent was to

ensure that findings of discrimination would not

be based solely on evidence of statistical im

balance and thereby to allay the fear that Title

VII would have the effect of requiring employers

to maintain a specific racial balance of employ

ees.— ^The language of §703(j), like that of

4/ Senators Clark and Case also stated that "any

deliberate attempt to maintain a racial balance,

whatever such a balance may be, would involve a

violation of Title VII because maintaining such a

balance would require an employer to hire or to

refuse to hire on the basis of race." 110 Cong.

Rec. at 7213. See also id_. at 6549 (remarks of

Senator Humphrey). Senator Allott believed that

"a quota system of hiring would be a terrible

mistake," but did not indicate whether such a

system would be unlawful. _Id_. at 9881-82.

These statements may indicate an intention to

prohibit employers from deliberately maintaining

a particular racial composition of employees as an

end in itself, but they do not suggest any inten-

- 17

§703(h), does not restrict or qualify otherwise

appropriate remedial action but defines what is

and what is not an illegal discriminatory prac

tice. Cf. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

supra, 424 U.S. at 758-62. Indeed, the legisla

tive history of the 39 64 Act shows no detailed

consideration of the scope and nature of remedial

actions which might be taken by employers and

unions or ordered by the courts, and it shows no

consideration whatever of the permissibility of

race-conscious remedial measures. See generally,

EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VII and XI of

Civil Rights Act of 1964. There is no indication

that "in the absence of any consideration of the

question, ... Congress intended to bar the use of

racial preferences as a tool for achieving the

objective of remedying past discrimination or

other compelling ends." Bakke, supra, 57 L.Ed.2d

at 803 n.17 (opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall,

Blackmun, JJ.).

4/ Cont' d

tion to foreclose "the voluntary use of racial

preferences to assist minorities to surmount the

obstacles imposed by the remnants of past dis

crimination." Regents of the University of Cali

fornia v. Bakke, 57 L.Ed.2d 750, 803 n. 17 ( 1978)

(opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall, Blackmun,

JJ.).

18

B. Judicial and Executive Interpreta

tions: 1964-1972

In the years following the enactment of Title

VII, the courts and federal executive agencies

recognized that Congress had not intended to

outlaw one of the most effective means of remedy

ing past discrimination, and accordingly they

interpreted Title VII to permit, and in some

instances to require, the use of race-conscious

numerical remedies. The courts held that §703(j)

could not be construed as a ban on such remedies:

"Any other interpretation would allow complete

nullification of the stated purposes of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964." United States v. Local 38,

IBEW, 428 F .2d 144, 149-50 (6th Cir.), cert.

denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1,970). Title VII was held

to authorize remedial orders requiring union

referrals of one black worker for each white

worker,— specific percentages of blacks in

regular apprenticeship classes and special appren-

5/ Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407

F .2d 1047, 1055 (5th Cir. 1969).

19

ticeship programs for blacks only,— ^and pref

erential work registration, examination, and

referral procedures for blacks with experience in

the construction industryAs the Second Cir

cuit stated in summarizing these decisions,

"while quotas merely to attain racial balance are

forbidden, quotas to correct past discriminatory

practices are not." United States v. Wood Lathers

Local 46, 471 F . 2d 408, 413 (2d Cir.), cert.

denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973) /

Also during the period between the enactment

of Title VII in 1964 and its amendment in 1972,

the Department of Labor determined that numerical

goals and timetables were necessary to implement

6/ United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 315

F.Supp. 1202, 1247-48 (W.D. Wash. 1970), aff'd,

443 F.2d 544, 553 (9th Cir.), cert denied, 404

U.S. 984 (1971).

JJ United States v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 36,

416 F.2d 123, 133 (8th Cir. 1969).

8/ The courts of appeals in eight circuits

have upheld the authority of the district courts

to order race-conscious numerical relief under

Title VII or other federal fair employment laws,

see nn. 94-95 , infra.

- 20

the equal employment opportunity and affirmative

action obligations of government contractors under

Executive Order No. 11,246, and that a permissible

method of meeting the goals and timetables in the

construction industry was the hiring of one minor

ity craftsman for each nonminority craftsman.

See Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A Study in the

Dynamics of Executive Power, 39 U . Chi. L . Rev.

723, 739-43 (1972). Both the Department of

Labor— ^and the Department of Jus t ice^-^ found

no conflict between such race-conscious measures

and the provisions of Title VII. The courts

agreed, holding that § 7 0 3 (j ) did not impose

any limitation on actions taken pursuant to the

Executive Order program, and that,

To read §703(a) in the manner suggested

by the plaintiffs, we would have to attribute

to Congress the intention to freeze the

status quo and to foreclose remedial action

9J Office of the Solicitor, U.S. Department of

Labor, Legal Memorandum, in Hearings on the

Philadelphia Plan and S. 931 Before the Subcomm.

on Separation of Powers of the Senate Comm, on the

Judiciary, 91st Cong., 1st Sess. 255, at 274

(1969).

10/ 42 Op. Att'y Gen. No 37 (Sept. 22, 1969).

- 21

under other authority designed to overcome

existing evils. We discern no such intention

either from the language of the statute

or from its legislative history. Contractors

Association v. Secretary of Labor, 442

F.2d 159, 173 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied, 404

U.S. 854 (1971).

See also Southern Illinois Builders Association

v. Ogilvie, 471 F.2d 680, 684-86 (7th Cir. 1972),

and cases cited therein. Thus, by the time

Congress considered the 1972 amendments to Title

VII, it was well established that the 1964 Act

permitted race-conscious remedial action.

C. Legislative History: 1972

In amending Title VII by the enactment of the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L.

No. -92-261, Congress approved these interpreta

tions of Title VII. Congress was aware that

Employment discrimination as viewed

today is a complex and pervasive

phenomenon. Experts familiar with the

subject now generally describe the problem in

terms of "systems" and "effects" rather

than simply intentional wrongs, and the

literature on the subject is replete with

discussions of, for example, the mechanics

of seniority and lines of progression,

perpetuation of the present effect of pre-act

- 22

discriminatory practices through various

institutional devices, and testing and

validation requirements. S. Rep. No. 92-415,

92d Cong., 1st Sess. 5 (1971).

The committee reports specifically cited

cases which had approved race-conscious solutions

for these complex and pervasive problems. See,

e.g., id. at 5, n.l; H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d

Cong., 1st Sess. 8 n.2, 13 n.4 (1971). And, in

a section-by-section analysis presented to the

Senate with the conference report, the Senate

sponsors of the legislation stated that,

In any area where the new law does not

address itself, or in any area where a speci

fic contrary intention is not indicated, it

was assumed that the present case law as

developed by the courts would continue to

govern the applicability and construction of

Title VII. 118 Cong. Rec. 3460-63 ( 1972),

reprinted in EEOC, Legislative History of the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of. 1972, at

1844.

See Bakke, supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 811 n.28 (opinion

of Brennan, White, Marshall, Blackmun, JJ.).

Moreover, with full awareness of the judicial

decisions interpreting Title VII to permit the

remedial use of race, Congress not only confirmed

but expanded the remedial authority of the courts

by amending §706(g) to provide expressly that

appropriate affirmative action under that section

"is not limited to" reinstatement, hiring, and an

award of back pay, and that a remedial order may

- 23

include "any other equitable relief as the

court deems appropriate." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g).

See Comment, The Philadelphia Plan, supra,

39 U. Chi. L. Rev. at 759 n.189.

Finally, "Congress, in enacting the 1972

amendments to Title VII, explicitly considered and

rejected proposals to alter Executive Order

11,246 and the prevailing judicial interpretations

of Title VII as permitting, and in some circum

stances requiring, race conscious action." Bakke,

supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 811 n.28 (opinion of Brennan,

White, Marshall, Blackmun, JJ.). The detailed

history of the Dent and Ervin amendments and their

rejection by the House and Senate has been docu

mented elsewhere and need not be repeated here.

See Comment, The Philadelphia Plan, supra, 39

U. Chi. L. Rev. at 751-57. See also, Bo s ton

Chapter, NAACP, Inc, v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017,

1028 (1st Cir. 1974), cert. denied, 421 U.S. 910

(1975); United States v. Local 212, IBEW, 472 F.2d

6 34 , 636 ( 6th Cir. 1973). In sum, " [ e ]xecut ive,

judicial, and congressional action subsequent to

the passage of Title VII conclusively established

that the Title did not bar the remedial use of

race." Bakke, supra, at 811 n.28 (opinion of

Brennan, White, Marshall, Blackmun, JJ.).

- 24

D. EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative Action

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

recently codified and reaffirmed this interpreta

tion of Title VII in its Guidelines on Affirmative

Action, 44 Fed. Reg. 4421-30 (Jan. 19, 1979), 29

C.F.R. Part 1608. These guidelines were proposed

in part to encourage voluntary compliance by

"authorizing employers to adopt racial preferences

as a remedial measure where they have a reason

able basis for believing that they might otherwise

be held in violation of Title VII." Bakke,

supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 818 n.38 (opinion of Brennan,

White, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ.). Under

the guidelines an employer or union, following a

reasonable self-analysis . of its practices which

discloses a reasonable basis for concluding that

action is appropriate, may voluntarily take

reasonable affirmative action including the use of

"goals and timetables or other appropriate employ

ment tools which recognize the race, sex, or

national origin of applicants or employees." 29

C.F.R. §1608.4(c). Such action may be taken where

there is a reasonable basis for believing that it

is an appropriate means of, inter alia, correcting

the effects of past discrimination, eliminating

- 25

the adverse impact on minorities of present

practices, or terminating disparate treatment. 29

C.F.R. §§1608.3, 1608.4(b). It is not necessary

for an employer or union to establish that it has

violated Title VII in the past; there is no

requirement of an admission or formal finding of

past discrimination, and affirmative action may be

taken without regard to arguable defenses which

might be asserted in a Title VII action brought on

behalf of minorities. 29 C.F.R. §1608.4(b). See

Section IIA, infra. The guidelines recognize

that

Voluntary affirmative action to improve

opportunities for minorities and women must

be encouraged and protected in order to

carry out the Congressional intent embodied

in Title VII. Affirmative action under

these principles means those actions appro

priate to overcome the effects of past

or present practices, policies, or other

barriers to equal employment opportunity.

Such voluntary affirmative action cannot be

measured by the standard of whether it would

have been required had there been litigation,

for this standard would undermine the legis

lative purpose of first encouraging voluntary

action without litigation. Rather, persons

subject to Title VII must be allowed flexi

bility in modifying employment systems and

practices to comport with the purposes

of Title VII. Correspondingly, Title VII

must be construed to permit such voluntary

- 26

action, and those taking such action should

be afforded ... protection against Title VII

liability ___ 29 C.F.R. §1608.1(c).

These guidelines "constitute 'the administra

tive interpretation of the Act by the enforcing

agency,' and consequently they are 'entitled to

great deference."' Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

supra, 422 U.S. at 431; Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

supra, 401 U.S. at 433-34. The degree of defer

ence to be accorded to such an interpretation

depends upon "the thoroughness evident in its

consideration, the validity of its reasoning,

its consistency with earlier and later pro

nouncements, and all those factors which give

it power to persuade, if lacking power to con

trol." General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 * &

U.S. 125, 142 (1976), quoting Skidmore v. Swift

& Co., 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944).

When judged by these standards, the Guide

lines on Affirmative Action are entitled to great

weight. First, the EEOC's careful and thorough

consideration is evident: the proposed guidelines

were intitally issued on December 28, 1977, 42

Fed. Reg. 64,826; comments were received from

almost 500 individuals and organizations ; the

- 27

Commission considered this Court's opinions in the

Bakke case before taking any final action; and

substantial changes were made before the Commis

sion voted to approve the guidelines in final form

on December 11, 1978. See Supplementary Informa

tion: An Overview of the Guidelines on Affirmative

Ac t ion, 44 Fed. Reg. at 4422-23. The EEOC's

extensive consideration of the comments, the legal

authorities, -and the precise wording of the

guidelines is reflected in some detail in the

overview issued with the final guidelines. H_. at

4422-25. Second, the validity of the reasoning

set forth in the guidelines is apparent from the

legislative history of the 1964 enactment and the

1972 amendment of Title VII, as well as from

judicial and other executive agency interpreta

tions of the statute. See pp. 18-21, supra.

Finally, the guidelines are fully consistent with

prior interpretations of Title VII by the EEOC

expressly approving "[n]umerical goals aimed at

increasing female and minority employment" as "the

cornerstone of . a[n affirmative action]

plan." EEOC Decision 74-106, 10 FEP Cases 269,

28

274 (April 2, 1974); EEOC Decision 75-268, 10 FEP

Cases 1502, 1503 (May 30, 1975). See also, Equal

Employment Opportunity Coordinating Council,

Policy Statement on Affirmative Action Programs

for State and Local Government Agencies, 41 Fed.

Reg. 38,814 (Sept. 13, 1976), reaffirmed and

extended to all persons subject to federal equal

employment opportunity laws and orders in the

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce

dures, 43 Fed. Reg. 38,290, 38,300 (Aug. 25,

1978), 29 C.F.R. §1607.13B.

II. A STANDARD PERMITTING EMPLOYERS AND

UNIONS TO TAKE RACE-CONSCIOUS

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION WHEN THEY HAVE A

REASONABLE BASIS TO DO SO IS CON

SISTENT WITH TITLE VII AND THE

CONSTITUTION

A. An Employer or Union May Take Race-Con

scious Affirmative Action Where It Acts

upon a Reasonable Belief that such

Action Is Appropriate

An employer when considering whether to

institute a race-conscious affirmative action

plan, or a court when reviewing a challenge to

such a plan, need only determine that there is a

reasonable basis for the plan in order to conclude

that the plan is lawful. The employer is not

required to admit that it had engaged in unlawful

- 29

prior discriminatory practices or to submit

evidence sufficient for a court to find that the

employer had violated the fair employment laws in

order to justify the institution of the plan.

EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative Action, 29 C.F.R.

51608.1(c). See Section ID, supra. A rigid

standard requiring conclusive proof of prior

discrimination would largely eliminate voluntary

affirmative action, see pp. 32-34, infra. The

circumstances which constitute a reasonable basis

for instituting an affirmative action plan vary

according to the particular employment situation.

However, an employer or union may develop a race

conscious affirmative action plan when there is

reason to believe that such action is appropriate,

inter alia, (1) to provide a remedy for prior

discriminatory practices of the employer or union,

(2) to insure the legality of current practices,

(3) to provide a remedy for discriminatory prac

tices related to the business of the employer or

union, or (4) to comply with Executive Order No.

11,246 or other legal requirements for affirmative

- 30 -

action. — ^Moreover, the action undertaken must

be reasonably related to the identified problems

which justify the institution of the plan, see

Section III B, infra■

In enacting Title VII Congress selected

"[c]ooperation and voluntary compliance ... as

the preferred means for achieving" the elimination

of discrimination in employment. Alexander v .

Gardner-Denver Co., supra, 415 U.S. at 44. The

standard for determining whether an affirmative

action plan is lawful under Title VII must simi

larly encourage voluntary compliance and voluntary

action. The standard adopted by a majority of the

court below, which would require an employer to

admit that it was guilty of unlawful discrimina

tory practices or to submit conclusive proof of

such practices before it could lawfully institute

an affirmative action plan, would frustrate

the purposes of Title VII.

11/ Of course, in certain circumstances an

employer or union may be required to institute an

affirmative action program. The justifications

for race-conscious affirmative action which are

listed are not exclusive but rather those that

are relevant to the affirmative action plan

designed by Kaiser and the Steelworkers.

- 31

[T]he standard produces ... an end to

voluntary compliance with Title VII. The em

ployer and the union are made to walk a

high tightrope without a net beneath them.

On one side lies the possibility of lia

bility to minorities in private actions,

federal pattern and practice suits, and

sanctions under Executive Order J1246.

On the other side is the threat of private

suits by white employees and, potentially,

federal action ... [T]he defendants could

well have realized that a victory at the cost

of admitting past discrimination would be a

Pyrrhic victory at best. G. Pet. 32a-34al2/

(Wisdom, J., dissenting).13/

12/ This form of citation refers to the petition

for a writ of certiorari filed by the United

States and the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission.

13/ Ironically, if the applicable standard were

to require conclusive proof or an admission of

prior discrimination, then the back pay remedy

which the Court indicated should provide a "spur

or catalyst" for voluntary compliance, Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 417-18,

would instead provide a barrier to voluntary

compliance. The admission of prior discrimination

or the submission of conclusive proof of discrimi

nation would serve as an open invitation for a

suit seeking back pay by black workers. The

failure of the company to admit or to prove

conclusively its prior discrimination would serve

as an equally open invitation for a suit seeking

back pay in addition to injunctive relief by white

workers. If whenever undertaking affirmative

action employers were confronted with monetary

liability to one group of workers or the other,

- 32

The "high tightrope" that employers are

required to walk by the Fifth Circuit's standard

is illustrated by Kaiser's experience with

VTI suits at its three plants in Louisiana

Baton Rouge, Chalmette and Grammercy.

Black workers at both the Chalmette and the Baton

Rouge plants brought lawsuits alleging Title VII

violations. In the Chalmette suit, the Fifth

Circuit reversed the district court's dismissal of

the complaint because it found on facts remarkably

similar to those at the Grammercy plant that a

prima facie violation of Title VII had been

established. Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corp_. , 575 F . 2d 1374, 1389-90 ( 1978). In the

13/ Cont ' d

employers would refrain from ever taking affirma

tive action.

"Indeed, the requirement of a judicial

determination of a constitutional or statutory

violation as a predicate for race-conscious reme

dial actions would be self-defeating. Such

a requirement would severely undermine efforts to

achieve voluntary compliance with the requirements

of law." Bakke, supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 818 (Bren

nan^ White, Marshall, Blackmun, JJ.); see McDaniel

v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971).

- 33

Baton Rouge suit, the parties, after lengthy

14/litigation and discovery procedures,— entered

into a settlement which provided that Kaiser pay

$255,000 in monetary relief to the plaintiff class

and an additional amount in attorneys' fees.

Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., Civil

Action No.67-86 (M.D. La.) (consent decree filed

Feb. 24, 1975). Kaiser's experience with the

Title VII suits brought by black workers in its

plants in Louisiana and its review of suits

brought against other companies acted — as in

tended by this Court in Albemarle Paper — as a

"spur or catalyst" for change In the third

plant, at Grammercy, where Kaiser adopted an af

firmative action plan designed to remedy possible

prior violations and to forestall a lawsuit

brought on behalf of black workers, see Section

IIIA, infra, it was subjected to this lawsuit by

14/ See, e.g., Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum and

Chemical Corp., 408 F.2d 339 (5th Cir. 1969) (per

curiam), rev1g 287 F.Supp. 289 (E.D. La. 1968).

15/ The superintendent for industrial relations

at the Grammercy plant noted that "the OFCC, the

EEOC, the NAACP, the Legal Defense Fund [had all]

been into the [Baton Rouge] plant, and as I was

saying, whatever their remedy is believe me, it's

one heck of a lot worse than something we can work

out ourselves." A. 83-84, see p.58 n.26, infra.

- 34 -

Brian Weber alleging reverse discrimination. The

Fifth Circuit's rigid standard, requiring conclu

sive proof or an admission of prior discriminatory

practices, would not only result in less voluntary

compliance but would also result — as indicated

by Kaiser's experience in Louisiana — in the

filling of the court dockets with Title VII ] £ /

suits.— See G. Pet. 32a (Wisdom, J., dissenting).

Race-conscious affirmative action is justi

fiable if an employer or a union has a reasonable

basis for believing that it might otherwise be

16/ There was a "staggering" increase in the

number of Title VII cases filed between 1970 and

1976: from 344 employment cases filed in fiscal

year 1 970 to 5,321 in fiscal year 1976. Adminis

trative Office of the United States Courts,

1976 Annual Report of the Director, at 107-08.

This increase is understandable in light of the

facts that the coverage of Title VII was broadly

expanded by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, see e.g., Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S.

840 , 841 (19 7 6), and that the interpretation of

Title VII on numerous issues was first clarified

during this period. See e.g, Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v . Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973); Albemarle

Paper Co. v . Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

- 35

held in violation of Title VII. An affirmative

action plan may be used to remedy the effects of

possible prior discriminatory practices or to

prevent possible continuing discriminatory

16/ cont 'd

This enormous growth rate in Title VII

filings slowed after fiscal year 1976. While there

was an increase of 1,390 filings or of 35.4% from

FY 1975 to FY 1976 (3, 931 filings as compared

to 5,321 filings), in FY 1977 there was an in

crease of 610 filings or of 11% to 5,931. Admin

istrative Office of the United States Courts, 1977

Annual Report of the Director, at 112. In FY 1978

there was a decrease of 427 filings or of 7%

(from 5,931 to 5,504 filings). Administrative

Office of the United States Courts, 1978 Annual

Report of the Director, at 88.

While it is difficult to draw hard conclu -

sions from the dramatic change in the rate

of Title VII case filings from a "staggering"

increase to a decrease, it may be inferred that

the clarifications in the law and the emphasis on

voluntary affirmative action were beginning to

have an effect. If voluntary affirmative action

is severely restricted — as it would be if the

Fifth Circuit is affirmed — then the remedy for

employment discrimination would lie primarily in

the courts and not in voluntary resolution, and a

return to a substantial increasing rate of Title

VII cases could be expected.

- 36

practices.— ̂ This Court has held that a statis

tical disparity resulting from a facially neutral

practice is sufficient to establish a prima facie

disparate impact violation of Title VII, Dothard

v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S, 321 , 329 (1977); and that

gross statistical disparities alone may be suffi

cient to constitute a prima facie showing of

intentional discrimination, Hazelwood School

District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299, 307-08

(1977); International Brotherhood of Teamsters v .

United States, 431 U.S. 324, 339 (1977). Accord-

17/ "If the self analysis shows that one or more

employment practices: (1) have or tend to have an

adverse effect on employment opportunities of

members of previously excluded groups, or groups

whose employment or promotional opportunities have

been artificially limited, (2) leave uncorrected

the effects of prior discrimination, or (3) result

in disparate treatment, the person making the

self-analysis has a reasonable basis for conclud

ing that action is appropriate. It is not neces

sary that the self-analysis establish a violation

of Title VII. This reasonable basis exists

without any admission or formal finding that the

person has violated Title VII, and without regard

to whether there exist arguable defenses to a

Title VII action." EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative

Action, 29 C.F.R. §1608.4(b); see also §1608.3(b).

- 37

ingly, employers and unions may rely on statisti

cal analysis in determining whether there is a

18/reasonable basis for taking affirmative action.—

Where, as in this case, the statistical analysis

indicates a prima facie showing that the employ

er's prior practices were discriminatory and that,

if the employer did not take race-conscious

affirmative action, its continuing practices would

be discriminatory, see pp. 82-85, infra, the

employer had a reasonable basis for taking such

action.

But the analysis need not demonstrate

that there is a prima facie case in order for

race-conscious action to be justifiable. Requir

ing an employer to demonstrate a prima facie

case would frustrate voluntary compliance and the

effective implementation of private remedies for

discriminatory practices for the same reasons,

although not quite as severely, as requiring the

employer to admit that it had engaged in dis-

18/ "The effects of prior discriminatory prac

tices can be initially identified by a comparison

between the employer's workforce, or a part

thereof, and an appropriate segment of the labor

force." EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative Action,

29 C.F.R. §1608.3(b). See also §§1608.3(a),

1608.4(a).

- 38

. . . 19/criminatory practices.-- In order to justify

race-conscious affirmative action an employer need

only show that it had a reasonable basis for

believing that, in the absence of such action,

it might be held in violation of Title VII.

Furthermore, an employer or union may

take race-conscious action to remedy the disad

vantages affecting minorities as a result of

the discriminatory practices of other companies or

unions or as a result of governmental or societal

. . 2 0 /discrimination.— Such action is particularly

19/ Neither Kaiser nor the Steelworkers argued in

the district court that there was a prima facie

case of discrimination even though it is apparent

that such an argument was readily available, see

pp. 56-58, infra. In fact, the parties did not

introduce important but available evidence which

would have confirmed the prima facie showing, see

p. 58 n.26, infra. The reason for the omission

is obvious: by proving or almost proving prior

discrimination, the parties would invite a suit

brought on behalf of black workers which would

involve the parties in the complex litigation

which they had sought to avoid by agreeing to the

affirmative action plan.

20/ "Although Title VII clearly does not require

employers to take action to remedy the disad

vantages imposed upon racial minorities by hands

- 39

necessary where, as is the case with skilled

craftsmen, see pp. 88-105, infra, there is a

limited pool of available minorities because of a

history of discrimination by employers, by unions,

by educational institutions and even by law. See

EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative Action, 29 C.F.R.

§1608.3(c). If the pervasive, complex, and

systemic discriminatory practices in this country

— and their socially dangerous effects, such as

the disproportionate unemployment rate among

minorities — are ever to be undone, employers

must be encouraged to undertake socially respons

ible affirmative action. See Bakke, supra, 57

L.Ed.2d at 844-45 (Blackmun, J.).

It is almost inevitably the case that employ

ers like Kaiser become part and parcel of the

general practices of discrimination. When Kaiser

selected from a pool of skilled craftsmen to

which minorities had limited access because of

discriminatory business, union, and vocational

20/ Cont 'd

other than their own, such an objective is per

fectly consistent with the remedial goals of the

statute." Bakke, supra, 57 L.Ed.2d at 804 n.17

(opinion of Brennan, Marshall, White, Black

mun , JJ.).

- 40 -

training practices, it relied on and, in effect,

supported the discriminatory practices of others.

Reliance on the discriminatory policies of others

which has an adverse impact on minorities, whether

done intentionally or simply without sufficient

business justification, may constitute a violation

2 1 /of Title VII.-- At the very least, a company

which has relied on the discriminatory practices

of others should be encouraged to take action

which would effectively eliminate that reliance

and correct the adverse racial effects caused by

those practices.

21/ See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra,

401 U.S. at 430 ("Because they are Negroes,

petitioners have long received inferior education

in segregated schools---" The petitioners' Title

VII rights were violated because the company

instituted education and testing requirements

which were not job-related and which failed blacks

more frequently than whites as a result of the

discrimination in education); Bakke, supra, 57

L.Ea. 2d at 819 ("[0]ur cases under Title VII ...

have held that, in order to achieve minority

participation in previously segregated areas of

public life, Congress may require or authorize

preferential treatment for those likely disad

vantaged by societal racial discrimination.")

(Opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall, Blackmun,

JJ. ).

- 41

Finally, an employer which is a qualifying

government contractor may, and indeed must,

undertake affirmative action to comply with the

requirements of Executive Order No. 11,246.

In enacting the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, Congress specifically considered and

rejected efforts to outlaw the use of numerical,

race-conscious plans under the Executive Order

program. See Section IC, supra ; Comment, The

Philadelphia Plan, supra, 39 U. Chi. L. Rev. at

751-57. Race-conscious action which is undertaken

in good faith reliance on the Executive Order is

not only permissible under Title VII but furthers

the purposes of Title VII. EEOC Guidelines on

Affirmative Action, 29 C.F.R. §1608.5.— '1

B. An Action to Enforce the Fifth

Circuit's Construction of Title

VII Would not Present a "Case

or Controversy"

The court of appeals held, and respondent

apparently agrees, that the Company and Union

22/ Regardless of the justification for race-con

scious affirmative action, the measures undertaken

must be appropriately designed to remedy the

identified problems. The standards for determining

appropriate action are discussed in Section III B,

infra.

- 42

could have successfully defended this action if

they had alleged and proved that they had dis

criminated on the basis of race against black

employees or applicants. The defendants made no

effort to present this defense; on the contrary,

they claimed that they had not discriminated

against blacks. The evidence adduced by the

defendants on this issue was apparently intended

to show the absence of past discrimination against

blacks, and thus supported the claims and inter

ests of the plaintiff rather than of the defen

dants themselves. The defendants were in posses

sion of a variety of evidence showing past

discrimination against blacks, including the OFCC

letter described in n. 42, infra, but they failed

to introduce the evidence into the record.

Although the scanty evidence that was placed in

the record strongly suggested a history of dis

crimination against blacks, counsel for the

defendants consistently declined to press such an

inference or to urge such a defense. Despite this

peculiar state of affairs, the courts below

attempted to make a factual finding as to whether

or not there had been such a history of discrimi

nation.

- 43

What occurred in this instance is not unique,

but seems an inherent difficulty with cases of

this sort. As the Company candidly notes, no

employer "can be expected to confess to past

discrimination in order to justify a challenged

racial preference." Petition, No. 78-435,

p. 11. Such a confession would give rise to

potentially massive liability to black employees

and applicants for back pay and/or punitive

damages. See pp. 31-34,. supra. No employer will

seek to prove liability to a large number of

minorities or women merely to avoid liability to a

white male. The same dilemma exists outside of

the employment area.

An action which can only be fully defended

by establishing liability to third parties, and

which as a consequence will not be so defended,

does not present a "case or controversy" within

the meaning of Article III. The parties to a

proceeding in federal court must have "such

a personal stake in the outcome of the controversy

as to assure that concrete adverseness which

sharpens the presentation of issues upon which the

court so largely depends . . . Baker v. Carr,

- 44 -

369 U.S. 186, 204 (1962). The nature of the

interests of each party should assure that they

will "frame the relevant questions with specifi

city, contest the issues with the necessary

adverseness, and pursue the litigation vigorously."

Barlow v. Collins, 397 U.S. 159, 172 ( 1970)

(Brennan, J., concurring). The courts are un

equipped, in the absence of such competing inter

ests, to resolve factual questions which usually

require discovery and a contested evidentiary

hearing. These considerations are of particular

import where, as here, upholding plaintiff's

undefended claim of non-discrimination would

adversely affect the interests of third parties,

the black workers.

Previous standing decisions have focused on

whether the plaintiff has a "sufficient stake in

an otherwise justiciable controversy to obtain

judicial resolution Sierra Club v. Morton,

405 U.S. 727, 731 (1972). That requirement is as

applicable to a defendant as it is to a plaintiff,

for the necessary vigorous contest of issues

requires two competing parties. This Court has

- 45

repeatedly held that a party lacks standing to

litigate an issue if success in the litigation will

not accrue to its benefit. Simon v. Eastern

Kentucky Welfare Rights Org., 426 U.S. 26 (1976);

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975). A fortiori

the required interest is lacking where success in

the litigation will operate to the disadvantage of

the "prevailing" party. Even where the plaintiff

himself has standing to bring an action, it must be

brought against a party with standing to defend

it.

An adversary relationship does exist between

the parties to this case as to the ultimate

outcome — whether the defendants can continue

their affirmative action program. But the purpose