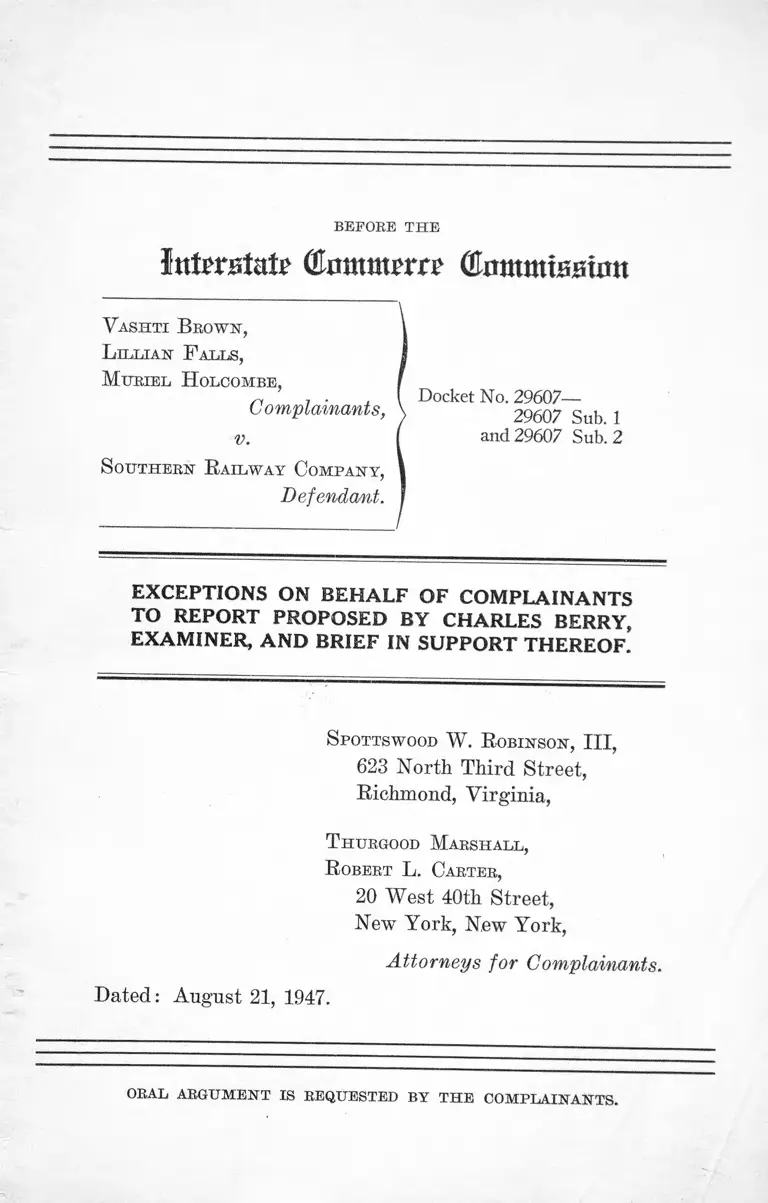

Brown v Southern Railway Company Exceptions on Behalf of Complaints to Report and Brief in Support Thereof

Public Court Documents

August 21, 1947

68 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v Southern Railway Company Exceptions on Behalf of Complaints to Report and Brief in Support Thereof, 1947. 124d20f4-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/25c4a9eb-9900-4d99-a2a8-3610dda2cfe4/brown-v-southern-railway-company-exceptions-on-behalf-of-complaints-to-report-and-brief-in-support-thereof. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

BEFORE T H E

Interstate Cmmnrrrr Olnmmtsatnn

V ashti Brown,

L illian F alls,

M uriel H olcombe,

Complainants,

v.

S outhern R ailway Company,

Defendant.

Docket No. 29607—

29607 Sub. 1

and 29607 Sub. 2

EXCEPTIONS ON BEHALF OF COMPLAINANTS

TO REPORT PROPOSED BY CHARLES BERRY,

EXAMINER, AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOF.

Spottswood W. R obinson, III,

623 North Third Street,

Richmond, Virginia,

T hurgood Marshall,

R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Complainants.

Dated: August 21, 1947.

ORAL ARGUMENT IS REQUESTED BY THE COMPLAINANTS.

I N D E X

PAGE

Exceptions on behalf of complainants___________ 1

Brief in support of exceptions ____ ____________ 3

I. State Statutes Requiring the Separation

of the Races Cannot Justify Defendant’s

Action _______________________ 3

II. Defendant Is Without Authority to Adopt

Or Enforce a Rule Or Regulation Segre

gating Its Passengers on the Basis of Race 7

III. The Regulation Proposed By the Exam

iner, If Adopted By Defendant, Would Be

Unreasonable _____ 14

IV. The Facilities Afforded Colored Passen

gers in Car S-l Were Not Equal to the

Facilities Afforded White Passengers in

Car S-6 __________________________ 19

V. Defendant Has Violated Sections One and

Two of the Interstate Commerce A c t____ 21

Conclusion ____________________________________ 23

11

. Table of Cases.

Adelle v. Beaugard, 1 Mart. 183________________ 12

Britton v. Atlantic & C. A. L. Ry. Co., 88 N. C.

536 (1883) ___‘______________ ________________ 14

Brumfield v. Consolidated Coach Corp., 240 Ky. 1,

40 8. W. (2d) 356 (1931) ___________________ ... 14

Chesapeake & 0. Ry. Co. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S.

388 (1900) _____..._____ ___________________ 5

Chicago, R. I. & Co. Ry. Co. v. Carroll, 108 Tex.

378, 193 S. W. 1068 (1917) ___________________( 9

Chicago, R. I. & P. Ry. Co. v. Allison, 120 Ark. 54,

178 S-, W. 401 (1915) _________:____ _______ _ 13

Chiles v. Chesapeake & O. Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71

(1910) ____ ._____________ ___________________ 5

Chiles v. Chesapeake & O. Ry. Co., 125 Ky. 299,

101 S. W. 386 (1907) _________________________ 5

DeBeard v. Camden Interstate Ry. Co., 62 W. Va.

41, 57 8. E. 279 (1907) ________ ______________ 9

Dunn v. Grand Trunk Ry. Co., 58 Me. 187 (1870) 9

Edwards v. Nashville, C. & St. L. Ry., 12 I. C. C.

247 (1907) _____________ ___________________ ... 16

Georgia R. & B. Co. v. Murden, 86 Ga. 434, 12 S. E.

630 (1890) ____________ __ ___ _____________ ___ 9

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485 (1877) _____________ 4

Hart v. State, 100 Md. 596, 60 A. 457 (1905) ____ 5

Hickman v. International Ry. Co., 97 Misc. 53, 160

N. Y. S. 994 (1916) _________ __________________ 9

Hufford v. Grand Rapids & I. R. Co., 64 Mich. 631,

31 N. W. 544 (1887) ___ ...______________________ 9

Lake Shore & M. S. R. Co. v. Brown, 123 111. 162,

14 N. E. 197 (1887) _______________________ _ 9

Lee v. New Orleans G. N. Ry., 125 La. 236, 51 S.

182 (1910)

PAGE

12

Ill

Louisville, N. O. & T. By. Co. v. Mississippi, 133

U. S. 587 (1890) ____________________________ 5

Louisville, N. 0. & T. By. Co. v. State, 66 Miss.

662, 6 So. 203 (1889) _______ ________________ 5

Louisville & N. B. Co. v. Biteliell, 148 Kv. 701, 147

S. W. 411 (1912) ____________________________ 13

Louisville & N. B. Co. v. Turner, 100 Tenn. 213, 47

S. W. 223 (1898) _____________________________ 9

Mathews v. Southern B. Co., 157 F. (2d) 609 (App.

D. C. 1946) _____________________.:.____________ 7

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe By. Co.,

186 Fed. 966 (C. C. A. 8th, 1911)______________ 5

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe By. Co.,

235 U. S. 151 (1914) ______...__________________ 5

McGowan v. New York City By. Co., 99 N. Y. S.

835 (1906) _____________________ _____________ 9

Missouri K & T By. Co. of Texas v. Ball, 25 Tex.

Civ. App. 500, 61 S. W. 327 (1901) ___________ 13

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 IJ. S. 373 (1946) _______ 11

Ohio Valley By. ’s Beceiver v. Lander, 104 Ky. 431,

47 S. W. 344 (1898) __________________________ 5

O ’Leary v. Illinois Central B. Co., 110 Miss. 46,

69 So. 713 (1915) ____________________________ 5

People ex rel. Bibb v. Alton, 193 111. 301, 61 N. E.

1077 (1901) _________________________________ 19

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896)____ ...___ 18

Benaud v. New York, N. H. & H. B. Co., 219 Mass.

553, 97 N. E. 98 (1912)_______________________ 9

South Covington & C. By. Co. v. Commonwealth,

181 Ky. 449, 205 S. W. 603 (1918)_____________ 5

South Covington & C. St. By. v. Kentucky, 252

U. S. 399 (1920) __________ 16

Southern Kansas By. Co. v. State, 44 Tex. Civ.

App. 218, 99 S. W. 166 (1906) _______________ 5,16

Southern Pacific B. Co. v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761

(1945)

PAGE

2

IV

State ex rel. Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770,

11 So. 74 (1892) __________1__________________ 5

State v. Galveston, H. & S. A. Ry. Co. (Tex. Civ.

App.) 184 S. W. 227 (1916).____________ ______ 5

State v. Jenkins, 124 Md. 376, 92 A. 773 (1914) 5

State v. Treadaway, 126 La. 300, 52 So. 500______ 12

Union Traction Co. v. Smith, 70 Ind. App. 40, 123

N. E. 4 (1919) _______________________________ 9

Virginia Elec. & P. Co. v. Wynne, 149 Va. 882, 141

S. E. 829 (1928) _____________________________ 9

Washington, B. & A. Elec. Ry. Co. v. Waller, 53

App. D. C. 200, 289 Fed. 598 (1923)________5,9,14

Westminster School District et al. v. Mendez, — F.

(2d) — (C. C. A. 9th, 1947) __________________ 19

Statutes.

Alabama

Title 1, Sec. 2, Ala. Code of 1940____________ 12

Title 14, Sec. 360, Ala. Code of 1940_________ 12

Georgia

Ga. Laws, 1927, p. 272______________________L 12

Gg. Code (Michie Supp.) 1928___________ ___ 12

Louisiana

La. Acts, 1910, No. 206_____________________ 12

La. Crim. Code (Dart), 1932, Art. 1128-1130__ 12

North Carolina

N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943, Sec. 51-3 and 14-181____ 12

N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943, Sec. 115-2____________ 12

South Carolina

S. C. Const., Art. I ll, Sec. 33_______________ 12

Virginia

Va. Code (Michie) 1942, Sec. 67____________ 12

PAGE

V

Other Authorities.

PAGE

Noel T. Dowling, Interstate Commerce and State

Power, 47 Col. L. Rev. 547____________________ 11

Gnnnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma (N. Y.

1944), pp. 580-581 ____________________________ 17

Charles Johnson, Patterns of Segregation (1943),

pp. 4, 318 ___________________________________ 17

BEFORE THE

Interstate ©mnmerre CnmnttSHtnn

V ashti B rown,

L illian F arls,

M uriel H olcombe,

Complainants,

v.

S outhern R ailway Company,

Defendant.

EXCEPTIONS ON BEHALF OF COMPLAINANTS

TO REPORT PROPOSED BY CHARLES BERRY,

EXAMINER, AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOF.

Comes now the complainants, Vashti Brown, Lillian

Falls and Muriel Holcombe, in the above-entitled pro

ceedings and in the following particulars take issue

with and except to the findings and conclusions in the

report proposed by Charles Berry, Examiner.

Docket No. 29607—

29607 Sub. 1

and 29607 Sub. 2

I.

Complainants except to finding No. 1 of the proposed

report (Page 1, Paragraph 1) which states:

“ Accommodations furnished in the car set aside

for occupancy by Negro passengers found to be

substantially equal to those provided in car set

apart for occupancy by wThite passengers.”

for the reason that complainants have shown in detail

in their testimony that the accommodations in car S-l

maintained for Negroes were substantially inferior in

many respects to the accommodations in car 8-6 main

tained for whites.

2

II.

Complainants except to finding No. 2 of the proposed

report (Page 1, Paragraph 2) which states:

“ Maintenance and enforcement by a common

carrier by railroad of a reasonable rule or regu

lation requiring segregation of Negro and white

passengers, provided substantially equal ac

commodations are furnished, found not to be a

violation of the Interstate Commerce Act.”

for the reason that such a rule or regulation must in

essence be unreasonable and for the further reason

that a carrier is without authority to promulgate or

enforce such a regulation.

III.

Complainants except to finding No. 4 of the proposed

report (Page 1, Paragraph 4) which states:

‘ ‘ It is, and for the future will be, unduly preju

dicial and preferential for the Southern Rail

way Company to set apart separate accommo

dations for the exclusive occupancy of white

and Negro passengers on ‘ The Southerner’

running from New York to Atlanta and to re

quire the respective races to occupy the space

assigned to them, unless the rules and regula

tions governing* and requiring such separation

of the races are definite and specific and are

published in its tariffs posted in stations from,

to, and through which the trains run, or in some

other manner made available to passengers at

the time or before they purchase tickets.”

for the reason that a regulation adopted by defendant

to enforce the racial separation of its passengers, must

of necessity be prejudicial and discriminatory. Fur

ther, defendant is without power to burden interstate

passenger travel with a regulation designed to enforce

racial segregation.

3

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF EXCEPTIONS.

I.

State Statutes Requiring the Separation of the

Races Cannot Justify Defendant’s Action.

Complainants secured reserved seat accommodations

on defendant’s train #47, the Southerner, for a trip

from New York City to Atlanta, Georgia, on January

7, 1945. The Southerner is a modern, streamlined,

diesel powered, reserved seat, coach train operating

daily between New York and New Orleans. Com

plainants purchased their tickets at the Pennsylvania

Station in New York and secured reservations en

titling them to space designated as seats 52, 53 and 54

in car S-6 on defendant’s train #47. On January 7,

1945, complainants boarded the train in New York and

occupied their designated space in car S-6 without

question or protest from any train official. At about

11:20 P. M. that night when the train was south of

Washington, D. C., and in the vicinity of Charlottes

ville, Virginia, they were informed by the conductor,

W. B. McKinney, and the passenger representative, G.

F. Lovett, both agents and employees of defendant,

that they could no longer remain in car S-6 but would

have to move to car S-l. The reasons given were that

Negroes had to be segregated south of Washington and

that since the train was then in Virginia, its laws had

to be obeyed. Complainants pointed out that they

were interstate passengers and that they held reserved

seats which they were entitled to occupy until they

reached their destination. The conductor and pas

senger agent, however, continued to insist that com

4

plainants move and finally threatened to eject them at

the next stop unless they did so, whereupon complain

ants under protest moved to car S-l (R. 9-18).

The statutes of Virginia requiring the separation of

the races on railroad carriers cannot affect the merits

of the instant controversy. Such statutes have been

held to be inapplicable to interstate commerce since

the decision of the United States Supreme Court in

Hall v. DeCuir.1 In that case a Louisiana statute guar

anteeing equal rights and privileges to all persons

without regard to race or color in the use and enjoy

ment of public facilities was declared invalid as ap

plied to interstate commerce. The fundamental ob

jection to such statutes was the danger that differing

and conflicting notions of racial policy would create

confusion and would burden interstate commerce in a

manner which the commerce clause was intended to

avoid.

In Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona,2 the Court, faced

with a related problem, defined the authority of the

states and the nation over interstate commerce in this

manner:

“ Although the commerce clause conferred on the

national government power to regulate commerce,

its possession of the power does not exclude all

state power of regulation. ” * * *

“ But ever since Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat.

(U. S.) 1, 6 L. ed. 23, the states have not been

deemed to have authority to impede substantially

the free flow of commerce from state to state, or

to regulate those phases of the national commerce

195 U. S. 485 (1877).

2325 U. S. 761 (1945).

a

which, because of the need of national uniformity,

demand that their regulation, if any, be prescribed

by a single authority. * * * Whether or not this

long recognized distribution of power between the

national and the state governments is predicated

upon the implications of the commerce clause it

self * * * or upon the presumed intention of Con

gress, where Congress has not spoken, * * * the

result is the same. ” # * *

“ Similarly the commerce clause has been held to

invalidate local ‘ police power’ enactments

regulating the segregation of colored passengers

in interstate trains, Hall v. DeCuir. * * *”

Although the principle announced in Hall v. DeCuir

has become the all but universal rule of American

courts,8 no decision of the United States Supreme

Court had nullified a state statute requiring the segre

gation of the races as an unconstitutional burden on

interstate commerce until its decision on June 3, 1946

in Morgan v. Virginia.4 In that case Mrs. Morgan was

s Chesapeake & 0 . Ry. Co. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S. 388

(1900); Chiles v. Chesapeake & 0 . Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71

(1910) ; McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Ry. Co.,

235 U . ' S. 151 (1914); Louisville, N. 0 . & T. Ry. Co. v.

Mississippi, 133 U. S. 587 (1890) ; Washington, B. & A. Elec.

R. Co. v. Walter, 53 App. D. C. 200, 289 Fed. 598 (1923);

South Covington & C. Ry. Co. v. Commonwealth, 181 Ky. 449,

205 S. W . 603 (1918); McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ry.

Co. 186 Fed. 966 (C. C. A. 8th, 1911); State v. Galveston,

H. & S. A. Ry. Co. (Tex. Civ. App.), 184 S. W . 227 (1916) ;

O’Leary v. Illinois Central R. Co., 110 Miss. 46, 69 S. 713

(1915) ; State v. Jenkins, 124 Md. 376, 92 A. 773 (1914) ;

Chiles v. Chesapeake & O. Ry. Co., 125 Ky. 299, 101 S. W .

386 (1907) ; Southern Kansas Ry. of Tex. v. State, 44 Tex.

Civ. App. 218, 99 S. W . 166 (1906) ; Hart v. State, 100 Md.

596, 60 A. 457 (1905) ; Ohio Valley Ry.’s Receiver v. Lander,

104’Ky. 431, 47 S. W . 344 (1898); Louisville, N. O. & T. Ry.

Co. v. State, 66 Miss. 662, 6 S. 203 (1889) ; State ex rel.

Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770, 11 S. 74 (1892).

4 328 U. S. 373 (1946).

6

convicted for violating a state statute requiring the

segregation of the races when she had refused to move

to the rear seat of a bus travelling in interstate com

merce between Saluda, Virginia, and Baltimore, Mary

land. This conviction was sustained by the Virginia

Supreme Court of Appeals as a valid exercise of the

state’s police power. On appeal, the United States

Supreme Court reversed. Said the Court:

# # # * # * * * *

“ Burdens upon commerce are those actions of a

state which directly ‘ impair the usefulness of its

facilities for such traffic.’ That, impairment, we

think, may arise from other causes than costs or

long delays. A burden may arise from a state

statute which requires interstate passengers to

order their movements on the vehicle in accord

ance with local rather than national require

ments.” # # *

“ The interferences to interstate commerce which

arise from state regulation of racial association

on interstate vehicles has long been recognized.

Such regulation hampers freedom of choice in

selecting accommodations. The recent changes in

transportation brought about by the coming of

automobiles does not seem of great significance

in the problem. People of all races travel today

more extensively than in 1878 when this Court

first passed upon state regulation of racial segre

gation in commerce. The factual situation set out

in preceding paragraphs emphasizes the sound

ness of this Court’s early conclusion in Hall v.

DeCuir, * * * ”

There is little doubt that, although the Morgan

decision involved bus transportation, the same rule

7

applies to any other type of interstate transportation.5

It is certain, therefore, that state statutes cannot he

used as justification, excuse or defense of defendant’s

action in forcing the removal of complainants from

their reserved space in car 8-6. The conductor and

passenger agent in basing their action on the require

ment of Virginia law subjected complainants to an

unwarranted and illegal invasion of their constitu

tional rights. Since defendants had no private rules

or regulations in effect authorizing the action of their

agents, and the examiner’s report so finds,* * 8 the wrongs

herein complained of have been definitely and con

clusively established. Without more, therefore, com

plainants are entitled to the relief sought in their

complaints.

II.

Defendant is Without Authority to Adopt or

Enforce a Rule or Regulation Segregating Its

Passengers on the Basis of Race.

1.

The examiner’s proposed report, while finding that

defendant presently has no private rule or regulation

requiring the segregation of Negro and white passen

gers, suggests that such a rule or regulation if “ defi

nite and specific and properly posted so as to be avail

able to passengers and prospective passengers at the

5 See Mathews v. Southern Railroad Co., 157 F. (2d) 609

(App. D. C. 1946).

8 See sheet 12 of examiner’s report.

8

time or before they purchase their tickets,” provided

equal conditions and treatment are furnished would

satisfy the requirement of the Interstate Commerce

Act. The report cites Hall v. DeCuir and Chiles v.

Chesapeake & 0. By. Co.7 as authority for the con

tention that a common carrier has power to “ adopt

reasonable rules and regulations for the separation

of Negro and white passengers as seems to it to the

best interests of all concerned, and that the test of

reasonableness is the established usages, customs and

traditions of the people carried by it, the promotion

of their comfort and the preservation of the public

peace and good order.” Continuing, the report cites

the practice of other railroads in the South in main

taining separate accommodations for Negro and white

passengers and as evidence of the reasonableness and

validity of such practices the segregation statutes of

Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

“ Legislatures are supposed to know the needs and

sentiments of the people for whom they act.” 8 This

phase of the proposed report, we contend, is errone

ous.

Only if defendant could be said to have authority

to adopt rules and regulations requiring the segre

gation of the races, could the examiner’s conclusion

that such a regulation properly posted and publicized

would be a complete defense for the future be a cor

7218 U. S. 71 (1910).

8 See sheets 11-12 of examiner’s report.

9

rect statement of the law.9 * * * * 14 The issue then is whether

the defendant has authority to segregate the races

under a future rule or regulation. We contend that

no such authority exists.

If the examiner ’s contentions are correct, then states

which are clearly without authority to effect such

separation in interstate commerce by means of state

law are now permitted to enforce such policy through

carrier regulations. The question of the separation

of the races in interstate commerce was settled by the

United States Supreme Court in Morgan v. Virginia.

In reaching its conclusion that the Virginia statute

was an unconstitutional burden on commerce, the

Court was neither unaware nor unmindful of local cus

toms, usages and traditions which purportedly justify

a policy of segregation.

“ In weighing the factors that enter into our con

clusion as to whether this statute so burdens in

terstate commerce or so infringes the require

ments of national uniformity as to be invalid, we

are mindful of the fact that conditions vary be

tween northern or western states such as Maine

9 See Union Traction Co. v. Smith, 70 Ind. App. 40, 123

N. E. 4 (1919); Renaud v. New York, N. H. & H. R. Co.,

210 Mass. 553, 97 N. E: 98 (1912) ; Louisville & N. R. Co. v.

Turner, 100 Tenn. 213, 47 S. W . 223 (1898) ; Washington,

B. & A. Elec. Ry. Co. v. Waller, 53 App. D. C. 200, 289 Fed.

598 (1923) ; Virginia Elec. & P. Co. v. Wynne, 149 Va. 882,

141 S. E. 829 (1928) ; DeBeard v. Camden Interstate Ry. Co.,

62 W . Va. 41, 57 S. E. 279 (1907) ; Chicago, R. I. & Co. Ry.

Co. v. Carroll, 108 Tex. 378, 193 S. W .1068 (1917) ; Hickman

v. International Ry. Co., 97 Misc. 53, 160 N. Y. S. 994 (1916) ;

McGowan v. New York City Ry. Co., 99 N. Y. S. 835 (1906);

Georgia R. & B. Co. v. Murden, 86 Ga. 434, 12 S. E. 630

(1890); Lake Shore & M. S. R. Co. v. Brown, 123 111. 162,

14 N. E. 197 (1887) ; Hufford v. Grand Rapids & I. R. Co.,

64 Mich. 631, 31 N. W. 544 (1887) ; Dunn v. Grand Trunk

Ry. Co., 58 Me. 187 (1870).

or Montana, with practically no colored popula

tion; industrial states such as Illinois, Ohio, New

Jersey and Pennsylvania with a small, although

appreciable, percentage of colored citizens; and

the states of the deep south with percentages of

from twenty-five to nearly fifty per cent colored,

all with varying densities of the white and colored

races in certain localities. Local efforts to pro

mote amicable relations in difficult areas by legis

lative segregation in interstate transportation

emerge from the latter racial distribution. As no

state law can reach beyond its own border nor bar

transportation of passengers across its bounda

ries, diverse seating requirements for the races in

interstate journeys result. As there is no federal

act dealing with the separation of races in inter

state transportation, we must decide the validity

of this Virginia statute on the challenge that it

interferes with commerce, as a matter of balance

between the exercise of the local police power and

the need for national uniformity in the regulations

for interstate travel. It seems clear to us that

seating arrangements for the different races in

interstate motor travel require a single, uniform

rule to promote and protect national travel. Con

sequently, we hold the Virginia statute in contro

versy invalid.” 10

Yet the Court in balancing local and national inter

est's concluded that in regard to this subject matter

there was a definite necessity for a national uniform

policy. The silence of Congress, therefore, was not

construed as a negative assent to state regulation but

rather as an implied declaration that the matter be

free of control. If this proposed report is adopted,

however, the effect of the Morgan decision will be 10

t

10

10 328 U. S. at p. 386.

11

nullified. To say that although a state cannot di

rectly require an interstate carrier to segregate its

Negro and white passengers, its statutes requiring

this practice make the regulation of a carrier designed

to accomplish such segregation reasonable and valid

is both illogical and irrational. If, as the Morgan de

cision holds, Congress has exclusive authority to de

termine policy regarding the separation of Negro and

white passengers in interstate commerce, it clearly

follows that neither a state by statute nor a carrier by

regulation can invade this exclusive Congressional

domain.” If this is not true then, as illustrated by the

reasoning in the proposed report, the Morgan decision

is meaningless.

2.

The same factors which influenced the Court in de

claring that the states are without authority to require

the separation of races in interstate commerce are at

work with equal force when the effect of a carrier regu

lation enforcing such segregation is considered. In

the Morgan case the Court found that one of the main

vices of giving effect to local statutes enforcing segre

gation in interstate commerce was the difficulty of iden

tification.13 That difficulty is no less when the separa

tion is attempted by a carrier regulation rather than

a state statute. 11 12

11 It may well be that the states or carriers, with the affirma

tive assent of Congress, may be permitted to impose on inter

state commerce the regulations voided under the Morgan deci

sion. It is not clear whether the regulation of the seating ar

rangement of passengers is a subject from which the states are

barred by the commerce clause itself or because of the absence

of positive assent of Congress. See Southern Pacific Co. v.

Arizona, supra; Dowling, Interstate Commerce and State

Power, 47 Col. L. Rev. 547.

12 Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 382, 383.

12

Defendant in order to enforce tlie regnlation which

is proposed in the examiner’s report must define what

is meant by the term “ Negro” or “ colored” person.

From the point where they were forced to move from

car S-6 to ear S-l until they reached their destination,

complainants traveled through four states, Virginia,

North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. In Vir

ginia and Georgia, the term “ Negro” or “ colored”

person includes all persons with any ascertainable

amount of Negro blood.13 In North Carolina this term

embraces all persons with Negro blood to the third

generation inclusive,14 whereas in South Carolina 1/8

or more of Negro blood is enough to classify one as a

“ Negro” or “ colored person.” 15

13 Ga. Laws, 1927, p. 272; Ga. Code (Michie Supp.) 1928,

Sec. 2177; Va. Code (Michie) 1942, Sec. 67.

14 N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943, Sec. 51-3 and 14-181 (marriage law)

but see N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943, Sec. 115-2 (separate school law)

for a different definition of the term.

15 S. C. Const., Art. I l l , Sec. 33 (intermarriage). Also in

continuing the trip to New Orleans defendant train passes

through Alabama and Louisiana. In Alabama, any ascertainable

amount of Negro blood is sufficient to make one a Negro, see

Ala. Code, 1940, Tit. 1, Sec. 2, and Tit. 14, Sec. 360. In Louisi

ana, the rule is not clear. It was first held that all persons, in

cluding Indians, who were not white were “ colored” . Adelte v.

Beaugard, 1 Mart. 183. In 1910, it was held that anyone having

an appreciable portion of Negro blood was a member of the

colored race within the meaning of the segregation law. Lee v.

New Orleans G. N. Ry., 125 La. 236, 51 S. 182. In the same

year, however, it was decided that an octoroon was not a mem

ber of the Negro or black race within the meaning of the con

cubinage law (La. Act, 1908, No. 87). State v. Treadaway,

126 La. 300, 52 So. 500. Shortly after the latter decision, the

present concubinage statute was enacted substituting the word

“ colored” for “ Negro” . La. Acts, 1910, No. 206, La. Crim.

Code (Dart), 1932, Art. 1128-1130. The effect of the change

is yet to be determined.

13

In an attempt to enforce the proposed regulation,

defendant would have to adopt the definitions of all

states along the route over which the suggested regu

lation is to operate. If the carrier makes an error of

identification, it will become subject to burdensome liti

gation.16 Hence, it is clear that the proposed regula

tion is as objectionable and as burdensome to com

merce as the Virginia statute voided in the Morgan

case. There is moreover even less reason for giving

effect to a carrier regulation than to a state statute.

None of the factors which are said to give validity to

a legislative judgment which is expressed in segrega

tion laws are operative where carrier regulations are

involved. If defendant fears, as suggested in the ex

aminer’s report, that the co-mingling of Negro and

white passengers will result in breaches of the peace,

there is no reason advanced to show that the states

along defendant’s route are without power to handle

or control such incidents and to protect defendant’s

property. National interests in maintaining commerce

free of burdens and obstructions must prevail over

carrier regulations as well as state statutes. Hence

under the rationale of the Morgan case, it must logi

cally follow that neither a state nor a carrier has

authority to burden interstate commerce by the en

forced segregation of passengers in interstate com

merce.

16 See Louisville & N . R. R. v. Ritchel, 148 Ky. 701, 147

S. W . 411 (1912); Missouri K & T Ry. Co. of Texas v. Ball,

25 Tex. Civ. App. 500, 61 S. W . 327 (1901) ; Chicago, R. I. &

P. Ry. Co. v. Allison, 120 Ark. 54, 178 S. W . 401 (1915),

where punitive damages were afforded white persons for mis

taken placement in colored coaches.

14

III.

The Regulation Proposed By the Examiner, If

Adopted By Defendant, Would Be Unreasonable.

In order for a regulation such as here suggested to

be considered reasonable, it must be shown to have a

direct relation to the efficiency of the carrier’s services,

the comfort, convenience, safety or health of its pas

sengers.17 The proposed regulation is allegedly rea

sonable because in accord with customs and tradi

tions and as essential to the preservation of peace

and good order. As pointed out in the preceding sec

tion of this argument, local enforcement officials have

ample authority to control the behavior of passengers

who utilize defendant’s facilities and to protect its

property so that segregation is not a sine qua non of

peace and order. In fact such practices create dissen-

tion and resentment and are in themselves the breeders

of conflict and racial tensions.

It is true, of course, that defendant’s route traverses

states where racial segregation is enforced. However,

defendant’s road is one of the main arteries connect

ing the North and South. Its facilities are used with

as much frequency by persons whose customs and

traditions are opposed to racial segregation as by

persons of contrary background. Certainly on the

train in question, offering through service between

New York and New Orleans and intermediate points,

it is likely that the greater number of passengers are

17 See Brumfield v. Consolidated Coach Corp., 240 Ky. 1, 40

S. W . (2d) 356 (1931) ; Washington B. & A . Elec. Ry. Co. v.

Waller, 53 App. D. C. 200, 289 Fed. 598 (1923); Britton v.

Atlantic & C. A. L. Ry. Co., 88 N. C. 536 (1883).

15

in the former category. It is admitted that complain

ants’ presence in car S-6 neither had created nor

threatened to create any disturbance or breach of the

peace.

The unreasonableness of a regulation which enforces

the separation of Negroes and whites in coaches on

defendant’s train is conclusively demonstrated by the

fact that no such practice is in effect or deemed neces

sary in defendant’s Pullman cars. If the comfort,

convenience and safety of the passengers and the pub

lic peace require segregation in coaches, it would ap

pear that these same considerations would make seg

regation essential in Pullman cars. And in converse,

if racial separation is neither necessary nor essential

in Pullman cars, it follows that such practices are not

essential in coaches. Neither the alleged comfort

and convenience of passengers, the alleged danger of

breaches of the public peace, nor local sentiment, cus

tom or usage has constrained defendant to adopt a

policy of segregation in its Pullman cars.

On the same train carrying coach and Pullman cars,

defendant requires segregation in the former and per

mits the co-mingling of the races in the latter. This

inconsistency, as noted in the examiner’s report, is

not explained. The truth is that carriers with routes

in the South began practicing segregation in conform

ity to state statutes. In fact, defendant here has no

rule or regulation but has enforced the segregation of

Negro and white passengers in obedience to the laws

16

of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia.18

Although it is definitely a burden to defendant in

added costs and wasted space to maintain the segre

gation of Negro and white passengers in coaches, the

maintenance of separate facilities in Pullman cars ap

parently would be prohibitive.19 Such a practice, how

ever, which adds to the operation costs of defendant

railroad, is not essential to same and is definitely un

necessary as demonstrated by its policy of non-segre

gation in defendant Pullman cars, is clearly unreason

able and should be so declared by this Commission.

The Interstate Commerce Act prohibits discrimina

tion as between white and colored passengers. This

Commission has construed its provisions as prohibit

ing only such discrimination as results in unequal fa

cilities or treatment but not as prohibiting such dis

crimination as results in segregation.20

To say that segregation on a public carrier is not

discrimination is, of course, to close one’s eyes to re

ality. The purpose of segregation is neither to pre

18 The regulation on which defendant relies is Rule 1196 of

its Rules of the Operating Department, effective April 1, 1943.

This rule is for conductors on passenger service and is as

follows:

“ They must as far as possible require passengers to

occupy the cars or space designated for them and not to

occupy places where their safety might be endangered.”

This rule makes no reference to segregation on the basis of race

and supports complainants’ right to remain in the space origi

nally assigned to them in car S-6. See examiner’s report, sheet

12, and pages 58, 59, 91-93 of the Record.

19 See testimony of defendant’s witness, E. E. Barry, at pp.

102-104 in Record; see also South Covington & C. St. Ry. v.

Kentucky, 252 U. S. 399 (1920) ; Southern Kansas Ry. of Tex.

v. State, 44 Tex. Civ. App. 218, 99 S. W . 166 (1906).

20 Edwards v. Nashville, C. & St. L. Ry., 12 I. C. C. 247

(1907).

17

serve the peace nor good order but amounts to a value

judgment indicating the inferiority of Negroes and the

superiority of whites.21 It reinforces a color caste

system which has plagued our democratic concepts

21 See Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma (New York,

1944), pp. S80-S81: “ When the federal Civil Rights Bill of

1875 was declared unconstitutional, the Reconstruction Amend

ments to the Constitution— which provided that Negroes are

* * * * entitled to ‘Equal benefit of all laws’ * * * could not be

so easily disposed of. The Southern whites, therefore, in pass

ing their various segregation laws to legalize social discrimina

tion, had to manufacture a legal fiction of the same type as we

have already met in the preceding discussion on politics and

justice. The legal term for this trick in the social field, expressed

or implied in most of the Jim Crow statutes is ‘separate but

equal’. That is, Negroes were to get equal accommodations, but

separate from the whites. It is evident, however, and rarely

denied, that there is practically no single instance of segregation

in the South which has not been utilized for a significant dis

crimination. The great difference in quality of service for the

two groups in the segregated set-ups for transportation and

education is merely the obvious example of how segregation is

an excuse for discrimination.”

See also Charles S. Johnson, Patterns of Segregation (New

York, 1943), p. 4 : “ It is obvious that the policy of segregation

which the American system of values proposes, merely to sepa

rate and to maintain two distinct but substantially equal worlds,

is a difficult ideal to achieve. Any limitation of free competition

inevitably imposes unequal burdens and confers unequal advan

tages. Thus, segregation or any other distinction that is im

posed from without almost invariably involves some element of

social discrimination as we have defined it.”

p. 318: “ The laws prescribing racial segregation are based

upon the assumption that racial minorities can be segregated

under conditions that are legally valid if not discriminating.

Theoretically, segregation is merely'the separate but equal treat

ment of equals. ' In such a complex and open society as our

own, this is, of course, neither possible nor intended; for whereas

the general principle of social regulation and selection is based

upon individual competition, special group segregation within

the broad social framework must be effected artificially and by

the imposition of arbitrary restraints. The result is that there

can be no group segregation without discrimination, and dis

crimination is neither democratic nor Grristian.”

18

since the birth of this nation. Defendant introduced

testimony to the effect that whites have been required

to move from the Negro car in order to show the equal

application of its practices. However, the enforce

ment of such policy is a humiliation to Negro pas

sengers not because they so construe it but because it

is a fact. The doctrine of “ equal but separate” as

used to sustain a state statute requiring segregation in

intrastate commerce is as fictional and unreal as such a

doctrine when applied to a carrier regulation in inter

state commerce.

“ The arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis

of race, while they are on a public highway, is a

badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the

civil freedom and the equality before the law es

tablished by the Constitution. It cannot be justi

fied on any legal grounds. * * * The thin disguise

of ‘ equal’ accommodations for passengers in rail

road coaches will not mislead anyone or atone for

the wrong done this day.” 22

This statement from Mr. Justice H ablan ’s dissenting

opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson correctly and properly

recognizes that any policy of enforced racial segre

gation in a public carrier is necessarily both discrim

inatory and undemocratic. This Commission is under

a duty to reexamine this whole question, particularly

in the light of the Morgan decision. Reexamination

will reveal the unreasonableness of any practice de

signed to separate the races on the basis of color and

22 Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 561, 562 (1896).

19

will demonstrate that such separation is not essential

to the transportation of persons through the South.23

IV.

The Facilities Afforded Colored Passengers

in Car S-l W ere Not Equal to the Facilities

Afforded White Passengers in Car S-6.

Complainants found from personal observation and

experience during the course of their trip that car S-l

which defendant maintains for the exclusive occupancy

of Negroes was inferior in many respects to car S-6

which was maintained for whites. These discrepancies

were related in detail by complainants at the hearing

of this cause on January 27, 1947, and they are set

out in the record from pages 20-29. Most of this testi

mony is unchallenged and remains undisputed by

defendant.

Whereas the head rests in car S-6 were immaculate,

those in S-l were filthy dirty (R. 20); whereas S-6

was clean and comfortably heated, S-l was dirty and

23 Assuming the legality of a policy of segregation, the pre

vailing view in American courts would appear to be that such

a policy can only be adopted by legislative action, and in the

absence of such action cannot be done by an administrative

board. Westminster School District v. Mendez, — F. (2d) —-

(C. C. A. 9th, 1947); People ex rel. Bibb v. Alton, 193 111. 301,

61 N. E. 1077 (1901).

This Commission, in approving a regulation of enforced segre

gation in interstate commerce, would be backing the regulation

with governmental authority. Unless approved by the Commis

sion, the carrier regulation segregating the races has no legal

standing whatever. Under the view cited above, it would seem

that the Commisison cannot give its approval without express

authorization from Congress.

2 0

cold. Whereas the seats in car S-6 had foot rests for

the comfort and convenience of the passengers, the

foot rests in car 8-1 were broken and unworkable (R.

21-23); car S-l was very dirty and cold as a result of

which complainants became ill and suffered with cold

all night (R. 21). The women’s rest room in car S-6

is of the size and has the appointments of a rest room

in a Pullman car. It is located in the forward part of

S-6 on the left side down a corridor away from passen

gers. In this room is a large mirror, three individual

wash basins and a separate basin for washing the

teeth. There are three or four chairs in this room

which constitute the lounge portion of the rest room.

The toilets, themselves, of which there are at least

two, are completely private and separated from the

lounge by being in completely enclosed compartments.

In the lounge there is hot and cold water, soap and

towels. There is no women’s lounge in car S-l, only

a toilet room which is located almost immediately to

the rear of the seats therein. It is only large enough

for occupancy of one person. By actual measurements

it is less than four feet in width and less than seven

feet in length. This room has one wash basin, a toilet,

both of which were dirty, a small mirror, and no basin

for washing teeth. There was no hot water, no soap

and no towels (R. 23-27). There was considerable

dirt, filth and roaches in car S-l. There was also con

stant traffic back and forth in the car which annoyed

complainants a great deal (R. 29-31). As a result of

this discomforture, all three sisters became ill.

Although it is accepted as a fact in the proposed

report (Sheet 10) that complainants were cold and un

comfortable and that there were the inferiorities in car

21

S-l set out above, the report concludes that there was

no substantial difference in the accommodations af

forded whites in car S-6 as compared to those afforded

Negroes in car S-l. The fact that complainants were

cold and uncomfortable is explained as due to govern

mental regulation which did not permit the defendant

to maintain the temperature in the cars at more than

65 degrees. Yet complainants were actually in car

S-6 and were quite comfortable, whereas car S-l was

cold. The only conclusion possible, therefore, is that

car S-l was maintained at a lower temperature than

car S-6.

The invalidity of the “ equal facilities” rationale is

vividly demonstrated in this case. Although complain

ants ’ testimony is accepted in substance as to the in

feriorities in accommodations as between the two cars,

this report proposes a finding that no inequality exists.

Except for absolute denial of accommodations it would

seem to be all but impossible to show in more detail

the unequal nature of the facilities afforded. This

Commission should find as a fact that as between car

S-l and car S-6 substantial inequality existed in viola

tion of the Interstate Commerce Act.

V.

Defendant Has Violated Sections One and Two

of the Interstate Commerce Act.

Defendant offers the “ Southerner” to the public for

fast coach travel to points between New York and New

Orleans. Its advantages are speedy travel without the

necessity of shifting or change until one reaches his

destination. Further, reserved seats may be secured

in advance which ensures the prospective passenger of

a seat on the train which is no mean advantage in view

of the crowded condition of all modes of transportation

since the war. It offers dining car facilities and the

use of the tavern car. Space on the train may he

secured at the regular coach fare. All the advantages

cited above are available to white passengers. Some,

however, are not available to Negroes.

The tavern car is maintained exclusively for white

passengers (R. 84). Negroes are not permitted to avail

themselves of this service. This, of course, is a viola

tion of Section 3 of the Interstate Commerce Act, but

we contend that it violates Sections 1 and 2 as well.

There is no contention here that complainants were

charged more than the regular fare, but if whites at

that price may secure in the same train advantages

and accommodations which Negroes cannot obtain, the

Negro passenger is paying the same for less than the

white passenger. Actually, therefore, he is being over

charged and the carrier is charging, collecting and

receiving from the Negro greater compensation for the

service it renders than it charges, collects or receives

from the white.

Further, the inferiority of the appointments in car

S-l maintained for Negroes as compared to car S-6

maintained for whites is further evidence of the fact

that a Negro passenger using defendant’s train re

ceives considerably less for his money than the white

passenger. Defendant has violated, and the Commis

sion should find, both Sections 1 and 2 of the Interstate

Commerce Act.

23

Conclusion.

Complainants, in being ejected from car S-6 which

they were entitled to occupy, were subjected to dis

criminatory treatment in violation of their rights. As

a result of their humiliating experience, complainants

suffered a severe injustice and should be awarded com

pensatory damages. Railroads which are public high

ways should not be permitted to enforce practices for

the handling of passengers which are archaic, dis

criminatory, undemocratic and based upon a theory

of racial superiority which has been shown to be intel

lectually unsound and morally corrupt.

W herefore, complainants request that the Commis

sion reject the conclusions and findings proposed in

the examiner’s report as hereinabove referred to and

grant to complainants the relief requested in their

complaints.

Spottswood W . R obinson, III,

623 North Third Street,

Richmond 19, Virginia,

T hurgood Marshall,

R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York,

Attorneys for Complainants.

Dated August 21, 1947.

Certificate of Service.

I hereby certify that I have this day served the fore

going document upon all parties of record in this pro

ceeding by mailing a copy thereof properly addressed

to each party of record.

R obert L. Carter

Dated this August 20, 1947.

212 [6149]

L a w y e r s P r ess . I n c ., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: B E ek m an 3-2300

No. 14,240

In the

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Geraldine I. Bruce, Minor, by her Father and next Friend,

Elmer Bruce, et a l,

Appellants,

v.

H. W. Stilwell, As President of the Texarkana

Junior College, et al,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Texas

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

W. J. Durham,

Excelsior Life Building,

2600 Flora Street,

Dallas, Texas.

U. Simpson Tate,

1718 Jackson Street,

Dallas, Texas,

Attorneys for Appellants.

W arlick Law Prin ting Co m pa n y — -Caw Hrief Printing — Dallas — HArwood-93JQ

I N D E X

Page

Statement of the Case....................................................... 1

Concise Statement of Fact............................................... 3-4

Specification of Errors..................................................... 5

Argument and Authorities

I. Questions of Law................................................. 6

II. Unauthorized Action .......................................... 12

III. No Administrative Remedy Provided.............. 22

Decision Commissioner of Education

Appendix I ..................................................................... 31-32

11 Index to Authorities

Page

Alston, et al. v. School Board of the City of Norfolk,

112 Fed. 2d 922 (syllabus 2 ) ..................................... 14

Bandini Petroleum Company v. Superior Court o f

California, 52 S. Ct. Rep. 3 (284 U. S. 8 ) .............. 9,17

Battle, et al. v. Wichita Falls Junior College, et al.,

101 Fed. Supp. 82......................................................... 16

Beal, et al. v. Holcombe, Mayor of the City of Hous

ton, et al., 193 Fed. 2d 384......................................... 13

Bear v. Donna Independent School District, et al.,

74 S. W. 2d 179 19, 21

Chastain, et al. v. Mauldin, et al.,

32 S. W. 2d 235.............................................................. 20

Federal Trade Comm. v. Sinclair Refining Company,

43 S. Ct. 450 (261 U. S. 463)..................................... 6

First National Bank of Greely v. The Board of Com

missioners o f Weld County, Colorado, 44 S. Ct. Rep.

385 (264 U. S. 450)..................................................... 21

Henderson, et al. v. Miller, et al., 286 S. W. 501 24

Highland Farms Dairy Company v. Agnew,

57 S. Ct. Rep. 559 (300 U. S. 608)............................ 9

Hilliard v. Brown, United States Representative,

170 Fed. 2d 397............................................................. 15

Kimmins v. Estes, 80 S. W. 2d 387................................ 9

Marrs v. Abshirer, 263 S. W. 263................................ 8

Missions Independent School District v. Diserens,

188 S. W. 2d 568......................................................... 8

Mitchell v. Wright, et al., 154 Fed. 2d 924.................. 15

Montana. National Bank of Billings v. Yellowstone

County, Montgomery, et al., 48 S. Ct. Rep. 331

(276 U. S. 499)............................................................. 28

Mosley v. City o f Dallas, 17 S. W. 2d 36.................... 9

Index to Authorities— (Continued) iii

Page

Mumrae v. Marrs, 40 S. W. 2d 31 10

Palmer Publishing Company v. Smith,

109 S. W. 2d 158...................................................... 8

Price v. People of the State of Illinois, 35 S. Ct, Rep.

892 (238 U. S. 446)..................................................... 26

Railroad Commissioner of Texas v. Pullman Com

pany, 61 S. Ct. Rep. 643 (312 U. S. 496).............. 7

Starkes v. Wickard, 64 S. Ct. Rep. 559

(321 U. S. 288).............................................................. 7

State Line Consolidated School District No. Six (6)

of Parmer County, et al. v. Farwell Independent

School District, et al., 48 S. W. 2d 616.................... 19

State v. Sanderson, 88 S. W. 2d 1069 8

Texas Jurisprudence, Volume 37, Page 918............... 8

Warren v. Sanger Independent School District,

288 S. W. 159.............................................................. 9

Williams v. White, 223 S. W. 2d 278 11

Wilson v. Abilene Independent School District,

190 S. W. 2d 406......................................................... 7

Wilson v. City of Paducah, 100 Fed. Supp. 116 16

Zucht v. San Antonio School Board, 170 S. W. 840 8

Constitution of Texas:

Article VII, Sections 1-7, Sections 10-15 11

Texas Revised Civil Statutes:

Article 2900 ................................................................ 16, 17

Article 2654-1 .............................................................. 10

Article 2654-7 .............................................................. 31

Article 2656 ..................................................................19, 20

Article 2686 ................................................... 7, 9,10,19, 20

Article 2815h ................................................................ 11

No. 14,240

In the

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Geraldine I. Bruce, Minor, by her Father and next Friend,

Elmer Bruce, et al,

Appellants,

v.

H. W. Stilwell, As President of the Texarkana

Junior College, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Texas

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Appellants are five Negro minors who bring this appeal

by their next friends, all of whom are citizens of the State

of Texas and of the United States, and residents of Bowie

County, Texas. They all, and each of them reside within

the Texarkana Junior College District.

The original action was filed on, to wit, May 10, 1949,

in the United States District Court for the Eastern Dis-

2

trict of Texas, as Civil Action No. 272, styled Edwardlene

M. Fleeks, et al, v. H. W. Stilwell, et al., as officers and

members of the Board of Trustees of the Texarkana Inde

pendent School District and of the Texarkana College Dis

trict, complaining that the Defendants below, Appellees

herein, had adopted policies, practices, customs and usages

in the operation of the Texarkana public schools and the

Texarkana Junior College which resulted in unlawful dis

criminations against the Appellants, because of their race

and color. Appellants prayed for a declaratory judgment

and injunction to restrain Appellees from further discrim

inating against them in providing and affording educa

tional opportunities, facilities and advantages within the

District.

Due to the long delay in bringing the matter to trial Ap

pellants amended their complaint several times to substi

tute new parties plaintiff for those who had completed the

prescribed courses in the elementary or secondary schools

or two or more years of college. They also amended their

complaint to drop parties defendant who had served their

terms on the Board and to add new parties defendant as

new members were elected to the Board.

Upon a Motion To Sever the two causes of action and an

Order by the Court directing Appellants to sever their

causes of action, this cause was filed on, to wit, May 19,

1952, as Geraldine I. Bruce, et al. v. H. W. Stihvell, et al.,

as Officers and Members of the Board of Trustees of the

Texarkana Junior College District. Appellees filed their an

swer on, to wit, May 29, 1952, and the cause came on for

3

trial before the Court, without a jury on, to wit, June 5,

1952.

At the opening of the trial Appellees filed their Motion

To Dismiss the cause on the ground that Appellants had

failed to plead that they had exhausted their administra

tive remedy provided under Texas Law, in that there was

no pleading that they have appealed from the decision of

the Junior College Officials to the higher school authorities

of the State. (R. 20.)

The Court sustained Appellees’ Motion to Dismiss, and

issued an Order of Dismissal, on the ground that the Court

was without jurisdiction to try the cause. (R. 20-21.)

It is from this Judgment and Order that this appeal is

taken.

CONCISE STATEMENT OF FACT

Appellants’ Bill of Complaint alleged, in substance, that

the Appellees, as Officers and Members of the Board of

Trustees of the Texarkana Junior College District were

operating the Texarkana Junior College out of public

funds for the exclusive use and enjoyment of members of

the Caucasian or non-Negro races and that Appellants

were denied the use and enjoyment of the junior college

facilities provided and afforded by Appellees because of

the race and color of Appellants; that the management and

control of the college were vested in Appellees by State

laws; that the college was organized and exists pursuant to

State laws; that it is an instrumentality of the State; that

4

Appellees are Agents and Administrative officers of the

State; that the College District is a corporation under Texas

laws; that Appellants are members of the colored or Negro

race; that they had presented themselves for admission bo

the college and demanded admission and that Appellees have

failed and refused to admit them because of their race

and color and in violation of the laws of the State of Texas

and of the United States; that they were eligible to attend

the college; that they were ready and willing to pay all law

ful and necessary tuitions and fees and to take all reason

able and lawful pledges and submit to all reasonable and

lawful rules and regulations of the college, and that no

similar or equal junior college facilities have been provided

for Appellants by Appellees within the junior college dis

trict.

Appellants prayed for relief by way of a declaratory

judgment declarative of the rights and legal relations of

the parties to the cause, and for a permanent injunction

to restrain and enjoin Appellees from further discrimi

nation against Appellants by refusing them the use and

enjoyment of the available junior college facilities within

the district because of the race and color of Appellants,

there being no other facilities available to them within the

district.

Appellees answered denying that they had discriminated

against Appellants because of their race or color and deny

ing that Appellants were entitled to attend the Texarkana

Junior College.

5

SPECIFICATION OF ERRORS

I.

The Trial Court erred in granting Appellees’ Motion to

Dismiss Appellants’ Bill of Complaint for the reason that

the only material questions before the Court were ques

tions of law.

II.

The Trial Court erred in granting Appellees’ Motion

to Dismiss Appellants’ Bill of Complaint for the reason

that the alleged unlawful acts on the part of the Appellees

were done without any power or authority vested in Ap

pellees under the laws of the State of Texas and in direct

contravention of rights guaranteed to Appellants by the

constitution and laws of Texas and the constitution and

laws of the United States.

III.

The Trial Court erred in granting Appellees’ Motion to

Dismiss Appellants’ Bill o f Complaint for the reason that

the State of Texas has not created or provided any ad

ministrative agency with power or jurisdiction to de

termine or adjudicate the issues raised in Appellants’ Bill

o f Complaint.

I.— (Restated)

The Trial Court erred in granting Appellees’ Motion to

Dismiss Appellants’ Bill of Complaint for the reason that

the only material questions before the Court were ques

tions of law.

6

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES DISCUSSED

UNDER SPECIFICATION OF ERROR

NUMBER I.

The only material questions before the trial court in this

cause were: (1) whether Appellees, as Agents and Admin

istrative Officers of the State of Texas, were authorized

by Texas laws to operate and maintain a junior college for

the sole and exclusive use and enjoyment of members of

the Caucasian or non-Negro races out of public funds and

refuse and deny the use and enjoyment of the facilities of

the said junior college to Appellants because of their race

and color, when no similar or equal junior college facilities

had been provided for Appellants, and, (2) the question

whether the acts of Appellees, while acting under color of

law, as Agents and Administrative Officers of the State

of Texas, in denying and refusing to Appellants the use

and enjoyment of the facilities of the said junior college

because of the race or color of Appellants, were in viola

tion of the Constitution and laws of the United States,

It is almost universally accepted law that administrative

agencies are creatures of the legislature; that their powers

are derived from the statutes by which they are created and

that they have no common law powers.

Federal Trade Comm. v. Sinclair Refining Co., 261

U. S. U63, US S. Ct. U50.

Administrative agencies may make reasonable rules and

regulations for carrying out their proper functions, but

7

when the question of the construction of their own enabling

statute arises, for the purpose of determining their own

powers and the limitations on their powers, a judicial ques

tion immediately arises, which is beyond the limits of their

operations.

Railroad Comm, of Texas v . Pullman Co., 812 U. S.

U96, 61 S. Ct. 6AS;

Starks v. Wickard, 821 U. S. 288, 6U S. Ct. 559.

In Wilson v. Abilene Independent School District, 190

S. W. 2d 406, where parents of school age children sought

to enjoin the enforcement of an order by the School Trus

tees which prohibited students of the junior and senior high

schools of the district from joining fraternities not ap

proved by the principal of the school, on the ground that

the order was unreasonable, arbitrary and discriminatory,

the defendants moved to dismiss the action saying that

plaintiffs had not exhausted their administrative reme

dies under Article 2686 of the Revised Civil Statutes of

Texas and that this ousted the jurisdiction of the Court.

The trial court took jurisdiction and denied the petition for

injunction. Affirmed on appeal. The Court said: Our

Courts have pointed out when a direct appeal to the Courts

is proper procedure. The Rule is that where the questions

involved are purely questions of fact the appeal should be

made through the school authorities. But, if they be ques

tions of law, then an appeal direct to the Courts should be

made. (Emphasis added.)

8

Missions Ind. School Dist. v. Diserens, 188 S. W. 2d

568;

Palmer Publishing Co. v. Smith, 109 S. W. 2d 158;

37 Texas Jurisprudence, 918-23, Secs. 53-55.

In Zucht v. San Antonio School Board, 170 S. W. 8JO,

where the action was to enjoin a rule of the board which

required all children to be vaccinated and for mandamus

to compel the admission of the children, the Court said:

“ As the legislature did not expressly empower the

school board to adopt the regulation in question, it

must be determined whether the same is reasonable.

Whether an ordinance or regulation is reasonable is

a question of law for a court * * (Emphasis added.)

Mam's v. Abshirer, 263 S. W. 263;

56 C. J. 853, Sec. 1091;

37 Tex. Jur. 1059, Sec. 173.

In Missions Ind. School Dist. v. Diserens, 188 S. W. 2d

568, where the school board was seeking specific perform

ance under a contract between a teacher and the board, the

defendant teacher moved to dismiss on the ground that the

board had not exhausted the administrative remedy open

to it under State law. Quoting State v. Sanderson, 88 S. W.

2d 1069, the Court said:

“ It is well settled that in all matters pertaining to

the administration of school laws involving questions

of fact as distinguished from pure questions of law,

resort must first be had to the school authorities and

9

the method of appeal there provided for exhausted be

fore the court will entertain jurisdiction of a complaint

with reference to such matters.”

Warren v. Sanger Ind. School Dist., 288 S. W. 159;

Mosley v. City of Dallas, 17 S. W. 2d 36.

In construing state statutes, federal courts will be per

suaded by the construction put on such statutes by the

State’s highest court.

Highland Farms Dairy Co. v. Agnew, 300 U. S. 608,

57 S. Ct. 559;

Bandini Petroleum Co. v. Superior Court of Calif.,

28i U. S. 8, 52 S. Ct. 3.

Article 2686 of the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas, which

is the Appeals Statute in question, provides :

“ All appeals from the decision of the County Super

intendent of public instruction shall lie to the County

Board of School Trustees, and should either party de

cide to further appeal such matters, they are here given

the right to elect to appeal to any court having proper

jurisdiction of the subject matter; or to the State

Superintendent of Public Instruction as now provided

by law, * *

In Kimmins v. Estes, 80 S. W. 2d 387, where Article

2686 is construed by the Court of Civil Appeals of Texas,

the Court said: “ * * * under the appeals statute, Article

2686, as amended in 1927, the aggrieved party is given

an option, after he has had a hearing before the trustees

10

of the independent district or county trustees to : (a) ap

peal to the state superintendent of public instruction (now

Commissioner of Education), or (2) go into any court hav

ing proper jurisdiction of the subject matter.

If the aggrieved party elects to take his appeal to the

Commissioner of Education, Article 2654-7, defines the

procedure therefor, but adds: “ * * * nothing contained

in this Section shall deprive any party of a legal remedy.”

JUNIOR COLLEGES

Article 2686 relates to controversies and disputes that

arise under the public school laws of the State of Texas.

This being true, a very serious question may be raised as

to whether it has any application to the management and

control of junior colleges.

Article 2654-1, Section 2, provides, in part:

“ The Central Education Agency shall exercise, un

der the acts of the legislature, general control of the

system of public education at the State level. Any

activity with persons under twenty-one (21) years of

age, which is carried on within the State by other

State or Federal agencies, except higher education in

approved colleges, shall in its educational aspects be

subject to the rules and regulations of the Central

Education Agency.” (Emphasis added.)

In Mumme v. Marrs, M) S. W. 2d 31, a clear distinction

is drawn between our system of public free schools, as pro

vided for in the Constitution of Texas, Article VII, Sec

tions 1 to 7 inclusive, and our system of higher education

Court and Jim Crow

The Monday decision of the United

States Supreme Court banishing Jim

Crow from our transport facilities is

doubtless historic. Whether the principle

enunciated can or should be extended to

the entire field of segregation constitu

tionally is another question. Racial preju

dices are as deeply ingrained as racial

differences. When you consider them, it

seems to The News that one principle re

mains crystal clear:

Involuntary association should not be j

act up by law any more than should in

voluntary segregation.

Where, then, is the dividing line? That

is a fair question, but not one difficult

to solve. In some respects a solution is

expensive, but if the citizenry of any

commonwealth is willing to pay the price,

that should be its right.

If the Constitution means what it says,

the Negro citizen can not be segregated

rightfully in public services rendered

under franchise, in public employment, in

open market purchase of his home site or

other property.

Nor, if the Constitution means what

it says, can the white citizen be rightfully

compelled to make his private business

or employment open to anyone whom he

does not wish to serve or hire.

Public Schooling furnishes the border

line case with its expensive solution.

But, since this necessarily involves the

social relationship of the two races, The

News believes firmly that the majority

THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS

N O V E M B E R 12, l » g g

have the right to segregate so long as

equal educational facilities are provided.

The Constitution can not alter human

nature. There is a fatal flaw in the other

wise laudable program of the National

e Association for the Advancement of

Colored Peoples. This is the simple fact

' that in contending rightly against the in

voluntary segregation of the Negro, they

insist that the white must be forced in

voluntarily into association.

11

as provided for in Sections 10 to 15 inclusive of Article VII

o f the Constitution of Texas.

The Court said that the authority granted to the legis

lature in Article VII, Sections 10 to 15 inclusive, to create

the institutions mentioned therein was not a limitation

on its powers to create other similar institutions of higher

learning and that the legislature had already created ten

or more institutions of similar character without the con

sent of the Constitution.

The legislature enacted Article 2815h which specifically

authorizes the establishment of a system of junior colleges

throughout the State and arranged for the procurement of

lands and the construction of buildings by special bond is

sues and vested these college districts with taxing power to

raise revenue for operations, and the legislature, by spe

cial appropriation acts, provides other revenue for them,

that is different from the revenue sources of public free

schools.

In William v. White, 223 S. W. 2d 278, the Court held as

a conclusion of law, that junior colleges are institutions of

higher learning in Texas and that the provisions of Section

3 of Article VII of the Constitution of Texas are not appli

cable to junior colleges.

The premises considered, Appellants respectfully submit

that the Trial Court erred in granting Appellees’ Motion

to Dismiss Appellants’ Bill of Complaint and the judgment

and order of the Trial Court should be reversed.

12

II.— (Restated)

The Trial Court erred in granting Appellees’ Motion

to Dismiss Appellants’ Bill of Complaint for the reason

that the alleged unlawful acts on the part of the Appellees

were done without any power or authority vested in Ap

pellees under the laws of the State of Texas and in direct

contravention of rights guaranteed to Appellants by the

constitution and laws of Texas and the constitution and

laws of the United States.

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES DISCUSSED

UNDER SPECIFICATION OF ERROR

NUMBER II.

The appellants alleged that at State expense and out of

public funds, the Appellees, as administrative officers of

the State of Texas, were making available educational op

portunities, advantages and facilities in the Texarkana

Junior College, to white citizens, and were refusing equal

educational opportunities, advantages and facilities to mi

nor Appellants in such junior college district on account

of their race and color; in fact, Appellants allege that the

Appellees had failed and refused any such facilities, ad

vantages and opportunities at all to minor Appellants on

account of race and color (Tr., p. 13, Allegation 11). They

further allege that such acts on the part of the Appellees

were unlawful, unconstitutional, and in violation of rights

guaranteed to the Appellants under the Constitution of the

United States— equal protection of laws.

13

The Appellants therefore contend, that they were en

titled to complain to the Court that their constitutional

rights to equal protection of laws had been invaded, and

that such constitutional rights having been violated, the ap

pellants were entitled to go directly to the court for relief.

The above proposition appears to be sustained in the

opinion in the case of Beal, et al. v. Holcombe, Mayor of the

City of Houston, et al, 193 Federal 2d 38k- In that case

the facts were identical to the facts in this case, except

the Beal case was a golf case and there was no alleged ad

ministrative remedy, and this case affects a junior col

lege. In the Beal case, at public expense, the City had fur

nished to non-Negro citizens, golf facilities which were re

fused and denied to Negro citizens on account of race and

color, and Chief Judge Hutcheson speaking for the court

said (193 Fed. 2d 387):

“ He erred in law because his conclusion is contrary

to the general principles established by the authorities,

‘It is the individual who is entitled to the equal protec

tion of the laws, and if he is denied * * * a facility or

convenience * * * which, under substantially the same

circumstances, is furnished to another * * * he may

properly complain that his constitutional privilege has

been invaded’.”

The Appellees, as administrative officers of the State of

Texas, having made available educational advantages,

training facilities, and opportunities on the Junior College

level to non-Negro citizens, and under identical circum

stances having refused to make such available equal facil

ities to the minor Appellants on account of race and color,

14

the Appellants contend that they were entitled to go di

rectly to the Court for relief, unless they were compelled

to first resort to an administrative agency set up under

the laws of the State of Texas, before resorting to the

Court. Appellants contend that under the Texas Statute,

their alleged cause of action was the type of cause of action

that they could maintain in the Court without applying to

the administrative agency and exhausting the adminis

trative remedies for the reason, that the administrative

agency had no jurisdiction or power to determine the is