Memo RE: Meeting Agenda

Public Court Documents

March 5, 1999

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Memo RE: Meeting Agenda, 1999. 1e0fccad-a146-f011-877a-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/25d6810f-dad8-4815-a668-b255312c2a3d/memo-re-meeting-agenda. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

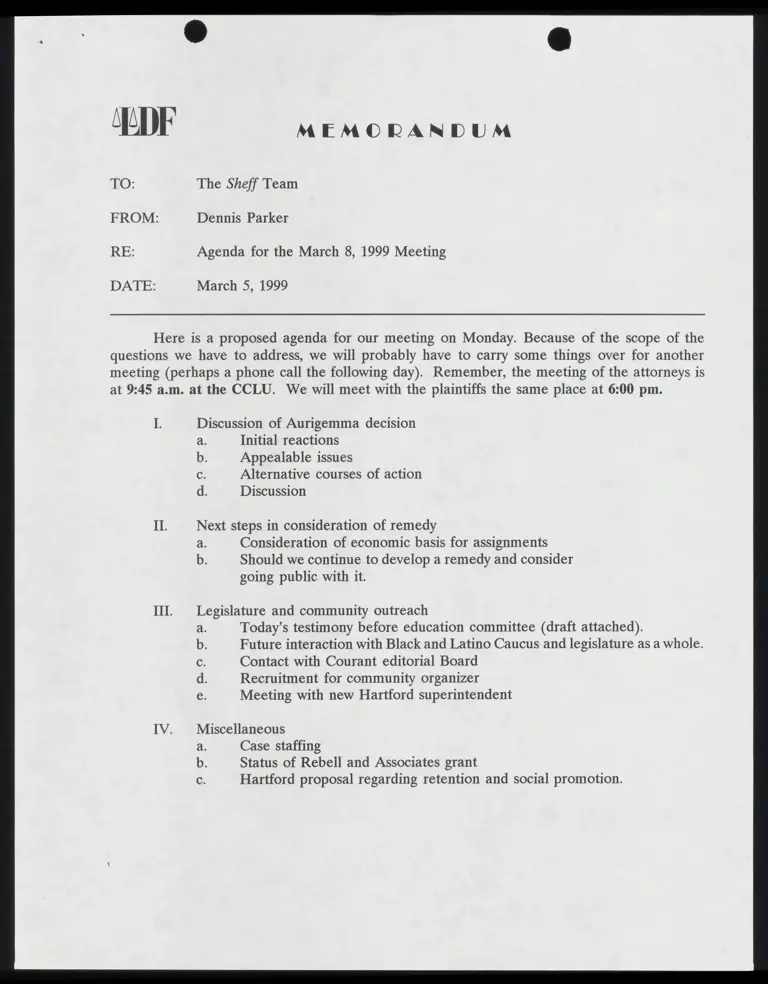

MEMORANDUM

TO: The Sheff Team

FROM: Dennis Parker

RE: Agenda for the March 8, 1999 Meeting

DATE: March 5, 1999

Here is a proposed agenda for our meeting on Monday. Because of the scope of the

questions we have to address, we will probably have to carry some things over for another

meeting (perhaps a phone call the following day). Remember, the meeting of the attorneys is

at 9:45 a.m. at the CCLU. We will meet with the plaintiffs the same place at 6:00 pm.

I. Discussion of Aurigemma decision

a. Initial reactions

b Appealable issues

C. Alternative courses of action

d Discussion

IL. Next steps in consideration of remedy

a. Consideration of economic basis for assignments

b. Should we continue to develop a remedy and consider

going public with it.

III. Legislature and community outreach

a. Today’s testimony before education committee (draft attached).

b. Future interaction with Black and Latino Caucus and legislature as a whole.

C. Contact with Courant editorial Board

d. Recruitment for community organizer

e, Meeting with new Hartford superintendent

IV. Miscellaneous

a. Case staffing

b. Status of Rebell and Associates grant

C. Hartford proposal regarding retention and social promotion.

Draft of March 1999 Testimony

The Plaintiffs in Sheff v. O’Neill respectfully submit this

statement to express their concern and frustration with the State of

Connecticut’s continuing failure to adequately address the

unconstitutional racial and ethnic isolation in the Hartford

metropolitan area.

As you know, this week we received the most recent decision in Sheff

v. O'Neill from the Superior Court. We are now studying the decision and

considering our options. From the outset, however, we think it is

important to clarify what we believe is a significant misstatement of

the plaintiffs’ position. We did not then, nor do we now, urge that the

Court choose between a '"mandatory’ and ‘'voluntary" plan. Instead, we

sought to demonstrate that the benchmark of any plan is its

effectiveness and that, using this standard, the state’s efforts to date

have been sorely lacking. We believe that compliance with the Supreme

Court’s Order requires that goals be defined and measures be identified

that have a realistic chance of achieving those goals.

Although there are many parts of the opinion with which we disagree

strongly, there are some things that are beyond dispute. Clearly, the

Superior Court decision did nothing to alter the state’s responsibility

for remedying the racial and ethnic isolation which exists in the

Hartford Metropolitan area. Whether or not the plaintiffs ultimately

decide to appeal the decision, we remain committed to enforcing the

letter and spirit of the Supreme Court Order.

We believe that the action brought by the plaintiffs was both

timely and necessary to enforce the constitutional rights of children

in the Hartford region. As detailed in the record in this case, the

children of Hartford have waited long enough. As you know, as early as

1966 a team from Harvard made a series of recommendations to overcome the

racial isolation of the Hartford schools. Since that time, there have

been a plethora of statewide commissions, committees, forums, processes

and panels devoted to the question. And there has been no shortage of

ideas, some of which have been piloted now for years, even decades.

These programs were put into place before the Supreme Court decision in

July, 1990. That decision, therefore, required more. As the Court

stated nearly three years ago, "the system of public education in

Hartford and the Hartford region deprives plaintiffs’ schoolchildren of

the right to a substantially equal educational opportunity based on

racial and ethnic isolation and segregation and exists in the Hartford

Public Schools and among school districts in the Hartford region."

Noting both the severity of the constitutional violation and the

decades-long history of repeated studies and ineffective programs, the

Supreme Court issued a clear and unequivocal directive to the State

n defendants to "put the search for appropriate remedial measures at the

top of the respective agendas’ and insisted that this be done "in time to

make a difference before another generation of children suffers the

consequences of a segregated Public School education." Hopeful that

the Supreme Court's straightforward and unambiguous mandate would spur

the State to take steps to deal effectively with the unconstitutional

condition of the educational system, the plaintiffs waited patiently for

legislation which would, finally, reverse the pattern of increasing

racial and ethnic isolation in the Hartford Metropolitan area.

Instead, the plaintiff watched with mounting frustration as racial

and ethnic isolation increased - in Hartford alone, the minority

population, which accounted for 90% of student enrollment at the time

the Sheff lawsuit was filed, increased to 94% minority by the 1997-98

school year. In the face of these rising levels of racial and ethnic

isolation, plaintiffs watched as the State re-presented slightly

modified versions of existing programs which had already proven

unsuccessful at reducing racial and ethnic isolation.

Convinced that there was nothing in the State’s legislative

response which promised to remedy unconstitutional racial and ethnic

isolation, the plaintiff availed themselves of their right under the

Supreme Court opinion to return to the Superior Court for vindication of

their constitutional rights.

Indeed, the Sheff plaintiffs believe strongly that none of the

state’s efforts to date, up to and including the Commissions January,

1999 Report Advancing Student Achievement and Curriculum, and Reducing

Student Isolation, has reduced racial and ethnic isolation or promises

to do so in the foreseeable future. The effects of this failure are

enormous. Although, racial and ethnic isolation adversely effects all

students, the results will be felt most sharply by African-American and

Latino students who have historically suffered educationally.

Plaintiffs submit that the record tells a compelling and sobering

story of the State’s failure and urge that the legislature carefully

review thes trial transcript as a part of ‘its evaluation of the

Commissioner’s report.

At the September hearing, the plaintiffs presented evidence that

the welter of educational programs which the state presented as a

comprehensive response was neither comprehensive nor responsive to the

Supreme Court’s mandate. Testimony showed that the programs embodied

in the Commissioner's February, 1998 section of the five year plan

entitled Achieving Resource Equity were, for the most part, new

incarnations of programs which were in existence at the time of the

Supreme Court’s opinions which the Court itself had found to be

inadequate. And the one wholly new program, charter schools, was one

which, in its first year of operation, had resulted in the creation of

only two new schools in the Hartford metropolitan area -- and these were

racially identifiable.

The. plaintiffs faulted: the state’s . response both for its

ineffectiveness to date and for the unlikelihood that the programs would

lead to significant reduction of racial isolation in the future. Based

upon years of experience in educational administration and school

desegregation cases, plaintiffs experts testified that the combined

effects of the interdistrict cooperative grant programs, magnet

schools, lighthouse schools and Project Choice, the highly touted

version of Project Concern which actually falls far short of that

program’s success and the aforementioned charter schools would be

negligible in its effect on reducing racial isolation.

Most significantly, each of the three, nationally recognized

expert witnesses testified that the programs which the state described

could not be described as a plan to reduce racial and ethnic isolation

regardless of the educational desirability of some of the programs.

These same experts agreed that a plan was vital to the successful

reduction of racial and ethnic isolation.

As our “Guidelines to an Effective Plan for Quality, Integrated

Education” make clear, the plaintiffs did not advocate mandatory

reassignment as the only alternative to the state's approach. Let us

emphasize: at no time have the Sheff plaintiffs argued that the Board of

Education must adopt a mandatory reassignment plan. Instead,

plaintiffs’ evidence showed that there were a number of indispensable

elements which any successful plan must contain and that each of these

essential elements were absent in the state’s legislative response.

Included among these were the existence of quantitative goals for the

reduction of racial and ethnic isolation, timelines for achieving those

goals and clear legislative procedures for dealing with the failure to

achieve the goals set. Ironically, the evidence showed that the 1997

legislation (P.A. 97-290) seemed to depart from the example offered by

the state’s racial imbalance act which, whatever its shortcomings as a

measure that applies only to infradistrict imbalance, does provide clear

and enforceable guidelines to the school districts in the state as to

what is expected of them.

Instead of clear guidelines, the record shows that the state has

substituted the vague and largely unenforceable obligations upon school

districts to "provide educational opportunities for its students to

interact with students and teachers from other racial, ethnic, and may

provide such opportunities with students from other communities."

(emphasis added). This obligation would be measured by the equally

nebulous standard of "evidence of improvement over time."

In addition to its vagueness, the chief fault of the state’s set of

programs is that it turns a deaf ear to the Supreme Court decision

(indeed, the chief expert witness for the state flatly asserted that she

felt that the Connecticut Supreme Court’s decision was ‘"wrong").

Nowhere in the opinion’s frequent discussion of school enrollments does

the Court suggest that ‘interracial contact" would be sufficient to

satisfy constitutional mandates, particularly when, as is the case with

the state’s interdistrict grant programs, some of which are of only

several days duration. Moreover, the state’s legislative package, with

its permissive language regarding exposure between different

communities, fails to address the Supreme Court’s recognition that the

existence of firmly established town attendance boundary lines is at the

heart of the constitutional violation.

At the time of the hearing, the state, most notably through

testimony of Commissioner Sergi, pointed to the Commissioner's upcoming

January 1999 report as one which would contain further new Initiatives

designed to reduce racial and ethnic isolation. Indeed, the Court cited

the fact that the five year plan was not completed as part of the reason

that it felt that the plaintiffs’ efforts were premature.

The Sheff plaintiffs are saddened to see that the hopes expressed

by the Court that there would be further steps to reduce racial and

ethnic isolation were not realized. The January 1999 report Advancing

Student Achievement and Curriculum, and Reducing Student Isolation

brings nothing new to the table and does nothing to dispel their

skepticism about the possibility of future success. Notwithstanding the

high expectations that were created for it, the new report fails to

describe even a single new program choosing instead to provide increased

funding for the existing programs. Missing in all of the legislation 1s

a clear, quantitative definition of what would constitute "reduction of

racial and ethnic isolation". That absence creates the possibility, and

indeed the likelihood, that despite the state’s efforts, the Hartford

School district will continue its steady movement toward become a

substantially completely minority school district. Indeed, in his

testimony, Commissioner Sergi allowed that were that to occur, he would

not regard that as necessarily indicating that the state’s efforts

failed.

We submit that such an approach mocks the Supreme Court’s holding

and denigrates the hard-fought constitutional rights of all students in

the Hartford metropolitan area. When the Supreme Court instructed this

body to create a remedy for racial and ethnic isolation, it entrusted it

with the priceless constitutional rights of its youngest citizens. We

feel strongly that the worst consequence of the recent decision would be

if the state regarded it as license to relax the search for methods to

address constitutional violations. To date, the State of Connecticut

has not discharged its obligations and has left the rights and needs of

many of its most vulnerable citizens unanswered. The Sheff plaintiffs

urge that the problems be addressed and be addressed now, before another

generation of children are damaged.

FAX COVER SHEET

John Brittain 860/570-5242

Sandy DelValle 516/496-7934

Juan Figueroa 212/431-4276

Chris Hansen 212/549-2651

Wes Horton 860/728-0401

Marianne Engelman Lado 212/802-5968

Willy Rodriguez 860/541-5050

Martha Stone 860/570-5256

Phil Teleger 860/728-0287

Elizabeth Sheff 860/527-3305

Dennis Parker

Agenda for the March 8, 1999 Meeting

March 5, 1999

NUMBER OF PAGES (INCLUDING THE COVER SHEET) 10

IF YOU DO NOT RECEIVE THE NUMBER OF PAGES INDICATED ABOVE,

PLEASE NOTIFY US IMMEDIATELY AT 212\219-1900.