Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City v. Dawson Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City v. Dawson Jurisdictional Statement, 1955. 2a6b2172-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/25dc31e2-5d9b-4066-94d4-6cce6cb821dc/mayor-and-city-council-of-baltimore-city-v-dawson-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

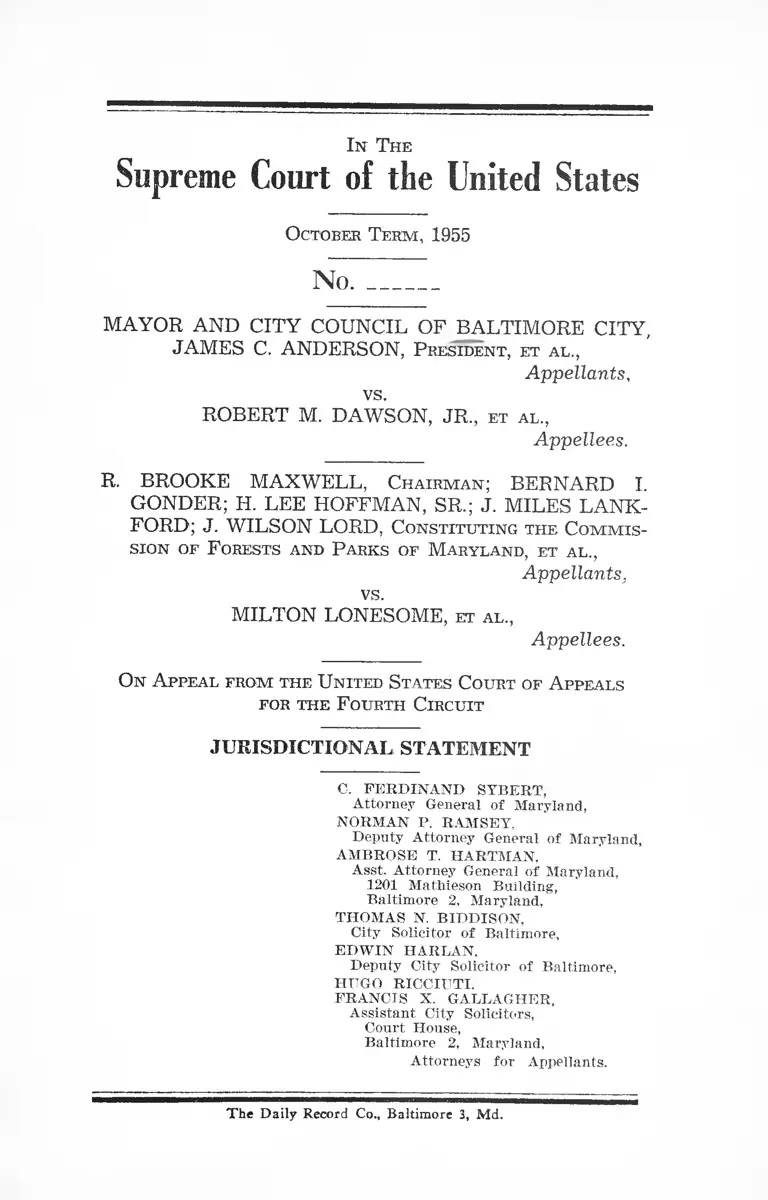

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober T e r m , 1955

No.

MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE CITY,

JAMES C. ANDERSON, P r e sid e n t , et a l .,

Appellants,

vs.

ROBERT M. DAWSON, JR., et a l .,

Appellees.

R. BROOKE MAXWELL, C h a ir m a n ; BERNARD I.

GONDER; H. LEE HOFFMAN, SR.; J. MILES LANK

FORD; J. WILSON LORD, C o n s t it u t in g t h e C o m m is

s io n o f F orests a n d P arks o f M aryland , e t a l .,

Appellants,

vs.

MILTON LONESOME, et a l .,

Appellees.

O n A p p e a l f r o m t h e U n it e d S ta tes C o u rt of A ppea ls

fo r t h e F o u rth C ir c u it

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

C. FERDINAND SYBERT,

Attorney General of Maryland,

NORMAN P. RAMSEY,

Deputy Attorney General of Maryland,

AMBROSE T. HARTMAN,

Asst. Attorney General of Maryland,

1201 Mathieson Building,

Baltimore 2, Maryland,

THOMAS N. BIDDISON,

City Solicitor of Baltimore,

EDWIN HARLAN,

Deputy City Solicitor of Baltimore,

HUGO RICCIUTI,

FRANCIS X. GALLAGHER,

Assistant City Solicitors,

Court House,

Baltimore 2, Maryland,

Attorneys for Appellants.

The Daily Record Co., Baltimore 3, Md.

I N D E X

S u bject Index

page

S ta tem en t as to J u risd ictio n .................................................. 1

Opinion Below ................................................................. 2

Jurisdiction .................................................................. 2

Questions Presented ....................................................... 3

Statutes Involved ...................................................... 3

Statem ent of F ac ts :

Lonesome Case .................................................... 7

Dawson C a se ........................................................ 9

The Questions Are Substantial.................................... 12

A lternate Certiorari A ppl ic a t io n ................................... 20

A ppen d ix “A” :

I. Opinion of United States Court of Appeals for

Fourth Circuit (per cu riam ).................................... 21

II. Opinion of U nited States D istrict Court for

D istrict of M aryland 25

A ppen d ix “B” :

I. Constitution of M aryland, Article XI-A 49

II. A nnotated Code of M aryland (Flack’s 1951

Ed.), Article 66C, Sections 340, 342 54

III. Charter and Public Local Laws of Baltim ore

City (Flack’s 1949 Ed.), Sections 96 and 6 56

T able o f C it a t io n s

Cases

PAGE

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, (subseq. op., 99 L.

Ed. 653) ................................................................7, 12, 14, 16

Boyer v. G arrett, 88 Fed. S. 353, aff’d. 183 F, 2nd 582,

cert, denied 340 U.S. 912............................................ 4, 14

Bradford Electric Light v. Klapper, 284 U.S. 221....... 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 492 (subseq.

op, 99 L. Ed. 653)......................................... 7, 12, 14,16,19

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704, 50 S. Ct.

407, 74 L. Ed. 1128........................................................ 3

Durkee v. M urphy, 181 Md. 259, 29 Atl. 2nd

253 ...................................................................... 4 ,5 ,13,14,17

Eclipse Mills Co. v. Dep’t. of Labor and Industry, 277

U.S. 136 .................................................................... 3

Henderson v. U. S , 339 U.S. 816..................................... 14

Keating v. Public Nat. Bank, 284 U.S. 587, 52 S. Ct.

137, 76 L. Ed. 507.......................................................... 2, 3

King Mfg. Co. v. Augusta, 277 U.S. 100, 104-5............. 3

Koram atsu v. U. S , 323 U.S. 214, 216............................. 16

Law v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore, 78 F.

Supp. 346 ...................................................................... 4̂ 14

McCarrol, Commissioner of Revenues of Arkansas v.

• Dixie Greyhound Lines, In c , 309 U.S. 176, 60

S. Ct. 504, 84 L. Ed. 683............................................. 2

McLaurin v. Oklahoma Bd. of Regents, 339 U.S. 637 14

New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 52 S.

Ct. 371, 76 L. Ed. 747................................................. 2

People of State of N. Y. v. Latrobe, 279 U.S. 421,

49 S. Ct. 377, 73 L, Ed. 776....................................... 2

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537......................... 3, 4, 12, 14, 15

Republic Pictures Corp. v. Kappler, 327 U.S. 757, 66

S. Ct. 523, 90 L. Ed. 991, rehearing denied 327

U.S. 817, 66 S. Ct. 804, 90 L. Ed. 1040 2

I l l

PAGE

Williams v. Bruffy, 96 tLS. 176, 183............................... 3

Williams v. Zimmerman, 172 Md. 563, 567, 192 Atl.

353, 355 .......................................................................... 13, 14

Sta tu tes and other Authorities

Title 8, U.S.C., Secs. 41, 43............................................... 2

Title 28, U.S.C., Sec. 1254(2)........................................... 2, 3

Title 28, U.S.C., Sec. 1331................................................. \

Title 28, U.S.C., Sec. 1343................................................. 2

Title 28, U.S.C., 1946, Sec. 347

Title 28, U.S.C, Sec. 2201-2............................................... 2

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rules 23A, 57, 65 2

Constitution of M aryland, Article XI-A.......................6, 9, 49

Annotated Code of M aryland (1951), Article 66C,

Sections 340 et seq................................................ 6, 7, 13, 54

C harter and Public Local Laws of Baltim ore City,

Sec. 6(19) .............................................................6,9,19,57

C harter and Public Local Laws of Baltimore City,

Section 96 ..................................................................6, 10, 56

In T h e

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober T e r m , 1955

No______

MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE CITY,

JAMES C. ANDERSON, P r e sid e n t , e t a l .,

Appellants,

vs.

ROBERT M. DAWSON, JR., et a l .,

Appellees.

R. BROOKE MAXWELL, C h a ir m a n ; BERNARD I.

GONDER; H. LEE HOFFMAN, SR.; J. MILES LANK

FORD; J. WILSON LORD, C o n s t it u t in g t h e C o m m is

s io n of F orests a n d P a rk s of M aryland , e t a l .,

Appellants

vs.

MILTON LONESOME, et al .,

Appellees.

On A ppe a l f r o m t h e U n it e d S ta tes C ourt of A ppea ls

fo r t h e F o u rth C ir c u it

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants appeal from the judgm ents of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, entered on

M arch 14, 1955, reversing the final judgm ents of the United

States D istrict Court for the D istrict of M aryland, and sub

m it this S tatem ent to show tha t the Suprem e Court of the

United States has jurisdiction of the appeal and tha t a sub

stantial question is presented.

2

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit is reported at 220 Fed. 2d 386.

The opinion of the U nited States D istrict Court for the

D istrict of M aryland is reported in 123 Fed. Supp. 193.

Copies of the opinions of each of the Courts are attached

hereto as Appendix A.

JURISDICTION

These suits w ere brought under Title 28 U.S.C., Section

1331; Title 8 U.S.C., Sections 41 and 43; T itle 28 U.S.C.,

Section 1343; Title 28 U.S.C., Sections 2201-2202; and Rules

23A, 57 and 65 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The

judgm ents of the D istrict Court w ere entered on the 25th

day of August, 1954; notice of appeal was filed in tha t Court

on the 17th day of September, 1954; the judgm ents of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit w ere

entered on the 14th day of March, 1955; and notice of ap

peal was filed in tha t Court on April 30, 1955. The ju ris

diction of the Supreme Court to review this decision by

appeal is conferred by Title 28 U.S.C., Section 1254(2). The

following decisions sustain the jurisdiction of the Suprem e

Court to review the judgm ents in these cases: McCarrol,

Commissioner of Revenues of Arkansas v. D ixie G rey

hound Lines, Inc., 309 U.S. 176, 60 S. Ct. 504, 84 L. Ed. 683;

New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 52 S. Ct. 371,

76 L. Ed. 747; People of the State of New Y ork v. Latrobe,

279 U.S. 421, 49 S. Ct. 377, 73 L. Ed. 776; Republic Pictures

Corp. v. Kappler, 327 U.S. 757, 66 S. Ct. 523, 90 L. Ed. 991,

rehearing denied 327 U.S. 817, 66 S. Ct. 804, 90 L. Ed. 1040;

Keating v. Public Nat. Bank, 284 U.S. 587, 52 S. Ct. 137, 76

3

L. Ed. 507; City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704, 50 S.

Ct. 407, 74 L. Ed. 1128.

W hile the above cases w ere decided under section 240

of the Judicial Code (Title 28, U.S. Code, 1946, sec. 347)

before its recent revision, the present section, as revised by

the Act of June 25, 1948 (Title 28, U.S. Code, sec. 1254(2)),

is substantially identical. See reviser’s notes to revised

section 1254. See particu la rly : Williams v. Bruffy, 96 U.S.

176, 183; King M anufacturing Co. v. Augusta, 277 U.S. 100,

104-105; Eclipse Mills Co. v. Dept, of Labor & Industry, 277

U.S. 136.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. W here S tate and City adm inistrative bodies exercis

ing legislative pow er m aintain separate bu t adm it

tedly physically equal public beach and bathhouse

facilities for Negroes and whites, does the m ainte

nance of such public recreational facilities on a segre

gated basis violate any right guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendm ent to the Constitution of the United

States?

II. If the action of State and City A dm inistrative bodies

exercising legislative power in m aintaining separate

bu t adm ittedly physically equal facilities in the field

of public recreation is violative of the Fourteenth

Amendm ent to the Constitution of the United States,

w hen and in w hat m anner m ust redress or rem edy be

afforded to the Appellees?

STATUTES' INVOLVED

Segregation on the basis of race has been the accepted

practice in M aryland for m any years. This practice, based

on the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson,

4

163 U.S. 537, has been specifically applied to the field of

public recreation. Durkee v. M urphy (1942), 181 Md. 259,

29 A. 2d 253; Law v. Mayor and City Council (D.C.-Md.

1948), 78 Fed. Supp. 346; Boyer v. Garrett (D.C.-Md. 1949),

88 Fed. Supp. 353, aff’d. (CCA 4) 183 Fed. 2d 582, cert. den.

340' U.S. 912.

The instant proceeding involves the actions of the Appel

lants, Mayor and City Council of Baltim ore and its Board

of Recreation and Parks on the municipal level, and the

Commissioners of Forests and Parks of the S tate of M ary

land, and the Superintendent of Sandy Point S tate P ark

and Beach on the S tate level, in carrying out the established

practices of the State, w ith respect to segregation on a racial

basis in recreational facilities.

The policies and practices of the Appellants have become

established over the years and have the force of law under

both S tate and Federal judicial interpretations. Durkee v.

M urphy, supra, and Boyer v. Garrett, supra. I t was con

ceded in the District Court and on appeal to the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit tha t the policies and prac

tices of the adm inistrative bodies of the S tate and City

supervising the recreational facilities involved constitute

an exercise of legislative power, in th a t the policies and

practices had become accepted as rules and regulations

w ith the force of law in the S tate of M aryland. On this

m atter, the D istrict Judge, in his opinion (123 Fed. Supp.

193, a t pages 195-196) made the following findings:

(As to the S tate of M aryland)

“* * * The facilities a t Sandy Point S tate P ark aside

from the bathing beaches and bath houses, are entirely

unsegregated, bu t the Commission has provided sep

ara te bathing beaches and bath houses for whites and

Negroes, by rules and regulations adopted by the Com-

5

mission in the exercise of its adm inistrative powers.

4: * 4*

(As to the City of Baltimore)

“ * * * Over the years the Board of Recreation and

Parks has made and modified various rules and regula

tions dealing w ith segregation in the public parks. A t

the present tim e no parks, as such, are segregated, bu t

certain recreational facilities, including the bathing

beaches, the swimming pools, some tennis courts and

fields for competitive sports, and some playgrounds and

social activities are operated on a segregated basis.”

That these regulations and rules, which w ere enforced

against the Appellees in the instant proceedings, are State

actions w ith the force of law, has been agreed and, indeed,

the present proceedings w ere brought on the prem ise tha t

they have such effect. The proceeding was designed to ob

ta in a judicial determ ination tha t the actions were consti

tutionally invalid.

Like most such well established and defined policies,

which are known and accepted by the public over a long

period of years, no explicit restatem ent of the rules and

regulations enforced as respects segregation a t public recre

ational facilities has been made in recent years. As was

pointed out by the Court of Appeals of M aryland in the

Durkee v. M urphy case, 181 Md. 259, 29 A. 2d 253 at p. 265:

“ * * * Many statu tory provisions recognize this need,

and the fact needs no illustration. ‘Separation of the

races is norm al treatm ent in this State.’ W illiams v.

Zim m erm an, 172 Md. 563, 567, 192 A. 353, 355. No ad

ditional ordinance was required therefore to authorize

the Board to apply this norm al treatm ent; the authority

would be an implied incident of the power expressly

given.”

6

In each instance, jurisdiction of the recreational facilities

herein concerned is committed to the care of the Appel

lants. As to State facilities, jurisdiction over recreational

facilities, including bathing beaches and bathhouses for the

benefit of citizens and residents of the S tate of M aryland,

is expressly committed to the Commission of Forests and

Parks of M aryland by the provisions of A rticle 66C, Sec

tions 340, et seq. of the Annotated Code of M aryland (1951

Ed.). The duty of operation, maintenance and supervision

of Sandy Point State P ark and Beach falls w ithin this ex

press supervisory authority. There is, as an adjunct to the

power to supervise, the express power to prom ulgate rules

and regulations w ith respect to use, availability and admis

sion to Sandy Point S tate P ark and Beach.

As to the municipal authorities, the Mayor and City

Council of Baltimore is expressly authorized, under Article

XIA of the Constitution of M aryland, and Section 6(19)

of the C harter and Public Local Laws of Baltimore (1949

Ed.), to establish and supervise bathing beaches, bath

houses and other recreational facilities for the benefit of

the citizens and residents of the City of Baltimore. By

the term s and provisions of Section 96 of the C harter and

Public Local Laws of Baltimore City (1849 E d.), the Board

of Recreation and Parks of Baltimore, an instrum entality

of the City, is authorized to exercise the C ity’s power of

supervision and control over the operation of bathing

beaches and recreational facilities.

The acts of the Appellants under the legislative powers

delegated to them are under attack in this case. That the

m unicipal and State agencies have expressly acted under

proper authority and in a m anner giving their actions the

force of law is apparent.

7

As w ill be hereinafter more fully set out, the D istrict

Court sustained the actions of the agencies, m unicipal and

State, on the ground tha t the objectives sought to be ob

tained w ere proper governmental objectives and the regu

lations w ere in and of themselves reasonable. In reversing

the D istrict Court, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ex

pressly found tha t the legal basis of the rules and regula

tions before the D istrict Court had been swept away by

this Court’s decision in the School Segregation Cases

(Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 492; Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 and consolidated opinion in the cases

reported a t 99 L. Ed. 653). I t is therefore apparent tha t

S tate statutes w ithin the meaning of tha t term have been

squarely ruled unconstitutional as contrary to the Four

teenth Amendm ent to the Constitution of the United States,

and, accordingly, this Court should take jurisdiction.

STATEMENT OF FACTS (Lonesome Case)

Appellants, members of the Commission of Forests and

Parks of M aryland, are empowered, under A rticle 66C,

Sections 340, et seq., of the A nnotated Code of M aryland

(1951 E d .), to establish and supervise recreational facilities,

including bathing beaches and bathhouse facilities for the

benefit of the citizens and residents of the S tate of M ary

land. Pursuant to such authority, Appellants have estab

lished and are maintaining and operating bathing and recre

ational facilities. They are charged w ith the duty of main

taining, operating and supervising Sandy Point S tate Park

and Beach as a part of their supervisory control and au

thority. They have the exclusive power to prom ulgate rules

and regulations w ith respect to use, availability and admis

sion to Sandy Point State Park and Beach. The Appellants

had, prior to Ju ly 4, 1952, by adm inistrative regulation, pro-

8

vided for racial segregation in the use of the bathhouses

and beaches a t Sandy Point.

On Ju ly 4, 1952, the Appellees sought the use of these

facilities and w ere denied admission to the South Beach a t

Sandy Point Beach and P ark and w ere directed to use the

East Beach which was set aside for the exclusive use of

Negroes.

In August, 1952, Appellees, adult and minor Negroes,

brought suit in the U.S. D istrict Court for the D istrict of

M aryland, against the Appellants and the Superintendent

of the Sandy Point S tate Park and Beach to restrain the

Appellants from operating the bathhouses and bath facil

ities a t Sandy Point State Beach on a racially segregated

basis, and for declaratory relief. Appellees alleged tha t the

facilities afforded Negroes w ere not equal to those afforded

w hites and they had been denied admission to the facilities

reserved for whites solely because of their race or color.

Appellants answered denying tha t the facilities were not

substantially equal.

On June 4, 1953, following a hearing on Appellees’ motion

for a prelim inary injunction, Judge W. Calvin Chesnut

entered an Order in which he found th a t the South Beach

facilities (for whites) w ere superior to those at East Beach

(for Negroes), and restrained Appellants from excluding

any person, solely on account of race and color, from the

facilities at South Beach.

On Ju ly 1, 1953, having improved the facilities a t East

Beach, Appellants moved to vacate the prelim inary in

junction. After a hearing, Judge Chesnut entered an Order

on Ju ly 9, 1953, in which he found as a fact tha t as of the

date of said hearing, the bathing facilities a t East Beach

w ere a t least equal to those a t South Beach, and he vacated

9

and struck out the prelim inary injunction theretofore

granted, w ith the right to the Appellees to renew their

motion at any tim e the facilities a t South Beach and East

Beach m ight not be in substantial equality.

In June, 1954, following the opinion of the Suprem e Court

in the School Segregation Cases, Appellees moved for judg

m ent on the pleadings. The case was consolidated w ith the

case of Dawson et al. v. Mayor and City Council of Balti

more, and Isaacs e t al. v. Mayor and City Council of Balti

more. On June 18, 1954, it was stipulated and agreed by

and between the parties in this case tha t the bathhouse

and beach facilities a t Sandy Point w ere physically equal

at tha t time. On Ju ly 27, 1954, after a hearing on the mo

tion for judgm ent on the pleadings, the motion was denied

by Judge Roszel C. Thomsen, United States D istrict Judge

for the D istrict of M aryland, and final judgm ents w ere en

tered pursuant thereto on August 25, 1954. The case was

appealed together w ith the Dawson case to the United

States Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit, and on March

14, 1955, following a hearing, the United States Court of

Appeals reversed the D istrict Court in a per curiam opinion.

The case is now brought by appeal to this Court.

STATEMENT OF FACTS (Dawson Case)

The Appellants, Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, a

body corporate, incorporated under the Laws of the S tate

of M aryland, have power to establish and supervise bath

ing beaches and bathhouse facilities and other recreational

facilities for the benefit of the citizens and residents of the

City pursuant to authority vested under Article XIA of

the Constitution of M aryland, Section 6(19), Charter and

Public Local Laws of Baltim ore (1949 Ed.). Appellants,

Jam es C. Anderson, et al., are members of the Board

10

of Recreation and Parks of Baltimore, an instrum entality

of the City of Baltimore, w ith authority to m aintain, super

vise and control the operation of bathing beaches and other

recreational facilities m aintained by the City pursuant to

authority vested under Section 96 of the C harter and Public

Local Laws of Baltimore City. Appellant, Sun and Sand,

Inc., a body corporate, incorporated under the Laws of the

State of M aryland, is a lessee of the Appellant, the Board of

Recreation and Parks, and operates its concession under

the supervision and control of the Board of Recreation and

Parks in order to add to the comfort, convenience and

pleasure of those persons using the facilities available at

Fort Smallwood Park.

Pursuant to municipal authority set forth in Section 96

of the Baltim ore City Charter, Appellants have established

and are m aintaining and operating bathing and recreational

facilities a t Fort Smallwood Park, a public facility which

is supported out of public funds and operated by the City

to afford recreational facilities to the citizens and residents

of Baltimore.

As a part of their supervisory control and authority, w ith

respect to Fort Smallwood Park, the Board of Recreation

and Parks of Baltimore is clothed and vested w ith the ex

clusive power to prom ulgate rules and regulations w ith

respect to the use, availability and admission to said Fort

Smallwood P ark to the persons who desire to use it.

On Ju ly 3, 1950 and August 10, 1950, Appellees sought

to use the facilities a t Fort Smallwood and w ere denied the

use of the bathing and bathhouse facilities as a result of the

policy of racial segregation pursued by the D epartm ent of

Recreation and Parks.

11

Appellees filed suit in the United, States D istrict Court

for the D istrict of M aryland and on April 6, 1951, the Court,

for the reason tha t no facilities w ere made available to the

Appellees as Fort Smallwood, enjoined the Appellants from

excluding the Appellees from those recreational facilities.

D uring the sum m er of 1951, by order of the Board of Recre

ation and Parks, Negroes exclusively used the facilities at

Fort Smallwood on certain days, while w hite persons used

them on other days.

On January 25, 1952, the Board of Recreation and Parks

form ally voted to establish separate bathhouse and beach

facilities for the exclusive use of Negroes a t Fort Smallwood

P ark and reserved the original bathhouse and beach facil

ities for the exclusive use of white persons. Separate bath

houses and beaches for Negroes w ere constructed a t Fort

Smallwood P ark in 1952 and Negroes w ere adm itted exclu

sively to such facilities and w hite persons to the original

facilities.

In accordance w ith the right reserved to the Appellees

by the Court, the Appellees renew ed the proceedings on

Septem ber 16, 1952. On June 18, 1954, following a mo

tion made by the Appellees for judgm ent on the pleadings,

a stipulation was entered into whereby it was agreed by

and between the parties tha t the separate facilities at Fort

Smallwood P ark were physically equal a t tha t time. The

case was consolidated w ith the case of Lonesome et al. v.

M axwell et al. and Isaacs v. Mayor and City Council, and

following a hearing on the motion for judgm ent on the

pleadings, the motion was denied on Ju ly 27, 1954 by Roszel

C. Thomsen, Judge of the United States D istrict Court for

the D istrict of M aryland, and final judgm ent entered. Ap-

12

pellees appealed the Lonesome and Dawson cases to the

United States Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit and the

Court of Appeals reversed the D istrict Court in a per

curiam opinion. The case is brought to this Court on appeal

from the United States Court of Appeals.

THE QUESTIONS ARE SUBSTANTIAL

This case, and the issues posed thereby, are of vital social,

economic and psychological im portance both in the S tate of

M aryland and in other States of the Union in which segre

gation of races is the accepted rule. Much of the social and

economic life of the S tate of M aryland, as well as of other

States sim ilarly situated, is founded upon the doctrine of

“separate bu t equal” facilities laid down by this Court in

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537. The social acceptance of

this decision, and the development of the social structure

of the State upon this foundation, cause the implications of

the recent decisions of this Court in the School Segregation

Cases (Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S.

483; Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 and consolidated opinion

in the case reported a t 99 L. Ed. 653) to be of great im

portance. It is necessary tha t the State and its citizens

have a clear definition not only of w hat the School Segre

gation Cases do hold, bu t it is equally im portant tha t they

be advised w hat the School Segregation Cases do not hold.

The School Segregation Cases have given rise to con

certed efforts to expand this Court’s decisions into fields of

activity not reasonably comprehended w ithin the term s of

the decisions. The decisions have furnished a springboard

from which attacks have been launched upon other areas

of S tate and municipal action not fairly w ithin this Court’s

decisions, and have caused uncertainty and indecision on

the part of State and Municipal officers caught between

13

emotional and psychological pressures from the people of

the S tate whose lives have been lived under the “separate

bu t equal” doctrine, and an earnest desire on the part of

the same S tate and Municipal officers to see tha t Constitu

tional guarantees of all persons in the State are protected.

This case, therefore, furnishes the opportunity for this

Court to fairly acquaint the officers of the municipality and

the S tate of M aryland, as well as of other States similarly

situated, w ith some guideposts to aid them in the solution

of the difficult legal, psychological and social problems

which presently confront them.

The Commission of Forests and Parks of the State of

M aryland, which operates Sandy Point State Park, under

the authority of Sections 340, ei seq., of Article 66C of the

A nnotated Code of M aryland (1951 Edition), by rules and

regulations adopted in the exercise of its adm inistrative

powers, operates the facilities a t Sandy Point on a non-

segregated basis except as respects the bathing facilities,

including the bathhouses. This is in accordance w ith the

long-standing policy which has existed in the S tate of

M aryland tha t separation of races is norm al treatm ent in

the State. W illiams v. Zim m erm an, 172 Md. 563, 567, 192

Atl. 353, 355; Durkee v. M urphy, 181 Md. 259, 29 Atl. 2d

253. There is no doubt tha t in so far as this policy was ap

plied in the past to public educational facilities, the recent

decisions in the School Segregation Cases have set the pat

te rn for the elimination of the policy in public education.

The issue presently posed to this Court, however, is w hether

the School Segregation decisions are broader in scope than

they are in language. I t is subm itted tha t in vital and sensi

tive areas, such as tha t involved in the present case, S tate

officers should not be left to grope and w onder as to the

scope and application of this Court’s decision.

14

Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, found application generally in

m any fields including, un til the recent decisions, the field

of public education. That Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, re

ceived express recognition in the field of recreational facil

ities in the State of M aryland is apparent upon exam ination

of the cases. Law v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,

(D.C.-Md. 1948), 78 Fed. Supp. 346; Boyer v. G arrett (D.C.-

Md. 1949), 88 Fed. Supp. 353, 183 Fed. 2d 582; Durkee v.

M urphy, supra; W illiams v. Zim m erm an, supra.

The issue as to the scope and ex ten t of this Court’s opin

ions in the School Segregation Cases is cleanly posed in

this case. The tria l court in these cases expressly ruled, in

view of the stipulated fact tha t the recreational facilities

in question w ere in fact physically equal, th a t this Court’s

decision in the School Segregation Cases had no application

to the field of recreational facilities. The Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit, in a per curiam opinion, held that

cases theretofore controlling, to wit, Durkee v. M urphy,

supra; Boyer v. Garrett, supra; and Plessy v. Ferguson,

supra, had been overruled and the authority of the cases

swept away by subsequent decisions of this Court. The au

thorities cited w ere: McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Re

gents, 339 U.S. 637 (G raduate School C ase); Henderson v.

U. S., 339 U.S. 816 (Railway Dining Car Case); Brown v.

Board of Education, supra; and Bolling v. Sharpe, supra

(School Segregation Cases). The Court of Appeals held

th a t these authorities, although not by term s applicable to

the field of public recreation, overruled form er express

opinions which sustained the doctrine of “separate bu t

equal” in the public recreation field. The apparent basis

of the decision was tha t in addition to tangible factors, in

any case involving “separate but equal” treatm ent of races,

psychological factors must be taken into consideration. On

15

th a t basis, and on tha t basis alone, the Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit held segregation in recreational facil

ities an im proper exercise of the police power of the State.

I t is respectfully subm itted tha t the opinions of this Court

in the School Segregation Cases are not fairly susceptible

of in terpretation to exclude in every field of S tate activity

the doctrine of “separate but equal”. If Plessy v. Ferguson,

supra, has been so narrow ed as to be totally disregarded

by virtue of im porting into every case of “separate but

equal” facilities the psychological problems which are

necessarily inherent in such situations, tha t legal doctrine

should be clearly expressed and not raised by inference

out of a decision not, by its terms, applicable.

I t would be presumptuous on the part of the Appellants

to attem pt to define to this Court w hat was intended by

the language of the Court in the School Segregation opin

ions. I t seems necessary, however, tha t the Appellants

point out tha t it is incum bent upon their S tate and Mu

nicipal officers to in terpret the sweep and application of

the opinions, and tha t a reading thereof indicates that the

“separate but equal” doctrine has not been abolished, bu t

tha t there has been exem pted from it the area of public

education. The opinions constitute a subtraction from the

doctrine and not an overruling of the doctrine.

This Court has had innum erable opportunities to sweep

aside Plessy v. Ferguson, supra. Indeed in the course of

argum ent of the public education cases, there was pre

sented argum ent and authority for discarding the entire

concept. That this Court carefully chose to leave the doc

trine, bu t subtracted from it one area to which it form erly

applied, is apparent from the decision. The express ground

for the decision in the School Segregation Cases is set down

16

in the opinion of this Court found in 347 U.S. 493, where this

Court said:

“We conclude tha t in the field of public education the

doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal.” (Em

phasis supplied.)

This ruling was expressly based on the equal protection of

the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, and

the Court declined to discuss w hether segregation violated

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

347 U.S. a t 494, 495.

In this case, the physical equality of the facilities fu r

nished is conceded. The psychological and social im pact of

segregation, which was the v ital elem ent in this Court’s

decision in the public school cases, does not appear. While

the Appellants agree w ith the language of this Court in

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497: “Classification based upon

race m ust be scrutinized w ith particular care * * never

theless, it should be noted tha t this Court made its deter

mination in the Bolling case (based upon the Due Process

Clause) dependent upon a finding tha t segregation in public

education “is not reasonably related to any proper Gov

ernm ental objective * * *.” This Court pointed out in

Koramatsu v. U. S., 323 U.S. 214, 216, “All legal restrictions

which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are

im mediately suspect. This is not to say th a t all such restric

tions are unconstitutional. I t is to say tha t the courts m ust

subject them to the most rigid scrutiny”.

The Appellants subm it tha t while it may be appropriate

to examine closely the policy of segregation in public

recreational facilities, there is in this case a proper Govern

m ental objective to be served. This Court had not gone so

17

far as to hold th a t the G overnm ental objectives upon which

the A ppellants’ action was based are not proper Govern

m ental objectives. As the Court of Appeals of M aryland

pointed out in Durkee v. M urphy, supra, one objective sub

served by racial separation in public recreational facilities

is the avoidance of any possible conflicts which m ight arise

from racial antipathies. This statem ent is not intended to

defend or condone the existence of such a state of mind, bu t

ignoring the facts w ill not aid in solution of the problem.

H um an relations, which have been brought into the field

of the law w here segregation m atters are concerned, do not

always respond exactly as the informed, intelligent ele

m ent of society m ight th ink proper. W hile we decry the

existence of the fact, this is different from ignoring the

existence of the fact. The prevention of race conflict by

proper S tate action in fields w here the “separate bu t equal”

doctrine applies w ill do much to aid in the acceptance of

non-discrimination in those fields w here constitutional

guarantees require the abandonm ent of the “separate but

equal” theory.

Elimination of segregation in public education, peace

fully and properly handled, w ill doubtless do much to help

in the solution of this m atter. The fact is, however, tha t it

is the duty of the State and its municipalities to m aintain

tranquil relations so tha t non-discrimination in the schools

m ay prosper under the most favorable possible circum

stances. Social change comes slowly, and precipitous ac

tion in fields not w ithin the scope of this Court’s ruling

should not be perm itted to occur on the basis of an in

ference, w ith possible harm ful consequences to the end to

be attained under the form er opinions.

A nother objective sought to be obtained is tha t public

facilities furnish the greatest good to the greatest num ber

18

of citizens of the State, both Negro and white. Under the

social structure, and a t the present stage of social develop

m ent in the State, w hites and Negroes can be tte r use and

more enjoy recreational facilities w ith members of their

own race than in mixed groups. This objective, to provide

facilities for the greatest num ber and in accordance w ith

the wishes of the greatest num ber, is not unreasonable.

Obviously, the State and City cannot seek to attain the end

by a means which works a deprivation of constitutional

rights. We submit, however, th a t feeling and emotion in

the S tate of M aryland, and doubtless in other Southern

States, ru n higher in inter-m ixing of races in bathing facil

ities than possibly any other field of hum an relations ex

cept miscegenation.

M aryland has been in the forefront of the States seeking

to level racial differences. The State has moved steadily

ahead in the accomplishment of the desired end of break

ing down im proper barriers based on race. I t would be

tragic, however, to undo the enlightened and progressive

approach evidenced by the S tate of M aryland by forcing

the issue w here the objectives are proper in light of the

circumstances. Here, the State and City have reasonable

cause to believe tha t consequences undesirable to both

Negro and w hite citizens may arise out of integrated recre

ational facilities. To avoid and prevent those consequences,

and to perm it the development of the S tate and City pro

grams on logical bases, the State should certainly be ac

corded the opportunity to take those steps reasonably de

signed to prevent inter-racial tension and make available

its recreational facilities to the largest num ber of its cit

izens. Here, reasonable Governmental objectives exist, im

plem ented by reasonable regulations, and they should not

be upset.

19

There is here involved not only a question of w hether

the S ta te’s statutes should be denounced as violative of con

stitutional guarantees, but also the nature of the relief

which should be granted. As this Court dem onstrated by

its approach in the School Segregation Cases, moderation

and steady progress are more desirable than abrupt change

which may redound only to the in jury of citizens of both

races. The issue has also been posed in this case w hether,

if this Court deems the School Segregation Cases applicable

to public recreation, the rem edy should be immediate

desegregation or some other form of relief under the equity

jurisdiction of the local courts, who are fam iliar w ith con

ditions as they exist in the State. We subm it tha t no fu r

th e r authority to sustain the desirability of this sensible

approach need be cited than this Court’s second opinion in

the School Segregation Cases. (Brown v. Board of Educa

tion of Topeka etc., 99 L. Ed. 653). Timing is of vital im

portance to the State, the City and their officers. Lack of

knowledge by such officers as to the m anner of effectuating

desegregation, if such be necessary, would be dangerous.

Certainty, and assurance tha t they are acting under and

pursuant to law, will do much to aid in the solution of the

knotty problem of how to carry out any decree of this

Court, if desegregation of recreational facilities should be

required.

We, therefore, respectfully submit tha t the questions here

presented could not be more vital, significant and substan

tial, and tha t the cases should, accordingly, be heard and

resolved by this Court.

20

ALTERNATE CERTIORARI APPLICATION

Appellants are also applying for certiorari w ith respect

to the same judgm ent. They believe tha t the Suprem e

Court of the United States has jurisdiction over this appeal.

If, however, in this they are mistaken, it is requested tha t

w rit of certiorari be granted. Bradford Electric L ight Co.

v. Clapper, 284 U.S. 221, 52 S. Ct. 118, 76 L. Ed. 254.

Respectfully submitted,

C. F erd in a n d S ybert ,

A ttorney G eneral of Maryland,

N o r m a n P. R a m s e y ,

D eputy A ttorney G eneral of M aryland,

A m b r o se T . H a r t m a n ,

Asst. A ttorney G eneral of M aryland,

T h o m a s N . B id d iso n ,

City Solicitor of Baltimore,

E d w in H a r la n ,

D eputy City Solicitor of Baltimore,

H ugo R ic c iu t i ,

F r a n c is X. G allagher ,

Assistant City Solicitors,

A ttorneys for Appellants.

21

APPENDIX A

United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

No. 6903

Robert M. Dawson, Jr., et al.,

Appellants,

versus

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City, James C.

Anderson, President, e t al.,

Appellees.

No. 6904

M ilton Lonesome, et al.,

Appellants,

versus

R. Brooke M axwell, Chairman, Bernard I. Gonder, H. Lee

Hoffman, Sr., J. Miles Lankford, J. W ilson Lord, consti

tu ting the Commissioners of Forests and Parks of M ary

land, et al., Appellees.

Appeal from the United States D istrict Court for

the D istrict of Maryland, at Baltimore

(A rgued January 11, 1955. Decided March 14, 1955.)

Before P a rk er , Chief Judge, and S oper and D o b ie , Circuit

Judges.

P er C u r ia m :

These appeals w ere taken from orders of the D istrict

Court dismissing actions brought by Negro citizens to ob-

22

tain declaratory judgm ents and injunctive relief against the

enforcem ent of racial segregation in the enjoym ent of pub

lic beaches and bathhouses m aintained by the public au

thorities of the State of M aryland and the City of Baltim ore

a t or near tha t city. N otw ithstanding prior decisions of the

Suprem e Court of the United States striking down the prac

tice of segregation of the races in certain fields, the D istrict

Judge, as shown by his opinion, (123 F. Supp. 193) did not

feel free to disregard the decision of the Court of Appeals of

M aryland in Durkee v. M urphy, 181 Md. 259, and the de

cision of this court in Boyer v. Garrett, 4 Cir., 183 F. 2d

582. Both of these cases are directly in point since they re

lated to the field of public recreation and held, on the au

thority of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, tha t segregation

of the races in athletic activities in public parks or play

grounds did not violate the 14th Amendm ent if substanti

ally equal facilities and services w ere furnished both races.

Our view is tha t the authority of these cases was swept

away by the subsequent decisions of the Suprem e Court. In

M cLaurin v. Okla. State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 the Su

prem e Court had held tha t it was a denial of the equal

protection guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendm ent for

a state to segregate on the ground of race a student who had

been adm itted to an institution of higher learning. In Hen

derson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816, segregation on the

ground of race in railway dining cars had been held to be an

unreasonable regulation violative of the provisions of the

In tersta te Commerce Act. Subsequently, in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483, segregation of w hite and col

ored children in the public schools of the state was held to

be a denial of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amend

ment; and in Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, segregation

in the public schools of the D istrict of Columbia was held to

be violative of the due process clause of the F ifth Amend

ment. In these cases, the “separate bu t equal” doctrine

adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson, was held to have no place in

modern public education.

23

The combined effect of these decisions of the Supreme

C ourt is to destroy the basis of the decision of the Court of

Appeals of M aryland in Durkee v. M urphy, and the decision

of this court in Boyer v. Garrett. The Court of Appeals of

M aryland based its decision in D urkee v. M urphy on the

theory th a t the segregation of the races in the public parks

of Baltim ore was w ithin the power of the Board of P ark

Commissioners of the City to make rules for the preserva

tion of order w ithin the parks; and it was said tha t the

separation of the races was norm al treatm ent in M aryland

and tha t the regulation before the court was justified as an

effort on the part of the authorities to avoid any conflict

w hich m ight arise from racial antipathies.

I t is now obvious, however, tha t segregation cannot be

justified as a means to preserve the public peace merely be

cause the tangible facilities furnished to one race are equal

to those furnished to the other. The Suprem e Court ex

pressed the opinion in Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 492 to 494, tha t it m ust consider public education in

the light of its full development and its present place in

American life, and therefore could not tu rn the clock back

to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was w ritten, or base its

decision on the tangible factors only of a given situation,

bu t m ust also take into account the psychological factors

recognized a t this time, including the feeling of inferiority

generated in the hearts and minds of Negro children, when

separated solely because of the ir race from those of similar

age and qualification. W ith this in mind, it is obvious tha t

racial segregation in recreational activities can no longer

be sustained as a proper exercise of the police power of the

State; for if tha t power cannot be invoked to sustain racial

segregation in the schools, w here attendance is compulsory

and racial friction may be apprehended from the enforced

commingling of the races, it cannot be sustained w ith re

spect to public beach and bathhouse facilities, the use of

which is entirely optional.

The decision in Bolling v. Sharpe also throw s strong

light on the question before us for it admonishes us tha t in

24

approaching the solution of problems of this kind we should

keep in mind the ideal of equality before the law which

characterizes our institutions. The court said (pp. 499-

500):

“Classifications based solely upon race m ust be scru

tinized w ith particular care, since they are contrary to

our traditions and hence constitutionally suspect. As

long ago as 1896, this Court declared the principle ‘tha t

the Constitution of the United States, in its present

form, forbids, so far as civil and political rights are

concerned, descrim ination by the G eneral Government,

or by the States, against any citizen because of his

race.’ And in Buchanan v. W arley , 245 U. S. 60, the

Court held tha t a statu te which lim ited the righ t of a

property ow ner to convey his property to a person of

another race was, as an unreasonable discrimination,

a denial of due process of law.

“Although the Court has not assumed to define

‘liberty ’ w ith any great precision, tha t term is not con

fined to m ere freedom from bodily restraint. L iberty

under law extends to the full range of conduct which

the individual is free to pursue, and it cannot be re

stricted except for a proper governmental objective.

Segregation in public education is not reasonably re

lated to any proper governm ental objective, and thus it

imposes on Negro children of the D istrict of Columbia

a burden tha t constitutes an arb itrary deprivation of

| the ir liberty in violation of the Due Process Clause.”

Reversed.

25

APPENDIX A

United States D istrict Court

District of Maryland

Filed Ju ly 27, 1954

Civil Action—No. 5965

M ilton Lonesome, e t al.

vs.

R. Brooke M axwell, et al.

Civil Action—No. 5847

Robert M. Dawson, Jr., e t al.

vs.

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, et al.

Civil Action—No. 6879

Charles H. Isaacs, et al.

vs.

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, et al.

T h o m s e n , D istrict Judge—

The motions for judgm ents on the pleadings in these

th ree cases raise a single legal question: Does segregation

of the races by the State of M aryland and the City of Balti

m ore a t public bathing beaches, bathhouses and swimming

26

pools deny plaintiffs any rights protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

No. 5965

In this case, filed in August, 1952, plaintiffs, adult and

minor Negroes, brought suit against the Commissioners of

Forests and Parks of the S tate of M aryland, and the Super

intendent of Sandy Point State P ark and Beach, to restrain

defendants from operating the bathhouses and bathing fa

cilities a t Sandy Point S tate P ark on a segregated basis.

Plaintiffs alleged tha t the facilities afforded Negroes w ere

not equal to those afforded w hites and tha t they had been

denied admission to the facilities reserved for w hites solely

because of their race or color. Defendants answered, deny

ing tha t the facilities w ere not substantially equal.

On June 4, 1953, following a hearing on plaintiffs’ motion

for a prelim inary injunction, Judge Chesnut entered an

order in which he found th a t the South Beach facilities

(for w hites) w ere superior to those a t East Beach (for

Negroes), and restrained defendants from excluding any

person, solely on account of race and color, from the facil

ities a t South Beach. On Ju ly 1, 1953, having improved the

facilities a t East Beach, defendants moved to vacate the

prelim inary injunction. A fter a hearing Judge Chesnut

entered an order on Ju ly 9, 1953 in which he found as a

fact tha t as of the date of said hearing the bathing facilities

at East Beach w ere a t least equal to those at South Beach,

and vacated and struck out the prelim inary injunction

theretofore granted, w ith the right to plaintiffs to renew

the ir motion a t any time the facilities a t South Beach and

East Beach may not be in substantial equality.

No. 5847

In this case, filed in May, 1952, plaintiffs, adult and minor

Negroes, are suing the City of Baltimore, its Board of

Recreation and Parks, the D irector of the Bureau of Recre

ation and Parks, and Sun and Sand, Inc., a corporation

which operates a concession under the supervision and con-

27

tro l of tha t Board a t Fort Smallwood Park, to restrain de

fendants from operating the bathhouses and bathing facil

ities a t Fort Smallwood P ark on a segregated basis, alleging

tha t the facilities afforded Negroes are not equal to those

afforded whites, and tha t they w ere denied admission to

the facilities reserved for w hites solely because of their

race or color. Defendants answered, denying tha t the facil

ities are not substantially equal.

No. 6879

In this case, filed in September, 1953, plaintiffs seek to

restrain defendants from operating on a segregated basis

any swimming pool established, operated and m aintained

by the City of Baltimore. Defendants are the City, its Board

of Recreation and Parks, the Director of the D epartm ent of

Recreation and Parks, and the Superintendent of Parks and

Pools. One of the plaintiffs is white; all the rest of the plain

tiffs are Negroes. Plaintiffs allege tha t the bathing facilities

w hich defendants provide for Negroes are not equal to

those provided for w hite persons. Plaintiffs also allege tha t

defendants, by operating the facilities on a segregated basis,

deny plaintiffs the right to associate w ith their friends!

Defendants answered tha t the facilities afforded Negroes

are substantially equal to those afforded w hite persons, and

th a t any denial of use of the bathing facilities which plain

tiffs may have experienced was a resu lt of the enforcement

of rules and regulations establishing a policy of segregation

in the use of bathing facilities in the public parks°of Balti

more City.

In all of the cases fu rther proceedings w ere delayed pend

ing the decision of the Supreme Court in the school segre

gation cases.

Several days after the filing of the opinion in Brown v .

Board of Education, (May 17, 1954) 347 IT. S. 483, counsel

for plaintiffs asked this Court to set these three cases for

prom pt hearing. Counsel for defendants offered no objec

tion, and the court set the hearings for June 22, 1954 There

after, on May 29, 1954, plaintiffs filed a motion for judg-

28

m ent on the pleadings in each of the th ree cases, asserting

in each case: (1), tha t the com plaint alleges a violation of

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights in tha t defendants require

racial segregation in the facilities which are the subject

of this action; (2) th a t the answ er adm its tha t defendants

exclude plaintiffs from these state- (c ity ) -operated facilities

to which they sought admission, solely because of their

race; and (3) tha t such racial segregation violates the

Fourteenth Amendm ent to the United States Constitution.

The respective defendants filed answers to these motions,

denying tha t their actions violate the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

A t a pre-trial conference counsel for all parties in No.

5847 ( the Fort Smallwood Bathing Beach case) stipulated

“tha t the separate facilities in question herein are physi

cally equal a t this time.” A sim ilar stipulation was filed in

No. 5965 (the Sandy Point Bathing Beach case). Counsel

in No. 6879 (the case involving the city swimming pools)

stipulated “tha t the only question to be argued a t this hear

ing is the broad question of the right of the City to segre

gate the races in public swimming pools. Any other ques

tion raised by the pleadings is reserved for argum ent a t

some fu tu re time, if necessary.”

Sandy Point S tate P ark is operated adm inistratively by

the Commission of Forests and Parks of the State of M ary

land under the authority of Sec. 340 et seq., Article 66C,

Annotated Code of M aryland (1951 E d .). The law does not

require the Commission to operate a bathing beach in a

segregated or non-segregated m anner; nor indeed does it

require the Commission to operate any bathing beach a t

all. The facilities a t Sandy Point State Park, aside from the

bathing beaches and bathhouses, are entirely unsegregated,

bu t the Commission has provided separate bathing beaches

and bathhouses for w hites and Negroes, by rules and regu

lations adopted by the Commission in the exercise of its

adm inistrative powers. It was stated a t the hearing, w ith

out objection or contradiction, tha t the bathhouses and

bathing beaches at Sandy Point are the only segregated

29

facilities under the control of the Commission of Forests

and Parks of the State of M aryland.

Section 6, Sub-section 19, Baltimore City C harter grants

the Mayor and City Council of Baltim ore power to estab

lish, m aintain, control and regulate parks, squares and m u

nicipal recreational facilities; Section 96 of said Charter

gives the Board of Recreation and Parks authority to regu

late and control the use of recreational facilities in the pub

lic parks of Baltimore. N either the Constitution of M ary

land, the City Charter, nor any statu te or ordinance re

quires the Board of Recreation and Parks to operate the

bathing, swimming and other recreational facilities on a

segregated or unsegregated basis. Over the years the Board

of Recreation and Parks has made and modified various

rules and regulations dealing w ith segregation in the public

parks. A t the present time no parks, as such, are segre

gated, bu t certain recreational facilities, including the bath

ing beaches, the swimming pools, some tennis courts and

fields for competitive sports, and some playgrounds and

social activities are operated on a segregated basis. Effec

tive Ju ly 10, 1951, the Board of Recreation and Parks set

aside for interracial play certain athletic and recreational

facilities in a num ber of parks. Counsel agreed a t the hear

ing tha t a list of these facilities be made a part of the record,

and they are referred to la ter in this opinion.

The authority of the respective boards to make the regu

lations which are challenged in these cases is supported by

D urkee v. M urphy, ( 1942), 181 Md. 259, a case involving the

segregation of w hite and Negro players on municipal golf

courses. In tha t case Chief Judge Bond, after referring to

the relevant sections of the Baltim ore City C harter of 1938

(not substantially different from those of the present Char

te r of 1946) which conferred powers upon the Park Board

to make rules and regulations, said:

“And these provisions must, we conclude, be con

strued to vest in the Board the power to assign the golf

courses to the use of the one race and the other in an

effort to avoid any conflict which might arise from

30

racial antipathies, for th a t is a common need to be faced

in regulation of public facilities in M aryland, and m ust

be implied in any delegation of pow er to control and

regulate. There can be no question that, unreasonable

as such antipathies may be, they are prom inent sources

of conflict, and are always to be reckoned with. Many

statutory provisions recognize this need, and the fact

needs no illustration. ‘Separation of the races is norm al

trea tm ent in this state.’ W illiam s v. Zim merm an, 172

Md. 583, 567, 192 A. 353, 355. No additional ordinance

was required therefore to authorize the Board to ap

ply this normal treatm ent; the authority would be an

implied incident of the power expressly given.” 181

Md. at 265.

Plaintiffs question w hether the statem ent “separation of

the races is norm al trea tm ent in this sta te” is still true, bu t

do not question the power of the respective boards to make

such regulations except as they m ay be prohibited by the

Fourteenth Amendm ent to the Constitution of the United

States.

The court has consistently held, following Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, tha t segregation of races w ith re

spect to recreational facilities afforded by the State for

its citizens is w ithin the constitutional exercise of the police

power of the State, provided the separate facilities afforded

different races are substantially equal. Law v. Mayor &

City Council of Baltimore, (D. C. Md. 1948) 78 F. Supp.

346; Boyer v. Garrett, (D. C. Md. 1949) 88 F. Supp. 353.

Boyer v. Garrett was appealed to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which affirmed this

court, 183 F. 2d 582, saying:

“The contention of plaintiffs is that, notw ithstanding

this equality of treatm ent, the ru le providing for segre

gation is violative of the provisions of the federal Con

stitution. The D istrict Court dismissed the complaint

on the authority of Plessy v. Ferguson, 183 U. S. 537,

16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed. 256; and the principal argu-

31

m ent made on appeal is tha t the authority of Plessy v.

Ferguson has been so weakened by subsequent deci

sions th a t we should no longer consider it as binding.

We do not think, however, tha t we are a t liberty thus

to disregard a decision of the Suprem e Court which

th a t court has not seen fit to overrule and which it ex

pressly refrained from reexamining, although urged

to do so, in the very recent case of Sw eatt v. Painter,

70 S. Ct. 848. I t is for the Suprem e Court, not us, to

overrule its decisions or to hold them outmoded.”

Certiorari was denied by the Supreme Court, 340 U. S.

912.

That decision of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Cir

cuit is binding on this court in this case unless the basis for

the decision of the Court of Appeals has been swept away

by subsequent decisions of the Suprem e Court.

Brown v. Board of Education certainly reexam ined the

decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. Did it overrule th a t de

cision, or establish any principle which makes it clear tha t

the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson

may no longer be applied to authorize the provision by a

state of separate but equal recreational facilities? If it did,

this court m ust follow the Suprem e Court ra ther than the

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. On the other hand,

if Brown v. Board of Education, aside from its obvious

effect in the field of education, m erely shows which way the

wind is blowing, and foretells the ultim ate and perhaps

im m inent elimination of the “separate bu t equal” doctrine

in recreation, transportation and other fields besides edu

cation, this court is still bound by the decision of the Fourth

Circuit in Boyer v. Garrett.

It is therefore necessary to analyze the opinion in Brown

v. Board of Education and to try to determine, w ith such

additional light as may be throw n on the m atter by other

decisions of the Supreme Court, w hether Brown v. Board

of Education was intended to wipe out the “separate but

equal” doctrine entirely.

32

The opinion in Brown v. Board of Education discussed

the history of the Fourteenth Amendm ent w ith respect to

segregated schools; observed tha t in the first cases in the

Suprem e Court construing the Fourteenth A m endm ent the

Court in terpreted it as proscribing all state imposed dis

crim ination against the Negro race; and noted the appear

ance of the “separate but equal doctrine” in Plessy v. Fer

guson and the subsequent history of tha t doctrine in the

Supreme Court. The Court stated tha t its decision could

not tu rn on m erely tangible factors, bu t tha t the Court m ust

look to the effect of segregation itself on public education.

The Court noted a num ber of factors which show th a t edu

cation is perhaps the most im portant function of state and

local governments. Reference will be made to these factors

la ter in this opinion. The Court stated tha t the question

presented was: “Does segregation of children in public

schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical

facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors m ay be equal, deprive

the children of the m inority group of equal educational op

portunities?” (347 U.S. 493) Answering tha t question in

the affirmative, the court said:

“To separate them from others of sim ilar age and

qualifications solely because of the ir race generates a

feeling of inferiority as to the ir status in the com

m unity tha t may affect their hearts and minds in a way

unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separa

tion on the ir educational opportunities was well stated

by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which never

theless felt compelled to ru le against the Negro plain

tiffs :

“ ‘Segregation of w hite and colored children in pub

lic schools has a detrim ental effect upon the colored

children. The impact is greater when it has the sanc

tion of the law; for the policy of separating the races

is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the

Negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motiva

tion of a child to learn. Segregation w ith the sanction

of law, therefore, has tendency to re tard the educa

tional and m ental development of Negro children and

33

to deprive them of some of the benefits they would re

ceive in a racially integrated school system.’

W hatever may have been the ex ten t of psycho

logical knowledge at the tim e of Plessy v. Ferguson,

th is finding is amply supported by modern authority!

Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this

finding is rejected.

“We conclude tha t in the field of public education

the doctrine of ‘separate bu t equal’ has no place.

Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

Therefore, we hold tha t the plaintiffs and others simi

larly situated for whom the actions have been brought

are, by reason of the segregation complained of, de

prived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes

unnecessary any discussion w hether such segregation

also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

A m endm ent.” 347 U.S. at 494, 495.

W hat “language in Plessy v. Ferguson” was the Suprem e

Court rejecting as contrary to “this finding,” i.e. the finding

in the Kansas case quoted by the Suprem e Court in the

foregoing ex tract from its opinion?

The heart of Plessy v. Ferguson lies in the following para

graph, which was quoted by Judge Chesnut as the basis for

his decision in Boyer v. Garrett:

“The object of the am endm ent was undoubtedly to

enforce the absolute equality of the two races before

the law, but in the nature of things it could not have

been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color,

or to enforce social, as distinguished from political

equality, or a commingling of the two races upon term s

unsatisfactory to either. Laws perm itting, and even

requiring, their separation in places w here they are

liable to be brought into contact do not necessarily im

ply the inferiority of either race to the other, and have

been generally, if not universally, recognized as w ith

in the competency of the state legislatures in the ex-

34

ercise of the ir police power. The most common in

stance of this is connected w ith the establishm ent of

separate schools for w hite and colored children, which

has been held to be a valid exercise of the legislative

pow er even by courts of S tates w here the political

rights of the colored race have been longest and most

earnestly enforced.” 163 U.S. a t 544.

It is clear th a t Brown v. Board of Education overruled

the implied approval of segregation in the field of educa

tion contained in the foregoing quotation from Plessy v.

Ferguson. I t appears also th a t the Supreme Court now dis

agrees w ith the general statem ent in Plessy v. Ferguson

th a t “laws perm itting, and even requiring, the ir separation

in places w here they are liable to be brought into contract

do not necessarily im ply the inferiority of either race to the

other.” The question of w hat m atters fall w ithin the field

of “social equality” has never been clear. Brown v. Board

of Education indicates tha t certain claimed rights which

m ay have been heretofore regarded as social m atters should

now be considered civil rights entitled to constitutional pro

tection. But has the “separate bu t equal” doctrine been

completely overruled? May it still be applied in the field of

transportation? May it still be applied in the field of recrea

tion? Brown v. Board of Education did not expressly over

rule all of Plessy v. Ferguson nor say tha t the “separate but

equal” doctrine may not be applied in the fields of trans

portation or recreation. This court m ust consider the force

and extent of the implications of the decision in Brown v.

Board of Education.

Counsel for plaintiffs in the cases a t bar have noted tha t

the psychological and sociological authorities cited by the

Suprem e Court in Brown v. Board of Education deal w ith

all fields of segregation and not alone w ith segregation in

education. I t is true tha t the authorities cited would have

supported a broader conclusion than the conclusion stated

by the Court. The narrowness of the actual decision may

have been due to the policy of the Suprem e Court to decide

constitutional questions only when necessary to the dis-

35

position of the case a t hand, and to draw such decisions as

narrow ly as possible. Sw eatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 631;

Rescue A rm y v. Municipal Court, 331 U. S. 549, and cases

cited therein. On the other hand it may be tha t the decision

was worded as it was because the Suprem e Court did not

intend to ru le tha t the “separate but equal” doctrine can no

longer be applied in fields other than education.

Let us see w hat light is throw n on the m atter by decisions

of the Suprem e Court in cases decided after Brown v. Board

of Education. On May 24, 1954, the Suprem e Court refused

certiorari in a num ber of cases involving rights of Negroes.

Only one of these cases dealt w ith recreation, namely, Beal

v. Holcombe (5 Cir.) 193 F. 2d 384. In th a t case a munici

pal corporation had excluded Negroes from three golf

courses, located in parks set aside for w hite people. The

m unicipality provided no golf courses for Negroes. The

Court of Appeals for the F ifth Circuit held tha t this action

violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, stating tha t it was in full accord w ith the rea

sons given and the results reached in Law v. Mayor and

C ity Council, (D. C. Md. 1948) 78 F. Supp. 346, which was

based upon the “separate but equal” doctrine.

On the same day the Suprem e Court entered an order in

three cases in which rights of Negroes had been denied be

low. The Court said, per curiam : “The petitions for w rit of

certiorari are granted. The judgm ents are vacated and the

cases are rem anded for consideration in the light of the

segregation cases decided May 17, 1954, Brow n v. Board of

Education, etc., and conditions tha t now prevail.” 347 U. S.

971. Two of these cases involved education and are clearly

controlled by Brown v. Board of Education. The th ird case,

M uir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association, involved

th e equality of the recreational facilities afforded Negroes

and w hite persons by the City of Louisville, and the ex

clusion of Negroes from an am phitheatre for theatrical

productions located in a city park reserved for w hite people.

The tria l court found tha t the failure to provide for Negroes

facilities for golf and fishing, which w ere provided for

36

whites, was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. But

, tria l court also held tha t the city violated no rights of the

plaintiff by leasing the am phitheatre to a non-profit organ

ization which excluded Negroes from the performances

which it sponsored unless the city denied equal opportuni

ties to Negro organizations to lease the am phitheatre. (W.

D. Ky. 1951) 182 F. Supp. 525. The appeal involved only

the second point, and the Court of Appeals for the S ixth

Circuit affirmed the decision of the D istrict Court, 202 F.

2d 275. The phrase “conditions tha t now prevail” in the

per curiam order of the Suprem e Court in the M uir case

probably refers to the fact tha t the lease involved in th a t

case had expired and therefore the case m ay have become

moot. Counsel in the cases a t bar suggested no other sig

nificant meaning for the phrase “conditions th a t now pre

vail.”

W hat light does Brown v. Board of Education throw on

the proper decision of the M uir case? The real question in

tha t case was w hether the facility was public or private. If

it was a public facility, plaintiffs w ere clearly entitled to

win on the state of the law before Brown v. Board of Edu

cation.

The order of May 24, 1954 in the M uir case had a p re

cedent in Rice v. Arnold, 340 U. S. 848. In tha t case the City

of Miami operated a public golf course, perm itting Negroes

to play one day a week and whites to play on other days.

The Suprem e Court of Florida approved this action, Rice v.

Arnold, 45 So. 2d 195. The Suprem e Court of the United

States entered the following per curiam decision:

“Rice v. Arnold, Superintendent of Miami Springs

Country Club. On petition for w rit of certiorari to the

Suprem e Court of Florida. P er Curiam: The petition

for w rit of certiorari is granted. The judgm ent is va

cated and the cause is rem anded to the Suprem e Court

of Florida for reconsideration in the light of subsequent

decisions of this Court in Sw eatt v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629, and M cLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents 339

U. S. 637.”

37

On remand, the Suprem e Court of Florida said: “We

should announce and adhere to our considered judgm ent

as to the meaning of the Constitution and its application

to a particular factual situation so long as i t is supported

by earlier decisions and is not in conflict w ith more recent

holdings either directly or by necessary inference.” I t

found th a t the Sw eatt and M cLaurin cases w ere not con

trolling in the field of recreation, bu t vacated its form er

judgm ent and again affirmed the decision of the Circuit

Court, 54 So. 2d 114, including among the grounds for

affirmance this tim e certain procedural m atters, which

caused the Suprem e Court to refuse certiorari, 342 U. S.

946.

I t is clear tha t the Supreme Court fe lt in 1950 tha t its

decisions in Sw eatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, and feels now th a t its decisions in Brown v.

Board of Education and Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497,

throw some light on the proper decision of recreation cases.

B ut the Suprem e Court has not held that the “separate but

equal” doctrine m ay no longer be applied in th e field of

recreation; it has left the m atter for the lower courts to de

term ine “in the light of” its recent decisions.