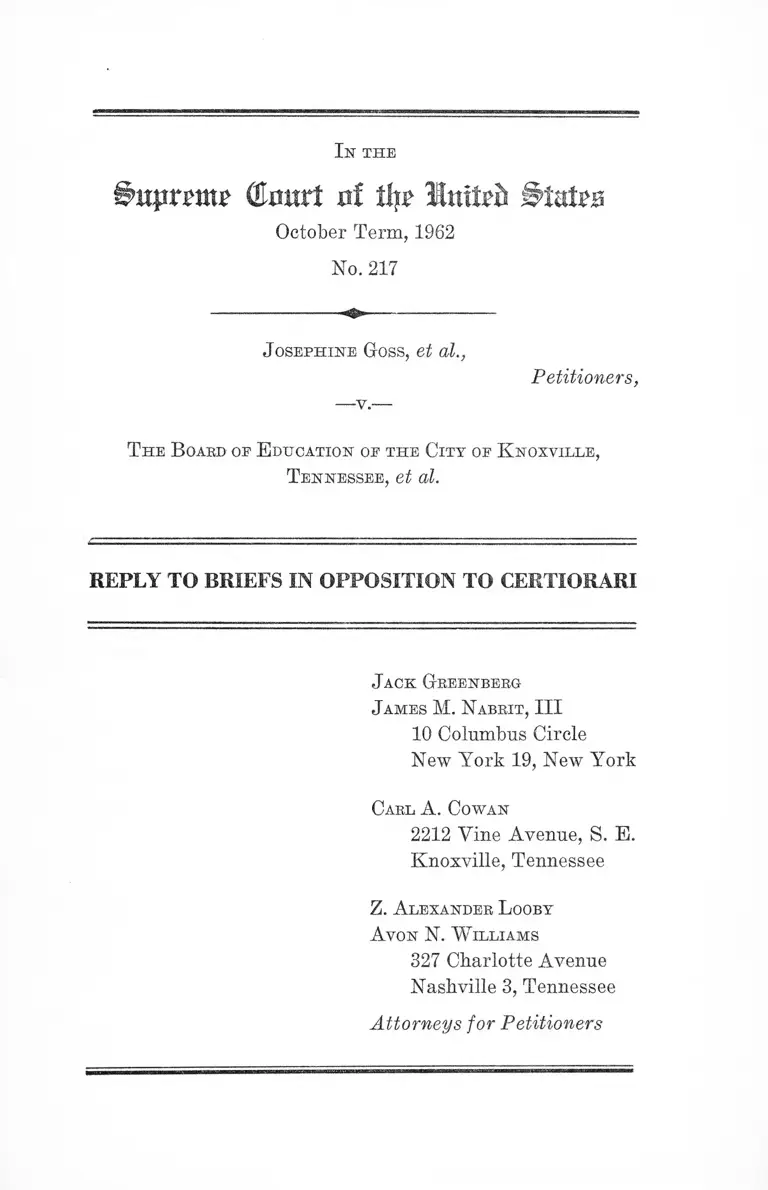

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Reply to Briefs in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Reply to Briefs in Opposition to Certiorari, 1962. 7c686fe4-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/25ebfb51-3463-40d4-8b99-0ecbbb282af5/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-reply-to-briefs-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

fmpr£iit£ ( to r t nt tlj? Untied Bu Ub

October Term, 1962

No. 217

J o s e p h in e G oss, et al.,

-v.-

Petitioners,

T h e B oard of E ducation oe t h e C it y of K n o x v ille ,

T e n n e s s e e , et al.

REPLY TO BRIEFS IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N a bbit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Carl A. C ow an

2212 Vine Avenue, S. E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. A lexander L ooby

A von N. W illia m s

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

I n t h e

jshtprm? ©Burt nf tip United Bm&B

October Term, 1962

No. 217

------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------—

J o s e p h in e G oss, et al.,

-v.-

Petitioners,

T h e B oard of E ducation of t h e C ity of K n oxville ,

T e n n e s s e e , et al.

REPLY TO BRIEFS IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Petitioners respectfully direct the attention of the Court

to a recent decision which, it is believed, further supports

the petitioners’ argument that a writ of certiorari should

be granted.

On September 17, 1962, the United States Supreme Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit decided the case of

Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Va.,

4th Cir. No. 8638. The majority and dissenting opinions in

that case are appended hereto.

On September 26, 1962, the Fourth Circuit, sitting en

banc, entered an order recalling its mandate and tempo

rarily staying it to allow the Charlottesville school authori

ties to apply for a writ of certiorari and to seek a further

stay in this Court. The Court expressly indicated that the

stay was intended to continue only until the Supreme Court

or a Justice thereof acts upon a further application for a

stay. In that order the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit expressly stated its view that the issue involved

2

should be determined by this Court stating, inter alia:

“This Court respectfully ventures to suggest that these

issues merit review, especially.”

As a result of the decision in the Dillard case, there is

now a conflict between the rulings of the Fourth and Fifth

Circuits, on the one hand, and the decision of the Sixth

Circuit in the Goss and Maxwell cases involved in this

petition, on the other hand. Furthermore, the Dillard deci

sion emphasizes the fact that the issue involved is of wide

spread public importance and merits plenary review in this

Court.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

C arl A. C ow an

2212 Vine Avenue, S. E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. A lexander L ooby

A von N. W illia m s

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

OPINION

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

F oe t h e F o u r th C ir c u it

No. 8638

D oris D illard, et al.,

Appellants,

-v .-

T h e S chool B oard oe t h e C ity o f C h a rlo ttesv ille ,

V irginia, et al.,

a n d

Appellees,

T h e S chool B oard of t h e C ity of C h a rlo ttesv ille ,

V ir g in ia , et al.,

Appellants,

— v.—

C arolyn M arie D obson , et al.,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Virginia, at Charlottesville. John Paul,

District Judge.

(Reargued July 9, 1962 Decided September 17, 1962.)

B e f o r e :

S o belo ff , Chief Judge, a n d

H a y n sw o r th , B orem an , B ryan and J. S pe n c e r B e l l ,

Circuit Judges, sitting en banc.

4

S. W. T u c k er (Henry L. Marsh, III, Otto L.

Tucker, Jack Greenberg and James M.

Nabrit, III, on brief), for Appellants and

Cross-Appellees, and

J o h n S. B a ttle , J r . (Battle, Neal, Harris, Minor

& Williams, on brief), for Appellees and

Cross-Appellants.

P er C u ria m :

This appeal was first heard by a panel consisting of

Senior Judge Soper, Chief Judge Sobeloff and Circuit

Judge Boreman. An opinion was prepared by Judge Soper,

but before it was announced by the court a hearing en banc

was ordered, in which the five active judges of the court

sat, but Judge Soper did not participate.

Judge Soper’s opinion, which Sobeloff, Boreman and

Bell, JJ., adopt as the opinion of the court, is as follows:

Cross-appeals again bring to this court questions arising

in the administration of the public schools of Charlottes

ville, Va., with respect to the assignment of white and

Negro children in the elementary and high school grades.*

Our most recent decision in Dodson v. School Board of the

City of Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d 439 (1961), outlines the

stejis that the School Board had then taken toward the in

tegration of the races in the schools and the plan of oper

ation for the school year 1960-1961. The plan involved the

division of the City into six geographical districts, each

of which was served by one of the elementary schools, to

wit: Jefferson, Venable, Johnson, Burnley-Moran, Clark

and McGuffey. It was provided that each child should

attend the school located in the zone of his residence and

* The opinion of the District Court is reported at 203 F. Supp.

225.

since a large majority of the Negro residents live in the

Jefferson District the result was that, with the exception

of some 13 Negro pupils attending the predominantly white

Venable School, all of the Negro elementary pupils were

enrolled in the Jefferson School, which no white pupils at

tended. No Negro pupils were assigned to the four other

elementary schools. The plan, however, provided that the

parents of any child, white or colored, could request a

transfer and the superintendent of the schools was em

powered to grant such a request after consideration of

various criteria applicable to white and Negro pupils

alike, including factors affecting the immediate interests

of the pupils and the efficient administration of the schools.

Two high schools were operated in the City, Lane and

Burley. There were no zones for admission to these schools

but the superintendent was guided in making assignments

of students by the pupil-teacher ratio, convenience of at

tendance, academic qualifications and, to some degree, by

the preference of the pupil and his parents. The transfer

provisions were the same as those applicable to the ele

mentary schools.

Prior to the plan for desegregation Lane was all-white

and Burley all-colored. In 1960-61, at the time the Dodson

case was brought, thirteen Negro elementary pupils had

been assigned to Venable and seven Negro high school

students had been assigned to Lane. That suit was in

stituted on behalf of four Negro pupils whose application

for admission to white elementary schools had been denied

because they resided in the Jefferson district and also on

behalf of six Negro high school pupils whose application

for admission to Lane had been denied, four because of

academic deficiency and two because they resided nearer

to Burley than to Lane. Having been denied relief in the

District Court the plaintiffs appealed to this Court. We

upheld the Board’s plan but condemned the Board’s ap

6

plication of the plan as discriminatory and unconstitutional.

We pointed out that all Negro elementary pupils were ini

tially assigned to Jefferson whatever the zone of their

residence but white pupils living in Jefferson were initially

assigned to white schools in other districts. In respect

to high schools we showed that all colored pupils were

initially assigned to Burley and all white pupils to Lane

and that Negro pupils desiring to transfer to Lane were

subjected to residence and academic tests which were not

applied to white students seeking admission to Lane. We

recognized that these practices were discriminatory but,

upon the assurance of the Board that they were transitory,

we remanded the case to the District Court to reexamine

the situation with regard to the ensuing school year, 1961-

1962, “confident that steps [would] be taken promptly to

end the present discriminatory practices in the administra

tion of the desegregation plan”, 289 F. 2d 444.

Mindful of this admonition the School Board made cer

tain changes in its plan of operation. The assignment of

each elementary school pupil, white or colored, was made

to the school in his residence zone. This step, of course,

tended to perpetuate the earlier practice of segregation;

but transfers were permitted in the following fashion.

Elementary pupils, white or colored, assigned to schools

where they were in the racial minority were permitted

with the consent of their parents to transfer to a school

in another district where they would be in the racial

majority. Thus a white child living in the Jefferson

colored district could transfer to a school in one of the

five white districts and a colored child living in one of

the white districts could transfer to Jefferson. To ef

fectuate this plan a form letter was sent by the Super

intendent of the schools to the parents of each child

attending an elementary school outside the zone of his

residence stating that the child had been tentatively reas

7

signed to the same school, but that the child could remain

in that school only if the parents specifically requested it.

A form to be signed by parents was attached to the letter.

Through this procedure all of the white pupils, 149 in

number, who lived in the Jefferson area were granted

“transfers” to schools in the other zones and approximately

50 Negro elementary school pupils residing in the white

districts were “transferred” to Jefferson. Nine addtiional

Negro pupils were admitted to the Venable elementary

school, bringing the total number in attendance to twenty

and nine additional Negro high school pupils were admitted

to Lane, bringing the total to sixteen.

The School Board reached the conclusion that by adopt

ing this plan they had eliminated all racial discrimination

and, accordingly, they rejected the applications for trans

fer to other districts of seventeen Negro elementary pupils

residing in the Jefferson district. On their behalf the

present suit was brought in the District Court to restrain

the actions of the Board but the District Judge held that

the plan was valid and this appeal followed.

The question for decision is of especial importance in

the administration of the Charlottesville schools in view of

the Board’s past operations and its present attitude in the

administration of the school system. When it is noted that

despite prolonged litigation all of the Negro elementary

school pupils in the City, other than the twenty assigned

to Venable, are still enrolled at the all-Negro Jefferson

school, while all of the white students attend one of the

five elementary schools in the other districts, and that all

of the Negro high school students except sixteen attend

the all-Negro Burley High School, it is clear that little

change has been made in the administration of the ele

mentary schools from that which prevailed when the schools

were completely segregated. It seems equally clear that

8

little progress in the integration of the schools may be

expected if the Board is permitted to pursue the policy

which, after mature consideration, it has deliberately

adopted.

The Board’s argument is that there is no racial dis

crimination in the enrollment of the pupils in the elementary

schools for the following reasons. The Board has aban

doned the plan contained in our decision in the Dodson

case. Under that plan Negro pupils wherever they lived

were initially assigned to Jefferson and white students

were initially assigned to the school of the zone of their

residence; and since transfers were only sparingly per

mitted the admission of colored pupils into white schools

was effectually prohibited and segregation was prolonged.

Under the new 1961-1962 plan, says the Board, every child

whether white or Negro is initially assigned to the school

of his residence district and transfers are granted to white

and colored children under the same rule or restriction.

Any child may transfer from a school in which his race

is in the minority to a school in which his race is in the

majority and since this plan applies to both races alike

there is no discrimination.

In support of its position the Board relies on Kelley v.

Board of Education of the City of Nashville, 6 Cir., 270

F. 2d 209,* where it was held that a transfer provision is

not invalid which permits voluntary transfers of white and

Negro students who would otherwise be required to attend

schools previously serving only members of the other race,

or where the majority of the students are of the other

race. The Court thought that this plan was not invalid

since the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education,

* Certiorari was denied in this case, 361 U. S. 925, three justices

indicating that they would grant the petition limited to the ques

tion whether certain provisions of the Nashville plan were in

valid for the reason that they “explicitly recognized race as an

absolute ground for the transfer of students between schools,

thereby perpetuating rather than limiting racial discrimination.”

9

347 U. S. 483, did not deprive persons of the right of

choosing the school they desired to attend but merely held

that a person may not be denied the right to the school

of his choice because of his race. The Sixth Circuit, how

ever, in its subsequent decision in Goss v. Board of Educa

tion of the City of Knoxville, Term., 301 F. 2d 164 (1962),

observed that the application of this transfer provision

may become a violation of constitutional rights and con

sequently admonished the Board not to use it as a means

of perpetuating segregation. And see Maxwell v. County

Board of Education of Davidson Co., Term., 301 F. 2d 828,

6 Cir., 1962. Moreover, the Fifth Circuit in Boson v. Rippy,

285 F. 2d 43, differing from the views set out in the Kelley

case, disapproved a desegregation plan which included a

transfer provision like that practiced in Charlottesville.

It held, 285 F. 2d 48, that “classification according to race

for purposes of transfer is hardly less unconstitutional

than such classification for purposes of original assign

ment to a public school.” In Mapp v. School Board of

Chattanooga, D. C. E. D. Tenn. 1962, 203 F. Supp. 843,

853, the District Court, in accord with Boson v. Rippy,

supra, said that “any transfer plan, the express or primary

purpose of which is to prevent or delay the adoption or

implementation of the plan of desegregation herein de

veloped, should not be approved.”

In our view the Charlottesville plan in respect to the

pupils in the elementary schools is clearly invalid despite

the defense that the rules for the assignment and transfer

of pupils are literally applied to both races alike. It is of

no significance that all children, regardless of race, are

first assigned to the schools in their residential zone and

all are permitted to transfer if the assignment requires the

child to attend the school where his race is in the minority,

if the purpose and effect of the arrangement is to retard

integration and retain the segregation of the races. That

10

this purpose and this effect are inherent in the plan can

hardly be denied. The School Board is well aware that

most of the Negro pupils in Charlottesville reside in the

Jefferson zone and that under the operation of the plan

white children resident therein will be transferred as a

matter of course to the schools in the other zones while

the colored children in the Jefferson zone will be denied

this privilege. The seeming equality of the language is

delusive, the actual effect of the rule is unequal and dis

criminatory. It may well be as the evidence in this case

indicates that some Negroes as well as whites prefer the

schools in which their race predominates; but the wishes

of both races can be given effect so far as is practicable

not by restricting the right of transfer but by a system

which eliminates restrictions on the right, such as has

been conspicuously successful in Baltimore and in Louis

ville.

It was suggested during the argument of the appeal that

a reversal of the judgment of the District Court might

lead the Board to deny all transfers in the Charlottesville

schools. We take this occasion to say, however, that such

a step might well be as obnoxious as that employed by the

Board in the case at bar. A similar plan was condemned in

Taylor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 2 Cir., 294

F. 2d 36.

We do not mean to say that the School Board has no

discretion in the assignment of pupils to the Charlottes

ville schools, but in respect to the elementary children in

this case the Board has applied no criteria that would

stand the constitutional test and, therefore, in the interest

of these children further delay in the exercise of their

constitutional rights cannot reasonably be granted.*

* The operation of the Charlottesville schools was brought to our

attention in 1956 in School Board of the City of Charlottesville v.

Allen, 240 F. 2d 59.

11

We, therefore, hold that as to the seventeen elementary

children, who were plaintiffs in the court below, the judg

ment be reversed and the case remanded to the District

Court so that appropriate steps, by injunction or otherwise,

may be taken to secure their admission to the schools of

their choice for the 1962-1963 school year.

The cross-appeal by the School Board in this case re

lates to the judgment of the District Court that nine Negro

high school pupils who were excluded by the Board from

the Lane High School be admitted to that institution.

Subsequently, the Board admitted two of the nine and as

to them the cross-appeal is expressly abandoned in the

Board’s brief in this Court. Four of the remaining seven

were before this Court in the Doclson case, where we noted

that they had been excluded from Lane for academic defi

ciency and said that residence and academic tests may be

properly applied in passing on the applications for ad

mission to a school provided that the factors of race and

color are not considered, 239 F. 2d 439, 442. Since it was

shown that the tests were not applied to white children

in the same situation we held that the four plaintiffs had

been discriminated against. Nevertheless, we affirmed the

judgment below in the confident belief that discrimination

between the races in the admission of high school students

would be eliminated by the Board itself. In this respect our

hopes have been disappointed. The Board has abandoned

the residence tests as to high school children but has made

no change in the academic tests. The four Negro high

school pupils who were before us in the Dodson case, and

in addition three other high school students, all of whom

are cross-appellees in this case, have been denied admission

to Lane because of alleged academic deficiency. The Board’s

position is that their admission into a school for which

they are not qualified will not only be detrimental to them

but to the school itself and, therefore, they should be

12

excluded. Obviously, these factors are worthy of considera

tion in the operation of any school system. The difficulty

is, however, that the Board admits white children to Lane

without tests, irrespective of their academic qualification,

upon the theory that they should not be denied any high

school education whatsoever. The alternative of sending

them to Burley is not deemed worthy of consideration.

The discrimination involved is too clear to require dis

cussion. Not only are academic tests applied to Negroes

only but Negroes who are considered so deficient in aca

demic achievement that their admission to Lane would be

detrimental to the school, are sent to Burley without regard

to the consequences. See Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, E. D. La., New Orleans Div., ----- F. Supp. ----- ,

decided April 3, 1962.

Accordingly, the judgment of the District Court regard

ing the admission of the nine high school students to the

Lane High School will be affirmed and the case will be re

manded to that Court in order that appropriate steps may

be taken to put the judgment into effect.

Reversed in part and affirmed in part and remanded for

further proceedings. Let the mandate issue immediately.

----------* ----------

A lbert V. B ryan , Circuit Judge, w ith w h o m H a y n sw o r th ,

Circuit Judge, jo in s , d is s e n t in g :

Without semblance or hint of gerrymandering—so con

ceded by the appellants—school districts were laid out

by the Charlottesville School Board for elementary classes

in a plan of desegregation which had been filed at the

instance of the District Court: each child regardless of

race is assigned to the school in the district of his residence.

Then, any pupil is allowed—by merely a telephone call—

to transfer from any school in which his race is not in the

majority. Yet this arrangement is now stricken down by

13

the Court because in the operation of the transfer feature

as to one school—Jefferson—there can be no transfer of

a Negro student from that school inasmuch as it is pre

dominantly Negro. This is said to be discrimination. I

think the conclusion erroneous both in fact and in law.

I. It is not discrimination in fact because the same right

of transfer as the white children have at Jefferson is ac

corded colored children in schools that are mostly “white”.

The same restriction of the Negroes at Jefferson is applied

to the white children in the other schools. The Negroes

may transfer from the latter—and 50 of them did—whereas

no white student can leave those schools. It is argued that

the white children would not desire to leave a “white”

school but the Negro would want to leave Jefferson, and

thus he is deprived, because of his color, of the “right” to

attend an integrated school. This is to argue, also, that

by leaving Jefferson School the white children create segre

gation there. With equal reason it may be argued that

the colored children in departing from the other schools

caused segregation there. All of these contentions wrongly

ignore three vital considerations: the fairness of the en

tirety of the plan; the Fourteenth Amendment does not

guarantee a student an integrated school to attend; and

the “segregation” here is not the result of the plan but of

individual choices of individual students.

The Negro was not placed at Jefferson because he was

a Negro, nor was the white child enrolled at another

school because he was white. Neither was so placed in

order to keep them apart. They are in their respective

schools solely because of the location of their respective

residences and for no other reason. The Jefferson residence

district, to repeat, was not arbitrarily formed.

Approval of the plan of the Charlottesville Board has

been declared by this Court. In Dodson v. School Board,

289 F. 2d 439 (4 Cir. 1961) we said of it, at p. 442:

14

“At the elementary school level, the plan contem

plates that every child, regardless of race, shall be

sent initially to the school of the district in which he

lives, and after such initial assignments, there may be

transfers if the parents so request and the superin

tendent approves. This is a perfectly acceptable method

of making school assignments, as long as the granting

of transfers is not done on a racially discriminatory

basis or to continue indefinitely an unlawful segregated

school system . . . ”

The only criticism of the plan there made was the initial

assignment of all Negro elementary pupils in the city to

Jefferson, rather than to the school of their residence.

This was corrected. So that now the only objection urged

is that the Negro student does not have freedom to move

out of Jefferson when that is the school of his residence.

The Sixth Circuit approved an equivalent of the Char

lottesville transfer provision in Kelley v. Board of Educa

tion, 270 F. 2d 209, 228 (6 Cir. 1950) cert, denied 361

U. S. 924, and more recently in Goss v. Board of Education,

301 F. 2d 164, 168 (6 Cir. 1962) and Maxwell v. County

Board of Education, 301 F. 2d 828, 829 (6 Cir. 1962).

Contra: Boson v. Rippey, 285 F. 2d 43, 47 (5 Cir. 1960);

but see Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690, 693 (5 Cir. 1957)

post p. 4. Taylor v. Board of Education, 294 F. 2d 36

(2 Cir. 1961) cert, denied 368 U. S. 940, decided by a divided

court is not authority to sustain the Court here. There a

suburban New York City school district had been de

liberately drawn so as to encompass Negro residents only.

II. In law there has been no discrimination, for the

Negro child has not been denied any privilege through

policy, usage, law or regulation. If there has been a dep

rivation, it is—solely, actually and not capriciously—the

result of the geographical location of his residence. This

15

is a consideration understandably overlooked by. the Court

in the generality of its statement that the infrequency of

Negro attendance in “white” schools is itself proof of dis

crimination.

Jefferson School District, as previously noted, was not

a discriminatory division. It came about, as often occurs

in many cities, through the Negroes’ living in a concen

trated area. This may:, change, and thereafter alter the

play of the residence and transfer rule at Jefferson. But

until then the residents of the area must abide by rules

and regulations based on just and fair district lines. No

constitutional or legal question is presented. No Govern

ment authority has allocated them to a special section of

the city or centered their population in a specific territory.

The fundamental reason of the Court for holding the

refusal of transfer of Negroes to the Jefferson District to

be discrimination seems to be that the refusal deprives the

Negro children of association with white children, all of

whom have transferred from Jefferson District. There is

no other grievance suggested in their remaining at Jeffer

son. The Court further manifests this reason when it says

that the residence and transfer provision retards “inte

gration”.

But even if this is the result of the Charlottesville plan:—

although entirely incidental—nevertheless it would not be

a violation of the doctrine of Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483 (1954) and subsequent commentary deci

sions. The Supreme Court was explicit there in not re

quiring integration, but in merely striking down denial of

rights through segregation. The point was sharply made

in Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955).

It is too late now to question this as the plain holding

of that three-judge court. Judge Parker, a member of

that panel, confirmed this meaning when he spoke for

this. Court in School Board of Charlottesville v. Allen,

16

240 F. 2d 59, 62 (4 Cir. 1956) cert, denied 353 IT. S. 911,

and again in School Board of City of Newport News v.

Atkins, 246 F. 2d 325, 327 (1957). Substantially this very

statement was approved with emphasis by the Fifth Cir

cuit in Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690, 693 (1957). Fur

thermore, on remand of Brown v. Board of Education,

the District Court from which it originated, following the

rescript of the Supreme Court immediately after its second

and implementing school decision, Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 349 IT. S. 294 (1955), stated the proposition with

equal clarity as follows:

“Desegregation does not mean that there must be in

termingling of the races in all school districts. It means

only that they may not be prevented from intermingling

or going to school together because of race or color.

“If it is a fact, as we understand it, with respect to

Buchanan School that the district is inhabited by

colored students, no violation of any constitutional

right results because they are compelled to attend the

school in the district in which they live.”

Brown v. Board of Education, 139 F. Supp. 468, 470 (D.

Kan. 1955). Like decisions in other Circuits are cited in the

dissent in the Second Circuit (N. Y.) case of Taylor v.

Board of Education, supra, 294 F. 2d at 47, n. 4.

Our Court’s opinion now seems to hold that if a racial

minority in a school zone is given a right to transfer out,

every member of the racial majority in that school must be

given the same right—otherwise the rule is unconstitutional.

Applied to Jefferson School the opinion intimates that the

Negro pupils there—the great majority of the student body

—should be permitted to transfer in the same way as the

minority. But the Court denied this very right to the ma

jority in McCoy v. Greensboro Board of Education, 283

17

F. 2d 667 (4 Cir. 1960). There the Board granted the re

quests of Negro children to enter a “white” school, then

afterwards allowed the transfer of the majority—all white

children—to another school. The transfer of the majority

was held invalid because it left a minority composed of

Negroes only. This again was apparently on the thesis

that it resulted in a separation of the races whereas the law

requires integration—a theory I find untenable.

III. The transfer rule is simply a means of permitting

a child to express his wishes. Surely, to allow a child such

an option—even though his wishes be based on racial

grounds—is not unconstitutional. Allowing expression by

both races so far as practicable—with equal opportunity—

of their preferences in a personal matter has not in any de

gree been precluded by the Supreme Court in its efforts

to solve the school problem or in any other field. The Court

has merely ruled against enforced separation of persons

of different races by reference to objective criteria. Never

has the Court denied the exercise of the personal tastes

of the races in their associations.

The judgment of the District Court in respect to the

elementary school appellants should be affirmed. In regard

to the high school appellants I express no disagreement

with the majority.

H a y n sw o r th , Circuit Judge, w ith w h o m B ryan , Circuit

Judge, jo in s , d is s e n t in g :

I agree with m y brother, Bryan, and I join him in his

opinion.

I am prompted to turn to other considerations, however,

for it seems to me the two opinions are on an esoteric

plane far above practical problems confronting school

boards. Practical, difficult problems do arise in many places

18

as school boards undertake the task of conversion of school

systems to a basis of operation which counters social cus

toms and patterns of conduct, which, over a period of cen

turies, have become deeply ingrained in a people. The

Supreme Court in 1955 recognized that such problems would

be encountered and directed that they be not ignored!

School boards were allotted the duty of solving and over

coming those problems with all deliberate speed, while the

lower federal courts were required to enter appropriate

orders when school boards neglect their duty. It is not for

the courts, however, by overlooking the practical problems,

to impose difficulties in the way of a school board strug

gling, even though with some reluctance, to achieve the

goal that has been set for it.

As I approach the practical situation, in terms of which

I think the legal issue here should be framed, I do so with

awareness that the case has not been presented on that

basis. The question whether discrimination inheres in a

geographic assignment plan, if accompanied by a provision

for permissive minority transfers, has been tendered in

general and abstract terms.1 2 The Court answers it in

those terms.3 The School Board has sought affirmance of

1 Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. Ed. 1083.

2 The question tendered, in effect, is th is: If A and B, one of

whom is Caucasian and the other Negro, each of whom is a member

of a racial minority in the school to which he is assigned, are both

allowed to transfer, is there a denial of the equal protection of the

laws to X, if X and T, a Negro and a Caucasian, each of whom is a

member of a racial majority in the school to which he is assigned,

are both denied transfers? Since the conundrum elides the fact,

or the possibility that it may be the fact, that there was good reason

for allowing the transfers of A and B and no comparable reason

for allowing the transfer of either X or Y, the resultant discussion,

interesting though it may be, is esoteric abstraction.

3 The majority concentrates attention upon A and X, both of

whom had been assigned to the same school. That concentration

does not make the resulting discussion concrete, for the opinion

19

the District Court’s approval of its plan on the basis of

its belief that the plan, generally and abstractly, is not dis

criminatory. It has not asked that it he approved as a

reasonable amelioration of a particular problem during

a transitional period. That it asked for more, however,

does not mean it should get less than its due. If its plan

merits temporary approval as a transitional measure, its

disapproval should not be unqualified.

One may thus concede the reasonableness of the abstract

principle declared by the majority and reasonably hold the

view that the majority should have proceeded further to

consider whether the plan, with its determined defects and

shortcomings, might not be permissible as a temporary

expedient. If the present record is insufficient for that pur

pose, it could be supplemented upon remand. At least, the

implication that the abstract principle will be applied in

other cases, no matter how compelling the reasons for the

school board’s adoption of a similar plan, ought not to be

left open.

Those conversant with the problems of desegregation in

the South, know the intensity of public concern over the

plight of children constituting a small minority unwillingly

assigned to a school in which an overwhelming majority is

of the other race. If separation of Negro children “solely

does not consider their disparate circumstances or the bearing of

those circumstances upon the reasonableness of a general rule al

lowing the permissive transfer of the one, but not of the other.

The majority also points to the fact that the Board’s plan per

mits actual mixing of the races in the schools at a slower rate than

might occur under some other plan, not adopted by the School

Board. Such a fact may bear more or less heavily upon the rea

sonableness of a particular plan under particular circumstances,

but, of itself and without regard to other facts bearing upon the

reasonableness of the Board’s conduct, it is not a final answer. The

same thing may be said of every interim arrangement which has met

the approval of the courts. Indeed, the same thing may be said of

a geographic assignment plan unaccompanied by any provision for

permissive minority transfers.

20

because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as

to their status in the community that may affect their

hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone,” 4

such a child may be subjected to a much more searing ex

perience if, bereft of established friends and relations, com

pelled to attend a school or classes in which all others are

of the opposite race. Some children could adjust themselves

to such a situation, but in the early stages of desegregation

when the force of old customs and practices is unspent,

many could not. Those who could not adjust to such a

radical change would likely have senses of inferiority

greatly intensified, and unadjusted children too frequently

become the butt at the hands of their fellows of those un

restrained cruelities of which children of all races are cap

able. If such unadjustable children are compelled to remain

in an intolerable situation, the damage to their emotional

and mental development and well-being will be irreparable.

It is because of such widespread concern over the plight

of unwilling minorities in particular schools that school

boards throughout the South have adopted permissive

transfer provisions in association with assignment plans

based upon attendance areas or other objective criteria.

In some places, such a provision may be essential to the

institution or continuance of a plan of desegregation, for

it touches an area of peculiar public sensitivity, and school

boards cannot operate public school systems without pub

lic support.

Provisions for permissive minority transfers are founded

upon an assumption that the transition to a fully desegre

gated school system will create personal problems for un

willing minorities in particular schools, especially when

the minority is relatively small, which differ in kind and

degree from the problems which majorities, especially rela

4 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 495, 74 S. Ct. 686,

98 L. Ed. 873.

21

tively large majorities, may be expected to encounter. The

assumption seems plainly valid, for it hardly is to be

doubted that a child well adjusted in school A where his

race predominates, where he has established friendships

and where he ardently wishes to be, may become very mal

adjusted if compelled to attend school B where his own race

is a small minority, where he has no established friends

and where racial differences may become greatly magnified

in his own mind. Such a problem is obviously more acute

and more difficult to overcome than any personal problem

which may be anticipated by members of racial majorities,

unseparated from established friends, compelled to accom

modate themselves to the presence or absence of a minority

of pupils of the other race.

Of course, the magnitude of the personal problems and

of the difficulties in the way of requisite adjustments will

vary with individuals and with differences in environ

mental conditions. A child who might encounter insur

mountable difficulty, as a member of a small minority, in

making the personal adjustment, might encounter little dif

ficulty if the minority group was relatively large, 49%, for

instance,5 and included others who were his old friends.

Such variances, however, do not militate against the gen

eral validity of the assumption that, in the transitional pe

riod, unwilling members of minority groups will encounter

difficulties and problems which are different in kind and

degree from those which members of majority groups may

be expected to encounter.

This kind of problem exists whatever the race of the

minority group. That present provision for permissive

minority transfers is in the interest of Negro minorities

is suggested by the extent to which they avail themselves

of it. This very record discloses that fifty Negro pupils

availed themselves of the permissive right to transfer to

5 Of course, that is not this case.

22

Jefferson School, rather than attend the predominantly

white schools in the attendance areas of which they resided.

The majority, of course, does not hold that unwilling

minorities may not be allowed to transfer. It does hold

that if such transfers are allowed as of course, the same

right of transfer must be extended to every other child

regardless of the dissimilarities of his circumstances. The

provision for minority transfers is treated as a virus which

so infects an otherwise objective, nondiscriminatory, lawful,

geographic assignment plan, that the plan may not be

enforced as to anyone. Provision for protection of the

special interest of minorities is related to malice, which,

naked and alone, is not unlawful, but which makes unlawful

and actionable a communication which otherwise would be

privileged and unactionable.

The necessary result of the opinion, therefore, is a stric

ture on provision for permissive transfers of protesting

members of minority groups whenever a school board finds

it necessary or desirable to adopt or continue an enforceable

geographic assignment plan. The consequence will be that

the discretion of school boards is circumscribed, and, in

some instances, the effective adoption of any plan may be

made impossible.

I do not understand the court to say that, in the absence

of a blanket provision for the transfer of unwilling mem

bers of minority groups, a transfer of one such child, for

good reason, would deprive the school board of its power

of enforcement of all other assignments. It certainly should

not. School boards always have had, and always should

have, discretionary power to treat exceptional cases as

exceptional. If a school board, having adopted a geographic

assignment plan without a minority transfer provision, was

confronted with proof that a particular child had previously

attended a segregated school attended solely by members

of his own race where he worked well and was well adjusted,

23

but, assigned under the plan as one member of a small

minority to another school predominantly populated by

pupils of the other race, had encountered insurmountable

difficulty, that his progress had been arrested and he was

suffering great emotional and mental harm, and if such

proof was accompanied by the urgent plea of the child

and his parents that he be transferred back to the school

he formerly attended, must the school board ignore the

plea or suffer loss of its power to control all other assign

ments which it had made under its geographic assignment

plan? I would say, obviously not.6 Every exception to a

general rule, if made with good reason, does not invalidate

the rule. A permissive transfer of a child whose personal

need makes a transfer requisite, should not confer upon all

other pupils, who have no comparable need, the same trans

fer privilege. If tutorial assistance is furnished the child

who needs it most, every other pupil, who has no such need,

is not denied the equal protection of the laws if he is not

offered the same assistance. It would be a gross perversion

of constitutional doctrine to say that any governmental

body may not reasonably classify citizens and their claims

or that a classification based upon the need of the claimants

is necessarily unreasonable.

If this be so, if a transfer of one child in dire need of

it as an exception to an otherwise lawful, geographic as

signment plan does not divest the school board of its au

thority to deny transfers to those who show no such need,7

a general provision for permissive transfers of the needy

6 If a member of a racial majority has comparable need of a

transfer, I think a school board could and should transfer him and

that its doing so would not deprive it of the power to deny transfers

to other members of the majority, assigned by attendance areas,

who have no comparable need.

7 If this be not so, the conclusion cannot be premised upon any

thing to be found in the Constitution of the United States.

24

class must be permissible if the actual and special need

of those to whom it applies reasonably warrants it. The

existence of such need and its relationship to the rule,

the majority does not consider. The court does not reach

the question whether the provision, as an interim measure

and as applied here, is reasonable, wise or even essential

to progress. It concludes that the provision, however rea

sonable, in combination with the assignment plan is ab

stractly discriminatory, and there it stops.

If that were the stopping place, no “stair-step” plan of

desegregation would ever have been approved. Such plans

are not just abstractly discriminatory, inevitably in ap

plication they are concretely so. They are approved, none

theless, when they represent reasonable progress toward

ultimate compliance. Other such interim measures, though

claiming no pristine purity free of discrimination’s taint,

are similarly approved. Indeed that is the very thing the

Supreme Court required of us by its remand order in the

School Cases. During this transitional period, we have no

right to strike down what Charlottesville’s School Board

has done or to overturn its authority over assignments and

transfers, unless, after full consideration, it is found that

what it has done is unreasonable in the light of all of the

circumstances.8 -

8 Of course, this determination is initially for the District Judge,

whose findings we can overturn only within the traditional rules

limiting our appellate power. Here there is no clear finding on the

decisive fact of reasonableness or unreasonableness, for the District

Court was of the opinion that the plan was not discriminatory, even

abstractly. A remand for further consideration of the crucial ques

tion of reasonableness of the rule in the light of the needs and the

differences in the needs of members of disproportionate minority

and majority groups, might be appropriate. We should not under

take a final decision of that factual question; at least, we should not

decide it without consideration of it.

25

Since it seems to me the court has not reached the crucial

question and that its abstraction is not decisive of the whole

case, I have found it necessary separately to record my

disagreement with the result.

Judge Bryan authorizes me to note that he joins in this

dissent.