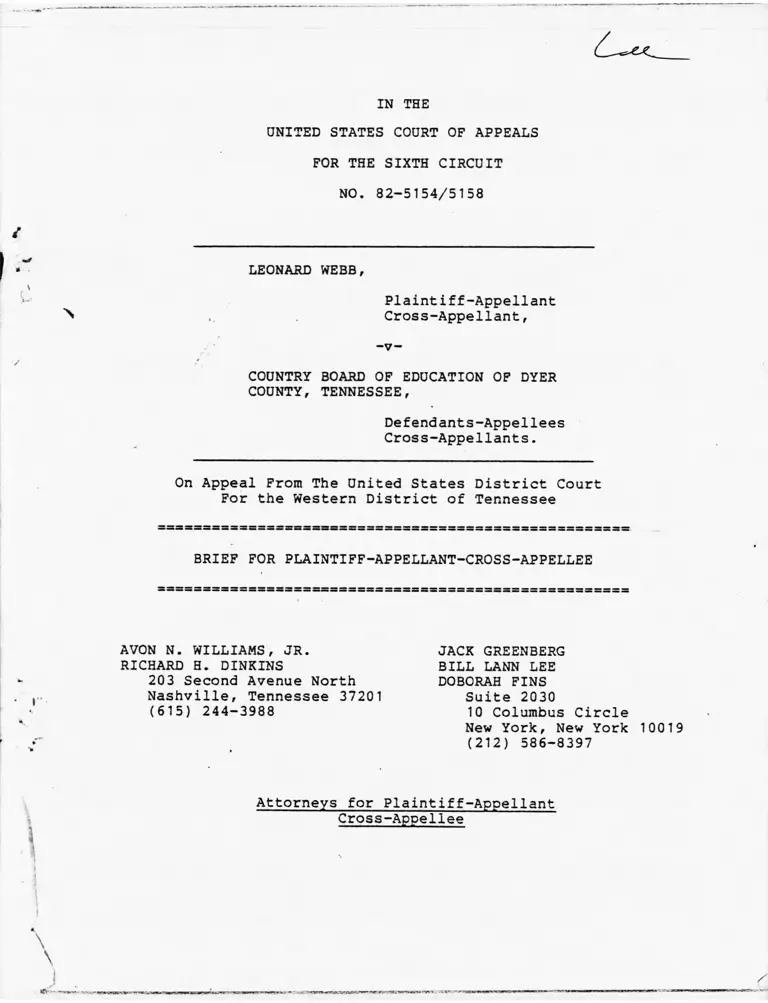

Webb v. County Board of Education of Dyer County, Tennessee Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant-Cross-Appellee

Public Court Documents

June 9, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Webb v. County Board of Education of Dyer County, Tennessee Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant-Cross-Appellee, 1982. 979affcd-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/260386ab-1700-445b-a0ee-35f49064865b/webb-v-county-board-of-education-of-dyer-county-tennessee-brief-for-plaintiff-appellant-cross-appellee. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 82-5154/5158

LEONARD WEBB,

Plaintiff-Appellant

Cross-Appellant,

-v-

COUNTRY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF DYER

COUNTY, TENNESSEE,

Defendants-Appellees

Cross-Appellants.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Western District of Tennessee

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT-CROSS-APPELLEE

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

RICHARD H. DINKINS

203 Second Avenue North

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

(615) 244-3988

JACK GREENBERG

BILL LANN LEE

DOBORAH FINS

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

Cross-Appellee

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Pa^e

Question Presented ...................................... 1

Statement ...»............................................ 2

Administrative Proceedings ........................ 2

Judicial Proceedings .............................. 5

Argument .................................................

I. The Statutory Language of § 1988 Permits

Recovery of Attorney's Fees for Legal

Representation in Administrative

Proceedings .................................. 12

II. Legislative History Supports Recovery

of Attorney's Fees for Legal Representa

tion in Administrative Proceedings ......... 18

III. Permitting Recovery of Attorney's Fees for

Legal Representation in Administrative

Proceedings Fulfills the Purposes of

the Statute ................................. 24

Conclusion ............................................. 22

i

Certificate of Service ................. 33

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Bartholomew v. Watson, 665 F.2d 910 (9th Cir.

1982) ......................... ............. 12,13,22,23,29

Blow v. Lascaris, 50 U.S.L.W. 2178 (N.D. N.Y.

1981), affirmed, 668 F.2d 670 (3d Cir. 1982) 31

Booker v. Brown, 619 F.2d 57 (10th Cir. 1980) 23

Brown v. Bathke, 588 F.2d 634 (8th Cir. 1978) 22

Brown v. Culpepper, 561 F.2d 1177 (5th Cir.

1977) ....................................... 32

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677

(1979) ............... ....................... 14

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976) 27

Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal, Inc., 670 F.2d 760

(7th Cir. 1982) ............................ 17,20,24,30,31

Davis v. Barr, 373 F. Supp. 740 (E.D. Tenn.

1973) .............. ........................ 3

Fisher v. Adams, 572 F.2d 406 (1st Cir. 1978) 23

Foster v. Boorstin, 561 F.2d 340 (D.C. Cir.

1977) ....................................... 21,23,28

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District,

608 F .2d 594 (5th Cir. 1979) .............. 27

Hatton v. County Board of Education of Maury

County, Tennessee, 472 F.2d 457 (6th Cir.

1970) ....................................... 3

Johnson v. United States, 554 F.2d 632 (4th

Cir. 1977) ................................. 23

Kulkarni v. Alexander, 662 F.2d 758 (D.C. Cir.

1978) ....................................... 18,20,24

Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122 (1980) ......... 15,16,19,29,31

- ii -

Pa^e

Maine v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 (1980) ...... 15

Martinez v. California, 444 U.S. 277 (1979) 16

Monroe v. Bd. of Com'rs of City of Jackson,

581 F .2d 581 (6th Cir. 1978) .............. 32

NAACP v. Medical Center, Inc. 599

F. 2d 1247 (3d Cir. 1979) ........ ......... 14

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey, 447

U.S. 54 (1980) ............................. Passim

Northcross v. Board of Education, 611 F.2d

624 (6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 447

U.S. 911 (1980) .......................... 12,18,20,22,25

Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir.

1977) ................. ..................... 19

Parker v. Matthews, 411 F. Supp. 1059

(D.D.C. 1976) .............................. 19,21,23,28

Richards v. Reed, 611 F.2d 545 (5th Cir. 1980) 23

Seals v. Quarterly County Court, 562 F.2d 390,

394 (6th Cir. 1977) . ........................ 18

Smith v. Califano, 446 F. Supp- 530 (D.D.C.

1978) ....................................... 23

Sullivan v. Brown, 544 F.2d 279 (6th Cir.

1976) ..................................... 26

Sullivan v. Com. Pa. Dept, of Labor, 663

F .2d 443 (3d Cir. 1981) ..................... 17,20,22,24,31

Swain v. Secretary of Navy, 50 U.S.L.W. 2439

(1982) ...................................... 32

Thomas v. Honeybrook Mines, Inc., 428 F .2d

981 (3rd Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S.

911 (197 ) ................................. 20,22

i n

Constitutional & Statutory

Provisions

Page

3,5

5 U.S.C. § 504(Equal Access to Justice Act 21

42 U.S. C. § 1981 ........ .................... 5,10,11,14

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ............................. 5,10,14,15,16

42 U.S.C. § 1985 ............................. 5,10

42 U.S.C. § 1986 ............................. 5,10

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ............................. Passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000d ............ ........ ....... 5,10,13

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-3(b) ....................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k), § 706(k) of Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ....... 12,13,16,17,18,30,31

10

10,21

2,3

Other Authorities

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 13,19,26

H.R. Rep. No. 96-1418, 96th Cong., 2d Sess.

11 (1980) ................................... 21

H. Conf. Rep. No. 96-1434, 96th Cong., 2d 21

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 20,22,25

E. Larson, Federal Court Awards of Attorney’s 30

- iv -

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 82-5154/5158

LEONARD WEBB,

Plaintiff-Appellant-Cross-Appellee,

v .

COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF DYER COUNTY,

TENNESSEE,

Defendants-Appellees-Cross-Appellants.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District Of Tennessee

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

CROSS-APPELLEE

Question Presented

Whether the district court erred in declining to award

attorney's fees in a civil rights action for prevailing

plaintiff's legal representation in administrative proceed

ings solely on the ground that exhaustion of administrative

proceedings was not required by the relevant civil rights

acts, although 42 U.S.C. § 1988 provides for an award of

fees and costs "[i]n any action or proceeding to enforce" a

provision of the civil rights acts.

Statement

The merits of this civil rights action challenging

the dismissal of a black teacher were settled prior to

trial by a consent order of dismissal awarding damages

and equitable relief to the teacher. This appeal is taken

from findings of fact and conclusions of law and order

allowing attorney's fees and costs which permitted plain

tiff an award for the court action, but denied plaintiff

any fees or costs for administrative proceedings.

Administrative Proceedings

On March 25, 1974., plaintiff Leonard Webb, a tenured

black teacher, was notified of his suspension by the Super

intendent and County Board of Education of Dyer County,

Tennessee (hereinafter "board") pending investigation and

disposition by the board of "charges relating to your past

record as a teacher." Two weeks later, Webb was notified

of his dismissal by the board for "unprofessional conduct

and subordination" pursuant to Tenn. Code Ann. 49-1412.

(R. 2, Complaint at p. 11, R. 3, Exhibits A and B to Amend

ment to Complaint, R. 87, Affidavit of Dwight L. Hedge

appended to Response and Memorandum in Opposition, A. ig> 31 t

32, 76.) Webb was advised that the dismissal was based

on the board's "review[ of] the written criticism of

parents and school administrators regarding your teaching

experience at Newbern Elementary School." Id. However, Webb

- 2 -

;>iae5s*.>r v .z - - '.4 -:v-

was not given the prior written notice and copy of charges

warranting dismissal nor afforded the opportunity for a

hearing before the board prior to dismissal required by

1/

state law. Term. Code Ann. 4.9-14-15, 14-16.

Webb retained Avon N. Williams, Jr., Esq. of Nashville,

Tennessee, as counsel, and requested a hearing before the

board. (R. 87, Affidavit of Dwight L. Hedge, A. 77.) The

board also was represented by counsel. Testimony was heard

by the board in June 1974-, later in 1974-, November 1977 and

April 1978. Id. At the hearing, Webb alleged that his dis

missal violated state law, and the Fourteenth Amendment and

1/federal civil rights laws. (R. 73, Tr. at 9, 96.) With

1/ See, Hatton v. County Board of Education of Maury

County, Tennessee, 472 F .2d 457, 459 (6th Cir. 1970); Davis

v. Barr, 373 F. Supp. 740, 744-46 (E.D. Term. 1973).

2/ The transcript of the hearing before the board (R. 73,

Transcript attached to Affidavit of Avon N. Williams) reveals

the following:

The Dyer County public schools remained racially segre

gated until the late '60s. (_Id. at 11) All the principals are

white. (Id. at 205) Webb was hired in 1962 and taught in

segregated black schools without incident until 1969. (Id.

at 10-12, 180, 190, 210.) In 1969, Webb was the first black

teacher assigned to Finley Elementary, a 90% white school.

(Id. at 99, 100) At the end of the 1972-73 school year,

Webb was reprimanded for paddling a white girl and ordered

not to paddle any students or to send them to the principal's

office. (_Id. at 16) Webb thereafter had difficulty maintain

ing discipline in his classes. (Id. at 20)

In the 1973-74 school year, Webb transferred to Newbern

Elementary as a "Practical Arts" teacher. (_Id. at 20) He

was the only black male teacher and one of four black teachers

out of 28 (id. at 190). The Practical Arts course, however,

lacked proper equipment or supplies (id. at 22, 79, 83), had

- 3 -

respect to the purposes of the hearing, counsel expressly-

stated. that: '

2/ Continued

too many students (id. at 21), and Webb was not paid a

promised supplement (id. at 22-23). White students and

parents complained about Webb's disciplinary measures.

(Id. at 78, 79, 152)

It was established that paddling was an accepted disci

plinary sanction in the Dyer County schools and used by most of

the teachers (id. 72, 99, 102, 113, 118, 125); teachers and

administrators believed paddling was necessary to maintain

discipline (î d. at 100, 103); there were no written guidelines

for use of paddling (id. at 122, 126); Webb, in the opinion of

numerous teachers, administrators and students who testified,

did not paddle students too harshly (id. at 72-73, 78, 81, 86,

113, 119, 124., 126); Webb was the only teacher to sometimes use

physical exercise as a more enlightened alternative to paddling

(id. at 106-107, 109-111); no other teacher had ever been repri

manded for paddling students or ordered not to paddle until

Webb (id. at 74-, 150, 151); Webb disciplined both black and

white students in the same way (id. at 78, 83); some white stu

dents did not respect Webb as a teacher (id. at 78, 79); and

the administration made no efforts to assist Webb or black

teachers in maintaining discipline with white students in the

wake of integration (id. at 161-62, 207, see 66, 159, 176-77).

No other teacher had ever been dismissed by the board for pad

dling. (id. at 86, 113, 123, 126).

Webb was given no support by administrators when white

parents complained to them about discipline (id. at 30, 162).

Webb was accused of improperly restraining a student who was

later suspended by the board for the incident. (_Id. at 224-25)

Newbern's principal assisted a white student whom Webb ordered

to stand in the hall without consulting Webb beforehand. (Id.

at 19) The Newbern principal admitted that the Practical Arts

course that Webb was assigned to teach lacked adequate equip

ment, supplies or structure for students, and that he did not

know how Webb could teach the class under those conditions.

(Id. at 216-22)

Objections were made to, inter alia, inadequate notice,

failure to provide a prior hearing, errors in assigning burden

of proof, bias, and failure to subpoena witnesses and Webb's

dismissal pending completion of hearing. (Id. at 1-9, 60, 88-90,

92-97, 136.)

4

We want the Board to make an honest

decision because we intend to pursue

[the dismissal]. We would prefer to

have it stopped here. If you all can

find it within your hearts and con

sciences and your reasonable intel

ligence [to] review ... objective[ly]

the evidence in this case to stop it

here. We would prefer that.

(Id. at 88) It was not until August 15, 1978, that the

board upheld their original action in dismissing Webb. Id.

Judicial Proceedings

On August 13, 1979, Webb filed this action for damages

and equitable relief against the board, its members, and

several administrators, to enforce rights guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment, and 4-2 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983, 1985,

1986, 1988 and 2000d (R. 2, Complaint, R. 3, Amendment to

Complaint, A. 8, 28). Pendent jurisdiction over state law ques

tions was invoked. (R. 2, Complaint, at p. 2, A. 10.)L The

complaint alleged that the board maintained employment poli

cies and practices which discriminated against black faculty,

including Webb, on the basis of their race. The complaint

stated that: The board had operated a racially segregated

school system through 1967. Only in 1967 had the board begun

to assign black teachers to formerly all white schools. Black

teachers were allegedly discriminated against in a variety

of ways including discharge. Both the substantive and proce

dural aspects of Webb's dismissal were alleged to be illegal

and discriminatory. Id. Responsive pleadings were filed,

including the board's answer and a motion to dismiss and/or for

5

summary judgment of several administrators (R. 46, 50,

A. 33, 38). Defendants also filed discovery requests.

(See docket sheet at pp. 4-5, A. 4-5.) Plaintiff Webb

filed, inter alia, the transcript of the administrative

proceedings in opposition to the motion to dismiss and/or

for summary judgment. (R. 73, Affidavit of Avon N.

Williams, Jr., A. 41.) The motion to dismiss was carried

with the case, and the case originally set for trial in

July 1981 and then reset for November 1981.

On October 14, 1981, the court below approved a consent

order of dismissal that:

This cause came on to be heard upon state

ment of counsel for the parties, as evidenced

by their signatures to this Order, that all

matters in controversy herein have been com

promised and settled by the payment to plain

tiff of the sum of $15,400.00 as damages at

law for the redress of his claims under 42

U.S.C. 1981 and by an award of equitable

relief as set out below, with all matters

relating to attorneh's fees of plaintiff being

expressly reserved.

IT IS, THEREFORE, BY CONSENT, ORDERED,

ADJUDGED AND DECREED as follows that:

1. Except as provided below, plaintiff's

action be, and the same is hereby, dismissed

with prejudice.

2. Defendant, County Board of Education

of Dyer County, Tennessee, will be treated as

having reinstated plaintiff, as of April 10,

1974, as a teacher in good standing in the Dyer

County, Tennessee School System, and plaintiff

will be treated as having immediately there

after resigned from said teaching position

without any derogatory personnel actions, marks

or implications upon or against his record as a

teacher or employee of said School System; and

the only reference said defendant, Board of Edu

cation of Dyer County, Tennessee, will furnish

to others, on request, will be limited to inclu

sive dates of service and positions held by

6

plaintiff with said Board of Education.

3. All matters relating to fees of counsel

for plaintiff are expressly reserved for reso

lution by agreement of the parties, or, in the

absence of agreement, by the Court.

(R. 79, A. 44 )

Counsel having failed to resolve the matter, plaintiff

Webb filed a motion for award of counsel fees and expenses

November 13, 1981 (R. 80, A. 46). An affidavit of Avon N.

Williams, Jr., describing services by date, nature of ser

vice and hours, an affidavit of Mr. Williams of expenses,

and a supporting memorandum were also filed (R. 81, 82, 83,

A. 4-7 , 57, 59 ). Plaintiff sought fees for 14-1.1 hours

for legal representation from April 1974 to September 1981

at Mr. Williams' current rate of $120 per hour and a 25%

increment for a total of $21,165.00 and expenses of $561.61.

The board submitted a memorandum and affidavits in opposi

tion to the motion. (R. 87, 88, A. 65 , 82 •) The board >

stated that no more than $5,000 in fees should be awarded. Id.

However, all three of the Memphis attorneys who submitted

affidavits on the board's behalf stated that it was rea

sonable for plaintiff's counsel to be compensated for legal

work in administrative proceedings, albeit at various rates

less than those requested. (R. 87, Affidavit of Russell X.

Thompson, Affidavit of Henry L. Klein, R. 88, Affidavit

of Allen S . Blair, A. 78, 80, 84.)

An evidentiary hearing was held December 18, 1981

(Docket sheet at p. 6, A. 6). At the hearing, plaintiff's

7

expert witnesses, Louis R. Lucas, Esq., and William E.

Caldwell, Esq., both of Memphis, Tennessee, presented uncon

tradicted testimony that time spent in the administrative

proceedings should be compensated for several reasons. (Id.

at 11, 13-17, 19-21 (Lucas), 40-41 (Caldwell), A. 109, 110-

14, 116-18, 129-30.) First, an administrative proceeding is

justified as part of the litigation-related discovery or

prefiling investigation in which facts are discovered,

witnesses identified, and positions are taken by the par

ties that are useful in laying the factual basis for the

complaint and ultimately the trial. In the instant case,

for instance, plaintiff was able to avoid formal discovery

efforts as a result of the administrative proceedings.

Second, counsel for the parties are able to assess the

strength of their cases on the basis of an administrative

record in order to weigh the risk of continued litigation

against settlement. That, in Mr. Lucas' opinion, occurred

in the instant case. Third, resolution of controversies

in the least expensive forum should be encouraged. If

fees are not awarded for administrative proceedings, then

the filing of lawsuits is encouraged. Fourth, administra

tive proceedings may result in relief short of litigation,

and it would be irresponsible to risk bringing a lawsuit

without pursuing prior administrative remedies. Pursuing

administrative remedies is especially appropriate in

8

teacher discharge cases where there is a long established

administrative procedure.

The court's findings of fact and conclusions of law

and order allowing attorney's fees and costs were entered

February 16, 1982. (R. 91, A. 86.) With respect to 82.8

hours of legal representation in administrative proceedings,

the court denied any fees solely on the legal ground that

the administrative proceedings were not a prerequisite for

the lawsuit. (R. 91, Findings at pp. 2-5, A. 87-90.) With

respect to 58.3 hours of legal work for the judicial pro

ceedings and five hours of work on the fees issue, the

court determined that fees of $9,73k.38 plus expenses of

3/

$739.61 were reasonable and allowable.

3/ Plaintiff’s counsel is an able and highly respected

attorney in the State of Tennessee and the United

States. The Court finds, upon the entire record

in this case, the fair market value of counsel's

service is $125.00 per hour across the board or a

fee of $7,287.50. The Court further finds, based

upon the entire record in this case, that a con

tingency factor of 25% is reasonable. The charges

by the Dyer County school officials against the

plaintiff, a tenured teacher, were serious charges.

Initially, the school board fired plaintiff. His

counsel timely requested a hearing before the school

board as required by Tennessee law. That heari/ig

was granted. The school board apparently held the

case under advisement for about four years and then

reaffirmed its initial decision to terminate plain

tiff. There certainly was a strong element of con

tingency in this case. The adjustment factor of

25% adds an additional $1,821.88 making plaintiff's

counsel fees $9,109.38. The Court also finds the

$561.61 itemization of expenses presented by plain

tiff to be reasonable.

(Cont1d )

9

This appeal and the board's cross-appeal were timely

filed (R. 94, 95, 97, A. 94,97,99).

ARGUMENT

The Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act of 1976,

42 U.S.C. § 1988, as amended, provides that:

In any action or proceeding to enforce a

provision of sections 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985,

and 1986 of this title, title IX of Public

Law 92-318, or title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, the court, in its discretion

may allow the prevailing party other than

the United States, a reasonable attorney's

fees as part of the costs.4/

It is undisputed that § 1988 applies to the instant case,

which was brought to enforce, inter alia, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981,

1983, 1985 and 1986 and Title VI, and that plaintiff Webb

3/ Continued

Plaintiff's counsel is also entitled to compensa

tion for *time related to litigating the fee issues

> before this Court. The Court will allow plaintiff's

counsel five (5) hours across the board or $625.00

for this time. In addition, plaintiff claims the

cost of a plane trip for counsel from Nashville to

Memphis to Nashville to be $146.00. Cost of rental

car was $32.00. The Court finds these expenses to

be reasonable and allowable.

It is therefore by the Court

t

ORDERED that plaintiff be and is hereby awarded

counsel fees in the total sum of $9,734.38 plus

expenses in the amount of $739.61.

Id. at pp. 6-7, A. 91-92.

4/ In 1980, Pub. L. 96-481 substituted "Pub. L. 92-318,

or title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964" for "Pub. L.

92-318, or in any civil action or proceeding, by or on behalf

of the United States of America, to enforce, or charging a

violation of, a provision of the United States Internal Rev

enue Code, or title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964."

10

is "prevailing party" entitled to "a reasonable attorney's

5/fees." Nor is there any dispute that the legal work per

formed by plaintiff's counsel in administrative proceedings

was reasonable and played a useful role in the eventual reso

lution of the lawsuit. The narrow controversy is whether a

prevailing party nevertheless should be precluded from

recovering fees for legal representation, the greater part

of the representation here, merely because the legal work

was performed in administrative proceedings.

The board argued and the lower court found that the

only issue before the court was an abstract technical ques

tion "whether the plaintiff is entitled to an award of

counsel fees for those hours pertaining to the administra

tive proceedings before the Dyer County Board of Education

where the proceeding was not a prerequisite to the filing

» of an action under 4-2 U.S.C. § 1981" (R. 91, Findings at17

p. 3, A. 88) (emphasis added), without reference to either

the terms of the statute, legislative history or statutory

purpose. That was a fundamental error. As this Court put

it, § 1988

11 - --——r-----------

5 / As the lower court stated, "defendants do not deny

that plaintiff's counsel is entitled to reasonable fees and

expenses." (R. 91, Findings at p . 2, A. 87.)

6/ In point of fact, the action was filed to enforce

several other civil rights provisions in addition to § 1981.

See supra at p. 2.

11

did more than simply enable the lower courts

once again to award fees; rather than being

an equitable remedy, flexibly applied rn

those circumstances which the court considers

appropriate, it is now a statutory remedy,

and the courts are obliged to apply the

standards and guidelines provided by the

legislature in making an award of fees.

Therefore, a close examination both of the

statute itself and its legislative history

is necessary.

Northcross v. Board of Education, 611 F . 2d 624-, 632 (6th Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 4-47 U.S. 911 (1980). The only proper

inquiry then is the statutory construction question whether

attorney's fees may be recovered for legal work performed

in the instant case in administrative proceedings where the

statute broadly provides that fees are allowable "[i]n any

action or proceeding to enforce" enumerated civil rights

provisions. See New York Gaslight Club, Inc, v. Carey, 4-47

U.S. 54.,. 61 (1980). Bartholomew v. Watson, 665 F . 2d 910 ( 9 th Cir . 1982 ) .

I .

The Statutory Language of § 1988 Permits

Recovery of Attorney's Fees for Legal

Representation in Administrative Proceedings.

Section 1988 plainly provides that - attorney' s fees are

permitted "[i]n any action or proceeding to enforce" the

relevant civil rights provisions. These terms have been

authoritatively construed by the Supreme Court in a series

of recent cases. In New York Gaslight Club, Inc, v. Carey,

supra, 4.4-7 U.S. at 61-63, the Court construed the term "pro

ceeding" in § 706k of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

12

1964., 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) , the parallel attorney's fees

provision for Title VII employment discrimination cases,

and found that "[t]he words of § 706(k) leave little doubt

that fee awards are authorized for legal work done in 'pro

ceedings' other than court actions." 447 U.S. at 61. The

Carey analysis of statutory language is highly relevant

because § 1988 "is legislation similar in purpose and design

to Title VII's fee provision." Carey, supra, 447 U.S. at

70 n. 9 (citing H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, pp. 5 and 8 n. 16

(1976)). Thus, "Congress' use of the broadly inclusive

disjunctive phrase 'action or proceeding' indicates an

intent to subject the losing party to an award of attorney's

fees and costs that includes expenses incurred for admin

istrative proceedings" and "[i]t cannot be assumed that the

words 'or proceeding' in § 706(k) are merely surplusage."

448 U.S. at 61. This analysis of the same term in a sister

fees provision in the same title of United States Code obvi

ously applies here. The term "or proceeding" broadens the

scope of entitlement to attorney's fees beyond court actions.

If Congress intended to limit recovery of fees under § 1988

to lawsuits, it could easily have done so by omitting "or

proceeding" as Congress did with respect to § 204(b) of

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-

3(b), another provision in the same title of the Code. Carey,

supra, 447 U.S. at 61; Bartholomewv. Watson, supra, 665 F .2d at 913.

The lower court, however, concluded that, notwithstanding

13

§ 1988 allowance for recovery of fees in administrative

proceedings, attorney's fees should not be recoverable

where exhaustion of the administrative proceedings is not

a statutory precondition or prerequisite. Clearly, § 1988

makes no such exception. The plain face of the statute,

moreover, indicates otherwise. The broad "action or pro

ceedings" term is used in § 1988, without limitation, to

refer both to provisions such as Title VI or Title IX where

administrative proceedings are expressly set forth as part

of the enforcement scheme, and to provisions such as

§ 1981 or § 1983, where such proceedings are not expressly

set forth. Indeed, there is absolutely no support for any

exhaustion limitation on fees for administrative proceedings

work because Title VI or Title IX, unlike Title VII, do

not require administrative exhaustion as a precondition to

filing a judicial action. Cannon v . University of Chicago,

441 U.S. 677, 706 n. 41 (1979); NAACP v. Medical Center, Inc.,

599 F .2d 1247 (3d Cir. 1979). Therefore, if § 1988 is read

as the court below read it, no fees for administrative pro

ceedings would be authorized. That reading would be absurd.

See Carey, supra.

The term "proceeding" is given equal weight with the

term "action," indicating that Congress did not intend to

limit coverage to administrative proceedings which need

to be exhausted prior to the filing of a lawsuit. If Con

gress had intended to restrict allowance of fees only to

14

such proceedings, it could easily have done so by refer

ring only to such subsidiary proceedings. Congress did not

do so. Indeed, as discussed below, it expressly chose to

use other terms which broaden rather than narrow the cate

gory of "proceedings" covered by § 1988.

Thus, section 1988 plainly authorizes a fees award-to

the prevailing party "[i]n any ... proceeding to enforce"

civil rights provisions (emphasis added), plainly indicat

ing that the term proceeding was broad and inclusive. In

Maine v. Thiboutot, 4-4.8 U.S. 1, 9 (1980), the Court considered

claim similar to the administration exhaustion limitation

relied on by the lower court, i .e ., petitioners argued that

Congress did not intend statutory claims, as opposed to

constitutional claims, to be covered by § 1988. The Court

resolved the question by reference to the statute:

[T]he plain language provides an answer.

The statute states that fees are available

in any § 1983 action. Since we hold that

this statutory action is properly brought

under § 1983, and since § 1988 makes no

exception for statutory § 1983 actions,

§ 1988 plainly applies to this suit.

448 U.S. at 9 (original emphasis). Just as § 1988 makes no

exception for certain § 1983 actions it makes no exception

for certain administrative proceedings. Just as "§ 1988

applies to all types of § 1983 actions," Maher v. Gagne,

448 U.S. 122, 128 (1980), it applies as well to all types

of administrative proceedings.

The court below, furthermore, did not merely ignore

'&S4&+K***:

the plain terms of § 1988. It erroneously relied on a

term not present in the statute by assuming that "pro—»

ceedings under this title" appears in § 1988 as well as

§ 706(k) . (R. 91, Findings at 4., A. 89.) However, unlike

Title VII's provision which restricts allowance of fees to

"proceedings under this title" (emphasis added), § 1988

liberally authorizes attorney's fees "[i]n any ... pro

ceeding to enforce" the civil rights provisions (emphasis added) .

Proceedings § 1988 refers to need not fall "under" the

civil rights provisions set forth in § 1988 in the sense

of being expressly specified as part of the enforcement

scheme as are Title VII administrative proceedings. Rather,

the use of the more inclusive term "to enforce" indicates

that fees are authorized for proceedings which in effect

implement or achieve the "substantive rights" or "remed[ies]"

set forth in the enumerated civil rights provisions. Maher

v. Gagne, supra, 448 U.S. at 129 n. 11 (construing "to

enforce [§ 1983]"). Section 1988 is result-oriented and

conditions fees recovery on enforcement alone rather than

resort to any specific procedure. Unlike the Title VII

statute, the civil rights provisions for which fees are

authorized by § 1988 do not have specific enforcement

mechanisms. Federal claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, for

instance, may be enforced through unspecified state proce

dures. Martinez v. California, 444 U.S. 277, 283 n. 7

(1979). Thus, the legislative history specifically refers

16

etr VI 9* '&!****• rxr*?***mp:&&*

to "[a] party seeking to enforce the rights protected by

the statutes covered by [§ 1988]," "the party or parties

seeking to enforce such rights" and "parties may be con

sidered to have prevailed when they vindicate rights

through a consent judgment or without formerly obtaining

relief. S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 4-5

(1976) (emphases added).

The lower court's reliance on any restriction imposed

by the "under this title" language of § 706(k), in any event,

is erroneous as a matter of Title VII law. Courts of

appeals have construed § 706(k) as not being limited to

administrative provisions expressly authorized by Title

VII. Chrapliway v. Uniroyal, Inc., 670 F .2d 760, 765-67

(7th Cir. 1982) (§ 706(k) permits fees for legal work per

formed by counsel in Title VII cases to persuade federal

government to debar defendant from its federal contracts

in separate proceeding because "the plaintiffs' pursuit of

debarment was a service which contributed to the ultimate

termination of the Title VII action, and in that sense was

within the Title VII action," 670 F.2d at 767); Sullivan v .

Com. Pa. Dept, of Labor, 663 F.2d 443 (3d Cir. 1981) (§ 706

(k) authorizes fees for prevailing in arbitration proceed

ing in connection with Title VII judicial and administrative

proceedings where "by so prevailing, [plaintiff] may be

deemed to have prevailed in her Title VII lawsuit because

of its impact on, and material contribution to, the ultimate

17

" r u a * >V;'.+ * k - . » a « a « r i

relief she obtained," 663 F.2d at 4-51); Kulkarni v. Alexander,

662 F.2d 758 (D.C. Cir. 1978) (although § 706(k) authorizes

fees "only if that litigation brought under Title VII (as

is the present action) the literal terms of that clause

do not preclude consideration in setting the award of ser

vices rendered in so closely and integrally connected a

prior non-Title VII case as the first suit there" and prior

administrative proceedings. 662 F.2d at 766).

II.

Legislative History Supports Recovery of

Attorney's Fees for Legal Representation

in Administrative Proceedings.

The lower court failed to conduct any review of § 1988 's

legislative history. This Court, however, has observed that

§ 1988 "is a rare statute with sufficient legislative his

tory to provide '[a] clear-cut indication that Congress

considered [many of] the exact problem[s] with which we are

now confronted and provided an express indication as to how

the general language of the 1976 statute was intended to be

applied..Under such circumstance (relatively rare in this

court's experience), we, of course, follow Congressional

intent.'" Northcross, supra, 611 F .2d at 633, quoting Seals

v. Quarterly County Court, 562 F.2d 390, 394- (6th Cir. 1977).

While § 1988 legislative history does not separately

discuss entitlement to fees in administrative proceedings,

it does refer to that entitlement in the context of authoriz

ing fees when the "prevailing party," in practice, obtains an

18

IT. *><!»*« -.rant

informal resolution even if that resolution results from a

separate or collateral proceeding, a broader category which

by definition includes administrative proceedings. Thus,

the House Report states that:

The phrase "prevailing party" is not

intended to be limited to the victor only

after entry of a final judgment following a

full trial on the merits. It would also

include a litigant who succeeds even if the

case is concluded prior to a full evidentiary

hearing before a judge or jury. If the liti

gation terminates by consent decree, for

example, it would be proper to award counsel

fees. ... Parker v. Matthews, 4-11 F. Supp.

1059 (D. D.C. 1976). ... A "prevailing"

party should not be penalized for seeking

an out-of-court settlement, thus helping

to lessen docket congestion.

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94-th Cong., 2d Sess. 7 (1976). Parker,

which was subsequently affirmed sub nom.'Parker v. Califano,

561 F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir. 1977), was a Title VII case somewhat

similar to the instant case. There plaintiff filed a lawsuit

after unsuccessful administrative proceedings. However, after

the filing of the court action, the lawsuit was settled after

administrative decision favorable to the plaintiff. The

court found that plaintiff was prevailing party by virtue of

the settlement and that fees should include time spent in

administrative proceedings. 411 F. Supp. at 1065-66.

Similarly, Maher v. Gagne, supra, 448 U.S. at 129, points

out, "the Senate Report expressly stated that 'for purposes

of the award of counsel fees, parties may be considered to

have prevailed when they vindicate rights through a consent

judgment or without formally obtaining relief,'" quoting,

19

S. Rep. No. 94-1101, supra at 5 (omitting citations). Among

the cases expressly cited by the Senate Report was Thomas v .

Honeybrook Mines, Inc., 428 F .2d 981 (3d Cir. 1970), cert ♦

denied, 401 U.S. 911 (1971), in which fees from a common

fund, resulting from trustees' delinquency lawsuits against

delinquent mine operators, were allowed to a coal miners'

pension committee which sued the trustees in a wholly sep

arate lawsuit and forced the trustees to bring the fund-

producing delinquency lawsuits. In justifying the award,

Thomas stated that the attorney's fees rule "should not be

applied in a narrow technical manner." 428 F .2d at 985.

This Court in Northcross, supra, 611 F.2d at 636, expressly

permitted recovery in circumstances similar to those in the

Thomas case on the basis of the Senate Report's expression of

Congressional will that § 1988 be interpreted "in a practical,

not formal, manner."

The district court also cut certain hours

from the plaintiffs' request against the City

of Memphis, primarily those hours spent on the

suit which had been filed against the city but

which was dismissed when the City agreed to

supply adequate gasoline to the School Board.

In spite of the lack of a formal order, the

plaintiffs still obtained the relief which

they sought, and are entitled to compensation.

As noted in the Senate Report, prompt and rea

sonable settlement is to be encouraged, and

thus the notion of "prevailing party" is to be

interpreted in a practical, not formal, manner.

Id. See Chrapliway, supra; Sullivan v. Com. Pa. Dept, of

Labor, supra; Kulkarni, supra. In neither Thomas nor North-

cross was the judicial character of the independent proceedings,

20

for which fees were allowed, of any significance.

Moreover, in 1980 Congress enacted the Equal Access to

Justice Act, Pub. L. 96-481, 5 U.S.C. § 504, allowing "pre

vailing parties" fees in certain federal agency proceedings.

The legislative history indicates that:

The phrase "prevailing party" is not to

be limited to a victor only after entry

of a final judgment following a full

trial on the merits; its interpretation

is to be consistent with the law that

has developed under existing statutes.

A party may be deemed prevailing if

the party obtains a favorable settlement

of his case, Foster v. Boorstin, 561

F .2d 340 (D.C. Cir. 1977) .

H. Conf. Rep. No. 96-1434, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. 21 (1980);

compare H.R.' Rep. No. 96-1418, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. 11

7 /(1980).- Foster, like Parker v. Matthews, supra, was a

Title VII case in which a lawsuit was filed after unsuccess

ful administrative proceedings and then settled after an

administrative proceeding in plaintiff's favor. As in

Parker, the court ruled that the attorney's fees award

should include compensation for services rendered at the

administrative level. 561 F .2d at 344.

Thus, § 1988 legislative history, as buttressed by the

subsequent Equal Access to Justice Act legislative history,

evidences Congressional intent to allow a prevailing party

recovery of attorney's fees for administrative proceedings

7/ As noted above at p . 10 n. 4, supra, Pub. L. 96-481

amended § 1988.

21

as well as other proceedings collateral to the lawsuit which

substantially contribute to informal resolution of the law

suit .

Section 1988 legislative history, in addition, states

that "the amount of fees awarded under [§ 1988] be governed

by the same standards which prevail in other types of

equally complex Federal litigation, such as antitrust

cases," S. Rep. No. 94.-1011, supra at 6, quoted in North-

cross, supra, 611 F.2d at 633. The rule in such litigation,

see Thomas v. Honeybrook Mines, Inc., supra, 428 F.2d 985,

and cases cited therein, and Sullivan v. Com. Pa. Dept, of

Labor, supra, 663 F.2d at 447-54, and cases cited therein,

is that fees are recoverable for legal representation in

collateral proceedings which, as a practical matter, lead

to informal resolution of the lawsuit in which fees are

being sought. This legislative history, thus, suggests

that courts, in construing § 1988 in this respect, should

look to substance and not form just as they would in

authorizing awards of attorney's fees in other areas of the

law. See Brown v. Bathke, 588 F.2d 634, 637 (8th Cir. 1978).

Moreover, legislative history "comments that in accord

ance with the law established under the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, the prevailing party should 'ordinarily recover an attor

ney's fees under special circumstances would render such an

award unjust.'" Northcross, supra, 611 F .2d at 633;

Bartholomew v. Watson, supra, 665 F.2d at 913:

22

It is intended- that standards for

awarding fees be generally the same as

under the fee provisions of the 1964.

Civil Rights Act. A party seeking to

enforce the rights protected by the

statutes covered by [§ 1988], if success

ful, "should ordinarily recover an

attorney's fee unless special circum

stances would render such an award

unjust." Newman v. Piggie Park Enter

prises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968).

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, supra at 4. That Congressional intent

obviously would best be enforced by authorizing fees for

administrative proceedings pursuant to § 1988 in light of

New York Gaslight Club, Inc, v. Carey, supra, and other

Title VII cases. Bartholomew v. Watson, supra, 665 F .2d at

913. Prior to Carey, the lower federal courts virtually

without exception allowed fees to plaintiffs who prevailed

through administrative proceedings, whether plaintiffs

participated in administrative proceedings after the lawsuit

8/

was filed, obtained partial relief in administrative pro-

9/ '

ceedings and then won further relief in a lawsuit, or

obtained relief in administrative proceedings and then

10/

sought court-awarded fees. Nor have courts limited the

entitlement to fees under the Title VII provision to Title

8 / See, e.g., Foster v. Boorstin, supra; Parker v .

Matthews, supra.

9/ See, e.g., Fischer v. Adams, 572 F.2d 406 (1st Cir.

1978).

10/ See, e.g., Carey, supra; Booker v. Brown, 619 F.2d 57

(10th Cir. 1980); Richards v. Reed, 611 F .2d 545 (5th Cir.

1980); Johnson v. United States, 554 F.2d 632 (4th Cir. 1977)

Smith v. Califano, 446 F. Supp. 530 (D. D.C. 1978).

23

VII administrative proceedings. See Chrapliway v. Uniroyal,

Inc., supra, 670 F.2d at 765-67 (efforts to persuade federal

government to bring proceeding to debar employer from federal

contracts); Sullivan v. Com, of Pa. Dept, of Labor, supra,

663 F.2d at 4-4.7-52 (arbitration proceeding); Kulkarni v .

Alexander, supra, 662 F .2d at 765-66 (non-Title VII case).

Certainly, no special circumstances render recovery unjust.

Last, nothing in the legislative history supports, or

even hints at, any limitation of § 1988's authorization of

fees to administrative proceedings which must be exhausted

prior to suit. Such an intent is wholly absent.

In sum, all relevant legislative history evidences

Congressional intent to enact an attorney's fees provision

that should be implemented in a liberal and practical

fashion, including the broad authorization of fees for

administrative proceedings, to encourage vigorous enforcement

of civil rights provisions. Legislative history, therefore,

is entirely consistent with the broad plain terms of the

statute itself.

III.

Permitting Recovery of Attorney's Fees for

Legal Representation in Administrative Pro

ceedings Fulfills the Purposes of the Statute.

Congress stated that the purpose of § 1988 is to facili

tate enforcement of the civil rights laws.

The purpose and effect of [§ 1988] are

simple— it is designed to allow courts to pro

vide the familiar remedy of reasonable counsel

24

fees to prevailing parties in suits to

enforce the civil rights acts which

Congress has passed since 1866. ... All

of these civil rights laws depend heavily

upon private enforcement, and fee awards

have proved an essential remedy if pri

vate citizens are to have a meaningful

opportunity to vindicate the important

Congressional policies which these laws

contain.

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, supra at p. 2. "Congress expressly

commands the courts to use the broadest and most effective

remedies available to them to achieve the goals of the

civil rights laws. ... The goal to be achieved... is to

make an award of fees which is 'adequate to attract compe

tent counsel, but which do not produce windfalls to attorneys.'"

Northcross, supra, 611 F .2d at 633, citing S. Rep. No. 94-1011,

supra.

Permitting plaintiff Webb attorney's fees for administra

tive representation in the instant case facilitates civil

rights enforcement. An administrative proceeding often pro

vides a more expeditious, less costly and less formal remedy

than a court action. See supra at pp. 8-9 (expert testimony).

A rule which limits fees for administrative representation

obviously runs contrary to the thrust of § 1988 to encourage

enforcement by forcing civil rights complainants to pass up

legitimate opportunities for informal resolution through

administrative remedies. Moreover, the administrative proce

dures established by the Tennessee teacher tenure law, which

plaintiff Webb invoked, were characterized by this Court as

25

in form "comprehensive" and providing "procedural due pro

cess for tenured teachers." See, e .g ., Sullivan v. Brown,

54-4. F .2d 279, 284. (6th Cir. 1976) (admonishing teacher to

avail herself of state remedies and not "to make a federal

case out of this litigation"). While plaintiff Webb did

not prevail in the administrative proceedings, he might

have been remiss in passing up the opportunity for informal

resolution. As the court below found, it was appropriate

to invoke tenure law provisions and the Dyer County Board

of Education apparently gave Webb's complaint serious con-

11/sideration. Certainly, Webb "should not be penalized for

seeking an out-of-court settlement, thus helping to lessen

[federal court] docket congestion." H.R. Rep. No. 94.-1558,

supra at 7.

Moreover, uncontradicted testimony establishes that

the record of administrative proceedings played a role in

the eventual settlement of the lawsuit. 'Thus, all three of

the board's experts agreed that it was reasonable and appro

priate to compensate plaintiff Webb's counsel for administrative

11/ The court found that:

The charges by the Dyer County school officials

against the plaintiff, a tenured teacher, were

serious charges. Initially, the school board

fired plaintiff. His counsel timely requested

a hearing before the school board as required by

Tennessee law. That hearing was granted. The

school board apparently held the case under

advisement for about four years and then reaf

firmed its initial decision to terminate plaintiff.

(R. 91, Findings at p . 6, A. 90.)

26

representation. See supra at p. 7. Plaintiff Webb pre

sented undisputed evidence that the administrative proceed

ing was essentially discovery or prefiling investigation

and provided the basis to define the settlement posture of

the parties. See supra at pp. 8-9. Although Webb did not

prevail before the board, the administrative record made

clear to defendant board that plaintiff Webb had a substan

tial case and that the board might not wish to risk litiga

tion. See supra at pp. 3-k, n. 2 (summary of administrative

record). Cf., Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School Dis

trict, 608 F .2d 59k (5th Cir. 1979). Certainly, if, instead

of pursuing his administrative remedies, plaintiff Webb had

filed a federal action and compiled the same record, no

question would arise as to entitlement for fees. Enforce

ment of the civil rights laws clearly would be enhanced

where, as here, plaintiff uses administrative mechanisms

that benefit his federal court case. Indeed, the Supreme

Court has noted that:

Prior administrative findings made with

respect to an employment discrimination claim

may, of course, be admitted as evidence at a

... trial de novo. See Fed. Rule Evid. 803

(8 ) (c ). Cf. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

kl5 U.S. 36, 60 n. 21. Moreover, it can be

expected that, in light of the prior admin

istrative proceedings, many potential issues

can be eliminated by stipulation or in the

course of pretrial proceedings in the District

Court.

Chandler v. Roudebush, k25 U.S. 8k0, 853 n. 39 (1976). Where,

as here, the only factual basis for a judicial settlement is

27

the administrative record, the case is even more compelling

that the denial of fees inhibits enforcement. See, e.g.,

Parker, supra; Foster v. Boorstin, supra.

The Supreme Court's reliance on a similar enforcement

purpose in its analysis of § 706(k) authorization for fees

in state administrative proceedings in New York Gaslight

Club, Inc, v. Carey, supra, is instructive:

Countering a contention that only federal

and not state "proceedings" were included

within the protection of section 706(k),

the Court stressed the purpose of section

706(k), the humanitarian and remedial poli

cies of Title VII, and the statute's

structure of cooperation between state and

federal enforcement authorities. 4-4-7 U.S.

at 61, 100 S.Ct. at 2029, 64- L.Ed.2d at

733. The Supreme Court stated that failure

to award fees for mandatory state proceed

ings would inhibit the enforcement of a

meritorious discrimination claim. Id. 4-4-7

U.S. at 63, 100 S.Ct. at 2030, 64 L.Ed.2d

at 734.

The same factors which support ^n award

of fees for related s£ate proceedings under

section 706(k) militates for an award for

timely related state court actions under

section 1988; 42 U.S.C. § 1983 has the same

broad humanitarian and remedial aspect as

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., and the purpose

of the fee award in both civil rights actions

is to aid in the enforcement of those rights.

The Senate Report on section 1983 admonishes

the courts to "use the broadest and most

effective remedies available to achieve the

goals of our civil rights laws." S.Rep. No.

94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 3, reprinted

in [1976] U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 5908,

5910-11. It further declares that a pre

vailing party "'should ordinarily recover

an attorney's fees unless special circum

stances would render such an award unjust.'"

Id. at 5912 (quoting Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402, 88

S.Ct. 964, 966, 19 L.Ed.2d 1263 (1968)).

28

rftt :T .v>t w r i - r n n - r i ~ - ,'n r * r - '— !>------------

This circuit has stated: "Congress' purpose

in authorizing fee awards was to encourage

compliance with and enforcement of the civil

rights laws. The Fees Awards Act must be

liberally construed to achieve these ends."

Dennis v. Chang, 611 F .2d 1302, 1306 (9th

Cir. 1980).

Bartholomew v. Watson, supra, 665 F.2d at 913. (While

Bartholomew concerned authorization of fees for state

court proceedings, Carey, supra, 4.-47 U.S. at 56-58, 68-

70, itself concerned independent state administrative pro

ceedings to which Title VII defers.)

Moreover, as discussed above, supra at pp. 18-22,

§ 1988 favors informal resolution of civil rights disputes,

and fees are expressly authorized for all kinds of proceed

ings which result in a successful conclusion to the litiga

tion short of formal judicial judgment. See, e .g ., Maher

v . Gagne, supra, 448 U.S. at 129. Permitting awards of

attorney's fees for all settlements but for some administra-

tive proceedings is anomalous and surely does not enforce

the purpose of § 1988 to foster informal resolution. Admin

istrative proceedings are a ready mechanism for fostering

informal resolution of disputes. That is their very rationale.

In the instant case, for instance, although the administra

tive proceedings did not themselves result in a satisfactory

disposition, the administrative record helped advance the

eventual court-approved settlement, saving the parties fur

ther time and expense, and the public the unnecessary diver

sion of judicial resources. See supra at pp. 26.-28. Moreoyer,

29

there is no valid or meaningful distinction between admin

istrative proceedings which are required to be exhausted

and administrative proceedings which need not be exhausted

for purposes of fashioning informal resolution. As a

recent learned treatise on attorney's fees persuasively argues:

In view of the emphasis in the Fees Act

on voluntary resolution of legal disputes,

on awarding fees to plaintiffs who prevail

through settlements, and on awarding fees

to plaintiffs who act as catalysts, the

fact of the matter is that in awarding fees

there is no logical or legal difference

between plaintiffs who must invoke cer

tain non-judicial proceedings and those

plaintiffs who may invoke such proceed

ings. And, since the word "proceeding" is

weighted equally with the word "action" in

the fee shifting statutes, it should not

be limited only to administrative or judi

cial exhaustion proceedings.

E. Larson, Federal Court Awards of Attorney's Fees 76 (1981).

The lower court, however, ignored statutory purpose

as well as the face of the statute and legislative history.

Instead, the court merely relied on the fact that Carey con

cerned "services performed in a state administrative proceed

ing that Title VII requires the claimant to invoke" (R. 91,

Findings at 3, A. 88) (original emphasis). Certainly, it

is true that the precise administrative proceedings at issue

in Carey were required to be exhausted by Title VII. How

ever, it is equally true that Carey does not hold that fees

are authorized under § 706(k) only where administrative pro

ceedings are a statutory prerequisite to a Title VII action. See

Bartholomew v. Watson, supra, 665 F .2d at 913; Chrapliway

30

v. Uniroyal, Inc., supra, 670 F.2d at 766-67; Sullivan v.

Com, of Pa. Dept, of Labor, supra. Carey is significant in -

the assistance it affords the court in construing § 1988

and "in indicating that the statute should be liberally

rather than restrictively interpreted with respect to fees

for services not performed, in the ordinary sense, in pro

ceedings before the Title VII court." Chrapliway, supra,

670 F .2d at 767. Carey, of course, is not dispositive since

12/

§ 1988 is broader than § 706(k). Moreover, the analysis

of Maher v . Gagne, supra, 4-4-8 U.S. at 129, on § 1988' s

authorization of fees for informal resolution efforts, con

trary to the district court, obviously is relevant to

determining whether fees are authorized for administrative

proceedings, one of the means of effecting an informal

13/resolution.

12/ While § 1988 broadly authorizes fees "[i]n any ... pro

ceeding to enforce" enumerated civil rights provisions,

§ 706(k) fees are limited to "proceedings under" Title VII.

See supra at 16-18. Thus, Carey necessarily did not directly

address the question of the authorization of § 1988 for fees

in a "proceeding to enforce" civil rights provisions.

13/ The district court relied on two other cases. Blow v .

Lascapis, 50 U.S.L.W. 2178 (N.D. N.Y. 1981), affirmed, 668

F .2d 670 (2dT Cir. 1982), as the lower court recognized, is

not directly in point. (R. 91, Findings at 5, A. 90.) The

issue in Blow was whether a plaintiff could bring an inde

pendent action solely for an award of fees in federal court

after prevailing in state proceedings. In the instant case,

like Bartholomew v. Watson, supra; Chrapliway, supra;

Sullivan v. Com, of Pa. Dept, of Labor, supra, plaintiff did

not sue for fees alone. Instead, Webb obtained relief only

after filing his lawsuit through a court-approved settlement,

and then sought fees for both court and administrative repre

sentation because the ancillary administrative proceedings

- 31 -

- ■—<,is. - .v - . -: *T»: TTZJT

CONCLUSION

The judgment and findings of fact and conclusions of

law and order allowing attorney's fees and costs, to the extent

attorney's fees in administrative proceedings were denied,

should be vacated, and the case remanded for a determina

tion of the amount of attorney's fees to be awarded for

14/

legal representation in administrative proceedings.

13/ Continued

contributed to the judicial settlement. Swain v. Secretary

of Navy, 50 U.S.L.W. 2439 (1982), as the Court itself recog

nized, concerned neither § 1988 nor § 706(k), but the fees

provision of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act. (R.

91, Findings at p. 5, A. 90.)

Authorizing an award of fees to plaintiff Webb would not

require the Court to decide any of the issues addressed by Blow

or Swain.

14/ Alternatively, the Court may wish to determine the fees in

light of the clear legal error, the clear record below and the

district court's determination of reasonable attorney's fees

for court work, including the fair market value of counsel's

services and the reasonableness of a contingency factor of 25%.

See Monroe v. Bd. of Com'rs of City of Jackson, 581 F.2d 581,

582 (6th Cir. 1978); Brown v. Culpepper, 561 F .2d 1177 (5th

Cir. 1977).

RICHARD-H. DINKINS

203 Second Avenue North

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

JACK GREENBERG

BILL LANN LEE

DEBORAH FINS

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant-

Cross- Appel lee

32

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

Undersigned counsel for plaintiff-appellant-cross-

appellee certifies that copies of the foregoing Brief for

Plaintiff-Appellant-Cross-Appellee were served on counsel

for the parties by prepaid Federal Express guaranteed next

Olen C. Batchelor, Esq.

Holt, Batchelor, Spicer & Ryan

Suite 2400 - 100 North Main Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Thomas R. Prewitt, Esq.

Armstrong, Allen, Braden, etc.

Suite 1900 - One Commerce Square

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Melvin T. Weakley, Esq.

First Citizens National Bank

Dyersburg, Tennessee 38024

day delivery, addressed to:

This 9th day of June, 1982.

torney for Plaintiff-Appellant-

Cross-Appellee

33

* «« r