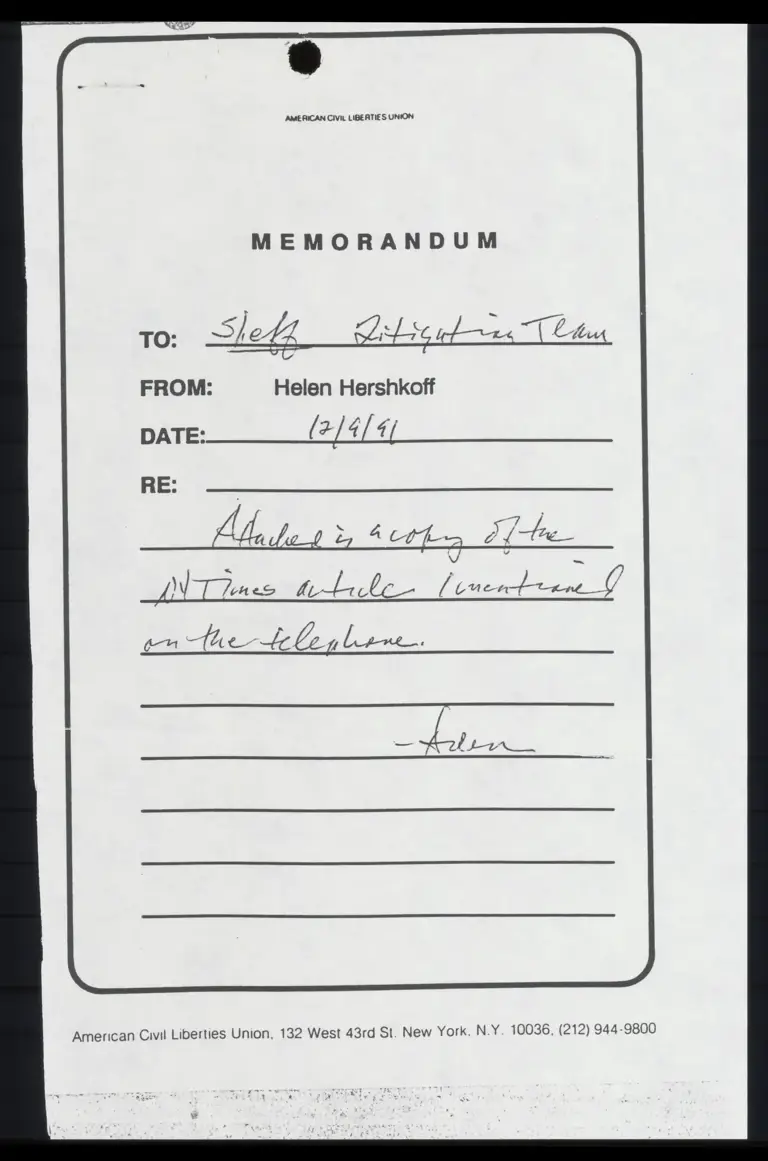

Memo from Hershkoff to Counsel with New York Times Article

Press

December 9, 1991

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Memo from Hershkoff to Counsel with New York Times Article, 1991. ba398ac5-a346-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2651a3de-53be-44ae-bdd3-b8c448922edb/memo-from-hershkoff-to-counsel-with-new-york-times-article. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

MEMORANDUM

TO:

FROM: Helen Hershkoff

DATE: (#]4/4]

RE:

Alte y derf Jt

INT Tones lioLake Eel

tl {2 tele y borne

ry throng

& £3

American Civil Liberties Union, 132 West 43rd St. New York, N.Y. 10036, (212) 944-9800

BT EN TW a EL A BE RP SITU rs a _———.. ans EY a 3 Er BE RR XT SN

5 PWRER FEVARAEY SEE RO 1 BRT NER YES FE A La al A Lei Sie or

STUDENTS/SCHOOLS

School Segregation Case

Too Knotty, Lawyers Say

Lawsuit in Hartford Raises Complex Issues

By GEORGE JUDSON

Speciai to The New York Times

NEW BRITAIN, Conn., Npv. 21 —

Lawyers for the state argugd today

that a lawsuit attacking the de facto

segregation that divides Hartford

from its suburbs raises questions of

social policy far too sweeping and

complex for a single judge to decide.

Assistant Attorney General John R.

Whelan also said the state should not

be held responsible for segregation

that arises out of residential patterns,

rather than from intentional govern-

ment policies like the Jim Crow prac-

tices of the South before the 1960's.

He said the complexity of the case,

and the novel legal theories that a

team of civil rights lawyers is using

in its effort to force the integration of

suburban schools with the city’s, re-

quire the case to go first to the state

Supreme Court, to resolve conflicting’

interpretations of the law.

Otherwise, he said, a trial would be

‘““an expensive and fruitless exercise

that would be more likely to do harm

than produce positive resuits.”

Constitution Violated

The lead lawyer for the plaintiffs,

Wesley W. Horton, responded that the

issue is not the complex social and

economic conditions that result in

overwhelmingly minority city

schools, surrounded by overwhelim-

ingly white suburban schools.

The issue, he said, is that Hart-

ford’s public schools are 91 percent

black and Hispanic, and that the seg-

regation violates Connecticut's con-

stitution by denying those students

equal educational opportunity with

suburban children.

“If a school is 91 percent minority,

that is intolerable regardless of why

it occurred,” Mr. Horton said.

Today was the second time that

lawyers for the state have tried to

block the lawsuit, known as Sheff v.

O'Neill, from proceeding to trial. The

case is named after Milo Sheff, a

black Hartford student, and William

A. O'Neill, who was governor When

the suit was filed in 1989. .

In 1990 the Superior Court judge in

the case, Harry Hammer, rejected-

similar arguments as the state]

sought a dismissal: that the state

government is not to blame for the de

facto school segregation in Hartford:

and other cities; that there are no

clear-cut solutions for a judge to

adopt, and that the state, in any case,

has taken some steps to help city

schools and achieve racial balance. -

The issues are so sweeping, Mr.

Whelan said, embracing education,.

housing, poverty and even public

health, that they are best handled by.

the Legislature.

“What is being suggested is a dra-"

Poverty, housing

and public health

are all involved in

Sheffv. O'Neill.

a0

on

SS

W,

3

matic expansion of the powers of the

court,” he said. -

Mr. Horton and other lawyers in-

volved in the suit readily admit they

seek to break new ground by over-

coming a United States Supreme

Court barrier, from a 1974 case im

volving Detroit, to integrating schools.

by busing students across city lines.

The Sheff case is based on the:

Connecticut Constitution. If a judge:

accepts the lawyers’ arguments that.

the Constitution bars segregation —.,

de facto, as well as intentional — and

guarantees equal educational oppor-

tunity, Mr. Horton and other lawyers.

say the state has the authority to

order any remedy necessary, inciud-

ing the busing of children across the

Hartford city line.

The tangled nature of desegrega-

tion in Connecticut could be seen in

court as Mr. Whelan acknowledged

that the state has all the powers it

needs to order regional school dis-

tricts as a way to achieve integration.’

Mr. Whelan also acknowledged that

Connecticut has seen fit in the recent

past to order towns and cities to bal--

ance the racial composition of all

schools within any one district — re--

gardless of the reason for an imbals

ance.

Just this month, Mr. Whelan suc-

cessfully argued before another Supe-~

rior Court judge a case against Wa-.

terbury in which the state’s authority

to enforce its racial balance law was

upheld in court for the first time.

Judge Hammer, at times, appeared

intrigued by Mr. Whelan's dual role,

arguing in one case for a court order

forcing the city of Waterbury to re-

dress the de facto segregation in its

schools, and arguing here that the

state should not be similarly ordered

to end the de facto segregation that

divides its local school districts. 4

“I have a brief in the Waterbury

case that could have been written by

‘Mr. Horton,” Judge Hammer told the

assistant attorney general.

A Meaningless Law?

Connecticut is one of the few states

in the nation to have adopted a racial

balance law, but even this pioneering

step has been attacked by the Sheff .

lawyers.

They say that limiting desegrega-

tion efforts to individual towns and

cities makes the law meaningless ir

‘ cities like Hartford, where there is no

significant white enrollment, and °

‘leads to white flight — and intensified _

segregation — in other cities. :

“When a white parent sees his child -

will go to a 90 percent minority °

school, and sees that neighboring sub- *

urbs aren’t contributing, he'll just go

to one of those towns,’ Mr. Horton -

said. “

If Judge Hammer rules against the-

state after today’s arguments, a trial

is likely to be scheduled for somé™

time in 1992.