Sweatt v. Painter Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 31, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sweatt v. Painter Brief Amici Curiae, 1950. bef84f97-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2681f13f-5e1e-4d38-a681-2b6ea5533af5/sweatt-v-painter-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

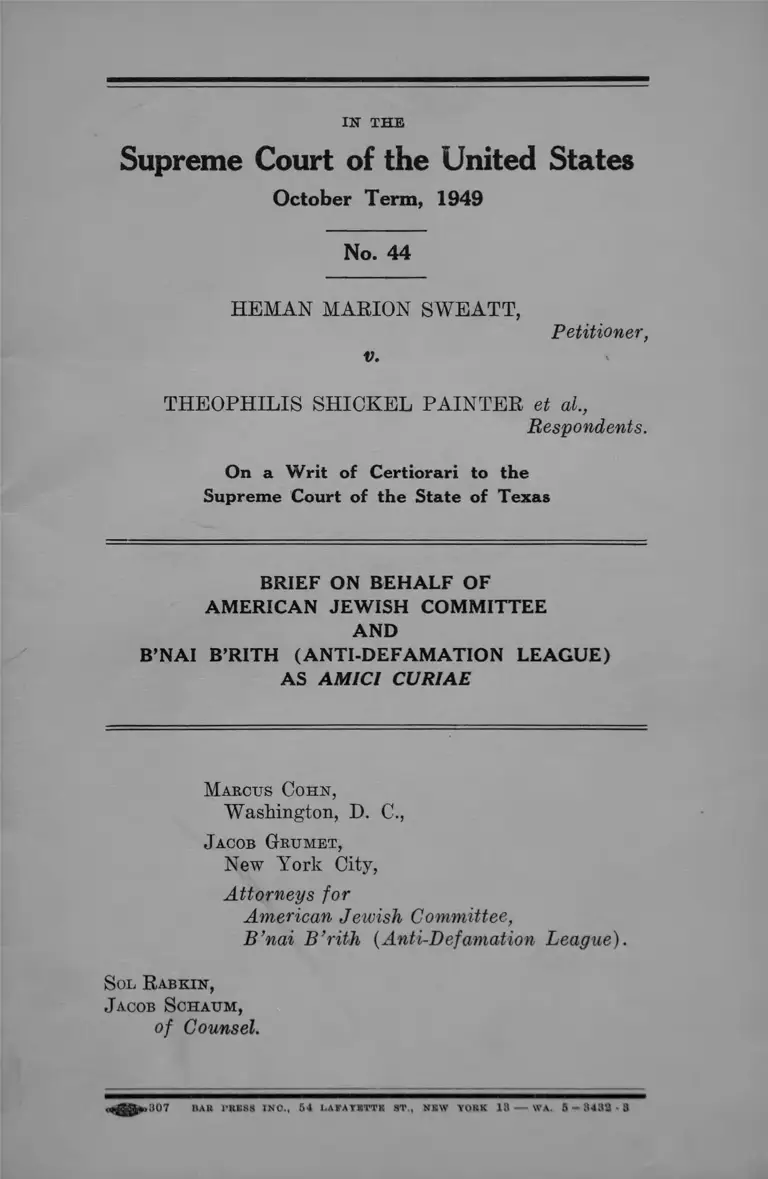

IN' THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949

No. 44

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

v.

Petitioner,

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER et at.,

Respondents.

On a Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of the State of Texas

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF

AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE

AND

B’ NAI B’RITH (ANTI-DEFAM ATION LEAGUE)

AS AMICI CURIAE

Makcus Cohn,

Washington, D. C.,

J acob G-bum et ,

New York City,

Attorneys for

American Jewish Committee,

B ’nai B ’ritJi (Anti-Defamation League).

Sol Rabkin,

Jacob Schatjm,

of Counsel.

BAR l 'RRSS INO., 5 4 LA FA Y E T T E ST. , N E W YOR K 1 3 ----- WA. 5 - 8 4 3 2 - 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I nterest op the A m ici ........................................................... 1

Opinions B elow ......................................................................... 3

J urisdiction .................................................................................. 3

S tatement of F acts ................................................................ 3

Sum m ary of A rgument ............. 5

P oint I. The validity of racial segregation in pub

lic educational facilities has never before been

decided by this Court ............................................. 8

P oint II. Racial segregation in public educational

institutions is an arbitrary and inadmissible

classification under the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment ............................. 12

P oint III. The “ separate but equal” doctrine origi

nated by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson had

no basis in then-existing legal precedent, and is

an anachronism in the light of present-day legal

and sociological knowledge..................................... 17

P oint IV. Segregation necessarily imports discrim

ination and therefore violates the requirements

of the Fourteenth Amendment .............................. 28

(1) Equality is in fact impossible in racially

segregated public educational facilities........ 29

(2) The economic, sociological and psychological

consequences of racial segregation in and of

themselves constitute a discrimination pro

hibited by the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment ................................. 35

Conclusion .................................................................................. 39

A ppendix ...................................................................................... 40

PAGE

11 Index

Table of Cases

PAGE

Acheson v. Murakami, 176 F. (2d) 953 ...................... 17

Atchison, Topeka etc. By. v. Mathews, 174 U. S. 96 ... 21

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45 .................... 9

Bryant v. Zimmermann, 278 U. S. 63 .......................... 25

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ..........................14, 24, 26

Butler v. Perry, Sheriff of Columbia County, Fla.,

240 U. S. 328 ............................................................ 24

Chesapeake & Ohio By. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S. 388. .. 21

Chesapeake, 0. & S. By. Co. v. Wells, 85 Tenn. 613. .. 19

Chicago & N. W. By. Co. v. Williams, 55 111. 185...... 19

Chiles v. Chesapeake & O. By. Co., 218 U. S. 71...... 22

Civil Eights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ................................... 18

Clyatt v. U. S., 197 U. S. 207 ....................................... 22

Colgate v. Harvey, 296 U. S. 404 ................................. 25

Camming v. County Board of Education, 175 U. S.

528 ............................................................................. 9

Day v. Owens, 5 Mich. 520 ............................................. 19

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147 ..................................... 11

Gong Lum v. Bice, 275 U. S. 7 8 ..........................2, 10, 11, 25

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 IT. S. 485 ....................................... 8,9,18

Heard v. Georgia By. Co., 1 I. C. C. B. 428.............. 20

Heard v. Georgia By. Co., 3 I. C. C. B. I l l .............. 20

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 ......................................... 14

Hirahayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81 ............................. 13,16

Houck v. Southern Pac. By. Co., 38 Fed. Bep. 226.... 19

Korematsu v. U. S., 323 U. S. 214 13,16

Index i l l

Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61. .. 12

Logwood etc. v. Memphis etc. Ry. Co., 23 Fed.

Rep. 483 ....................................................................19,20

Louisville, New Orleans, and Texas Ry. Co. v. Mis

sissippi, 133 U. S. 587 ........................................... 18

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151.....11, 23

McGuinn v. Forbes, 37 Fed. Rep. 639 ..........................19, 20

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337. ..10,11, 25

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ................................. 14

PAGE

Ohio ex rel. Clarke v. Deckenbach, 274 U. S. 392 ....... 13

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 ............................. 13, 29

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U. S. 583 ..................................... 21

Patsone v. Penna., 232 U. S. 138................................... 13

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418 ..................................... 20

Perez v. Sharp, 32 Calif. (2d) 711 ............................. 21

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ...... 6, 7, 9,11,18, 20, 21,

22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 37

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1................................... 15, 35

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, 332 U. S. 631 ................................................ 11

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 ................................. 14

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 .................. 14

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410 ........................................................................... 14

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ................. 17

The Roanoke, 189 U. S. 185............................................. 22

The Sue, 22 Fed. Rep. 483 .........................................19, 20

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 ................................. 13

IV Index

J?AGE

West Chester etc. Ry. v. Miles, 55 Penn. St. 209 ...... 19

Westminster School District v. Mendez, 161 F. (2d)

774 ............................................................................ 2

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 .............................. 14

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 U. S. 356.................... 14

United States Constitution

Fourteenth Amendment 5, 6, 7, 8,11,12,15,18,19, 21, 22, 23,

24, 25, 29, 35, 37

Interstate Commerce Clause ................................. 18, 21, 22

Thirteenth Amendment .................................................22, 24

Federal Statutes

Interstate Commerce Act, Sec. 3 ................................. 20

Federal Civil Rights Act ............................................. 18

State Constitutions and Statutes

Constitution of Texas. Art. VII, Sec. 7 28

Oklahoma "Separate-coach statute” 23

Texas R v:- 1 Civil Statutes. Title 49. Chap. 19. Art.

2900 28

Other Authorities

Bore. nuraee I t a nr . r ".or. of the Negro in (lie

American Social Order (1934) 34,37

Boysm. Lean ueu . . Stores and 1'rouds ol Ihf

-mthds Between White and Negro Teacher*•

Salaries in S:e Sourer” States, t900

Index v

Caliver, Ambrose, Availability of Education to Ne

groes in Eural Communities, Office of Ed., Dept.

PAGE

of Interior, Bulletin No. 12 (1935) ........................ 32

Davis, A. and Dollard, I., Children of Bondag*e (1940) 37

Embree, Edwin R., Brown America (1931) .............. 33

Gallagher, B. G., American Caste and the Negro Col

lege (1938) ..........................................................37,38

Johnson, Chas. S., The Negro in American Civiliza

tion (1930) ................................................................ 33

Long, Some Psychogenic Hazards of Segregated

Education of Negroes, 4 J. of Negro Ed. 336

(1935) 38

Long, The Intelligence of Colored Elementary Pupils

in Washington, D. C., 3 J. of Negro Ed. 205-22

(1934) ........................................................................ 38

46 Mich. L. Rev. 639 (1948) ........................................... 9

Moton, Robert R., What the Negro Thinks (1929) 33,37

Newbold, N. C., Common Schools for Negroes in the

South, The Annals of the Amer. Acad, of Polit.

& Soc. Science, Vol. 140, No. 229 (Nov. 1928) 32

Phelps — Stokes Fund, Educational Adaptations:

Report of Ten Years’ Work, 1910 1920 33

Report of a Survey of the Public Schools of (lie l)is

trict of Columbia Conducted Under I,bo Auspices

of the Chairmen of the Subeoounifleos on Ills

trict of Columbia Appropriations Conmiiltoos

of the Senate and House of Ifepn; eufnlives,

U. H, Gov’t Printing ()1T, Washington, D

(1949) .......... , 87

V I Index

Report of the President’s Commission on Higher

Education, Higher Education for American De

mocracy: Vol. II, Equalizing and Expanding In

PAGE

dividual Opportunity (1947) .............................. 33

Segregation in Public Schools—A Violation of

“ Equal Protection of the Laws” , 56 Yale L. J.

1059 (1947) .............................................................. 38

Survey of Higher Education for Negroes, H. S. Office

of Ed., Misc. No. 6, Vol. II, U. S. Gov’t Print.

Off., Wash. D. C. (1942) ..................................... 33

The Availability of Education in the Texas Negro

Separate School, 16 J. of Negro Ed. 429 (1947) 33

Thompson, Chas. H., Court Action the Only Reason

able Alternative to Remedy the Immediate Abuse

of the Negro Separate School, 4 J. of Negro Ed.

419 (1935) ................................................................ 31

Thompson. Chas. H., The Critical Situation in Negro

Higher and Professional Education, 15 J. of

Negro Ed. 579 (1946) ............................................. 32

Waite. Edward F.. The Negro in the Supreme Court,

30 Minn. L. Rev. 219 (1946) ................................. 21

Woofter. Thomas J. Jr.. The Basis of Racial Adjust

ment (1925) .................. _ .... ................................. 33

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949

No. 44

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

v.

Petitioner,

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER et al.,

Respondents.

On a Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of the State of Texas

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF

AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE

AND

B’NAI B’RITH (ANTI-DEFAM ATION LEAGUE)

AS AMICI CURIAE

Interest of the Amici *

This brief is filed, with the consent of both parties, on

behalf of the American Jewish Committee, and the Anti-

Defamation League of B ’nai B ’rith.

* The Appendix contains a description of the organizations

appearing as amici curiae.

2

Both of these organizations are dedicated to the preser

vation of democratic rights guaranteed all citizens by onr

Federal Constitution. Each has long since recognized that

the invasion of the rights of any individual or group on

the basis of race undermines the foundation of rights

guaranteed to all groups in our democracy.

The present case causes us deep concern because the

pattern of discrimination in segregated educational facili

ties has deprived millions of Americans of equality of op

portunity and has perpetuated an abhorrent caste system.

In the light of sociological and psychological insights

gained from experience with segregated school systems it is

clear that compulsory segregation results in physical,

social, intellectual and economic inequality for the Negro

and any other segregated group. These inequalities give

rise to and strengthen the effect of inequalities in other

areas of human activity, for such inequalities compound

each other.

Beyond this, we are concerned with the fact that segre

gation has become an effective threat to the very founda

tion of onr democratic way of life. If a State can require

segregation in education for Negroes, it can also require

it for Chinese, see G :h*j Lam v. Bice, 275 IT. 8. 78, for

Mexitans. see BAsmAtst-'r School District v. Me mice, 161

F. id 774. or for any arbitrarily selected group. 8ogre

cation tnauttains the racist doctrine that undesirable social

traits and. inferior mental capacities inhere not in the

individual, hut in the group. This concept must be excised

"ram the fabric of onr society. Certainly « first step is to

remove it from onr law.

® siawfti b% stntod finally that ttl ar© fully aware that

by wntt nf and ft©

sepjiTAir 1 equal duel vine is the fear that a dostrae-

tion ©f barriers ©f segregation will give rise I© iat-

oreasad racial lenniom* We believe that the ugly preju-

dictiK which create such tensions batten on segrscation

3

A decision by this Court eliminating racial segregation

in education will strengthen the democratic relationships

among the various groups in our population. This issue

must be faced honestly and boldly.

Opinions Below

The judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of

Texas refusing the application for writ of error to the

Court of Civil Appeals for the Third District, dated Sep

tember 29, 1948, without opinion, appears on page 466 of

the record. The order, dated October 27, 1948, overruling

the motion for a rehearing, without opinion, appears on

page 471 of the record. The opinion of the Court of Civil

Appeals, dated February 25, 1948, appears at page 445 of

the record, and that of the District Court of Travis

County, dated June 17, 1947, is reported at page 438.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is invoked under Title 28, United Stntea

Code, section 1257 (3).

Statement of J'act*

The petHjwjer ;o ihh w w , iiemm MttrUfh > vwenti,

jui gjit adumaou to A# Bdho&l ot Law *A the University

of Texas. He eme&d&My met all (A the mmlenha quali

fications, but the authorities o f the TTniversity denied him

enrollment because he is a Negro.

In the State of Texas in accordance with statutory

and constitutional provisions the maintenance of separate

schools for whites and Negroes is compulsory. The

4

University of Texas Law School which Sweatt sought to

enter is maintained for white students only.

On May 16,1946, Sweatt brought an action in mandamus

in the District Court of Travis County, Texas, to compel

the members of the Board of Regents of the University

of Texas, and others, to admit him as a student. That

court, after a hearing, entered an order finding that

Sweatt was denied the equal protection of the laws since

no provision had been made by the State of Texas for

his legal training.

The District Court did not, however, grant the writ

of mandamus but rather adjourned further consideration

of the action until December 17, 1946, giving the respond

ents six months time within which to produce a course of

legal instruction substantially equivalent to that provided

for white students at the University of Texas.

At the second hearing on the application for the writ,

which took place December 17, 1946, the State of Texas

attempted to show the availability of a law school for

Sweatt by presenting to the court a copy of a resolution

adopted November 27, 1946, by the Board of Directors of

Texas A. & M. College to the effect that if Negro appli

cants for law school training were to present proper evi

dence of the required academic qualifications they would

be admitted to a law school for Negroes to be established

in Houston. Texas ter me semester beginning February

194,. There was no evicen.ce produced, however, to show

mat a .aw school for N egrres rad actuary been established.

On me rasis of mis representation at the December

1 m rearing me court erterec a final order denying me

petition.

Tims —icguient was set aside without opinion, bv tie

qaum i t i t m Appeals* aim me cause was remanded tor

f irm e r pm atedm is without prejudice t\> the right of any

party.

5

Meanwhile, the State authorities established a separate

Negro law school in premises rented in an office building in

Austin, Texas, for a period to begin sometime in the latter

part of February or early March 1947, and to end on

August 31, 1947. A description of the facilities provided

for this law school is given in Point IV of the argument,

infra.

In May 1947, by amendment and supplementation of

the original pleadings, the petitioner and respondents

joined issue on the question whether the establishment of

this separate Negro law school during the period of pro

ceedings on the appeal was sufficient compliance with the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and,

therefore, whether the refusal to admit Sweatt to the

School of Law of the University of Texas was arbitrary

and in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The trial on this issue was held before the district

court sitting without a jury. Judgment was rendered for

respondents. This was affirmed on appeal to the Civil

Court of Appeals. Writ of error was refused by the

Supreme Court of the State of Texas.

Summary of Argument

The following arguments will be urged in this brief:

I. This Court has never before decided on the consti

tutional validity of racial segregation in public education.

The Court has, in did inn, signified its approval of the

“ separate but equal” doctrine as applied to education,

but has never ruled specifically whether racial segrega

tion in education is within (lie “ equal protection of the

laws” provision of the Fourteenth Amendment.

6

II. Racial segregation in public educational institu

tions is an arbitrary and inadmissible classification under

the “ equal protection” clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

This Court has ruled that legislative classification

based on race alone is a denial of equal protection except

where the national safety is imperilled or there is a

pressing public necessity. Racial segregation in public

educational facilities is clearly not accompanied by any

“ pressing public necessity” and must, therefore, fall un

der the ban of the Fourteenth Amendment.

III. The “ separate but equal doctrine” originated by

this Court in Plessg v, Ferguson had no basis in then-

existing legal precedent and is an anachronism in the

xga: of present-day legal and sociological knowledge.

The eases cited by the majority of this Court to sup

port its decision in tie ease of Plessg v. Ferguson set no

precedent on the questions under consideration in the

-ase v . e m t :- .: - - Vee sine cited the ■■separate

Snrtt Jw h u ft o f the PJcssy ease it has never since

:ecu. r-fMfxumred and affirmed by this Court, Xeither is

the racial classification embodied in the statute under

consideration justifiable as an exorcise of police poweT.

IV. Racial segregation in public education results in

inequality and is a form of discrimination.

This Court has recently stricken down many forms of

discrimination in such fields as housing, ownership of

land, eligibility for employment and in jury duty. The

Court has particularly opposed discriminatory practices

“ rooted deeply in racial, economic and social antago

nisms.”

The “ separate but equal” doctrine urged here stresses

that separation is not discrimination where physically

7

equal facilities are provided, but the ‘ ‘ separate but equal ’ ’

doctrine is a fiction which must be pierced. Segregation

results in social, intellectual, physical and economic in

equality and hence is discriminatory.

Social inequality is an inevitable concomitant of seg

regation. The premise of Plessy v. Ferguson that segre

gation does “ not necessarily imply the inferiority of either

race to the other” is invalid.

Intellectual inequality results where students in one

racial group are separated from others so that they can

not share in intellectual discussion in law classes, in law

review work, in moot courts and the like.

The physical equality supposedly guaranteed by the

“ separate but equal” doctrine does not exist in fact. The

physical facilities afforded white students in Texas are

far superior to those provided for Xegroes, and the Uni

versity of Texas Law School for white students is incom

parably superior to the law school provided for Xegroes.

Xor can physical equality in dual school systems be

achieved in the future.

Economic inequality also inheres in racial segregation

in education. The legal profession is peculiarly one in

which social relationships lead to economic opportunities

which shape a lawyer’s career. Xegroes denied the full

est possible social relationships are deprived of economic

rights.

Therefore, this Court is asked to overrule its decision

in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson and to hold that racial

segregation in public education is violative of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

8

POINT I

The validity of racial segregation in public edu

cational facilities has never before been decided by

this Court.

This Court is here asked to determine the validity of

constitutional and statutory provisions of the State of

Texas which require racial segregation in public educa

tional facilities. Despite the transcendent importance of

the question, this Court has not yet ruled directly on the

constitutionality of segregation in public education. It

has decided similar problems, such as the validity of

racial segregation in transportation and in housing. It

has decided matters relating to educational segregation

where the validity of segregation was assumed but not in

question. But this Court has never before ruled flatly and

specifically on the validity under the Fourteenth Amend

ment of racial segregation in education.

Following the adoption in 1868 of the Fourteenth

Amendment, the earliest case in which some reference was

made by this Court to racial segregation in education was

Hall v. DeCuir. 95 F. S. 185, which involved the validity

of a Soaoe staoute prohibiting segregation by race in public

carriers. That staooioe was declared unconstitutional as an

improper rsguia.-l-:r. of foreign and interstate commerce,

b a m—TnriiiHg, Mr. Jsstk« Clifford reviewed

wMt m m d f l e cndhsm s o f a number o f State eases

' : o a a ir iieu£ ore - of racial socrocnoicoo

■a edbrndlMmi « d adbM k dictum that segi e ration in the

jufffip schools did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment

of ptysacaliT equal school facilities for Negroes were pre

served.

9

In 1896 this Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S.

537, which sustained the constitutionality of a Louisiana

statute which required public carriers to furnish separate

but equal coach accommodations for whites and Negroes.

The Court cited with approval several ancient State cases

which had held that a State could require the segregation

of racial groups in its educational system provided that

facilities for all groups were physically equal.*

The constitutionality of “ separate but equal” facilities

in education was concededly not before the Court in either

the Sail or the Plessy cases. Yet, although there was no

basis for a discussion of equal facilities in education, and

in spite of the fact that the statements of the Court were

dicta, the Plessy case was subsequently employed by State

and lower federal courts to proclaim the legality of segre

gation in educational institutions. See cases cited in 46

mich. l. rev. 639, 643 (1948).

Three years later, this Court decided Cumming v.

County Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528. There, an in

junction was sought to restrain the board of education from

maintaining a high school for white children where none

was maintained for Negro children. The State court had

upheld the board of education, saying that its allocation of

funds did not involve bad faith or abuse of discretion. In

upholding the decision of the State court, Mr. Justice

Harlan stated expressly that racial segregation in the

school system of the State was not in issue.

The next case before this Court which involved com

pulsory educational segregation was Perea College v. Ken

tucky, 211 U. S. 45, wherein the validity of a State statute

which prohibited domestic corporations from teaching

white and Negro pupils in the same private educational in

stitution was attacked. While the scope of the statute was

* See our fuller discussion of the Plessy case, Point Ml, infra.

10

broad enough to include individuals as well as corporations,

this Court said, at 54,

—it is unnecessary for us to consider anything more

than the question of its validity as applied to corpora

tions. * * * Even if it were conceded that its assertion

of power over individuals cannot be sustained, still it

must be upheld so far as it restrains corporations.

This Court supported the reasoning of the State court

that the statute could be upheld as coming within the power

of a State over one of its own corporate creatures. The

statute was considered not to have embodied a deprivation

of property rights. The rights of individuals were not

considered.

Not until 1927 did racial segregation in educational in

stitutions again become the subject of controversy before

this Court. In Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 IT. S. 78 a Chinese

contested the right of the State of Mississippi to exclude

her from the high school for whites, and to assign her to

the colored school under the State’s segregated school

system. The State contended that under its constitutional

provision requiring that separate schools he maintained

fo r d f l b e t o f l i e l U e and colored races, the plaintiff

jocLi not insist :u heang i.oe.sed with the whites and that

the legisiitnr-e was not compelled to provide separate

srhoojs for each of the colored races.

The issue of segregation was not presented in this case.

The plaintiff accepted the system of segregation in the

public schools of the State, but contested her classification

within that system. Since she did not contest the practice

of segregating Negroes from whites, segregation was not

in question.

Nor was the validity of segregation before the Court

in the case of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337 in which the petitioner was refused admission to the

University of Missouri Law School, a State supported in

stitution, solely because be was a Negro. The State, having

11

no law school, for Negroes, sought to fulfill its obligation to

provide equal educational facilities by paying the peti

tioner ’s tuition for a legal education in another State. This

the Court held did not satisfy the constitutional require

ment. It said that the petitioner was entitled to be ad

mitted to the University of Missouri Law School in the

absence of other and proper provision for his legal train

ing within the State of Missouri.

Again, the issue was not segregation, but whether an

otherwise qualified Negro applicant for law training could

be excluded from the only State supported law school.

This Court assumed that the validity of equal facilities in

racially separate schools was settled by earlier decisions

and cited the Plessy case and McCabe v. Atchison, T. &

S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151, both of which involved segre

gation only in public carriers, and the Gong Lum case.

But the validity of a state requirement of segregation was

not decided.

The most recent consideration of this problem was in

1948 in the University of Oklahoma Law School case,

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma.

332 U. S. 631. This Court, in a per curiam decision, said

that the State must provide law school facilities for the

Negro petitioner “ in conformity with the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and provide it as soon

as it does for applicants of any other group” (at 633).

The facts in the Sipuel case were similar to those in the

Gaines case, in that no law school facilities were afforded

Negroes by the State of Oklahoma.

Segregation was not at issue in (lie Sipuel case. This

Court stated in Fisher v. Hurst, 333 IT. S. 147, 150, that:

The petition for certiorari in Sipuel v. University of

Oklahoma did not present the issue whether a state

might not satisfy the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment by establishing a separate law

school for Negroes. On submission, we were clear it

was not an issue here.

12

In no case previously before this Court in which racial

separation in education has been the subject of comment

in an opinion has there been a record presented upon which

the Court felt compelled to take cognizance of the issue of

segregation per se in State supported educational insti

tutions.

The record in this case presents the issue squarely:

Does segregation in State supported educational in

stitutions meet the requirements of the “ equal protection”

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment!

POINT II

Racial segregation in public educational institu

tions is an arbitrary and inadmissible classification

under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

In determining whether a particular legislative classi

fication meets the requirements of the “ equal protection”

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, this Court has

applied two tests: first, whether the classification statute

has a constitutionally permissible objective, and, second,

whether the classification scheme is based upon differences

between the groups classified which bear a substantial

relation to an objective of the legislation.

B efore this Court would invalidate legislative elassi-

CkbAmb it has Ir a ■eeeosary to show a lack of any pos-

aHe jprraiuls for hSrf is the ability of the statute to

«Ht»s desired rad fegitnafte ends. This rule was applied

nr L,mr,.£.{•? t. Xatural Ca-rbomf Cfas Co., 220 IT. 8L SI,

7A in the following terms:

one who assails the classification * * * must,

carry the burden of showing that it does not rest

upon any reasonable basis, but is essentially arbi

trary.

13

Moreover, the presumption of constitntionality and the

rational basis test which have been applied to classifica

tion statutes have been decisive to the degree that the

Court has refused to invalidate such statutes unless there

was a clear showing that the legislature was “ manifestly

wrong” in its action. See Ohio ex rel. Clarice v. Dechen-

bach, 274 U. S. 392, 397; Patsone v. Penna., 232 U. S. 138,

144.

While these tests have always been, and are operative

as to other legislative classifications, the history of the

Court’s rulings involving the constitutional validity of

governmental action based upon racial distinctions reveals

that as to cases concerned with racial discrimination and

other civil rights and liberties, the above presumptions

are generally not applied. Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S.

516.

The propriety of classification on the basis of race has

been the subject of separate and special vigilance. The

Court has increasingly in recent years made searching

inquiry into the sufficiency of any grounds asserted as

justification for governmental distinctions based on race

or color. It has stated that “ all legislative restrictions

which curtail the civil rights of a single race group are

immediately suspect.” Korematsu v. U. 8., 323 L . S. 214,

216. “ Only the most exceptional circumstances can ex

cuse discrimination on that basis in the face of the equal

protection clause.” Oyama v. California. 332 l . S. 633.

646. This Court has recognized that, as a general rale,

Distinctions between citizens solely because of

their ancestry are by their very nature odious to a

free people whose institutions are founded upon the

doctrine of equality. For that reason legislative

classification or discrimination based on race alone

has often been held to be a denial of equal protec

tion. Ilirabayashi v. IJ. 8., 320 IT, 8, 81, 100.

14

In the application of these principles, the Court has

consistently declared governmental classification based on

race or color to he constitutionally invalid.

This Court has struck down governmental action of a

discriminatory character relating to the exclusion of

Negroes from grand and petit juries. Strauder v. West

Virginia. 100 U. S. 303; Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400; it

has ruled that the right to qualify as a voter, even in

primaries, may not he subject to racial classification.

**I* too clear for extended argument,” said this Court,

"tea* color cannot be made the basis of a statutory classi

fication affecting the right set up in this case” Nixon v.

Herndon. 273 I . S. 536, 541. In a more recent decision,

this Court has held that the exclusion of Negroes from

voting in a primary election by a political party consti

tuted a denial by the State of the right to vote. Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U. S. 649. This Court has also struck down

laws which in their administration have been revealed as

a racial classification resulting in the denial to persons

of a particular race or color the right to carry on a busi

ness or calling, Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356; Yu

Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 U. S. 500; Takahashi v. Fish

and Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410.

This Court has protected the right to acquire, use and

dispose of real property from infringement by State action

effecting race classification. In Buchanan v. Warley, 245

IT. S. 60, which involved a racial residential zoning ordi

nance, the State invoked its authority to pass laws in the

exercise of its police power, and urged that this compul

sory separation of the races in habitation be sustained

because it would “ promote the public peace by prevent

ing race conflicts” (at 81). This Court rejected that con

tention, saying:

The authority of the state to pass laws in the

exercise of the police power * * * is very broad * * *

[and] the exercise of this power is not to be inter

fered with by the courts where it is within the scope

15

of legislative authority and the means adopted rea

sonably tend to accomplish a lawful purpose. But it

is equally well established that the police power * * *

cannot justify the passage of a law or ordinance

which runs counter to the limitations of the Federal

Constitution * * *. (at 74).

The Court rejected the consideration of the police power

of the State, however legitimate the exercise of it, to jus

tify a racial classification where rights created or pro

tected by the Constitution were involved.

In a more recent case, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1,

this Court, by unanimous decision, held that the enforce

ment of racial restrictive covenants by State courts is

State action, prohibited by the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. In the course of its decision,

the Court measurably strengthened the equal protection

clause as a formidable barrier to restrictions having the

effect of racial segregation. The contention was there

pressed that since the State courts stand ready to enforce

racial covenants excluding white persons from occupancy

or ownership, enforcement of covenants excluding Ne

groes is not a denial of equal protection. This Court

rejected the equality of application argument, decisively

dismissing it in the following language:

This contention does not bear scrutiny. * * * The

rights created by the first section of the Fourteenth

Amendment are, by its terms, guaranteed to the in

dividual. The rights established are personal rights.

It is, therefore, no answer to these petitioners to say

that the courts may also be induced to deny while

persons rights of ownership and occupancy on grounds

of race or color. Equal protection of the laws is not,

achieved through indiscriminate imposition of in

equalities, (at 21, 22).

16

There has been but one recent deviation from this

trend in civil rights cases. This Court has stated that

“ in the crisis of war and of threatened invasion” when

the national safety is imperilled, it will permit a racial

classification by the Federal government. In Hirabayashi

v. U. S., swpra, which involved a prosecution for failure

to obey a curfew order directed against citizens of Jap

anese ancestry, and in Korematsu v. U. S., supra, where a

governmental order directing the exclusion of all persons

of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast military area

was contested, the Court recognized an overriding pressing

public urgency in time of war. In doing so it made clear,

however, that this was an extraordinary exception. “ Leg

islative classification or discrimination based on race alone

has often been held to he a denial of equal protection.

* * * We may assume” , continued the Court, “ that these

considerations would be controlling here were it not for

the fact that the danger of espionage and sabotage, in

time of war and of threatened invasion” has made neces

sary this racial classification, which “ is not to he con

demned merely because in other and in most circum

stances racial distinctions are irrelevant.” Hirabayashi

v. U. S., supra, at 100, 101.

State laws providing for racial segregation in public

educational facilities are clearly not accompanied by any

“ pressing public necessity” . Rather, there is a pressing

public necessity to give all American citizens their due

equality of opportunity to utilize educational facilities

established by the state for its inhabitants. The denial of

such equality of opportunity serves only to create public

unrest and disillusionment on the part of those denied in

the strength and honesty of our democratic system of

government. It serves also to weaken our efforts to pre

serve peace and extend democracy abroad by exposing our

government’s earnest efforts in this direction to a charge

of hypocrisy.

17

It is argued by those who seek to justify racial segre

gation that this Court’s declaration against the constitu

tionality of State statutes requiring racial segregation

would serve to touch off an explosion in some parts of our

country. But among those who raise this bogey are many

who do so for ulterior reasons, seeking to protect special

privileges which they have seized as members of the

favored racial group. Further, where segregation has been

voluntarily abandoned in State-provided higher education

as in Arkansas and Kentucky, the dire results predicted

have failed to come to pass. And even if disorder does re

sult, such disorder cannot justify the failure of the State

to protect the constitutional rights of all of its citizens.

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U. S. 1.

It is noteworthy that since the termination of the war

our federal courts have gone out of their way to condemn

the action of the Army in ousting persons of Japanese

ancestry from the West Coast military area solely on the

basis of their national origin. Acheson v. Murakami, 176 F.

(2d) 953.

POINT III

The “separate but equal” doctrine originated by

this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson had no basis in then-

existing legal precedent, and is an anachronism in the

light of present-day legal and sociological knowledge.

Apart from the wartime “ national peril” decisions,

which are clearly inapplicable here, only one unfavorable

precedent exists. This is Plessy v. Ferguson, which

enunciated the ‘ ‘ separate but equal ’ ’ doctrine in 1896. This

doctrine maintains that facilities can be constitutionally

separate, or segregated, provided there is physical equality.

We have already pointed out that the Plessy case, in

volving railroad transportation, does not apply to questions

of public education. But, assuming arguendo that Plessy

18

could apply, we submit that the Plessy case originally had

no basis in legal precedent, and moreover is an anachronism

in the light of present-day legal and sociological knowledge.

The more recent decisions of this Court affecting racial

classification have effectively undermined its authority.

In consequence, the Plessy case is no longer good law, and

is not controlling on the question of the constitutional

validity of racial segregation.

Plessy v. Ferguson held that a Louisiana “ separate-

coach*'statute requiring “ equal accommodations for white

and Negro passengers” did not violate the command of

the Fourteenth Amendment that no State shall deny to

any person the equal protection of the laws, because of

race or color.

In the Zhtsst? decision, three cases were cited as

authority for the constitutionality of statutes requiring

separation of the two races in “ schools, theatres, and rail

way carriers.” None were in point. Hall v. DeCuir, 95

U. S. 485, was concerned solely with the question of

whether a State statute prohibiting segregation was in

violation of the Interstate Commerce Clause of the Fed

eral Constitution, and did not deal with the interpretation

of the Fourteenth Amendment or its safeguards. The

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, invalidated the Federal

Civil Rights Act of March 1, 1875 on the sole basis that

Congress had no authority to pass legislation under the

Fourteenth Amendment, which was directed against dis

crimination by private persons rather than by State action.

Finally, Louisville, New Orleans, and Texas Ry. Co. v.

Mississippi, 133 U. S. 587, was another case concerned

solely with the effect of the Interstate Commerce Clause

on State legislation. It held that a State segregation stat

ute in terms applicable only to intrastate transportation

did not unduly burden interstate commerce.

The majority in the Plessy case (p. 548) claimed that

“ statutes for the separation of the two races upon public

19

conveyances” were held to be constitutional in twelve

named cases. An examination of these cases does not

support the Court’s statement.

The first two cases cited by the Court, West Chester etc.

Ry. v. Miles, 55 Penn St. 209, and Day v. Owens, 5 Mich. 520,

were pre-Civil War decisions, and hence could have set

no precedent on the question. The West Chester case was a

Pennsylvania common law action, which turned upon the

reasonableness of segregation under a regulation of the

carrier. The majority rested its conclusion on “ the law

of races, established by the Creator Himself.”

Chicago & N. W. Ry. Co. v. Williams, 55 111. 185, and

Chesapeake, 0. & 8. Ry. Co. v. Wells, 85 Tenn. 613,

although decided after the Fourteenth Amendment was

passed, do not contain any discussion of the impact of

that Amendment on the question. The Illinois court in the

first case merely termed the discrimination unlawful, and

awarded damages. In the Chesapeake case, the Tennessee

court, in a one-paragraph opinion, held that the Kailway

had acted reasonably under a State statute, and dismissed

the complaint. Similarly, in Houck v. Southern Pac. Ry.

Co., 38 Fed. Rep. 226, the court discussed the facts,

and summarily awarded damages without even considering

the Fourteenth Amendment.

In The 8m , 22 Fed. Rep. 483, Logwood etc. v. Mem

phis etc. Ry. Co., 23 Fed. Rep. 483, and McOuinn v. Forbes,

37 Fed. Rep. 639, there were involved only discussions of

common law principles and private regulations; not of

State statutes. The Sue was an action in Admiralty,

involving transportation facilities employed in public navi

gable waters between points in Maryland and Virginia.

The court held that only the federal government could

legislate in this field, but since it had failed to do so, the

owners of the boat could adopt such reasonable regulations

2 0

as the common law allowed. One of the restrictions im

posed by the common law was that “ accommodations equal

in comfort and safety must be afforded to all alike who

pay the same price.” Therefore the court’s holding that

the accommodations offered to the plaintiff, a Negro pas

senger, were unequal, and its award of damages, was based

on an interpretation of common law, not of a State statute.

Logwood etc. v. Memphis etc. Ry. Co., involved intra

state railway transportation. The court simply charged

the jury to adopt the rule of The Sue as proper law. Mc-

Guinn v. Forbes was another action in Admiralty involving

a steamer travelling between Maryland and Yirginia. The

holding in the case was that the plaintiff’s proof was in

sufficient to entitle him to a verdict. Again, The Sue was

cited, and no constitutional issue was raised.

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 418, involved a conviction un

der the New York Penal Code provision forbidding dis

crimination at amusement parks. The provision was sus

tained against constitutional objection as a valid exercise

of the police power, in light of “ the War Amendments.”

Thus this case in no way supports the proposition for which

it was cited by the majority. It is interesting to note that

Justice Peckham, one of the majority in the Plessy case,

was on the New York Bench at this time, and dissented

without opinion in the King case.

The last two cases cited as authority in the Plessy

majority opinion were Interstate Commerce Commission

decisions, and involved the same facts and parties. Heard v.

Georgia Ry. Co., 1 ICCR 428, was a holding that Section 3

of the Interstate Commerce Act had been violated by the

discriminatory practices of the defendant. No State statute,

and hence no constitutional discussion was involved. Heard

v. Georgia Ry. Co., 3 ICCR 111, merely reenforced the

21

prior holding. See, Edward F. Waite, The Negro in the

Supreme Court, 30 Minn. Law Review 219, 248-251 (March,

1946).

Additional lines of cases cited by the majority in the

Plessy case involved the existence of “ separate schools for

white and colored children, which has been held to be a

valid exercise of the legislative power * * * ” (p. 544), and

“ Laws forbidding the intermarriage of the two races’ ’

(p. 545). There is serious doubt of the validity of laws

forbidding the intermarriage of races. The only Supreme

Court decision on the subject was Pace v. Alabama, 106

U. S. 583, which is readily distinguishable as involving an

indictment for the crime of “ adultery or fornication’ ’ be

tween persons of different races; where the statute con

taining this provision had a lesser punishment for the same

crime between persons of the same race. The most recent

decision on this subject was a very carefully reasoned one

by the highest court of the State of California, which in

validated an anti-miscegenation law as in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment, Perez v. Sharp, 32 Calif. (2d)

711.

Although many cases have cited the “ separate but

equal” doctrine of the Plessy case, it has never since been

reexamined and affirmed by the Court.

The first time the Supreme Court cited the “ Plessy

doctrine” was in Atchison, Topeka etc. Ry. v. Mathews, 174

U. S. 96, 105. The holding therein was that the Plessy de

cision did not forbid the imposition of “ unequal burdens”

on specified corporations; and that the State legislature

could validly allow the plaintiff in a suit against the rail

roads for damages caused by fire, to obtain attorney’s fees.

Racial discrimination or segregation statutes were not

involved in the case.

In Chesapeake <& Ohio Ry. v. Kentucky, 179 IT. S. 388,

392, the Court was concerned solely with the application of

the Interstate Commerce clause. A Kentucky “ separate-

2 2

coach statute” was construed to apply solely to passengers

both embarking and departing from depots within the State;

the Court then saying, ‘ ‘ and so construing it, there can be

no doubt as to its constitutionality. Plessy v. Ferguson.”

Similarly, the Roanoke, 189 U. S. 185, 198, dealt primarily

with the Interstate Commerce issue. Therein it was held

that Congress, and not the states, could legislate regarding

certain navigable waterways. The Court distinguished

Plessy as involving State law “ requiring separate car

riages for the white and colored races [which] were sus

tained upon the ground that they applied only between

places in the same state. ’ ’ Hence, neither of these decisions

in any way validated that part of the majority decision in

the Plessy case which purported to interpret the Four

teenth Amendment.

Clyatt v. U. S., 197 U. S. 207, 218, cited the Plessy case

solely to uphold Congressional legislation punishing “ the

arrest of any person in the Territory of New Mexico to

a condition of involuntary servitude ’ ’ against attack on

the grounds that it fell outside the scope of the Thirteenth

Amendment. The Court quoted the statement that “ this

[the Thirteenth] Amendment was said in the Slaughter

House Cases to have been primarily intended to abolish

slavery * * * but that it equally forbade Mexican peonage

or the Chinese coolie trade when they amounted to slavery

or involuntary servitude, and that the use of the word

‘ servitude’ was intended to prohibit the use of all forms

of involuntary slavery, of whatever class or name. ’ ’ It was

not at all concerned with the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Court in Chiles v. Chesapeake & 0. By. Co., 218

U. S. 71, 77, emphasized the fact that it was dealing with

“ the act of a private person, to wit, the Bailway Co. # * *

and we must keep in mind that we are not dealing with

the law of a state.” The Court thus escaped facing the

issue of the Interstate Commerce Clause, as well as the

23

issue of the Fourteenth Amendment as applied to rail

roads. On page 77 it quoted from the Plessy language

the phrase “ the established usages, customs and tradi

tions of the people” solely as a “ test of reasonableness

of the regulations of a carrier.”

McCabe v. Atchison, T. <& 8. F. By. Co., 235 U. S. 151,

160, involved the constitutionality of a clause in the Okla

homa “ separate-coach statute” which provided that “ the

provision requiring equal accommodations (earlier in the

statute) should not be construed to prevent railway com

panies from hauling sleeping cars, dining or chair cars

attached to their trains to be used exclusively by either

white or negro passengers, separately or jointly.” The

defense maintained that the Oklahoma legislature could

take note of the fact that the number of Negroes requir

ing such service did not justify the use of separate facili

ties in such cars.

The actual holding in the McCabe case was that the

petitioner failed to show sufficient standing to obtain in

junctive relief. However, in addition, the Court rejected

the defense argument, saying that it “ makes the consti

tutional right depend upon the number of persons who

may be discriminated against, whereas the essence of the

constitutional right is that it is a personal one.” By way

of further dictum, on page 160, the Court noted that

“ there was no reason to doubt” the lower court’s finding

that “ it has been decided by this court, so that the ques

tion could no longer be considered an open one, that it

was not an infraction of the Fourteenth Amendment for

a state to require separate, but equal, accommodations

for the two races. Plessy v. Ferguson.” This dictum

was not only unnecessary for the decision in the case,

but was irrelevant to the constitutional issue, in that

by finding a lack of equality, the Court held that the

“ separate but equal” doctrine spelled out by the majority

in the Plessy case was inapplicable. Hence there was no

need for the Court to re-examine it.

24

Butler v. Perry, Sheriff of Columbia County, Fla., 240

U. S. 328, 333, was another case which cited the Plessy

case in connection with the Thirteenth Amendment. The

issne involved was the constitutionality of a Florida stat

ute providing that all able bodied men residing in Colum

bia County would be subject to call to work on the public

roads in the county. On page 333 the Court quoted the

Plessy decision to show that the Thirteenth Amendment

was designed “ to cover those forms of compulsory labor

akin to African slavery, * * * and certainly was not in

tended to interdict enforcement of those duties which in

dividuals owe to the state.”

The case of Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 79,

supra, which cites the Plessy opinion, is indicative of the

tendency of judicial sentiment to depart from the “ sep

arate but equal” doctrine. In that case, the plaintiff, a

white landowner, contracted to sell a plot of land to the

defendant, a Negro. The defendant refused to pay on the

grounds that a city ordinance of Louisville, which pro

hibited colored persons from occupying houses in a block

where the greater number of houses were occupied by

whites, made performance of the contract impossible.

In holding that this ordinance was in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment, the Court distinguished the Plessy

case on the ground that in that case a “ classification of

accommodations was permitted upon the basis of equality

for both races.” However, the Court did not state that

there was inequality in the case before it, but chose to

rest its decision on broader grounds. On page 81 the

Court said “ But in view of the rights secured by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution, such legis

lation [as upheld in the Plessy case] must have its limi

tation, and cannot be sustained where the exercise of

authority exceeds the restraints of the Constitution. We

think these limitations are exceeded in laws and ordi

nances of the character now before us.” And again, on

25

page 76, that "the chief inducement to the passage of the

[Fourteenth] Amendment was the desire to extend federal

protection to the recently emancipated race from un

friendly and discriminating legislation by the States.”

In Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78, 86, this Court held

that a child of Chinese blood, horn in, and a citizen of, the

United States, is not denied the equal protection of the

laws by being classed by a State among the colored races

who are assigned to public schools separate from those

provided for the whites, when equal facilities for educa

tion are afforded to both classes. The Court was concerned

primarily with the problem of construing the Plessy doc

trine to cover the facts of the case. It relied upon the

authority of the old State decisions cited in the Plessy

case.

Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63, 70, involved a

proceeding in habeas corpus in a State court where the

detention on a criminal charge was alleged to be in vio

lation of the United States Constitution. This Court cited

the Plessy case as a holding that such a proceeding is a

"su it” within the meaning of the jurisdictional statute,

and that an order of the State court of last resort, refus

ing to discharge the prisoner, is a final judgment in that

action, and is, therefore, subject to review. That case, of

course, was in no way related to the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

Similarly, in Colgate v. Harvey, 296 U. S. 404, 446, the

dissenting opinion cited the Plessy case only to show the

reluctance of the Supreme Court to extend the coverage of

the "privileges and immunities” clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

In Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337,

344, the Court, although talking the language of the Gong

Lum and Plessy cases, found that there was "unequal”

2 6

legal instruction afforded in Missouri, and hence did not

find it necessary to re-examine the old decisions.

Thus it appears that this Court has never directly

affirmed or re-examined the decision in Plessy v. Fer

guson, and that to overrule it now would not result in the

overthrow of a well-established line of legal precedents.

Justification for the legislative classification in the

Plessy case was that it was a valid exercise of the police

power of the State, and that it was not discriminatory

because it applied equally to both races. As to the exer

cise of police power, the Court said, at 544,

Laws permitting, and even requiring, their sepa

ration in places where they are likely to be brought

into contact * * * have been generally, if not uni

versally. recognized as within the competency of the

state legislatures in the exercise of their police

power.

This Court has since refused to recognize the police

rower State as a justification for racial legislation.

Brndhsmesr, u. W srk-'i. supra, is a complete answer (p. 74):

The police power, broad as it is, cannot justify

the passage of a law or ordinance which runs counter

to the limitations of the Federal Constitution.

The principal ground of decision in the Plessy case,

that there is no discrimination where the separate facilities

furnished to both races are on an equal basis, is open to

attack on several counts.

In the first place, the Plessy case assumed that segre

gated facilities can he equal. As we have shown, the

Court has since the Plessy case rejected the claim that

there is any presumption of constitutionality attaching

to such a statute. Rather, it has said that racial classifi

cation laws must be viewed with great suspicion and bear

27

the closest scrutiny. They must overcome the strong

inference of unconstitutionality. The Court would not

today accept the factual assumption of the Plessy case

without a showing that it rests upon a reasonable basis.

Second, the fact of discriminatory application of “ se

parate but equal” in the field of education is a knowledge

so common and universal, that the Court cannot but dis

miss as unfounded the assumption of Plessy, and take

judicial notice that racial segregation in education, wher

ever applied, is administered with an unequal hand and

is unequal in result.

In Washington, D. C., our national capital, these facts

have been demonstrated recently by a survey of the segre

gated school system in effect there. The survey was con

ducted pursuant to a request by Congress by a “ person

qualified by training and experience in the field of public-

school education” (62 Stat. 542). Professor George D.

Strayer of Columbia University was assisted by a staff

of 22 specialists in his study. The findings of the survey

are embodied in a report submitted to Congress, Report

of a Survey of the Public Schools of the District of

Columbia Conducted Under the Auspices of the Chairmen

of the Subcommittees on District of Columbia Appropria

tions of the Respective Appropriations Committees of

the Senate and House of Representatives. Washington,

Government Printing Office, 1949. The facts contained

in this report demonstrate beyond doubt the inequality of

the white and colored public school systems of the District

of Colombia. If efforts to achieve a “ separate but

equal” -segregated school system have failed in our

nation's capital where it h subject to the control of our

national Congress, car, it possibly succeed in those areas

where a system of caste and race privilege is deeply

intrenched ?

Third, the expenditure by a State of its educational

funds for racially segregated schooling will necessarily

result in inferior quality and quantity of schooling for

28

both races, than if the same funds are spent for unsegre

gated education. “ Separate but equal” in education

results in an inferiority of facilities for both races.

Legislative classification in educational facilities on the

basis of race or color must therefore fall, as constitu

tionally invalid, as an arbitrary and inadmissible classifi

cation under the “ equal protection” clause. The racial

distinction is “ irrelevant and therefore prohibited.” It

is based upon factors which reflect concepts of racial

superiority and inferiority and is thus rendered irrational

as a justification under the Constitution. The decision of

the major case supporting it was erroneous when originally

decided, and has since been implicitly repudiated numerous

times by this Court. A final and open repudiation is in

order.

POINT IV

Segregation necessarily imports discrimination

and therefore violates the requirements of the Four

teenth Amendment.

The State of Texas, by constitutional provision .Art.

YU. See. 71 and statutory enactment (Eevised Civil Stat

utes. Title 49. Chap. 19. Art. 2900) stipulates that separate

schools be provided for white and colored students, "and

impartial provision shall he made for both races. ’ ’

The contention is raised that, since the State law in

sures physical equality of treatment within a segregated

system, no violation of the equal protection of the laws is

involved. Where a specific instance of inequality is proven,

the remedy should be merely to “ equalize” ,—either by

improving the educational facilities for Negroes, or by

worsening those for whites to the level provided for

Negroes.

This reasoning does not have even a superficial appear

ance of validity. Inherent therein are the erroneous as

29

sumptions that the State may, by virtue of its police power,

establish racial classifications, and that there are differ

ences between the two races which warrant making such

classification. These contentions are dealt with elsewhere

in this brief.

What we are concerned with here is the false assump

tion that, in the segregation of the races in educational

facilities, there can be attained the equality of treatment

which the Fourteenth Amendment requires. It is our con

tention that educational facilities for Negroes in segregated

areas have never been equal and could not possibly achieve

an equality which would satisfy the dictate of the “ equal

protection” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633, 636, Chief Justice

Vinson made it clear that this Court may take cognizance

of actual conditions and deal with realities. He said:

In approaching cases, such as this one, in which

federal constitutional rights are asserted, it is incum

bent on us to inquire not merely whether those rights

have been denied in express terms, but also whether

they have been denied in substance and effect. We

must review independently both the legal issues and

those factual matters with which they are co-mingled.

(1 ) Equality is in fact impossible in racially segregated

public educational facilities.

WTterever racial segregation in education lias been re

quired by the State, the physical educational facilities al

forded Negroes have been substantially and uniformly

inferior and unequal to those enjoyed by whites.

The di>.par:ty hi physical facilities ban been so great

and so universally a concomitant of the Mg >• yated *f*tw

that it need b&rdfy he preened here by extern we dee®-

mentation.

30

Expert testimony in the record shows that the State

of Texas regnlarly spends substantially less for Negro

than for white education. The total assets of white insti

tutions of higher learning amount to $28.66 for each white

person in the State, but the assets of Negro schools amount

to only $6.40 per Negro. The whites have almost four and

one-half times as much in total educational institutional

assets per capita of the population as do the Negroes

{K. 241).

In 1943-44. a typical year, Texas appropriated approxi

mately Sll.X'i.AC in State, county and district funds for

higher edtaeathm. Of this amount, about $10,800,000 went

to white institutions, or 81.98 per capita of white popula

tions ; the balance went to Negro institutions, or the equiva

lent of ih. per capita of Negro population in the State.

On this basis, white institutions of higher learning received

eight times as much as Negro institutions (E. 246).

The inequality in physical facilities is even far more

pervasive than the statistics on appropriations for edu

cation by the State indicate. The testimony in the trial

court showed that the State of Texas provided a law school

for the petitioner by leasing a suite of three rooms and

toilet facilities in an office building, after the commence

ment of the action, for a period beginning March 1,

1947. and ending August 31st of that same year (B. 29,

41b in the semi-basement of the building (B, 88). One

room was to be an office and reading room and the other

two were intended as classrooms. There was no private

office or faculty room for any instructor, for administra

tive personnel or for a dean (E. 47). Nor was there space

for a library consistent with even the minimum needs of a

law school. Some 200 text hooks were available on the

premises to serve as a library (E. 21). There was no

librarian (E. 96).

There was no provision for scholarships, prizes, par

ticipation in the production for the Texas Law Eeview,

participation in the legal aid clinic, or opportunity to join

31

any honorary law society, such as the Order of the

Coif, all of which were features of the School of Law of

the University of Texas and consequently available only

to white students (R. 103-105).

The faculty of the “ school” offered to the petitioner

consisted of three instructors assigned part-time from the

University of Texas Law School (R. 92-93). Admittedly,

the school established for the petitioner did not meet the

requirements set by the Association of the American Law

Schools for accreditation (R. 92).

The State of Texas contends that this racially segre

gated law school affords facilities equal to those enjoyed

by white students at the University of Texas Law School.

But it is quite obvious that the Negro law school cannot

possibly afford even a minimal legal education. To claim

that it is “ equal” to the University of Texas Law School

is sheer hypocrisy.

The treatment afforded Mr. Sweatt by the State of

Texas is by no means a unique example of the treatment

accorded Negroes in educational institutions of the South

under the guise of equality of segregated facilities. In

every instance of segregation in practice there are pro

vided for Negro citizens fewer educational opportunities,

and educational opportunities of poorer quality than

are afforded to white citizens. The deficiencies are syste-

matie and all-pervading.

This is not confined to the level of higher education,

nor to the State of Texas. The pattern is (he same when

ever racially segregated schools exist.

In the generation from 1900 to 1930 the disparity be

tween the provision of public educational facilities t>r

white and Negro children, where separate schools an-,

legally mandatory, has increased at a tremendous ram

“ In 1900, the disparity in the per capita expenditures

upon the two racial groups was only 60 per cent in fa-

of whites, but in 1930 this disparity had increased to f V

per cent.” (Thompson, Chas. H., Court Action t/V 0*1 v

32

Reasonable Alternative to Remedy the Immediate Abuses

of the Negro Separate School, 4 J. of Negro Ed. 419

(1935) ).

For the ten year period, 1918-1928, $270,500,000 was

spent on new school facilities by eight Southern states

(including Texas) for white children, and $29,500,000 for

Negro children. This is a ratio of 9 to 1 in favor of whites

on appropriations, against a population ratio of 2 to 1

in favor of whites. (Newbold, N. C., Common Schools

for Negroes in the South, The Annals of the Amer. Acad,

of Polit. & Soc. Science, Yol. 140, No. 229, P. 209, 218

219 (Nov. 1928) ).

Throughout the South there is a wide discrepancy in

per capita expenditure for Negro teachers as compared

to that for white. For Texas, in 1936, for every $1. spent

for teachers' salaries for white students, only 61 r was ex

pended for salaries tor Negro students. This

ratio was the same as the average for the 17 southern

states. By 1945. white teachers" salaries were in excess

of Negro by 45*1. (Boykin, Leander L., The Status and

Trends of Differentiate Between White and Negro Teach

ers' Salaries in the Southern States, 1900-1946. IS J. of

Negro Ed. 40 (1949)).

There is also a marked inferiority in library facilities

in Negro schools. (Thompson, Chas H„ The Critical Situ

ation in Negro Higher and Professional Education. 15 J.

of Negro Ed. 579, 581, 582 (1946) ).

As to length ot school term, the Negro is attain dis

advantaged, and especially so in the rural communities of

(lie South. In a survey made for the United States Office

ol Kducation in 193d, it was revealed that “ the average

number of days schools are kept open for Negroes in 17

Hoiitliorn states is 135, which is approximately l 1! months

less than (In' accepted standard in those states. The

cumulative eflect ol (bis annual loss to Negroes over one

hcIiooI general ion of 12 years means a difference of 18

mmilliH or ‘.1 school years.” (Caliver, Ambrose, Avail

33

ability of Education to Negroes in Rural Communities, 34,

Office of Education, Dept, of Interior, Bulletin No. 12

(1935)).

In comparison with the physical facilities available to

white students, the segregated Negro student suffers from

an inadequacy and inequality resulting from the segrega

tion in every category of educational facility, and by every

standard of measurement. See, Phelps-Stokes Fund, Edu

cational Adaptations: Report of Ten Years’ Work, 1910-

1920; Johnson, Chas. S., The Negro in American Civilisa

tion (1930) 261 et seq.; Embree, Edwin R., Brown America

(1931); Moton, Robert R., What the Negro Thinks, 102-108

(1929); Survey of Higher Education for Negroes, 14 et

seq., IT. S. Office of Ed., Misc. No. 6, Vol. II, U. S. Gov’t

Print. Off., Wash. D. C. (1942); Woofter, Thomas J. Jr.,

The Basis of Racial Adjustment, 176-185 (1925); The

Availability of Education in the Texas Negro Separate

School, 16 J. of Negro Ed. 429 (1947).

The President’s Commission on Higher Education,

after thorough examination of the facts, found that:

* * * the separate and equal principle has no

where been fully honored. Educational facilities for

Negroes in segregated areas are inferior to those

provided for whites. Whether one considers enroll

ment. over-all costs per student, teachers’ salaries,

ttaBsporteiior facilities, availability of secondary

or oppo.'-t v'.Ptes for undergraduate and grade

i S '-".'.;

fte m h ̂ aad mb'- ■ tM Uf the Negro citizen.

" v r te r Arm-rvgm h>'mocmi,y ■ Vof 11,

EfEsv-arnsr *rnv v; eg Opportunity

31 0 * 0 ) . .

It might be contended that while educational teeili

ties have been and are, in fact, unequal, equality *« ouvi-.i

theless theoretically possible. There are two ftuewet*i

u

Edneatiowt: plants, like other physical facilities, de

teriorate at varying rates. To maintain physical equality

in a segregated Mkcational system, it would be necessary

to f f̂fitimaaLy taJsmee the facilities of one system against

the ether and to take steps to eliminate inequalities which

necessarily develop from time to time. This is adminis

tratively impossible.

But there is even a more compelling factor which

makes physical equality of facilities, without a substantial

reduction of facilities now available to whites, a practical

impossibility. The financial cost involved is beyond the

capacity of the South to bear. Horace Mann Bond, in

Education of the Negro in the American Social Order

(1934) sums this up, at 231:

If the South had an entirely homogeneous popu

lation, it would not be able to maintain schools of high

quality for the children unless its states and local

communities resorted to heavy, almost crushing rates

of taxation. The situation is further complicated by

the fact that a dual system is maintained. Consider

ing the expenditures made for Negro schools, it is

clear that the plaint frequently made that this dual

system is a burden is hardly true; but it is also clear

that if an honest attempt were made to maintain

‘ equal, though separate schools’, the burden would be

impossible even beyond the limitation of existing

poverty.

Physical equality can be achieved only when the walls

separating the two systems are destroyed and students

regardless of race or color, are permitted to use all avail

able educational facilities.

35

(2 ) The economic, sociological and psychological conse

quences of racial segregation in and of themselves

constitute a discrimination prohibited by the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Aside from consideration of equality of physical facil

ities. segregation. involves substantial factors -which

duc-e a degree of inequality repugnant to the Cv-nsMEi

Theme are discriminatory factors -which are preeinr

in the very sekeoEag: afforded the Xegro, which have no