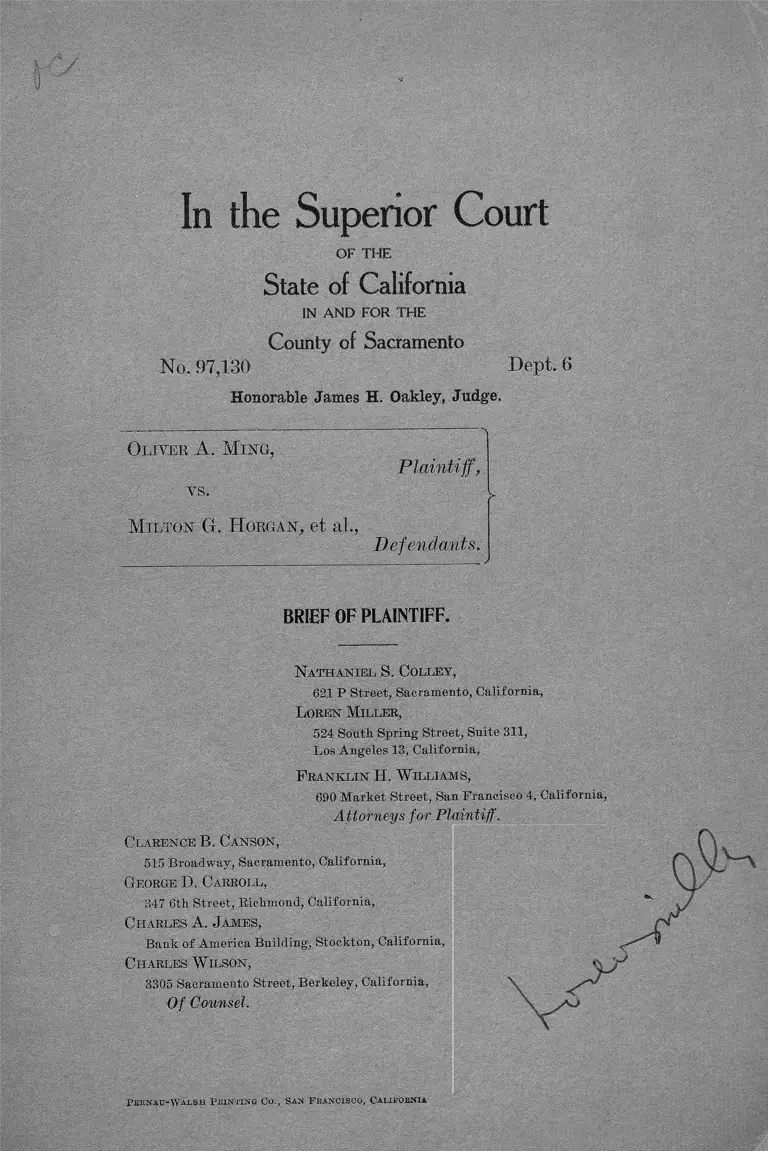

Ming v. Horgan Brief of Plaintiff

Public Court Documents

March 20, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ming v. Horgan Brief of Plaintiff, 1957. 34e1fad5-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/26825cf7-199e-4e20-9796-22aa29ffc3a3/ming-v-horgan-brief-of-plaintiff. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the Superior Court

OF THE

State of California

IN AND FOR THE

County of Sacramento

N o . 97,130 Dept. 6

Honorable James H. Oakley, Judge.

O l iv e r A . M i n g ,

Plaintiff,

v s.

M il t o n G . H o r g a n , et a l.,

Defendants.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF.

N athaniel S. Collet,

621P Street, Sacramento, California,

L oren M iller,

524 South. Spring Street, Suite 311,

Los Angeles 13, California,

F ran k lin H. W illiam s,

690 Market Street, San Francisco 4, California,

Attorneys for Plaintiff.

Claren ceB. Canson ,

515 Broadway, Sacramento, California,

George I). Carroll,

347 6th Street, Richmond, California,

C harles A. J ames,

Bank of America Building, Stockton, California,

C harles W ilson,

3305 Sacramento Street, Berkeley, California,

Of Counsel.

Pernatt-'Wa l s h P r in ting Co., San F rancisco , California

Subject Index

Page

The historical background ................................................... .. 1

Statement of fa c t s ......................................................................... 5

The National Housing Act and Federal Housing Administra

tion ............................................................................................... 8

A. Housing and public interest............. ............................... 9

B. The growth of Congressional p o licy ................................ 12

1. The mortgage insurance program ............................ 13

2. The public housing program .................................... 15

3. The Home Loan Bank B oa rd .................................... 16

C. The crystallization of Congressional p o licy ...................... 16

D. Attaining the objectives ................................................... 19

E. The relationship between builder, FHA and V A ........ 22

1. Under Section 203 of the A c t .................................. 22

2. Other sections of the A c t .......................................... 30

(a) Property improvement loan s............................ 30

(b) Section 8—Building ........................................... 31

(c) Section 603—Housing ........................................ 31

(d) Section 611— Construction...................... 31

(e) Section 903— Homes............................................. 32

(f) Section 207—-The project housing................... 33

(g) Section 608—H ousing........................................ 33

(h) Section 610— Special program ........................ 34

(i) Section 908—Liberal terms .............................. 34

( j) Wherry military housing ................................ 34

(k) Section 213— Cooperative housing ................ 35

Summary ............................................................................. 35

F. FHA regulation and con tro l........................................... 36

G. The Congressional intent ................................................. 45

Operative builders may not practice racial discrimination.. . . 49

11 Subject Index

Page

77The conspiracy .............................. ................................... ..

Defendants’ conduct contravenes National and State public

policy ......................................................... 83

Plaintiff as a third party beneficiary.......................................... 88

The conspiracy in restraint of sa le .............................................. 90

This is a proper class action .......... ............................................... 92

Defendants are forbidden to discriminate in the ease of a

q o

de facto town .............................................................................

Federal statutes protect plaintiff’s right to purchase the

housing in question .................................................................... 98

To what relief is plaintiff entitled? ............................................. 101

Conclusion .......................................................................................

In the Superior Court

OF THE

State of California

IN AND FOR THE

County of Sacramento

No. 97,130 Dept. 6

Honorable James H. Oakley, Judge.

O l iv e r A. M in g ,

v s.

M il t o n G . H o r g a n , e t a l.,

Plaintiff,

Defendants.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF.

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND.

This is another in that long series of judicial con

tests involving the claim of Negroes that they have

the constitutional right to purchase and occupy real

property, particularly urban land, on a basis of com

plete equality with all other Americans. Such litiga

tion is almost a half century old. In every instance

Negroes have faced bitter, sometimes hysterical, op

position but although relief has sometimes been de

layed the claimed right has been vindicated in every

instance by the Courts.

2

The issue is even older than the litigation. Congress

sought to secure the right beyond the possibility of

impairment in 1866—prior to the adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment— when it enacted what is now

Section 1982, 42 USCA, which provides that:

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right in every state and territory, as is en

joyed by white citizens thereof to inherit, pur

chase, lease, sell, hold and convey real and per

sonal property.” (Emphasis added.)

It is ironic that this same right should be in dispute

ninety years later.

Litigation involving purchase and occupancy of

urban property by Negroes has been many faceted. As

early as 1908 cities attempted to curtail Negro owner

ship, and consequent occupancy, of real property by

racial zoning ordinances1 which were ultimately con

demned in Buchancm v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917).

Undaunted, proponents of residential segregation

turned to increased use of racial restrictive covenants

and for almost a quarter of a century—from 1915 to

1948—courts enforced them by equitable decrees.2 The

Supreme Court finally interdicted judicial enforce

ment in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948). Ad

vocates of racial covenants then sought indirect en-

iSan Francisco anticipated these ordinances with an ordinance

segregating Chinese which was invalidated in 1890. In re Lee

Sing, 43 Fed. 359.

2The first such case was Queensborough Land Co. v. Cazeaux,

139 La. (1914). California followed suit in 1919, L. A. Invest

ment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680. For complete history of covenant

litigation, see 33 Cal. Law Review 5.

3

forceinent through damage actions by signers against

covenantors who had sold to Negroes but the Supreme

Court made short shift of that effort by forbidding

judicial cognizance of such suits:3 Barrows v. Jack-

son, 346 U.S. 249 (1953).

Meanwhile, in the early 1930’s the federal govern

ment began augmenting the supply of housing, di

rectly to low income families through open subsidies

to local authorities for construction of low rent public

housing, and indirectly to middle income families

through the mortgage loan insurance system of the

National Housing Act of 1934 administered through

an arm of government, Federal Housing Administra

tion. Racial segregation, imposed by local housing

authorities with the consent of the federal government

was initially approved in Favors v. Randall, 40 Fed.

Supp. 734 (1941) and ultimately forbidden in Banks

v. San Francisco Housing Authority, et al., 120 Cal.

App. 2d 1 (1953); Cert. Denied: 347 H.S. 974 (1954).

Federal Housing Administration (F H A ), as we shall

show, has had a checkered career in this field, first

requiring the imposition of racial covenants as a con

dition of mortgage loan insurance, then relaxing that

rule and finally taking a non-discriminatory position.4

Always the rationalization for restraints on the

right of Negroes to purchase and occupy urban land

has been the same: the claim that such ownership or

3This ease originated in California, 112 CA2d 534.

4For history of FH A’s shifting positions see: The Negro Ghetto,

Robert Weaver, ITarcourt-Brace, 1948, particularly Chapter V,

and Forbidden Neighbors, Charles Abrams, Harper & Bros., 1955,

particularly Chapter XVI.

4

occupancy, in the words of the National Association

of Real Estate Boards, would “ clearly he detrimental

to property values.” 5 6 In every instance those who

sought to curtail ownership and occupancy of urban

land on the basis o f race have availed themselves of

the “ full panoply of state power” ,8 protesting at every

step of long drawn out litigation that the discrimina

tion they sought to vindicate was either compatible

with constitutional guarantees or that it was permis

sible within that area of individual action immunized

against constitutional interdiction by the Fourteenth

Amendment as interpreted in early cases.7 The task

of the courts has been that of stripping away the form

and laying bare the substance of the constitional evil

inherent in excluding the Negro from the free hous

ing market.

The case at bar must be put in that historical con

text. Seen in that perspective, it is readily apparent

that this Court will seldom be called upon to render

a decision fraught with greater legal significance than

the one it will pronounce here.

5NAREB, Cannon of Ethics, prior to 1950. See Abrams, op. cit.,

150 et seq.

6Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, uses this phrase.

7This theme runs through all housing cases: beginning with

Buchanan v. Worley, 1917, and ending with Banks v. San Fran

cisco, 1953. It will be asserted with vigor by defendants in this

case.

5

STATEMENT OP FACTS.

At trial of this action the Court indicated that it

had the facts well in mind, and suggested to counsel

for the respective parties that in their briefs they ad

dress themselves primarily to the law involved. We

atcept the suggestion of the Court, but since on some

major points there is substantial conflict in the evi

dence we feel compelled to make at least passing re

ference to considerations which seem to leave little

doubt that the facts of the case are as plaintiff alleged

them to 'be and as his witnesses testified.

W e must admit at the outset that we were quite

surprised, to put the matter mildly, that practically

every defendant who testified, denied that he had ever

refused to sell a house or lot to a prospective pur

chaser because of race or color, or that he had any

racial policy with regard to sale of houses. No defend

ant came into Court and admitted that he ever refused

to sell certain sub-division housing to Negroes, and

none asserted that he claimed any right to so refuse.

In fact, several defendants admitted on cross-examin

ation that they thought such a refusal would be un

lawful.

When one reads the verified answers filed by these

same defendants, our surprise at their testimony

should become understandable. The answers of each

of the principal defendants in this case “ admit plain

tiff claims the right to lease or rent any home without

reference to his race or color, and that defendants

claim and assert that they have the constitutional

right to refwse to sell, lease or rent property to whom

6

soever they desire not to sell, lease or rent.” While

the parties deny any concert of action, their pleadings

are almost identical in this respect.

In determining where the truth lies with respect to

any policy of defendants in refusing to sell to Ne

groes, the Court need only ask itself this question. Is

it likely that a defendant who has never refused to

sell a home to a ready, willing and able Negro pur

chaser, and who has no policy against such sales,

would file in Court a verified pleading setting up as

a defense to a charge of racial discrimination an asser

tion that he has a constitutional right to practice such

discrimination %

In addition to the admissions set forth hy defend

ants in their answers, we have the positive testimony

of the plaintiff himself and many members of the race

to which he belongs to the effect that defendants do

in fact consistently refuse to sell new sub-division

housing to Negroes. Coupled with this testimony is

the fact that no such housing, with the exception of

in one or two so-called “ open occupancy” sub-divi

sions, has been sold to a Negro. The testimony of

Professor Cy Record indicates that there are many

Negroes in Sacramento County able to buy such hous

ing. Furthermore, defendant Fernandez admitted that

while he had sold no unit in his Freeport Manor to

a Negro, soon after he made the initial sales to white

persons, Negroes purchased homes in that tract on a

re-sale basis from the original purchasers. It is hardly

reasonable to assume that Negroes would refuse to'

aPIJly for original purchase when no down payment

7

was required and terms were liberal, and yet rush in

to make such purchases at a time when they had to

pay premiums for equities of original buyers. At

least the evidence showed nothing which would sustain

an inference that Negroes have a bias against new

houses with low, or no, down payments.

It is also significant that the testimony of witnesses

Horgan and Frye (by way of deposition) admitted

that defendants Heraty and Gannon had a policy of

not selling their sub-division housing to Negroes. Also,

witness Turner, manager of defendant Larchmont

Village, Inc., admitted that he refused to sell a house

to a Colonel Evans, a Negro, because, as he put it,

“ the colored people’s association is suing us.” The

fact that Colonel Evans was not a member of the Asso

ciation (N AACP) made no difference to Mr. Turner.

No matter what the Colonel belonged to or didn’t be

long to, the fact is that he was a Negro, and hence

was a member of a group or class to which Larch

mont Village was not selling homes. While he denied

excluding anyone because of race, witness Frank

MacBride admitted that he felt that he had a moral

obligation to the white people to whom he sold houses

in Arden Oaks Vista to exclude Negroes. And last,

but not least, Real Estate Board member Eugene W il

liams denied ever having discussed the question of

racial policy or exclusion of certain persons from

some neighborhoods with anyone. He said he had

never had that much interest in the problem. Little

did he know that at that very moment we had in our

possession a letter written by him to Real Estate

8

Board member Tom Kiernan, in which Mr. Williams

advised Mr. Kiernan that a member of Kiernan’s

staff had been seen showing a house in a certain com

munity to a member of “ one of the inharmonious

groups” , and he urged Kiernan to help keep that area

“ free from this problem.” It is true that Mr. W il

liams said he did not know why he had written the

letter, nor did he know what he meant by the term

“ inharmonious group” , but the letter speaks for it

self.

For these and other reasons, the findings of fact on

the material issues in this case must be in favor of

plaintiff.

THE NATIONAL HOUSING ACT AND FEDERAL

HOUSING ADMINISTRATION.

There is a common content to the substance of the

arguments that we shall make that can best be dealt

with in a preface. Such treatment will avoid repeti

tion and make for clarity. That common content con

cerns the provisions of the National Housing Act, its

objectives and its provisions, and the administrative

agency, FH A as it is popularly called, through which

the legislative program is effectuated. Without an un

derstanding of the terms of the Act and of the kind,

character and quality of F H A ’s functioning in the

housing market the legal problem that confronts the

Court becomes difficult, almost impossible, of isola

tion and solution.8

8The Housing Act of 1934 was enacted as 48 Stat. 1246. It is

reproduced as amended at 12 United States Code Annotated (12

USCA) Sections 1721 ff.

9

In this preface we shall advert to many different

kinds of housing provided for in the Act and to a

number of FI1A activities and policies in respect to

those varying kinds of housing. However, it must be

borne in mind that the housing constructed by the

builder-defendants here was built for sale under Sec

tion 203 of the Act and is all ultimately designed for

sale to individual purchasers. The builder’s function

in this particular phase of housing consists o f con

structing that housing and of then putting it on the

market.

W e shall have to include historical material for the

light it may shed on present day practices and we

shall have to delve into the Congressional Record for

statements that will illuminate statutory language.

Our inquiry will be a lengthy, sometimes tedious one,

but, we believe, the end result will be that we will have

put the legal problem in its proper frame of refer

ence.

A. Housing and Public Interest.

The public concern with adequate housing for the

American family is reflected in the Declaration of

Rational Housing Policy written into the Housing

Act of 1949 where it is said that “ . . . the general

welfare and security of the Nation requires the reali

zation as soon as feasible of the goal of a decent home

and suitable living environment for every American

family.” (Title I, Bousing Act of 1949, Declaration

of Principles.) None can doubt that by this declara

tion, Congress intended to encompass all Americans

10

without reference to race or color, and by the same

token it is clear that Congress, by reason of the due

process clause of the Fifth Amendment, could not

enact legislation of such scope without making the

benefits open to all on a non-discriminatory basis.

However, all of us know that this goal has been

made difficult, if not impossible of attainment, through

what the Housing and Home Finance Administra

tion once aptly called a “ blockade o f custom and

code.” (Albert Cole, Speech, Detroit, 1954.) The evi

dence in this case well illustrates how that blockade

works and how it has operated to deny Sacramento

Negroes free access to the housing market on terms

of equality with other citizens. Thus our problem

meets us at the very threshold of the discussion. We

will deal with its specific manifestations later.

As we have pointed out, since the early 1930’s the

federal government, through the grant of direct sub

sidies, credits and powers has become increasingly

involved in the planning, marketing and managing of

dwellings. The scope of federal participation is wide.

It ranges from public housing, through slum clear

ance, urban renewal and guarantee of modernization

loans, to mortgage insurance and loan guarantees for

new housing. The means vary and have varied from

time to time; the goal has remained constant. But in

no instance, for policy reasons which need not con

cern us here, has federal assistance been granted di

rectly to individual home seekers. Rather it has been,

and is, made to private lenders, developers and build

ers and to local public agencies.

11

Obviously, Congressional enactments have been in

tended to confer benefits as inducements to private

lenders and developers and public agencies in order

to persuade them to participate in a program or pro

grams that will lead to attainment of the goal of a

decent home for every American family.”

It is ironic that these lenders and developers (and

even local public housing agencies until brought to

book by the courts) early arrogated to themselves the

authority—claimed by defendants in this case to be an

absolute right—of making the decision as to whether

or not non-whites, in our case Negroes, should be

excluded from the beneficences of Congressional leg

islation. They have translated their prejudices and

their fears into a set of exclusionary rules that have

all the force of law, even while operating under a law

that explicitly includes “ every American family” ,

and implicitly enacts the Constitutional command

against inequality of treatment.9 Racial discrimina

tion in Sacramento is now effectuated by quasi-ad-

ministrative action of builders, developers, selling

agents and lending institutions, all under the guise of

bona fide participation in reaching the objective of the

Congressional goals. How and why did Congress ar

rive at the policies it has enacted in our statutes ?

9The Housing Authority of the City of Sacramento, which ad

ministers the public housing program which flows from the Na

tional Housing Act is restrained by force of Banks v. San Fran

cisco, supra, from following the administrative practices of these

“ private” builders. It must bestow its benefits on all applicants

without reference to race. The thrifty Negro home seeker thus

meets racial discrimination that is not visited on his less eco

nomically fortunate fellow citizen.

12

B. The Growth of Congressional Policy.

In 1892, the federal government appropriated

$20,000 for an investigation of slums in cities of more

than 200,000 population. A report of this investiga

tion was made by the Commissioner of Labor and con

tains data on four cities, noting a higher incidence

of lawlessness in shun areas. (Federal Homing Pro

grams Committee Print, 81st Congress, 2nd session,

1950.)

W orld W ar I brought new housing problems and

congressional action resulted in construction of 9,000

houses, 1,100 apartments, 19 dormitories and eight

hotels for shipyard employees, and more than 5,000

single-family dwellings in addition to apartments,

dormitories and hotels for war workers. (Federal

Housing Programs, supra.)

The depression years added to the housing problem

that was accumulating as a result of increased urbani

zation of the nation. It was believed by Congress that

the federal government’s involvement in the provision

of housing was necessary for the economic survival

of the country. As a result, during the period from

1932 to 1934 more than one million homes were saved

through government refinancing, approximately 40,000

units of housing were provided by direct federal ac

tion for low and moderate income families, and more

than eight millions of dollars in loans were made to

corporations formed to provide housing for families

with low incomes. (Federal Housing Programs,

supra.) During this same period, the Federal Home

Loan Bank Board was authorized to make advances,

13

secured by first mortgages, to member borne-financing

institutions. As of June 30, 1949, there were eleven

regional banks providing a credit reservoir for 3,813

member institutions with assets totaling about thirteen

billion dollars. In addition, under the Home Owners

Loan Act $49,300,000 was appropriated to purchase

shares in savings and loan associations which were

members of the Federal Home Loan Bank. (Federal

Housing Programs, supra.)

History, and experience in the early depression

years, finally led Congress to establish three major

permanent federal housing programs—the mortgage

insurance system, public housing and the home loan

bank system, all dedicated to the Congressional objec

tives of that “ decent home for every American

family” .

1. The Mortgage Insurance Program.

The mortgage insurance program was established

in June 1934 for the purpose of insuring long-term

mortgage loans made by private lending institutions

to individual home seekers. The obvious intent was

to make home building attractive to, and possible by,

persons of limited means. Of course, incidental but

nonetheless substantial, benefits were conferred on

lending institutions through the minimization of the

risk entailed in making the loans, In their proper

turn, the builders received a boon because their market

was enormously expanded as home seekers found it

possible to engage in home building, and the mortgage

insurance system guaranteed a flow of credit to

builders.

14

Prom its inception through 1953, FHA, which was

constituted to administer the mortgage insurance pro

gram, has insured more than 33 billions of mortgages,

including insurance on more than three million homes

under the section providing for insurance on the type

of housing involved in this action. It has insured

millions of dollars for rental, cooperative, and pre

fabricated housing under other sections of the Na

tional Housing Act and has provided insurance

against loss on approximately 17,000,000 loans financ

ing home alterations, repairs and improvements.

(Seventh Annual Report, Housing and Home Finance

Agency, 1953, pp. 178-179.)

During World W ar II, mortgages were insured on

962,000 dwellings for war workers and, after the war,

for veterans. In connection with the mortgage insur

ance program, Congress authorized establishment of

a National Mortgage Association to provide a second

ary market for home mortgages, resulting in the later

establishment of the Federal National Mortgage Asso

ciation and the creation of the Federal Savings and

Loan Insurance Corporation to insure up to $5,000,

for any single individual, savings invested in savings

and loan associations. (Federal Housing Program,

supra.) As of June, 1949, the savings of 6,600,000

investors were insured with a total liability of $8,-

868,000,000. (Federal Housing Programs, supra.)

The mortgage insurance system and guarantee of

loans devices were adopted by Congress in 1944, to

aid former servicemen to acquire homes. As of June

30, 1954, 3,638,676 loans had been insured or guar

15

anteed for veterans. (Report, Administrator of Vet

erans Affairs, 1954.)

By any standard, these figures are impressive and

reflect a degree of government involvement in hous

ing that would have been unthinkable when the fed

eral government appropriated the modest sum of

$20,000 in 1892.

2. Tlie Public Housing Program.

The public housing program had its inception in

the National Industrial Recovery Act, providing for

the low income units we have referred to. In 1935,

the Emergency Relief Appropriations Act made an

appropriation of $450,000,000 for housing. In 1937,

the basic statute providing for loans and annual con

tributions to local public agencies for low rent hous

ing and slum clearance projects was enacted. Under

this Act, as amended, from 1937 to June 1955, 490,107

units of public housing have been, provided. (Homing

Statistics, Housing and Home Finance Agency.) Ad

ditionally, during W orld War II, 945,000 public war

housing accommodations were provided under various

statutes. After the war, Congress authorized use of

this war housing for distressed families of service

men, veterans and their families, and construction of

temporary housing from available funds for this pur

pose. Congress also authorized funds for dis-assem-

bling, transporting, re-erecting and converting surplus

war structures on land supplied by educational insti

tutions, State and local bodies, and non-profit organi

zations, for housing for veterans and their families,

16

and distressed families of servicemen. Under this

authorization, as of June 30, 1949, 267,000 temporary

units had been provided. (Housing Statistics, supra.)

These figures, too, bear statistical witness to the

fact that the nation was, and is, edging toward the

goal set by Congress.

3. The Home Loan Bank Board.

The Home Loan Bank Board’s function is to super

vise federal programs of credit, insurance of savings

accounts, and related aids to home-financing institu

tions, particularly savings and loan associations. It

is responsible for operations of the Federal Home

Loan Bank System, Federal Savings and Loan Insur

ance Corporation, and Home Owners’ Loan Corpora

tion. It charters and supervises Federal savings and

loan associations. The Federal Home Loan Bank Sys

tem is the oldest of the permanent federal housing

programs. It includes regional banks in eleven cities,

composed of regional member institutions. These in

stitutions supply approximately a third of all home-

mortgage financing in the country and in 1949 had

approximately $10,000,000,000 in home-mortgage loans

outstanding. In addition to supplying a reliable source

of credit for member institutions, the system encour

ages sound financial and operating practices in the

home-lending field. (Housing Statistics, supra.)

C. The Crystallization of Congressional Policy.

Faced with the serious shortage of housing for vet

erans after World W ar II, which resulted in grossly

inflated prices, Congress enacted the Veterans Emer

17

gency Housing Act of 1946. The Ojffi.ce of Housing

Expediter became statutory creature with power to

establish ceiling prices and rents for new housing,

and to allocate or establish priorities for delivery of

materials or facilities for housing. (Housing Statistics,

supra.) The Reconstruction Finance Corporation was

authorized by this Act to make premium payments

to producers of building materials, and to guarantee

markets for new-type building materials and pre

fabricated houses. The Act also amended and ex

tended the FH A mortgage insurance program for

benefit of veterans and granted them preference in

sales or rentals of new housing. (Housing Statistics,

supra.)

Finally, in 1949, Congress articulated the goals that

had been implicit in its theretofore patch work of

legislation and arrived at a definitive statement of

the housing aims of our national government. (Title I,

Housing Act, 1949, supra.) It said in so many words

what every student of its actions had already deduced,

that its goal was that of a “ decent home and suitable

living environment for every American family” . In

addition to re-enforcing the permanent Federal hous

ing programs that we have been discussing, Congress

authorized a new Federal housing program of loans

and capital grants to local communities for large

scale slum-clearance and urban redevelopment,10 au

10Testimony at the trial showed that Sacramento has availed

itself of these features of the Act and proposes a large scale re

development of a blighted section of the city. Ironically enough,

the working of that plan will expel Negro home owners who must

buy other housing. An official testified that 28% of the families

18

thorizing one billion dollars in loans and a half billion

dollars in capital grants over a five-year period for

this purpose. The Housing Act of 1954 broadened

this program to include rehabilitation of existing

housing in blighted, deteriorated, or deteriorating

areas. (Title III , Section 304, Housing Act of 1954;

68 Rev. Stat. 624, Title 42, TJSCA.) In “ so broaden

ing the provisions of the existing slum clearance and

urban redevelopment law . . . ” Congress, it was made

plain, did not change “ . . . in any way the primary

and principal objective of this law; namely, the im

provement of the housing conditions of American

families. Its primary and principal objective contin

ues to be the elimination of slums and other inade

quate housing and an increase in supply of good

housing.” (Senate Report No. 1472, 83rd Cong. 2nd

Session, U.S. Code, Cong, and Adm. News, 2757-2758.

W e have added the emphasis.)

By the Housing Act of 1955, Congress provided

for additional mortgage insurance, slum clearance

and urban renewal, and public housing. While this

Act was under consideration, Congress was compelled

to increase by $1.5 billion the mortgage authorization

of FHA. In this connection, the Senate committee

considering the housing bill noted that . . the ex

istence of FH A mortgage insurance has made possible

the addition of tens of billions of dollars worth of

adequate housing for United States residents.” (,Sen

ate Report 33, 84th Cong., 1st Session.)

to be relocated are Negro. The Court will recall that some of

these people testified that defendant-builders and brokers refused

to sell tract homes to these dispossessed persons on the basis of

raee.

19

The history we have just recited is abridged. It is

only a partial description of congressional action

taken to effectuate the housing goals envisioned by

Congress. It does not include a discussion of compan

ion executive action. However, it does serve to point

up the profound observation of the late Senator Rob

ert: A. Taft: “ Of course, in Congress we are faced

with the further question of whether the Federal Gov

ernment has any function in this program. Housing,

like food, relief, medicine, is primarily the obligation

of the States and local government. Even if these

programs are the proper function of government, it

is said that under our Constitution they do not fall

primarily within the duties or powers of the federal

government. It is a little late, however, for us to

argue the place of the Federal Government in this pic

t u r e (95, Gong. Rec. A343, 1949; emphasis added.)

D. Attaining the Objectives.

All governments, local, state, or federal, have cer

tain governmental objectives for attainment of which

government is pledged and which they further in

various ways. Some of these objectives are achieved

in. direct and obvious ways. The traditional method

is through individuals denominated officers and agents

of government who are employed to perform various

tasks designed to achieve the agreed-upon govern

mental objective.

On the other hand, there are other governmental

objectives which governments attempt to achieve in

an indirect manner. For policy reasons, it is some

20

times deemed wiser to attain these objectives by

granting substantial government aid to select private

persons or corporations who become chosen instru

ments of government.

In a democratic society, the legislature, as the in

strument of the people, must make the choice be

tween the direct and the indirect methods.

In the matter of housing, accommodations for the

lowest economic group in our population and for mod

erate income families is one of the objectives of our

national government, as we have just demonstrated.

With respect to the lowest income group, the national

government has determined that there is no alterna

tive for the provision of housing for this group except

by direct governmental action and it grants direct

subsidies to reach the end it has found desirable.

However, with respect to those families whose in

comes are too high to qualify for low-rent housing

but who, nevertheless, find it impossible, for economic

reasons over which they have no control, to secure

adequate housing without government intervention,

the national government has determined that there

are alternative methods of providing housing: by

direct action as in the case of low-rent public housing,

or by government insurance of loans made by lending

institutions. Either method will provide housing and

under our Constitutional system either choice is per

missible.

Economic policy considerations dictated the choice

of the latter alternative by Congress. (Senate Report

21

No. 1300. See also 84 Cong. Rec. 412, 1939; 87 Cong.

Rec. 1544, 1941; 90 Cong. Rec. 6661.) But when

World W ar I I created a housing crisis for defense

workers and then for returning servicemen and vet

erans, the national government found it expedient

to relieve the crisis by use of both methods. (90 Cong.

Rec. 6661, 1944.)

It is plain that the FH A mortgage insurance and

the VA loan guarantee programs were thus con

ceived and adopted ~by Congress as methods of pro

viding adequate housing within the financial reach

of moderate income families. It is equally demonstra

ble that the method has been an effective one, in pro

viding homes for the very group for which it was

devised, as shown by the statistics we have heretofore

cited. (78 Cong. Rec. 12013, 1934; 80 Cong. Rec. 4680,

1936; Senate Report 1300 supra; Sen. Rep. 1286, 81st

Cong. 2nd Session, 1950.)

In the case of low rent public housing adminis

tered by governmental officers, there is no question

but that racial discrimination falls under a Constitu

tional ban. (jBanks v. San Francisco, 120 Cal. App.

2d 1; Van v. Toledo, 113 Fed. Supp. 210.) The con

tention of suppliers of housing made possible under

the mortgage insurance system that they have the

“ right” to discriminate rests on the claim, solemnly

asserted and constantly reiterated, that the builder

is a private entrepreneur receiving no benefits from

the National Housing Act, getting no assistance from

FHA, and free of all social and constitutional respon

sibility except that of following his own whim and

22

caprice or bowing to Ms own fears, in the selection

of buyers. He claims the “ right” to make race a cri

terion in choosing who may or may not qualify for

federal mortgage insurance and thus purchase, or

occupy, housing that but for the mortgage insurance

system he would not have for sale. W e will be helped

in deciding the validity of this contention by laying

bare the relationship between builder and PHA.

E. The Relationship Between Builder, FHA and VA.

1. Under Section 203 of the Act.

Although we will discuss various relationships that

necessarily arise in respect of various housing pro

grams which are within the purview of the National

Housing Act and of PHA, it is well to remind our

selves at this point that the housing which is the sub

ject matter of this litigation is that type built for

sale under Section 203 of the Act. In the classic

instance, the individual home seeker who was at

tracted by the information that he could buy a home

through the PH A mortgage insurance program sim

ply had plans drawn up, secured cost estimates, en

tered into a contract with a builder of his choice

and then took the papers to his bank or building

and loan association. In its proper turn the lending

institution submitted the plans and cost estimates to

PH A which reviewed them and indicated approval

or disapproval. Upon approval, the home seeker ar

ranged for the loan, PH A made the commitment for

mortgage insurance and the home seeker executed

the proper mortgage papers. As building progressed,

PH A made detailed inspections and ultimately gave

23

final approval. The builder played a muted part in

the transaction: he was the workman who built the

house and ultimately received payments from the

proceeds of the insured loan. His only contact with

FH A was through the inspectors.

In time, the builder began to assume a more ag

gressive function. FH A had created a market; he

sought to avail himself of its advantages. The builder

himself drew the plans, found the lending institution

and then the home seeker. His acquired skill enabled

him to guide his customer through the paper maze

without difficulty. In reality, he was helping achieve

the objectives of the Act through a laudable profit

motive. He was doing more: he had become an opera

tive builder and was availing himself of the benefits

of the Act,11 and in order to do so he was acting in

concert with the lending institution and with FH A

through its proper officials. Under this arrange

ment, government and the operative builder were

becoming mutually dependent on each other; without

mortgage insurance the operative builder could not

function to attract the home seeker and without the

operative builder government could not pursue its

objective unless it substituted a direct subsidy.

The next step was forecast: the builder planned

a group of homes purely for sales purposes without

having the specific buyers in mind or, indeed, with

out trying to secure them beforehand. I f he could

build houses that he knew would meet FH A specifica

irWe shall use the term “ operative builder” to mean a builder

who constructs homes for sales purposes.

24

tions and hence would be acceptable to the lending

institution because federal mortgage insurance could

be secured he could build for the market instead of

for the individual. Building costs could be minimized.

New problems arose at this juncture because it was

imperative that the builder have absolute assurance

that his product was acceptable to FH A and hence

eligible for mortgage insurance. That problem could

be solved, and was, by getting prior FH A approval

of all plans, including site selection, financing, lender-

mortgagees, purchaser mortgagors and many other

governmental controls and standards. It is readily

apparent that an ever closer relationship would de

velop between builder and FHA. The inter-depend

ence between builder and government became ever

closer as each needed the other more and more to

further his, or its objective. The builder became a

co-partnership, or a corporation with a sales force

and public relations experts to attract the home

seeker. And above all, the builder now built increas

ingly for the market, as he put it, that is for the

class of persons defined as eligible by the National

Housing Act, and eligible for mortgage insurance.

And as the builder built for the class, rather than for

the individual home seeker he began to institute the

exclusionary practices that bottom this law suit—

and that without statutory authority which could

never have been given because the Constitution would

not, and will not, permit it.

The activities of the operative builder that we have

been discussing continued the seeds of their own ex

25

pansion. It was a step from building a small group

of homes to that of developing an entirely new tract

containing hundreds of homes and from that to the

construction of great new cities, like the Levittowns

in the east or Lakewood in Los Angeles county.12

In the matter of the operative builder-defendants

in this case, homes which are built for sale under Sec

tion 203 of the Act were constructed on an extensive

scale. At the time of their construction the PH A

Commissioner was authorized by statute to insure an

amount equal to 95% of the first $9,000 of F H A ’s

appraisal of the value and 75% of the amount in

excess of $9,000; he had to require the mortgagor-

buyer to pay at least 5%' of the Commissioner’s es

timate of cost of acquisition in cash or its equivalent

as a down payment; the builder was required to de

liver to the purchaser a written statement setting

forth the amount of the Commissioner’s appraisal

and a warranty that the house conformed to F H A ’s

approved plans and specifications. The Commissioner

must approve initial charges for the mortgage, ap

praisal and inspection fees. It is also statutory dicta

tion that so long as the mortgage is insured by PHA,

the dwelling may not be sold on credit terms less

favorable to the purchaser than those required by

PH A and the buyer may not levy a race restriction

during the life of the loan. (64 Statutes 68; 68 Stat

utes 591, 607, 642; Title 12 CSC A, Sections 1701,

1709, 1715g.)

12These are complete cities, each containing thousands of dwell

ings built to meet FHA specifications and sold under FHA mort

gage insurance.

26

The Court will recall testimony in this case that

operative builders who were before the Court held

pre-application discussions with FHA. This is the

“ land planning processing” stage and takes the form

of inspection and approval of the site by FH A Land

Planners and Subdivision Valuators. The purpose of

these discussions is to achieve the most desirable land

development plan, the most desirable and practical loca

tion of streets, lot grades, storm water drainage, san

itary sewage lines and the other incidents of sound

community planning. A subdivision report is then

submitted dealing with streets, grading, landscape,

material, lot size and similar items. Following this,

mortgagee-lender (the financial institution that will

finally furnish the mortgage money) files a formal

application for a prior commitment to insure. De

tailed plans and specifications, property descrip

tions, plot, etc., are submitted. In order for any

application to be approved for prior commitment,

land planning, proposed plans and specifications, con

struction and materials to be used must meet F H A ’s

Minimum Property Requirements. At this stage of

the proceedings no individual buyer has been secured.

Potential buyers are members of the class defined as

to eligibility by the Act without reference to race or

color. In essence, the operative builder has now ob

ligated himself to build houses which meet certain

standards set by F H A ; the lending institution has

agreed that as individual buyers are produced it will

lend them the necessary purchase-money funds on

the security of their individual mortgages on indi

vidual parcels of property (the so-called “ take out”

27

mortgages) in the tract, and FIT A has agreed that

it tvitt insure those mortgages if the borrower meets

its eligibility tests. The prime test is that the loan

must be “ economically sound” .

Assuming approval of the project and subsequent

construction, FH A inspectors take over. Their func

tion is to make sure that construction proceeds in

accordance with the contract documents on the basis

of which the commitment was issued. One to four

family dwellings are required to have at least three

inspections. After completion of construction, the

builder is required by statute to certify as to costs.

I f the house is constructed under FH A inspection, the

builder provides the Y A loan guaranty officer with

the required evidence of this fact, in which case Y A

compliance inspection becomes unnecessary. (Title 12

U.S.C. 1715r; VA Technical Bulletin 4A-14.) I f all

enumerated conditions are met, the mortgage insurance

will issue upon F H A ’s approval of the purchaser as to

credit. (Mutual Mortgage Insurance, Administrative

Buies and Regulations under Section 203 of the ATa-

tional Housing Act. Revised 1952 Form 2010, p. 14.)

Both FHA and Y A will now process complaints re

garding faulty construction within one year of convey

ance or initial occupancy. (Title 12 U.S.C. 1701; VA

Technical Bulletin 4A-127.)

It is hard to conjure up a more rigorous statutory

scheme than that devised by the Rational Housing

Act and administered by FHA from its approval to

final approval of the individual mortgagor. That the

builder submits to it is eloquent proof that it prom

28

ises advantages for him. That the Act and FH A

impose it is demonstrative of the fact that it promises

attainment of the goal of a “ decent home for every

American family” . The inter-dependence of govern

ment and builder has reached its zenith. Now it is

plain beyond the need of argument that the com

plementary activities of builder and government have

produced houses for sale to members of the class en

visioned by the Act itself and sought by the builder.

In the face of this rigorous statutory scheme; in

spite of the demonstrated inter-dependence of builder

and government in producing housing for the mass

market and apparently unmindful of the benefits be

stowed on the builder by government, the operative

builder-defendants in this case maintain that they

have complete freedom to decide who may secure

benefits of the mortgage insurance system and thus

buy this government-builder produced housing, and

to discriminate on a racial basis against some mem

bers of the very class for whom they have ostensibly

built.

This Alice-In-Wonderland claim of the right to

impose racial discrimination in the selection of pur

chasers is predicated on the fact that each of the

houses will be sold by the builder in his private

capacity to an individual who will execute an in

dividual mortgage with the house and land as secu

rity to a private lending institution. All that has gone

before—the cooperation between government and

builder in planning the development, the rigorous re

quirements imposed by government as a precondition

29

of the prior commitment without which not a single

house would have been produced, the lending institu

tion’s agreement to make the mortgage loan, condi

tioned as it was on the certain knowledge that it could

minimize its risk through the mortgage insurance

program, the close cooperation between builder and

government conforming the houses to standards set

by government, the conformity of the subdivision to

the overall county or city planning required by gov

ernment, the proviso that FH A must approve the ul

timate buyer, the requirements as to down payments

and interest rates to be assessed against the buyer-

mortgagor-—all these are brushed aside as matters of

no consequence. All that will come after-—the fact that

government credit stands behind the mortgage insur

ance, the requirement against sale on less favorable

credit terms, the pledge of government to process com

plaints of faulty construction for a year after sale

or initial occupancy—all these are relegated into the

unimportant. The blind man has seized the elephant’s

tail and is telling us that the animal resembles a rope.

It is also apparent that the operative builder-de

fendants have lost sight of the objectives of the Na

tional Housing Act. They have charmed themselves

into the pleasant belief that the Act was passed and

FH A was constituted to provide them a market for

their wares, freed of all social and constitutional re

sponsibility, and to minimize the risk of lending in

stitutions who may finance the home construction they

may undertake. They take it for granted that the

power to impose residential segregation—denied by

30

the Constitution to cities, to the courts, and to local

housing authorities—has been lodged with them by

virtue of a statute, the National Housing Act, enacted

pursuant to that same Constitution. Obviously, their

claims cry out for close scrutiny. For if these opera

tive builder-defendants have their way Congress has

but to channel government power into private hands

to rob Constitutional guarantees of all vitality.

2. Other Sections of the Act.

Our discussion of government-builder relationships

has been confined to the relationship that arises under

Section 203 of the Act because the housing involved

in this action was built under that section. Our dis

cussion of relationships that arise under other sec

tions of the Act will be short and is inserted here

simply for the purpose of illustrating the scope and

purpose of the Act, to show how the mortgage insur

ance system dovetails into the high public purpose

of the legislation and to lay bare the manner in which

FH A functions in shaping and directing housing pol

icy within the confines of the legislation under which

it was established.

(a ) Property Im provem ent Loans.

The property improvement provisions of the Act

were enacted in 1934, at least partially as an “ emer

gency” measure but have since come to be highly re

garded as a means of adequate maintenance of the

nation’s housing. Although the loan for improve

ments is insured, no mortgage is required of the

householder. (Property Improvement Loans, FH A

31

document FH-20, Aug. 1, 1950.) FH A says of this

program that “ . . . the building and allied industries,

and the Federal Government combined to assist bor

rowers to make eligible improvements to their prop

erty . .

(b ) Section 8— Building.

In operation since 1950, Section 8 was devised to

provide cheap homes in outlying areas “ where it is

not practicable to obtain conformity with many re

quirements essential to the insurance of housing in

built-up areas.” (12 USCA 1706c(a).) Some 12,000

homes were built under the program but it has not

been widely used.

(c ) Section 603— Housing.

During the period from 1943 through 1948 the bulk

of home mortgages were insured under World War I I

provisions of Section 603 of the Act, enacted in 1941

to stimulate building for war workers and revived

in 1946 as a program for veterans. A total of almost

700,000 homes were insured under Section 603 which

has since expired. Typically, Section 603 homes were

built by operative builders for ultimate sale. Vet

erans’ preferences were enforced.

(d ) Section 611— Construction.

The government’s use of the device of mortgage

insurance to accomplish a myriad of social objectives

is well illustrated by the FH A program under Section

611 which was designed “ to encourage the applica

tion of cost reduction techniques through large scale

32

modernized site construction” . Any project for build

ing 25 or more single family dwellings by modern

on-site construction methods was eligible for mortgage

insurance on very liberal terms. Individual dwellings

could later be released from the blanket mortgage

and sold to individuals who in turn could avail them

selves of the individually insured mortgage.

(e ) Section 903— Homes.

This program was devised in 1951 to relieve the

housing situation in critical defense areas. The area

must be designated by the president as critical. Mort

gage insurance is issued on one or two family units.

To be eligible for insurance a mortgage need not be

“ economically sound” (the requirement under Sec

tion 203) but it is sufficient if the proffered mortgage

is “ an acceptable risk in view of the needs of national

defense” .13 Credit terms are liberal. The statutory

regulatory features of housing built under this sec

tion is an almost complete one: Persons engaged in

defense had priority to purchase or rent; the prop

erty may be held for rent for such time as the Com

missioner determines; where properties are held for

rent the Commissioner may determine the rental and

prescribe operating methods and even prohibit or

restrict sale and the mortgagor may not discriminate

against families with children on penalty of $500 fine.

(12 USCA 1750a(d).)

13This requirement— that the mortgage be an “ acceptable

risk”— changes the class from that defined in Section 203 where

the loan must be “ economically sound” .

33

( f ) Section 207— The P ro ject Housing.

Housing built under Section 207, and the sections

that we will discuss following it, is so-called project

housing. The degree of FH A control over this kind

of housing is much greater than that exercised under

the various sales-housing programs. When Congress

set up the mutual mortgage system under Section

203 it created a system of mortgage insurance under

Section 207 for rental developments. Together Sec

tion 203 and Section 207 constitute the “ permanent”

FH A program. There must be at least twelve dwell

ing units; the builder must be a “ public corporation”

or a “ private corporation publicly regulated” . The

statute requires FH A regulation as to “ rents or sales,

charges, capital structure, rate and return and meth

ods of operation . . . to provide reasonable rentals . . . ”

The FH A Commissioner is authorized to hold such

stock (not to cost him more than $100) as will render

his regulation effective. FH A prescribes the method

and manner of bookkeeping and when there is any

violation of the terms the Commissioner may oust di

rectors and elect his own board. The social purpose

is explicit: “ Mortgage insurance under this section is

intended to facilitate rental accommodations at rea

sonable rents suitable for family living.”

(g ) Section 608— Housing.

Four-fifths of all project mortgages insured by

FH A have been insured under Section 608, a fact

traceable to its liberal terms. (Sixth Annual Report,

Housing Agency.) As established in 1941, Section 608

provided that “ the property shall be designed for

34

rent for residential use by war workers” and as re

vived in 1946 it was said to be designed to give prefer

ence to veterans. As in Section 207, the F H A Com

missioner is empowered to intervene in corporate af

fairs where there is a violation of regulations which

are substantially the same as in Section 207.

(h ) Section 610— Special Program.

Section 610 is a special program whereby FH A

mortgage insurance is provided to finance the sale

of so-called Greenbelt towns, TY A housing or Lan-

ham Act housing. There are the usual veteran prefer

ence provisions and power to require that the dwell

ings be held for rental.

( i ) Section 908— Liberal Terms.

Section 908 complements Section 903 in that it was

devised “ in view of the needs of national defense” .

The pattern of regulation is substantially the same

as that in Section 603 and 608, with the usual stock

holding powers vested in the Commissioner.

( j ) W herry M ilitary Housing.

The Wherry program originated in 1949 in order

to relieve the housing near military installations. Un

der this program, the military acquires the land, ap

proves the sponsor, draws the original plans and cer

tifies to FH A that the installation itself will not be

curtailed in the foreseeable future. FH A does not

even have to make a determination of acceptable risk.

It insures the loan and, as in Section 908, controls

the affairs of the corporation as to compliance with

35

its rules and regulations. Insurance is available on

a principal amount not exceeding 90% of replace

ment cost.

(k ) Section 213— Cooperative Housing.

Congress deliberated as to this program on the

issue of whether to grant direct public loans or to

provide for mortgage insurance for private loans. It

chose the latter. Housing is of two types: sales and

management. In the sales type, a non-profit corpora

tion builds the homes for members who take indi

vidual title to their homes. In the management type,

title remains vested in the corporation and member-

stockholders have permanent occupancy rights. FH A

is authorized to furnish technical advice and assist

ance in organization of the cooperatives, and in the

planning, development, construction and operation of

their housing projects. The loan may be amortized

in 40 years and mortgage insurance will issue on 90%

of replacement value. Under the 1956 amendments,

insurance will issue for 95% of replacement value

where 50% of member-stockholders are veterans.

Summary.

This rather detailed description of the manner in

which F HA and the operative builder complement

each other in the case of Section 203 housing (the

kind involved in this case) and the thumbnail

sketches of its functioning in other housing programs

reveals a federal, that is governmental, agency of

vast proportions and vast powers. Its regulatory

powers vary as the type of housing varies but none

36

can doubt that the mortgage insurance system it oper

ates and supervises is an important factor in the

housing market. It is time to take a closer look at

the scope of the agency’s power and how that power

is exerted.

P. FHA Regulation and Control.

The National Housing Act authorized the estab

lishment of a new agency of government in an area

in which there was little in the way of experience

to serve as guideposts. What Congress wanted was

an agency that would, as Senator Fletcher put it, help

achieve the objectives of the Act. (78 Cong. Rec.

12013, 1934.) From his statement, it was apparent

even then that the destiny of F H A was to be that

of the “ prime regulator” of the housing market. It

has fulfilled that destiny. FH A has dictated “ the

place where housing would be built, at what price and

rent ranges, for occupancy by whom, under what

tenure, at what standards of construction, in what

kind of neighborhoods” . (Siegel, Shirley, The Legal

Relationship of FH A to Housing Aided Under Its

Various Programs, 1953 unpublished manuscript,

New York.) Its very name has passed into our

idiom; the term “ F H A housing” has a real meaning

in common parlance. Billboards, radio, television,

shout the builder’s message that “ FH A housing”

is a special kind of housing, stamped with the Great

Seal of government approval.

F H A ’s minimum Property Requirements have in

fluenced the location, planning and development of

new subdivisions, and have influenced, even altered,

37

standards of construction and design for the whole

industry. (Siegel: Legal Relationships, etc., Supra.)

In addition to fostering the single, long term, to

tally amortized home mortgage with its low down pay

ment and low interest rate, which has become stand

ard, FHA, in minimizing risk of loss involved to

government and in providing for standardization of

mortgage instruments, has created a new liquid in

vestment market, national in scope and operation.

PH A is also responsible for the trend toward develop

ment of large suburban housing projects and toward

use of large institutional lenders. The volume of

new residential construction, its distribution between

renter- and owner-occupied, have also been influenced

by PH A. (Richards, How FH A Mortgage Insurance

Operates, supra.) “ I f you really want to face the facts

about the housing market today, the FH A itself, un

der its present regulations, says to the private

builder: “You must not sell to families whose income

does not allow them to meet your scale o f payments. ’ ’ ’

(95 Cong. Rec. 12268, 1949.)

P H A has managed to revolutionize our mortgage

credit system, regulate the housing market, and set

standards for the home building industry, not only

as the result of its effort to achieve express objectives

of the National Housing Act, but by enforcement of

its Administrative Rules and Regulations and its

Minimum Property Requirements—including its Min

imum Construction Requirements, which operate as

a super building code, and its Minimum Planning Re

quirements, which operate as a super zoning code.

38

Contrary to popular belief, FH A does not, as we

know, lend money. It insures mortgages. The mort

gagee pays an insurance premium of :1/i> of 1% of the

original face amount of the mortgage. Thereafter,

the mortgagee pays annually ^2 ° f 1% of the average

outstanding principal. While this premium is ac

tually paid by the mortgageee, in the long run it is

paid by the mortgagor as a part of the cost of bor

rowing money. The secret of FH A power and control

of the housing market is enfolded within this mort

gage insurance system.

In 1934, when the National Housing Act was

passed, the nation was still trying to recover from

the worst economic depression in its history. Home

construction had declined to an all-time low and mort

gage credit was almost completely frozen. (90 Cong.

Bee. A2984,1944.) The Act was designed to make home

construction possible by facilitating the flow of mort

gage credit. {Cong. Bee. 12013-12014,1934.) The device

proved so useful that when Congress was confronted

with the critical lack of housing for defense workers in

W orld W ar II, it utilized the same plan. The same

thing happened when there was a need for housing for

veterans. (96 Cong. Bee. 3152, 1956.) With respect to

all of these programs, Congress has clearly recognized

and understood that without government insurance or

guarantee, mortgage credit for construction and pur

chase of desperately needed housing would not be

available. (83 Cong. Bee. 1334, 1938; 87 Cong. Bee.

1544, 1944; Hearings Before Committee on Banking

and Currency, 78th Cong. 1st Session, 2, 7, 8, 1943;

39

90 Gong. Rec. A2985, 1947.) As one Congressman put

it:

“ For more than a decade now the housing in

dustry in this country has required Government

assistance and intervention for its very existence.

Only the tiniest fraction of the volume of housing

which has been erected in the past 10 years would

have actually been constructed without Govern

ment insurance of mortgages, and without the

massive governmental support behind the whole

mortgage market.

“ . . . It is a glaring fact that no practical person

can gainsay that few operative builders . . . con

duct their businesses with what is properly called

private capital . . . The average builder has very

little, i f any, risk capital involved in his busi

ness; he works with funds which he is able to

borrow because the Government has guaranteed

the lender against loss . . .” (Rep. Rodino, 95

Gong. Rec. 12268, 1949.)

In February, 1955, the Senate Committee on Bank

ing and Currency warned that “ to remove the sup

port of the FH A mortgage insurance programs from

the carrying out of these projects would cause unfair

and in some cases calamitous results.” (Senate Report

33, 84th Cong., 1st Session.)

Thus the first importance of federal assistance in

this case is that without it the operative builders

would not be able to obtain the necessary financing

for developments of the size that were involved in

this lawsuit. As one adverse witness put it in our

case, it would be “ virtually impossible” to build de

40

velopments of the size involved “ without FH A assist

ance” .

One of the basic purposes of the National Housing

Act was to introduce reforms in our mortgage proce

dure (78 Gong. Bee. 11973, 1934) in order to provide

home seekers with a mortgage credit system more

realistically designed to meet their needs, and it is

for that reason that F H A in the past twenty years

has completely revolutionized America’s mortgage

credit system. (90 Cong. Bee. A2984-A2985, 1944.)

As a result of reforms introduced, the home owner

today can get a fully amortized, long-term, low in

terest rate single mortgage at the lowest cost in his

tory. In place of the old first mortgage representing

50 to 60 per cent of the value, with second and third

mortgages at near-usurious interest rates, home own

ers today can obtain one loan up to 80 or 90, and

in some cases even 95, per cent of the FH A property

valuation. Parenthetically, the extent of FH A in

volvement in builder activities inheres in the very pro

cedures just referred to: it is FH A which sets the

valuation. The ratio of loan to valuation— whether 80

or 90 or 95 per cent—is determined toy FH A in accord

ance with statutory directive and the same is true as to

interest rates with the added feature that FH A may,

as it has recently done, raise the interest rate, within

statutory limits, for a social purpose, that is to curb

inflationary trends.

Where the traditional mortgage fell due in three

to five or ten years with uncertain and high renewal

fees, F H A mortgages are payable in equal monthly

41

installments over a period up to thirty years without

the necessity of renewal and without payment of a

premium for this privilege. Interest rates have been

reduced as a result of F H A action to such an extent

that the average home owner can pay for his prop

erty, pay the interest, taxes and insurances, often at

a lesser amount than he would pay for renting a com

parable house. (90 Cong. Bee. A2985, 1944.) In short,

“ In financing their home purchases with FH A in

sured mortgages borrowers have the satisfaction of

knowing that they are buying a home upon a basis

that is within their earning power.” (90 Cong. Bee.

A2985, 1944.)

Thus the second importance of the federal assist

ance in this case is that it expands an otherwise lim

ited market into a mass market. “ The mass market

thus created will be further augmented by the econ

omies incident to large scale building operations en

couraged under the bill.” (Sen. Beport No. 1300, 75th

Cong., 2nd Session, 4, 1937; 96 Cong. Rec. 3154, 1950.)

The operative builder’s ability to advertise that a

federal agency has approved his development is of

inestimable value as an inducement to the buyer who

can rely on the fact that the purchase of an PH A

insured or Y A guaranteed home meets certain high

governmental standards.

Mortgage insurance is crucial to the operative

builder’s ability to build for the mass market. It is

the sine qua non for tract development.

The fact of government mortgage insurance pro

vided by the statutory congressional scheme and ad

42

ministered by F H A cannot be gainsaid. It exists. It

is there. It minimizes risk of loss by the lender and

redounds to the builder’s advantage, as was intended,

by supplying a ready reservoir of credit which, in

essence, guarantees the builder that he can find a

market for his product. The sale of mortgage insur

ance differs from the sale of a commodity because it

involves the assumption of risk by the purveyor. Gov

ernment’s role as the purveyor of mortgage insur

ance is always recognized but the argument is made

that this does not import government involvement

because, it is said, the system is an actuarial one in

which the mortgagee (in reality the mortgagor-buyer

who pays the ultimate cost) is merely purchasing a

service at its legitimate cost. The purport of this

argument seems to be that there is no government in

volvement if government so orders its affairs that

the system is run on a sound business basis. The con

tention is without merit in light of the social, that

is governmental, purposes served and intended to be

served by the mortgage insurance system. Govern

ment is in the insurance business not to make money

but to further the ends of the National Housing Act.

In any event, the statement is speculative and may, or

may not, stand the test of time.

The very idea of mortgage insurance is relatively

new and the only body of actuarial standards that

exists is that which has been developed by FH A itself

since 1934. As of December 31, 1954, F H A ’s various

funds had 26% billions of dollars of insurance in

force and $390 million in earned surplus. {FHA

43

Statement, No. 55-57, FHA, June 18, 1955.) With re

spect to the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund, the

fund under which housing in our case is insured, a

comparatively recent FH A actuarial study purports

to show that this particular fund “ attained a balance

status” at the end of 1954—a balance status being

defined as the time when earned surplus is equal to

or larger than the contingent liabilities of the fund.

{FHA Statement, No. 55-57, FHA, June 18, 1955.)

This means that as of that date, all estimated losses

and expenses could have been paid out of the surplus

in the event of “ adverse economic conditions of ap

proximately depression magnitude were to develop

immediately.” (F HA Statement, No. 55-57, FHA,

June 18, 1955.) Even this pride-packed statement

does not rule out the contingency, always present in

FH A operation of the mortgage insurance system,

that resort might have to be made to the public treas

ury which is the ultimate guarantor of this insurance

system.

However, there are five mortgage insurance funds

—low cost housing, military housing, national de

fense housing, war housing and multi-family housing

projects—which have not attained a balance status,

and as to these funds the contingency of resort to the

public treasury is ever present.

Laying aside the issue of balance status, however,

the crucial consideration demonstrating government

involvement is that although FH A operations are in

the process of becoming self-sustaining and have re

paid to the United States treasury almost all moneys

44

originally advanced by it for initial operation of each

of the funds since the beginning of the program—a

total of some $65 million dollars (FH A Report, 55-57,

FH A, June 18, 1955) the stubborn fact remains that

the United States treasury is ultimately liable for

repayment to the mortgagee of every penny of the

mortgages insured by FHA. “ . . . Under the FH A

system, the federal government guarantees to pay

any loss which a lender sustains on any FH A insured

home mortgage loan. I f an insured loan is defaulted,

the FH A takes over the defaulted loan or property

and gives the lender F H A debentures in an amount

equal to the unpaid balance of the defaulted loan.

Those debentures are fully and unconditionally guar

anteed, as to payment of both principal and interest,

by the United States of America. The appropriate

FH A insurance fund, or reserve for losses, is pri