Burns v Lovett Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1953

31 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burns v Lovett Brief for Petitioners, 1953. 4aad1e19-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/26c31703-fe4a-482d-a8a7-8da2c8dd77af/burns-v-lovett-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

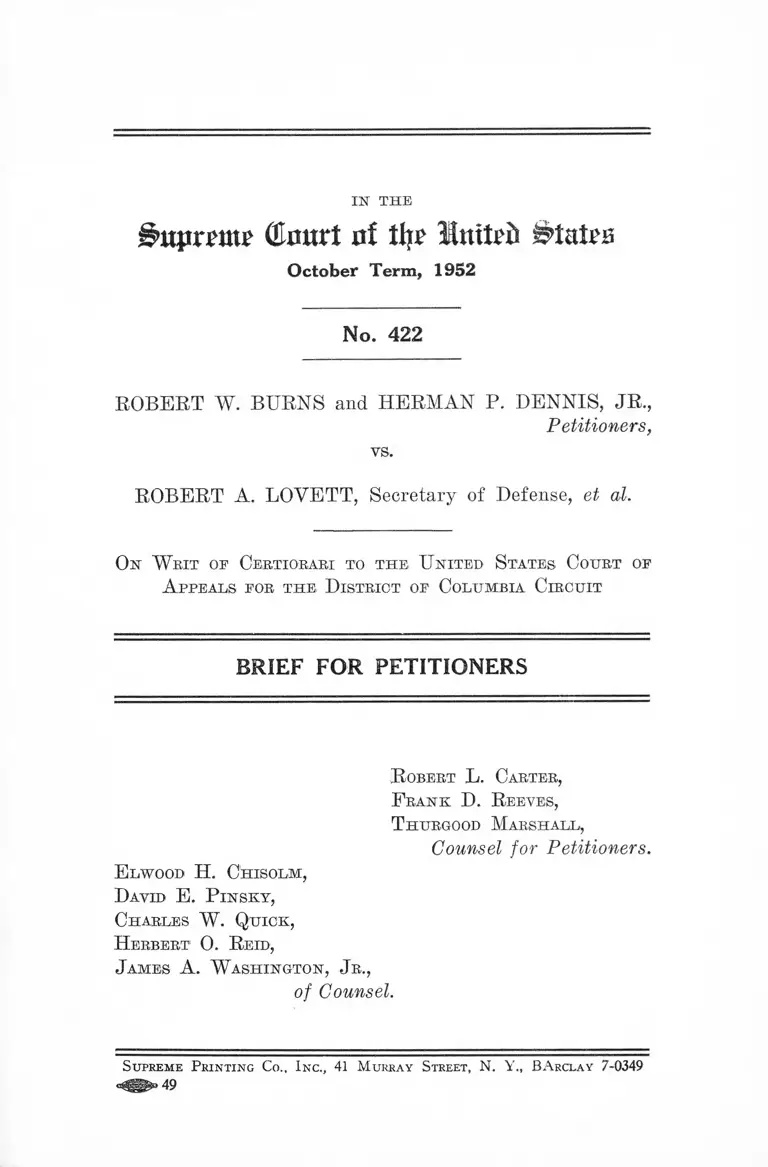

IN THE

(Emtrt of tlj?

October Term, 1952

No. 422

ROBERT W. BURNS and HERMAN P. DENNIS, JR.,

Petitioners,

vs.

ROBERT A. LOVETT, Secretary of Defense, et al.

O n W rit oe Certiorari to t h e U nited S tates C ourt oe

A ppeals eor the . D istrict oe Colum bia Circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

R obert L . Carter,

P ran k D . R eeves,

T hurgood M arshall ,

Counsel for Petitioners.

E lwood H . C h iso lm ,

D avid E . P in s k y ,

Charles W . Qu ic k ,

H erbert 0 . R eid,

J am es A . W ashington , J r .,

of Counsel.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 41 Murray Street, N. Y., BAkclay 7-0349

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion op Court Below ................................................. 1

JuRISDICTON ........................................................................ 1

Statement1 .......................................................................... 2

Specification of Errors..................................................... 5

Summary of A rgument..................................................... 5

A rgument............................................................................ 7

I— The scope of inquiry on writ of habeas corpus

extends to an examination of the military proceed

ings to determine whether basic constitutional guar

antees have been vio la ted ......................................... 7

II— The rule of judicial self-restraint applied by the

court below is not appropriate to this case.............. 10

III— Even if the rule announced by the Court of

Appeals is considered applicable to this case, peti

tioners were entitled to a hearing on the merits in

the District Court........................................................ 17

IV— The use by military authorities of evidence ille

gally secured in petitioners’ courts-martial renders

these convictions void ........................................ 20

Conclusion.......................................................................... 24

Table of Cases Cited

Adams v. United States, 317 U. S. 269............................. 18

Anderson v. United States, 318 U. S. 350, 356.. . . 19, 21, 22

Batson v. United States, 137 F. 2d 299 (C. A. 10t,h

1943).................................................................................. 16

Becker v. Webster, 171 F. 2d 762 (C. A. 2d 1949).......... 8

Betts v. Brady, 316 U. S. 455............................................. 18

Brosius v. Botkin, 110 F. 2d 49 (C. A. D. C. 1940). . . . 18

PAGE

II

Carter v. McClaughry, 183 U. S. 365............................. 7

Chambers v. Florida, 309' U. S. 227................................. 20

Clawans v. Rive-s, 104 F. 2d 240 (C. A. D. C. 1 9 3 9 ).... 16

Coggins v. O’Brien, 188 F. 2d 130 (C. A. 1st 1951). .10,11,16

Collins v. McDonald, 258 U. S. 4 1 6 ................................. 7,11

Darr v. Burford, 339 TJ. S. 200................................. 10,11,18

Ex parte Reed, 100 U. S. 13.............................................7,14

Felts v. Murphy, 201 U. S. 123........................................... 7

Givens v. Zerbst, 255 U. S. 11............................................. 11

Glasgow v. Moyer, 225 TJ. S. 420’..................................... 7

Glasser v. United, 315 U. 8. 601......................................... 16

Goodwin v. Smyth, 181 F. 2d 498 (C. A. 4th 195 0 ).... 10

Henry v. Hodges, 171 F!. 2d 401 (C. A. 2d 1948).......... 8

Hiatt v. Brown, 339 U. S. 103........................................... 8, 9

Hicks v. Hiatt, 64 F. Supp. 238, 249, 250, n. 27 (M. D.

Pa. 1946) .......................................................................... 12

Holiday v. Johnston, 313 U. S. 342, 350..................... 16,18

Humphrey v. Smith, 326 U. S. 695 ................................. 8

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458....................................7,16

Keizo v. Henry, 211 U. S. 146......................................... 7

Kuykendall v. Hunter, 187 F. 2d 545 (C. A. 10th 1951). 8

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219, 236......................... 19

McClaughry v. Deming, 186 U. S. 49............................. 7

McNabb v. United States, 318 U. S. 332..........19,21,22,23

Montalvo v. Hiatt, 174 F. 2d 645 (C. A. 5th 1949).......... 8

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U. S. 103................................. 7

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86..................................... 7

Price v. Johnston, 334 U. S. 266.....................................16,18

Raymond v. Thomas, 91 U. S. 712, 716............................. 15

Rochin v. California, 342 U. S. 165................................. 19

Runkle v. United States, 122 U. S. 543............................. 11

PAGE

PAGE

i i i

Salinger v, Loisel, 265 U. S. 224..................................... 16

Schechtman v. Foster, 172 F!. 2d 339 (C. A. 2d 1 9 4 9 ).... 10

Schita v. Cox, 139 F. 2d 971 (C. A. 8th 1944)..................8,11

Schita v. King, 133 F. 2d 283 (C. A. 8th 1943)..............8,11

Smith v. O ’Grady, 312 U. S. 329..................................... 7

Sunal v. Large, 332 U. S. 174........................................... 7

Tarble’s Case, 13 Wall. 397, 413-414............................. 19

United States v. Baldi, 192 F. 2d 540 (C. A. 3d 1951);

cert, granted 343 U. S. 403 ........................................... l ln

United States v. Hayman, 342 U. S. 205..................... 19, 20

United States ex rel. Hirschberg v. Cooke, 336 U. S. 210 11

United States ex rel. Innes v. Hiatt, 141 F. 2d 664 (C. A.

3d 194 4 )............................................................................8,16

Yer Mehren v. Sirmyer, 36 F. 2d 876 (C. A. 8th 1929).. 11

Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U. S. 708................................. 16

Wade v. Hunter, 336 U. S. 684........................................... 8

Waite v. Overlade, 164 F. 2d 722 (C. A. 7th 1947)... .8,11

Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101................................. 7,16

Walker v. Johnston, 312 U. S. 275................................. 16

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 49, 54................................. 18, 20

Weeks v. United States, 232 U. S. 383......................... 22

Whelchel v. McDonald, 340 U. S. 122................. ......... .. 8,9

Wilfong v. Johnston, 156 F. 2d 507 (C. A. 9th 194 6 ).... 16

Wrublewski v. Mclnerney, 166 F. 2d 243 (C. A. 9th 1948) 8

Other Authorities Cited

Antinean, Habeas Corpus Belief from Courts-Martial

Convictions, 28 Tex. L. Rev. 556 (1950)..................... 8n

Antineau, Courts-Martial and the Constitution, 33

Marq. L. Rev. 25 (1949)................................................. 8n

IV

Earle, The Preliminary Investigation in the Army-

Court Martial System— Springboard for Attack by

Habeas Corpus, 18 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 67 (1950 ).... 8n

Hearing Before a Sub-Committee of the Committee on

Armed Services, United' States Senate, on S. 857 and

H. R. 4085, 81st Congress, First Session..................... 14n

Karlen and Pepper, The Scope of Military Justice, 43

J. Crim. L. 285, 298 (1952)............................................. 15n

Keeffe and Moskin, Codified Military Injustice, 35 Corn.

L. Q. 151 (1949)................................................................ 14n

Langley, Military Justice and the Constitution-Improve

ments Afforded By the New Uniform Code of Military

Justice, 29 Tex. L. Rev. 651 (1951)............................. 14n

Mullally, Military Justice: The Uniform Code in Action,

53 Col. L. Rev. 1 (1953)...................................... 14n

Manual for Courts-Martial, United States Air Force,

156-158 (1949) ................................................................ 21

Note, Military Justice—A Uniform Code For The

Armed Services, 2 Wes. Res. L. Rev. 147 (1950 ).... 14n

Paley, The Federal Courts Look at Courts-Martial,

12 U. of Pitt. L. Rev. 7 (1950)..................................... 8n

Parker, Limiting the Abuse of Habeas Corpus, 8 F. R.

D. 171 (1949) .................................................................10,11

Report of the War Department Advisory Committee on

Military Justice (1946) (The Vanderbilt Report), at

pages 6 and 7 .................................................................12,13

Stein, Judicial Review of Determinations of Federal

Military Tribunals, 11 Brooklyn L. Rev. 30 (1941). . 8n

Werfel, Military Habeas Corpus, 49 Mich. L. Rev. 593,

699 (1951)

PAGE

8n

V

Statutes Cited

PAGE

Penal Code of Guam,

Section 686 .................................................................2n, 3, 20

Section 780 .................................................................2n, 3, 20

Section 825 .................................................................. 2n, 20

Chapter 35 of the Civil Regulation With the Force and

Effect of Law in Guam (1947)................................. 22, 22n

IN THE

IsrtjimnT (Emtrt nf Hit' t̂ati'G

October Term, 19S2

No. 422

•o-

R obert W. B urns and H erm an P. D e n n is , Jr.,

Petitioners,

vs.

R obert A. L ovett, Secretary of Defense, et al.

O n W rit of Certiorari to t h e U nited S tates C ourt of

A ppeals for th e D istrict of C olum bia C ircuit

---------------------- o-----------------------

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinion of Court Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals (R. 21-56) is not

yet reported.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

July 31,1952 (R. 57), and was amended on August 25, 1952

(R. 58). Petition for writ of certiorari was filed on October

29,1952 and was granted December 15,1952 (R. 58). Juris

diction of this Court rests on Title 28, United States Code,

Section 1254, subsection 1.

2

Statement

Petitioners are Negro Americans and citizen soldiers

now being held by military authorities at United States

Air Force Far Eastern Command, APO 500 unler sentence

of death. On May 9, 1949, and on May 29, 1949, petitioners

Herman Dennis, Jr. and Robert Burns were respectively

tried and convicted for the rape murder of Ruth Farns

worth, a white civilian, by general courts-martial convened

on the Island of Guam at Headquarters, 20th Air Force,

APO 234.

The judgments of the courts-martial were approved by

the convening authority, found legally sufficient by the

Judge Advocate General’s Board of Review and the Judi

cial Council, and the sentences of death were orderd exe

cuted by the President (R. 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 10, 16, 17). Peti

tioners filed timely petitions for new trials with the Judge

Advocate General, and on January 28, 1952, these petitions

were denied (R. 2, 9).

At this point, all available remedies provided within

the military establishment had been exhausted, and the

present collateral attacks on the validity of the courts-

martial judgments were instituted in the District Court.

On January 7, 1949, petitioners were surrendered to

the custody of federal civil authorities on Guam by the

United States Air Force (R. 2, 10).1 Petitioner Robert

Burns was held by civil authorities for several weeks

incommunicado and without process in a death cell at the

Agana Jail. He was subjected to continuous questioning,

beaten and denied edible food in violation of the Constitu

tion of the United States and the laws of Guam (R. 2, 3).2

1 At that time the United States Navy was charged with ad

ministering the civil government of the Island of Guam.

2 Penal Code of Guam, Sections 686, 780, 825. The text of these

provisions is set out in an appendix to the petition for writ of

certiorari at pp. 28-30.

3

He was not allowed to consult counsel during the entire

period he was held by Guam authorities (E. 3). As a result

of physical and mental duress, the other two accused-

petitioner Herman Dennis and one Calvin Dennis— signed

involuntary confessions implicating this petitioner in the

crime for which he was ultimately convicted (R, 3).

On or about January 30, he was returned to the custody

of the Air Force by civil authorities (R. 3). After the

Air Force regained custody, continued pressure and intimi

dation was exerted by military authorities to extract a

confession from him. Similar tactics were also used to

get Calvin Dennis and Herman Dennis to testify against

him (R. 3). These efforts did result in Calvin Dennis

being a witness for the prosecution at petitioner’s trial.

That testimony has now been repudiated by Calvin Dennis

as being false, perjured, and suborned by the prosecution

(R. 4).

Burns was denied the right of consultation with counsel

by military authorities until one day before his trial (R. 3),

and important evidence tending to show his innocence was

suppressed (R. 4). The entire proceeding’s were conducted

in an atmosphere of hysteria and terror in violation of due

process of law (R. 4).

Petitioner Herman Dennis was held incommunicado,

without process and in solitary confinement in the Agana

Jail by Guam police officers from January 7 until January

17, 1949. He too was subjected to continuous questioning,

beaten and denied sleep and food (R .ll) . He was not

allowed to consult counsel during the entire time he was

held in the custody of the authorities of Guam (R. 11).

During the period of his detention by Guam authorities,

he was not advised of his right against self-incrimination

as required under Sections 686 and 780 of the Penal Code

of Guam, Article of War 24 and the Fifth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States. He made four con

4

fessions to police authorities between January 11 and

January 14, which were the result of physical and mental

duress, protracted interrogation, threats, promises and the

use of a lie detector (R. 11). The tests of these confessions

were dictated by police officers, and subsequently petitioner

repudiated them as false (R. 11). Certain pubic hairs

were taken from his person and subsequently used against

him in violation of his right against self-incrimination

under the laws of Guam, the Articles of War and the Con

stitution of the United States (R. 12).

On or about January 29, petitioner was returned to the

custody of military authorities and was not afforded an

opportunity to consult counsel until shortly before his court-

martial trial which began on May 9, 1949 (R. 11). Evi

dence unlawfully obtained by Guam police was introduced

against petitioner at his trial in violation of his rights

under the Constitution and the Articles of War (R. 12).

Irrelevant, immaterial and inflammatory statements delib

erately calculated to prejudice petitioner’s cause were also

introduced (R. 12). Important evidence tending to show

his innocence was suppressed (R. 12); the prosecution

sought to procure witnesses to perjure themselves and

intimidated and threatened those who sought to help this

petitioner (R. 12). This trial was also conducted in an

atmosphere of hysteria and terror (R. 12-13).

The above-stated allegations, supported by affidavits,

were the bases for petitions for writ of habeas corpus filed

in the District Court. Respondents filed motions to dis

charge the rule to show cause and dismiss the petitions on

the ground that the petitions raised no questions review-

able by civil courts (R. 5-8, 15-18). The District Court, on

April 10, 1952, granted the motions to dismiss (R. 18-20).

Its opinions are reported at 104 F. Supp. 310, 312. The

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Colum

bia Circuit, with one judge dissenting, affirmed the judg

ment on other grounds (E, 43). Whereupon, we brought

the cause here.

5

Specifications of Errors

The Court of Appeals erred:

1. In not remanding the cause to the District Court for

a hearing.

2. In prescribing a rule for entitlement to a hearing

on the merits in habeas corpus proceedings which permits

military authorities to effectively foreclose inquiry by

civil courts into alleged violations of constitutional rights

by courts-martial.

3. In refusing to hold that on habeas corpus a district

court must make its own independent determination and

evaluation of the evidence relating to the claimed invalidity

of the judgment of the military tribunal.

Summary of Argument

The citizen-soldier being held on military authority

under sentence of death pursuant to a court-martial convic

tion should have the right to attack that conviction on writ

of habeas corpus on the ground that the military authorities

violated his constitutional rights and denied him the sub

stance of a fair trial. Where the petition for the writ makes

out a prima facie case on this ground, entitlement to a

hearing on the merits has been established. Indeed, in

federal custody cases, the only prerequisites for a hearing

on the merits are the showing on the face of the petition

that there has been a denial of constitutional rights and

that habeas corpus is the only effective remedy. In apply

ing a different set of standards to this case, the Court of

Appeals committed reversible error. Whatever merit its

standards may have, the Court of Appeals, by not remand

ing the cause to the District Court for proceedings in the

light of its decision, subverted its appellate jurisdiction,

and its judgment should be reversed.

6

While federal courts on habeas corpus have imposed a

rule of judicial self-restraint in many instances in state

custody cases for the purpose of preserving the delicate

federal-state balance, the bases upon which that rule rests

are absent in the instant case. In state custody cases, when

a petitioner seeks a writ in a federal court, his cause has

already been extensively examined and reviewed by the

state judicial machinery, and this Court has had an oppor

tunity to review the cause on application for certiorari.

This is not true in military cases for here petitioner’s first

contact with an independent judiciary occurs when he peti

tions the district court for the writ. Courts-martial are

courts of limited jurisdiction; and where their judgments

are attacked in federal courts, the duty is on the military

authorities to affirmatively show that the military tribunals

possessed the necessary ingredients for the rendition of a

valid judgment. Under these circumstances, it is strange

indeed to hold, as the Court of Appeals held, that federal

courts on habeas corpus cannot look behind the military

determination and independently inquire whether, in fact,

the military judgment was valid.

The allegations in these petitions, viewed in their totality,

establish a shocking picture of deviations from civilized

concepts of justice. Unless petitioners are entitled to invoke

the federal process to secure the protection which the Con

stitution affords citizens and soldiers alike, military courts

will be free to treat persons within their jurisdiction in any

fashion they desire. Since petitioners have made uncon

troverted allegations which if true would clearly show a

denial of the substance of a fair trial, they are entitled to

a hearing on the merits in the District Court.

7

ARGUMENT

I.

The scope of inquiry on writ of habeas corpus ex

tends to an examination of the military proceedings to

determine whether basic constitutional guarantees

have been violated.

The early cases involving collateral attacks on both

military and civil convictions in habeas corpus proceed

ings were limited to narrow and formalistic notions of

jurisdiction, i.e., whether the ingredients essential to a

valid assumption of jurisdiction existed. Collins v. Mc

Donald, 258 U. S. 416; Glasgow v. Moyer, 225 U. S. 420;

Keizo v. Henry, 211 U. S. 146; Felts v. Murphy, 201 U. S.

123; McClaughry v. Deming, 186 U. S. 49; Carter v. Mc-

Claughry, 183 U. S. 365; Ex parte Reed, 100 U. S. 13.

See Mr. Justice Frankfuter concurring in Sunal v. Large,

332 TJ. S. 174. More recently, in civil cases, the scope of

inquiry has been extended to ascertain whether the con

viction has occurred in disregard of constitutional guaran

tees. Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101; Smith v. O’Grady,

312 U. S. 329; Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458; Mooney

y. Holohan, 294 U. S. 103; Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S.

86. While lagging behind this expanded reach of the writ

as to civil cases, lower federal courts in the past decade

have begun to hold that on writ of habeas corpus a civil

court is empowered to examine the military proceedings

to determine whether specific constitutional rights were

violated and whether the trial was in accord with funda

mental notions of fairness implicit in our concept of due

8

process of law.3 Kuykendall v. Hunter, 187 F. 2d 545

(G. A. 10th 1951); Wrublewski v. Mclnerney, 166 F. 2d

243 (C. A. 9th 1948); United States ex rel. Innes v. Hiatt,

141 F. 2d 664 (C. A. 3d 1944); Schita v. Cox, 139 F. 2d 971

(C. A. 8th 1944); Schita v. King, 133 F. 2d 283 (C. A. 8th

1943); see also Montalvo v. Hiatt, 174 F. 2d 645 (C. A. 5th

1949); Becker v. Webster, 171 F. 2d 762 (C. A. 2d 1949);

Henry v. Hodges, 171 F. 2d 401 (C. A. 2d 1948); Waite v.

Overlade, 164 F. 2d 722 (C. A. 7th 1947).

This Court has indicated in recent decisions, at least

by inference, that on writ of habeas corpus a civil court

may appropriately inquire into whether guarantees of

due process have been observed by the military tribunal.

Whelchel v. McDonald, 340 U. S. 122; Humphrey v. Smith,

336 IT. S. 695; Wade v. Hunter, 336 U. S. 684. While

Hiatt v. Brown, 339 IT. S. 103 on which respondents relied

in the lower court appears to be a restatement of the

3 This expanded scope of inquiry on writ of habeas corpus into

whether the military trial violated petitioners’ constitutional rights

has been the cause of considerable comment. See Earle, The Pre

liminary Investigation in the Army-Court Martial System— Spring

board for Attack by Habeas Corpus, 18 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 67

( 1950) ; Antineau, Habeas Corpus Relief from Courts-Martial Con

victions, 28 Tex. L. Rev. 556 (1950), Antineau, Courts-Martial and

the Constitution, 33 Marq. L. Rev. 25 (1949) for discussion in

favor of review of military judgments by civil courts on writ of

habeas corpus extending to determine whether constitutional safe

guards had been observed. But see Werfel, Military Habeas Corpus,

49 Mich. L. Rev. 593, 699 (1951) ; Stein, Judicial Review of Deter

minations of Federal Military Tribunals, 11 Brooklyn L. Rev. 30

(1941) ; Paley, The Federal Courts Look at Courts-Martial, 12

U. of Pitt. L. Rev. 7 (1950) for arguments in favor of limiting the

scope of inquiry by civil courts on writ of habeas corpus to for

malistic and technical concepts of jurisdiction.

9

narrow, formalistic view of the permissible scope of

inquiry,4 it is there indicated that gross abuse of discre

tion with regard to the 8th Article of War would give

rise to a defect in the jurisdiction of the military tribunal

making it subject to collateral attack on writ of habeas

corpus. Moreover, Hiatt v. Brown, when viewed in the

light of Whelchel v. McDonald, gives little support to the

notion that the proceedings of a military tribunal con

ducted in violation of constitutional rights are not subject

to collateral attack.

The Court of Appeals is correct, we submit, in holding

that on habeas corpus civil courts may examine military

proceedings in order to determine whether a petitioner was

accorded fundamental fairness. Therefore, insofar as the

holding of the lower court sustains the right of a civil

court to inquire into whether the military trial was con

ducted in compliance with constitutional guarantees, we

think the court below is correct and that such a rule should

be expressly adopted by this Court.

All persons tried in our civil courts are protected by

the Constitution and may attack their convictions by habeas

corpus on the ground that their trials failed to conform

to requisite constitutional standards. It would be strange

indeed if American citizen soldiers, whose primary duty

is to defend our country and to preserve our democracy,

are deprived of rights which our courts will scrupulously

4 The Court did say at page 110; “ W e think the court was in

error in extending its review, for the purpose of determining com

pliance with the due process clause, to such matters as the proposi

tions of law set forth in the staff judge advocate’s report, the suf

ficiency of the evidence to sustain respondent’s conviction, the ade

quacy o f the pretrial investigation and the competence of the law

member and defense counsel.” None of these questions are in

volved in this case, and this statement cannot be taken to mean, at

least without explicit clarification by the Court, that no due process

questions can be raised on habeas corpus.

10

guard even when asserted by those whose purpose is the

destruction of our institutions. For these reasons, we

submit, the federal courts on habeas corpus should be

held to have jurisdiction to determine whether fundamental

constitutional prerequisites were complied with by military

tribunals.

II.

The rule of judicial self-restraint applied by the

court below is not appropriate to this case.

The Court of Appeals agreed with petitioners’ basic

contention that failure of a military tribunal to con

duct its proceedings in a fundamentally fair way would

render the validity of judgments subject to attack in

habeas corpus proceedings. But it added, “ habeas corpus

will not lie to review questions raised and determined, or

raisable and determinable, in the established military pro

cess, unless there has been such gross violations of con

stitutional rights as to deny the substance of a fair trial,

and because of some exceptional circumstances petitioner

has not been able to obtain adequate protection of that

right in the military process” (R. 32). Thereupon, the

court took up each of petitioners’ allegations, determined

that they had been either raised in the military process

and had been decided against petitioners, or that the con

tentions were without substance, or were not jurisdictional.

It then concluded that the facts before it did not depict

the exceptional case.

1. On habeas corpus federal courts in state custody

cases have adopted a rule of judicial self-restraint. See

Barr v. Burford, 339 U. S. 200; Coggins v. O’Brien,

188 F. 2d 130 (C. A. 1st 1951); Goodwin v. Smyth, 181

F. 2d 498 (C. A. 4th 1950); Schechtman v. Foster, 172

F. 2d 339 (C. A. 2d 1949). See also Parker, Limiting

11

the Abuse of Habeas Corpus, 8 F. R. D. 171 (1949). It

is this rule which here the court below held applicable

to the instant case. Federal courts which have adopted

this rule consider it essential to the maintenance of the

delicate balance in the federal-state relationship involved

in our federal system. Darr v. Burford, supra-, Coggins

v. O’Brien, supra. Whatever merits this rule of self-

restraint may have in state custody cases,5 the problems

incident to the maintenance of the delicate balance between

the United States and its courts and the state and its

courts do not come into play, where, as here, a petitioner

in federal custody applies to a federal court for a writ of

habeas corpus. Thus, the reasons for the application of

the federal rule of judicial self-restraint are not here

present.

In state custody cases, moreover, before the state con

victions can be subjected to collateral attack on habeas

corpus in the federal courts they must have been reviewed

or denied review by this Court on certiorari. Thus, an

accused in a state court is afforded at least one opportunity

for this Court to protect his rights before seeking a writ

in the federal courts.

2. Courts-martial are courts of inferior and limited

jurisdiction. United States ex rel. Hirshberg v. Cooke,

336 U. S. 210; Collins v. McDonald, supra. No presump

tion of legality or validity attaches to court-martial judg

ments when they are under collateral attack, Runlde v.

United States, 122 U. S. 543, and the grounds essential

to the validity of the assailed authority must affirmatively

be shown to have existed at the time of its exercise. Givens

v. Zerbst, 255 U. S. 11; Collins v. McDonald, supra; Waite

v. Ouerlade, supra; Schita v. King, supra; Schita v. Cox,

supra; Ver Mehren v. Sirmyer, 36 F. 2d 876 (C. A. 8th

1929).

5 Even as applied to state custody cases, however, this rule is

now the subject of conflict among the circuits. See United States v.

Baldi, 192 F. 2d S40 (C. A. 3d 1951); cert, granted, 343 U. S. 403.

12

If a denial of the substance of a fair trial renders the

court-martial judgment subject to attack for invalidity

on a habeas corpus, as the Court of Appeals indicates,

and if the ingredients essential to the validity of the judg

ment must be affirmatively established, as the cited cases

hold, it would seem to necessarily follow that it is the

inescapable duty of the civil court to determine for itself

whether those basic ingredients essential to the validity

of the court-martial proceedings were in fact present.

Such a determination cannot be left to military authori

ties. Thus, the expanded reach of the writ of habeas corpus,

viewed in the light of the concept of limited jurisdiction,

is at war with the rule of judicial self-restraint as applied

here. See Hicks v. Hiatt, 64 F. Supp. 238, 249, 250, n. 27

(M. I). Pa. 1946).

3. Judicial scrutiny of military trials by federal courts

is more essential than such scrutiny of state convictions.

The state judiciary is an independent arm of government

and is normally free from the pressures and influences of the

executive and prosecuting officials. This is not true of

military courts which are subject to command control. In

fact it is a fair statement to say that this influence is con

sidered the greatest weakness of military justice and has

been the subject of much concern. In the Report of the

War Department Advisory Committee on Military Justice

(1946) (the Vanderbilt Report), at pages 6 and 7 this

statement is found:

“ The Committee is convinced that in many in

stances the commanding officer who selected the mem

bers of the courts made a deliberate attempt to influ

ence their decisions. It is not suggested that all

commanders adopted this practice but its preva

13

lence was not denied and indeed in some instances

was frequently admitted. * * *

“ So far as the committee is informed, no steps

have been taken in the Army to check or prohibit

commanding officers in the exercise of their power

and influence to control the courts. Indeed the gen

eral attitude is expressed by the maxim that disci

pline is a function of command. ’ ’

And the committee goes on to specifically recommend that:

“ 6. The need to preserve the disciplinary au

thority of the command and at the same time to

protect the independence of the court can be met in

the following manner. The authority of the division

or post commander to refer a charge for a prompt

trial to a court-martial appointed by a judge advo

cate should be absolute * * * The right of command

to control the prosecution and to name the trial judge

advocate, who should be a trained lawyer, should be

retained. The Judge Advocate General’s Depart

ment, however, should become the appointing and

reviewing authority independent of command” (em

phasis added).

The suggestion that appointing power be removed from

command control, however, has never been incorporated in

any revisions of military law.

While criticism of command influence normally concerns

the relationship between the convening authority and the

courts-martial, at least one authority, Professor Arthur John

Keeffe, the former President of the General Courts-Martial

Sentence Review Board of the United States Navy, feels

that this influence renders even the highest judicial authority

in the armed services a partisan rather than an impartial

judicial officer. He said in testifying before a sub-corn-

14

mittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee on the

proposed Uniform Military Code:

“ The Judge Advocate General is not, and by the

very nature of his office and appointment, cannot be

an impartial judicial officer. He is in as inconsistent

a position as a commanding officer or convening

authority. He is to enforce discipline and he is to

give defense. It is for this reason that the English in

their reforms have provided that the Judge Advo

cate General be a civilian appointed on the recom

mendations of the Lord Chancellor and be respon

sible to him.

“ Significantly, in order to reduce this conflict the

English have removed the Judge Advocate General

from the control of the Secretaries for State and

_A.ir ̂ ̂ ^

“ To all intents and purposes there is no differ

ence between the Judge Advocate General and a dis

trict attorney in civilian life.” 6

4. Military law is a system of articles, rules and regu

lations established for the government of persons in the

military service. It deals in particularity with the main

tenance of discipline within the armed forces. See Ex

parte Reed, supra. Since ordinary rules of law do not

6 At page 252, Hearing Before a Sub-Committee of the Senate

Committee on Armed Services, United States Senate, on S. 857 and

H. R. 4080, 81st Congress, First Session. For other criticisms of

Uniform Code of Military Justice for its retention of command influ

ence, see also Keeffe and Moskin, Codified Military Injustice, 35 Corn.

L. Q. 151 (1949); Langley, Military Justice and the Constitution-

Improvements Afforded By the New Uniform Code of Military Jus

tice, 29 Tex. L. Rev. 651 (1951); Snedeker, The Uniform Code

of Military Justice, 38 Geo. L. J. 521 (1950) ; Note, Military Jus

tice— A Uniform Code For The Armed Services, 2 Wes. Res. L.

Rev. 147 (1950 ); Mullally, Military Justice: The Uniform Code

in Action, 53 Col. L. Rev. 1 (1953).

15

seek to cope with problems peculiar to the government of

the military establishment, a special set of rules may well

be indispensable in prosecuting- exclusively military offenses.

In such instances, courts-martial and military reviewing

authorities may be more competent to determine questions

involving military law, usage and internal administration,

and, therefore, it might be deemed illogical for civil courts

to interfere with the determination of such questions by

military tribunals. By the same reasoning it would seem

crystal clear that civil courts are better qualified to resolve

questions of constitutional and fundamental law arising in

a criminal prosecution where the offense charged is not of

a peculiarly military character and the accused may be tried

by either the military or civil authority. “ It is an unbending

rule of law that the exercise of military power when the

rights of the citizen [soldier] are concerned, shall never be

pushed beyond what the exigency requires.” Raymond v.

Thomas, 91 U. 8. 712, 716.

So long as the military services were composed of pro

fessional soldiers, there may have been some logic in allow

ing the court-martial system to determine conclusively the

meaning and application of constitutional provisions. To

day military personnel is largely conscript and the system

of “ military justice is the largest single system of criminal

justice in the nation. * * * ” 7 In addition to their authority

over exclusively military matters, military courts have

jurisdiction to try all offenses triable in civil courts.

These considerations call for greater rather than less

scrutiny by civil courts of military proceedings because

the constitutional safeguards should mean the same things

to soldiers and civilians. At the very least, the scope of

inquiry by civil courts of court-martial convictions should

7 Karlen and Pepper, The Scope of Military Justice, 43 / . Crim.

L. 285, 298 (1952).

16

not be restricted by a rule of judicial self-restraint where

the conviction complained of is for an offense not exclu

sively violative of military discipline or administration.

5. In applying its rule of judicial restraint the Court

of Appeals concluded that inasmuch as the Judge Advocate

General had determined petitioners’ allegations an insub

stantial basis for new trial, the District Court was pre

cluded from making any contrary determination of their

sufficiency. Since this conclusion cannot be based upon

other vital considerations as in the state custody cases,

petitioners submit that it is patently predicated upon a

principle indistinguishable from res judicata and ignores

this Court’s admonition that res judicata is not applicable

in habeas corpus proceedings. Salinger v. Loisel, 265 U. S.

224; Waley v. Johnston, supra at page 105.

6. This case involves solely federal habeas corpus juris

diction of federal custody cases. Where a case involves

persons in custody of federal authorities, the rule to be

applied requires but two determinations: (1) whether the

petition on its face alleges fafcts, which if proved, would

establish a denial of a constitution right, and, (2) whether

habeas corpus is the only effective means of preserving

such rights. See Glosser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60;

Johnson v. Zerhst, supra; Wilfong v. Johnston, 156 F. 2d

507 (C. A. 9th 1946); United States ex rel. Innes v. Hiatt,

141 F. 2d 664 (C. C. A. 3d 1944), and Batson v. United States,

137 F. 2d 299 (C. A. 10th 1943). Therefore, here it was

incumbent upon the Court of Appeals to order a hearing

on the merits in the District Court to provide petitioners

with the opportunity to establish the truth of their asser

tions. See Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U. S. 708; Johnson

v. Zerhst, supra; Clawans v. Rives, 104 F. 2d 240 (C. A. D. C.

1939); and see Coggins v. O’Brien, supra. Cf. Price v.

Johnston, 334 U. S. 266; Holiday v. Johnston, 313 IT. S. 342;

Walker v. Johnston, 312 IT. S. 275.

17

III.

Even if the rule announced by the Court of Appeals

is considered applicable to this case, petitioners were

entitled to a hearing on the merits in the District Court.

1. In the District Court, respondents’ motions to dis

charge the rule to show cause and dismiss the petitions

(R. 5-8, 15-18) and that court’s opinions and judgments

(R. 18-20) were directed to one issue: whether the permis

sible scope of the court’s inquiry on a petition for writ

of habeas corpus was limited to considerations of the

lawful composition of the courts-martial before which

petitioners were tried, jurisdiction of their person and

offense, and the lawfulness of the sentences imposed. On

appeal, this was the only question presented and argued.

The Court of Appeals below specifically passed on this

question, stating in its opinion (R. 25):

“ Appellants say that the recent decisions of

the Supreme Court have ‘ expanded’ the concept of

‘ jurisdiction’ for purposes of determining the right

to habeas corpus. That is correct # * * ” (em

phasis supplied)

and further (R. 31):

“ We proceed, then, upon the premise that the

protection of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments apply

to courts-martial, except for the specific exception

in the Fifth and the historic meanings at common

law of the terms used in both amendments * *

It is petitioners’ contention that at this point that the

Court of Appeals, having determined that the District

Court erroneously limited the scope of its jurisdiction to

exclude consideration of a habeas corpus petition alleg-

18

mg violation of fundamental due process, erred in failing

to remand the cause for application of the rule which it

held to be dispositive of the petition.

United States Courts of Appeals have no original juris

diction in habeas corpus proceedings. Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2241. See Adams v. United States,

317 U. S. 269; Brosms v. Botkin, 110 F. 2d 49 (C. A. D. C.

1940). Since this is true, and because Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2243, specifically provides that the

court, justice or judge to whom an application for a writ

of habeas corpus is made shall pass upon its sufficiency,

it is evident that the Court of Appeals is incompetent to

initially determine the sufficiency of such applications.

In the interest of justice, this Court and other federal

courts have long disregarded legalistic exactitude in the

examination of applications for the writ. Thus, even

though the petition is insufficient in substance, it may be

amended. See Barr v. Burford, 339 U. S. 200; Holiday

v. Johnston, 313 U. S. 342, 350. Consequently, in consid

ering propositions and matters which had not been con

sidered, developed or determined by the District Court

and in summarily precluding the possibilities of amend

ment, answer, traverse and hearing provided in Title 28,

United States Code, Section 2243, the Court of Appeals

subverted its appellate review in a manner which this

Court regards as reversible error. See Price v. Johnston,

supra.

2. Petitioners’ allegations make out a prhnie facie

case of denial of the substance of a fair trial by military

authorities. A proper appraisal of petitioner’s contention

can only be obtained by viewing the allegations in their

totality. Betts V. Brady, 316 U. S. 455. Viewed as a

whole, petitioners’ allegations paint a shocking picture of

injustice highlighted by the “ pressure otf unrelenting

interrogations” which this Court condemned in Watts v.

19

- i

Indiana, 338 U. S. 49, 54; a working arrangement between

two arms of the government in derogation of the rights

of the accused which was denounced in Anderson v. United

States, 318 U. S. 350, 356; “ a plain disregard of the duty-

enjoined by Congress upon federal law officers” as defined

in McNabb v. United States, 318 U. S. 332, 344; acts invading

the privacy of an accused which in Bochin v. California,

342 U. S. 165 was described as “ conduct which shocks the

conscience.” These factors, projected against a background

which includes subornation of perjury, deprivation of coun

sel and favorable witnesses, suppression of evidence, the

introduction of prejudicial and inflammatory testimony

and the conduct of the trials in an atmosphere of mob

hysteria and terror, renders inescapable the conclusion that

“ the whole proceeding is a mask” , Moore v. Dempsey, 261

U. S. 86, 91, and that petitioners’ trials lacked “ that

fundamental fairness essential to our concept of justice” .

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219, 236.

If these circumstances do not warrant issuance of the

writ, it is difficult to conceive what additional ingredients are

necessary to merit classification as the “ exceptional case.”

Indeed, if, as the Court of Appeals concluded, the circum

stances shown do not picture the denial of the substance

of a fair trial, if the allegations are insufficient to affect

the fundamental fairness of the courts-martial, and if the

disposition accorded petitioners’ claims does not impair the

validity of the subsequent military appellate determinations

sufficient to characterize this as an “ exceptional case” ,

petitioners submit that adherence to the rule applied by

the Court of Appeals effectively accomplishes suspension

of the writ of habeas corpus in cases involving solider

citizens in violation of Article I, Section 9, Clause 2 of the

Constitution. See Tarble’s Case, 13 Wall. 397, 413-414.

Cf. United States v. Hayman, 342 U. S. 205. Further

more, it cannot be said in habeas corpus arising out of

court-martial convictions that the rule merely operates

to “ minimize the difficulties encountered in habeas corpus

20

hearings by affording the same rights in another and more

convenient forum” United States v. Ray man, supra,

This is the type of case with which this Court and the

federal courts have dealt with on innumerable occasions.

A Negro is accused of a crime of passion or violence against

a white woman. Such accusations test the strength of our

constitutional guarantees. This Court, however, has evolved

standards and restraints which must be observed in order

to prevent convictions under such circumstances from being

acts of tyranny and injustice rather than the impartial

application of the law. See Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S.

227; Watts v. Indiana, supra. We submit, the military pro

ceedings here violated all standards of civilized judicial

conduct, and that petitioners should have been allowed to

prove in the District Court the merits of their contentions.

IV.

The use by military authorities of evidence illegally

secured in petitioners’ courts-martial renders these con

victions void.

As the facts reveal, petitioners were released by military

authorities to custody of the civil authorities of Guam,

jailed and held incommunicado by the latter without process

for a prolonged period of time. This procedure was in

clear violation of Sections 686, 780 and 825 of the Penal

Code of Guam, which guarantee to the accused the right and

visitation of counsel, privilege against self incrimination,

and protection against detention by police authorities with

out process.

In our view these provisions were applicable to all per

sons within the jurisdiction of that government. Had peti

tioners been tried by the civil authorities and if the evidence

obtained by the civil police under the circumstances set

forth here had been introduced at their trials, the convic

21

tions would unquestionably be invalid under the rule stated

by this Court in McNabb v. United States, supra.

The Court of Appeals dismissed this argument on the

ground that the McNabb rule was merely a rule of evidence.

But this, we submit, does not dispose of petitioners’ con

tention. The question posed is whether courts-martial may

lawfully use evidence illegally obtained by another arm of

the federal government. The 38th Article of War, which

Vas in effect at the time these courts-martial took place,

provides that the rules of evidence generally recognized in

the trial of criminal cases in the district courts of the United

States .shall apply insofar as the President deems them prac

ticable. Rule 124 provides that insofar as not otherwise

prescribed in the Manual, the rules of evidence generally

recognized in the trial of criminal cases in district courts

shall be applied. Manual for Courts-Martial, United States

Air Force 150 (1949). Thus, in the absence of any con

trary regulations the courts-martial should have applied

the rules in use in the district court and evidence unlaw

fully obtained should not have been admitted. See McNabb

v. United States, supra. The fact that civil authorities un

lawfully obtained the evidence introduced at the courts

martial does not make such evidence admissible. Anderson

v. United States, supra.

Rule 127, which specifically deals with the subject of

admissibility of confessions, contains nothing which ex

pressly negatives the applicability of the McNabb and

Anderson rules to courts-martial. Manual for Courts-

Martial, United States Air Force 156-158 (1949). In fact

the rule can well be interpreted as adopting the McNabb

principle. Rule 127 states that: “ No statement, admission,

or confession of an accused obtained by use of coercion or

unlawful influence shall be received in evidence in any

courts-martial.” (emphasis supplied). The use of the

phrase “ coercion or unlawful influence” clearly implies

that “ unlawful influence” constitutes something in addi

tion to “ coercion.” Certainly the term “ unlawful influ

22

ence” might well refer to a confession obtained during a

period of unlawful detention.

It should be noted here that in other instances where

the courts-martial Manual intends to render inapplicable

to courts-martial a particular federal rule, this intention is

expressed in no uncertain terms. For example, Buie 138

makes lawful a search of property owned or controlled by

the United States when authorized by the commanding offi

cer having jurisdiction over the locality where the prop

erty is located. This rule was intended to limit, the appli

cation of the doctrine of Weeks v. United States, 232 U. S.

383, to courts-martial. But no such express provision nega

tives the applicability of the McNabb and Anderson rules

to military proceedings.

The military reviewing authorities disregarded this con

tention on the ground that Chapter 35 of the Civil Regula

tions With the Force and Effect of Law in Guam (1947)

operated with regard to military personnel in lieu of Sec

tions 825 and 847-849 of the Penal Code of Guam.8

8 Chapter 35 provides:

“ 1. Whenever a member of the military forces of the

United States is arrested by civil authorities, the offender

shall be taken to the police station where the charge shall be

investigated. If the charge is considered substantial, he may

then be released upon his own cognizance or turned over to

military authorities. Should the chief of police consider the

charge of a sufficiently serious nature so that special action

is necessary or that the release of the offender would be detri

mental to his own or the public welfare, the offender may be

held pending action on the report of the chief of police to

military authority.

“ 2. The chief of police will, within 24 hours of the arrest,

forward a report to the commanding officer of the offender and

will set forth therein the offense alleged, such details as may

be necessary to permit the commanding officer to take intelli

gent action on the case, and the names of such witnesses as

may be available. He will also forward one copy of this

report to the office o f the Governor, for file.”

23

It should be noted at the outset that neither the Civil

Regulations nor the Penal Code expressly authorize Chap

ter 35 to operate in lieu of the Penal Code in eases involv

ing military personnel. Moreover, it is submitted, Chapter

35 can have no application to this case.

The plain meaning of this chapter is that its provisions

shall be followed when military personnel are initially ap

prehended by civil authorities on Guam. In the instant

case, petitioners were actually surrendered by the military

to officials of the civil government. This fact in itself serves

to render Chapter 35 inapplicable here, for it can have no

possible meaning in the context of this case.

Further, the record makes it clear that both the military

and the civil officers contemplated that petitioners would be

tried by civil authorities. The very fact that the military

released petitioners strongly leads to this inference. But

even more persuasive is the revelation at pages 227, 232 of

the court-martial record of petitioner Herman Dennis that

he was actually arraigned before a magistrate after con

fessions were extracted from him. Under these circum

stances, neither the military nor the civil authorities can

now validly claim that the protections afforded by the Penal

Code of Guam were inapplicable to these petitioners.

The rule of the McNabb case is much more than an

important rule of evidence. It represents the expression of

a strong policy that federal courts cannot convict an accused

on the basis of evidence obtained during a period of pro

longed unlawful detention and interrogation. The use of

such evidence would vitiate any conviction in a federal court.

Petitioners submit that the use of such evidence by these

courts-martial and the failure of the reviewing authorities

to correct this clear error of law vitiates their convictions.

24

Conclusion

W herefore, it is respectfully submitted that the judg

ment of the Court of Appeals should be reversed and the

cause remanded for a hearing on the merits.

R obert L. Carter,

F r an k D. R eeves,

T hurgood M arsh all ,

Counsel for Petitioners.

E lwood H . C h iso lm ,

D avid E . P in s k y ,

Charles W . Q u ic k ,

H erbert1 0 . R eid,

J am es A. W ash ing to n , Jr.,

of Counsel.