Myers v. Gilman Paper Company Response of Plaintiffs-Appellees to the Unions' Petitions for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

July 4, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Myers v. Gilman Paper Company Response of Plaintiffs-Appellees to the Unions' Petitions for Rehearing, 1977. b5b3a3fd-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/26c67ce0-03f0-4b4d-a105-b52d63816275/myers-v-gilman-paper-company-response-of-plaintiffs-appellees-to-the-unions-petitions-for-rehearing. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

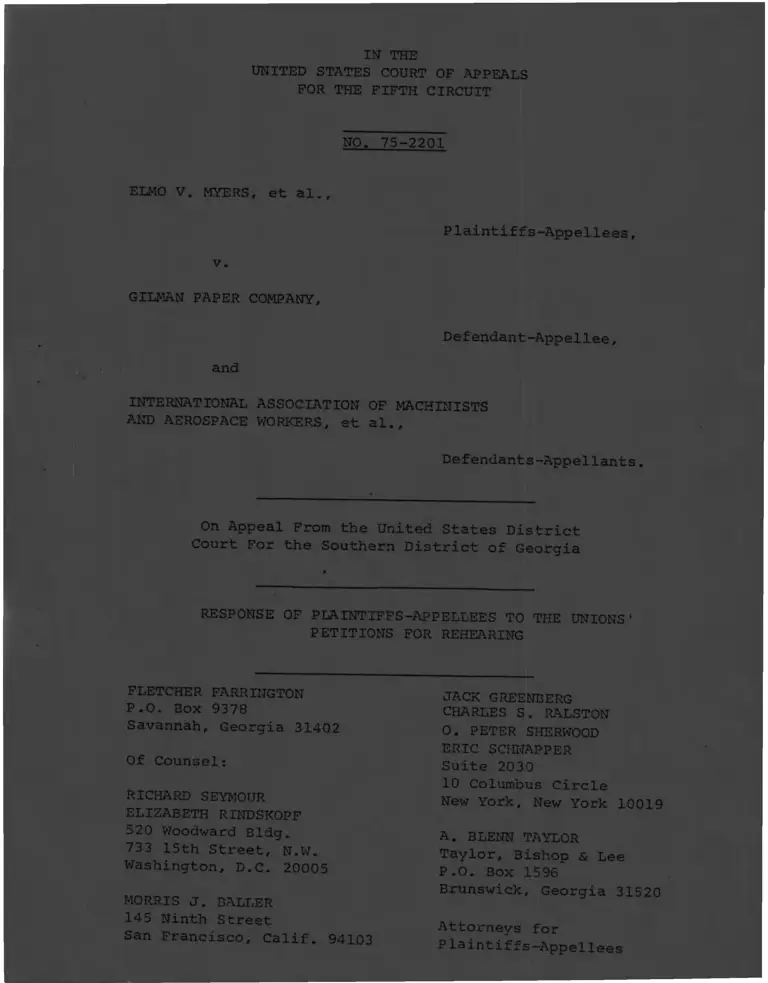

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 75-2201

ELMO V. MYERS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

GILMAN PAPER COMPANY,

Defendant-Appellee,

and

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF MACHINISTS

AND AEROSPACE WORKERS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal From the United States District

Court For the Southern District of Georgia

RESPONSE OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES TO THE UNIONS'

PETITIONS FOR REHEARING

FLETCHER FARRINGTON

P.O. Box 9378

Savannah, Georgia 31402

Of Counsel:

RICHARD SEYMOUR

ELIZABETH RINDSKOPF

520 Woodward Bldg.

733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

MORRIS J. BALLER

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, Calif. 94103

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES S . RALSTON

O. PETER SHERWOOD

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A. BLENN TAYLOR

Taylor, Bishop & Lee

P. O. Box 1596

Brunswick, Georgia 31520

Attorneys for

Plaintiffs-Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities..................................... ii

I. INTRODUCTION....................................... 1

II. THE FACTS IN THIS CASE REVEAL A

SENIORITY SYSTEM WHICH WAS DESIGNED,

NEGOTIATED AND MAINTAINED WITH A

DISCRIMINATORY PURPOSE............................ 5

III. THE "INTERVENING SUPREME COURT DECISIONS

DO NOT AFFECT THE RESULTS REACHED BY

THE COURT IN THIS CASE............................ 11

A. The Seniority System in this Case

Is Unlawful Under Title VII.................. 13

1. Under the "Intervening Supreme

Court Decisions" Seniority Systems

That Are Tainted With a Discriminatory

Purpose Are Unlawful Under Title VII.... 14

2. The Seniority System in This Case

Is Tainted With Discriminatory

Purpose................................... 22

3. In This Case, The Unions Are

Liable.................................... 2 5

B. Plaintiffs' Claims Under 42 U.S.C.

§1981 Should Not Be Dismissed................ 25

IV. THE I.B.E.W. IS LIABLE IN THIS CASE.............. 27

CONCLUS ION............................................... 2 9

-l-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases;

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). . .

3, 10, 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). . .

5

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). . . 18

Guerra V. Manchester Terminal Corp., 498 F.2d 641

(5th Cir. 1974)... 12

Hazelwood School District v. United States, ___U.S.___,

45 U.S.L.W. 4882 (June 27, 1977). . . 22

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

___U.S.___, 45 U.S.L.W. 4506 (May 31, 1977). . .

1, 3, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 28

Interstate Natural Gas Co. v. Federal Power Commission,

156 F.2d 949 (5th Cir. 1946), aff'd 331 U.S. 682 (1947).

20

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364

(5th Cir. 1974). . . 12, 20

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454

(1975)... 25, 26

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969). . . 4, 10, 13, 18

Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., 450 F.2d 557 (5th Cir. 1971). .

12

Miller v. Continental Can Co., ___F. Supp. ___, 12 EPD

5 11,191 (S.D. Ga. 1976). . . 10

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d 283 (1969). . .

30

-li-

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

Cases (cont'd)

Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., 392 F. Supp. 413 (S.D. Ga.

1975). . . 8

Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., 544 F.2d 837 (1977). . .

2, 6, 10

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d 421

(8th Cir. 1970). . . 32

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974)... 12

Piedmont & N.R. Co. v. Interstate Commerce Commission,

286 U.S. 299 (1932)... 20

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896). . . 10

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505

(E.D. Va. 1968). . . 4, 17, 19

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340

(8th Cir. 1975)... 10

Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 516 F.2d 103

(5th Cir. 1975)... 10, 12

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 539 F.2d 77 (5th Cir. 1976). . .

12

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison, ___U.S.___,

45 U.S.L.W. 4672 (June 16, 1977). . . 2, 3, 4, 12, 15, 17

United Airlines, Inc. v. Evans, ___U.S.___45 U.S.L.W.

4566 (May 31, 1977). . . 2, 3, 4, 12, 13, 17, 19, 22, 23

United States v. Bethleham Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652

(2d Cir. 1971)... 18

United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co., 471 F.2d 582

(4th Cir. 1972)... 18

-iii-

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

Cases (cont'd)

United States v. First City National Bank, 386 U.S.

361, 366 (1967) . . . 29 ^

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906

(5th Cir. 1973)

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 456 F.2d

112 (5th Cir. 1972)... 12

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418

(5th Cir. 1971)... 12, 21

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d

123 (8th Cir. 1969)... 18

United States v. United States Steel Corp., 520 F.2d 1043

(5th Cir. 1975)... 12

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.,

___U.S.___, 50 L. Ed. 2d 450 (1977). . . 17, 21, 22

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976). . . 22, 29

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir. 1976). .

10

Watkins v. United Steelworkers, Local 2369, 516 F.2d 41

(1975)... 26

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. § 1981 . . . 4, 11, 25, 26, 27

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. • * * 4, 7, 11, 25, 26

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h) . . . 2, 3, 14, 16, 19, 21, 25, 30

-iv-

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 75-2201

elmo v . m y e r s , et ai..

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

GILMAN PAPER COMPANY,

Defendant-Appellee,

and

i n t e r n a t i o n a l a s s o c i a t i o n of m a c h i n i s t s

AND AEROSPACE WORKERS, et al. ,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal From the United States District

Court For The Southern District of Georgia

RESPONSE OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES TO THE UNIONS'

PETITIONS FOR REHEARING

I.

INTRODUCTION

Following the decisions of the United States

Supreme Court in International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, U.S. , 45 U.S.L.W. 4506

2

(May 31, 1977), (hereinafter referred to as "Teamsters");

United Airlines v. Evans, ____ U.S. ____ , 45 U.S.L.W. 4566

(May 31, 1977) (hereinafter referred to as "Evans"); and

Trans World Airlines v. Hardison, ____ U.S. ____ , 45 U.S.L.W.

4672 (June 16, 1977) (hereinafter referred to as "Hardison"),

the international and local unions in this employment

1/discrimination case petitioned for rehearing of this Court's

ydecision of January 3, 1977 holding them liable for the

economic loss suffered by the victims of their racially

discriminatory practices. Those cases hold that where

conduct prohibited by Title VII has not entered into the

establishment, negotiation or maintainence of a seniority

system, such system is immune under §703 (h) of Title VII of

the civil Rights Act of 1964, even though it perpetuates the

1/ Two petitions have been filed: one on behalf of the

I.B.E.W. only and another on behalf of all other union

defendants. In this response, references to the "Unions"

are to all the unions unless otherwise indicated. Citations

to the I.B.E.W. petition are denominated "IBEw Pet. p. ____ ".

Citations to the petition on behalf of the other unions are

denominated "Uhion p. ____ ". The designation "A-" refers to

citations to the joint appendix. The designation "Tr.-"

refers to pages of the trial transcript in the district court.

The designations beginning with "Myers", "Gilman", "UPIU",

"IAM", or "IBEW" followed by a hyphen and a number refer to

pages in the original brief filed in this Court by one of the

above mentioned parties. For example "UPiu-11" refers to page

11 of the Brief filed in this Court by the u p i u on July 28,

1975.

2/ The decision is reported at 544 F.2d at 837.

3

effects of past discrimination. But, where a discriminatory

purpose did enter into the establishment, negotiation or

maintenance of a seniority system, it is not shielded by the

limited immunity granted by §703(h). That discriminatory

purpose is present in this case.

Teamsters, supra, Evans, supra and Hardison, supra

do not invalidate, nor do they purport to invalidate, years of

3/universally accepted jurisprudence that has advanced, through the

development of workable and sensible rules, "the central statutory

purposes (of Title VII) of eradicating discrimination through

out the economy and making persons whole for injuries suffered

through past discrimination." Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 421 (1975).

3/ Citing to footnote 2 of Mr. Justice Marshall's dissent

in Teamsters, supra, the unions claim that these cases do

precisely that. See Unions - 11. They do not mention,

however, for obvious reasons, the next footnote in the

dissent which expressly agrees with the majority that the

earlier departmental seniority cases are not affected by

the Court's decision. See Teamsters, supra, 45 U.S.L.W.

4520, n. 3, (Marshall, J. dissenting) . The unions do not

address, again for obvious reasons, whether a seniority

system that, like the one at issue in this case, is

tainted with discriminatory purpose, is immune. instead,

they argue for reversal and dismissal of this action

because the district court did not reach the question.

4

The specific issues presented by the union'si/appeal to this Court all turn on whether the unions

violated either Title VII of the civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §2000e et_ seq. , or 42 U.S.C. §1981. Obviously,

Teamsters, supra, Evans, supra, and Hardison, supra, are of

importance to the Title vil issue. The questions they raise

have not been closely analyzed in many cases that were tried

after Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969). They require

a reinterpretation of the Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc..

279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968) line of cases. But, on the

facts in this record, which reveal a racially based seniority

system with whites in vertically structured jobs and blacks

vin laterally structured jobs they mandate no retreat from

this Court's January 3, 1977 ruling. Further, these decisions

in no way affect the unions' separate and independent

violations of 42 U.S.C. §1981. The facts in this record are

sufficient to permit this court to reaffirm its January 3, 1977

4/ Those issues are:

1) Whether the district court was entitled to approve the

consent decree offered by the plaintiffs and the

company that, in any way, altered the 1972 Supplemental

Labor Agreement;

2) Whether on remand the district court may entertain

evidence of union discrimination against blacks who

were hired and assigned to traditionally black jobs

after July 2, 1965; and

3) Whether the unions are responsible for a share of the

economic loss suffered as a result of past discrimination.

5/ See pp. 7-10, infra.

5

decision, albeit on different grounds. Neither reversal

nor dismissal is warranted in this case.

II.

THE FACTS IN THIS CASE REVEAL A SENIORITY

SYSTEM WHICH WAS DESIGNED, NEGOTIATED AND

MAINTAINED WITH A DISCRIMINATORY PURPOSE

In their initial brief and at oral argument,

plaintiffs described in detail the history of discrimination

at Gilman's St. Mary's Georgia facility and the Unions'

central role in the establishment and maintenance of an

employment structure which was designed to discriminate -

and succeeded in discriminating - against blacks. In the

context of the times, it is not surprising that the employ

ment structure, including the seniority structure, mirrored

the rigidly separate and inherently unequal character of

society. Cf. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954). This Court has noted the history of discrimination

at the plant, see e.g. 544 F.2d at 844, and it need not be

fully reviewed here. Repetition of some of the relevant

facts, however, is in order.

6

When Gilman opened its plant in 1941, someone -

presumably the company - filled all the skilled, higher

paying jobs with white people, and the dirty, low-paying,

back-breaking service, cleanup and unloading jobs with

black people. See Myers, supra, 544 F.2d at 844. At

the same time (or shortly thereafter), the international

unions, which had been voluntarily recognized by the

company, (A. 580), chartered new locals to represent

these employees and to assume jurisdiction over the

various jobs at the plant. The international unions

organized these new locals along precisely the same

racial lines as the company had initially assigned its

new employees despite the fact that no functional

purpose was served thereby. The International Brotherhood

of Pulp, Sulphite and Papermill Workers, Local 446 got

jurisdiction over the non-supervisory production, and

some craft, jobs in the pulp mill, some jobs in the

shipping department, and the higher-paying jobs in the

Woodyard (Tr. 48). United Paperworkers and Papermakers

Local 458 acquired jurisdiction over jobs in the paper

mill and some of the jobs in shipping (A. 474). The

International Brotherhood Electrical Workers obtained

7

jurisdiction over jobs in the Electrical Department,

the Powerhouse and the Instrument Department (A. 473),

and it chartered Local 741 to represent employees in

those jobs. The International Association of Machinists

organized the Mechanical Department, and it chartered

Local 1128 to represent those employees (A. 473).

Without exception, the membership of these locals was

white, and the employees in the jobs under their

jurisdiction were white. Black employees, whether they

worked in the Powerhouse, the Pulp Mill, the Woodyard,

Machine Shop or Paper Mill, became members of Local 616,

chartered by the International Brotherhood of Pulp,

Sulphite and Papermill Workers, and jurisdiction of the

jobs held by blacks was given to that Local (A. 474).

Unlike Local 616, none of the white locals enjoyed

6/

jurisdiction over jobs in all departments.

6/ The finding of a violation of Title VII for the

maintenance of segregated locals until 1970 (A.423)

was not appealed.

8

At about the same time, the unions and the company

negotiated a system of promotion to vacancies as they

Vopened up in the normal course of business. The unions

bargained for and got a seniority system that reserved all

of the benefits and advancement opportunities to the more

skilled, better paying and most desirable jobs for whites.

All of the dirty, low paying jobs leading nowhere were

assigned to the black bargaining unit. This job seniority

system together with the absence of provisions for the

posting of notices of vacancies "created an impenetrable

barrier to black employees to transfer to traditionally

all-white [jobs]", Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., 392 F. Supp.

413, 419 (S.D. Ga. 1975), long after the company abandoned

its discriminatory hiring policies in 1965.

The resultant system, described in the agreements

as "departmental seniority," was not a departmental

seniority system at all. Rather, the promotional system

followed precisely the segregated structure of the local

unions. It strictly prohibited blacks from moving to any

7/ The record is silent as to whether the Internationals

left the negotiation of these seminal agreements to the

fledgling locals, or whether, as seems probable, their

International Representatives negotiated them.

9

of the better jobs within the department that were held

by whites. A black employee assigned to the to the

lowest paying job in the Powerhouse could not, on the

basis of the seniority he had accumulated in that

department, move up to the next higher paying job in

that department when a vacancy occurred (the normal

procedure under a bona fide departmental seniority system).

That was true even in the Pulp Mill and Woodyard, which

were under the jurisdiction of the same International

Union as the black local. For blacks, promotions were

a function of local union membership. Since the black

local had jurisdiction of no jobs to which one could or

would want to be "promoted", for promotional purposes the

"seniority" system was, at its inception, meaningless for

blacks.

This racially structured seniority system, and

the unions' intent to perpetuate it, was reaffirmed in

1959, when the International Brotherhood of Pulp,

Sulphite and Papermill workers chartered a new union,

Local 958, to represent employees at the bag plant,

opened a few years earlier. The International assigned

10

jurisdiction of most of the jobs in the plant to the

new local. Black jobs, however, were assigned to the

jurisdiction of Local 616. And, just as it was in the

mill, seniority accumulated in Local 616 at the bag

plant was useless for promotion for a Local 958 job,

even though the jobs may have been in the same department.

See 544 F.2d at 845. Local 616 "seniority" was not bag

plant seniority, it was black seniority, and it was no

more neutral in its operation than were the railway

carriages from which Homer Plessy was barred. See

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 538-39 (1896).

The aforedescribed racial seniority system

8/

continued, with minor exceptions, until August 25, 1972.

(See Myers - 7-17).

8/ This system of granting promotions based on racially

accumulated seniority is typical of papermills in the

south. See Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers

v. United States, supra; Stevenson v. International Paper Co.,

516 F.2d 103 (5th Cir. 1975); Watkins v. Scott Paper Co.,

530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir. 1976); Rogers v. International

Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340 (8th Cir. 1975), vacated 423

U.S. 803 (1975); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 (1975); and Miller v. Continental Can Co., ___F. Supp.

___, 12 EPD 11,191 (S.D. Ga. 1976).

11

III.

THE "INTERVENING SUPREME COURT DECISIONS" DO NOT AFFECT

THE RESULTS REACHED BY THIS COURT IN THIS CASE

Plaintiffs in their complaint (A. 9) and amended

complaint (A. 19) alleged purposeful discrimination in

violation of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq. and 42

U.S.C. §1981 "with the intent and design to protect the

advantage, seniority and advancement opportunities of white

employees to the detriment of plaintiffs. . ." (A. 19-20).

In reliance on the numerous decisions in this and other

circuits that emphasized the concept of perpetuation of past

discrimination, plaintiffs below focused on the effects of

the discriminatory practices of Gilman and the unions.

Indeed, until the Supreme Court's May 31, 1977 and June 16,

1977 decisions, the unions assumed that, at least until

1972, the seniority system unlawfully discriminated against

9/

blacks. (UPIU-2, 8, 11-12; IAM-48-51; L741-21; IBEW-12).

9/ For example, throughout their brief, the UPIU refers to

the affected class as the "discriminatees". The district

court summarized a portion of the UPIU's defense as follows:

The United Paperworkers International Union and

its Locals 453, 446 and 958 contend that in 1970

they did everything within their power to correct

past discrimination (A. 418, emphasis added).

12

The arguments presented by the unions below and in this

Court addressed , not whether blacks at Gilman had been

the victims of unlawful discrimination, but what remedy,

if any, blacks were entitled to from the unions, given

the seniority reform effected under the 1972 Supplemental

10/

Labor Agreements. Not surprisingly, neither the district

court nor this Court addressed, except in passing, the

factual predicates discussed above that make this case

fundamentally different from Teamsters, Evans and Hardison.

Plaintiffs show below that those cases do not affect the

result reached under the facts of this case, and require

ii/

no retreat from the long line of departmental seniority

10/ The IBEW did not argue that the seniority system was

not unlawful but merely that no officer or representative

of the International had knowledge of its discriminatory

effect prior to August 1972. See IBEW-12.

11/ See e.g. Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491

F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974); Pettway v. American Cast Iron

Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974); Stevenson v.

International Paper Co., supra; United States v. United

States Steel Corp.. 520 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975);

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., supra; United States v. Georgia

Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973); United States v.

Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971);

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 539 F.2d 77 (5th Cir. 1976);

United States v. Hayes International, 456 F.2d 112 (5th

Cir. 1972); Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 498 F.2d

641 (5th Cir. 1974); and Long v. Georgia Kraft Co.. 450

F .2d 557 (5th Cir. 1971).

13

cases beginning with this Court's seminal decision in

Local 189, supra, and recently reaffirmed in this case,

which involve seniority systems that have their genesis

in racial discrimination. See Teamsters, supra, 45 U.S.L.W.

at 4511, n.28; and Evans, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4567, n.10.

A. The Seniority System in This Case is

Unlawful Under Title VII____________

In their petitions for rehearing the unions no

12/

longer assume, as they uniformly have heretofore, that the

seniority system, at least as it existed until August, 1972,

perpetuated the effects of past discrimination. No longer

do they focus their defense on what the unions and the

company did in August, 1972 to remedy the effects of past

discrimination. Instead they argue that the district

court did not, as the Supreme Court now appears to require,

focus on the plain fact, as reflected in the record in

this case, that the seniority system under attack here

12/ The IAM and Local 741, IBEW apparently take the view

that the recent Supreme Court decisions affect them in

precisely the same way that it affects the UPIU. Accordingly,

plaintiffs have no occasion to address separately the issues

raised by them in their earlier Briefs in this Court. (See

Unions 4, n.2). But see pp. 6-10, supra regarding the role

of all the unions in the establishment of a separate seniority

unit for blacks.

14

has its genesis in discrimination and is not bona fide.

(See Unions 3-4 and 11). While the legal analysis that

underlies a finding of union liability under Title VII

in this case is somewhat altered by the Supreme Court

decisions, the result is unchanged.

1. Under The "Intervening Supreme Court

Decisions" Seniority Systems That Are

Tainted With A Discriminatory Purpose

Are Unlawful Under Title VIV_________

In Teamsters, supra, the Supreme Court held that

where it is alleged that a seniority system merely has the

effect of discriminating, it is protected by the limited

immunity provided by §703(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

§2000e-2(h). See 45 U.S.L.W. at 4512. The Court rejected

the Government's broad argument that no seniority system

that tends to perpetuate the effects of pre-Act

discrimination can be "bona fide". See 45 U.S.L.W. at

4513. Similarly the Court concluded that a seniority

system cannot be shown to be "the result of an intention

to discriminate" merely because it may perpetuate past

discrimination. See 45 U.S.L.W. at 4513, n.39. In short,

a seniority system is immune from attack if plaintiff's

15

claim is addressed to its effect only.

The extent of the immunity, however, is limited.

A different result obtains where 1) the prohibited conduct

entered into the adoption, negotiation or maintenance of

the seniority system and 2) the seniority system presently

has the effect of discriminating. In Teamsters. supra,

the Court holds that:

. . . §703(h) does not immunize all

seniority systems. It refers only to

"bona fide" seniority systems and a

proviso requires that any differences

in treatment not be "the result of an

intention to discriminate because of

race . . . " 45 U.S.L.W. at 4513.

The issue then is whether, on this record, this Court may

13/

13/ That discriminatory purpose is a necessary element of

proof in cases involving seniority systems that have

discriminatory consequences was made plain in Hardison,

supra:

Thus absent a discriminatory purpose the

operation of a seniority system cannot be

an unlawful employment practice even if the

system has some discriminatory consequences.

45 U.S.L.W. at 4677.

And in a footnote, Justice White wrote:

Here . . . the operation of the seniority

system itself is said to violate Title VII.

In such circumstances §703 (h)- unequivocally

mandates that there is no statutory violation

in the absence of a showing of discriminatory

purpose. 45 U.S.L.W. at 4677, n.13.

16

conclude that the seniority system was designed, negotiated

and maintained free of any racially discriminatory purpose.

The answer is self evidently and emphatically "NO".

Any seniority system, including the seniority

system under attack here, is the result of many considera

tions. Among the purposes of the seniority system in this

case was the establishment of a method for the allocation

of jobs among competing employees for purposes of promotions,

demotions, layoffs, vacation preferences and overtime

(A. 411). Here, jobs were allocated, pursuant to the

seniority system, on a strictly racial basis. Thus, blacks

were isolated from the beginning in an inferior laborer caste,

while the seniority system assured that newly hired white workers

would begin their industrial careers ahead of blacks, that

they would not be required to work as laborers, and that

they would not work under the supervision of blacks. The

maintenance of a permanent underclass of blacks, although

not the only purpose of the seniority system, was clearly

one of its aims, and is more than enough to make it invalid

under §703(h). For §703(h) does not require or even

contemplate that racial discrimination be the sole purpose

underlying the establishment of the seniority system.

From the face of §703(h) itself, it is apparent

17

that where race was a factor that entered into the

establishment of the seniority system, that seniority

system is not "bona fide" and therefore is not protected.

Likewise where race was a factor in the negotiation or

maintenance of the seniority system, that seniority is

not entitled to the limited protection afforded by

§703(h). See Teamsters, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4515. See

also Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Corp.. ___U.S.___, 50 L. Ed. 2d 450, 464 (1977).

While in Teamsters, supra, Evans, supra and

Hardison, supra, the Supreme Court had no occasion to

decide whether a seniority system which was established,

negotiated or maintained at least in part to deprive

minorities or women of the opportunity to compete with

white males on an equal basis, and which presently requires

M /difference in treatment, is insulated by §703(h), those

15/

cases do address this distinction.

14/ None of those cases involved any claim or showing that

discriminatory purpose entered into the establishment,

negotiation or maintenance of the seniority system. See

Teamsters, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4514; Evans. supra, 45

U.S.L.W. at 4677.

15/ In a rare instance of agreement, the dissent and the

majority concluded that the Quarles, supra line of cases

survive the Supreme Court's May 31, 1977 decision. See

Teamsters. supra. 45 U.S.L.W. 4520, n.3.

18

In Teamsters, supra, the Supreme Court

distinguished cases such as Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc.,

279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968); Local 189, United

Paperworkers v. United States, supra; United States v.

Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969)

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652 (2nd

Cir. 1971); and United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co.,

471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972), from the case before-it

because an intention to discriminate entered into the

very adoption of the seniority systems involved in those

cases. See 45 U.S.L.W. at 4511, n.28. Those cases now

stand for the proposition that, where the seniority system

is shown to have had a discriminatory purpose, it cannot

be "bona fide" and is not entitled to the limited immunity

accorded by 703(h). See 45 U.S.L.W. 4511. Such a

seniority system thus falls under the Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) rationale, see Teamsters,

supra, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4512, and if it has the present

effect of perpetuating pre-Act discrimination, it must

19

yield. See Teamsters, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. 4511 n.28.

Mr. Justice Stevens likewise distinguished the holding in

Evans, supra, from the Quarles, supra, line of cases. See

Evans, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. 4567, n.10. Because Ms. Evans

claimed continuing effect only, the Court had no occasion

to go beyond the limitation imposed by §703 (h). The

import of Evans, supra for this case is that where the

seniority system is shown to be not "bona fide", the

continuing effects of that seniority system become

important. See Evans, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. 4567.

The foregoing construction of 703(h) is required

by long-established principles of statutory construction:

. . . [R]emedial legislation . . .

16/

16/ In this regard the unions read much into the statement

of the Court in Teamsters that none of the identifiable

victims of discrimination in that case are entitled to

retroactive seniority pre-dating July 2, 1965. (See Unions -

11). That statement which appears at Part III of the Court's

opinion was made in connection with its holding that the

seniority system was immune under §703 (h). The Court was

not addressing the issue of remedy in a case such as this

where the seniority system is not entitled to the immunity

accorded by §703(h). Where purpose is shown "a seniority

system that perpetuates the effects of the pre-Act discrimina

tion cannot be bona fide . . . " Teamsters, supra, 45 U.S.L.W.

at 4511, n.28 (emphasis added). In such cases only full

plant seniority can effect the remedy that "informs" the twin

purposes of Title VII. See Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

supra.

20

should therefore be given a

liberal interpretation; but

for the same reason, exemptions

from its sweep should be

narrowed and limited to effect

the remedy intended. Piedmont

& N.R. Co. v. Interstate Commerce

Commission, 286 U.S. 299, 311-12

(1932).

See also Interstate Natural Gas Co. V. Federal Power

Commission, 156 F.2d 949 (5th Cir. 1946), aff'd. 331

U.S. 682 (1947); Cf. Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber

Co., 491 F.2d 1364, 1377 (5th Cir. 1974). In Teamsters,

supra, Mr. Justice Steward reminds us of the "remedy

intended" by the enactment of Title VII:

The purpose of Title VII was 'to

assure equality of employment

opportunities and to eliminate

those discriminatory practices

and devices which have fostered

racially stratified job environments

to the disadvantage of minority

citizens1 . . . To achieve this

purpose, Congress 'proscribe[d]

not only overt discrimination but

also practices that are fair in

form, but discriminatory in operation'

. . . Thus, the Court has

21

repeatedly held that a prima facie

Title VII violation may be established

by policies that are neutral on their

face and in intent but that nonetheless

discriminate in effect against a

particular group . . . (citations omitted).

45 U.S.L.W. at 4512.

The Supreme Court's decision, consistent with these

principles of statutory construction, gives only limited

effect to §703(h). Only those seniority systems that were

not established, negotiated or maintained with an intention

to discriminate are immune.

In this, as in any case involving racial

discrimination, proof of overt discrimination is seldom

direct. See United States v, Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971). Usually proof of purposeful

discrimination must be inferred from the totality of the

circumstances. See Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Corp., supra, 50 L. Ed. 2d at 465

(hereinafter referred to as "Arlington Heights").

"Frequently the most probative evidence of intent will be

objective evidence of what actually happened rather than

evidence describing the state of mind of the actor. For

22

normally the actor is presumed to have intended the

natural consequences of his deeds". Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229, 253 (1976) (Stevens, J. concurring). Thus,

the impact of the challenged conduct where it bears more

heavily on one race than another is highly relevant

evidence of discriminatory intent. See Arlington Heights,

supra, 50 L. Ed. 2d at 465. Further, evidence of a

historical pattern of discrimination will support the

inference that discrimination continued into the present,

particularly if the relevant aspects of the decision-making

process has undergone little change. See Hazelwood School

District v. United States, ___U.S.___, 45 U.S.L.W. 4883,

4885, n.15. (June 28, 1977).

2. The Seniority System In This Case Is

Tainted With Discriminatory Purpose

In this case, it is readily apparent that the

unions' original discriminatory design continued into

the present: the challenged conduct bore more heavily

on blacks than on whites, and there was no change in the

decision-making process until 1970, and little change

until 1972. Thus, this case is fundamentally different

from Teamsters, supra and Evans, supra. It is like the

23

"so-called departmental seniority cases", see Evans,

supra, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4567, n.10, that involve

segregated unions, segregated departments or segregated

jobs within departments that have been artificially and

discriminatorily divided by means of racially defined

seniority units. As noted above, neither Teamsters,

supra nor Evans, supra involved a claim that the seniority

system itself was intentionally discriminatory in its

origins or maintenance. For example in Teamsters, supra,

the Government "conceded that the seniority system did not

have its genesis in discrimination and that it was negotiated

and has been maintained free of any illegal purpose".

45 U.S.L.W. at 4514. Thus, while the seniority system at

issue there had the "effect" of discriminating against

blacks, the other necessary element of proof, to wit:

"genesis in discrimination" or negotiation or maintenance

of collective bargaining agreements that are infected with

a racially discriminatory purpose, was not present. See 45

U.S.L.W. at 4514. Here racial discrimination entered the

"very adoption" of the seniority system. See pp. 6-10.

supra.

24

In Teamsters, distinct racially integrated

bargaining units covered all city drivers and serviceman jobs.

See 45 U.S.L.W. at 4507, n.3. Here separate racially

segregated bargaining units were established to represent

employees along racial rather than departmental lines.

See pp. 6-10, supra. In Teamsters, supra more whites than

blacks held the arguably less desirable city driver and

serviceman jobs. 45 U.S.L.W. at 4514. Here no whites

held the undesirable jobs. City drivers' jobs in Teamsters,

supra had features which made such jobs as desirable, for

some, as line driver jobs. 45 U.S.L.W. at 4517. Here no

one contends that the black jobs at Gilman were more

desirable than the white jobs. As a result, the lock-in12/

effect of the seniority system falls on blacks only and

17/ The unions appeared to recognize that the long standing

impact of their collective bargaining agreements fell

heavier on blacks when in 1972, they readily agreed to

seniority reform which was designed to remedy the effects

of past discrimination.

25

from this fact the Court is entitled to infer an intent

to discriminate on the basis of race.

3. In This Case The Unions Are Liable

The Supreme Court's ruling that the

Teamsters did not violate Title VII by agreeing to and

maintaining the seniority system is premised on its

finding that the seniority system was protected by

§703(h). See 45 U.S.L.W. at 4512. Here the unions

cannot escape liability because the seniority system

which they together with Gilman established, negotiated

and maintained was the result of an intention to

discriminate. Both intent and effect is present in

this case. Since the seniority system is not "bona

fide", the unions are responsible for their violation

of Title VII.

B. Plaintiffs' Claims Under 42 U.S.C. §1981

Should Not Be Dismissed

In Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc.,

421 U.S. 454 (1975), the Supreme Court held:

that the remedies available under

Title VII and §1981, although related,

and though directed to most of the same

ends, are separate, distinct and

independent. 421 U.S. at 461.

26

The Court observed that in some respects §1981 offers

more relief than Title VII, and in other respects less.

See 421 U.S. at 458-461. The Court did not, however,

have occasion to decide whether §1981 prohibits certain

kinds of racial discrimination that do not constitute

violations of Title VII. Neither, for that matter, has

this Court had occasion to decide the question. See

Watkins v. United Steelworkers. Local 2369. 516 F.2d 41

(1975).

In their petition for rehearing, the unions

argue that this Court should hold, on the basis of the

three Supreme Court decisions discussed supra, none of

which involved §1981, that plaintiffs' §1981 claims

should be dismissed. For at least two reasons, that

argument has no merit.

First, as we have shown above, the seniority-

system is not a "bona fide" one and thus is subject to

reform under Title VII. Accordingly, there is no need

to reach the §1981 issues. Second, although plaintiffs

originally brought this as a §1981 action, both the coi’-

below and this Court decided only the Title VTT

27

Thus, while the §1981 claim is still viable, the

serious - albeit at this point irrelevant - questions

raised by the unions with respect to the §1981 issues

should be decided in the first instance by the trial court.

IV.

THE IBEW IS LIABLE IN THIS CASE

In a separately filed petition, the International

Brotherhood of Electrical Workers seek "vacation of

this Court's Judgment and Opinion entered on January 3, 1977,

as they pertain to the IBEW, and for reversal of the district

court's ruling as to the liability of the IBEW". (IBEW

Pet.-l). The issues raised by this petition are not new.

These issues either have been raised by the other unions

18/

in their petition for rehearing or have been raised and

19/

disposed of in the original appeal of this action. If

18/ See numbered items 2 and 7 in IBEW Petition.

19/ See numbered items 1, 3, and 4 in IBEW Petition.

28

anything, the Supreme Court's opinion in Teamsters,

supra, reinforces the determination of this Court that

IBEW is jointly responsible for the discrimination

suffered by the plaintiffs and the class.

As we have shown above, the seniority system

in this case had its genesis in discrimination. See

pp. 6-9, supra. It is reasonable to assume that it was

the IBEW that undertook to organize employees in the

Electrical Department, the Powerhouse and the Instrument

Department. It is clear that none of the black jobs in

those departments were included in the Local 741

bargaining unit. It is unlikely that this newly chartered

local without the assistance of the IBEW determined the

parameters of its jurisdiction or that Local 741 negotiated

the earliest contracts establishing the promotional scheme

within the bargaining unit. If, as is likely, the IBEW

was responsible for the creation of the segregated local

or participated in the early contract negotiations, the

requisite element of intent is present and the IBEW cannot

now disclaim responsibility. Since the record on this issue

20/ In their original Brief in this Court, the IBEW points

out that the seniority system that was in use in 1970 had

been in use since the plant opened (IBEW-11). It would be

startling if the IBEW had nothing to do with it at anytime

since 1941.

29

is not fully developed, remand may be appropriate.

Upon remand for this limited issue, however,

it should be noted that, since it is IBEW that is claiming,

under an exception to the Act, that it escapes the Act's

reach, it is that Union which has the burden of proving

that it comes within the exception. United States v.

First City National Bank. 386 U.S. 361, 366 (1967).

Further, such proof should be by objective evidence of

what actually happened rather than evidence describing the

state of mind of the IBEW at the time it chartered Local 741

and thereafter. See Washington v. Davis, supra, 426 U.S.

253 (Mr. Justice Stevens, concurring). Until these

standards are met, the decisions of the district court

holding IBEW liable and of this Court affirming it should

stand undisturbed.

CONCLUSION

In this case, the Court returns again to legal

arguments addressed to the meaning of certain statutory

30

provisions:

But beneath the legal facade a faint

hope is discernible rising like a

distant star over a swamp of uncertainty

and perhaps despair. . . . Even the most

tedious physical labor is endurable and

in a sense enjoyable . . . when the

laborer knows that his work will be

appreciated and his progress rewarded

. . . . The ethic that permeates the

American dream is that a person may

advance as far as his talents and his

merit will take him. And it is

unthinkable that a citizen of this

great country should be relegated to

unremitting toil with never a glimmer

of light in the midnight of it all.

Miller v. International Paper Co.,

408 F .2d 283, 294 (5th Cir. 1969).

Plaintiffs have shown that the Supreme Court's May 31, 1977

and June 16, 1977 decisions do not alter the result in

this case. Those cases merely hold that §703 (h) provides

a narrow, limited exception for neutral seniority systems

which may have the effect of discriminating but which

themselves are in no way tainted by a discriminatory

purpose. In this case, given the fully developed record

on the Title VII issue, this Court should reaffirm its

January 3, 1977 decision holding the unions liable for

their unlawful conduct. The only issue under Title VII

that may require remand is that addressed to the liability

31

of the IBEW. There the only issue that remains to be

resolved is whether or not its Local 741 is solely

liable for the establishment of a racially exclusionary

bargaining unit and the negotiation and maintenance of

discriminatory collective bargaining units from 1941

until at least August, 1972.

If the Court determines that remand is warranted

as to all of the unions, plaintiffs respectfully urge

that this Court provide the district court with instructions

as to the proper application of the Supreme Court decisions

discussed, supra so that this case can come to rest without

the need for another lengthy appeal. If, as is perfectly

clear on the present state of the record, the district

court finds that the seniority system was tainted by a

prohibited purpose, a finding of union liability under

Title VII follows. That purpose can be inferred from

evidence of what actually happened. Where, as is true

here, that seniority system has not been reformed to

fully eradicate its effects as of the time of the filing

of the charge of discrimination with the Equal Employment

32

Opportunity Commission, the unions are liable.

See Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co.. 433

F.2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970).

Of Counsel:

RICHARD SEYMOUR

ELIZABETH RINDSKOPF

520 Woodward Bldg.

733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

MORRIS J. BALLER

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, Calif.

94103

Respectfully submitted,

FLETCHER FARRINGTON

P.O. Box 9378

Savannah, Georgia 31402

__________________- -

O. PETER SHERWOOD

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A. BLENN TAYLOR

Taylor, Bishop & Lee

P.O. Box 1596

Brunswick, Georgia 31520

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that, on the Fourth day of July, 1977,

copies of the foregoing Response of Plaintiffs-ftppelles to

the Unions’ Petitions for Rehearing were mailed to the follow

ing counsel for the parties herein:

MICHAEL H. GOTTESMAN

FRANK PETRAMALO, JR•Bredhoff, Cushman, Gottesman

& Cohen1000 Connecticut Avenue N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

BENJAMIN WYLE

Spivak & Wylie

3 East 54th Street

New York, New York 10022

j. R. GOLDTHWAITE, JR.Adair, Goldthwaite, Stanford

& Daniel600 Rhodes-Haverty Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

JEROME A. COOPER JOHN FALKENBERRYCooper, Mitch & Crawford

409 N. 21st Street Birmingham, Alabama 35203

ELIHU LEIFER1125 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

GUY O. FARMER, IIMahoney, Hadlow & Adams

P.0. Box 4009Jacksonville,

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees