United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corporation Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae in Exception to "Recommended Findings and Proposed Decision" of Panel

Public Court Documents

January 21, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corporation Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae in Exception to "Recommended Findings and Proposed Decision" of Panel, 1971. 8be69dcc-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/26d11878-07b4-41b8-bc8b-b68b44527dca/united-states-v-bethlehem-steel-corporation-brief-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-as-amicus-curiae-in-exception-to-recommended-findings-and-proposed-decision-of-panel. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

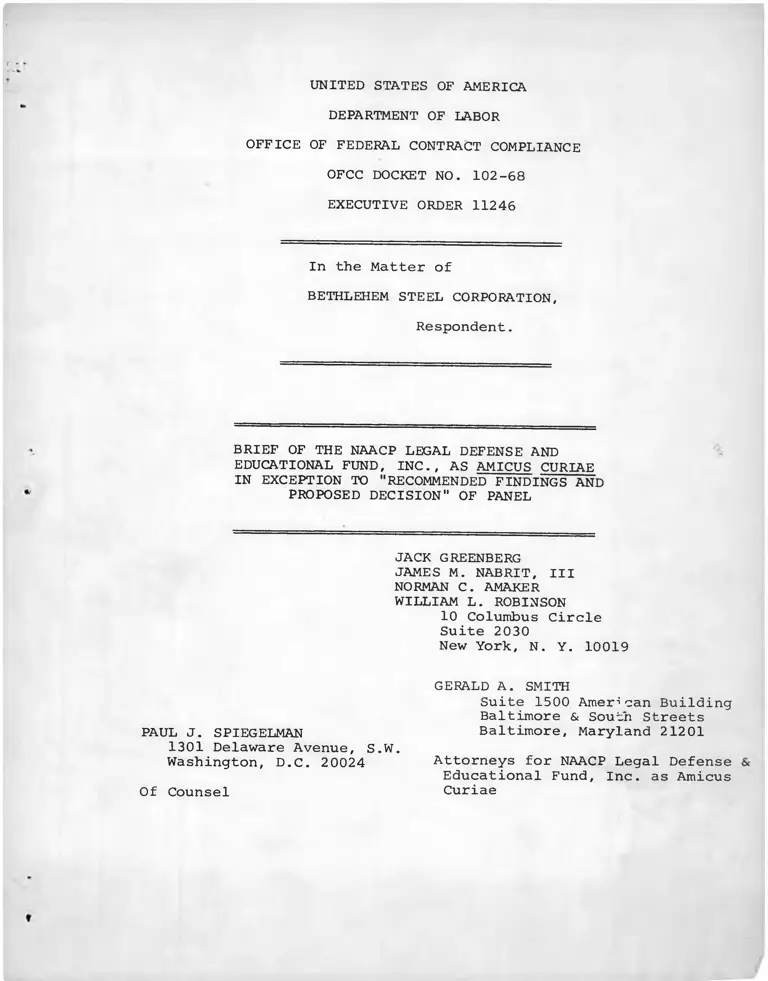

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

OFFICE OF FEDERAL CONTRACT COMPLIANCE

OFCC DOCKET NO. 102-68

EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246

In the Matter of

BETHLEHEM STEEL CORPORATION,

Respondent.

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN EXCEPTION TO "RECOMMENDED FINDINGS AND PROPOSED DECISION" OF PANEL

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III NORMAN C. AMAKER

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

PAUL J. SPIEGELMAN

1301 Delaware Avenue, S.W.

Washington, D.C. 20024

10 Columbus Circle Suite 2030

New York, N. Y. 10019

GERALD A. SMITH

Suite 1500 American Building Baltimore & South Streets

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Attorneys for NAACP Legal Defense

Educational Fund, Inc. as Amicus CuriaeOf Counsel

INDEX

Page

AMICUS BRIEF IN EXCEPTION TO "RECOMMENDED

FINDINGS AND PROPOSED DECISION" OF PANEL--------------- 1

FACTS OF DISCRIMINATION----------------------------------- 10

A. Evidence of Blatant Discrimination--------------- 10

B. Present Effects of Past Discrimination----------- 11

ARGUMENT

I. THE HEARING AFFORDED BETHLEHEM ONLY

CONCERNS THE ISSUE OF WHETHER OR NOT

BETHLEHEM WAS IN COMPLIANCE WITH ITS

CONTRACTUAL OBLIGATIONS-------------------------- 15

II. UNDER ANY THEORY OF THE CASE, BETHLEHEM'S

DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES, COUPLED WITH ITS

ADAMANT REFUSAL TO CONCILIATE REQUIRE THE

DEBARMENT REMEDY--------------------------------- 21

A. The Constitution Requires that Bethlehem

Be Debarred------------------------------- 21

B. Proper Interpretation of Executive Order

11246 Requires That Bethlehem be

Debarred---------------------------------- 2 3

C. Even Assuming That It Was Appropriate for

Panel to Conduct a Trial-type Hearing on

All Issues, the Record Requires That

Bethlehem Be Debarred------------------------ 2 7

1. A Proper Interpretation of the BusinessNecessity Defense Requires Debarment----- 27

2. Even Under Panel's Interpretation of

Business Necessity the Evidence Failed

to Establish This Defense---------------- 35

D. Even if the Business Necessity Test Is

Established, Bethlehem's Failure or

Refusal to Comply with OFCC Guidelines

Violated Its Affirmative Action Obliga

tions---------------------------------------- 28

i

Page

III. THE REMEDY RECOMMENDED BY BETHLEHEM AND

BY THE PANEL VIOLATES EXECUTIVE ORDER

11246--------------- 41

IV. THE POSITIONS TAKEN BY THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, THE SOLICITOR OF LABOR, AND THE

OFCC ARE BINDING ON THE SECRETARY OF LABOR

AND REQUIRE THAT BETHLEHEM BE DEBARRED------ 44

CONCLUSION----------------------------------------------- 46

l i

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

OFFICE OF FEDERAL CONTRACT COMPLIANCE

OFCC DOCKET NO. 102-68

EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246

In the Matter of

BETHLEHEM STEEL CORPORATION

Respondent.

AMICUS BRIEF IN EXCEPTION TO "RECOMMENDED

FINDINGS AND PROPOSED DECISION" OF PANEL

This is an amicus brief in exception to the "Recommended

Findings and Proposed Decision of Panel" in debarment proceed

ings initiated on May 23, 1968 by the Labor Department's Office

of Federal Contract Compliance (OFCC) against Bethlehem Steel

Corporation for its adamant refusal to comply with the equal

employment opoortunity practices required of all contractors

who do business with the federal government. It is submitted

in accordance with your invitation to do so contained in your

letter of December 18e 1970.

We vigorously except to the proposed decision of the

Panel's two-to-one majority, which, after agreeing with the

overwhelming evidence of blatant and consistent racial dis

crimination on the part of Bethlehem continuing over a period

of many years, then goes on to do mental handsprings in order

to arrive at its recommendation that you place the full weight

of your authority as Secretary of Labor in support of

Behtlehem's discriminatory policies. We submit that the panel's

recommendations in this regard are in direct conflict with

the applicable legal decisions governing the matters at issue,

the findings made by the dissenting member of the panel, the

1_/position on these issues taken by the Attorney General, and the

manifest weight of the evidence presented to the panel. We

further except to the Panel's unsupportable assertion that -

Bethlehem — a company whose discriminatory policies have

already been publicly exposed in litigation in the United

2_/States District Court for the Western District of New York;

1 / See United States v. Bethlehem Steel c o m (Lackawanna

Plant) 312 F.Supp. 977 (W.D. N.Y. 1970) Appeal noticed.

No. 35183 (2nd Cir. June 12, 1970).

2 / Ibid

2

whose very practices in this case are being attacked by the

Attorney General as violative of Title VII of the Civil Riqhts

3_/Act of 1964; who has conceded in these proceedings that it did,

as matter of company housing policy, discriminate against

blacks on the basis of race; and whose contentions, dilatory

and unproductive conduct in these proceedings are evidence of

its intention to continue discriminating until forced to stop,

rather than the willingness to take the "affirmative action"

to prevent discrimination required by law — "is not . . . a

company which is presently engaged in patterns of blatant dis

crimination or which attempts to justify such patterns." Panel

Report p. 13 H32. We further except to any implication either

in the appointment of a panel of professional arbitrators for

these proceedings by the Secretary of Labor under the previous

administration or in the mediation efforts conducted under the

supervision of this panel, that the Secretary of Labor wishes

to undermine the authority conferred on him by Executive Order

11246 and delegated by him to the Director of the Office of

Federal Contract Compliance to enforce equal employment

opportunity in government contracts; the notion that law en

forcement officials of the United States Government should be

forced to mediate with recalcitrant violators seem to us

absurd and unconstitutional.

3 / The District Court in the Lackawanna case agreed that

Bethlehem was discriminating by use of its unit seniority system.

The relief granted by the court was more limited than requested

by the Attorney General and he is therefore now appealing.

3

whose very practices in this case are being attacked by the

Attorney General as violative of Title VII of the Civil Riqhts

3_yAct of 1964; who has conceded in these proceedings that it did,

as matter of company housing policy, discriminate against

blacks on the basis of race; and whose contentions, dilatory

and unproductive conduct in these proceedings are evidence of

its intention to continue discriminating until forced to stop,

rather than the willingness to take the "affirmative action"

to prevent discrimination required by law — "is not . . . a

company which is presently engaged in patterns of blatant dis

crimination or which attempts to justify such patterns." Panel

Report p. 13 H32. We further except to any implication either

in the appointment of a panel of professional arbitrators for

these proceedings by the Secretary of Labor under the previous

administration or in the mediation efforts conducted under the

supervision of this panel, that the Secretary of Labor wishes

to undermine the authority conferred on him by Executive Order

11246 and delegated by him to the Director of the Office of

Federal Contract Compliance to enforce equal employment

opportunity in government contracts; the notion that law en

forcement officials of the United States Government should be

forced to mediate with recalcitrant violators seem to us

absurd and unconstitutional.

3 / The District Court in the Lackawanna case agreed that

Bethlehem was discriminating by use of its unit seniority system.

The relief granted by the court was more limited than requested

by the Attorney General and he is therefore now appealing.

3

Mr. Secretary, as amicus curiae, we wish to advise you

of our conviction that your action on this case has the most

far-reaching implications for the whole future and credibility

of federal contract compliance efforts. A decision to adopt

the unsupportable recommendations of the panel would be in

defensible on the facts of this case and a clear signal to

every federal contractor that, as far as the Secretary of Labor

is concerned, such contractors can engage in discriminatory

practices so long as they defend their illegal practices with

sufficient vigor (through no legal justification). Moreover,

failure to accept both the authoritative weight of the position

taken by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance and to re

affirm the authority of the Director of OFCC in compliance

matters would destroy his credibility and thereby hamstring

OFCC efforts to enforce the law.

For the reasons set forth more fully below, we respectfully

urge you to reject the recommendations of the panel majority,

and adopt those of the OFCC, the agency with the responsibility

for and expertise in enforcement of equal opportunity com

pliance by federal contractors.

History of Proceedings

At the outset it should be understood that the fact

formal proceedings were necessary at all in this case results

4

Mr. Secretary, as amicus curiae. we wish to advise you

of our conviction that your action on this case has the most

far-reaching implications for the whole future and credibility

of federal contract compliance efforts. A decision to adopt

the unsupportable recommendations of the panel would be in

defensible on the facts of this case and a clear signal to

every federal contractor that, as far as the Secretary of Labor

is concerned, such contractors can engage in discriminatory

practices so long as they defend their illegal practices with

sufficient vigor (through no legal justification). Moreover,

failure to accept both the authoritative weight of the position

taken by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance and to re

affirm the authority of the Director of OFCC in compliance

matters would destroy his credibility and thereby hamstring

OFCC efforts to enforce the law.

For the reasons set forth more fully below, we respectfully

urge you to reject the recommendations of the panel majority,

and adopt those of the OFCC, the agency with the responsibility

for and expertise in enforcement of equal opportunity com

pliance by federal contractors.

History of Proceedings

At the outset it should be understood that the fact

formal proceedings were necessary at all in this case results

4

from the refusal by Bethlehem to agree to follow those practices

which OFCC has deemed minimal acceptable standards of equal

employment opportunity. Having become informed of Bethlehem's

discriminatory practices, on May 29, 1967, the OFCC notified

Bethlehem that it was in violation of its contractual agree

ment under the equal opportunity clause of its contracts with

±Jthe government. This was the first step in the tortuous pro

cess of attempting to get Bethlehem to live up to its agree

ments with the government; nearly four years have passed since

this initial step and Bethlehem has still refused to meet its

obligations under the equal opportunity clause of its govern

ment contracts.

After a full investigation of Bethlehem's operations at

its Sparrows Point facilities, OFCC uncovered the following

discriminatory practices on the part of Bethlehem:

4 / This clause, required by Executive Order 11246 to be included in all government contracts, provides as follows:

"The contractor will not discriminate against any

employee or applicant for employment because of

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin."

Executive Order 11246 also requires inclusion of an affirmative action clause:

"The contractor will take affirmative action to ensure that

applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin. Such action shall

include, but not be limited to the following: employ

ment, upgrading, demotion, or transfer; recruitment or

recruitment advertising; layoff or termination; rates

of pay or other forms of compensation; and selection

for training, including apprenticeship."

5

(1) excluding Negroes from administrative

and executive positions and super

visory positions above the first line;

(2) discriminating in the selection of

first-line supervisors and limiting Negro supervisors to racially segre

gated units, and failing to take affirm

ative action to cure the effects of dis

criminatory practices in selection and

assignment of supervisors;

(3) assigning Negroes on a racially discriminatory basis to those departments,

units and jobs in which the working con

ditions are the least desirable, the pay

is lowest, and the opportunity for advance

ment is smallest, and continuing to limit

the transfer opportunities of Negro em

ployees from these segregated departments

and units, failing to take affirmative

action to cure the effects of discrimina

tory assignment practices;

(4) requiring Negro workers to meet higher

standards for placement in certain depart

ments, units and jobs than incumbent white

employees were required to meet;

(5) failing to take necessary affirmative

action to cure the effects of previous

discriminatory practices in the operation

of training programs; and

(6) failing to take necessary affirmative

action to cure the effects of previous discriminatory hiring practices in regard

to clerical, professional, technical and

other white collar employees.^'

5 / Letter of 5/16/68 from Edward C* Sylvester, Jr., Director

of OFCG,to Stewart S. Cort, President of Bethlehem Steel Corp.

In addition, Bethlehem was later charged with discrimination in

housing. In negotiations with OFCC, Bethlehem conceded that its company housing was segregated on the basis of race and agreed

to OFCC requirements that affirmative steps to desegregate

be taken.

6

OFCC attempted to assist Bethlehem and gain voluntary

compliance in conciliation meetings with the Company repre

sentatives on February 12-14, 1968, March 7, 1968, April 24-25,

1968, and May 7, 1968, but Bethlehem refused to satisfy the

OFCC that it would comply with its equal employment opportunity

obligation with respect to any of these six issues. Accordingly,

on May 16, 1968, the Director of OFCC informed Bethlehem of

his intention to terminate all existing government contracts

with Bethlehem and to recommend that the Department of Justice

take appropriate action to enforce the company's contractual

obligations. As was its right under the applicable regulations,

Bethlehem requested a hearing on the charges. The Acting

Director of OFCC then, on August 2, 1968, served Bethlehem

with a formal "Notice of Hearing" which (1) set forth the

specific charges against Bethlehem; (2) announced that a panel

consisting of Messrs. Hanley (chairman). Bailer and Seitz,

had been appointed by the Secretary of Labor to hear and

determine the charges against Bethlehem and to recommend to

the Director what action he should take with respect to con

tracts with Bethlehem; and (3) include as an attachment "Rules

6_/ These were essentially the same as those described

in footnote 5 and accompanying text.

7

of Procedure" for the proceeding. In accordance with these

procedures, Bethlehem filed an answer on August 26, 1968

denying all charges of discrimination and setting forth twenty-

five "affirmative defenses" to the charges. Then, reacting with

Pavlovian predictibility, at the sound of the bell opening the

litigation, counsel for Bethlehem spewed forth a barrage of

verbiage in the form of motions and memoranda whose purpose

and effect were described by the government in its motion to

cite Bethlehem for contempt as "dilatory tactics" and "con

tinuing efforts to obstruct the orderly and timely presentation"

of the case to the panel. These efforts were successful in

delaying the start of hearings on the merits from the scheduled

date of September 9, 1968 to October 21, 1968. After three

days of hearings in October 1968, the panel adjourned for four

months; resumed hearings again in February 1968 for five days;

scheduled additional hearings for April 1968, but then postponed

these hearings until November 1969 when they were finally con

cluded so that the panel chairman could "mediate" the dispute.

The panel gave the parties until February 16, 1970 to file pro

posed findings of fact and conclusions of law and not until

December 18, 1979, over three and one-half years after the

original action taken on these matters by OFCC and almost two

and one-half years after the panel was appointed, were the panel's

"Recommended Findings" forwarded to the Secreatry of Labor.

In its findings, the Panel unanimously concluded that Bethlehem

8

was guilty of racial discrimination and that the unit seniority

system to which Bethlehem and the United Steel Workers had

agreed and which was currently in force at the Sparrows Point

plant perpetuated the effects of this past discrimination.

Despite the fact that there was overwhelming evidence in the

record of segregation and discrimination against blacks on the

part of Bethlehem (including a stipulation by Bethlehem whose

necessary implication was that Bethlehem had maintained

segregated company-owned housing), the panel's two-to-one

majority viewed Bethlehem as "not a company which is presently

engaged in patterns of blatant discrimination" — apparently

agreeing with Bethlehem that lily white means angel pure.

In any case, based on the general assertions of em

ployee-witnesses for Bethlehem and the United Steel Workers

Union (which had been allowed to intervene in the proceeding)

that the remedies requested by the government — abolition

of unit seniority in favor of prospective plant-wide seniority

and rate retention for victims of prior discrimination if they

chose to transfer — would adversely affect (white) employee

morale and undermine the equal-pay-for-equal-work "cornerstone

of labor-management bargaining in the steel industry, the two-

to-one majority found that application of these remedies was in

its view "unworkable" in the circumstances of this case. This

latter conclusion was reached by disregarding the OFCC position

which the panel recognized had "a substantial basis in judicial

9

precedent and reason" and which "plainly [fell] within the

scope of . . . its authority," the cogent views of the dissenting

panel member; and the testimony of Dr. Richard Rowan, a

nationally recognized expert in minority employment in the

steel industry, that the plan was in fact workable.

FACTS OF DISCRIMINATION

A . Evidence of Blatant Discrimination

The panel unanimously found that Bethlehem followed

“a predetermined hiring and assignment practice of placing

Negroes, because of race, into inferior jobs and units and of

excluding them from jobs, units, and employment opportunities

which were reserved for white employees only." (Panel Report

p. 42 1155) . This conclusion was based on overwhelming

statistical and testimonial proof, uncontradicted by Bethlehem;

thus there can be no arguing with the Panel's finding in this

7 / .regard. The proof supporting its conclusion consists of

statistical evidence which established that 'a total of 6,436

Negro blue collar workers out of 7,864 Negro workers, or 81%

were assigned to all-Negro or predominantly Negro departments

and units; and of 12,602 white employees, 8,385 or 66% were

7 / This evidence is summarized in the Panel's Report at

pp. 40 to 43 and more fully in the Government's Proposed:

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law at pp. 40 to 82.

10

assigned to all-white or predominantly white departments and

units where only 831 or 10% of the Negroes were assigned."

(Panel Report.p. 40-41 H51). The average job class for black

employees was 5.47 while the average job class of whites was

9.62; the pay of the average black employee ranged from 13%

to 20% less chan the average white, depending on length of

service. (See Gov't. Proposed Findings at pp„ 47-54).

This statistical evidence was buttressed by testimonial

evidence of the shocking practices followed as a matter of

course by Bethlehem. Testimony in the record established

that, in addition to hiring and assinging on the basis of race,

Bethlehem segregated its company-owned housing, segregated its

locker rooms, lied to black employees seeking information on

transfer and employed personnel supervisors who referred to

blacks as "Niggers". All of this testimony was uncontradicted

by Bethlehem which never at any time sought to give any

explanation for its blatantly discriminatory conduct of business.

B . Present Effects of Past Discrimination

The panel has unanimously found that the effect of the

pattern of exploitation, humiliation, and degradation of

Bethlehem's black workers has been the segregation of black

workers into the hottest, dirtiest,lowest paying, and generally

least desirable jobs at Bethlehem's plants (Panel Report

p. 42 H55). It also recognized that the unit seniority system

11

currently in use by Bethlehem is the principal mechanism by

which the prior discriminatory segregation of blacks into

the worst, lowest paying jobs is perpetuated (Panel Report

at p. 42 559-61). Under the unit seniority system,promotion,

demotion, and lay-off are decided primarily upon the basis

of length of service in a particular job category rather than

length of service in the plant. On its face, such a system

does not appear discriminatory on the basis of race, but

when it is realized that the job categories were, in effect,

divided up into black jobs and white jobs, it becomes clear

that, as the Panel unanimously found, the unit seniority

system operates to maintain segregated, discriminatory job

assignments because a black entering the plant could advance

only up a black ladder of progression and a white could only

advance up a white ladder. So long as original job assign

ments remain discriminatory, the unit seniority serves to lock

blacks into inferior job opportunities by placing them on

ladders of progression which never seem to rise out of the

coke ovens. Because of its so-called "Affirmative Action"

program and the Conciliation Agreement entered into by

Bethlehem, the Company's position was that by no longer dis

criminating in original assignment, it was no longer dis

criminating at all. Even the panel recognized this argument

for the nonsense it is. All of the people who were dis-

12

criminated against in past assignments and have advanced up

black ladders of progression are locked into these positions

by the operation of the unit seniority system.

In order to illustrate the operation of this system,

let us take the example of a black who entered Bethlehem's

Sparrow's Point plant ten years ago and was, solely because

of his race assigned to a menial, low-paying job near the coke

ovens and who, by dint of ten years of conscientious work has

managed to advance to a less menial, higher paying job near

the coke ovens. He must, if he wishes to get off his dead-end

job, give up the benefits which he has accrued over ten years

of continuous service and begin at the very bottom of a pro

gression ladder which admittedly leads eventually to a higher

horizon, or at least out of the coke ovens. In other works,

in order to gain entry to a jcb with full employment opportunity

one which he has been denied for the past ten years solely

because of his race — he must now give up the raises in pay,

the promotion and demotion rights, and the job security which

he has earned because of ten years continuous service and

begin again as if this were the first day he had ever walked

8Vinto the plant. It is authoritatively settled by case law

8 / At least with respect to pay, pormotion, and bumpoff;

his bump-back rights make his position slightly better than

a brand-new employee.

13

and accepted by the panel that to place such barriers in the

way of the victim of past discrimination constitutes dis

crimination which violates both Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and the equal employment opportunity clause entered

into by Bethlehem (as well as all other contractors with the

_9/

government) pursuant to Executive Order 11246. In short ̂^

perpetuating past discrimination is present discrimination.

In order to remedy this discriminatory evil, the OFCC

took the position, both in attempting to gain voluntary com

pliance from Bethlehem and before the panel, that the equal

opportunity and affirmative action clauses of Bethlehem's

contract with the government required the Company to remove

the discriminatory barriers by allowing the victims of past

discrimination:

(1) to compete for future job openings on

the basis of their length of service

in the plant;

(2) to transfer to future job openings at

the bottom of the formerly white seniority ladders without having to

give up the pay raises they have earned

for the years they have been employed.

9 / bocal 189. United Papermakers and Paper Workers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969) cert denied.

397 U.S. 919 (1970). (The Crown Zellerbach case

10/ Ibid. See generally authorities cited at note 23, infra

14

In setting out these guideline requirements, OFCC has left

unimpaired the right of Bethlehem to set reasonable non-

discriminatory job qualifications on the basis of which the

Company can^deny promotion to anyone who lacks the ability to

to the job.

ARGUMENT

I .

THE HEARING AFFORDED BETHLEHEM ONLY CONCERNS THE ISSUE OF WHETHER OR NOT

BETHLEHEM WAS IN COMPLIANCE WITH ITS CONTRACTUAL OBLIGATIONS_____________

In the appointment of a panel of arbitrators to hear

OFCC1s case against Bethlehem and in the panel's attempt to

mediate between the position of the parties, serious in

cursions were made on the authority of the Director of OFCC,

debilitating the effectiveness of the enforcement efforts

under Executive Order 11246. Implicit in these two actions

is the unacceptable notion that it is proper procedure for a

federal official charged with responsibility to enforce federal

law (in this case E.O. 11246) to yield the authority and

responsibility conferred on him to a panel of arbitrators or

mediators merely because a flagrant violator is recalcitrant.

11/ This is, we contend, all that the business necessi

defense requires or the case law allows. See Section liety

15

The Notice of Hearing issued by the.Acting Director of OFCC

dealt in part with the dangers of such a precedent by requiring

that the recommendations of the panel be made "to the

12/

Director." Apparently because no regulations precisely de

fining the authority of the Director of OFCC had then been

issued and because the Director had personally participated

in the attempts to gain compliance, former Secretary of Labor

Wirtz decided that the Secretary, personally, should be the

decision-making authority in the Bethlehem case.

It is important that the implications of this history

be understood by the present Secretary in reviewing this case:

the Secretary sits in this case as a super-Director of OFCC —

the federal official primarily responsible for equal employment

opportunity compliance efforts for the entire United States

Government. As such, he has all the responsibility and duties

which he has now delegated to the Director of OFCC under §60-1.2

13/of the OFCC Rules and Regulations.

12/ The "Rules of Procedure" attached to the notice required the Panel to certify its recommended findings and proposed

decision to the Secretary of Labor (§14); allowed any party to file a brief with the Secretary (§15); and called for a

final decision by "The Secretary or his designated repre- sentative." We contend that this designated representative should have been the Director of OFCC.

13/ 41 C.F.R. §60-1.2 (1970); at the time these proceedingswere begun, the Secretary had already delegated this authority

to the Director. Order of Secretary, 31 Fed. Reg. 692 (May 10, 1966).

16

Proper recognition of this role is of great significance

in the resolution of this and other cases arising under

Executive Order 11246. First a proper understanding of his

role includes the precepts that the Secretary's discretion is

narrowly limited by the requirements of Executive Order 11246

and that in reviewing the recommendations of the Panel he sits

not as mediator between two conflicting sides, but as the final

authority within the executive branch on what constitutes 14/

compliance.

A necessary corollary of this reasoning is that much

of what the Panel had done is irrelevant to the decision to

be made by the Secretary because the Panel's recommendations

with respect to the remedy to be applied to correct undeniably

discriminatory practices was based on its erroneous mediating

approach. As stated above, this approach accepts the un-

15/

workable (and probably unconstitutional) practice of requiring

the compromise of equal employment standards mandated by

Executive Order, Congressional Act, and constitutional principles

of equal protection of laws.

14/ J. Jones, Federal Contract Compliance in Phase II --

The Dawning of the Age of Enforcement of Equal Employment Obligation, 4 Geo. L. Rev. 756 ("mediation and conciliation

were not intended to be part of the [hearing examiner's]

mandate")

15/ See Section II A infra.

17

The proper approach for the Secretary to take in this

case, and which should have been taken by the Panel, is to

review the facts presented to the Panel fco determine whether

the OFCC's determination of noncompliance is supported by

substantial evidence. Once it is determined, that there is

substantial evidence to support OFCC's determination, it is

our position that the hearing requirements of applicable

16/regulations are satisfied. The only remaining limitations

on the Director's (or in this case the Secretary's) power

to impose the authorized sanctions of termination, con-

cellation, and debarment are those which customarily govern

discretionary administrative action -- that the action taken

be reasonable, that is, not arbitrary or capricious. Indeed,

the Panel recognized that its authority was limited in the way

we have suggested when it stated that "it serves no useful

purpose in this report to distinguish and compare cases .

[because] the principles embodied in the OFCC's . . . [proposed

16/ See Crown Zellerbach Corp. v. United States, 281 F.Supp.

337 (D.D.C. 1968) ("Evidentiary hearing required by Executive

Order 11246); A. Blumrosen, The Newport News Agreement — One

Brief Shining Moment in the Enforcement of Equal Employment

Opportunity, 1968 111. L. F. 169, 198 ("the hearing" require

ment contemplated under [Executive Order 11246] . . . need

not be a trial-type adversary proceeding. The order may

mean no more than a requirement that contractors be afforded

a full opportunity to present evidence and argument")

J. Jones, supra n. 14, at 765 ("proof of failure to comply with contractual obligations . . . is the predominant issue

in contract compliance.")

18

remedy] have a substantial basis in judicial procedent and

reason, and plainly fall within the scope of authority and

responsibility which we conferred upon the OFCC." (Panel

Report, p. 38 H47). In essence, our position is that these

findings by the Panel concerning the OFCC position are more

than is necessary to uphold the OFCC position.

Summarizing our argument with respect to the nature

of the hearing, we contend that the scheme of enforcement

established by Executive Order 11246 requires the Secretary

to review the Panel's report subject to the following

limitations:

(1) His role (and the proper role of the panel

is to determine whether there is substantial

evidence to support the charge of non-

compliance and whether the remedy proposed

by OFCC is arbitrary or capricious.

(2) If there is such substantial evidence and

the remedy is not arbitrary or capricious,

the Secretary must give conclusive weight

to the judgment of the OFCC — the agency with the responsibility for the expertise

in equal employment opportunity enforcement.

We submit that the scope of review of the OFCC

action suggested above is the only one which is consonant

with the scheme of enforcement set up by Executive Order

11246 and now implemented by the Rules and Regulations

19

17/

of the Office of Federal Contract Compliance. Had this

approach been followed by the Panel, the hearings in this case

could have been kept to a manageable length. To usurp the

authority conferred on the Director by §60-1.24 (c) (3) of the

regulations and leave to the Panel the issue of appropriate

remedy not only undermines the credibility of the Director of

OFCC in his efforts to gain voluntary compliance, but also

invites the dilatory, unproductive kind of proceedings which

were followed in this case. Indeed, quite apart from equal

employment policy considerations, it makes little practical

sense to engage in trial type proceedings when deciding the

subtle questions of remedy. As the Panel noted, the adversary

17/ see generally 41 CFR §60-1 et seq. And in particular

§60-1.24 (c) (3) which provides that:

"If the final decision rendered in accordance

with [the hearing requirement]. . . of §60-1.26

is that a violation of the equal opportunity

clause has taken place, the Director may cause

the cancellation, termination or suspension of any contract. . . cause a contractor to be de

barred from further contracts or may impose such

other sanctions as are authorized."

Although it is understaood that the effective date of these

regulations is after the initiation of hearings in this case,

we believe that even if these regulations are not binding

on the Secretary in this case, they do shed light on the

question of his proper role and thereby make easier to interpret the then applicable regulations (temporarily con

tinued from the President's Committee on Equal Employment

Opportunity, 30 Fed. Reg. 13441 (Oct. 22, 1965))which merely

provide that "Hearings shall be informally conducted."

41 CFR §60-1.27 (Revised as of January 1, 1968).

20

nature of such hearings tends to harden positions and prevent

OFCC from gaining a satisfactory resolution from the offending

party.

II.

UNDER ANY THEORY OF THE CASE, BEHTLEHEM'S

DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES, COUPLED WITH

ITS ADAMANT REFUSAL TO CONCILIATE REQUIRE

THE DEBARMENT REMEDY.____________________

A . The Constitution Requires that Bethlehem Be Debarred

Our threshhold position is that the Fifth Amendment

to the United States Constitution requires that Behtlehem

be debarred from all government contracts. This position

is set forth in the "Legal Memorandum, Authority under

Executive Order 11246" a memorandum dated July 15, 1969,

from the Solicitor of Labor to the Comptroller General,and

we contend that these arguments, made by the Solicitor in

support of the Philadelphia Plan, are applicable here and

binding on the Secretary of Labor. In essence, the argument

is based on the recognition that a federal official, bound

by his oath of office to faithfully execute his duties and

support and defend the Constitution, cannot spend federal

monies in a manner that denies equal protection of the laws

to minority groups. It is well settled that Fourteenth

Amendment equal protection requirements (which are applicable

to the States) are included within the Fifth Amendment's due

21

process guarantee (to which every federal official must

18/

conform). It is equally well settled that under the Equal

Protection Clause, a government can neither discriminate

directly, nor contract with a private party to perform 19/

services for the government when that party is discriminating.

Applying these principles to the present case, it is

clear that the Fifth Amendment's equal protection guarantees

require that the Secretary not spend any federal monies with

Bethlehem. The OFCC, the Panel, and the manifest weight of

the evidence all agree that Bethlehem is currently discriminat

ing against blacks by use of a seniority system which perpetuates

the effects of earlier discriminatory hiring, job assignment,

and transfer practices. Since the fact of discrimination is

established, the Secretary would violate the Fifth Amendment

by authorizing the use of federal monies in such a dis

criminatory manner. He must therefore debar.

18/ Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954); Washington v.Legrant, decided with Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 168 (1969);

Green v. Kennedy, 309 F .Supp . 1127 (D.D.C. 1970).

19/ Reitman v. Multke, 389 U.S. 369 (1967); Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1960); Simkins v.

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963),

cert denied, 376 U.S. 938 (1964); Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship

Committe, 223 F.Supp. 12, 22 (N.D. 111. 1963), vacated as moot

without commenting on merits, 332 F.2d 243 (7th Cir. 1963),

cert denied, 380 U.S. 917 (1964); Note, State Action:

Significant Involvement in Ostencibly Private Discrimination,

65 Mich. 17. Rev. 777 ^1967) .

22

B . Proper Interpretation of Executive Order 11246 Requires

That Bethlehem be Debarred

As the discussion of scope of review (Section I above)

establishes, quite apart from constitutional requirements, a

proper interpretation of the purpose and intent of Executive

Order 11246 leads to the conclusion that the only issue which

should be before a hearing Panel convened pursuant to the

order is whether or not the contractor is in compliance with

its contractual equal employment opportunity obligations; once

a violation is established, the Director of OFCC (in this

case the Secretary of Labor) is authorized to employ the

debarment remedy, in his discretion. This discretion is of

course limited by the purposes of the order, but the authority

to debar or to debar unless conditions which assure compliance

20/

are met is clearly vested in the Director of OFCC; it is his

judgment, subject to judicial review, for arbitrariness or

capriciousness, which determines whether a violator has cured

his breach of contract by offering to follow a plan which will

satisfy his obligations and cure the breach.

Under this theory of the case, it is clear that the

record requires that Bethlehem be debarred. The OFCC, the

Panel, and the manifest weight of the evidence all agree that

2 0/ 41 C.F.R. §60-1.24 (c) (3) (1970). For discussion of

relevance of present regulations to this case, see note 17, supra.

23

Bethlehem has been guilty of blatant racial discrimination

and that the present seniority system perpetuates the effects

of this discrimination. Thus, it cannot be denied that

Bethlehem is in violation of its contractual obligations.

This is all that is necessary under E.O. 11246 to authorize

21/the Director of OFCC to debar Bethlehem. Inasmuch as the

Director has already recommended that Bethlehem be debarred,

the Secretary must follow this recommendation, in the absence

of a finding that the use of this remedy by the Director is

arbitrary or capricious. Considering that the Panel has found

that the Director's position that in order to cure its breach,

Bethlehem must allow victims of discrimination to compete for

job openings on the basis of plan seniority and to retain

present wage rates should they transfer has "a substantial

basis in judicial precedent and reason, and plainly [falls]

within the scope of the authority and responsibility conferred

upon OFCC," a finding of arbitrariness or capriciousness is

surely precluded.

It should be noted that under this theory of the case,

all of the evidence presented by Bethlehem as to the hardships

caused by the guidelines which OFCC demanded that Bethlehem

follow in curing its breach are irrelevant. Since the only

21/ See Hadnott v. Laird, 63 CCH Employment Practices [̂9528

(D.D.C. 1970) appeal noticed No. 24, 956 (1970) (suit to enjoin

Secretary of Defense from contracting with discriminatory

employers dismissed on other grounds; pending appeal may

establish that cause of action against Secretary exists).

24

issue before the Panel was (or should have been) whether

Bethlehem was guilty of a breach, that is noncompliance, the

only evidence which wogld have been admissible was evidence

that Bethlehem was not discriminating. It is perfectly clear,

22/

as the Panel found, that Bethlehem offered no such evidence.

Moreover, an analysis of the posture of the case before the

Panel makes it clear that Bethlehem could not present any

evidence of compliance. Throughout the proceedings Bethlehem

took the position that its seniority system was non-discrimina-

tory; this untenable and uncooperative position by Bethlehem

was rejected unanimously by the Panel because it is now settled

law that perpetuating the present effects of past discrimination

23/constitutes present discrimination. The record thus

22/ Panel Report p. 41 [̂53

23/ Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkeis v. U.S.416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969) cert denied, 397 U.S. 9l9 (1970); Quarles v.

Phin jp Morris. Inc.. 279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968); Griggs v .

Duke Power Co., 420 F.2d 122 5 (4th Cir.) cert granted on otheF

issues, June 29, 1970; Irvin v. Molhawk Rubber Co., 308 F.Supp.

152 (D. Akr. 1970); United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 312

F.Supp. 977 (W.D.N.Y.), appeal noticed, No. 35183 (2nd Cir.June 12, 1970). See generally Gould, Employment Security.

Seniority and Race: The Role of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 13 Haward L.J. 1 (1967); Gould, Seniority and the

Black Worker; Reflections on Quaries and its Implications, 47

Texas L. Rev. 1039 (1969); Cooper & Sobel, Seniority and

Testing under Employment Laws; A General Approach To Objective

Criteria of Hiring and Promotion 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598(1969);

Note, Title VII, Seniority Discrimination and the Incumbent

Negro, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 1260 (1967).

25

establishes that, even limited solely to the question of

seniority, Bethlehem was guilty of a present breach of its

equal employment opportunity obligations. Even if the

inadequate plan proposed by the Company could be deemed to

be a compliance posture if implemented, the fact of the

matter is that Bethlehem to this day has not altered its

clearly discriminatory system, even in the token way suggested

by the Panel majority. Thus, throughout the four years since

Bethlehem was notified of the discriminatory nature of its

seniority system, the Company has done nothing to cure this

breach of its obligations. Surely, this record of recalcitrance

requires that Bethlehem be debarred.

26

C . Even Assuming That It Was Appropriate for Panel to

Conduct a Trial-type Hearing on All Issues, the

Record Requires That Bethlehem Be Debarred.

As stated above, the Panel found that Bethlehem was guilty

of discrimination in the past, that the current seniority system

perpetuated the effects of this prior discrimination, and that

OFCC's recommended remedies--plant seniority and rate retention

for the affected class— were supported by the applicable cases

and within the scope of OFCC's authority. These findings clearly

require a recommendation that Bethlehem should be debarred.

The Panel sought to avoid the only result supported by the record

and applicable case law by means of the "business necessity"

defense. In doing so, the Panel not only misconstrued the

nature of the business necessity test, but reached its conclusion

on the basis of evidence which was neither probative nor sub

stantial, even under its erroneous view of the law.

1. A Proper Interpretation of the Business Necessity Defense Requires Debarment.

The leading case on the business necessity test as it

applies to seniority systems is Local 189, United Papermakers

24/

and Paperworkers v. United States. In that case, Judge Wisdom,

the judicial author of the business necessity defense, held

that a unit seniority system which perpetuated the effects of

prior discrimination was a discriminatory practice which

violates both the equal opportunity clause required by E.O.

24/ Supra, note 23.

27

11246 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In

doing so, he directly rejected the arguments of the union

and the employer that the substitution of plant-wide seniority

for unit seniority would have "disastrous" consequences on the

operation of the paper mill, stating that such a defense could

be established only by a showing that "the job seniority

standard . . . is so necessary to . . . [the employer's] opera

tions as to justify locking Negroes . . . into permanent

25/

inferiority in their terms and conditions of employment."

Inasmuch as "Congress did not intend to freeze an entire

26/

generation of Negro employees into discriminatory patterns,"

a showing of such necessity can only be made by the most com

pelling evidence: mere expense or inconvenience will not

satisfy the requirement; a company relying on such a defense

will have to establish that unit seniority is "essential to

27/the safe and efficient operation" of the plant.

Although the opinion does not spell out definitively

exactly what evidence will suffice to establish this defense,

it is clear that a mere showing that the present system

furthers safety and efficiency is not enough to justify con

tinuing the discrimination worked by it. In Local 189,

employees of the Company and the Union testified that aboli

tion of the unit seniority system would create unrest by

25/ 416 F.2d at 989.

26/ Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505, 516

(E.D. Va. 1968).

27/ Local 189, supra, at 989 (emphasis added).

28

allowing employees to "jump" over others and might allow

unqualified employees to gain jobs which they could not

perform- The Court found that such evidence was insufficient

to establish the defense because "job seniority does not pro- 28./

vide the only safe or efficient system for governing promotions."

The Court upheld the right of the Company to pass upon the

ability of any worker to do a job and the right of a company

to require that an employee have the necessary experience at

lower jobs on a progression ladder before he could be promoted

to a higher job for which the lower job experience was neces

sary. Since such interests could be protected by a "residence"

requirement of prior service in the lower ranking job before

promotion, the seniority system was not essential to the safe

and efficient operation of the plant and therefore could not

be a justification for continuing discrimination. Similarly,

in Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., the Court recognized that

Operation of the company's business on

departmental lines with restrictive depart

mental transfers serves many legitimate management functions. It promotes efficiency,

encourages junior employees to remain with

the company because of the prospects of advance

ment, and limits the amount of retraining that

would be necessary without departmental or

ganization. 29/

Nonetheless, it did not find these reasons sufficient to lock

the employees of Philip Morris into inferior positions based

on prior discrimination.

28/ 416 F.2d at 990 (emphasis in original).

29/ 279 F. Supp. 505, 513 (E.D. Va. 1968).

29

Applying the principles of Local 189 and Quarles to the

present case, it is clear that Bethlehem has filed to establish

the defense. The only evidence which Bethlehem introduced on

this point was the testimony of labor and management employees

that abolition of the unit seniority system would allow un

trained workers to obtain jobs which they were not trained to

perform and would be injurious to worker morale because it would

frustrate the settled expectations of the beneficiaries of

discrimination in the discriminatory seniority system and that

rate retention would undermine the equal-pay-for-equal-job

"hallmark" of labor-management negotiations in the steel industry.

Such evidence is plainly insufficient to establish the business

necessity defense as defined in the applicable cases. The

assertion that plant-wide seniority would require Bethlehem

to promote unqualified workers is false; the government has

always conceded the company's right to require that workers be

qualified to do their jobs. To the extent that training and

experience can be demonstrated to be necessary, the Company

can require employees to obtain the necessary experience before

promoting them; this was exactly what the court allowed in

Local 189. The expectations of workers that they will continue

to reap the benefits of past discrimination are entitled to

the same weight in this case than they were given in Local 189

and Quarles: none whatsoever. Companies and unions cannot be

allowed to continue discriminatory practices merely because

some of the workers who benefit from the discrimination will

30

become disruptive or disrupted when their ill-gotten gains

30/are circumscribed. The testimony that rate retention would

undermine the equal-pay-for-equal-job principle is similarly

insufficient and irrelevant to establish the defense of

business necessity. This testimony did not and could not in

any way indicate that rate retention would place workers in jobs

they could not perform; to the contrary, the apparent fear of the

labor-management witnesses was that rate retention might lock

overqualified workers who transferred from higher ranking jobs

in the formerly black seniority units into entry level jobs in

formerly white units. Such evidence is clearly not the showing of

"overriding business necessity" required to establish the defense.

In simple terms, the Panel completely misunderstood what

the Court in Local 189 meant when it spoke of seniority being

essential to safe and efficient operations. The Panel applied

and made the test of business necessity one of business conven

ience . Even if the "expert" testimony, which consisted of

only conclusory assertions unsupported by the slightest bit of

empirical data, is to be fully credited, all that it established

was that it would be more convenient and less expensive for

Bethlehem to continue discriminating; such evidence is irrele

vant to the question of whether the seniority system was

necessary, i.e., essential. In short, the Panel's belief that

the "problems of morale, costs and administrative burdens"

30/ Cf. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)(possible violence

in desegregation not a permissible consideration for a

Court). See Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., discussed infra in

note 31.

31

are "of some weight . . . on the issue of business necessity"31/

(Panel Report p. 47, f72) is contrary to the appliable law.

The Panel, perhaps realizing that its analysis contradicted

the applicable and binding decisions of the courts, sought to

avoid the ineluctable conclusion that Bethlehem's case was

irrelevant to the question of business necessity, and distinguish

31/ Numerous decisions under Title VII have required the complete

reorganization of company and union policies governing hiring,

promotions, transfers and referrals. For example, in Vogler

v. McCarty, Inc., the court declared unlawful the nepotistic

and other exclusionary policies of Local 53 of the Asbestos workers as applied to blacks and Spanish surnamed persons and

ordered the union to refer blacks and Spanish surnamed appli

cants on a one—for—one basis with white applicants for referral.

294 F. Supp. 368 (E.D. La. 1967) aff'd sub, nom., Asbestos

Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969). In a sub

sequent and more detailed order granting additional relief, the court continued the one-for-one referral and required:

1) that the maintenance of several detailed work referral

registers according to rigorously prescribed conditions, a

detailed program to attrack minority applicants and detailed

frequent reports to the court (obviously severe administrative

burdens); and 2) that at the end of thirty days all improvers

or apprentices working under the jurisdiction of local 53 must

be terminated and referred on a one-for-one basis (obviously

resulting in a lowering of the morale of white improvers or apprentices who had previously been insulated from competition

with black applicants) 62 L.C. 9411 (E.D. La. 1970). Accord:

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 10, 3 EPD 58068

(D.C. N.J. 1970). See also. United States v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969)(union referral

system); Quarles, supra and Local 189, supra (seniority

system and promotions); United States v. Libbey Owens-Ford

Co., 3 EPD 58052 (D.C. Ohio 1970)(transfer rights including

requirement of training and educational benefits).

Indeed, courts have consistently noted that the obliga

tion of the courts under Title VII is to require companies

and unions to take whatever steps are needed to correct

their discriminatory practices. Bowe v. Colgate Palmolive

Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969); Asbestos Workers Local

53 v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047. Surely under E.O. 11246 the

obligations of the Secretary of Labor which we contend are

of a constitutional dimension cannot permit him to require

less, simply because of costs, morale or administrative

burden.

32

Local 189 and Quarles on the ground that their rules relating

to a paper mill and a tobacco plant, respectively, could not

be applied to steel plants. Instead, the Panel majority sought

to rely on Whitfield v. United Steelworkers, a 1959 case in

which Judge Wisdom, writing for the Fifth Circuit panel held

that the National Labor Relations Act did not require the

abolition of a unit seniority system. In the recent case of

32/

Taylor v. Armco Steel Corp., a case involving the identical

company and seniority practices approved in Whitfield, Judge

Wisdom made clear that Whitfield no longer had any vitality under

Title VII and that Local 189's rulings were as applicable to the

steel industry as any other industry.

Similarly, the Panel's reliance on the cases of United

33/

States v. H. K. Porter Co., and United States v. Bethlehem Steel

34/Corp., is misplaced. H.K. Porter is currently before Fifth

Circuit, whose chief judge has indicated to attorneys for the

35/parties that it will be reversed; even if this reversal is

not considered, the case is clearly distinguishable from this

one because its result was bottomed on a specific finding that

the on-the-job training required by the seniority system was

32/ 429 F. 2d 498 (5 th Cir. 1970).

33/ 296 F. Supp. 40 (N.D. Ala. 1968), appeal noticed No. __

(5th Cir. 1968).

34/ 312 F. Supp. 977 (W.D. N.Y.), appeal noticed No. 35183

(2nd Cir. June 12, 1970).

35/ The court has contacted the parties to request that the

parties assist it in formulating a decree which will

reverse the district court decision.

33

36/

necessary to the safety of the employees, whereas in this

case no such finding is possible. The District Court in

the case involving Bethlehem’s Lackawanna plant based its

failure to grant relief in part on its finding that the remedy

requested by the Attorney General

benefits certain Negroes but not whites who

are similarly situated. . . • The proof m this

case indicates that Bethlehem Steel Company s discriminatory assignment policies related not

alone to Negroes but also to ethnic minoritiesin general. . . . Simply because the Attorney

General has, for practical results, limited its

case to Negroes, does not require the court to

be so limited in providing relief. Indeed, to

do so under these facts would be arbitrary, unfair and unwarranted under the evidence pre

sen ted

To the extent that this reason constituted the basis for the

result there, that case is clearly distinguishable on that

ground from this one in which the remedy applies to all workers

who were the victims of discrimination. To the extent that

any other of the considerations mentioned by the Court in

Bethlehem influenced its decision, that case is in direct

conflict with the overwhelming weight of authority and is no

legal basis for the decision here.

36/ 296 F.

37/ 312 F.

Supp. at 90; see Local 189, supra,

Supp. at 994.

n . 23 at 993.

34

2. Even Under Panel's Interpretation of Business

Necessity the Evidence Failed to Establish

This Defense.

a. Evidence not Probative. Even assuming that the

Panel's erroneous interpretation of the business necessity

defense was valid -- and that a showing of enormous costs in

terms of morale, disruption, extra pay, and administrative

burdens could establish a business necessity defense — the

evidence clearly fails to establish such a defense. The only

testimony on this point was that of Mr. Schubert, Bethlehem's

Assistant Manager of Industrial Relations, and Mr. Fischer,

the Union's Director of Contract Administration. Their self-

serving assertions, unsupported by a scintilla of empirical

data, can hardly be called "proof" that the burdens on

Bethlehem would be so great as to make application of OFCC's

suggested remedies "arbitrary and capricious" as the Panel

itself deemed necessary to establish the business necessity

38/

defense in this case. Surely the Company must come forward

with some concrete evidence of the amount that the remedies

will cost and not merely wail and moan on the record to

establish its case. This concrete evidence must consist of

expert testimony based on statistical and other empirical

38/ See Panel Report p. 39 1[48(3): "In an executive order

proceeding, this type defense would require a showing of such

over-riding adverse effects on safety and efficiency as to

render the OFCC's guidelines arbitrary and unreasonable as

applied to the individual facts."

35

data which would establish that the proposed action would be

arbitrary and capricious with the same quality of proof as

would be required of a public utility attempting to prove 39/

that a rate set by a public service commission is confiscatory.

Thus, as a matter of law, the unsupported, self-serving asser

tions by employees of Bethlehem and the United Steelworkers

are not probative and should not have been considered by the

panel.

b. Evidence not Substantial. Even assuming that the

Panel should have considered the dubious evidence supplied

by Bethlehem, this evidence cannot be deemed substantial

enough to establish a defense which allows public condonation

of discriminatory practices. If there were any substance to

the claims by Bethlehem, surely the Company could have offered

testimony of industrial engineers and cost accountants in

support of its blanket assertions.

Further, as the opinion of dissenting member Bailer

points out, the analysis of Mr. Fischer, which is accepted

uncritically by the Panel majority, miscalculates the cost of

the remedy proposed by OFCC because they completely miscon

strue the nature of this remedy. All that the abolition of

unit seniority means is that in the future, employees will

39/ Including expert testimony from industrial engineers

and cost accountants which would establish both the likelihood and

the exact amount or at least the magnitude of the alleged

increases in cost.

36

compete for vacancies on the basis of total service in the

plant. To the extent that any job requires prior experience

or training, and the majority appears to find that all jobs

do require experience in jobs below them in the seniority

ladder, the Company can, consistent with Local 189, require

such experience and training. Thus, as the dissent points

out, the possibility that abolition of unit seniority will

result in "leapforgging" is a "house of straw" erected by the

majority.

Similarly, the statements with respect to the effects

of rate retention are unsupported nonsense. Nowhere in the

testimony of Messrs. Schubert and Fischer, or in the analysis

of the panel majority, is there a particle of evidence to

support the assertion that rate retention will work havoc

with the equal-pay-for-equal-job "hallmark" of the steel

industry. Exactly how this temporary relief, granted for a

limited period of time to a limited class of employees who

are the proven victims of blatant racial discrimination, is

going to "undermine the whole structure of wages in the steel

industry" never appears. To the extent that such a structure

would be undermined by the granting of fair treatment to the

victims of discrimination, it is a structure which rests on

a foundation of illegal racial discrimination — a structure

it was the very purpose of E.O. 11246 to tear down.

37

Given the dubious, self-serving nature of Bethlehem's

proof and the Panel majority's misconceptions concerning the

nature and effect of the proposed remedy, its conclusions with

respect to the "business necessity" of Bethlehem's discrimina

tory practices can hardly be said to be supported by substan

tial evidence. To the contrary, the evidence offered by Dr.

Rowan, the Government's disinterested expert, including the

examples of the experience with returning veterans after

World War II, established that any problems created by the

remedies of rate retention and plant-wide seniority had been

successfully handled by the steel industry before and, there

was every reason to believe, could be successfully handled

now. This expert testimony, which the panel arbitrarily dis-

■credited, makes the almost non-existent case of Bethlehem

even weaker. In no way can it be said that Bethlehem has

proved the defense of business necessity or that the Panel's

finding that Bethlehem has proved the defense is supported

by substantial evidence.

■r-V

D . Even if the Business Necessity Test Is Established,

Bethlehem's Failure or Refusal to Comply with OFCC

Guidelines Violated Its Affirmative Action Obligations.

Even assuming that the Panel majority's finding that

the hardship to Bethlehem (consisting of damage to morale,

increased costs, and administrative burdens) was too great to

38

justify following the court-approved guideline remedies

demanded by OFCC in order to bring Bethlehem into compliance

with its equal employment opportunity obligations, these

demands were clearly justified under the affirmative action

clause of E.O. 11246. Under this clause, the contractor agrees

that he will

take affirmative action to insure that

applicants are employed, and that em

ployees are treated during employment,

without regard to their race, religion,

sex, or national origin. Such action

shall include, but not be limited to:

employment upgrading, demotion or trans

fer, . . . layoff or termination; rates

of pay or other forms of compensation;

and selection for training, including

apprenticeship.

Clearly under this clause OFCC can require Bethlehem

to take affirmative action to upgrade and transfer the victims

of discrimination, increase their rates of pay and other forms

of compensation, and select them for training. Just as clearly

any demotion, transfer, or layoff or termination of the bene

ficiaries of past discrimination would be authorized by the

clause.

We contend that the affirmative action clause requires

these remedies not only to cure the present discrimination

worked by the seniority system -- perpetuation of effects of

prior discrimination — but also as a form of reparations for

Bethlehem's past discrimination. Thus, even if the Panel's

39

coupled with rate retention. Thus, it is our position that.

quite apart fro. considerations of rectifying present effects

necessity of rectifying past of past discrimination, the necessity

wrongs requires the OFCC1s requested remedies.

refused to honor its commitment under the affirmative action

clause, it should be debarred.

III.

Z STS SSS52

ORDER 11246------- ----- ------ -

We agree with the Panel's dissenting — er that "The

Company plan recommended by the majority

cient in achieving the objective of correcting the presen

• • 4-a ™ suffered by Negro employeeseffects of past discrimination suff

Point " (Panel Report p. 76 199). We also con at Sparrows Point. ^ r

• a n-t-n to cure Bethlehem’s past breaches tend the remedy is inadequate to c

and to meet its present "affirmative action" duties.

In essence, the Company's plan calls for a merger o

seniority units, reducing the number of units from 217 to 155.

This merger of units together with improved procedures for

posting notice of job openings is supposed to increase the

ability of Bethlehem's employees in general to transfer an

• aid the victims of past discrimination;tliojrGbY indirectly

. a for either plant seniority carryover the plan does not provide for eitner P

41

coupled with rate retention. Thus, it is our position that,

quite apart from considerations of rectifying present effects

of past discrimination, the necessity of rectifying past

wrongs requires the OFCC1s requested remedies. Since Bethlehem

refused to honor its commitment under the affirmative action

clause, it should be debarred.

III.

THE REMEDY RECOMMENDED BY BETHLEHEM

AND BY THE PANEL VIOLATES EXECUTIVE

ORDER 11246________________________

We agree with the Panel's dissenting member that "The

Company plan recommended by the majority is seriously defi

cient in achieving the objective of correcting the present

effects of past discrimination suffered by Negro employees

at Sparrows Point." (Panel Report p. 76 H99). We also con

tend the remedy is inadequate to cure Bethlehem's past breaches

and to meet its present “affirmative action duties.

In essence, the Company's plan calls for a merger of

seniority units, reducing the number of units from 217 to 155.

This merger of units together with improved procedures for

posting notice of job openings is supposed to increase the

ability of Bethlehem's employees in general to transfer and

thereby indirectly aid the victims of past discrimination;

the plan does not provide for either plant seniority carryover

41

or rate retention. As the dissent points out:

The Company's calculations indicate

that approximately 31% of the Negro ar

gaining unit employees (as of May 1, I9 would, under this plan, become part of a merged unit in which the earnings opportun

ities are higher than in their units [PX-V4 at 9]. Of course, this means

that iver two-thirds of the Negro employees

in the bargaining unit would not be f ably affected in this respect by virtue of the unit mergers. The Company states that

4.615 Negroes, or 55.7%. would be in larger

seniority units than before. [PX-V4 at i/j.

This means that 44.3% would not be included

In such larger units and therefore would not

have a broader base in terms of their exist ing status and rights relative to potential

demotion or layoff.

There remains, of course, the question

as to whether Negro employees in some merge

units might become more vulnerable to bump

ing" from above when layoffs occur, s y by virtue of the fact that there would be

more employees in higher level jobs in th

merged units who could exercise displace

ment rights in lower level jobs in such units A similar question concerns the effect

of the reduction in the number of pools under the Company plan. Finally, approximately 40%

of the Negro bargaining unit employees av been working in seniority units that would not be Sffected^y the unit merger Procedure Thus

on its face, and quite apart from the lack of

plant seniority carryover and rate retenti ,

the merger aspect of the Company P seriously deficient by virtue of the large nroDortion of discriminated Negro employees whose1" opportunities would not be improved thereby. Moreover, the merger proposal represents

little or no improvement in the abili y Negro employees to move from production gobs

?o!he various types of skilled maintenance

42

jobs from which they have been largely

excluded in the past.41/

Even the majority recognizes that a plan which leaves the

discriminatory wage rate earned by 69% of the victims of

prior discrimination unaffected, which leaves the discrimina

tory lay-off status of 44.3% of the prior victims unaffected,

and which may leave a detrimental effect on the layoff status

on the other 55.7% does not constitute a satisfactory solution:

The OFCC appears to have merit in its

argument that there will be Negroes not

so situated as to take advantage of this

plan . .„. by further study and possible

amendment of this plan the majority feels

that the most efficacious program can be

devised for remedying the effects of past

discrimination. (Panel Report p. 73 f92)

Moreover, the inference that the Panel majority did

not really consider the Company's plan to be full compliance

is clear from their suggestion that the Secretary "should

retain jurisdiction over the case for a period of 60 days

during which there should be a thorough investigation of any

gaps, flaws, or failures in the Company's plan and an explora

tion of supplementary methods of relief which may be practical

and feasible." (Panel Report p. 75 f97).

41/ For a fuller discussion of deficiencies of Company plan

see letter of August 11, 1969 of William Fauver, Special Counsel

of OFCC, to Rev. Hanley, pp. 4-6.

43

Thus, the panel majority, apparently feeling con

strained as mediators to propose some concrete solution,

recommended adoption of a Company plan which they realized

did not really constitute compliance. The Secretary should

not be so confused. The OFCC is perfectly correct in its

position that once it proved discrimination — m this case

both past and present - the onus was on Bethlehem to come

forward with a plan for compliance. This the Company has

clearly failed to do. Accordingly it should be debarred.

IV.

the positions taken by the department JUSTICE, THE SOLICITOR OF LABOR, AND “ c ARE binding on the secretary

I f j l l o i A ® REQUIBE THAT BETHLEHEM BE

d e b a r r e d ______.— ------------ ---------

Our arguments that debarment is constitutionally

required by the equal protection guarantees subsumed

within the Fifth Amendment's due process requirements are

specifically approved by the memorandum of duly IS, 1969 Plan

from the Solicitor of Labor to the Comptroller General in

which the solicitor, with the concurrence of the Department

of Justice, upheld the constitutionality of the PhiladSiEiiia

Plan— XThe Solicitor's advice with respect to constitutional

duties of the secretary must surely be binding on the Secretary,

especially when his position has the specific concurrence of

42/ Memo of Dep’t of Labor

1969; 71 Lab. Rel. Rep. 366 Sec. of Labor Schultz Sept.

(Daily ed. Dec. 18, 1969).

BNA Daily Labor Report

(1969); Att'y Gen. Op., 22, 1969, 115 Cong. Rec.

, July 16, letter to 17,204-06

44

the Department of Justice. Thus, we believe that the

Secretary is bound by the position that the debarment remedy

is constitutionally required.

Moreover, the position we take here with respect to

the requirements of Executive Order 11246 is not only that

of OFCC, but that of the Department of Justice with respect43/

to Bethlehem's Lackawanna plant. We believe that the Secretary

is precluded from taking a position here which is in direct

conflict not only with both the OFCC — the agency with the

responsibility and expertise in contract compliance — but

also the Department of Justice — the ultimate authority in

the executive with respect to enforcement matters. For the

Secretary to disregard the otherwise consistent position of

all agencies of the Uhited States Government with respect to

the very issues — plant—wide seniority and rate retention

_ crucial to this case would raise serious questions con

cerning the Secretary's desire to enforce the law with

respect to Bethlehem. This is especially true when the