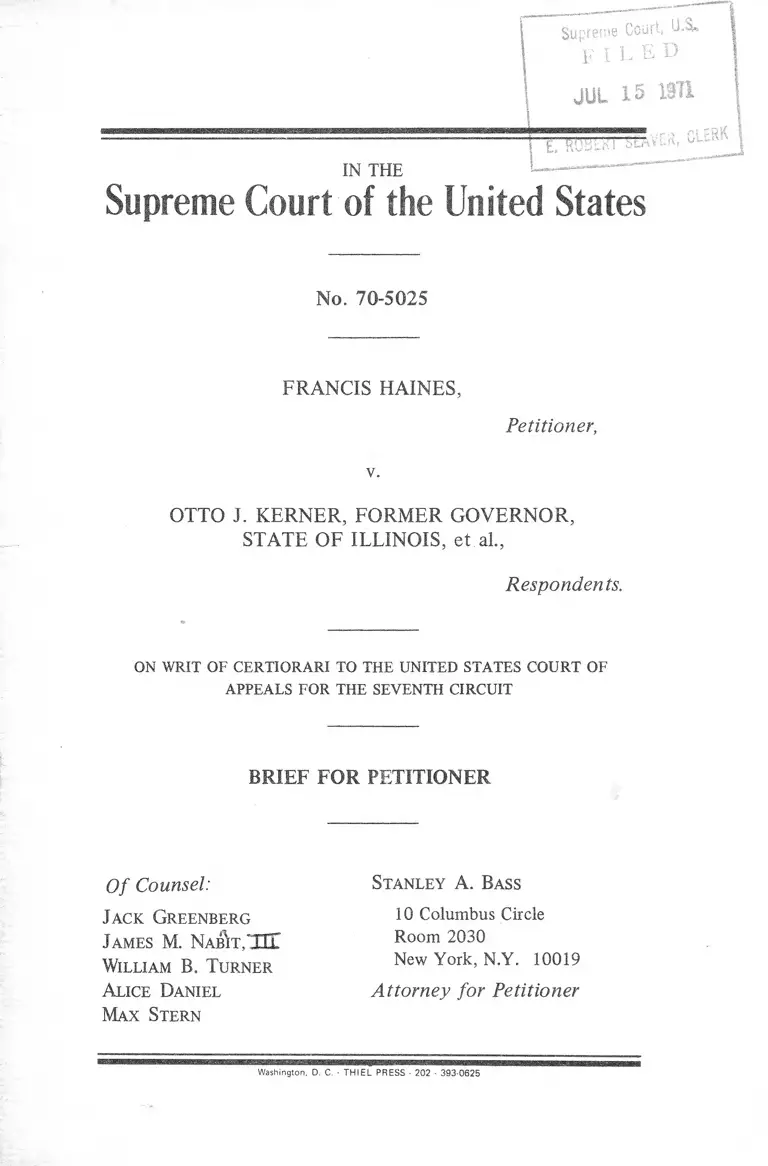

Haines v. Kerner Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

July 15, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Haines v. Kerner Brief for Petitioner, 1971. 3699971b-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/26d6eb92-a974-42b1-8daa-a7952fdb6448/haines-v-kerner-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court, 1

i i l e r

I JUL 15 1911

memmmi ,-t> c p K

.S'EAVErt, U-twv

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OTTO I. KERNER, FORMER GOVERNOR,

STATE OF ILLINOIS, et al,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

No, 70-5025

FRANCIS HAINES,

Petitioner,

v.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

O f Counsel:

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m es M. N a b it .T I T

Wil l ia m B. T u r n e r

A l ic e D a n ie l

Ma x S t e r n

S t a n l e y A . B ass

10 Columbus Circle

Room 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorney for Petitioner

Washington, D. C. - TH IEL PRESS - 202 • 393-0625

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINIONS BELOW ........................................................................... 1

JURISDICTION........................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATU

TORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED............................................. 2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ............................................................ 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ....................................................... 3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT...................... 6

ARGUMENT:

I. The Conditions of Solitary Confinement in the Illinois

State Penitentiary, as Administered to a Partially Dis

abled Sexagenarian Prisoner Under the Circumstances

of This Case Constituted Cruel and Unusual Punish

ment in Violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth

Amendments........................................................................... 7

II. Petitioner Was Unconstitutionally Deprived of Proce

dural Due Process of Law in the Prison Disciplinary

Proceedings............................................................................. 18

CONCLUSION.................................................................................. 23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Barnes v. Hocker, No. R-2071 (D. Nev. Sept. 5, 1 9 6 9 ) ............... 10

Barnett v. Rodgers, 410 F.2d 995 (D.C. Cir. 1969) .................... 12

Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau

of Narcotics,__ U .S.___ , 39 U.S.L. Week 4821 (June

21, 1971) .................................................................................... 9

Blyden v. Hogan, 320 F. Supp. 513 (S.D. N.Y. 1970)................. 21

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1971)............................... 18

Borden’s Farm Products, Inc. v. Baldwin, 293 U.S. 194

(1934)...................................................... .................................... 13

Bransted v. Schmidt, 324 F. Supp. 1232 (W.D. Wis. 1971) . . . . 19

Brooks v. Florida, 389 U.S. 413 (1967) ................................. 8, 10, 17

Brown v. Peyton, 437 F.2d 1228 (4th Cir. 1971) ....................... 14

Bums v. Swenson, 288 F. Supp. 4 (W.D. Mo. 1967) ............ 15

Bums v. Swenson, 430 F.2d 771 (8th Cir. 1 970 )......................... 7

Carothers v. Follette, 314 F. Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970) . . . 15, 20

Clay (Ali) v. United States, ___ U.S. ___, 39 U.S.L. Week

4873 (June 28, 1 9 7 1 ) ................................................................. 23

Clutchette v. Procunier, No. C-70-2497 A.J.Z. (N.D. Cal.

June 21, 1971)...........................................................................21, 22

Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41 (1 9 5 7 )..................................... .. . 13

Cooper v. Pate, 378 U.S. 546 (1 9 6 4 )............................................ 9, 13

Counselman v. Hitchcock, 142 U.S. 547 (1892) ......................... 21

Dearman v. Woodson, 429 F.2d 1288 (10th Cir. 1970) . . . . . . . 14

Dioguardi v. Durning, 139 F.2d 774 (2d Cir. 1 9 4 4 ) .................... 5

j$ritsky v. McGinnis, 313 F. Supp. 1247 (N.D. N.Y. 1970) . . . 15

Escoe v. Zerbst, 295 U.S. 490 (1935)................. ......................... 19

Gardner v. Broderick, 392 U.S. 273 (1968)................................ 21, 23

Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1 9 6 7 )................................ 21

Giles v. Maryland, 386 U.S. 66 (1 9 6 7 )....................................... . 22

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1 9 7 0 )........................................18, 23

Goolsby v. Gagnon, 322 F. Supp. 460 (E.D. Wis. 1971) ............ 19

Hahn v. Burke, 430 F.2d 100 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied,

401 U.S____(Apr. 26, 1971)...................................................... 19

Hancock v. Avery, 301 F. Supp. 786 (M.D. Tenn. 1969).......... 10, 14

Holt v. Sarver, 300 F. Supp. 825 (E.D. Ark. 1969) .................... 10

Holt v. Sarver, 309 F. Supp. 362 (E.D. Ark.), aff’d, 4iPF.2d

M . (8th Cir. May 5, 1971) ...................................................... 17

Houghton v. Shafer, 392 U.S. 639 (1968).................................. . 9

Inmates of the Cook County Jail v. Tierney, No. 68 C-504

(N.D. 111. Aug. 28, 1 9 6 8 )........................................................ . 17

Inmates of the Maine State Prison v. Robbins, Civil No.

11-187 (D. Me., filed August 31, 1970) . ................................. 15

Page

(H i)

In Re Korman,___F .2 d ___ , 9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2161 (7th Cir.

May 20, 1 9 7 1 )............................................................................. 21

In Re Kinoy, 2Z i F. Supp. ‘1^2, 8 Cr. L. Rptr. 2327 (S.D.

N.Y. Jan. 29, 1971)................. ................................................... 21

In Re Medley, 134 U.S. 160 (1890) ............................................. 8

Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571 (8th Cir. 1968)...................... 13, 15

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 8 )...................... 12

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1 9 6 9 )................................ 8, 14, 22

Jones v. Wittenberg, 323 F. Supp. 93 (N.D. Ohio 1 9 7 1 )............ 17

Jordan v. Fitzharris, 257 F. Supp. 674 (N.D. Cal. 1 9 6 6 ).......... 10, 11

Joseph v. Rowlen, 402 F.2d 367 (7th Cir. 1968)......................... 18

Knuckles v. Prasse, 302 F. Supp. 1036 (E.D. Pa.), aff’d, 436

F.2d 1255 (3rd Cir. 1 9 7 1 ) ........................... ............................. 10

Krist v. Smith, 309 F. Supp. 497 (S.D. Ga. 1970) ...................... 11

Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333 (1968) ..................................... 8

Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459 (1947) . . . 8

McGautha v. California,___U.S____ , 39 U.S.L. Week 4529

(May 3, 1971) ........................................................................ .. . 22

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 668 (1963) ............... 18

Mathis v. United States, 391 U.S. 1 (1967 )................................... 21

Melson v. Sard, 402 F.2d 653 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ......................... 21, 22

Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967) ...................... ................. 19, 22

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966 )........................... .. 21, 23

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) .......................................... 9, 18

Morris v. Travisono, 310 F. Supp. 857 (D. R.I. 1970)............... 20, 22

Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F.2d 548 (1st Cir. 1970) ............................ 19-20

People v. Dorado, 62 Cal. 2d 338, 398 F.2d 361, 42 Cal.

Rptr. 169, cert, denied, 381 U.S. 937 (1 9 6 5 ) ........................ 21

People ex rel. Conn v. Randolph, 35 111. 2d 24, 219 N.E.2d

337 (1966) ...................................................... ................ .. 20

Piccirillo v. New York, 400 U.S. 548 (1971 )................................ 21

Picking v. Penn. Ry. Co., 151 F.2d 240 (3rd Cir. 1 9 4 5 ) ............ 5

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962)................................ 8

Page

Rodriguez v. McGinnis, 307 F. Supp. 627 (N.D. N.Y, 1969),

rev’d , ---- F .2 d ----- (2d Cir. Mar. 16, 1971)............................. 15

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91 (1945)................................ 17

Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377 (1968) ......................... 21

Sinclair v. Henderson, 435 F.2d 125 (5th Cir. 1971) ................. 12

Sostre v. Rockefeller, 312 F. Supp. 863 (S.D. N .Y .).................... 15

Sostre v. M cG innis,^! F.2d £Z f (2d Cir. Feb. 24, 1971) 11, 14, 19

Spevak v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511 (1967) ................................... .. 23

State ex rel. Johnson v. Cady, 185 N.W.2d 306 (Wis. 1971) . . . 19

Talley v. Stephens, 247 F. Supp. 683 (E.D. Ark. 1965)............... 15

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1 9 5 8 ) ............................................... 9

Uniformed Sanitation Men’s Association v. Commissioner,

392 U.S. 280 (1 9 6 8 )................................................................... 23

United States v. Jones, 207 F.2d 185 (5th Cir. 1953)................... 17

United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1 9 6 7 )................................ 22

United States ex rel. Campbell v. Pate, 401 F.2d 55 (7th Cir.

1968) ................................................................................................. 18

United States ex rel. Hancock v. Pate, 223 F. Supp. 202

(N-D. 111. 1963).................................................... ..................... 14, 20

Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1 9 6 7 ).......... .......................... 22

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1 9 1 0 ).............................. 9, 14

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1878).......................................... 9

Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235 (1970) ...................................... 13

Wright v. McMann, 321 F. Supp. 127 (N.D. N.Y. 1970) .............. 13

Wright v. McMann, 387 F.2d 519 (2d Cir. 1 9 6 7 )...................... 10, 15

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) 2

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ............................................................................... 2, 9

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38 § 7-1 ......................................................... 20

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38 §7-13 ............................................................ 20

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38 § 12-1 ............................................................ 20

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38 § 12-3 ............... 20

(iv)

Page

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 81 §37 (repealed) ............................................. 13

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 108 § 1 1 8 ........................... ............................... 20

Maine Rev. Stat. P.L. 1971 Chapter 397 (June 4, 1971),

Amending Title 34, § 709 ................................................................. 16

Regulations:

Federal Bureau of Prisons,. Policy Statement 2001.1 (Feb.

19 ,1968)........................................................ 21

Federal Bureau of Prisons, Policy Statement 7400.5, app.

A (Nov. 28, 1 9 6 6 ) .............................................. 16

Federal Bureau of Prisons, Policy Statement 7400.6 (Dec.

1, 1966) ........................................................................................ 20

Missouri State Penitentiary Rules and Procedures, Personnel

Information P am phlet............ .................................................15, 20

New York Department of Correctional Services, Regulations

for Special Housing Units (effective Oct. 19, 1970) ............... 15

Other Authorities:

American Correctional Association, Manual of Correctional

Standards (3d ed. 1966)........................................................... 16, 20

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Article 304.7(2)

(proposed official draft 1962).................................................. 20

2A Moore, Federal Practice f 12.08 (2d ed. 1968)................. .. 13

Note, Beyond the Ken o f the Courts: A Critique o f Judicial

Refusal To Review the Complaints o f Convicts, 72 Yale

L.J. 506 (1 9 6 3 ).......................................................................... 17

Opinion of New York Attorney General, 8 Cr. L. Rptr. 2486

(Feb. 11, 1971)............................................................................. 21

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Adminis

tration of Justice, Task Force Report: Corrections (1967) . . . 7

Turner, Establishing the Rule o f Law in Prisons: A Manual

for Prisoners’ Rights Litigation, 23 Stan. L. Rev. 473

(Feb. 1971)

(v)

Page

17

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

No, 70-5025

FRANCIS HAINES,

Petitioner,

v.

OTTO J. KEENER, FORMER GOVERNOR,

STATE OF ILLINOIS, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals affirming the

dismissal of petitioner’s civil action is reported at 427 F.2d

71 (1970), and is printed in the Appendix at pp. 65-66.

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Illinois is not reported, and is set forth in

the Appendix at pp. 58-60.

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

May 25, 1970, and a timely petition for rehearing, with sug

gestion that it be heard en banc, was denied on June 19,

1970. The petition for writ of certiorari was filed on

September 17, 1970, and was granted on March 8, 1971.

401 U.S. 954. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States provides, in pertinent part:

“No person shall. . . be compelled in any criminal

case to be a witness against himself, . . . ”

The Sixth Amendment provides, in pertinent part:

“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy

the right. . . to have the Assistance of Counsel for

his defence.”

The Eighth Amendment provides:

“Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive

fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments

inflicted.”

The Fourteenth Amendment provides, in pertinent part:

. nor shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law;. . . ”

This case also involves 42 U.S.C. § 1983 providing a right

of relief in damages and in equity for violations of constitu

tional rights.

3

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the District Court err in dismissing, without

requiring an answer or holding a hearing, a complaint filed

by a state prisoner, pro se, against prison officials, which

raised grave constitutional questions concerning alleged

mistreatment?

2. Did the conditions of solitary confinement in the

Illinois State Penitentiary, as administered to a partially dis

abled, sexagenarian prisoner under the circumstances of this

case, constitute cruel and unusual punishment in violation

of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments?

3. Was petitioner unconstitutionally deprived of funda

mental procedural safeguards in the prison disciplinary pro

ceedings?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Taking as true the allegations of the complaint, as they

must be on a motion to dismiss, the facts are as follows:

Francis Haines, petitioner, has been since 1939, and still

is, an inmate of the Illinois State Penitentiary, Menard

Branch, serving a life sentence for burglary.

On March 10, 1968, Haines, who was then 66 years old

and 30% permanently disabled,1 and two other inmates,

Moore and Doherty, who were then approximately 30 years

of age, were assigned to the Inside Yard Gang. One of the

defendants herein, Paul T. Duncan, was the officer in charge

of that work detail. (A. 14)

'The disability was due to the following foot injuries: Left foot—

2nd, 3rd and 4th Cuboid Bones and 3rd Metatarsal fractured, which

resulted in an Ankylosis in the Cuboid Bones. Rights foot—vertical

fractures in the heel bones, discernable only by an X-ray in a specific

position of the foot. Haines added that he had been awarded com

pensation in a hearing before the Illinois Industrial Commission for

these injuries. (App. 14).

4

Haines and the two younger inmates engaged in an argu

ment in which it seemed to Haines that Moore was urging

and inciting Doherty against Haines. Several times it was

said by both Moore and Doherty that the “Young Blood”

was taking over and that the “Old Blood” like Haines was

“done”. After this argument had proceeded for a time,

Haines returned to work and obtained a shovel for loading

cinders on a truck. He banged the shovel on the concrete

outside the Yard Gang Shack, in order to dislodge a clod of

dirt. (A. 14)

When he entered the shack, Doherty and Moore resumed

the argument, during which time Moore was very emphatic

that the “Young Blood” such as he were taking over and

that Haines had better watch out or he would be hurt. (A.

15)

A little later, Haines entered the bathroom and the other

two inmates approached him in a threatening manner and

resumed the argument. Following a provocative comment

from Doherty, Haines hit him with the shovel, inflicting cuts

on his head. Moore and Haines then scuffled briefly. After

Officer Duncan took Doherty into the back room to attend

his injuries, Moore kept making dire and foreboding threats

to Haines to the consequences of his acts. Inmate Orlando,

No. 34527, witnessed these events subsequent to Haines’

hitting the shovel on the concrete. (A. 15)

Subsequently, Officer Rogers, another defendant herein,

took Haines to what is known in the institutional vernacular

as the “hole” or solitary confinement, which in recent years

the officials call isolation. (A. 15)

Rogers took Haines before Officer Russell Lence, another

defendant herein, who was disciplinary officer that day.

Haines refused to explain his actions other than to say that

he had hit Doherty with the shovel. He was locked in an

isolation cell until a report could be had from Duncan. (A.

15-16)

When this report was obtained, Lence and Rogers called

Haines before them again and read the report to him. Haines

5

objected to statements of Duncan that he had hit the shovel

on the Yard Gang Shack floor, and refused to discuss the

statement of Duncan that he had engaged with the other

two men. Lence wanted to know why Haines would hit

Doherty and stated that it had been twenty-eight years since

Haines had been in the “hole.” When Haines refused to talk

to these officers he was given fifteen days punishment in

isolation, from March 10 to March 25, 1968. (A. 16)

This isolation, “hole,” or solitary confinement consisted

of dark cells, and the only difference Haines could see in

the intervening twenty-eight years between his trips to it

were as follows: he was given three (3) blankets instead of

two to sleep on a concrete floor; there had been a toilet

installed instead of toilet buckets formerly used; he received

(2) slices of bread every morning and evening, along with a

noon meal, instead of the four (4) slices of bread formerly

received. No articles of hygiene were furnished to him, and

his false teeth became so rancid he had to leave them out.

No towel or soap was furnished.2

Following his stay in isolation, Haines was demoted, with

out any hearing, to “C” grade under the institution’s “Pro

gressive Merit System,” which entailed the loss of certain

unspecified “privileges,” including Commissary. (A. 16, 17)

His chances of obtaining release on parole may also have

been adversely affected.

As a result of his confinement in the “hole,” Haines suf

fered great physical anguish and pain to his feet and circu

latory trouble in his legs, due to being forced to sleep on

the concrete floor. (A. 18)

2Given the liberal construction due this pro se complaint, Dio-

guardi v. Durning, 139 F.2d 774 (2d Cir. 1944); Picking v. Penn. Ry.

Co., 151 F.2d 240, 244 (3rd Cir. 1945), it may be fair to infer, that

Haines was also deprived of contact with the outside, recreation,

reading, writing, showers, and periodic examinations by a member of

the medical staff.

6

On July 1, 1968, Haines filed a complaint in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Illinois,

seeking damages, declaratory judgment and such other and

further relief as justice and equity may require, against

officers Duncan, Russell Lence, Rogers, and Sheets (the

Commissary officer), the members of the Progressive Merit

System of the Illinois State Penitentiary at Menard, the

Director of the Illinois Department of Public Safety, who

allegedly made the rules and regulations pertaining to the

Illinois State Penitentiary, and the former Governor of the

State of Illinois, who allegedly was superior to all of the

other defendants, and could have cured all defects in then-

actions by executive order. (A. 7-19)

On defendants’ motion to dismiss (A. 20-24), the District

Court dismissed the action without any hearing (A. 58-60),

and the Court of Appeals affirmed (A. 65-66), stating that—

“State prison officials are vested with wide discretion,

and discipline reasonably maintained in state prisons

is not subject to our supervisory direction.”

On March 8, 1971, this Court granted Haines’ petition

for a writ of certiorari.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

When prison officials violate the paramount federal con

stitutional right of prisoners not to be treated like animals,

without justification, the federal courts may not abdicate

their remedial jurisdiction, clearly conferred by Congress,

on the ground that “discipline reasonably maintained in

State prisons is not subject to our supervisory direction.”

The pro se complaint in this case sufficiently stated a claim

of “excessive” or “unnecessary cruelty” constituting uncon

stitutional “cruel and unusual punishment,” so as to preclude

summary dismissal by the District Court without requiring

an answer from defendants or holding an evidentiary hearing,

if necessary.

7

II.

Among the fundamental rights retained by prisoners are

their privilege against compelled self-incrimination and their

right to assistance of counsel. Without adequate protection

of these rights in a prison disciplinary proceeding where the

misconduct alleged also constitutes a prosecutable offense,

prisoners are effectively denied their rights, guaranteed by

Due Process, to a meaningful opportunity to explain away

the accusation. In this case, plaintiff was precluded from

presenting a substantial claim of self-defense, as either a

complete defense or in mitigation of punishment.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE CONDITIONS OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT IN

THE ILLINOIS STATE PENITENTIARY, AS ADMIN

ISTERED TO A PARTIALLY DISABLED, SEXAGEN

ARIAN PRISONER UNDER THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF

THIS CASE, CONSTITUTED CRUEL AND UNUSUAL

PUNISHMENT IN VIOLATION OF THE EIGHTH AND

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS.

The broad power of a State to maintain discipline in its

prisons is not here challenged, nor is the validity of the prac

tice of solitary confinement, per se, drawn in question in the

instant case.3 Rather we raise, in Point I, only the narrow

3See, e.g., Bums v. Swenson, 430 F.2d 771 (8th Cir. 1970).

Although solitary confinement has been described as one of “the

main traditional disciplinary tools” of our prison systems, President’s

Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice,

Task Force Report: Corrections 50-51 (1967), the Manual of Correc

tional Standards of the American Correctional Association contains

a candid recognition by prison officials themselves that “ [p]erhaps

we have been too dependent on isolation or solitary confinement as

the principal method of handling the violators of institutional rules.

Isolation may bring short-term conformity for some, but brings

increased disturbances and deeper grained hostility to more.” Id., at

413. It has long been recognized that solitary confinement cannot

8

issue whether, absent a showing of justification for the

specific incidents of confinement in this case, the totality of

dehumanizing, degrading and debased circumstances imposed

upon an elderly, partially disabled, prisoner for fifteen days,

in a dark cell, with three blankets to sleep on a concrete

floor, a toilet, but no towel or soap or any articles of

personal hygiene, two slices of bread morning and evening,

along with a noon meal, and where his false teeth became

so rancid he had to leave them out, violated petitioner’s

paramount federal constitutional right to be free from cruel

and unusual punishment.4

As this Court stated, in Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483,

486 (1969),

“There is no doubt that discipline and administration

of state detention facilities are state functions. They

are subject to federal authority only where para

mount federal constitutional or statutory rights

supervene. It is clear, however, that in instances

where state regulations applicable to inmates of

prison facilities conflict with such rights, the regu

lations may be invalidated.”5

In Brooks v. Florida, 389 U.S. 413 (1967), this Court

rejected, as involuntary, a state prisoner’s confession to

participating in a riot, which was obtained after he had

been confined in a punishment cell for fourteen days under

extremely onerous and disgusting conditions, which included

be considered a mere custodial matter, and that it can cause mental

illness, induce suicidal tendencies, and interfere with the possibility

of rehabilitation. See, In Re Medley, 134 U.S. 160, 167-68 (1890).

4 The command of the Eighth Amendment banning “cruel and

unusual punishments” is applicable to the States by reason of the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Louisiana ex rel.

Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459, 463 (1947); Robinson v. Califor

nia, 370 U.S. 660 (1962).

sThe Court there relied upon Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333

(1968), in which the practice of racial segregation of prisoners was

held invalid to the extent that it could not be justified by “the neces

sities of prison discipline and security.” Id., at 334.

9

restricted diet, no bed or other furnishings, no external

window, and lack of contact with the outside. The per cur

iam opinion observed: “The record in this case documents

a shocking display of barbarism which should not escape

the remedial action6 of this Court.” Id., at 415.

This Court has said that “ [t]he basic concept underlying

the Eighth Amendment is nothing less than the dignity of

man.” Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 100 (1958). The guar

antee is a flexible one, drawing its meaning from “the evolv

ing standards of decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society.” Id., at 101. Weems v. United States, 217

U.S. 349, 373 (1910) “The Eighth Amendment expresses

the revulsion of civilized man against barbarous acts—the

‘cry of horror’ against man’s inhumanity to his fellow man.”

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660, 668, 676 (1962)

(Douglas, J. concurring). Although these notions may appear

to be somewhat subjective, a more precise and judicially

manageable standard was articulated long ago; “ [I]t is safe

to affirm that punishment of torture . . . and all others in

the same line of unnecessary cruelty, are forbidden. . .”

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130, 136 (1878) (emphasis

supplied).

The lower federal courts, which have been presented

with constitutional challenges to medieval dungeon-like con

ditions in some of the worst solitary confinement cells, have

recognized the States’ legitimate interest in maintaining

prison discipline, but have not hesitated to strike down

instances of hard core “inhuman treatment,”7 which go far

beyond the actual necessities of discipline and security.

6“Remedial action,” in the form of damages or equitable relief,

has been explicitly authorized by Congress, in 42 U.S.C. § 1983, for

deprivation of constitutional rights “under color of” state law. Cf.

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961); Cooper v. Pate, 378 U.S. 546

(1964); Houghton v. Shafer, 392 U.S. 639 (1968). See also, Bivens

v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics,

__ U.S____ , 39 U.S.L. Week 4821 (June 21, 1971).

7Trop v. Dulles, supra, at 100 n. 32.

10

See, Wright v. McMann, 387 F.2d 519 (2d Cir. 1967);

Knuckles v, Prasse, 302 F.Supp. 1036, 1061-62 (E.D. Pa.

1969); affd, 436 F.2d 1255 (3rd Cir. 1971); Hancock v.

Avery, 301 F.Supp. 786 (M.D. Term. 1969); Holt v. Sarver,

300 F.Supp. 825 (E.D. Ark. 1969); Jordan v. Fitzharris,

257 F. Supp. 674 (N.D. Calif. 1966); Barnes v. Hocker, No.

R-2071 (D. Nev. Sept. 5, 1969).8

In Wright v. McMann, supra, the Second Circuit reversed

the dismissal, without a hearing, of a prisoners’ complaint

about unsanitary and degrading conditions in a solitary con

finement cell in New York’s Clinton Prison, and said:

We are of the view that civilized standards of

humane decency simply do not permit a man . . . to

be deprived of the basic elements of hygiene such as

soap and toilet paper. The subhuman conditions

alleged by Wright to exist in the “strip cell” at

Dannemora could only serve to destroy completely

8 There were some differences among the particular circumstances

involved in the above cited cases. For example, Hancock, Jordan and

Knuckles involved cells without light, while in Holt, Wright and

Barnes the cells were lighted. In Barnes, the inmate slept on an iron

bunk, while in Jordan he had a canvas mat, in Knuckles they had

blankets on the floor. In Brooks the inmate was fed pea and carrot

soup three times per day; in Hancock he was fed one regular meal

and bread twice; in Holt he received a wholesome and sufficient but

unappetizing diet; in Barnes, Jordan and Wright, they apparently

received the regular institution diet. In Brooks and Holt the cells

were overcrowded, while Jordan and Hancock involved true solitary

confinement. In all the cases, the prisoners were deprived of the

minimal comforts and institutional privileges that may make prison

life tolerable for a flexible man. Significantly, none of the cases

involved the imposition of such onerous conditions upon a partially

disabled, elderly man, as here.

the spirit and undermine the sanity of the prisoner.

The Eighth Amendment forbids treatment so foul,

so inhuman and so violative of basic concepts of

decency.9

The Court of Appeals did not rule out the possibility “that

in exceptional circumstances it might be necessary to take

from a prisoner all objects with which he could harm him

self or others,” but it observed, “apparently no determina

tion was made that this particular prisoner was or would

have become violent.” That question of fact was left for

resolution upon remand. 387 F.2d at 526 n. 15.

In Jordan v. Fitzharris, supra, the District Court declared

that—

“When. . . the responsible authorities in the use of

the strip cells have abandoned elemental concepts of * 5

9 The Second Circuit’s recent en banc decision in Sostre v.

McGinnis, 4fTF.2d 12? (2d Cir. Feb. 24, 1971), is not to the con

trary. In - Sostre, the Court enumerated six factors raising the

prisoner’s confinement “several notches above those truly barbarous

and inhumane conditions condemned elsewhere (id., at M ) . They

were: (1) the prisoner’s diet, which was the same (except for

desserts) as in the general prison population; (2) the availability or

rudimentary implements of personal hygiene; (3) the opportunity for

exercise in the open air, compare, Krist v. Smith, 309 F. Supp. 497,

501 (S.D. Ga. 1970); (4) opportunity to participate in group therapy;

(5) availability of reading matter from the prison library and unlim

ited numbers of law books; and (6) the constant possibility of com

munication with other prisoners. In addition, the Court pointed out

that the prisoner always had adequate light for reading (id. at /££),

full access to legal materials (id.) and a diet of 2800-3300 calories

a day (id. at l£Je>). Further, the Court noted the absence of any tes

timony that solitary threatened the mental or physical health of the

inmate and found that a physician visited him every day (id. at 133.

n. 24). Finally, the Court said that the prisoner aggravated his con

finement by refusing to participate in group therapy (id. at /?T )

None of these factors explicitly relied upon by the Second Circuit is

present in the instant case. In virtually every feature, Illinois-style

solitary fails the test, particularly in view of petitioner’s age and phy

sical disabilities. As the Court in Sostre observed, in n. 23, “In some

instances, depending upon the conditions of the segregation, and the

mental and physical health of the inmate, five days or even one day

might prove to be constitutionally intolerable.”

12

decency by permitting conditions to prevail of a

shocking and debased nature, then the courts must

intervene promptly . . . to restore the primal rules of

a civilized community. . . . ” Id., at 680.

And, in Sinclair v. Henderson, 435 F.2d 125, 126 (5th

Cir. 1971), the Fifth Circuit observed:

“Although federal courts are reluctant to interfere

with the internal operation and administration of

prisons, we believe that the allegations appellant

has made go beyond matters exclusively of prison

discipline and administration; and that the court

below should adjudicate the merits of the appellant’s

contentions of extreme maltreatment.”

We recognize that some form of isolation of severely

troublesome or violent prisoners is occasionally needed in

order to maintain order, and we concede that prison officials

have an area of administrative discretion in dealing with

inmates who are in fact disruptive. However, as one Court

of Appeals has said,

“acceptance of the fact that incarceration, because

of inherent administrative problems, may necessitate

the withdrawal of many rights and privileges does

not preclude recognition by the courts of a duty to

protect the prisoner from unlawful and onerous

treatment of a nature that, of itself, adds punitive

measures to those legally meted out by the court.”

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529, 532 (5th Cir.

1968).

Thus, while prison officials are entitled to some administra

tive leeway, this “does not eliminate the need for reasons

imperatively justifying the particular retraction of rights

challenged at bar.” Barnett v. Rodgers, 410 F.2d 995,

1000-1 (D.C. Cir. 1969).

13

The record in this case10 is entirely barren of any indica

tion by the State of Illinois that the unusually11 cruel

inhuman conditions imposed upon Haines, over and above

the mere fact of isolation, were actually necessary for the

preservation of order, or specifically, to contain this partic

10 The District Court dismissed the pro se drafted complaint

without, requiring any answer from the defendants, either as to the

truth of their alleged acts, or in justification therefor, and without

giving Haines any hearing. However, as Professor Moore has stated

the rule, “ [A] complaint should not be dismissed for insufficiency

unless it appears to a certainty that plaintiff is entitled to no relief

under any state of facts which could be proved in support of the

claim.” 2A Moore, Federal Practice f 12.08, at 2271-74 (2d ed.

1968). Accord, Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 45-46 (1957). More

over, “ [I] t is inexpedient to determine grave constitutional questions

upon a demurrer to a complaint, or upon an equivalent motion, if

there is a reasonable likelihood that the production of evidence will

make the answer to the questions clearer.” Borden’s Farm Products

Co., Inc. v. Baldwin, 293 U.S. 194, 213 (1934) (Stone & Cardozo JJ.,

concurring). See also, Cooper v. Pate, 378 U.S. 546 (1964). With

the assistance of counsel, and the testimony of penological experts,

e.g., Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571, 575 (8th Cir. 1968), Haines,

as well as the defendants, will have an opportunity, upon remand, to

develop all of the facts fully on the record in the District Court.

After the trial upon remand, in Wright v. McMann, supra, Judge Foley

remarked that the record is “revealing and eye-opening . . . a por

trayal of the real thing; it is prison life as it is . . . a facet of New

York State prison discipline kept covered too long from the public

view.” 321 F. Supp. 127, 131, 132 (N.D. N.W. 1970).

11 It is interesting to note that the relevant 1867 Illinois statute,

quoted in the complaint (A. 12), which has since been repealed, spe

cifically characterized, as “unusual punishment,” “solitary confine

ment in a dark cell and deprivation of food except bread and water

until such convict shall be reduced to submission and obedience”

(former ch. 81, § 37). Of course, the antiquity of this barbaric

practice does not insulate it from judicial scrutiny. As recently as

1970, this Court reiterated “ [t]he need to be open to reassessment

of ancient practices other than those explicitly mandated by the Con

stitution.” Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235, 240 (1970). “ [N]ew

cases expose old infirmities which apathy or absence of challenge has

permitted to stand.” Ibid., at 245.

14

ular prisoner, who had not been in the “hole” for the past

twenty-eight years.

“A punishment may be considered cruel and unusual

when, although applied in pursuit of a legitimate

penal aim, it goes beyond what is necessary to achieve

that aim; that is, when a punishment is unnecessarily

cruel in view of the purpose for which it is used.”

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 370 (1910)

(emphasis supplied); Dearman v. Woodson, 429 F.2d

1288, 1290 (10th Cir. 1970); Hancock v. Avery,

301 F. Supp. 786, 791 (M.D. Tenn. 1969); Jordan

v. Fitzharris, 257 F. Supp. 674, 679 (N.D. Cal.

1966).12

There is neither allegation nor evidence that Illinois con

siders it essential or even useful to confine an elderly,

partially disabled man alone in total darkness, to deprive

him of rudimentary articles of personal hygiene, a bed, fresh

air, exercise, and medical attention, and to severely restrict

his diet. Indeed, practices in other jurisdictions, which are

of “substantial probative value” in ascertaining whether a

particular restriction is necessary to some penal interest,13

tend to show that treating a man like rubbish, under the

dehumanizing conditions of solitary which existed here, is

not only unnecessary to accomplish the purpose of isola

tion, but is also futile and self-defeating, and interferes with

the primary objective of rehabilitating offenders.14

12 The imposition of such severe mistreatment for exercising the

basic right of self-defense, would seem to be an impermissible penalty

for engaging in legally protected activity, cf. Sostre v. McGinn# supra,

or at least such grossly excessive punishment in relation to Haines’

“offense,” as to violate the “precept of justice that punishment for

crime should be graduated and proportioned to offense.” Weems v.

United States, 217 U.S. 349, 367 (1910). See, United States ex rel.

Hancock v. Pate, 223 F. Supp. 202, 205 (N.D. 111. 1963).

13Brown v. Peyton, 437 F.2d 1228 (4th Cir. 1971).

14A survey questionnaire (Appendix “A” to this Brief) has been

mailed to each State’s Department of Corrections, inquiring as to the

use and conditions of solitary confinement in state prisons. The

!

15

For example, the New York regulations, which were

drafted in the context of litigation,15 establish minimum

standards for segregated confinement and provide for ade

quate bedding, hygiene, food, recreation, correspondence

and visiting.16 The Missouri regulations, also drafted during

the course of litigation,17 require heat, ventilation, and

natural and artificial light in “seclusion” cells, and, further,

provide for rules that are the same as in the general popula

tion.18 The State of Maine, in response to a lawsuit,19

recently amended its statute governing solitary confinement

to provide that “adequate sanitary and other conditions

required for the health of the inmate shall be maintained,”

that “a sufficient quantity of wholesome and nutritious

food” shall be supplied, that medical examinations be con

ducted every twenty-four hours20 and reports filed, and that

replies received so far indicate that the particular degrading circum

stances presented in the case at bar are not at all widespread. The

complete results of the survey will be provided to this Court as soon

as they are available.

15 See, Wright v. McMann, 387 F.2d 519 (2d Cir. 1967), on remand,

321 F.Supp. 127 (N.D. N.Y. 1970); Rodriguez v. McGinnis, 307

F. Supp. 627 (N.D. N.Y., 1969); rev’d ,_____ F.2d ______(2d Cir.

March 16, 1971); Sostre v. Rockefeller, 312 F.Supp. 863 (S.D. N.Y.

1970), affd in part and reversed in part, 4 4 1 F.2d (2d Cir.

Feb. 24, 1971), fjjritsky v. McGinnis, 313 F.Supp. 1247 (N.D. N.Y.

1970); Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970).

16New York Department of Correctional Services, Regulations for

Special Housing Units, pt. 301 (effective Oct. 19, 1970).

17Burns v. Swenson, 288 F.Supp. 4 (W.D. Mo. 1967).

18Missouri State Penitentiary Rules and Procedures, Personnel

Informational Pamphlet.

19Inmates of the Maine State Prison v. Robbins, Civil No. 11-187

(D. Me. filed Aug. 31, 1970).

20Some conditions of confinement may so contravene civilized

standards that even if their “infliction is surrounded by appropriate

safeguards,” Talley v. Stephens, 247 F.Supp. 683, 689 (E.D. Ark.

1965), which are absent here, it will not save the practice from con

16

if “ the recommendations of the prison physician or consult

ing psychiatrist are not carried out by the warden, a report

thereof, with the reasons therefor, shall be forwarded by the

warden to the Director of Corrections.”21 The Federal

Bureau of Prisons, too, has mandated relatively humane con

ditions for segregated confinement.22 See also, AMERICAN

CORRECTIONAL ASSOCIATION, MANUAL OF COR

RECTIONAL STANDARDS 414-15 (3d ed. 1966).

The aforementioned developments underscore the stark

fact that judicial intervention to protect the paramount

federal constitutional rights of prisoners to be treated as

human beings, as opposed to animals, has been necessary,

stitutional infirmity. See Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571 (8th Cir.

1968), where the Arkansas practice of whipping prisoners, as a dis

ciplinary measure, was held to run afoul of the Eighth Amendment,

notwithstanding the promulgation of safeguards. In an opinion by

Circuit Judge, now Justice, Blackmun, the Court of Appeals stated.

“The strap’s use, irrespective of any precautionary conditions which

may be imposed, offends contemporary concepts of decency and

human dignity and precepts of civilization which we profess to

possess; and . . . also violates those standards of good conscience and

fundamental fairness enunciated by this court. . . . Id., at 579.

21P.L. 1971, Chapter 397 (June 4, 1971), Amending Title 34,

§ 709, Rev. Stat.

22U.S. Bureau of Prisons, Policy Statement 7400.5, app. A, at 2

(Nov. 28, 1966) provides in part:

“The quarters used for segregation shall be well ventilated,

adequately lighted, appropriately heated and maintained in

a sanitary condition at all times. . . . All inmates shall be

admitted to segregation (after thorough search for contra

band) dressed in normal institution clothing and shall be

furnished a mattress and bedding. In no circumstances shall

an inmate be segregated without clothing except when

prescribed by the Chief Medical Officer for medical or

psychiatric reasons.. . . [Segregated inmates shall be fed

three times a day on the standard ration and menu of the

day for the institution. . . . Segregated inmates shall have

the same opportunities to maintain the level of personal

hygiene available to all other inmates. . . . ”

17

not only to provide individual redress,23 but also to get pri

son officials moving to attain minimum constitutional

standards in practices, facilities and services. E.g. Holt v.

Sarver, 309 F. Supp. 362, 385 (E.D. Ark.),affd, 4 4 ^ F.2d

(8th Cir. May 5, 1971); Jones v. Witttffflerg, 323

F.Supp. 93 (N.D. Ohio 1971).24 It appears that the so-called

“hands o ff’ doctrine,25 under which the courts, including

the Seventh Circuit below, granted prison officials a virtual

“immunity from judicial scrutiny led to a tradition of law

lessness in the corrections phase of the criminal process.”26

It is, therefore, imperative that the courts cease to ignore

valid claims by prisoners of unconstitutional treatment,

which threaten their life and what little liberty they possess.

“Although it might, indeed, be the easier course to

dismiss this amended complaint as to these defend

ants, we cannot flinch from our clear responsibility

to protect rights secured by the Federal Constitu

tion.”27

2 3 In view of the coercive effects of confinement in a punishment

cell under unsanitary and degrading conditions, which this Court

found in Brooks v. Florida, supra, the granting of affirmative relief

from such treatment may operate, not only to enforce the Eighth

Amendment, but also to protect a prisoner, who is also a potential

accused, against forced self-incrimination. Cf. Screws v. United States,

325 U.S. 91 (1945); United States v. Jones, 207 F .2d 185 (5th Cir.

1953).

24In finding the conditions in the Toledo jail to be unconstitu

tionally cruel, the District Court there said: “The cruelty is a refined

sort, much more comparable to the Chinese water torture than to

such crudities as breaking on the wheel.” 323 F.Supp., at 99.

25 See, Note, Beyond the Ken o f the Courts: A Critique o f Judicial

Refusal to Review the Complaints o f Convicts, 72 Yale L.J. 506

(1963).

26Turner, Establishing the Rule o f Law in Prisons: A Manual For

Prisoners’ Rights Litigation, 23 Stan. L. Rev. 473 (Feb. 1971).

27Inmates of the Cook County Jail v. Tierney, No. 68 C 504 (N.D.

111. Aug. 28, 1968, Hoffman, J.)

18

As this Court appropriately observed in McNeese v. Board

o f Education, 373 U.S. 668, 675 n. 6 (1963):

“We yet like to believe that wherever the federal

courts sit, human rights under the federal Constitu

tion are always a proper subject for adjudication.”

This case should, therefore, be remanded to the District

Court28 for the purpose of developing the record more fully,

so that it can be determined whether Haines was actually

subjected by prison officials to “excessive” or “unnecessary-

cruelty”, in violation of Eighth Amendment standards.

II.

PETITIONER WAS UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DEPRIVED

OF PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS OF LAW IN THE

PRISON DISCIPLINARY PROCEEDINGS.

“ ‘[Wjithin the limits of practicability’ . . . a state must

afford to all individuals a meaningful opportunity to be

heard if it is to fulfill the promise of the Due Process Clause.”

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371, 379 (1971) (emphasis

supplied). In Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254, 262-63

(1970), this Court said:

“The extent to which procedural due process must

be afforded the recipient is influenced by the extent

to which he may be ‘condemned to suffer grievous

loss’ . . . and depends upon whether the recipient’s

interest in avoiding that loss outweighs the govern

mental interest in summary adjudication. . . .’

28In view of the fact that neither the District Court nor the Court

of Appeals reached the question of how far along the chain of admin

istrative command liability extends, petitioner has not briefed that

issue here. However, on remand, that matter would be appropriate

for inquiry. See generally, Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167,187 (1961):

“Section [1983] should be read against the background of tort

liability that makes a man responsible for the natural consequences of

his actions.” See also, Joseph v. Rowlen, 402 F.2d 367, 370 (7th

Cir. 1968) (“good faith” no defense to arrest without probable

cause).

19

[Consideration of what procedures due process may

require under any given set of circumstances must

begin with a determination of the precise nature of

the government function involved as well as of the

private interest that has been affected by govern

mental action.’”

Many years ago, this Court observed, in an analogous

context:

“Clearly the end and aim of an appearance before

the court must be to enable an accused proba

tioner to explain away the accusation. . . . This does

not mean that he may insist upon a trial in any strict

sense. . . . It does mean that there shall be an inquiry

so fitted in its range to the needs of the occasion as

to justify the conclusion that discretion has not been

abused by the failure of the inquisitor to carry the

probe deeper.”29

The lower federal courts, which have been presented with

claims for procedural due process in prison disciplinary pro

ceedings, where substantial deprivations such as solitary

confinement or loss of parole eligibility or good time are to

be visited upon a prisoner, have adopted a similar approach.

See, Sostre v. McGinnis, AA't- F.2d (2d Cir. Feb.

24, 1971) (facts should be “rationally determined” and

prisoner should be “afforded a reasonable opportunity to

explain his actions”); United States ex rel. Campbell v. Pate,

401 F.2d 55, 57 (7th Cir. 1968) (“the relevant facts. . . must

not be . . . capriciously or unreliably determined.”); Nolan

29Escoe v. Zerbst, 295 U.S. 490, 493 (1935). See also, Mempa v.

Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967). In an opinion by former Justice Clark,

sitting as a Circuit Judge, the Court of Appeals, in Hahn v. Burke,

430 F.2d 100, 104 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U .S ._____

(Apr. 26, 1971), held that the Due Process Clause guarantees to state

probationers a “reasonable opportunity to explain away the accusa

tion.” Accord, Goolsby v. Gagnon, 322 F. Supp. 460, 464 (E.D. Wis.

1971), Bransted v. Schmidt, 324 F. Supp. 1232, 1236 (W.D. Wis.

1971), and State ex rel. Johnson v. Cady, 185 N.W.2d 306 (Wis.

1971) (State parolees entitled to the same “reasonable opportunity

to explain away the accusation”).

20

v. Scafati, 430 F.2d 548 (1st Cir. 1970) (“sufficient safe

guards” necessary where punishment “sufficiently great”);

Carothers v. Follette, 314 F. Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970)

(“an opportunity to present evidence before a relatively

objective tribunal” is required); Morris v. Travisono, 310 F.

Supp. 857 (D.R.I. 1970) (consent decree embodying wide

range of procedural safeguards).30

On its face, it might appear that Haines was afforded an

opportunity to explain his actions. A careful examination

of the underlying circumstances, however, reveals that the

choice was illusory, and that he was effectively precluded

from presenting his substantial claim of self-defense.31

Where, as here, the disciplinary infraction charged also

constitutes a prosecutable offense,32 an inmate who elects

to discuss the matter with prison authorities risks possible

self-incrimination.33 On the other hand, if he elects to stand

on his constitutional right to remain silent, and he is

unrepresented, then he is precluded from explaining his

30See also, Federal Bureau of Prisons, Policy Statement No. 7400.6

(Dec. 1, 1966); Missouri State Penitentiary Rules and Procedures,

Personnel Information Pamphlet pp.1-7; President’s Commission on

Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, Task Force Report:

Corrections 86 (1967); American Law Institute, Model Penal Code,

Article 304.7(2) (Proposed official draft 1962).

31 111- Rev. Stat., ch. 38 §§7-1, 7-13; United States ex rel. Hancock

v. Pate, 223 F. Supp. 202 (N.D. 111. 1963).

32I11. Rev. Stat., ch. 38 § 12-1 (assault), § 12-3 (battery).

33I11. Rev. Stat., ch. 108 § 118 provides in pertinent part: “When

any crime is committed within any division or part of the penitentiary

system by any person confined therein, cognizance thereof shall be

taken by any court of the county wherein such division or part is

situated having jurisdiction over the particular class of offenses to

which such crime belongs. Such court shall try and punish the person

charged with such crime in the same manner and subject to the same

rules and limitations as charged with crime in such county.” A

prisoner’s fear of potential prosecution for crimes committed in

prison cannot be considered speculative. See, e.g., People ex rel.

Conn. v. Randolph, 35 111. 2d 24, 219 N.E.2d 337 (1966).

21

actions. His dilemma is even worse than the normal

Miranda34 situation, where the accused loses nothing by

remaining silent.

It may be true, as a matter of law, that any statements

Haines would have made under those coercive circumstances,

and without prior admonitions as to his constitutional rights

concerning counsel and self-incrimination, would have been

inadmissible in any future criminal proceeding based upon

the conduct for which he was being interrogated. See,

Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1967);Melson v. Sard,

402 F.2d 653 (D.C. Cir. 1968) (relying upon Simmons v.

United States, 390 U.S. 377, 394 (1968)); Mathis v. United

States, 391 U.S. 1 (1967).34 35

However, absent an assurance that his statements could

not be used against him, it cannot be assumed that Haines

was aware of any implicit “use immunity”36 he would enjoy

if criminal charges were brought against him. Cf. Gardner

v. Broderick, 392 U.S. 273, 278-79 (1968).

34Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

35 See also, People v. Dorado, 62 Cal. 2d 338, 398 F.2d 361, 42

Cal. Rptr. 169, cert, denied, 381 U.S. 937 (1965); Blyden v. Hogan,

320 F. Supp. 513 (S.D. N.Y. 1970); Clutchette v. Procunier, No.

C-70-2497 AJZ (N.D. Cal. June 21, 1971); Opinion of New York

Attorney General, 8 Cr. L. Rptr. 2486 (Feb. 11, 1971) (Miranda

warnings required in prison disciplinary proceedings where misconduct

constitutes a crime); United States Bureau of Prisons, Policy State

ment 2001.1 (Feb. 19, 1968) (requires warning of rights, including

counsel and protection against self-incrimination).

36If this Court eventually holds that “transactional immunity” ,

which was never offered to Haines, is constitutionally required, then

Haines had even further justification for refusing to waive his privilege

against compelled self-incrimination. See generally, Piccirillo v. New

York, 400 U.S. 548, 562 (1971) (Brennan J. dissenting); In Re Korman,

_____ F .2d______, 9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2161 (7th Cir. May 20, 1971); In

Re Kinoy Testimony, J Z £ F . Supp. 4 * 1 , 8 Cr. L. Rptr. 2327

(S.D. N.Y. Jan. 29, 1971); Counselman v. Hitchcock, 142 U.S. 547,

586 (1892).

22

Haines could have been afforded a realistic opportunity

to explain his actions, under a number of alternative

methods. The officials could have advised him that any

statements made by Haines in the prison disciplinary pro

ceedings would be inadmissible in any subsequent criminal

proceeding, thereby removing any legitimate fear of incrim

ination. Cf. Melson v. Sard, supra.31 Or, Haines could have

been afforded representation by another person,37 38 who

would be able to relate Haines’ version of the events in

question without the personal risk of incrimination.39 Or,

the officials could have investigated further and obtained

favorable information from inmate witness Orlando. Cf.,

Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14(1967)■, Giles v. Maryland,

386 U.S. 66 (1967).

Barred from any of these alternative protections, Haines

was effectively deprived of a meaningful opportunity,

guaranteed by due process, to present a valid defense to the

disciplinary charge, on the issues of both guilt and severity

of punishment. This case should, therefore, be remanded to

the District Court for a determination of the extent to which

Haines’ injuries, from confinement in the degrading punish

ment isolation cell for fifteen days, resulted from the denial

of fundamental procedural safeguards in the prison disci

plinary proceedings.40

37But see, Note 36, supra.

38See, Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967) (counsel); United

States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218, 238 n. 27 (1967) (counsel substitute);

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969) (inmate legal assistance);

Morris v. Travisono, 310 F. Supp. 857, 872 (D.R.I. 1970) (staff

member advocate).

39Clutchette v. Procunier, supra; cf., McGautha v. California,_____

U .S ._____ , 39 U.S. L. Week 4529, 4540 n.20 (May 3, 1971).

40Haines also has apparently claimed that his punishment of

solitary confinement cell and demotion to “C” grade was based in

part upon his refusal to discuss the shovel incident with officials.

However, he may not constitutionally be subjected to such a drastic

penalty for refusal to waive his constitutional privilege against com-

23

CONCLUSION

When the Courts summarily close their doors to valid

prisoners’ claims of violations of their paramount federal

constitutional rights, involving extreme maltreatment and

procedural unfairness, a climate is created in which horren

dous at^yfes are permitted and encouraged to flourish in the

nation’s penal institutions, with calamitous results for the

rehabilitative process. We do not suggest that the federal

courts should be prime movers in the growing prison reform

movement. However, where prisoners are subjected to hard

core inhuman treatment, and are denied fundamental pro

cedural safeguards, which deprivations are not justified by

the necessities of prison discipline and security, and which

infringe upon constitutionally protected liberties, then the

courts must exercise their remedial jurisdiction, clearly con

ferred by Congress, to establish a due process minimum

level of human dignity and procedural fairness, below which

the states may not go.

pelled self-incrimination. Cf., Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511 (1967);

Gardner v. Broderick, 392 U.S. 273 (1968); Uniformed Sanitation

Men’s Association v. Commissioner, 392 U.S. 280 (1968). It cannot

fairly be said that Haines “waived” his fundamental right to remain

silent after acknowledging that he had hit Doherty with the shovel.

As this Court observed, in Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 445

(1966):

“The mere fact that he may have answered some questions

or volunteered some statements on his own does not deprive

him of the right to refrain from answering any further

inquiries until he has consulted with an attorney and there

after consents to be questioned.”

Since the defendants did not provide a statement of their reasons for

their harsh disciplinary action against Haines, compare, Goldberg v.

Kelly, 397 U.S. 254, 271 (1970), it must be assumed for present

purposes, until clarified upon remand, that Haines was penalized for

an impermissible reason. Cf., Clay (Ali) v. United States,_____ U.S.

_____ , 39 U.S. L. Week 4873, 4875 (June 28, 1971).

24

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment below should be

reversed, and the case remanded to the District Court for

further proceedings.

Respectfully submitted,

Stanley A. Bass

Attorney for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

William B. Turner

Alice Daniel

Max Stern

July, 1971

la

APPENDIX A

Gentlemen:

The questions which appear below deal with the use and

conditions of solitary confinement in state prisons. This

information will be presented to the United States Supreme

Court during an appeal scheduled for the Fall of this year.

Your answers, when compiled with those of the forty-nine

other states will enable the Court to view this important

issue from a national perspective. We will appreciate your

candid and prompt reply.

Thank you.

Steven Burton

Questions

A. State:______________________

B. Official Title of Answering Party:

1. Solitary confinement is presently used in our State

Prisons. Yes ( ) No ( )

2. Solitary cells are, lighted ( ) without light ( )

3. Prisoners in solitary are provided with: (check where

appropriate)

(a) bed ( ) (f) wash bowl ( )

(b) mattress ( ) (g) towel ( )

(c) running water ( ) (h) other elements of per-

(d) soap ( ) sonal hygiene ( )

(e) toilet ( ) (i) clothes ( )

Comment:

4. Prisoners in solitary receive

(a) psychiatric visit ( )

(b) physician visit ( )

(c) shave and shower—daily ( ); weekly ( );

none ( ); if other, please explain______

2a

(d) exercise or recreation daily ( ); weekly ( );

none ( ).

(e) regular diet ( ); limited diet ( ); bread and

water ( ).

5. Prisoners in solitary are permitted

(a) to communicate with other prisoners

(b) to receive mail

(c) to send mail

(d) to have reading material: Legal ( ) non-legal ( )

6. Maximum time spent in solitary

(a) 1 week ( ); 2 weeks ( ); a month ( );

unlimited ( ).

(b) requirement for release:______ ____________

7. Reasons for prisoner being sent to solitary

1 ._____________________________________

2. ____________________________________________________________

3 ._____________________________________

Please Return to: Steven Burton

142 Baker Hill Road

Great Neck, N.Y. 11023

\\