Plaintiffs' Opening Argument

Public Court Documents

September 8, 1998

5 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Opening Argument, 1998. 04e00dac-a146-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2743c447-bc44-4dcc-887a-b32db6765dab/plaintiffs-opening-argument. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

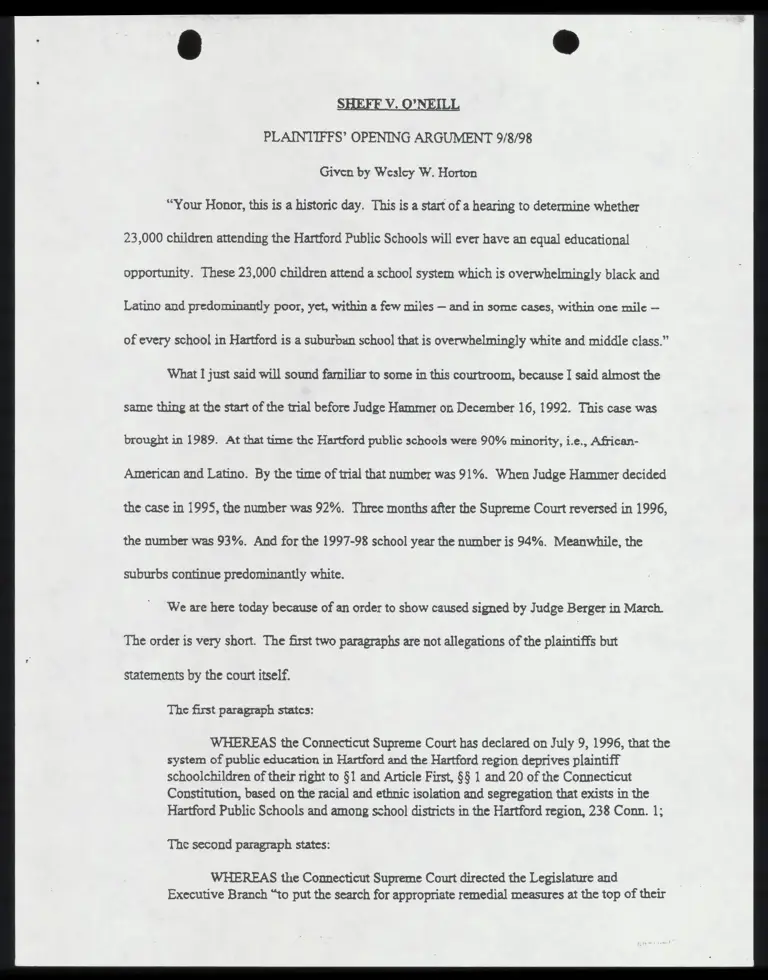

S V.Q’

PLAINTIFFS’ OPENING ARGUMENT 9/8/98

Given by Wesley W. Horton

“Your Honor, this is a historic day. This is a start of a hearing to determine whether

23,000 children attending the Hartford Public Schools will ever have an equal educational

opportunity. These 23,000 children attend a school system which is overwhelmingly black and

Latino and predominantly poor, yet, within a few miles — and in some cases, within one mile —

of every school in Hartford is a suburban school that is overwhelmingly white and middle class.”

What I just said will sound familiar to some in this courtroom, because I said almost the

same thing at the start of the trial before Judge Hammer on December 16, 1992. This case was

brought in 1989. At that time the Hartford public schools were 90% minority, i.e., African-

American and Latino. By the time of trial that number was 91%. When Judge Hammer decided

the case in 1995, the number was 92%. Three months after the Supreme Court reversed in 1996,

the number was 93%. And for the 1997-98 school year the number is 94%. Meanwhile, the

suburbs continue predominantly white.

We are here today because of an order to show caused signed by Judge Berger in March.

The order is very short. The first two paragraphs are not allegations of the plaintiffs but

statements by the court itself.

The first paragraph states:

WHEREAS the Connecticut Supreme Court has declared on July 9, 1996, that the

system of public education in Hartford and the Hartford region deprives plaintiff

schoolchildren of their right to §1 and Article First, §§ 1 and 20 of the Connecticut

Constitution, based on the racial and ethnic isolation and segregation that exists in the

Hartford Public Schools and among school districts in the Hartford region, 238 Conn. 1;

The second paragraph states:

WHEREAS the Connecticut Supreme Court directed the Legislature and

Executive Branch “to put the search for appropriate remedial measures at the top of their

- i T

respective agendas” and to implement appropriate remedies “in time to make a difference

before another generation of children suffers the consequences of a segregated public

school education.” 238 Conn. at 46;

The third paragraph contains the plaintiffs’ claim that:

WHEREAS the plaintiffs claim that Connecticut General Assembly has failed to

adopt any meaningful legislation to redress the constitutional violation identified by the

Supreme court and that defendants Governor and the State Board of Education have

failed to adopt any meaningful measures that will alleviate the racial and ethnic isolation

in the Hartford public schools and racial and ethnic segregation among schools in the

Hartford region, and therefore moved that his Court order compliance with the Supreme

Court's ruling;

Therefore, the defendants are ordered to appear to show cause, and I tlh: as to whether

there has been compliance with the Supreme Court’s ruling.

This hearing has been bifurcated, which means that, on a finding of noncompliance, there

will be a further hearing on the remedy.

In terms of burden of proof, we believe that we have the burden of showing that the

disparities in racial isolation are continuing, whereupon the burden shifts to the defendants to

justify their response to the Supreme Court mandate.

It will be quickly apparent from just the documentary evidence that we have proved the

disparities are continuing and indeed are getting worse. Because of that, and because our |

principal witnesses are qualified to talk not only about the disparities but also about the state’s

response, we intend in our case in chief to anticipate some of the state’s responses. I think this

will make for a more coherent trial.

Now, in response to the Supreme Court’s mandate that the Legislative and Executive

branches put the issue of appropriate remedial measures for racial and ethnic isolation at the top

of their representative agendas, the state claims that virtually everything it has done about

education in the past two years has been a response 10 the Sheff decision. The state claims to

have done scme things to address the disparities in resources. The state apparently hopes that

more resources will trickle down to less racial isolation.

Even assuming arguendo that the state has donc something about resources, Your Honor

will hear from three nationally respected experts who will testify for the plaintiffs that addressing

resources is only one totally insufficient component of addressing racial isolation. Our experts

will also show that the state has done very little to address racial and ethnic isolation. The state’s:

philosophy since the Supreme Court decision - as it was for a gencration before then - is best

summarized in what I expect will be the opinion of its principal witness in this hearing, Dr.

Christine Rossell, that the less the state does about racial isolation the more it will accomplish.

Indeed, she thinks the state should be praised for its minimal and non-comprehensive response to

the Supreme Court’s order.

Judge Aurigemma, you may think that my last statement is a typical lawyer’s

exaggeration, but I suggest that after you hear from Dr. Rossell and the state's other witnesses,

you will see that it is not an exaggeration. My statement will also be borne out by the evidence |

of what the state has done since July 1996. Just to give Your Honor the basic outline,

immediately after the Supreme Court mandate came down in July 1996, the Governor appointed

a Commission to report in early 1997 on how to respond to the Supreme Court mandate.

However, the Commission had one hand tied behind its back because it was supposed to consider

only purely voluntary solutions. The plaintiffs presented some suggested detailed guidelines to

the Commission. The Commission filed a report in early 1997. It made some modest

recommendations, but, unlike our guidelines, it said absolutely nothing about setting a standard

of what constitutes racial isolation in either the city of Hartford or in the suburbs. It said nothing

about adopting measures to determine if recommended programs will in fact reduce isolation.

And it said nothing about setting a goal to reduce racial isolation by any particular number or

percentage or by any particular date, much less explaining how any such goal would ever be

rcached. Nor does it significantly address how bilingual education will be involved in

desegregation planning. In short, the Commission simply finessed the tough issues.

The Legislature then responded to the Supreme Court order in the Spring of 1997 with

Public Act 97-290. The tipoff that this statute also does not address the tough issues is the dle:

“An Act Enhancing Educational Choices and Opportunities.” The title does not mention racial

isolation. The statute does enact some modest initiatives, and you'll hear evidence from the state

about how a lot of little things add up to big progress. In fact a lot of little things add up to little

progress. In terms of number of students involved on a full-time basis, these initiatives are a

drop in the bucket. Once again, I’m not exaggerating. The state is talking about a few hundred

Hartford students participating full-time in these new programs, but Hartford has 23,000

students. Furthermore, the evidence will show that some of these initiatives, such as some of the

Charter schools, are not going to reduce racial isolation at all.

Because of these problems, the state will set up a smokescreen to try to divert your

attention from full-time to part-time and extracurricular activities so that the numbers will look

better than they really are. In the depositions, one state witness went so far as to say that an all-

black football team playing an all-white football team constitutes an integrating experience.

The statute also provides for the State Board of Education to develop a 5-year plan to

reduce racial isolation. The first report was produced in February 1998, but it did not talk about

racial isolation at all. It focused on resources and promised a report on racial isolation in January

1999. According to the deposition of one state official in April, work on the second report had

not cven started at that time. But even if the state board is now diligently working on that report,

don’t hold your breath, because §4 of the 1997 statute limits the 5-year plan to “(1) Include

methods for significantly reducing over a five-year period any disparities among school districts

in terms of resources, staff, programs and student lcarning,[note that there is no mention of racial

isolation] (2) provide for monitoring by the Department of Education of the progress made in

reducing such disparities, and (3) include pronosals for minority staff recruitment. ....”

So the statute does not authorize the State Board to address the core issues concerning

racial isolation, which, as I icdicated, would include setting standards for what constitutes racial

isolation and setting goals for reducing city and suburban racial isolation by a certain percentage,

by a certain date, proposing how these goals will be accomplished, and deciding how bilingual

education fits into these goals. Nor does it authorize the State Board to compel local boards to

set goals or to compel them to make any particular efforts to reach those goals if they do set

them. Nor does the statute address what the Supreme Court found to be the prime culprit: the

statutory requirement that students generally must attend schools in their own school district.

Your Honor, the state does not have any plan, much less a comprehensive plan, to

eliminate racial isolation in the Hartford Public Schools or in the suburbs. It doesn’t even have a

plan to reduce racial isolation. And it’s not going to have a real plan to reduce racial isolation

‘unless this court orders it.

Dr. Rossell will tell you that slow but steady wins the race. No, it doesn’t. It loses the

race. That’s what thc Supreme Court thought when it ordered the state to put remedial measures

at the top of its agenda before another generation of students suffers. That's what the Supreme

Court thought when it said, “Every passing day denies these children their constitutional right to

a substantially equal educational opportunity. Every passing day shortchanges these children in

their ability to learn to contribute to their own well-being and to that of this state and nation.”