Robinson v Shelby Country Board of Education Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1970

35 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Robinson v Shelby Country Board of Education Reply Brief for Appellants, 1970. f9abfda4-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/276bcc0f-9a26-48b9-947c-a9964ff5a9ee/robinson-v-shelby-country-board-of-education-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

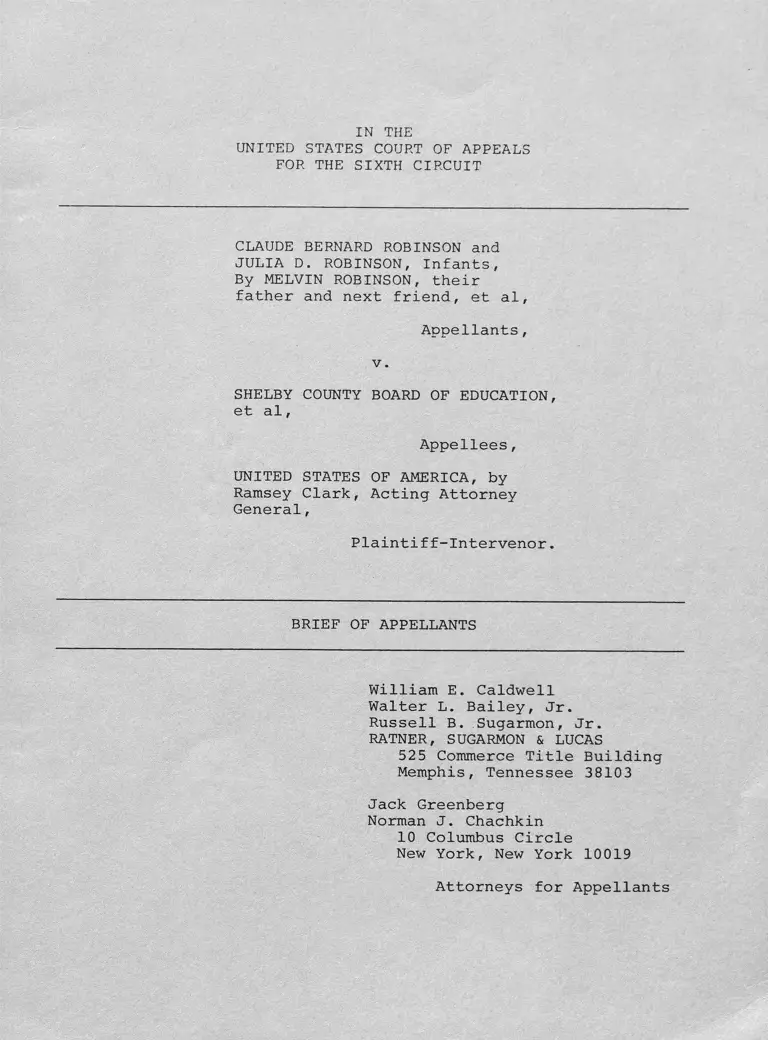

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

CLAUDE BERNARD ROBINSON and

JULIA D. ROBINSON, Infants,

By MELVIN ROBINSON, their

father and next friend, et al,

Appellants,

v.

SHELBY COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al,

Appellees,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, by

Ramsey Clark, Acting Attorney

General,

Plaintiff-Intervenor.

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

William E. Caldwell

Walter L. Bailey, Jr.

Russell B. Sugarmon, Jr.

RATNER, SUGARMON & LUCAS

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Jack Greenberg

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF C A S E S ....................... i

ISSUE ON APPEAL ......................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .................................. 2

A. HISTORY OF THE C A S E .................. 2

B. STATEMENT OF F A C T S ....................... . . . 12

ARGUMENT................................................... 18

CONCLUSION................... 27

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 29

TABLE OF CASES

Pages

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ.,

396 U.S. 19 (1969) ................... 2, 9, 11, 18, 19, 20, 27

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) . . 20

Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk,

397 F .2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968);

#14,544 (4th Cir. June 22, 1970) . . . 22, 23, 27

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.Supp. 776,

(E.D. S.C. 1955) ............. 18, 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483,

(1954); 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ........ 2, 22, 24, 25, 27

Brunson v. Bd. of Trustees of Sch. Dist.

No. 1 of Clarendon County, S.C.,

No. 14,571 (4th Cir. June 5, 1970)

(en banc) ........................... 23-26

Cato v. Parham, 297 F.Supo. 403,

(E.D. Ark. 1969) . ." ................. 22

Christian v. Bd. of Ed. of Strong School

District #83 of Union County,

#ED 68-C-5 (W.D. Ark. 1969) ........ 20-21

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) . . . . 8

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock,

No. 19795 (8th Cir. May 13, 1970) . . 18-19

Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 419 F.2d

1387 (6th Cir. 1969) ................. 19

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City,

Civil No. 9452 (W.D. Okla. Aug. 8,

1969) aff'd. 396 U.S. 296 (1969) . . . 20-21

Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. 393 (1856) . 24, 25

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) . . . . . 4, 6, 7, 11, 18, 20, 21

Green v. School Bd. of the City of

Roanoke, Va., No. 14,335 (4th Cir.

June 17, 1970) ....................... 19

x

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier

County, 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969 . . 21

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate

School Dist., 409 F.2d 682 (5th

Cir.) cert, denied, 396 U.S. 940

(1969) ............................... 22

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of

Ed. of Nashville and Davidson

County, Tennessee, Nos. 2094 and

2956 (M.D. Tenn. July 16, 1970) . . . . 19-20, 22

Kemp v. Beasley, No. 19,782 (8th Cir.

Mar. 17, 1970) .......... .. 18, 23

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver,

303 F.Supp. 279 (D. Colo.) stay

vacated, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969) ........ 22

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of

Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) . . . . . 4, 6, 7, 8, 18

Northcross v. Board of Educ., 397 U.S. 232

(1970) ......................... .. . . 9, 11, 19, 20

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) . . 24, 27

Raney v. Board of Educ., 391 U.S. 443 (1968) 4, 6, 7, 18

Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson

County, Civ. No. 3107 (M.D. Tenn.,

Oct. 16, 1969) ....................... 28

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ.,

Civ. No. 68-1438-R (C.D. Cal.,

March 12, 1970) ....................... 22

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklinburg Bd. of

Educ., 300 F.Su d d . 1358 (W.D. N.C.

1969 ); No. 14,5i~5 (4th Cir. May 26,

1970), cert, granted, U.S.

(1970) ............................... 22 , 27

United States v. Greenwood Municipal

Separate School Dist., 406 F.2d

1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ................. 22

11

. 22

United States v. Indianola Municipal

Separate School Dist., 410 F.2d 626

(5th Cir. 1969) .....................

United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Educ., 372 F .2d 836 (5th Cir.);

aff'd. 380 F .2d 385 (1966), cert,

denied sub nom. 389 U.S. 840 (1967) .

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., No.

29237 (5th Cir. Mar. 6, 1970) . . . .

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526

(1963) ............. . . . . . . . .

Whitley v. Wilson City Bd. of Educ.,

No. 14,517 (4th Cir. May 26, 1970)

iii

. 21

. 22

. 8

. 19

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

CLAUDE BERNARD ROBINSON and

JULIA D. ROBINSON, Infants,

By MELVIN ROBINSON, their

father and next friend, et al,

Appellants,

v.

SHELBY COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al,

Appellees,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, by

Ramsey Clark, Acting Attorney

General,

Plaintiff-Intervenor.

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

ISSUE ON APPEAL

Whether a School Board, which formerly operated a state-

imposed dual school system, meets its affirmative constitutional

obligation to desegregate that system by merely drawing zone

lines "not gerrymandered to preserve segregation."

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Appellants (plaintiffs below), who represent the class of

black school children in Shelby County, Tennessee, appeal from an

order of the United States District Court for the Western District

of Tennessee, Western Division, entered on May 7, 1970, implement

ing the District Court's opinion of April 6, 1970* approving the

latest desegregation plan of the appellee Board of Education

(defendant below), which plan was filed pursuant to a prior order

of that same court entered October 1, 1969. Said opinion of

April 6th, if allowed to stand, will directly contradict the

concepts and mandates of the decisions of the Supreme Court from

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1964) ; 349 U.S. 294

(1955) through Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) .

A. HISTORY OF THE CASE

The original suit in this case was filed by the private

plaintiffs on June 12, 1963. Subsequently, the District Court

entered an order approving the School Board's dual overlapping

school zones and the transfer provision provided therewith.

On May 6, 1966, the United States intervened pursuant to

Section 902 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000h-2,

and filed a Motion for Supplemental Relief alleging that the

continued existence of the dual, overlapping school zones consti

tuted a violation of the Constitution of the United States. The

motion alleged that the defendant Board maintained dual zones and

* The opinion is reported in 311 F.Supp. at 97, and appears in the

Appendix to this brief at A. 17.

2

students were assigned to particular schools on the basis of

their race.

A consent decree filed May 20, 1966 directed the operation

of the Shelby County schools under a modified freedom of choice

plan. The district was divided by the decree into five "attend

ance areas" and each child was required to make an annual choice

of one of the schools within the area where he resided. For the

following school terms, the Shelby County schools were operated

under essentially the same freedom of choice plan of pupil assign

ment. However, an amendment to the plan of March 23, 1967, made

at the request of the School Board, established single zone

boundaries for three predominantly white high schools serving

grades nine through twelve but retained a freedom of choice for

all other pupils.

The plan adopted May 20, 1966 did not result in any substan

tial progress in desegregation of the system. The plaintiff-

intervenor, the United States of America, in January, 1967, filed

a Motion for Civil Contempt as a result of the failure of the

defendants to comply with the consent decree, which resulted in

an order of the court, January 19, 1967, finding the defendants

in violation of the order of May 20, 1967, and ordering the

achievement of racial balance in the faculties as a partial remedy

for this intransigence.

The appellee School Board later filed a motion seeking relief

from the faculty desegregation requirements of the January 19,

1967 order. The District Court denied any relief at that time.

3

On June 27, 1968, the plaintiffs filed a Motion for Further

Relief in light of Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), Raney v. Board of Education of the

Gould School District, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) and Monroe v. Board

of Commissioners of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) , asking that the

defendants be required to institute a plan of desegregation based

on unitary geographic zones, consolidation of schools, or pairing.

The United States filed a similar motion.

On July 19, 1968, the District Court entered a Memorandum

Decision and Order (A. 1-6 ) requiring the defendant Board to

prepare a plan "for integration of pupils, to be effective begin

ning with the school year 1969-70, to the end that thereafter, to

the extent feasible, no school in the system will be identifiable

as a 'white' or 'Negro1 school." (A. 6 )•— The court

ordered the Board to adopt a plan based on unitary geographic

zones, or consolidation or pairing of schools, to the effect that

"no school will be recognizable as 'white' or 'Negro'" (A. 4 )

However, the court denied plaintiff-appellants' request for this

relief for the 1968-69 school year on the ground that there was

not sufficient time remaining to effect such a change. The

court's order, however, made clear the affirmative responsibility

1/The court held, and we submit, properly so, that under Green,

Raney and Monroe "integration of pupils and faculty is the legally

required end result ... " (A. 2 ). With respect to faculty,

the court required that "[b]y the beginning of the 1969-70 school

year, the proportion of white to Negro teachers in each school

must not vary more than 10% from the proportion of white to Negro

teachers in the entire system." (A. 6 )•

4

of the defendant Board of Education to comply with the new order

for the 1969-70 school term. And on August 15, 1968, the District

Court entered an order requiring the Board to submit a plan for

the 1969-70 school year that would "to the extent feasible, main

tain in each school operated by the Shelby County system a ratio

of Negro to white students within 10% ... of the ratio of Negro

to white students in the system as a whole."

During the 1968-69 school term, less than five percent (5%)

of the Negro students in the Shelby County system attended schools

with white students. (A. 8 ).

On January 15, 1969, the defendant Board of Education filed

its new plan of desegregation purporting to comply with the

District Court's July 19, 1968 order. Subsequently, a Motion to

Intervene in the suit was filed by white parents which resulted

in a hearing before the District Court and permission for them to

intervene in the cause.

The court had previously ordered the Board to consult with

the Title IV Consulting Center at the University of Tennessee in

the preparation of its plan. During the period following the

submission by the Board of its plan, it was necessary for the

plaintiffs to file a motion and have a hearing before the defend

ant Board would submit its plan to the Title IV Center for evalua

tion .

On April 11, 1969, the court ordered the report, evaluation

and critique by the Title IV Center filed in the record of this

5

cause. On that same day, plaintiffs filed their objections to

the Board's plan. The hearing on the submitted plans commenced

on May 12 and terminated on May 16, 1969.

On May 26, 1969, the District Court entered its "Opinion

and Order." (A. 7-10 ). The court found that during the then-

approaching 1969-70 school year, "a total of about 34,912 pupils

..., of which approximately 72% will be white and 28% will be

Negro," (A. 7 ) would be in attendance in the defendant Shelby

County School System. The court concluded that the defendant

Board's proposed desegregation plan, which would increase the

percentage of pupils in desegregated schools "to around 50%"

(A. 8 ), but which provided for racially-dual, overlapping

zones, would "not, as a long-term plan, meet the requirements of

Green, Raney and Monroe, 391 U.S. 430, 443 and 450." (A. 9 ).

Nevertheless, the court found that "it would be proper to approve

operation of the defendant Board's plan during the coming year

[1969-70]." (A. 9 ). The court required, however, "that

the proposed plan as filed and as developed at the hearing will

also allow pupil transfers from majority to minority situations,

that the defendant Board will give reasonable notice of such

options, and that the defendant Board will furnish transportation

to pupils who choose such options provided the distances involved

2 /are sufficient to otherwise entitle them to transportation."-7

(A. 10 ) .

2/Under Tennessee law (Tenn. Code Ann. §49-2201) pupils who live

more than 1 1/2 miles from their school are entitled to state-

funded transportation. County Boards may provide transportation,

(continued)

6

The court stated that it would later file a full opinion setting

forth "precisely why the defendant Board's plan does not meet

the requirements of ... [the Green, Raney and Monroe decisions]

and indicate specifically what is required." (A. 9 ).

On October 1, 1969, the District Court filed its "Addendum

to Opinion and Order of May 26, 1969." (A. 11-16 ). The court

pointed out that " [u]nder the Board's proposed plan, some schools

would remain entirely Negro, and some white pupils would attend

schools that are farther from their homes than are other schools,

attended only by Negroes, which have appropriate grade levels

for them." (A. 12 ). The court noted that the Board had

forwarded two defenses to this segregated situation, one of them

being "that it was not feasible ... to obtain the proportion of

whites to Negroes prescribed." (Id.) Responded the court to

this defense: "This, of course, represents a misunderstanding of

the import of our order. Simply because the prescribed proportion

cannot feasibly be obtained is not an excuse, under our order or

the Supreme Court's opinions, for not effecting the desegregation

that is feasible." (A. 12-13 ).

2/(concluded)without the benefit of state funds, in their discretion

to pupils who live closer to their school than 1 1/2 miles. The law

permits a one-way transit time of 1 1/2 hours to transport a pupil

to his school. (Tenn. Code Ann. §49-2203). The "Annual Statistical

Report" of the Tennessee State Department of Education shows that

for the school year ending in June, 1969, there were 19,971 Shelby

County pupils enrolled for transportation at an operating cost of

$652,204.71, or a per capita cost of $35.39 for the school term.

Of this cost the State paid $311,946.00, or $15.62 per capita.

7

The other defense offered by the Board was "somewhat more

complicated" (A. 13 ), but simply stated it was "white flight"

and "community hostility."!/ The Board argued "that if a school

is desegregated in such a manner that white pupils are in a

minority or even in a slight majority, the school will gradually

but certainly become an all-Negro school due to the departure of

white pupils ... [but] if the school is desegregated in such a

manner that it has a substantial majority of white pupils, it

will stabilize and remain a desegregated school." (A. 13 ).

The Board further rationalized that "in the not-too-distant future"

enough whites would move into areas where Negroes now live "to

allow the desegregation of schools there with a substantial

majority of white pupils ... [but] if this [District] Court now

requires white pupils in these areas to attend predominantly Negro

schools, not only will these white pupils desert these schools ...

but also the development of white suburbs in these areas will not

occur." (Id.) In response to this unconstitutional justification

for segregated public education, the District Court, citing

Monroe, held that "the fact that white pupils will either move or

attend private schools is irrelevant. In short, the law requires

that we present these white pupils with the options of attending

these schools, or moving, or attending private schools." (A. 14 ).

The court required the defendant Board to file on January 15, 1970,

3/Cf. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958); Watson v. City of Memphis,

373 U.S. 526,"534 (1963); Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs. of Jackson,

Tenn., 391 U.S. 450, 459 (1968).

8

a new plan of desegregation in accordance with the addendum.

The defendant Board filed appeals from both the May 26, 1969

and the October 1, 1969 opinions of the District Court. On

November 14, 1969, following the Supreme Court’s October decision

in Alexander v. Holmes County Board, 396 U.S. 19 (1969) , plaintiffs

filed in the District Court a "Motion to Require Adoption of

Unitary System Now." On December 15, 1969, the District Court

entered a memorandum decision and order (A. ) denying the

motion on the basis that Alexander was inapplicable where "there

has already been accomplished great progress in desegregation of

pupils and faculty and, more importantly, there is no alternative

plan in existence."i/ The plaintiffs, while the Board's appeals

were still pending in this court, filed an appeal from the District

Court's denial of the Alexander motion.5./

Plaintiffs' appeal and defendants' appeals were consolidated

and argued before this court after new desegregation plans had

been submitted to the District Court (as requested) on January 15,

1970, by the Board and the Title IV Center. On the motion of

plaintiffs, this court, on June 25, 1970 (A. 33-36 ), dismissed

4/Cf. Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232 (1970) , where

thi~~Supreme Court reversed a similar finding by a panel of this

court regarding the Memphis City Schools.

5/In the opinion appealed from, the District Court incorrectly

states in a footnote (A. 23 ) that plaintiffs "did not perfect

their appeal."

9

both appeals because the 1969-70 school year had ended and the

District Court had before it new plans of desegregation and had

entered the opinion and order which is the subject of the present

appeal.

As noted above, on January 15, 1970, the Board and the Title

IV Center filed separate desegregation plans. The plaintiffs,

after receiving a ten day extension, adopted the Center's plan.

On February 3, the Center submitted several amendments to its

plan. A hearing was held February 10-12 and subsequently the

Center, defendants and the United States submitted post-trial

"position letters" to the court. On April 6, 1970, the District

Court entered the opinion appealed from, which opinion, in one

giant step backward, approved, with one minor e x c e p t i o n t h e

Board's proposal as to zoning on the theory that "a school system

that has honestly drawn unitary geographical zone lines, that is,

zones not gerrymandered to preserve segregation, and that severely

limits transfers ... is not a ’dual system' with respect to

pupils." (A. 25 ). The plan is to be implemented by September

1970 for grades 1-11, with grade 12 frozen in current attendance

patterns.

The District Court justified its departure from (indeed, its

reversal of) its previous opinions by concluding that "it is not

for this court to determine the wisdom or lack of wisdom of a

6/The minor exception involved the racial gerrymandering of the

zone line separating E. /•.. Harrold and Millington Central elementary

schools. (A. 23 )•

particular proposal of the defendant Board; it is for us to

determine only whether or not it is constitutional." (A. 26 ) ! /

The court's new vision of the Fourteenth Amendment test of consti

tutionality requires only that zone lines "not [be] gerrymandered

to preserve segreaation." (A. 25 )£/ The court further con

cluded that under this new "unitary" zoning plan "no pupil will

be allowed to attend a school outside the zone in which the pupil

lives" except for very limited "administrative or educational

reasons." (A. 31 ) <L / * 9

7/Despite the court's deferral to the Board's "wisdom," the court

still refused to approve the Board's willingness to keep the

Capleville 78 and Eads elementary schools open. (A. 27 ).

8/The court arrives at this new test (and it is indeed "new", as

It appears in no post-Green decision of any other court that we

are aware of) by leapfrogging its previous interpretations regard

ing the affirmative duty of the defendant Board to dismantle its

dual system, and coming to rest with this court's short-lived

opinion in Northcross (January 12, 1970) and the Chief Justice's

concurring remarks IH the Northcross reversal (397 U.S. 232, (March

9, 1970)) to the effect that the Supreme Court has not decided that

"racial balance" is required. The Chief Justice's concurring

opinion, however, does not support the District Court's refusal to

require desegregation. Furthermore, as pointed out in the Argument,

infra, plaintiffs have not and do not seek racial balance - just

substantial desegregation of every school. The District Court does

quote the Alexander definition of "unitary" (A. 23-24 ), but to

what effect we are unsure, as the "unitary" test arrived at by the

District Court cannot be even remotely related to the Alexander

mandate.

9/This is actually a reversal of the previous order which provided

for majority-to-minority transfers for the purpose of furthering

desegregation. (A. 10 ).

11

B. STATEMENT OF FACTS

The court below found that under the approved plan the

Shelby County school system would be composed of 30 elementary

schools and 8 secondary schools. (A. 26-27 ). According to

the "Elementary Projection Data" filed with the court on January

15, 1970, the 30 elementary schools will enroll 15,677 students,

of which 5,379 (34.3%) are black. The "High School Projection

Data - Grade 9," filed with the court at the same time, shows

a projection of 1,625 ninth grade students, of which 546 (33.6%)

are black.!£/ One elementary school (Brownsville) is 100% white,

and one elementary school (White's Chapel) is 100% black.

(A. 26 ). Of the thirty elementary schools, six (Barret's

Chapel, Capleville, Harrold, Mt. Pisgah, Shadowlawn and White's

Chapel) are over 75% black, in a system which is only 34% black;

and six (Brownsville, Coleman, Egypt, Millington South, Riverdale

and Raleigh Bartlett Meadows) are 90% or more white, in a system

which is only 66% white. Of the 8 high schools!!/ (on the basis

10/Although there is testimony in the record concerning enrollment

fTgures, the projection data referred to in the text is the only

documentary evidence in the record. The 10, 11 and 12 grade data

was not presented by the Board, since the Board's plan contemplated

that 10, 11 and 12 grade students would continue to attend the

school previously attended. The court limited this exception to

grade 12, however. (A. '30 ). The data presented in the projec

tion data for grades 1-9 is sufficiently accurate to present a true

picture of the plan approved below, the limited modifications made

by the court being relatively insignificant.

11/There are 9 schools listed in the "High School Projection Data -

Grade 9," but the court ordered one of them (Woodstock) closed.

(A. 27 ) .

12

of the 9th grade data), two (Barret's Chapel and Mt. Pisgah)

are 65% or more black and one (Raleigh Egypt) is 87% white, in

a system which is 66% white and 34% black.

There are some significant differences between the Board's

plan, as approved by the District Court, and the Title IV Center's

plan, which was rejected by the District Court. These differences

are set forth in the following table:

13

T

Title IV

Center Plan

T

Reason for

DifferenceSchool - Capacity

Board-Court

____Order Plan

Grades W B Grades W B

Harrold 780 1-8 42

Millington-Central 585* 1-8 679

b .

Coro Lake

White's Chapel

485

485

1-8

1-8

342

0

c .Caplevilie-Shelby

Germantown

1245

1040

1-8

1-8

50

466

250 292** 1-4 or 456 236 692

859**

5-8

180 1-4 or 456 236 692

5-8

151 493*** 1-4 275 265 540

382 382 5-8 275 265 540

199 249 1-8 96 211 307

396 862 1-8 420 385 805

*Additional capacity available at the adjacent Millington High

School plant.

**The court ordered a slight modification in the Board's proposed

plan but as it affected only about 50 whites living in a ’trailer

park who could move to another park across the road to shift

zones.

***The apparent numerical discrepancy is caused by the Center's

inclusion of some 200 odd students (all white) who live in these

zones but will attend city schools under the Board's proposal.

There are several available portables to solve the capacity

problem.

Paired

Paired

Change

caused by

Center's

zoning

approxi

mately 4 6

white and

12 Negro

students

to a

school

over 3

miles

closer to

their

homes.

These differences arise largely in those areas of Shelby County

containing the highest percentages of black residents, which were

previously contained in the defendant Board's dual overlapping

zones. The differences between the Center's plan and the Board's

plan are the product of the Center's utilization of such valid

techniques as contiguous zoning or pairing designed to maximize

the desegregated learning experiences for an optimum number of

pupils.

In proposing the plan approved by the District Court, the

defendant Board premised its plan on the erroneous interpretation

of the District Court's previous orders as meaning that desegrega

tion is irrelevant. (Tr. 215). The system's Superintendent,

George Barnes, testified that a unitary system was one in which

students were assigned to the school closest to their residence.

(Tr. 180) Furthermore, according to Superintendent Barnes,

"the degree of desegregation (doesn't] enter into unitary zoning."

(Tr. 362). The Board's plan was further founded on the theory

12/The Board's plan does not bear out this premise, however, as an

examination of the map exhibits clearly demonstrates that in prac

tically every zone there are pupils assigned to one school who

live closer to another school in an adjacent zone. For example,

the pupils living in the southwest portion of the Germantown

elementary zone live much closer to the Capleville school. Students

in the western portion of the Mt. Pisgah zone must proceed some 3

miles further to school after passing within a block of the Cordova

school. Students living within a mile of Millington East attend

school at Barret's Chapel some six miles away. And so on ... .

15

that desegregation would not work unless each school had at least

60-65% white student bodies. (Tr. 244-45). Superintendent Barnes

stated that a major effort in the plan was to keep predominantly

white schools wherever possible. (Tr. 351). The Board was thus

preoccupied with "accommodating the sentiments" of the community.

(Tr. 2.44 , 282-83). The Board's attitude by the statement of the

Superintendent that "this area [Barret's Chapel, Bolton] has

maintained two schools for forty years or more, and there is no

reason why it can't do it for another year ... " (Tr. 198).

The District Court noted one example of racial gerrymandering,

i.e., the zone line separating Harrold and Millington Central

elementaries. (A. 28 ). Dr. Myer, the Title IV Center's

expert noted at least one other zone line in the Board's plan

which separated a black and a white neighborhood: the Riverdale-

Shadowlawn boundary line. (Tr. 411, 469). With further reference

to the Riverdale zone, it is interesting to note that this zone

is in effect a non-contiguous zone, although both the Board and

the District Court purport to disapprove this method of zoning.

The northwest corner of the Riverdale zone is completely cut off

from the much larger southeastern portion (which contains the

school) by the Shelby County Penal Farm which spans the entire

breadth of the Riverdale zone and which contains no through roads,

thereby requiring students in the northwest corner to be trans

ported around the Penal Farm through other zones to get to the

Riverdale school. Long transportation routes are not unusual in

16

the defendant system, however. Last school year, under the free

choice plan, the Board transported, for instance, a number of

white pupils 14 or 15 miles to avoid attending a black school.

(Tr. 165-66). The system has also been busing black students

long distances for a number of years to avoid having them attend

white schools. (Tr. 304).

Dr. Myer testified that the Center's plan with respect to

pairing Harrold and Millington (see chart, page 14, supra) would

actually involve a decrease in the amount of busing then going

on. (Tr. 472-73). The District Court agreed with Dr. Myer that

in the northeastern part of the County desegregation could be

accomplished without increasing the amount of transportation

already being provided.

17

ARGUMENT

In its May and October, 1969, opinions, the District Court

properly recognized that the Supreme Court decisions in Green, Raney

and Monroe had buried the Briggs v. Elliott 13/ dictum forever.

Nevertheless, in the opinion appealed from, rendered on April 6,

1970, the District Court resurrects the Briggs dictum, injects new

life into that ill-conceived constitutional doctrine, and turns it

loose in Shelby County, Tennessee. The only intervening occurrence

between the District Court's October 1969 opinion and its April, 1970

opinion was Alexander v. Holmes County Board, 396 U.S. 19 (1969),

which lends absolutely no support to the District Court's new

constitutional view that the Fourteenth Amendment only requires

that a former dual system draw zone lines "not gerrymandered to

preserve segregation." Alexander was not a retrenchment of the

Green doctrine; rather, Alexander gave Green the mandate of

urgency.

Under Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 442

(1968) , the obligation of every school system is to establish

"a system without a 'white' scool and a 'Negro' school, but just

schools." The objective is a school system without schools

which are racially identifiable. Kemp v. Beasley, No. 19,782

(8th Cir. Mar. 17, 1970) (per Blackmun, J.); Clark v. Board of

13/ 132 F. Supp. 776, 777 (E.D.S.C. 1955): "all that is decided

Tby Brown ], is that a state may not deny to any person the right

to attend any school that it maintains."

18

Education of Little Rock, No. 19,795 (8th Cir. May 13, 1970) (en

banc); Adams v. Mathews, 403 F. 2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968); Green

v. School Bd. of City of Roanoke, Ho. 14,335 (4th Cir. June 17,

1970); Whitley v. Wilson City Bd. of Educ., No, 14,517 (4th Cir.

May 26, 1970). The District Court, however, reached a contrary

conclusion and held that former dual school systems had no

affirmative duty to desegregate its schools. The District Court

relied on this Court's opinion in Northcross v. Board of Education

of City of Memphis, (January 12, 1970), which opinion was reversed

by the Supreme Court (397 U.S. 232), on March 9, 1970. This

Court's opinion in Northcross relied heavily on Deal v .

Cincinnati Board of Education , 419 f . 2d 1387. We submit however

that the Deal approach to the Fourtheenth Amendment mandate is

no longer valid in view of the Supreme Court's decisions in

Northcross and Alexander. We find the reasoning of Circuit Judge

Miller's opinion in Kelly v. Metropolitan County Board of Education

of Nashville, Davidson County, Nos. 2094, 2956 (M.D. Tenn., July

16, 1970; pupil portion of order stayed) (Slip Op. at 5-4), sound

and compelling:

In Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F.2d

1387 (6th Cir. 1969) , the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals

stated its adherence to a principle similar to that

set forth in Briggs v. Elliott, supra, to the effect

that there is no affirmative duty to integrate. See

419 F.2d at 1390. The Sixth Circuit's position in

Deal, however, seems to have been undermined by the

opinion of the Supreme Court in Northcross v. Board

of Education of Memphis, Tennessee, City Schools,

397 U.S. TT2 (1970), a more recent case also arising

in the Sixth Circuit. After granting a writ of

certiorari, the Supreme Court in Northcross declared

19

that the Court of Appeals erred in holding in

applicable the rule of Alexander v. Holmes County-

Board of Education, Supra. In view of the fact that

Alexander and its predecessor, Green, clearly stand

for the proposition that a school board has an affirm

ative duty to integrate, there is strong reason to

infer that the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

would not now express the view that there exists no

constitutional duty on the part of school authorities

to integrate schools. Rather, it is the clear message

of Alexander and Green that school boards everywhere

are charged with the affirmative duty to establish a

unitary school system at the "earliest practicable

date." Horthcross v. Board of Education of the

Memphis, Tennessee, City Schools, supra,'' at 235.

Yet, and in the face of its previous opinions of May and October,

1969, the District Court, ruling on a former dual school system,

held: "a school system that has honestly drawn unitary geographical

zone lines, that is, zones not gerrymandered to preserve segregation,

and which severely Units transfers..., is not a 'dual system' with

respect to pupils." This statement of the law is a clear reversal

of the previous opinions and orders entered by the District Court.

Thus the District Court has joined the School Board in creating

and maintaining segregated public education in Shelby County,

Tennessee, notwithstanding the fact that federally-sanctioned

segregation is proscribed by the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment to the United States Constitution. Bolling v. Sharpe,

347 U.S. 497 (1954).

In Alexander, supra, the Supreme Court ordered all dual

school systems to "begin immediately to operate as unitary school

systems within which no person is to be effectively excluded from

any school because of race or color." The District Court has

clearly misinterpreted the Alexander mandate. As Judge Oren Harris

said in an order entered on December 15, 1969, following the Alexande

20

decision: "Although the record discloses that no student of the

Strong School District is 'excluded' from either of its two schools,

the District was and is effectively operating dual schools."

Christian v. Board of Education of Strong School District Ho. 83

of Union County, No. E.D. 68-C-5 (W.D. Ark. 1969) (emphasis added).

Like the Strong School District, the Shelby County School system

is effectively operating dual schools. Any other approach ignores

the affirmative duty requirement to disestablish every vestige of

school segregation set forth in Green v. County School Board of New

Kent County, supra, and ignores also the en banc decisions of the

Fifth Circuit in Jefferson I: "The only adequate redress for a

previously overt system-wide policy of segregation directed against

Negroes as a collective entity is a system-wide policy of integration.

United States v, Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836,

869 (5th Cir.) aff'd. on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (1966),

cert, denied sub non, Caddo Parish School Bd. v. United States,

389 U.S. 840 (1967) (emphasis in original).

Thus a school district may not permissibly continue

its past discriminatory assignment policies by the present appli

cation of "neutral" standards which do not achieve the result of

dismantling the dual system. This is true whether the method used

is free choice, transfer or geographic zoning. Otherwise "the

equal protection clause would have little meaning. Such a position

'would allow a state to evade its constitutional responsibility by

carve-outs of small units.'" Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier

County, 410 F .2d 920, 924 (8th Cir. 1969). See Dowell v. School

21

Bd. of Oklahoma City, Civ. No. 9452 (W.D. Okla., Aug. 8, 1969),

aff'd. 396 U.S. 296 (1969); Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver,

303 F.Supp. 279, 289 (D. Colo.), stay vacated, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969)

(Hr. Justice Brennan, in Chambers); Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal

Separate School Dist., supra; United States v. Greenwood Municipal

Separate School Dist., supra; Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd.,

No. 29237 (5th Cir., March 6, 1970); United States v. Indianola

Municipal Separate School Dist., supra; Cato v. Parham, 297 F.Supp.

403, 409-10 (E.D. Ark. 1969); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklinburg Bd.

of Educ., 300 F.Supp. 1358 (W.D. N.C. 1969) ; Spangler v. Pasadena

City Bd. of Edue., Civ. No. 68-1438-R (C.D. Cal, March 12, 1970).

In the latest decision in Brewer v. The School Board of

the City of Norfolk, Va., #14,544 (4th Cir. June 22, 1970) the court

rejected a contiguous zoning plan although it produced more de

segregation than the Shelby County plan, and required the use of:

"reasonable methods of desegregation, including

rezoning, pairing, grouping, school consolidation,

and transportation." (slip op. p. 10).

As Judge Miller said in Kelly, supra: "No concept of

zoning, including the concept of 'neighborhood school attendance

zones,' is constitutionally defensible if employed in such a way

as to minimize pupil integration of schools."

In 1954 the Supreme Court held in Brown v. Board of

Education that "Separate educational facilities are inherently

unequal." Yet Shelby County did nothing and even as late as the

1968-1969 school year less than five per cent of the pupils in

the system attended desegregated schools. The present record,

22

heardly measures up to the constitutional requirement that dual

school systems affirmatively disestablish their segregated pattern

of pupil assignments. That mandate does not permit twelve racially

identifiable elementary schools and three racially identifiable

secondary schools, (which schools were segregated in 1968 and in

1954). Now does the mandate permit a school system and a District

Court to avoid the use of such valid educational technics as pairing

(such as those extremely feasible proposals made by the Title IV

Center) on the ground that "it is not for this court to determine

the wisdom or lack of wisdom of a particular proposal of the defend

ant Board." Nor is it proper for a school board which already

transports the great majority of its pupils to school to fail to

utilize such busing to disestablish racially identifiable pattern of

pupil assignments. See Judge (now Justice) Blackraun's opinion in

Kemp v. Beasley, supra.

The defendant Board strongly urged upon the District Court

that integration would not work unless a desegregated school con

sisted of a white majority. For all that appears the District Court

succumbs to this argument. A similar argument was urged on the

Fourth Circuit in Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, supra,

and in Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District No. 1 of

Clarendon County, South Carolina, No. 14,571 (4th Cir. June 5, 1970).

The concurring opinion of Judge Sobeloff in Brunson deserves special

consideration, as it meets that issue head-on and finds the School

Board's "white majority" proposal wholly lacking in constitutionality

23

There have always been those who believed that

segregation of the races in schools was sound

educational policy, but since Brown their reason

ing has not been permitted to withstand the

constitutional command. When the underpinnings

of the white majority proposal are exposed, they

are seen to constitute a direct attack on the

roots of the Brown decision.

* * * *

It would, I am sure, astonish the Brov/n court

to learn that 16 years later ... it was seriously

being contended that desegregation might not be

required insofar as it threatened to impair the

majority white situation. My conviction comes

not only from the reading of the Brov/n opinion

itself but from a conspectus of over 100 years

of constitutuional adjudication.

Judge Sobeloff began his consideration of the constitutional

history underlying Brown with an analysis of Dred Scott v. Sanford,

60 U.S. 393 (1856), which opinion "offered a justification for

the slave system and al1 its incidents" and "which is at once the low

mark and the focal point of the constitutional history of the rights

of black Americans." Judge Sobeloff then notes that although " [the]

Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were the explicit

and total repudiation of the Dred Scott teaching," the Supreme

Court later found in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) , "no

violation of the Constitution in State-enforced ’separate but

equal' facilities."

"The significance of Brown," says Judge Sobeloff, "must

be appraised against this background. Certainly Brown had to do

with the equalization of educational opportunity; but it stands

for much more. Brown articulated the truth that Plessy chose to

disregard: that relegation of blacks to separate facilities

24

represents a declaration by the state that they are inferior and

not to be associated with. By condemning the practice as 'inherently

unequal,1 the Court, at long last, expunged the constitutional

principle of black inferiority and white supremacy introduced by

Dred Scott, and ordered the dismantling of the''impassible barrier1

upheld by that case." The 1 invidious nature" of the white majority

thesis, says Judge Sobeloff, "at bottom ... rests on the generalizati*

that, educationally speaking, white pupils are somehow better or

more desirable than black pupils. This premise leads to the next

proposition, that association with white pupils helps the blacks and

so long as whites predominate does not harm the white children.

But once the number of whites approaches minority, then association

with inferior black children hurts the whites and, because there

are not enough of the superior whites to go around, does not

appreciably help the blacks." Noting that this white majority

thesis is "founded upon the concept that white children are a

precious resource which should be fairly apportioned ... [and]

because black children will be improved by association with their

betters" Judge Sobeloff points out that "[c]ertainly it is hoped

that under integration members of each race will benefit from

unfettered contact with their peers. But school segregation is

forbidden simply because its perpetuation is a living insult to

the black children and immeasurably taints the education they receive

This is the precise lesson of Brown. Were a court to adopt the

[white majority] rationale it would do explicitly what complusory

segregation laws did inplicity."

In response to the dissenting opinion fear of "white

25

flight," Judge Suboleff reached the same conclusion that the

District Court in this case reached in its October, 1969 opinion

(now abandoned): "I, too, am dismayed that the remaining white

pupils in the Clarendon County Schools may well now leave. But

the road to integration is served neither by covert capitulation

nor by overt compromise, such as adoption of a schedule of 'optimal

mixing.'"

26

CONCLUSION

After which they consult Precedents,

adjourn the Cause, from Time to Time

and in Ten, Twenty, or Thirty Years

come to an Issue.

Gulliver's Travels

Jonathan Swift

This suit was originally filed in 1963, but in 1970,

after seven years of litigation (and 16 years after Brown) plaintiffs

come to this Court seeking a unitary school system now. The question

presented here is whether the Shelby County, Tennessee, school

system, with the aid of the United States District Court, can con

tinue its oath of allegiance to Plessy v. Ferguson in the face of

Brown and Alexander. We submit that it cannot, and for the foregoing

reasons plaintiffs respectfully raove the Court to set this cause

down for an expedited hearing, reverse the judgment of the District

Court and remand the case with the following order:

1. This case shall receive the highest priority.

2. The District Court shall forthwith order the

defendant school board to prepare and submit

within 15 days a plan for the elimination of

the racial identity of the student bodies of

each school in the defendant system for the

remainder of 1970-71 school year. The plan

shall utilize, wherever necessary, every

method of desegregation, including rezoning with

or without satellite zones, pairing, grouping,

school consolidation and transportation. See:

Swann v. Charlotte-Ilecklenberg Board of Ed

ucation , No. 14,E>15 (4th Cir. May 26, HT777)

(Slip Op, p.20, 23, 25); Brewer v. School

Board of City of Norfolk, supra.

27

3. Pending approval of a new plan, all new

construction or additions to buildings

shall be enjoined pending a reevaluation

in accordance with the new plan and the

Board's affirmative duty. Sloan v. Tenth

School District of Wilson County, Civ.

No. 3107 (M.D. Tenn. Oct. 16 , 1969) .

4. Upon the filing of the Board's plan,

plaintiffs shall have five days in which

to file objections.

5. The District Court shall hold such hear

ings as may be necessary on any objections

and shall in conformance with this order

require the implementation of the plan

meeting these requirements no later than

the start of the second semester of the

current school year.

Respectfully submitted

William E. Caldwell

Walter L. Bailey, Jr.

Russell B. Sugarmon, Jr.

RATNER, SUGARMON & LUCAS

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Jack Greenberg

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

28

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing Brief of

Appellants was served on Mr. Lee Winchester, Jr., Attorney for

Appellees by placing the same in the United States mail, postage

prepaid, on the 8th day of October, 1970, addressed to him at his

office, Suite 3200 100 Worth Main Building, Memphis, Tennessee

38104.

/jJtM**, £ C M uj£j2?

William E. Caldwell

29