Kirkland v. The New York State Department of Correctional Services Brief for Intervenors-Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kirkland v. The New York State Department of Correctional Services Brief for Intervenors-Appellants, 1974. 3cdd9417-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/276dab03-0622-4f59-9935-47d7e3a46e82/kirkland-v-the-new-york-state-department-of-correctional-services-brief-for-intervenors-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

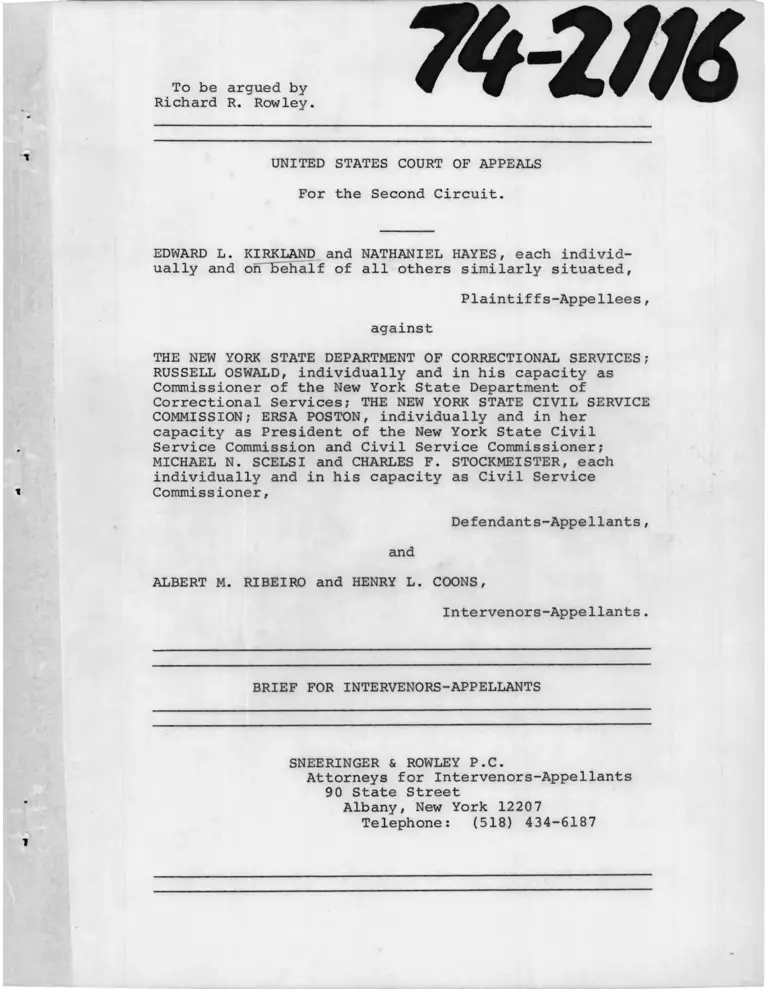

To be argued by

Richard R. Rowley. 74-2M

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For the Second Circuit.

EDWARD L. KIRKLAND and NATHANIEL HAYES, each individ

ually and on behalf of all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

against

THE NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES;

RUSSELL OSWALD, individually and in his capacity as

Commissioner of the New York State Department of

Correctional Services; THE NEW YORK STATE CIVIL SERVICE

COMMISSION; ERSA POSTON, individually and in her

capacity as President of the New York State Civil

. Service Commission and Civil Service Commissioner;

MICHAEL N. SCELSI and CHARLES F. STOCKMEISTER, each

individually and in his capacity as Civil Service

■* Commissioner,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

ALBERT M. RIBEIRO and HENRY L. COONS,

Intervenors-Appellants.

BRIEF FOR INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

SNEERINGER & ROWLEY P.C.

Attorneys for Intervenors-Appellants

90 State Street

Albany, New York 12207

Telephone; (518) 434-6187

j

RR/gc

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

STATEMENT 1

ISSUES 3

FACTS........................................... 3

POINT I. INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS AND THE CLASS

WHICH THEY SEEK TO REPRESENT ARE INDISPEN

SABLE PARTIES AND THE FAILURE TO JOIN THEM

IN THE ACTION BEFORE THE TRIAL DEPRIVES

THEM OF THEIR PROPERTY RIGHTS WITHOUT DUE

PROCESS OF LAW AND THE COMPLAINT SHOULD BE

DISMISSED................................ 17

POINT II. THE DISTRICT COURT SHOULD HAVE ALLOWED

APPOINTMENTS FROM THE ELIGIBLE LIST CREATED

BY EXAMINATION 34-944 TO BECOME PERMANENT

AND SHOULD NOT HAVE DIRECTED THE USE OF A

.ONE TO THREE PREFERENTIAL APPOINTMENT

RATIO IN EITHER INTERIM OR FINAL APPOINT

MENT PROCEDURES.......................... 27

CONCLUSION 49

EXHIBIT 1

EXHIBIT 2

EXHIBIT 3

*

CASES

Page

Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 94 S. Ct. 2963

at 2975 .................................... 18 , 20

Baird v. People's Bank & Trust Co., 120 F .2d

1001 (3rd Cir. 1941)........................ 22

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535, 91 S. Ct. 1586. . 18

Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564, 92 S.Ct 18, 19

2701........................................ 20

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371, 91 S. Ct.. 18

Bridgport Guardians, Inc. v. Members of Bridge

port Civil Service Commission, 482 F .2d 1333,

(1973)...................................... 27, 28

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F .2d 725 (1971). . . . . 27, 29

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 27, 37

(1972)....................................... 38

Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67, 92 S. Ct.

1983......................................... 18

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254, 90 S. Ct.

1011......................................... 18

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964). . . 29

Milliken v. Bradley, 42 U.S. Law Week 5249,

July 25, 1974 .............................. 29

Missouri, Kansas, Texas Railroad v. Brotherhood

of Railway and Steamship Clerks, 188 F.2d 302,

305-306 (7th Cir. 1951)..................... 23

Order of R. R. Telegraphers v. New Orleans,

Texas and Mexican Railway, 229 F .2d 559

(8th Cir.) cert, den'd., 350 U.S. 997 (1956).i 23

19

22

21

18

22

26

28

28

18

20

22

28

CASES

Perry v. Sindermann, 408 U.S. 593, 92 S. Ct.

2694 ......................................

Roos v. Texas Co., 23 F .2d 171 (2nd Cir. 1927)

cert, den'd., 2770 U.S. 587 (1928) ........

Shields v. Barrow, 58 U.S. (17 How.) 130

(1855) at pg. 139..........................

Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U.S. 337,

89 S. Ct. 1820 ............................

United States v. Bank of New York & Trust Co.,

296 U.S. 463 (1936)........................

United States v. Elfer, 246 F.2d 941 (9th Cir.

1957).......................................

U.S. v. Wood, Wire, and Metal Lathers Inter

national Union, Local 46, 471 F.2d 408,

cert, den'd. 412 U.S. 939 , (1973)..........

Vulcan Society of New York City Fire Depart

ment, Inc. v. The Civil Service Commission,

490 F .2d 387, (1973) ......................

Wisconsin v. Constantineau, 400 U.S. 433,

91 S. Ct. 507..............................

Wolff v. McDonnell, U.S. , 94 S. Ct.

2963 at 2975 ..............................

Young v. Powell, 179 F .2d 147 (5th Cir.),

cert, den'd., 339 U.S. 948 (1950)..........

Rios v. Steamfitters Local 638, F.2d ,

8 FEP Cases 293 (June 1974)................

STATUTES

Page

N.Y. Civil Service Law, § 4 0 .................... 4

N.Y. Civil Service Law, § 4 4 .................. * . 4

N.Y. Civil Service LawT, § 5 2 ..................... 4

N.Y. Civil Service Law, §52(10) 5

N.Y. Civil Service Law, § 5 6 ..................... 5

N.Y. Civil Service Law, § 6 1 ..................... 4

N.Y. Civil Service Law, § 6 5 ..................... 5

N.Y. Civil Service Law, § 7 5 ..................... 6

New York State Constitution, §6, Art. V . . . . 4, 30

Rules and Regulations of the New York State

Civil Service Commission, 4 N.Y.C.R.R. 4.5,

4 N.Y.C.R.R. 4.5(3) .......................... 6

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 19 . . .10, 25

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 19(a). .10, 11

21

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 19(b). . . 21

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 19(c). .10, 12

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 12(h). . . 25

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 21 . . . . 25

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

EDWARD L. KIRKLAND and NATHANIEL HAYES,

each individually and on behalf of all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-against-

THE NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL

SERVICES; RUSSELL OSWALD, individually and in his

capacity as Commissioner of the New York State

Department of Correctional Services; THE NEW YORK

STATE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION; ERSA POSTON, indivi

dually and in her capacity as Preisdent of the

New York State Civil Service Commission and Civil

Service Commissioner; MICHAEL N. SCELSI and

CHARLES F. STOCKMEISTER, each individually and in

his capacity as Civil Service Commissioner,

Defendants-AppeHants ,

-and-

ALBERT M. RIBEIRO and HENRY L. COONS,

Intervenors-Appellants.

BRIEF FOR INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

Statement

Intervenors-appellants (herein Ribeiro) appeal from

the judgment and order of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York rendered after a trial

without a jury before Hon. Morris E. Lasker, District Judge,

granting judgment to the plaintiffs adjudging New York State

Civil Service Examination 34-944 for the position of Correc

tion Sergeant to be invalid as violating the Constitution

of the United States. The order of the District Court

enjoined the State of New York and named State officials

from making any permanent or provisional appointments to the

position of Correction Sergeant based upon the eligible list

promulgated as a result of said examination, directed

the said defendants to develop a lawful, nondiscriminatory

selection procedure pursuant to specified guidelines, per

mitted interim provisional appointments to be made only

upon application to the Court and pursuant to a quota

whereby at least one of every four promotions pursuant to

the interim procedures shall be from members of the minority

groups involved and continued such quota system following

the development of a revised selection procedure until the

combined percentage of blacks and hispanics in the ranks of

Correction Sergeant equaled the percentage thereof in the ranks

of Correction Officers. The District Court retained juris

diction of the proceeding for such period as might be

necessary to supervise the decree and further proceedings

thereunder and to determine the reasonable value of the

plaintiffs' attorneys' services.

-2-

ISSUES

1. Did the failure to join indispensable parties

potentially deprive such parties of their property rights

without due process of law so as to require a dismissal

of the complaint?

2. Should the District Court have allowed

appointments from the eligible list promulgated from Exam

ination 34-944 and made prior to the entry of the decree

to become permanent?

3. Was the District Court correct in directing

the use of a one to three preferential appointment ratio

in both interim and final appointment procedures?

FACTS

All numbers in parenthesis refer to pages of the

Appendix or refer to exhibits of the parties and their

page numbers in the Appendix.

The facts which are relevant to this brief are

very simple. The position of Correction Sergeant is a

promotional position in the New York State Department of

Correction. The entry position is the job of Correction

Officer commonly referred to in former times as a Prison

Guard. Today there are many variations of the position of

Correction Officer serving in many State institutions

- 3 -

in addition to the traditional maximum security facilities.

A Correction Sergeant is essentially the first line

supervisor above a Correction Officer. Both of the

positions, that is Correction Officer and Correction

Sergeant, are in the classified service of the New York

State Civil Service as defined by Section 40 of the Civil

Service Law and both of the positions are in the

competitive class within the meaning of Section 44 of

the Civil Service Law of the State of New York.

Under Section 6, Article V of the New York State

Constitution such positions must be filled according to

merit and fitness ascertained by competitive examination

so far as practicable.

Section 52 of the Civil Service Law of the State

of New York describes in considerable detail the procedures

for conducting promotion examinations and provides in

part that as far as practicable vacancies in positions

in the competitive class shall be filled by promotion

from among persons holding competitive class positions in

a lower grade. After a Civil Service examination has

been administered an eligible list is established among

the applicants having passed the test including appropriate

credit for service in the Armed Forces and similar

position his provisional service shall be credited in

his permanent position.

A probationary appointee, whether in the entry

grade or in a promotional grade immediately upon appoint

ment obtains significant Civil Service rights. Under

the Rules and Regulations of the New York State Civil

Service Commission, 4 N.Y.C.R.R. 4.5, a probationary appoint

ment is for a specific period of time during which the

employee can not be dismissed except upon charges after

a due process type hearing, 4 N.Y.C.R.R. 4.5, New York

Civil Service Law §75. At the end of the probationary

term, the appointment becomes permanent unless probation

is continued up to a maximum specified period. At the end

of the initial or extended period of probation, the

appointment becomes permanent unless the performance of

the employee is not satisfactory in which case he can be

terminated, 4 N.Y.C.R.R. 4.5(3).

Upon exhaustion of the eligible list for Correction

Sergeants sometime in the Spring of 1972, the Department of

Correctional Services appointed a number of individual

Correction Officers as provisional Sergeants and communicated

to the New York State Department of Civil Service its need

for a new competitive examination to establish a new

-6-

eligible list for Correction Sergeants. The examination

was prepared and the notice of examination, plaintiffs'

exhibit 17 (A 1352) , indicates that only individuals with

service as Correction Hospital Senior Officer or Correction

Hospital Charge Officer or Correction Officer were eligible

to take the examination and that only those individuals

with three years of service in the subordinate positions

could be appointed. The examination was duly administered

on October 14, 1972 and an eligible list was promulgated

on March 15, 1973.

This action was commenced on April 10, 1973 and

a temporary restraining order was made and entered forth

with directing the defendants not to make permanent

appointments from the list and prohibiting the defendants

from terminating the provisional appointments of plaintiffs

or members of their class. Under this preliminary order

all provisional sergeants who had failed the examination

but did not belong to the class purportedly represented by

plaintiffs automatically reverted to the position of

Correction Officer. Among all of the provisional Sergeants

who failed the examination, only the named plaintiffs and

the several other black or hispanic provisional Sergeants

who failed the examination were held in the position of

-7-

provisional Sergeant.

The Record before this Court does not reveal the

comparative standing of the provisional Sergeants thus

retained in the promotional positions vis-a-vis other

minority applicants who took and failed the examination.

The Record does reveal that at least one minority candidate

the intervenor, Albert M. Ribeiro, is a minority citizen

who took and successfully passed the examination at a

high enough position on the list to be appointed.

The complaint alleges a class of plaintiffs of

approximately four hundred forty persons, and on its face

it is apparent that the defendants were aware of the name

and addresses of every one of the members of the class

since all of them were employed by the State of New York

at the time when they took the examination in issue. Any

of the individuals whose employment has been terminated

and are not on the State roles would seem to have

surrendered any interest which they might have in

appointment to the promotional position. Despite this

the plaintiffs allege in paragraph 2 (c) of their complaint

(A 9) that the number of persons makes joinder of all

class members impracticable.

The plaintiffs, as revealed by complaint paragraphs

11, 12 and 13 (A 17 - A 18), had extensive and detailed

-8-

knowledge of the eligible list and of the fact that

permanent appointments would be made beginning on

April 11, 1973. As early as April 4, 1973 the plaintiff

Hayes was aware that on April 12 the Department would

appoint ninety Sergeants from the eligible list (A 41)

and the plaintiff Kirkland would appear to have had

a copy of the eligible list early in April as shown by

paragraph 11 of his affidavit on the motion for a

temporary restraining order (A 47).

Attorney Deborah Greenberg's affidavit on the

same motion (A 51 - A 52) would seem to indicate that she

had studied the eligible list when she signed her affidavit

on April 10, 1973.

The Judge below at an early date recognized the

prejudice and impact upon the successful applicants who

were among the ninety appointees as is witnessed by the

provisions of his order dated April 11, 1973 particularly

the portions thereof appearing at A 62 - A 64. The same

order appears to be repeated at A 66 - A 68.

Neither of the intervenors, both successful

candidates on examination 34-944, were named as parties

defendant nor did the Court, the defendants or the

plaintiffs ever take any affirmative or formal steps

to notify these individuals or other individuals on the

-9-

eligible list of the pending litigation or their

opportunity to participate.

Rule 19 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

relates to the joinder of persons needed for a just

adjudication. Subdivision A describes the persons to

be joined if feasible. A simple awareness of the

property interest acquired by the intervenors and all

other named on the eligible list makes it obvious that they

fall squarely within the class of persons described in

Rule 19 (a). That Rule provides most explicitly with

respect to such persons:

"If he has not been so joined the

Court shall order that he be made a

party."

The Rule is not permissive, it is a mandate.

Furthermore, subdivision C of Rule 19 provides as follows:

"A pleading asserting a claim for

relief shall state the names, if known

to the pleader, of any persons described

in subdivision (a) (1) - (2) hereof who

are not joined, and the reasons why they

are not joined."

Nowhere in the complaint can one find the slightest

allegation as to the names of the successful applicants

on the eligible list or the reasons why they had not been

joined or an allegation that their names are unknown to

the plaintiffs.

There can be no doubt, particularly in view of the

striking failure of the plaintiffs to deny knowledge upon

-10-

RRR/js

the intervenors' motion for intervention, that the

plaintiffs were aware of the identity of the successful

applicants at the time when their law suit was commenced

and that the District Judge was perhaps aware of their

identity in the very first days of the action or, at the

very least was aware that there was an eligible list

containing the names of a substantial number of State

employees with an interest relating to the subject of the

action and so situated that the disposition of the action

in their absence might as a practical matter impair or

impede their ability to protect that interest. It seems

obvious that the District Judge continued to be acutely

aware of the conflict and he stated in his decision (A 153)

"The competing interests are vital

to the named parties, to other

individuals who may be affected by

the outcome and to the public at large.

Plaintiffs . . . efforts bring them

into conflict with those individuals

who passed the challenged examination

and have a vested interest in securing

the promotions which are rightfully

theirs if the examination is unheld.

For both groups, the outcome is critical

since it affects their ability to earn

a living by advancing in the profession

of their choice."

Nevertheless the learned District Judge not only

failed to comply with the mandate of Rule 19 (a) and

failed to require the plaintiffs in their complaint to

-11-

comply with the provisions of Rule 19 (c) but at an early

date in the litigation denied the application of other

interested parties to intervene in the proceeding. The

docket entries reproduced at pages A 2 - A 5 of the Record

do not appear to reveal the application to intervene filed

in June or July of 1973, however, there is an entry of

July 16, 1973 of an affidavit of Stanley L. Kantor, (an

Assitant Attorney General) in opposition to a motion to

intervene and a memorandum filed by the plaintiff on the

same day in opposition to an application for intervention

by white provisional Correction Sergeant Jackson. Attached

hereto marked Exhibit 2 is a copy of the Endorsement of the

District Judge denying the Jackson application for interven

tion. It is interesting to note the preoccupation of the

District Judge with expeditious determination of the

proceeding some three months after it was commenced in

sharp contrast to the lapse of approximately eight months

after the trial before the District Judge rendered his

decision.

Expeditious disposition of litigation is an

admirable goal, however, the attainment of that goal does

not take priority over the guarantees of due process.

-12-

On the trial the plaintiffs were not content to

rely solely upon the statistical variation for proof of

their prima facie case but called a number of witnesses.

The witnesses Young, Suggs, Hayes, Kimble, Kirkland,

Holman, O'Neil and Liburd were all Correction Officers

or provisional Sergeants. During their testimony they

all expressly or impliedly repeated the conclusions

voiced by Officer Young at A 284 - A 285 as follows:

"Q. Did you feel that that examina

tion was related to the skills and

abilities that you were using on that job?

A. I can't recall all of the

questions of the exam at this time.

I will say if there was any part

unrelated it was the comprehensive

part of the exam.

Q. What is the comprehensive

part?

A. The reading comprehensive part

of the exam.

Q. Would you state that that was

unrelated?

A. I would state that was unrelated."

During the examination of the witness Kimble

(A 437 - A 441) a similar line of question was pursued by

the plaintiffs. At page 440 the District Judge remarked

that such testimony "May be relevant to job relatedness".

-13-

RRR/gc

The plaintiffs called Dr. Richard Barrett

as a rebuttal witness. Dr. Barrett qualified as an

expert in testing and equal employment opportunity

litigation. Dr. Barrett has impressive credentials,

however, it would appear that his sole knowledge with

respect to the particular job in issue, Correction

Sergeant, is based upon his discussions with the attorneys

for the plaintiff, reading of largely unidentified

documents and one day spent at the correctional facility

at Greenhaven and attendance at Court (A 1107). During

his lone visit to a correctional institution he spent

about five hours inside of the prison and talked to

eight Sergeants (A 1108). By attendance at Court Dr. Barrett

apparently heard the testimony of the various Correction

Officers and provisional Sergeants called by the plaintiffs.

Nowhere in Dr. Barrett's testimony does it appear that he

has any prior experience with regard to correctional

institution type jobs, the closest being work that he has

done with certain police departments.

The ultimate issue in this case, so far as the

validity of the test is concerned, is the question of job

relatedness. The State's expert declined to testify that

the test was job related (A 1045 - A 1047) , however, the

plaintiffs expert Barrett testified (A 1132):

-14-

"X feel I can raise some questions

about the content validity but I don't

believe that I can state definitely as

a professional that it is or is not

content valid."

Dr. Barrett would go no further than expressing his

substantial doubts as to whether the test was valid (A 1131

- A 1133).

As though being aware of the inadequate sampling

of Dr. Barrett and the uncertainty of his opinion the

District Judge referred to the testimony involving the

job relatedness of some of the questions on the examination

(A 185 - A 186). Only two of the questions referred to

(A 778 - A 790 and A 1010) were questioned by the State

witnesses as to their job relatedness and even that

questioning was far less than conclusive. In sum, the

testimony regarding the individual questions were that

of a provisional Sergeant (Suggs) and a Dr. Barrett based

upon his single visit to one correctional facility and

interview with eight Sergeants.

While the interveners-appellants in this brief will

not undertake a complete analysis of the testimony regarding

the examination and are well aware that the burden of

proof is on the State, the relative scarcity of credible

testimony based upon actual experience or factual

knowledge regarding job relatedness emphasizes the prejudicial

-15-

consequences to the interveners-appellants of the failure

to include them in the litigation from the outset.

Many of the individuals in the class which the

interveners-appellants seek to represent were provisional

Sergeants. They are at least as well qualified as the

provisional Sergeant witnesses of the plaintiffs to testify

regarding the job relatedness of various items on the

examination. At the very least, these men represented

by counsel of their choice or class representatives

acting on their behalf should have been afforded a full

and complete opportunity to appear, participate and if

so advised, to testify regarding their background,

experience and opinions as to the job relatedness of the

examination. Obviously, the plaintiffs did not seek to

represent the interest of those men on the eligible

list nor, unfortunately, did the State. While the interests

of the State may be somewhat parallel to those of the

interveners-appellants, the interests are by no means

identical and the State sought to sustain its examination

for its own purpose only and not from the point of view

of the successful candidates. Had the interveners-

appellants been parties to the litigation, as we contend

was required by law, substantial additional testimony in

support of the examination would undoubtedly had been before

-16-

the District Judge and the experts with the result that

the defendants' burden might have been successfully

sustained and a different conclusion might well have

been reached.

POINT I

INTERVENERS-APPELLANTS AND THE CLASS

WHICH THEY SEEK TO REPRESENT ARE

INDISPENSABLE PARTIES AND THE FAILURE

TO JOIN THEM IN THE ACTION BEFORE THE

TRIAL DEPRIVES THEM OF THEIR PROPERTY

RIGHTS WITHOUT DUE PROCESS OF LAW AND

THE COMPLAINT SHOULD BE DISMISSED.

The interveners-appellants and the class which

they seek to represent acquired a vested property right

by reason of their successful competition in the

examination if the examination is valid. We have

already discussed the statutes giving rise to this

property interest and the District Judge (A 153) recognized

that those men who had succeeded in the examination had

a vested interest in securing the promotions which would

normally follow. To proceed with the litigation in the

absence of these citizens was not only violative of the

sections of the Federal Rules heretofore cited but also

totally failed to heed the teachings of recent authorita

tive decisions regarding the rights of public employees

to due process hearings where job rights are involved.

-17-

The overwhelming weight of modern authority in

a wide variety of situations mandates the right to a

meaningful due process type hearing before a citizen is

deprived of either property or liberty. Goldberg v.

Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 , 90 S. Ct. 1011; Fuentes v. Shevin,

407 U.S. 67, 92 S. Ct. 1983; Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535,

91 S. Ct. 1586; Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395

U.S. 337, 89 S. Ct. 1820; Wisconsin v. Constantineau,

400 U.S. 433, 91 S. Ct. 507; Groppi v. Leslie, 404 U.S.

496, 91 S. Ct. 490; Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371,

91 S. Ct. 780; Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564,

92 S. Ct. 2701 and Perry v, Sindermann, 408 U.S. 593,

92 S. Ct. 2694.

While only Roth and Sindermann dealt with public

employees, the teaching of the other cases mentioned was

that any governmental taking of property or liberty

without a prior hearing is constitutionally impermissible

except in cases of an overriding State interest or

extraordinary situations justifying the postponing of

notice and opportunity for a hearing.

The expression of the high court in Boddie v.

Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 at 378, 91 S. Ct. 780 at 786

seems to best sum up the pre-Arnett rule of the Supreme

Court:

-18-

"What the Constitution does require

is 'an opportunity . . . granted at

a meaningful time and in a meaningful

manner', . . . 'for a hearing appropriate

to the nature of the case' . . . . The

formality and procedural requisites

for the hearing can vary, depending upon

the importance of the interests involved

and the nature of the subsequent pro

ceedings. That the hearing required by

due process is subject to waiver, and

is not fixed in form, does not affect

its root requirement that an individual

be given an opportunity for a hearing

before he is deprived of any significant

property interest, except for extra

ordinary situations where some valid

governmental interest is at stake that

justifies postponing the hearing until

after the event. In short, 'within the

limits of practicability; . . . a State

must afford to all individuals a meaning

ful opportunity to be heard if it is to

fulfill the promise of the Due Process

Clause."

Property rights of public employees were specifi

cally considered in Roth and Sindermann and the rule

which can be drawn from these cases is that a public

employee who has a reasonable expectation of continued

employment based upon either express rules, regulations

or statutory provisions or upon past practice is entitled

to a due process hearing before being deprived of those

interests.

In the case at bar, the very existence or

non-existence of a property right in the intervenors-

appellants and their class is a central question to the

-19-

litigation. To proceed with a determination in the

absence of those individuals whose property rights and

liberty rights are involved is the absolute antithesis

of due process. Even if we assume arguendo that a

property right had not become vested in the intevenors-

appellants, the opportunity to pursue one's chosen

vocation, and to seek and attain advancement therein

would appear to be a liberty right which is fully

protected by the guarantees of due process under the

Fifth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

The proposition that the constitutional mandate

of due process is as binding upon the Federal Courts as

other federal agencies does not seem to require citation.

The most recent decision of the Supreme Court of

the United States regarding employees due process rights

is Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 94 Sup. Ct. 1633.

While the multiplicity of opinions in Arnett is confusing,

we have the words of the high court itself for the

meaning of Arnett which it analyzed in Wolff v. McDonnell,

U.S. , 94 Sup. Ct. 2963 at 2975 wherein it cites

Roth and Arnett for the proposition:

"The Court has consistently held

that some kind of hearing is required

at some time before a person is finally

deprived of his property interests . . .

-20-

The requirement of some kind of a hear

ing applies to the taking of private

property . . or to government . created

jobs held absent 'cause' for termination."

The classic definition of parties who should or

must be joined in a suit in equity before a Federal Court

is found in Shields against Barrow, 58 U.S. (17 How.)

130 (1855) at page 139:

"3. Persons who . . have an interest

of such a nature that a final decree

can not be made without either affecting

that interest, or leaving the contro

versy in such a condition that its final

determination may be wholly inconsistent

with equity and good conscience are

indispensable parties."

The distinction at that early date drawn by the

Court between what are now generally thought of as

"conditionally necessary" and "indispensable" parties

has been carried forward into Rules 19 (a) and 19 (b)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Intervenors-

appellants herein are by any standard indispensable.

Although ordinarily an adjudication can not

legally bind an absent party, the determination of the

rights of the parties present in the case at bar will

have a devastating adverse effect upon the absentee's

interests.

-21-

In cases where a similar substantial adverse

effect would be imposed upon a absentee, joinder has been

held to be necessary. Thus all beneficiaries or legatees

of a trust or estate have been held to be indispensable

to an action, when the trustee or executor has an adverse

interest. See eg., Young v. Powell, 179 Fed. 2d 147

(5th Cir.), cert, den'd., 339 U.S. 948 (1950); Baird v.

People's Bank & Trust Co,, 120 Fed. 2d 1001 (3rd Cir.

1941). Where a trustee was sued in connection with the

distribution of a fund in which an absentee claimed a

superior interest, while the litigation would not affect

the absentee's legal claim to the fund, the absentee

would find his claim of little value once the fund was

dispersed. Under the circumstances the absentee was

held to be an indispensable party. Roos v. Texas Co.,

23 Fed. 2d 171 (2nd Cir. 1927), cert, den'd., 2770 U.S.

587 (1928); see also United States v. Bank of New York &

Trust Co., 296 U.S. 463 (1936). In the case at bar the

District Judge in deciding the legal issue between the

parties present before him necessarily weighed the rela

tive rights of the plaintiffs and the absentee applicants

for the position of correction sergeant. The judgment

has a direct factual impact upon the absentees and the

interest of the absentees being present should prevail

-22-

over the plaintiffs' interest in proceeding with the

suit.

In a case somewhat analogous to the instant matter,

the National Railroad Adjustment Board issued con

flicting orders as to which of two unions were entitled

to a particular job. One union sought court enforcement

of its award, the other union, since its members would

have been dispossessed of their rights, had to be joined.

Order of R. R. Telegraphers v. New Orleans, Texas and

Mexican Railway, 229 Fed.2d 559 (8th Cir.), cert, den'd .,

350 U.S. 997 (1956). A similar result has been reached

where the full disposition of the case required consider

ation of the competing claims of two unions, Missouri,

Kansas, Texas Railroad v. Brotherhood of Railway and

Steamship Clerks, 188 Fed.2d 302, 305-306 (7th Cir. 1951)

and where a plaintiff sought to establish the invalidity

of the charter of an absentee corporate defendant,

Northern Ind. Railroad v. Michigan Central Railroad,

56 U.S. (15 How.) 233 (1853).

While it may well be that where the Court is

assured that the absentee had notice of the pending action

it should consider the availability of intervention to

the absentee, these considerations would not appear to

militate against the intervenors-appellants in the case

-23-

at bar. There is no showing in the Record before this

Court that the eight-seven (87) persons from the eligible

list appointed in April 1973 (A-197), the one hundred

eighteen (118) persons presently employed as provisional

correction sergeants, or the five hundred one (501) persons

who successfully passed Examination 34-944 (A-213) received

any notice sufficient to require their early intervention as

a matter of law. The interest in challenging the examination

centered at the correctional facilities at Sing Sing and

Greenhaven but correction sergeants are employed through

out the State and there is no indication whatsoever that

the interested parties at more distant facilities were

aware of the litigation or their right to participate

therein for the protection of their interests. In addition

when the District Judge was confronted with an application

to intervene prior to the time of trial he denied the

application for intervention as previously pointed out.

Yet a further alternative might have been available

to the District Court confronted with absent indispensable

parties since it might have shaped its decree so as to

mitigate the impact on the absentee and avoid a determina

tion of indispensability. This the District Court declined

to do in its final decree (A-241-A-245) since it enjoined

the present defendants from making permanent any provi-

24-

sional appointments based upon Examination 34-944 and

directed that all interim appointments be made on the

basis of a racial quota which obviously will adversely

effect the standing of at least some of the class which

the intervenors seek to represent.

Supplementing its original decree, the Court, with

out notice to the intervenors, issued a supplemental decree

on September 18, 1974, a copy is annexed hereto as Exhibit

3. Neither in the original decree nor in the supplemental

decree does the District Court provide for participation

of the intervenors-appellants in the interim selection

procedure or the final selection procedure. In short the

District Court proceeded in total disregard of the rights

of the intervenors-appellants and their class throughout

this proceeding, even down to the supplemental decree.

Under Rule 12(h) of the Federal Rules this Court

has the discretion to consider indispensability on its

own motion and should do so in this case where it is

called upon to protect the legitimate interests of absen

tees from the trial.

Under Rules 19 and 21 of the Federal Rules, the

District Court had discretion in adding indispensable

parties. The intervenors-appellants were amenable to

the process of the Court and would not have destroyed

-25-

proper venue. The Court below could have allowed plain

tiffs to amend their complaint to add the indispensable

parties or summon them on its own motion. The Court

below made no attempt to do any of these things. Further

more, the trial court had the power to dismiss the complaint

in the absence of the indispensable parties amenable to the

process of the Court where the plaintiff made no attempt

to join the absentees. See eg., United States v. Elfer,

246 Fed.2d 941 (9th Cir. 1957). Under all of the circum

stances in the case at bar, the plaintiffs, the defendants

and the District Court having totally failed to bring the

interested absentees before the Court in a timely

fashion to afford them an opportunity to protect their

property interests, the complaint should be dismissed.

-26-

RRR/gc

POINT II

THE DISTRICT COURT SHOULD HAVE

ALLOWED APPOINTMENTS FROM THE

ELIGIBLE LIST CREATED BY EXAMINA

TION 34-944 TO BECOME PERMANENT

AND SHOULD NOT HAVE DIRECTED THE

USE OF A ONE TO THREE PREFEREN

TIAL APPOINTMENT RATIO IN EITHER

INTERIM OR FINAL APPOINTMENT

PROCEDURES.

In the case at bar as in Griggs v. Duke Power

Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) and Chance v. Board of

Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (1972) , there is no proof of

any intentional discrimination but proof that the

examination had a disparate pass-fail ratio for blacks

and Hispanics as against whites, and was not proved to

be job related. There is no proof in the case at bar

of any past discrimination and the District Court made

no such finding.

This Court has sustained hiring quotas in U.S. v.

Wood, Wire, and Metal Lathers International Union, Local

46, 471 F.2d 408, Cert. Den. 412 U.S. 939, (1973);

Vulcan Society of New York City Fire Department, Inc, v.

The Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d 387, (1973);

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Members of Bridgeport Civil

Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333, (1973); Rios v.

Steamfitters Local 638, F.2d , 8 FEP Cases 293

-27-

(June 1974). All are distinguishable.

Lathers involved intentional discrimination and

a quota to correct past discriminatory practices which

continued even after the action was started, the Lathers

court recognized that "quotas merely to attain racial

balance are forbidden".

By contrast with Lathers, under the District

Court order in the case at bar, lower qualified minority

members will be preferred over better qualified whites.

Rios involved continuing intentional discrimination.

Although preferential hiring quotas were upheld, this Court

pointed out that when a racial imbalance is unrelated to

past discrimination no justification exists for ordering

that preference be given to anyone on account of his race or

for altering an existing hiring system or practice.

Bridgeport Guardians and Vulcan Society involved

Civil Service examinations in which interim quotas were

gingerly sustained pending the preparation of a validated

non-discriminatory selection procedure. In both cases

quotas were approved to correct the effects of past discrimina

tion. In the case at bar only one examination is involved,

no past discrimination has been shown and in fact extensive

efforts have been demonstrated to achieve racial balance.

-28-

There have been positive steps to recruit minority

personnel, particularly in the entry position and thus

the pool of eligibles for examination and promotion has

been enlarged.

State discrimination on grounds of race is pro

hibited by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. See eg. McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184

(1964) .

A quota in favor of non-whites is a classification

on the basis of race.

The District Court erroneously failed to even

restrict the preference to members of the aggrieved class.

See eg. Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1971), which

upheld an interim hiring method granting preference to

minority group members who had actually taken and failed a

discriminatory test but later passed the new validated

test. Consequently, those individuals who had been dis

criminated against were eligible for a preference but the

trial court here has accorded a preference to any black or

Hispanic, a preference which is without rational basis

or legal support.

As was said by the United States Supreme Court in

Milliken v. Bradley, 42 U.S. Law Week 5249, July 25, 1974,

"The task is to correct by a balancing of the individual

29-

and collective interests the condition that offends the

Constitution" but the power should be used "only on the

basis of a constitutional violation".

Chief Justice Burger, stated:

"The controlling principle, consis

tently expounded in our holdings, is

that the scope of the remedy is deter

mined by the nature and extent of the

constitutional violation . . . an

inter-district remedy might be in

order where the racially discriminatory

acts of one or more school districts

cause racial segregation in an adjacent

district or where district lines had

been deliberately drawn on the basis of

race . . . Conversely, without inter

district effect, there is no constitu

tional wrong calling for any inter

district remedy".

Intervenors-appellants agree that a new validated

non-discriminatory test be prepared forthwith but we

earnestly oppose as unjustified the remedy of hiring

quotas either before or after the new selection procedure.

A single test adopted in good faith but declared after

trial not to be job related does not justify such drastic

dismantling of the Civil Service system.

The cornerstone of a professional civil service

is the concept of appointment and proportion based upon

merit, fitness and ability. In New York State the

guarantee concerning merit is contained in the New York

State Constitution, Section 6, Article 5:

-30-

"Appointments and promotions in the

civil service of the state and all of

the civil divisions thereof, including

cities and villages shall be made

according to merit and fitness to be

ascertained, as far as practicable, by

examination which as far as practicable,

shall be competitive; . . . "

The New York State Civil Service Law provides a statutory

implementation of this constitutional mandate which has

a long and honorable history of successful administration.

Neither plaintiffs nor the State purport to urge

any merit basis for promotion to sergeant. The introduction

of nonmerit procedures and standards would contravene not

only the State Constitution and Civil Service Law but would

also violate the EEOC Guidelines since merit is closely

associated with job success and criteria. Furthermore,

such a procedure would deny equal protection of the law

to the intervenors and their class.

The District Court has ordered a quota without

mandating any objective showing of relative qualifications.

This action is grossly racially discriminatory since many

white provisional correction sergeants were not retained

because they too failed the examination and men, both

black (Ribeiro) and white have passed the test and success

fully worked as provisional sergeants. The only qualifica

tion that plaintiffs apparently claim is satisfactory is on

the job performance, yet both the white disqualified provi

-31-

sional and all sergeants appointed from the eligible list

have likewise satisfactorily performed. The plaintiffs do

not even seek the appointment of the most highly qualified

minority correction officers since a number of minority

candidates scored higher on the test than the named plain

tiffs and some of them are in the class of intervenors.

This is offensive to the concept of merit, denies equal

protection of the law and should not be countenanced by this

Court.

The District Court has in practical effort ordered

a criterion validated examination. It ignored the consequen

ces to all correction officers and provisional correction

sergeants that flow from this demand. All agree that the

construction of valid criteria for any position is a time

consuming task and the possibility exists that even after

a large investment of time, valid criteria may not be

established.

This seemingly joint disregard for prompt action

in this highly crucial matter is offensive to the system

long and successfully operated under the New York Constitu

tion and the New York State Civil Service Law. This Court

should endeavor to fashion a remedy consistent with those

articles, not destructive of them.

If the merit system is to function it is necessary

-32-

that there be a minimum of delay in the creation and

administration of a valid test and thereafter a minimum

of delay in establishing a promotional list. The

State of New York has the facilities to proceed with

all due dispatch in the creation of a valid examination

for the position of correction sergeant.

The Court should, as an interim measure, require

the prompt creation of an examination validated by any

acceptable method considering the following points:

1. The creation of any validated examination

will be a time consuming process.

2. The effect of the decision in this case

invalidating examination 34-944 is to leave all current

correction officers, white, black and hispanic, without

any method of advancing in their choosen profession.

3. The experts agree that the development of a

criterion validated test must be conditioned upon the

development of valid criteria, a process that is by no

means certain.

4. The development of alternate methods of

testing will require a long period of time even if

feasible under EEOC Guidelines.

5. The pool of permanent sergeants is continually

being depleated due to advancement, retirement, death

-33-

and resignation.

6. Any attempt to maintain the sergeant pool by

provisional appointments suffers the very infirmity

complained of by plaintiffs in paragraph 18 of their

complaint, that is lack of interinstitutional mobility

since very few persons, if any, will accept the hardships of

relocation for a provisional appointment.

7. The continuation of the uncertainty of appoint

ments will adversely effect the public interest, the private

interest of all correction officers and of all members of

the classes represented by the named intervenors, the

named plaintiffs, and the State.

The District Court held that the State did not

meet its burden of demonstrating strong probabilities that

the test 34-944 was job related. The only proven vice

of the examination was a statistical discrimination

against the racial and cultural group represented by plain

tiffs. In holding that the test was not fair within the

mentioned limits there was no holding that the examina

tion was not valid within the various social and ethnic

groups.

Despite the experts opinions, examination 34-944

has shown predictive validity at least as to those officers

who received appointments from the promotion list and who

- 34-

have successfully filled the job for over a year. No party

to this action has contended that the correction officer who

passes examination 34-944 with high marks is for that

reason unqualified for the position of correction sergeant.

There has been no showing that there exists a negative corre

lation between the examination mark and the ability to pro

perly function as a correction sergeant. In fact, the

named intervenors and those of their class who have been

appointed to the position of correction sergeant have per

formed the tasks required in a satisfactory and acceptable

manner and make up a significant segment of the correction

sergeants in the New York State Correctional System.

All the officers promoted from the promotion

list generated by examination 34-944 were promoted to

permanent positions but for this action. The State

presumably followed its own rules and regulations for

evaluating those officers as correction sergeants during

service in the position. The New York State Civil Service

Department Rules and Regulations provide for an 8 to 26

week probationary term for all promotions with reversion

to the previous lower rank if the appointee is found to

be lacking in capacity, conduct or performance. Presum

ably the sergeants promoted from the 34-944 list were so

evaluated and found satisfactory since none were demoted back

-35-

to correction officers and the State in this action has

asserted that all sergeants promoted from the list are

satisfactory.

The rules and regulations except temporary and

provisional appointments so that the named plaintiff

and the five other officers similarly situated were

presumably not so evaluated during their provisional

service and can not claim that they passed any

probationary period or on the job evaluations

successfully.

It is the intervenors -appellants contention that

examination 34-944 is a more accurate predictor of ability

to properly perform the duties of correction sergeant than

a recommendation of one or two supervisors. The named

plaintiffs and the five other officers so situated

received their provisional appointments on recommendation

from their supervisors based on no proven valid criteria.

The named intervenors and those of their class who have

been appointed correction sergeants are more qualified than

the named plaintiffs to hold their positions. The satis

factory performance of the class members as correction

sergeant in fact provides a post-validation of

examination 34-944 as to those officers who received

appointments as a result of the examination.

The intervenors suggest that an order be entered

providing for the permanent appointment to the position

of correction sergeant of all of the correction sergeants

appointed from the 34-944 eligible list who now have

satisfactorily completed and who hereafter satisfactorily

complete the twelve week provisional period.

This interim relief would have the following

effects:

1. Prevent an unjust and inequitable penalization

of the employees who participated and succeeded in the

selection procedure in good faith and without fault.

2. Prevent a chaotic situation from developing

in the correctional system.

3. Provide for the manning of the vital position

of correction sergeant by persons demonstratably suited

for the positions.

4. Provide a rational basis for the selection

of permanent correction sergeants until the required

examination can be prepared.

In Chance v. Board of Examiner, 458 F.2d 1167,

(Second Circuit, 1972) the court accepted the appointment

of "acting" supervisors. Such a procedure here would be

totally unworkable and unjust. The fact situation in

this case is very different from the fact situation in

-37-

Chance. In Chance all of the positions were located in

the City of New York, in this case the positions are located

throughout the New York State. In Chance it was not

necessary for an "acting" superviser to move his residence

and foresake his community in order to accept an "acting"

supervision position. In this case many persons have been

forced to move their residence or to establish a second

residence for the purpose of taking a Sergeant's

appointment. In Chance, id 1178, there was a finding

that the injunctions would cause no "great harm" to the

public or to school children in view of the availability

of acting appointments in New York City. In the case at

bar there will be harm to the public because the availability

of provisional Sergeants will be low because of the actual

hardships encountered.

Taking into account all of the facets of this case,

the balance of hardships does not favor the plaintiffs

compared to the intervenors.

The true victims of this action are the intervenors

and the class which they represent. These men fulfilled all

of the requirements of a promotion set by the State, many

of them have been forced to change their residences or

maintain separate abodes apart from their families. All

of them have surrendered their position as Correction

-38-

Officers and if their appointments are not confirmed each

will revert by operation of the New York State Civil Service

Law to the position of Correction Officer. Moreover they

will not return to the positions which they held prior

to their appointments to Correctional Sergeant but will

be forced to take positions now open and of the least

desirable nature since under the contract between the

State of New York and Security Unit Employees, Council 82,

AFSCME, AFL-CIO, now in effect the persons now acting

as provisional Correction Sergeants cannot bump the officers

who have taken their old positions and who now hold

permanent appointments.

When objectively considered, a highly inequitable

and discriminatory result is obvious. The permanent

appointment of the named plaintiffs and the five other

officers holding provisional appointments to the position

of Correction Sergeant and other quota beneficiaries to

the exclusion of all the officers holding provisional

appointments as Correction Sergeant as the results of

passing examination 34-944, would result in a highly

artifical class eligible for the next examination for

the position of Lieutenant. In fact the requested

remedy will allow the named plaintiffs and five other

-39-

officers so situated several attempts at the position

of Lieutenant while all of the other Correction Officers

and provisional Correction Sergeants are barred from

advancing even to the permanent position of sergeant

and this bar would act against all white, black and

hispanic officers. In other words success will be

penalized. After all, what is more unjust than depriving

intervener-appellant Ribeiro of his hard won promotion.

Does his success make him less worthy.

The racial composition of the Department of

Correctional Services staff taken from the State trial

memoranda in this case is summarized below:

1/1/73 5/1/73 2/20/74

White 89.7% 88.8% 86.0%Black 8.6% 8.5% 10.9%

Hispanic 1. 7% 2.7% 3.1%

Total Minority 10.3% 11.2% 14.0%

The trend is clear from these statistics that the

representation of blacks is increasing in the entry level

pool. From these statistics and from the testimony at

trial it appears that the number of minority Correction

Officers has greatly increased in the last few years

although until the last examination only a few minority

officers were sufficiently experienced to qualify for the

Correction Sergeant examination.

-40-

The imposition of quotas for promotion would

result in the high probability that less qualified

minority Correction Officers would receive appointments

to the permanent position of Correction Sergeant to the

detriment of better qualified white and minority correction

°fficers. After the disaster at the Attica correctional

facility it is necessary to assure that the best possible

officers man each position in the correctional facilities.

The basis of the relief sought by plaintiffs is

that minority groups should be fairly represented at

the level of Correction Sergeant. The intervenors-

appellants agree that minority groups should be fairly

represented but we do not agree that fair representation

requires absolute numerical representation.

We respectfully submit that the seniority require

ments imposed by the State for promotion to sergeant

(two years employment as Correction Officer before taking

the promotional examination and three years employment as

Correction Officer before promotion to Correction Sergeant)

are in furtherance of a valid state interest and do not

impose unnecessary restrictions upon minority advancement

in the Correction Officer series. The intervenors-

appellants submit that absolute numerical representation

would be unfair to Correction Officers in general, since

41-

the percentage of minority group members has expanded

drastically in the last three years, and since minority

groups are over represented in the low seniority position

due to this rapid increase in employment. Thus, minority

representation should not be based upon the number of

minority members, but upon the number of minority members

eligible for promotion through the acquisition of

experience on the job.

This Court should also consider that the recent

transfer of the Bayview and Edgecomb facilities from the

Narcotics Addiction Control Commission to the Department

entailed the transfer of the staff of these facilities

from the Narcotics Addiction Control Commission to the

Department. These facilities are staffed by officers who

are almost exclusively members of the minority groups

at all levels, including Correction Sergeant (formerly

charge officer). The addition of minority group Sergeants

from Bayview and Edgecomb should thus be considered in

determining the necessity of making remedial appointments

of minority group members to the position of Correction

Sergeant.

The intervenors-appellants seek a middle ground

between the polar views of the District Court and the

plaintiffs on one hand and defendants on the other. We

seek the prompt construction of an examination validated

-4 2-

by any recognized method, based upon the past experience

of the State in promotional testing and the requirement

that the examination be constructed free from constitu

tional taint.

The New York State Civil Service Commission and the

New York State Department of Correctional Services are

both large organizations with impressive resources.

Moreover, both have access to the larger and even more

impressive resources of the State of New York. Any

claim that the prompt creation of a validated examination

for the position of Correction Sergeant would place a

strain upon these resources appears to be highly artificial.

This action has forced the State into an indepth

examination of the position of Correction Sergeant and

should by this time have produced a detailed job analysis

sufficient to support the development of a valid, job

related examination. Also the methods project already

undertaken by the State covering the position of Correction

Sergeant should reduce any burden in creating a new

examination.

The intervenors-appellants do not dispute the

possible necessity of creating new forms of testing or

the possible necessity of a criterion validation for

future examinations. However, even with the vast

resources available to the State, the intervenors-

-43-

appellants question the possibility of creating such

an examination within a reasonable period of time, and

question the necessity of such a remedy at this time.

The Court should consider the fact that over 4,000

Correction Officers have been prevented from normal

promotion opportunity since August 1972 and any un

necessary delay in the creation of a new examination

would unduly prejudice all Correction Officers including

those represented by the plaintiffs.

Intervenors-appellants agree with the need for

continuing supervision of this Court over the construction

of a new, validated, job related examination involving

all parties to this appeal. In order that such super

vision be of any practical value it is necessary that a

fully adversary hearing be held to inquire into the

validity and validation of the new examination. Full

supporting data should be required to be delivered to

the attorneys for the plaintiffs and to the attorneys

for the intervenors-appellants to enable the Court to

have the widest possible variety of objections and

comments concerning the proposed new examination. The

plaintiffs' attorneys would insure against the inclusion

of any material that is prejudicial to the rights of

minority members. The attorneys for the intervenors-

-44-

appellants would provide protection against materials

that were prejudicial against all other Correction

Officers.

Any proposal by the State calling for its

development of a new examination lacking scrutiny by the

parties to this action and by the Court simply asks for

a repetition of this lawsuit. For the good of all persons

involved whether parties or nonparties it is necessary

that there be a final conclusion to the problem presented

in this action.

In an earlier memoranda, the plaintiffs conceded

that but for the temporary restraining order the eighty-

seven Correction Officers who received provisional

promotion to the position of Correction Sergeant on or

before April 12th, 1973 would have received permanent

appointments to that position effective as of April 12th,

1973. In light of the States continuing needs, it is not

necessary to bar these Correction Officers from the position

of Correction Sergeant in order to obtain full and adequate

relief in this action.

Based on the principle that equity will do no

unnecessary harm, this Court should refraim from taking

any action which would deprive these officers of the

position of Correction Sergeant.

-45-

The intervenors seek permanent appointments as

Correction Sergeant for all other Correction Officers

who received appointments as Correction Sergeants based

upon their performance on examination 34-944.

The State of New York has already taken action

which would obviate any need to remove these men from

the position of Correction Sergeant in order to grant

equitable relief. The State of New York has recently

commenced a plan to transfer the Bayview and Edgecomb

facilities from the Narcotic Addiction Control Commission

to the Department of Correctional Services. Upon

information and belief this transfer entails among other

consequences, the transfer of 12 or 13 minority charge

officers to the position of Correction Sergeant. Upon

information and belief, these Sergeants would constitute

approximately six percent of the total Correction Sergeants

in the Department of Correctional Services. The intervenors-

appellants are not implying that this transfer to the

Department of Correctional Services of the Bayview and

Edgecomb facilities is in any way an attempt to correct

racial imbalances caused by past examinations but rather

that this is a consequence of a valid State purpose in

increasing the number of correctional facilities.

Intervenors also point out that the State of New York

-46-

has not been uniformly successful in obtaining minority

supervisory officers in the various series of

institutional examinations and has not shown intentional

prejudice against minority advancement.

These new minority Correction Sergeants, when

coupled with the positions that have been unfilled since

the date of decision in this action, and the new Correction

Sergeants positions which have been authorized for the

Department of Correctional Services, allow this Court

sufficient latitude to achieve the results desired by

the plaintiffs without harming any of the officers who

were appointed Correction Sergeant as the result of

examination 34-944.

The date of appointment as provisional Correction

Sergeant should govern the date of permanent appointment

and no harm is done to any party by such an order. To

set any later date for the permanent appointment would

cause damage to the officers by placing them lower on

the seniority scale than their service in rank calls

for and by possibly placing them lower on the pay scale

than their length of service in rank requires.

The impact of the decision of the District Court

falls not upon the State but rather the Correction

Officers who in good faith took and passed examination

34-944.

-47-

There was no showing of a negative correlation

between test results and ability or job preparedness.

There was no showing that the examination did not fully

and fairly distinguish ability and job preparedness

within the various ethnic groups.

The intervenors urge this Court not to disregard

the expectations and equities of those Correction Officers

who successfully participated in examination 34-944,

an examination which they did not know and could not know

was constitutionally tainted.

A possible additional requirement could be added

requiring all Correction Sergeants who were appointed

since the trial to pass the new, validated examination

in order to retain their permanent positions as Correction

Sergeant.

No solution to this problem is going to please

everyone but this Court should attempt to fashion a remedy

which will assure constitutional fairness and do the

least possible harm to all persons, whether parties or

non-parties.

-48-

CONCLUSION

THE DETERMINATION OF THE DISTRICT

COURT SHOULD BE REVERSED, THE

COMPLAINT SHOULD BE DISMISSED AND

ALL APPOINTMENTS MADE TO THE POSI

TION OF CORRECTION SERGEANT AS THE

RESULT OF EXAMINATION 34-944 SHOULD

BE MADE PERMANENT. IN THE ALTERNA

TIVE THE DETERMINATION OF THE DIS

TRICT COURT SHOULD BE MODIFIED, ALL

APPOINTMENTS MADE FROM THE ELIGIBLE

LIST GENERATED BY EXAMINATION 34-944

SHOULD BE MADE PERMANENT, IN THE

INTERIM THE COURT SHOULD ORDER

SELECTION PROCEDURES DEVISED BASED ON

MERIT WITHOUT THE IMPOSITION OF RATIO

QUOTAS AND THE STATE SHOULD BE ORDERED

TO DEVELOP A NEW CONSTITUTIONAL

EXAMINATION UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF

THE COURT WITH PARTICIPATION BY

PLAINTIFFS AND INTERVENORS.

Dated: October 23, 1974

Albany, New York

Respectfully submitted,

SNEERINGER & ROWLEY P.C.

Attorneys for Intervenors-

Appellants

Office & P. 0. Address

90 State Street

Albany, New York 12207

Tel. No. (518) 434-6188

RICHARD R. ROWLEY,

JEFFREY G. PLANT,

Of Counsel.

IN TI1E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EDWARD L. KIRKLAND, et a.L,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

THE NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF

CORRECTIONAL SERVICES, ct al„,

Defendants.

YORK

(# O'

■A

! A D ~ :;v .

f f

ir.i;j *5 VJ; 3 1

i K r / . - I - . /S ' v mr \ i

/

M. E . L . frr*

73 Civ. 1543

x

ORDER

Upon all of the papers heretofore filed and the Court's

having heard argument of counsel, it is hereby

ORDERED, that defendant deliver to plaintiffs’ counsel

on or before June 18, 1973, for each individual in each of the

categories hereinafter set forth, the following information con

tained in such individual’s personal history folder or-other

personnel record:

1) all educational entries;

2) all work experience;

3) all memoranda or documents relating to such

employee which contain criticism, commendation,

appraisal or rating of such individual's per

formance on his job;

The categories of persons about whom such information

is to bo provided are as follows:

1) all white employees of the Department of

Correctional Services who held provisional

appointments to the position of Correction

Sergeant (Male) as of April 10, 1973, took

examination Number 33944 and

a) passed the oxanrii ticn and ranked in

the f i r<: t 100 of l I'l or. o on the iresu 11

r j .*/ n v ■- '“r*. p tr=?

K \y t i n grp < L ~ ~

eligible list;

b) passed the examination and ranked

below the first 100 on the resulting

e 1 .i g ib 1 e list*

c) failed the examination;

2) all black employees of the Department

who held provisional appointments to the

position of Correction Sergeant (Male)

as of April 10, 1973, took examination

number 34944, and

a) passed the examination and ranked

in the first 100 of those on the

resulting eligible list;

b) passed the examination and ranked

below the first 100 on the resulting

eligible list;

c) failed the examination;

3) all white employees of the Department of

Correctional Services who took examination

number 34944 and

a) passed the examination and ranked

from 1 to 20 on the resulting

eligible list;

b) passed the examination and ranked from

201 to 220 on the resulting eligible

list;

c) passed the examination and ranked

from 387 to 406 on the resulting

eligible list;

d) failed the examination, achieving

scores from 65 through 65.9;

4) all black and Hispanic employees of the

Department v.’ho took examination number

34944 and

‘a) passed the examination and ranked

-2-

from 1 to 20 on the resulting

eligible list;

b) passed the examination and ranked

from 201 to 220 on the resulting

eligible list;

c) passed the examination and ranked

from 387 to 406 on the resulting

eligible list;

d) failed the examination, achieving

scores from 65 through 65.9,

There shall be designated on each individual's record

the category and sub-category or categories and sub-categories

i

United States District Judge

ENDORSEMENT

v. THE NEW YORK

iVICES, et alo ,

WwVfl

ROBERT JACKSON, et al., Plaintiffs,

STATE "DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SI

-Defendants. 73 Civ. 1548

Ck, A v, ~ ‘

LASKER, D.J.

£ The motion is denied. Although we do not agree

withe'piaintiffs and defendants that the mere fact that

v£he proposed interveners may not have property rights

in the position of correction sergeants in conclusive

against'their having a right to intervene, we never

theless believe the motion should be denied for the

following reasons:

{ -

ir

r;

^ ••

Ql

c

i. i i. • » •, ii

(A) Untimeliness. This suit was commenced on

April 10th, by the filing of a complaint and a motion

for temporary relief. Counsel for the proposed inter

veners acknowledges that the existence of the action

and the ore

short time

nature of i

ler issued was known to the movants within a

after the suit was brought, and, in the

:he case, we believe it reasonable to infer

that all persons interested in becoming correction

sergeants learned of the suit at an early date, even-

if not formally notified. This application for inter

vention was not made until July 11th, only ten business

days prior to the commencement of trial. To permit

intervention so late in the game would result in the

necessity of reopening discovery, which would be

completely unacceptable, unless -- and this is the

position which the interveners have acknowledged in

their papers -- the movants do not participate in the

trial or proceedings.relating to the merits of the

case. True intervention would inevitably require a

delay in the trial now set to commence July 23rd. In

a matter affecting the assignment of correction

sergeants in State institutions such a delay would

clear]y be prejudicial to all concerned, the plaintiffs,

defendants and. rhe public.

(B) Questionability of Right to Intervene.

Furthermore, while we have indicated some doubt that

the lac): of a property right by the proposed inter

veners in the correction sergeant job establishes

conclusively that they have no right to intervene,

nevertheless whether they do have a right to intervene

I! , pr-:-rj

> ;r-JtfiA IvJ Ldi i . i u i

is far from clear. There .is a serious question whether

the interests they assert and see): to protect will be

affected by the outcome of this lawsuit.

There are further complications: Among the

groupcf proposed intervenors, interests conflict:

some of them have passed the examination under attack

and some have failed it. There is no indication

vrtiether movants wish to be aligned as plaintiffs or

defendants or how they should be aligned.

(C) Modification of Existing Order. The true

objectives of the proposed intervenors, as they acknow

ledge, is solely to secure a modification of the

extended temporary restraining order presently in