Arizona Governing Committee v. Norris Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 7, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Arizona Governing Committee v. Norris Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1983. d0eba463-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/27d0712a-913a-4e13-96b7-004e146bb285/arizona-governing-committee-v-norris-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

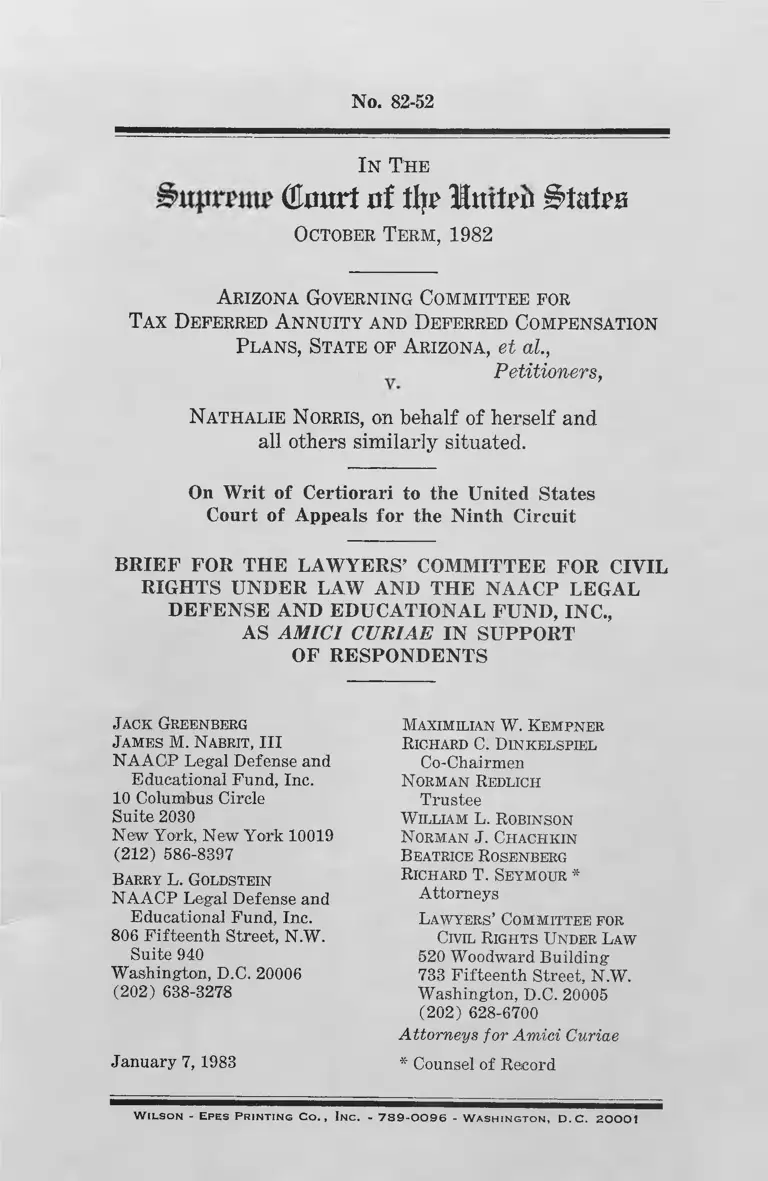

No. 82-52

In T he

dmtrt at % Imtpii States

October Term, 1982

Arizona Governing Committee for

Tax Deferred Annuity and Deferred Compensation

Plans, State of Arizona, et a l ,

Petitioners,

Nathalie Norris, on behalf of herself and

all others similarly situated.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW AND THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF RESPONDENTS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, H I

NAAGP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Barry L. Goldstein

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

806 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 638-3278

January 7,1983

Maximilian W. Kempner

Richard C. Dinkelspiel

Co-Chairmen

N orman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

N orman J. Chachkin

Beatrice Rosenberg

Richard T. Seymour *

Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

520 Woodward Building

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

W i l s o n - Ep e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 789-0096 - W a s h i n g t o n , D.C. 2000)

INDEX

Page

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .................................. 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................... ................... 2

ARGUMENT ......................................... 1......................... 4

I. THE PRESENT CASE IS CONTROLLED BY

THIS COURT’S DECISION IN LOS ANGELES

DEPARTMENT OF WATER <& POWER v.

MANHART, FROM WHICH IT IS NEITHER

FACTUALLY NOR LEGALLY DISTIN

GUISHABLE .... .......... ........... ..... ........... ........... 4

A. Most of the arguments made by petitioners

and their amici were considered and rejected

in Manhart, and no persuasive justification

for abandoning that ruling is advanced in

this case _______________ __ ___ __ __ 4

1. “Equal Actuarial Value” ____ ________ 5

2. Adverse Selection ........... ......... ................. 7

3. The Accuracy of the Sexually Disparate

Tables in Measuring Longevity ______ 11

B. Arizona’s pension plan cannot be sustained

as being within the “open market” exception

of Manhart _______________________ ___ _ 15

1. Arizona’s Plan Does Not F it Within the

“Open Market” Exception of Manhart

Because the State Did Far More Than

Allow Employees to Purchase Whatever

Life Annuity Policies Were Available on

the “Open Market” ______ __ ____ __ 15

2. A rizona’s Plan Does not Reflect the “Open

Market,” Because the State Could Have

Contracted for Unisex Table Life An

nuities .............. ..... .......... .................. ...... 18

11

INDEX—Continued

Page

II. BECAUSE MANHART GAVE EMPLOYERS

ADEQUATE WARNING OF THE TITLE VII

REQUIREMENTS FOR PENSION PLANS,

THE AWARD OF MONETARY RELIEF BE

LOW WAS JUST AND PROPER ..... ............... 25

CONCLUSION ................. ..... ........... ................. ............ . 27

Ill

Cases

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ......... .......................................................... 19

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840’ (1976) ....... 21

Connecticut v. Teal, ----- U.S. ——, 73 L.Ed.2d

130 (1982) ........... ........... ........... ............ ............ 6,7,19

Farmer v. ARA Services, 660 F.2d 1096, 1104 (6th

Cir. 1981) ................ ...... ........................ ............ . 17

Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 635 F.2d 1007

(2nd Cir. 1980), cert, den., 452 U.S. 940 (1981).. 17

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).... 19

Guzman v. Pichirilo, 369 U.S. 698 (1962) ........ .... 19

Hardin v. Stynchcomb, 691 F.2d 1364 (11th Cir.,

1982) _____ ____ _______ _____ ___ _____ ___ _ 19

Jenkins v. United Gas Corporation, 400 F.2d 28

(5th Cir. 1968) ...... ................ ............. ....... ....... 8

Los Angeles Department of Water & Power v.

Manhart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978) _____ __ ____ 'passim

Lynch v. Alworth-Stephens Co., 267 U.S. 364

(1925) .................... ........... ............. ................. . 21

Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, ——

U.S.------, 73 L.Ed.2d 1090 (1982) ________ 18, 24, 25

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 (1979) _____ __ ____ ___ 17

Rosen v. Public Service Electric and Gas Co., 477

F.2d 90 (3rd Cir. 1973) ........... ....... ....... ..... . 17

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th

Cir.), cert, dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971)..... 17

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248 (1981) _______________________ __ 19

United States v. N.L. Industries, 479' F.2d 354 (8th

Cir. 1973) ............... ............ .................. ........ . 17

United States v. Phosphate Export Ass’n, 393 U.S.

199 (1968) ............ .......... .......... .................. ....... 19

United States v. Poland, 251 U.S. 221 (1920) ___ 19

Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252 (1980) ................. 19

Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975).— 18

Williams v. New Orleans Steamship Ass’n, 673

F.2d 742 (5th Cir. 1982) ____ ____________ _ 17

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Women in City Government United v. City of

New York, 515 F,Supp. 295 (S.D.N.Y. 1981).... 26

Statutes

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000© et seq. .__ ________ _____ 5,16,18,19, 25, 26

26 U.S.C.A. § 1(c) (1) (Supp. 1982) ......... ........... 9

Other Authorities

The Chronicle of Higher Education, Vol. 25, No. 7

(October 13, 1982) ........ ........ ............... ....... ..... 22

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Vital Statistics of the

United States, 1973: Volume II—Section 5: Life

Tables (1975) ______ _____ ____ ____ ___ ___ _ 14

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Vital Statistics of the

United States, 1978: Volume II—Section 5: Life

Tables (1980) ............ ......... ..... ..... ...... ............... 14

In The

^uprattp (Emtrt uf tl|i> Ti&mtvb States

October Term, 1982

No. 82-52

Arizona Governing Committee for

Tax Deferred Annuity and Deferred Compensation

Plans, State of Arizona, et al,

v Petitioners,

Nathalie Norris, on behalf of herself and

all others similarly situated.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW AND THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF RESPONDENTS

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

and the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., respectfully submit this amici brief in support of

the respondents, with the written consent of all parties.

The parties’ consents have been filed with the Clerk of the

Court.

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was founded in 1963, at the request of the President of

the United States, to help secure the civil rights of all

2

Americans through the prosecution of civil rights cases

and by other means. Over the past 19 years, the Commit

tee has enlisted the services of thousands of members of

the private bar across the country in addressing the legal

problems caused by discrimination and by poverty.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a nonprofit corporation whose principal purpose

is to secure the civil and constitutional rights of minori

ties through litigation and education. For more than

forty years, its attorneys have represented parties in

thousands of civil rights cases, including many significant

cases before this Court and the lower courts.

The Committee and the Fund have participated, either

as counsel for a civil rights plaintiff or as amicus, in a

number of decisions of this Court construing Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.

These include Connecticut v. Teal, ----- U.S. ------, 73

L.Ed.2d 130 (1982) ; General Telephone Co. of the South

west v. Falcon, ----- U.S. -------, 72 L.Ed.2d 740 (1982);

County of Washington v. Gunther, 452 U.S. 161 (1981);

California Brewers Ass’n v. Bryant, 444 U.S. 598 (1980);

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193

(1979); Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S.

412 (1978); Hazelwood School Dist. v. United States, 433

U.S. 299 (1977); Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840

(1976) ; Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976) ; Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975); Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ;

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971),

and other cases.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

A. This case is squarely controlled by the decision in

Los Angeles Department of Water & Power v. Manhart,

which considered and rejected many of the arguments

advanced by the petitioners and their amici. In Manhart,

3

the employer sought to justify a pension plan requiring

higher contributions from women than from men for

monthly benefits equal to those of male employees retiring

at the same age; this Court rejected the contention that

the plan did not violate Title VII of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act because the value of the pensions and con

tributions were “actuarially equal.” So, in this case,

Title VII proscribes use of a plan based on equal contri

butions by men and women but affording smaller monthly

benefits upon retirement to women.

Manhart also involved the employer’s claim that unisex

contributions and benefits would lead to adverse selection

out of the pension scheme by males and the ultimate de

struction of the plan. It is as clear in this case as it was in

Manhart that there is no record evidence supporting this

contention, and that adverse selection on the scale pre

dicted by petitioners’ amici is highly unlikely. Moreover,

materials in this record and facts judicially noticeable

demonstrate the extent to which the life annuity plans at

issue were based upon the sex of employees, rather than

upon an accurate measure of expected longevity.

Indeed, the sex-based tables at issue here do not even

deal fairly with women as a class, compared with men

as a class. By substantially overstating the average sex

ual differences in life expectancy at the relevant ages,

they require women as a class to subsidize the benefits of

men as a class.

B. The Arizona plan cannot be saved from condemna

tion under Title VII by the “open market” exception of

Manhart. Arizona did far more than passively make

available accumulated contributions to retiring employees

who purchased their own life annuities on the open mar

ket; it affirmatively limited the choices available to its

employees to include only life annuities based on discrim

inatory, sex-based mortality tables. Nor can it be said

that Arizona gave its employees a selection of payout op-

4

tions, including life annuity plans, which fairly reflected

the “open market.” The State simply failed to establish

on this record that it was unable to contract for unisex

annuities, and amici’s own research indicates that such

plans are available and in use today. Moreover, the Lin

coln National Life Insurance Company—one of the com

panies used in Arizona’s plan—has informed amici that

it is willing to provide group life annuities on a unisex

basis to employers offering it a substantial amount of

business.

II.

Because Manhart explicitly put employers on notice

that sex-based pension plans violated Title VII, the con

siderations which led this Court to withhold retroactive

monetary relief in that case are not present, and such

relief was properly awarded below.

ARGUMENT

I. THE PRESENT CASE IS CONTROLLED BY THIS

COURT’S DECISION IN LOS ANGELES DEPART

MENT OF WATER & POWER v. MANHART, FROM

WHICH IT IS NEITHER FACTUALLY NOR

LEGALLY DISTINGUISHABLE.

A. Most of the arguments made by petitioners and

their amici were considered and rejected in Man

hart, and no persuasive justification for abandoning

that ruling is advanced in this case.

Despite the voluminous and repetitive briefs submitted

by petitioners and amici, the present case cannot per

suasively be distinguished from this Court’s recent ruling

in Los Angeles Department of Water & Power v. Man

hart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978). In that case the Court held

that a municipal employer’s mandatory pension plan

which required higher pay-period contributions from fe

male employees than from male employees, although pay

ing equal monthly benefits upon retirement, constituted

discrimination in compensation on the basis of sex which

5

violated Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. This con

clusion followed, the Court’s opinion states, despite the

actuarial validity of the generalization that women em

ployees, as a group, could be expected to draw monthly

pension benefits for a longer period of time than male

employees, as a group, if both retired at the same age.

1. “Equal Actuarial Value”.

As if Manhart had never been decided, petitioners and

their amici urge strenuously that Arizona’s pension plan

—which makes available to its male and female employ

ees an annuity option requiring equal pay-period contri

butions but affording women retirees smaller monthly

benefits than men who retire at the same age—is non-

discriminatory because the present actuarial value of the

promise to pay an annuity is equal for men and women

(based on the longer life expectancy of women as a

group). Thus, if petitioners are correct, Manhart’s in

terpretation of Title VII as proscribing unequal contribu

tions for equal monthly benefits based on sex does not

reach a plan which requires equal contributions for un

equal monthly benefits based on sex. Nothing in Manhart

suggests that the Court’s holding was so cramped.

Indeed, the “equal actuarial value” argument was ad

vanced in Manhart :

In essence, the Department is arguing that the

prima facie showing of discrimination based on evi

dence of different contributions for the respective

sexes is rebutted by its demonstration that there is

a like difference in the cost of providing benefits for

the respective classes.

435 U.S. at 716 (emphasis added). Los Angeles sug

gested that eliminating this “equal actuarial value” would

result in unfair “subsidization” of women’s pensions by

men:

. . . unless women as a class are assessed an extra

charge, they will be subsidized, to some extent, by

6

the class of male employees. It follows, according to

the Department, that fairness to its class of male em

ployees justifies the extra assessment against all of

its female employees.

Id. at 708-09 (footnote omitted). But Manhart rejected

these claims based on reasoning which is fully applicable

to the case at bar:

But the question of fairness to various classes af

fected by the statute is essentially a matter of policy

for the legislature to address. Congress has decided

that classifications based on sex, like those based on

national origin or race, are unlawful. Actuarial

studies could unquestionably identify differences in

life expectancy based on race or natioTial origin, as

well as sex. But a statute that was designed to make

race irrelevant in the employment market . . . could

not reasonably be construed to permit a take-home-

pay differential based on a racial classification.

Id. at 709 (emphasis added and citation and footnotes

omitted).

Manhart’s rejection of an “equal actuarial value” claim

was reinforced last Term by this Court’s decision in

Connecticut v. Teal, ----- U.S. ------, 73 L. Ed. 2d 130

(1982), which made clear that fairness to a class of per

sons defined according to race, sex or national origin

characteristics cannot justify unfairness to an individual

within such a group. There, Connecticut sought to avoid

judicial scrutiny for job-relatedness of a written test by

pointing to the “bottom line” results of its promotion

practices, even though the examination barred many more

minority than non-minority applicants from further con

sideration for promotion. Here, Arizona and its amici

suggest that lower monthly pension benefits for women

should be insulated from judicial scrutiny because the

present actuarial value of the annuity option to incumbent

female employees is the same as the present actuarial

value of the option to incumbent males. The argument is

7

nothing more nor less than an appeal to the “bottom line”

concept rejected by the Court in Teal.1

2. Adverse Selection.

The amici in support of petitioners have based much

of their concern over this case on the possibility that men

would disproportionately elect to take a lump-sum option,

rather than a unisex life annuity option that paid them

less than their lump sum could command on the open

market by purchasing a male life annuity with the lump

sum proceeds. The consequence of this anticipated phe

nomenon, say petitioners’ amici, would be the withdrawal

of men from payroll-deduction life annuity plans and the

destruction of the retirement life annuity market as it

now exists. If this spectre is laid to rest, much of the

force of the arguments made by those amici disappears;

indeed, the brief of the American Academy of Actuaries

(“Academy” ) admits this expressly at p. 11.

There are two important points to be made about these

arguments. First, the parade of horribles leading from

“adverse selection” to destruction of the life annuity

market is just as much hypothetical and unproven on this

record as it was when the same consequences were pre

dicted in Manhart. Second, there are available judicially

noticeable facts which suggest how highly unlikely it is

that these consequences will flow from an affirmance of

the judgment below.

1 In fact, the situation in Teal could be expressed in actuarial

terms. Under the facts of that case, black applicants for promotion

to the positions at issue had at least as good a chance of ultimate

selection as white applicants. If an actuary were to calculate the

average chances of selection for each race, one could then speak

of the “actuarial value” or “present value” of each black applicant’s

chance of selection as being the equivalent of the “actuarial value”

or “present value” of each white applicant’s chance of selection.

Focusing on their chances at the outset of the promotion process

would produce precisely the analysis which is urged with respect

to the case at bar by the American Council of Life Insurance

(“Council”). Council brief at pp. 8, 12-14.

8

In Manhart, some of the same amid predicted wide

spread “adverse selection” by males out of the pension

plan in question if women employees made equal contri

butions. 435 U.S. at 716 n.30. But, this Court noted,

“there ha[d] been no showing that sex distinctions [in

contributions] are reasonably necessary to the normal

operation of the Department’s retirement plan [to avoid

these consequences].” Id. Similarly, there is no evidence

on this record concerning the extent to which any ad

verse selection by men would be reasonably likely to oc

cur if Arizona chooses to contract for life annuities of

fering equal monthly benefits, and requiring equal

monthly contributions, for men and women. The briefs

of petitioners’ amid do not contain very much specific

data.2 Hence, Manhart is controlling and requires rejec

tion of the claim that fear of adverse selection justifies

the discriminatory pay-out to women.

Moreover, it seems self-evident from materials avail

able to the Court and subject to judicial notice that a male

employee would have to be extremely foolish to decide to

spend more in taxes to get his lump-sum payment and an

individual male life annuity than he would gain in the

size of his annuity payments.

For the sake of simplicity, let us hypothesize John Doe,

an unmarried male retiree with an adjusted age of 65

at the time of retirement. John Doe has $10,000 in tax

able income the year of his retirement, in addition to his

deferred compensation benefits in whatever form he de

cides to take them. He has seen the State’s description of

how the plan works, Exhibit 10, p. 5, to the Joint Stipu

lated Statement of Facts, and has decided to follow the

2 The fact that Arizona decided to stop offering- life annuities to

its employees after the decision below, Pet.Br. at 7, is not probative

of the effect an affirmance of the Ninth Circuit would have on other

employers. “Such actions in the face of litigation are equivocal in

purpose, motive and permanence.” Jenkins v. United Gas Corpora

tion, 400 F.2d 28, 33 (5th Cir., 1968) (footnote omitted).

9

example there stated, of deferring $1,200 in earnings a

year for 30 years, invested at a 10% growth rate. He has

$200,897 available at retirement. (Id.).

If he takes a life annuity with the Lincoln National

Life Insurance Company, Exhibit 3, second p. 6, to the

Joint Stipulation tells him that he would get a life an

nuity of $7.02 per month for each $1,000 he invests based

on the sexually disparate male table.3 A unisex value

would be somewhere between the male monthly payment

of $7.02 and the female monthly payment of $6.18 for

each $1,000 invested, a maximum difference of 84 cents.

Use of a unisex table could not possibly produce a monthly

payment less than $1,241.54.4

If John Doe were to take his $200,897 as a lump sum,

pay taxes on it and invest the remainder in an annuity

at the male rate of $7.02 for each thousand dollars in

vested, he would do significantly worse. At the 1982 tax

rates set forth in 26 U.S.C.A. § 1 (c) (1) (Supp. 1982), the

incremental tax on John Doe’s lump-sum payment would

be $95,534,5 leaving only $105,363 available for the pur

chase of an annuity at male rates on the open market.

At the $7.02 rate this would buy a male life annuity

with a monthly benefit of $739.65.®

3 This figure is for a straight life annuity, with no number of

months’ payments guaranteed, for the sake of simplicity.

4 The product of $6.18 and 200.897 thousand-dollar units is

$1,241.54.

3 Federal income tax on a taxable income of $10,000 would be

$1,233 with a marginal rate of 19%. Federal income tax on a tax

able income of $210,897 would be $96,767 with a marginal rate of

50%. Subtracting one figure from the other produces the fact that

the tax on the lump-sum payment would be $95,534. This does not

take the possibility of income averaging into account, nor does it

take the effect of State taxes into account, See note 7 infra.

8 The product of $7.02 and 105.363 thousand-dollar units is

$739.65.

10

In table form, John Doe’s choices are as follows:

Maximum possible loss from a unisex

table, if adverse selection by males

is 100% and unisex rates are the same

Adverse selection by male retirees is extremely unlikely

under these facts. While the tax costs of taking the lump

sum will vary from individual to individual, they will

clearly be substantial. Because adverse selection is un

likely, the unisex rates are likely to be substantially more

favorable than the present rates for women, and the

$168.75 figure in the above table would likely be consider

ably smaller.

Finally, any contention that males would take annuities

for fixed periods of years because they are aware of their

shorter life spans, and thus that a significant danger of

adverse selection remains even though the lump-sum op

tion is ruled out as a practical source of adverse selection,

would require very specific factual showings, based on the

experience of insurers, which are completely absent from

this record. The contention assumes that most men are

7 If income averaging were taken into account, assuming $15,000

in taxable income in each of the previous four years, our rough

calculation is that the additional Federal income tax on the lump

sum would still exceed $80,000. A tax cost of $80,000 would leave

John Doe with $120,897 to invest at the male rate of $7.02 per

thousand dollars invested. His monthly payment would be $848.70,

a figure which is $392.84 a month less than he would get from use of

the unisex table.

as current rates for women (84^ per

thousand dollars invested, with

an investment of $200,897)

$168.75/month less

than a male table

would produce 7

Cost of taking his lump-sum payment,

paying his taxes, and buying a male

annuity on the open market

($l,241.54/month less $739.65 a

month)

$501.89/month less

than a unisex table

would produce

11

willing to bet that they will die early; this flies in the

face of common understanding, just as it ignores the

potentially strong influence of the fear of outliving one’s

resources. The absence of record evidence, tested by

cross-examination, on such a doubtful contention under

scores the problems with the threadbare record on the

defenses asserted in this case.

3. The Accuracy of the Sexually Disparate Tables

in Measuring Longevity.

Closely related to the “actuarial value” argument is

the claim, made here and in Manhart, that because single-

sex mortality tables reflect real differences in longevity

between women and men, as a group, unequal life annuity

monthly benefits based upon such tables do not, amount to

differences in compensation based on sex. Manhart, of

course, flatly rejected this contention:

The Department’s argument is specious because

its contribution schedule distinguished only im

perfectly between long-lived and short-lived em

ployees, while distinguishing precisely between male

and female employees. In contrast, an entirely

gender-neutral system of contributions and benefits

would result in differing retirement benefits precisely

“based on” longevity, for retirees with long lives

would always receive more money than comparable

employees with short lives. Such a plan would also

distinguish in a crude way between male and female

pensioners, because of the difference in their average

life spans. It is this sort of disparity—and not an

explicitly gender-based differential—that the Equal

Pay Act intended to authorize.

435 U.S. a t 713 n.24.

Even if it were lawful to treat women as a class rather

than individually, any employer seeking to justify the use

of sexually disparate annuity benefits on the basis of

greater longevity for women as a class than for men as a

class would still have the burden of proving that its par

ticular sexual disparities were in fact an accurate reflec-

12

tion of such greater longevity for women as a class.

Otherwise, as the National Association of Insurance Com

missioners points out, an inaccurate set-back figure would

enable insurance companies to earn profits from unfair

discrimination. Insurance Commissioners’ brief at 25.8

The briefs filed by various amici in support of petition

ers carry the implication that the sexually disparate mor

tality tables used by the insurance industry are based on

scientific measurements. From the information before

this Court, and from Census Bureau information which

can properly be the subject of judicial notice, such an

implication would not be correct.

None of the mortality tables used for life annuity

benefits under the Arizona plan contains any separate

figures for female mortality. See the exhibits to the

Joint Stipulated Statement of Facts.0 All of them use

male mortality figures, and set women back a number of

years which appears to be arbitrary. Thus, a male will

receive annuity benefits based on his actual adjusted age

at retirement, but a woman will receive annuity benefits

based on a male’s benefits as if the male had retired at

an age a constant number of years younger than the

woman’s actual adjusted age. “Thus a 65 year old woman

is treated as being 59 years old and her monthly annuity

based on that age, while a 65 year old male has his

monthly annuity based on age 65.” JA 12. In the insur

ance industry generally, the amount of the setback varies

from plan to plan, and is commonly greater for annuities

8 While the Council argues that respondents never challenged the

accuracy of the tables used, Council brief at 12. n.2, Arizona was the

party attempting to justify an explicit sexual classification and it

therefore had the burden of proving the accuracy of the tables

used in its plan.

9 The stipulation describes the Lincoln National LIC plan as con

taining a separate table for women, JA 12, but exhibit 3 uses only a

male table with a setback for women. Perhaps there was an earlier

Lincoln National LIC plan.

13

(where the setback harms women) than for life insur

ance (where the setback helps women). The following

table shows the differences in this supposedly “scientific”

assessment of mortality:

Amount of Setback

for Women on Male Source of

Plan Mortality Tables Information

Usual annuity plan

(setback harms women

by giving them lower

monthly benefits )

6 years Amiens brief of National

Ass’n of Insurance

Commissioners at 25

National Investor

National Investors LIC

(presumably a different

policy than the one de

scribed in the stipulation)

6 years JA 12

5 years Exhibit 4, at the pages

marked GA-AA in the lower

right corner

ITT LIC

Hartford Variable Annuity

LIC

5 years Exhibit 7, p. 8

4 years Exhibit 6R, p. 10

Lincoln National LIC

Variable Annuity LIC

Usual life insurance

plans (setback favors

women by charging them

lower rates )10

4 years Exhibit 3, second p. 6

4 years Exhibit 5, p. 5

3 years Amicus brief of National

Ass’n of Insurance

Commissioners at 25.

To make matters worse, the U.S. Census Bureau’s

tables for “Expectation of Life at Single Years of Age”

10 The fact that life insurance has only a three-year setback for

women while annuities commonly utilize a much larger setback is

of particular interest, because life insurance is commonly purchased

during the earlier periods of life when the male/female differences

in life expectancy are greater, and annuities are commonly pur

chased during the later periods of life when the male/female differ

ences in life expectancy are smallest. (See the table below). Under

a nondiscriminatory system, one would expect to see a larger life

insurance setback resulting In lower premiums for women, and a

smaller annuity setback resulting in lesser reductions in monthly

benefits: in short, one would expect to see the reverse of the present

system.

14

make clear that female mortality cannot be set accurately

at a constant number of years below male mortality. Sex

ual differences in longevity decrease substantially over

time, and using an average difference in longevity which

is accurate for one age will greatly overstate the average

differences in longevity at a later age. The following

table shows the differences in longevity at various ages

for men as a class, compared with women as a class, for

1973 (close to Arizona’s adoption of its plan) and for

1978 (the most recent table published) : 11

Sexual Differences in Life Expectancy

at the Ages Stated (Female Life Ex

pectancy Minus Male Life Expectancy)

Years of Age 1973 Data 1978 Data

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

6.9 years

6.6 years

6.4 years

6.2 years

6.0 years

5.7 years

5.3 years

4.7 years

4.1 years

3.2 years

2.3 years

1.5 years

1.0 year

7.0 years

6.6 years

6.5 years

6.3 years

6.1 years

5.9 years

5.5 years

5.0 years

4.4 years

3.6 years

2.8 years

2.0 years

1.4 years

In addition to the unfairness to individual women of

treating women as a class and comparing them with men

as a class, the life annuity tables for which Arizona con

tracted did not even treat the class of women fairly. Ari

zona’s “actuarial equivalent” argument would not have

allowed a starting setback for women at the normal re

tirement age of 65 greater than 4.1 years as of the time

11 1973 data: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Vital Statistics of the

United States, 1973: Volume 11-Section 5: Life Tables, Table 5-3

at p. 5-12 (1975). 1978 data: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Vital

Statistics of the United States, 1978: Volume II-Section 5: Life

Tables, Table 5-3 at p. 5-13 (1980).

15

it adopted its plan, yet the tables it agreed to use in

cluded constant setbacks of 5 years and 6 years. Its ar

gument would require that the tables used recognize the

substantial narrowing of the sexual differences in average

longevity as retirees become older, by providing only a

maximum 3.2-year setback for those surviving to age 70,

a 2.3-year setback for those surviving to age 75, etc., or

by some other means. Yet the sexually disparate tables

for which it bargained use constant setbacks. When Ari

zona’s own argument for class-based comparisons is put

side-by-side with its practices, it is clear that Arizona is

requiring women as a class to subsidize men as a class.

B. Arizona’s pension plan cannot be sustained as being

within the “open market” exception of Manhart.

The remaining contentions of petitioners and their

amici seek to justify Arizona’s pension plan incorporating

sex-based life annuities as simply reflective of what is

available on the “open market” and thus within the ex

ception enunciated in this Court’s decision in Manhart;

or in the alternative, as nondiscriminatory because the

“open market” does not allow Arizona to purchase unisex

life annuities for its employees or because female workers

may elect a nondiscriminatory “lump sum” option or an

nuity option for a fixed term of years. Both of these ar

guments are legally without merit and, in addition, are

based upon erroneous factual assumptions about life an

nuity policies available on the “open market.”

1. Arizona’s Plan Does Not Fit Within the “Open

Market” Exception of Manhart Because the State

Did Far More Than Allow Employees to Pur

chase Whatever Life Annuity Policies Were

Available on the “Open Market”.

At the end of its discussion of the liability question

in Manhart, this Court limited the reach of its holding

by adding:

Although we conclude that the Department’s prac

tice violated Title VII, we do not suggest that the

16

statute was intended to revolutionize the insurance

and pension industries. All that is at issue today is

a requirement that men and women make unequal

contributions to an employer-operated pension fund.

Nothing in our holding implies that it would be un

lawful for an employer to set aside equal retirement

contributions for each employee and let each retiree

purchase the largest benefit which his or her accum

ulated contributions could command in the open

market. Nor does it call into question the insurance

industry practice of considering the composition of an

employer’s work force in determining the probable

cost of a retirement or death benefit plan.

435 U.S. at 717-18 (footnotes omitted). Petitioners and

their amici contend that Arizona’s plan fits within this

“open market” exception to Manhart’s interpretation of

Title VII, but their argument gives this exception a sig

nificance out of all proportion to its function in Manhart.

Though self-evident, it bears noting that Arizona did

not offer its employees the type of pension arrangement

described by the Court in Manhart. It did not offer all

employees, male and female, only the opportunity to take

a lump-sum payout at retirement which the employees

would then have to convert to a life annuity on the “open

market.” Nor did it inform its employees that they could

elect payout in the form of whatever life annuity they

could contract for on the “open market” at the time they

elected to participate in the plan. Instead, the state ap

paratus affirmatively selected a limited number of life

annuity plans—all based on single-sex mortality tables'—

to make available to its employees. Thus, even if a fe

male employee of the state were able to find an annuity

based on a unisex mortality table on the “open market,”

she is precluded under the Arizona plan from electing

that payout option if it is not one of the plans or com

panies pre-selected by the Governing Committee. The ad

vantages of tax deferral after the age of retirement and

of group bargaining power are thus lost to the individual

17

employee who seeks to avoid the discrimination inherent

in sex-based annuity tables.

It is one thing for an employer to institute a retire

ment savings plan, return accumulated contributions to

each employee at retirement, and allow each retiree to do

with the savings whatever he or she wishes, without any

further contact from the employer. It is quite another

thing for the employer to adopt a plan limiting the choices

of its employees, and in that process contract for only

one type of life annuity with explicitly discriminatory

conditions, thus imposing a heavy burden in lost tax de

ferral or reduced security for any woman desiring to

avoid the explicit sexual discrimination. Manhart’s im

munity for the employer who merely makes available the

“open market” to its retirees simply does not cover the

conduct at issue here.

Petitioners’ related argument that they did not intend

to discriminate because the insurance companies with

which they contracted, rather than the state, initiated

the sexually disparate benefit tables for life annuities, is

equally groundless. It is settled law that both parties to

a discriminatory contract are liable for any discrimina

tory provisions which it contains, regardless of who init

ially sugested the discriminatory provisions.12

Petitioners also deny intent on the basis of the decision

in Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256 (1979), but that case emphasized the ab-

12 The leading- case is Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791,

799 (4th Cir.), cert, dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971). See also

Williams v. New Orleans Steamship Ass’n, 673 F.2d 742, 750-51

(5th Cir. 19&2); Williams v. Owens-Illinois, 665 F.2d 918, 926

(9th Cir., 1982); Farmer v. ARA Services, 660 F.2d 1096, 1104 (6th

Cir., 1981); Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 635 F.2d 1007, 1014

(2nd Cir., 1980), cert, den., 452 U.S. 940 (1981); United States v.

N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354, 379-80 (8th Cir., 1973) ; Rosen v.

Public Service Electric and Gas Co., 477 F.2d 90, 95 (3rd Cir., 1973),

and cases there cited.

18

sence of an explicit gender-based classification in finding

that there was no discriminatory purpose. 442 U.S. at

267-69, 273-74. In the absence of such a classification, it

was necessary to look further for evidence of discrimina

tory intent. The case does not help petitioners, because

the discrimination here was explicit.

Finally, petitioners urge that the district court did not

find discriminatory purpose. The statement of the dis

trict court was that the petitioners’ agreement with the

insurers “is somewhat less than the purposeful invidious

gender-based discrimination necessary for a finding that

the compensation plan violates the equal protection clause”.

Pet. App. A-21. With respect, the district court erred

on the applicable standard for determining discrimina

tory intent. No showing of malevolance—of specific in

tent to injure the disfavored sex—is required. In Missis

sippi University for Women v. Hogan, ----- U.S. ------,

73 L. Ed. 2d 1090, 1098 (1982), this Court held that even

a motive to protect women may result in a violation of

the equal protection clause. The “recitation of even a

benign, compensatory purpose” may not be enough to save

a facially discriminatory provision. 73 L. Ed. 2d at 1100,

quoting Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636, 648

(1975). Here, the gender classification harms women.

Petitioners cannot escape the conclusion that they have

intentionally discriminated against women.

2. Arizona’s Plan Does not Reflect the “Open

Market,” Because the State Could Have Con

tracted for Unisex Table Life Annuities.

Apparently recognizing that Arizona’s pension scheme

does not come within the literal language of the Manhart

“open market” exception, petitioners and their amici

nevertheless contend that the plan should be sustained

under Title VII because it is the functional equivalent of

the exception in assertedly offering employees a fair re

flection of what is available on the open market. See, e.g.,

Petitioners’ Brief at pp. 14-15. In essence, petitioners

raise an affirmative defense of impossibility, and it was

19

accordingly their burden to adduce evidence supporting

the defense.13 If that evidence is not contained in this

record, then the judgment below must be sustained.

13 When any defendant seeks to set up an affirmative defense,

it has the burden of persuasion in establishing the facts on which

the defense rests. Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252, 269 n .ll (1980)

(“duress is an affirmative defense to be pleaded and proved by the

party attempting to rely on it” ) ; United States v. Phosphate Ex

port Ass’n, 393 U.S. 199, 203 (1968) (a party raising the defense

of mootness has a “heavy burden of persuasion”) ; Guzman v.

Pichirilo, 369 U.S. 698, 700 (1962) (an owner attempting to escape

liability for the unseaworthiness of his vessel by showing that he

has been relieved of his obligation “has the burden of establishing

the facts which give rise to such relief”) ; United States v. Poland,

251 U.S. 221, 227-28 (1920) (status as a bona fide purchaser “is an

affirmative defense which he must set up and establish.” ).

In Title YII cases, the contention that a challenged test or edu

cational requirement is job-related raises an affirmative defense,

and the employer then has the burden of persuasion in proving the

validity of the practice. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405, 425-36 (1975); Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 431-

36 (1971). An employer with a facially sexually discriminatory

policy of refusing to employ women in particular positions has the

burden of proving a bona fide occupational qualification. E.g.,

Hardin v. Stynchcomb, 691 F.2d 1364, 1370-72 (11th Cir. 1982),

and cases there cited.

It is clear that the burden in question is a burden of persuasion

and not merely the burden of production or of articulation discussed

in Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248

(1981). In Griggs, the employer rested on testimony articulating

the company’s judgment that the challenged requirements would

generally improve the overall quality of the work force. This Court

rejected the articulation as insufficient and held that “Congress has

placed on the employer the burden of showing that any given

requirement must have a manifest relationship to the employment

in question.” 401 U.S. at 431-32. Similarly, the degree of the

factual detail Albemarle held employers must show in order to

establish validity is inconsistent with a mere requirement of pro

duction or of articulation. 422 U.S. at 431-36. In Connecticut v.

Teal, 73 L.Ed. 2d a t 140, this Court stated that respondents’ rights

were violated by the challenged test “unless petitioners can demon

strate that the examination given was not an artificial, arbitrary,

or unnecessary barrier” by proving it was valid. (Emphasis sup

plied) .

20

The affirmative defense of impossibility raised by Ari

zona requires at a minimum three factual showings: (1)

that no companies offered unisex life annuity benefits,

(2) if so, that Arizona’s bargaining power would not

have been sufficient to induce companies not then offering

such benefits to agree to provide them to Arizona, and

(3) if so, that there would have been no other means by

which Arizona could have offered life annuities to its

employees on the basis of equal monthly payments for

men and women of the same age.

Arizona’s sole factual support for its impossibility con

tention rests on a strained reading of the parties’ agreed

factual statement.14 After a detailed discussion of the

specific named companies Arizona had selected for inclu

sion in its plan, JA 7, after a discussion of the additional

named companies added to the plan or dropped from it,

JA 8-9, after a description of the exhibits to the agreed

statement containing the specific provisions offered by

these named companies {Id.), and after a generalized de

scription of the life annuities offered by the named com

panies participating in the plan, there is a paragraph

containing the isolated sentence on which Arizona pins

all its hopes, JA 10. This paragraph begins by referring

to the “mortality tables which are published in the con

tract with the particular company”, and continues in

pertinent part :

. . . The amounts received are determined by the

use of actuarial tables published by the particular

company. All tables presently in use provide a

14 In their Reply in support of their petition for certiorari, peti

tioners sought to draw comfort from the statement in the district

court by an attorney for respondents that he did not know whether

there were companies in Arizona prepared to offer plans based on

unisex tables. Reply at 2. Petitioners have wisely chosen not to

rely on this statement in their brief on the merits; a confession

of this lack of knowledge by plaintiffs’ counsel does come close to

satisfying the defendant’s burden of proving impossibility.

21

larger sum to a male than to a female of equal age,

account value and any guaranteed payment period.

JA 10. Arizona stresses the second sentence in the above

quotation, insisting that it refers to all life annuity tables

in existence, not merely to the tables in the plans it ap

proved.16. Respondents disagree.16

Seen in context, the normal and natural meaning of the

stipulation is only that the tables used in the plans ap

proved by petitioners are sexually disparate. Cf. Lynch v.

Alworth-Stephens Co., 267 U.S. 364, 370 (1925) (“the

plain, obvious and rational meaning of a statute is always

to be preferred to any curious, narrow, hidden sense that

nothing but the exigency of a hard case and the ingenuity

and study of an acute and powerful intellect would dis

cover.” ), quoted in Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840,

848 (1976).

The amicus brief of the American Council of Life In

surance (“Council”) states at 10 and 24 that the Council

“is not aware of any private insurance companjr which

offers an annuity plan which does not- calculate benefits

according to sex-specific mortality tables.” Arizona’s

reply in support of its petition for certiorari-—but not its

brief on the merits—relies on a similar statement by the

Council in its amicus brief to the Ninth Circuit to sup

port its defense of impossibility. Putting aside the seri

ous question whether an affirmative defense can ever be

established in the absence of any facts of record what

soever, simply on the basis of a statement in an amicus

brief, the Council’s statement is insufficient to establish

even the first of the three showings Arizona would

logically have to make in order to sustain its impossibility

defense. First, if the Council’s statement means that it

15 As if hopeful that mere repetition would make the assertion

stick, Arizona has repeated this representation in its Brief at 3,

5, 9, 11, 14, 15, 17, 20, 26, and 27.

16 See respondents’ Opposition to the petition for certiorari at 1.

22

is unaware of any insurance companies willing to pro

vide employers with group life annuity plans based on

unisex tables, its knowledge is demonstrably incomplete.

The Lincoln National Life Insurance Company—one of

the companies used by Arizona in its plan—has informed

amici in response to a telephone call that, if the potential

customer’s business is large enough, it is willing to provide

group life annuities providing the same monthly annuity

payments to men and women of the same age who have

invested the same amounts. It does this on the basis of

unisex tables which take into account the ratio of male

employees to female employees.17 Moreover, the Minnesota

Mutual Life Insurance Company and the Northwestern

National Life Insurance Company provide group life an

nuities to faculty members of the University of Minne

sota, based on unisex tables providing equal monthly

benefits for men and women of the same age who invest

the same amounts.18 Arizona’s plan allowed for the use

of out-of-State insurance companies,19 and there is no rea-

17 See the affidavit of Richard T. Seymour, lodged with the Clerk.

See n. 20, infra.

18 The Chronicle of Higher Education, Vol. 25, No. 7, October 13,

1982, at 25-26.

1&Rule R2-9-07(A) of the Governing Committee for Tax De

ferred Annuity and Deferred Compensation Plans, Exhibit 1 to the

Joint Stipulated Statement of Facts, imposes no geographic limita

tions on the insurance companies offering annuities under the plan.

By contrast, part (B) of that rule limits the banks, savings and

loan associations and credit unions offering savings accounts under

the plan to those having their principal offices in Arizona. Licenses

to do business within a State are, of course, necessary, but these

are not difficult to obtain. In point of fact, all of the insurance

companies offering life annuities under the plan have their corporate

headquarters outside of Arizona. Lincoln National LIC’s home

office is in Fort Wayne, Indiana (Exhibit 3); National Investors

LIC’s home office is in Little Rock, Arkansas (Exhibit 4) ; Variable

Annuity LIC’s home office is in Houston, Texas (Exhibit 5); Hart

ford Variable Annuity LIC is a South Carolina company with

23

son to suppose that Arizona could not have obtained sim

ilar annuities either from Lincoln National or from the

companies doing business with the University of Minne

sota. Second, if the Council’s statement be taken to mean

only that sex-specific mortality tables would have to be

considered in setting up the overall level of benefits under

a unisex table,20 this would still not offer a legal defense

for Arizona’s explicit agreement for lesser monthly bene

fits to women.

Neither Arizona nor the amici which have filed briefs

in its support have addressed the other facts essential to a

showing of impossibility. The Council emphasizes that

the market power of Arizona and of other employers en

ables them to bargain for—and to obtain—annuity bene

fits substantially better than those available to individuals.

Brief at 24. No reason appears why Arizona could not

have bargained for, and obtained, tailor-made life an-

nuity plans which offered equal monthly payments to

men and women. Arizona has not even tried to show that

it raised the question in its bargaining.

executive offices at Hartford, Connecticut (Exhibit 6R ); and ITT

Life Insurance Corporation’s home office is in Thorp, Wisconsin

(Exhibit 7).

20 Manhart recognized this possibility, 435 U.S. at 718. The

Council recognizes this possibility although it is worried by the

problem of possible fluctuation in workforce composition, Brief at

21-22. The American Academy of Actuaries (“Academy”) by con

trast, urges that provision of equal monthly life annuity payments

would cause little difficulty or expense in the larger defined benefit

plans, even asserting that the “normal” monthly pension benefit

is already equal for similarly situated men and women. Brief at

19-20, 22-23. Its concern is with smaller defined benefit plans, but

no reasons appear in its brief why smaller employers could not be

combined into larger groups for purposes of risk-pooling, as is

done with health insurance. Moreover, the larger the plan, the less

risk of sharp fluctuations in male/female ratios. Council Brief at

21 n.12. The Academy seems to state that an affirmance of the

Ninth Circuit would cause little problem for defined-contribution

plans, except for the problem of adverse selection. Brief at 16-18.

24

Nor has Arizona shown that it had no choice but to Use

existing insurance companies to provide annuities.

Other devices, such as the establishment of a State gov

ernmental corporation to sell annuities and make monthly

benefits, may have been feasible. Arizona has simply not

met its burden.21

Petitioners are also precluded, as a matter of law, from

seeking to justify the inclusion of the discriminatory life

annuity option in their plan on the basis of the “lump

sum” payout option available to women enrolled in the

plan. From the above discussion, it is clear that the lump

sum option imposes a heavy price on its exercise. The

option of an annuity for a fixed period of years should be

even less attractive for women than for men. Neither of

these payout alternatives constitutes a nondiscriminatory

option available to women which can sustain Arizona’s

pension plan.

Just last Term, this Court held that a male was suf

ficiently disadvantaged by a rule barring men from a

State-supported nursing school in his hometown to be able

to mount a challenge to the rule under the Equal Pro

tection Clause. He had the “nondiscriminatory option”

of attending a different State-supported nursing school in

a different area, but would be disadvantaged by the in

convenience of having to drive “a considerable distance”

from his home and by being deprived of credit for ad

ditional training working while attending school. Mis

sissippi University for Women v. Hogan, 78 L. Ed. 2d at

1098 n.8. The so-called “nondiscriminatory option” here

21 As. to the claims of “revolution”, the brief of the American

Academy of Actuaries—which takes no position on the ultimate issue

herein—makes clear that the insurance and pension industries can

accommodate an affirmance of the Ninth Circuit, as long as the de

cisions of the courts take into account the effects of differences

in various types of pension and annuity benefits. This can. best be

done on a case-by-case basis, inasmuch as variations among plans

seem to be legion.

25

would involve far greater cost or, in the case of fixed-

term annuities, far less security, than the challenged

option. The disadvantages here are much more substan

tial than those found sufficient for the challenge in

Hogan.

IL BECAUSE MANHART GAVE EMPLOYERS ADE

QUATE WARNING OF THE TITLE VII REQUIRE

MENTS FOR PENSION PLANS, THE AWARD OF

MONETARY RELIEF BELOW WAS JUST AND

PROPER.

It seems evident that an intentional discriminator has

no good objection to the entry of a back pay award

against it. While Arizona argues that one of the purposes

of the program was to take advantage of tax incentives

while avoiding any non-administrative expense to the

State, the way to achieve that goal was to have avoided

unlawful discrimination.22

Arizona’s objection to a back pay award is further

undermined by its having ignored the extraordinary

“grace period” this Court allowed employers with dis

criminatory pension schemes in Manhart. The Court

stated that there was no reason to believe that employers

would have failed to abide by Title VII if they had under

stood the law’s application to pension systems, and added:

There is no reason to believe that the threat of a

backpay award is needed to cause other administrators

to amend their practices to conform to this decision.

435 U.S. at 720-21. If Arizona had heeded the necessary

application of the Manhart decision to discriminatory

22 The expense of a monetary recovery will in any event be light;

the plan is a relatively new one and only four women selecting

the life annuity option had retired as of the time of the stipu

lation. JA 6.

26

benefits and had cleared up its problem within a reason

able time after announcement of the decision, it would

clearly have been entitled to a clean slate in terms of

monetary relief.

Like most other employers, however, Arizona decided

to ignore this Court’s offer of a grace period and to fight

every step of the way against conforming its policies to

the requirements of Title VII.23 The certain prospect of

back pay relief is as essential to obtain compliance in the

area of annuity benefits as it is in other areas of em

ployment.

Manhart’s denial of back pay was based on a premise

shown by experience to have been faulty. To allow an

other grace period would reward intransigence and dimin

ish respect for the law’s demands. To give recalcitrant

employers such as Arizona even the benefit of a grace

period to the date of the Manhart decision would give to

employers who have proven their recalcitrance a benefit

based on an assumption of good faith. This would ef

fectively postpone the effective date of Title VII to the

date of the Manhart decision and frustrate the purposes

of Title VII.

28 Despite the 1978■.'decision of this -Court in Manhatrt, and despite

the 1981 decision of the Southern District of New York that such

practices are illegal, for example, the City of New York still de

ducts a higher percentage of its female employees’ pay than, of

similarly situated male employees’ pay for its retirement plan, and

still provides lower monthly retirement allowances to female retirees

than to similarly situated male retirees over the course of their

lives. See Women in City Government United v. City of New York,

515 F.Supp. 295 (S.D.N.Y. 1981).

27

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the Ninth Circuit should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Maximilian W. Kempner

R ichard C. Dinkelspiel

Co-Chairmen

N orman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

N orman J. Chachkin

Beatrice Rosenberg

R ichard T. Seymour *

Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

520 Woodward Building

733 Fifteenth Street, NW.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Barry L. Goldstein

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

806 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 638-3278

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Counsel of RecordJanuary 7,1983