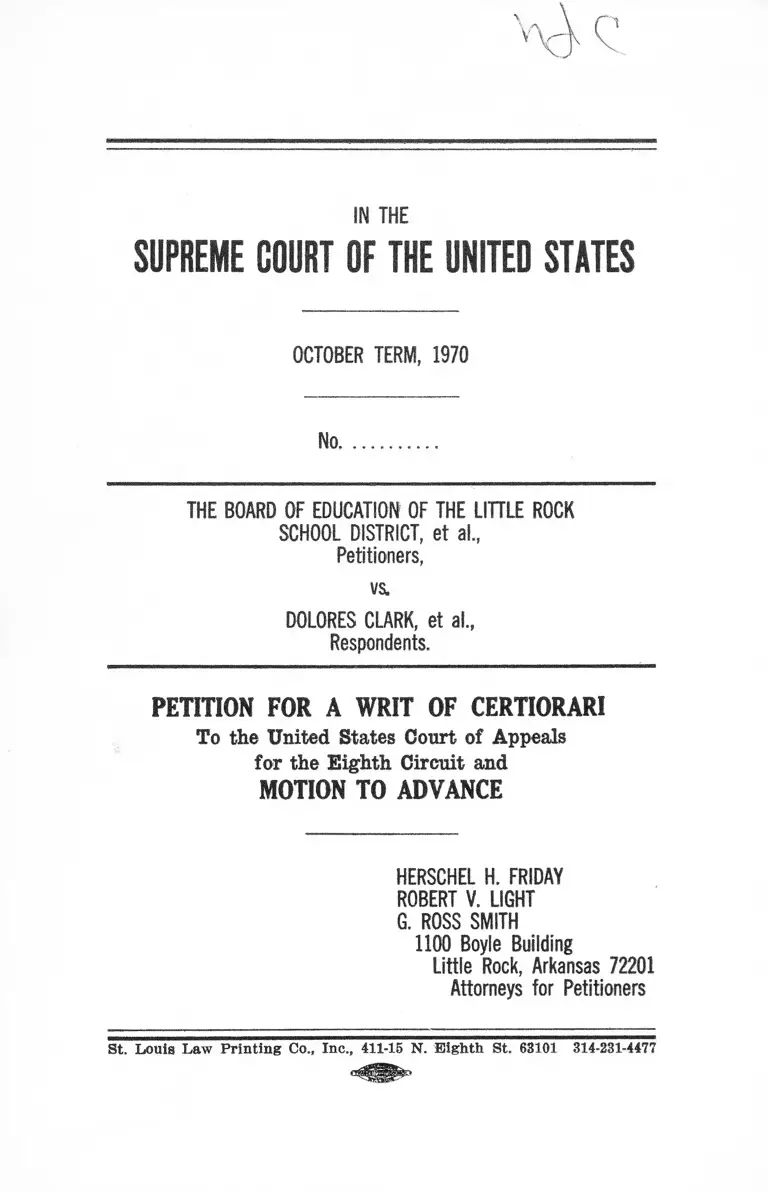

The Board of Education of the Little Rock School District v. Clark Petition for a Writ of Certiorari and Motion to Advance

Public Court Documents

July 15, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The Board of Education of the Little Rock School District v. Clark Petition for a Writ of Certiorari and Motion to Advance, 1970. 03dac9f8-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/27d1d45f-42f2-412d-8b81-3de9669dc017/the-board-of-education-of-the-little-rock-school-district-v-clark-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-and-motion-to-advance. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

No.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE LITTLE ROCK

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

DOLORES CLARK, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

To the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit and

MOTION TO ADVANCE

HERSCHEL H. FRIDAY

ROBERT V. LIGHT

G. ROSS SMITH

1100 Boyle Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Attorneys for Petitioners

St. Louis Law Printing Co., Inc., 411-15 N. Eighth St. 63101 314-231-4477

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Motion to A dvance............................................................. 1

Prayer ....................... 3

Opinions Below ............................................. 3

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 4

Questions Presented........................................................... 4

Constitutional Provisions Involved .................................. 5

Statement ............................................................................ 5

1. Proceedings before the District C ou rt................... 5

2. The Decision of the Court of A ppeals.................. 8

Reasons for Granting the W r it ....................................... 9

Conclusion .......................................................................... 17

Appendix A— Opinion of Court of Appeals for the

Eighth C ircu it................................................................. A -l

Appendix B—Judgment ....................................................A-26

Appendix C— Opinion of the District C ou rt.................A-27

Appendix D—Decree of the District C ou rt.................. A-58

Table of Cases Cited

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U. S. 19 (1969) ..........................................................9,13,16

Beckett v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 308 F.

Supp. 1274 (D. C. Va. 1969)......................................... 13

Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind., 213 F. Supp. 819

(N. D. Ind.), aff’d 324 F. 2d 209 (7 Cir. 1963), cert,

denied, 377 U. S. 924 ......................................... .. .12,13

11

Bivins v. Bibb Comity, . . . F. Supp. . . . (N. D. Ga.,

January 21, 1970) ............................................................. 13

Broussard v. Houston Ind. S. Dist., 395 F. 2d 817 (5

Cir. 1968), petition for rehearing en banc denied,

403 F. 2d 34 (5 Cir. 1968)............................................... 13

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954).. .9,11

Carter v. West Feliciana School Board, 396 U. S. 290

(1970) ....................... 13

Clark v. Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 661 (8 Cir.

1966) ................................................................................. 6

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958)............................... 2

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 55

(6 Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 389 U. S. 847 (1967).. .11,13

Downs v. Board of Ed. of Kansas City, 336 F. 2d 988

(10 Cir. 1964) ................................................................. 13

Ellis v. The Board of Public Instruction of Orange

County, Florida, 423 F. 2d 203 (5 Cir. 1970)............14-15

Ex Parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1 (1942)............................... 2

Graves v. Board of Education of North Little Bock,

299 F. Supp. 843 (D. C. Ark. 1969)............................ 14

Green v. County School Board, 391 U. S. 430 (1968). .6,13

Hilson v. Washington County, . . . F. Supp. . . . (M. D.

Ga., January 28, 1970) ................................................. 14

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

409 F. 2d 682 (5 Cir. 1969)........................................... 13

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis, 420 F.

2d 546 (6 Cir. 1970) ....................................................... 14

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 397 U. S. 232 (1970) ........................................... 14

Rosenberg v. United States, 346 U. S. 273 (1953)........ 2

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Sys

tem, . . . F. 2d . . . (5 Cir., May 5, 1970) 15

I l l

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F. 2d

261 (1 Cir. 1965) .............................................................

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 369 F. 2d

29 (4 Cir. 1966) ...............................................................

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

. . . F. 2d . . . (4 Cir., May 26, 1970), cert, granted

No. 1713, 38 LW 3522 (June 29, 1970)........................2,

Thornie v. Houston County, . . . F. Supp. . . . (M. D.

Ga., January 21, 1970) .................................................

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

Dist., 406 F. 2d 1086 (5 Cir. 1969).............................

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

Dist., 410 F. 2d 626 (5 Cir. 1969)...............................

United States v. Jefferson Co. Bd. of Educ., 372 F. 2d

836, 879 (5 Cir. 1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F. 2d 385

(5 Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U. S. 840 (1967 )....

United States v. State of Georgia, . . . F. Supp. . ..

(N. D. Ga., December 17, 1969)...................................

Statutes Cited

28 U. S. G, 1254(1) ...........................................................

42 U. S. C., 2000-c(b) .......................................................

Constitution Cited

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment ...............................................

Congressional Record Cited

13

13

15

14

13

13

11

13

4

12

5

110 Cong. Rec. 12715

110 Cong. Rec. 12717

12

12

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

No,

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE LITTLE ROCK

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

DOLORES CLARK, et al.,

Respondents.

MOTION TO ADVANCE

Petitioners respectfully move that the Court advance

its consideration and disposition of this case. It presents

issues of national importance which require prompt reso

lution by this Court for the reasons stated in the annexed

petition for a writ of certiorari. The public school sys

tems of the nation face conditions of impending confusion

and chaos as a result of conflicting decisions of the Courts

of Appeals and of the District Courts respecting the obli

gations of the school districts pertaining to assignment

of students and other phases of their operations in the

1970-71 school year. It would therefore be desirable for

the issues to be decided before the beginning of the next

school term which is September 8, 1970 in petitioners’ dis

2

trict in order to guide the many courts and school boards

now making plans for the coming year and to avoid the

occasion for reorganizations of systems after the 1970-71

school term is underway.

The issues herein are closely related to those in Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, No. 1713,

cert, granted, 38 LW 3522 although perhaps the record

in this case brings into sharper focus the fundamental

issue of the constitutional validity of the neighborhood

school system. On June 29, 1970 the Court expressly de

ferred decision on motions to expedite in that case similar

to the motion here made.

Wherefore, petitioners pray that the Court:

1. Advance consideration of the petition for writ of cer

tiorari and any cross-petition or other response thereto

for determination at the earliest feasible time.

2. If the Court determines to grant the petition for cer

tiorari, to direct an expedited briefing schedule and to

set the case for argument at a special term before the

commencement of the 1970-71 school year. Special terms

were convened to consider Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1

(1958); Rosenberg v. United States, 346 U. S. 273 (1953);

and Ex Parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1 (1942).

Respectfully submitted

HERSCHEL H. FRIDAY

ROBERT V. LIGHT

G. ROSS SMITH

1100 Boyle Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Attorneys for Petitioners

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

No.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE LITTLE ROCK

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et a!.,

Petitioners,

vs,

DOLORES CLARK, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

To the United States Court of Appeals

For the Eighth Circuit

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to re

view the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit entered in this case on May 13,

1970.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit and the dissenting opinion of Judges

Van Oosterhout and Gibson are not yet reported. They

are set forth in the Appendix, pp. A-l-A-25. The decision

and decree of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas, Western Division, are un

reported. They are set forth in the Appendix, pp. A-27-

A-59.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit was rendered May 13, 1970. The juris

diction of this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Where the record discloses that a metropolitan school

district assigning students to schools near their homes by

fairly drawn attendance zones can significantly increase

the racial balance in each school only by providing com

pulsory transportation to schools long distances from their

homes, does the Constitution require the geographical zon

ing system to be abolished and a system of compulsory

busing be adopted?

2. Where a school district has desegregated its faculty so

that in no school do the number of Negro teachers exceed

50 per cent, where students are assigned on a fairly drawn

geographical zoning system to schools near their homes,

and where students so assigned to a school where their

race is in a majority have the option to transfer to a school

where their race is in a minority, is the Constitution vio

lated because such system fails to achieve some degree of

racial balance in each school?

3. Where a school district has adopted a fairly drawn geo

graphical zoning system for neighborhood schools, does

the Constitution require that students so assigned to a

school where their race is in the majority be given an

option to transfer to a school where their race is in the

minority ?

4. Where a school district has adopted a fairly drawn

geographical zoning system for neighborhood schools,

does the Constitution require or permit the district court

to order gerrymandering of zone lines solely for the pur

pose of producing greater racial balanice at certain

schools ?

5. Where a school district has adopted a fairly drawn

geographical zoning system for neighborhood schools,

does the Constitution authorize the district court to order

implementation of a plan designed to racially balance the

schools in one section of the district although it is un

disputed in the record that the results would be contrary

to those intended?

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

— 5 —

STATEMENT

1. Proceedings before the District Court.

Petitioners are the members of the Board of Education

of the Little Eock School District. This is a metropolitan

school district operating 42 schools for the benefit of

23,113 students. In July, 1968, the latest date such data

appears in this record, there were 15,063 white students

and 8,050 Negro students.

This school desegregation suit was originally filed on

November 4, 1964 in the Eastern District of Arkansas by

five Negro children and their parents who alleged a de

nial of equal protection of the laws arising out of the

district’s assignments of students pursuant to the Arkansas

Pupil Assignment Law. Plaintiffs sought the adoption

of a zoning system that would ‘ ‘ generally assign all pupils

to the schools nearest their residence.” On January 14,

1966, the district court, in an unreported opinion, ap

proved a transition by the school district to a freedom of

choice desegregation plan. The freedom of choice plan

was approved in substance, but with minor modifications,

by the Court of Appeals. Clark v. Board of Education,

369 F. 2d 661 (8 Cir. 1966). On June 25, 1968, after this

Court’s May 27, 1968 decisions in Green v. County School

Board, 391 U. S. 430 (1968), and companion cases, the

plaintiffs filed a Motion for Further Relief asking, inter

alia, that the school district be required to submit a de

segregation plan other than freedom of choice. After a

response by the school district, a hearing was commenced

on August 15, 1968, but was adjourned at the conclusion

of the second day of testimony when plaintiffs’ counsel

moved to adjourn to permit the school district to submit a

revised plan.

On November 15, 1968, the school district filed its re

vised plan which proposed, in accordance with the pre

vious suggestion by letter of the district court to counsel

for the school district, to reassign its teaching staff for

the 1969-70 school year so that the number of Negro teach

ers within each school in the district would range from

a minimum of 15 per cent to a maximum of 45 per

cent and the number of white teachers within each

school of the district would range from a minimum

of 55 per cent to a maximum of 85 per cent, and

to assign students to school on the basis of compul

sory geographic attendance zones for elementary, junior

high and senior high schools. All students would attend

the school designated for the zone in which they resided,

except that any eligible student in the district could elect

to attend the Metropolitan Vocational-Technical High

School which served all students in the district, teachers

were permitted to enroll their children in the schools

where they were assigned to teach and all students in

the eighth, tenth and eleventh grades were permitted to

choose between the school designated for the zone in

which they resided or the school that such students were

attending at the time of the adoption of the plan.

An evidentiary hearing on the district’s plan began

on December 19, 1968 and after three days of testimony

on December 19, 20 and 24, 1968 was adjourned. Both

plaintiffs and defendants presented expert testimony on

the availability or unavailability to the district of alter

native desegregation plans.

The district court noted that the plan involving com

pulsory geographic attendance zones was based on the

neighborhood school concept by which students are as

signed to attend classes at the school closest their home,

that the only alternative plan to more proportionately

balance student enrollment in the eastern and western

parts of the City of Little Rock would require compulsory

transportation of students by bus for distances of at

least six to eight miles from their homes because of the

heavy predominance of white citizens residing in the

western section of the city and the heavy predominance

of Negro citizens residing in the eastern portion of the

city, that the school district at that time was not furnish

ing transportation to any students and that the annual

cost (exclusive of the initial capital investment which

would be required for needed buses) would be approxi

mately $500,000.00 The school district’s proposals for the

desegregation of both students and faculty were approved.

Thus plaintiffs achieved the basic relief they had earlier

sought in the suit. However, certain modifications were

engrafted upon the student desegregation plan by the

district court. The boundary line of the zone of one of

the district’s five high schools was gerrymandered to

include an additional 80 Negro students in the predom

inately white Hall High School. The consolidation or

pairing of five elementary schools, one of which would

have been attended by 313 Negro students and 34 white

students under the zoning plan, was ordered. This proj

ect, known as the Beta Complex, was a part of a previous

plan which had been considered by the school district.

Finally, the district court superimposed on the zoning

plan a provision which would allow any student in the

district to transfer from a school in which his race was

a majority to a school with available space where his

race was a minority.

2. The decision of the Court of Appeals.

The plaintiffs appealed, urging that the geographic

attendance zone plan based on the neighborhood school

concept failed to achieve a unitary system and that neither

the neighborhood school concept nor the necessity of bus

ing students could excuse the failure, and that the faculty

assignment plan was inadequate to eliminate the racial

identity of certain schools. The school district cross-ap

pealed from those portions of the district court’s order

which gerrymandered the Hall High School attendance

boundary, which required the majority to minority trans

fer option and which ordered implementation of the Beta

Complex. The Court of Appeals en banc1 (two Judges dis

senting) reversed and remanded the district court’s order

insofar as it approved the geographic attendance zone as

signment plan but affirmed as to the faculty desegregation

plan, and as to the three modifications ordered by the dis

trict court. The Court of Appeals based its disapproval

of the student assignment plan on the fact that several

schools in the district remained “ racially identifiable”

because of the heavy predominance of students of one

race and the conclusion that alternative means of pupil

assignment were available to the district to achieve “ more

effective desegregation.”

Chief Judge Van Oosterhout and Judge Gibson dis

sented, finding that “ (E)verything has been done that 1

— 8 -—

1 Judge Mehaffy did not participate. Prior to his appoint

ment to the bench he was a member o f the law firm representing

this school district.

could be done short of abandonment of the neighborhood

system . . that the desegregation process in the dis

trict was no longer impeded by state action; that this

Court had not decided that racial balance was required

in all schools of a metropolitan school district, and that

geographic attendance zones fairly drawn without racial

discrimination should meet the constitutional standards of

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) and

subsequent decisions of this Court.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

This case merits review by this Court on certiorari be

cause it involves issues of vital importance to virtually

all metropolitan school districts in this country which are

now attempting to achieve a unitary school system prior

to the commencement of the 1970-71 school year, pursuant

to this Court’s mandate in Alexander v. Holmes Gounty,

396 U. S. 19 (1969). The absence of definitive guidelines

for meeting the constitutional requirements in such dis

tricts, the square and irreconcilable conflicts on such

issues between and within the various courts of appeal

and the confusion resulting therefrom render the duty of

such districts to establish and operate “unitary school

systems within which no person is to be effectively ex

cluded from any school because of race or color” virtually

incapable of fulfillment. The principal focal point from

which these opinions diverge, and the principal issue

herein, is the constitutional status of student assignment

plans which utilize what is commonly referred to as “ the

neighborhood school concept” by which children are as

signed, on the basis of geographic attendance zones, to

attend the school closest to their home. Because of the

tendency of the people in this country, north, south, east

or west, to reside in those areas of a city populated by

other citizens of their race, such plans almost invariably

— 10

result in an irregular distribution by race of students in

the schools of the district, with some schools having an

all Negro or predominantly Negro enrollment and some

schools having an all white or predominantly white en

rollment, the gradations of minority representation in

particular schools ranging from 0 per cent to 49 per cent.

In Little Rock Negro students comprise approximately 35

per cent of the total student population in the district.

Of the district’s 42 schools, Negro students comprise from

1 to 15 per cent of the enrollment in ten schools, from 15

per cent to 50 per cent of the enrollment in seven schools,

from 50 per cent to 100 per cent in 15 schools, and ten of

the district’s schools have no Negro students enrolled.

Those schools having a high majority of Negro student

enrollment are situated on the city’s east side, those hav

ing a heavy predominance of white students are situated

on the west side and the central city schools are generally

substantially integrated. There is no contention that the

boundaries of any zone were intentionally gerrymandered

by the school district to include or exclude students be

cause of their race. The faculty of every school in the

district has not less than 14 per cent and not more than

50 per cent Negro teachers. As approved by the district

court, the plan would permit any student to elect to trans

fer from a school in which his or her race is in the ma

jority to a school where that race is a minority.

It was recognized by the district court and both opin

ions of the court of appeals that the only alternatives

available to the district to achieve a racial balance in

each school in the district more closely approximating

the racial ratio of Negro and white students in the entire

district involved either tremendously expensive plans

based on an “ educational park” or consolidation and pair

ing concepts or the re-drawing of zone lines in an east-

west direction with the initiation of a cross-busing pro

gram to transport students from one side of the city past

— 11

the central city schools to schools in the opposite side of

the city at an annual expense of $500,000.00.

The effect of the majority opinion below is to deny to

the Little Rock School District the right to assign its pub

lic school students as they are assigned, and have been for

decades, by the vast majority of the nation’s school dis

tricts. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals has noted that

“ The neighborhood school system is rooted deeply in

American culture.” United States v. Jefferson Co. Bd. of

Educ., 372 F. 2d 836, 879 (5 Cir. 1966), aff’d en banc, 380

F. 2d 385 (5 Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U. S. 840 (1967).

In a decision in square conflict with that of the majority

of the Court of Appeals in the case at bar, the Sixth Cir

cuit Court said in Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education,

369 F. 2d 55 (6 Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 389 U. S. 847

(1967), at page 60:

“ The neighborhood system is in wide use throughout

the nation and has been for many years the basis of

school administration. This is so because it is ac

knowledged to have several valuable aspects which

are an aid to education, such as minimization of safety

hazards to children in reaching school, economy of

cost in reducing transportation needs, ease of pupil

placement and administration through the use of neu

tral, easily determined standards, and better home-

school communication. ’ ’

This system of student assignment has received the en

dorsement of all three branches of the fedei’al government

in the very context in which it was attacked in the courts

below. That is, its effects on the allocation of students of

different races among the schools. This Court in Brown

recognized geographic districting as the normal method of

pupil placement and did not foresee changing it as the re

sult of relief to be granted in that case. Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 495 note 13, question 4(a).

The Congress spelled out the national policy pertaining to

12 —

racial considerations in public school assignment in un

ambiguous terms in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the

subchapter dealing with public education it provided:

“ ‘ Desegregation’ means the assignment of students

to public schools and within such schools without re

gard to their race, color’, religion, or national origin,

but ‘ desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of

students to public schools in order to overcome racial

imbalance.” 78 Stat. 246, 42 U. S. C., 2000-c(b)

(1964).2

And, as noted in the dissenting opinion below, President

Nixon in a recent public statement endorsed the neighbor

hood school system and disapproved “ transportation of

pupils beyond normal geographical school zones for the

purpose of achieving racial balance # *

The constitutionality of neighborhood school zoning-

plans has been upheld by many courts of stature although

2 The legislative history establishes beyond doubt that it was

the intention of Congress to adopt, and thus confirm as the na

tional policy, Judge Beamer’s interpretation of the Constitution

in Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind., 213 F. Supp. 819 (N. D.

Ind.), aff’d 324 F. 2d 209 (7 Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 377 U. S.

924. Senator Humphrey, manager of the Bill in the Senate,

made this statement during the debate:

“ Judge Beamer’s opinion in the Gary case is significant

in this connection. In discussing this case, as we did many

times, it was decided to write the thrust of the court’s

opinion into the proposed substitute.” 110 Cong. Rec. 12715.

The “ thrust” of the Gary decision was accurately described

by Senator Humphrey to be:

“ I should like to make one further reference to the Gary

case. This case makes it quite clear that while the Con

stitution prohibits segregation, it does not require integra

tion. The busing of children to achieve racial balance

would be an act to effect the integration of schools. In

fact, if the bill were to compel it, it would be a violation,

because it would be handling the matter on the basis of

race and we would be transporting children because o f race

The bill does not attempt to integrate the schools, but it

does attempt to eliminate segregation in the school systems ”

110 Cong. Rec. 12717.

13

residential patterns produce racial imbalance in some of

the schools. In addition to the decision of the Sixth Circuit

Court in Deal, supra, and that of the Seventh Circuit Court

in Gary, supra, see Springfield School Committee v. Barks

dale, 348 F. 2d 261 (1 Cir. 1965); Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 369 F. 2d 29 (4 Cir. 1966); Brous

sard v. Houston Ind. S. Dist,, 395 F. 2d 817 (5 Cir. 1968),

petition for rehearing en banc denied, 403 F. 2d 34 (5 Cir.

1968) ; Downs v. Board of Ed. of Kansas City, 336 F. 2d

988 (10 Cir. 1964).

However, other decisions, notably in the Fifth Circuit,

have invalidated geographic zoning plans where some

measure of racial balance was not achieved in the enroll

ment of students at schools in the district. See, e. g.,

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

Dist., 406 F. 2d 1086 (5 Cir. 1969); Henry v. Clarksdale

Municipal Separate School Dist., 409 F. 2d 682 (5 Cir.

1969) ; United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate

School Dist., 410 F. 2d 626 (5 Cir. 1969).

Far from resolving the areas of controversy, this Court’s

recent decisions in Green v. County School Board, 391 U. S.

430 (1968); Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Edu

cation, 396 IT. S. 19 (1969), and Carter v. West Feliciana

School Board, 396 U. S. 290 (1970), seem to have com

pounded the confusion as to the ultimate goal sought while

accelerating the deadline for its accomplishment. School

boards were not alone in the resulting quandary; many

courts faced with the responsibility of determining com

pliance with the Constitution expressly decried the ab

sence of criteria by which to determine whether or not a

unitary system had been achieved and the “ cryptic” na

ture of this Court’s definition thereof. See, e. g., Bivins

v. Bibb County, . . . F. Supp. . . . (N. I). Ga., January 21,

1970) ; United States v. State of Georgia, . . . F. Supp.

. . . (N. D. Ga., December 17, 1969); Beckett v. School

Board of the City of Norfolk, 308 F. Supp. 1274 (D. C.

— 14 —

Va. 1969); Thornie v. Houston County, . . . F. Supp. . . .

(M. D. Ga., January 21, 1970); Hilson v. Washington

County, . , . F. Supp. . . . (M. D. Ga., January 28, 1970);

Graves v. Board of Education of North Little Rock, 299

F. Supp. 843 (D. C. Ark. 1969); Northcross v. Board of

Education of Memphis, 420 F. 2d 546 (6 Cir. 1970).

This dilemma was apparently recognized by Chief Jus

tice Burger in his concurring opinion in Northcross v.

Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 397 U. S. 232

(1970), where he observed:

“ . . . the time has come to clear up what seems to

be a confusion, genuine or simulated, concerning this

Court’s prior mandates.

# # #

. . we ought to resolve some of the basic practical

problems when they are appropriately presented in

cluding whether, as a constitutional matter, any par

ticular racial balance must be achieved in the schools;

to what extent school districts and zones may or

must be altered as a constitutional matter; to what

extent transportation may or must be provided to

achieve the ends sought by prior holdings of the

Court. Other related issues may emerge.”

That such conflicts presently exist is best illustrated by

a comparison of the varying views asserted in opinions

rendered within the last five months in courts of appeals

for the Fourth and Fifth Circuits and those of the ma

jority and dissenting opinions of the Eighth Circuit Court

of Appeals herein.

One panel of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit unanimously concluded that a residential zoning sys

tem in which each student was “ assigned to attend the

school nearest his or her home, limited only by the ca

pacity of the school, and then to the next nearest school”

satisfied constitutional requirements. Ellis v. The Board

of Public Instruction of Orange County, Florida, 423 F.

2d 203 (5 Cir. 1970). Less than three months later, an

other panel of that court concluded, also unanimously,

that a similar residential zoning system did not meet con

stitutional demands, and ordered that a majority to mi

nority transfer right be adopted, that transportation be

provided transferring students, and that they be given

priority for assignment to any schools they choose. Single-

ton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School System, . . . F.

2d . . . (5 Cir., May 5, 1970).

On the other hand, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit, sitting en banc in Swann v. Charlotte-Meeklen-

burg Board of Education, . . . F. 2d . . . (4 Cir., May 26,

1970), cert, granted No. 1713, 38 LW 3522 (June 29, 1970),

divided three ways in its efforts to define what the Con

stitution requires of a metropolitan school district. Three

judges were of the opinion that the obligation of such dis

tricts is to “ use all reasonable means” to integrate all

the schools, that a plan was not constitutionally deficient

if such reasonable efforts failed to integrate all the

schools, and that the amount of busing ordered by the

district court to achieve racial balance in the elementary

schools was unreasonable. Two judges thought that the

district court was correct in setting as a goal the system-

wide ratio of Negro and white students, and then re

quiring sufficient busing of students to produce approxi

mately that racial balance in each school. The third view,

expressed by Judge Bryan, is that the district court erred

in entering an injunction requiring the school authorities

to transport students because “ Busing to prevent racial

imbalance is not as yet a Constitutional obligation.”

It has already been noted herein that the Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in its decision in this case

published May 13, 1970, divided five to two on the ques

tion of whether fairly drawn attendance zones for the

assignment of students satisfied constitutional require

— 16 —

ments. The state of the law in this area—the legal stand

ards by which local school authorities must attempt to

guide and measure their official conduct—is succinctly

summarized in the dissenting* opinion below:

“ The District Courts and the Courts of Appeals are

divided upon the constitutional validity of retaining

geographical school zones fairly drawn without dis

crimination. Such issue can only be authoritatively

answered by the Supreme Court.”

The issues presented in Questions Presented Nos. 2

through 5 are subsidiary to the fundamental issue con

tained in Question Presented No. 1. However, they are

necessary to preserve for consideration by this Court the

consistent position maintained by petitioners in both

courts below. That is, that the original command of

Brown that public school systems must operate free from

racial classifications has not been altered by this Court’s

subsequent decisions in the matter. This was confirmed

as recently as Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Ed

ucation, 396 U. S. 19 (1969), in which this Court said it

was the constitutional duty of every school district to

operate “ school systems within which no person is to be

effectively excluded from any school because of race or

color.”

Each of the devices superimposed upon the petitioners’

admittedly fairly drawn zoning system by the district

court, the subjects of Question Presented Nos. 3, 4, and

5, define the rights of the students affected on a purely

racial basis. If Alexander means what it says, each of

these devices by which students are excluded from certain

schools solely because of their race must be invalidated.

In the narrow context of the plight of the Little Rock

School District that prompts the filing of this petition,

this case has been remanded by the Court of Appeals with

no standards by which the Board, or the district court,

— 17 —

can measure its legal obligations pertaining to school

operations during the next school year which commences

September 8, 1970. The dissent below noted that the

Board is “ at a loss to know what course to take in de

vising a desegregation plan” and that the remand in

these circumstances can “ only create confusion and lack

of stability in the Little Rock school system.”

However, the circumstance that makes this case an ap

propriate one for the earliest possible consideration of

this Court is that metropolitan school districts all over

the nation are in a like dilemma. The fundamental issue

tried in this case, on a record meticulously made by both

sides, was the validity of the neighborhood school concept

of student assignment. Educational experts testified for

both sides, and the district court squarely decided this is

sue in a well reasoned opinion. It is therefore submitted

that this case is a particularly suitable vehicle for this

Court to resolve this question of urgent national im

portance.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is submitted that the peti

tion for certiorari should be granted to review the judg

ment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit.

Respectfully submitted

IIERSCHEL H. FRIDAY

ROBERT V. LIGHT

G. ROSS SMITH

1100 Boyle Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Attorneys for Petitioners

July 15, 1970.

APPENDIX.

A -l —

APPENDIX A

United States Court of Appeals

For the Eighth Circuit

No. 19,795.

Delores Clark, et ah,

Appellants,

v.

The Board of Education of the

Little Bock School District, et al.,

Appellees.

No. 19,810.

Appeals from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Eastern District of

Arkansas,

Delores Clark, et al.,

Appellees,

v .

The Board of Education of the

Little Bock School District, et al.,

Appellants. -

Opinion

[May 13, 1970.]

Before Van Oosterhout, Chief Judge; Matthes, Black-

mun, Gibson, Lay, Heaney and Bright, Circuit Judges,

En Banc.*

* Judge Mehaffy took no part in the consideration or decision

of these appeals.

■— A-2 —

Matthes, Circuit Judge.

This appeal and cross-appeal from the judgment of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas (the late and lamented Gordon E. Young) causes

us again to consider whether the efforts of the Board of

Education of the Little Eock, Arkansas, School District

(hereinafter referred to as District or Board) to desegre

gate its schools satisfy the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment as interpreted in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. $. 483 (1954) (Brown I) and subse

quent decisions of the Supreme Court which have deline

ated the principles enunciated therein.

The process of desegregation in this District has been

controversial and its long history is recorded in the deci

sions cited in the margin.1 While we focus our attention

on the events from 1966 to the present, it is necessary to

briefly sketch the background against which these events

are set. Up until 1954 and Brown 1, the District, pursuant

to state law, operated separate educational facilities for

black and white children. After much turmoil, and the

passage of several years, students were assigned to schools

according to the dictates of the Arkansas pupil placement

statute. When this practice was found to contravene the

Fourteenth Amendment,1 2 a “ freedom of choice” plan was

1 Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E. D. Ark. 1956), aff’d

243 F. 2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957) ; Aaron v. Cooper, 2 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 934-36, 938-41 (E. D. Ark. 1957), aff’d Thomason v. Cooper,

254 F. 2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958) ; Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp.

220 (E. D. Ark. 1957), aff’d sub nom. Paubus v. United States,

254 F. 2d 797 (8th Cir. 1958) ; Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp. 13

(E. D. Ark.) rev’d 257 F. 2d 33 (8th Cir.), aff’d sub nom. Cooper

v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ; Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 (8th

Cir. 1958) ; Aaron v. Cooper, 169 F. Supp. 325 (E. D. Ark. 1959) ;

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark. 1959), aff’d sub

nom. Paubus v. Aaron, 361 U. S. 197 (1959); Aaron v. Tucker,

186 F. Supp. 913 (E. D. Ark. 1960) rev’d Norwood v. Tucker,

287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961); Clark v. Board of Education of

Little Rock, 369 F. 2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966).

2 Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 ( 8th Cir. 1961).

adopted. In Clark v. Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 661

(1966), we sanctioned “ freedom of choice” in principle

but found the District’s plan to be deficient in failing to

provide adequate notice to the students and their parents

and to provide a definite plan of staff desegregation. We

remanded and directed the district court to retain juris

diction to insure adoption and operation of a constitutional

plan for the full desegregation of the Little Rock schools.

In August of 1966, four months prior to our decision in

Clark, the Board apparently recognizing the inadequacy

of its existing mode of desegregation, employed a team of

experts from the University of Oregon to make a study

of the system and prepare a master plan of desegregation.

The team submitted its recommendations, the “ Oregon

Report,” in early 1967. In brief, the recommendations

called for abandonment of the neighborhood school con

cept and the development of an educational park system3

through the institution of a capital building program and

the pairing of schools. The cost of implementing the

Oregon plan was estimated to be in excess of ten million

dollars. In the November 1967 school board election at

least one of the incumbent members of the Board who

supported the “ Oregon Report” was defeated and re

placed by a candidate who opposed the report. The election

results were interpreted as a public rejection of the “ Ore

gon Report,” and it was subsequently abandoned by the

Board.

Still searching for a solution, the Board directed Floyd

W. Parsons, Superintendent of Schools, and his staff to

3 The educational park concept, as applied to the Little Rock

District, called for a single attendance zone coextensive with the

school district boundaries. One high school was to be established

drawing students from the entire District. Similarly, fewer middle

schools and elementary schools would be operated, and those oper

ated would be concentrated near the center of the District. Some

pairing was contemplated at the elementary level. Obviously, im

plementation of such a plan would necessitate transportation of

some students from their homes to the schools.

A-4 —

prepare a comprehensive plan for desegregation of the

schools. Acting accordingly, this group submitted a pro

posal known as the “ Parsons Plan.” The plan provided

for desegregation of the high schools and two groups of

grade schools. It made no provision for the junior high

schools. The high schools were to be desegregated by

“ strip-zoning” the District geographically, generally from

east to west so as to form three attendance zones for the

high school students. The Horace Mann High School, an

all Negro school, was to be abolished and utilized as an

elementary facility, and additions were to be made to two

of the three remaining high schools. The two groups of

elementary schools were to be desegregated by pairing of

schools within each group.4 5

The cost of implementing the “ Parsons Plan” was esti

mated at five million dollars,3 and a bond issue for that

amount was submitted to the voters in March of 1968.

Despite active campaigning by Superintendent Parsons

and several Board members, the bond issue was decisively

defeated, as were two incumbent members of the Board

who supported the plan. Thus, as of March, 1968, the

District, although recognizing the inadequacies of the ex

isting means of desegregation, had been unable to develop

and implement an acceptable alternative. And, students

were assigned for the 1968-69 school year according to

* ‘ f reedom-of-choice. ’ ’

4 The “ Parsons Plan” called for the creation of two floating

zones— the Alpha Complex in the northeastern corner of the Dis

trict and the Beta Complex in the south central portion of the Dis

trict. Within these two complexes there existed a number of ele

mentary schools, some of which were predominantly black and

others predominantly white. Under Mr. Parsons’ plan these ele

mentary schools would be paired in order to achieve a “ reasonable

racial _ ratio” in each of the schools. Some remodeling of existing

facilities was contemplated in implementing the two complexes.

5 However, less than 40% o f this sum was directly related to

achieving desegregation. The remaining 60% o f the cost arose from

needs of the system apart from efforts to desegregate.

-~A~5

On June 25, 1968, plaintiffs moved the district court for

further relief.6 The court responded by setting a hearing

for August 15, 1968, and, by letter of July 18, 1968, sug

gested to the Board that it devise a geographic zoning

plan to correct student segregation. The Board was also

admonished to devise a plan for faculty desegregation so

that the racial division of the faculty in each school would

approximate the racial breakdown of the faculty in the

entire District. At the August 15th hearing the District

presented an “ interim” zoning plan which was admittedly

incomplete and required more study, and requested that

the “ freedom of choice” method of pupil placement be

retained for the 1968-69 school year. After the second day

of testimony, the hearing was recessed to enable the Dis

trict to formulate a final plan for the disestablishment of

racial segregation to become effective at the beginning of

the 1969-70 school year. Before recessing, the court re

affirmed its earlier suggestion concerning faculty desegre

gation and stated unequivocally that “ freedom of choice”

as applied to the Little Rock schools would not satisfy the

constitutional requirements. The Board was directed to

file its plan not later than November 15, 1968.

During the Board’s deliberations two plans were sub

mitted for its consideration and rejected. A group of

Negro citizens offered the “ Walker Plan,” so designated

because John Walker, counsel for plaintiffs, was a moving

force in its formulation. The “ Walker Plan” contem

plated grade restructuring and pairing of schools through

out the District and at all grade levels. Substantial

transportation of students would have been necessary to

implement the plan. The Board also considered and re

jected a proposal offered by two of its members calling

6 Several parties sought to intervene. A group of Negro chil

dren, by their parents, were permitted to intervene as parties plain

tiff. The Little Rock Classroom Teachers Association was also

permitted to intervene.

— A-6 —

for retention of “ freedom of choice” plus the reservation

of space at predominantly white schools for Negro chil

dren desiring to attend them. The Board finally adopted,

with two members dissenting, a plan for pupil assignment

based on geographic attendance zones.

Attached to this opinion is a reduced reproduction of

Defendants’ Exhibit 22 depicting the geographic zones

proposed, and designating the location of elementary,

junior high and high school buildings. The elementary

zones are defined by fine lines and the junior high zones

by broad lines. On the original exhibit the high school

zones are identified by four different colors. Because we

were unable to reproduce the colors, we have highlighted

the high school zone boundaries by a crossed line, and

have appropriately designated the several colors of the

original exhibit, Except for this alteration, the map is

an exact reproduction of the original exhibit.

As illustrated by the map, the Little Rock School Dis

trict is an irregular rectangle running from east to west.

Natural boundaries on the north and south and the com

mercial and industrial nature of the eastern portion have

caused the city to expand toward the west. Generally

speaking the eastern one-half of the District is inhabited

predominantly by Negro citizens and the western one-half

predominantly by white citizens.

At the beginning of the 1969-70 school year there were

24,248 students in the system; 15,027 white and 9,221

Negro. They attended five high schools, seven junior high

schools, and thirty-one elementary schools throughout the

District.

Under the District’s plan, all students were to attend

schools serving their grade level in their zone of residence

except: (1) students attending Metropolitan High School,7

7 Metropolitan High School is a vocational school which serves

the entire District. No segregation exists as to this facility.

— A-7

(2) students in the 8th, 10th and 11th grades in 1969-70,

who were permitted to choose between the school in their

zone and the school they had previously attended8 and (3)

children of teachers in the District, who could attend the

school where their parents were employed. The proposal

for faculty desegregation complied with the suggestion

of Judge Young. It called for the assignment of teachers

so that the percentage of Negro teachers in each school

ranged from a maximum of 45% to a minimum of 15%.

Pursuant to the court’s direction at the conclusion of

the August 16 hearing, the District submitted the plan

now under consideration. On December 19, the hearing

was resumed and additional evidence was introduced. On

May 16, 1969, the district court filed its unreported opin

ion. While approving the District’s plan in principle, the

court amended it by: (1) redrawing the Hall High School

zone to include approximately 80 additional Negro chil

dren; (2) establishing a “ Beta Complex” ;9 (3) providing

for majority to minority transfer of students.10

Both parties have appealed from the district court’s

judgment.

A brief summary of the contentions urged upon us will

suffice. Plaintiffs submit that the geographical zones as

drawn merely serve to perpetuate the previously estab

lished segregated attendance patterns of the students in

the District. Neither the neighborhood school concept nor

8 This departure from geographical attendance zones was an ef

fort to minimize disturbance of the extra-curricular patterns estab

lished by students in these grades.

0 The court adopted in part Mr. Parsons’ concept calling for the

pairing of certain elementary schools within a floating zone. See

note 4 supra.

10 This provision of the court’s modification permitted students

attending schools in which their race was in the majority to trans

fer to schools in which their race was in the minority, subject to

the availability of space in the transferee school.

— A-8 —

the possible necessity of busing, according to plaintiffs,

excuses the District’s failure to achieve a unitary system

devoid of racially identifiable schools. Lastly, they argue

that the faculty assignment approved by the district

court continues to preserve the racial identity of certain

schools.11

Conversely, the District is of the firm conviction that

the plan that it submitted to the district court is consti

tutionally faultless. It reasons that the geographical zones

were drawn without regard to race, and that, as such, the

plan established a unitary system within the constitutional

requirements. It is further asserted that the constitution

does not require transportation of children outside the

area of their residence in order to achieve racial balance

in the schools, and indeed the assignment of pupils ac

cording to race would itself be a violation of the Four

teenth Amendment. According to the District, the neigh

borhood school concept is educationally sound, and, in

view of community attitudes, the only feasible means of

operating the Little Rock system.

On cross-appeal the District objects to the district

court’s departure from the geographical zoning scheme it

submitted. It is argued that the gerrymandering of the

Hall zone to include more Negro students and the ma

jority to minority transfer provision are violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment since they require racial distinc

tions to be made. A similar objection is made to the

“ Beta Complex” .

THE FACULTY

For the 1969-70 school year there were 1053 teachers

employed by the District—29% Negro and 71% white.

Under the plan adopted by the District and approved by 11

11 Plaintiffs also assert that the district court erred in refusing to

allow them attorney fees.

— A-9

the district court, the percentage of Negro teachers in

each of the schools varies from 14% to 50%.12 Plaintiffs

complain that even under the approved plan there is a

general pattern throughout the system whereby schools

with a high proportion of Negro students (“ Negro

schools” ) have a higher percentage of Negro teachers.

They argue that this pattern tends to reinforce the racial

identity of those schools.

Just as schools may be racially identified by the makeup

of their student body, so may they be identified by the

character of their faculty, and school boards are obligated

to correct any previous patterns of discriminatory teacher

assignment. One means of correcting such patterns is to

assign teachers so that the ratio of Negro teachers to

white teachers in each school approximates the ratio for

the District as a whole. United States v. Montgomery

County Board of Education, 395 U. 8. 225 (1969); Yar

brough v. Hulbert— West Memphis School District, 380

F. 2d 962 (8th Cir. 1967). However, the ultimate goal is

the assignment of teachers solely on the basis of educa

tionally significant factors, wherein race in and of itself

is irrelevant.

The plan adopted by the District provides for the non-

discriminatory assignment of teachers and affirmative

steps to correct the existing imbalance. The experts

agreed that the District’s plan was ambitious, and in

fact some doubt was expressed as to whether it could be

carried out. However, to a remarkable degree it has

been implemented, and its implementation has radically

changed the complexion of faculties throughout the dis

trict, Where before Negro teachers were heavily con

centrated in those schools long identified as Negro, they

12 The district court judge, on the basis of projected figures,

thought the percentages would range from 15% to 45%. Because

of resignations, attrition, etc. these figures proved slightly incorrect.

A-10 —

are now distributed throughout the District so that no

school has more than 50% Negro teachers. Indeed, and

particularly at the elementary level, in most of the schools

the percentage of Negro teachers in any particular facility

varies only slightly from the percentage of Negro teach

ers in the District as a whole.

Therefore, we affirm the district court’s approval of the

District’s plan with respect to faculty.13 See Kemp v.

Beasley, . . . F. 2d . . . (8th Cir. 1970) (Kemp 111). The

plan as implemented has corrected and exaggerated racial

imbalance of teachers in the system. Faculty desegrega

tion through teacher assignment is a dynamic process. The

District has committed itself to the non-discriminatory as

signment of teachers and the correction of previous segre

gation, and has for the 1969-70 school year evidenced its.

good faith in fulfilling these commitments. We are con

fident that any remaining vestiges of faculty segregation

will be corrected by the District’s continuing efforts.

STUDENTS

After deliberate consideration, we are driven to the con

clusion that the proposal for student desegregation does

not comport with the recent pronouncements of the Su

preme Court, hence it must be rejected. We hasten to

add, however, that significant progress has been made by

the District. For example, Central High School, the scene

of so much turmoil in 1956, is now desegregated— 1,542

white, 512 Negro. So too are several other previously all

black or all-white schools. However, as we recognized in

13 Compare the order of Judge Johnson in Carr v. Montgomery

County Board of Education, 289 F. Supp. 647 (M . D. Ala. 1968).

In a district where the faculty ratio was 3 to 2, the order required

that in the coming school year only 1 of every 6 members of each

school’s faculty be from the race which was in the minority in

that particular faculty. This was approved in United States v.

Montgomery County Board of Education, 395 U. S. 225 (1969).

A -ll

Kemp III, supra, the finding of some progress does not

end the inquiry whether the particular District has satis

fied its constitutional obligations.

It is, of course, axiomatic that the operation of separate

schools for black and white children under sanction of

state law is violative of the Fourteenth Amendment. As

the Court observed in Brown I, supra, in the field of edu

cation “ separate facilities are inherently unequal.” And in

Brown II, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), school districts which had

previously operated “ separate” schools were ordered to

take the necessary action to eradicate this constitutional

violation. The question now before us is whether the

District has fulfilled its constitutional obligation to convert

what admittedly was a segregated school system to a

“ unitary system in which racial discrimination would be

eliminated root and branch.” Green v. County School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U. S. 430, 438 (1968).

Principal guidance from the Supreme Court as to this

issue is to be found in the trilogy of cases decided in 1968.

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, supra;

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould School District, 391

U. S. 443 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of

City of Jackson, 391 U. S. 450 (1968). Each of the school

districts there involved had adopted “ freedom of choice”

plans (or modifications thereof) for pupil assignment. In

general the ‘ ‘ freedom of choice ’ ’ plans under consideration

had not significantly altered attendance patterns which

had been established by pre-Brown I state segregation

laws. “ Negro schools” continued to be attended by Negro

students and “ white schools” by white students. For ex

ample, in Green 85% of the Negro children continued to

attend the all Negro school. Despite the School Board’s

contention in Green that it had “ fully discharged its obli

gation by adopting a plan by which every student, regard

less of race, may ‘ freely’ choose the school he will attend.”

391 U. S. at 437, the Court found that “ freedom of choice”

— A-12 —

as applied to these three districts did not meet the con

stitutional requirements.

The thrust of all three opinions is that the manner in

which desegregation is to be achieved is subordinate to

the effectiveness of any particular method or methods of

achieving it. The following language is instructive:

4 ‘ The burden on a school board today is to come for

ward with a plan that promises realistically to work,

and promises realistically to work now.

The obligation of the district courts, as it always

has been, is to assess the effectiveness of a proposed

plan in achieving desegregation. There is no universal

answer to complex problems of desegregation; there

is obviously no one plan that will do the job in every

case. The matter must be assessed in light of the cir

cumstances present and the options available in each

instance. It is incumbent upon the school board to

establish that its proposed plan promises meaningful

and immediate progress toward disestablishing state-

imposed segregation. It is incumbent upon the district

court to weigh that claim in light of the facts at hand

and in light of any alternatives which may be shown

as feasible and more promising in their effective

ness . . . .

We do not hold that ‘ freedom of choice’ can have

no place in such a plan. We do not hold that a ‘ free

dom of choice ’ plan might of itself be unconstitutional,

although that argument has been urged upon us.

Eather all we decide today is that in desegregating a

dual system\ a plan utilizing ‘ freedom of choice’ is not

an end in itself.” 391 U. S. at 439-40. (Emphasis in

the second and third paragraphs supplied.)

More recent pronouncements by the Court are consistent

with this pragmatic approach. In Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, 396 U. S. 19 (1969), the Court

ordered the “ immediate” termination of dual school sys-

terns and the operation of “ unitary school systems within

which no person is to be effectively excluded from any

school because of race or color.” Id. at 20. (Emphasis

supplied.)

Review of desegregation decisions from this circuit re

veals that we too have tested proposed plans of desegre

gation by their effectiveness. For instance, ten years ago

we held that the Arkansas pupil placement statute, on its

face a non-discriminatory and educationally rational

means of pupil placement, could not be used to assign stu

dents, if it failed to correct the segregated character of

the system. Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir.

I960).14 In 1969, prior to the Green trilogy, we wTere faced

with a “ freedom of choice” plan. Kemp v. Beasley, 389

F. 2d 178 (8th Cir. 1968) (Kemp II). It too was asserted

to be educationally sound and devoid of racial considera

tions. However, we tested “ freedom of choice” as ap

plied in that particular instance and found it lacking; not

by viewing it in the abstract, but rather by considering

whether it effectively advanced the desegregation process.

Our analysis in Kemp II was, of course, approved by the

Green trilogy.15 And, only very recently wTe again found

“ freedom of choice” to be constitutionally deficient in

Kemp III, supra. Although desegregation had been ac

complished at the high school level by pairing and the

junior high level by “ freedom of choice,” application of

“ freedom of choice” to the elementary grades left 5 of

the 10 schools racially identifiable. We ordered the Dis

trict to take the necessary steps to correct the segregated

character of those 5 elementary schools.

Thus, as of this date, it is not enough that a scheme for

the correction of state sanctioned school segregation is

14 See also, Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961).

15 Indeed Kemp II was cited with approval. 391 U. S. at 440.

---A-14

non-discriminatory on its face and in theory. It must also

prove effective. As the Court observed in Green:

“ In the context of the state imposed pattern of long

standing, the fact that in 1965 the Board opened the

doors of the former ‘white’ school to Negro children

and of the ‘ Negro’ school to white children merely

begins, not ends, our inquiry whether the Board has

taken steps adequate to call for the dismantling of

a well-entrenched dual system.” 391 U. S. at 437.

We believe that geographic attendance zones, just as the

Arkansas pupil placement statutes, “ freedom of choice”

or any other means of pupil assignment must be tested by

this same standard.16 In certain instances geographic zon

ing may be a satisfactory means of desegregation. In

others it alone may be deficient. Always, however, it must

be implemented so as to promote desegregation rather

than to reinforce segregation. See United States v. In-

dianola Municipal Separate School District, 410 F.2d 626

(5th Cir. 1969); Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate

School District, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969); United

States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School District,

406 F. 2d 1086 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 395 U. S. 907 (1969).

When viewed in context of the above principles, the plan

approved by the district court is constitutionally infirm.

16 The Board’s reliance on language in Green for the proposition

that geographic zoning in and of itself is constitutionally mandated

is misplaced. In two places in the Green opinion the Court did

refer to geographic zoning as a possible alternative to “ freedom of

choice.” However, it is clear when considered in context, that the

Court was limiting its suggestion to the Kent district, a district

without residential segregation. Indeed footnote 6 quotes with ap

proval a paragraph from the concurring opinion in Bowman v.

County School Board, 382 F. 2d 326 (4th Cir. 1967), in which it

is stated, " . . . a geographical formula is not universally appro

priate.” Id. at 332. Any other reading of the Green decision would

be entirely inconsistent with the Court’s declaration that the ulti

mate test is effectiveness and many plans may or may not prove

effective in a particular instance. See also the footnote appearing'

at 391 U. S. 460. F s

— A -15 —•

For a substantial number of Negro children in the Dis

trict, the assignment method merely serves to perpetuate

the attendance patterns which existed under state man

dated segregation, the pupil placement statute, and “ free

dom of choice” 17—all of which were declared unconstitu

tional as applied to the District. In short the geographical

zones as drawn tend to perpetuate rather than eliminate

segregation.18 Several examples are illustrative. During

the 1968-69 school year, under “ freedom of choice” Mann

High School, located in the eastern portion of Little Rock

and historically an all Negro school, was attended by all

Negroes. In this school year it is attended by 838 Negroes

and 4 whites. Parkview High and Hall High, historically

white schools,19 have 45 Negro and 793 white and 40 Negro

and 1,415 white students, respectively. Prior to this year

both Booker Junior High20 and Dunbar Junior High21

were all Negro. Now they are attended by 733 Negro and

20 white and 685 Negro and 18 white students, respec

tively. Two junior high schools located in the western por

tion of the city are attended by similar proportions of

students with white students predominating. At the ele

mentary level, Carver, Gillam, Granite Mountain, Ish,

Pfeifer, Rightsell, Stephens, and Washington all have 95%

17 Under “ freedom o f choice” in 1968-69 approximately 75% of

the Negro students attended schools in which their race constituted

90% or more of the student body. The plan adopted by the dis

trict court reduces this percentage by only 6%.

1S It was agreed by all the experts that zone lines for the Dis

trict would have to be drawn from east to west if previously es

tablished attendance patterns were to be broken.

19 Both of these schools were constructed after 1956.

20 This school, named after a prominent Negro, was constructed

in 1963. Only Negro children were assigned to it and it was staffed

by Negro teachers.

21 Prior to 1954, Dunbar was the Negro junior high school for

the District.

— A-16 —

or more Negro students.22 In a number of other elemen

tary schools the reverse is true. All of the foregoing

schools are racially identifiable.

While it is true that the majority to minority transfer

provision has the potential for alleviating the situation to

an extent, it is in large part an illusory remedy. No trans

portation is provided for those children choosing to take

advantage of it. And, it requires little insight to recognize

that the children who are most likely to desire transfer

are those least able to afford their own transportation.

Moreover, there is no assurance that space will be avail

able in the schools to which most of the transfers would

probably occur.23

Alternative means of pupil assignment which would pro

vide more effective desegregation were and are available

to the District. Indeed, several such means were embodied

in plans submitted to and considered by the Board. We

point this out not as an endorsement of any particular

plan, but merely to emphasize that alternatives are avail

able. Of particular significance is the “ Parsons Plan,”

which was developed by a group of educators closely af

filiated with the District and presumably quite sensitive

to the educational needs and problems of the community.

It was long ranged and comprehensive. If implemented, it

would have cured the isolation of Mann High School as a

Negro facility. The “ Parsons Plan” also would have

22 Carver, Granite Mountain, Pfeifer, and Washington were

operated as “ Negro schools” under state-imposed segregation.

Rightsell was converted to a “ Negro school” in 1961. Gillam and

Ish, named after prominent Negroes and located in Negro neigh

borhoods, were constructed in 1963 and 1965, respectively. They

were staffed by Negroes and have always been attended almost

solely by Negro students.

23 Compare the transfer provision adopted in Ellis v. Board of

Public Instruction of Orange County, . . . F. 2d . . . (5th Cir. Feb.

17, 1970), which provided transportation for children choosing to

transfer and insured that space would be available in the trans

feree schools.

— A-17 —•

erased the racial identity of several elementary schools

which exists under the plan now before us. It enjoyed the

support of the Board and the professional staff of the

system.

Because of community opposition to the plan, as mani

fested in the defeat of a millage increase necessary to

finance its implementation, the “ Parsons Plan” was not

adopted. Similarly, community opposition was a substan

tial factor in rejection of other promising plans. We are

not unmindful of the difficult nature of the Board’s duties

in this District.24 However, it has long been the law of the

land that community opposition to the process of desegre

gation cannot serve to prevent vindication of constitutional

rights. Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of

Jackson, supra; Aaron v. Cooper; 358 IT. S. 1 (1958); Jack-

son v. Marvell School District No. 22, 416 F.2d 380 (8th

Cir. 1969). Accordingly, we are not at this time prepared

to hold that the geographical zoning plan adopted by the

lower court is the only “ feasible” means of assigning

pupils to facilities in the Little Rock School System.

Green v. County Board of Education of New Kent County,

391 U. S. at 439.

CROSS-APPEAL

By way of cross-appeal defendants challenge those pro

visions of the district court’s order departing from the

geographical zoning plan submitted by the Board. Since

we have found the plan adopted by the district court to be

deficient in the aforementioned particulars thereby requir

ing remand for adoption of an entirely new7 plan, defend

ants’ objections become somewhat academic. Nevertheless,

we briefly address ourselves to the contention that any

consideration of race in the placement of pupils is a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

24 Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33, 39 (1958).

— A-18

This argument is not new and has been previously heard

and rejected by this court, iKemp II, 389 F. 2d at 187-88.

See also United States v. Jefferson County Board of Edu

cation, 372 F. 2d 836, 876-78 (5th Cir. 1966); Wanner v.

County School Board, 357 F. 2d 452, 454-55 (4th Cir. 1966);

Fiss, Racial Imbalance in the Public Schools: The Con

stitutional Concepts, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 564, 577-78 (1965).

As the Wanner court observed it would be somewhat

anomolous to prevent correction of previous segregation

under the guise that the remedy impermissibly classifies

by race. Accordingly, we are not persuaded by defendants’

contention that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the

drawing of geographic zones to promote desegregation,

the majority to minority transfer plan, or any other con

sideration of race for the purpose of correcting uncon

stitutionally imposed segregated education.

REMEDY

This court has long recognized that it should not en

deavor to devise a plan of desegregation for any school

district. Kemp III, supra; Yarbrough v. Hulbert—West

Memphis School District, supra; Clark v. Board of Educa

tion of Little Rock, supra; Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14

(8th Cir. 1965); Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33 (8th Cir.

1958). This task is basically within the province of the

school board under the supervision of the district court.

We continue to adhere to this philosophy. In light of the

size and complexity of the Little Rock School District it

is additionally important that the Board be afforded ample

opportunity to formulate a comprehensive plan of de

segregation. Nor do we believe it proper to direct the

Board to adopt a particular means of school desegrega

tion. As was observed in Green v. County Board of Educa

tion of New Kent County, supra, there are a variety of

methods of desegregation, and no particular method is

A-19 —

universally appropriate. Considering the unique problems

facing the District any one of several different methods,

or a combination thereof, may be deemed appropriate.

We leave this decision to the school board and the sound

discretion of the district court. We do, however, strongly

suggest that the Board consider enlisting the services of

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare in de

veloping an acceptable scheme of desegregation.

Consistent with these above views we consider several

questions either implicitly or explicitly raised in the

parties’ briefs and oral arguments.

As in Kemp 111, supra, we do not hold that precise

racial balance must be achieved in each of the several

schools in the District in order for there to be a “ unitary

system” within the meaning of the constitution. Nor do

we hold that geographical zoning or the neighborhood

school concept are in and of themselves either constitu

tionally required or forbidden. See Kemp 111. We merely

hold that as employed in the plan now before us they do

not satisfy the constitutional obligations of the District.

By so holding we express no opinion as to the relative

merits or demerits of the neighborhood school.

Lastly, we do not rule that busing is either required or

forbidden. As Judge Blackmun stated in Kemp 111, “ Bus

ing is only one possible tool in the implementation of uni