Johnson v. City of Albany Plaintiffs' Proposals for the Handling of Back Pay

Public Court Documents

June 10, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson v. City of Albany Plaintiffs' Proposals for the Handling of Back Pay, 1976. 637c380e-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/281d8ec5-7bde-463d-b258-4827eb1c2bae/johnson-v-city-of-albany-plaintiffs-proposals-for-the-handling-of-back-pay. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

n O

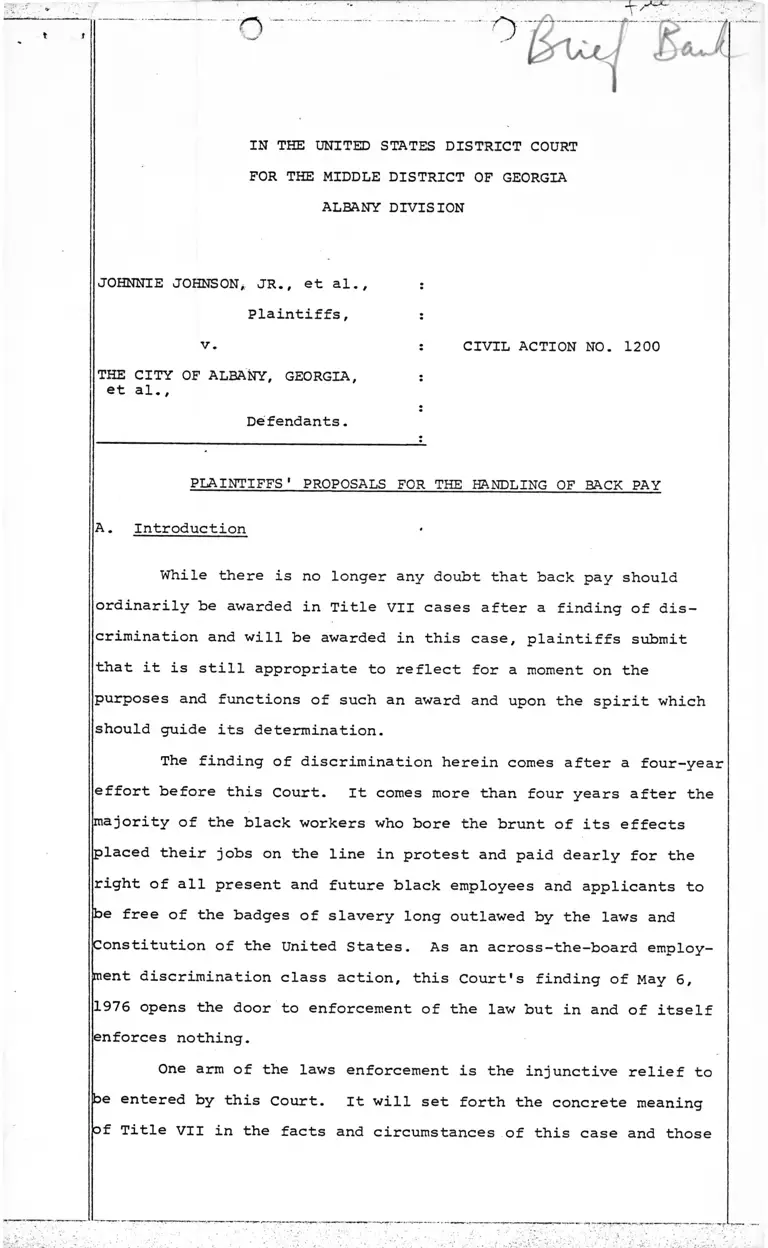

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ALBANY DIVISION

JOHNNIE JOHNSON* JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs

v CIVIL ACTION NO. 1200

THE CITY OF ALBANY, GEORGIA

et al. ,

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSALS FOR THE HANDLING OF BACK PAY

A . Introduction

While there is no longer any doubt that back pay should

ordinarily be awarded in Title VII cases after a finding of dis

crimination and will be awarded in this case, plaintiffs submit

that it is still appropriate to reflect for a moment on the

purposes and functions of such an award and upon the spirit which

should guide its determination.

The finding of discrimination herein comes after a four-year

effort before this Court. It comes more than four years after the

majority of the black workers who bore the brunt of its effects

placed their jobs on the line in protest and paid dearly for the

right of all present and future black employees and applicants to

be free of the badges of slavery long outlawed by the laws and

Constitution of the United States. As an across-the-board employ

ment discrimination class action, this Court's finding of May 6,

1976 opens the door to enforcement of the law but in and of itself

enforces nothing.

One arm of the laws enforcement is the injunctive relief to

be entered by this Court. It will set forth the concrete meaning

of Title VII in the facts and circumstances of this case and those

whose lives are touched by it will come away from the experience

with a renewed sense of faith in the nation and in its commitment

to the ideals of equality and justice. For the vast majority of

them this Court’s Decree will make Title VII a reality rather than

an abstract proposition.

The second arm of the laws enforcement is the monetary

relief to be awarded. For many people this Court's Decree will

come too late to have any effect of their lives. Some class mem

bers have worked for the defendants for years in low paying jobs

until their retirement. Some engaged in the strike of April 19,

1972 and were never rehired. Finally, there are some who once

endured the humiliation and degradation of segregation and low pay,

quit in frustration and went on to employment elsewhere. For each

of these persons the Decree will provide no relief. For each class

member, only this Court's award of back pay and the manner in which

it makes that award will enable them to derive any benefit from

the enactment of Title VII or from plaintiffs' laborious effort to

enforce it in Municipal employment. The Fifth Circuit once

described the meaning of the promise of Title VII in terms truer

than any traditional phrasing could have: "Beneath the legal

facade a faint hope is discernible, arising like a distant star

1/over a swamp of uncertainty and perhaps of despair." The people

described in this paragraph are entitled to taste the reality of

that hope as fully as the defendants' present and future employees.t

B. The Legal Context of Plaintiffs' Back Pay Proposals

Plaintiffs' proposals for the handling of back pay in this

case are set forth beginning at page 16. Before developing them,

plaintiffs examined the leading appellate decisions on the manner

handling class back pay claims, with chief reference to the

Fourth and Fifth Circuits.

M Miller v. International Paper Co.. 408 F.2d 283, 294 (5th Cir.

1969K -----

O ........... ... ' ' J ' ---------

- 2-

- - r v - ...... -... — -w

The most striking features of these decisions are the

strength of the courts' insistence that some effective way be

found to compensate the members of a class which has been shown

to have been discriminated against in the liability phase of the

trial, and the variety of ways in which the courts have shifted

the burden of proof with respect to the back pay claims of indi

vidual class members to the employer found to have discriminated.

The decisions, most of which have been entered in the last two

years, seem to establish seven broad principles, and they are:

1. Classwide Back Pay Cannot Be Denied On The

Ground That It Is Speculative.

In Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364,

1380 (5th Cir. 1974) and Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F.2d 211, 259 (5th Cir. 1974), the Fifth Circuit held that

back pay could not be denied on the ground that it was speculative.

The Court stated that "unrealistic exactitude is not required" and

that "uncertainties ... should be resolved against the discrimina

ting employer," Pettway, supra, 494 F.2d at 259. The Fifth Cir

cuit has referred to the "quagmire of hypothetical judgments"

caused by the impossibility of "determining which jobs the class

members would have bid on and obtained" absent discrimination,

particularly where there are more class members than vacancies,

but concluded: "It does not follow that back pay claims based on

promotions cannot be awarded," Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe

Co., 404 F.2d 211, 260 (5th Cir. 1974). The Sixth Circuit reached

the same conclusion in Meadows v. Ford Motor Co., 510 F.2d 939

(6th Cir. 1975). There, the District Court had denied back pay to

a class of unhired female applicants because there were more of

them than there were vacancies, and because there was no way to tel

which of them would have been hired absent discrimination. Holding

2/that "The wrongdoer is not entitled to complain" since it had

created the situation that made the ascertainment of relief diffi-

j/ Story Parchment Co. v. Paterson Parchment Paper Co., 282 U.S.

555, 563-64 (1931).

- 3-

cult, the Sixth Circuit reversed.

2. After A Finding Of Discrimination Against The Class,

The "Initial Burden" On A Back Pay Claimant Is Light

After a finding of discrimination against a class, there is

an "initial lighter burden" on a class member or on whoever is

acting on behalf of the class member, "with a heavier weight of

rebuttal on the employer," Pettway, supra, 494 F.2d at 259. The

"initial lighter burden" does not include any requirement that the

class member show he or she would have been hired or promoted

absent discrimination; it is the employer's burden to show "by

clear and convincing evidence" that the class member would not

3/

have been hired or promoted absent discrimination, id. The

Supreme Court recently approved the placing of this burden on the

employer. See Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., __ U.S. __,

47 L.Ed.2d 444, 466 (1976).

The nature of the "initial lighter burden" and the means of

discharging it will vary from case to case depending on the facts

of the case in question. In some cases, as the Fifth Circuit

suggested in United States v. United States Steel Corp.. 520 F.2d

1043, 1054 (5th Cir. 1975), it may be appropriate to discharge it

in a series of individual, claimant-by-claimant trials. In other

cases, as that same case suggests and Part 3 discusses, it may be

appropriate to use a "classwide" or "formula" approach. In

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.. 491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974),

for example, the Fifth Circuit used a group approach and held that

the initial burden would be discharged by evidence showing that a

black was hired into the labor department before Goodyear's aban

donment of a high school diploma requirement for better-paid jobs,

and was "frozen into" that department by Goodyear's testing and

seniority systems. 491 F.2d at 1380.

Of course, the employer has the right to rebut such a prima

facie claim. The burden is not easy to discharge and under the

y Accord, Hairston v. McLean Trucking Co.. 520 F.2d 226 (4th Cir.

L975). ---

- 4 -

facts of this case the defendants would have to prove either that

no vacancies existed at any time during the term of the individual

employees 1 term of employment or that he or she was not qualified

or qualifiable for any job other than the one held.

In many cases, the evidence necessary to discharge the

"initial burden" can easily be obtained from employer records and

the trial record. Where this is true, there is no reason to

require an individual class member to appear and testify unless

the defendants seek to rebut his or her claim and such testimony

is essential to pierce the defendants' rebuttal.

It bears stressing that the form of discrimination herein

will prevent many black employees from knowing very much about

their own claims. The defendants have no valid objective criteria

for determining who should be hired and who should be promoted,

and class members could not ordinarily say that they knew their

"qualifications" were superior to those of whites. Many class

members were simply not permitted to obtain the on-the-job train

ing necessary to become qualified for some high paying jobs and,

therefore, could not say that they are qualified for that job.

However, if given the opportunity, they could become qualified.

Additionally, since job openings occur in several different

departments of the City, some of which blacks have been excluded

from in the past, and information as to job openings was communi

cated by word-of-mouth, many black employees simply would not

know what jobs were available. it seems to follow that a black

class member could not be held accountable for specifying the

vacancies he would have filled absent discrimination. To require

class members to file proof-of-claim forms would in effect impose

"opt-in" requirements. Its only effect would be to unfairly

reduce defendants' liability by immunizing them from the merito

rious claims of people who do not understand the rights that they

may have, do not know the facts adding up to a claim, or do not

- 5-

realize the legal significance of the facts which they do know.

Because of a widespread belief that this was the practical

effect of "opt-in" requirements, the Advisory Committee on the

Civil Rules amended Rule 23(b)(3) in 1966 to repeal the former

requirement that the described persons must "opt-in" to become

class members, and to add a provision that the described persons

would automatically be class members unless they opted out. Then-

5/

Professor Kaplan, the Reporter to the Advisory Committee,

explained the traditional defendant's justification for the old

rule — and one which plaintiffs expect the defendants to proffer

herein:

4/

It was suggested that the judgment in a (b) (3)

class action, instead of covering by its terms

all class members who do not opt out, should

embrace only those individuals who in response

to notice affirmatively signify their desire to

be included .... It is unfair to a defendant

opposing the class, so the argument goes, to

subject him to possible liability toward indi

viduals who remain passive after receiving

notice or who may, indeed, have had no notice

of the proceeding: under the previous law, some,

perhaps many, of those persons might simply have

foregone any claims against the defendant; they

might in fact have remained ignorant of having

any possible claims. Running through this argu

ment was the idea that litigation should be a

matter for the distinct action by each individual.

Continuing Work of the Civil Committee: 1966 Amendments of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (I), 81 Harv. L. Rev. 356, 397

(1967). After criticizing the legal assumptions in that theory,

he went on to explain the reasons for the policy choice made by

the Advisory Committee and adopted by the Supreme Court:

If, now, we consider the class, rather than the

party opposed, we see that requiring the indi

viduals affirmatively to request inclusion in

—/ Such a requirement also immunizes defendants from the claims of

those most in need of the Court's protection: those who are

frightened of legal proceedings and those who are frightened of

retaliation against them if they assert their rights. Whether or

not such fears are realistic is less important than the fact that

they do exist. Counsel is aware of at least some current

employees who could have testified to facts which affected liabil

ity but refused to come forward at the time of trial for fear of

retaliation.

5/ He is presently a Justice of the Mass. Supreme Judicial Court.

- 6-

the lawsuit would result in freezing out the

claims of people — especially small claims

held by small people — who for one reason or

another, ignorance, timidity, unfamiliarity

with business or legal matters, will simply

not take the affirmative step. The moral

justification for treating such people as null

quantities is questionable. For them the class

action serves something like the function of an

administrative proceeding where scattered indi

vidual interests are represented by the Govern

ment. In the circumstances delineated in sub

division (b)(3), it seems fair for the silent

to be considered as part of the class. Other

wise the (b)(3) type would become a class action

which was not that at all — a prime point of

discontent with the spurious action from which

the Advisory Committee started its review of

Rule 23.

81 Harv. L. Rev. at 397-98. See also Note of the Advisory Com

mittee on the Civil Rules. 34 F.R.D. 325, 387-88. Accord, Clark

v. Universal Builders. 501 F.2d 324, 340 (7th Cir. 1974).

Apart from the legality of the procedure, it is apparent

that its actual effect may vary widely in different kinds of

cases. In English v. Seaboard Coast Line r .r . Co ., 12 F.E.P.

cases 90 (S.D. Ga. 1975) where an experimental proof-of-claim

procedure was used, there were less than 250 employees (approxi

mately 110 blacks) at the facility and there were only 29 tradi-

tionally-white job categories at issue as of the date of trial.

Here, the defendants have over 1,000 employees and over a hundred

job categories. Given the high rate of turnover, defendants may

well have employed several thousand persons during the six-year

period covered by this litigation. In English, there were unions

and well-established seniority systems throughout the period

covered by the litigation, and the class members presumably knew

about vacancies as they came open and could now identify specific

6/vacancies on their claim forms. Here, however, the jobs are not

well defined and there was no mechanism by which employees knew

17" New York counsel in this case succeeded Morris J. Bailer as co

counsel in the English/Hayes litigation. While it does not appear

in any of the published opinions in that case, Seaboard Coast Line

had a practice (called "dead-ending") of permitting all its

employees to train on their own time for any job. Thus, the

English/Hayes class members knew not only what jobs were available

but what the requirements of those jobs were.

- 7-

what jobs existed or when vacancies occurred, except perhaps with

in their own department. Even where a class member knew of a

particular vacancy in a higher paying job, he or she may not know

that there was discrimination in filling those jobs. Defendants

have no valid objective criteria for determining who should be

hired and who should be promoted, and class members could not

ordinarily say that they knew their "qualifications" were superior

to those of whites.

Mack v. General Electric Co., 15 F.R. Serv. 2d 799 (E.D.

Pa. 1971) is directly in point. There, the court reversed its

earlier stand and held that the use of proof-of-claim forms was

Vimproper in Title VII cases:

We are not here dealing with sophisticated litigants

such as those in the ordinary antitrust case who are

invariably well counselled. Rather, we are dealing

with a large group of persons who can be assumed to

be generally untutored and unaware of the intrica

cies of the law's demands. I am now convinced that

Paragraph 4 places an unnecessary and difficult

burden upon the members of the class which could well

result in the technical extinguishment of what may

be meritorious claims.

This point is strengthened by the widespread judicial and

Congressional recognition that "[Sophisticated general policies

and practices of discrimination are not susceptible to such pre

cise delineation by a layman who is in no position to carry out

a full-fledged investigation himself." Graniteville Co., Sibley

Div. v. E.E.O.C.. 438 F.2d 32, 38 (4th Cir. 1971). This is why

the courts have not demanded that witnesses to specific acts of

discrimination step forward and have relied heavily on statistics

instead. United States v. Hayes Int'l Corp.. 456 F.2d 112, 120

(5th Cir. 1972); Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.. 457

F.2d 1377, 1382 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied 409 U.S. 982 (1972).

Congress recognized the same reality when it was considering the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. 92-261, 86 Stat.

103:

2/ A copy of this Memorandum is attached.

r - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1

- 8-

During the preparation and presentation of Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, employment

discrimination tended to be viewed as a series

of isolated and distinguishable events, due, for

the most part, to ill-will on the part of some

identifiable individual or organization ....

Employment discrimination, as we know today, is a

far more complex and pervasive phenomenon. Experts

familiar with the subject generally describe the

problem in terms of "systems" and "effects" rather

than simply intentional wrongs. The literature on

the subject is replete with discussions of the

mechanics of seniority and lines of progression,

perpetuation of the present effects of earlier dis

criminatory practices through various institutional

devices, and testing and validation requirements.

The forms and incidents of discrimination which

the Commission is required to treat are increasingly

complex. Particularly to the untrained observer,

their discriminatory nature may not appear obvious

at first glance ....

Report of the House Committee on Education and Labor, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess. (Report No. 92-238, 1971) at 8 (footnote omitted).

In the circumstances of this case, the imposition of a

proof-of-claim requirement as to claims adequately disclosed by

the defendants' records would give them an undeserved windfall and

would unfairly prejudice the rights of class members.

3. The Courts of Appeals Have Suggested Several Means

Of Making Back Pay Determinations On A Formula Basis

The courts of appeals have considered the problem of situa

tions in which it is impossible to prove which class members would

have been hired, or initially assigned or promoted to good paying

jobs, absent discrimination, and have also considered the problem

situations in which it is impossible to prove exactly how much

more money an individual class member would have earned absent

discrimination. Three principles emerge fairly clearly from their

decisions: that back pay must nonetheless be awarded (see Part 1,

supra); that it is preferable to make these determinations on as

individualized a basis as possible (see United States Steel, supra);

and that it is sometimes appropriate to use a "formula" approach

to calculate back pay for the class and to ascertain the amount

of each class member's entitlement.

- 9-

-__W~>

V

The seminal case on the formula approach is Pettway. First,

the court defined the problem:

When a court is faced with the employment situation

like this case, where employees start at entry

level jobs in a department and progress into a

myriad of other positions and departments on the

basis of seniority and ability over an extended period

of time, exact reconstruction of each individual

claimant's work history, as if discrimination had 152/

not occurred, is not only imprecise but impractical.

j-JL?,/ The key is to avoid both granting a windfall

to the class at the employer's expense and the

unfair exclusion of claimants by defining the class

or the determinants of the amount too narrowly.

For instance, in this case, actually to assume that

employee #242 would have been promoted in three

years to such-and-such a job instead of employee #354

is so speculative as to unfairly penalize employee

#3 54 ___

494 F.2d at 261-62. The Fifth Circuit then cited with approval

the formula approaches adopted by several courts. For example,

it stated:

Another method of computation can be categorized as

a formula of comparability of representative employee

earnings formula. Approximations are based on a

group of employees, not injured by the discrimination,

comparable in size, ability, and length of employment

— such as "adjacent persons on the seniority list or

the average job progress of persons with similar

seniority" — to the class of plaintiffs ___

494 F.2d at 262 (footnote omitted). The Fifth Circuit then

quoted with approval a similar formula approach suggested by EEOC

which said that "it has more basis in reality (i.e., actual

advancement of a comparable group not discriminated against) than

an individual-by-individual approach," and explained its operation:

In other words, the total award for the entire class

would be determined. At that point, individual

claims would be calculated on pro rata shares for

those workers of similar ability and seniority claim

ing the same position, possibly eliminating the

necessity of deciding which one of many employees

would have obtained the position but for the discrim

ination. Claimants dissatisfied with their portion

of the award could be allowed to opt out in order to

prove that they were entitled to a larger portion.

Cf. Fed.R.Civ.P. 23(d) (2); Protective Committee v.

Anderson. 390 U.S. 414, 435, n.17, 88 S.Ct. 1157,

20 L .Ed.2d 1 (1968).

494 F.2d at 263 and at 263 note 154.

- 10-

The Fifth Circuit followed Pettway with Baxter v. Savannah

Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974), cert, denied

419 U.S. 1033 (1974). As in the case at bar, personnel decisions

were made subjectively. The Fifth Circuit suggested two possible

approaches for the consideration of the district court. The first

was the comparability formula approach suggested by EEOC in pett-

way, with the court first ascertaining the actual objective

qualifications of white workers, then determining which of those

qualifications "are established by Savannah to be job related,"

and then applying these court-determined standards to black

workers:

The evidence distilled from this process should pro

vide a standard for determining whether an individual

black worker was actually qualified for promotion

under a true merit system.

494 F.2d at 444. Alternatively, if Savannah could establish that

turnover in higher paid jobs was too low for all blacks to have

been promoted:

... then the district court might consider a black

incumbent's accumulated seniority in determining

which black employee would have been promoted from

the available pool.

The next occasion on which the Fifth Circuit confronted the

problem of identifying the class members who would have been pro

moted absent discrimination was in the united States Steel case,

supra. The court suggested the division of the class into several

smaller groups with comparable qualifications and seniority to

ensure the greatest possible individualization. Because of

United States Steel's reliance on seniority systems and lines of

progression, the court thought that it might be possible to flow

chart vacancies which occurred and, separately for each such

smaller group, "award back pay by reconstructing hypothetically

each eligible claimant's work history" based on the court's "sound

judgment" as to which claimants would have occupied vacancies

apart from discrimination. 520 F.2d at 1055. Part of the "key"

to back pay determinations, said the court, is to avoid granting

- 11-

.J

a windfall to the class at the employer's expense, and this

approach would accomplish the objective. Other methods of calcu

lating a class member's individual entitlement by formula are also

proper. In Sabala v. Western Gillette, 516 F.2d 1251 (5th Cir.

1975), the Fifth Circuit affirmed a district court's choice of a

formula:

The trial judge computed back pay awards in the

following manner. First, he selected a reasonably

prudent (i.e., representative) road driver and a

reasonably prudent city driver, each having

characteristics representative of their peers with

respect to seniority, earnings, and work habits.

Next, he compared the average monthly earnings of

these representative drivers for the period June 3,

1968 to July 17, 1973.

The trial court there found that an average road

driver, on a monthly basis, earns 1.56 times the

amount earned by an average city driver. The trial

judge acknowledged that this method of damage cal

culation contains a statistical disparity and does

not measure what the plaintiffs would have earned if

they had been given the first available opportunity

to transfer. The trial court, nonetheless, thought

this formula was the best available method of esti

mating the back pay to be awarded.

The court then computed the discriminatee's earnings

for the period from June 3, 1968 to July 17, 1973,

or from his "rightful place" seniority date to

July 17, 1973, whichever period was the lesser. That

figure was then multiplied by a factor of 1.56,

reduced by 10 percent to account for employment-

related expenses, and further reduced by the amount

of any "interim earnings" that the discriminatee had

been able to earn while working as a city driver,

which he would not have been able to earn if he had

been on the road.

516 F.2d at 1265.

The proposal suggested by plaintiffs seeks first to calculate

individual awards by a comparison of rates of pay. Where the

defendants can demonstrate availability of few vacancies compared

to the number of class members, it may then be appropriate to

adopt a pro rata or averaging formula. See Part 8 below.

4. The Employer, Not The Class Member, Has The Burden

With Respect To "Amounts Earnable With Reasonable

Dilicrence" And With Respect To Any Facts In Mitigation

It is traditional law, in these types of cases, that a class

member does not have the burden of proving reasonable diligence or

- 12-

that there are no facts which would mitigate the class member's

back pay claim. The employer has the burden of proving failure

of reasonable diligence or any other facts in mitigation. Sprogis

v. United Air Lines, 517 F.2d 387 (7th Cir. 1975); Kaplan v.

I.A.T.S.E., F.2d , 11 FEP Cases 873, 879 (9th Cir. 1975);

Sparks v. Griffin, 460 F.2d 433, 443 (5th Cir. 1972); N.L.R.B. v.

Madison Courier, 472 F.2d 1307, 1318 (D.C. Cir. 1973); Hegler v.

Board of Educ. of the Bearden School District, 447 F.2d 1078,

1081 (8th Cir. 1971) ("The overwhelming authority places the

burden on the wrongdoer to produce evidence showing what the

appellant could have earned to mitigate damages.")

5. The Back Pay Award Should Include Prejudgment

Interest, Vacation Pay and Retirement Benefits.

An award of back pay must include more than simply the

amount of the pay differential. In Pettway, the Fifth Circuit

held;

Finally, the ingredients of back pay should include

more than "straight salary." Interest, overtime,

shift differentials, and fringe benefits such as

vacation and sick pay are among the items which

should be included in back pay. Adjustment to the

pension plan for members of the class who retired

during this time should also be considered on

remand.

494 F.2d at 263 (footnote omitted). Accord, Meadows v.■Ford

Motor Co., 510 F.2d at 948; Chastang v. Flynn & Emrich Co., 381

F. Supp. 1348, 1351-52 (D.Md. 1974) and Fourth Circuit cases cited

there; EEOC v. Kallir, Philips, Ross, Inc., 401 F. Supp. 66 (S.D.

N.Y. 1975); Weitkenaut v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 381 F. Supp.

1284, 1289 (D.Vt. 1974).

6. The Defendants Must Pay The Costs Of The Back Pay

Proceedings, Which Plaintiffs Believe To Include

Their Counsel Fees, Regardless Of The Outcome Of

The Proceedings.

In Hairston, the Fourth Circuit stated that time-consuming

back pay determinations were a "classic" situation for reference

to a master, and continued:

And since the necessity of resort to a master

results from the discriminatory employment

practices of McLean and MAS, they should bear

his costs as well.

- 13-

520 F.2d at 233. The additional legal work these proceedings will

require of counsel for plaintiffs also result from the discrimina

tion found by the Court and should also be paid by the defendants

on a current basis. Whether or not plaintiffs ultimately prevail

on all or just some of their claims does not affect their status

as the prevailing parties and thus their entitlement to fees.

See 10 Wright & Miller, Practice and Procedure § 2667 (1973).

7. An Award Of Back Pay Should Continue Until The

Victims Of Discrimination Are In Their Rightful

Place.

The Fourth Circuit recently held that back pay awards should

compensate the victims of discrimination for injury continuing

past the date of judgment, until such time as the individual in

question receives his or her "rightful place." Patterson v.

American Tobacco Co., __ F.2d __, 12 F.E.P. Cases 314, 323, 11

EPD 5 10,728 (4th Cir. 1976).

The Fifth Circuit had stated in Pettway that the termination

date for back pay should be the date of the decree for most claim

ants and earlier for some others, 494 F.2d at 258, but appears to

have left discretion for further monetary relief. In Sabala,

the Court of Appeals refused to reverse a similar limitation as

an abuse of discretion, but suggested that the district court on

remand "may, if necessary, reconsider the back pay relief granted

in light of the company's ability to find jobs for the discrimina-

tees." 516 F.2d at 1266. In United States v. United States Steel

Corp., 371 F. Supp. 1045, 1069, note 38 (N.D. Ala. 1973), the

district court ordered "forward pay" for the three subclasses for

which it awarded back pay. The company did not appeal so the

Fifth Circuit was not confronted with the question.

In any event, an award of front pay would seem to be

required by the principles of Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 405 (1975). It cannot be denied that it will take time

(

before any Decree the Court can enter herein will wipe out every

continuing effect of prior discrimination. Until enough vacancies

-14-

occur in high paying jobs, black will continue to earn substan

tially less than whites. This is an ongoing economic loss arising

from prior discrimination, and compensation for it should be

denied only for compelling reasons. Albemarle Paper held that

one of the "central statutory purposes" of Title VII was to "make

whole" the victims of discrimination, and that monetary relief

for economic injury should be denied only for reasons which, if

applied generally, would not frustrate this purpose. A denial of

forward pay herein would violate this standard.

8. If It Becomes Necessary To Consider Vacancies, All

Vacancies Occurring On Or After July 2, 1965 Should

Be Considered.

Considering the high turnover rate occurring among employees

of the defendants, it should not be necessary to consider vacan

cies in determining the back pay claims of the members of the

class. Before engaging an any vacancy analysis, the defendants

should be required to affirmatively demonstrate that the lack

of vacancies in particular departments will have a significant

effect on the amount of individual awards.

Assuming that defendants can demonstrate a lack of vacancies r

this Court should consider vacancies occurring on or after July 2,

1965 for the following reasons. Under the Fourteenth Amendment,

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983, it has long been unlawful to discrimi

nate in employment on the basis of race. See Guerra v. Manchester

Terminal, 498 F.2d 641 (1974). Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 has been in effect since July 2, 1965. The original Act

was intended to have prospective application only. In 1972 Title

VII was amended and made applicable to public employers. The

8/

amendments were given retroactive effect. See Brown v . GSA, ___

U.S. ___, 44 U.S.L.W. 4704, 4705 (June 1, 1976); Palmer v. Rogers,

__ F. Supp. , 10 EPD 5 10,265 (D.D.C. 1975). Thus, under all of

W For this reason, the back pay period in this case should run

against the City of Albany from two years prior to April 24, 1972,

the date of filing of charges of unlawful discrimination with the

EEOC. See Part D, infra.

■ ■ & ' J

- 15-

the laws that are the bases of this suit, the filling of vacancies

since July 2, 1965 which have the effect of unlawfully discrimina

ting on the basis of race must be considered in calculating back

pay. Obviously plaintiffs and the members of the class have

suffered from the effects of unlawful discrimination and have

lost wages as a result prior to April 24, 1970 but claims for

wages lost prior to that time are barred because of the two-year

statute of limitations that apply here. See Johnson, supra, 491

F.2d at 1378. However, the filling of vacancies which existed

prior to that date have effects which were perpetuated into the

9/perxod not time-barred.

Accordingly, if a vacancy analysis is used for jobs in

certain departments, the defense of lack of vacancy would be

available only if none existed after July 2, 1965 or since the

time of initial hire, whichever is later.

C . Plaintiffs' Proposals

Plaintiffs suggest that this Court adopt a procedure for

determining the amount of individual claims which will limit the

number of individual hearings required to be held to those essen

tial to establish necessary facts.

For each person employed during the limitations period,

defendants should be required to prepare lists showing the name,

Social Security number, race, sex, years of education, date of

hire, application, date of termination, department and job code,

each job change (including department, job and step code), and

the date thereof and rates of pay. This information should be

10/

keypunched or keytaped by the defendants and plaintiffs provided

9/ Defendants may argue that the statute of limitations also bars

consideration of vacancies occurring prior to April 24, 1970.

Plaintiffs note that in addition to the argument made above as to

present effects of past discrimination those vacancies must be

considered under the 20-year limitations period provided for under

Georgia law. Ga. Code § 3-704. See Franks v. Bowman Transporta

tion Co.. 495 F.2d 398, 405 (5th Cir. 1974).

10/ Most, if not all, of the data suggested for inclusion on this

list apparently is already possessed by the defendants in computer

readable form.

- 16-

with the data processing cards or tapes containing this informa

tion.

For each such higher paid job category, the defendants

should prepare three lists each of which should be subject to

verification by plaintiffs. The first list would include the

name, Social Security number, and dates of incumbency of each

white who was employed in that job category within the period of

limitations, and the "qualifications possessed by white workers

u /which are ... job related" should be listed. The second list

would contain the names and dates of employment of each class

member whom the defendants concede to have had those qualifica

tions and the earliest date, following his actual seniority date,

by which the defendants concede that the class member was so

qualified. The third list would contain the names of all class

members whom they contend, based on a search of their records and

the knowledge of their officials, do not possess the above-

12/

described qualifications. In each case, the defendants should

state in detail the valid job-related reasons why the person is

listed as unqualified. Pettway clearly approves such an approach

when it discussed the maximum burden that could be placed on an

individual class member, and stated: "The employer's records as

well as the employer's aid, would be made available to the plain

tiffs for this purpose," 494 F.2d at 259-60. The plaintiffs may

file a motion in the nature of a motion for summary judgment to

n r See Baxter, supra.

12/ Some jobs, such as City Engineer or Chemist, have objective

requirements which are clearly valid and no purpose would be served

by requiring the defendants to compile a list of persons who do

not meet such requirements. The function of such lists is to

identify persons as to whom there is the possibility of a genuine

dispute. If the defendants will identify to plaintiffs the jobs

with requirements they believe to be obviously necessary, plain

tiffs may be able to stipulate — perhaps after examining the

personnel folders of the whites employed in that job or perhaps on

its face — that no list need be compiled of blacks failing to mee-;

that requirement. A list would still have to be compiled showing

the names of blacks who meet that qualification but whom defendant:;

contend to be otherwise unqualified. Plaintiffs would still need

to have access to the personnel folders of blacks in order to

verify the completeness and accuracy of the lists which are com

piled. This suggestion simply avoids compilation of useless and

lengthy lists.

-17-

obviate the need for some or all of the persons appearing on this

list to appear and testify. Adequate grounds for such a motion

include (1) that the reasons assigned are not justified by

business necessity; (2) that the defendants' records show them to

be inaccurate; or (3) that such reasons did not bar whites from

such promotions. If plaintiffs prevail as to a class member, his

name should be stricken from the third list and added in the

appropriate place on the second list. The Special Master should

determine such disputes.

Each class member should then be sent a notice informing

him of (1) his status as a class member; (2) the jobs for which

the Court has found him qualified; and (3) the jobs for which

there is a dispute as to his qualifications and his right to con

test the assertions of the defendants by demonstrating that he

n /possesses the necessary general qualifications. Individualized

notices can be prepared easily and relatively inexpensively by

use of the computer. Each such class member would return a

notice. Plaintiffs would then prepare and file a list of each

class member whose claims require individual hearings. At the

hearing, each such person may show, but does not have the burden

of showing, either that the reasons assigned are not true or that

he had the necessary particular qualifications notwithstanding

them. The defendants have the burden of showing, by clear and

convincing evidence, (1) that the reasons assigned are true; (2)

that the reasons are justified by business necessity; and (3) that

the identical standards have consistently been applied to white

14/

applicants. The Special Master should hear and determine such

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp. held that a class mem

ber has the burden of showing that he or she possessed the neces

sary "general characteristics and qualifications," but that the

employer has the burden of showing any "particular lack of quali

fications." 495 F.2d at 445.

14/ Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. established that the

employer had the burden, that it must be met by "clear and convin

cing" evidence, and that all doubts "should be resolved in favor

of the discriminatee." 491 F.2d at 1380. Baxter established the

job relatedness requirement and the requirement that the standards

had been applied to white employees. 494 F.2d at 444-45.

- 18-

disputes.

At this point, the actual entitlements of each class member

can be determined. The pay rates of those class members who have

been determined to have always been in their "rightful place"

should be compared with that of other employees and should be

given an award if their rate of pay was lower than that of other

employees with similar seniority. Each class member found to be

qualified for a higher paying job would have his actual rate of

pay compared with the rate of pay for the highest paying job for

15/which he is found qualified. If for a particular job classifica

tion the Special Master finds that there are more class members

than available vacancies, the back pay awards for those class

members should be determined on the basis of pro rata shares as

suggested in United States v. United States Steel, supra, 420

F.2d at 1055-56 or some other reasonable method. All these cal

culations could be made by computer using the data already in

computer readable form and pay scales covering the period.

Individual awards should then be adjusted upward to include

(1) interest at 1% per ’annum compounded; and (2) adjustments on

all fringe benefits tied to income levels (e .g., overtime, vaca-

16/

tion pay, and pension). See Pettway, supra. The awards should

be reduced by any withholding deduction required by statute or

regulation.

D . The Period of Limitations As to the City of Albany

Should Begin at April 24, 1970.

In the May 6 ruling, the Court found the defendants liable

for back pay claims for a period of time commencing August 31,

TET See Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969)

and Pettway, supra, 494 F.2d at 261.

16/ The Court should also consider inclusion of an inflation fac

tor to assure payment of back pay amounts in "constant dollars."

I.e., the same present value as the value of income previously

lost due to past discrimination. See English v. Seaboard Coast

Line, supra, 12 F.E.P. Cases 90, 94.

1970 and continuing to the present. The City of Albany is to be

liable for the period commencing March 24, 1972 and continuing to

the present. The individual defendants are to be liable for

claims accruing from August 31, 1970 to the expiration of their

term of office or to the present time, whichever is later. Plain

tiffs suggest certain modifications in this ruling which are

ivconsistent with current law, will afford "make whole" relief,

and will be less burdensome on the individual defendants.

Once the City's liability for discrimination has been

established under Title VII, it must be held liable for back pay

claims to remedy discrimination practiced by it prior to March 24,

1972, the effective date of the 1972 Amendments to Title VII. The

1972 Act has been held to have retroactive effect when it is

invoked to remedy unlawful discrimination committed prior to the

date of the Amendments when such discrimination was prohibited on

other grounds. In such cases, the 1972 Amendments have been held

to be a procedural statute for enforcement of preexisting rights

and as such, "under the general rule favoring retrospective appli

cation of procedural statutes," it is given retroactive effect.

Koger v. Ball, 447 F.2d 702, 707 (4th Cir. 1974). Koger was a

suit brought by an employee of the Social Security Administration

alleging racial discrimination in a denial of promotion. The

alleged discrimination occurred prior to February 22, 1972 when

Koger initiated the grievance process with a letter to the director

of the bureau where he worked. Koger, supra, at 704. No results

were produced by the grievance process, and subsequent to the

effective date of the 1972 Amendments to Title VII, Koger filed

a civil suit under section 717 of the Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16.

The government argued that it was not liable for rules on prac

tices in effect prior to the inclusion of the federal government

under the terms of the Act. The Fourth Circuit rejected this

argument, stating that "Koger's right to be free from racial dis-

--T-

m i

u r See Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra.

- 20-

crimination does not depend on the 1972 Act. Executive Order

11478 previously imposed a duty on officials of his department to

18/

promote employees without regard to their race." Id_. at 707.

In this situation, the Act simply "provided ... a supplemental

remedy for a violation of the existing duty defined by the Order."

19/

Id. at 707. The reasoning in Roger was explicitly adopted in

Womack v. Lynn. 504 F.2d 267 (D.C. Cir. 1974) (en banc). Follow

ing a per curiam reversal based on Womack, Judge Flannery in

Palmer v. Rogers. ___ F. Supp. ___, 10 EPD 5 10,265 (D.D.C. July

11, 1975), awarded back pay under the Act for discrimination com

mitted against a federal employee for a period commencing in May

1971, well before the effective date of the 1972 Amendments.

The same reasoning applies in the present case, for the

plaintiffs right to be free from racial discrimination is not

dependent on Title VII. Under the Fourteenth Amendment, the City

of Albany has long been under an obligation not to discriminate

on the basis of race. As this Court held in its May 6, 1976

decision, jurisdiction to sue in federal court to enforce rights

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment lies here under 28 U.S.C.

20/

§ 1331. . It is clear therefore that the inclusion of the City of

Albany under the Act by the 1972 Amendments simply added a supple

mental remedy against discrimination already prohibited on other

grounds. This conclusion is borne out by the legislative history

relating to the inclusion within the Act of state and local

governments. The House report states:

The clear intention of the Constitution, embodied

in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, is to

prohibit all forms of discrimination. (cont'd)

W Executive Order 11478 became effective August 8, 1969, 3 C.F.R

1969 Comp. 133, 42 USCA § 2000e, note.

19/ Accord, Brown v. GSA, 507 F.2d 1300, 1304-6 (2nd Cir. 1974),

aff'd 44 U.S.L.W. 4704 (June 1, 1976).

20/ The right to be free of racial discrimination in municipal

employment also exists under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983. That right

may be enforced by suits brought against the City's officials.

Jurisdiction lies under 28 U.S.C. § 1343.

- 21-

Legislation to implement this aspect of the Four

teenth Amendment is long overdue, and the committee

believes that an appropriate remedy has been

fashioned in the bill. Inclusion of state and

local employees among those enjoying the protection

of Title VII provides an alternate administrative

remedy to the existing prohibition against discrim

ination perpetuated "under color of state law" as

embodied in the Civil Rights Act of 1871, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983. 2 U.. S. Code & Admin. News p. 2154 (1972)

(emphasis added) 21/

It is, therefore, clear that the 1972 Amendments were intended to

provide an alternate remedial procedure and under "the general

rule favoring retrospective application of procedural statutes,"

22/

Koger v. Ball, supra, at 707, their effect is retroactive.

under 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) and the case law in the Fifth

Circuit, back pay liability accrues from a date two years prior

to the filing of a charge with EEOC. See Johnson v. Goodyear Tire

& Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364, 1378 (5th Cir. 1974). Consequently,

the City's liability for back pay should run from two years prior

to April 24, 1972.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

HERBERT E. PHIPPS

King & Phipps

502 South Monroe Street

Albany, Georgia 31702

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

21/ The House report is cited because the legislation that eventu

ally passed was the House bill H.R.1746 in lieu of the Senate bill

S.2515. See 1972 U.S. Code Congressional and Administrative News

p. 2137. The conference report makes no revision of the meaning

of the paragraph quoted from the House report.

22/ See also, Weise v. Syracuse University, 522 F.2d 397 (2nd Cir.

1975) where the court concluded from a review of the legislative

history that "Congress intended simply to create a new means for

enforcement of preexisting rights." Id. at 411 (footnote omitted).

- 22-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on this 10th day of June, 1976,

I served a copy of the foregoing, Plaintiffs' Proposals for the

Handling of Back Pay, proposed Order and Notice, upon the

following counsel for defendants by United States mail, postage

prepaid:

J. Lewis Sapp, Esq.

Elarbee, Clark & Paul

Coastal States Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

James V. Davis, Esq.

Landau & Davis

P. O. Box 128

Atlanta, Georgia 31702

(Zf-

Attorney for Plaintiffs

- 23-