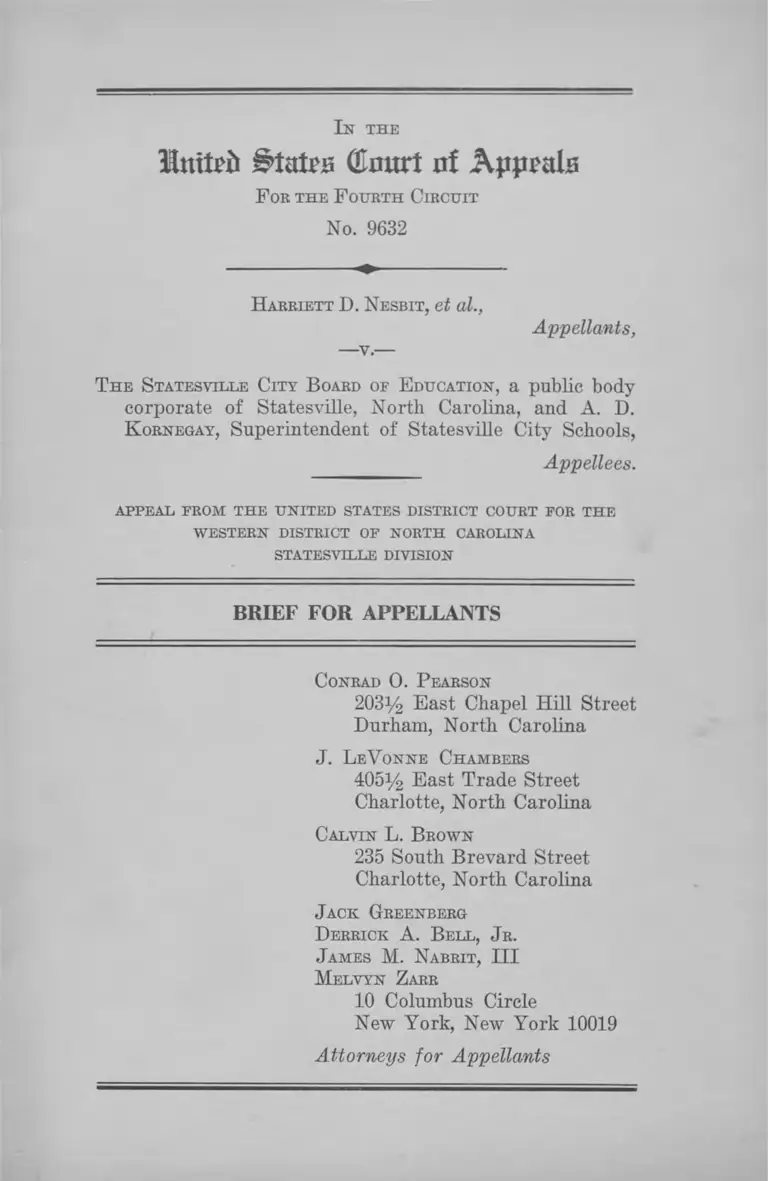

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1965. 3f55b558-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/282accf7-ce89-4512-9430-f1fc6d5055b3/nesbit-v-statesville-city-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Mtuteii Btutia (Ciutrt of Appeals

F or th e F ourth Circuit

No. 9632

H arriett D . N esbit, et al.,

— v .—

Appellants,

T h e S tatesville City B oard of E ducation, a public body

corporate of Statesville, North Carolina, and A. D.

K ornegay, Superintendent of Statesville City Schools,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

STATESVHLE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. L eV onne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Calvin L . B rown

235 South Brevard Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

J ack Greenberg

D errick A. B ell , J r.

J ames M . N abrit, I I I

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 1

Questions Involved ........................................................... 3

Statement of Facts ........................................................... 4

A rgum ent :

I. The Court Below Erred in Approving the

Delay Requested by the School Board, Deny

ing Appellants Shuford and Hamilton and

Others of Their Class and Grade Level the

Right to Transfer to Desegregated Schools,

Where the School Board Failed to Show Any

Specific Administrative Obstacles Requiring

Delay ................................................................... 8

A. The School Board Introduced No Evi

dence to Support Its Request for Delay

ing the Right of Negro Pupils to Request

Transfers to the Junior and Senior High

Schools .......................................................... 8

B. Appellants Shuford and Hamilton Should

Be Transferred Forthwith to the School

of Their Choice .......................................... 13

II. The Court Below Erred in Approving a Final

Plan of Desegregation Which Permits the

School Board to Continue Its Prior Racially

Discriminatory Practices in Administering

the School System and Which Imposes the

Burden Upon Negro Students to Request

Transfers to Obtain a Desegregated Educa

tion ....................................................................... 15

11

III. The Court Below Erred in Refusing to En

join, as an Aspect of Appellees’ Racially Dis

criminatory Policies in the Operation of the

Statesville Public Schools, the Assignment

of Teachers and School Personnel on the

PAGE

Basis of R ace..................................................... 20

Conclusion ......................................................................... 24

T able of Cases

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 249 F. 2d 462 (4th Cir. 1957) ......................... 10

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 ................................ 18, 23

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516 ................................ 18

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia

321 F. 2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963) ...................................... 19

Belo v. Randolph County Board of Education, 9 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 199 (M. D. N. C. 1964) .......................... 12

Board of Education v. Groves, 261 F. 2d 527 (4th Cir.

1958) ................................................................................. 14

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Brax

ton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964) .............................. 21

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 317

F. 2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963) ............................................12,19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ....3, 4, 8,13,15,

16,17,18,19, 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 .......8,16,19, 20

Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County,

Virginia, 327 F. 2d 665 (4th Cir. 1964) ....................... 19

Buckner v. County School Board of Green County,

332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964) .........9,12,15,16,17,19, 23

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) 16

I l l

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S. 263 .................................. 9

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ................................ 8, 9,16, 21

Dowell v. School Board of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (W. D. Okla. 1963) ........... 22

DuBissette v. Cabarrus County Board of Education,

9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 205 (M . D. N. C. 1964) ............... 12

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) .....10,12,14

Gill v. Concord City Board of Education, Civil No.

C-223-S-63, May 7, 1964 .............................................. 11

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683.................... 9,17

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, 304

F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) ..............................................16, 23

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218 .................................................... 9

Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1956) ....... 11

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg,

308 F. 2d 918 (4th Cir. 1962) ...................................... 14

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg, 321

F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) ............................................ 20,22

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962) ....... 12

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61 ...................................... 23

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ............................................16, 23

Lucy v. Adams, 350 U. S. 1 .............................................. 14

/Manning v. Board of Instruction of Hillsborough

County, Florida, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 681 (S. D. Fla.

1962) ................................................................................. 22

Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga, 319 F. 2d

571 (6th Cir. 1963) .......................................................... 21

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County, 305

F. 2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962)

PAGE

16

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 .... 23

Moore v. Board of Education, 252 F. 2d 291 (4th Cir.

1958), aff’g, 152 F. Supp. 114 (D. Md. 1957), cert,

denied sub nom. Slade v. Board of Education, 357

U. S. 906 ......................................................................... 14

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .................................. 18

N. L. R. B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock

Co., 308 U. S. 241 ......................................................... 19

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of

Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) ...................... 16

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of

Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ................... 21

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 .............................. 23

Petit v. Board of Education, 184 F. Supp. 452 (D. Md.

1960) ................................................................................. 14

Sowers v. Lexington City Board of Education, Civil

No. C-20-S-64, M. D. N. C., May 14, 1964 ................... 11

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ...................................... 22

Tillman v. Board of Public Instruction of Volusia

County, Florida, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 687 (S. D. Fla.

1962) ................................................................................. 22

Turner v. Warren County Board of Education, Civil

No. 1483, E. D. N. C., July 6, 1964 .............................. 11

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S.

173 ..................................................................................... 19

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 .....8, 9,12,13, 23

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309 F. 2d

630 (4th Cir. 1962) ........................................................... 16

Ziglar v. Reidsville Board of Education, 9 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 207 (M. D. N. C. 1964) ......................................... 12

iv

PAGE

I n th e

Hmfrii States GJmtrt of Appeals

F or th e F ourth Circuit

No. 9632

H arriett D. N esbit, et al.,

Appellants,

T h e S tatesville City B oard of E ducation, a public body

corporate of Statesville, North Carolina, and A. D.

K ornegay, Superintendent of Statesville City Schools,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

STATESVILLE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This appeal is from an order approving a plan for de

segregation of the public schools of the City of Statesville,

North Carolina entered by the United States District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina, Statesville

Division, on August 29, 1964 (96a). This appeal is brought

under 28 U. S. C. §1291.

The complaint was filed on March 14, 1964, by eleven

Negro school children and their parents on behalf of them

selves and others similarly situated seeking a preliminary

and permanent injunction against the racially discrimina

tory practices of the Statesville City Board of Education in

2

the operation of the Statesville public schools. The com

plaint alleged that the appellee School Board operated the

city schools on a racially discriminatory basis, assigning

Negro and white pupils, teachers, and school personnel to

separate schools solely on the basis of race; that the named

appellants, along with approximately twenty-one other

Negro pupils, filed requests for transfer to white schools

at the close of the 1963 school year; that nine of the re

quests for transfer were granted but that appellants’ ap

plications and the applications of the other Negro pupils

were denied; that adult appellants had petitioned the Board

in September, 1963, requesting that the appellees cease

operating the public schools on a racially discriminatory

basis, but without effecting any change (la-9a).

On May 8, 1964, appellees filed an answer to the com

plaint (13a). Interrogatories were served on appellees in

April, 1964 and answered in May, 1964.

The cause came on for hearing on appellants’ motion

for preliminary injunction on July 29, 1964, at which time

the motion for preliminary injunction was denied by con

sent (86a). The cause was set for hearing on the merits on

July 31, 1964. At the hearing on the merits the appellees

admitted that the public schools in the City of Statesville

are and have been operated on a racially discriminatory

basis (49a, 59a, 87a). The case was accordingly submitted

to the Court upon stipulated facts and testimony introduced

by appellants on the issue of the reasonableness of the plan

proposed by appellees for desegregating the public schools

of the City of Statesville over a three-year period. Follow

ing the hearing the Court issued a Memorandum Opinion,

dated August 3, 1964, in which it found that the plan of

desegregation proposed by the School Board was reason

able, that the named appellants were not entitled to be

transferred to white schools except in accordance with the

3

plan, and that the minor appellants were not proper par

ties to seek relief against appellees’ racially discriminatory

assignment of teachers and professional school personnel

(86a). An order was accordingly entered on August 29,

1964, approving the plan presented by the School Board as

reasonable, denying the right of the named appellants who

were not in grades then affected by the plan to be trans

ferred, denying the relief prayed for by appellants for an

order enjoining the racially discriminatory assignments of

teachers and other professional personnel and retaining

jurisdiction of the cause (96a-97a).

Notice of Appeal was filed on August 31, 1964 (98a),

following which appellants moved for an Injunction Pend

ing Appeal to obtain relief for the named appellants herein

who were denied the right to transfer this school term be

cause they were in grades beyond those then affected by

the plan.

Questions Involved

1. Whether appellants William Shuford, Philip S. Hamil

ton and others of their grade level were deprived of due

process of law and the equal protection of the laws under

the Fourteenth Amendment by the order of the District

Court depriving them of the right to transfer to desegre

gated schools.

2. Whether the evidence submitted by the School Board

supported its burden, required by Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, of justifying delay in desegregating the public

schools of Statesville over a three-year period.

3. Whether the plan for desegregating the Statesville

public schools, which continues indefinitely initial racially

discriminatory assignments of pupils based on dual racial

4

zones and imposes the burden on them to request reassign

ment in order to obtain a desegregated education, complies

with the decisions of the Supreme Court and of this Court.

4. Whether appellants, Negro students and parents, were

denied due process of law and equal protection of the laws

under the Fourteenth Amendment by the order of the Dis

trict Court refusing to enjoin the practice of assigning all

teachers and school personnel on a racially segregated

basis.

Statement of Facts

There are approximately 6,000 students in the public

school system of the City of Statesville, approximately

2,000 of whom are Negroes (31a). The system has 11

public schools, including five elementary schools, 2 junior

high schools and 1 high school for white pupils, and 2

elementary schools and 1 high school for Negro pupils

(31a). Negro and white pupils go to designated Negro

and white schools (20a, 48a, 49a, 52a). Subsequent to the

decision of the United States Supreme Court in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, the School Board took

no action of any kind to end segregation in the schools,

except to adopt the North Carolina Pupil Enrollment

Act, until appellants, along with 21 other Negro pupils,

filed requests for transfers in the summer of 1963 (21a, 36a,

53a). At that time the School Board held two public meet

ings to consider the propriety of permitting such trans

fers and decided to accept five of the first grade applicants

and four of the senior high school applicants (37a, 68a).

The basis for this decision was that the Board felt that the

transfer of the applicants to these grades would “ dis

turb the schools least” (37a). No further steps for de

segregation of the schools were taken by the Board.

5

Following the denial of their requests for transfer, the

appellants herein tiled suit requesting an order requir

ing the desegregation of the Statesville public school sys

tem. At the hearing on July 31, 1963, the appellees, having

admitted that the public schools of Statesville are, and have

been, operated on a racially segregated basis (48a, 49a, 52a,

59a), proposed, and the Court approved, a plan which pro

vided as follows :

A. Beginning with the 1964-65 school year, the de

fendant Board shall institute a free reassignment plan

for grades one through six, and any Negro child who

applies by August 15, 1964, to be transferred to a

school attended entirely or predominantly by mem

bers of another race shall be transferred as of course.

The defendant Board, by August 8, 1964, shall mail

or cause to be mailed to each Negro parent of children

in grades one through six a letter advising such parents

that upon request their children may be transferred

to the school of their choice. Enclosed with said let

ter shall be a simple application form for requesting

such transfer. Applications for transfer for the 1964-

65 school year shall be returned to the defendant Board

on or before August 15, 1964.

B. Beginning with the 1965-66 school year, the plan,

as described in paragraph (1 )(A ), shall extend to

grades ten through twelve, with the following changes:

students in the grades affected by the plan are to be

advised by letter that they have a right to request

transfer to the school of their choice and that such

requests will be granted as of course. Said letter

shall also advise that application forms are available

in the Superintendent’s office and in the office of each

principal and that the forms are to be returned or

6

mailed to the office of the School Board on or before

July 1, 1965.

C. Beginning with the school year 1966-67, the plan

as described in paragraph (1) (B) shall apply to grades

seven through nine (56a-57a, 96a).

In general, appellants objected to the rate of desegrega

tion as not justified by any showing of administrative

obstacles by the School Board; to the failure of the plan

to make provisions for the admittance of appellants Shu-

ford and Hamilton; to the failure of the plan to abolish

dual school zone lines (to provide for the assignments of

pupils according to a single set of lines rather than to

continue the racially discriminatory assignments of pupils,

and transfer the burden to Negro pupils to request trans

fer in order to attend school on the same conditions as

white pupils similarly situated); to the failure of the plan

to provide for desegregation of teachers and school per

sonnel.

At the hearing held on July 31, 1964, appellees, although

recognizing that the burden was upon them to justify the

propriety and reasonableness of the plan, introduced no

evidence and merely stated through counsel that they

thought the plan preferable because it maintained racial

harmony (52a-59a).

Appellants called as a witness, A. D. Ivornegay, Superin

tendent of the Statesville City Public Schools. The Super

intendent testified that in the summer of 1963, thirty Negro

pupils filed requests for transfer: twenty-three to ele

mentary schools, three to junior high schools and four to

high schools (68a-69a); that after studying the records of

the pupils and holding two public meetings, it was felt that

they would have less trouble if all first grade applicants

7

and senior high, school applicants were transferred (69a);

that the Board was concerned about the junior high school

and “ it would be safer and would work better if we

eliminate that particular group until they could adjust to

it” (70a). At the two public hearings, both the white and

Negro people there were rather strong in their opinions

concerning desegregation of the schools (71a). When asked

what would prevent the Board from transferring the named

appellants to the school of their choice for the 1964-65

school term, the Superintendent stated:

“ . . . Right now I think the system last year worked

reasonably well. It wasn’t perfect but we certainly

didn’t have the problems that some other places have

had. There has been an attempt at mutual under

standing and an attempt at seeing things work. I

would much prefer personally to see the thing work

in a way that would bring down less friction and a

way that would interfere less with other children. I

think we can do it so fast that people can balk on what’s

being done. Right now I don’t believe any children

have been hurt. I think the system has stood it rea

sonably well, sir” (71a-72a).

He further stated that there might be some administra

tive problems, but that the basic objective of the appellee

was to move in an orderly fashion and that this was the

reason for the proposed three-year plan (72a).

8

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Court Below Erred in Approving the Delay Re

quested by the School Board, Denying Appellants Shu-

ford and Hamilton and Others of Their Class and Grade

Level the Right to Transfer to Desegregated Schools,

Where the School Board Failed to Show Any Specific

Administrative Obstacles Requiring Delay.

A. The School Board Introduced No Evidence to Support Its

Request for Delaying the Right of Negro Pupils to Request

Transfers to the Junior and Senior High Schools.

Delay in implementing the Supreme Court’s decision in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, has, with

passage of years, been sharply restricted. In the second

Brown decision, 349 U. S. 294, the Supreme Court required

a prompt and reasonable start toward elimination of racial

segregation in the public schools. Delay at that time was

permitted upon a showing by school boards of reasonable

administrative problems in effecting compliance with the

Brown decision. In the absence of such problems, Negro

pupils were to be admitted immediately upon the same

terms and conditions as white pupils similarly situated.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7. Racial hostility was ex

pressly ruled out as an operative factor. Cooper v. Aaron,

supra; Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526. The

Supreme Court pointed out in Watson v. City of Mem

phis, supra, that the constitutional rights here asserted

by appellants are “present rights; they are not merely

hopes to some future enjoyment of some formalistic con

stitutional promise. The basic guarantees of our Consti

tution are warrant for the here and now, and unless there

9

is an overwhelming compelling reason, they are to be

promptly fulfilled.” Id. at 533. Plans and programs, there

fore, for desegregation of public educational facilities

which might have been sufficient eight years ago are not

necessarily so today. Ibid.; Goss v. Board of Education,

373 U. S. 683, 689; Griffin v. County School Board of

Prince Edward County, 377 U. S. 218, 234 (“ The time for

mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out” ) ; Calhoun v. Latimer,

377 U. S. 263.

Despite the mandate of the Supreme Court and of this

Court, see Buchner v. County School Board of Green

County, 332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964), imposing the respon

sibility upon local school authorities to reorganize the pub

lic schools in accordance with the Brown decision, appel

lees, prior to the hearing of this cause, had taken no steps

to eliminate its racially discriminatory policies. Conceding

at the hearing of this cause that its practices in the opera

tions of the Statesville Public Schools deprived appellants

and other Negro pupils of their constitutional rights, appel

lees proposed, and the court below approved, a three year

plan of desegregation which would permit Negro pupils,

after being initially assigned on a racially discriminatory

basis, to apply for transfer. Aside from appellants’ objec

tions to appellees’ continued practice of making initial as

signments on a racially discriminatory basis (see Argu

ment II below), appellants submit that the delay here

approved by the District Court, limiting their rights to

obtain a desegregated education, on the basis that the

delay would preserve racial harmony, clearly disregards

the decisions of the Supreme Court and of this Court.

Cooyer v. Aaron, supra; Watson v. City of Memphis, supra.

It was pointed out as early as the second Brown decision

that compliance with the Supreme Court’s opinion of May

17, 1954 was not to be delayed or obstructed by hostility

10

to it. Similarly, this Court has rejected contentions that

delay in complying with the Brown decision should be

countenanced because of community or state hostility.

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County,

249 F. 2d 462, 465 (4th Cir. 1957): “A person may not

be denied enforcement of rights to which he is entitled

under the Constitution of the United States because of ac

tion taken or threatened in defiance of such rights.”

In rejecting similar contentions as those advanced by ap

pellees here, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit stated in Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd

Cir. 1960):

As we have indicated one of the main thrusts of the

opinion of the Court below is that the emotional impact

of desegregation on a faster basis than that ordered

would prove disruptive not only to the Delaware School

System but also to law and order in some of the locali

ties which would be affected by integration. We point

out, however, that approximately six years have passed

since the first decision of the Supreme Court in Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra, and that the

American people and, we believe, the citizens of Dela

ware, have become more accustomed to the concept of

desegregated schools and to an integrated operation of

their School Systems. Concededly there is still some

way to go to complete an unqualified acceptance but we

cannot conclude that the citizens of Delaware will cre

ate incidents of the sort which occurred in the Milford

area some five years ago. We believe that the people of

Delaware will perform the duties imposed on them by

their own laws and their own courts and will not prove

fickle to our democratic way of life and to our republi

can form of government. In any event the Supreme

Court has made plain in Cooper v. Aaron, 1958, 358

11

U. S. 1, 16, 78 S. Ct. 1401, 1409, 3 L. Ed. 2d 5, the so-

called “ Little Rock case” , that opposition is not a sup

portable ground for delaying a plan of integration of a

public school system. In this ruling the Supreme Court

has acted unanimously and with great emphasis stat

ing that: “ The constitutional rights of respondents

[Negro school children of Arkansas seeking integra

tion] are not to be sacrificed or yielded to * * * violence

and disorder * * * .” We are bound by that decision.

(Emphasis added.)

See also Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93, 96 (5th Cir.

1956): “ We think it clear that, upon the plainest principles

governing cases of this kind, the decision appealed from

was wrong in refusing to declare the constitutional rights

of plaintiffs to have the school board, acting promptly, and

completely uninfluenced by private and public opinion as to

the desirability of desegregation in the community, proceed

with deliberate speed consistent with administration to

abolish segregation in Mansfield’s only high school and to

put into effect desegregation there.” (Emphasis added.)

Moreover, as pointed out by the Third Circuit Court in

Evans, community hostility, even if a permissible consid

eration, should be given least emphasis in those areas where

desegregation has proceeded at a fairly rapid pace than in

those areas where emotional reactions are more intense. In

North Carolina, in more than twenty odd cases which have

been instituted to desegregate public schools, over eighty

per cent resulted in consent orders which permit students

in all grades to be freely transferred upon request. See

Turner v. Warren County Board of Education, Civil No.

1483, E. D. N. C., July 6, 1964; Sowers v. Lexington City

Board of Education, Civil No. C-20-S-64, M. D. N. C., May

14,1964; Gill v. Concord City Board of Education, Civil No.

12

C-223-S-63, May 7, 1964; Belo v. Randolph County Board of

Education, 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 199 (M. D. N. C. 1964);

DuBissette v. Cabarrus County Board of Education, 9 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 205 (M. D. N. C. 1964); Ziglar v. Reidsville

Board of Education, 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 207 (M. D. N. C.

1964). No less than this is required by the decisions of this

Circuit. Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621, 629 (4th Cir.

1962); Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 317

F. 2d 429, 438 (4th Cir. 1963); Buckner v. County School

Board of Greene County, supra at 456. See also Evans v.

Ennis, supra.

Moreover, the appellees have submitted no evidence to

support a finding that racial tension warranted the delay

approved by the District Court. The asserted fear of pos

sible racial discord and problems in the adjustments of pu

pils was apparently based upon the expression of opinion

during the two public meetings of the School Board. The

appellees have conducted no investigation and introduced

no evidence beyond their personal suspicions to support a

finding that racial discord would be provoked by the admis

sion of Negro pupils to all grades during this school term.

Watson v. City of Memphis, supra at 536-37.

Four Negro pupils were transferred to the formerly all-

white high school and five Negro pupils to the formerly all-

white elementary school last school term. The Superinten

dent testified “ that this integration worked reasonably well”

(71a). Despite this prior experience and the absence of

any evidence showing any problems presented by the trans

fer of Negro pupils in 1963 the District Court approved de

laying further transfers to the high school until 1965-66

and to the junior high school until 1966-67. Certainly if

there were any basis for this fear of transferring Negro

pupils to the junior high school and the senior high school

this school term the School Board should have been re

quired to produce some evidence in support of its requested

13

delay. Moreover, recognizing the peaceful accord between

the races in Statesville, as the District Court here has done

(87a n. 1) such good will is best “preserved and extended by

the observance and protection, not the denial, of the basic

constitutional rights here asserted. The best guarantee of

civil peace is adherence to, and respect for, the law.” Wat

son v. City of Memphis, supra, at 537.

B. Appellants Shuford and Hamilton Should Be Transferred

Forthwith to the School of Their Choice.

Not only did the District Court, by its order, deny the

right of Negro pupils in grades unaffected by the School

Board’s plan to transfer to desegregated schools, it also

held that the minor appellants William Shuford and Phillip

S. Hamilton would not be permitted to transfer this school

term to the junior high school, notwithstanding these appel

lants had initially requested transfer in the Summer of 1963

for the 1963-64 school year. The Court reasoned that the

named appellants were entitled to no greater right than

others of their class whom they represented and since the

plan it had approved had not reached their grade level, they

would not be permitted to transfer. Both appellants Shu

ford and Hamilton are in the junior high school and by the

ruling of the Court they will be denied the right to transfer

until the 1966-67 school term. Thus, their right to a deseg

regated education will be postponed a full 12 years after the

Supreme Court’s decision of 1954, solely on the basis of the

unsupported fears of the School Board of provoking racial

discord, a consideration rendered inapposite by the Su

preme Court as early as the second Brown decision.

The question involved is whether the Court must enforce

the “present” and “ personal” constitutional rights of these

appellants. Numerous courts, including this Court, have

dealt with this problem and found different bases for grant

14

ing exceptions to gradual desegregation plans, or for dif

ferent treatment for pupils actively requesting the right to

attend desegregated schools. Jackson v. School Board of

the City of Lynchburg, 308 F. 2d 918 (4th Cir. 1962); Board

of Education v. Groves, 261 F. 2d 527, 529 (4th Cir. 1958);

Moore v. Board of Education, 252 F. 2d 291 (4th Cir. 1958),

aff’g 152 F. Supp. 114 (D. Md. 1957), cert, denied sub nom.

Slade v. Board of Education, 357 U. S. 906; Evans v. Ennis,

supra; Petit v. Board of Education, 184 F. Supp. 452 (D.

Md. 1960); cf. Lucy v. Adams, 350 U. S. 1.

The only relief that these litigants obtain through the ju

dicially approved plan is the satisfaction that perhaps at

some future date they may obtain their constitutional

rights. However real and substantial such satisfaction

may be, it is no legal substitute for immediate judicial pro

tection of the constitutional rights of these appellants. Ap

pellee has made no showing of any kind of any administra

tive obstacles to appellants’ immediate admission. The

immediate admission of these two minor appellants will in

no way interfere with the administration of the Statesville

schools, and should be ordered forthwith as was done three

days after the argument in Jackson v. School Board of City

of Lynchburg, 308 F. 2d 918 (4th Cir. 1962).

15

II.

The Court Below Erred in Approving a Final Plan of

Desegregation Which Permits the School Board to Con

tinue Its Prior Racially Discriminatory Practices in Ad

ministering the School System and Which Imposes the

Burden Upon Negro Students to Request Transfers to

Obtain a Desegregated Education.

At the time of the hearing of this cause, on July 31, 1964,

the appellees conceded that they discriminated against

appellants and other Negro pupils in the Statesville school

system in the operation and administration of the States

ville public schools. Negro pupils and teachers were as

signed to the various schools on a racially discriminatory

basis. The school budgets, disbursement of school funds,

and extra-curricular activities were planned and sanc

tioned on the basis of race. In short, except for the trans

fer of 9 Negro pupils prior to the beginning of the 1963-64

school year, the public school system of Statesville was

administered on the same racially discriminatory basis

as before the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown. At the

hearing of this cause, on July 31, the school board pro

posed, and the Court below approved, as a permanent

plan for desegregation, a proposal which permits the con

tinued discriminatory practices of the board (including con

tinued initial assignments of entering pupils based on dual

racial zones and a segregated feeder system), and shifts

to Negro school pupils the burden of desegregating the

schools by requesting transfers from all-Negro schools

to white schools. Appellees submit that such a plan falls

far short of the requirements of Brown v. Board of Educa

tion and other implementing decisions, particularly Buck

ner v. County School Board of Greene County, 332 F. 2d

452 (4th Cir. 1964).

16

In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, the Su

preme Court condemned racial segregation in public school

systems. State authorities were given the responsibility

of reorganizing the public schools to eliminate their prior

practice of maintaining racially segregated school systems.

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294; Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. It is clear therefore, that a school

board does not satisfy the requirements of the Brown

decision merely by superimposing upon a bi-racial school

system procedures permitting Negro students, who are

initially assigned to segregated schools pursuant to bi-racial

school zone lines, to apply for transfer to schools to which

white pupils similarly situated are initially assigned.

This Court, and other Circuit Courts, have held that an

essential element of a desegregation program is the elim

ination of dual attendance areas and racial feeder systems.

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d

72 (4th Cir. 1960); Green v. School Board of the City of

Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962); Marsh v. County

School Board of Roanoke County, 305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir.

1962); Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309

F. 2d 630 (4th Cir. 1962); Buckner v. County School Board

of Greene County, 332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964); North-

cross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 302

F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962); Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, 308 F. 2d 491 (5th Cir. 1962).

As this Court pointed out only recently in Buckner,

supra at 454, in initially assigning all Negro pupils to

segregated schools and permitting them to transfer out of

these schools only upon request for reassignment, the

School Board transfers the initiative in seeking desegrega

tion to Negro pupils. Such a practice has appropriately

been condemned because it unconstitutionally transfers the

burden of initiating desegregation to Negro pupils and

17

imposes a burden upon such pupils not required of white

pupils similarly situated.1

Moreover, such plans, because of the existing racial pat

tern, perpetuate rather than eliminate the racially seg

regated school systems condemned in Brown. Under the

type of system in effect in Statesville, white students will

continue to attend schools traditionally attended by mem

bers of their race without regard to the availability of a

Negro school closer to their homes. Similarly, the mo

mentum of 100 years of segregation will continue to propel

the Negro children to the school that he and others of his

class have been accustomed to attending, irrespective of

the distance to his home. And if the locality is one where

there is public hostility to desegregation of the schools,

many Negro families will be altogether reluctant to risk

antagonizing white members of the community and thereby

chance the possibility of some form of reprisal. The “ re

pressive effect” on Negroes of “ private attitudes and pres

sures” inherent in a system which places the burden of

1 In Buckner, the Court said at 454:

“By initially assigning Negro pupils to segregated schools

and then permitting them, only upon application to the Pupil

Placement Board, to transfer out of these segregated schools,

the School Board has in effect formulated a plan which will

require each and every Negro student individually to take

the initiative in seeking desegregation.

* * * #

“ It is too late in the day for this school board to say that

merely by the admission of a few plaintiffs, without taking

any further action, it is satisfying the Supreme Court’s

Mandate for ‘good faith compliance at the earliest practicable

date.’ ”

See also Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683, 688:

“ The recognition of race as an absolute criterion for grant

ing transfers which operate only in the direction of schools

in which the transferee’s race is in the majority is no less

unconstitutional than its use for original admission on sub

sequent assignment to public schools.” (Emphasis added.)

18

desegregating the schools on individual Negro families

alone renders the system constitutionally vulnerable. Cf.

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399, 403; Bates v. Little Rock,

361 U. S. 516, 524; NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449.

Other factors which will tend to discourage Negro families

from voluntarily transferring their children out of Negro

schools include: (1) economic insecurity resulting from

the Negro’s generally inferior economic position in relation

to that achieved by whites; (2) severance of a child’s social

relationships in a Negro school and his relative social iso

lation upon transferring to a school which previously has

been all-white; and (3) the fear of academic failure follow

ing transfer, when the Negro child will he in competition

with white children who (because of differences between

all-Negro and white schools) are likely to be more advanced

scholastically.

One of the principal bases for the Supreme Court’s

decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347

U. S. 483, is the finding that Negro children attending all-

Negro schools suffer solely by virtue of their being segre

gated from white children, and thereby receive an inferior

educational experience {Id. at 493-494). Compliance with

Brown is the responsibility of the public school authori

ties who are bound by the Constitution to provide equality

of educational opportunity to all children without distinc

tion as to race. Where, as in Statesville, the school authori

ties, as instrumentalities of the State, are responsible for

having established the all-Negro schools in the first in

stance and for assigning children to them solely on the

basis of race, these same authorities may not now turn

their backs on the problem and tell the Negroes that the

responsibility for desegregating the schools rests with them

through exercise of the option to transfer. As this Court

has stated: “ It is upon the very shoulders of school boards

that the major burden has been placed for implementing

19

the principles enunciated in the Brown decisions. * # *

‘School authorities have the primary responsibility for

elucidating, assessing, and solving these [varied local

school] problems [attendant upon desegregation].’ ” Bell

v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, 321 F. 2d

494, 499 (4th Cir. 1963), quoting Brown v. Board of Educa

tion of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294, 299; Buckner v. County

School Board of Greene County, Virginia, 332 F. 2d 452, 455

(4th Cir. 1964). Accord: Bradley v. School Board of City

of Richmond, Virginia, supra, 317 F. 2d at 436-438 (4th

Cir. 1963); Brown v. County School Board of Frederick

County, Virginia, 327 F. 2d 655 (4th Cir. 1964).2 This in

cludes the elimination of the racially discriminatory poli

cies and practices in the assignment of teachers and school

personnel (see Argument III below) and in the sanctioning

of school budgets, appropriation of school funds, the admin

2 Analogies exist in other fields of law where, in order to rectify

a course of unlawful conduct, the wrongdoer is required, under

equitable doctrine, to do more than merely cease his activities,

but is compelled to take further affirmative steps to undo the

effects of his wrongdoing. Under the Sherman Antitrust Act

unlawful combinations are commonly dealt with through disso

lution and stock divestiture decrees. See, e.g. United States v.

Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S. 173, 189, and eases cited. And

early in the history of the National Labor Relations Act, it was

recognized that disestablishment of an employer-dominated labor

organization “may be the only effective way of wiping the slate

clean and affording the employees an opportunity to start afresh

in organizing for the adjustment of their relations with the em

ployer.” N. L. R. B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock

Co., 308 U. S. 241, 250; see also American Enka Corp. v. N. L. R. B.,

119 F. 2d 60, 63 (C. A . 4 ) ; Western Electric Co. v. N. L. R. B.,

147 F. 2d 519, 524 (C. A . 4 ) . In Sperry Gyroscope Co., Inc. v.

N . L . R . B., 129 F. 2d 922, 931-932 (C. A . 2 ), Judge Jerome Frank

compared N. L. R. B. orders requiring disestablishment of employer-

dominated unions to “the doctrine of those cases in which a court

of equity, without relying on any statute, decrees the sale of

assets of a corporation although it is a solvent going concern,

because the past and repeated unconscionable conduct of domi

nating stockholders makes it highly improbable that the improper

use of their power will ever cease” (citing cases).

20

istering of extra-curricular activities and any other aspect

in the administration and operation of the public schools of

Statesville on a racial basis. Jackson v. School Board of

the City of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963).

III.

The Court Below Erred in Refusing to Enjoin, as an

Aspect of Appellees’ Racially Discriminatory Policies in

the Operation of the Statesville Public Schools, the As

signment of Teachers and School Personnel on the

Basis of Race.

Segregation of teachers in public schools was and is an

integral part of the segregated public school system cre

ated by law. The Statesville system continues the policy

of the segregation era by assigning only Negro teachers

to work in the all-Negro public schools. No Negro teachers

are assigned to teach white pupils. The Board admittedly

has no plans to change this practice (49a), though ap

pellants have sought, through the complaint filed in this

action, to have restrained, appellees’ racial assignment of

teachers and other professional school personnel.

In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, the

Supreme Court held that “ in the field of public education

the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal.” Id. at 495.

The Court quoted with approval language of the United

States District Court for the District of Kansas setting

forth the proposition that “ segregation with sanction of

law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational

and mental development of Negro children and to deprive

them of some of the benefits they would receive in a

racial[ly] integrated school system.” Id. at 494. In its

later decision on the relief to be granted (Brown v. Board

21

of Education, 349 U. S. 294), the Supreme Court repeatedly

referred to the requirement that school “ systems” be de

segregated, and directed that the District Courts “ consider

the adequacy of any plans that defendants may propose

to meet these problems and to effectuate a transition to a

racially nondiscriminatory school system” . Id. at 300-01.

Implicitly recognizing the effect that personnel assignments

had upon the placement of pupils, the Supreme Court ex

pressly listed personnel problems as one of the administra

tive matters that courts might consider in ruling upon the

timing and adequacy of desegregation plans.

Subsequently, in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7, the Court

reaffirmed and restated the requirements of the Brown

decisions, emphasizing that school “ systems” were involved:

State authorities were thus duty bound to devote every

effort toward initiating desegregation and bringing

about the elimination of racial discrimination in the

public school system. (Emphasis added.)

Various District Courts and Courts of Appeals have

considered the problem of teacher desegregation in recent

years and have found that Negro pupils, as an aspect of

their relief against a school board’s maintenance of a seg

regated school system, may obtain relief against the as

signment of teachers and school personnel on a racial basis.

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton,

326 F. 2d 616, 620 (5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 377 U. S.

924 (1964); Northcross v. Board of Education of the City

of Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ;3 Dowell v.

3 The Court below cited Mapp v. Board of Education of Chatta

nooga, 319 F . 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963) in support of its holding.

The Sixth Circuit in Northcross, supra, indicated that it regarded

Mapp as supporting the right of pupils to challenge teacher segre

gation (333 F . 2d at 666).

22

School Board of the Oklahoma City Public Schools, 219

F. Supp. 427 (W. D. Okla. 1963); Tillman v. Board of

Public Instruction of Volusia County, Florida, 7 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 687 (S. D. Fla. 1962); and see Manning v.

Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, Flor

ida, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 681 (S. D. Fla. 1962).

Furthermore, the Fourth Circuit held that a complaint

seeking a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school

system was sufficiently broad to bring before the court all

aspects of the school’s operation, including desegregation

of staff and faculty. Jackson v. School Board of the City

of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963). This was,

in the very least, an implied holding that teacher deseg

regation issues were properly a part of school cases. Upon

remand in the Jackson case, the District Judge so regarded

it. In that case Judge Michie has entered orders requiring

the School Board to present a plan dealing with faculty

and staff desegregation (unreported Memorandum dated

September 6, 1963, Jackson v. School Board of the City

of Lynchburg, C. A. No. 534 (W. D. V a.)), and, later,

rejecting a school board plan for teacher desegregation

as too indefinite and ordering the board to present a more

specific plan (Jackson v. School Board, supra, unreported

order dated June 17,1964).

In a school system where parents and pupils are allowed

to exercise some choice as to which schools they attend,

such as that proposed by appellees here, the existence of

all-Negro and all-white faculties inevitably works to en

courage parents to choose schools on the basis of the race

of the teachers. It is evident to all that many parents re

gard the teaching staff of a school as important in apprais

ing its desirability. Cf. Sweat-t v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629.

Certainly, in the context of a school system which has for

years been segregated by law, the continued maintenance

23

of all-Negro and all-white school faculties affects and influ

ences the parents’ choices, and fosters segregation. This

has been implicitly recognized in another context by this

Court. See Jones v. School Board of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d

72, 77 (4th Cir. 1960); Green v. School Board of the City

of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118, 121 (4th Cir. 1962); Buckner

v. County School Board of Greene County, 332 F. 2d 452,

454 (4th Cir. 1964).

Even prior to the Brown decision the Supreme Court

condemned internal segregation practices within a state

university such as segregating a Negro student in his use

of the library, cafeteria and within the classroom. Mc

Laurin Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. Certainly,

teacher segregation is more intimately related to the edu

cational process than a seat in the lunchroom or the library,

as in the McLaurin case. If Mr. McLaurin were “handi

capped in the pursuit of effective graduate instruction,” by

these practices, then, a fortiori, Negro pupils as a whole are

handicapped by the continuation of a practice such as

teacher segregation, which, like pupil segregation, was

a part of the system of public school segregation premised

on the theory of Negro inferiority. Appellants submit that

there can be little doubt that teacher segregation is just

as offensive to the Fourteenth Amendment as racial segre

gation commanded by law or administrative practice on

ballots (Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399); in restaurants

{Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244); among courtroom

spectators {Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61); or in public

parks {Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526).

24

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Bespectfully submitted,

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. L eV onne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Calvin L . B rown

235 South Brevard Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

J ack Greenberg

D errick A. B ell, J r.

J ames M. N abrit, I I I

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

38