Adams v. Bennett and Women's Equity Action League v. Bennett Memorandum Opinion and Order

Public Court Documents

December 11, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Adams v. Bennett and Women's Equity Action League v. Bennett Memorandum Opinion and Order, 1987. 44dd4ed8-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/282f0d3d-c1de-40e7-9907-8a27b3e437cd/adams-v-bennett-and-womens-equity-action-league-v-bennett-memorandum-opinion-and-order. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

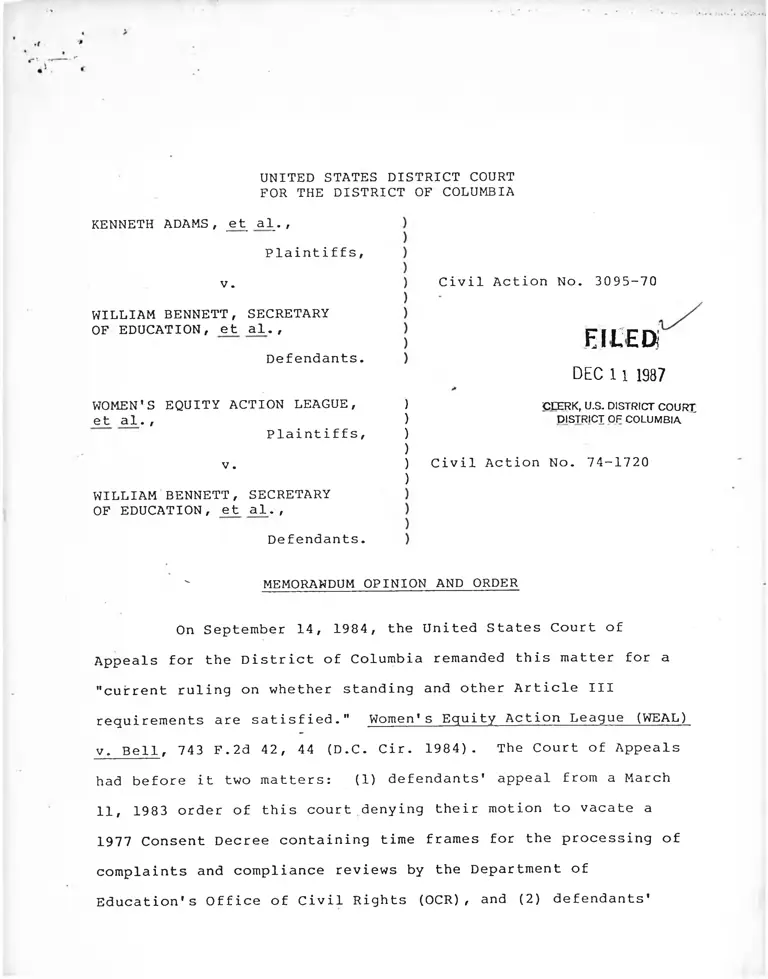

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

KENNETH ADAMS , _et_ al_. ,

Plaintiffs,

v .

WILLIAM BENNETT, SECRETARY

OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants.

WOMEN'S EQUITY ACTION LEAGUE,

et al., Plaintiffs,

v .

WILLIAM BENNETT, SECRETARY

OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants.

" MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

On September 14, 1984, the United States Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia remanded this matter for a

"current ruling on whether standing and other Article III

requirements are satisfied." Women's Equity Action League (WEAL)

v. Bell, 743 F.2d 42, 44 (D.C. Cir. 1984). The Court of Appeals

had before it two matters: (1) defendants' appeal from a March

11, 1983 order of this court denying their motion to vacate a

1977 Consent Decree containing time frames for the processing of

complaints and compliance reviews by the Department of

Education's Office of Civil Rights (OCR), and (2) defendants'

Civil Action No. 3095-70

FILED

DEC 11 1987

) CLERK, U.S. DISTRICT COURT,

) DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

)

)) Civil Action No. 74-1720

)

appeal from a second order of this court dated March 24, 1983,

granting injunctive relief which reimposed, also with some

modifications, the time frames and associated provisions relating

to higher education which had also been part of the 1977 Consent

Decree. The appeals raised important questions regarding whether

the 1977 and 1983 time frame decrees were authorized by the

applicable statutes and Executive Orders, whether the decrees,

involving judicial intervention in the day-to-day operations of

agencies of the Executive Branch, violated the separation of

powers doctrine and whether the decrees, under traditional equity

concepts, were any longer necessary or appropriate.

The Court of Appeals did not reach the merits of these

contentions. Rather, in view of defendants' basic argument that

this court had "lost sight of the specific goals of the initial

suit", and embarked on a policy of supervising Executive Branch

activity.for an indefinite period of time, the Court of Appeals

found itself "obliged to consider on [its] own motion threshold

Article III impediments to the initiation and maintenance of

[this] action." WEAL, 743 F.2d at 43. The two specific Article

III concerns raised by the Court of Appeals involved questions of

standing and mootness. The Court expressed no opinion on these

threshold issues or on the merits of defendants' underlying

complaint concerning the legality of the two decrees.

Accordingly, it vacated the orders from which appeal had been

taken and remanded the case to this court "for consideration

whether, in harmony with the case-or-controversy limitations...

this action may proceed in court". Id. at 44. In taking this

- 2 -

action, the Court of Appeals placed great reliance on the

decision of the Supreme Court in Allen v Wright, 468 U S. 737

(1984), handed down during the pendency of the appeal. In Allen,

the Supreme Court raised the question whether "absent actual

present or immediately threatened injury resulting from unlawful

government action," it is an appropriate role for federal courts

to act as "virtually continuing monitors of the wisdom and

soundness of Executive action". Id. at 760 (quoting Laird v.

Tatum, 408 U.S. 1, 15 (1972)). This is a question to which we

will return after, a brief detour.

I. Background

It is appropriate at this point, before we begin our

consideration of the Article III concerns raised by the Court of

Appeals, to set forth briefly the relevant history of this

case. This litigation has its roots in the distant past.

Several actions have been joined to give it its present shape and

form. The common thread underlying each of the several

1. The original Adams litigation presented a challenge to the

Department of Health, Education & Welfare's policy of non

enforcement of Title -VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §§2000d et seq. (1982), with respect to

seventeen (17) southern and border states. In 1975 a similar

suit was filed against HEW alleging that the agency was failing

to enforce Title VI in thirty three (33) northern and western

states as well. Judge Sirica found HEW in default of its

statutory obligations. Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215

(D.D.C. 1976). Relief in that case was for the most part

consolidated with Adams in the December 29, 1977 order. The 1977

Consent Decree also expanded the scope of the litigation by

including a separate suit brought by the Women's Equity Action

League in 1974. In that complaint, WEAL alleged that the

t of Health, Education & Welfare (HEW) and the

-3-

complaints in this litigation, however, is the alleged improper

grant of federal funds in violation of various statutes and

regulations. These statutes and regulations include Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended (Title VI), 42 U.S.C.

§2000d et seq. (1982), Title IX of the Education Amendments of

1972 (Title IX), 20 U.S.C. §1681 (1982), Executive Order No.

11246, as amended by Executive Order 11375, and §504 of the

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. §794 (1982). Plaintiffs

also present a constitutional challenge to defendants' conduct.

The original Adams case presented a challenge to HEW's

policy of non-enforcement of Title VI with regard to claims of

racial discrimination. In 1976 additional groups and individuals

were allowed to intervene in the Adams litigation on the basis of

HEW's representation that the Title VI enforcement obligations

previously imposed by this court made it impossible to devote

sufficient resources to the review and processing of Title IX sex

discrimination and Title VI national origin discrimination

complaints. In October 1977, the National Federation of the

Blind also intervened, complaining of lack of enforcement of §504

of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and §904 of the Education

Amendment Act of 1972 with respect to discrimination based on

handicap. Thus, the entry of these plaintiff-intervenors in the

Adams suit greatly expanded the statutory scope of the

litigation.

Department of Labor (DOL) had both failed to meet their

obligation to enforce Executive Order 11246 with respect to

institutions of higher education, and that HEW had failed to

comply with its Title IX obligations.

As an indication of the breadth of this extensive and

protracted

Adams plain

individual

intervenor

of two (2)

Memorandum

litigation, it is signif

tiffs consist of forty (

. 2plaintif f-mtervenors a

organizations. The cur

individuals and six (6)

in Support of their Moti

icant to note

40) individual

nd five (5) pi

rent WEAL plai

organizations,

on -to Dismiss

that the current

s, eight (8)

aintiff-

ntiffs consist

̂ Defendants'

(Defs. Memo.) at

5.

A . Court of Appeals Pronouncements

In the original Adams case filed in 1970, we held that the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare and its Director of

the Office of Civil Rights did not have further discretion but

were under an affirmative duty to commence enforcement

proceedings against public educational institutions to ensure

compliance with Title VI where efforts towards voluntary

2. Plaintiff-intervenors Martinez, et al. are four

individuals: Jimmy Martinez, Ben G. Salazar, Pablo E. Ortega and

Arturo Gomez, Jr.. Plaintiff-intervenors Cynthia L. Buxton, et

al. are two individuals: Cynthia L. Buxton and Kay Paul

Whyburn. Finally, individual handicapped plaintiff-intervenors

are Douglas J. Usiak and Joyce F. Stiff.

3. These organizations include the Women's Equity Action League

(WEAL), the National Organization for Women (NOW), the National

Education Association (NEA), the Federation of Organizations for

Professional Women (FOPW) and the National Federation for the

Blind (NFB).

4. These organizations include WEAL, NOW, NEA, FOPW, the

Association for Women in Science (AWIS), and the United States

Student Association (USSA). Unless otherwise indicated, both the

plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenors in Adams and the plaintiffs

in WEAL will be collectively referred to as "plaintiffs."

-5-

compliance were not attempted or successful. Adams v.

Richardson, 351 F. Supp. 636, 641 (D.D.C. 1972). Subsequently,

we ordered the agency to take certain corrective measures. Adams

v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp. 92 (D.D.C. 1973). With minor

modifications not here relevant the Court of Appeals, sitting en

banc, affirmed this court's decision. Adams v. Richardson, 480

F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973)[hereinafter "Adams I"]. Although our

order directed that the commencement of enforcement proceedings

take place within certain time frames, the appellate court was

careful to emphasize that: *

the order merely requires initiation

of a process which, excepting contemptuous

conduct, will then pass beyond the District

Court's continuing control and supervision-

id. at 1163 n.5. (Emphasis added).

A further interpretation of the boundaries of our 1973

order arose later in another context. In March, 1979, the

Department of Education (DE) , which had succeeded to HEW's

jurisdiction, rejected the State of North Carolina's

desegregation plans, and subsequently commenced enforcement

proceedings against the State.5 -In response, North Carolina

filed suit in federal court in North Carolina to enjoin the

5 These proceedings were commenced as the result of an order we

issued on April 1, 1977 in Adams v. Califano, 430 F. Supp. 118

(D.D.C. 1977). This order, denominated the Second Supplemental

Order, directed defendant to notify six southern states,

including North Carolina, that their plans for higher education

were not adequate. The Second Supplemental Order set time frames

fbr the submission of final guidelines and revised desegregation

plans by each state, and for the acceptance or rejection of such

plans by defendants.

- 6 -

administrative hearing and to prevent the DE from deferring grant

payments. The North Carolina court enjoined the deferral of

payments but permitted the enforcement proceeding to continue.

After the Department had completed the presentation of its case

in chief, after several months of hearings, the parties entered

into a consent settlement, which the North Carolina court

approved. North Carolina v. Department of Education, Memo. Op.,

No. 79-217-CIV-5 (E.D.N.C. July 17, 1981). At this juncture, the

Adams plaintiffs, who were not parties to the North Carolina

suit, sought injunctive relief from this court to enjoin the

Department from acceding to the proposed consent settlement. We

declined to grant the requested relief, for reasons of comity as

well as limitations in the scope of our original 1973 order.

Adams v. Bell, Transcript at 26-30, No. 70-3095 (D.D.C. June 25,

1981). The Court of Appeals for this Circuit, again sitting en

banc, affirmed our decision. Adams v. Bell, 711 F.2d 161 (D.C.

*Cir. 1983) [hereinafter "Adams II"] . It found that the purpose of

the 1973 decree was to require the Department to meet its

responsibilities under Title VI by the commencement of formal

proceedings or through voluntary compliance, and that our decree

did not extend to details of particular enforcement programs,

including the supervision of the Department's settlement with

North Carolina.^ Id. at 165.

6 The Court of Appeals expressly stated that it did not "pass on

the scope of the District Court's authority with reference to

other possible Department of Education actions. . . ." Adams

II, 711 F.2d at 165. This exclusion covers the content of our

subsequent orders of March 11, 1983 and March 24, 1983, which are

the focus of the present litigation. Id. at 165 n. 25.

-7-

The opinions of the appellate court in Adams I and Adams II

are the only Court of Appeals decisions concerning the proper

reach and meaning of our original order. They both affirm the

original direction of this litigation, and emphasize the limited

nature of our intervention.

We turn now to the events leading up to the 1977 Consent

Decree, the validity of which was indirectly challenged in the

appeal in WEAL, supra.

B . The 1977 Consent,Decree

In 1975, in response to plaintiffs' suit alleging delays

in the administrative processing of complaints in elementary and

secondary education cases, we ordered the agency to proceed

against defaulting school districts and imposed time frames

controlling future enforcement activities by the agency. Adams v.

Weinberger, 391 F.Supp. 269 (D.D.C. 1975). This consent order

was negotiated by the parties and served to supplement our

original February 16, 1973 order. It came to be known as the

First Supplemental Order, and was the first of a series of

orders7 establishing time frames for each stage of the

administrative process. Part F of this order directed attention

for the first time to future Title VI enforcement activities,

setting time limitations for the handling of future complaints

and compliance reviews. Id. at 273. Part F of the First

7 A partial list of the relevant decisions and orders is

attached hereto.

- 8-

Supplemental Order was modified by an unpublished June 14, 1976

order of this court which established separate guidelines for the

administrative processing of Title VI and Title IX complaints,

compliance reviews, and Emergency School Aid Act cases. Adams v.

Matthews, No. 3095-70 (D.D.C. June 14, 1976). A so-called Second

Supplemental Order concerning the acceptable ingredients for the

desegregation of higher education in the states was issued on

April 1, 1977. Adams v. Califano, 430 F.Supp. 118 (D.D.C. 1977).

In mid-1977, the Adams plaintiffs were again before this

court seeking further relief for noncompliance with the 1975

order referred to above and with that portion of the 1973 order

relating to special purpose and vocational schools. Plaintiffs

sought compliance with previously imposed time frames and other

administrative requirements. The court, after an extensive

hearing, directed the parties to enter into negotiations. These

negotiations resulted some months later in the 1977 Consent

Decree issued on December 29, 1977. Adams v. Califano, No. 3095-

70 (D.D.C. December 29, 1977).

The 1977 Decree was more extensive than the orders

entered previously and differed from them in several respects.

First, the Decree broadened the court's review of HEW enforcement

activities to include all fifty states.8 Second, in addition to

Title VI, it applied to complaints and compliance reviews under

8. As noted previously, the expanded geographical scope of the

litigation resulted from the consolidation of this action with

Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215 (D.D.C. 1976), a case

involving similar complaints against defendants with regard to 33

northern and western states.

-9-

Title IX, Executive Order No. 11246,9 and § 504 of the

Rehabilitation Act of 1973.10 Third, it set forth a number of

additional procedural steps to be performed following receipt of

a completed complaint. Id. at TMI8 (a) , 9 and 11.

It is a fair summary to state that the emphasis in the

original order of 1973 stemmed from defendants' abdication of

their statutory responsibility in pursuing a conscious policy of

non-enforcement. The 1973 order, as stated previously, rejected

the agency claim that it had almost unfettered discretion in this

area, and, instead, directed that enforcement proceedings be

commenced within certain limited time frames. These time frames

have become more detailed with the issuance of each new order, in

part because of defendants' chronic delays and in part because of

the asserted necessity for these delays during the various stages

of the administrative proceedings. The Consent Decree of

December 29, 1977 was a culmination of this process and attempted

to address these difficulties in a single document fifty-four

(54) pages in length comprised of eighty-eight (88) separately

numbered paragraphs. Limitations of space prevent a detailed

catalogue of these provisions. It -is sufficient to say that the

9 Prior to the date of the December 1977 Decree, HEW had

responsibility under the Office of Federal Contract Compliance

Programs (OFCCP) for the enforcement of Executive Order No.

11246, including sex based claims of employment discrimination in

institutions of higher education with substantial government

contracts. Teh months after the December 1977 Decree, OFCCP

assumed this responsibility.

10. The Decree also expanded the scope of the 1970 litigation,

as noted earlier, by linking a separate suit brought by WEAL

against HEW and the DOL. All parties agreed that the December

29, 1977 Consent Decree would apply to the WEAL action as well.

- 10-

parties, in good faith, made a serious attempt to settle all

outstanding differences existing between them.

In August 1982 defendants moved to vacate the 1977

Consent Order asserting changes in fact and law, as well as the

need for a deeper consideration of the facts in light of

experience. We denied defendants' motion to vacate on March 11,

1983. On the same day, in response to- Motions for Orders to Show

Cause filed by the Adams and WEAL plaintiffs, we entered a

detailed order of thirty-seven (37) pages modifying the 1977

Consent Order as it applied to the DE aqd the DOL. On March 24,

1983, in response to Plaintiffs' Renewed Motion for Further

Relief Concerning State Systems of Higher Education, we entered a

separate order, in which we found that five southern states 11

had defaulted in their commitments under previously accepted

desegregation plans in violation of Title VI. Adams v Bell, No.

3095-70 (D.D.C. March 24, 1983). We ordered defendants to' ̂

require these states, with the exception of Virginia, which had

recently submitted a provisionally approved plan, to submit

further plans within a limited time frame or to commence formal

enforcement proceedings no later than September 15, 1983. Id.

Injunctive relief was also granted requiring defendants to take

similar action with respect to Pennsylvania and Kentucky, and was

denied with respect to Texas, West Virginia, Missouri and

Delaware. Id.

11 These states include Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, Virginia and

North Carolina. The order applied to North Carolina's community

colleges only.

- 11-

Defendants appealed from this court's denial of their

motion to vacate the 1977 Consent Decree and from the March 24,

1983 order relating to statewide systems of higher education. It

is this appeal which is the subject of the Court of Appeals

remand of September 14, 1984. WEAL, supra.

II. Discussion

Because the remand raised issues of standing and

mootness, defendants were given an opportunity to engage in and

complete discovery on these issues. After extensive discovery,

defendants filed a Motion to Dismiss on the grounds that (1)

plaintiffs lack standing; (2) the doctrine of separation of

powers defeats standing as a matter of law and (3) the claims

of the plaintiffs in WEAL and the plaintiff-intervenors in the

Adams litigation are moot. The Adams plaintiffs, in opposition

*to defendants' Motion to Dismiss, assert (1) that plaintiffs are

suffering concrete personal injuries; (2) that these injuries

are fairly traceable to defendants' conduct and (3) that such

injuries are likely to be redressed by a decree of this court.

After distinguishing Allen v. Wright, supra, they contend that

defendants' separation of powers argument is lacking in

substance. They point to the necessity of time frames to meet

12 On May 9, 1984, while this action was pending on appeal, we

permitted plaintiffs to add new plaintiffs and certified the

action as a class consisting of the newly added plaintiffs and

certain others. Our January 17, 1985 order confined discovery to

the issue of standing "without relitigating the certification

order of May 9, 1984."

- 12-

defendants' chronic delays in the enforcement of defendants'

obligations under Title VI and other statutes and the fact that

the time frames were consented to by the appropriate officials of

two different political administrations. Oppositions to

defendants' Motion to Dismiss have been filed on behalf of

WEAL,13 as well as other Adams intervenors.14

A . Standing

Federal courts, as has long been recognized, are courts

of limited jurisdiction. This jurisdiction, under Article III,

Section 2 of the Constitution, is limited to the adjudication of

"cases" and "controversies." A plaintiff must first meet the

requirements of standing before seeking to invoke the authority

of a federal court to decide the merits. Warth v. Seldin, 422

U.S. 490, 498 (1975). As the result of numerous cases arising in

varying factual contexts, it is well settled that the doctrine of

standing encompasses both a prudential component and a core

13. As noted previously, WEAL filed its complaint in 1974 based

upon defendants' alleged violations of Title IX and Executive

Order No. 11246. This Weal complaint has been processed with the

original Adams Title VI litigation since the issuance the 1977

consent decree.

14 Oppositions were filed on behalf of the Mexican-American

plaintiff-intervenors, plaintiff-intervenor National Federation

of the Blind, and others. These interventions are predicated on

alleged violations of statutes other than Title VI. Since the

issues raised by defendants' Motion to Dismiss are equally

applicable to all intervenors, the oppositions of the above

indicated parties will not be separately treated.

-13-

component stemming directly from Article III and resting

ultimately on the concept of separation of powers. Standing and

the overlapping mootness, ripeness and political question

doctrines concern "the constitutional and prudential limits to

the powers of an unelected, unrepresentative judiciary in our

kind of government". Vander Jagt v. O'Neill, 699 F.2d 1166, 1179

(D.C. Cir. 1983)(Bork, J., Concurring).

At an "irreducible minimum," the constitutional component

embodied in Article III requires that a plaintiff show: (1)

that he personally has suffered some actual or threatened injury

as a result of the putatively illegal conduct of the defendant;

(2) that the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged action

and; (3) that the injury will likely be redressed by the relief

requested. Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. at 751. See also Valley

Forge Christian College v. Americans United for Separation of

Church and State, 454 U.S. 464, 472 (1982).

Admittedly the constitutional component of the standing

doctrine involves concepts not susceptible of precise definition,

but ideas as to standing have gained considerable definition from

developing case law and have evolved as guiding principles. As

the cases show, the plaintiff must show injury in fact, which is

"distinct and palpable." Gladstone, Realtors v. Village of

Be11wood, 441 U.S. 91, 100 (1979) (quoting Warth, 422 U.S. at

501). The injury cannot be "abstract" or "speculative." City of

Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95, 101-02 (1983). It must be

"fairly" traceable to the action challenged, and likely to be

redressed by a favorable decision. Simon v. Eastern Kentucky

-14-

Welfare Rights Org., 426 U.S. 26, 38. The Supreme Court has

taken note of this case-by-case development:

&

[T]he law of Article III

standing is built on a single basic

idea - the idea of separation of powers.

It is this fact which makes possible the

gradual clarificaiton of the law through

judicial application.

Allen, 468 U.S. at 752.

The prudential component of the standing doctrine

likewise embodies concepts which cannot be precisely defined.

*They also are based on the idea of separation of powers and are

"founded in concern about the proper - and properly limited -

role of the courts in a democratic society." Warth, 422 U.S. at

498. These are the standards applicable to our determination of

the issue of plaintiffs' standing to pursue this litigation.

, 1. Injury

Plaintiffs' basic contention is that defendants have

granted and are continuing to grant federal assistance to

educational institutions and political entities in violation of

the rights of the plaintiffs under various statutes and under the

Fifth Amendment of the Constitution. They assert that this is an

injury separate and apart from the harm inflicted by the

educational institutions in which they are enrolled, or by the

states in which they reside.

The individual Adams plaintiffs, some 40 in all^ reside

in various states and attend a variety of state educational

-15-

institutions. Many of the plaintiffs can be placed in one of the

following categories. (1) Three are students at Virginia State

University (VSU), a predominantly black institution. They

complain of unequal and inadequate facilities, equipment and

programs. VSU is not in accord with the time frames set in our

March 11, 1983 order. (2) Four of the plaintiffs are students

at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville (UAF) , a

traditionally white institution. According to the July 8, 1985

findings by OCR, UAF had failed to reach its black student,

faculty and administrator goals for 1984-85, as required by its

statewide desegregation plan.-*-̂ Defendants have not denied this

allegation. (3) Three of the plaintiffs are students in Dillon

County, South Carolina School District No. 2 (Dillion), who are

enrolled in segregated classrooms. Since 1977, Dillon has been

found by OCR to be in violation of Title VI on three different

occasions. The matter was referred to the Department of Justice

on June 23, 1983, following our order of March 11, 1983. Almost

one year later it was returned by the Department of Justice to

OCR, where it is still "under review." These facts are not

challenged. (4) Five of the plaintiffs are students in Halifax

County, Virginia, alleging racially discriminatory action in

15 See Stipulation of May 28, 1985.

16 Arkansas' performance has not improved. See House Committee

on Government Operations, 100th Cong., 1st Sess., Report on

Failure and Fraud in Civil Rights by the Department of

Education. In this Report, the Committee states that Arkansas

and nine other southern and border states have failed in their

commitments to reduce racial discrimination in their colleges and

universities.

-16-

connection with events which occurred on a County school bus.

OCR investigated the report and issued a letter of finding that

Halifax County had not violated Title VI.

The Adams plaintiffs also assert standing on behalf of

unnamed members of the class certified under our May 7, 1984

order. In response, defendants have submitted a case-by—case

analysis of the status of the individual plaintiffs. Defs.

Memo., Ex. A. They assert that:

defendants' recent discovery efforts

reveal that most of the current plaintiffs

have not filed complaints ..with the Department of Education or the Department

of Labor, or have complaints that are

tolled pending resolution of private

litigation, or do not attend schools

currently undergoing compliance reviews.

In these instances, neither agency action

in general nor the timeframes in particular

have been triggered.

Id. at 2.

Without attempting to challenge the accuracy of the

above assertion, we are satisfied that one or more of the

plaintiffs, in charging racial discrimination against themselves,

have alleged a distinct and palpable personal injury in violation

of their rights under Title VI and the Constitution. This is

more than a case where plaintiffs are asserting the right to have

the government act in accordance with the law or the right to a

particular kind of government conduct. This is also not an

abstract or generalized grievance. Rather, the injury claimed in

the instant case is the right to be educated in a racially

integrated institution or in an environment which is free from

discrimination based on race. As was said in Allen:

-17-

It is in their complaint's second

claim of injury that respondents

allege harm to a concrete, personal

interest that can support standing

in some circumstances. The injury

they identify - their children's

diminished ability to receive an

education in a racially integrated

school - is, beyond any doubt, not

only judicially cognizable, but as

shown by cases from Brown v. Board of

Education to Bob Jones University v.

United States, one of the most

serious injuries recognized in our

legal system. '

468 U.S. at 756. (Citations omitted).

We find no difficulty in holding that plaintiffs have

alleged an injury which is judicially cognizable. We now turn to

consideration of the second prong of the formulation enumerated

in Allen, the requirement of causation.

2. Causation

Plaintiffs claim

to the action or inaction

that their injury is "fairly traceable"

of defendants. As the legislative

history shows, the intent and purpose of Congress in its

enactment of Title VI was twofold:- to prevent the use of federal

funds to support discriminatory practices and to provide

individuals effective protection against such practices. Cannon

17 The court, in Allen, also held that a claim of injury posited

on the "mere fact of government financial aid to discriminatory

private schools" is not judicially cognizable, whether viewed as

a claim to have the government avoid the violation of law alleged

in the complaint or as "a claim of stigmatic injury, or

denigration, suffered by all members of a racial group when the

government discriminates on the basis of race." 468 U.S. at 752,

754.

-18-

v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677, 704 (1979). There is no

doubt but that Congress designed Title VI to put an end to

discrimination in the administration of Federal programs, and

thereby to promote the national policy of non-discrimination.

The same national policy is reflected in the passage of several

statutes following on the heels of Title VI, i.e. , Title VII

(discrimination in employment) and Title IX (discrimination based

on sex). But the above statements of purpose and intent do not

alone solve the problem of whether plaintiffs' injury, which we

hold to be judicially cognizable, is "fairly traceable" to the

challenged conduct of defendants.

It is defendants' basic position that the educational

institutions themselves and the political entities, both state

and local, are "the direct causation of the discrimination of

which plaintiffs complain." Defs. Memo, at 16-17. They claim

that it is the conduct of these independant institutions and

political entities, and not the action or inaction of defendants,

which has caused plaintiffs' injury. Accordingly, they assert

that the causal relationship between defendants' actions and

plaintiffs' injury is too indirect and attenuated to supply the

indispensible link of causation. Defs. Memo, at 20. In addition

to Allen, supra, defendants strongly rely upon two other Supreme

Court decisions, Simon v. Eastern Kentucky Welfare Rights

Organization, 426 U.S. 26 (1976) and Warth v. Seldin, supra. In

each of these cases, the party directly causing the alleged

injury was a third-party, and the participation of the

governmental entity was indirect and tangential. In each case

-19-

standing was denied for lack of causation.

In the instant case, defendants are not charged with

causing injury to plaintiffs directly, but rather indirectly, by

providing financial assistance to educational institutions and

states which engage in discriminatory practices. Defendants are

not charged with a policy of non-enforcement, but rather with

assisting in the unlawful practices of educational institutions

by failing to promptly process complaints and compliance reviews

according to certain time frames, and by failing to proceed

against states which have failed to comply with statewide plans

for the desegegration of institutions of higher education. The

injury of which plaintiffs complain is caused by the conduct of

independent third parties who are not before this court, i.e. the

educational institutions and the states. It is entirely

speculative whether a more rigid enforcement of time frames

governing the administrative processing of complaints or the cut—

off of Title VI funds, the ultimate sanction, would affect the

decisions of these entities or lead to changes in policy. As was

said in Allen, referring to Simon, supra,:

The causal connection [in S imon] depended

on the decisions hospitals would make in

response to withdrawal of tax-exempt

status, and those decisions were sufficiently

uncertain to break the chain of causation

between plaintiffs' injury and the challenged

Government action.

468 U.S. at 759.

Similarly, the decisions of educational and political

institutions in response to the threatened or actual cut-off of

- 20-

funds in this context cannot be predicted with certainty. To

believe that strict enforcement of time frames in the

administrative processing of complaints or of time frames for

compliance with state plans would redress the injury of which

plaintiffs complain, is to indulge in speculation. The

connection between plaintiffs' injury and defendants' action or

inaction is too indirect to provide a proper nexus.

It should not be forgotten that the discriminatory

practices of which plaintiffs' complain existed long before the

passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964., They were not caused by

defendants. They have been continued, and maintained to the

extent they presently exist, not by defendants, but by the

schools and states themselves, where these practices have

unfortunately long been customary. Any effect plaintiffs suffer

as a result of the grant of federal assistance to these separate

and independant entities is similar to the effect of the refusal

to deny Section 501(c)(3) tax exempt status discussed in Allen,

supra. It is indirect, attenuated and speculative. In no sense

is such injury "fairly traceable" to defendants' conduct.

3. Redressability

As is frequently the case, the concepts of causation and

redressability are closely related. This is especially so in the

instant action. Since the injury of which plaintiffs' complain

is not sufficiently linked to the action or inaction of

defendants, it is also speculative to predict that the close

- 21-

monitoring of the day-to-day affairs of two arms of the Executive

Branch, the DE and DOL, would remedy or even attenuate this

injury. The effect of terminating, or threatening to terminate,

federal aid to institutions continuing discriminatory practices,

is even more speculative. This is especially so in the area of

higher education.

a. Higher Education

The most difficult problems in^educational desegregation

exist in the area of higher education. This was recognized long

ago, when the Court of Appeals in Adams I, supra, affirmed the

injunctive relief provided by this court with one single

exception. With regard to institutions of higher education, the

Appeals Court extended the period of compliance with Title VI by

lengthening to 120 days the time within which a state was

*required to submit a plan for eventual desegregation, and, if an

acceptable plan had not been submitted within 180 days, the

initiation of compliance procedures. Adams I, 480 F.2d at 1165.

•The court recognized the problems of integrating higher education

when it noted:

Perhaps the most serious problem in

this area is the lack of state-wide

planning to provide more and better

trained minority group doctors, lawyers,

engineers and other professionals. A

predicate for minority access to quality

post-graduate programs is a viable,

coordinated state-wide higher education

policy that takes into account the

special problems of minority students

and of Black colleges. As amicus points

out, these Black institutions fulfill a

- 2 2 -

crucial need and will continue to play an

important role in Black higher education.

Id. at 1164-65. We stressed this thought in our Second

Supplemental Order of April 1, 1977. Adams v. Califano, 430 F.

Supp. 118 (D.D.C. 1977). That order addressed the failure of

certain southern states to submit acceptable plans for

desegregation, and ordered defendants within 90 days to

promulgate the ingredients of an acceptable higher education

desegregation plan, and within 60 days thereafter to require the

states of Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma,

and Virginia to submit revised plans. Id. At the same time, we

stated:

The process of desegregation must not

place a greater burden on Black

institutions or Black students’ opportunity

to receive a quality public higher education.

The desegregation process should take into

account the unequal status of the Black

colleges and the. real danger that desegre

gation will diminish higher education

opportunitj.es for Blacks. Without suggesting

the answer to this complex problem, it is

the responsibility of HEW to devise criteria

for higher education plans which will take

into account the unique importance of Black

colleges and at the same time comply with the

Congressional mandate.

Id. at 120.

• • • • 1 ftThe lack of integration m higher education remains

despite the passage of more than a decade, and was the focus of

our March 24, 1983 order presently under review. The

explanations are easily found and may be judicially noticed.

First, there is the inherent difficulty of increasing Black

18 See footnote 16.

-23-

enrollment in predominantly white public institutions, stemming

at.least in part from current admissions standards, which many

Blacks, because of inferior secondary education, find difficult

to meet. It is no secret that many of the Black eligibles with

proper academic qualifications are persuaded to attend private

out-of-state institutions offering scholarships and other

financial aid. Extensive recruiting efforts have not been

entirely successful. Second, white enrollment in predominantly

Black institutions has also lagged but for different reasons,

among them the diminished academic quality of these institutions

and their poorer facilities. In order to bring Black

institutions up to equality and make them competitive with white

institutions state legislatures will have to act to supply the

needed funds for the hiring of faculty and the expansion of

physical plant and facilities.

These conditions long antidated the passage of Title VI in

1964 and are conditions over which defendants have no control.

They were not caused by any action of defendants and are not

"fairly traceable" to anything defendants have done or have

failed to do. It is overly sanguine to believe that the

enforcement of time frames or the defendants' ultimate weapon of

cutting off funds will achieve the desired results of substantial

compliance. In the case of Black institutions, in addition to

being ineffective, the effect of cutting off federal funds might

well be devasting. Funding from state and local sources is

already in short supply. The record in this case indicates that

many of the 104 Black colleges would have serious difficulty

-24-

surviving if federal funding were eliminated. The injury of which

plaintiffs complain, particularly in the case of state

institutions of higher learning, is not redressible by the relief

which plaintiffs seek.

b. Local School Districts

The record in the case of local school districts,

composed of elementary and high schools, has been less bleak.

For the fiscal year 1982 through 1984, the OCR received 5,715

complaints and closed 6,477 complaints. Defs. Memo., Statement

of Frederick G. Tate, at 2. However, there is nothing in the

record before us which indicates how these complaints were

resolved and we can only speculate as to the merits of these

complaints, the investigations which took place, the results of

the compliance reviews, whether letters of findings were issued,

and whether the defendants' compliance procedures have been

instrumental in redressing the particular injury plaintiffs have

asserted or will assert in the future. In any case, we find that

the injury of which plaintiffs complain would not be redressible

by the relief which plaintiffs seek, even in this context.

B . Separation of Powers

Finally, in concluding this discussion of plaintiffs'

standing, we repeat again the recent pronouncement of the Supreme

Court that "the law of Article III standing is built on a single

-25-

surviving if federal funding were eliminated. The injury of which

plaintiffs complain, particularly in the case of state

institutions of higher learning, is not redressible by the relief

which plaintiffs seek.

b. Local School Districts

The record in the case of local school districts,

composed of elementary and high schools, has been less bleak.

For the fiscal year 1982 through 1984, the OCR received 5,715

complaints and closed 6,477 complaints. Defs. Memo., Statement

of Frederick G. Tate, at 2. However, there is nothing in the

record before us which indicates how these complaints were

resolved and we can only speculate as to the merits of these

complaints, the investigations which took place, the results of

the compliance reviews, whether letters of findings were issued,

and whether the defendants' compliance procedures have been

instrumental in redressing the particular injury plaintiffs have

asserted or will assert in the future. In any case, we find that

the injury of which plaintiffs complain would not be redressible

by the relief which plaintiffs seek, even in this context.

B . Separation of Powers

Finally, in concluding this discussion of plaintiffs'

standing, we repeat again the recent pronouncement of the Supreme

Court that "the law of Article III standing is built on a single

-25-

basic idea - the idea of separation of powers." Allen, 468 U.S.

at. 752. As a corollary to this concept, the Court referred to

the "well established rule that the government has traditionally

been granted the widest latitude in the 'dispatch of its own

internal affairs.'" Id. at 761. (Citations omitted). It pointed

out that in the Article III context this principle:

...counsels against recognizing standing

in a case brought, not to enforce specific

legal obligations whose violations work a

direct harm, but to seek a restructuring of

the apparatus established>by the Executive

Branch to fulfill its legal duties. The

Constitution, after all, assigns to the

Executive Branch, and not to the Judicial

Branch, the duty to 'take care that the

Laws be faithfully executed.' United

States Constitution, Art. II, § 3. We

could not recognize respondents' standing in

this case without running afoul of that

structural principle.

Id.

On two previous ..occasions, the Court of Appeals has

referred to the scope of our original order as requiring only the

initiation of the enforcement process, gaj^-not the perpetual

supervision of the details of any enforcement program. Adams I,

480 F.2d at 1163 n.5 ("the order merely requires initiation of a

process which ... will then pass beyond the District Court's

continuing control and supervision"); Adams II, 711 F.2d at 165

(D.C. Cir. 1983)("Judge Pratt correctly interpreted the initial

decree not to extend to supervision of the Department's

settlement of its enforcement action against North Carolina").

The orders of March 11, 1983 and March 24, 1983 not only

go well beyond the initiation of the enforcement process, but,

-26-

through the detailed imposition of precise time frames governing

every step in the administrative process, seek to control the way

defendants are to carry out their executive responsibilities.

The fact that the government for the most part consented to these

burdens is of no consequence. More importantly, plaintiffs do

not claim that defendants have abrogated their statutory

responsibilities, but rather that, in carrying them out, they do

not always process complaints, conduct investigations, issue

letters of findings, or conduct compliance reviews as promptly or

expeditiously as plaintiffs would like.' As was said in Laird v.

Tatum, 408 U.S. at 15, and quoted with approval in Allen, 468

U.S. at 760,:

Carried to its logical end, [respondents']

approach would have the federal courts as

virtually continuing monitors of the

wisdom and soundness of Executive action;

such a role is appropriate for Congress

acting through its committees and the 'power of the purse'; it is not the role

of the judiciary, absent actual present

or immediately threatened injury resulting

from unlawful governmental action.

Thus, entirely apart from plaintiffs' failure to meet the

causation and redressability elements of standing, the orders

under review intrude on the functions of the Executive branch and

violate the doctrine of separation of powers, which is the basic

core of standing.

C. Mootness

The jurisdiction of federal courts to review agency

action is dependent on the existence of an actual "case or

-27-

f» O'Shea v. Littleton, 414 U.S. 488/ 493 (1974).controversy.

Our lack of authority to review moot cases stems from the very

same Article III "case or controversy" requirement. DeFunis v.

Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312, 316 (1974).

1. Plaintiffs in WEAL

Plaintiffs' complaint in WEAL seeks, in the form of both

declaratory and injunctive relief, the enforcement of laws

barring sexual discrimination. An amended complaint consisting of

five (5) counts was filed on January 28, 1975.

Count I charges the defendants Secretary of HEW and the

Director of OCR with failure to enforce Executive Order No.

11246, as amended by Executive Order No. 11375. Amended Complaint

30-64. Defendants assert that as of October 8, 1978, the duty

of enforcing these Executive Orders was transferred to the

^ <e.

Department of Labor and therefore that the claims against the HEW

Secretary and its OCR Director are now moot. Defs. Memo, at 28.

Count II charges the DOL and the OFCCP with failure to

enforce these Executive Orders due- to DOL's failure to monitor

and correct deficiencies in HEW's compliance program. Amended

Complaint, 65-69. Defendants assert that the responsibility

for enforcing the Executive Order has since October, 1978 resided

with DOL and therefore that these claims are also moot. Defs.

Memo, at 29.

Count III charges HEW and OFCCP with certain procedural

violations in administering the Executive Order. Amended

-28-

Complaint, 1MI 70-77. Defendants assert that two of the three

individual complainants filed stipulated dismissals in early 1985

and that the third, Elizabeth Farians, no longer has any

complaint pending. Defs. Memo, at 29.

Count IV charges HEW with failure to promulgate final

regulations implementing Title IX of the Education Amendments Act

of 1972. Amended Complaint, M 78-88.- Defendants assert that on

June 4, 1975, the final regulations under Title IX were

promulgated. Defs. Memo, at 30.

Count V charges HEW with failure to enforce Titles VII

and VIII of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. §295h-9

(1970), 42 U.S.C. §298b-2 (1976), by failing to issue final rules

and regulations. Amended Complaint, 1MI 89-95. Defendants respond

that under the Department of Education Organization Act, 20

U.S.C. §3441 (1979), defendant Department of Education

transferred its enforcement responsibilities to the Department of ‘ *

Health and Human Services (HHS), and that HHS is no longer a

party to this litigation. Defs. Memo, at 30.

The WEAL plaintiffs, in a lengthy opposition to

defendants' motion to dismiss, do not meet head on defendants'

claims of mootness; Rather, they cite a long litany of cases

where complaints under Title IX and Executive Order No. 11246

have not been acted upon and compliance reviews have not been

undertaken within the prescribed time frames.

2. Plaintiffs - Intervenors in Adams

-29-

Defendants claim that all of the complaints of the

plaintiff-intervenors in Adams concern HEW's past policy of non

enforcement of Title IX, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of

1973 and Title VI with respect to national origin discrimination

complaints. Accordingly defendants assert that, "since any

policy regarding Title IX, Section 504 and Title VI national

origin discrimination complaints is no longer effective, the

action brought by these intervenors are moot." Defs. Memo, at

32.

A detailed analysis of each of*defendants' claims of

mootness with respect to each of the multitude of matters raised

by the WEAL plaintiffs and the plaintiff-intervenors in Adams is

difficult on the basis of the record before us. In view of our

treatment of the issue of standing, we prefer to avoid this

unnecessary and possibly indecisive exercise and make no

determination concerning defendants' claims of mootness.

Ill. Conclusion

For all of the reasons set forth above, it is our

holding that all of the plaintiffs and intervenors in Adams, as

well as all of the plaintiffs in WEAL, lack standing to continue

this litigation.

-30-

Date:

Accordingly, we grant defendants' motion to dismiss.

JOHN H. P2ATT

United Sleates District Judge

I f JHc

-31-

.PARTIAL CHRONOLOGICAL INDEX OF RELEVANT DECISIONS AND ORDERS

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159

(D.C. Cir. 1973) [Adams I], affirming 356 F.Supp. 92

(D.D.C. 1973)-

Adams v. Weinberger, 391 F.Supp. 269

(D.D.C. 1975) [First Supplemental Order].

Adams v. Califano, 430 F.Supp. 118

(D.D.C. 1977) [Second Supplemental Order]

(Modified unpublished order of March 14, 1975).

Adams v. Califano No. 3095-70

(D.D.C. December 29, 1977) [Consent* Decree]

(basis for March 11, 1983 and March 24, 1983 Orders).

North Carolina v. Department of Education

No. 79-217-CIV-5 (E.D.N.C. July 17, 1981)

(Approved consent settlement between the Department

of Education and the State of North Carolina).

Adams v. Bell, 711 F.2d 161 (D.C. Cir. 1983) [Adams II]

(affirming this court's refusal to enjoin the Department

of Education from entering into a consent settlement with

the State of North Carolina).

Adams v. Bell, No. 30J95-70 (D.D.C. March 11, 1983)

(Order modifying the terms of the 1977 Consent Decree).

Adams v. Bell, No. 3095-70 (D.D.C. March 11, 1983)

(Order denying defendants' motion to vacate the December 29,

1977 Consent Decree).

Adams v. Bell, No. 3095-70 (D.D-.C. March 24, 1983)

(Order modifying 1977 Consent Decree with respect to issues

pertaining to state-wide systems of higher education).