Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1992

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant, 1992. 334c39ac-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/286d9259-8597-4844-bce2-5fd2525cf0e8/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-brief-of-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

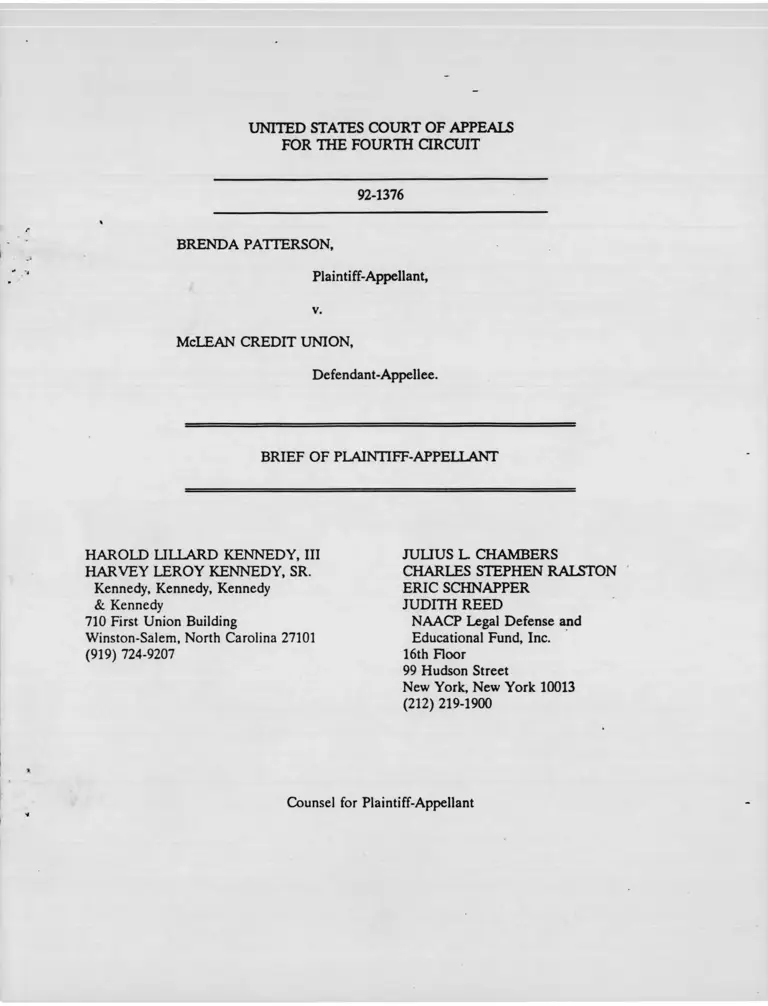

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

92-1376

BRENDA PATTERSON,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

McLEAN CREDIT UNION,

Defendant-Appellee.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

HAROLD LILLARD KENNEDY, III

HARVEY LEROY KENNEDY, SR.

Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy

&. Kennedy

710 First Union Building

Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27101

(919) 724-9207

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

ERIC SCHNAPPER

JUDITH REED

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT OF JU RISD ICTIO N ................................................................................................. 1

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR R EV IEW ............................................................................................ 1

STANDARD OF R E V IE W .................: ........................................................................................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE .......................................................................................................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE FA C TS........................................................................................................ 7

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................................................................................... 11

I. THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1991 REQUIRES REVERSAL OF THE

DISTRICT COURTS DECISION DISMISSING PLAINTIFFS’ SECTION 1981

CLAIMS UNDER PATTERSON V. MCLEAN CREDIT UNION ............................... 12

A. The Plain Language of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 Supports

its Application to a Pending Ca s e ................................................................ 13

1. Statutory Language Providing That The Civil Rights Act of 1991

"Shall Take Effect Upon Enactment" Authorizes Its Application

H e re ............................................................................................................... 14

2. Two Statutory Exceptions to the Rule of Immediate Effect

Underscore the Statute’s Applicability to Pre-Existing

Claims .......................................................................................................... 14

(a) The Section 402(b) Exception for the Pending Case against

Wards Cove Packing Company ....................................................... 15

(b) The Section 109(c) Exception for

Pre-Existing Claims By Americans

Abroad ................................................................................................. 16

B. Recent Action of the United States Supreme Court Suggests

Section 101 of the Act Should Apply ......................................................... 18

II. THE RELEVANT LEGAL PRESUMPTION REQUIRES APPLICATION OF

THE 1991 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT TO THIS C A S E ........................................................ 19

A. Adherence to Bradley v. Richmond School Board in this Circuit . . 19

B. Operation of Bradley in This Case .............................................................. 27

1. Neither the Language Nor the Legislative History

of the Act Precludes Its Application to Pending

C a s e s .......................................................... 7.............................................. 27

2. Application of the Act Here Would Not Create Manifest Injustice . . 30

(a) Nature and Identity of the Parties ...................................................31

(b) Nature of the Rights at S tak e ............................................................ 32

(c) Impact of the Change in L a w ............................................................ 32

III. APPLICATION OF SECTION 101 OF THE 1991 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT IS

PARTICULARLY APPROPRIATE HERE BECAUSE IT RESTORES THE

LAW THAT WAS IN EFFECT AT THE TIME OF THE CHALLENGED

CONDUCT .......................................................................................................................... 33

A. Section 101 Does Not Impose Unanticipated Obligations on

McLean ................................................................................................................ 33

B. Courts Have Generally Applied Restorative Legislation to

Pending Claim s ..................................................................................................... 35

C. Failure to Apply Section 101 Would Create Unnecessary

Inequities and Doctrinal Confusion ........................................................... 36

IV. PATTERSON V. MCLEAN CREDIT UNION SHOULD NOT BE APPUED

RETROACTIVELY AFTER CONGRESS HAS EXPRESSLY REJECTED IT . . . 37

V. THE DISTRICT COURT IMPROPERLY USURPED THE ROLE OF THE

JURY BY MAKING FACTUAL FINDINGS ................................................................ 41

A. This Court’s Recent Interpretations of the "New and D istinct

Relation" Standard Require Careful Assessment of Numerous

Factors ............................................................................................... 41

B. The District Court Disregarded Proper Summary Judgment

Sta n d a r d s .............................................................................................................. 42

CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................................. 46

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Adams v. Brinegar, 521 F.2d 129 (7th Cir. 1975 ).................................................................... 23, 25

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) ............................................................................................................................ 31

Allen v. United States,

542 F.2d 176 (3rd Cir. 1976)............................................................................................................... 23

Alphin v. Henson, 552 F.2d 1033 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 4 )............................................................................ 19

Amen v. City of Dearborn,

718 F.2d 789 (6th Cir. 1983 )............................................................................................................... 40

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson,

456 U.S. 63 (1 9 8 2 )............................................................................................................................... 28

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby,

477 U.S. 202 (1986) ................................................................................................................. 1, 12, 45

Ayers v. Allain, 893 F.2d 732 (5th Cir. 1990), vacated on other grounds,

914 F.2d 676 (5th Cir. 1990) (en banc), cert, granted,

111 S. Ct. 1579 (1991) (sam e)............................................................................................................ 36

Ballog v. Knight Newspapers,

381 Mich. 527, 164 N.W.2d 19 (1969) ....................................................................................... .. 24

Bennett v. New Jersey, 470 U.S. 632 (1985).............................................................................. 21, 26

Bibbs v. Jim Lynch Cadillac, Inc.,

653 F.2d 316 (8th Cir. 1981).................................................................................. 42

Blanchard v. Bergeron, 489 U.S. 87 (1989) ..................................................................................... 28

Boddie v. American Broadcasting Co., Inc., 881 F.2d 267

(6th Cir. 1989), cert, denied, 493 U.S. 1028 (1990)......................................................................... 26

Bonner v. Arizona Dept, of Corrections,

714 F. Supp. 420 (D. Ariz. 1989)........................................................................................................ 36

Bowen v. Georgetown University Hospital, 488 U.S. 204 (1988)..................... '.................... passim

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 414 U.S. 696 (1 9 7 4 )...................................................... passim

Brown v. General Services Administration, 425 U.S. 820 (1976)........................................... 22, 23

iii

Bush v. State Industries, Inc.,

599 F.2d 780 (6th Cir. 1979).............................................................................................................. 24

C.E.K. Indus. Mechanical Contractors v. N.L.R.B.,

921 F.2d. 350 (1st Cir. 1990).............................................................................................................. 26

Campbell v. U.S., 809 F.2d. 563 (9th Cir. 1987)............................................................................. 26

Charbonnages De France v. Smith, 597 F.2d 406 (4th Cir. 1979) ............................................... 44

Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson, 404 U.S. 97 (1971).........................................................................passim

Colautti v. Franklin, 439 U.S. 379 (1979)......................................................................................... 17

Continental Casualty Co. v. DHL Services, 752 F.2d 353 (8th Cir. 1985) ................................. 44

Cooper Stevedoring of Louisiana, Inc. v. Washington,

556 F.2d 268 (5th Cir.), reh’g denied, 560 F.2d 1023 (1977).................................................... 20, 24

Davis v. Michigan Dept, of Treasury,

489 U.S. 803 (1989) ............................................................................................................................ 15

Davis v. Valley Distributing Co., 522 F.2d 827

(9th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 1090 (1975) ......................................................................... 24

Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449 U.S. 250 (1980) ............................................................... 12

DeVargas v. Mason & Hangar-Silas Mason, 911 F.2d 1377

(10th 1990), cert, denied. 111 S. Ct. 799 (1 9 9 1 )............................................................................. 36

Director, Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs,

U.S. Dept, of Labor v. Goudy, 777 F.2d 1122 (6th Cir. 1985)...................................................... 17

Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority,

553 F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1977).............................................................................................................. 23

Edwards v. Boeing Vertol Co., 717 F.2d 761 (3rd Cir. 1983),

vacated on other grounds, 468 U.S. 1201 (1984) ............................................................................. 42

EEOC v. Arabian American Oil Co. &. Aramco Serv. Co.,

499 U .S .__ , 111 S. Ct. 1227 (1991)................................................................................................... 13

Ettinger v. Johnson, 518 F.2d 648 (3rd Cir. 1975) ......................................................................... 23

Bunch v. United States,

548 F.2d 336 (9th Cir. 1977).............................................................................................................. 23

IV

Ferrero v. Associated Materials Inc.,

923 F.2d 1441 (11th Cir. 1991) .......................................................................................................... 21

Fox v. Parker, 626 F.2d 351 (4th Cir. 1980)..................................................................................... 20

Fray v. Omaha World Herald Co.,

58 FEP Cases 786 (8th Cir. 1992 ).................................................................................. 18, 19, 29, 30

French v. Grove Mfg. Co., 656 F.2d 295 (8th Cir. 1 9 8 1 )............................................................. 24

Friel v. Cessna Aircraft Co.,

751 F.2d 1037 (9th Cir. 1 9 8 5 )..................................................................................................... 21, 24

Gaines v. Doughtery County Bd. of Education,

775 F.2d 1565 (11th Cir. 1985) .......................................................................................................... 40

Garment Dist., Inc. v. Belk Stores Services, Inc.,

799 F.2d 905 (4th Cir. 1986 )............................................................................................................... 45

Gersman v. Group Health Ass’n., 60 U.S.L.W. 3519,

112 S.Ct. 960 (Jan. 27, 1992)....................................................................................................... 18, 19

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987)................................................................ 12, 35

Graham v. Bodine Electric Co., 57 FEP Cases

1428, (M.D. 111. Jan. 23, 1991)..................................................................................................... 17, 34

Grove City College v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 (1984).............................................................................. 35

Hallowell v. Commons, 239 U.S. 506 (1916) ................................................................................... 23

Harper-Grace Hospitals v. Schweicker,

691 F.2d 808 (6th Cir. 1982 )............................................................................................................... 14

Harrison v. Associates Corp. of North America,

917 F.2d 195 (5th Cir. 1990 )............................................................................................................... 41

Hastings v. Earth Satellite Corp., 628 F.2d 85 (D.C. Cir.),

cert, denied, 449 U.S. 905 (1 9 8 0 )................................................................................................. 21, 24

Holland v. First America Banks, 60 U.S.L.W. 3577,

112 S.Ct. 1152 (Feb. 24, 1992) ................................................................................................... 18,19

Huntley v. Department of Health, Education and Welfare,

550 F.2d 290 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 985 (1977).............................................................. 23

Federal Deposit Ins. Corp. v. Wright, 942 F.2d 1089 (7th Cir. 1991)...........................................26

v

Hyatt v. Heckler, 757 F.2d 1455 (4th Cir. 1985).......................... 7 ............................................... 20

In the Matter of Reynolds, 726 F.2d 1420 (9th Cir. 1984) ........................................................... 14

James B. Beam Distilling Co. v. Georgia, 111 S. Ct. 2439 (1991) ........................................ passim

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975)...................................................... 12, 26

Jones v. Alfred Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968).............................................................................. 31

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. v. Bonjorno,

494 U.S. 827 (1990) ..................................................................................................................... passim

Kim v. Coppin State College,

662 F.2d 1055 (4th Cir. 1 9 8 1 )............................................................................................................42

Koger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 4 )..............................................................................passim

Kungys v. U.S., 485 U.S. 759 (1988) ................................................................................................ 17

Lahti v. Fosterling, 357 Mich. 578,

99 N.W.2d 490 (1959).......................................................................................................................... 24

Lavespere v. Niagara Mach. & Tool Works, Inc., 910 F.2d 167 (5th Cir.),

reh’g denied, 920 F.2d 259 (5th Cir. 1990) ....................................................................................... 25

Leake v. Long Island Jewish Medical Center, 695 F. Supp. 1414

(S.D.N.Y. 1988), affd, 869 F.2d 130 (2d Cir. 1989) (per curiam )..................................................36

Leland v. Federal Insurance Administrator,

934 F.2d 524 (4th Cir. 1 9 8 9 ).................................................................................................. ........... 25

Lussier v. Dugger, 904 F.2d 661 (11th Cir. 1990)........................................................................... 36

Lust v. Clark Equipment Co., Inc., 792 F.2d 436 (4th Cir. 1986).................................................. 45

Lvtle v. Comm’rs of Election of Union County,

541 F.2d 421 (4th Cir. 1976 )......................................................................................... ..................... 19

Lytle v. Household Manufacturing Co., U. S. (1 9 9 0 )................................................................ 42

Mackey v. Lanier Collections Agency & Serv., Inc., 486 U.S. 825 (1988)................................... 19

Mahroom v. Hook, 563 F.2d 1369 (9th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 436 U.S. 904 (1 9 7 8 )....................................................................................................... 23

Malhotra v. Cotter Co., 885 F.2d 1305 (7th Cir. 1989 ).................................................................. 37

vi

Mallory v. Booth Refrigeration Supply Co. Inc.,

882 F.2d 908 (4th Cir. 1 9 8 9 )............................................................................................................... 41

Marshall v. Sink, 614 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1980).................................................................................. 20

Matsushita Elec. Co. v. Zenith Radio,

475 U.S. 574 (1986) ............................................................................................................................ 43

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) ...................................................................................................................... 12

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) .............................................................................................. 36

Mojica v. Gannett, 779 F. Supp. 94 (N.D. 111. 1 9 9 1 ).......................................................................27

Mozee v. American Commercial Marine Serv. Co.,

1992 U.S. App. LEXIS 9857 (7th Cir. May 7, 1991)................................................................ 18, 27

Mrs. W. v. Tirozzi, 832 F.2d 748 (2d Cir. 1987).............................................................................. 36

New England Power Co. v. United States,

693 F.2d 239 (1st Cir. 1982) ............................................................................................................... 24

Nilson Van & Storage v. Marsh, 755 F.2d 362 (4th Cir. 1985) .................................................... 20

Occidental Chemical v. Int’l Chem. Wrkrs. Union,

853 F.2d 1310 (6th Cir. 1 9 8 8 )............................................................................................................ 35

Dale Baker Oldsmobile, Inc. v. Fiat Motors of N. America,

794 F.2d 213 (6th Cir. 1986 )............................................................................................................... 24

Overseas African Construction Corp. v. McMullen,

500 F.2d 1291 (2d Cir. 1974)............................................................................................................... 25

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989) ................................................ passim

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 729 F. Supp. 35 (M.D.N.C. 1990) .....................................4

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 805 F.2d 1143 (4th Cir. 1986) ............................................3

Patterson v. McLean, 783 F.Supp. 268 (M.D.N.C. 1992) .........................................................passim

Place v. Weinberger, 497 F.2d 412 (6th Cir. 1974),

vacated 426 U.S. 932 (1976) ............................................................................................................... 23

Regan v. Wald, 468 U.S. 222 (1984) ................................................................................................. 28

Revis v. Laird, 627 F.2d 982 (9th Cir. 1980) ................................................................................... 23

Rodriguez v. General Motors, 1990 U.S.App.

LEXIS 8928 (9th Cir, June 6, 1990) ................................................................................................ 42

Rooldedge v. Garwood, 340 Mich. 444,

65 N.W.2d 785 (1954).......................................................................................................................... 24

Rountree v. Fairfax County School Board,

933 F.2d 219 (4th Cir. 1991)....................................................................................................... 41, 43

Russello v. United States, 464 U.S. 16 (1983) ................................................................................ 16

Saltarikos v. Charter Mfg. Co., Inc.,

57 F.E.P. Cases 1225 (E.D. Wise. 1992) ......................................................................................... 34

Samuelson v. Susen,

576 F.2d 546 (3d Cir. 1978) .............................................................................................................. 24

Smith v. Robinson, 468 U.S. 992 (1984)........................................................................................... 36

Sperling v. United States, 515 F.2d 465 (3d Cir.),

cert, denied, 426 U.S. 919 (1975)....................................................................................................... 23

St. Francis College v. A1 Khazraji, 481 U.S. 604 (1987) ................................................................ 12

Stender v. Lucky Stores, 780 F. Supp.

1302, 1303 (N.D. Cal. 1992) .................................................................................................. 13, 17, 34

Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257 (D.C. Cir. 1982) ............................................................. 22, 24

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham,

393 U.S. 268 (1969) ..................................................................................................................... 19, 20

Tyler Business Services, Inc. v. N.L.R.B.,

695 F.2d 73 (4th Cir. 1982)................................................................................................................ 20

United States v. Commonwealth of Virginia,

620 F.2d 1018 (4th Cir. 1980) ............................................................................................................ 20

United States v. Holcomb,

651 F.2d 231 (4th Cir. 1981)................................................................................................ ' ............20

United States v. Kairys, 782 F.2d 1374 (7th Cir.),

cert, denied, 476 U.S. 1153 (1984) ..................................................................................................... 21

United States v. Marengo County Comm'n, 731 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir.),

cert, denied, 469 U.S. 976 (1 9 8 4 )....................................................................................................... 36

United States v. Menasche, 348 U.S. 528 (1955) ........................................................................... 17

viii

United States v. Monsanto Co.,

858 F.2d 160 (4th Cir. 1988)............................................................................................................... 20

United States v. Peppertree Apts.,

942 F.2d 1555 (11th Cir. 1991) ..........................................................................................................26

United States v. Schooner Peggy,

1 Cranch 103, 2 L.Ed 49 (1801) ...................................................................................................... 19

United States v. State of North Carolina,

587 F.2d 625 (4th Cir. 1978 ).............................................................................................................. 20

Vogel v. Cinncinnati, 58 FEP Cases

402 (6th Cir. 1992)............................................................................................................................... 18

Wade v. Orange County Sheriffs Office,

844 F.2d 951 (2nd Cir. 1988)............................................................................................................... 42

Wards Cove Packing Company v. Atonio,

490 U.S. 642 (1989) ............................................................................................................................ 15

Watkins v. Bessemer State Technical College,

1992 U.S.Dist.LEXIS 1296

(N.D. Ala. February 6, 1992) ............................................................................................................ 18

Weahkee v. Powell, 532 F.2d 727 (10th Cir. 1 9 7 6 )......................................................................... 23

Wheeler v. Durham City Bd. of Education,

585 F.2d 618 (4th Cir. 1978 )............................................................................................................ . 19

White v. Federal Express, Corp.,

939 F.2d 157 (4th Cir. 1991 ).............................................................................................................. 41

Womack v. Lynn, 504 F.2d 267 (D.C. Cir. 1974)............................................... ..................... 22, 23

Wright v. Director Federal Emergency Management Agency,

913 F.2d 1566 (11th Cir. 1990) .......................................................................................................... 25

Statutes: Pages:

28 U.S.C. § 1291 ...................................................................................................................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ............................................................................................................................ passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e.................................................................................................................................... 12

Civil Rights Act of 1991 ................................................................................................................ passim

ix

Civil Rights Act of 1991, section 1 0 1 ............................................ ' .........................................passim

Civil Rights Act of 1991, section 1 0 9 ......................................................................................... passim

Civil Rights Act of 1991, subsection 402 .................................................................................. passim

Title VII of Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended 1972 .........................................................passim

Other Authorities: Pages:

136 Cong. Rec. S9331 (daily ed. July 10, 1990) ............................................................................. 33

136 Cong. Rec. S15329 (daily ed. Oct. 16, 1990) ........................................................................... 33

136 Cong. Rec. S16465 (daily ed. Oct. 24, 1990) ........................................................................... 34

136 Cong. Rec. S16571 (daily ed. Oct. 24, 1990) ........................................................................... 33

137 Cong. Rec. S2261 (daily ed. Feb. 22, 1 9 9 1 ).............................................................................. 33

137 Cong. Rec. S77026 (daily ed. June 4, 1991)................................................................................ 33

137 Cong. Rec. S15500 (daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991) ........................................................................... 34

137 Cong. Rec. H9530-31 (daily ed. Nov. 7, 1 9 9 1 ).........................................................................28

137 Cong. Rec. H9549 (daily ed. Nov. 7, 1991) ................................................................................ 28

137 Cong. Rec. S15325 (daily ed. Oct. 29, 1991) ........................................................................... 28

137 Cong. Rec. S15472 (daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991) ........................................................................... 29

137 Cong. Rec. S15478 (daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991) ........................................................................... 29

137 Cong. Rec. S15483-85 (daily ed. Oct. 30, 1991) ...................................................................... 28

137 Cong. Rec. S15954 (daily ed. Nov. 5, 1991)................................................................................15

H.R. Rep. 101-644, pt.2 (101st Cong., 2d Sess. 1990)................................................................... 28

Rule 56, Fed. R. Civ. P.................................................................................................................... 1, 12

S.Rep. 101-315 (101st Cong. 2d Sess. 1990).................................................................................... 28

x

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

On February 18, 1992, the district court for the Middle District of North Carolina,

Winston-Salem Division, entered final judgment, granting defendant’s motion for summary

judgment and dismissing all claims in this action, with respect to all parties. This matter was

before the district court on remand from this Court, with instructions to resolve plaintiffs

remaining claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981. Plaintiff filed a timely notice of appeal on March 17,

1992. This Court has jurisdiction of this appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

This appeal presents four questions relating to the propriety of the district court’s

decision to dismiss Brenda Patterson’s claim that McLean Credit Union discriminatorily denied

her a promotion in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1981:

1. Whether the district court erred in holding that the Civil Rights Act of 1991 by

its terms does not apply to this case.

2. Whether the district court erred in holding that it is manifestly unjust under

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 414 U.S. 696 (1974), to apply the Civil Rights Act of 1991 to

this case.

3. Whether the district court erred in applying the Supreme Court’s now repudiated

decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989).

4. Whether the district court committed independent, reversible error in making its

own factual findings, rather than simply ascertaining whether there is sufficient evidence in the

record that the promotion would have created a "new and distinct relation" between employer

and employee to send that issue to a jury under Rule 56, Fed. R. Civ. P. Anderson v. Liberty

Lobby, 477 U.S. 202, 206 (1986). The district court misread and unjustifiably rejected certain

evidence, weighed evidence, assessed credibility, and made inferences from the evidence. The

district court thus erred as a matter of law in granting summary judgment for defendant.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

The Court must review de novo both the district court’s holding that the Civil Rights Act

of 1991 could not be applied to this case and the grant of summary judgment on the promotion

claim.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Nature of the Case

Brenda Patterson appeals from the district court decision disposing of her claims in this

case. That decision is reported at Patterson v. McLean, 784 F.Supp. 268 (M.D.N.C. 1992) and

set forth in the Joint Appendix to this brief ("JA") at pages 14-32. She seeks reversal of the

district court’s decision that the 1991 Act, does not apply to cases pending on the date of

enactment. She also seeks reversal of the district court’s grant of summary judgment.

Course of Proceedings

Mrs. Patterson filed her complaint against McLean Credit Union on January 25, 1984, in

the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina, alleging that

McLean denied her a promotion, harassed her and discharged her because she is black, all in

violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1981.' She also alleged that she suffered intentional infliction of

mental and emotional distress in violation of North Carolina law.

This case was tried to a jury in November 1985, but the court granted McLean’s motion 1

1 Section 1981 then stated:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right

in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties,

give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for

the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be

subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every

kind, and to no other.

2

for a directed verdict on the harassment claim on the ground that racial harassment is not

prohibited by § 1981. 3 Tr. 75 (III JA 46).2 The district court denied McLean’s motion for

directed verdict on the remaining claims, finding that there was sufficient evidence of racial

animus to send the promotion-denial and discharge claims to the jury. 4 Tr. 125-126 (SA 22-

23).3 Guided by a jury charge to which plaintiff objected, the jury found for McLean on both

the promotion-denial and the discharge claims. 5 Tr. 12-13 (3 JA 143-44).

Mrs. Patterson appealed, contending, first, that the trial court had erred in granting a

directed verdict on the infliction of emotional distress claim and the racial harassment claim,

and second, in incorrectly charging the jury on the promotion-denial claim. This Court

affirmed the decision of the district court. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 805 F.2d 1143 (4th

Cir. 1986), holding, inter alia, that racial harassment is not prohibited by § 1981, id. at 1145.

The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari and affirmed this Court’s holding

that § 1981 does not cover claims of racial harassment. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491

U.S. at 178 (1989). The Court held that whether a promotion claim is cognizable under § 1981,

"depends upon whether the nature of the change in position was such that it involved the

opportunity to enter into a new contract with the employer" rising to the level of a "new and

distinct relation." Id. at 185. The Supreme Court did not apply the "new and distinct relation"

standard to plaintiffs promotion claim, however, ”[b]ecause [McLean had] not argued at any

stage that petitioner’s promotion claim is not cognizable under § 1981." Id. Finally, the

Supreme Court reversed this Court, in part, holding that district court erroneously instructed

2 Citations in the form " _J A __ " refer to the volume of the Joint Appendix filed in first

appeal and the page at which the cited material appears. Citations to "JA __" refer to the Joint

Appendix filed in this instant appeal.

3 Citations in the form "SA___" refer to the page in the Supplemental Appendix, filed in

App. No. 90-1729, at which the cited material appears.

3

the jury on the promotion-denial claim. This Court remanded the § 1981 promotion claim to

the district court. It instructed that "the issue of cognizability of the specific promotion-denial

claim asserted by plaintiff should be considered an open one to be resolved in light of the

Supreme Court’s opinion, whether on the pleadings, or on motion for summary judgment, or by

trial, as the course of further proceedings may warrant." Id. at 485 (citations omitted).

The district court, on remand, sua sponte dismissed her promotion-denial claim without

notifying Mrs. Patterson that the issue of the cognizability of her promotion claim was before

the court, nor giving her an opportunity to brief the issue. The district court determined as a

factual matter, in the absence of any jury findings, that the two positions were not sufficiently

distinct, to satisfy the Supreme Court’s test. See Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 729 F. Supp.

35 (M.D.N.C. 1990) (SA 12).

In an unpublished, per curiam opinion, decided May 3, 1991, this Court held that the

district court’s sua sponte dismissal was error, and that on remand plaintiff should be given the

opportunity to conduct additional discovery on the promotion issue. App. No. 90-1729, slip op.

at 7 (JA 10). This Court concluded that plaintiff should have the "opportunity . . . by the

normal adversarial processes of litigation" to "establish her ‘new contract’ claim." Slip op. at 8

(JA 11). The Court held that the '"nature of the change’ between the position held by

[Patterson] and that to which she was denied ‘promotion’ . . . was a critical threshold element"

of the promotion claim. Slip op. at 5 (JA 8). The Court, while noting that summary judgment

might be an "appropriate device" by which to resolve this issue, "decline[d] to engage in

speculation on how the law . . . might be applied to the evidence." JA 12.

The Opinion Below

Almost immediately following issuance of the mandate, and before any additional

discovery was conducted, McLean filed a motion for summary judgment on the promotion

4

claim. Dkt. Nr. 48. Defendant argued that there was no genuine issue of material fact on the

promotion claim, because the promotion would not have involved the opportunity for plaintiff

to enter into a new contract. After holding a status conference, the district court granted

plaintiffs motion for additional discovery, to be completed within sixty days. Order dated June

13, 1991, Dkt. entry Feb. 11, 1992.

After completion of discovery and following the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of

1991 on November 21, 1991, plaintiff filed her opposition to the motion for summary judgment.

Plaintiff argued, first, that the 1991 Act applies to her case and therefore plaintiffs promotion

claim should be analyzed under the restored standard for determining intentional discrimination

under section 1981. Second, plaintiff argued that the facts demonstrated that the promotion

would have offered her the opportunity to enter into a new and distinct relation with the

Company.

The district court held that the 1991 Act did not apply to Brenda Patterson’s case. The

district court held that the plain language of the statute did not mandate its application and that

the legislative history was not clear. 784 F.Supp. at 274 and n.4 (JA 20). After reviewing

Supreme Court and Fourth Circuit precedent on the issue of retroactivity, the court concluded

that "the current and overarching preference is to preclude such retroactive application." 783

F.Supp. at 278 (JA 24), relying on Bowen v. Georgetown University Hospital, 488 U.S. 204 (1988),

and Justice Scalia’s concurring opinion in Kaiser Aluminum Chemical Corp. v. Bonjomo, 494

U.S. 827, 840-59 (1990). 784 F.Supp. at 279 (JA 25). Finally, the district court held that

application of the 1991 CRA in this case would result in manifest injustice under Bradley v.

Richmond School Board, 416 U.S. 696 (1974) . 784 F.Supp. at 279 (JA 25). In so holding, the

court applied the three-pronged test announced in Bradley.* First, the court held that, although 4

4 See infra, sec. II. B.2.

5

civil rights were involved, the suit was between private parties. 784 F.Supp. at 279 (JA 25).

Second, the court held that the rights of the parties had "matured in the sense that the law of

this case ha[d] already been decided by the Supreme Court." Id. Thus, it would be "unfair" to

"place new legal requirements on the parties." Id. Third, the district court held that application

of the Act would "place new and unanticipated obligations on defendant," because section 1981

had been interpreted as not applicable to plaintiffs case and "[defendant could not have

anticipated that Congress . . . would change" that interpretation. Id.

Having determined that the Act does not apply, the district court went on to hold that

defendant was entitled to summary judgment because the promotion at issue did not present an

opportunity for plaintiff to enter into a "new and distinct relation" with her employer. 784

F.Supp. at 284-285 (JA 30-31).

The district court determined that whether the promotion plaintiff was denied would

have amounted to "an opportunity for a new and distinct relation" between Mrs. Patterson and

McLean — and therefore could still be the basis for a promotion-denial claim -- depended on

myriad factors and that the "Court should look at the changes in the employee’s situation as a

whole and determine if all the changes, individual as well as within the employer’s organization,

work to create a new and distinct relation between the parties." 784 F.Supp. at 284 (JA 30).

The district court then determined as a factual matter, in the absence of any jury findings, that

the two positions were not sufficiently distinct, to satisfy the Supreme Court’s test. 784 F.Supp.

at 285 (JA 31). The district court misread evidence on the salary differential to find that

plaintiffs hourly rate would have increased by only $.89, 784 F.Supp. at 271 (JA 17). Despite

evidence that both persons who held the accountant intermediate job had moved to higher

positions, the district court discredited as "speculation" the potential for upward mobility from

the accountant intermediate job but not from Mrs. Patterson’s clerk position. 784 F.Supp. at

6

285 (JA 31). The court rejected as "ludicrous" the notion that access to specific office

equipment should bear on the nature of the position. 784 F.Supp. at 286 (JA 32). Finally, the

court considered the prospect of increased overtime in the new position as "speculative," in the

absence of a showing by plaintiff that this opportunity was specifically incident to the position.

Id.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Appellant Brenda Patterson, a black woman, was an employee of McLean Credit Union

for 10 years. Although she had been hired as an accounting clerk, Mrs. Patterson worked as a

file clerk and full-time teller for approximately two years, 1 Tr. 26 (1 JA 45), after which she

principally filed and had limited part-time teller responsibilities. 1 Tr. 81 (1 JA 81). In 1976,

after additional filing responsibilities had been imposed on her, Mrs. Patterson relinquished her

part-time teller duties. 1 Tr. 81-82 (1 JA 81-2). Mrs. Patterson worked as file coordinator in

the office from 1976 until the Company laid her off on July 19, 1982. 2 Tr. 7 (1 JA 125).

McLean terminated her employment six months later. 2 Tr. 10 (1 JA 128).

Although she had expressed an interest in an accountant position, Mrs. Patterson was

never promoted from her filing job during her ten years with the Company. 1 Tr. 23, 45 (1 JA

42, 60). A white woman, Susan Williamson, who was hired also as an accounting clerk two

years after Mrs. Patterson, was promoted to the position of accountant intermediate in 1982.

Pltf. Ex. 7 (SA 25).

The formal requirements for the position of accounting clerk are listed in the district

court opinion. 784 F.Supp. at 270 (JA 16). The duties were principally filing and some typing.

In addition, however, to her formal duties, when Mrs. Patterson performed the position of

accounting clerk, there were numerous unwritten duties of the job. For example, Patterson was

required to accept assignments from employees other than her supervisor. 1 Tr. 25, 29-30. In

7

practice, Patterson’s tasks, at various times, included microfilming, photocopying, stuffing

envelopes, sweeping and dusting. 1 Tr. 31; Patterson Dep. 17. Patterson further testified at trial

that in her clerk position she was required to do any "odd job" that needed doing, 1 Tr. 31;

Stevenson testimony 3 Tr. 101. As Patterson described it, even when her filing duties decreased,

other employees "still dumped jobs on" her. 1 Tr. 82-83; 2 Tr. 18. Whenever she was absent

from her job, with one exception in 1978, her tasks piled up awaiting her return, whereas other

employees’ work was kept up to date in their absence by employees remaining on the job. 1 Tr.

37-38, 87. As an accounting clerk she was required to submit to harassment. Patterson testified

that Stevenson "periodically stared at her for several minutes at a time; that he gave her too

many tasks and criticized her in staff meetings while not similarly criticizing white employees."

805 F.2d at 1145. The record leaves no doubt that Patterson’s job -- as an all-round clerk, "girl

Friday," and "gofer" -- was the lowest at the credit union, with the possible exception of janitor.

The accountant intermediate, in contrast, had several different and more responsible

duties, such as accounting, bookkeeping and money management. Deft. Ex. 14 (SA 26). The

formal requirements of that position are listed in the district court opinion. 784 F.Supp. at 270

(JA 16). If Mrs. Patterson had been promoted to accountant intermediate, she would have

moved from her desk located in a vault in the back of McLean and taken on substantial duties

and responsibilities, received substantially higher compensation, pay grade classification, office

equipment, opportunity for overtime work, and she would have had the potential for

advancement to higher level jobs.

Patterson would have received 18 new job duties and responsibilities had she been

promoted to the accountant intermediate job. Ex. 5, Williamson Dep. Ex. 3, Patterson Dep. 37-

40. These would have been substantial changes from the duties that plaintiff had as a file clerk.

Plaintiffs job would have also involved the transfer of monies from the company’s branches to

8

Wachovia Bank in Winston-Salem. Williamson Dep. 37-43. Such money management duties

were handled by only three employees at the credit union: Williamson, Folsom and Braswell.

Williamson Dep. 40. Moreover, the accountant intermediate position was exempt from the

accepting work from anyone but Braswell, and occasionally Stevenson, and they were not

subjected to overly close supervision on a daily basis. Williamson Dep. 29-30. As an accountant

intermediate, Patterson’s work would have been re-assigned during her absence from work.

Williamson Dep. 34. The accountant intermediate was not required to perform the menial tasks

assigned to the accounting clerk when Patterson held that job, nor was Williamson subjected to

harassment by her supervisor. Williamson Dep. 32.

Patterson testified at trial that at the time of the promotion in question her salary was

$8.04 per hour, or $1393.60 per month. 1 Tr. 62; Pltf Exhibit 5. Upon receiving the promotion,

Susan Williamson received $10.00 per hour, or $1733.33 per month. Sandra Folsom, also an

Accountant Intermediate, was making $1,840.81 per month in 1982. JA 56. If plaintiff has

gotten the accountant intermediate job, she could have expected to receive a monthly salary

increase of $300 to $450.5

Not only would the promotion have afforded the opportunity for these significant

immediate changes to her employment situation, but Patterson would have had the opportunity

for job training, Williamson Dep. 43, and to move to higher positions in the future. Susan

Williamson testified that the accountant intermediate permitted her to "progresfs] as the credit

union progressed in services," and that she was "exposed to more in-depth bookkeeping."

Williamson Dep. 24. Sandra Folsom, who held one of the Accountant Intermediate jobs, was

5 Moreover, apart from the base salary, the opportunities for adding to that salary were

more prevalent in the accountant intermediate position. Plaintiff rarely was allowed to work

overtime. (Patterson Dep. 35). When she requested to work overtime on occasions, the

company denied her overtime work. (Id.) Folsom worked overtime and on Saturday when

necessary. (Folsom Dep. 10). So did Williamson. (Williamson Dep. 34-35).

9

promoted to the position of Accountant Senior. Folsom Dep. 8. "Although Williamson was

instructed by her counsel not to answer questions regarding whether she had been promoted to

a higher position, she did testify that she was no longer an accountant intermediate and that she

had not been demoted from that position. Williamson Dep. 6, 7. The promotion would have

offered plaintiff other amenities that she lacked as an accounting clerk. For example, Patterson

did not have a computer terminal, a telephone, or an adding machine in the vault where she

worked. (Patterson Dep. 36-37). Williamson had an adding machine, a telephone and access

to a computer terminal. (Williamson Dep. 36).

The two jobs were so different that defendant’s counsel, in arguing that Mrs. Patterson

was unqualified for promotion to accountant intermediate, even contended that the facts in this

case were analogous to a situation in which T m going to make a decision in my law firm where

I’m going to make an associate a partner, and a paralegal comes to me and says, ‘Mr. Davis, I

should have been trained for that job.’" 3 Tr. 48 (SA 19).

10

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. The plain language of the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which states that it "take effect

upon enactment," requires its application to this case. The Act is thus applicable to pending

cases. Two exemptions to the general rule of immediate application prohibit application of the

1991 Act to certain pre-existing claims; these exemptions make clear that Congress intended

the Act to apply to pre-existing claims which were not explicitly exempted from the statute’s

application.

2. Because the Civil Rights Act of 1991 is restorative legislation, it must be applied to

this case. To fulfill the 1991 Act’s purpose of restoring the legal status quo ante, the Court must

apply the Act here.

3. Even if this Court finds that the language of the statute does not clearly mandate its

application, a well-established legal presumption requires that courts apply current statutory law

to pre-existing claims pending before them. Under Bradley v. Richmond School Bd., 416 U.S.

696, 711 (1974), in the absence of clear language to the contrary a statute must be applied to

pending cases unless such an application creates manifest injustice. No such injustice is created

by application of the Act in this case.

4. If this Court determines that the Civil Rights Act of 1991 does not apply to this case,

remand is nonetheless appropriate since the Supreme Court’s decision in Patterson, should no

longer be applied to plaintiffs’ claims. Plaintiffs’ claims were filed prior to the Supreme Court’s

decision in Patterson. Congress has now repudiated that decision.

5. The district court erred as a matter of law in granting summary judgment to

defendant. The district court misread and unjustifiably rejected certain evidence, weighed

evidence, assessed credibility, and made inferences from the evidence. The court committed

11

independent, reversible error in making its own factual findings,“rather than simply ascertaining

whether there is sufficient evidence in the record that the promotion would have created a "new

and distinct relation" between employer and employee to send that issue to a jury under Federal

Rule of Civil Procedure 56. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, 477 U.S. 202, 206 (1986).

ARGUMENT

I. THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1991 REQUIRES REVERSAL OF THE DISTRICT

COURTS DECISION DISMISSING PLAINTIFFS’ SECTION 1981 CLAIMS UNDER

PATTERSON V. MCLEAN CREDIT UNION

This Court should apply the Civil Rights Act of 1991 to reverse the district court’s

decision and remand plaintiffs’ § 1981 claims for trial before a jury. When the defendants

engaged in the conduct that plaintiff challenges in this case, that conduct was clearly actionable

under § 1981,6 as well as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 1972, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e. The Supreme Court’s narrow interpretation of § 1981 in this case eliminated plaintiffs

accrued claims. Congress on November 21, 1991, thoroughly rejected the Supreme Court’s

construction of § 1981 and confirmed that discrimination in contract relations generally,

including promotion and racial harassment, violates § 1981.7 Under the 1991 Act, there can be

no doubt that plaintiffs’ § 1981 claims are legally viable and should not have been dismissed.

6 See, e.g., Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987); St. Francis College v. A l

Khazraji, 481 U.S. 604 (1987); Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449 U.S. 250 (1980); McDonald v.

Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273, 275 (1976); Johnson v. Railway Express Agency,

421 U.S. 454, 459-60 (1975).

7 Section 101 amends section 1981 to add a subsection (b) which provides as follows:

(b) For purposes of this section, the term "make and enforce contracts" includes the

making, performance, modification, and termination of contracts, and the enjoyment of

all benefits, privileges, terms and conditions of the contractual relationship.

12

A. The Plain Language of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 Supports its

Application to a Pending Case

The plain language of the 1991 Civil Rights Act requires appication of § 101 to this case.

As the Supreme Court recently stated, "[t]he starting point for interpretation of a statute is the

language of the statute itself. Absent a clearly expressed legislative intention to the contrary,

that language must ordinarily be regarded as conclusive." Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. v.

Bonjomo, 494 U.S. 827 (1990).

Three provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 expressly address the applicability of the

Act to pending cases. Section 402 contains two parts -- the general rule requiring immediate

application of the 1991 Act (in subsection 402(a)) and one exception to that rule (in subsection

402(b)):

SECTION 402. EFFECTIVE DATE.

(a) In General. ~ Except as otherwise specifically provided, this Act and the

amendments made by this Act shall take effect upon enactment.

(b) Certain Disparate Impact Cases. -- Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act,

nothing in this Act shall apply to any disparate impact case for which a complaint was

filed before March 1, 1975, and for which an initial decision was rendered after October

30, 1983.

Additionally, section 109 states, in relevant part:

SECTION 109. PROTECTION OF EXTRATERRITORIAL EMPLOYMENT.8

* » *

(c) Application of Amendments. -- The amendments made by this section shall not

apply with respect to conduct occurring before the date of enactment of this Act.

These provisions on their face show that Congress intended the 1991 Act to apply to at least

some pending cases. As one court recently held in Slender v. Lucky Stores, 780 F. Supp. 1302,

1303 (N.D. Cal. 1992), "[t]he language of the Civil Rights Act indicates that the Act should

8 Section 109 extends the protections of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, to

United States citizens working overseas for American companies, and thus overrules the

Supreme Court’s decision in EEOC v. Arabian American Oil Co. &. Aramco Serv. Co., 499 U.S.

___, 111 S. Ct. 1227 (1991).

13

apply to cases which were pending at the time of its enactment."

1. Statutory Language Providing That The Civil Rights Act of 1991 "Shall

Take Effect Upon Enactment" Authorizes Its Application Here

Section 402(a), the general rule for application of the 1991 Act, makes clear that it

applies to plaintiffs’ § 1981 claims. Section 402(a) states explicitly that the Act must "take effect

upon enactment." The changes in the law, therefore, should be construed as effective and

binding on this Court upon the enactment date, which was November 21, 1991.

The district court narrowly construed this phrase to meant that the Act and its

amendments

would be operative on events coming within their scope, but having no effect on

events occurring before that date as the Act was not operative prior to November

21, 1991.

784 F.Supp. at 275. But legislation stating that it takes effect upon enactment is generally

construed to apply to pending claims. For example, language which "specifically provided that

the amendment would be immediately effective" mandated an amendment’s application to a

pending appeal. Harper-Grace Hospitals v. Schweicker, 691 F.2d 808, 811 (6th Cir. 1982). See, In

the Matter o f Reynolds, 726 F.2d 1420, 1423 (9th Cir. 1984) (stating that "the fact that Congress

expressed its intention that the statute take effect upon enactment is some indication that it

believed that application of its provisions was urgent"). Thus, § 402(a), even taken alone,

supports application of the 1991 Act to the pending claims.

2. Two Statutory Exceptions to the Rule of Immediate Effect Underscore the

Statute’s Applicability to Pre-Existing Claims

It is clear that § 402(a) cannot mean that the 1991 Act applies only to post-Act conduct.

Since Congress included express language making only certain sections of the Act inapplicable

to pre-existing claims, it necessarily contemplated that the balance of the law could be applied

to such claims. This Court should construe the statute to give effect to all its provisions,

14

including both the general language requiring immediate effect a”nd the two exceptions to that

rule. The Supreme Court has recently reemphasized this canon of construction in holding that

"the words of the statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the

overall statutory scheme." Davis v. Michigan Dept, o f Treasury, 489 U.S. 803, 809 (1989)

(internal citations and quotations omitted).

Congress created two exceptions to the general mandate that the 1991 Act "take effect

upon enactment." Under these two exceptions, certain provisions of the Act do not apply to

certain pending cases or pre-existing claims: Section 402(b) forbids immediate application of

the Act to a particular pending case, and § 109(c) forbids application of the Act to certain pre

existing claims also not at issue here. The presence of those two exceptions compels the

conclusion that § 101, which is not subject to any such exception, must be applied to pending

cases such as this one.

(a) The Section 402(b) Exception for the Pending Case against Wards

Cove Packing Company

Section 402(b), which excepts "certain disparate impact cases” from the Act, is a special

provision proposed by Alaska Senator Murkowski, who selected the filing and decision dates

referred to in order to ensure that the provision covers only Wards Cove Packing Company v.

Atonio, 490 U.S. 642 (1989), which is now pending on remand. That section excepts Ward’s

Cove Packing Company from the obligation to defend itself under the 1991 Act’s standards.9

The inclusion of this section was necessary only because without it § 402(a) would have applied

to the Ward’s Cove Packing Company.

9 Senator Murkowski sought this provision for Ward’s Cove Packing Co. alone, and he

explicitly said so in seeking support for it. Murkowski assured his colleagues that the Wards

Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio case is the only case that fits the general-sounding description in

402(b). 137 Cong. Rec. S. 15954 (daily ed. Nov. 5, 1991). No similar provision was created to

exempt the defendant in this case from the Act’s standards.

15

i

The importance of § 402(b) in demonstrating that § 402(a) contemplates application of

the Act to pending cases cannot be underestimated. Section 402(a) is an exception to — and

thus necessarily different from -- § 402(a). This difference is underscored by the extreme

importance several members of Congress attached to the passage of § 402(b). When the 1991

Act passed the Senate on October 30, 1991, § 402(b) was inadvertently omitted. Senator Dole

then took the extraordinary step of insisting that the bill be returned to the Senate floor for

further action and a separate vote to add this provision. When the bill was presented for a

second vote, both supporters and opponents of the § 402(b) exemption in the House and Senate

concurred that its effect was to exempt the Wards Cove Company from the 1991 Act standards

in the litigation still pending against it (a result which the supporters lauded and the opponents

decried). This controversy would have been unintelligible if § 402(a) already made the entire

Act inapplicable to pre-existing claims. Section 402(b) was not a redundant provision devised

merely to reassure an over-anxious Company, but an operative term excepting Wards Cove from

the result that otherwise would have occurred: application of the 1991 Act to the case pending

against it. Since this case does not fall within the § 402(b) exception, but comes under the

general § 402(a) rule, the 1991 Act should be applied here.

(b) The Section 109(c) Exception for Pre-Existing Claims By

Americans Abroad

The second exception to § 402(a) further proves the rule of application to pending cases.

Section 109(c) applies only to § 109, a provision of the 1991 Act not applicable here. The

inclusion of this provision makes clear that Congress was fully cognizant of the need to state

explicitly when it did not wish a provision of the statute to apply to cases that were currently

pending before the courts. Had Congress wished to attach a similar caveat to § 101, which

rejected Patterson, it would have done so explicitly. As the Supreme Court has held in Russello

v'. United Stales, 464 U.S. 16 (1983), ”[w]here Congress includes particular language in one

16

section of a statute but omits it in another section of the same Act, it is generally presumed that

Congress acts intentionally and purposely in the disparate inclusion or exclusion." Id. at 23

(citations omitted). Section 402(a) must be interpreted to have a meaning distinct from the §

109(c) and § 402(b) exceptions in order to avoid rendering the exceptions superfluous. Section

402(a) thus necessarily contemplates application of the Act to conduct occurring before the date

of enactment; if it forbade such application, § 109(c)’s directive that § 109 "shall not apply with

respect to conduct occurring before the date of enactment" would be a mere reiteration of a

rule already generally laid down by § 402(a). Similarly, § 402(b), making the Act inapplicable to

a particular pending case, makes no sense unless under § 402(a) the Act does apply to pending

cases.10 As the Supreme Court held in United States v. Menasche, 348 U.S. 528 (1955), "(t)he

cardinal principle of statutory construction is to save and not to destroy. It is our duty to give

effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute, rather than to emasculate an entire

section....” Id. at 538-39 (internal quotations marks and citations omitted); Director, Office o f

Workers’ Compensation Programs, U.S. Dept, o f Labor v. Goudy, 111 F.2d 1122, 1127 (6th Cir.

1985) (following Menasche).11

At the very least, the statute contemplates that the Act may be applied to some non-

10 See, Graham v. Bod in e Electric Co., 57 FEP Cases 1428, 1429 (M.D. 111. Jan. 23, 1991)

(holding that 1991 Act applies to pre-existing claims, in order not "to emasculate these

provisions by making them redundant"); Slender, 780 F. Supp. at 1304 (holding that sections

402(b) and 109(c) would be "meaningless unless the Civil Rights Act applies to cases which were

pending at the time of its enactment").

11 Plaintiff does not, as the district court commented, seek to give the Act some "sort of

‘curious, narrow, hidden sense,”' 784 F.Supp. at 275 (JA 21), but rather to give effect to each of

its provisions. See, Kungys v. United States, 485 U.S. 759, 778 (1988) (Scalia, J.) (holding that

"no provision (of a statute] should be construed to be entirely redundant"); Mackey v. Lanier

Collections Agency & Serv., Inc., 486 U.S. 825, 837 (1988) (stating that "we are hesitant to adopt

an interpretation of a congressional enactment which renders superfluous another portion of the

same law"); Colautti v. Franklin, 439 U.S. 379, 392 (1979) (reading a statute to render a section

"redundant or largely superfluous" violates "the elementary cannon of construction that a statute

should be interpreted so as not to render one part inoperative").

17

exempted pending cases. The three circuit courts which declined-to apply the Act to pending

cases have employed an overly stringent standard of clarity, contrary to the Supreme Court’s

own standard. See, Mozee v. American Commercial Marine Serv. Co., 1992 U.S. App. LEXIS

9857, at *10-*12 (7th Cir. May 7, 1991) ("1991 Act, on its face, does not make clear whether it

should be applied retroactively or prospectively . . ."); Fray v. Omaha World Herald Co., 58 FEP

Cases 786, 791 (8th Cir. 1992) ("effective date section creates . . . ambiguity . . . ."); Vogel v.

Cinncinnati, 58 FEP Cases 402, 404 (6th Cir. 1992) ("Section 402(a)’s language is hopelessly

ambiguous as to the issue of whether Congress intended the 1991 Civil Rights Act to apply

retroactively to pending cases. . . ."). The meaning of the applicability of the 1991 Act is

substantially clearer than the applicability provisions in the statute at issue in Kaiser Aluminum,

which the Court held were clear on their face. Moreover, the circuit court decisions confound

the proper method of statutory construction, elevating legislative history over the statute’s own

text as an indicator of statutory meaning. See, e.g., Fray, 58 FEP Cases at 791.

B. Recent Action of the United States Supreme

Court Suggests Section 101 of the Act Should

Apply

Although the Supreme Court has yet to decide the applicability of the 1991 Civil Rights

Act, its recent actions in vacating and remanding two circuit court decisions for consideration in

light of the 1991 Act indicate that the Court believes that the provisions of the statute may

apply to pending cases. See Gersman v. Group Health Ass'n., 60 U.S.L.W. 3519, 112 S.Ct. 960

(Jan. 27, 1992); Holland v. First America Banks, 60 U.S.L.W. 3577, 112 S.Ct. 1152 (Feb, 24,

1992), now pending in this Court. The Courts of Appeals in both Gersman and Holland - like

the district court in this case — had applied the Supreme Court’s decision in this case to

plaintiffs’ § 1981 claims. As one court recently remarked, in Watkins v. Bessemer State Technical

College, 1992 U.S.Dist.LEXIS 1296 (N.D. Ala. February 6, 1992),

18

This court can conceive of no reason for the Supreme Court to vacate and

remand Gersman unless the Supreme Court believes, as does this court, that the

Act effectively eliminates the effect of Patterson, even in cases which preceded

the Act.

Holland supports the same conclusion. If the Act did not apply, the Circuit courts’ failure to

address the effect of § 101 of the Civil Rights Act to a pending case would not require that

those decisions be vacated and remanded.

II. THE RELEVANT LEGAL PRESUMPTION REQUIRES APPLICATION OF THE

1991 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT TO THIS CASE

Even if this Court were to find that the statute on its face does not expressly authorize

its application to pending cases, governing Supreme Court precedent establishes a presumption

that new legislation so applies. The Supreme Court, in its unanimous opinion in Bradley v.

Richmond School Board, held that

a court is to apply the law in effect at the time it renders its decision, unless

doing so would result in manifest injustice or there is statutory direction or

legislative history to the contrary.

416 U.S. 696, 711 (1974).12 As the Bradley Court noted, this presumption has a long history,

dating back to the 19th century. Id., at 711-15, citing, United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch

103, 2 L.Ed 49 (1801); Thorpe v. Housing Authority o f Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969).

A. Adherence to Bradley v. Richmond School Board in this Circuit

For almost twenty years this Court has consistently applied the Bradley standard to apply

new legislation to claims arising before the enactment of that legislation.13 The district court in

u Bradley applied the 1972 Emergency School Aid Act, which provided for attorney’s fees

for school desegregation litigation, to attorney time spent on the case in earlier years.

13 Roger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702, 704-06 (4th Cir. 1974) (1972 amendment to Title VII);

United States v. Monsanto Co., 858 F.2d 160, 175-76 (4th Cir. 1988) (amendment to

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act); Lytle v. Comm’rs o f

Election of Union County, 541 F.2d 421, 424, 427 (4th Cir. 1976) (1975 amendment to Voting

Rights Act); Alphin v. Henson, 552 F.2d 1033, 1034-35 (4th Cir. 1974) (Hart-Scott-Rodino

Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976); Wheeler v. Durham City Bd. o f Education, 585 F.2d 618,

19

this case selected the correct standard in its reliance on Bradley. "McLean urged the court to

adopt a presumption against retroactivity. Such a presumption, however, applies only where

where substantive rights and liabilities are changed. That presumption derives from Bowen v.

Georgetown Univ. Hosp., 488 U.S. 204, 208-9 (1988). Dictum in Kaiser Aluminum v. Bonjomo

described that case as in "apparent tension" with Bradley. 110 S.Ct. at 1572 (plurality opinion by

O’Connor, J., concurred in by Scalia, J.). Four justices found the tension "more apparent than

real," Id. at 1591. The Bradley and Bowen lines of cases had been discussed simultaneously by

the Supreme Court in Bennett v. New Jersey, however, and reconciled as follows:

Bradley ... expressly acknowledged limits on [the principle of retrospective

operation.] T h e Court has refused to apply an intervening change to a pending

action where it has concluded that to do so would infringe upon or deprive a

person of a right that had matured or become unconditional".... This limitation

comports with another venerable rule of statutory interpretation, i.e. that statutes

affecting substantive rights and liabilities are presumed to have prospective effect.

470 U.S. 632, 639 (1985) (emphasis added) (internal citations omitted).

This course is particularly appropriate when the legislation is remedial or procedural in

nature rather than affecting substantive rights. The presumption in favor of application is

consistent with the principle that remedial measures are to be liberally construed. Cooper

Stevedoring o f Louisiana, Inc. v. Washington, 556 F.2d 268, 272 (5th Cir.), reh’g denied, 560 F.2d

1023 (1977). A remedial statute is one that "relates to the means and procedures for

621 (4th Cir. 1978) (20 U.S.C. §1617); United States v. Slate o f North Carolina, 587 F.2d 625, 626

(4th Cir. 1978) (Executive branch reorganization approval by Congress); Marshall v. Sink, 614

F.2d 37, 38 n. 1 (4th Cir. 1980) (Federal Mine Safety and Health Amendment Act of 1977);

United Stales v. Commonwealth o f Virginia, 620 F.2d 1018, 1022 (4th Cir. 1980) (Executive

reorganization approved by Congress); Fox v. Parker, 626 F.2d 351, 353 (4th Cir. 1980) (Civil

Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976); United States v. Holcomb, 651 F.2d 231, 234 (4th

Cir. 1981) (Horse Protection Act Amendments of 1976); Tyler Business Services, Inc. v. N.L.R.B.,

695 F.2d 73, 77 (4th Cir. 1982) (Equal Access to Justice Act); Nilson Van & Storage v. Marsh,

755 F.2d 362, 364-66 (4th Cir. 1985) (Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984); Hyatt v.

Heckler, 757 F.2d 1455, 1458-59 (4th Cir. 1985) (Social Security Disability Benefits Reform Act

of 1984).

20

enforcement of [existing] rights". United Slates v. Kairys, 782 F.2d 1374, 1381 (7th Cir.), cert.

denied, 476 U.S. 1153 (1984). The group of statutes to which this presumption applies are

referred to interchangeably as remedial, procedural, or both. See, e.g., Ferrero v. Associated

Materials Inc., 923 F.2d 1441, 1445 (11th Cir. 1991) (remedial and procedural laws referred to

"as a matter of convenience" as procedural). Recognition of this presumption regarding

procedural and remedial legislation is widespread.14 Application to pending claims of new

enforcement mechanisms rarely involves any risk of serious unfairness.

Retroactive modification of remedies normally harbors much less potential for

mischief than retroactive changes in the principles of liability.... Modification of

remedy merely adjusts the extent, or method of enforcement, of liability in

instances in which the possibility of liability previously was known.

Hastings v. Earth Satellite Corp., 628 F.2d 85, 93 (D.C. Cir. 1980).15

The most noteworthy instance in which the courts applied this distinction between

conduct-regulating and remedial law concerned the 1972 amendments to Title VII. Prior to

1972 Title VII did not apply to federal employees. Section 717 of the 1972 legislation forbad

federal agencies to discriminate on the basis of race, etc., and authorized victims of such

discrimination to bring suit in federal court for back pay, injunctive relief, and counsel fees.

The 1972 amendment was widely interpreted to apply to acts of discrimination occurring prior

to the effective date of the statute. The courts reasoned that although Title VII itself did not

forbid federal employment discrimination prior to March 24, 1972, such discrimination had in

fact been illegal before 1972 under the Constitution, an earlier statute and several executive

orders. Thus Title VII did not declare illegal previously lawful conduct; rather, it provided new

14 This presumption was recognized in at least eight circuits. See Appendix to this brief.

15 See also Friel v. Cessna Aircraft Co., 751 F.2d 1037, 1039 (9th Cir. 1985) ("danger" of

rendering unlawful conduct lawful when engaged in "is not present where statutes merely affect

remedies or procedures").

21

remedies and enforcement machinery to redress conduct that had been unlawful under other

provisions long prior to 1972. Thus, even though, prior to 1972 "it was doubtful that backpay"

could be awarded by the courts to victims of federal employment discrimination, Brown v.

General Services Administration, 425 U.S. 820, 826 (1976), the Title VII amendments expressly

authorizing that remedy were applied to pre-Act claims.

As this Court explained:

[T]he 1972 Act did not create a new substantive right for federal employees. The

constitution, statutes and executive orders previously granted them the right to

work without racial discrimination. Section 717(c) simply created a new remedy

for the enforcement of this existing right.... The Act provided Koger with a

supplemental remedy .... [A] federal employee’s right to be free from racial

discrimination existed before the passage of the 1972 Act. If it includes — as it

should -- a new remedy to enforce an existing right, then under the general rule

favoring retrospective application of procedural statutes, §717(c) should be

applied to pending cases ....

Koger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702, 705-07 (4th Cir. 1974). The District of Columbia Circuit endorsed

the reasoning in Koger.

Section 717(c) is merely a procedural statute that affects the remedies available to

federal employees suffering from employment discrimination. Their right to be

free of such discrimination has been assured for years.

Womack v. Lynn, 504 F.2d 267, 269 (D.C. Cir. 1974) (Emphasis in original).16 The Third

Circuit concurred:

Congress did not need to create new substantive rights for federal employees

when it enacted §717. Rather, ... this provision was designed only to make