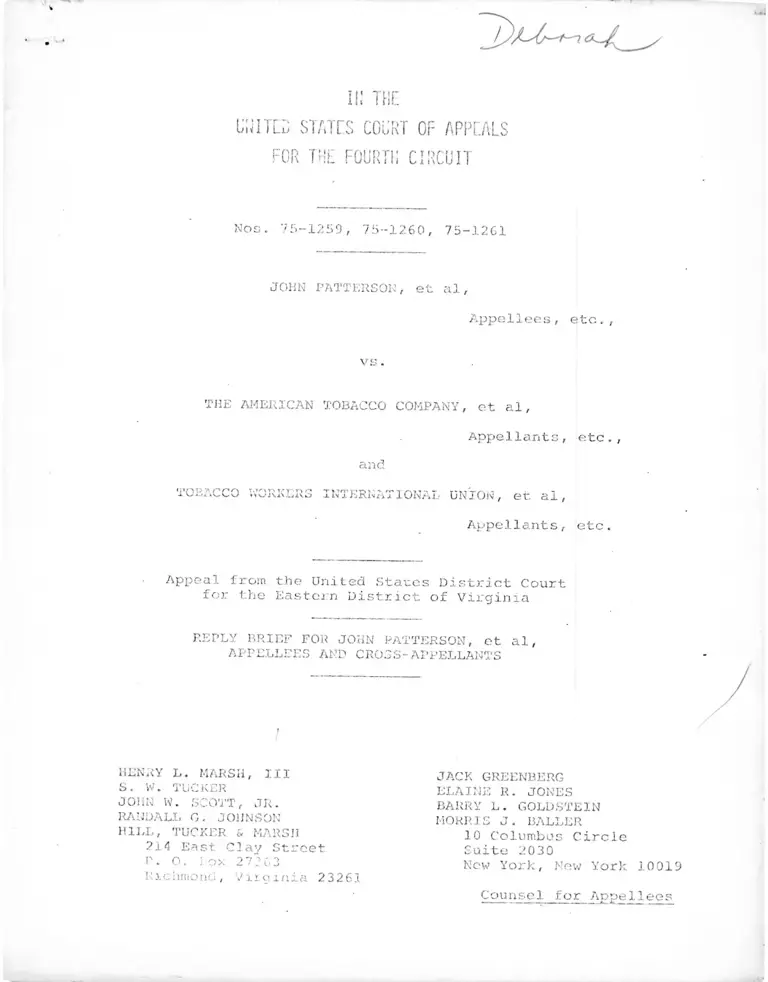

Patterson v. The American Tobacco Company Reply Brief for Appellees and Cross-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. The American Tobacco Company Reply Brief for Appellees and Cross-Appellants, 1975. 4b2653dd-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/28990c3e-1a2f-40af-b064-2d8b6834e38c/patterson-v-the-american-tobacco-company-reply-brief-for-appellees-and-cross-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

II! THE

Uh ITlI; states court of appeals

FOR THE l JURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 75-1259, 75-1260, 75-1261

JOHN PATTERSON, et al,

Appellees, etc.,

vs.

THE AMERICAN TOBACCO COMPANY, et al,

Appellants, etc.,

and

. .ivnAiuui j.Hx>,KWiU iOwAj.' UNION, et al,

Appellants, etc.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia

REPLY BRIEF FOR JOHN PATTERSON, et al,

APPELLEES AND CROSS-APPELLANTS

;I

HENRY L. MARSH, III

S. W. TUCKER

JOHN W. SCOTT, JR.

RANDALL G. JOHNSON

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

r. O. Box 27363

Richmond, Virginia 23261

JACK GREENBERG

ELAINE R. JONES

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CITATIONS ---------------------------------------- iii

INTRODUCTION --- 1

ARGUMENT -------------------------------------- 2

Page

I. American's Argument That The District Court

Lacked Jurisdiction Of Patterson Is

Meritless ----------------- 1---------------

II. The Facts Of The Instant Case Clearly Support

The District Court's Finding That American

Discriminates In The Selection of Supervisory

Personnel ------ 4

A. American Failed To Rebut Plaintiffs' Proof

Of Discrimination In Selection of

Supervisors ----------------------------------- 4

B. American Failed To Show The District Court's

Remedy Improper ------------------------------- 7

ill. The District Court Appropriately Fashioned An

Immediate Posting and Bidding Procedure Designed

Finally To Terminate The Discriminatory Effects

Of The Past Segregated Employment System --------- 8

A. The Relief Granted Finds Support In Title

VII And Its Legislative History--•------------ 9

B. Nothing In Title VII Or Its Legislative

History Restricts The District Court In

Fashioning Relief ---------------------------- 14

C. The Early Decisions Do Not Preclude Relief

As Granted In The Instant Case ---------------- 17

D. The Specific Relief Granted Is Required

By The Law And The Evidence------------------ 21

E. Equitable Considerations Support Red

Circling-------------------------------------- 2 6

IV. The Defendant Company's Statistical Evidence

Demonstrates That Blacks Are Still "Locked In"

To The Lower Paying Positions At The Branch

Plants -------------------------------------------- 28

11

TAELE OF CONTENTS

(Continued)

V. The EEOC's Approval Of The Establishment Of

"Lines of Progression" Has No Bearing On The

Decision Of The District Court -------------------- 31

VI. The District Court Correctly Ordered "inter

Branch Transfer Rights Based On Company-

Wide Seniority" To Insure Adequate Relief

For All Members Of The Class --------------- ---..- 33

A. The Richmond And Virginia Branches Must

Be Considered As A Single Facility If

Meaningful Relief Is To Be Provided For

All Cl ass Members -------------- ■-------------- 33

B. Section 703(h) of Title VII Is Not Appli

cable To The Case At. Bar ---------------------- 35

VII. The District Court Properly Found That The

TWIN Was Liable For The Unlawful Employment

Practices At The Company -------------------------- 36

VIII. The Five-Year Statute Of Limitations Controls

The §1981 Action--------------------------------- 39

CONCLUSION ------------------------------------------------ 4 2

Ill

TABLIJ OF CI TAT I OKS

Pago

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(197 4 ) ------------------------------------- 21

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19 (1969)------------------------ 25

Allen v. Gifford, 462 F.2d 61s (4th Cir. 1972)- 39,40

Almond v. Kent, 459 F.2d 200 (4th Cir. 1972) -- 40,41

Austin v. Reynolds Metals Co., 327 F.Supp. 1145

(E.D. Va. 1970) ---------------------------- 3

Barnes Coal Corp. v. Retail Coal Merchant's

Assn., 123 F . 2d 645 (4th Cir. 1942) ------- ' 40,41

Boston Chapter N.A.A.C.P., Inc. v. Beecher,

504 F . 2d 1017 (1st Cir. 1974) ------------- 3

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) ------------------------------------- 20

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

457 F .2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 982 (1972) ---------- ------------- 4,21

Bush v. Lone Star Steel Company, 37-3 F.Supp.

526 (E.D. Tex. 1974) ----------------------- 14

Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., 500 F .2d 1372

(5th Cir. 1974) -------- 36

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania

v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd

Cir. 1971), cert. denied, 404 U.S. 854

(1971) -------- 7

Cox v. United States Gypsum Co., 409 F.2d 289

(7th Cir. 1969)--:------------------------- 3.

Fagan v. National Cash Register Co., 481 F .2d•

'1115 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ----------------------- 31

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F .2d

398 (5th Cir. 1974), cert.. granted, 43

U.S.L.VJ.__(1975) — ■------- ----— ---------- 16,27

Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) --------------- 14,18,21,25,27

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424

"(1971) ------------------- 5,7

Grimm v. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 300 F.

Supp. 984 (N.D. Cal. 1969) ------------------ 31

Jersey Central Power £ Light Co. v. Local 327,

I LEW, 508 F. 2d 687 (3rd Cir. 1 975) -------- 27

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire £ Rubber Company, 491

F . 2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974 ) ----------------- 36

Jurinko v. Edwin E. Wiegand Co., 477 F .2d 1033,

vacated and remanded on other grounds, 414

U.S. 970 (1973) , reinstated,' 497 F.2cl 403

(3rd Cir. 1974 ) --- 27

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 301 F.Supp. 97 (M.D.

h'.C. 1909), aff'd in part, 4 38 F. 2d 8 6

(4th Cir. 1971) -----— — ------------------- 35

. M

TABLE OF CITATIONS

(Continued)

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 411 U.S. 1S2 (19 7 3) ------- 26

Local 53 of International Ass'n. of Heat &

Fros-t I. & A. Workers v. Vogler, 4 07 F . 2d

1047 (5th Cir. 1 969) ------ 35

Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers

v. United States, 416 F. 2d 980 (5 th Cir.

1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)-- 16,17,10,19,2.1,

22,23,31

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145

(1965) ------------------------------------- 14

Macklin v., Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478

F . 2d 979 (D.C. Cir. 1973)--- -------------- 3,2.1,36

Meadows v. Ford Motor Co., 510 F . 2d 93-9 (6th

Cir. 197.5) -------------------------------- 27

Myers v. Gilman Paper Corp., 9 EPD f,j9 9 2 0

(S.D. Ga. 1975) ----- 38

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 313 U.S. 177

(1941) -------------------- 16,17

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp.

5 05 (l',.D. Va. 19 68) ---------------- ------- 17,18,19,21,22,

2 3

Revere v, Tidewater Telephone Company, 6 EPD

118961 (4th Cir. 1973) ----------- 40

Robinson v. Lorillard Corporation, 444 F.2d

791 (4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed, 404

U.S. 1006 (1971) ------ —--- --------------- 5,10,36

Rock v. Norfolk and Western Railway Co., 473

F .2d 134 4 (4th Cir. 1973), ccrt. denied,

411 U.S. 939 (197 3) -------- ---— — — ---- 10

Rogers v. Internationa], Paper Co., F. 2d

__ , 9 EPD 119865 (8th Cir. 1975)"----------- ' 5,23

Sabalu v. Western Gillette Inc., 362 F.Supp.

1142 (S.D. Tex. 1973) ---------------------- 38

Sprogis v. United Air Lines, Inc., 444 F.2d

1194 (7th Cir. 1971), cert. den., 404 U.S.

991 (1971) ---------- — ------- ------------ 31

Swann v. Chariotte-llecklenburcj Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) -------------- 14,25,26

Taylor v. Armco Steel Corp., 8 EPD 1(9550 (S.D.

Tex. 19 7 3) --------------------------------- 8

Terrell v. U.S. Pipe and Foundry Corp.,

7 EPD 119055 (H.D. Ala. 1973) --- ----------- 38

Tillman v. West-Haven Recreation Association,

Inc., ___ F.2d __ (4th Cir. 1975), decided

April 15, 1975, No. 14,9 57 ---------------- 24

Tippett v. Liggett & Myers Tobacco Co., 316

F.Supp. 292" (M.D. N.C. .1970)-------------- 3

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446

F . 2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971)

iv

Pago

22

« 4fa

TABLE Or CITATIONS

(Continued)

United States v. Dillon Supply Co., 429 F .2d

BOO (4th Cir. 1970) --------------------- 5

United States v. Hayes International Corp.,

■ 4 56 F . 2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972) -------------- 22

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company,

45.1 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert. denied,

406 U.S. 906 (1972) ------------ 22,35

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers

International Ass'n., Local 36, 416 F .2d

123 (8th Cir. 1969) -----------------------

United States v. United States Steel

Corporation, 371 F.Supp. 1045 (N.D. Ala.

1973) -------------- -----------------------

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 502 F .2d 1309

(7th Cir. 1974) ... — ---------------------

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) -------

Westover Court Corp. v. Lley, 185 Va. 718

(1946) ------- -----------------------------

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F .2d

1201 (1972), cert, den., 411 U.S. 931 (1973)

Worrie v. Boze, 198 Va. 533 (1956)--:--------

V

Page

14,22

27

25

4 0,4 .1

22

41

Statutes

United States Code:

42 U.S.C. §1981 -------------------- -- ---- 3,4,7,21,37

42 U.S.C. §198 3 ---------------------------- 39,4 0

42 U.S.C. §2000e (Title VII) -------------- 11

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (a) --------------------- ' 10

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(c) --------------------- 11,39

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) --------------------- 35

42 U.S.C. §2000o-2(j) --------------------- 7

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(q) --------------------- 11

42 U.S.C. §2 00Oe-5(j) --------------------- 11

42 U.S.C. §2000o-12(b) --------------------- 31

29 U.S.C. §160 (c) ------------------------- 13

86 Stat. 103 ---------------------- 11

Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended:

■ §8-24 ----- 39

r«T

ii

TABLE OF CITATIONS

(Continued)

vi

Pane

Law Reviews

Gould, Employment Security, Seniority and Race:

The Role of 'i'it.1 e VII of_ the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 , 13 Howard L.J. 1 (1967) ------ 2 3

Note, Title VII, Seniority Discrimination, and

the Incumbent Negro, BO Harv. L. Rev. 1260

(1967) ---------------------------- 16,17,19,23,27

Otlier Authorities

110 Cong. Rec. 7213 (1964) 15

118 Cong. Rec. 4972 (1972) -------------------- 12

118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972) 11

29 C.F.R. §1601.30 31

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 75-1259, 75-1260, 75-1261

JOHN PATTERSON, et al,

Appellees, etc.,

vs.

THE AMERICAN TOBACCO COMPANY, et al,

Appellants, etc.,

and

TOBACCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, et al,

Appellants, etc.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia

REPLY BRIEF FOR JOHN PATTERSON, et al,

APPELLEES AND CROSS-APPELLANTS

INTRODUCTION

Neither the Company nor the Unions attempt to refute

the plaintiffs' extensive presentation of the basic facts which

support the district court's findings of liability. Instead, they

suggest that certain inferences might be drawn from selected

factual assertions. In this reply brief, plaintiffs will respond

to these contentions.

2

With respect to the district court's finding that the

promotional practices arc racially discriminatory, the defendants

argue that the introduction of the posting and bidding system

in 1968 satisfied their responsibilities under the Act. With

respect to the finding of discrimination in the selection oi.

supervisory personnel, they merely say that they are in line

with other employers in the Richmond metropolitan area.

The defendants contend that, in ordering the only

relief which can overcome the continuing effects of prior dis

crimination in this case, the district court disregarded inhibi

tions which they read into the statute as previously construed

by the courts. It is the position of the plaintiffs that the

district'court correctly found that, without the relief which it

fashioned, the defendant's promotional system would continue to

freeze black employees into discriminatory patterns that existed

before the Act and that, accordingly, such relief is mandated

by the statute.

I

AMERICAN'S ARGUMENT THAT THE DISTRICT COURT

LACKED JURISDICTION OF PATTERSON IS MERITLESS

American somewhat imaginatively argues that the district

court erred in failing to dismiss the Patterson case on the

ground that the plaintiffs' January 3, 1969 EEOC charges were

not timely filed (Co. Hr. at 40-41). This argument is erroneous

in fact and liiw.

Factually, American's argument is premised on the

assertion that all discrimination ended by January 15, 1968

3

(Co. Dr. at 41). That assertion is wrong. As the district court

held (Mem. Op. at 6-7, 8-9) and as plaintiffs have exhaustively

shown (PI. Br. at 16-21), discrimination continued by reason of

the use of departmental preferences on temporary vacancies, pro

tected jobs, lines of progression, and the prohibition on inter

plant transfers.

But even if ail discrimination had ended in 1968,

American's position could not prevail. The nature of the pre-

1968 discrimination shown by plaintiffs was continuing, as the

district court found (Mem. Op. at 6-7). The abandonment of

certain of those practices in 1968, without implementation of

affirmative action to eliminate' the continuing effects of past

discrimination, could not suddenly cut off the plaintiffs' right

1/ 'of action. Cox v. United States Gypsum Co., 409 F.2d 289, 290

(7th Cir. 1969); Mack1in v. Speckor Freight Systems, Inc., 478

F. 2d 979 , 986-7 (D.C. Cir. 1973); Austin v. Reynolds Me t a1s

Co., 327 F.Supp. 1145, 1152 (E.D. Va. 1970); Tippett v. Liggett

k Hyers Tobacco Co. , 316 F.Supp. 292, 29 6 (M.D. N.C. 1970) .

Moreover, plaintiffs' case was properly before the

court under 42 U.S.C. §1981 regardless of the timeliness of EEOC

charges. American concedes that the first charge was filed less

than one year after the January 15, 1968 elimination of some of

its discriminatory practices (Co. Br. at 41). Plaintiffs hatve

argued that the filing of the EEOC charge tolled the running of

1/Plaintiffs' .1969 EEOC charges alleged continuing

practices of discrimination (App. 36).

4

the statute of limitations applicable to the §1981 claim (PI. Br.

at 62-64). Unless this Court rules against plaintiffs on

that contention, the filing of this action under 42 U.S.C. §1981.

was within the applicable statute of limitations.

II

THE FACTS OF THE INSTANT CASE CLEARLY SUPPORT

THE DISTRICT COURT'S FINDING THAT AMERICAN DISCRIMINATES

IN THE SELECTION OF SUPERVISORY PERSONNEL

A. American Failed To Rebut Plaintiffs' Proof

Of Discriinination In Se] ection Of Supervisors.

American's argument against the district court's

2/

finding of discrimination in supervisory selection completely

omits discussion of most of the relevant facts on which that

finding rests. Instead, the Company dwells solely on statistical

indicia of discrimination and exclusively on post-1965 vacancies.

This Court must refuse this invitation to put on blinders. Upon

the whole record, the finding of discrimination should be affirmed.

American's analysis of a ciise " lw] here a finding of

discrimination is predicated purely on statistics" (Co. Br. at 42)

is misdirected here. Plaintiffs proved, and the district court

found, that American's selection process was racially discrimi

natory in nature as well as effect. Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing

Machine Co. 457 F.2d 1377, 1382-1383 (4th Cir. 1972), cert denied

409 U.S. 982 (1972), (see plaintiffs' brief at 21-23,

2/

The union defendants do not address this issue, claim

ing to be uninvolved. See, e.g^, Brief of Local 182 in Patterson

at pp. 5-6. But of. the district court's specific finding of

local union participation in supervisory selection, Stip. 1,

No. 56, App. 52.

49-50). American's temporal restriction of its statistical

analysis to post-1965 vacancies is similarly unfounded. Title

VII reaches not only renewed practices of post-1965 discrimina

tion, but also facially neutral practices that perpetuate the

effects of pre-1965 discrimination. Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424, 429 (1971); United States v. Dillon Supply Co.,

429 F.2d BOO, 803-4 (4th Cir. 1970); Robinson v. Lori Hard

Corja. , 4 4 4 F. 2d 7 91, 7 9 5-6 (4 th Cir. 1971), cor t dismissed, 404

U.S. 1006 (1971)? Rogers v. International Paper Co.,

F.2d 9 EPD 119^65 (8th Cir. 1975) at p. 6590. Therefore,

the mere promotion of 8 Blacks out of 27 new supervisors since

1965 at the Richmond and Virginia Branches does not suffice to

satisfy American's legal duty to eliminate the vestiges of its

past discrimination. Moreover, the record shows that American's

hiring percentages began to improve not with the passage of Title

VII, but only with the filing of EEOC charges of discrimination'

4/

some four years later. American's simplistic justification of

its post-1965 practices would have the court ignore the Company's

responsibility for the continuing effects of its earlier policy

3/

3/

American implies that the record fails to show racial

exclusion because no individual testified that he or she sought

and was denied a position (Br. at 42 n. *). That contention is

inapplicable to this case since /American provided no way for

interested employees to apply for supervisory positions (Stip. I,

No. 58, App. 53.

1/On May ]6, 1969, only 4% of the supervisors at

Virginia Branch were black; at Richmond Branch, American had only

a single black supervisor until 1971; and there lias never been a

black supervisor at Richmond Office (see Pi. Br. at 23). More

over, even after this suit was filed in 3973, American had only

promoted one Black in any of its facilities above the lowest supervisory level (id.).

»-*

6

of exclusion. Its post-1965 performance is particularly inadequate

since American's work force then contained many long-tenured,

loyal, and experienced Blacks who would already have been super-

5/visors but for defendant's segregationist policies.

American's attempt to compare its hiring statistics to

an imaginary figure for the number of Blacks in the Richmond

"supervisory work force" is doubly defective. First, it extra

polates from available data on the basis of entirely hypothetical

6/

assumptions (Co. Br. at 14) . Second and more fundamentally, census

data based on jobs actually held reflects not just the qualifica

tions or interest of black job-holders, but also the nature of

opportunities open to them. Thus, American's reliance on

purported estimates of Blacks in the SMSA "supervisory work

force" incorporates the exclusionary practices of other Richmond

employers as a basis for a finding of non-discrimination.

Common sense verifies that absurd conclusions flow from this

5/

Similarly 19 qualified white candidates advanced to

supervisory positions, leaving an "enriched" pool of black talent

in hourly paid jobs. American presented no evidence that it had

attempted to identify able Blacks or to encourage their advancement.

£/

American's calculation assumes, without justification,

that Blacks and Whites respectively are evenly distributed among

the three separate census categories of crafts, foremen, and

"related." It is noteworthy that the district court was cognizant

of "the scarcity of qualified [black] craftsmen" (App. 39; cf.

Co. Br. iit 44). Craft jobs such as electrician do require some

concrete skills and knowledge which Blacks might not have obtained

in Richmond. American's supervisory jobs wore not shown to

require any such technical knowledge, and the district court

did not identify any scarcity of potential black supervisors.

7

twisted logic when American concludes that only 12% of available

supervisory personnel are black and only 5% are female (Co. Br. at

14 n. **). This conclusion is indefensible in light of the

absence of objective standards or educational requirements for

American 1s supervisors.

B. American Failed To Show The District

Court1s Remedy_Improper____________

American does not contest the propriety of the

changes in its selection procedures ordered by the district

court, but attacks only the provision for temporary preferential

appointment of Blacks and females as being impermissible under

Title VII. American's argument is misplaced. It relies

primarily on the authority of Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra,

on Section 703 (j) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(j), and on its

7/

legislative history (Co.Br. at 45-4G). The discussions cited deal

with a situation fundamentally different from that of the case

at bar; they consider quotas or preferences in the abstract,

not as remedial measures designed to terminate the effects of

discrimination. All the authorities relied on by plaintiffs (PI.

Br. at 53-54) are careful to specify that such preferences

are constitutionally and statutorily proper only as a necessary

7/

American does not address the propriety of the relief

under 42 U.S.C. §1981. liven if its discussion of §703 (j) as a

limitation on Title VII relief had merit, that reasoning would

not preclude the district court from granting the relief under

42 U.S.C. §1981. Section 703 ( j) docs not limit the remedies

available under statutes other than Title VII. Contractors

Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secretary of Labor, 442

i’.2d 159, 192"" (3rd Ci r."~19 7I) , cert, denied-4 0'4 u7s.~ 854“ (1971) .

8

remedy for past discrimination.

Ill

8/

THE DISTRICT COURT APPROPRI/\TELY FASHIONED

AN IMMEDIATE POSTING AND BIDDING PROCEDURE

DESIGNED FINALLY TO TERMINATE THE DISCRIMINATORY

EFFECTS OF THE PAST SEGREGATED EMPLOYMENT SYSTEM

"As a man is said to have a right to his property,

he may be equally said to have a property in his

rights * * * If the United States means to obtain

or deserve the full praise due to wise and just

governments, they will equally respect the rights

of property, and the property in rights." James 9/

Madison, in the National Gazette, March 29, 1792.

8/See also Boston Chapter NAACP, Inc. v. Beecher, 504

F.2d 1017 (1st Cir. 19741, cert, denied, __ U.S. __(April 15,

1975), where the circuit court said:

"The goal of color blindness, so important

to our society in the long run, does not mean

looking at the world through glasses that see

no color; it means only that colors are moral

equivalents, to be treated on an equal basis.

We believe that our society is well served by

taking into account color in the fashion

used . . . [quota relief] by the district court.

[Id at 1027]

* * *

"Title VII was amended in 1972 and the legislative

debates at that time, particularly the failure

of Congress to pass the Dent amendment which

would have foreclosed all affirmative action plans

and racial balance relief, lend support to the

inference that Congress ratified the power of

the courts to impose color conscious relief of

the sort that had been approved in several

cases at the time the attempts to amend the

amendments to Title VII failed." (Id. at 1028.)

9/

Quoted in Taylor v. Armco Steel Corp. , 8 EPD 119550

(Sept. 14, 1973 , S.D. TexT) .

9

A. The Relief Granted Finds Support In

T i t lo_ VII And_ J t s_ 1 »og is 1 ativc History

The defendants' practices have in large part resulted

in the long-term black workers' being relegated to the lower-

10/

paying,-more menial jobs. As a result of these discriminatory

policies, Blacks have received only token opportunity to promote

or "qualify" for higher-paying jobs. The adverse effects of

this discrimination were increased by the relatively static con-

11/dition of the work force. Consequently, Blacks have suffered

and will continue to suffer severe economic harm until they

attain the job positions which they would have hud but for

12/

the discriminatory practices of the defendants.

.1 0/

The defendants have used several practices since

1965 which have preserved the racial inequity in job opportunity

and earnings; c.g., the 900 hour "qualification" requirement, the

filling of vacancies on a "temporary" basis, the ban on inter-

Branch transfer, the establishment of segregated seniority rosters,

and the establishment of line of progression requirements (PI.

Br. at .11-21, 29-38. Sec also p. 3, supra) Moreover, the over

whelmingly white supervisory staff, by selective communication

concerning job opportunities, has contributed to the continuance

of discrimination. See PI. Br. at 35, n.57, and p. 5 supra.

11/See PI. Br. at pp. 20-21, and pp. 28-30, inf ra. In the

top-four paying jobs in the fabrication department of the Virginia

Branch (the department at the Company which contains the greatest

earnings opportunities) there were only 60 vacancies from January

15, 1968 through October 2, 1973 (PI. Br. App. "D".). As a result

Blacks, as of December 31, 1973, held only 28 or 65 of these top

paying jobs, whereas Whites held 457 or 947, (Pi. Br. App. "F").

12/The loss in earnings is substantial. As of December

31, 1973 (excluding post-1967 hires) white males averaged $4.39;

or $.56 or 155 more than the $3.83 per hour which black males

averaged (Pi. BrT~App. "G"). Black females also earned less than

white females (Id.).

10

The district court designed relief which would terminate,

once and for all, the discrimination which has kept Blacks out

of the better-paying, more desirable jobs.

The court established a practical and equitable system

for the posting and bidding for hourly production jobs at the

Company with all jobs being filled on the basis of a non-

discriminatory seniority criterion, company seniority (App. 168-

174; see PI. Br. 41-42 ). The district court structured the

system in a practical and equitable fashion. The court excludedIV

certain key jobs from the immediate posting and bidding system

and provided that white workers would not suffer any reduction

in earnings (I_d.) .

This aspect of the relief fashioned by the district

court is consistent with the plain meaning of the statutory

language and, under the circumstances here presented, the

relief is consistent with the Congressional purpose. The pro

vision which defines unlawful practices is broadly drawn:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer--

* * *

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his

employees or applicants for employment

In any way which would deprive or tend

to deprive any individual of ompToyment

opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect h1s status as an employer because

13/

Any restriction on relief which is required to

terminate the effects of discrimination must meet the stringent

"business necessity" test. Rob.i nson v. Lori Hard Corporation,

444 l'.2d /91, 798 (4th Cir. 1971) cert dismissed 4 04 U.S. 10 06

(1971), Rock v. Norfolk & Western Railway Co., 473 F.2d 1344,

1349 (4th Cir. 1973) cert denied 411 U.S. 939 (1973).

■ff

11

of such

sex, or

Section

individual's race

national origin.

703(a), 42 U.S.C.

color/ religion,

(emphasis added).

§ 200 Oe-2(a) . W

As a parallel to this all-inclusive definition of unlawful

practices, the Congress provided district courts with wide dis

cretion to enforce the strong public policy to terminate dis

crimination in employment. Section 706 (g) , 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g)

reads in pertinent part,

. . . the court may . . . order such affirmative action

as may be appropriate, which may include, but is not

limited to, reinstatement or hiring of employees,

with or without back pay . . . or any other equitable

relief as the court deems appropriate. . .

The plain meaning of the statute, that the judicial remedy was

intended to terminate all aspects and effects of employment

discrimination, was made explicit by tire sponsors of the Equal

15/

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, which amended Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Conference Committee

of the House and Senate in its Scction-by-Section Analysis

reiterated the Congressional intent to give the district courts

plenary remedial powers:

The provisions of this subsection [706(g)] are

intended to give the courts wide discretion in

exercising their equitable powers to fashion

the most complete relief possible. In dealing

with the present section 706(g) the courts have

stressed that the scope of relief under that

14/

Section 703(c), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(c) contains

similar language defining unlawful union practices.

PI. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103

15/

12

Section of the Act is intended to make the

victims of unlawful discrimination whole, and

that the attainment of this objective rests

not only upon the elimination of the particular

unlawful practice complained of, but also requires

that persons aggrieved by the consequences and

effects of the unlawful employment practice be,

no far a_s possible, restored to a position where

they would have been were it not for the-unlawful

discrimination. 118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972).(emphasissuppl ied ,T 6/

The district court's remedy accomplishes the Congressional

purpose. Blacks are placed in the jobs"where they would have

been were it not for the unlawful discrimination."

Moreover, the remedy makes good sense. It is perhaps

easiest to evaluate the court's remedial order by a straight

forward example. A worker (who happens to be white) receives

a job promotion instead of another worker (who happens to be

black) because of the unlawful practices of the Union and

the Company. The white worker is no more qualified than the

black worker and has less seniority; accordingly, if the dis

torting factor of discrimination had been absent, the black worker

would have been awarded the job. It is difficult to argue

with the proposition that equitable relief from discrimination

would require that the black worker be placed in the job he would

have had if the Union and the Company had not discriminated.

The white worker is not prejudiced by this order of relief since

ho is simply placed in the position he would have had if he had

16/Senator Williams, a principal sponsor of the

Ecjual Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, introduced a similar

analysis into the Record in the Senate prior to the Senate's

passage of the Act. 118 Cong. Rec. 4972 (1972).

13

not been afforded a discriminatory and unlawful advantage. The

apparent equity of the district court's order, providing for the

victims of unlawful discrimination to achieve the job position

which they would have had, absent the unlawful conduct, has been

routinely recognized and implemented under §10(c) of the National

18/

Labor Relations Act, 29 U.5.C. §160 (c).

Furthermore, the continued denial of opportunity to

black workers to work jobs which they had previously been denied

by discriminatory policies causes a continuing substantial

economic loss (See. PI. Br. at 43-43 ). The plain fact of

the matter is that a black worker, who is working as a "catcher"

and who,as a result of various discriminatory practices, has been

denied equal access to the job of "packing machine operator" in

the Virginia Branch, continues to earn approximately $.65 less

per hour than he would have earned if it were not for these

discriminatory practices (PI. Br. App. "F" ). Whatever the

form of relief provided by the district court, it must provide

a remedy which prevents this continued economic loss suffered

by Blacks as a direct result of the defendants' discrimination.

The lower court, by providing an opportunity for Blacks to

attain the jobs they would have had but for the discrimination,

17/

17/

In fact, the white worker has directly benefited by

the discrimination of the defendants. If not for discrimination,

he would have been working in lower job classifications. He has

therefore gained "windfall" income.

18/

See PI. Br. at 48-49.

1 4

has effectively remedied the problem of continuing economic

19/

harm.

B. Nothing In Title VII Or Its Legislative

History Restricts The District Court In

Fashioning Relief______________________

Neither the Company nor the Union discussed the

appropriateness of the district court's remedy for terminating'

employment discrimination; rather, the defendants rely on several

arguments which purport to carve out exceptions to the undeniable

Congressional purpose of providing full relief from discrimina-

20 /

tion.

21/

There is nothing in the statutory language nor the

legislative history which prohibits the court's remedy. Rather,

the statute and the legislative history, as set out supra,

pp. 30-12, indicate approval of district courts' fashioning

19/

Other district courts, which did not order any dis

placement of incumbent workers, provided that Blacks would be

compensated for "future" economic harm. United States v United

States Stcel Corporation, 371 F.Supp. 1045, 1060,' n.38 (N.D.

Ala. 1973); Bush v. Lone Star Steel Company, 373 F.Supp 526, 538

(E.D. Tex 197 4)7 see PI. B r. at 43-4 3).“ "

20/

The Supreme Court has consistently held that the

district courts have broad discretion to frame remedies which

will fully terminate the effects of discrimination. Louisiana v.

United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965); Green v. County School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968); Swann v.

Chari ofte-Mocklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 15, 21 (1971) .

21/

The Company does not make an argument based on

the statutory language. The Union's argument, which is based on an

interpretation of §703 (h) of Title VII, is inapposite to the

issue presented. See fn.39 , infra.

oqq uo sooAopdiuo popnpoxo ApsnoxAOxd Pcll l(07’I/A Aux?duioo t? Aq

pojiij cue oi[A\ gxoqxo.A qox?pq joqqoqM jo uoxquuxuixoq op oxp

sxojox ApxGopo 'Axoaripto sqx ux pouxixmxo uoi(M 'qdcxfiexcd oqj,

‘O'9 61) ei ZL *o°H

• 6uoo Oil ( ' uoxqx?uxuixxosxp qsxxduiooox? oq oftnjxoqqns

XixjMupun ux? ppoq oq Amu qoojjo soqt?q opqxq ollJ xo-ljx?

sqsxp qons jo osn oxjq 'sxscq Axoqx?xixxuxxos xp x? uo

pouxt?quxx?ui ' ox') xq oin jo oqup d a x j o o j j o oqq oq xo xxd

'oxx? Buxuxcxq so quoxuAopduio xoj s q s xp luxqxcw

oxoijH ' -X0AOMOII) -JOIX-XCO poxxq sxoqxoM oqxqw oqq

jo osusdxG oqq qp sqqBxx Aqxxoxuos X ox nods uioqq

o a t 6 oq 'poxxq oxx? s o o x B o n o o u o ' x o ' sox o u p o p a

oxnjnj xoj s o o x B o n xojoxd oq xo 's o o x Bo n oxxq oq

xopxo ux s ojxqM oxx j oq — poqqcuixod 'poopux xo

_ poBxpqo oq qou ppnow oq *sxsx?q Axoqx’xixuixxosxpuou

t? uo s o x o u x? o x? a oxnqnj rpxj °T Apdiuxs oq PI no A

xtoxqcBxpqo s,xoAoxdino oqq 'qoojjo oqit f soutoo opqxq

oqq uoqo ooxoj Buxqxo/A oqxqAV-ppe Ul? 91 us ox

T? GG pux qcx?d oqq ux BuxqBuxuixxosxp unoq seq ssoxi

-xsnq t? j l 'opcluicxo xoj ' snq,[, * OAiqood'JO.xqox qoxi

pue OAxqoo d u o x d sx q oojjo sqi •sqxpixx Aq rxo i uo&

poqsxpqt?qso uo qoojjo ou o a l u ( ppno/A H A opqxj,

•gnssx qt? auo oqq uioxj quoxojjxp

Apoxxquo uoxqcnqxs x? oq Buxxxojox o x o m sxoqcuos 3qq qcqq

xuopo s c qx 'poxtxiuGxo sx Aueduioo oqq Aq oq paxxnjox quouiBcxj

aouoquos oqq suxuquoo qoxqM qdox6x?xr?d ox xq uo oqq uoqM ’9£

qx? -xg '07) oos -oqcuog oxiq Aq fryGI J° 'Î V sqqBxn X fA P 0!-M-

jo uoxqcxopxsuoo oqq Buxxnp osx?o put? qxx?po sxoquuos Aq pxoooy

oqq oqux poonpoxqux uinpuexouisw OAxquqoxdxoqui oqq uioxj

'qxoqxtoo jo qxio uoquq ' quoui5x?xj oousquos u sx pnj/Appuxx sx?m

u o r s x A O x d pcxpouiox s,qxnoo qoxxqsxp ox[q qt?qq uoxqxsod xxoxjq jo

qxoddns ux squepuojap oqq Aq poqro Axoqsxq OAxqepsx&ap Apuo

3q lL ■ xioxqx?uxmxxosxp jo oqoojjo oqq ppx? puo qoxqo soxpomox

ST

16

basis of race, may lie afforded "fictional" seniority.

"Fictional seniority" is not at issue here. No workers

would be fired or laid off as a result of the decree; rather,

the district court lias ordered that the jobs at the Company

be redistributed on the basis of a non-discriininatory criterion,

the actual seniority of employees. Neither the Clark-Case

Memorandum nor the Congress directly confronted the question

of appropriate relief for the victims of discriminatory

seniority systems. Note, Title VII, Seniority Discrimination,

23/

and the Incumbent Negro, SO Harv. L. Rev. 1260, 1271 (1967). The

statute does not define the explicit relief which is to be

applied to discriminatory seniority systems. The Supreme

Court lias stated with respect to a statute (the NLRA) similar

to Title VI1 that "unlike mathematical symbols, the phrasing

of such social legislation . . . seldom attains more than

approximate precision of definition," and therefore it is

proper to seek guidance in the broad legislative policy.

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313 U.S. 177, 185 (1941). In light

of the strong Congressional purpose to end employment discrimina

tion and afford full relief "as soon as possible" as made explicit

22/

22/

The Supreme Court has just granted certiorari

to consider an aspect of this question. Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Company, 4 95 F.2d 39 8 (5th Cir. 19 7 4)/ "ccfrt.

granted 43 U.S.L.W. 3510 (March 24, 1975), see footnote 39, infra .

23/

This Note is relied on by both the Company (Br.

at 33-36) and Local 182 (Br. at 19). Moreover, this Note which

set forth the various alternatives for seniority relief, "status

quo", "rightful place" and "freedom now", was the analytic basis

for the early Title VII cases which prescribe appropriate

seniority relief. See Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980,

9 8 8 (5th Cir. 1969), cor t. dcjnied 397 U. sT 919""(1970) .

17

by Congress during the passage of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972, see supra pp. 11-12, the approach

established by Phelps militates for allowing the district

court to design relief which will immediately terminate the

effects of discrimination.

The defendants principally rely on the Fifth Circuit's

1909 decision in Local 189 v. United States, supra, which

suggested that "rightful place" relief, not "freedom now"

relief, is the appropriate remedy for unlawful seniority

24/

discrimination.

C. The Early Decisions Do Not Preclude

Relief As Granted In-The Instant Case

It is crucial that we closely evaluate Local 189

United Papermakers £ Paperworkers v. United Stales, supra,

its specific reasoning, and the authority relied on (or not

25/relied on). Initially, it must be noted that if it was

24/Under the "rightful place" theory the victims of

employment, discrimination must await future vacancies before they

can exercise the non-discriminatory seniority criterion to move

to the job they would have had but for the discrimination. Under

the "freedom now" theory the victims of employment discrimination

would be permitted to move immediately, if qualified, to the jobs

they would have attained but for discrimination. See Local 189

v. United States, supra at 988. The alternative forms of relief

are fully described in Note, Title VII, Seniority Discrimination,

and the Incumbent Negro, supra at 1268-75.

25/The opinion in Quarles v. Phi lip Morris, Inc., 279

F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968), did not reach the present issue. The

court there stated that Congress did not intend "reverse dis

crimination" -- the preference of Blacks without seniority over

Whites with employment seniority, id. at 817. Plaintiffs do not

seek any preference here, just the effective use of their employ

ment seniority. (Continued on p. 18.)

FT■ 1.2

18

intended to be of universal application, the Fifth Circuit's

26/

rejection of "freedom now" was dictum. Even if it was intended

only with respect to the case before it, it was unnecessary to

a resolution of the question whether "rightful place" or "status

quo" was appropriate. It was based neither on an interpretation

27/

of the statutory language nor on the legislative history.

Father, the Fifth Circuit relied for its interpretation of appro

priate seniority relief on equitable considerations and, while

unstated, on the district court's discretion to design effective

28/

relief. Although the Local 189 analysis may have been proper

(Continuation of footnote 25)

In Quarles, the district court held that a "rightful

place" theory incorporated in the plant within two and one-half

years of the effective date of Title VII would reasonably comply

with the Act. The court did not consider, nor was it asked to

consider, a "freedom now" theory; moreover, it was not presented

with facts, as are present in this case, that Blacks are still-

relegated to the lower-paying, more menial positions almost ton

years after the effective dale of Title VII.

Similarly, other courts have followed the dictum in

Local 189 without any re-evaluation of its underlying premises

because there was no issue that "rightful place" would not be

effective and no challenge to the "rightful place" theory was

presented. Finally, as is described, infra, many, years have

now passed since the effective date of Title VII and courts

should properly implement remedies that will work to finally

terminate employment discrimination. See Green v. County

School Board of New Kent. County, supr a at 438-39.

2_6/

The district court had adjudged the job seniority

system at Crown-Zellerbach unlawful and had ordered "rightful

place" relief. The defendants appealed these orders, but the

government did not appeal the "rightful place" limitation on relief.

27/— The Fifth Circuit stated that the legislative history

of the Title is singularly uninstructivo on seniority rights."

Local 189 v. United States, supra at 987.

') Q /-— Since the government had not requested back pay, the

issue of continuing economic harm which results from the "right

ful place" theory was not presented. See pp. .13-14, supra.

1 9

in the circumstances presented there within a few years after

the effective date of the Act, it does not follow that it is

proper in this case. Local 189 clearly does not warrant

this Court's reversing the application of a "freedom now"

relief order designed to remedy the continued denial of equal

employment opportunity ten yoars after the effective date of

the Act.

However, the Fifth Circuit's suggestion in .Local

189 that the "rightful place" doctrine accords with the

purpose and history of the legislation has been read as a flat

rejection of the "freedom now" concept. That suggestion seems

to contradict the court's earlier expression of agreement with

the holdings in Quarles (1) that "[n]othing in §703(h), or in

its legislative history suggests that a racially discriminatory

seniority system established before the act is a bona fide

seniority system under the act," (2) that nothing in the legisl.a-

pp\/0 history "suggests that as a result Oj' past discrimination

a Negro is to have employment opportunities inferior to those of

a white person who has less employment seniority", and (3) "that

Congress did not intend to freeze an entire generation of Negro-

employees into discriminatory patterns that existed before the

Act. (416 F.2d at 987-88).

The apparent rejection of "freedom now" mirrors the

conclusions of the author of the Note (written in 1967), Title

VI1, Seniority Discrimination and the Ineumbent Negro, supra.

This Note expressed a preference for the "rightful place"

approach and even indicated that considerations of prudence might

20

dictate acceptance of something lass. As justification for .its .

position the article pointed out that: (1) The feasibility of

equal employment opportunity legislation depends to a great

extent on voluntary compliance; (2) the EEOC does not have the

facilities to oversee all the employers and unions which come

before it and to police compliance with conciliation agreements

and court orders; (3) efforts at compliance might provoke possible

obstructive practices by hostile unions and employers; (4) the

necessity for court action when conciliation fails may impose a

considerable financial burden and delay on complainants; and

(5) some state FEPC1s had refused to seek conciliation agreements

which adversely affected white seniority rights (id at p. 1282).

Notwithstanding these political considerations, the

article appears to acknowledge that Title VII requires an adjust

ment of seniority rights to eliminate differences in present

competitive status attributable to past employer discrimination.

What it proposed was a compromise between (1) merely ending

explicit racial discrimination and (2) affording complete relief

from discrimination by requiring the displacement of white workers

or the disruption of their job expectancies. The suggested com

promise injected into this area of litigation the concept of

29/

"deliberate speed" which had so long frustrated the desegrega

tion of public schools, and demonstrated that the vitality of

established law should not be allowed to yield simply because of

disagreement with it. Cf. Brown v. Board of Education,

Id at p. 127429/

Pf"

21

349 U.S. 294, 300 (1955); Green v. County School Board of New

Kent Count y, supra.

Clearly, Quarles did not yield to these political

considerations or adopt "rightful place" as an unvarying

standard. And it is at least questionable whether Local 189

did. In those cases the courts perceived that the remedies

employed would in fact terminate the effects of discrimination

within a reasonable time.

D. The Specific Relief Granted Is Required

By The Law And The Ev1 dence_____________

It is now almost ten years since Title VII became

effective. A denial of complete relief can no longer be

justified upon "equitable" considerations for resulting incon

veniences and disruptions. This Court in 1972 applied the-

Civil Rights Act of 1866 (42 U.S.C. §1981) to tire area of equal

employment opportunity, as other circuits had done. Brown v.

Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., supra. See also Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver Company, 415 U.S. 36, 47, fn 7 (1974); Mack1in

v. Spector Freight System, Inc., supra, and cases, therein cited

in footnote 26. That Act is without limitation as to what

racially discriminatory practices are unlawful and is without

restriction as to what redress may be extended. In making its

1972 revisions to Title VII, the Congress again gave to the

courts the broad remedial power to "order such affirmative

action . . . or any other equitable relief as the court deems

appropriate". Experience has shown that the process of attrition

following the termination of deliberate discrimination is not

22

30/

efficient in the removal of the effects of past discrimination.

The approximately 150 black workers who wore hired

prior to 1967 average almost thirty years of employment. Yet

these employees remain disproportionately relegated to the lower

paying and more menial jobs (PI. Br. Apps. B, D, F, G). The

31/

numbers of vacancies available to these employees has

30/

Moreover, the high employment rate and continued

industrial growth which marked industry in the United States in

the 1960's and led courts to assume that "rightful place" relief

would be effective, is unfortunately quite different from the

present state of American industry.

The Second Circuit, in expanding the scope of

seniority relief available in order to remedy discriminatory

effects in layoffs and recalls, made the following relevant

observati on:

" . . . when the Attorney General instituted the

earlier case in 1.967 only 3.8 percent of the

nation's workforce was unemployed. [The Local 189

case was instituted in January, 1968] . . .

The very first case [Quarles], involving the issue

of discriminatory seniority and transfer was

decided only in January of 1968 . . . . The dis

criminatory impact of a departmental seniority

recall system where there have been a multitude

of layoffs may not have been foreseen by Government

in the earlier suit [United States v. Bethlehem

Steel Corp. , 446 F.2d 652 (2nd Cir. 19 7.1.) ] ,

especially where the Government was concerned with

establishing a favorable precedent. . . "Milliamson

v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F.2d 1201, 1204

(.19 7 2) , cert. den led, 41 1 U . S . 9 31 (19 7 3) .

Similarly, the district court properly took economic reality into

account in order to formulate an effective remedy.

31/It is plain that the term "vacancies" which is used

in the "rightful place" theory includes "temporary" vacancies

and "vacancies" created by layoffs. United States v. Hayes

International Corp., 456 F.2d .112, 119 (5th Cir. 1972); United

States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co. , 4 51 F.2d 4.18, 4 51 (5th Cir.

T9 7T7“cert7“ lenIed“406 IF. S. 906 (1972) ; United (Continued p. 23)

23

been severely restricted by the Company s practice, yet con

tinuiny, of filling temporary V3cancies in sucli wanner ns to

perpetuate the discriminatory pattern. Between July 2, 1965

and March 1, 1974, 73 whites received permanent'promotions to

automatic machinery operator positions. Of those promotions,

59 occurred prior to the institution of "job posting and employee

bidd ing" i n 19 6 8 .

But for the violations of Title VII, more of the black

employees would now be working in these preferred positions.

Seventy-three incumbent white employees wore assigned to these

positions subsequent to the effective date of tire Act, although

there were approximately 150 black employees with more seniority.

Neither the lav;

initially tried)

would hold that

irote nor Quarks nor Local 18 9, written (or

within three years of the Act's effective date

these assignments were lawful when made and are'

32/

therefore beyond the revisionary reach of Title VII.

(Continuation of footnote 31)

States v. United States Steel. Corporation, supra, at 1056-57.

Rogers v. Internal;ional Paper Co. , supra, at 1353-56.

Of course, the defendants discriminated against Blacks

in both the "remanning" of positions after reductions-in-force

and in the filling of temporary vacancies. (PI. Dr. at pp. 12-15,

17, 31-35).

32/

"When a seniority right 'matures' in the award of a

particular job before Title VII's effective date, the award may

plausibly be viewed as a closed transaction, not subject to

attack after the Title comes into force." Note, Title VII,

Seniority Discrimination, and the incumbent Negro, supra, at 1269;

soq also Gem]d, Employment Security, Seniority and Race: The Bole

off' Title VII of tlu; Civil' Right's Act of 1.9 64 , 13 Howard L. J. 1,

97 n. ~3 2 "(1 967).'

24

The suggested insulation of the earlier discriminatory

job assignments is not tenable. But for the earlier violations

33/

of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, others of the black employees

would be- and would have been in these jobs. Earlier literature

on Title VII does not take the .1866 legislation into account and

thus it reaches the conclusion that a paramount right vested in

the white workers who prior to July 1965 had obtained the pre

ferred job assignments from which Blacks were barred.

If there ever was reason to suppose such vested

right in any case, it v/ould not apply here. The defendants,

Company and Unions, do not and have not considered that workers

have vested rights in their respective job assignments. Prior

to the enactment of Title VII, the Company, pursuant to agreement

with the Union, "bumped" senior male employees from preferred •

job assignments in order to place white females in jobs that

did not require heavy lifting. Subsequently, a suit styled

Lindsay v. American Tobacco Company was brought by white males,

pursuant to 'title VII, alleging unlawful discrimination because

of sex. The basis for settlement of the suit was that the

white females were "bumped" from these preferred positions

by white males with higher seniority (App. 411-413). The

"bumping" technique was expressly recognized in Collective

33/

"IT]gnoranee of the rights secured by these statutes

is not a defense to an action brought to enforce them". Tillman

v. Wost-JIavon Recreation Association, Inc., _ F . 2 d __(4 th Cir.

1975) decided April 15, 1975, ho. 14,957.

• r

25

Bargaining Agreements until March 1974. Job placement based

on seniority prevailed, except as to Blacks. More urgently

should it prevail hero to make equal employment opportunity

without regard for race a reality.

After reviewing the continuing effects of the

discriminatory practices by which Blacks were excluded from

the higher paying jobs and the relative scarcity of vacancies,

the district court rightfully concluded that a form of

"freedom now" relief was necessary to insure the effective

implementation of Title VII and that the long-term black

employees at /American Tobacco would at long ]ast have benefit

33/

of equal employment opportunity.

34/

34/

PX 35 FF (1971 and 1974) . Other "bumping" practices

are mentioned in PI. Br. p. 46.

35/Similarly, in school integration litigation the

"freedom of choice" remedial plans which grew out: of . the doctrine

of "all deliberate speed" were, after they proved ineffective in

certain areas, held to be unconstitutional and school boards were

required to formulate plans that would work in fact Groan v.

County School Board of New Kent County, supra, at 438-39:

"The time for mere 'deliberate speed' has

run out . . . ; the context in which we must

interpret and apply this language [of Brown II]

to plans for desegregation has been significantly

altered . . . . The burden of a school board

today is to come forward with a plan that promises

realistically to work, and promises realistically

to work now." (citations omitted)

Sec also Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 529-531 (1963);

TQdxaTider v. Holmes County Bd. of lid. , 396 U.S. .19, 21 ( 1969) ;

Swann v. Char lot to-Mecklenburg lid. of Ed. , supra at 15.

2 6

E. Equitable Considerations

Support Red_Circling _

The district court ordered that incumbent employees

who might be "bumped" to lower-paying jobs would have their

wages "red-circled" in order to prevent any loss in pay

(App. 41, 172-73). This provision is fully consonant with

36/

the equitable discretion of the district court. First,

the district courts have broad discretion to formulate

equitable decrees which both enforce the statutory policy

and are workable and fair. Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Ed., supra, at 15, 27; Lemon v. Kurtzman, 4.1.1 U.S.

192, 200-01 (1973). It was a proper exercise of this broad

discretion for the district court to formulate a remedy which

prevented monetary loss to any incumbent who, even though he

might have benefited from discrimination, had not violated

Title VII. Secondly, since the Company in any case would have

had to compensate black workers for continued economic harm

which they would have suffered if "rightful place" relief

had been ordered, the Company has no greater financial

37/

liability under the lower court's remedial order. Under the

.lower court's order, Blacks have the opportunity to move into

the job they would have had but for discrimination. Accordingly,

36/

The Company objects to the "red-circling" provision

for displaced incumbents (Co. Br. 37).

11/ For a description of the Company's liability for

continuing economic harm,see PI. Br. 42-43, supra, pp. 13-14.

2 7

although they will not be "made whole" as to past losses, they

39/

3_8/

suffer no continuing additional economic harm.

0/

"Rightful place" relief is no "sacred talisman"; it

may not take precedence over its avowed purpose, i.e., the termi

nation of employment discrimination. When, as the lower court

38/" . . . Of course, no theory of Title VII will close

the gap in lifetime earnings figures, since the economic losses

exprienced before Title VII became effective cannot be restored."

Note. Title VII, Seniority Discrimination and the Incumbent Negro,

supra, fn. 72.

39/

Local 182 makes a further argument in opposition

to the Court's remedial provision based on several courts of

appeals decisions which indicate that it is not permissible to

afford "fictional" seniority to Blacks, even though Blacks had

been denied employment (Local 182, Br. at 9-13). Sec Waters

v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 502 F.2d 1309 (7th C.ir. 1974); Jersey

Centra.! Power & Light Cc. v. Local 327, IBEW, 508 ” OA rp'

Cir. 1975); Franks v.

398 (5th Cir. 1974), cert.

Cc. v. Local 3 2 7, IBEW, 5.08 F.2d 687 (3rd

Bowman Transportation Company, 495 F.2d

(March 24,

1975)

granted, 4a U.S.1..W. 3510

Several courts of appeals which were not mentioned by .

Local 182 have ruled that Blacks or women who were the victims

of discrimination may be afforded relief even if it alters an

employment seniority system. Meadows v. Ford Motor Company,

510 F.2d 939, 948-9 (6th Cir. 1975); Jurinko v. Edwin L.

Wiegand Co. , 477 F.2d 1038, 1046 vacated and remanded on other

grounds, 414 U.S. 9 70 (19 7 3) , reins t a l: ed, 497 F. 2d 403 (3rd Cir.

1974); see United States v. Sheet Metal Workers International

Ass'n. , Local '3 6, 41 6" 1'.'2d 123, "13IT 133-34 ( 8*Lh"Cir T 19691

'i‘hc difficult questions presented by these conflict

ing opinions are not at issue here. The plaintiffs do not sock

any "fictional" or "preferential" seniority, they only seek

to finally utilize in a manner unencumbered by any discrimina

tion their employment seniority.

40/

See Green v. Connty School Board of New Kent

County, supra, at 440.

28

found, it is necessary to achieve the Congressional purpose of

providing equal employment opportunity by a system of relief

other than "rightful place", this Court should not reverse

the district court and order relief that would not fully and

finally terminate the effects of discrimination.

IV

THE DEFENDANT COMPANY'S STATISTICAL EVIDENCE

DEMONSTRATES THAT BLACKS ARE STILL "LOCKED IN"

TO THE LOWER PAYING POSITIONS AT THE BRANCH PLANTS

The Company makes three statistical, assertions which

must be clarified if this Court is to understand how Blacks

have been "locked in" to lower paying traditionally black jobs

and departments. Although the Company would have the Court

believe that this data proves that all the vestiges of past

racial discrimination have now been removed, the statistical

comparisons witness plaintiffs' arguments.

First, the Company states that from July 2, 19 C 4 to

March 1, 1974, 30 of 145 promotions to operator of automatic

machinery were received by Blacks (Company's Brief, pp. 11 and

22 ). However, the Company did not mention that 1.16 of these

promotions (104 White, 12 Black) occurred during the period

prior to January 15, 1968, when the blatently discriminatory

41/

system of seniority plus "qualifications" was in effect. More

over, the Company neglects to point out that "automatic machinery

41/

Prior to January 15, .1968 , the Company's system of

filling temporary vacancies on a departmental basis and its heavy

reliance on the temporary vacancy system to fill operator posi

tions all but eliminated the opportunities for Blacks to fill

these positions.

29

includes "container packer", "schmermund boxer" and

"prefabrication department" operator classifications which

either pay lower than packing and making machine operator

rates or wore already held by Blacks (See Appendix "F1,

Pa_tJ:erson Brief) .

Secondly, the Company asserts that 166 of the 659

promotions at the Virginia Branch between July 1, 1964 and

March 1, 1974, were received by Blacks (Company's Brief,

pp. 12 and 22). When the number of promotions to the more

desirable automatic machine operator positions is subtracted

from the total number of promotions, the result shows that 514

of these promotions were for laborer classifications in the

prefabrication or fabrication departments,. positions already

42/

hold by the vast majority of black employees.

Thirdly, the Company states that between January 15,

1968 and November 11, 1974, 50.1% of the employees signing

for positions and 51.5% of the successful bidders were black

(Company's Brief, pp. 12 and 23). This simply shows that

the Company's blade employees will aggressively use their

seniority to improve their position when given an opportunity

to do so. Moreover, these statistics refute the Company's

assertion that "a large number of the class members refused to

42/

659 total promotions loss 145 promotions to automatic

machinery operator (Bee Ex. App. 3, VB-6).

30

bid on vacancies (Company's Brief p. 11.)

Finally, the defendant Company repeatedly refei's

throughout its brief to evidence which was not presented during

the trial of the instant case. Much of the Company's data is

based on information updated through November 11, 1974 (four

months after the trial of this case), which was introduced into

44/

the record through an attempted proffer of additional evidence

(App. 79-136). The district court examined the defendant

Company's proffer (App. 162-164) and concluded that the

requests were "in actuality a reargument of the merits of the

actions," and that ”[n]o finding of substance [was] requested

that [had] not boon requested before".

The statistical evidence in the record of this case

indicates that trie only explanation of the fact that Blacks

occupy only 28 of the 457 highest paying positions in the TWIU

bargaining unit is that the Company's racially discriminatory

practices and policies have prohibited them from obtaining

these positions (See Appendix "F", Patterson Brief).

43/

43/

To support this assertion, the Company cites the

testimony of nine class members; three of whom were the first

black employees to be transferred into the fabrication depart

ment (Hopkins, Branch and Green); three of whom have been hired

since 1968 (McLane, Anderson and Dickerson); and two of whom have

used their seniority to successfully bid on jobs (Mosley, 1971 to

watchman, App. 367; and, Howard, to learner adjuster, the second

highest paying classification in the TWIU bargaining unit. Howard

is the only Black among the 82 adjusters in the TWIU bargaining

unit, Appendix "B", Patterson Brief).

4 4/- Appellees Patterson and FF.OC were not afforded the

opportunity f.o examine the factual basis for the information con

tained in the proffer or to cross examine the individuals who

gathered the proffered evidence.

3 1

'J'HF. EEOC'S APPROVAL OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF

"LINES OF PROGRESSION" HAS NO BEARING ON THE

DECISION OF THE DISTRICT COURT

V

The defendant Company places a great deal of reliance

on the fact that a representative of the EEOC assisted in

the creation of the "lines of progression" (Company's Brief

pp. 12 and 23) which were found to have a discriminatory

effect on the promotional opportunities available to black

employees (App. 60-61). This reliance is misplaced.

Section 713(b) of Title VII' provides that:

". . . No person shall be subject to any

liability . . . for the commission . . . .

of an unlawful employment . . . practice

if [the act complained of] was . . . in

conformity with, and in reliance on any

written interpretation or opinion of

the Commission 42 U.S.C. §2000e-12(b)."

The Fifth Circuit held in Local 189, United Papermakers

and Paperworkers v. United States, supra, that:

"The key phrase in this provision is ''written

opinion or interpretation of the Commission'.

The EEOC published its own interpretation

of the phrase in the Federal Register in

June 1965, before Title VII took effect and

some six months before the public stalements

lit isiTue KereT~"Only" 7a) a letter entitled

'opinion letter' and signed by the General

CounsoJ on behalf of the Commission or (b)

matter published and so designated in the

Federal Register may be considered a 'writ

ten interpretation or opinion of the Com

mission' within the meaning of section

713 of Title VII." 29 C.F.R. §1601.30,

Id at 997.

The action? the EEOC which the Company5 Of

relies on do not fall into either of these categories.

See also, Kagan v. National Cash Register, Co., 481 F.2d 111

1125-1126 (D.C. Cir. 1973); Enroois v. United Air Lines,

Inc,, 444 F.2d 11 94, 1200 (7th Cir. 1971) , cert, denied,

404 U.S. 991 (1971); Grinnn v. Wes tinghouse Electric Corp .

300 F.Supp. 984, 988-991 (N.D. Cal. 1969). Neither the EEOC

participation in the formulation of the discriminatory

''lines of progression'1 nor the Company's bare assertions

that the lines are predicated on a need for plant operating

efficiency (Company's Brief p . 13) constitutes a legal

defense to the discriminatory effects of these barriers.

33

THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY ORDERED "INTER

BRANCH TRANSFER RIGHTS BASED ON COMPANY-WIDE

SENIORITY" TO INSURE ADEQUATE RELIEF FOR

ALL MEMBERS OF THE CLASS

A. The Richmond and Virginia Branches Must Be

Considered As A Single Facility If■Meaningful

Relief Is To Be Provided For /ill Class Members

The defendant Company's argument against inter-branch

transfer relief is predicated on the premise that the district

court ordered permanent transfer rights between Branches (Com

pany's Brief, pp. 39-40). This is not the case. The district

court's decree simply provides, for a limited period of time,

an opportunity for those class members who indicate their desire

to transfer, and who arc not able to move to the Branch of their

choice during the court ordered posting and bidding procedure, to

transfer as vacancies occur (App. 173-174). In its carefully

structured relief provisions, the decree provides that after these

class members have been given the opportunity to move to the Branch

of their choice, the defendants may re-establish "plant-wide"

seniority oi' any other type of promotional system which complies

with the standards of Title VII.

The Company's assertions to the contrary, the

Richmond and Virginia Branches operate as e* single unit in many

respects. For example, accounting and record keeping duties for

both Branches are performed by the same office staff (App. 45).

The Shipping Department at the Virginia Branch ships the products

of both Branches (App. 46). Moreover, the defendant Company has

on two occasions, the last being between 1957-1959, permanently

transferred employees from one Branch to the other (App. 45). In

V I

rv

addition, certain processes which are required by the Richmond

Branch are performed by Virginia Branch employees (App. 568-569).

Furthermore, it is clear, even from the defendant

Company's description, that many of the processes at both Branches

are strikingly similar. For example, whether making cigarettes

or smoking tobacco, the prefabrication departments of both Branche

"receive tobacco in strip form" and prepare it for fabrication by

"flavoring, drying, cutting, blending and storing" it- (Company's

Brief, pp. 8 and 10). The fabrication departments package the

tobacco for the consumer.

In addition, the district court noted that the two

Branch plants are very near one another (App. 56-57 and 77) .

Moreover, the district court received uncontradicted evidence

from two expert witnesses that 9 of the 15 jobs which they

evaluated at the Richmond Branch were underpaid (PX--49). Over 90%

of the employees in these classifications wore black. None of

the eight evaluated jobs in the traditionally white fabrication

department of the Virginia Branch were found to be underpaid

(PX-49).

Although the district court questioned the propriety

of determining whether or not a particular job is underevaluated

or underpaid (App. 37), the court did find that jobs at the

Richmond Branch have traditionally had lower wage rates than jobs

at the Virginia Branch (App. 63).

Based on the foregoing facts, the district court

found that the "presently practiced plant wide seniority system

3 4

. . . contributed to the perpetuation of the discrimination"

(App. 56-57).

In order to provide some form of meaningful relief to

the 90 black employees at the Richmond Branch, who comprise 532.

of that Branch's production unit work force, the district court

was compelled to formulate a mechanism whereby these employees

could escape a depressed wage structure which had become increas

ingly worse as the Branch work force became predominantly black

(Ex. App. 20, RB--2) . Anything less would have locked these Blacks

into a location where there are only 36 positions with a wage rate

greater than $3.80 per hour, as compared to the more than 500

positions at the Virginia Branch which exceed this rate.

In formulating relief from discriminatory practices,

courts are required to order such affirmative action as may be

appropriate. Local 53_ of International Ass 1 n of Heat and Frost

Insulators & Asbestors Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047, 1052

(5th Cir. 1969); Lea v. Cone Mills Corp.,' 467 F.2d 277 (4th Cir.

1971); United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co. 451 F.2d 418,

458 (5th Cir. 1971), cert. denied, 406 U.S. 906 (1972). Under the

circumstances of the instant case, the ordering of Company wide

seniority and transfer rights is clearly appropriate.

B. Section 703(h) Of Title VIJ Is Not

Applicable To The Case At Bar

Patterson plaintiffs hereby adopt and incorporate by

reference that section of the appellee EEOC reply brief concerning

the applicability of Section 703 (h), found at pages 6 through 8

3 5

of said brief.

36

THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY FOUND

THAT THE TWI U WAS LIABLE FOR THE

UNLAWFUL EMPLCF'NBNT PRACTICES AT THE COMPANY

The collective bargaining agreements negotiated by Local

V I I

.182, TWIU and the Company were the principal mechanism for per-

4 5/

petuating the discriminatory allocation of jobs (App. 40).

It is enough that the consequences of the contracts are discrim

inatory for the Union which negotiated the contract to be held

liable under Title VII. John soil v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber

Company, 491 F.2d 1364, ]381 (5th Cir. 1974); Macklin v. Specter

Freight Systems Inc. supra; see Robinson v. Lori Hard Corporation,

444 F.2d 791, (4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006

4 6/

(1971). However,

by the Unions were

ferential position

in this case seniority contracts negotiated

specifically tailored to preserve the pro-

which white employees attained prior to 1963.

47/

when all jobs at the Company were filled on a segregated basis.

45/

The Company's historical segregated staffing of jobs

was acquiesced in and supported by the TWIU's maintenance of

segregated local unions (App. 48, PI. Br. at 9-10) .

46/

In fact, Title VII places an affirmative duty on

unions to eradicate the continuing discriminatory effects of their

prior policies of racial preference. Foe Carey v. Greyhound Bus

Company, 500 F.2d 1372 (5th Cir. 1374) . In any case, to allow

the Unions to escape the consequences of their purposefully

discriminatory acts would undermine the effective implementation

of Title VII. Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., supra

at 989.

47/

The specific provisions, "seniority plus qualifica

tions", the maintenance of racially segregated seniority rosters,

and line of progression requirements are described in the

Plaintiffs' Brief at 11-21, 29-38. (Continucad at p. 37)

Although directly involved in the establishment and

perpetuation of the discriminatory practices, the TWIU denies

that it is liable under Title VII or §1981 by attempting to assert

the independence of Local. 182 and the lack of "agency" relationship

and by divorcing itself from the negotiating or signing of the

collective bargaining agreements. In light of the undisputed

48/

evidence this is an imaginative argument.

3 7

The TWIU's primary assertion, that it is neither a party

to nor bound by the collective bargaining agreements, is contra

dieted by the explicit language of the contract. For example,

Article 11 §A of the 1974 agreement states that:

The Union agrees not to ratify an unauthorized strike.

It fux thei agrees that if an unauthorized strike occurs,