Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Arabian American Oil Co. Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Arabian American Oil Co. Brief Amici Curiae, 1990. 171632ab-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/28a3a096-2027-4512-8c82-2b781ff891fd/equal-employment-opportunity-commission-v-arabian-american-oil-co-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

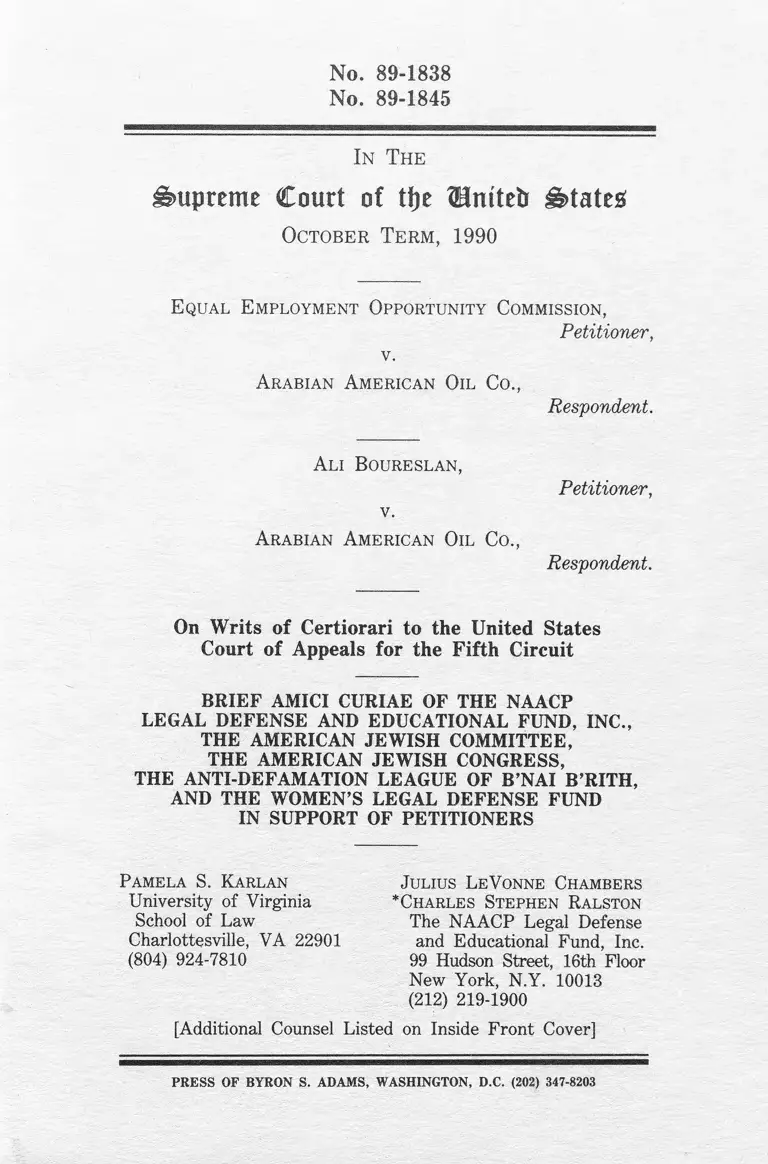

No. 89-1838

No. 89-1845

In T he

Supreme Court of tfje Hmtetr States!

October Te r m , 1990

E qual E mployment Opportunity Commission,

Petitioner,

v.

Arabian American Oil Co,,

Ali Boureslan,

v.

Arabian American Oil Co.,

Respondent.

Petitioner,

Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE,

THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS,

THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B’NAI B’RITH,

AND THE WOMEN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

Pamela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

J ulius LeVonne Chambers

*Charles Stephen Ralston

The NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

[Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Front Cover]

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

Amy Adelson

Lois Waldman

Marc D. Stern

American Jewish Congress

15 East 84th Street

New York, N.Y. 10028

(212) 879-4000

Ruth L. Lansner

Steven M. Freeman

J ill L. Kahn

The Anti-Defamation League

of B’nai B’rith

823 United Nations Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10017

(212) 490-2525

*Counsel of Record

Samuel Rabinove

The American Jewish

Committee

165 E. 56th Street

New York, N.Y. 10022

(212) 751-4000

Donna R. Lenhoff

Women’s Legal Defense

Fund

2000 P Street, N.w.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 887-0364

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii

Interest o f Amici Curiae . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

SUM M ARY OF ARGUM ENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

ARGUM ENT .............................................. 9

Introduction ..................................... 9

I. T itle VH Was Enacted Against the Backdrop of

Congress’ Long-Standing Concern With Ensuring

Equal Employment Opportunities in International

Commerce for American Citizens . . . . . . . 12

II. One of the Purposes of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 Was To Promote Nondiscrimination Abroad 25

III. Section 702 Should Be Construed To Give Title VII

Extraterritorial Application in Light of Congress’

Clearly Expressed Concern With Fair Employment

Overseas ....................................................... 31

IV. Subsequent Legislation Also Demonstrates

Congress’ Intention To Provide Equal Employment

Opportunity for American Citizens in the

International Workplace ................................... 36

Conclusion ............................... 41

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Abrams v. Baylor College of Medicine, 805 F.2d 528 (5th

Cir. 1986) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18, 39

Alfred Dunhill of London v. Republic of Cuba, 425 U.S.

682 (1976) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

American Jewish Congress v. Arabian American Oil Co.,

No. C-4296-56 (N.Y. State Comm’n Against Discrimina

tion Jan. 26, 1959) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

American Jewish Congress v. Carter, 190 N.Y.S.2d 218,

221 (Sup. Ct. 1959), modified, 10 A.D.2d 833, 199

N.Y.S.2d 157 (App. Div. 1960), aff’d, 9 N.Y.2d 227, 213

N.Y.S.2d 60 (1961) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4, 10, 23, 24

Boureslan v. American Arabian Oil Co, 653 F. Supp. 629,

629 (S.D. Tex. 1987), aff’d 857 F.2d 1014, 1016 (5th Cir.

1988), vacated for rehearing en banc and aff’d, 892 F.2d

1271 (5th Cir. 1990) (en banc) . . . . . . . . . . . 18, 31

Diaz v. Pan American World Airways, 454 F.2d 234 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 950 (1971) . . . . . . . . 39

Espinoza v. Farah Manufacturing Co., 414 U.S. 86

(1973) .................... .. ................................. .. 33

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976) 11

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) . . . . 2

Pages:

Hardin v. City Title & Escrow Co., 797 F.2d 1037 (D.C.

Cir. 1986) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

House v. Commissioner, 453 F.2d 982 (5th Cir. 1972) 32

International Ass’n of Machinists v. OPEC, 649 F.2d 1354,

1358-61 (9th Cir. 1981) (same), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1163

(1982) ........................................ .. ................... .. 11

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ........... .. 2

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (19681)1

Regents v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) . . . . . . . . . 25

United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 103 (1979) . 13

Statutes and Resolutions:

29 U.S.C. § 213(f) .................................. .. 19

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................................................ 34

50 U.S.C. App. § 2402(5)(A) . ..................................... 36

50 U.S.C. App. § 2407(a) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37, 38

Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 701, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e . 33

Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 702, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-l . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31, 32, 34

Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 703, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2. 33

IV

S. Res. 323, 84th Cong., 2d Sess. (1956) . . . . 14-16, 22

Pages:

Legislative History:

102 Cong . Re c . 14330 (My 25, 1956) . . . . . . . . . 15

102 Cong . Rec . 14732 (My 26, 1956) . . . . . . . . . 16

102 Cong . Rec . 14733 (My 26, 1956) . . . . . . . . . 17

Civil Rights-Public Accommodations: Hearings on S. 1732

Before the Sen. Comm, on Commerce, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1963) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26-30

H.R. Rep. No. 190, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. (1977) 37, 40

S. Rep. No. 872, 88th Cong. 2d Sess. (1964) . . . . . 22

S. Rep. No. 2790, 84th Cong., 2d Sess. (1956) . . . . 15

Other Materials:

M. Borden, Jews, Turks, and Infidels (1984). . . . 14

Dudziak, Desegregation as a Cold War Imperative, 41 Stan.

L. Rev. 61 (1988). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Gold, Griggs’ Folly: An Essay on the Theory, Problems, and

Origins of the Adverse Impact Definition o f Employment

Discrimination and a Recommendation for Reform, 7 Indust.

Re l . L.J. 429 (1985). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

V

Letter from Secretary of State John Foster Dulles to Philip

Pages:

Klutznick, President of B’nai B’rith (Aug. 14, 1956) . . 23

Letter from Assistant Secretary of State William B.

Macomber, Jr. to Sen. E.L. Bartlett (July 29, 1959) . . 24

Note, Title VII and the Arab Boycott, 12 Harv. C.R.-C.L.

L. R e v . 181 (1977). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Street, Application o f U.S. Fair Employment Laws to

Transnational Employers in the United States and Abroad,

19 N.Y.U.J. In t ’l L. & Po l . 357 (1987). . . . . . . . . 18

No. 89-1838

No. 89-1845

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1990

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

Petitioner,

v.

Arabian American Oil Co .,

Respondent.

Ali Boureslan,

Petitioner,

v.

Arabian American Oil Co .,

Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE,

THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS,

THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B’NAI B’RITH,

AND THE WOMEN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

2

Interest o f Am ic i Cu ria e1

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

is a non-profit corporation that was established for the

purpose of assisting black citizens in securing their

constitutional and civil rights. This Court has noted the

Fund’s "reputation for expertness in presenting and arguing

the difficult questions of law that frequently arise in civil

rights litigation." NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422

(1963).

A significant portion of the Fund’s litigation has

concerned Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the

proper scope of constitutional and statutory rights to equal

employment opportunity. See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975). The Fund has long been committed

to the proposition that full equality of economic opportunity

requires applying prohibitions on discrimination in employ

‘Letters of consent to the filing of this Bnef have been filed with the

Clerk of Court.

3

ment to American corporations regardless of where such

discrimination occurs.

The American Jewish Committee ("AJC") is a national

membership organization, founded in 1906 to protect the

civil and religious rights of Jews. AJC has always believed

that these rights can be secure for Jews only if they are

equally secure for Americans of all faiths, races, and ethnic

backgrounds. AJC, therefore, has been actively involved in

the civil rights cause since its inception in the 1930s, and

strongly supported enactment of the Civil Rights Act of

1964. This organization has always urged that civil rights

laws be interpreted broadly to effectuate their purposes.

That is why AJC believes that Title VII should be

interpreted to apply to discrimination outside the United

States by an American corporation against an American

citizen employee.

The American Jewish Congress is a national

membership organization founded in 1918 for the

4

preservation of the security and the constitutional and civil

rights of Jews in America through guaranteeing the rights of

all Americans. Since 1959 when as a plaintiff in American

Jewish Congress v. Carter, 190 N.Y.S.2d 218, 221 (Sup.

Ct. 1959), modified, 10 A.D.2d 833, 199 N.Y,S.2d 157

(App. Div. 1960), aff’d, 9 N.Y.2d 227, 213 N.Y.S.2d 60

(1961), it successfully litigated under New York anti-

discrimination law to ban Aramco’s discriminatory

employment practices from New York State, the American

Jewish Congress has fought to assure equality of

employment opportunity for Americans both at home and

abroad. It has brought and successfully settled cases

involving fact patterns identical to those in the instant case.

It believes reversal of the decision below is necessary to

preserve the continued vitality of Title VII as a means to

prevent and remedy discrimination in employment against

Americans in the international work place.

5

The Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith (ADL) was

organized in 1913 to advance good will and mutual

understanding among Americans of all races a creeds, and

specifically to combat racial and religious discrimination

both in the United States and abroad. Among the many

activities directed towards these goals, in 1977 ADL fought

successfully for the passage of the antiboycott provisions of

the Export Administration Act (EAA), which prohibit U.S.

companies from discriminating against U.S. citizens in order

to comply with the Arab boycott of Israel and Israeli

interests. Subsequently, ADL filed amicus briefs in cases

involving a private right of action under the EAA, including

Abrams v. Baylor College of Medicine, 805 F.2d 528 (5th

Cir. 1986), and Bulk Oil (Zug) A.G. v. Sun Company, Inc.,

583 F. Supp. 1134 (S.D.N.Y. 1983), aff’d. 742 F.2d 1431

(2d Cir.), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 835 (1984). Moreover,

ADL has a consistent record of fighting employment

discrimination in a variety of domestic contexts, and has

6

filed amicus briefs in cases such as Hobbie v. Unemployment

Appeals Commission, 480 U.S. 136 (1987) (holiday

observance); Hishon v. King & Spaulding, 467 U.S. 69

(1984)(sex discrimination); and McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976) (racial

discrimination).

ADL submits the accompanying brief because we

believe this Court will decide the important issue of whether

an American who is the target of employment discrimination

by a U.S. company doing business abroad should be

afforded the same legal protection as one who is subject to

employment discrimination by a U.S. company doing

business in this country. ADL has a vital interest in

ensuring that Americans are protected from employment

discrimination both at home and abroad, and we therefore

support the extraterritorial application of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 with regard to Americans employed

by American companies.

7

The Women’s Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit, tax-

exempt membership organization, founded in 1971 to

provide pro bono legal assistance to victims of

discrimination based on sex. The Fund devotes a major

portion of its resources to combatting sex discrimination in

employment, through litigation of significant employment

discrimination cases, operation of an employment

discrimination counseling program, public education, and

advocacy before the EEOC and other federal agencies that

are charged with enforcement of equal employment laws.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

As early as 1956, Congress made clear its concern with

ensuring equal employment opportunities for American

citizens working abroad for American corporations. In

particular, the Senate passed a resolution stating that it was

against national policy for there to be distinctions based on

8

religion in the negotiations of trade agreements between the

United States and foreign nations. This historical

background must be considered in interpreting Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

II.

A specific purpose of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was

to promote nondiscrimination abroad. The ending of racial

discrimination within the United States was considered key

to enhancing America’s image and to affect discrimination in

other countries by setting a standard for the world.

III.

The language of Title VII supports the conclusion that

it applies to the employment practices of American

companies operating abroad. The Fifth Circuit’s

construction of the statute is artificially narrow and

inconsistent with the terms of the statute.

9

In subsequent legislation, Congress has demonstrated

its intention to provide equal employment opportunity for

American citizens working abroad. The Export

Administration Act expressly covers discrimination against

Americans by American corporations operating abroad. It

would be wholly inconsistent with Congress’ intent to give

Title VII a more limited scope.

IV.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

This is not the first time that respondent Arabian

American Oil Co. ("Aramco”) has sought to insulate its

treatment of American citizens from scrutiny under equal

employment opportunity laws by pointing to the international

nature of its business. Thirty years ago, Aramco argued that

its refusal to hire Jews should be immune from the reach of

a state antidiscrimination statute that served as one of the

10

models for Title VII2 because Jews were not permitted entry

into Saudi Arabia and because the Saudi government, on

whose good will Aramco was economically dependent,

disapproved of Aramco’s employing Jews anywhere. See

American Jewish Congress v. Carter, 190 N.Y.S.2d 218,

221 (Sup. Ct. 1959), modified, 10 A.D.2d 833, 199

N.Y.S.2d 157 (App. Div. 1960), aff’d, 9 N.Y.2d 227, 213

N.Y,S.2d 60 (1961) (rejecting Aramco’s position).

The argument accepted by the Fifth Circuit in this case

represents a significant expansion of this already-discredited

position, for the Fifth Circuit’s opinion gives American

companies a blanket license to discriminate in their overseas

operations as they see fit, regardless of the laws or customs

of other counties. The Fifth Circuit did not find that

Aramco’s discriminatory conduct is somehow required by a

foreign government. Thus, this case does not raise

2 See generally Gold, Griggs’ Folly: An Essay on the Theory,

Problems, and Origins o f the Adverse Impact Definition o f Employment

Discrimination and a Recommendation for Reform, 7 INDUST. REL. L J .

429, 568-73 (1985).

11

potentially troublesome issues concerning the act of state and

foreign compulsion doctrines. C f, e.g., Alfred Dunhill o f

London v. Republic o f Cuba, 425 U.S. 682, 705 n. 18

(1976) (plurality opinion) (discussing doctrines);

International Ass’n o f Machinists v. OPEC, 649 F.2d 1354,

1358-61 (9th Cir. 1981) (same), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1163

(1982). Rather, the Fifth Circuit excused an American

corporation from complying with a statute expressing our

Nation’s "highestpriority," Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

424 U.S. 747, 763 (1976) (quoting Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968)), because it assumed

that Congress failed to express an intention that Title VII

apply extraterritorially. See Boureslan v. Aramco, 892 F.2d

1271, 1273-74 (5th Cir. 1990) (en banc).

That assumption is critically flawed. It reflects an

improperly cramped view of the available evidence regarding

Congress’ concern with the overseas employment

opportunities of American citizens and the overseas em

12

ployment practices of American corporations. That evidence

clearly shows that Congress has long been concerned with

ensuring equal employment, opportunities for American

citizens in international commerce. In light of that evidence

and relevant principles of statutory construction, § 702

provides additional evidence that Title VII should be given

extraterritorial effect with regard to American citizens

employed by American companies.3

I. Title VII W as Enacted Against the Backdrop

o f Congress5 L ong-Standing C oncern W it h

Ensuring E qual Em ploym ent Opportunities in

International C om m erce fo r Am erican

Citizens

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was not passed in a

vacuum. To understand the scope Congress intended the Act

to have, one must examine Congress’ prior treatment of the

3 Judge King’s persuasive dissent and the arguments advanced by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the private petitioner

address in detail the general principles of statutory construction that

should govern this case and much of the relevant evidence in the

legislative history of Title VII. We do not repeat their analyses in this

brief.

13

question of discrimination abroad by American companies

against American citizens. Cf. United Steelworkers v.

Weber, 443 U.S. 103, 201 (1979) (Title VII must be

construed in "the historical context from which the Act

arose"). Examination of this issue strongly supports

extraterritorial application of Title VII, for, prior to the

passage of Title VII, Congress had expressed a forceful

commitment to eliminating employment discrimination

abroad against American citizens.

There are two distinct contexts in which employment

discrimination against Americans overseas might occur: (1)

the discrimination might be required by the laws of a foreign

government or (2) the foreign government might be neutral

as to the permissibility of such discrimination. Obviously,

the former situation presents a stronger argument for

confining American fair employment laws within United

States borders, since it involves a square conflict of laws and

sovereignty. Even in this more potentially troublesome

14

context, however, Congress has repeatedly manifest its

desire to extend principles of nondiscrimination in

employment as far as possible. Senate Resolution 323, 84th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1956), represents an express statement of

this congressional commitment to extraterritorial equal

employment opportunity.

During the 19505s, Congress became increasingly

concerned with the refusal of American corporations doing

business with the Arab world to hire American Jews.4 In

1956, the Senate unanimously passed a resolution

condemning discrimination in overseas employment on the

basis of religion:

Whereas the protection of the integrity of

United States citizenship and of the proper rights of

United States citizens in their pursuit of lawful

trade, travel, and other activities abroad is a

principle of United States sovereignty; and

Whereas it is a primary principle of our

4 This was not, however, the first time Congress had expressed this

concern. As early as the 1850’s, Congress had passed resolutions urging

other nations not to discriminate among American citizens on the basis

of religion, and had refused to accept foreign commerce treaties that did

not provide for nondiscrimination among American citizens. See M.

Borden, Jews, Turks, and Infidels 82-88, 94-96 (1984).

15

Nation that there shall be no distinction among

United States citizens based on their individual

religious affiliations and since any attempt by

foreign nations to create such distinctions among

our citizens in the granting of personal or

commercial access or any other rights otherwise

available to United States citizens generally is

inconsistent with our principles; Now, therefore, be

it

Resolved, That it is the sense of the Senate

that it regards any such distinctions directed against

United States citizens as incompatible with the

relations that should exist among friendly nations,

and that in all negotiations between the United

States and any foreign state every reasonable effort

should be made to maintain this principle.

S. Res. 323, 84th Cong. 2d Sess. (1956) {quoted in 102

Co n g . Re c . 14330 (July 25, 1956)).

The discussion on the floor of Senate Resolution 323

further illustrates Congress’ desire to assure that American

citizens abroad enjoy, to the maximum extent possible, the

same equal employment opportunity they enjoy within the

United States.5 Senator Lehman (D.-N.Y.), the primary

5 The Committee on Foreign Relations recommended passage of the

resolution without objection. The committee report that accompanied the

resolution, S. Rep . No. 2790, 84th Cong., 2d Sess. (1956), stated

succinctly that "[t]he resolution speaks for itself."

16

sponsor of S. Res. 323,6 stated that the purpose of the

resolution was to prevent foreign employment practices, even

those compelled by foreign governments, from making

"second-class citizens of some . . . Americans . . . 102

C o n g . R e c . 14732 (July 26, 1956).7 He explained that the

resolution should govern the negotiation of trade agreements

to make sure that such agreements

expressly provide that no United States citizen

shall, solely because of religious affiliation or

derivation, be denied the advantages o f . . .

employment. . . or any other benefit made possible

by such treaty, convention or agreement.

Id. (Emphasis added.)

Two of Senator Lehman’s remarks are particularly

salient to the issue now before this Court. First, Senator

6 Sen. Lehman received unanimous consent to put his testimony in

the record "to supplement the language of the resolution itself.” 102

Cong. Rec . 14732 (M y 26, 1956).

7 Several senators who spoke in favor of the resolution stated that

the integrity of United States sovereignty and citizenship would be

compromised if Americans overseas were subject to discrimination in

employment on the basis of religion. See, e.g., id. at 14731 (M y 26,

1956) (statement of Sen. Morse); id. at 14733 (statement of Sen. Neu-

berger); id. (statement of Sen. Humphrey).

17

Lehman expressly linked the application of principles of non

discrimination to foreigners within the United States to the

United States’ right to insist that American citizens be

treated fairly abroad. Id. at 14733; see also id. (statement

of Sen. Morse) (resolution "will demonstrate once again —

and it is time we made it clear — that a basic idea of

America, not only in foreign relations, but in domestic

policy, is that there can be no question raised as to the rights

of our citizens based upon religious faith.").

Second, Senator Lehman recognized the potential

domestic effect of sanctioning discrimination abroad. Id. In

order to assure nondiscrimination at home by transnational

employers it would be necessary to press for

nondiscrimination abroad.

The phenomenon identified by Senator Lehman—the

interdependence of the domestic and international

employment markets—is especially important in

understanding how the Fifth Circuit’s interpretation threatens-

18

to undermine Congress’ intentions in enacting Title VII.

Title VII was intended to expand the employment

opportunities available to racial, ethnic, and religious

minorities and to women. In today’s multinational

economy,8 an individual’s advancement within a corporation

may often be dependent on training, experience, and contacts

that occur abroad. See, e.g., Abrams v. Baylor College of

Medicine, 805 F.2d 528, 530 (5th Cir. 1986) (higher

incidence of certain heart diseases in Saudi Arabia meant

that cardiologists who spent time in program run by Baylor

there received "a greater opportunity for clinical experience

. . . than is generally available in America"). Moreover,

many decisions regarding positions abroad are in fact made

in the United States. See, e.g., Boureslan v. American

Arabian Oil Co, 653 F. Supp. 629, 629 (S.D. Tex. 1987),

aff’d 857 F.2d 1014, 1016 (5th Cir. 1988), vacated for

8 See, e.g., Street, Application of U.S. Fair Employment Laws to

Transnational Employers in the United States and Abroad, 19 N.Y.U.J.

Int’l L. & Pol. 357, 358 (1987) (2000 U.S. firms operate 21,000

foreign subsidiaries in 121 countries).

19

rehearing en banc and aff’d, 892 F.2d 1271 (5th Cir. 1990)

(en banc) (Boureslan requested and was given a transfer to

Aramco and its Saudi operations while he was working at

ASC in Houston, Texas). If racial, religious, and ethnic

minorities or women lose their right to fair treatment

whenever they spend time working for their American

employer’s overseas operations, they face a Hobson’s

choice. If they choose not to take jobs that require working

abroad9 in order to remain under Title VIPs protection, they

will be less competitive in seeking jobs within the United

States because they will lack the experience and contacts that

persons who have taken such jobs obtain. If, on the other

hand, they take overseas positions, they may be discriminat

9 This may even preclude accepting assignments that require

protracted overseas travel. The stringent territorial restriction of Title

VII required by the panel’s interpretation might mean, for example, that

sexual harassment of a female employee on a two-week business trip to

Asia would be beyond the reach of Title VII even though both the super

visor and the victimized subordinate are American citizens employed by

an American corporation in an American office. Cf. 29 U.S.C. § 213(f)

(Fair Labor Standards Act does not apply to "any employee whose

services during the work week are performed in a workplace within a

foreign country").

20

ed against as soon as they arrive on foreign soil. If they are

fired, or harassed into quitting, by discrimination that would

be forbidden if it occurred within the United States, the

termination of their relationship with the American-based

employer will preclude their later moving up the corporate

ladder into domestic positions.

Moreover, if a substantial number of potential

employees refuse to work overseas because to do so would

strip them of fundamental protections, employers may have

to pay a premium to induce potential employees to work

abroad. White Anglo-Saxon male workers will benefit

disproportionately from such a premium, since they will be

less likely to be at risk of discrimination. Ultimately they

will receive both a direct premium - from accepting

overseas assignments — and an indirect competitive

advantage against their minority or female competitors who

have not received the training or experience acquired from

overseas employment.

21

Finally, the Fifth Circuit’s approach creates a massive

loophole for companies that wish to circumvent Title VII.

In essence, it permits employers to "launder" their

discrimination just as offshore banks permit criminals to

"launder" illegally acquired funds. For example, a company

that wants to fire a female employee need only transfer her

to an overseas office. It can then terminate her without

facing Title VII liability. Even the threat of being sent

overseas, when coupled with the likely prospect of

harassment or discharge without redress under Title VII may

cause an employee’s resignation or acquiescence in

discriminatory treatment. For example, a company that

wishes to exclude women from certain positions in its United

States operations may be able to induce female employees to

refrain from seeking the positions by requiring all employees

seeking the position to serve overseas and by doing nothing

22

to discourage sexual harassment in its operations abroad.10

S. Res. 323 reflected a broad consensus within the

legislative and executive branches regarding equal

employment opportunities in international commerce.11

10 The Fifth Circuit’s opinion poses another potential threat to

employment opportunities within the United States. To the extent that

American companies believe they can reduce costs by exporting

American jobs overseas, they will do so. The effect will be to diminish

the number of available domestic jobs. To the extent that a corporation

views compliance with principles of fair employment as a cost, releasing

the company from compliance with those principles creates an incentive

for the company to move those jobs offshore even when it continues to

fill the jobs with American citizens. The net result is either that it will

then not hire protected groups to fill the jobs or that it will not give those

groups the protection they would enjoy in domestic employment

situations. In either event, those groups’ employment opportunities will

be diminished. In short, the Fifth Circuit has created an incentive for

American companies to export American jobs.

11 The 1956 platforms of both political parties expressed similar

sentiments. The Democratic platform stated that "We oppose, as

contrary to American principles, the practice of any government which

discriminates against American citizens on grounds of race and religion.

We will not countenance any arrangement or treaty with any government

which by its terms or in its practical application would sanction such

practices." The Republican platform stated that "We approve appropri

ate action to oppose the imposition by foreign government of discrimina

tion against United States citizens based on their religion or race."

Quoted in American Jewish Congress v. Arabian American Oil Co. , No.

C-4296-56 (N.Y. State Comm’n Against Discrimination Jan. 26, 1959).

Cf. S. REP. No. 872, 88th Cong. 2d Sess. (1964), reprinted in 1964

U.S. Cong. Code & Ad . News 2355, 2362-63 (Senate report

accompanying Civil Rights Act of 1964 quotes 1960 platforms of

Democratic and Republican parties to show national commitment to

"equal opportunity and elimination of racial discrimination").

23

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles responded to questions

about the opportunities of American Jews to work abroad by

writing that " [i]t is the policy of the Department of State not

to acquiesce in any discriminatory practices, but to point out

to the leaders of the Arab states the equality of all

Americans irrespective of race or creed under the

Constitution and laws." Letter from Secretary of State John

Foster Dulles to Philip Klutznick, President of B’nai B’rith

(Aug. 14, 1956), quoted in American Jewish Congress v.

Arabian American Oil Co., No. C-4296-56 at 6-7 (N.Y.

State Comm’n Against Discrimination Jan. 26, 1959).12 The

Department reiterated this position in a 1959 letter written to

Senator E.L. Bartlett regarding the then-pending American

Jewish Congress v. Carter litigation:

12 The letter continues: "We in the Department of State are

particularly anxious to do what we can to insure that United States

citizens in pursuit of legitimate trade, travel and other activities abroad

will not face distinctions of the kind of which you write. Our posts in

countries where discriminatory practices are followed have also been

instructed to point out the strong feelings of the American public and of

the Congress in this matter." Id. at 7.

24

[T]he proper policy of our Government must be to

work for the elimination of any procedures adopted

by foreign states which tend to discriminate against

our citizens in any way, including discrimination

on the basis of race or religion.

Letter from Assistant Secretary of State William B.

Macomber, Jr. to Sen. E.L. Bartlett (July 29, 1959), quoted

in Brief of Petitioner-Respondent at 64, American Jewish

Congress v. Carter, 199 N.Y.S.2d 158 (App. Div. 1960).

In sum, the enactment of Title VII must be viewed

against the backdrop of the Senate’s desire that Americans

abroad be protected by the right to equal treatment they

enjoyed at home. The discussion surrounding the unanimous

passage of Resolution 323 and widespread concern with

overseas employment opportunities for American religious

minorities in the decade preceding the passage of Title VII

strongly suggest that when Congress expanded federal

protection of employment rights in 1964, it intended that the

new protections, like their predecessors, extend to

Americans overseas.

25

II. One of the P urposes o f the Civil R ig h ts Act of

1964 W as T o P rom ote Nondiscrimination

Abroad

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 represented a

comprehensive attack on the problems of prejudice in public

accommodations, employment, access to governmental

services, and voting. Thus, the legislative, history of the

various titles can contribute to an understanding of the

proper scope to be afforded particular provisions. Cf. e.g.,

Regents v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 353 (1978) (opinion of

Brennan, White, Marshall, & Blackmun, JJ.) (interpreting

Titles VI and VII in tandem).

The testimony presented in support of the public

accommodations provisions of the Act by Secretary of State

Dean Rusk demonstrates the Administration’s intention that

the enactment of antidiscrimination legislation in the United

States serve to expand protections against discrimination

abroad.

26

The fact that racial discrimination within the United

States had injured America’s image and impaired the conduct

of its foreign relations had long been recognized. See

generally Dudziak, Desegregation as a Cold War Imperative,

41 Stan . L. Re v . 61 (1988) (discussing foreign reactions to

racial discrimination in employment, education, and public

accommodations, and federal government’s response to these

reactions). But Secretary Rusk went beyond seeking a

public accommodations law to eliminate damaging episodes

of racial discrimination against foreign diplomats traveling in

America. See, e.g., id, at 90-92; Civil Rights-Public

Accommodations: Hearings on S. 1732 Before the Sen.

Comm, on Commerce, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 283-87 (1963)

(statement of Secretary Rusk). He argued instead that the

foreign affairs implications of such a law extended to its

potential effect on discrimination in other countries. For

example, he suggested that the United States’ treatment of

foreigners should "se[t] a standard for all the world." Id. at

27

283. In addition, he echoed the theme of interdependence

identified above:

For example, the Department of State has a duty to

assist and protect American citizens traveling

abroad-and without regard to race, religion, or

national origin of the particular American citizen.

Now, against a background of, shall I say,

disability in our own country on some of these

same issues, our voice abroad, in seeking to protect

American citizens abroad, is somewhat muted and

uncertain. And I think this affects the elements of

reciprocity under the conduct of our foreign

relations as well as the broader issues in what

might be called the propaganda and political field.

Id. at 290. Thus, Secretary Rusk both identified the United

State’s pre-existing commitment to assuring equal protection

for American citizens overseas and recognized the effect

domestic treatment might have on the conduct of foreign

affairs. The latter point further highlights the propriety of

giving Title VII extraterritorial effect: foreigners’ closest

exposure to American principles of nondiscrimination is

likely to come when those principles are demonstrated to

28

them in their own country.13

In addition, Secretary Rusk explicitly made the point

that American laws might affect laws overseas. Senator

Thurmond referred to Secretary Rusk’s statement that racial

discrimination was not unique to the United States but

occurred in many countries, and asked the Secretary in light

of that fact and the proposed Title VI (which denies federal

funds to institutions that discriminate) whether foreign aid

should be denied to other nations that discriminated. The

Secretary recognized that "[w]hen we are dealing with the

rest of the world we are dealing with a world which we can

influence, but cannot control," and thus that cutting off aid

might be a counterproductive strategy for influencing other

nations. But he went on to state that:

In the rest of the world we are waging a

struggle for freedom. . . . We must stay with that

struggle, use our influence to the best of our ability

to sustain and strengthen the cause of freedom; and

13 Thus, for example, American principles of racial equality were

powerfully demonstrated by the appointment of a black ambassador to

South Africa.

29

that would mean we would work at it, use our

influence, even though we can’t necessarily control

the result.

Our influence in these situations can be very

strong. I think there are differences between

situations where governmental laws and

constitutional practices are responsible for the

discrimination, and where you run into

discriminatory situations simply because of the

existence of religious and racial groups next to each

other, with the social problems that have

historically been associated with those situations.

Our influence has been in the direction offJ

removing these discriminations abroad as well as at

home.

I think our advice in this respect would be

more powerful if we could move forward at home

more rapidly.

. . . I do not think we should abandon the

great struggle for freedom throughout the world .

Id. at 299. (Emphasis added.)

In light of Secretary Rusk’s testimony, the committee

chairman, Senator Warren Magnuson stated that

discrimination abroad should not lead the United States to

"abandon our purpose to show the world the kind of

leadership that would erase discrimination in the world." Id.

at 306. He concluded:

30

Our positive action toward a firm national

policy on this is going to be very helpful to

the people in other countries who want to

abolish this sort of thing in their countries.

Id. (emphasis added).

Congress chose to give extraterritorial effect to Title

VII because to do so clearly would serve the central foreign

policy goals connected with the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

By providing an illustration of the scope of American fair

employment law within foreign territories, it would

graphically demonstrate the level of American commitment

to ideals of nondiscrimination. Moreover, it would also

provide an incentive for foreign citizens to press their

governments to institute similar guarantees.

31

m . Section 702 Should Be Construed To G ive

Titl e VII E xtraterritorial Applicatio n in

Lig h t of Congress’ Clearly E xpressed

C oncern W it h F air Em ploym ent O verseas

The Fifth Circuit rejected the argument that section

702, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-l, indicates Congress’ intention to

give Title VII extraterritorial effect. It held instead that

section 702 was intended to ensure the extension of Title

VIPs protection to aliens working within the United States.

See Boureslan, 892 F.2d at 1274. This artificially narrow

interpretation substantially distorts the statutory framework.

The section provides:

§ 702. Exemptions

This Title shall not apply to an employer with

respect to the employment of aliens outside any

State, or to a religious corporation, association,

educational institution, or society with respect to

the employment of individuals of a particular

religion to perform work connected with the

carrying on by such corporation, association,

educational institution, or society of its activities.

The first thing to note about section 702 is its

descriptive subheading: "Exemptions." See Hardin v. City

32

Title & Escrow Co., 797 F.2d 1037, 1039 (D.C. Cir. 1986)

(description of statutory provision contained in subheading

that appears in enactment itself "constitutes an indication of

congressional intent"); House v. Commissioner, 453 F.2d

982, 987 (5th Cir. 1972) (subheadings may aid courts in

”com[ing] up with the statute’s clear and total meaning").

Had Congress intended the interpretation given by the court

below, it would have made far more sense to place the

discussion of the rights of aliens in a section entitled

"Inclusion of Aliens."

The fact that Title VII’s applicability to religious entities

appears in the same section further strengthens this

conclusion. The meaning of section 702 with respect to

religious institutions employing more than a specified

number of workers is clear: absent the section, Title VII

would cover them.14 A similar interpretation should be

14 Surely, the court of appeals would not have interpreted the latter

part of section 702 as indicating the kind of employers (i. e. , groups that

are not "religious corporation[s], association^], educational institutions],

or societies]") to which Title VII was intended to apply.

33

given to the part of section 702 dealing with aliens: absent

section 702, any employer falling within the definitional

provisions of sections 701(a), (b), (g), and (h) -- that is, a

sufficiently large employer engaged in specified types of

commerce — would be subject to Title VII with respect to all

its employees, including all aliens.

Section 703 gives additional support to this view.

Section 703 protects "individuals]." It does not limit its

protection to citizens. Thus, had there been no mention of

aliens in section 702, Title VII would still have protected

aliens to the same extent it protected citizens.15 Congress

clearly understands the difference between providing

protection to individuals and to citizens. See, e.g., 42

15 Espinoza v. Farah Manufacturing Co., 414 U.S. 86, 95 (1973),

is not to the contrary. There, this Court drew a "negative inference"

from section 702 that aliens employed within the United States were

covered. In other words, this Court held that a decision to exempt aliens

in certain circumstances necessarily implied that they were not exempted

in other circumstances.

The court of appeals’ statement regarding Boureslan’s attempt to

draw a "negative inference" misperceives the nature of such an inference.

The argument in favor of extraterritorial application does not depend on

a negative inference. Rather, the fact that an exemption is created

suggests that there is something from which exemption is necessary.

34

U.S.C. § 1981 {"[a]llpersons within the jurisdiction of the

United States shall have the same right" with regard to

certain activities "as is enjoyed by white citizens") (emphasis

added). Indeed, the heightened scrutiny to which

distinctions based on alienage are subject, see, e.g., Graham

v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365, 372 (1971), suggests that

courts should be loath to adopt an interpretation of a statute

that makes such a distinction in the absence of a clear

congressional intention to do so. In short, the purpose of

section 702 cannot have been to include domestic aliens

within Title VII’s protections.

Finally, the congressional and executive concerns with

ensuring equality for all Americans in the international

workplace and fostering nondiscrimination throughout the

world strongly counsel interpreting section 702 as a narrow

exemption from Title VII’s commands rather than as a broad

exemption. The justification for any alien exemption must

lie in the potential conflict of laws that applying American

35

antidiscrimination law might create. Applying American

laws abroad only when both parties to the employment

relationship are American citizens - that is, adopting the

position advanced in this brief — represents the most

reasonable accommodation of these competing concerns. In

cases involving two American entities, there is a far greater

federal interest in applying United States statutes.

Moreover, traditional principles of international law

regarding acts of state and foreign compulsion remain

available to alleviate particular conflicts. Thus, this Court

should conclude that, in including section 702 within Title

VII, Congress intended only to reduce the potential for

statutory conflict by exempting a class of workers from Title

VII’s ambit as to whom the United States had a less

significant relationship. Congress intended, however, to

provide the maximum possible equal employment

opportunity to each American citizen.

36

IV. Subsequent Legislation Also Demonstrates

Congress5 Intention T o P rovide E qual

Em ploym ent Opportunity fo r Am erican

Citizens in the International W orkplace

On several occasions subsequent to the original passage

of Title VII, Congress has addressed the issue of equal

economic access to the international marketplace for all

Americans regardless of their ethnic or religious background.

In particular, Congress’ treatment of the Arab boycott

buttresses the conclusion that Title VII was intended to have

extraterritorial effect. See generally, Note, The Arab

Boycott and Title VII, 12 H a r v . C.R.-C.L. L. Re v . 181

(1977).

The Congressional declaration of policy accompanying

the Export Administration Act states, among other things,

that "[i]t is the policy of the United States . . . to oppose

restrictive trade practices or boycotts fostered or imposed by

foreign countries against . . . any United States person . . .

50 U.S.C. App. § 2402(5)(A). The Act requires the

president to issue regulations prohibiting any United States

37

"person" (which includes any American corporation) from

Refusing, or requiring any other person to refuse,

to employ or otherwise discriminating against any

United States person on the basis of race, religion,

sex, or national origin of that person or of any

owner, officer, director, or employee of such

person.

Id. § 2407(a)(1)(B).

The legislative history of the Export Administration

Amendments of 1977 expressly states that boycotts of U.S.

companies "because of race, religion, or national origin . .

. . [are] clearly against the spirit and intent of U.S. law,

including the civil rights and equal opportunity laws," and

that the prohibition against discrimination in the Export

Administration Act is intended to apply to "U.S.-controlled

subsidiaries and affiliates abroad" except when there would

be an "intractable conflict . . . with specific laws of foreign

countries . . . H.R. Rep. No. 190, 95th Cong., 1st Sess.

51 (1977).

The exemption contained in the Act provides an ap

propriate model for construing Title VII’s extraterritorial

38

effect. The Export Administration Act does provide an

exemption for "compliance by a United States person

resident in a foreign country or agreement by such person

to comply with the laws of that country with respect to his

activities exclusively therein." Id. § 2407(a)(2)(F). But that

exemption is far narrower than the exemption judicially

granted by the Fifth Circuit in this case. Note that the

Export Administration Act exemption does not protect

American employers when they choose to discriminate in a

foreign country which does not affirmatively require such

discrimination. In short, it merely codifies the defense of

foreign compulsion. In this case, by contrast, there is no

claim that Saudi Arabia required the harassment of

Lebanese-American employees. And the Export

Administration Act expressly provides that " [njothing in this

subsection may be construed to supersede or limit the

operation of the antitrust or civil rights laws of the United

States." Id. § 2407(a)(4).

39

Moreover, such a model would also be consistent with

this Court’s longstanding approach to another limitation on

the scope of Title VII, the bona fide occupational

qualification (BFOQ). See Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S.

321, 334 (1977) (the BFOQ "is an extremely narrow

exception"); see also Abrams, 805 F.2d at 533 n. 7

(interpreting BFOQ to avoid collision with Export

Administration Act); Diaz v. Pan American World Airways,

454 F.2d 234 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 950

(1971)(Title VIPs broad remedial purposes are best served

by reading any restrictions on the extent of its protections as

narrowly as possible). In this case, this principle is best

served by holding that Title VII does have an extraterritorial

effect.

Thus, the Export Control Act and Congress’ treatment

of the Arab boycott in the legislative history show a

profound congressional desire that American companies,

including American companies operating abroad adhere to

40

the maximum extent possible to American principles of

nondiscrimination. They represent the latest expression of

a principle that has consistently been expressed since the

1950’s. This pervasive concern with "’the right of

Americans to engage in international commerce without

being subjected to discrimination,’" H.R. Rep. 190 at 47

(additional views of Rep. Benjamin S. Rosenthal) (quoting

President Jimmy Carter), militates strongly in favor of

construing Title VII to have an extraterritorial effect.

The Export Control Act shows that Congress does not

believe that American foreign policy objectives will be

compromised by a general insistence that American

corporations comply with principles of nondiscrimination.

Indeed, it shows Congress’ intention that these principles be

limited only when they cause an irreconcilable conflict. This

Court should interpret Title VII’s extraterritorial effect in a

parallel manner and deny American companies a blanket

license to discriminate against American citizens overseas.

41

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, this Court should reverse the

decision of the Fifth Circuit and hold that petitioners have

stated a cause of action under Title VII.

Pamela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

AMY ADELSON

Lois Waldman

Marc D. Stern

American Jewish

Congress

15 East 84th Street

New York, N.Y. 10028

(212) 879-4000

Ruth L. Lansner

Steven M. Freeman

Jill L. Kahn

The Anti-Defamation League

of B’nai B’rith

823 United Nations Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10017

(212) 490-2525

* Counsel of Record

Respectfully submitted,

Julius LeVonne Chambers

^Charles Stephen Ralston

The NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Samuel Rabinove

The American Jewish

Committee

165 E. 56th Street

New York, N.Y. 10022

(212) 751-4000

Donna R. Lenhoff

Women’s Legal Defense

Fund

2000 P Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 887-0364

Attorneys for Amici Curiae