Osborne v. Purdome Petitioners' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Osborne v. Purdome Petitioners' Brief, 1951. b2d1f175-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/28b76a08-eae0-4838-bca2-6691ba42ad70/osborne-v-purdome-petitioners-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

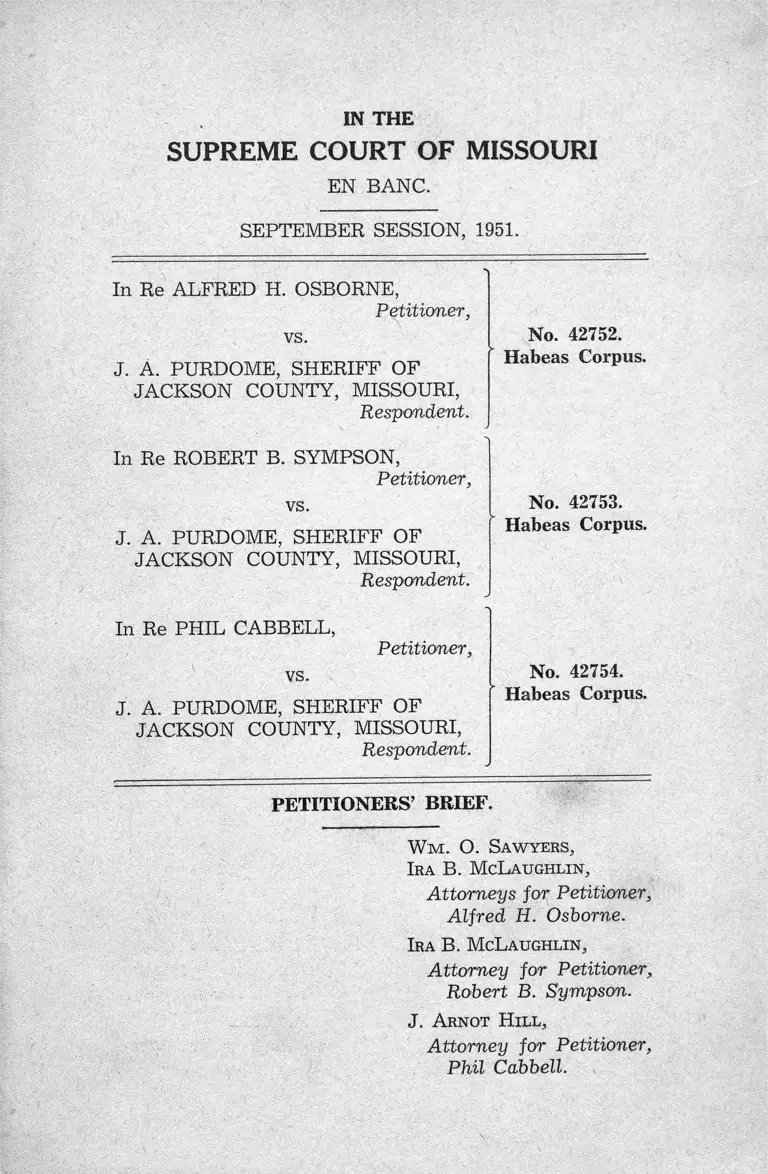

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI

EN BANC.

SEPTEMBER SESSION, 1951.

In Re ALFRED H. OSBORNE,

Petitioner,

vs.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent,

No. 42752.

Habeas Corpus.

In Re ROBERT B. SYMPSON,

Petitioner,

vs.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent.

No. 42753.

Habeas Corpus.

In Re PHIL CABBELL,

Petitioner,

vs.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent.

No. 42754.

Habeas Corpus.

PETITIONERS’ BRIEF.

W m . 0. Sawyers,

Ira B. McLaughlin,

Attorneys for Petitioner,

Alfred H. Osborne.

Ira B. McLaughlin,

Attorney for Petitioner,

Robert B. Sympson.

J. A rnot H ill,

Attorney for Petitioner,

Phil Cabbell.

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI

EN BANC.

SEPTEMBER SESSION, 1951.

In Re ALFRED H. OSBORNE,

Petitioner,

vs.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent.

No. 42752.

Habeas Corpus.

In Re ROBERT B. SYMPSON,

Petitioner,

vs.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent.

No. 42753.

Habeas Corpus.

In Re PHIL CABBELL,

Petitioner,

vs.

J. A. PURDOME, SHERIFF OF

JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI,

Respondent.

No. 42754.

Habeas Corpus.

PETITIONERS’ BRIEF.

Foreword.

1. The answers of the petitioners to the returns of the

respondent, paragraph VIII, page 9, make reference to a

duly certified copy of the complete record of cause num-

2

bered 551,348 in the Circuit Court of Jackson County, Mis

souri.

2. Pursuant to the stipulation of counsel on page 10

of said answers said record was duly filed with the clerk

of this court in cause numbered 42,752 and may be con

sidered as filed in causes numbered 42,753 and 42,754.

3. References in briefs of counsel to the transcript of

the complete record refer to the machine numbers at the

bottom of each page.

4. Informant’s Exhibit 4 received in evidence at page

207 of said transcript consists of the complete transcript of

the record in cause numbered 527,724 in said Circuit Court,

styled Robert M. Burton vs. Lloyd Moulder.

5. On page 576 of said transcript counsel have stipu

lated that the complete transcript of the record in this

court in cause numbered 42,456, styled Robert M. Burton,

appellant, vs. Lloyd Moulder, respondent, is a copy of the

complete transcript of the record in said cause 527,724 in

said Circuit Court; that the record of said cause in this

court shall be considered as and for said Exhibit 4 and

that the said exhibit need not otherwise be reproduced.

GROUNDS OF JURISDICTION.

1. These are Habeas Corpus actions to release peti

tioners from illegal imprisonment. The pretext therefor

is that they are restrained under the authority of a com

mitment for criminal contempt of court. Jurisdiction is

vested in this court by:

Article V, Section 4, Constitution of Missouri.

3

2. A full review of criminal contempt proceedings is

afforded in this court by Habeas Corpus,

Ex parte Howell,

273 Mo. 96; 200 S. W. 65

Ex parte Clark,

208 Mo. 121; 106 S. W. 990

Ex parte Creasy,

243 Mo. 679; 148 S. W. 914

Ex parte O’Brien,

127 Mo. 477; 30 S. W. 158

State ex rel Thompson vs. Rutledge,

332 Mo. 603; 59 S. W. (2d) 641

3. Such review involves the question whether, under

the facts and the law, the judgment rendered in the case

was warranted.

Ex parte Creasy, supra

STATEMENT.

On the 20th day of June, 1951 the above petitioners

filed in this court their petitions for Habeas Corpus, seek

ing to be released from allegedly illegal imprisonment by

J. A. Purdome, Sheriff of Jackson County, Missouri. Writs

of Habeas Corpus duly issued, service thereof and the pro

duction of the bodies of petitioners in this court were duly

waived, petitioners were ordered released on bail pendente

lite and appearance bonds duly approved.

The returns of respondent revealed that petitioners

were imprisoned by him under and by virtue of a judgment

and commitment entered and issued on the 18th day of

June, 1951 by Division No. 4 of the Circuit Court of Jack-

son County, Missouri (Honorable Thomas R. Hunt, Judge),

in a certain cause in said court, numbered 551348 and en

titled State of Missouri ex inf., Henry H. Fox, Jr., Prose

4

cuting Attorney of Jackson County, Missouri, Informant

and Complainant, vs. Alfred H. Osborne, Robert B. Symp-

son, J. Carl James, Phil Cabbell, Matt Jones and Vernon

Everage, Contemnors. A copy of said judgment and com

mitment accompanied each of said returns.

Petitioners, by duly verified answers, alleged facts

and grounds to show that their detention and imprison

ment was unlawful and that they were entitled to be dis

charged. Among the grounds so alleged are the points re

lied on and the specifications of error, infra. To said an

swers the respondent filed his separate demurrers.

A certified transcript of the complete record of said

Circuit Court in said contempt proceeding is by stipulation

(Tr. 576) and by reference in said answers made a part of

the within record. These three Habeas Corpus actions

were consolidated by order of this court.

The transcript of the proceedings in the Circuit Court

reveals that on the 27th day of April, 1951, an unverified

document called a “ Complaint for Criminal Contempt”

and entitled as aforesaid, was filed in the office of the

Clerk of the Circuit Court of Jackson County, Missouri

(Tr. 1-4). Thereupon the cause was by the Assignment

Division No. 8 of said court (Honorable Paul A. Buzard,

Judge) assigned to Division No. 4. The said order of as

signment (Tr. 5-6) recites that Division No. 4 only had

jurisdiction to entertain proceedings to punish the con

tempt alleged (Tr. 6). On said date a rule to show cause

was issued by said Division No. 4 (Tr. 6-7) and on the 25th

day of May, 1951, these petitioners and the other accused

appeared and the trial of said proceeding was begun.

Petitioners filed and presented petitions and affidavits

seeking to disqualify the Honorable Thomas R. Hunt, Cir

5

cuit Judge, and praying that another Circuit Judge be sub

stituted in his stead (Tr. 8, 110-112; 19, 114-116; 28, 127-

129). Said petitions were denied (Tr. 8, 19, 28, 121, 126).

Petitioners filed and presented to said court their motions

to dismiss the rule to show cause and therein asserted that

said complaint was wholly insufficient (Tr. 10, 20, 29).

These motions were overruled (Tr. 9, 19, 28, 146, 178).

Petitioners then filed their separate answers, on oath, de

nying all matters and things charged in said complaint as

constituting contempt (Tr. 9, 12-15; 19, 22-24; 28, 32-33).

Petitioners then filed their separate motions for judgment

on the pleadings, praying to be discharged of and from the

charge of contempt (Tr. 9, 16-18; 19, 25-27; 28, 34-36),

which said motions were overruled (Tr. 9, 19, 28, 164,

179).

Over the objection of petitioners (Tr. 186-188) ex

traneous evidence was received in an effort to establish

the truth of the allegations of the complaint and to dis

prove and impeach the allegations of said answers.

The order appointing amici curiae (Inf. Ex. 1; Tr.

190), the report of amici curiae (Inf. Ex. 2; Tr. 192-193)

and the order empowering the amici curiae to assist in

representing the State of Missouri and empowering them

and the prosecuting attorney to “ decide whether reason

able cause exists” for the institution of criminal contempt

proceedings and if such reasonable cause was by them so

found, to institute the same (Inf. Ex. 3; Tr. 194-195) were

received in evidence. The entire transcript on appeal in

the case of Burton vs. Moulder (Inf. Ex. 4; Tr. 207) was

introduced in evidence (See stipulation, Tr. 576). The

transcript on appeal in cause No. 42456 in this court is a

duplicate of said exhibit and referred to in lieu of repro

ducing the same in the transcript of the contempt proceed

ing. Informant’s Exhibits 5 and 6 (Tr. 199, 200, 215, 216-

6

218) constitute a duplicate original of the carbon copy of

the original petition, as amended by longhand interline

ation and the original petition, respectively, filed on the

9th day of April, 1948, in the case of Robert M. Burton

vs. Lloyd Moulder, Circuit Court No. 527724, bearing the

signatures of J. Carl James and Chester H. Loughbom

only as attorneys for plaintiff. The longhand writing on

Exhibit 5 was made by Robert B. Sympson on the 27th

day of September, 1950, the first day of the trial of said

Burton vs. Moulder (Tr. 200-203); see also exhibit 4, pp.

6a-6d). The said original petition so filed by J. Carl James

and Chester H. Loughbom, attorneys, alleged that the de

fendant “ drove his said automobile at a high and danger

ous rate of speed, to-wit: 60 or 70 miles an hour.” In

formant’s Exhibit 8 (Tr. 264-265) is a listing card, listing

the Case of Burton vs. Moulder for trial. The cause was

listed by J. Carl James and the only attorneys listed as

representing plaintiff at that time were J. Carl James and

Chester Loughbom. The filing stamp on the back thereof

is dated March 10, 1949.

The witness, Vernon Everage, (Tr. 227) was jointly

charged with petitioners and others (Tr. 2); no disposi

tion had been made of his case when his testimony was

given. Prior to the same being received, the objection

was made that, by reason of the fact that he was jointly

charged and that the case as to him had not been disposed

of, he was an incompetent witness. The objection was

overruled (Tr. 227).

Everage testified that he was a witness in the trial of

Burton vs. Moulder on Friday (Tr. 229, 231), the 29th day

of September, 1950 (See Exhibit 4, Transcript in Cause

No. 42456 in this court, page 193); that on the preceding

Wednesday, about 7:00 o’clock P. M. he talked to Osborne

7

and Sympson, who were in a car parked near the front

of his home (Tr. 270); that he did so at the request of

Jones; that Osborne, Sympson, Jones and Cabbell were in

the car (Tr. 236); that Osborne asked him to testify to an

accident that happened in the Fairfax District; that he

knew nothing about the accident; that Osborne said he

would tell him how the accident happened and what he

was to say (Tr. 238); that he made and kept an engage

ment to meet Sympson in the Fairfax District, in front of

the General Motors plant where he worked, the next day

at 10:00 o’clock; that Sympson gave him a subpoena so

he could leave work and testify (Tr. 240-241); that the

next morning about 10:00 o ’clock, at the gate of the Gen

eral Motors plant, he met Sympson (Tr. 242); that he and

Sympson drove in Sympson’s car to the intersection where

“ this accident happened” (Tr. 242), at Sunshine Road and

Chrysler Road (Tr. 232), which is about a block from the

place of his employment (Tr. 242); that there they met

Matt Jones and Phil Cabbell (Tr. 242), who were in a Ford

car being driven by Cabbell—he “ supposed” it was Ca

bell’s car (Tr. 279); that he, Jones and Sympson rode in

Sympson’s car and Sympson showed them “ about, oh, the

speed that the Plymouth was going” (Tr. 243); that the

Sympson car was “ supposed to be Matt’s (Jones’ ) car on

the day of the accident” (Tr. 244); that Sympson told him

that the “ Plymouth was supposed to pass” the car in which

he was riding with Jones “ at a high rate of speed” (Tr.

244, 245). His answer as to what Cabbell did upon this

occasion was stricken (Tr. 247). His answer as to what

Sympson said to him with reference to what Cabbell was

doing is unintelligible (Tr. 247). He could remember no

other conversation there with Sympson, Jones or Cabbell

(Tr. 247-248). He testified that, after being at the scene

of the accident for about 45 minutes (Tr. 248), he, Symp-

son and Jones went to Osborne’s office; that Cabbell did

not accompany them (Tr. 248); that at the office J. Carl

James wrote a statement which he (Everage) did not read,

but which he testified was dated back (Tr. 251); that toy

cars were there used to demonstrate how the accident

happened (Tr. 252); that Osborne was there a part of the

time (Tr. 249-250); that he went to the Court House

around 2:00 or 3:00 o’clock, but remained in the witness

room the rest of the afternoon; that Sympson and J. Carl

James were in this witness room most of the time; that

Osborne was in and out; that Osborne gave him $100.00

(Tr. 255-256); that he used this money to pay a bill at the

Palace Clothing Co. the following Saturday (Tr. 257).

A credit on the account of Vernon Everage with the

Palace Clothing Co. on Saturday, Sept. 30, 1950, amounts

to $10.55 (Tr. 376-377).

Mrs. Helen Everage, wife of Vernon Everage (Tr.

383) testified that her husband told her on the day he tes

tified that he had done something he was terribly sorry

for; that he had made false testimony (Tr. 383).

A. W. Disselhoff testified that on March 28, 1948 he

witnessed an accident at the intersection of Sunshine Road

and Chrysler Road in the Fairfax District in Kansas City,

Kansas; that he testified in the case of Burton vs. Moulder;

that he was driving North on Chrysler Road prior to the

accident; that he was following a Plymouth car (Tr. 403);

that there was no car between his automobile and the

Plymouth prior to the accident; that he stopped at the

scene of the accident and did not see any colored people

(Tr. 404).

F. B. Clay (Tr. 418) testified that he was riding with

Disselhoff on March 23, 1948 and observed an accident at

Chrysler Road and Sunshine Blvd. (Tr. 418); that they

9

followed a Plymouth car north on Chrysler for about a

block before the accident (Tr. 419); that he did not recall

any car passing his car and the Plymouth (Tr. 419); that he

did not recall seeing any automobiles driving along Chry

sler Road or Sunshine Blvd. at the time (Tr. 419); that he

has worked at the B. O. P. (General Motors) plant all the

time since the accident (Tr. 420) and rode to work with

Disselhoff for one and one-half years after the accident (Tr.

421); that he never gave any previous testimony (Tr. 421);

that until about a month before (the contempt hearing) no

one asked him anything about this accident (Tr. 421); that

he “ guessed” that no one tried to get him to testify when

the case (Burton vs. Moulder) was tried (Tr. 421); that

probably 3,000 men went to work at the General Motors

plant at the 8:00 o ’clock shift (Tr. 422); that there was

“bound” to be heavy traffic on these highways at the time

in question, but he wouldn’t want to say for sure because

“ it’s been so long ago” (Tr. 425); that lots of negroes go to

work on that shift (Tr. 426); that he didn’t recall anything

that would make him say “ there were or there weren’t”

(Tr. 427-428) any negroes there (at the scene of the acci

dent) ; that he did not mean to say there were no negroes

there (Tr. 426).

At the close of the evidence the petitioners filed mo

tions for discharge which were overruled (Tr. 64, 65-66;

67, 68-69, 70-71; they were found guilty and punishment

was assessed (Tr. 77). Motions for new trial were filed

and overruled (Tr. 77, 544-549; 557-562) and judgment

was entered (Tr. 78-91).

10

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES.

I.

Due process of law, as guaranteed petitioners by

Amendment XIV, Section 1, of the Constitution of the

United States and Article I, Section 10, of the Constitution

of Missouri, was denied petitioners in the trial of the cause

resulting in the judgment upon which the within commit

ment is based, in that, at said trial petitioners were denied

the right to have an impartial judge; that by reason thereof

said judgment and commitment is illegal.

1. Since the pleadings admit that the Honorable

Thomas R. Hunt was not impartial, it follows that peti

tioners were denied due process of law.

Amendment XIV, Sec. 1, Const, of U. S.

Article I, Section 10, Const, of Missouri

Inland Steel Co. vs. National Labor Rel. Board,

109 Fed. (2d) 9, 20, 21

Schmidt vs. U. S.,

115 Fed. (2d) 394, 397, 398

Toledo Newspaper Co. vs. U. S.,

237 Fed. 986, 988

Cornish vs. U. S.,

299 Fed. 283, 285

Turney vs. Ohio,

273 U. S. 510; 47 S. Ct. 437, 445

Cooke vs. U. S.,

267 U. S. 517; 45 S. Ct. 390, 396

Jordan vs. Massachusetts,

225 U. S. 167; 32 S. Ct. 651, 652

2. The affidavits as to the prejudice of Honorable

Thomas R. Hunt (Tr. 8, 110-112; 19, 114-116; 28, 127-129)

11

divested him of jurisdiction and required the substitution

of another Circuit Judge.

Sec. 545.660, R. S. Mo., 1.949

State vs. Mitts (Mo.)

29 S. W. (2d) 125, 126

3. The Circuit Court of Jackson County, Missouri is

one court composed of ten divisions and ten regular judges.

Sec. 478.463, R. S. Mo., 1949

State vs. Howard (Mo.)

205 S. W. (2d) 530, 532

State ex rel Mac Nish vs. Landwehr,

332 Mo. 622; 60 S. W. (2d) 4, 7

4. The proceeding could have been transferred to

another division or any judge of said court could have held

court in said Division No. 4 on request of Judge Hunt.

Sec. 545.650, R. S. Mo., 1949

Sec. 478.500, R. S. Mo., 1949

5. Any Circuit Judge in this state could, on request,

have held court in said Division No. 4.

Article V, Section 15, Const, of Missouri

State vs. Emerich (Mo.),

237 S. W. (2d) 169, 172

Sections 11.01, 11.02, 11.03, 11.04

Rules of Supreme Court

6. The substitution of another judge is not a change

of venue.

State ex rel McAllister vs. Slate,

278 Mo. 570; 214 S. W. 85, 87

State ex rel Renfro vs. Wear,

129 Mo. 619; 31 S. W. 608

12

7. Criminal contempt is a specific criminal offense

and a judgment in a prosecution therefor is a judgment in

a criminal case.

Ex parte Shull,

121 S. W. 10, 11; 221 Mo. 623

Ex parte Clark,

106 S. W. 990, 997; 208 Mo. 121

Cannon vs. State,

55 Pac. (2d) 135 (Okla.)

Brophy vs. Industrial Accident Assn.,

115 Pac. (2d) 835, 837 (Colo.)

In re Haley,

41 Fed. (2d) 379, 381

U. S. vs. Hoffman,

161 Fed. (2d) 881

People ex rel Atty. Gen, vs. Kinsley,

74 Pac. (2d) 663 (Colo.)

8. Where, as here, the affidavits disqualifying a trial

judge are in substantial compliance with the statute, the

trial court has no power or authority to proceed, except to

direct the substitution of another judge.

State vs. Irvine,

72 S, W. (2d) 96, 100; 335 Mo. 261

State vs. Myers,

14 S, W. (2d) 447; 322 Mo. 48

State vs. Mitts, supra

Thompson vs. Sanders, (en banc)

70 S. W. (2d) 1051, 1055; 334 Mo. 1100

13

II.

In rendering the judgment upon which the commit

ment is based, the Circuit Court exceeded its contempt

power and violated Article I, Section 22 (a) of the Con

stitution of Missouri, which provides that the right of a

trial by jury, as heretofore enjoyed, shall remain inviolate,

in that, the constitutional right of a trial by jury, of any

issue of fact in a criminal prosecution, rendered the Circuit

Court without power, without the aid of a jury, to try the

issue of fact erroneously assumed to have been raised by the

pleadings, in the proceeding here involved; the common law

power of the Circuit Court required it to try the issue of

contempt vel non on the sworn answer of the accused only.

Article XIII, Sec. 8, Const, of Mo., 1820

Article XIII, Sec. 8, Const, of Mo., 1855

Article I, Sec. 17, Const, of Mo., 1865

Article II, Sec. 28, Const, of Mo., 1875

Lindell vs. McNair,

4 Mo. 380

State ex rel Pulitzer Pub. Co. vs. Coleman,

347 Mo. 1239; 152 S. W. (2d) 640, 645

1. Constructive criminal contempt of court was a

criminal offense at common law and is a criminal offense

in Missouri.

Ex parte Shull,

221 Mo. 623; 121 S. W. 10, 11

Ex parte Clark,

208 Mo. 121; 106 S. W. 990, 997

2. Constructive criminal contempt at common law was

tried either on an indictment and to a jury or by the court

on the sworn and incontrovertible answer of the accused.

Burke vs. State,

47 Ind. 528

4 Bl. Com. 293

14

Bacon Abr. Attachment B

3 Hawk. P. C. b. 2, Ch. 22, Secs. 1, 32, 33, 34

7 Am. & Eng. Ency. of Law (2d Ed.), 71, 72

Welch vs. People,

30 111. App. 399

Appeal of Verden,

97 Atl. 783 (N. J.)

People vs. Doss,

46 N. E. (2d) 984, cert, denied,

64 S. Ct. 38; 320 U. S. 762 (111.)

Croft vs. Culbreath,

6 So. (2d) 638 (Fla.)

State vs. Vincent,

26 Pac. 939 (Kan.)

People vs. McLaughlin,

166 N. E. 67 (111.)

Hiner vs. State,

182 N. E. 245 (Ind.)

People vs. Seymour,

111 N. E. 1008 (111.)

People vs. Friedlander,

199 111. App. 300

People vs. Harrison,

86 N. E. (2d) 208 (111.)

People vs. McDonald,

145 N. E. 636 (111.)

In re Walker,

82 N. C. 95

People ex rel Chicago Bar Assn. vs. Novotny

54 N. E. (2d) 536; Cert, denied,

65 S. Ct. 71; 323 U. S. 734 (111.)

Thomas vs. Cummins,

I Yeates 40 (Pa.)

People vs. McKinley,

II N. E. (2d) 933 (111.)

State ex rel Allison vs. Municipal Ct.,

56 N. E. (2d) 493 (Ind.)

15

State vs. Earl,

41 Ind. 464

People vs. Whitlow,

191 N. E. 222 (111.)

People vs. Northrup,

279 111. App. 129.

Provenzales vs. Provenzales,

90 N. E. (2d) 115 (111.)

Denny vs. State,

182 N. E. 313 (Ind.)

Stewart vs. State,

39 N. E. 508 (Ind.)

Underwood’s Case,

2 Hump. 46 (Tenn.)

3. The contempt powers of the constitutionally

created courts of Missouri are those of the law courts at

common law.

State ex inf Crowe vs. Shepherd,

76 S. W. 79; 177 Mo. 205.

C. B. & Q. Ry. Co. vs. Gildersleeve,

118 S. W. 86; 219 Mo. 170

Ex parte Creasy,

148 S. W. 914; 243 Mo. 679

State ex rel Pulitzer Pub. Co. vs. Coleman, supra

4. This court has followed the common law procedure

insofar as it was applicable to the cases considered.

Ex parte Clark,

106 S. W. 990, 998; 208 Mo. 121.

Glover vs. American Casualty Ins. & Sec. Co.,

32 S. W. 302, 305; 130 Mo. 173

Ex parte Nelson,

157 S. W. 794, 802-803; 251 Mo. 63

5. The following cases from other states are based on

facts somewhat analogous to and ruled in harmony with

16

the pronouncements of this court in Ex parte Nelson,

supra.

State vs. New Mexican Ptg. Co.,

177 Pac. 751 (N. M.)

Baumgartner vs. Jouglin,

141 So. 185 (Fla.)

People vs. Gilbert,

118 N. E. 196 (111.)

People vs. Sherwin,

166 N. E. 513 (111.)

Dossett vs. State,

78 N. E. (2d) 435 (Ind.)

Freeman vs. State,

69 S. W. (2d) 267 (Ark.)

In re Chadwick,

67 N. W. 1071 (Mich.)

III.

The complaint for criminal contempt (Tr. 2-4) is in

sufficient to vest jurisdiction in the Circuit Court, charge

constructive criminal contempt of court, or upon which

to predicate a valid judgment; in that, it is vague, indefinite

and uncertain; it fails to state the particular circumstances

of the offense attempted to be charged and is not verified.

Section 476.140, R. S. Mo., 1949

Article XIV, Section 1, Const, of the United States

Article I, Section 10, Const, of Missouri

Article I, Section 18 (a), Const, of Missouri

Reardon vs. Frace, infra

17 C. J. S., Section 72

1. Where a charge is vague, indefinite and uncer

tain, it is tantamount to no charge at all and a conviction

thereon violates due process of law.

Thornhill vs. Alabama,

310 U. S. 88; 60 S. Ct. 736, 741

17

De Jcmge vs. Oregon,

299 U. S. 353, 362; 57 S. Ct. 255, 259

Stromberg vs. California,

283 U. S. 359, 367, 368; 51 S. Ct. 532, 535

2. In failing to state the particular circumstances of

the offense, the charge is fatally defective.

Frowley vs. Superior Court,

110 Pac. 817 (Cal.)

State ex rel vs. Dist. Court,

236 Pac. 553 (Mont.)

Cornish vs. U. S.,

299 Fed. 283

Rucker vs. State,

85 N. E. 356 (Ind.)

Dreher vs. Superior Court,

12 Pac. (2d) 671 (Cal.)

Wyatt vs. People,

28 Pac. 961 (Colo.)

Phillips vs. Superior Court,

137 Pac. (2d) 838 (Cal.)

Ex parte Lyon,

81 Pac. (2d) 190 (Cal.)

Grace vs. State,

67 So. 212 (Miss.)

State vs. Henthom,

26 Pac. 937 (Kan.)

Carlino vs. Downs,

279 N. Y. S. 510

Ex parte Collins,

45 N. W. (2d) 31 (Mich.)

Simmons vs. Simmons,

278 N. W. 537 (S. D.)

Haynes vs. Haynes,

212 Pac. (2d) 312 (Kan.)

Ex parte Donovan,

216 Pac. (2d) 123 (Cal.) '

18

Rutherford vs. Holmes,

66 N. Y. 368

Brunton vs. Superior Court,

116 Pac. (2d) 643 (Cal.)

People vs. Friedlander,

199 111. App. 300

Michigan Gas & Elec. vs. City,

262 N. W. 762 (Mich.)

See also authorities Point IV, infra.

3. Perjury alone does not constitute such an obstruc

tion to the performance of judicial duty as to constitute

contempt.

In re Michael,

326 U. S. 224; 66 S. Ct. 78

Ex parte Creasy, supra, (Mo. en banc)

U. S', vs. Goldstein,

158 Fed. (2d) 916, 920

In re Gottman,

118 Fed. (2d) 425

U. S. vs. Arbuckle,

48 Fed. Supp. 537, 538

In re Eskay,

122 Fed. (2d) 819, 823-824

4. The failure to verify the complaint rendered the

same insufficient to vest the Circuit Court with jurisdic

tion.

Sec. 545.240, R. S. Mo., 1949

State vs. Lawhorn,

250 Mo. 293; 157 S, W: 344

State vs. Sykes,

285 Mo. 25; 225 S. W. 904

State vs. Weyland,

126 Mo. App. 723; 105 S. W. 660

State vs. Trout,

274 S. W. 1098 (Mo. App.)

19

State vs. Gutke,

188 Mo. 424; 87 S. W. 503

State vs. Kelly,

188 Mo. 450; 87 S. W. 451

5. All the authorities seem to agree that a charge of

constructive contempt must be verified by the oath of a

party having personal knowledge of the facts or by the

oath of a public officer, if the proceeding be instituted by

him.

People vs. Harrison, supra

Denny vs. State, supra

Cushman vs. Mackesy,

200 Atl. 505 (Me.)

Craddock vs. Oliver,

123 So. 87 (Ala.)

Ex parte Scott,

123 S. W. (2d) 306 (Tex.)

Ex parte Diggers,

95 So. 763 (Fla.)

Stewart vs. State,

39 N. E. 508 (Ind.)

IV.

The commitment, under and by virtue of which peti

tioners are imprisoned is void, not only because of the

insufficiency of the complaint, as heretofore asserted, but

because the judgment and commitment dees not set forth

the particular circumstances of the offense of which they

were convicted.

Sec. 476.140, R. S. Mo., 1949

Reardon vs. Frace, (en banc)

344 Mo. 448; 126 S, W. (2d) 1167, 1169

Ex parte Fuller, ( en banc)

50 S. W. (2d) 654; 330 Mo. 371

Ex parte Shull, supra

20

Ex parte Creasy, supra

Ward vs. Lamb,

177 S. W. 365 (Mo.)

Ex parte Stone,

183 S. W. 1058 (Mo.)

People ex rel Butwill vs. Butwill,

38 N. E. (2d) 377 (111.)

Waldman vs. Churchill,

186 N. E. 690 (N. Y.)

Ex parte Lake,

224 P. 126 (Cal.)

V.

If extraneous evidence was permissible to controvert

the sworn answer of the accused, which we deny, there

was not sufficient competent evidence to sustain a judg

ment of constructive criminal contempt.

1. The witness, Vernon Everage, was an incompetent

witness because he was jointly charged with these peti

tioners (Tr. 2-4) and the case was not disposed of as to

him when he was permitted, over objection (Tr. 227) to

testify.

Sec. 546.280, R. S, Mo., 1949

State vs. Chyo Chiagk,

92 Mo. 395; 4 S. W. 704

State vs. Weaver,

165 Mo. 1; 65 S. W. 308

State vs. McGray,

309 Mo. 59; 273 S. W. 1055

State vs. Falger,

154 Mo. App. 1; 133 S. W. 85

Ex parte Dickinson,

132 S. W. (2d) 243 (Mo. App.)

2. Even if the evidence of Everage is considered the

most that can be claimed for it is that it established per

21

jury only; and while petitioners deny its sufficiency for

that purpose, it is clear that perjury alone is insufficient

to establish criminal contempt of court.

See authorities Point III (3).

3. As to Phil Cabbell: Mere presence, even plus ac

quiescence or mental approval, which is the most that can

be said of the evidence as to Cabbell, is not sufficient to es

tablish participation in an offense in any degree.

State vs. Bresse,

326 Mo. 885; 33 S. W. (2d) 919

State vs. Odbur,

317 Mo. 372; 295 S. W. 734

State vs. Simon,

57 S. W. (2d) 1062 (Mo.)

State vs. Mathis,

129 S. W. (2d) 20 (Mo. App.)

j. ARGUMENT.

I.

Due process of law, as guaranteed petitioners by

Amendment XIV, Section 1, of the Constitution of the

United States and Article I, Section 10, of the Constitution

of Missouri, was denied petitioners in the trial of the

cause resulting in the judgment upon which the within

commitment is based, in that, at said trial petitioners were

denied the right to have an impartial judge; that by reason

thereof said judgment and commitment is illegal.

Specifically: The Honorable Thomas R. Hunt, Judge,

who presided at said trial, violated Amendment XIV, Sec

tion 1, of the Constitution of the United States, which

provides that no State shall deprive any person of liberty

or property without due process of law, and violated Arti

cle I, Section 10, of the Constitution of Missouri, which

22

provides that no person shall be deprived of liberty or

property without due process of law.

Said violations consisted in this: That at said trial the

said Honorable Thomas R. Hunt deprived these petitioners

of the right to have an impartial judge; that at and by

said trial the liberty and property of these petitioners were

jeopardized; that said judgment, if upheld, will deprive

petitioners of their liberty and property.

(1) Admittedly the said Honorable Thomas R. Hunt

was not impartial. In the answers to the return, each pe

titioner alleges [par. 1(1)] that Judge Hunt “ was, in fact,

prejudiced against this petitioner and in said cause and was

not wholly unprejudiced.” This allegation is admitted by

respondent’s demurrers to said answers.

(2) Each petitioner timely made, filed in said cause

and presented to said Honorable Thomas R. Hunt (Tr. 8,

110-112; 19, 114-116; 28, 127-129) his affidavit, supported

by the affidavits of two reputable persons, not of kin to or

counsel for said petitioner, that Judge Hunt, the judge of

said court in which said cause was pending, would not af

ford him a fair trial, was prejudiced against him and that,

by reason of said prejudice, petitioner could not have a

fair trial of said cause before said judge; that petitioner

prayed that a change of venue be awarded or that another

circuit judge be notified and requested to try said cause.

Of these sub-points in their order:

1. Due process of law, under the conditions here of

record, clearly requires that the accused be accorded the

right to an impartial judge.

Inland Steel Co. vs. National Labor Rel. Board,

109 Fed. (2d) 9, 20, 21

Schmidt vs. U. S.,

115 Fed. (2d) 394, 397, 398

23

Toledo Newspaper Co. vs. U. S.,

237 Fed. 986, 988

Cornish vs. 17. S.,

299 Fed. 283, 285

Turney vs. Ohio,

273 U. S. 510; 47 S. Ct. 437, 445

Cooke vs. U. S'.,

267 U. S. 517; 45 S. Ct. 390, 396

Jordan vs. Massachusetts,

225 U. S. 167; 32 S. Ct. 651, 652

In the Inland Steel Co. case, supra, the court said:

“That a trial by a biased judge is not in conform

ity with due process is sustained by the authorities.

In Turney vs. Ohio, 273 U. S. 510, 535; 47 S. Ct. 437,

445; 71 L. Ed. 749; 50 A. L. R. 1243, the court said:

* * * ‘No matter what the evidence was against him,

he had the right to have an impartial judge. * * *’

The court, in Jordan vs. Massachusetts, 225 U. S.,

167, 176; 32 S, Ct. 651, 652; 56 L. Ed. 1038 said: ‘Due

process implies a tribunal both impartial and men

tally competent to afford a hearing. * * *’ ”

The Cooke case, supra, involved indirect criminal con

tempt. It was reversed and remanded by the United

States Supreme Court. There the court said:

“We think, therefore, that when this case again

reaches the District Court, to which it must be re

manded, the judge who imposed the sentence herein

should invite the senior Circuit Judge of the Circuit

to assign another judge to sit in the second hearing of

the charge against petitioner.”

In the Toledo Newspaper Co. case, supra, the subject

of trying constructive contempt cases before judges sit

ting in the place and stead of those before whom the al

leged contempts were committed, is considered. There

the court said:

24

“ * * * but it is of the greatest importance that

contempt proceedings be put, as far as possible, be

yond the reach of even unjust adverse criticism, and in

such a situation as has been recited, the judges of this

court upon whom the duty may fall will always be

ready to assign a judge from another district.”

In the Cornish case, supra, the court repeated much of

what was said in the Toledo Newspaper Co. case, with the

following additional observation:

“ * * * where there is more than one judge in the

district, there is less degree of need for special desig

nation. * * *”

The Schmidt case, supra, was one for constructive

criminal contempt against two lawyers. It was charged

that said lawyers had advised their clients that it was

proper to interrogate grand jurors concerning the evidence

upon which indictments were based. The clients filed af

fidavits of bias and prejudice as to the trial judge (28

U. S. C. A. 144) and the accused lawyers appended thereto

their certificates of good faith. In that case the court said:

“ The judge should not have been required to try

the contempt cases while he was confronted with the

affidavits of bias and prejudice, to which appellants

had appended their certificates of good faith. This is

no reflection upon the judge, nor upon any judge so

confronted. Even a judge may not put aside the pro

pensity of human nature as easily as he does his robe.”

2. The affidavits as to the prejudice of the Honorable

Thomas R. Hunt, filed and presented to him by petitioners,

were authorized by Section 545.660, R. S. Mo., 1949. While

commonly designated applications for change of venue,

such designation is a misnomer (State vs. Mitts, (M o.), 29

S. W. (2d) 125, 126). Strictly, the applications were for

the substitution of another judge.

25

The Circuit Court of Jackson County (16th Judicial

Circuit) is one court, consisting of ten divisions, with one

regular circuit judge for each division (Sec. 478.463, R. S.

Mo., 1949; State vs. Howard, (Mo.), 205 S. W. (2d) 530,

532; State ex rel Mac Nish vs. Landwehr, 332 Mo. 622, 60

S. W. (2d) 4, 7). The cause could have been transferred

to another division of the same court presided over by a

different judge (Sec. 545.650, R. S. Mo., 1949). Another

judge of the same court could have held court in said Di

vision 4, at the request of Judge Hunt and tried said cause

(Sec. 478.500, R. S. Mo., 1949). Any circuit judge in the

state, at the request of Judge Hunt, could have held court

in said Division No. 4 (Art. V, Sec. 15, Const, of Mo.; State

vs. Emerich, (Mo.), 237 S. W. (2d) 169, 172).

A simple and convenient means of affording petitioners

jtheir constitutional right to a trial by an impartial judge

was, therefore, readily available. The situation was

analogous to, but even more convenient than, the federal

system where there is more than one judge of a district

court.

Another circuit judge could have been substituted in

the place and stead of the Honorable Thomas R. Hunt with

out changing the venue of the proceeding.

State ex rel McAllister vs. Slate,

278 Mo. 570; 214 S. W. 85, 87

In the Slate case the prejudice of the judge was es

tablished by evidence in a prohibition proceeding. In the

case at bar such prejudice is admitted by the pleadings. In

the Slate case the court said:

“ If in fact bias exists, to an extent which will pre

clude a fair, unprejudiced, and unbiased weighing of

the law and the facts on the state’s side upon a trial of

the case of State v. Scott, then prejudice is present to

a degree forbidden to a judge by both the common law

26

(Massie v. Com., 93 Ky. 588, 20 S. W. 704) and the

statute * * *.”

In the Slate case this court followed State ex rel Renfro

vs. Wear, 129 Mo. 619; 31 S. W. 608. In the Wear case the

■prosecuting attorney relied upon Sec. 4174, R. S. Mo., 1889

and this court ruled that Judge Wear was disqualified.

Sec. 4174, R. S. Mo., 1889, is now Sec. 545.660, R. S., 1949.

In the Wear case sub-division one of said statute was suc

cessfully invoked. In the case at bar petitioners unsuc

cessfully attempted to invoke sub-division four of this same

statute. The statute specifically applies to a “ criminal

prosecution” * * * pending in any circuit court.

Criminal contempt is a “ specific criminal offense” and

a judgment in a prosecution therefor is a “ judgment in a

criminal case.”

Ex parte Shull,

121 S. W. 10, 11; 221 Mo. 623

Ex parte Clark,

106 S. W. 990, 997; 208 Mo. 121

Cannon vs. State,

55 Pac. (2d) 135 (Okla.)

Brophy vs. Industrial Accident Assn.,

115 Pac. (2d) 835, 837 (Colo.)

In re Haley,

41 Fed. (2d) 379, 381

U. S. vs. Hoffman,

161 Fed. (2d) 881

People ex rel. Atty. Gen. vs. Kinsley,

74 Pac. (2d) 663 (Colo.)

Where, as here, the affidavits disqualifying a trial

judge are in substantial compliance with the statute, the

trial court has no power or authority to proceed, except to

direct the substitution of another judge.

State vs. Irvine,

72 S. W. (2d) 96, 100; 335 Mo. 261

27

State vs. Myers,

14 S. W. (2d) 447; 322 Mo. 48

State vs. Mitts, supra

Where, as here, the affidavits are duly made, filed, pre

sented and denied, the trial judge loses jurisdiction to pro

ceed, a subsequent judgment rendered by him is void and

is subject even to collateral attack on habeas corpus.

Thompson vs. Sanders,

70 S. W. (2d) 1051, 1055; 334 Mo. 1100 (en banc)

When the complaint in the cause here considered was

originally filed in the Circuit Court the judge of the then

Assignment Division, No. 8, thereof (the Honorable Paul A.

Buzard) assigned said proceeding to Division No. 4 of said

Court (Tr. 5-6). The entry of the order of transfer was

doubtless furnished (Tr. 6) by opposite counsel herein,

whose names are signed to the complaint (Tr. 4). The

reason assigned for such transfer was that

“ * * * the law is well settled that the Court alone

in which a contempt is committed, or whose authority

is defied, has power and jurisdiction to punish it or

to entertain proceedings to that end, and because no

other court has any jurisdiction or power in such cases

* * *. (Entry furnished).”

In this connection, it is noteworthy that Rules of Crimi

nal Procedure for the Courts of Missouri are in the course

of preparation for final adoption; that said rules will be

adopted pursuant to Article V, Section 5 of the Constitution,

which expressly provides “ that the same shall not change

substantive rights” . Referring to the report of the drafting

committee for such rules, dated March 28, 1951, and pro

posed Rule XV, as set forth in said report, the same pro

vides that “ If the contempt charged involves disrespect to

or criticism of a judge, that judge is disqualified from pro

28

ceeding at the trial or hearing, except with the defendant’s

consent” (pp. 100-101). It seems this proposed rule is

based upon Federal Rule 42 and Advisory Rule 29.61. The

Honorable Paul A. Buzard is a member of this drafting

committee (p. 37). It follows, therefore, that Judge Buzard

and his fellow committeemen either did not believe, when

this committee report was compiled, that the court alone

in which a contempt is committed has jurisdiction to punish

the same, or they did not believe that the substitution of

another judge in the place and stead of the regular judge

of such court would deprive the same of jurisdiction to try

such proceeding.

II.

In rendering the judgment upon which the commit

ment is based, the Circuit Court exceeded its contempt

power and violated Article I, Section 22 (a), of the Con

stitution of Missouri, which provides that the right of a

trial by jury, as heretofore enjoyed shall remain invio

late, by reason of which said judgment is void.

Said violation and excess of jurisdiction consisted in

this: The petitioners, by their sworn answers (Tr. 9, 12-

15; 19, 22-24; 28, 32-33), specifically and categorically

denied all matters and things charged as constituting the

contempt; thereafter they filed separate motions for dis

charge (Tr. 9, 16-18; 19, 25-27; 28, 34-36), which said mo

tions were, by the court, denied; whereupon, the court, un

aided by a jury, received and heard extraneous evidence

as to the truth or falsity of the allegations of said answers

and, based on said evidence, rendered said judgment.

(1) Our Circuit Courts, in indirect criminal contempt

proceedings, must keep within their common law authority,

thereby exercising their contempt power within the frame

work of our Constitutional inhibitions.

29

The provision of Article I, Section 22 (a), of the Con

stitution of Missouri, insofar as it provides that the right

to a trial by jury, as heretofore enjoyed, shall remain in

violate, has been in every constitution of this state.

Article XIII, Sec. 8, Const, of Mo., 1820

Article XIII, Sec. 8, Const, of Mo., 1855

Article I, Sec. 17, Const, of Mo., 1865

Article II, Sec. 28, Const, of Mo., 1875

The Act of Congress, approved June 4, 1812 (1 Mo. Ter

ritorial Laws 8) provided:

“No man shall be deprived of his life, liberty or

property but by judgment of his peers and the law of

the land.”

This was translated from the Magna Charta (State ex

rel Pulitzer Pub. Co. vs. Coleman, 347 Mo. 1239; 152 S. W.

(2d) 640, 645).

Manifestly, the first Constitution of our state adopted,

and our subsequent Constitutions have preserved, the right

to a trial by jury as that right was secured by the Magna

Charta.

In 1816 the Missouri Territorial Assembly adopted the

common law of England in substantially the same word

ing as is now Sec. 1.010, R. S. Mo., 1949 (Lindell vs. McNair,

4 Mo. 380).

Indirect or constructive criminal contempt of court

was a criminal offense at common law and is a criminal of

fense in Missouri.

Ex parte Shull,

221 Mo. 623; 121 S. W. 10, 11

Ex parte Clark,

208 Mo. 121; 106 S. W. 990, 997

30

The Magna Charta forbade that any person should be

tried for a criminal offense, except upon an indictment

of the grand inquest and to a jury. In the face of this

prohibition, there could be no trial by the court, unaided

by a jury, of an issue of fact in an indirect criminal con

tempt proceeding.

At common law, such charges were tried, either on an

indictment and to a jury, or by the court, on the sworn,

incontrovertible answer of the accused. Where the trial

was to the court, without a jury, the common law pro

cedure was:

(a) The issue of contempt vel non was tried solely

on the sworn answer of the accused.

(b) The sworn answer, denying the facts charged as

constituting contempt, was conclusive and entitled the

accused to his discharge.

(c) If the sworn answer was insufficient, i. e., was

evasive, or admitted facts which established the alleged

contempt, punishment at once could be imposed.

An able review of the common law authorities is to

be found in the case of Burke vs. State, 47 Ind. 528. See

also:

4 Bl. Com. 293

Bacon Abr. Attachment B

3 Hawk. P. C. b. 2, Ch. 22, Secs. 1, 32, 33, 34

7 Am. & Eng. Ency. of Law (2d Ed.), 71, 72

In Welch vs. People, 30 111. App. 399, the court said:

“ Upon the question of what the common law of

England is upon any subject upon which they write,

the concurring testimony of Blackstone and Hawkins,

the first in his Commentaries, and the last in his Pleas

of the Crown, is conclusive. * * *

31

The plaintiff in error, in answer to the rule to

show cause why he should not be attached for con

tempt in attempting to influence a juror, by his affi

davit explicitly, without evasion, denied the whole

charge in detail. * * * the denial should have ended

the inquiry; * * *

The court had jurisdiction of the subject matter

and of the person of plaintiff in error, but it had no

jurisdiction of the mode of proceeding. This distinc

tion is not easily defined (Lange vs. Benedict, 73 N. Y.

12), but it is easily illustrated. The Criminal Court,

having before it a defendant indicted for an offense,

however trivial, has no authority, without his con

sent, to try the issue of fact. If he pleads guilty, the

court may fix the punishment. If he denies the charge

against him, the court, unaided, can go no further.

The sturdy principles of the common law exempt him

from submitting an issue of fact to any other tribunal

than a jury of his peers, with the right of challenge.

People vs. Hanchett, 16 Legal News 320 is as instruc

tive and almost persuasive, as authority, as if the em

inent judge who decided it had sat where he did when

he delivered the opinion in People vs. Whitson, 74

111. 20.

All the further proceedings, by examining wit

nesses, were without warrant of law. * * *” (Em

phasis ours).

In Appeal of Verden, 97 Atl. 783 (N. J.) the court

said:

“ What the common law of England was at the

time at which we derived it from the parent country

is thus stated by Blackstone, who wrote at about that

period:

* * If the party can clear himself upon oath, he

is discharged; but, if perjured, may be prosecuted for

the perjury.’ * * *

“ * * * That this immemorial usage underwent no

change in its transplanting to the American states is

32

shown by a decision of the Supreme Court of New

York, while Kent was still chief justice. The court

said:

‘The attachment, by virtue of which he had been

arrested, was nothing more than a process to bring him

into court, to answer the interrogatories which * * *

were to be exhibited against him. This is necessary to

be done in every case, before a party can be convicted

of a contempt. If the answers to the interrogatories

show that no contempt has been committed, the party

is entitled * * * to his discharge; but if the contempt

is admitted, the court proceeds to pronounce such judg

ment as the circumstances of the case may require.

Jackson vs. Smith, 5 Johns (N. Y.) 117.’

To the same effect is the decision of all courts that

proceed according to the course of the common law.

«i» H* H*

Contempt was a criminal offense, and Magna

Charta expressly forbade that any person should be

tried for a criminal offense unless upon the indict

ment of the grand inquest. In the face of this pro

hibition there could be no trial by the court. * * * The

net result of these fundamental restrictions was that

in the summary proceeding for contempt there could

be no trial, and hence no witnesses, from which it

followed that if the defendant was to be convicted

in such summary proceeding, it must be upon facts ad

mitted by his own oath, * * * For the present pur

poses the significant feature of this common law pro

cedure is that it excluded the idea of a trial of the

accused, either by witnesses against him or by the

contradiction of his oath by that of others. As well

stated by a recent writer:

‘The common law mode of proceeding in cases of

contempt presents no question of fact to be tried by a

jury. The defendant determines by his own answer,

under oath, whether he is guilty of that which is

charged against him as a contempt, and if he fails

33

thereby to purge himself, the court may at once im

pose the punishment’ 5 R. C. L. p. 523.

This procedure was obviously not a mere rule of

convenience which the judges might follow or not,

as they saw fit; on the contrary, it was a solemn and

substantial necessity, and hence a matter of substan

tive law.

^ ̂ ̂ $

Except it keep within its common law authority,

no court of law in this state can summarily convict

and punish for a criminal contempt any more than

it could convict and punish for any other criminal of

fense without indictment and trial by a petit jury.

?

In the case of People vs. Doss, 46 N. E. (2d) 984, cert,

denied, 64 S. Ct. 38; 320 U. S. 762 (111.), the court said:

“ In a case, as here, where a contempt proceeding

is instituted to maintain the court’s authority and to

uphold the administration of justice, and where the

acts charged were not committed in the presence of

the court, a sworn answer denying the alleged wrong

ful acts is conclusive, extraneous evidence may not he

received to impeach it, and the defendant is entitled to

his discharge. * * *

If the answer is false, the remedy is by indict

ment for perjury. * * * On the other hand, if the an

swer admits the material facts charged to be true and

the facts constitute a contempt of court, punishment

is imposed. * * *

In either event, the offender is tried solely upon

his answer. It follows, necessarily, that the defendant

is not entitled to a trial by jury because no issue of

fact is or can be formed for a jury to try. * * *” (Em

phasis ours).

34

The weight of judicial authority sustains our position.

Croft vs. Culbreath,

6 So. (2d) 638 (Fla.)

State vs. Vincent,

26 Pac. 939 (Kan.)

People vs. McLaughlin,

166 N. E. 67 (111.)

Hiner vs. State,

182 N. E. 245 (Ind.)

People vs. Seymour,

111 N. E. 1008 (111.)

People vs. Friedlander,

199 111. App. 300

People vs. Harrison,

86 N. E. (2d) 208 (111.)

People vs. McDonald,

145 N. E. 636 (111.)

In Re Walker,

82 N. C. 95

People ex rel. Chicago Bar Assn. vs. Novotny,

54 N. E. (2d) 536; cert, denied,

65 S. Ct. 71; 323 U. S. 734 (111.)

Thomas vs. Cummins,

I Yeates 40 (Pa.)

People vs. McKinley,

II N. E. (2d) 933 (111.)

State ex rel Allison vs. Municipal Ct.,

56 N. E. (2d) 493 (Ind.)

State vs. Earl,

41 Ind. 464

People vs. Whitlow,

191 N. E. 222 (111.)

People vs. Northrup,

279 111. App. 129

Provenzales vs. Provenzales,

90 N. E. (2d) 115 (111.)

35

Denny vs. State,

182 N. E. 313 (Ind.)

Stewart vs. State,

39 N. E. 508 (Ind.)

Underwood’s Case,

2 Hump. 46 (Tenn.)

(2) The contempt powers of the constitutionally

created courts of Missouri are those of the law courts at

common law—not those of the canon law courts of the

Star Chamber or the Chancery Courts in equity.

The judicial power of the State is, by Article V, Sec

tion 1, of the Constitution of Missouri, 1945, vested in the

courts therein named, including our Circuit Courts. Sim

ilar provisions are found in all the constitutions of Mis

souri, beginning with our first Constitution of 1820.

As we understand the Missouri authorities, this con

stitutional provision vested in such constitutional courts

the inherent powers of the law courts of the common law.

State ex inf Crowe vs. Shepherd,

76 S. W. 79; 177 Mo. 205

C. B. & Q. Ry. Co. vs. Gildersleeve,

118 S. W. 86; 219 Mo. 170

Ex parte Creasy,

148 S. W. 914; 243 Mo. 679

State ex rel Pulitzer Pub. Co. vs. Coleman,

152 S. W. (2d) 640; 347 Mo. 1239

The Shepherd case was modified by the Creasy case

to the extent indicated in the dissenting opinion in the

Gildersleeve case; that is to say, the legislature may not

alter this power, but may enact statutes reasonably reg

ulating the same. In the Pulitzer Pub. Co. case (S. W. 1. c.

647) the Supreme Court adhered “ to what was said in

the Shepherd case, as modified by Ex parte Creasy.”

36

This court has followed this common law procedure

insofar as it was applicable to the cases considered.

In Ex parte Clark, 106 S. W. 990, 998; 208 Mo. 121,

this court said:

“ Drawing from the undefiled well of the common

law, we find it said by Blackstone (4 Bl. *286); * *

This process of attachment is merely intended to bring

the party into court, and, when there, he must either

stand committed, or put in bail, in order to answer

upon oath to such interrogatories as shall be admin

istered to him for the better information of the court

with respect to the circumstances of the contempt.

These interrogatories are in the nature of a charge or

accusation, and must by the course of the court be

exhibited within the first four days,’ etc.”

Here we complete the quotation from 4 Blackstone

*286, which we believe is pertinent to the case at bar.

“ and if any of the interrogatories are improper, the

defendant may refuse to answer it, and move the

court to have it struck out. If the party can clear

himself upon oath, he is discharged; but if perjured,

may be prosecuted for the perjury.” (Emphasis ours).

In Glover vs. American Casualty Ins. & Sec. Co., 32

S. W. 302, 305; 130 Mo. 173, this court said:

“ When the defendant came with the affidavits of

its president and general counsel, and showed that the

contract had in fact been destroyed a year prior to

the commencement of plaintiff’s action, and had not

been destroyed to evade inspection, surely it purged

itself of the supposed contempt; and this has always

been allowed ‘by its oath’ says Blackstone.” (Emphasis

ours).

In Ex parte Nelson, 157 S. W. 794, 802-803; 251 Mo. 63,

the issue of contempt vel non was ruled on the sworn an

37

swer of the accused. There the answer admitted the pub

lication of a contemptuous publication that was not am

biguous; it merely denied a contemptuous intent. Such

answer was ruled insufficient, but the rule was recog

nized that, had the publication been ambiguous, the an

swer would have been conclusive.

The following cases from other states are based on

facts somewhat analogous to and ruled in harmony with

the pronouncements of this court in Ex parte Nelson,

supra.

State vs. New Mexican Ptg. Co.,

177 Pac. 751 (N. M.)

Baumgartner vs. Jouglin,

141 So. 185 (Fla.)

People vs. Gilbert,

118 N. E. 196 (111.)

People vs. Sherwin,

166 N. E. 513 (111.)

Dossett vs. State,

i 78 N. E. (2d) 435 (Ind.)

Freeman vs. State,

69 S. W. (2d) 267 (Ark.)

In re Chadwick,

67 N. W. 1071 (Mich.)

In State ex rel Pulitzer Pub. Co. vs. Coleman, 152 S.

W. (2d) 640, 644, 647-648; 347 Mo. 1239, the case was ruled

on a motion “ for judgment on the pleadings” (152 S. W.

(2d) 1. c. 644). Although the information charged that the

publication scandalized the court with reference to a pend

ing case, the answer, denying such reference to a pending

case, was sustained as a matter of law and this court ruled

that even scandalous criticism of a court relative to a closed

case did not constitute contempt because such criticism was

not contempt at common law.

38

III.

The unverified complaint for criminal contempt (Tr.

2-4) is insufficient to vest jurisdiction in the Circuit Court,

charge constructive criminal contempt of court, or upon

which to predicate a valid judgment.

The complaint fails to state particular circumstances

or facts, sufficient to charge an offense and particularly to

charge the offense of constructive criminal contempt of

court attempted to be charged. The prosecution of these

petitioners upon said complaint and the enforcement of the

judgment based thereon in the instant proceeding in the

Circuit Court violated Amendment XIV, Section 1, of the

Constitution of the United States, which provides that no

state shall deprive any person of liberty or property with

out due process of law; it violated Article I, Section 10, of

the Constitution of Missouri, which provides that no person

shall be deprived of liberty or property without due process

of law and it violated Article I, Section 18 (a) of the Con

stitution of Missouri, which provides that in criminal prose

cutions the accused shall have the right to demand the

nature and cause of the accusation.

Said violations consisted in this, to-wit: that in said

proceeding the liberty and property of these petitioners

were jeopardized; that if said judgment and commitment

are adjudged valid petitioners will be deprived of liberty

and property thereby; that said complaint for criminal con

tempt so insufficiently states particular circumstances and

facts and is so vague, indefinite and uncertain as to not

charge the offense of constructive criminal contempt of

court, which was attempted to be charged and of which of

fense said judgment purports to convict petitioners, to not

enable these'petitioners to know and be informed of the

nature and cause of the accusation and to not enable them

to prepare their respective defenses thereto.

39

A commitment for constructive criminal contempt must

set forth the “ particular circumstances” of the offense

(Sec. 476.140, R. S. Mo., 1949). The statute is merely

declaratory of the common law (Reardon vs. Frace, infra).

The complaint, therefore, must sufficiently particular

ize circumstances and facts to enable a valid judgment to be

rendered and a valid commitment to be issued thereon,

which is within the scope of the charge or complaint (17

C. J. S., Sec. 72).

The complaint in the instant case is not only vague,

indefinite and uncertain, but is replete with conclusions

and fatal omissions.

The complaint charges:

“ That in the course of preparing for and during

the trial of the case of Burton v. Moulder, * * * (all

of the accused) did confederate and did unlawfully act

to impede and obstruct the administration of justice

by * * * undertaking to present to whatever jury that

might be drawn for the actual trial of the case, and by

actually presenting, the testimony of two alleged wit

nesses who in truth and fact had never actually wit

nessed any of the occurrences out of which the law

suit of Burton v. Moulder arose. * * *” (Tr. 3)

The particular circumstances or facts relative to the

acts, words or conduct of petitioners in allegedly undertak

ing to present and in presenting said testimony are not

charged. It is not necessarily improper to produce wit

nesses who “ never actually witnessed any of the occur

rences out of which” a law suit arose. The said two wit

nesses are not named, or otherwise designated. For aught

that appears from the facts charged, the two witnesses

mentioned may have been experts, physicians, mechanics,

or persons who observed the appearance of plaintiff with

40

reference to health or disability before or after the casualty.

A more groundless, indefinite and uncertain charge is rarely

found.

The particular circumstances or facts relative to the

case of Burton vs. Moulder are not alleged; no facts are

charged as to the nature of said cause or the issues thereof.

The testimony so allegedly presented is not set forth. No

facts are alleged from which this court can determine

whether the alleged testimony was material or pertinent

to any issues or whether the Circuit Court had jurisdiction

of the subject matter. Not even the conclusion that the

alleged testimony was material or pertinent to any issue in

the cause or that the court had jurisdiction of the subject

matter thereof is alleged.

The complaint further charges:

“ The contemnors Osborne and Sympson * * *

Cabbell, located contemnors Jones and Everage and

arranged to have (them) * * * take the witness stand

on behalf of the plaintiff and to falsely and fraudu

lently testify to facts that were not within their per

sonal knowledge.

“ The contemnor Osborne promised * * * Jones

and Everage * * * the sum of $100.00 each for them to

testify falsely as aforesaid. The contemnors Jones and

Everage did so testify and were actually paid the sum

of $100.00 each by * * * Osborne for such false testi

mony.

“That contemnor James assisted * * * Os

borne, Sympson and Cabbell in their acts and actions

in coaching * * * Jones and Everage as to what false

testimony the latter should give * * *” (Tr. 3).

These allegations are replete with conclusions. That

the accused located Jones and Everage; that they arranged

for them to falsely testify; that Jones and Everage did

41

falsely testify and that the accused coached Jones and

Everage as to what false testimony they should give, all

are conclusions—not particular circumstances or facts.

The particular circumstances or facts relative to what

facts the accused coached or arranged for Jones and Ever

age to testify to, are not charged; if Jones or Everage

gave the testimony so arranged for or upon which they were

so allegedly coached, it is not so pleaded. No reference

whatever is made to the materiality of the testimony of

Jones or Everage to any issue in the cause. What facts,

if any, in the testimony of Jones or Everage were false

is not alleged. That Jones or Everage knew at the time

of the giving of such testimony that any part thereof was

untrue, is not charged. It is not even charged that Jones

or Everage were sworn or affirmed; or, if they were, by

whom or in what cause, matter or proceeding, and before

what court, body, tribunal or officer.

The complaint charges:

“ Each of the named contemnors had full knowl

edge of the aforesaid plan and the individual

conduct of each, standing alone, constituted action

which was designed to and which actually did impede

and obstruct the administration of justice.” (Tr. 3)

Elsewhere in paragraph 5 it is alleged that the ac

cused “ * * * did * * * act to impede and obstruct the ad

ministration of justice * * In paragraph 9, the com

plaint charges:

“ * * * the conduct * * * (of the accused)

tended to interfere and did in fact impede * * * the

administration of justice * * * in this court.” (Tr. 3, 4)

The indispensable element of an obstruction to the per

formance of judicial duty is the basic theory of the com

plaint, but sufficient particular circumstances are not al

42

leged therein to reveal what, if any, judicial function or

duty was allegedly impeded or obstructed.

Indulging in intendment (which cannot be done),

the most that could be said is that the pleader intended to

base the charge upon perjury and its tendency to defeat

the ultimate purpose of a trial, since it may produce a

judgment not resting on truth.

However, even by such unwarranted intendment, con

tempt of court is not charged, since perjury alone does not

constitute an obstruction which justifies the exertion of

the contempt power. To rule otherwise “ would permit too

great inroads on the procedural safeguards of the Bill of

Rights.” (In re Michael, Infra).

The weight of judicial authority, we believe, sustains

our contention that the complaint is wholly insufficient to

sustain the judgment.

1. Where a charge is vague, indefinite and uncertain,

it is tantamount to no charge at all and a conviction

thereon violates due process of law.

In Thornhill vs. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88; 60 S. Ct.. 736,

741, the court said:

“ In these circumstances, there is no occasion to go

behind the face of the statute or of the complaint for

the purpose of determining whether the evidence, to

gether with the permissible inferences to be drawn

from it could ever support a conviction founded upon

different and more precise charges. ‘Conviction upon

a charge not made would be sheer denial of due proc

ess.’ DeJonge vs. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 362; 57 S. Ct.

255, 259; 81 L. Ed. 278; Stromberg v. California, 283

U. S. 359, 367, 368; 51 S. Ct. 532, 535; 75 L. Ed. 1117;

73 A. L. R. 1484.” (Emphasis ours)

43

In the De Jonge case, cited, supra (57 S. Ct. 255, 259)

the court said:

“ Conviction upon a charge not made would be

sheer denial of due process.”

In the Stromberg case, cited, supra (51 S. Ct. 532, 536)

the court said:

“A statute which, upon its face, and as authorita

tively construed, is so vague and indefinite as to per

mit the punishment of the fair use of this opportunity

is repugnant to the guaranty of liberty contained in

the Fourteenth Amendment. The first clause of the

statute being invalid upon its face, the conviction of

the appellant, which so far as the record discloses may

have rested upon that clause exclusively, must be set

aside.” (Emphasis ours)

2. In failing to state the particular circumstances of

the offense, the charge is fatally defective.

In the case of Frowley vs. Superior Court, 110 Pac.

817 (Cal.) the court said:

“ It is familiar law that in proceedings for con

structive contempt of court * * * the affidavit which

is made the basis for the proceeding should show

upon its face the acts which constitute the contempt.

The affidavit constitutes the complaint, and, unless

it contains a statement of facts which show that a con

tempt has been committed, the court is without juris

diction to proceed in the matter, and any judgment of

contempt based thereon is void, and will be so de

clared upon certiorari. * * *

Proceedings in contempt are of a criminal nature,

and no intendments or presumptions are to be in

dulged in in aid of the sufficiency of a complaint.

The affidavit (complaint) must set forth acts show

ing in themselves the fact that a contempt has been

committed by the party charged, and, failing to do

44

so, the court is absolutely without jurisdiction in the

matter” (Emphasis ours).

In the case of State ex rel vs. Dist. Court, 236 Pac. 553

(Mont.) the court held that a complaint which did not

disclose that the plaintiff in the civil action in which the

contempt was alleged to have been committed, had a good

cause of action, or any interest in the subject matter, or

that witnesses knew information pertinent to matters in

issue, did not state facts sufficient to constitute contempt.

In this case the court said:

“ * * * Although the entire proceeding is before

us, we do not know, and cannot know, whether Mr.

Sacket’s action is one for the recovery of damages for

personal injuries or a suit to foreclose a mortgage;

whether the subject matter of the litigation is an

alleged libel, a conversion of personal property, a

trespass upon realty or ultra vires acts of the officers

of a corporation, * *

In Cornish vs. U. S., 299 Fed. 283, the court said:

“ * * * in such a case the pleading, whether peti

tion or information or journal entry, by which the

prosecution is initiated, should state the necessary

facts, and not stop with conclusions. Under this test,

we think the petition herein is insufficient. It does

not state the facts from which it draws the inference

that the publication would obstruct the administra

tion of justice, nor does it make clear that the publi

cation, in its effect, went beyond reference to an order

already made.”

In Rucker vs. State, 85 N. E. 356 (Ind.) the court said:

“ * * * in all cases the person charged shall be

entitled, before answering or punishment, to have

served upon him a rule or order of court clearly and

distinctly setting forth the facts which are claimed as

constituting the contempt and which specifies the

45

time and place of such facts with such certainty as

will inform the defendant of the nature and circum

stances of the charge against him, and no such rule

shall issue until the facts alleged therein shall have

been brought to the knowledge of the court by an in

formation duly verified by the oath of some respec

table person.” (Emphasis ours)

In the case of Dreher vs. Superior Court, 12 Pac. (2d)

671 (Cal.) the court said:

“ Nor can it be maintained that this defect was

cured by the evidentiary showing made to the court

upon the hearing or specified and found by the court

in its decree adjudging petitioner guilty of contempt.

The affidavits constitute the complaint in proceed

ings that are distinctly criminal in their nature, and

must charge upon their face facts that clearly and

unmistakably constitute contempt. * * *” (Emphasis

ours)

To the same effect are the following cases:

Wyatt vs. People,

28 Pac. 961 (Colo.)

Phillips vs. Superior Court,

137 Pac. (2d) 838 (Cal.)

Ex parte Lyon,

81 Pac. (2d) 190 (Cal.)

Grace vs. State,

67 So. 212 (Miss.)

State vs. Henthom,

26 Pac. 937 (Kan.)

Carlino vs. Downs,

279 N. Y. S. 510

Ex parte Collins,

45 N. W. (2d) 31 (Mich.)

Simmons vs. Simmons,

278 N. W. 537 (S. D.)

Haynes vs. Haynes,

212 Pac. (2d) 312 (Kan.)

46

Ex parte Donovan,

216 Pac. (2d) 123 (Cal.)

Rutherford vs. Holmes,

66 N. Y. 368

Brunton vs. Superior Court,

116 Pac. (2d) 643 (Cal.)

People vs. Friedlander,

199 111. App. 300

Michigan Gas & Elec. vs. City,

262 N. W. 762 (Mich.)

Authorities Point IV, infra

3. Subornation of perjury is the misconduct attempted

to be charged in the complaint in the case at bar. Perjury

does not constitute such an obstruction to the performance

of judicial duty as to constitute contempt.

In re Michael,

326 U. S. 224; 66 S. Ct. 78

Ex parte Creasy, (en banc)

243 Mo. 679; 148 S. W. 914, 921, 924

V. S. vs. Goldstein,

158 Fed. (2d) 916, 920

In re Gottman,

118 Fed. (2d) 425

U. S. vs. Arbuckle,

48 Fed. Supp. 537, 538

In re Eskay,

122 Fed. (2d) 819, 823-824

In Ex parte Creasy, supra (S. W. 1. c. 921, 924), this

court said:

“ The ipse dixit of no court can make contempt of

that which does not rise to the level of contempt. If

this man has been guilty of perjury, the courts are

open, but the summary process for contempt does not

lie in such a case.

* * * ❖ *

47

That brings us to the consideration of the char

acter of the answers given by the Petitioner to the in

terrogatories propounded to him by the court and coun

sel. If they were false, then he was guilty of the crime

of perjury; and, if true, then he was neither guilty

of contempt of court nor of the crime of perjury, but

was innocent. Consequently the truthfulness or fals

ity of his testimony was one of fact, and, being a

felony, punishable by imprisonment in the peniten

tiary, he was clearly entitled to a trial by jury under

the guaranty of the section of the Constitution before

mentioned. If that is true, and I am unable to see

why it is not, then a jury, and not the court, should

have passed upon his guilt or innocence; and, as that

was not done, the petitioner should be discharged.”

(Emphasis ours)

4. The failure to verify the complaint rendered the

same insufficient to vest the circuit court with jurisdic

tion.

While the charging paper in the proceeding here con

sidered is called a complaint for criminal contempt, the

proceeding is initiated on the information of the prose

cuting attorney. The Statute (Sec. 545.240, R. S. Mo.,

1949) requires that all informations by the prosecuting

attorney shall be verified by oath and, the absence of

proper verification is fatal.

State vs. Lawhorn,

250 Mo. 293; 157 S. W. 344

State vs. Sykes,

285 Mo. 25; 225 S, W. 904

State vs. Weyland,

126 Mo. App. 723; 105 S. W. 660

State vs. Trout,

274 S. W. 1098 (Mo. App.)

State vs. Gutke,

188 Mo. 424; 87 S. W. 503

State vs. Kelly, i

188 Mo. 450; 87 S. W. 451

48

All the authorities seem to agree that a charge of

constructive contempt must be verified by the oath of a

party having personal knowledge of the facts or by the

oath of a public officer, if the proceeding be instituted by

him.

People vs. Harrison,

86 N. E. (2d) 207 (111.)

Denny vs. State,

182 N. E. 313 (Ind.)

Cushman vs. Mackesy,

200 Atl. 505 (Me.)

Craddock vs. Oliver,

123 So. 87 (Ala.)

Ex parte Scott,

123 S. W. (2d) 306 (Tex.)

Ex parte Diggers,

95 So. 763 (Fla.)

Stewart vs. State,

39 N. E. 508 (Ind.)