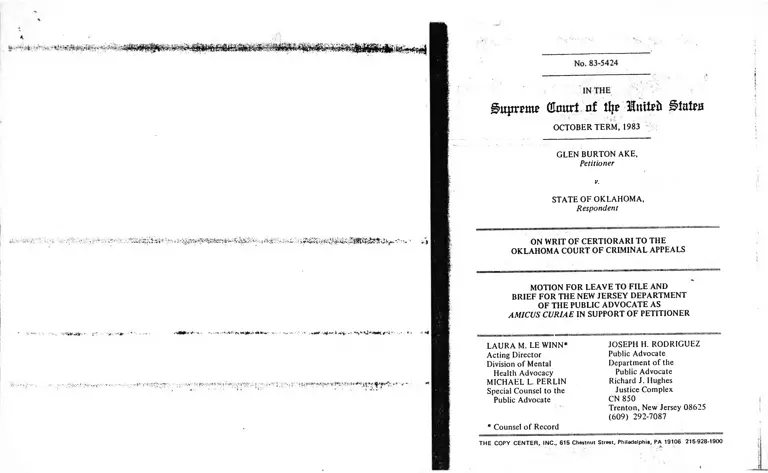

Ake v. Oklahoma Motion for Leave to File and Brief for the New Jersey Department of the Public Advocate as Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ake v. Oklahoma Motion for Leave to File and Brief for the New Jersey Department of the Public Advocate as Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner, 1983. 4acb6826-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/28faa72f-3929-4cc0-9521-a544d9033039/ake-v-oklahoma-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-for-the-new-jersey-department-of-the-public-advocate-as-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

U-■ ".--.fit • ( '

i

V-.'I r^-:>j.i?i^vr>^^?jS!5*i';:i: i i't.:>; if::.-.: ::..C.:.; i-iftiii'^ --'i

• •** - -~— ■» iv**:**^ ****>~- . iv*-.v» * >•.'1 . < , j * * f ■/

giqirrw (ttmtrl of tip IttUrh gtataa

OCTOBER TERM, 1983

GLEN BURTON AKE,

Petitioner

v.

STATE OF OKLAHOMA,

Respondent

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

OKLAHOMA COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND

BRIEF FOR THE NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT

OF THE PUBLIC ADVOCATE AS

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

LAURA M. LE WINN* JOSEPH H. RODRIGUEZ

Acting Director Public Advocate

Division of Mental Department of the

Health Advocacy Public Advocate

MICHAEL L. PERLIN Richard J. Hughes

Special Counsel to the Justice Complex

Public Advocate CN 850

* Counsel of Record

Trenton, New Jersey 08625

(609) 292-7087

THE COPY C EN T ER , INC., 615 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 215-928-1900

■h

m

m

mSmm

- 1 -

NO. 83-5424

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1983

GLEN BURTON AKE,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF OKLAHOMA,

Respondent,

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

A BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE

The New Jersey Department of the

Public Advocate1 (Department) respect

fully moves this Court for leave to file

**■•'*•

.•Y'iv

1 The Department is specifically

empowered to "represent the public

interest in such administrative and court

proceedings .... as the Public Advocate

(Footnote continued on next page)

- 2 -

the attached brief amicus curiae in this

case. The consent of the attorney for

the petitioner has been obtained; the

attorney for the respondent has neither

consented to nor opposed the Department1s

request.

The Department, an independent and

unique executive agency of New Jersey

state government,. N.J.S.A. 52:27E-2, has,

for almost ten years, litigated exten

sively in major areas affecting "the

public interest." During this period,

(Footnote 1 continued)

deems shall best serve the public

interest." N.J.S.A. 52:27E-29. "Public

interest" is defined as "an interest aris

ing from the Constitution, decisions of

the court, common laws or other laws of the

United States or of this State inhering in

the citizens of this State or in a broad

class of such citizens." N.J.S.A.

52:27E-30. Within the Department, the

Division of Mental Health Advocacy

(Division) was established to represent

"indigent mental hospital admittees" in

individual matters involving their admis

sion to, retention in, or release from

"mental hospitals," N.J.S.A. 52:27E-24, and

to represent such persons in class actions

on "an issue of general application to

them," N.J.S.A. 52:27E-25.

-3-

the Department has participated in a

wide variety of proceedings involving

issues relating to housing, utility

regulation, employment, the environment

and the rights of the mentally handi

capped. 2

2

The Division has litigated one case

to this Court, see Rennie v. Klein 653

F. 2d 836 (3 Cir. 1981), vacated — U.S.

— , 102 S. Ct. 3506 (1982), on remand

720 F. 2d 266 (3 Cir. 1983), and has

filed amicus briefs in three other cases

involving mental health issues within

its relevant experience and expertise.

Kremens v. Bartley, 431 U.S. 119 (1977);

Parham v. J.R., 442 U.S. 584 (1979),

Jones v. United States, — U.S. --,

103 S. Ct. 3043 (1983).

The Office of the Public Defender

(Office), see N.J.S.A. 2A:158A-1 et seq.,

which is administratively housed in the

Department and provides criminal defense

services to all indigent persons in the

State charged with indictable offenses,

provided representation in this Court of

respondent in Stickland v. Washington,

— U.S. — , 52 U.S.L.W. 4565 (1984).

-4-

The interest of the Department in

this case arises from its long-term

representation of persons charged with

crime whose mental state is at issue,

of institutionalized persons who wish to

refuse the involuntary imposition of

certain forms of powerful psychotropic

4medications, and of persons facing

5involuntary civil commitment. The

3

See, e.g., State v. Fields, 77 N.J.

282, 390 A. 2d 574 (1978) (right of in

sanity acquittees to periodic review of

commitments); State v. Khan, 175 N.J.

Super. 72, 417 A. 2d 585 (App. Div. 1980)

(right to contemporaneous competency

determination prior to imposition of in

sanity defense over defendant's objections) ;

In re A.L.U., 192 N.J. Super. 480, 471 A.

2d 63 (App. Div. 1984)(further articula

tion of periodic review rights of in

sanity acquittees).

4 See Rennie, supra. This Court has

recently acknowledged that the liberty

interests of involuntarily committed

mental patients "are implicated by the

involuntary administration of antipsychotic

drugs." Mills v. Rogers, 457 U.S. 291, 299

n. 16 (1982).

5 See, e.g., In re Geraghty, 68 N.J. 209,

343 A. 2d 737 (1975) (promulgation of court

rule mandating appointment of counsel at

(Footnote continued on next page)

-5-

Court's decision in the instant case will

directly affect this Department's

clientele on a wide range of issues in

volving insanity defense determinations, ‘ '*

the right to effective counsel, and the

right to be free from the unwanted im-

position of powerful medical treatment.

The Department seeks leave to file

its brief in order to augment the views

presented by the parties on the central

issues in this case, namely: (1) the

right of an indigent criminal defendant to

independent medical expertise in further

ance of an asserted defense of insanity;

and (2) the prejudicial effect to

petitioner of the administration of nsycho-

(Footnote 5 continued)

all commitment hearings); In re Alfred,

137 N.J. Super. 20, 347 A. 2d 537 (App.

Div. 1975) (scope of right of person facing

commitment to appointment of independent

psychiatric evaluation at county expense).

" VI

-6- ftropic medication through the course of -l-

his trial, to an extent which affected No. 83-5424

his demeanor and ability to communicate

during his trial. IN THE

To the best of our knowledge, no SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

other amicus or party in this case will OCTOBER TERM, 1983

deal with these matters from the same

GLEN BURTON AKE,

perspective as this Department has.

PETITIONER

For the above reasons, the Depart-

V.

ment respectfully requests leave to file

\ STATE OF OKLAHOMA,

the attached brief amicus curiae in this

RESPONDENT . .. .. . . . ; v.

case.

Respectfully submitted, ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

JOSPEH H. RODRIGUEZ

Public Advocate

OKLAHOMA COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS

. / •> /J, - BRIEF FOR THE NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT

B y : _ i X £ ^ Jk-MUU.yy.r-

LAURA M. LE WINN*

Acting Director,

Division of Mental

Health Advocacy

MICHAEL L. PERLIN

Special Counsel to the

Public Advocate

OP TvrR PUBLIC ADVOCATE AS AMICUS CURIAE

*Counsel of Record

- 1 -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF

AMICUS CURIAE ................. 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............ 4

ARGUMENT

I. ACCESS TO THE ASSISTANCE

OF INDEPENDENT PSYCHIATRIC

EXPERTISE IS INDISPENSABLE

TO A MEANINGFUL ASSERTION

OF AN INSANITY DEFENSE --- 6

A. The Role Of Independent

Medical Experts On

Behalf Of Criminal

Defendants Asserting

An Insanity Defense At

Trial, Is Of Historical

Origins ................ 6

B. Failure to Afford A

Criminal Defendant An

Independent Expert In

Furtherance Of A Prof

fered Insanity Defense

Vitiates The Adversarial

Process Which Is The

Hallmark Of A Full And

Fair Trial .............. 1

II. THE INVOLUNTARY MEDICATION

OF PETITIONER WITH THORAZINE,

AFFECTING HIS DEMEANOR AND

ABILITY TO COMMUNICATE

DURING TRIAL, VIOLATED DUE

PROCESS AND EQUAL PROTEC

TION RIGHTS ................ 4

-li- Page

A. The Known Properties

Of Thorazine And Its

Probable Effects On

Petitioner............. 47

B. The Relevant Caselaw

And Other Authorities

Support Petitioner's

Arguments Against

His Drugging ......... • 56

.... »** .V , . *

CONCLUSION ..................... . 65

-lli-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Adams v. United States ex rel

McCann, 317 U^S. 269 (1942) ... 21

Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S.

418 (1979) ................... 41

Ake v. Oklahoma, 663 P. 2d 1

(Okla. Ct. Crim. App.(1983)..28, 48,

63

Anderson v. State of Arizona,

663 P. 2d 570 (Ariz. Ct.

App. 1983)..................... 53

Barefoot v. Estelle, — U.S. — ,

103 S. Ct. 3383 (1983) ....... 41

Brinks v. Alabama, 465 F. 2d

446 (5 Cir. 1982), cert, den.

409 U.S. 1130 (1983), reh.

den. 410 UJ5. 960 (1983)___ 24, 27

Chesney v. Adams, 377 F. Supp.

887 (D. Conn. 1974) ......... 50

Commonwealth v. Louraine, 390

Mass. 28, 453 N.E. 2d

437 (S.J. Ct. 1983) ........ 57, 58

Davis v. Hubbard, 506 F. Supp.

915 (N.D. Ohio 1980) ....... 53

Davis v. United States, 160 U.S.

469 (1895) ................. 16, 17

Eddings v. Oklahoma, — U.S. — ,

102 S. Ct. 869 (1982) ....... 28

Ellis v. United States, 484 F. Supp.

4 ’ (DIS.C? '*1975)' .7. .......................... 50

- I V -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S.

454 (1981) ............... 23,

38

24, ' -7.

Estelle v. Williams, 425 U.S.

501 (1976) ............... 61

G.D. Searle & Co. v.

Institutional Druq Dis-

tributors, 141 F. Supp. 838

(D.C. Cal. 1955) ......... 49

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S.

335 (1963) ................ 19

Hadfield's Case, 27 Howell St.

Tr. 1281 (K.B. 1800) ..... 11

Hansford v. United States, 365

F. 2d 920 (D.C. Cir. 1966 .. 56

Illinois v. Allen, 397 U.S.

337 (1970) ............... 61, 63

In re Alfred, 137 N.J. Super.

20, 347 A. 2d 537 (App. Div.

1975) ........................ 3

In re A.L.U., 192 N.J. Super.

480, 471 A. 2d 63 (App. Div.

1984) ........................ 2

In re Geraghty, 68 N.J. 209,

343 A. 2d 737 (1975) ........ 3

In re K.K.B., 609 P. 2d

747 (Okla. Sp. Ct. 1980).... 53

-v-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES — Continued

Page

In re Pray, 133 Vt. 253, 336

A. 2d 174 (1975) ........ 57, 58

Jamison v. Farabee, No. C-78-

0445-WHO N.D. Calif. (Consent

Order filed April 26, 1983).. 53

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458

(1938) ...................... 19

Jones v. U.S. — U.S. — , 103

S. Ct. 3043 (1983) ......... 50

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586

(1978) ...................... 28

Loe v. United States, 545

F. Supp. 662 (E.D. Va. 1982).. 24

Matlock v. Rose, -- F. 2d

(6 cir. April 9, 1984) ..... 37

McMann v. Richardson, 397 U.S.

759 (1970) .................. 19

Mills v. Rogers, 457 U.S. 291

(1982) ..................... 2, 50,

58

M'Naghten's Case, 10 Cl. & F.

200, 8 Eng. Rep. 718 (H.L.

1843) ..................... 14, 16

Mordssette v. United States. 342

U.S. 246 (1952) 7

-vi-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Nogqle v. Marshall, 706 F. 2d

1408 (6 Cir. 1983), cert,

den. — IKS. 104

S. Ct. 530 (1983) ..........

People v. Ackles, 304 P. 2d

1032 (C.A. 3rd Dis. Calif.

1956) .......................

Peters v. State, 516 P. 2d 1373

(Okla. Cr. 1973) ..........

40

49

63

Porter v. Estelle, 709 F. 2d 944

(5 Cir. 1983), cert, den.

sub nom. Porter v. McKaskle,

-- U.S. 52 U.S.L.W. 3825

(1984) .....................

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45

(1932) ..................... 19,

42

Project Release v. Prevost, 722

F. 2d 960 (2 Cir. 1983) . .

21,

53

Regina v. Oxford, 9 Car. & P . 525

(N.P. 1840) ................. 13

Rennie v. Klein, 462 F. Supp.

1131 (D.N.J. 1979) ......... 52, 54

Rennie v. Klein, 476 F . Supp.

1294 (D.N.J. 1979) ......... 53

Rennie v. Klein, 653 F. 2d 836

(3 Cir. 1981), vacated, —

U.S. — , 102 S. Ct. 3506

(1982), on remand 720 F.

266 (3 Cir. 1983) .....

2d

— ' V..

2

-vii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Rennie v. Klein, 720 F. 2d 266

(3 Cir. 1983) ...............

Rivera v. Franzen, 33 Crim. L .

Rptr. 2276 (N.D. 111.

May 27, 1983) ............

Rogers y, Commissioner of

Mental Health, 390 Mass. 489,

458 N.E. 2d 308 (S.J. Ct.

. 53, 57

Rogers v. Okin, 478 F.

1342 (D. Mass. 1979)

Supp.

53

Ruiz v. Estelle, 503 F. Supp.

1265 (S.D. Tex. 1980), 650 F.

2d 555 (5 Cir. 1982), 666

F. 2d 854 (5 Cir. 1982),

679 F. 2d 1115 (5 Cir. 1982),

688 F. 2d 266 (5 Cir. 1982) ,

cert. den. — U •S. , 103

s7~Ct. 1438 (1983) ...........

Sanders v. U.S., 373 U.S. 1

(1963) ........................

Scott v. Plante, 532 F. 2d 939

(3 Cir. 1976)7 641 F. 2d 119

(3 Cir. 1981), vac. and rem.

458 U.S. 1101 (1982), on remand

691 F. 2d 634 (3 Cir. 1982) .... 55

State v. Fields, 77 N.J. 282, 390

A. 2d 574 (1978) ................ 2

State v. Hamilton, 441 So. 2d 1192

(La. S. Ct. 1988) ............ 28, 40

-viii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

State v. Khan, 175 N.J.

Super. 72, 417 A. 2d 585

(App. Div. 1980) .......... 2 ■. . .* .*•

State v. Kociolek, 23 N.J.

400, 129 A. 2d 417 (1957) .. 40

State v. Maryott, 6 Wash. App.

96, 492 P. 2d 239 (1971) ... £7, 58,61

* ,A

State v. Murphy, 56 Wash. 2d 761,

355 P. 2d 323 (1960) ...... 57 58

State v. Noel, 102 N.J.L. 659,

133 A. 274 (E.&A. 1926) ___ 27

State v. Spencer, 21 N.J.L.

196 (O.&.T. 1846) .......... 17

Stone v. Smith, Kline & French,

No. 82-7232, slip opinion, (11

Cir. May 14, 1984) ......... 51

Strickland v. Washington. — U.S.

— , 52 U.S.L.W. 4565 (1984). 20, 22,

40

Suzuki v. Quisenberry. 411

F. Supp. 1113 (D. Haw.

1976) ...................... 61

' >' •

United States v. Alvarez. 519

F. 2d 1036 (3 Cir. 1975) ... 39

United States v. Bass. 477 F.

2d 723 (9 Cir. 1975) ___ 7.. 34, 36

United States v. Brawner. 471

F. 2d 969 (D.C. Cir. 1972).. 7

-ix-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

United States v. Caldwell,

343 F. 2d 1333 (D.C. Cir.

1975), cert. den. 423

U.S. 1087 (1976) ............. 34 , 37

United States v. Chavis, 476

F. 2d 1137 (D.C. Cir. 1973) .. 34

United States v. Currens, 290

F. 2d 751 (3 Cir. 1961) ...... 16

United States v. Durant, 545 F.

2d 823 (2 Cir. 1976) ......... 35

United States v. Schultz, 431

F. 2d 907 (8 Cir. 1970) .... 30, 31,

35, 36

United States v. Taylor, 437

F. 2d 371 (-4 Cir. 1971) ........ 37

United States v. Theriault, 440

F. 2d 713 (5 Cir. 1971) ,

cert. den. 411 U.S. 984 -

(1983) ....................... 32, 33

36

United States v. Tucker, 716

F. 2d 576 (9 Cir. 1983) ...... 23

United States v. Wilson, 471

F. 2d 1072 (D.C. Cir. 1982)

cert. den. 410 U.S. 957

(1973) ....................... 51

Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480

(1980) ........................ 50

Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14

(1967) ....................... 29

Washington v. United States,

390 F. 2d 444 (D.C. Cir. 1967) .. 18

-x-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Whitehead v. Wainwright, 447

F. Supp. 898 (M.D. Fla.

1978). vac. and rem.

609 F. 2d 223 (5 Cir.

1980) ....................

Wood v. Zahradnick, 430

F. Supp. 107 (E.D. Va.

1977), aff'd 578 F. 2d

980 (4 Cir. 1978), further

proceedings at 611 F. 2d

1383 (4 Cir. 1980) ......

STATUTES

18 U.S.C. §3006A(e) ........ 29, 30,

----- 33, 36, 39

18 U.S.C. §4244 ............. 33 • 39

P.L. 91-447, §1, Oct. 14,

1970 ...................... 30

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

United States Constitution,

Amendment V ............. 22

United States Constitution,

Amendment VI ...... 22 * *24

United States Constitution,

Amendment XIV ............

20, 21,

26, 38

19

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Ayd, "A Survey of Drug Induced

Extrapyramidal Reactions,"

175 J-A.M.A 1054 (1961) .... 48

... •« • .-.KM A

-xi-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Biggs, The Guilty Mind

(1955) ..................... 9

Birley, Marcus Aurelius

(1966) ..................... 9

Block, "The Semantics of

Insanity," 36 Okla L. Rev.

561 (1983) ................. 16

2H. Bracton, De Legibus Et

Consuetudinibus Angliae

(S. Thorne Trans. 1968) .... 8

Broom, A Selection of Legal

Maxims (London 1845) ....... 9

Burt and Morris, "A Proposal

for Abolition of the In

competency Plea," 40

U. Chi. L. Rev. 66 (1972) .. 61

Bushman and Reed, "Tranquilizers

and Competency to Stand Trial,"

54 A.B.A.J. 284 (1968) ___ 58, 59

Cameron and Wimer, "An Anti

cholinergic Toxicity Reaction

to Chlorpromazine Activated

by Psychological Stress,"

167 J. Nerv. & Ment. Pis.

508 (1979) ................. 52

Coke, The First Part of the

Institutes of the Laws of

England, or a Commentary

Upon Littleton (17th ed.

1817) ...................... 9

-xii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Diamond, "Isaac Ray and the

Trial of Daniel M'Naghten,"

112 Am. J. Psych. 651 (1956) ...

Deniker, "Impact of Neuroleptic

Chemotherapies on Schizophrenic

Psychoses," 135 Am. J . Psych.

923 (1978) .....................

Detre and Jarecki, Modern

Psychiatric Treatment

(Lippincott, 1971) ....

"Developments in the Law: Civil

Commitment of the Mentally

111," 87 Harv. L. Rev.

1190 (1974) ................

Ennis and Litwack, "Psychiatry

and the Presumption of Ex

pertise: Flipping Coins in

the Courtroom," 62 Calif.

L. Rev. 693 (1974) ........

Ferleger, "Loosing the Chains:

In-Hospital Civil Liberties

of Mental Patients," 13

Santa Clara Law. 447 (1973) ..

Goldberg and Breznitz, eds.,

Handbook of Stress: Theoretical

and Clinical Aspects

(1983)..........................

Golten, "Role of Defense Counsel

in the Criminal Commitment

Process," 10 Am. Crim. L .

Rev. 385 (1972) ...............

Group for the Advancement of

Psychiatry, Misuse of Psychiatry

In the Criminal Courts:

Competency to Stand Trial

February, 1974) ...............

-xiii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Guttmacher, The Mind of the

Murderer (1960) .............. 10

Haddox, Gross and Pollack,

"Mental Competency to Stand

Trial While Under the

Influence of Drugs

7 Loyola L.A.L.R. 425 (1974) .. 60

Haddox and Pollack,

"Psychopharmaceutical Re

storation to Present Sanity

(Mental Competency to Stand

Trial), 17 J. For. Sci.

568 (1972) . .777777777777..... 60

1 Hale, The History of the

Pleas of the Crown (London 1736).. 9

Halleck, "American Psychiatry

and the Criminal: A

Historical Review," 1 Rieber

and Vetter (eds.), The

Psychological Foundations

of Criminal Justice (1978) ...... 11

Halleck, "The Role of the

Psychiatrist in the Criminal

Justice System,"Psychiatry

1982 Annual Review, 386 (1982) ... 17

Hartley and Couper-Smartt,

"Paradoxical Effects in

Sleep and Performance of Two

Doses of Chlorpromazine," 58(2)

Psychopharmacology 201 (1978) ___ 55

-xiv-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Hartley, Couper-Smartt and

Henry, "Behavioral Anta

gonism Between Chlorpromazine

and Noise in Man," 55

Psychopharmacology 97 (1977)..

Hawkins, A Treatise of the

Pleas of the Crown (London

1739) ........................

Hermann and Sor, "Convicting

ot Confining? Alternative

Directions in Insanity Law

Reform: Guilty But Mentally

111 Versus New Rules for

Release of Insanity

Acquittees," [1983] Brig.

Young L. Rev. 499 ...........

Hollister, "Adverse Reactions

to Phenothiazines" 189

J.A.M.A. 311 (1964) ......

Insanity Defense and Related

Criminal Procedure Matters,

H. Rep. No. 98-577, 98th“

Cong. 1st Sess. (1983) ....

Kinross-Wright, "The Current

Status of Phenothiazines,"

200 J.A.M.A. 461.(1967) ...

Kolb and Brodie, Modern

Clinical Psychiatry,

(10th Ed. 1982) ...........

,V , /

-xv-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

McBain, "The Insanity Defense:

Conceptual Confusion and

the Erosion of Fairness,"

67 Marquette L. Rev. 1 (1983).. 3

National Commission on the

Insanity Defense, Myths

and Realities (1982) .......... 3

Perlin and Sadoff, "Ethical

Issues in the Representation

of Individuals in the Commit

ment Process," 45 L. & Contemp.

Prob. 161 (1983) .............. 43

Physicians' Desk Reference

(1984 ed. ) ..................... 48

Plucknett, A Concise History

of the Common Law (5th ed.

1956) .......................... 8

Poythress, "Mental Expert

Testimony," 5 J. Psychiatry

& L. 201 (1977) ........... 44, 45

Poythress, "Psychiatric

Expertise in Civil Commitment:

Training Attorneys to Cope

With Expert Testimony,"

2 L. & Hum. Behav. 1 (1978) ... 42

Quen, "An Historical View of

the M'Naghten Trial," 1 Rieber

and Vetter (eds.), The

Psychological Foundations of

Criminal Justice (1978) .... 15

-xvi-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Ray, A Treatise on the Medical

Jurisprudence of Insanity

(19838) ................... 15, 54

Rodriguez, LeWinn and Perlin,

"The Insanity Defense Under

Seige: Legislative Assaults

and Legal Rejoinders," 14

Rutgers L. J . 397 (1983) .... 3

Scrignar, "Tranquilizers and

the Psychhotic Defendant,"

53 A.B.A.J. 43 (1967) ....... 58

Simon, "The Defense of Insanity,"

11 J. Psychiatry & L . 183

(1983)........................ 10

Simon, The Jury and the Defense

Of Insanity (1967) ........... 10

2 The Civil Law (S. Scott ed.

1973).......................... 9

2 tJ.S. Cong. & Admin. News

2993 (1964) ................ 31

Van Putten and May, "'Akinetic

Depression' in Schizophrenia,"

35 Arch. Gen. Psych. 1101

(1978) ......................... 55

Weihofen, Mental Disorder As A

Criminal Defense (1954) ....... 9

Winick, "Psychotropic Drugs And.

Competence to Stand Trial,"

1979 Am. Bar Fndtn. Res.

^ 769 .(1979) .... 7.......49, 59

W hfc9- -fib 'rr ' ’

-xvii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Winsberg and Yepes, "Anti-

psychotics (Major Tranquilizers,

Neuroleptis)" in Werry ed.,

Pediatric Psychopharmacology;

The Use of Behavior Modifying

Drugs in Children, (1978). ... 62

Ziskin, Coping With Psychiatric

and Psychological Testimony

(3d ed. 1981) ............... 45, 46

- 2 -

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

The interest of the New Jersey

Department of the Public Advocate in this

case arises from its long-term representa

tion of persons charged with crime whose ■***+» fm-*****. ..•*

mental state is at issue, 1 of

institutionalized persons who wish to

refuse the involuntary imposition of *#**.^*.--•**»-.* • '

certain forms of powerful psychotropic

medications, and of persons facing

1

See, e.g., State v. Fields, 77 N . J .

282, 390 A. 2d 574 (1978) (right of

insanity acquittees to periodic review

of commitments); State v. Khan, 173

N . J . Super. 72, 417 A .2d 585 (App. Div.

1980) (right to contemporaneous competen

cy determination prior to imposition of

insanity defense over defendant's

objections). In re A.L.U., 192 N . J .

Super. 480, 471 A. 2d 63 (App. Div.

1984) (further articulation of periodic

review of rights of insanity acquittees).

2 See, Rennie v. Klein, 653 F. 2d

836 (3 Cir. 1981), vacated — U.S. — ,

102 S. Ct. 3506 (1982), on remand 720

F. 2d 266 (3 Cir. 1983) . This Court

has recently acknowledged that the

liberty interests of involuntarily

committed mental patients "are implicat

ed by the involuntary administration of

anti-psychotic drugs." Mills v. Rogers,

457 U. S.. 291, 299 n. 16 (1982).

J?*;- ‘CMpJ'lh *

-3-

involuntary civil cominitment. The

Court's decision in the instant case

will directly affect this Department's

clientele on a wide range of issues in

volving insanity defense determinations, ̂

the right to effective counsel, and the

right to be free from the unwanted

imposition of powerful medical treatment.

See, e.g., In re Geraghty, 68 N.J.

209, 343 A. 2d 737 (1975)(promulgation of

court rule appointment of counsel at all

commitment hearings); In re Alfred, 137

N.J. Super. 20, 347 A. 2d 537 (App. Div.

1975) (scope of right of person facing

commitment to appointment of independent

psychiatric evaluation at county expense).

4 The Department's concern for — and

advocacy on behalf of — various issues

generated by the ongoing public debate

on the very concept of the insanity de

fense, has been reflected on a national

scale. See, e .g., National Commission on

the Insanity Defense, Myths and Realities

15 (1982); Insanity Defense and Related

Criminal Procedure Matters, H. Rep. No,

98-577, 98th Cong. 1st Sess., 5-6 n. 7-8,

10-11 (1933). See also Rodriguez, LeWinn,

and Perlin, "The Insanity Defense Under

Seige: Legislative Assaults and Legal

Rejoinders," 14 Rutgers L. J.. 397 (1983);

McBain, "The Insanity Defense: Conceptual

Confusion and the Erosion of Fairness,"

67 Marquette L. Rev. 1, 4 n. 15, 7-9

n. 29 (1983).

-4-

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In criminal trials at which the

question of defendant's mental capacity

at the time of commission of the alleged

offense is raised in defense, access by

such defendant to independent psychiatric

experts is essential both to aid in

presentation of the defense and to re

but evidence which may be offered in

opposition by the prosecution. The

critical role played by such experts in

these proceedings is well-established and

has long-standing historical roots.

A defendant's right to access to

independent experts in insanity trials

inheres in his very ability to obtain

effective assistance of counsel and a

fair trial. An indigent defendant,

therefore, is entitled to appointment of

such an independent expert on his be

half, by authorization of the court.

,k .uM*< ■ ii ->

-5-

The very nature of psychiatric

expertise itself requires that parties

to the proceedings be adequately

equipped to subject such evidence to

rigorous adversarial testing.

With respect to the issue of the

administration of psychotropic medication

during his trial, amicus contends that

such a practice was inherently

prejudicial to petitioner. The medication

in question, Thorazine, affected his

demeanor and capacity to communicate.

As such it deprived him of his ability

to participate in his trial and to con

trol his appearance before the jury. In

light of these severe consequences,

petitioner should at least be afforded

the protection of a pre-trial hearing at

which the need for such medication would

be the core inquiry.

- 6-

ARGUMENT

I.

ACCESS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF

INDEPENDENT PSYCHIATRIC

EXPERTISE IS INDISPENSABLE TO

A MEANINGFUL ASSERTION OF

AN INSANITY DEFENSE

A. The Role Of Independent

Medical Experts On Behalf Of

Criminal Defendants Asserting

An Insanity Defense At Trial

Is Of Historical Origins

The questions of criminal intent and

blameworthiness form the core inquiry

into the susceptibility to punishment of

an individual charged with the commission

of a crime. Consideration of criminal

intent is based on the assumption that a

person has the capacity to choose between

right and wrong, that he has a sense of

wrongdoing. "The concept of 'belief in

freedom of the human will and of con

sequent ability and duty of the normal

t

it, v.*i«v-£ «*•* ' ; ,«*3Plrw J

individual to choose between good and

evil’ is a core concept that is 'universal

and persistent in mature systems of law.'"

-7-

United States v. Brawner, 471 F. 2d 969,

985 (D.C. Cir. 1972) , quoting Morissette

v. United States, 342 U.S. 246, 250

(1952) .

In this regard, the insanity defense

has been a major component of Anglo-

American jurisprudence for over 700

years.^ Concomitantly, the role of expert

5

The insanity defense has been in

existence since at least the twelfth

century.

But what shall we say of a mad

man bereft of reason? And of

the deranged, the delirious and

mentally retarded? Or if one

labouring under a high fever

drowns himself or kills himself?

Quaere whether such a one commits

felony de se. It is submitted

that he does not,nor do such

persons forfeit their inheritance

or their chattels, since they

are without sense and reason and

can no more commit an injuria

or a felony than a brute criminal

since they are not far removed

from brutes as is evident in

the case of a minor, for if he

should kill another while under

age he would not suffer judgment.

[That a madman is not liable is

true, unless he acts under pre

tense of madness while enjoying

(Footnote continued on next page)

medical witnesses in insanity trials has

long-standing historical roots.

(Footnote 5 continued)

lucid intervals].

2H. Bracton, De Legibus Et Consuetudjnibus

Anqliae 424 (c. 1250) (S. Thorne Trans.

1968).

Before Bracton, the sources of the

insanity defense at common law can be

traced at least to the Roman legal

authorities that influenced Bracton. See

generally, Plucknett, A Concise History

of the Common Law 261-62 (5th ed. 1956) .

For example, in the Digests (or Pandects)

of Justinian first published in A.D. 533,

the following commentary on the insanity^

defense appears in an imperial "rescript"

issued by the brother emperors Marcus

Aurelius (A.D. 120-180) and Commodus

(A.D. 161-192) during the period of their

joint reign (A.D. 177-180);

If it is positively ascertained

by you that Aelius Perseus is to

such a degree insane that, through

his constant alienation of mind,

he is void of all understanding,

and no suspicion exists that he

was pretending insanity when he

killed his mother, you can disregard

the manner of his punishment,

since he has already been

sufficiently punished by his in

sanity; still, he should be placed

under careful restraint, and, if

you think proper, even be placed

in chains; as this has reference

not so much to his punishment as

to his own protection and the

safety of his neighbors.

(Footnote continued on next page)

'*>•*•<£ -y%*' % ^

v J r

-9-

Like the insanity defense,

the practice whereby the

courts call in experts to

advise them on matters not

(Footnote 5 continued)

If, however, as often happens

he has intervals of sounder

mind, you must diligently in

quire whether he did not

commit the crime during one

of these periods, so that no

indulgence should be given to

his affliction; and, if you

find that this is the case,

notify Us, that We may deter

mine whether he should be

punished in proportion to the

enormity of his offense, if he

committed it at a time when

he seemed to know what he was

doing.

2 The Civil Law 259 (S. Scott ed.

1973) For another translation, see

Birley, Marcus Aurelius 272-73 (1966).

The maxim derived from this Roman

commentary — furiosus solo furore

punitur (a madman is punished by his

madness alone) — appears in numerous

English cases and treatises on the

insanity defense. See, e.g. Broom, A

Selection of Legal Maxims 5 (London 1845);

Coke, The First Part of the Institutes

of the Laws of England, or a Commentary

Upon Littleton 247b (17th ed. 1817).

See also, 1 Hale, The History of the

Pleas of the Crown 29-37 (London 1736);

Hawkins, A Treatise of the Pleas of the

Crown, 1-3 (London 1739); Biggs, The

guilty Mind 47-56, 81-88 (1955)7 Weihofen,

Mental Disorder as a Criminal Defense

(Footnote continued on next page)

- 10-

generally known to the average

person goes back a long time:

in Engligh courts, over four

centuries. Initially, the

experts were used as technical

assistants to the court, rather

than as witnesses. The judge

summoned experts to inform him

about technical matters; he

then determined whether the

information should be passed on

to the jury. By the middle of

the seventeenth century, when

the finding of the facts had

become the exclusive province

of the jury, the practice of

court-appointed experts re

porting to the judge was abandon

ed; instead, the experts were

called as witnesses by the parties

involved in the dispute- Simon,

"The Defense of Insanity" 11

J. Psychiatry & L. 183, 193 (1983).

(Footnote 5 continued)

52-59 (1954); Simon, The Jury and

The Defense of Insanity, 16-20

(1967); see generally Hermann and

Sor, "Convicting or Confining?

Alternative Directions in Insanity

Law Reform: Guilty But Mentally

111 Versus New Rules for Release

of Insanity Acquittees," (1983]

Brig. Young L. Rev. 499, 506-515.

̂ For an overview of the evolution of

expert testimony in trials generally,

see Guttmacher, The Mind of the Murderer

109-117 (1960) (hereinafter "Guttmacher").

("By the last quarter of the seventeenth

century the practice of employing partisan

experts had become well established," id.

at 112).

r«

- 11-

Since at least the beginning of the

nineteenth century, "the search for

biological explanations of deviant

behavior has been unremitting. This is

particularly true of that deviant be

havior which is labelled as criminal. "

Halleck, "American Psychiatry and the

Criminal: A Historical Review," in 1

Rieber and Vetter (eds..) , The Psychological

Foundations of Criminal Justice, 8 (1978)

(hereinafter Psychological Foundations).

This development of medical involve

ment in issues of criminal responsibility

is reflected in early nineteenth century

cases such as Hadfield's Case, 27 Howell

St. Tr. 1281 (K.B. 1800). The defendant,

charged with high treason by virtue of

his attempt to assassinate King George III,

interposed a defense of insanity. Among

the witnesses called on his behalf were:

(1) Henry Cline, esq. [sic ] , described

- 12-

by defense counsel, Lord Erskine, as

"known to be one of the first anatomists

in the world," id. at 1320; (2) Doctor

Creighton, "a physician . . . [who had]

applied particular attention to the

disease of madness," id. at 1334; and

(3) Mr. Lidderdale, described as "a

surgeon," id. at 1335. Mr. Cline, the

anatomist, testified to the possibility

of brain damage sustained by the defend

ant from head wounds received in battle,

as a result of which, "tilt frequently

happens . . . there is some derangement

of the understanding." Id. at 1334. Dr.

Creighton stated: "I have not the

smallest doubt that he [defendant] is

insane . . . . He is not a maniac, but

he labours under mental derangement of a

very common but particular kind." Id-

at 1334. And the surgeon, Lidderdale,

testified to having examined defendant

M k ' rlj &

-13-

some four years earlier, " [i]n the

spring of 1796, [when defendant was]

brought in, in a state of insanity," and

treating him with "bleeding, blistering,

and cathartics." Id. at 1335-36. The

jury returned a verdict of "Not Guilty:

he being under the influence of Insanity

at the time the act was committed." Id.

at 1356.

Likewise, in Regina v. Oxford, 9

Car. & P. 525 (N.P. 1840) — again

involving a charge of high treason stem

ming from defendant's attempt to assassin

ate Queen Victoria — "[s]everal eminent

medical men were also called for the

prisoner . . . . They all gave it as their

decided opinion that he was of unsound

mind."7 id. at 541. Here, too, the

7

A footnote to the opinion at the end

of the above-quoted passage, states "no

medical men were examined on the part of

the prosecution, though it appeared that

Mr. Maule, the solicitor to the Treasury

(Footnote continued on next page)

-14-

jury found the prisoner "not guilty, he

being insane at the time." Id. at 551.

In the landmark trial in M'Naghten'.s.

Case. 10 Cl. & F . 200, 8 Eng. Rep. 718

(H.L. 1843), the medical evidence —

adduced by witnesses "called on the part

of the prisoner" 10 Cl. & F ., supra, at

201 — established that the defendant

was "affected by morbid delusions" which

carried him away beyond the power of his

own control and left him no . . . [moral]

perception [of right and wrong]." Id.

No less than eight medical experts

testified as to defendant's insanity; four

specifically testified that his disease

deprived him of control over his actions,

and one, Dr. E.T. Monro, described the

"type of thinking [which] is common in

(Footnote 7 continued)

was present at an interview which those

who were examined for [i.e ., called by]

the prisoner, had with him in Newgate."

Id. at 541, n. (a)l.

-15-

paranoid schizophrenia." Quen, "An

Historical View of the M'Naghten Trial,"

in Psychological Foundations, supra, at

93-94. Defense counsel made "extensive

and almost exclusive reference to the

work of the American physician, Isaac

Ray,^ in his [counsel's] attempt to

demonstrate that legally exculpable

insanity should include more than disease

of the intellect." Id. at 93.^

Ray is referred to as "the leader of

forensic psychiatry in [the United Sates],"

in Guttmacher, supra at 121. Writing

nearly 150 years ago, Ray stressed the

"utmost importance" of medical testimony

at an insanity defense trial, Ray,

A Treatise on the Medical Jurisprudence

of Insanity (1838), §27 at 48, (Overholser

ed. 1962) , noting it was essential that

such testimony be "founded on extra

ordinary knowledge and skill relative to

the particular disease, insanity," Id.,

§28 at 50. M'Naghten's lawyer focused

on Ray's writings on insanity in his

summation to the jury. See Diamond,

"Isaac Ray and the Trial of Daniel

M'Naghten," 112 Am. J. Psych. 651, 652-

654 (1956).

9

This attempt was apparently rejected by

(Footnote continued on next page)

-16-

The M ’Naghten trial had a gal

vanizing effect on the medico-legal

concept of insanity:

Earlier, there was only a de

sultory interest in the medical

jurisprudence of insanity among

British physicians. The legal

and Parliamentary reaction to the

trial focused their attention and

concern on this subject.

* * * *

In America, the M'Naghten Rules

are still being debated. One

result . . . [has been] the

increased attention to the neuro-

psychiatric aspects of criminality [.]

Id. at 96 [footnotes omitted].

While the rule of M'Naghten with

respect to the proper legal definition

of, or test for, insanity — may have

sparked debate, see, e^g., Davis_v.

United States, 160 1^. 469, 479-80 (1895),

United States v. Currens, 290 F. 2d 751

(Footnote 9 continued)

Chief Justice Tindal, who charged the jury

essentially in terms of defendant's cog

nitive functioning. Quen, Psychological

Foundations, supra at 94. See also,

for further discussion of this point.

Block, "The Semantics of Insanity, 3b

Okla. L. Rev. 561, 562-65 (1983).

• c*<«- - - a t- ■ i t “■

'lit*

-17-

(3 Cir. 1961), the crucial role of

medical experts in insanity trials has

long been recognized. As at least one

commentator has noted:

Psychiatric testimony in insanity

cases serves three purposes:

first, it supplies the court with

facts concerning the offender's

illness; second, it presents in

formed opinion concerning the

nature of that illness; and third,

it furnishes a basis for deciding

whether the illness made the

patient legally insane at the time

of the crime under that juris

diction's standards of insanity.

Halleck, "The Role of the Psychiatrist

in the Criminal Justice System,"

in Psychiatry 1982 Annual Review

386, 391 (1982).-Lu

See, e.g., State v. Spencer, 21

N.J.L. 196, 208 (0. & T. 1846) (cited in

Davis v. United States, 160 U .S . supra

at 483) , in which Chief Justice Hornblower

acknowledged the debt owed to medical

experts by "the administrators of criminal

law" in insanity defense trials, to wit:

I mean no disrespect to the

learned writers on medical juris

prudence, or other distinguished

men of the medical profession.

On the contrary, I consider the

administrators of criminal law

greatly indebted to them for the

results of their valuable experience,

and professional discussions on the

(Footnote continued on next page)

-18-

As will be discussed further in

Point IB, infra, in cases where an

insanity defense is interposed to

criminal charges, a defendant's access

to independent medical expertise is, by

now, inextricably intertwined with his

very ability to obtain a fundamentally

fair trial.

(Footnote 10 continued)

subject of insanity; and I

believe those judges who care

fully study the medical writers

and pay the most respectful

but discriminating attention

to their scientific researches

on the subject, will seldom, if

ever, submit a case to a jury

in such a way as to hazard the

conviction of a deranged man.

See also, Washington, v. United States,

390 F. 2d 444 (D.C. Cir. 1967) for a

thoughtful analysis by Chief Judge

Bazelon of the need " in future cases to

ensure that the issue of responsibility(

is decided upon sufficient information,

id. at 451, and a discussion of how to

render medical expert testimony more

comprehensible to juries in criminal

trials, ^d. at 454.

►

t* '$1.

-19-

B. Failure To Afford A Criminal

Defendant An Independent Expert

In Furtherance Of A Proffered

Insanity Defense Vitiates

The Adversarial Process Which

Is The Hallmark Of A Full And

Fair Trial

This Court has long recognized that

the right to counsel guaranteed by the

Sixth Amendment to the Constitution is

essential in order to protect a criminal

defendant's fundamental right to a fair

trial, Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45, 71

(1932); Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458,

462 (1938) ; Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S.

335, 342-45 (1963), and that this

fundamental right is applicable to the

several states through the Fourteenth

Amendment, Gideon, 372 U.S., supra at 341.

Specifically, "[i]t has long been

recognized that the right to counsel is the

right to effective assistance of counsel."

McMann v. Richardson, 397 U.S. 759, 771

n. 14 (1970).

- 20 -

Most recently, the standards by

which the constitutionally adequate

effectuation of this right should be

measured were articulated by this Court

in Strickland v. Washington, U^_S. ,

52 U.S.L.W. 4565 (1984). There, in

weighing a criminal defendant's claim

of ineffective assistance of counsel in

a capital case, the "benchmark" for

judging such a claim was described by

the Court as "whether . . . the trial

cannot be relied 'upon as having produced

a just result." Id. at 4570. The purpose

of the Sixth Amendment guarantee was

identified as "simply to ensure that

criminal defendants receive a fair trial,"

and "to ensure that a defendant has the

assistance necessary to justify reliance

on the outcome of the proceedings,

id. at 4571. In assessing the inter

relationship between the various components

- 21-

which comprise a "fair trial," the Court

stated:

Thus, a fair trial is one in which

evidence subject to adversarial

testing is presented to an im

partial tribunal for resolution

of issues defiried in advance of

the proceeding. The right to

counsel plays a crucial role in

the adversarial system embodied

in the Sixth Amendment, since

access to counsel's skill and

knowledge is necessary to accord

defendants the "ample opportunity

to meet the case of the prosecution"

to which they are entitled.

[citing Adams v. United States

ex reL McCann, 317 U.S. 269,

275-76 (1942); and Powell v. Alabama,

287 U.S♦, supra at 68-69]. Id.

Referring specifically to the question of

prejudice to a defendant from counsel's

errors in the context of a capital case,

the Court stated:

When a defendant challenges a

death sentence such as the one

at issue in this case, the

question is whether there is a

reasonable probability that,

absent the errors, the sentencer

— including an appellate

court, to the extent it

independently reweighs the

evidence — would have concluded

that the balance of aggravating

- 2 2 -

and mitigating circumstances

did not warrant death.

Id. at 4572

The Court then concluded that:

In every case the court should

be concerned with whether,

despite the strong presumption

of reliability, the result

of the particular proceeding

is unreliable because of a

breakdown in the adversarial

process that our system counts

on to produce just results.

Id. at 4573.11

It is acknowledged that the^"break

down in the adversarial process which

concerned this Court in Strickland,

supra, was bottomed on a claim of^errors

or deficiencies in trial counsel s

performance which preiudiced the defense,

co tt c l W supra at 4570-71, whereas,

in the* instant^case, the "breakdown" and

"prejudice" claimed by defendant ste

from actions or decisions of the t n a

judge. Notwithstanding this distinction,

the Strickland concepts of a fair tria

and "the adversarial system embodied i

the Sixth Amendment, id. at 4570, ar

directly pertinent to a consideration o

the claims here.

-ft. i* •.••*>̂*4 *»( « **-

- Vfftv'S'.*

-23-

In short, the inquiry on appeal should

focus broadly on whether the trial

below constituted a "reliable adversarial

testing process." Id. at 4570.

Application of these principles to

the instant case leads directly to the

conclusion that the trial proceedings at

issue fell far short of the "reliable

adversarial testing process" envisioned

by this Court. By refusing to appoint an

independent psychiatric expert to examine

defendant with respect to his mental

state at the time of the offense, the

trial court effectively precluded him

from adducing evidence of his one

ostensibly viable defense, at both the

12 13guilt and penalty phases of trial*

12 Cf. United States v. Tucker, 716 F. 2d

576, 580 (9 Cir. 1983)(defense counsel was

ineffective in failing to pursue and pre

pare adequately defendant’s "only plausible

theory of defense [which was] readily

apparent.")

13 See, ê cj. , Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S.

(Footnote continued on next page)

-24-

Criminal convictions stemming from

trial proceedings similar to those in the

instant case, have consistently been

overturned on appeal. See, for

example, Brinks v. Alabama, 465 F. 2d

(Footnote 13 continued)

454, 472 (1981) ("A defendant may request

or consent to a psychiatric examination

concerning future dangerousness in the hope

of escaping the death penalty.")

In cases where a similar result

ensued from error or inaction on the part

of the defense attorney, criminal con

victions have been reversed, on the

grounds of ineffective assistance of

counsel. For example, in Wood v.

Zahradnick, 430 F . Supp. 107 (E.D. Va.

1977), aff'd 578 F. 2d 980 (4 Cir. 1978),

further proceedings at 611 F. 2d 1383

(4 Cir. 1980), the trial lawyer's failure

to obtain a mental examination of the

defendant in aid of a viable insanity

defense, was characterized by the court

as "so below the standard of reasonable

competence that it amounted to a

deprivation of [defendant's] Sixth Amend

ment right to counsel." 578 F. 2d supra

at 982. See also, Loe v. United States,

545 F. Supp. 662 (E.D. Va. 1982); and

Rivera v. Franzen, 33 Crim. L. Rptr. 2276

(N.D. 111. May 27, 1983), holding that a

defendant who claims ineffective assistance

of counsel due to his attorney's failure

to investigate an insanity defense, does

not have to show prejudice stemming from

(Footnote continued on next page)

-25-

446 (5 Cir. 1972), cert, den. 409 U.s.

1130 (1973), reh. den. 410 U.S. 960

(1973), a case closely analogous to the

instant matter on the issue of a state

judge's refusal to order a pre-trial

sanity investigation pursuant to state

law. The court found, based on the facts

before it, that the trial court "exceeded

the allowable range of its discretion"

under Alabama law in denying a motion

for a pre-trial sanity hearing brought by

defendant's attorney based on evidence

consisting of letters from lay witnesses

and the attorney's personal opinion

that his client "appeared to be insane."

Id. at 447. The appellate court stated:

(Footnote 14 continued)

such failure in order to prevail on

appeal. The court stated: "This Court

would be awash in a sea of speculation

were it to make a determination that a

colorable insanity defense . . . could not

have persuaded a jury that the petitioner

was insane and therefore not legally

responsible for his actions." Id. at 2277.

[A]part from his claim that

the state arbitrarily denied him

a sanity investigation, Brinks

advances a second argument which

necessitates reversing his

conviction. Under the due process

and equal protection provisions

of the Fourteenth Amendment and

the Sixth Amendment's guarantee

of effective legal counsel,

Brinks contends that, because

of his indigency, he was unable

to secure expert testimony to

present to the state court before

it considered whether there was

enough evidence to order a sanity

investigation. Had he been

affluent, or had the state provided

him with funds, Brinks claims

he could have introduced evidence

which would have compelled a

sanity investigation.

* * * *

Under these circumstances, we fail

to see how Brinks could have

received adequate representation

from his appointed attorney.

Moreover, the main thrust of the

argument of petitioner's counsel

in this court is that he could not

adequately represent petitioner

because of the lack of an available

expert witness. 44 8

(footnote omitted].

Cf. Porter v. Estelle, 709 F. 2d 944

(5 CirT~1983) , cert. den.~~sub nom.

Porter v. McKaskle, — U*S. , 52 U.S.L .W .

3825 (1984), where Justice Marshall,

dissenting from the denial of certiorari

in a capital case in which the trial court

(Footnote continued on next page)

-2b-

-27-

As noted above, Brinks is strikingly

similar to the instant case with respect

(Footnote 15 continued)

refused to order a psychiatric examination

to determine defendant's competency to

stand trial, stated:

[A] substantial body of both

medical evidence and evidence

pertaining to petitioner's behavior

cast doubt upon petitioner's

ability to comprehend the proceedings

against him. Surely the Court

of Appeals erred in concluding that

the cumulation of data was in

sufficient to entitle petitioner

to a competency exam. 52 U .S .L.W.,

supra, at 3826.

The dissent would grant certiorari

" [e]specially because the correct answer

to that question [i.e ., what is the

standard for determining when a trial judge

has a constitutional obligation to order

a psychiatric examination to determine

defendant's competency to stand trial]

determines whether petitioner lives or

dies [.]" Id. at 3825 (emphasis added).

See, in this regard, State v. Noel, 102

N.J.L. 659, 680, 133 A. 274, 283 (E. & A.

1926)("The law has always been zealous

in the protection of one who has lost

his reason . . . .To execute one bereft of

reason would afford no example to others.

It would be cruel and inhuman."

(Footnote continued on next page)

to the pre-trial insanity investigation

request on the part of the defendant.

The constitutional infirmities found by

the Brinks court as inherent in the

factual setting before it, likewise

should be found by this Court to inhere

in the situation under review here. Cf.

v. Oklahoma, 663 P. 2d 1, 8 (Okla.

Ct. Crim. APP. 1983). See also, State

y, Hamilton, 441 So- 2d 1192 ILa. Sup.

Ct. 1983), holding that defendant's

"constitutional right to present a

(Footnote 15 continued)

See also, Eddings_v

— U.S. — , 102 S_

Oklahoma,

C i U U J - i i H J w ‘ ----------- ------------------- '

_i] s - ,rur a. Ct. 869 (1984) , reieis-

i S T

violated the rule in Lockett v. Ohi2.

438 U.S. 586 (1978), that, in capital

cases7~the sentencer not he precluded

from considering "as a mitiaStiM «acto ,

nqnpct of a defendant's character or

record^" 438 U^. , supra at 604 (emphasis

in original) , quoted in Eddmgs, 10

S. Ct., supra at 874.

•. , r> I t r * - , v -•

-29-

defense [citing Washington v. Texas, 388

U.S. 14 (1967)]," id. at 1194, was

violated by the trial judge's exclusion

of "the unquestionably relevant testimony,"

id., of a psychiatrist offered by the

defense, in a case where " [d]efendant's

only viable defense was insanity," id.

Decisions by various federal courts

concerning applications for appointment

of independent experts under provisions

of the Criminal Justice Act of 1964, 18

_ 16U.S.C. S3006A(e) are instructive here;

in construing the scope and intent of

that statute, these courts have articula

ted principles and considerations which

support petitioner's contentions

18 U.S.C. §3006A(e) currently pro

vides, in pertinent part;

Counsel for a person who is

financially unable to obtain

investigative, expert, or other

services necessary for an ade

quate defense may request them

in an ex parte application.

Upon finding, after appropriate

(Footnote continued on next page)

-30-

here regarding access to independent

psychiatric expertise in aid of his

proffered insanity defense. See, for

example, United States v. Schultz, 431

F. 2d 907 (8 Cir. 1970) (the purpose of

the statute is "to provide the accused

with a fair opportunity to prepare and

present his case," id. at 911, an<̂

noting further that "the adversary system

(Footnote 16 continued)

inquiry in an ex parte pro

ceeding, that the services

are necessary and that the

person is financially unable

to obtain them, the court, or

the United States magistrate

if the services are required

in connection with a matter

over which he has jurisdic

tion, shall authorize counsel

to obtain the services. P.L.

91-447, §1, Oct. 14, 1970.

17 In the course of its analysis of this

issue, the court alluded to a portion of

the legislative history of the statute

as follows:President John F. Kennedy, in

transmitting proposals for this

type of legislation to Congress

wrote House Speaker John McCormack

of the great need for such enactment:

(Footnote continued on next page)

itsxl- *<■« — **“*•»*•

K̂WSS****: ■ pH1*' ^

-31-

cannot work successfully unless each

party may fairly utilize the tool of

expert medical knowledge to assist in

the presentation of this issue [mental

18competency] to the jury."

(Footnote 17 continued)

In the typical criminal

case the resources of

government are pitted

against those of the

individual. To guarantee

a fair trial under such

circumstances requires that

each accused person have

ample opportunity to gather

evidence, and prepare and

present his cause. Whenever

the lack of money prevents

a defendant from securing

an experienced lawyer,

trained investigator or

technical expert, an un

just conviction may follow.

2 U.S. Cong. & Admin. News

p. 2993 (1964). Id. at 909,

n. 2

18A further observation made by the

Schultz court is particularly pertinent

to the facts of the instant case, to

wit:

Schultz, in fact, never

had the benefit of any

psychiatric examination or

evaluation directly related

to his defense of insanity.

True, the Federal Medical

(Footnote continued on next page)

-32-

Both the result and the rationale

of the Schultz decision were subsequently

endorsed by other courts. See, e^g.,

States v. Theriault, 440 F. 2d

713 (5 Cir. 1971), cert den. 411 U^S.

984 (1973) (trial judge could not properly

deny appointment of an expert under

(Footnote 18 continued)

Center physicians examined

him to determine his com

petency to stand trial, but a

substantial difference may

exist between the mental

state which permits an

accused to be tried an

that which permits him to be

held responsible for a

crime. United States v.

Driscoll, 399 F. 2d 135

(2d Cir. 1968). Examination

for the purpose of

competency to stand trial

may require less exactness

than those examinations

designed to determine san

ity for the purpose of

criminal responsibility.

Id. at 912 (citations

omitted).

»

f' ~

“ -> *J —

-34-

18 U .S.C . S3006A(e) on the basis that an

earlier appointment had been made under

18 U.S.C. §4244 ^ on the issue of

defendant's competency to stand trial).

In his opinion concurring in the result,

Judge Wisdom stated:

I would read the statute . . .

as requiring authorization for

defense services when the

attorney makes a reasonable

request in circumstances in

which he would independently

engage such services if his

client had the financial means to

support his defenses. The

trial judge should tend to rely

on the judgment of the attorney

who has the primary duty of

providing an adequate defense.

440 F. 2d supra at 717.

19

18 U.S.C. §4244 authorizes a court,

under certain circumstances, to compel a

defendant to submit to psychiatric

examination for the purpose of determining

competency to stand trial; the results of

such examination are reported to the court.

See also, united States v. Chavis, 476

F. 2d 1137 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (18 U-S.C.

§3006A(e) "comprehends within its

definition of 'expert witness' the

assistance of a psychiatric expert in

preparing and presenting an insanity

defense," id. at 1141, and such expert

"is intended to serve the interests of

20

the defendant," id. at 1142), and

rini +• p>d states v. Bass, 477 F. 2d 723, 725

20 cf. United States v. Caldwell, 543

F 2d 1333 (D.C. Cir. 1975), cert, den

423 U.S. 1087 (1976), finding no error in

a trial judge's denial of defendant s pre

trial motion for examination by a

particular psychiatrist, which examination

would have been in addition to those given

earlier by court-appointed experts to

assess defendant’s competency to stand

trial. At the time of the motion, the

only issue before the trial court was

defendant's competency, leading the

appellate court to conclude: When the

trial court is satisfied that it can re

solve the issue of competence without

additional appointments, we cannot con

strue the failure to do so as a denial of

expert assistance for a substantive

defense of insanity." Id. at 1350.

However, the court underscored the

distinction between appointment of

(Footnote continued on next page)

-36-

-35-

(9 Cir. 1975) (an independent expert

should be appointed, pursuant to the

statute, "when the defense attorney makes

a timely request in circumstances in

which a reasonable attorney would engage

such services for a client having

independent financial means to pay for

them.")

(Footnote 20 continued)

psychiatrists to aid the presentation of

an insanity defense and such an appoint

ment to assist the court in determining

competence to stand trial." Id.

For an application of United States

v. Schultz in another context, see

United States v. Durant, 545 F. 2d 823

(2 Cir. 1976), finding reversible error

in the trial judge's refusal -- in a

case where fingerprint evidence was

"pivotal" — to appoint an independent

expert in that field on behalf of an

indigent defendant. The Court stated:

[T]he purpose of the [Criminal

Justice] Act, confirmed by its

legislative history, is clearly

to redress the imbalance in the

criminal process when the

resources of the United States

Government are pitted against an

indigent defendant . . . .

[T]he Act must not be emasculated

by niggardly or inappropriate

construction. Id. at 827

As noted above, although decided in

the context of claims under 18 U-S.C.

§3006A(e), cases such as these articulate

fundamental equitable principles which

should serve to guide this Court in its

disposition of defendant's constitutional

claims in the instant case. The "opportun

ity to present a meaningful defense

based on lack of criminal responsibility,"

Schultz, 431 F. 2d, supra at 912, was

clearly lacking here. The request for

an independent expert was, under the

circumstances, eminently reasonable and

appropriate. See, Theriault, 440 F. 2d

supra at 717 (Wisdom, J., concurring), and

Bass, 477 F. 2d, supra at 725. In short,

the equitable considerations which have

led courts to a liberal construction of

18 U.S.C. §3006A(e) — particularly in

insanity defense cases should lead to

a similarly favorable construction of

-37-

the constitutional claims of a criminal

defendant, under sentence of death, who

had no such statutory protection avail

able to him under the law of the State

21

in which he was tried.

Furthermore, the distinction between

examinations by court-appointed experts

to determine competency to stand trial,

and examinations by independent experts

appointed by the court at the government's

expense to aid in a defendant's presenta

tion of the insanity defense, as clearly

outlined in cases such as Schultz and

Caldwell, both supra, is pertinent here.

Further articulation of the distinction

Z JL See also, Matlock v. Rose. —

F. 2d — (6 Cir., April 9, 1984) , which

notes that "[t]he case law is still

developing on the scope of the

constitutional duty to supply experts,"

slip op. at 13, but states unequivocally:

"The need for psychiatric experts in a

case in which insanity is the only defense

is obvious [citing United States v. Taylor,

437 F. 2d 371 (4 Cir. 1971)] ," id. at 13,

n. 3

-38-

can be found in United States v. Alvarez,

519 F. 2d 1036 (3 Cir. 1975), in which

the court took great pains to delineate

the difference between the two types of ...... .

examination with particular regard to

the self-incrimination implications for

22

defendants subject to such procedures. •

22 Cf., Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S

supra, finding violations of both

Fifth and Sixth Amendment privileges in

the State's use — at the penalty phase

of a capital trial — of the contents

of defendant's disclosures made in the

course of a court-ordered psychiatric

examination to determine competency to . . . ... ..

stand trial; defendant had introduced no

psychiatric evidence on his own behalf at

trial. The Fifth Amendment violation

inhered in the State's effort to meet its

burden of proof of defendant's future

dangerousness by using defendant's

statements "unwittingly made without an

awareness that he was assisting the

State's efforts to obtain the death

penalty." Id. at 466. The Sixth Amend

ment violation was found to exist in the

denial to defendant of counsels

assistance in "making the significant

decision of whether to submit to the

examination and to what end the n

psychiatrist's findings could be employed.

Id at 471. In reaching these conclusions,

the Court noted, without elaboration,

that "a different situation arises where

(Footnote continued on next page)

*

-39-

The court found no violation of the

privilege against self-incrimination in

the government's use at trial of the

report and testimony of the psychiatrist

appointed pursuant to defendant's

application under 18 U.S.C. §3006A(e),

since — unlike examinations ordered under

18 U.S.C. §4244 — defendant's disclosures

to the §3006A(e) expert were "entirely

voluntary." Id. at 1045. However, the

court did find an inherent Sixth Amend

ment violation in such a situation, inso

far as an expert retained to assist a

defendant may be forced to be an in

voluntary government witness. The court

concluded: "The effect of such a rule

would, we think, have the inevitable effect

of depriving defendants of the effective

(Footnote 22 continued)

a defendant intends to introduce psychia

tric evidence at the penalty phase."

Id. at 472, 465-66, n. 10.

-40-

assistance of counsel in such cases.

Id. at 1046. This conclusion was pre

mised, in turn, upon the court's earlier

pronouncement that "[t]he effective

assistance of counsel with respect to

the preparation of an insanity defense

demands recognition that a defendant be

as free to communicate with a psychiatric

expert as with the attorney he is_

assisting ." Id. (emphasis added).

Accord, Noggle v. Marshall, 706 F. 2d

1408, 1413 (6 Cir. 1983), cert, den.

23

— ILJ3. --, 104 S. Ct. 530 (1983).

Finally, it is submitted that the

very nature of psychiatric expertise it

self necessitates subjecting such evidence

to rigorous "adversarial testing" before

the factfinder. Strickland v. Washington,

See also, State v. Kociolek, 23 N.J.

400 r 129 A. 2d 417 (1957); State v.

Hamilton, 44150^2d, supra.

(

.A ■

-41-

52 U.S.L.W., supra at 4570. See, in

this regard, Barefoot v. Estelle,

— U^S. — , 103 S. Ct. 3383 (1983), in

which this Court endorsed the validity

of psychiatric expert testimony on

questions of future dangerousness of

defendants in capital cases, specifically

relying on "the rules of evidence" and

"the adversary system," 103 S. Ct.

supra at 3397, to enable the factfinder

to accord such evidence its appropriate

O Aweight.

Rigorous "adversarial testing," in

turn, requires that the adversaries

themselves be equipped to handle

effectively both the direct presentation

See, Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. 418,

430 (1979), in which the Court alludes

to the "subtleties and nuances of

psychiatric diagnosis" which "render

certainties virtually meaningless" in the

context of civil commitment hearings at

which the issue is "whether the individual

is mentally ill and dangerous . . . and

. . . in need of confined therapy.[.]

-42-

of psychiatric evidence as well as

cross-examination of any experts

offered in opposition. Thus, "the

guiding hand of counsel," Powell v.

Alabama, 287 U.S. supra at 69, itself

requires guidance from the very experts

whose testimony is elicited — or

challenged — by counsel. In other words,

the blame for a suspect expert

opinion must be borne together

by the mental health professional

who presents it and the legal

professionals who wittingly allow

its uncontested presentation.

Poythress, "Psychiatric

Expertise in Civil Commitment:

Training Attorneys to Cope With

Expert Testimony," 2. L . & Hum.

Behav. 1, 18 (1978).^

It has been suggested, furthermore,

that as a general rule:

many lawyers possess scant

knowledge about psychiatric

decision-making, diagnoses,

and evaluation tools. This

shortcoming can seriously

impede their cross-examina

tion of expert witnesses.

Once psychiatric testimony

is elicited few lawyers

have the special skills to

evaluate such testimony.

(Footnote continued on next page)

-43- -44-

A defense attorney, in a criminal

trial involving the insanity defense,

who is realistically expected to fulfill

his proper role of adducing probative

evidence in support of his client's

claim and in challenging the State's

evidence, must acquire the requisite

psychiatric expertise to accomplish that

task. At least one commentator has

highlighted this imperative in insanity

trials:

Insofar as the psychiatrist's

decision to take one side or

the other on the responsibility

issue is based on pragmatic

considerations or expediencies

and not on the objective facts

about the illness, this raises

serious questions about expert

testimony on the issue of sanity/

(Footnote 25 continued)

Perlin and Sadoff, "Ethical

Issues in the Representation

of Individuals in the

Commitment Process," 45

L. & Contemp. Prob. 161, 166

(1983).

See also, Golten, "Role of Defense

(Footnote continued on next page)

insanity. For though it is his

special skill and training

which entitles him to testify

as an expert witness, the

psychiatrist's expert opinion

on the issue of insanity may

be a function of his personal

values and his own pragmatic

judgments, not a function of the

defendant's mental illness in

any objective sense. Poythress,

"Mental Health Expert Testimony:

Current Problems," 5 J. Psychiatry

& L. 201, 204 (1977)

Thus, defense counsel in insanity trials

must be prepared both to thrust and to

parry with psychiatric expert testimony.

"Cross-examination may suggest the

fallibility of the opposing psychiatrist

and the shortcomings of the psychiatric

profession. But calling to the stand a

psychiatrist who disagrees with the

opposing psychiatrist is an even better

way of forcing judges and juries to use

their common sense." Ennis and Litwack,

(Footnote 25 continued)

Counsel in the Criminal Commitment

Process," 10 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 385

(1972).

'••v. i .*'.*X*. .**v.

-45-

"Psychiatry and the Presumption of

Expertise: Flipping Coins in the Court

room," 62 Calif. L. Rev. 693, 746

26(1974).

Advocacy, alone, does not suffice.

Effective advocacy requires obtaining

75---------------------- --------

Without some knowledge of how

to effectively cross-examine

psychiatric expert testimony

or some appreciation of the

testimony of an independent

mental health examiner [an]

attorney . . .could offer only

a token defense for his client.

Poythress, 5 J.Psychiatry

& L., supra at 214.

See, generally, Ziskin, Coping With

Psychiatric and Psychological Testimony

(3d ed. 1981), for an in-depth survey

and analysis of deficiencies — and