Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellants; Correspondence from Wright to Ganucheau; from Pugh to McDuff; from Turner and Silver to Wright

Public Court Documents

January 2, 1990

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellants; Correspondence from Wright to Ganucheau; from Pugh to McDuff; from Turner and Silver to Wright, 1990. c198fa5a-f211-ef11-9f89-002248237c77. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/28fc2782-2940-4074-a407-bc4438a00f84/brief-for-the-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law-as-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-plaintiffs-appellants-correspondence-from-wright-to-ganucheau-from-pugh-to-mcduff-from-turner-and-silver-to-wright. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

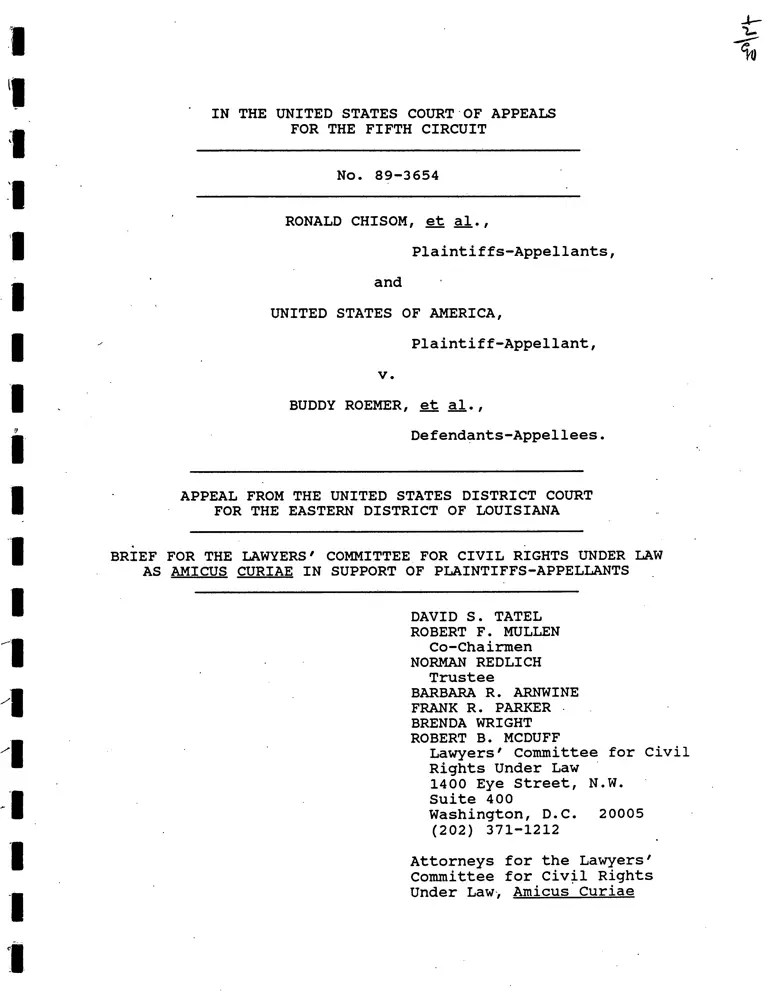

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-3654

RONALD CHISOM,

1

9

1

1

1

1

1

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

BUDDY ROEMER,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS .

DAVID S. TATEL

ROBERT F. MULLEN

Co-Chairmen

NORMAN REDLICH

Trustee

BARBARA R. ARNWINE

FRANK R. PARKER

BRENDA WRIGHT

ROBERT B. MCDUFF

Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for the Lawyers'

Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law, Amicus Curiae

1

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-3654

RONALD CHISOM,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

BUDDY ROEMER, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

DAVID S. TATEL

ROBERT F. MULLEN

Co-Chairmen

NORMAN REDLICH

Trustee

BARBARA R. ARNWINE

FRANK R. PARKER

BRENDA WRIGHT

ROBERT B. MCDUFF

Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for the Lawyers'

Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law, Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE 1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 2

ARGUMENT 4

I. PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED REDISTRICTING PLANS

FULLY SATISFY THE REQUIREMENTS OF

THORNBURG V. GINGLES AND SECTION 2 4

II. THE DISTRICT COURT EMPLOYED A FAULTY

ANALYSIS IN CONCLUDING THAT VOTING IS

NOT RACIALLY POLARIZED IN THE FIRST

DISTRICT 10

A. When Polarized Voting Prevents Blacks

From Electing Candidates Of Choice In

Black-Versus-White Contests, A Section Two

Violation Is Established Regardless Of The

Outcome Of White-Only Elections 10

B. Black Electoral Success In A Black-Majority

District Does Not Establish The Ability

of Blacks To Elect Candidates Of Choice

In A White-Majority District 15

CONCLUSION 17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Bradford County v. City of Starke, 712 F. Supp. 1523

(M.D. Fla. 1989)

Brown v. Thomson, 462 U.S. 835 (1983)

Campos v. City of Baytown, 840 F.2d 1240

(5th Cir. 1988), cert. denied,

109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989)

PAGE

13

5

13

Citizens for a Better Gretna V. City of Gretna,

834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987),

cert. denied, 109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989) 13, 15

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) OOO 2

Clark v. Edwards, No. 86-435-A

(M.D. La. Aug. 15, 1988) 14, 15

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977) 9

Dillard v. Baldwin County Board of Education,

686 F. Supp. 1459 (M.D. Ala. 1988) 9

Dillard v. Baldwin County Commission,

694 F. Supp. 836 (M.D. Ala.),

aff'd, 862 F.2d 878 (11th Cir. 1988) 8

East Jefferson Coalition v. Jefferson Parish,

691 F. Supp. 991 (E.D. La. 1988),

appeal pending 13, 15

Gomez v. City of Watsonville, 863 F.2d 1407

(9th Cir. 1988), cert. denied, 109 S.Ct.

1534 (1989) 13

Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332 (1975) 13

Jeffers v. Clinton, No. H-C-89-00

(E.D. Ark. Dec. 4, 1989) 9, 13

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County,

554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.) (en banc)

cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968 (1977) 8

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983) 15

Mallory v. Eyrich, 707 F. Supp. 947

(S.D. Ohio 1989) 13

Mandel V. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173 (1977) 12

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (con't)

PAGE

Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183

(S.D. Miss. 1987)

McNeil v. City of Springfield, 658 F. Supp. 1015

(C.D. In. 1987)

Neal v. Coleburn, 689 F. Supp. 1426

(N.D. Va. 1988)

13

13

9

Parnell v. Rapides Parish School Board,

425 F. Supp. 399 (W.D. La. 1976),

aff'd, 563 F.2d 180 (5th Cir.),

cert. denied, 438 U.S. 915 (1978) 15

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) 2

Smith v. Clinton, 687 F. Supp. 1310 (E.D. Ark.)

aff'd, 109 S Ct 548 (1988) 11, 12

Thornburg V. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) passim

Wallace v. House, 377 F. Supp. 1192

(W.D. La. 1974), aff'd in part. rev'd in part

on other grounds, 515 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1975),

vac'd on other grounds, 425 U.S. 947 (1976),

on remand 538 F.2d 1138 (5th Cir. 1976),

cert. denied, 431 U.S. 965 (1977) 15

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972),

aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095 (1973) 6

Westwego Citizens for Better Government V. Westwego,

872 F.2d 1201 (5th Cir. 1989) 13

STATUTES:

Voting Rights Act, § 2, 42 U.S.C. §1973,

as amended passim

iii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-3654

RONALD CHISOM,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

BUDDY ROEMER,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law is a non-

profit organization established in 1963 at the request of the

President of the United States to involve leading members of the

bar throughout the country in the national effort to assure civil

rights to all Americans. Protection of the equal voting rights

of all citizens has been an important component of the

Committee's work. It has provided legal representation to

litigants in numerous voting rights cases throughout the nation

1

over the past twenty-five years, and it has submitted amicus

curiae briefs in major voting rights •cases before the Supreme

Court. See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986); Rogers v.

Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982); City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55

(1980).

The present case involves a challenge to multimember

elections under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§1973. The case involves significant issues concerning the

interpretation and application of Section 2, and may •have far-

reaching ramifications for other voting rights cases. Because of

the Committee's extensive and ongoing representation of minority

citizens in the voting rights area, it has a strong interest in

the outcome of this case and its effect on minority citizens in

other jurisdictions.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case challenges the use of a multimember district to

elect two Justices of the Louisiana Supreme Court as a violation

of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973, as

amended. The litigation presents a classic case of unlawful

dilution of the voting strength of minority citizens. Louisiana

uses single-member districts to elect all of the members of the

Louisiana Supreme Court, with the exception of the members from

the First Supreme Court District. The First District contains

the largest black population concentration in Louisiana, but is

2

structured as a two-member election district in a manner that

submerges that black population concentration in a majority white

district. No black Supreme Court justice has been elected to the

Louisiana Supreme Court in this century.

The district court entered judgment dismissing plaintiffs'

claims following trial of the action. While the district court's

judgment for defendants rests on numerous misconceptions about

the proper application of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

this brief limits itself to addressing only two fundamental

errors that are particularly important to the adjudication of

Section 2 cases. First, the brief discusses the reasons why the

district court erred in holding that plaintiffs were foreclosed

from obtaining relief under Section 2 because the black

population allegedly is not sufficiently large and geographically

compact to form a majority in a single-member district. Second,

the brief addresses the standards employed by the district court

in analyzing the existence of racially polarized voting, and

demonstrates that the district court's conclusions are in

conflict with controlling decisions of the Supreme Court as well

as of this Court. With respect to all other errors discussed by

the plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenor United States in their

briefs, amicus joins in those briefs and urges reversal on the

grounds stated there as well.

3

ARGUMENT

I. PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED REDISTRICTING PLANS FULLY SATISFY

THE REQUIREMENTS OF THORNBURG V. GINGLES AND SECTION 2.

The district court erroneously held that plaintiffs'

proposed redistricting alternatives were unacceptable and that

plaintiffs therefore could not satisfy the first threshold factor

set forth in Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) -- that the

minority group must "be sufficiently large and geographically

compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district."

478 U.S. at 50 (footnote omitted). The district court's decision

on this issue, if sustained, would transmute the straightforward

inquiry called for by Gingles into an all-purpose roadblock to

relief for Section 2 plaintiffs.

Plaintiffs' proof included undisputed figures demonstrating

that the two-member First Supreme Court District could be divided

into two single-member districts, one of which would consist of

Orleans Parish and have a black registered voter majority of 53.6

percent, 1 and the other of which would consist of Jefferson, St.

Bernard, and Plaquemines Parishes and have a white registered

1 Louisiana, unlike most states, maintains voter

registration statistics broken down by race of voter. The

existence of such records makes it possible for plaintiffs to

establish in this case that black citizens would constitute a

majority of the registered voters in the proposed single-member

district. Such proof is more than adequate to satisfy Gingles'

requirement that Section 2 plaintiffs establish the potential to

elect candidates of choice in a proposed single-member district.

478 U.S. at 50 n.17. Of course, the fact that registered voter

statistics are available by race in some cases does not mean that

proof of a black registered voter majority is necessary to make

out a successful Section 2 claim where such data is unavailable;

nothing in Gingles or amended Section 2 establishes such a

requirement.

4

voter majority. RE 16 (Table 4). 2 These two districts would

have total populations of 557,515 and 544,738, respectively. RE

16 (Table 2). Both districts would therefore be comfortably in

the middle of the population range of the other existing Supreme

Court districts. 3

The district court's criticisms of plaintiffs' proposed

single-member plan do not remotely justify the holding that

plaintiffs failed to satisfy the first Gingles factor. First,

there is no authority for the court's criticism of plaintiffs'

plan based on its deviations from ideal population size. 4 The

one-person, one-vote requirement of the Fourteenth Amendment does

2 "RE" refers to the Record Excerpts filed with plaintiffs'

brief.

3 Under plaintiffs' plan, the Supreme Court districts would

have the following total population rankings (see RE 15-16):

Fifth District 861,217

Third District 692,974

Second District 582,223

Orleans District 557,515

Sixth District 556,383

Jefferson/Plaquemines

St.Bernard District 544,738

Fourth District 410,850

4 The terms "ideal population" or "ideal district" are

routinely used in one-person, one-vote litigation. See, e.g.,

Brown v. Thomson, 462 U.S. 835, 839 (1983). The terms simply

refer to the population figure that results from dividing the

total population in a particular political unit by the total

number of representatives elected for that political unit. In

this case, the ideal district size for Louisiana Supreme Court

districts is 600,843, calculated by taking the total population

of the state reported in the 1980 United States Census

(4,205,900) and dividing by the total number of Supreme Court

justices (seven). RE 17 n. 19. Of course, the term "ideal

district" in this context refers merely to the mathematical ideal

and not to any normative ideal.

5

not apply to judicial elections in light of the Supreme Court's

affirmance of Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972),

aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095 (1973). Thus, the district court's

objections to population inequality in plaintiffs' proposed

districting alternative have no basis in federal policy.

The district court's objections cannot be based on state

policy either. It is undisputed that Louisiana is currently

content with a Supreme Court districting plan that has a total

deviation of nearly 75% and an average deviation of 19.55%. RE

17. Also undisputed is the fact •that the two single-member

districts proposed by plaintiffs would have deviations from ideal

population of only -7.2 percent (Orleans district) and -9.3

percent (Jefferson/Plaquemines/St. Bernard district) -- smaller

deviations than four of the six existing districts. RE 17.

Plainly, any state policy which says that a particular population

deviation is permissible in a districting plan that contains no

majority black districts, but is impermissible when it emerges

from a plan that would create a majority black district, would

not be worthy of deference. Indeed, such a policy would itself

be discriminatory and subject to challenge under Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act. Lack of population equality in plaintiffs'

proposed plan thus provides no basis for rejecting the plan and

barring plaintiffs' Section 2 claim.

The district court also erred in adjudging plaintiffs'

proposal unacceptable because it would for the first time create

a one-parish Supreme Court district. That objection simply

6

misconstrues the inquiry required by Ginales at the liability

stage of a Section 2 case. Any redistricting alternative

proposed by a Section 2 plaintiff will necessarily involve some

changes in previous state districting practices, but that fact

hardly suffices to invalidate the plan. Gingles certainly

articulated no such standard, but merely held that at the

liability stage a minority group must show that it is

sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a

majority in a single-member district. Here, plaintiffs'

undisputed showing that blacks would constitute a majority of the

registered voters in Orleans Parish, a political unit already

recognized under state law, more than suffices to meet this

requirement of Gingles. 5 The fashioning of a specific remedial

plan, and the weighing of any genuine state policy concerns

against the necessity of providing a full and complete remedy for

a Section 2 violation, properly should await the remedial stage

of the litigation.

Moreover, there is no substantial evidence that the creation

of a one-parish Supreme Court district would contravene any

genuine state "policy." Louisiana currently does not require

statewide uniformity in its districting arrangements for Supreme

5 Plaintiffs and the United States also presented evidence

that an alternative black registered voter majority district

could be created by combining Orleans Parish with contiguous

areas of Jefferson Parish. See Pl. Ex. 2; United States Ex. 14.

The two single-member districts thus created would also have

population deviations well below the average deviation of the

current Supreme Court districts. This alternative also complies

with the requirements of Ginales factor 1.

7

Court elections, given that most of the Supreme Court judicial

districts are single-member districts while the First District

alone is a multi-member district. Furthermore, no state

constitutional provision or statute prohibits •the •creation of

single-parish districts. In addition, as the district court

noted, the state itself proposed in the court below that a fairly

drawn plan would include a Jefferson Parish-only district -- a

configuration that would prevent the creation of a black majority

district. RE 18-19. Finally, Orleans Parish is already a

recognized political unit within which numerous elections are

held, and no state policy appears to be contravened by the fact

that the adjoining parishes of Jefferson, Plaquemines and St.

Bernard are not included in such elections.

In any event, even if it rose to the level of a genuine

state policy, the previous practice of using multi-parish

districts for Supreme Court elections simply cannot not carry the

weight the district court assigned to it. Other types of

articulated state and local districting policies are not given

the type of absolute precedence over minorities' voting rights

that the court extended here. See, e.g., Kirksey v. Board of

Supervisors of Hinds County, 554 F.2d 139, 151 (5th Cir.) (en

banc), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968 (1977) (policy of having county

supervisory districts with approximately equal road and bridge

responsibility cannot be given overriding weight "at the expense

of effective black minority participation in democracy"); Dillard

v. Baldwin County Commission, 694 F. Supp. 836, 844 (M.D. Ala.),

8

aff'd, 862 F.2d 878 (11th Cir. 1988) (policy of preserving pre-

existing political boundaries did not outweigh requirement of

fashioning an effective remedy for a Section 2 violation);

Jeffers v. Clinton, No. H-C-89-00, p. 24 (E.D. Ark. Dec. 4, 1989)

(three-judge court) (same); Neal v. Coleburn, 689 F. Supp. 1426,

1437 (N.D. Va. 1988) (lack of adherence to ideal standard of

compactness does not require rejection of proposed remedial plan

in Section 2 case); Dillard v. Baldwin County Board of Education,

686 F. Supp. 1459 (M.D. Ala. 1988) (same). Cf. Connor v. Finch,

431 U.S. 407, 419-420 (1977) (in case to which one-person, one-

vote requirement applies, state policy of maintaining county

lines is outweighed by need to achieve federal requirement of

population equality).

Rejection of a Section 2 claim on grounds that plaintiffs

cannot satisfy the first Gingles factor of population size and

compactness is a particularly serious step because it forecloses

relief even where plaintiffs can demonstrate that voting is

severely polarized along racial lines and that minorities have no

opportunity to elect candidates of choice under the challenged

system. The rationales advanced by the district court for

rejecting plaintiffs' plan are wholly inadequate to justify such

a step in this case, and the district court's decision should be

reversed on this ground.

9

II. THE DISTRICT COURT EMPLOYED A FAULTY ANALYSIS IN

CONCLUDING THAT VOTING IS NOT RACIALLY POLARIZED IN THE

FIRST DISTRICT.

At trial, plaintiffs presented overwhelming and largely

undisputed evidence that voting in black-versus-white judicial

contests within the First District is heavily polarized by race,

black candidates receiving consistently high levels of support

from black voters and consistently low levels of support from

white voters. See Plaintiffs' Brief, pp. 8-9, 34-36; Brief of

United States, pp. 6-14, 28-32; RE 55-57. The district court,

however, virtually ignored this evidence, focusing instead on

elections involving only white candidates. The few black-versus-

white contests discussed by the court consisted primarily of

races in Orleans Parish where, unlike in the First District,

blacks constitute a majority of the registered voters. RE 16.

The court's conclusions about racially polarized voting in

the First District are fundamentally flawed because of its

emphasis on white-only elections and the success of black

candidates in majority-black Orleans Parish. The legal errors in

each of these aspects of the court's decision are discussed in

the following sections.

A. When Polarized Voting Prevents Blacks From Electing

Candidates Of Choice In Black-Versus-White Contests, A

Section Two Violation Is Established Regardless Of The

Outcome Of White-Only Elections.

In light of controlling Supreme Court decisions as well as

precedent in this Circuit, it is no longer an open question

whether black-versus-white elections are the proper focus of

10

analysis in determining the existence of racially polarized

voting. The Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles analyzed only

black-versus-white contests in concluding that plaintiffs had

satisfied their burden of proving legally sufficient polarized

voting in North Carolina legislative elections. 478 U.S. at 58-

61. Moreover, the Supreme Court was squarely presented with the

question of whether polarization in black-versus-white contests

is the proper focus under Section 2 when the Court summarily

affirmed the decision of a three-judge court in a later case,

Smith v. Clinton, 687 F. Supp. 1310 (E.D. Ark.) (three-judge

court), aff'd, 109 S.Ct. 548 (1988).

In Smith v. Clinton, the court found that voting was heavily

polarized in black-versus-white contests. The defendants

countered with proof that in 54 of 65 races analyzed, primarily

consisting of white-on-white contests, the candidate receiving a

majority of the black vote placed first. Defendants' evidence

further showed that the first-place finisher in all of the

elections analyzed had received, on average, a greater share of

the black vote than of the white vote. 687 F. Supp. at 1316.

The Smith court nevertheless rejected defendants' contention

that this pattern of success for black-supported candidates in

white-only elections negated plaintiffs' proof of polarization in

black-versus-white elections, stating: "We find . . that there

is racially polarized voting in the district, despite the fact

that blacks and whites often prefer the same candidate in races

involving only whites." Id. at 1317. To hold otherwise, the

11

court observed, would improperly relegate blacks to a system in

which N[c]andidates favored by blacks can win, but only if the

candidates are white." Id. at 1318.

The defendants appealed to the Supreme Court, including in

their jurisdictional statement the following question:

Whether the court below improperly based its finding

that the multimember legislative district violated

Section II (sic] of the Voting Rights Act solely upon

evidence of racially polarized voting in eight black

versus white elections and upon the fact that no black

had previously won a seat in the Arkansas House of

Representatives from the district in issue. 6

A unanimous Supreme Court summarily affirmed the judgment of the

three-judge court. 109 S.Ct. 548 (1988).

The Supreme Court's summary affirmance is binding on lower

courts presented with the same issue. As the Court stated in

Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173, 176 (1977): •

Summary affirmances . . . without doubt reject the

specific challenges presented in the statement of

jurisdiction and do leave undisturbed the judgment

appealed from. They do prevent lower courts from

coming to opposite conclusions on the precise issues

presented and necessarily decided by those actions.

The summary affirmance in Smith falls squarely within this rule.

In Smith, the issue of whether black-versus-white elections are

the proper focus of inquiry in examining racially polarized

voting was clearly presented in the jurisdictional statement and

necessarily had to be decided in plaintiffs' favor in order for

the Court to affirm the judgment. Thus, Smith's holding is

6 A copy of the jurisdictional statement is attached to this

brief as Appendix A.

12

binding on this issue. See also Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332,

343-45 (1975).

Even prior to the Supreme Court's affirmance of Smith, this

Court had squarely held that the existence of racially polarized

voting is properly determined by analysis of black-versus-white

contests. Campos V. City of Baytown, 840 F.2d 1240, 1245 (5th

Cir. 1988), cert. denied, 109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989) ("the district

court properly focused only on those races that had a minority

member as a candidate"); Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of

Gretna, 834 F.2d 496, 503-04 (5th Cir. 1987), cert. denied, 109

S.Ct. 3213 (1989). This Court elaborated on the basis for this

holding in Westwego Citizens for Better Government v. Westwego,

872 F.2d 1201 (5th Cir. 1989):

As we noted in the Gretna case, when there are only

white candidates to choose from it is 'virtually

unavoidable that certain white candidates would be

supported by a large percentage of . . . black voters.'

834 F.2d at 502. Evidence of black support for white

candidates in an all-white field, however, tells us

nothing about the tendency of white bloc voting to

defeat black candidates. Id.

872 F.2d at 1208 n.7. 7 The district court disregarded these

7 See also Jeffers v. Clinton, pp. 27-28 (analysis of

polarized voting should focus on black-versus-white contests);

Bradford County v. City of Starke, 712 F. Supp. 1523, 1540 (M.D.

Fla. 1989) (same); Mallory v. Eyrich, 707 F. Supp. 947, 951 (S.D.

Ohio 1989) (same); East Jefferson Coalition v. Jefferson Parish,

691 F. Supp. 991 (E.D. La. 1988), appeal pending (same); Martin

v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183, 1194 (S.D. Miss. 1987); McNeil V.

City of Springfield, 658 F. Supp. 1015, 1030 (C.D. Ill. 1987)

(same); Gomez v. City of Watsonville, 863 F.2d 1407 (9th Cir.

1988), cert. denied, 109 S.Ct. 1534 (1989) (without discussing

issue, affirms portion of district court decision which found

racially polarized voting based on analysis of Hispanic-versus-

white contests only).

13

controlling authorities, making no mention of their discussion of

the relative probative value of black-versus-white and white-

versus-white elections.

Finally, the district court's finding of no racially

polarized voting in this case, based on analysis of white-only

elections, stands in sharp contrast to the district court's

findings in Clark v. Edwards, No. 86-435-A (M.D. La. Aug. 15,

1988), a Section 2 action challenging the at-large election of

district court, court of appeal, and family court judges in

numerous Louisiana districts and parishes, including parishes

within the First Supreme Court District. In Clark, the district

court found racially polarized voting in 47 out of 52 black-white

judicial elections analyzed, which included 30 black-white

elections in Orleans and Jefferson Parishes. Clark, Mem.

Decision at p. 26. These Orleans and Jefferson elections are

among the elections listed in Table 3 of the appendix to the

district court's opinion in this case (RE 55-57).

Thus, virtually the same evidence concerning black-versus-

white judicial contests within the First Circuit was presented to

the district courts in this case and in Clark. The Clark court,

however, in deference to this Court's precedents, correctly held

that this evidence demonstrated racially polarized voting and

that defendants' evidence concerning white-only elections could

not negate the showing of racially polarized voting in black-

14

versus-white contests. Id. at p. 31. 8 The Clark decision thus

underscores the error committed by the district court in this

case through its misplaced emphasis on white-only elections.

For all of these reasons, the district court's reliance on

white-only elections for its conclusion that black voters can

elect candidates of choice to the Supreme Court in the First

District was improper and requires reversal.

B. Black Electoral Success In A Black-Majority District

Does Not Establish The Ability of Blacks To Elect

Candidates Of Choice In A White-Majority District.

The black-versus-white elections which the district court

did discuss were confined primarily to elections in Orleans

Parish where blacks have had some electoral success. RE 34-37,

43-44. Unfortunately, the court drew the wrong conclusion from

these elections because it failed to recognize that Orleans

Parish has a black registered voter majority, whereas the First

District which is under challenge here has a clear white majority

of approximately 68 percent. RE 16. The undisputed proof in

8 Indeed, the district court's finding of no racially

polarized voting in this case stands in isolation from the many

cases finding racially polarized voting in numerous Louisiana

jurisdictions. See, in addition to Clark, Major v. Treen, 574 F.

Supp. 325, 337-38 (E.D. La. 1983) (three-judge court); Citizens

for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna; East Jefferson Coalition

v. Parish of Jefferson; Parnell v. Rapides Parish School Board,

425 F. Supp. 399, 405 (W.D. La. 1976), aff'd, 563 F.2d 180 (5th

Cir.), cert. denied, 438 U.S. 915 (1978); Wallace V. House, 377

F. Supp. 1192, 1197 (W.D. La. 1974), aff'd in part, rev'd in part

on other grounds, 515 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1975), vac'd on other

grounds, 425 U.S. 947 (1976), on remand 538 F.2d 1138 (5th Cir.

1976), cert. denied, 431 U.S. 965 (1977).

15

this case shows that black candidates have never received white

votes in sufficient numbers to obtain a majority of the votes in

the First District. See Plaintiffs' Brief, pp. 40-41.

Obviously, the hypothesis that voting is racially polarized

is only strengthened, not weakened, by proof that black

candidates have greater success in black-majority districts than

in white-majority districts. 9 Thus, black electoral success in

Orleans Parish can in no way establish the ability of blacks to

elect Supreme Court candidates of choice in the First District,

and the district court clearly erred in so holding.

9 Even in Orleans Parish the evidence showed that black

electoral success in judicial elections was far from monolithic;

of 32 black-white judicial elections in Orleans Parish listed in

Table 3 of the Appendix to the court's opinion, only six produced

a winning black candidate. RE 55-57.

16

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, and on the basis of the

authorities cited, the district court's ruling in favor of

defendants should be reversed.

Respectfully subm*tted,

/ i /. , ,

DAVID S. TATEL

ROBERT F. MULLEN

Co-Chairmen

NORMAN REDLICH

Trustee

BARBARA R. ARNWINE

FRANK R. PARKER

BRENDA WRIGHT

ROBERT B. MCDUFF

Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for the Lawyers'

Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law, Amicus Curiae

17

APPENDIX A

No

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

• OCTOBER TERM, 1988

BILL CLINTON, GOVERNOR OF ARKANSAS,

BILL MCCUEN, SECRETARY OF STATE OF ARKANSAS, AND

STEVE CLARK, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ARKANSAS,

IN THEIR RESPECTIVE OFFICIAL CAPACITIES AND IN

THEIR OFFICIAL CAPACITIES AS MEMBERS OF THE

BOARD OF APPORTIONMENT OF THE STATE OF ARKANSAS',

LILBURN W. CARLISLE, CHAIRPERSON OF THE ARKANSAS

STATE COMMITTEE OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY;

TOMMYE S. GIVENS, SECRETARY OF THE ARKANSAS

STATE COMMITTEE OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY; THE

DEMOCRATIC CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF CRITTENDEN

COUNTY, ARKANSAS, ITS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS; THE

REPUBLICAN CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF CRITTENDEN

COUNTY, ARKANSAS, ITS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS; AND

THE ELECTION COMMISSION OF CRITTENDEN COUNTY,

ARKANSAS, ITS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS Petitioners

VS.

ELBERT SMITH, VICKIE MILES ROBERTSON,

JOHNNY MAE WILLIAMS, MAXINE BOHANNON, CAROLYN

STEPHENSON, ESTER CAGE, FAYE W ILLIAMS, DARRICK

HANDY, ANTHONY R. HOLMES, CAROL HOLMES,

AND MAGGIE HALL Respondents

APPEAL FROM

THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

WESTERN DIVISION

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

JOHN STEVEN CLARK

Attorney General

FRANK J. W ILLS, III

Assistant Attorney General

TIM HUMPHRIES

Assistant Attorney General

200 TOWER BLDG., 4TH & CENTER

• LITTLE Rom AR 72201

KENT RuBENS

Attorney at Law

P.O. Box 768

WEST MEMPHIS, AR 72301

Attorneys for Petitioners

ARKANSAS LEGISLATIVE DIGEST, INC.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I.

WHETHER THE COURT BELOW IMPROPERLY PER-

MITTED A CLAIM UNDER SECTION II OF THE

VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF 1965, AS AMENDED, 42 U.S.C.

§1973, TO BE MAINTAINED AGAINST ONE DISTRICT

OF A STATEWIDE ELECTION SYSTEM AS DISTIN-

GUISHED FROM THE ENTIRE SYSTEM ITSELF.

WHETHER THE COURT BELOW IMPROPERLY

EXPEDITED THIS ACTION AND CONDUCTED A

TRIAL ON THE MERITS LESS THAN THREE AND ONE

HALF MONTHS AFTER PLAINTIFFS FILED THEIR

COMPLAINT, THUS DEPRIVING PETITIONERS OF AN

OPPORTUNITY TO PREPARE ADEQUATELY.

WHETHER THE COURT BELOW IMPROPERLY BASED

ITS FINDING THAT THE MULTIMEMBER LEGISLA-

TIVE DISTRICT VIOLATED SECTION II OF THE

VOTING RIGHTS ACT SOLELY UPON EVIDENCE OF

RACIALLY POLARIZED VOTING IN EIGHT BLACK

VERSUS WHITE ELECTIONS AND UPON THE FACT

THAT NO BLACK HAD PREVIOUSLY WON A SEAT IN

THE ARKANSAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

FROM THE DISTRICT IN ISSUE.

IV.

WHETHER THE COURT IMPROPERLY VOIDED THE

MARCH 8, 1988 PRIMARY ELECTION AND ORDERED A

SPECIAL PRIMARY ELECTION, WHICH IS TO BE

HELD ON SEPTEMBER 20, 1988. WHEN THERE WAS NO

11

EVIDENCE OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN THE

ELECTORAL PROCESS IN QUESTION AND THERE

WAS NO EVIDENCE OF LOW VOTER PARTICIPATION

IN THE BLACK COMMUNITY.

V.

WHETHER THE COURT BELOW IMPROPERLY

ADDED NEW PARTIES DEFENDANT, SUA SPONTE, IN

ITS JULY 1, 1988 JUDGMENT WHEN THOSE NEW

DEFENDANTS HAD NOT PARTICIPATED IN ANY OF

THE PROCEEDINGS PRIOR TO THE ENTRY OF

JUDGMENT.

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

In addition to the parties listed in the caption of this

action, the following are parties to this proceeding:

Democratic Central Committee of Crittenden County,

Arkansas: Solon Anthony, Howard Atkins, Primo

Baioni, Jimmy Barham, Earl Beck, Al Boals, Cy Bond,

Darla Brasfield, 011ie Brown, Milio Brunetti, Buddy

Burgos, John Criner, Zelma Danton, Berrell Fair, Frank

Fogleman, John Gregson, Frank Hill, Paul Matthews,

Paul O'Neal, June Paudert, MacCRay, Marvin Rogers,

Mike Sample, Dave Thomas, Charlie Wah, Erma Whit-

acre, and Marge Woolfolk.

Republican Central Committee of Crittenden County,

Arkansas: Joe Baker and Mrs. Barbara Dodge.

Election Commission of Crittenden County, Arkansas:

Joe Baker, Kent Rubens, and David Thomas.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have this day mailed two copies of

the foregoing brief to the following counsel:

Judith Reed

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Roy Rodney, Jr.

McGlinchey, Stafford, Mintz,

Cellini & Lang

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

William P. Quigley

901 Fulton Place, Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

Ronald L. Wilson

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

Jessica Dunsay Silver

Irving Gornstein

U.S. Department of Justice

P.O. Box 66078

Washington, D.C. 20035-6078

Robert G. Pugh, Sr., Esq.

330 Marshall Street

Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

/

This the day of January, 1990.

William J. Guste, Jr.

Attorney General

Louisiana Department

of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue

Suite 700

New Orleans, LA 71101

George M. Strickler

639 Loyola Street

Suite 1075

New . Orleans, LA 70113

Peter J. Butler

201 St. Charles AVenue

35th Floor

New Orleans, LA 70170

Moon Landrieu

717 Girod Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

"Th

Brenda Wright

• Iva

LAWYERS' COMMI [lEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

SUITE 400 • 1400 EYE STREET, NORTHWEST • WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005 • PHONE (202) 371-1212

CABLE ADDRESS: LAWCIV, WASHINGTON, D.C.

TELEX: 205662 SAP UR

FACSIMILE: (202) 842-3211

January 2, 1990

Honorable Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Clerk of the Court

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

600 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Re: Chisom and U.S. V. Roemer

No. 89-3654

Dear Mr. Ganucheau:

Enclosed please find for filing seven copies of the brief

amicus curiae of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law, filed in support of the plaintiffs-appellants in the above-

captioned case. The consents of the parties to the filing of the

brief are enclosed.

Very truly yours, ,

Brenda Wright

Enclosures

cc: All Counsel

• g6 a ge

/ 6 .yaw

t9fizte, 2100, 55,3 e/x-ez,d. t9gie-Z

Zazariza, 7110/-5502

g20/,„w

December 13th, 1989

Robert B. McDuff, Esquire

Lawyer's Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

Suite 400

1400 Eye Street Northwest

Washington D.C. 20005

Re: Chisom and U.S. vs. Roemer, et al

89-3654

Dear Mr. McDuff:

This will acknowledge and confirm that I have

no objection to an amicus curiae being filed by you on

behalf of the Lawyer's Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law.

Yours4 very truly,

Robert G. Pugh

RGP/mp

cc: Ms. Joan Perkins, Case Manager

Clerk's Office, United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

(ii) 227-2270 nbevfre- (i/(5) 227-2275

12/28/89 13:04 22202 633 2490 DOJ.CRD.APP. a002

• U.S. Depliment of Justice

Civil Rights Division

AppeC=esam

P.O. Bar 66C78

Warkingrost, D.0 200154078

December 28, 1989

ITs. Brenda Wright

Lawyers Committee for civil Rights

Under Law

1400 I Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

Re: Chisom and United States V. Roemer, No. 89-3654

Dear MS. Wright:

On behalf of

hereby consent to

Lawyers Committee

the

the

for

United States, appellant in this action, we

filing of a brief as amicus curiae by the

Civil Rights Under Law on January 2, 1990.

Yours truly,

James P. Turner

Acting Assistant. Attorney General

Civil Rights Division

1 T"*....S.s

By: jt.,W0_, 3Lef'

Jessica Dunsay Silver

Deputy Chief

Appellate Section

• RECEly7 NOV 2 7 1989

November 16, 1989

Mr. Robert B. McDuff

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law

Suite 400

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Re: Chisom v. Roemer

No. 89-3654

Dear Mr. McDuff:

This letter will confirm that

plaintiffs-appellants consent to the filing

of an amicus brief in the Fifth Circuit by

the Lawyers' Committee.

Very truly yours,

AL,6-100

.6dith Reed

JR:aa

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET, 16th FLOOR • (212) 219-1900 • NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013