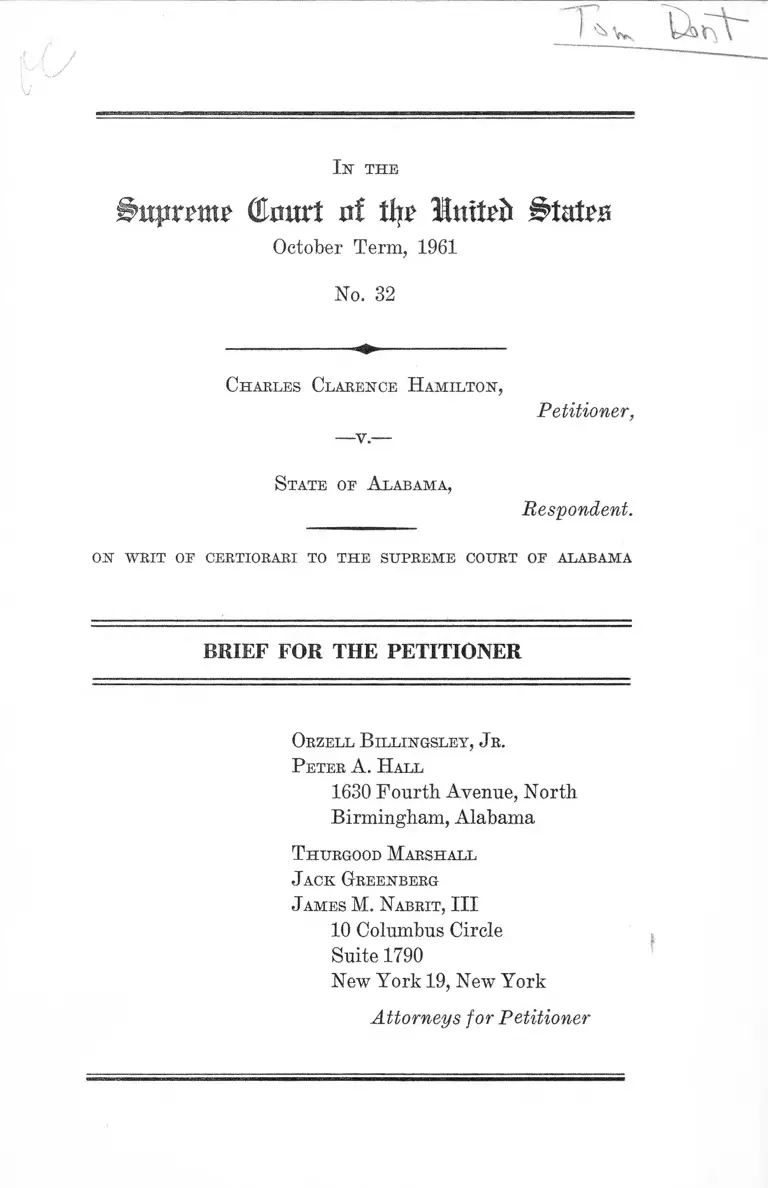

Hamilton v. Alabama Brief for the Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hamilton v. Alabama Brief for the Petitioner, 1961. b3946b3a-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2956c429-1b46-497e-81f6-3d5c3bacd2a9/hamilton-v-alabama-brief-for-the-petitioner. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Supreme Cmtrt nt % Intted States

October Term, 1961

No. 32

Charles Clarence H amilton,

Petitioner,

—v.—

S tate oe Alabama,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OE CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OE ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

Orzell B illingsley, J r.

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 1790

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Petitioner

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion Below............................. „.......... .... .............. 1

Jurisdiction __ 1

Questions Presented................. ................................. . 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved__ 3

Statement ............................ 4

Summary of Argument............... ......... ...... ................ 15

Argument ...................... 17

I. The right of counsel during all stages of crim

inal proceedings where the death penalty may be

imposed is so fundamental that it should not

be limited at. any point by a rule requiring

demonstration of the amount of prejudice result

ing from denial of representation at a particular

stage ......... ............ .................... ......................... 17

II. Even if, arguendo, showing of “disadvantage” is

required such amply appears of record.............. 25

Conclusion .................................. ........ ........................ 36

Appendix A ................ ......... .............................. .......... la

Appendix B 11a

11

T able op Cases

page

Abel v. United States, 362 U. S. 217, 341..................... 32

Aiola v. State, 39 Ala. App. 215, 96 So. 2d 816 (1957) 33

Arrington v. State, 253 Ala. 178, 43 So. 2d 644 (1949) 22

Batchelor v. State, 189 Ind. 69,125 N. E. 773 (1920) .... 12a,

Betts v. Brady, 316 U. S. 455 ................................19, 20, 21

Bibb County v. Hancock, 211 Gfa. 429, 86 S. E. 2d 511

(1955) ........................................................................ 13a

Bienville Water Supply Co. v. City of Mobile, 186 U. S.

212 ........................................................................... 11,27

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U. S. 199............................ 24

Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616............................ 24

Brandt v. Hudspeth, 162 Kan. 601, 178 P. 2d 224

(1947) ........................................................................ 11a

Bute v. Illinois, 333 U. S. 680 ......... ............................ 20

Bryant v. State, 218 Md. 151,145 A. 2d 777 (1958)...... 14a

Ex parte Burns, 247 Ala. 98, 22 So. 2d 517 (1945)...... 11, 27

Calhoun v. Commonwealth, 301 Ky. 789, 193 S. W. 2d

420 (1946) ................................................................ . 12a

Canizio v. New York, 327 U. S. 82 .........................20, 21, 35

Cash v. Culver, 358 U. S. 633 ....................................... 20

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 ................................ . 24

Council v. Clemmer, 177 P. 2d 22 (D. C. Cir. 1949) ....21, 35

Crooker v. California, 357 U. S. 433 ............................ 21

Edwards v. Nash, 303 S. W. 2d 211 (Kansas City C. A.

1957) ...................................................................... . 11a

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 ............................. 24

Ex parte Pennell, 261 Ala. 246, 73 So. 2d 558 (1954)....11, 27

Friedbauer v. State, 51 Wash. 2d 92, 316 P. 2d 117

(1957) 12a

I l l

Garett v. State, 248 Ala. 612, 29 So. 2d 8 (1947) .......... 30

Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60 ................. .......22, 25

State ex rel. Grecco v. Allen Circuit Court, 238 Ind.

571, 153 N. E, 2d 914, 916 (1958) ............................ 12a

Hawkins v. State, 247 Ala. 576, 25 So. 2d 441 (1946) .... 33

Hill v. State, 310 S. W. 2d 588 (Tex. Cr. 1958) ........... 12a

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42 .............. ........... ............20, 29

Jackson v. State, 102 Ala. 167,15 So. 344 (1893) ........... 33

Johns v. Smyth, 176 F. Supp. 949 (E. D. Ya. 1959) .... 32

Johnson v. State, 79 Okla. Crim. 363, 155 P. 2d 259

(1945) ........................................................................ 11a

Johnson v. Williams, 244 Ala. 391,13 So. 2d 683 (1943) 27

McNeal v. Culver, 365 U. S. 109 .................. ............. 34

Moore v. Michigan, 355 U. S. 155............... ................ 20

Morrell v. State, 136 Ala. 44, 34 So. 208 (1903) .......... 30

Palmer v. Ash, 342 U. S. 134....... ....... ................... 20

Parker v. Ellis, 362 U. S. 574 ................ 33

Patton v. United States, 281 U. S. 276 ....... . 25

People v. Dolac, 160 N. Y. S. 2d 911 (1957)..... 21

People v. Havel, 134 Cal. App. 2d 213, 285 P. 2d 317

(1955) .................. ................. .................................. 11a

People v. Matera, 132 N. Y. S. 2d 117 (1954) ............. 21

People v. Moore, 405 111. 220, 89 N. E. 2d 731 (1950) .... 21

People v. Williams, 225 Mich. 133, 195 N. W. 695

(1923) ........................................................................ 13a

Poindexter v. State, 183 Tenn. 193, 191 S. W. 2d 445

(1946) ................................................................. ...... 13a

Ex Parte William Powell, Civil Action No. 1563-N,

March 4,1960, reversed 287 F. 2d 275 (5th Cir. 1961) 9

Powell v. Alabama, 387 U. S. 45 .......15,19, 20, 21, 22, 32

PAGE

IV

Eeece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85 ..................................... 27

Reynolds v. Cochran, 365 U, S. 525 ........................... .23, 33

Roberts v. State, 219 Md. 485, 150 A. 2d 448 (1959) 14a

Rohn v. State, 186 Ala. 5, 65 So. 2d 42 (1914) ........... 30

Ex parte Seals,----- Ala.------, 126 So. 2d 474 (1961)..11, 26

Commonwealth ex rel. Shelter v. Burke, 367 Pa. 152,

79 A. 2d 654 (1951) _____ ______ _____ ___ ____ 14a

Simpson v. State, 81 Fla. 292, 87 So. 920 (1921) ........... 33

Smith v. State, 245 Ala. 161, 16 So. 2d 315 (1944) .. 26

Snyder v. Massachusetts, 291 IT. S. 97 ..................... 25

Spano v. New York, 360 U. S. 315............................19, 21

State v. Allen, 174 Mo. 689, 74 S. W. 839 (1903) ........... 11a

State v. Cartwright, 81 Ohio L. Abs. 226, 161 N. E. 2d

456 (1957) ................................... ........................ ..... 13a

State v. Dechman, 51 Wash. 2d 256, 317 P. 2d 527

(1957) ___________________________________ 12a

State v. Jameson, 77 S. D. 340, 91 N. W. 2d 743 (1958) 12a

State v. Poglianich, 43 Idaho 409, 252 Pac. 177, 181

(1927) ..... .................................................................. 11a

State v. Sullivan, 227 F. 2d 511 (10th Cir. 1955) ...... 21

State v. Swenson, 242 Minn. 570, 65 N. W. 2d 657

(1954) ........ ............. ...... ....... .................................... 21

In the Matter of the Application of Sullivan and

Braash, 126 F. Supp. 564 (I). Utah 1954) .......... 35

Swagger v. State, 227 Ark. 45, 296 S. W. 2d 204 (1956) 1.1a

Sweet v. Howard, 155 F. 2d 715 (7th Cir. 1946) .......... 22

Taylor v. Alabama, 249 Ala. 667, 32 So. 2d 659 (1947),

affirmed 335 U. S. 252 ................................................. 27

Tomkins v. Missouri, 323 U. S. 485 ............ ................ 20

Tumev v. Ohio, 273 U. S. 510 ......... .......................... 25

PAGE

V

United States v. California Co-Op. Canneries, 279

U. S. 553 ......................... .......................................11,27

United States v. Morgan, 346 U. S. 102..................... 26

United States v. Pink, 315 U. S. 203 .........................11, 27

United States v. Ragan, 166 F. 2d 976 (7th Cir. 1948) .. 22

Urie v. Thompson, 337 U. S. 163 ................................ 28

Uveges v. Pennsylvania, 335 U. S. 437 .....................19, 20

Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U. S. 708 ________ 20, 21, 28, 32

State ex rel. Welper v. Rigg, 254 Minn. 10, 93 N. W.

2d 198 (1957) ............................................................. 13a

Wicks v. State, 44 Ala. 398, 400 (1870)................... ..... 29

Wilcher v. Commonwealth, 297 Ky. 36, 178 S. W. 2d

949 (1944) .................... ............................................ 12a

Williams v. Kaiser, 323 U. S. 471 ............................ 20, 29

U nited States Constitutional and Statutory

P rovisions :

United States Constitution, Sixth Amendment .......... 13a

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment,

Sec. 1 ................... ............ ........... .... ............ ............ 3

28 U. S. C. Section 1257(3) ....................................... 2

S tate Constitutions:

Alaska Const., Art. 15, §1 ................................... Ha

Ga. Const., Art. 1, §5 ....... ............. ..................... 13a

Ind. Const., Art. 1, §13 ...... .... ......................... . 12a

Ky. Const., Art. 1, §11...... .................................... 12a

Tenn. Const., Art. I, §9 ........ ...... ............... ......... I3a

State Statutes and R ules :

Code of Alabama 1940, Tit. 14, §85 ................. ....4, 29

Code of Alabama, Tit. 14, §395 ............................ 29

PAGE

Code of Alabama, Tit. 15, §259, form 29 ...... . 29

Code of Alabama, Tit. 15, §259, form 89 .... 29

Code of Alabama 1940, Tit. 15, §279 ..... 30

Code of Alabama 1940, Tit. 15, §318 ..........3, 23,11a

Code of Alabama, Tit. 15, §423 ......................... 30

Alaska Code (1948), §66-10-3 ......... ........... ....... 11a

Arizona Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 39(b) 12a

Ark. Stat. Ann., §43-1203 .................................... 11a

Calif. Penal Code, §987 ................................ ....... 11a

Del. Code Ann., §5103 ........... .............................. 14a

Del. Superior Court Rules, Rule 44 ............. ........ 14a

Ga. Code Anno., §2-105...... ............ ..... ................. 13a

Ga. Code Ann., §27-3001 (A) ........... ............... . 13a

Idaho Code Ann., §§19-1512, 19-1513 ...... .......... 11a

111. Criminal Code, §730, 111. Rev. Stat., §101.26(a) 11a

111. Supreme Court Rules, Rule 26(2) .............. 11a

Iowa Code Ann., §775.4 ....................................... 11a

Gen. Stat. of Kansas (1959 Supp.), §62-1304 .... 11a

Md. Rules of Procedure, Criminal Causes, Rule

723(b) ....... ................... .................................... 14a

Mich. Stats. Ann., §28.1253, as amended, Public

Acts 1957, No. 256 ........................................... 13a

Minn. Stat. (1957), §611.07, as amended, Minn.

Laws 1959, c. 383 ........... ................................... 13a

Mo. Rev. Stat. 1949, §545.820 ......... ...................... 11a

Rev. Code of Montana, §94-6512 .......... .............. 11a

Nev. Rev. Stat., §174.120 ........ .......................... 11a

New Jersey Rev. Rules, §1:12-9 ........ ................ 12a

N. Y. Code of Criminal Procedure, §308 .......... 11a

N. D. Century Code, §29-01-27 ............................ 11a

N. D. Century Code, §29-13-03 ..... ........... ..... 11a

Ohio Rev. Code, §2941.50 ......................... ...... ....... 13a

vi

PAGE

22 Okla. Stat., §464 ................................................ 11a

Ore. Rev. Stat,, §135.320 ..........._............... ........... 11a

Purdons Pa. Stat., Tit. 19, §§783, 784 ............... . 14a,

S. D. Code, §34.1901 (1960) ...... ......................... 12a

S. D. Code, §34.3506 (1960) ................ ...............11 a -12a

Term. Code, §§40-2002, 40-2003 ........................... 13a

Vernon’s Texas Code of Criminal Procedure,

§§491, 494, as amended by Acts 1959, c. 484 .... 12a

Utah Code Anno., §77-22-12 _______ _________ 12a

Code of Va., §19.1-241 ......................................... . 12a

Rev. Code of Wash., §10.01.110 .............. ............ 12a

Rev. Code of Wash., §10.40.030 .............. ............ . 12a

W. Va, Rules of Practice for Trial Courts, Rule

IV(a) .......... 13a

Wis. Stat. Ann., §957.26(2) ___ ______ ___ __ 12a

Wyo. Stat., §7-7 ...................................... 13a

Other Authorities :

Ann. Cases 1913C, p. 517 ........................................... 33

Knapp, “Why Argue an Appeal? If So, How”, 14 The

Record 415 (November 1959) ...... .............. ........... 23

Op. Mich. Att. Gen., Oct. 7, 1957 ................................ 13a

Orefield, Criminal Procedure Prom Arrest to Appeal

425 ............................................................................. 28

Webster’s New International Dictionary (2d ed. un

abridged, 1953) ............................................ .......... 30

Y l l

PAGE

1st the

Bupumt fernt nf % Mnxtzb Butts

October Term, 1961

No. 32

Charles Clarence H amilton,

Petitioner,

State of Alabama,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF AT.ARATVTA

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama is re

ported at ----- A la.------ , 122 So. 2d 602 and appears at R.

27. A prior opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama in

this case is reported at 270 Ala. 184, 116 So. 2d 906 and

appears in Appendix A to Petitioner’s brief, infra p. la.

This Court’s denial of certiorari on a prior petition seeking

review of the judgment affirming the conviction is reported

at 363 U.S. 852.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama denying

leave to file a writ of error coram nobis was entered on Au

2

gust 15, 1960, B. 36. By order of Mr. Justice Black entered

on November 15, 1960, execution of the death sentence im

posed upon the petitioner has been stayed pending issu

ance of the mandate by this Court. The jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked pursuant to Title 28 Section 1257(3),

petitioner having asserted below and asserting here depri

vation of rights, privileges and immunities secured by the

Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

I

Whether, petitioner, sentenced to death for “burglary

with intent to ravish”, and not represented by court ap

pointed counsel at arraignment as required by Alabama

law, had to demonstrate disadvantage flowing from the

denial to secure reversal of the conviction under the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

II

Whether petitioner, an indigent, ignorant, unstable

Negro, completely untutored in the ways of the law,

charged with a capital sex crime against a white woman

in Alabama, in open conflict with his court appointed at

torney during trial which otherwise was marked by peti

tioner’s bungling efforts to defend himself at the Court’s

invitation, was deprived of due process secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment by lack of court appointed counsel

at arraignment, the appropriate time under Alabama law

to raise certain defenses, and the only time prior to trial

that the Court practicably could have made provision to

reconcile counsel and client or appoint another attorney.

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This ease involves the following constitutional and statu

tory provisions:

1. Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

2. Code of Alabama 1940, Tit. 15, §318, which provides:

When counsel appointed for defendant in capital

case.—When any person indicted for a capital offense

is without counsel and the trial judge, after due in

vestigation, is satisfied that the defendant is unable

to employ counsel, the court must appoint counsel for

him not exceeding two, who must be allowed access to

him, if confined, at all reasonable hours, and as com

pensation for said defense the attorney or attorneys

so appointed shall be entitled in each case to a fee

fixed by the judge presiding at said trial, which fee

shall be not less than fifty ($50.00) dollars, nor more

than one hundred ($100.00) dollars, to be paid on the

warrant of the state comptroller from the general

funds in the state treasury. Said presiding judge in

the case shall certify to the comptroller that “The at

torney or attorneys appointed by the Court in the case

of Alabama vs....... ........ (name of defendant) has (or

have) performed the service required of him (or them)

in representing the said defendant and that the fee

therefor has been fixed in the sum o f________ dollars

(designate amount of fee).” Whereupon a warrant

shall be drawn in favor of the attorney or attorneys

upon the general funds of the treasury of the state of

Alabama in payment therefor.

4

3. Code of Alabama 1940, Tit. 14, §85, which provides:

Burglary in the first degree. —Any person who, in

the nighttime, with intent to steal or to commit a felony,

breaks into and enters any inhabited dwelling house, or

any other house or building, which is occupied by any

person lodged therein is guilty of burglary in the first

degree, and shall on conviction be punished at the dis

cretion of the jury, by death or by imprisonment in

the penitentiary for not less than ten years.

Statement

This cause now is here for the second time and before re

counting the facts in detail, petitioner first briefly relates

the reason for successive applications. Petitioner was sen

tenced to death April 23, 1957 upon an indictment charg

ing burglary with intent to ravish.1 He appealed to the

Alabama Supreme Court, alleging, among other things, that

he had been denied due process of law secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment in that he did not have effective

representation of counsel at trial. See Hamilton v. State,

270 Ala. 184, 116 So. 2d 906 (1959), and see this peti

tioner’s Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Oct. Term 1959,

No. 1026 Misc. The Alabama Supreme Court affirmed,

Hamilton v. State, supra, whereupon petitioner brought

the cause here on certiorari (No. 1026 Misc. Oct. Term 1959)

making the same constitutional allegations. One of peti

tioner’s particular allegations here was that he did not

have any counsel at all at arraignment, concerning which

the Alabama Supreme Court had held on his appeal that

“the right of accused to assistance of counsel includes the

right to assistance from the time of arraignment until be

ginning and end of trial.” 270 Ala. 188, 116 So. 2d 909

1 The same indictment also charged burglary with intent to steal

but petitioner was not found guilty of this count (R. 7).

5

(1959). Moreover, the Alabama Coart acknowledged that

this right was secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution as well as the laws of the State

of Alabama. But it held that “the principle is without ap

plication to the record before us,” reading the record as

demonstrating that petitioner indeed was represented by

counsel at arraignment. Petitioner’s effort to demonstrate

that this was not so by reference to other portions of the

record was rejected because state law precluded impeach

ing minute entries. 270 Ala. 188, 116 So. 2d 909 (1959).

The October, 1959 Term Petition for Writ of Certiorari

had urged this Court to find as a constitutional fact that

petitioner did not have counsel at arraignment, that this

denial deprived him of due process of law, and that the

conduct of the trial, in view of the representation by court

appointed counsel, among other things, fell below Four

teenth Amendment due process requirements.* 1 2 But Ala

bama argued in opposition that

2 The questions presented in the first petition were:

1. Whether indigent Negro petitioner, unable to employ counsel,

having been indicted for a capital offense regarded with especial

horror in this community (i.e., nighttime burglary with intent to

steal and with intent to ravish a white woman) and having been

incarcerated for approximately five months prior to arraignment,

was deprived of due process of law as secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, by being

arraigned and required to plead to said capital indictment without

benefit of the advice, guidance, assistance, or presence of counsel

in his behalf.

2. Whether petitioner was denied the fundamentals of a fair

trial including effective assistance of counsel, contrary to the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, by the trial of a

capital case involving difficult legal and factual issues, in which

conviction entirely depended upon inferences from circumstantial

evidence that petitioner acted with a specific criminal intent, and

in which punishment was determined in the discretion of the jury,

where:

a. The attorney appointed to defend petitioner sought to with

draw from the ease immediately before trial, and petitioner indi

6

“[t]he burden is not on the State of Alabama to ex

plain the fancied inconsistency as to why the minute

entry of record shows that the defendant did have

counsel at his arraignment and yet his trial counsel

was apparently appointed three days later. Actually,

the counsel in this particular case was appointed quite

sometime prior to the official judgment entry to defend

the petitioner on a previous indictment and remained

assigned as counsel to the defendant throughout and

including the day of arraignment on the second indict

ment. The two entries of judgment are not in conflict

and the statement by the petitioner that the defendant

was deprived of counsel at the time of his arraign

ment is pure conjecture on the part of the petitioner’s

counsel.”

Respondent pointed out that

“The petitioner, however, still has available to him

another remedy to attack the validity of the judg

ment entry in this case with extrinsic matter. That

method is the writ of error coram nobis. See, for

example, Taylor v. Alabama, 249 Ala. 667, 32 So. 2d

659, affirmed 335 U. S. 252. But the petitioner may

not attack the validity of a judgment entry on appeal.”

cated to the court his dissatisfaction with the appointed attorney,

all in the presence of the venire, and the trial judge denied the

attorney’s request to withdraw, without inquiring of him or peti

tioner concerning the reasons for or nature of their apparent

incompatibility, but instead proceeded to trial.

b. The trial judge, under these circumstances, encouraged and

permitted petitioner to attempt to supplement the appointed attor

ney’s presentation, even though petitioner at the outset and there

after plainly demonstrated that he was not versed in law or tutored

in courtroom decorum, thereby necessitating repeated reprimands

of defendant and lectures by the court in the presence of the jury,

prior to and throughout the trial as petitioner clumsily endeavored

to examine witnesses and argue points of law.

7

Brief in Opposition, pp. 5, 6. Certiorari was denied by

this Court.

Petitioner now has pursued the suggested course via

coram nobis and has amplified the record to demonstrate

that in fact he did not have counsel at arraignment. But

on this application, the Supreme Court of Alabama while

reaffirming his right to counsel at arraignment again has

rejected his plea:

“Hamilton should have been represented by counsel

at the time of his arraignment. We construe the peti

tion and the papers filed in support and in opposi

tion thereof to show, as we have indicated above,

that he was not so represented.”

Nevertheless, because “ [tjhere [was] no showing or effort

to show that Hamilton was disadvantaged in any way by

the absence of counsel when he interposed his plea of

not guilty,” B. 35, the court rejected his petition.

Petitioner now returns to this Court on petition for writ

of certiorari, granted on January 9, 1961. The Petition for

Writ of Error Coram Nobis (R. 1), denial of which occa

sions the instant Petition alleged:

Petitioner first had been indicted November 9, 1956 for

burglary in the night time with intent to steal. He was

arraigned January 4, 1957, at which time counsel, Mr. Clell

I. Mayfield, was appointed and entered a plea of not guilty.

Trial was set for January 14, 1957, but was passed four

times until April 24, 1957 when the case was nolle prossed

on recommendation of the solicitor.

February 12, 1957, the grand jury indicted petitioner

for burglary “with intent to ravish” and for burglary with

intent to steal. March 1, 1957 petitioner was arraigned

in this cause—the one now before this Court. He pleaded

not guilty. At this time no counsel had been appointed

to defend on this indictment and no counsel was present.

The affidavit of Mr. Mayfield, subsequently appointed to de

fend petitioner, appended to the petition for Writ of Error

Coram Nobis, states:

That said attorney states to the best of his knowl

edge, information and belief that he was not present

at the arraignment of said Charles Clarence Hamilton

on March 1, 1957. Said attorney further states that

he did not advise or consult with said defendant at

the arraignment of March 1, 1957 (R. 4).

March 4, 1957 Mr. Mayfield who was the court appointed

attorney on the prior indictment (burglary with intent to

steal) was appointed to defend petitioner on the two-count

indictment of February 12, 1957.

The Petition for Writ of Error Coram Nobis then stated

that on appeal the Court had held that the minute entry,

which recited that petitioner had counsel at arraignment,

could not be impeached by the Judge’s bench notes. Here,

however, the minute entry had been categorically disproved

by counsel’s affidavit. In view of the fact that the Court

had agreed that petitioner possessed state law and Four

teenth Amendment rights to counsel at arraignment, the

petition prayed for an order permitting filing of the Writ

of Error Coram Nobis.

In opposition to the petition for Writ of Error Coram

Nobis, the State alleged that the petition “lackfed] a proba

bility of truth,” that petitioner was represented by coun

sel at the time of his arraignment on March 1, 1957, and

that:

3. Non-representation of counsel at the time of arraign

ment is not per se a denial of due process. The peti

tioner must make some showing or allegation of in

9

jury or prejudice to this cause. [See Exhibit C at

tached hereto and made a part hereof.]3

4. The petitioner has alleged no showing of prejudice

and such affirmatively appears of record (E. 12).

An affidavit by Mr. Mayfield submitted by the State as

serted that he had been appointed to represent Hamilton

on the prior indictment (for burglary with intent to steal)

later nolle prossed; that his appointment on the indictment

charging burglary with intent to ravish and burglary with

intent to steal was not made until three days after it was

handed down; that he “knew of the second indictment prior

to its being returned by the Grand Jury”, was “aware of”

the second indictment and arraignment; “considered him

self” as representing defendant, and that the arraignment

“was done with his consent although he was not present.”

Furthermore, “he would not have entered any different

plea.” He considered “the arraignment a mere formality

since the same plea woiild be entered that had been entered

on the first arraignment to the first indictment which oc

curred on the 4th day of January, 1957, and that was his

reason for not attending the second arraignment” (E. 13).

The Deputy Circuit Solicitor who prosecuted the case

deposed (E. 14) that he spoke with Mr. Mayfield informing

him that a new indictment wTas being procured and later

told him that the new two count indictment had been re

turned and that defendant would be rearraigned. None

of the affidavits indicates whether Mr. Mayfield saw this

indictment. The prosecutor gave as reason for the appoint

3 This exhibit is the opinion of the United States District Court

for the District of Alabama, Northern Division, in Ex Parte Wil

liam Powell, Civil Action No. 1563-N March 4, 1960, in which the

petitioner in that case raised the issue of right to counsel. That

ease now has been reversed on the ground of state suppression of

evidence. 287 F. 2d 275 (5th Cir. 1961).

10

ment of March 4, that it was necessary to assure that the

lawyer would receive a fee for the second case:

. . . realizing further that the record would have to

show in order for Mr. Mayfield to receive his fee from

the State of Alabama for representing the defendant,

Mr. Deason requested Judge King to let the record

reflect the fact that Mr. Mayfield had been formally

appointed in the second case so there would be no

question about his receiving his fee for representing

the defendant and this occurred on March 4,1957 (B. 5).

The Supreme Court of Alabama, held that petitioner

had followed the proper procedure (B. 27), but denied the

petition for leave to file an application for writ of error

coram nobis. It found that Hamilton was not represented

by counsel at the time of the second arraignment:

We hold that it is made to appear in this proceeding

that Hamilton was not represented by counsel at the

time he was arraigned on the indictment on which he

was subsequently tried and convicted. We are not

here controlled by the minute and judgment entries, as

was the situation on appeal from the judgment of con

viction—Hamilton v. State (Ala.), 116 So. 2d 906

(B. 28-29).

Alabama law “places upon the trial court the responsi

bility of seeing that an accused indicted for a capital offense

has a lawyer before he is arraigned and called upon to

plead to the indictment” (B. 29). Moreover,

Hamilton should have been represented by counsel

at the time of his arraignment. We construe the peti

tion and the papers filed in support and in opposition

thereof to show, as we have indicated above, that he

was not so represented (B. 29).

11

But, the petition for leave to file application for Writ of

Error Coram Nobis was denied on the ground that Hamilton

did not show that he had been prejudiced by this lack of

representation (R. 30). The Court concluded:

We are, of course, not unmindful of the severity

of the punishment in this case, but we cannot say that

a prima facie case for the filing of a petition for writ

of error coram nobis has been made. We must, there

fore, deny the petition (R. 35).

The record now brought here on certiorari from denial

of leave to file an application for Writ of Error Coram

Nobis amplifies the record brought here earlier which

this Court may judicially notice, United States v. Pink, 315

U. S. 203, 216; United States v. California Co-Op Canneries,

279 U. S. 553, 555; Bienville Water Supply Co. v. City of

Mobile, 186 U. S. 212, 217, as might the Supreme Court of

Alabama, Ex parte Seals, ----- Ala. ----- , 126 So. 2d 474

(1961); Ex parte Fewell, 261 Ala. 246, 73 So. 2d 558 (1954);

Ex parte Burns, 247 Ala. 98, 22 So. 2d 517 (1945).

At the first trial the evidence indicated that on the night

of October 12, 1956 (R.# 55, 77)4 and on the morning of

October 13, 1956 (R.# 21, 39) in Ensley, Alabama, peti

tioner,5 a Negro, was found in the bedroom of Mrs. Mary

4 R# refers to the Record filed with the petition for writ of cer

tiorari, No. 1026 Misc., October Term, 1959.

5 According to a report of the State Board of Pardons and

Paroles, petitioner left school after reaching the eleventh grade

in 1950. Following a dishonorable discharge in 1956 he did only

casual or part time work. The State Board report concluded that

he and his family were indigent (R.® 8). Affidavits of his mother

and cousin urge that the petitioner was mentally ill (R.# 9, 10) and

that court appointed counsel had been told that the family believed

petitioner was not sane (R.# 11). Counsel believed, however, that

petitioner was sane, although, following trial, the affidavit relates,

counsel concluded that petitioner had demonstrated that he was not

sane (R.# 11).

12

Giangrosso (R.# 26, 56, 71) by her granddaughter’s hus

band (R.# 26). The grandmother was elderly, ill, almost

blind, and spoke indistinctly with a broken accent (R.* 24).

Petitioner testified he could not understand her (R.* 67,

70). His testimony, in fact, was incoherent, but was gen

erally, that he thought she had summoned him to the room

(R.# 56), possibly because someone had robbed her (R.*

57). The grandchildren called the police (R.* 27). There

was some testimony concerning the condition of the lock,

although it was not demonstrated that it had been broken

(R.* 42). While the windows and doors had been secured

prior to retiring, the door from the porch to the grand

mother’s bedroom was open (R.# 37).

There was testimony that petitioner was indecently ex

posed (R.* 35), but Mrs. Giangrosso (the alleged intended

victim of rape) did not testify, although counsel for peti

tioner (the same man who had been appointed on March

4, and had not attended the arraignment) called for her

testimony during the trial; since she had not been sub

poenaed, she did not testify and he made no effort to secure

her attendance (R.# 42, 43).

There was no evidence that any rape, violence, or physical

injury of any kind occurred to Mrs. Giangrosso or anyone

else, nor evidence that petitioner had any weapons, bur

glary tools, or the like.

The trial was brief. Taking of testimony commenced at

11:00 and the trial terminated at 4 :10 P.M., with an hour

and forty minutes recess for lunch (R.# 19, 54, 85).

The trial was marked by constant clashes between peti

tioner and his court-appointed counsel and between peti

tioner and the court, with petitioner challenging the right

of the court to try him on the second indictment and in

sisting that he did not want the court-appointed counsel

13

to represent him. As the trial commenced, the Court ad

monished petitioner: “Let me say this to you: You are

represented by counsel. You are not going to disturb this

court. I have tried to be courteous to you and explain the

law to you, but you are not going to wrangle. You just be

quiet.” Thereupon, petitioner disavowed his counsel:

The Defendant: Before you go on, let me say this:

This lawyer is not my lawyer. He was appointed by

the Court.

The Court: The law provides the Court appoint you

counsel. You were appointed the lawyer so that you

may get your constitutional rights (R.* 16).

At this point at the beginning of trial the court-appointed

attorney requested permission to withdraw; this was de

nied (R.* 16)—all in the presence of the jury.

Apart from court-appointed counsel petitioner had no

other lawyer. The Court provided that petitioner might

conduct examinations of witnesses himself after counsel

completed examination (R.* 18).

Petitioner’s first effort at cross-examination came at the

Court’s renewed invitation: “Hamilton, due to the fact you

stated you did not employ Mr. Mayfield as your attorney,

I told you that, after examination by the state and Mr. May-

field, if you thought of any additional questions you wanted

to ask, I would allow it. Can you think of any additional

questions to ask this lady?” (R.* 31). Petitioner, appar

ently addressing himself to the charge of intent to steal,

asked, in part “would they say I intended to steal, with my

clothes off” (R.* 32). There was an objection to which the

Court stated “You may not argue or harass the witness.”

The Court then inquired “do you have any further ques

tions?” Petitioner replied “No, sir” (R.# 32).

14

Following testimony of another prosecution witness, the

Court addressed petitioner, “Now, Hamilton, do you think

of any additional questions, in view of what was stated

before, that should be asked this gentleman?” (R.* 37).

Petitioner replied “There is nothing I could ask, you would

allow.” The Court stated “In other words, you just want to

ask him why the Grand Jury did so and so?” Petitioner

stated “There is nothing I could, that wouldn’t show re

flection on him.” The Court replied “You ask it.” Peti

tioner stated: “There is one of them, right there (indicat

ing).” The Court then stated “I told you you can’t ask

him about the Grand Jury doing* something. If you have

other questions, you may ask them” (R.* 37-38). Petitioner

stated, “No questions, sir” (R.# 38).

Similar colloquies between the court and petitioner oc

curred following testimony of Police Officer Cope (R.* 40)

and Police Officer Boyd (R.* 42).

Court-appointed counsel after inquiring whether Mrs.

Giangrosso was in court, calling her and, upon no re

sponse abandoning the thought of having her testify, called

the witness, Marisette (R.# 43). He described having spent

time with petitioner on the evening of the alleged offense

until sometime between 10 :Q0 and midnight. The state cross-

examined, and then the Court stated to petitioner, “Hamil

ton, when these witnesses are put up here on your behalf,

if you want to ask them anything, you may do so.”

The Defendant: The defendant will make his own

testimony.

The Court: Do you want to ask this last witness

anything?

The Defendant: No, sir (R.# 48).

The trial concluded with a lengthy charge to the jury

which nowhere defined “intent to ravish”, and to which no

15

objections were taken. Petitioner himself argued to the

jury, but said he did not understand the charge. The ver

dict was guilty and petitioner was sentenced to death.

Summary of Argument

Petitioner was denied due process of law secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment because he was not represented

by counsel at arraignment on a capital charge; i.e., burglary

with intent to ravish. This Court has without qualification

held that in a capital case the accused requires the guiding

hand of counsel at every step in the proceeding against him.

Alabama itself has held that this much is required by its

own law and by the Fourteenth Amendment. The refusal

to issue the writ of error coram nobis on the alleged ground

that petitioner did not demonstrate “disadvantage” would

introduce a corrosive influence into the settled rule which

has been the view of this Court since Powell v. Alabama.

The appointment and physical presence of a lawyer at

arraignment and other judicial proceedings in a capital

case is the minimum objective procedural protection due

to a defendant which the courts can enforce.

But, even if, arguendo, disadvantage need be shown it

has been demonstrated fully. It is prejudicial per se not

to have counsel at arraignment in a capital case involving

difficult and subtle legal questions of, among other things,

criminal intent, which turn on inferences from circumstan

tial evidence. Arraignment was the only point at which

petitioner had an absolute right to raise such defenses as

jury discrimination and insanity and an appropriate time

perhaps to negotiate a plea to a lesser charge if that were

to be deemed advisable. Beyond this, the trial was marked

by clashes between petitioner and his court appointed

counsel, neither of whom wanted this lawyer-client rela

16

tionship and so expressed themselves before the jury. Peti

tioner was chastised by the court before the jury and at

the court’s invitation repeatedly made bungling efforts to

examine witness and argue points of law. Obvious ques

tions concerning the sufficiency and the indictment of the

charge were not raised. A crucial witness, the possible

subject of the intent to ravish, was not subpoenaed by de

fense counsel, who merely called for her in the courtroom

and when she did not appear abandoned the thought of

having her testify.

But even more fundamental, the theory by which respon

dent and the Court below expiate the failure to provide

court-appointed counsel at arraignment is that any failures

which might have occurred then because of the absence of

counsel were curable by subsequent representation at the

trial. This justification simply does not apply where the

trial, considered as a whole, including representation af

forded at it, was so grossly damaging and unfair to what

ever rights petitioner might have protected even at the trial

itself. Also, earlier exposure of petitioner to counsel in

the presence of the Court at arraignment well might have

led to their reconciliation or the appointment of new coun

sel prior to the trial in chief.

17

ARGUMENT

I.

The right of counsel during all stages of criminal pro

ceedings where the death penalty may be imposed is so

fundamental that it should not be limited at any point

by a rule requiring demonstration of the amount of

prejudice resulting from denial of representation at a

particular stage.

Petitioner, an indigent, not represented by counsel when

arraigned on a capital indictment, was tried, convicted,

and sentenced to death by electrocution. Lack of repre

sentation at arraignment violated Alabama law and the “al

most uniform” practice in the Alabama circuit courts. The

court below a t -----Ala. — —, 122 So. 2d 602, 603-4 held:

We hold that it is made to appear in this proceeding

that Hamilton was not represented by counsel at the

time he was arraigned on the indictment on which he

was subsequently tried and convicted. We are not here

controlled by the minute and judgment entries, as was

the situation on appeal from the judgment of convic

tion.—Hamilton v. State, Ala., 116 So. 2d 906.

Section 318, Title 15, Code 1940, as amended, pro

vides in pertinent parts as follows: “When any per

son indicted for a capital offense is without counsel and

the trial judge, after due investigation, is satisfied

that the defendant is unable to employ counsel, the

court must appoint counsel for him not exceeding two,

who must be allowed access to Mm, if confined, at all

reasonable hours, . . . ” We think this section places

upon the trial court the responsibility of seeing that an

accused indicted for a capital offense has a lawyer be

fore he is arraigned and called upon to plead to the in

18

diriment. We have found no Alabama case expressly

so holding, but this has been the almost uniform prac

tice of the circuit courts of this state for many years

and the very purpose of the statute seems to dictate

such action.

* =* # # #

Hamilton should have been represented by counsel

at the time of his arraignment. We construe the peti

tion and the papers filed in support and in opposition

thereof to show, as we have indicated above, that he

was not so represented. (Emphasis supplied.)

Notwithstanding this holding and that he had no coun

sel, his petition for a coram nobis hearing was rejected

on the ground that Hamilton was not “disadvantaged” :

There is no showing or effort to show that Hamilton

was disadvantaged in any way by the absence of coun

sel when he interposed his plea of not guilty. Counsel

was appointed for him three days after arraignment

whose competence is not questioned and who asserts

in an affidavit filed in this proceeding that “he would

not have entered any different plea than the plea that

was entered by the defendant on March 1,1957.” There

is no suggestion that the not guilty plea interposed

at the arraignment in absence of counsel prevented

the filing of any other plea or motion. (122 So. 2d 602,

607).

The Court explained away its earlier opinion on appeal

which had seemed to agree without qualification that denial

of counsel at arraignment denies rights protected by federal

and state law.6 Instead it required petitioner to show how

6 In the earlier opinion the Supreme Court of Alabama had said

at 270 Ala. 184, 188, 116 So. 2d 906, 909:

Appellant insists that in capital cases where defendant is

unable to employ counsel the court must appoint effective coun

19

he was harmed by denial of counsel, thus qualifying the

right to counsel in a capital case.

While some procedural protections (including the right

to counsel in non-capital cases) have indeed been qualified

by considerations of this kind, cf. Betts v. Brady, 316 U. S.

455, heretofore the right to counsel at all stages of capital

cases has been regarded as absolute. In a capital case the

accused “requires the guiding hand of counsel at every

step in the proceeding against him” and the need for coun

sel is so “vital and imperative” that failure to afford counsel

offends due process. Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45. Only

“when a crime subject to capital punishment is not in

volved,” some Justices have held, does “each case depend

on its own facts.” Uveges v. Pennsylvania, 335 U. S. 437,

441. This view was only recently once more expounded by

Mr. Justice Stewart in Spano v. New York, 360 U. S. 315,

327:

sel for him, and failure to do so denied defendant a fair trial

and violates the equal protection and due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States and the Constitution and laws of the State of Alabama;

and the right of accused to assistance of counsel includes the

right to assistance from time of arraignment until beginning

and end of the trial.

We have no quarrel with the above insistence of counsel for

appellant, but the principle is without application to the record

before us.

In the opinion denying the coram nobis petition the Court said at

122 So. 2d 602, 607:

In the opinion written on the appeal from the judgment of

conviction (Hamilton v. State (Ala,), 116 So. 2d 906) we did

not intend to convey the impression that we entertained the

view that absence of counsel at the time of arraignment in and

of itself would vitiate the judgment of conviction. We simply

did not take issue with the assertions made by counsel for

Hamilton in that regard because the minute and judgments

entries showed that Hamilton was represented by counsel at

arraignment.

20

Under our system of justice an indictment is sup

posed to be followed by an arraignment and a trial.

At every stage in those proceedings the accused has

an absolute right to a lawyer’s help if the case is one

in which a death penalty may be imposed. Powell v.

Alabama [supra]. (Emphasis supplied.)

This Court frequently has considered the principles

governing the Fourteenth Amendment protection of the

right to counsel7 and has made basic distinctions between

capital and non-capital eases. While non-capital cases have

turned on the particular facts of each case and special cir

cumstances regarding disadvantage to the uncounselled

defendant, this rule has not been applied in capital cases.

See, Betts v. Brady, supra: Bute v. Illinois, 333 U. S. 640,

676; Uveges v. Pennsylvania, 335 U. S. 437, 441; Palmer v.

Ashe, 342 U. S. 134, 135; Tomkins v. Missouri, 323 U. S.

485, 487.

The importance of representation during all stages of a

capital prosecution is manifest, Powell v. Alabama, supra;

Moore v. Michigan, supra; the “guiding hand of counsel”

should be offered before an accused is required to plead to

an indictment. Williams v. Kaiser, 323 U. S. 471, 475; House

v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42, 45-46; and “arraignment is too im

portant a step in a criminal proceeding to give . . . wholly

inadequate representation,” Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U. S.

708, 723.

The court below cited several decisions in support of its

conclusion. Some must be distinguished because they in

volved only non-capital offenses, see, e.g., Canisio v. New

York, 327 U. S. 82.8 Moreover, unlike Canisio, supra, de

7 Many of the cases are collected in Moore v. Michigan, 355 U. S.

155,159, n. 7, and Cash v. Culver, 358 U. S. 633, 636, n. 6.

21

nial of counsel here violated Alabama’s own state law.8 9

The other state and lower federal precedents cited below,

see, e.g., People v. Moore, 405 111. 220, 89 N. E. 2d 731

(1950); People v. Matera, 132 N. Y. S. 2d 117 (1954),

Council v. Clemmer, 177 F. 2d 22 (D. C. Cir. 1949), to the

extent they seem to support the court’s view, are at variance

with the rulings of this Court and, if recognized, would

introduce a corrosive influence into the settled, salutary

rule which has been the view of this Court since Powell.

The holding below extends the Betts v. Brady, supra

limitations on right to counsel to the capital area. Without

mentioning that non-capital case, the court below applied its

theory, making the right in this capital case depend on

analysis of the unfairness resulting from lack of counsel.

Similarly, without mentioning Crooker v. California, 357

U. S. 433, the court below applied to arraignment (following

indictment) Crooker’s view that the right to counsel prior to

indictment depends upon circumstances. In Spano v. New

York, 360 U. S. 315, one issue was whether Crooker should

govern following indictment; while the majority found it

unnecessary to reach this issue, several Justices concurred

in the view that deprivation of counsel after indictment

denied due process, thereby invalidating a confession and

conviction. See 360 U. S. at 324, 326.

Occasionally, but rarely, when an attorney is actually

present, a criminal defendant can demonstrate qualitative

unfairness of ineffective representation. Cf. Von Molke v.

8 A ls o People v. Dolac, 160 N. Y. S. 2d 911 (1957) (non-capital).

See State v. Swenson, 242 Minn. 570, 65 N. W. 2d 657 (1954) (law

yer actually present at arraignment) ; State v. Sullivan, 227 F. 2d

511 (10th Cir. 1955) (counsel denied prior to indictment), both

capital cases.

9 Apparently only the dissenting Justices regarded the procedure

as violating state law in Canizio, 327 U. S. 82, 89.

22

Gillies, 332 U. S. 708; Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S.

60, 69-70, and Powell v. Alabama, supra. But unless qual

itative ineffectiveness is so flagrant that the trial is a sham

efforts to demonstrate that an attorney did his job poorly

are futile. See, for example, United States v. Ragen, 166

F. 2d 976, 980 (7th Cir. 1948); Sweet v. Howard, 155 F. 2d

715, 717 (7th Cir. 1946) (illiteracy of counsel, if proven,

still insufficient to establish incompetency). Alabama’s rule

is equally strict, Arrington v. State, 253 Ala. 178, 43 So.

2d 644, 646 (1949). Precisely because to show qualitative

inadequacy of representation is so difficult as to be virtually

impossible, it is all the more important to require as a

minimum objectively determinable procedural protection,

that at least some attorney he appointed and present to

counsel defendant at every stage of criminal proceedings

which may culminate in the imposition of a death penalty.

The State seems to regard appointment of counsel on

the second indictment (which added the charge, with “in

tent to ravish,” upon which petitioner was convicted) as a

“mere formality.” The affidavit by the lawyer appointed

to defend Hamilton against a prior indictment and ap

pointed again after the arraignment in question, stated his

opinion that the arraignment was a “mere formality” (B,

13). The deputy solicitor stated that following arraign

ment he requested the fresh appointment only to assure

that the defense attorney would receive his fee from the

State (B, 14). But the fresh indictment obviously was not

a mere formality; it charged a wholly different and more

reprehensible crime.

Neither the retrospective opinion by defense counsel that

nothing different would have occurred if counsel had been

appointed before and been present at, arraignment, nor the

prosecutor’s explanation about his concern over his ad

23

versary’s fee,10 changes the fact that counsel and Court

did not follow Alabama law as interpreted by its courts

and the “almost uniform” practice, which required that the

Court see that “an accused indicted for a capital offense

has a lawyer before he is arraigned and called upon to

plead to the indictment” ----- Ala, ----- , 122 So. 2d 602,

603-4). In any event, what lawyer can say with assurance

what he would have done if he had been present in court

on an occasion as important as arraignment in a capital

case. In a capital case, when a lawyer’s diligence and de

votion may save his client’s life at any stage of the proceed

ings, no stage properly may be regarded as a “mere for

mality.” As the opinion of the Court held in Reynolds v.

Cochran, 365 U. S. 525, 532-533.

“ . . . even in the most routine-appearing proceedings

the assistance of able counsel may be of inestimable

value.” 11

But here no lawyer had been appointed at the time of ar

raignment and made responsible for exercising whole

hearted diligence and devotion. Hamilton did not have the

benefit of counsel prior to entry of the plea.

The appointment and physical presence of a lawyer at

arraignment and other judicial proceedings in a capital

case is the minimum procedural protection due to a defen

dant which the courts can enforce. The ruling below to

the contrary again demonstrates the wTay that “illegitimate

and unconstitutional practices get their first footing . . .

10 Under Ala. Code, Tit. 15, §318, supra, defense counsel is en

titled to a fee of $50 to $100, to be fixed by the court.

11 And see Knapp, “Why Argue an Appeal? If So, How,” 14 The

Record 415, 426 (November 1959) in which the author writes “And

don’t miss any opportunity for communication between you and the

Court. If there is a long calendar call, don’t send a junior to answer

it. Be there yourself.”

24

by silent approaches and slight deviations from legal modes

of procedure” in hard cases involving “the obnoxious thing

in its mildest and least repulsive form,” Boyd v. United

States, 116 U. S. 616, 635. If counsel may be dispensed

with at arraignment in a capital ease with the rationaliza

tion that nothing different would have occurred had he been

present, can counsel’s presence next be dispensed with dur

ing part of the trial on the ground that defendant was not

flagrantly over-reached in his absence, or during the charge

to the jury on the same theory!

The right to counsel in a capital case is but one of the

areas covered by Fourteenth Amendment due process in

which a rule placing on the defendant the burden of show

ing prejudice would lead to erosion of basic standards of

integrity in the administration of criminal justice. For

example, the right not to have Negroes systematically ex

cluded from a jury which tries a Negro defendant is never-

qualified by demanding that he demonstrate prejudice from

having been tried by the all-white jury. Indeed, where a

Negro defendant has been indicted by a grand jury con

stituted in a racially discriminatory manner, and later

convicted by a petit jury concerning which no such charge

is even made, the conviction will be reversed. Cassell v.

Texas, 339 U. S. 282; and see Justice Jackson’s dissenting

opinion at 298, 303. This Court continues to adhere to this

position. Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584. In cases of

forced confessions defendants need not show that but for

the coerced confession which was introduced into evidence,

they would have been acquitted. Blackburn v. Alabama,

361 U. S. 199. As this Court held in that case:

In cases involving involuntary confessions this Court

enforces the strongly felt attitude of our society that

important human values are sacrificed where an agency

of the government, in the course of securing a convic-

25

tion, wrings a confession out of an accused against

his will. 361 U. S. 206-207.

Similarly, this Court has held that an accused may not

be tried by a tribunal financially interested in the outcome,

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U. S. 510, 535, even though there was no

demonstration that the financial interest played a role

in the decision and the evidence clearly indicated guilt.

Chief Justice Taft wrote “No matter what the evidence

was against him, he had the right to have an impartial

jury.” And cf. Snyder v. Massachusetts, 291 IT. S. 97, 116;

Patton v. United States, 281 U. S. 276, 292.

The right to counsel at all stages of a case in which the

death penalty can be (and was) inflicted is the same kind

of bedrock right. The Court’s opinion in Glasser v. United

States, 315 U. S. 60, 76, while dealing with a different

aspect of the denial of counsel, is nonetheless apposite:

“The right to have the assistance of counsel is too funda

mental and absolute to allow courts to indulge in nice

calculations as to the amount of prejudice arising from

its denial.”

II.

Even if, arguendo, a showing of “disadvantage” is

required, such amply appears of record.

Petitioner’s claim that he has been denied effective as

sistance of counsel in this capital case in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment is sustained even under a view

which requires that there be some demonstration of dis

advantage. The claim was made in petitioner’s October

1959 Term petition that he was denied effective assistance

of counsel in that he did not have a lawyer at arraignment;

that he was denied such assistance in that his was a capital

26

case involving difficult legal and factual issues in which

conviction entirely depended upon inferences from circum

stantial evidence that petitioner acted with specific criminal

intent; and in which punishment was determined in the

discretion of the jury ; that court appointed counsel sought

to withdraw from the case immediately before trial; that

petitioner indicated to the court his dissatisfaction with the

appointed attorney, and the trial judge denied the request

to withdraw without inquiring concerning the reasons for

the incompatibility; that the trial judge encouraged peti

tioner to attempt to supplement his appointed lawyer’s pres

entation even though petitioner demonstrated that he was

unversed in law and courtroom decorum, necessitating re

peated reprimands in the presence of the jury; that peti

tioner clumsily endeavored to examine witnesses and argue

points of law.12

The coram nobis petition was filed following denial of

the first petition for writ of certiorari in an effort to eluci

date a factual aspect of the proceedings concerning which

the parties disagreed (although petitioner contended the

record was utterly clear), i.e. whether court appointed coun

sel appeared at arraignment on the two-count indictment

charging burglary with intent to steal and “ravish.” The

coram nobis aspect of the case was “a part of the proceed

ing in the case to which it refer [red] . . . ” Smith v. State,

245 Ala. 161, 16 So. 2d 315, 316 (1944), or, as this Court

has held is “a step in the criminal case, not like habeas

corpus where relief is sought in a separate case and record

. . . ” United States v. Morgan, 346 U. S. 102, 105, note 4.

Consonant with this view, Alabama repeatedly has noticed

the record on appeal when it has passed on coram nobis

applications. Ex parte Seals, —— Ala. ----- , 126 So. 2d

12 See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, October Term 1959, No.

1026, p. 1 (Questions Presented).

27

474 (1961); Ex parte Fennell, 261 Ala. 246, 73 So. 2d 558

(1954); Ex parte Burns, 247 Ala. 98, 22 So. 2d 517 (1945);

Johnson v. Williams, 244 Ala. 391, 13 So. 2d 683 (1943);

Ex parte Taylor, 249 Ala, 667, 32 So. 2d 659 (1947); af

firmed 335 U. S. 252. In the latter ease, this Court held:

“The Supreme Court of Alabama . . . read this peti

tion and these affidavits, as we must read them, in

close connection with the entire record already made

in the case” (at 264-265).

But apart from the customary Alabama practice of read

ing coram nobis petitions in light of the entire record, re

spondent itself invoked consideration of the record as a

whole and the question of prejudice by its answer to the

coram nobis petition :

“3. Non-representation of counsel at the time of

arraignment is not per se a denial of due process.

The petitioner must make some showing or allegation

of injury or prejudice to this case . . .

4. The petitioner has alleged no showing of preju

dice and such affirmatively appears of record” (R. 12).

(Emphasis supplied.)

This Court too, apart from the question of disadvantage

brought here on this second petition, may examine the ques

tion in the light of the full record filed in the October 1959

Term which may be noticed. United States v. Fink, 315

U. 8. 203, 216; United States v. California Co-Op Canneries,

279 U. S. 553, 555; Bienville Water Supply Co. v. City of

Motile, 186 U. S. 212, 217, as Alabama may have noticed

it. See cases cited supra.

As stated in Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85, 87:

“We have jurisdiction to consider all of the substantive

federal questions determined in the earlier stages of

the litigation. . . ”

See also TJrie v. Thompson, 337 U. S. 163.

On appeal the right to effective assistance of counsel

issue was treated and disposed of by the Supreme Court of

Alabama in sweeping terms:

Appellant insists that in capital eases where defen

dant is unable to employ counsel the court must appoint

effective counsel for him, and failure to do so denied

defendant a fair trial and violates the equal protec

tion and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and the

Constitution and laws of the State of Alabama; and

that right of accused to assistance of counsel includes

the right to assistance from time of arraignment until

beginning and end of the trial. 270 Ala. 188, 116 So.

2d 909.

While agreeing with petitioner in theory the decision was

adverse to him.

The question of prejudice, or disadvantage, now before

this Court for the second time, resolves conclusively on

three distinct levels, each demonstrating that the judgment

below should be reversed.

(1) Absence of counsel at arraignment must have been

by any reasonable appraisal of the nature of arraignment,

and the issues posed by this case, prejudicial in and of itself.

“The entering of a plea is one of the most critical stages in

the proceedings.” Orefield, Criminal Procedure From Ar

rest to Appeal 425. Indeed, arraignment is so crucial a

stage of criminal litigation that state law concerning ap

pointment of counsel generally provides that the right

attaches at or before arraignment. See Appendix B. As

stated in Von Malike v. Gillies, 332 U. S. 708, 723, “ar

raignment is too important a step in a criminal proceeding

29

to give such wholly inadequate representation to one

charged with crime.” See also, House v. Mayo, 324 U. S.

42, 45-46. Petitioner alone could hardly have been ex

pected to know that he might have, for example, negotiated,

in exchange for a plea of guilty to a lesser offense, a lighter-

sentence. See Williams v. Kaiser, 323 U. S. 471, 475-476.

The nature of the charge emphasized petitioner’s in

ability to cope with the situation he faced. The crucial issue

to be tried was the nature of petitioner’s intent, for intent

was the gravamen of the offense, cf. Wicks v. States, 44 Ala.

398, 400 (1870), and a serious issue of fact in this case.

TAced with an indictment charging burglary with intent to

“ravish”, petitioner could not assess the nature and weight

of the proof relevant to prove or rebut the alleged intent.

Indeed petitioner could hardly be expected to understand

even what was meant by “intent to ravish” or the elements

of the offense.13 Petitioner could not be presumed to know

13 The court’s charge, astoundingly, did not at all define ravish.

Any uncertainty is not merely a matter of speculation about

petitioner’s vocabulary. Considering the following, what does

“to ravish” mean even to a lawyer who examines the Alabama

criminal code?

(1) The burglary statute prohibits burglary “with intent to

steal: or “with intent to commit a felony” (Ala. Code Tit.

14, §85).

(2) The Code lists no felony called “to ravish” (Tit. 14, pas

sim) ; though it does forbid “rape” (Tit. 14, §395).

(3) Only in another Title of the Code does any verbal connec

tion between “rape” and “ravish” appear in the Form of

Indictment for Rape—Tit. 15, §259, form 89, which pro

vides: “A.B. forcibly ravished C.D., a woman, etc.” The

rape statute does not use the word “ravish”.

Query: (1) Does the indictment even charge an offense when

it charges intent “to ravish”, while the burglary statute (and

also the form for burglary indictments, Tit. 15, §259, form 29)

calls for intent to commit a “felony?”

(2) If the indictment really charges intent to commit the

felony of rape, is it sufficient, failing to mention the elements

of force, or even the name of the intended victim of rape (par

30

that he had any alternative to pleading “guilty” or “not

guilty.” He could not know that his absolute right to plead

“not guilty by reason of insanity” under Ala. Code Tit. 15,

§423, is lost if not entered at the time of arraignment.

Morrell v. State, 136 Ala. 44, 34 So. 208 (1903). While there

is a discretionary power to allow later entry of the plea this

discretion is “not revisable” on appeal and may be reversed

only for abuse of discretion. Bohn v. State, 186 Ala. 5, 65

So. 42 (1914); Garett v. State, 248 Ala. 612, 29 So. 2d 8

(1947). When petitioner’s lawyer was appointed after ar

raignment, petitioner had already lost an absolute right

under Alabama law and he retained merely a right to ap

peal to the discretion of the Court. Moreover, arraignment

is the time to present various defenses under Alabama law.

Code of Ala. 1940, Tit. 15, §279.

(2) But beyond this, the trial itself was riddled with ex

plosions caused by petitioner’s conflict with the court, his

awkward efforts to conduct his defense, petitioner’s clashes

with his counsel, counsel’s efforts to withdraw, the court’s

censure of petitioner. The conflict between defendant and

defense counsel was openly displayed to the venire of pros

pective jurymen before the trial commenced (R.* 15-16),

accompanied by the Court’s expression of regret (R,* 17)

in holding appointed counsel to his assigned task. This con

ticularly when the only aggrieved person named in the indict

ment is a man) 1

Moreover, the dictionary definition of “ravish” gives primacy

to the sense of abduction; rape is but a subsidiary meaning,

among several. Webster’s New International Dictionary (2d ed.

unabridged, 1953).

These queries are all obviously questions of state law never

raised in the trial court and not directly before this Court;

but this is not the point. The point is that, unaided, petitioner

could not even be presumed to know that indictments don’t

always properly state an offense. A lawyer would know to read

an indictment with this in mind prior to entry of a plea on the

merits.

31

flict was re-emphasized as the trial progressed, by the

court’s repeated restatement of its reason for allowing de

fendant to cross-examine witnesses (R.# 31, 37).

Defendant’s inept attempts to represent himself led the

trial into chaos and confusion from which defendant

emerged the loser, a victim of his own ignorance and be

wilderment, The perception and insight of the Court at the

outset (R.# 19) in warning defendant about his conduct

should have served as sufficient notice that defendant was

unlikely to be able to conduct a cross-examination, present

evidence, or argue the law according to the usages of the

law.

The Court never inquired as to the basis for, or nature of,

the dissension between defendant and appointed counsel—

although from the start it must have been plain that some

thing was amiss. Defendant’s ambiguous statement—“This

lawyer is not my lawyer.” (R.# 116)—might have concealed

beneath it either a real impediment and conflict or merely

a confused mind. A few questions might have cleared the

air. The defense attorney’s motion to withdraw from the

case was left similarly unexplained. It is reasonable to as

sume that Court appointed counsel knew the rule, enunci

ated by the court below, and familiar to the point of being

a cliche, that:

“In the first place, attorneys at law are officers of

the Court. An attorney assigned as counsel ought not

to ask to be excused for any light cause” (R.# 111).

He may have fully believed that he had more than a

“light cause” for seeking to withdraw in this capital case.

But the Court denied the motion summarily without dis

cussion or inquiry.

The request to withdraw comprised the first words

uttered by Mr. Mayfield in the record. Was this motion a

32

spur of the moment reaction to petitioner’s statement that

Mr. Mayfield was not his lawyer, or counsel’s planned first

move at the beginning of the case, the product of reflection

and lingering doubts? How long in advance of trial did

counsel decide that he would prefer not to try the case?

How did it affect his preparation? Was the reluctance the

product of an inhibiting conscientious belief in his client’s

guilt, cf. Johns v. Smyth, 176 F. Supp. 949 (E. D. Va. 1959),

a conflict of interest, or other serious impediment? We can

only speculate futilely. The jury, too, was left to speculate.

Such an arrangement inevitably resulted in a pro forma

representation of a kind condemned by the Fourteenth

Amendment. Powell v. Alabama, supra, and Von Moltke v.

Gillies, supra, emphasize respectively denial of real rep

resentation, where responsibility is divided and where coun

sel is reluctant.

The fact that the Court may have hoped to grant peti

tioner greater protection by permitting him to examine

witnesses and act as his own co-counsel, pales in the light of

the actuality that petitioner wTas given merely an implement

of further self-destruction. At the end of the trial the

Court asked if defendant had any objection to the charge,

and the answer (defendant’s last words, save two, before

the jury retired) obviously applies beyond the specific

question, to the entire proceeding:

“I didn’t understand it, sir” (R.# 92).

A reading of the trial record will confirm that the evi

dence contains more than a few mysteries as to what

actually transpired, and what petitioner actually intended

on October 13,1957. One thing is apparent: this is no stark

record of a ghastly crime; this is not the case of a ‘‘notorious

criminal” where “guilt permeates a record.” 14 This is a

14 Abel v. United States, 362 U. S. 217, 241 (dissenting opinion).

33

case where guilt depended upon a determination of what

was in the defendant’s mind, upon whether or not he had

the intent to commit all the elements of a substantive

felony, i.e., rape; and where decision must have been made

not on the basis of an inference from a finding of breaking

and entering (for this would not support a logical con

clusion that defendant had any particular felony in mind)

but rather from bits of facts, circumstances and inferences.

This Court does not sit to review the sufficiency of the evi

dence, or the adequacy of the court’s charge to the jury,15

but it must necessarily observe the overall record in as

sessing the prejudice to the petitioner which flowed from

the series of events claimed to have resulted in a denial of

effective assistance of counsel.16

The complex issues in the case called for the utmost

diligence on the part of counsel. In this respect the case

resembles Reynolds v. Cochran, 365 U. S. 525, 532-533, where

it also was argued that absence of counsel was “harmless.”

To this the Court replied:

We of course express no opinion as to how this

question of statutory construction should eventually

be decided by the Florida courts. But its mere exist

16 The court’s charge on “intent to ravish” is certainly unin

formative. For example what does “ravish” mean? Is it not

necessary to know the elements of the crime of rape to be able to

discover an intent to rape? Is not the intention to employ force

or coercion an essential element of the proof? These questions

should probably all be answered in the affirmative. See: Aiola v.

State, 39 Ala. App. 215, 96 So. 2d 816 (1957); Hawkins v. State, 25

So. 2d 441 (1946) ; Jackson v. State, 102 Ala. 167, 15 So. 344 (1893) ;

Compare: Simpson v. State, 81 Fla. 292, 87 So. 920 (1921) and note,

Ann. Cases 1913C, p. 517. But could the jury be presumed to know

these answers, or the petitioner be presumed capable of raising

them in his capacity as “co-counsel” for the defense.

16 Cf. Parker v. Ellis, 362 U. S. 574, 577, note 3 (dissenting opin

ion) (May 16, 1960).

34

ence dramatically illustrates that even in the most

routine-appearing proceedings the assistance of able

counsel may be of inestimable value. Plainly, such

assistance might have been of great value to petitioner

here.

And, in view of the record and issues which counsel

might have raised, much of what was said on the counsel