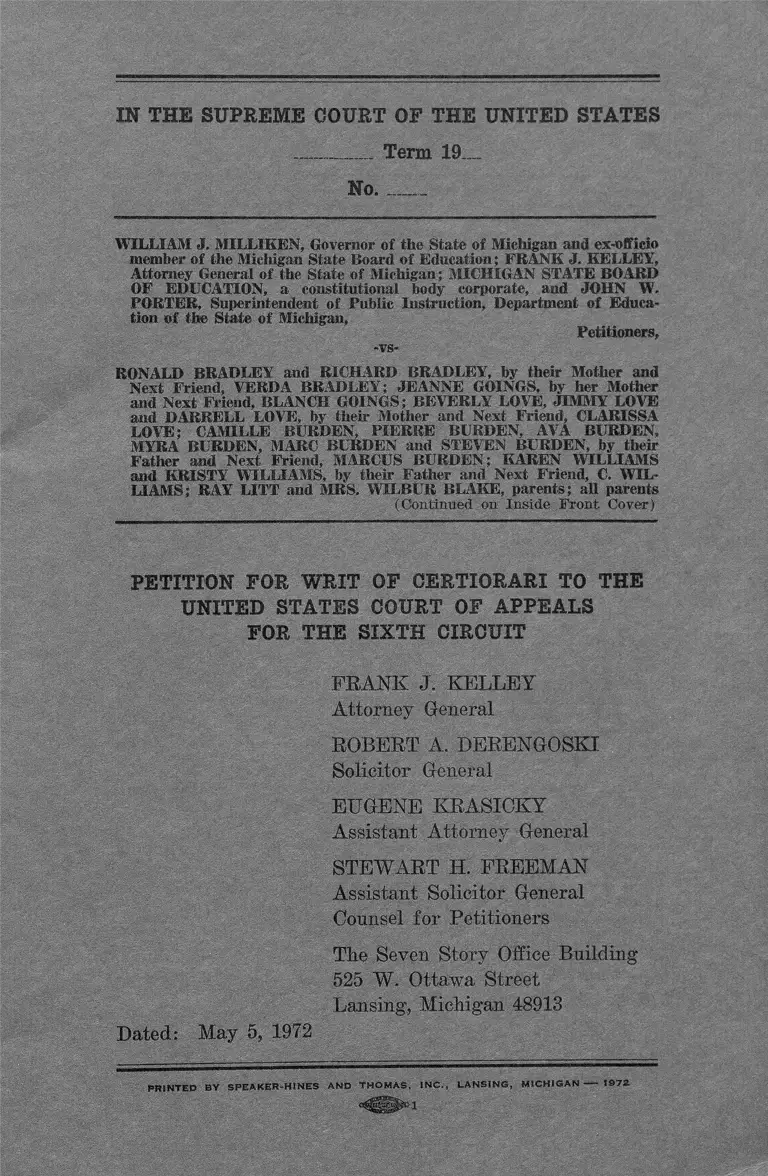

Milliken v. Bradley Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

May 5, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milliken v. Bradley Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1972. 580506c4-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/297ca43d-69df-4128-b78f-f99dfc38f550/milliken-v-bradley-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Term 19. .

No..........

WILLIAM J. MIL LIKEN, Governor of the State of Michigan and ex-officio

member of the Michigan State Board of Education; FRANK J. KELLEY.

Attorney General of the State of Michigan; MICHIGAN STATE BOARD

OF EDUCATION, a constitutional body corporate, and JOHN W.

PORTER, Superintendent of Public Instruction, Department of Educa

tion of the State of Michigan,

Petitioners,

-vs-

RONALD BRADLEY and RICHARD BRADLEY, by their Mother and

Next Friend, VERDA BRADLEY: JEANNE GOINGS, by her Mother

and Next Friend, BLANCH GOINGS; BEVERLY LOVE, JIMMY LOVE

and DARRELL LOVE, by their Mother and Next Friend, CLARISSA

LOVE; CAMILLE BURDEN, PIERRE BURDEN, AVA BURDEN,

MYRA BURDEN, MARC BURDEN and STEVEN BURDEN, by their

Father and Next Friend, MARCUS BURDEN; KAREN WILLIAMS

and KRISTY WILLIAMS, by their Father and Next Friend, C. WIL

LIAMS; RAY LITT and MRS. WILBUR BLAKE, parents; all parents

(Continued on Inside Front Cover)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

ROBERT A. DERENGOSKI

Solicitor General

EUGENE KRASICKY

Assistant Attorney General

STEWART H. FREEMAN

Assistant Solicitor General

Counsel for Petitioners

The Seven Story Office Building

525 W. Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Dated: May 5, 1972

P R IN T E D B V S P E A K E R -H IN E S A N D T H O M A S , IN C ., L A N S IN G , M IC H IG A N ----- 1 9 7 2

having children attending the public schools of the City of Detroit,

Michigan, on their own behalf and on behalf of their minor children,

all on behalf of any person similarly situated; and NATIONAL ASSO

CIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, DE

TROIT BRANCH; DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL

231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF 'TEACHERS, AFL-CIO; BOARD

OF EDUCATION OF THE CITS OF DETROIT, a school district of

the first class; PATRICK McDONALD, JAMES HATH A WAV and

CORNELIUS GOLIGIITLY, members of the Board of Education of

the City of Detroit; and NORMAN DRACHLER, Superintendent of

the Detroit Public Schools; ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITS OF BERKLEY, BRANDON

SCHOOLS, CENTERLINE PUBLIC SCHOOLS, CHERRY HILL

SCHOOL DISTRICT, CHIPPEWA VALLEY PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF CLAWSON, CRESTWOOD

SCHOOL DISTRICT, DEARBORN PUBLIC SCHOOLS, DEARBORN

HEIGHTS SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 7, EAST DETROIT PUB

LIC SCHOOLS, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF FEBNDALE.

FLAT ROCK COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, GARDEN CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, GIBRALTAR SCHOOL DISTRICT, SCHOOL DISTRICT

OF THE CITY OF HARPER WOODS, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE

CITY OF HAZEL PARK, INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL DISTRICT OF

THE COUNTY OF MACOMB, LAKE SHORE PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

LAKEVIEW PUBLIC SCHOOLS, THE LAMPHERE SCHOOLS, LIN

COLN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, MADISON DISTRICT PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, MELVIN’DALE-NORTH ALLEN PARK SCHOOL DIS

TRICT, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF NORTH DEARBORN HEIGHTS,

NOVI COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT, OAK PARK SCHOOL DIS

TRICT, OXFORD AREA COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, BEDFORD UNION

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, RICHMOND COMMUNITY SCHOOLS,

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF RIVER ROUGE, RIVER-

VIEW COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ROSEVILLE PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, SOUTH LAKE SCHOOLS, TAYLOR SCHOOL DISTRICT,

WARREN CONSOLIDATED SCHOOLS, WARREN WOODS PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, WAYNE-WESTLAND COMMUNITY SCHOOLS, WOOD-

HAVEN SCHOOL DISTRICT and WYANDOTTE PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

KERRY and COLLEEN GREEN, by their Father and Next Friend,

DONALD G. GREEN, JAMES, JACK and KATHLEEN ROSEMARY,

by their Mother and Next Friend, EVELYN G. ROSEMARY, TERRI

DORAN, by her Mother and Next Friend, BEVERLY DORAN, SHER

RILL, KEITH, JEFFREY and GREGORY COULS, by their Mother

and Next Friend, SHARON COULS, EDWARD and MICHAEL ROMES-

BURG, by their Father and Next Friend, EDWARD M. ROMESBURG,

JR., TRACEY and GREGORY ARLEDGE, by their Mother and Next

Friend, AILEEN ARLEDGE, SHERYL and RUSSELL PAUL, by their

Mother and Next Friend, MARY LOU PAUL, TRACY QUIGLEY, by

her Mother and Next Friend, JANICE QUIGLEY, IAN, STEPHANIE,

KARL and JAAKO SCNI, by their Mother and Next Friend, SHIRLEY

SUNI, and TRI-COUNTY CITIZENS FOR INTERVENTION IN FED

ERAL SCHOOL ACTION NO. 35257; DENISE MAGDOWSKI and

DAVID MAGDOWSKI, by their Mother and Next Friend, JOYCE

MAGDOWSKI; DAVID VIETTI by his Mother and Next Friend,

VIOLET VIETTI, and the CITIZENS COMMITTEE FOR BETTER

EDUCATION OF THE DETROIT METROPOLITAN AREA, a Mich

igan non-Proflt Corporation, SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY

OF ROYAL OAK, SOUTHFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOUS, GROSSE

POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

Respondents.

INDEX

Opinions and Orders B elow _________________________ 2

Jurisdiction To Review ____________________________ 3

Questions Presented ________________________________ 3, 4

Statutory Provisions Involved ______________________ 4

Statement of the C ase_______________________________ 5

Reasons For (Granting the Writ

I. The Order of November 5, 1971, Is A “ Final

Decision” Within The Meaning Of Title 28

U.S.C. §1291 _______ „_______________________ 9

II. The Findings of Fact, and Conclusions Of

Law, Which Underlie The Decision That A

Condition Of De Jure Segregation Exists In

The Detroit Public School System, Are Clear

ly And Patently Erroneous__________________ 12

III. A Metropolitan Plan Of Desegregation Is Con

stitutionally Inappropriate In The Complete

Absence Of A Finding Either That The Geo

graphically And Politically Independent Sub

urban Detroit School Districts Are Themselves

Guilty of De Jure Segregation Or, Alternative

ly, That The School District Boundary Lines

Were Created And Maintained With The In

tent Of Promoting A Dual School System ___ 18

Conclusion -------------------------- ------------------------- --------- 20

CITATIONS

Beech Grove Investment Company v. Civil Bights Com

mission, 380 Mich 405 (1968) _____________________ 13

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

—F Supp__, (ED Va, Jan. 5, 1972) _______________... 19

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 US 483

(1954) ______________________________________ 13

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 US 294 (1962) 11

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, 309 F

Supp 734 (ED Mich, 1970), a ff’d. 443 F2d 573 (CA

6, 1971) __________________________________________ 15

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education (Deal I), 369

F2d 55 (CA 6, 1966), cert den 389 US 847 (1967) .... 14

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education (Deal II), 419

F2d 1387, at 1392 (CA 6, 1969), cert den 402 US

962 (1971) _______________________________________ 15

Ferguson v. Gies, 82 Mich 358 (1890) _______________ 13

Gillespie v. United States Steel Corp., 379 US 148

(1964) ___________________________________________ 12

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County,

410 F2d 920 (CA 8, 1969) ________________________ 19

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 445

F2d 990 (1971), cert granted__U S __, 92 S Ct 707,

30 L Ed 2d 728 (1972) ___________________________ 17

People ex rel Workman v. Board of Education of De

troit, 18 Mich 399 (1869) ________________________ 13

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 US 1 (1971) _________________________________ 15

Title 28 U.S.C. §1291 ______________________________ 9

XI

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No_________

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

vs.

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Petitioners,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

The petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari be issued

to review the judgment and opinion of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit entered in this

proceeding on February 23, 1972. By such judgment,

the United States Court of Appeals declined to review

certain opinions and orders of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Michigan, Southern

Division, which decided that the School District of the

City of Detroit was a de jure segregated public school

system and directed the petitioners to prepare a “ Metro

politan” plan for the integration of the Detroit and sub-

urban-Detroit School Systems.

-2—

OPINIONS AND ORDERS BELOW

The opinion of the District Court, entitled “ Ruling on

Issue of Segregation,” was entered on September 27,

1971 and appears in the Appendix hereto, la to 27a.

The subsequent order of the District Court, dated No

vember 5, 1971, directing the submission of a “ metro

politan plan of desegregation” also appears in the Ap

pendix hereto, 29a to 30a. The District Court’s sub

sequent findings of fact and conclusions of law, based

upon the “ Ruling on Issue of Segregation,” which de

termined that “ relief of segregation in the public schools

of the City of Detroit cannot be accomplished within the

corporate geographical limits of the city,” also appears

in the Appendix hereto, 37a to 43a, as does the “ Rul

ing on Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy

to Accomplish Desegregation of the Public Schools of

the City of Detroit,” where the District Court found the

power and “ is required to consider a metropolitan remedy

for desegregation, ” appearing in the Appendix hereto,

31a to 36a.

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit filed February 23, 1972, dismissing

the appeal for want of a “ final” decision, appears in

the Appendix hereto, 44a to 45a.

Opinions of the United States Court of Appeals rendered

at prior stages of the present proceeding are reported in

433 F2d 897 and 438 F2d 945.

— 3—

JURISDICTION TO REVIEW

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit was entered on February 23, 1972.

This petition for certiorari was fded within 90 days of

that date.

The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked under Sec

tion 1291 of Title 28, United States Code.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I.

Where the United States District Court, after months

of hearing testimony and argument, issues a “ Ruling

on Issue of Segregation,” which makes extensive findings

of fact and conclusions of law and concludes that de jure

segregation exists in the Detroit Public School system, and

the District Judge thereafter enters an order, dated No

vember 5, 1971, which directs the State officer-defendants

in the case to submit “ a metropolitan plan of desegrega

tion” to the District Court, and the District Judge, re

peatedly referring to his “ continuing jurisdiction,” there

after limits the proceedings and proofs to the question

of how many geographically and politically independent

school districts should be compelled, by order of the Federal

Court, to join with the Detroit Public School system so

as to achieve, through massive cross-district busing of

students, a desirable racial balance in the new Federal

Court-created super-school district, is this November 5,

1971 order of the District Court a “ final decision” for

purposes of seeking judicial review?

The Petitioners contend that the answer is “ YES,”

but the United States Court of Appeals said “ NO.”

4

XI.

Are the findings of fact and conclusions of law which

underlie the decision of de jure segregation clearly er

roneous ?

The Petitioners contend that the answer is “ YES,”

hut the United States Court of Appeals refused to

answer the question.

III.

Is a metropolitan plan constitutionally inappropriate in

the complete absence of a finding either that the geo

graphically and politically independent suburban Detroit

school districts are themselves guilty of de jure segregation

or, alternatively, that the school district boundary lines

were created and maintained with the intent of promoting

a dual school system?

The Petitioners contend that the answer is “ YES,”

but the United States Court of Appeals refused to

answer the question.

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Section 1291 of Title 28, United States Code, provides:

“ The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction of

appeals from all final decisions of the district courts

of the United States, the United States District Court

for the District of the Canal Zone, the District Court

of Guam, and the District Court of the Virgin Islands,

excpt where a direct review may be had in the Supreme

Court. ’ ’

— 5—

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiffs commenced tins litigation on August 18, 1970,

against the Board of Education of the City of Detroit,

its members and superintendent of schools, the Governor,

Attorney General, State Board of Education and State

Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of Mich

igan. The State of Michigan was not named as a party

Defendant. Plaintiffs challenged, on constitutional grounds,

a legislative enactment of the State of Michigan, 1970

PA 48, MCLA 388.171a et seq; MSA 15.2298(la) et seq,

which allegedly delayed and interferred with the imple

mentation of a voluntary plan of partial high school pupil

desegregation which had been adopted by the Detroit Board

of Education. Plaintiffs further alleged the existence of

constitutionally impermissible racially identifiable pattern

of faculty and student assignments in the Detroit Public

Schools which pattern, they claimed, was the result of

official policies and practices of the defendants and their

predecessors in office.

At the conclusion of a hearing held upon Plaintiffs’

application for preliminary injunctive relief, the District

Court denied all relief on the grounds that the existence

of racial segregation in the Detroit School District had

not yet been established. The court further dismissed the

action as to the Governor and the Attorney General. Plain

tiffs promptly appealed, on an emergency basis, to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit which

declared the impugned statute (which had not been ruled

upon below) to be unconstitutional and ordered reinstate

ment of the Governor and Attorney General as parties.

433 F2d 897.

Upon remand, plaintiffs moved in the District Court

for an order requiring immediate implementation of the

voluntary plan of partial desegregation which had been

purportedly impeded by the impugned State statute. After

receiving additional plans preferred by the Detroit School

District defendants and conducting a. hearing thereon, the

district court entered an order approving an alternate plan

which plaintiffs opposed as being constitutionally insuffi

cient. Plaintiffs again claimed an emergency appeal, but

the United States Court of Appeals refused to reach the

merits of the appeal and remanded the case to the District

Court with instructions that the entire case be tried on

its merits forthwith. 438 F2d 945.

After a lengthy trial, the District Court, on September

27, 1971, entered its “ Ruling on Issue of Segregation.”

(la ). The court concluded, both as a matter of fact

and of law, that the public schools in Detroit are “ segre

gated on a racial basis” (12a), and that both state and

local defendants “ have committed acts which have been

causal factors in the segregated condition ...” (20a),

The Court went on to state:

“ Having found a de jure segregated public school

system in operation in the City of Detroit, our first

step, in considering what judicial steps must be

ta k e n ....” (26a).

Thereafter, the District Court gave certain oral instruc

tions to the counsel for the State officer-defendants. These

instructions were formalized by the Order of November

5, 1971, wherein it was ordered:

‘ ‘ The Court having entered its findings of facts and

conclusions of law on the issue of segregation on

September 27, 1971;

“ IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the State de

fendants submit a metropolitan plan of desegregation

within 120 days.” (29a-30a)

Following submission of several plans submitted by

various parties, including the defendant State Board of

Education, the Court, on March 24, 1972 proceeded to

consider whether school district lines should be revised

or ignored to combine city and suburban school popula

tions in a way to achieve integration on a metropolitan

basis. Brushing aside the arguments of the State officer-

defendants, the Court held that any further discussion

of the question of the existence of de jure segregation

had been finally foreclosed by the “ Ruling on Issue of

Segregation” .

“ The State defendants in this case take the position,

as we understand it, that- no ‘ state action’ lias had

a part in the segregation found to exist. This asser

tion disregards the findings already made by this

court, and the decision of the Court of Appeals as

w e ll . . . . (33a).

“ The schedule previously established for the hear

ing on metropolitan plans will go forward as noticed,

beginning March 28, 1972.” (36a).

Thereafter, on March 28, 1972, the Court issued its

“ Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-

Only Plans of Desegregation.” Specifically incorporating

its September-filed “ Ruling on Issue of Segregation,” the

Court found :

((

“ 1. The court has continuing jurisdiction of this

action for all purposes, including the granting of ef

fective relief. See Ruling on Issue of Segregation,

September 27, 1971.” (40a).

“ 2. On the basis of the court’s finding of illegal

school segregation, the obligation of the school de

fendants is to adopt and implement an educationally

sound, practicable plan of desegregation that promises

realistically to achieve now and hereafter the greatest

possible degree of actual school desegregation___ ”

(40a).

<<

“ That the court must look beyond the limits of the

Detroit school district for a solution to the problem

of segregation in the Detroit public schools is ob

vious-----” (42a).

Proceedings in the District Court are still continuing as

of the date of the filing of this petition.

The State officer-defendants requested review of the

District Court’s Order of November 5, 1971, in the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, by the filing

of a claim of appeal on December 3, 1971. On Motion of

the plaintiffs, the Court of Appeals, on February 23, 1972,

dismissed the appeal. (44a).

— 9—

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The Order Of November 5, 1971, Is A “Final Decision”

Within The Meaning Of Title 28 U.S.C. §1291.

Section 1291 of Title 28 provides that the Federal courts

of appeals “ shall” have jurisdiction of appeals from

“ all final decisions of the district courts.”

On scrutiny of even the limited record appended hereto

as an appendix, it indisputably appears that:

(1) The District Court has found that “ both the State

of Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education have

committed acts which have been causal factors in the

segregated condition of the public schools of the City

of Detroit.” (20a)

(2) The District Court conclusively determined that

‘ ‘ the circumstances of the case require judicial intervention

and equitable relief___ ” (27a). As the Court stated

it: “ a right and a violation have been shown.” (81a).

(3) The District Court, relying upon this ruling, has

refused to hear any more proofs or argument relating

to the question of whether there was, in fact, any state

action as a predicate for the segregated condition of the

Detroit Public Schools. (33a).

(4) The District Court, by way of equitable relief, has

rejected all available remedies other than revising or ignor

ing school district boundary lines so as to combine the

historically and geographically independent city and sub

—10

urban school populations in a way to achieve integration

on a metropolitan basis. (42a).

Thus, the special and unusual circumstances here pre

sented are that the District Court, as a matter of “ con

tinuing jurisdiction (40a), is now conducting the separate

and distinct remedy phase of the trial, a phase limited

solely to the question of how many legally separate school

districts should be lumped together, by order of the Fed

eral District Court, to the new Federal court-created super

school district of the metropolitan Detroit area.

While that remedy phase of the matter is being litigated,

the State officer-defendants here seek judicial review of

the initial phase. We seek access to a forum so that we

may question whether the finding of a “ violation” is

clearly erroneous.

No practical difficulty is thereby presented. The tran

script of testimony on the initial phase of the District

Court proceeding is already prepared. The appeal on

the initial phase can proceed without any conflict with

the continuing proceeding on the remedy phase now before

the District Court.

Indeed, the practicalities of the situation mandate re

view without further delay. The Court of Appeals, and

ultimately this Court, should review this matter before

hundreds of thousands of children are loaded onto school

buses to attend school long distances from home and the

educational programs, financing and the entire operation

of scores of school districts are disrupted. The next school

year begins in September. The District Judge has, as

yet, given no indication of when he will announce which

plan the Court is adopting or what the effective date of

—11

the plan will be, thereby leaving open the distinct possibil

ity that appellate review may not he completed prior

to the effective date of the plan, unless review commences

now.

The correctness of the decision below, finding a lack

of finality, is open to serious question. The refusal of

the Sixth Circuit to permit an appeal on this record can

not be justified in light of the rule plainly adopted by

this Court in Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 US

294, at 306-309 (1962).

In Brown, the question was whether an order for di

vestiture in a Clayton Anti-Trust Act (Title 15 U.S.C.

§25) prosecution was “ final” where the single provision

of the judgment by which its finality might he questioned

was one requiring the appellant there to propose a plan

for effectuating the trial court’s order or divestiture. The

Court found the requisite finality.

In Brown, the propriety of divestiture was considered

in the trial court and was disputed before this Court on

an “ all or nothing” basis. (370 US at 309). Here, the

question of the existence of de jure segregation was fully

considered below. Here, we dispute the ruling of de jure

segregation in the Detroit Public Schools and the later

holding that a metropolitan remedy, necessarily involving

massive cross-district busing, is constitutionally required,

on the same “ all or nothing” basis.

Repetitive judicial consideration of the same question

will not occur here any more than it did in Brown. The

issue here, like the issue in Brown, is ripe for review in

the here and now, and may, thereafter, be foreclosed.

It is axiomatic under our jurisprudential experience

that for purposes of appellate review a decision “ final”

— 12—

within the meaning of Title 28 U.S.C. §1291 “ does not

necessarily mean the last order possible to be made in

a case.” Gillespie v. United States Steel Corp., 379 US

148, at 152 (1964).

The delay in withholding review of the issue until the

full details of a busing plan have been approved by the

District Court is clearly and profoundly inimical to the

public interest. The unsettling influence of uncertainty as

to the affirmance of the initial, underlying decision of

de jure segregation, which will compel massive cross-district

busing, would only make still more difficult the task of

operating a system of free public schools.

There are issues for the here and now. The order in

question is at least within the twilight zone of finality.

A Detroit-only plan, if constitutionally required, could in

volve 300,000 children. A metropolitan plan for the De

troit and suburban school districts could involve 86 separate

school districts and 1,000,000 children. Both plans involve

massive busing of school children. The public interest here

mandates a practical rather than a technical construction

of the right of access to Federal appellate review.

II.

The Findings Of Fact, And Conclusions Of Law, Which

Underlie The Decision That De Jure Segregation Exists

In The Detroit Public School System, Are Clearly And

Patently Erroneous.

In the event that this petition is granted, the State

officer-defendants believe that they can demonstrate

through thorough analysis of the testimony and exhibits,

that the findings of fact made below — insofar as they

-1 3 -

seem to support a finding of de jure segregation — are

clearly erroneous, F.R.C.P. 52(a). The conclusions of law

are also patently in error.

It was not until 1954 that this Court reconsidered and

rejected the ‘ ‘ separate but equal ’ ’ doctrine. Brown v. Board

of Education of Topeka, 347 US 483 (1954). The Supreme

Court of the State of Michigan had, however, some 64

years prior to this Court’s decision in Broivn rejected the

“ separate but equal” doctrine as violating State law.

Ferguson v. Gies, 82 Mich 358 (1890). By Act 130 of

the Public Acts of 1885, the Michigan legislature made

it a criminal offense for any person to deny equal treat

ment to any other person, for reasons based on race, in

any place of public accommodation within this State. In

the one reported case where a school district sought to

segregate by regulation, its actions were promptly nullified

by the legislature and the Michigan Supreme Court. People

ex rel Workman v. Board of Education of Detroit, 18 Mich

399 (1869). The State of Michigan does not now have,

nor has the State ever countenanced, a “ dual school

system.” Racial segregation in public education was de

clared to be a violation of the public policy of the State

of Michigan in 1867, nearly a century in advance of this

Court’s decision in Brown. See review of public policy

of State of Michigan in Beech Grove Investment Company

v. Civil Rights Commission, 380 Mich 405, at 434-435 (1968).

The District Court, in its “ Ruling on Issue of Segre

gation,” stated the following:

“ . . . The principal causes undeniably have been popu

lation movement and housing patterns, but state and

local governmental actions, including school board

actions, have played a substantial role in promoting

segregation. It is, the Court believes, unfortunate that

-14—

we cannot deal with public school segregation on a

no-fault basis, for if racial segregation in our public

schools is an evil, then it should make no difference

whether we classify it de jure or de facto . . . [Em

phasis supplied] (20a)

Primarily, the evidence upon which the District Court

relied concerned segregated patterns in housing. None

of the defendants has any constitutional or statutory power

over housing. Much of this evidence attempted to show

that the Federal government, principally through its public

housing, YA and FHA mortgage insurance programs, had

been a willing partner with private individuals and firms

in the creation and perpetuation of racially segregated

neighborhoods, even to the point of insisting upon them.

Appendix 9a. In admitting such evidence, over continu

ing objections of defendants, the District Court ignored

the clear and binding commands of the Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit.

The Sixth Circuit — prior to deciding not to decide this

case — had quite wisely held that evidence of alleged

discrimination in the public and private housing markets

should be excluded from the trial of this type of case. The

Sixth Circuit reasoned quite correctly that such discrimina

tion is caused, if in fact it does exist, by persons other

than the school officials. It is a situation the Sixth Circuit

reasoned, over which educational officials may have no

power. We emphasize here that none of the defendants

has any power over housing. Therefore, the Sixth Circuit

concluded, appropriate relief is available as against those

who infringed upon rights in housing in a civil action with

those wrong-doers as defendants, rather than in a school

case with school officials as defendants. Deal v. Cincinnati

Board of Ed/ucation (Deal I), 369 F2d 55, at 60-61 (CA

6, 1966), cert den 389 US 847. This ruling was restated

15-

with vigor in Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education (Deal

II), 419 F2d 1387, at 1392 (OA 6, 1969), cert den 402

US 962.

The concept has also been stated in Davis v. School

District of Pontiac, 309 F Supp 734 (ED Mich, 1970),

aff’d 443 F2d 573 (CA 6, 1971) and Swann v. Charlotte-

MecMenburg Board of Education, 402 US 1, at 22-23, (1971),

where this Court said:

“ The constant theme and thrust of every holding

from Brown I to date is that state-enforced separation

of races in public schools is discrimination that violates

the Equal Protection Clause. The remedy commanded

was to dismantle dual school systems.

“ We are concerned in these cases with the elimina

tion of the discrimination inherent in the dual school

systems, not with myriad factors of human existence

which can cause discrimination in a multitude of ways

on racial, religious, or ethnic grounds. The targ-et of the

cases from Brown I to the present was the dual school

system. The elimination of racial discrimination in

public schools is a large task and one that should not be

retarded by efforts to achieve broader purposes lying

beyond the jurisdiction of school authorities. One

vehicle can carry only a limited amount of baggage.

It would not serve the important objective of Brown I

to seek to use school desegregation cases for purposes

beyond their scope, although desegregation of schools

ultimately will have impact on other forms of dis

crimination. We do not reach in this case the question

whether a showing that school segregation is a con

sequence of other types of state action, without any

discriminatory action by the school authorities, is a

constitutional violation requiring remedial action by

a school desegregation decree. This case does not

present that question and we therefore do not decide

it.

“ Our objective in dealing with the issues presented

by these cases is to see that school authorities exclude

no pupil of a racial minority from any school, directly

or indirectly, on account of race; it does not and

cannot embrace all the problems of racial prejudice,

even when those problems contribute to dispropor

tionate racial concentrations in some schools.”

The District Court, in its decision on de jure segregation

found “ . . . that both the State of Michigan and the Detroit

Board of Education have committed acts which have been

causal factors in the segregated condition of the public

schools of the City of Detroit . . . ” (20a). It must be

emphasized that the State of Michigan is not a party de

fendant herein. There is no recognized principle in our

jurisprudence under which a suit against certain state

officers may be used as a launching pad for findings against

the state itself.

Aside from evidence relating to housing patterns, the

record contains no evidence of a pattern or scheme, but

rather evidence which at best shows only a few random and

isolated incidents. Thus, for example, one finding of fact

relates to an isolated incident in which a lowly functionary

of the local school board had authorized the busing of a

small number of black students past a white school to

attend a newer school in a black neighborhood. (11a). This

incident was isolated in scope to a few students during a

relatively short period of time. The record shows that

the problem was promptly corrected as soon as it was

brought to the attention of policy-making officials.

— 17-

The District Court ruled, based on 30 specific findings,

that there was no de jure segregation of faculty in the

Detroit public schools. Yet, the District Court concluded

that the same defendants were guilty of de jure segregation

as to the assignment of pupils. (15a).

The District Court’s findings concerning de jure segrega

tion in school attendance patterns were, in large part, of

the most general nature. In Keyes v School District No. 1,

Denver, Colorado, 445 F2d 990, 1002-1007 (1971), Cert

grant, ____ US ____ (1972), 30 L Ed 2d 728 (1972), the

Tenth Circuit Court affirmed findings of de jure segrega

tion as to specific schools, but no others, and ordered a

remedy only in those specific schools where de jure segrega

tion existed. Herein, the District Court made broad findings

of de jure segregation as to pupil attendance and, on that

basis, jumped to a metropolitan remedy without considering

specific schools in making its findings.

This appeal, therefore, affords an excellent vehicle for

a determination by this Court as to whether as a matter

of law a condition of de jure segregation may be said to

exist where the evidence shows little more than a few un

related incidents, isolated as to scope and duration, in

volving local officials, and no wrongdoing by the State

officer-defendants, hut some possible wrong-doing in the

area of housing by agencies of the Federal government and

by private individuals.

I f de jure segregation can be said to exist on this

record, then it appears that there is no longer any valid

distinction to be made between de jure and de facto segrega

tion. (20a). And, if that is so, this Court should clearly so

state.

— 18—

III.

A Metropolitan Plan Of Desegregation Is Constitutionally

Inappropriate In The Complete Absence Of A Finding

Either That The Geographically And Politically Inde

pendent Surburban Detroit School Districts Are Them

selves Guilty Of De Jure Segregation Or, Alternatively,

That The School District Boundary Lines Were Created

And Maintained With The Intent Of Promoting A Dual

School System.

This is not ordinary, run-of-the-mill litigation. The case

poses— if this Court chooses to acknowledge and reach

it—a significant aspect of a wide, growing and disturbing

problem.

The District Judge in this case first, in substance,

abolished the distinction between segregation de facto and

segregation de jure. (Reason No. II, supra.)

Then, the District Judge proceeded to decide (1) that

busing was the only adequate remedy available, (2) that a

Detroit-only busing plan was inadequate, (3) and, therefore,

that a metropolitan plan was the only possible remedy in

this case. (35a; 41a; 42a).

Having so decided, the District Judge then commenced

a new phase of the case limited to the question of how many

of the 700,000 or so children in the 86 independent suburban

Detroit school districts should be included in his metropoli

tan plan.

Busing is, of course, an available instrument to provide

a better educational opportunity to children in substandard

or de jure segregated schools. For such children, an im

-1 9 -

perfect answer today may prove to be far more valuable

than a more perfect answer tomorrow. For a child, tomor

row may be too late. Busing must, however, be recognized

for what it is, an imperfect and temporary tool, a crutch

and not a cure.

As far as we know, neither this Court nor any Court of

Appeals has ever approved the use of busing on the scale

here contemplated. While a few decisions do' speak of

“piercing the veil” where a system of de jure segregation

is perpetuated by carefully gerrymandered school district

lines, no decision has ever approved the lumping of polit

ically and geographically independent suburban school

districts into an urban busing plan simply because they

happen to be there. Ill

No finding of the District Court indicates the existence

of de jure segregation in the suburban school districts.

Likewise, no finding of the District Court indicates that

these school district lines were drawn for any improper

purpose or by any improper method.

Then, there is the whole question of the jurisdiction,

i.e., the power, of the Federal District Court to adopt a

metropolitan plan without a specific finding of de jure

segregation as to the included suburban school districts.

If the true basis of the District Court’s action rests upon

an implicit finding that the schools in Detroit are sub

standard, can the Judge without any further ado simply

order children bused into these schools from the suburbs!

Is not the answer to this problem in the area of school

[1]

Compare Haney v County Board of Sevier County, 410 F2d 920 (CA 8,

1969) and Bradley v School Board, of the City of Richmond, ,__ ___ F Supp

__ ___ (ED Va, dec. Jan. 5, 1972), where the Court found a state-wide

policy of de jure segregation in the schools.

-20—

finance and construction rather than massive cross-district

busing?

Can the District Court alter local control of schools by

creating a super school district that might well thereafter

constitute the largest school district in the United States?

Even assuming that busing is an appropriate instrument

for dealing with the problem of the children attending the

Detroit School System, this case poses the important and

difficult question of whether a metropolitan plan of busing

may ever be used by a Federal court in the total absence of

any finding of a metropolitan-wide de jure policy of segre

gation.

CONCLUSION

For the aforegoing reasons, a write of certiorari should

issue to review the judgment of the Sixth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

ROBERT A. DERENGOSKI

Solicitor General

EUGENE KRASICKY

Assistant Attorney General

STEWART H. FREEMAN

Assistant Solicitor General

Counsel for Petitioners

The Seven Story Office Building

525 W. Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Dated: May 5, 1972

APPENDIX

Index to Appendix

Page

United States District Court, Eastern District

of Michigan, Southern Division:

Ruling on Issue of Segregation .._______________ la

Order of November 5, 1971 ................... ..... ............. 29a

Ruling On Propriety of Considering

A Metropolitan Remedy To Accomplish

Desegregation Of The Public Schools

Of The City of Detroit____ ...______________________ 31a

Findings Of Fact And Conclusions Of Law

On Detroit-Only Plans Of Desegregation ________ 37a

United States Court of Appeals For The Sixth Circuit:

Order Of The United States Court Of Appeals

For the Sixth Circuit _____ ____________ _______ _ 44a

Ruling on Segregation

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

WILLIAM G. M1LLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants,

DETROIT FEDERATION OF CIVIL ACTION

TEACHERS, LOCAL No. 231, NO. 35257

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF

TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenor

RULING ON ISSUE OF SEGREGATION

This action was commenced August 18,1970, by plaintiffs,

the Detroit Branch of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People* and individual parents

and students, on behalf of a class later defined by order of

the Court dated February 16, 1971, to include “all school

children of the city of Detroit and all Detroit resident

parents who have children of school age.” Defendants are

the Board of Education of the City of Detroit, its members

and its former superintendent of schools, Dr. Norman A.

* The standing of the NAACP as a proper party plaintiff was not con

tested by the original defendants and the Court expresses no opinion on

the matter.

2a Ruling on Segregation

Drachler, the Governor, Attorney General, State Board

of Education and State Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion of the State of Michigan. In their complaint, plaintiffs

attacked a statute of the State of Michigan known as Act

48 of the 1970 Legislature on the ground that it put the

State of Michigan in the position of unconstitutionally

interfering with the execution and operation of a voluntary

plan of partial high school desegregation (known as the

April 7, 1970 Plan) which had been adopted by the Detroit

Board of Education to be effective beginning with the fall

1970 semester. Plaintiffs also alleged that the Detroit Public

School System was and is segregated on the basis of race

as a result of the official policies and actions of the de

fendants and their predecessors in office.

Additional parties have intervened in the litigation since

it was commenced. The Detroit Federation of Teachers

(DFT) which represents a majority of Detroit Public School

teachers in collective bargaining negotiations with the

defendant Board of Education, has intervened as a de

defendant, and a group of parents has intervened as de

fendants.

Initially the matter was tried on plaintiffs’ motion for

preliminary injunction to restrain the enforcement of

Act 48 so as to permit the April 7 Plan to be implemented.

On that issue, this Court ruled that plaintiffs were not

entitled to a preliminary injunction since there had been no

proof that Detroit has a segregated school system. The

Court of Appeals found that the “ implementation of the

April 7 Plan was thwarted by State action in the form of

the Act of the Legislature of Michigan,” (433 F.2d 897,

902), and that such action could not be interposed to delay,

obstruct or nullify steps lawfully taken for the purpose of

protecting rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Ruling on Segregation 3a

The plaintiffs then sought to have this Court direct the

defendant Detroit Board to implement the April 7 Plan by

the start of the second semester (February, 1971) in order

to remedy the deprivation of constitutional rights wrought

by the unconstitutional statute. In response to an order of

the Court, defendant Board suggested two other plans, along

with the April 7 Plan, and noted priorities, with top priority

assigned to the so-called “Magnet Plan.” The Court acceded

to the wishes of the Board and approved the Magnet Plan.

Again, plaintiffs appealed but the appellate court refused

to pass on the merits of the plan. Instead, the case was

remanded with instructions to proceed immediately to a

trial on the merits of plaintiffs’ substantive allegations

about the Detroit School System. 438 F.2d 945 (6th Cir,

1971).

Trial, limited to the issue of segregation, began April 6,

1971 and concluded on July 22, 1971, consuming 41 trial

days, interspersed by several brief recesses necessitated

by other demands upon the time of Court and counsel.

Plaintiffs introduced substantial evidence in support of

their contentions, including expert and factual testimony,

demonstrative exhibits and school board documents. At the

close of plaintiffs’ case, in chief, the Court ruled that they

had presented a prima facie case of state imposed segrega

tion in the Detroit Public Schools; accordingly, the Court

enjoined (with certain exceptions) all further school con

struction in Detroit pending the outcome of the litigation.

The State defendants urged motions to dismiss as to

them. These were denied by the Court.

At the close of proofs intervening parent defendants

(Denise Magdowski, et al.) filed a motion to join, as

parties 85 contiguous “ suburban” school districts—all with

in the so-called Larger Detroit Metropolitan area. This

4a Ruling on Segregation

motion, was taken under advisement pending* the determina

tion of the issue of segregation.

It should be noted that, in accordance with earlier rulings

of the Court, proofs submitted at previous hearings in the

cause, were to be and are considered as part of the proofs

of the hearing on the merits.

In considering the present racial complexion of the

City of Detroit and its public school system we must first

look to the past and view in perspective what has happened

in the last half century. In 1920 Detroit was predominantly

white city—91%—and its population younger than in more

recent times. By the year 1960 the largest segment of the

city’s white population was in the age range of 35 to 50

years, while its black population was younger and of child

bearing age. The population of 0-15 years of ag*e constituted

30% of the total population of which 60% were white and

40% were black. In 1970 the white population was princi

pally aging—45 years—while the black population was

younger and of childbearing age. Childbearing blacks

equaled or exceeded the total white population. As older

white families without children of school age leave the city

they are replaced by younger black families with school age

children, resulting in a doubling of enrollment in the local

neighborhood school and a complete change in student

population from white to black. As black inner city resi

dents move out of the core city they “ leap-frog” the resi

dential areas nearest their former homes and move to

areas recently occupied by whites.

The population of the City of Detroit reached its high

est point in 1950 and has been declining by approximately

169,500 per decade since then. In 1950, the city population

constituted 61% of the total population of the standard

Ruling on Segregation 5a

metropolitan area and in 1970 it was but 36% of the metro

politan area population. The suburban population has in

creased by 1,978,000 since 1940. There has been a steady

out-migration of the Detroit population since 1940. Detroit

today is principally a conglomerate of poor black and white

plus the aged. Of the aged, 80% are white.

If the population trends evidenced in the federal decennial

census for the years 1940 through 1970 continue, the total

black population in the City of Detroit in 1980 will be ap

proximately 840,000, or 53.6% of the total. The total popula

tion of the city in 1970 is 1,511,000 and, if past trends con

tinue, will be 1,338,000 in 1980. In school year 1960-61,

there were 285,512 students in the Detroit Public Schools

of which 130,765 were black. In school year 1966-67, there

were 297,035 students, of which 168,299 were black. In

school year 1970-71 there were 289,743 students of which

184,194 were black. The percentage of black students in

the Detroit Public Schools in 1975-76 will be 72.0%, in

1980-81 will be 80.7% and in 1992 it will be virtually 100%

if the present trends continue. In 1960, the non-white

population, ages 0 years to 19 years, was as follows:

0— 4 years 42%

5— 9 years 36%

10—14 years 28%

15—19 years 18%

In 1970 the non-white population, ages 0 years to 19 years,

was as follows:

0—- 4 years 48%

5—■ 9 years 50%

10—14 years 50%

15—19 years 40%

Ruling on Segregation6a

The black population as a percentage of the total popula-

tion in the City of Detroit was:

(a) 1900 1.4%

(b) 1910 1.2%

(c) 1920 4.1%

(d) 1930 7.7%

(e) 1940 9.2%

(f) 1950 16.2%

(g) 1960 28.9%

(b) 1970 43.9%

The black population as a percentage of total student

population of the Detroit Public Schools was as follows:

(a) 1961 45.8%

(b) 1963 51.3%

(c) 1964 53.0%

(d) 1965 54.8%

(e) 1966 56.7%

(f) 1967 58.2%

(g) 1968 59.4%

(b) 1969 61.5%

(i) 1970 63.8%

For the years indicated the housing characteristics in the

City of Detroit were as follows:

(a) 1960 total supply of hous

ing units was 553,000

(b) 1970 total supply of hous

ing units was 530,770

The percentage decline in the white students in the

Detroit Public Schools during the period 1961-1970 (53.6%

in 1960; 34.8% in 1970) has been greater than the per

centage decline in the white population in the City of

Ruling on Segregation 7a

Detroit during the same period (70.8% in 1960; 55.21%

in 1970), and correlatively, the percentage increase in

black students in the Detroit Public Schools during the

nine-year period 1961-1970 (45.8% in 1961; 63.8% in 1970)

has been greater than the percentage increase in the

black population of the City of Detroit during the ten-

year period 1960-1970 (28.9% in 1960; 43.9% in 1970).

In 1961 there were eight schools in the system with

out white pupils and 73 schools with no Negro pupils. In

1970 there were 30 schools with no white pupils and 11

schools with no Negro pupils, an increase in the number

of schools without white pupils of 22 and a decrease in

the number of schools without Negro pupils of 62 in this

ten-year period. Between 1968 and 1970 Detroit experienced

the largest increase in percentage of black students in the

student population of any major northern school district.

The percentage increase in Detroit was 4.7 % as contrasted

with

New York 2.0%

Los Angeles 1.5%

Chicago 1.9%

Philadelphia 1.7%

Cleveland 1.7%

Milwaukee 2.6%

St. Louis 2.6%

Columbus 1.4%

Indianapolis 2.6%

Denver 1.1%

Boston 3.2%

San Francisco 1.5%

Seattle 2.4%

in 1960, there were 266 schools in the Detroit School sys

tem. In 1970, there were 319 schools in the Detroit School

system.

8a Ruling on Segregation

In the Western, Northwestern, Northern, Murray, North

eastern, Kettering, King and Southeastern high school serv

ice areas, the following conditions exist at a level signifi

cantly higher than the city average:

(a) Poverty in children

(b) Family income below poverty level

(c) Kate of homicides per population

(d) Number of households headed by females

(e) Infant mortality rate

(f) Surviving infants with neurological

defects

(g) Tuberculosis cases per 1,000 population

(h) High pupil turnover in schools

The City of Detroit is a community generally divided by

racial lines. Residential segregation within the city and

throughout the larger metropolitan area is substantial, per

vasive and of long standing. Black citizens are located in

separate and distinct areas within the city and are not

generally to be found in the suburbs. While the racially

unrestricted choice of black persons and economic factors

may have played some part in the development of this

pattern of residential segregation, it is, in the main, the

result of past and present practices and customs of racial

discrimination, both public and private, which have and

do restrict the housing opportunities of black people. On

the record there can be no other finding.

Governmental actions and inaction at all levels, federal,

state and local, have combined, with those of private

organizations, such as loaning institutions and real estate

associations and brokerage firms, to establish and to

Ruling on Segregation 9a

maintain the pattern of residential segregation throughout

the Detroit metropolitan area. It is no answer to say that

restricted practices grew gradually (as the black popula

tion in the area increased between 1920 and 1970), or that

since 1948 racial restrictions on the ownership of real prop

erty have been removed. The policies pursued by both

government and private persons and agencies have a con

tinuing and present effect upon the complexion of the

community—as we know, the choice of a residence is a

relatively infrequent affair. For many years FHA and

VA openly advised and advocated the maintenance of

“ harmonious” neighborhoods, i.e., racially and economically

harmonious. The conditions created continue. While it

would be unfair to charge the present defendants with what

other governmental officers of agencies have done, it can

be said that the actions or the failure to act by the respon

sible school authorities, both city and state, were linked to

that of these other governmental units. When we speak

of governmental action we should not view the different

agencies as a collection of unrelated units. Perhaps the

most that can be said is that all of them, including the

school authorities, are, in part, responsible for the segre

gated condition which exists. And we note that just as

there is an interaction between residential patterns and

the racial composition of the schools, so there is a cor

responding effect on the residential pattern by the racial

composition of the schools.

Turning now to the specific and pertinent (for our pur

poses) history of the Detroit school system so far as it in

volves both the local school authorities and the state school

authorities, we find the following:

During the decade beginning in 1950 the Board created

and maintained optional attendance zones in neighborhoods

undergoing racial transition and between high school at-

10a Ruling on Segregation

tendance areas of opposite predominant racial composi

tions. In 1959 there were eight basic optional attendance

areas affecting 21 schools. Optional attendance areas pro

vided pupils living within certain elementary areas a choice

of attendance at one of two high schools. In addition there

was at least one optional area either created or existing in

1960 between two junior high schools of opposite predomi

nant racial components. All of the high school optional

areas, except two, were in neighborhoods undergoing racial

transition (from white to black) during the 1950s. The two

exceptions were: (1) the option between Southwestern

(61.6% black in 1960) and Western (15.3% black); (2) the

option between Denby (0% black) and Southeastern (30.9%

black). With the exception of the Denby-Southeastem

option (just noted) all of the options were between high

schools of opposite predominant racial compositions. The

Southwestern-Western and Denby-Southeastem optional

areas are all white on the 1950, 1960 and 1970 census maps.

Both Southwestern and Southeastern, however, had sub

stantial white pupil populations, and the option allowed

whites to escape integration. The natural, probable, fore

seeable and actual effect of these optional zones was to allow

white youngsters to escape identifiably “ black” schools.

There had also been an optional zone (eliminated between

1956 and 1959) created in “ an attempt. . . to separate Jews

and Gentiles within the system,” the effect of which was

that J©wish youngsters went to Mumford High School and

Gentile youngsters went to Cooley. Although many of these

optional areas had served their purpose by 1960 due to the

fact that most of the areas had become predominantly black,

one optional area (Southwestern-We stern affecting Wilson

Junior High graduates) continued until the present school

year (and will continue to effect 11th and 12th grade white

youngsters who elected to escape from predominantly black

Southwestern to predominantly white Western High

Ruling on Segregation 11a

School). Mr. Henrickson, the Board’s general fact witness,

who was employed in 1959 to, inter alia, eliminate optional

areas, noted in 1967 that: “ In operation Western appears to

be still the school to which white students escape from

predominantly Negro surrounding schools.” The effect of

eliminating this optional area (which affected only 10th

graders for the 1970-71 school year) was to decrease South

western from 86.7% black in 1969 to 74.3% black in 1970.

The Board, in the operation of its transportation to

relieve overcrowding policy, has admittedly bused black

pupils past or away from closer white schools with available

space to black schools. This practice has continued in

several instances in recent years despite the Board’s avowed

policy, adopted in 1967, to utilize transportation to in

crease integration.

With one exception (necessitated by the burning of a

white school), defendant Board has never bused white

children to predominantly black schools. The Board has

not bused white pupils to black schools despite the enormous

amount of space available in inner-city schools. There were

22,961 vacant seats in schools 90% or more black.

The Board has created and altered attendance zones,

maintained and altered grade structures and created and

altered feeder school patterns in a manner which has had

the natural, probable and actual effect of continuing black

and white pupils in racially segregated schools. The Board

admits at least one instance where it purposefully and

intentionally built and maintained a school and its at

tendance zone to contain black students. Throughout the

last decade (and presently) school attendance zones of

opposite racial compositions have been separated by north-

south boundary lines, despite the Board’s awareness (since

at least 1962) that drawing boundary lines in an east-west

direction would result in significant integration. The

12a Ruling on Segregation

natu ral and actual effect of these acts and failures to act

has been the creation and perpetuation of school segrega

tion. There has never been a feeder pattern or zoning

change which placed a predominantly white residential

area into a predominantly black school zone or feeder

pattern. Every school which was 90% or more black in

1960, and which is still in use today, remains 90% or more

blaek. Whereas 65.8% of Detroit’s black students attended

90% or more black schools in 1960, 74.9% of the black stu

dents attended 90% or more black schools during the

1970-71 school year.

The public schools operated by defendant Board are

thus segregated on a racial basis. This racial segregation

is in part the result of the discriminatory acts and omissions

of defendant Board.

In 1966 the defendant State Board of Education and

Michigan Civil Rights Commission issued a Joint Policy

Statement on Equality of Educational Opportunity, requir

ing that

“Local school boards must consider the factor of

racial balance along with other educational considera

tions in making decisions about selection of new school

sites, expansion of present facilities . . . . Each of these

situations presents an opportunity for integration.”

Defendant State Board’s “ School Plant Planning Hand

book” requires that

“ Care in site location must be taken if a serious

transportation problem exists or if housing patterns

in an area would result in a school largely segregated

on racial, ethnic, or socio-economic lines.”

Ruling on Segregation 13a

The defendant City Board has paid little heed to these

statements and guidelines. The State defendants have sim

ilarly failed to take any action to effectuate these policies.

Exhibit NN reflects construction (new or additional) at

14 schools which opened for use in 1970-71; of these 14

schools, 11 opened over 90% black and one opened less

than 10% black. School construction costing $9,222,000 is

opening at Northwestern High School which is 99.9%

black, and new construction opens at Brooks Junior High,

which is 1.5% black, at a cost of $2,500,000. The construc

tion at Brooks Junior High plays a dual segregatory role:

not only is the construction segregated, it will result in a

feeder pattern change which will remove the last majority

white school from the already almost all-black Mackenzie

High School attendance area.

Since 1959 the Board has constructed at least 13 small

primary schools with capacities of from 300 to 400 pupils.

This practice negates opportunities to integrate, “ contains”

the black population and perpetuates and compounds school

segregation.

The State and its agencies, in addition to their general

responsibility for and supervision of public education, have

acted directly to control and maintain the pattern of segre

gation in the Detroit schools. The State refused, until this

session of the legislature, to provide authorization or funds

for the transportation of pupils within Detroit regardless

of their poverty or distance from the school to which they

were assigned, while providing in many neighboring, mostly

white, suburban districts the full range of state supported

transportation. This and other financial limitations, such

as those on bonding and the working of the state aid formula

whereby suburban districts were able to make far larger per

pupil expenditures despite less tax effort, have created and

perpetuated systematic educational inequalities.

14a Ruling on Segregation

The State, exercising what Michigan courts have held

to be is “plenary power” which includes power “ to use a

statutory scheme, to create, alter, reorganize or even dis

solve a school district, despite any desire of the school dis

trict, its board, or the inhabitants thereof,” acted to re

organize the school district of the City of Detroit.

The State acted through Act 48 to impede, delay and

minimize racial integration in Detroit schools. The first

sentence of Sec. 12 of the Act was directly related to the

April 7, 1970 desegregation plan. The remainder of the

section sought to prescribe for each school in the eight

districts criterion of “ free choice” (open enrollment) and

“ neighborhood schools” (“nearest school priority accept

ance” ), which had as their purpose and effect the main

tenance of segregation.

In view of our findings of fact already noted we think

it unnecessary to parse in detail the activities of the local

board and the state authorities in the area of school con

struction and the furnishing of school facilities. It is our

conclusion that these activities were in keeping, generally,

with the discriminatory practices which advanced or

perpetuated racial segregation in these schools.

It would be unfair for us not to recognize the many fine

steps the board has taken to advance the cause of quality

education for all in terms of racial integration and human

relations. The most obvious of these is in the field of faculty

integration.

Plaintiffs urge the Court to consider allegedly discrimina

tory practices of the Board with respect to the hiring, as

signment and transfer of teachers and school administrators

during a period reaching back more than 15 years. The

short answer to that must be that black teachers and school

Ruling on Segregation 15a

administrative personnel were not readily available in

that period. The Board and the intervening defendant union

have followed a most advanced and exemplary course in

adopting and carrying out what is called the “balanced

staff concept”—which seeks to balance faculties in each

school with respect to race, sex and experience, with pri

mary emphasis on race. More particularly, we find:

1. "With the exception of affirmative policies designed to

achieve racial balance in instructional staff, no teacher in

the Detroit Public Schools is hired, promoted or assigned

to any school by reason of his race.

2. In 1956, the Detroit Board of Education adopted the

rules and regulations of the Fair Employment Practices

Act as its hiring and promotion policy and has adhered to

this policy to date.

3. The Board has actively and affirmatively sought

out and hired minority employees, particularly teachers and

administrators, during the past decade.

4. Between 1960 and 1970, the Detroit Board of Educa

tion has increased black representation among its teachers

from 23.3% to 42.1%, and among its administrators from

4.5% to 37.8%.

5. Detroit has a higher proportion of black administra

tors than any other city in the country.

6. Detroit ranked second to Cleveland in 1968 among

the 20 largest northern city school districts in the per

centage of blacks among the teaching faculty and in 1970

surpassed Cleveland by several percentage points.

7. The Detroit Board of Education currently employs

black teachers in a greater percentage than the percentage

of adult black persons in the City of Detroit.

16a Ruling on Segregation

8. Since 1967, more blacks than whites have been placed

in high administrative posts with the Detroit Board of

Education.

9. The allegation that the Board assigns black teachers

to black schools is not supported by the record.

10. Teacher transfers are not granted in the Detroit

Public Schools unless they conform with the balanced staff

concept.

11. Between 1960 and 1970, the Detroit Board of Educa

tion reduced the percentage of schools without black

faculty from 36.3% to 1.2%, and of the four schools cur

rently without black faculty, three are specialized trade

schools where minority faculty cannot easily be secured.

12. In 1968, of the 20 largest northern city school dis

tricts, Detroit ranked fourth in the percentage of schools

having one or more black teachers and third in the per

centage of schools having three or more black teachers.

13. In 1970, the Board held open 240 positions in schools

with less than 25% black, rejecting white applicants for

these positions until qualified black applicants could be

found and assigned.

14. In recent years, the Board has come under pressure

from large segments of the black community to assign male

black administrators to predominantly black schools to

serve as male role models for students, but such assign

ments have been made only where consistent with the

balanced staff concept.

15. The numbers and percentages of black teachers in

Detroit increased from 2,275 and 21.6%, respectively, in

Ruling on Segregation 17a

February, 1961, to 5,106 and 41.6%, respectively, in October,

1970.

16. Tbe number of schools by percent black of staffs

changed from October, 1963 to October, 1970 as follows:

Number of schools without black teachers—decreased

from 41, to 4.

Number of schools with more than 0%, but less than

10% black teachers—decreased from 58, to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black

teachers—decreased from 99, to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers—

increased from 72, to 124.

17. The number of schools by percent black of staffs

changed from October, 1969 to October, 1970, as follows:

Number of schools without black teachers—decreased

from 6, to 4.

Number of schools with more than 0%, but less than

10% black teachers—decreased from 41, to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black

teachers—decreased from 47, to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers

—increased from 120, to 124.

18. The total number of transfers necessary to achieve

a faculty racial quota in each school corresponding to the

system-wide ratio, and ignoring all other elements is, as

of 1970, 1,826.

19. If account is taken of other elements necessary to

assure quality integrated education, including qualifica

tions to teach the subject area and grade level,, balance of

18a Ruling on Segregation

experience, and balance of sex, and further account is taken

of the uneven distribution of black teachers by subject

taught and sex, the total number of transfers which would

be necessary to achieve a faculty racial quota in each school

corresponding to the system-wide ratio, if attainable at all,

would be infinitely greater.

20. Balancing of staff by qualifications for subject, and

grade level, then by race, experience and sex, is educa

tionally desirable and important.

21. It is important for students to have a successful

role model, especially black students in certain schools, and

at certain grade levels.

22. A quota of racial balance for faculty in each school

which is equivalent to the system-wide ratio and without

more is educationally undesirable and arbitrary.

23. A severe teacher shortage in the 1950s and 1960s

impeded integration-of-faculty opportunities.

24. Disadvantageous teaching conditions in Detroit in

the 1960s—salaries, pupil mobility and transiency, class

size, building conditions, distance from teacher residence,

shortage of teacher substitutes, etc.—made teacher recruit

ment and placement difficult.

25. The Board did not segregate faculty by race, but

rather attempted to fill vacancies with certified and qua

lified teachers who would take offered assignments.

26. Teacher seniority in the Detroit system, although

measured by system-wide service, has been applied con

sistently to protect against involuntary transfers and

“ bumping” in given schools.

Ruling on Segregation 19a

27. Involuntary transfers of teachers have occurred

only because of unsatisfactory ratings or because of decrease

of teacher services in a school, and then only in accordance

with balanced staff concept.

28. There is no evidence in the record that Detroit

teacher seniority rights had other than equitable purpose

or effect.

29. Substantial racial integration of staff can be a-

chieved, without disruption of seniority and stable teaching

relationships, by application of the balanced staff concept

to naturally occurring vacancies and increases and reduc

tions of teacher services.

30. The Detroit Board of Education has entered into

successive collective bargaining contracts with the Detroit

Federation of Teachers, which contracts have included pro

visions promoting integration of staff and students.

The Detroit School Board has, in many other instances

and in many other respects, undertaken to lessen the impact

of the forces of segregation and attempted to advance the

cause of integration. Perhaps the most obvious one was the

adoption of the April 7 Plan. Among other things, it has

denied the use of its facilities to groups which practice

racial discrimination; it does not permit the iise of its

facilities for discriminatory apprentice training programs;

it has opposed state legislation which would have the effect

of segregating the district; it has worked to place black

students in craft positions in industry and the building

trades; it has brought about a substantial increase in the

percentage of black students in manufacturing and con

struction trade apprenticeship classes; it became the first

public agency in Michigan to adopt and implement a policy

requiring affirmative act of contractors with which it deals

20a Ruling on Segregation

to insure equal employment opportunities in their work

forces; it has been a leader in pioneering the use of multi

ethnic instructional material, and in so doing* has had an

impact on publishers specializing in producing school texts

and instructional materials; and it has taken other note

worthy pioneering steps to advance relations between the

white and black races.

In conclusion, however, we find that both the State of

Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education have com

mitted acts which have been causal factors in the segregated

condition of the public schools of the City of Detroit. As

we assay the principles essential to a finding of de jure

segregation, as outlined in rulings of the United States

Supreme Court, they are:

1. The State, through its officers and agencies, and

usually, the school administration, must have taken some

action or actions with a purpose of segregation.

2. This action or these actions must have created or

aggravated segregation in the schools in question.

3. A current condition of segregation exists. We find

these tests to have been met in this case. We recognize

that causation in the case before us is both several and

comparative. The principal causes undeniably have been

population movement and housing patterns, but state and

local governmental actions, including school board ac

tions, have played a substantial role in promoting segrega

tion. It is, the Court believes, unfortunate that we cannot

deal with public school segregation on a no-fault basis, for

if racial segregation in our public schools is an evil, then

it should make no difference whether we classify it de jure

or de facto. Our objective, logically, it seems to us, should

be to remedy a condition which we believe needs correction.

Ruling on Segregation 21a

In the most realistic sense, if fault or blame must be found

it is that of the community as a whole, including, of course,

the black components. We need not minimize the effect of

the actions of federal, state and local governmental officers

and agencies, and the actions of loaning institutions and

real estate firms, in the establishment and maintenance of

segregated residential patterns—which lead to school segre