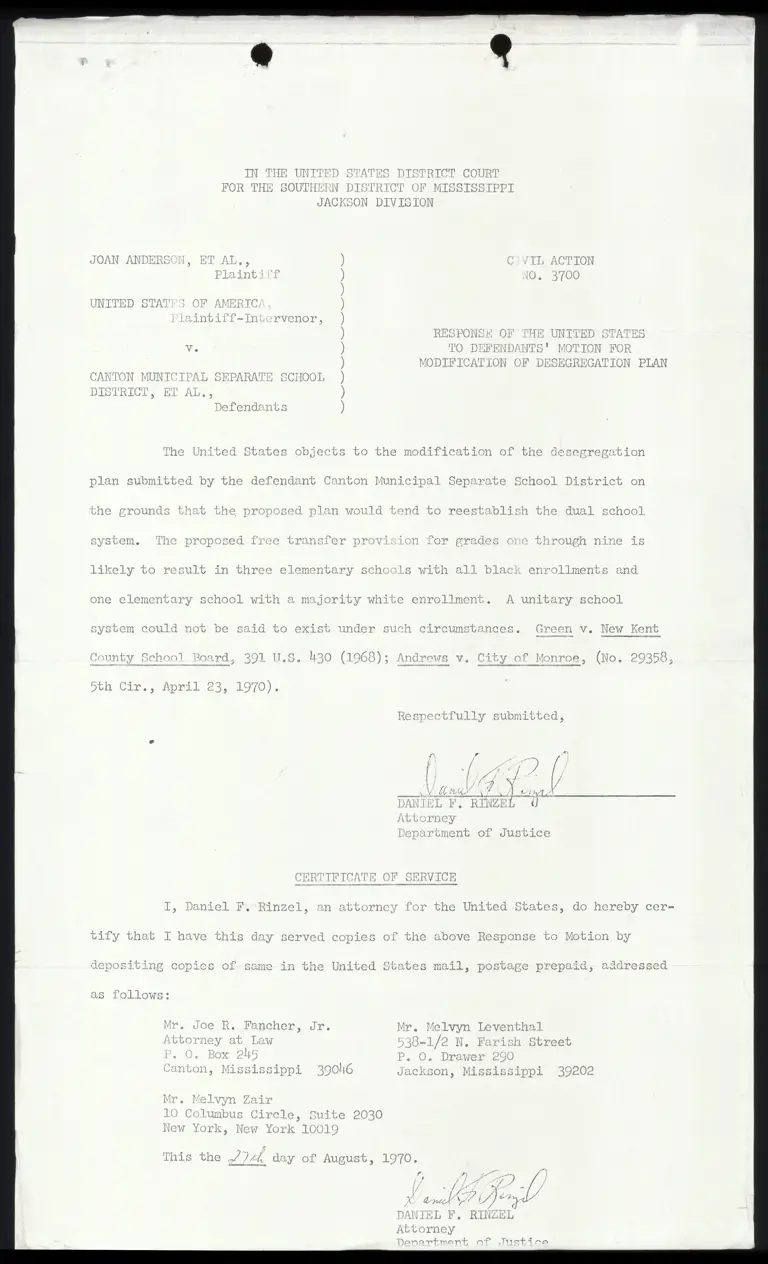

Response of the United States to Defendants' Motion for Modification of Desegregation Plan

Public Court Documents

August 27, 1970

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Response of the United States to Defendants' Motion for Modification of Desegregation Plan, 1970. b91466c5-d267-f011-bec2-7c1e52467ee8. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/297ff98b-801a-4bcf-97cf-70f846c34ff2/response-of-the-united-states-to-defendants-motion-for-modification-of-desegregation-plan. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

JACKSON DIVISION

UNITED STATIS OF AMERTC )

)

) RESPONSE OF THE UN] TA

v. ) TO DEFENDANTS' MOTION FOR

) MODIFICATION OF DESEGREGATION PLAN

\ CANTON MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL

DISTRICT, ET AL, )

Defendants )

The United States objects to the modification of the desegregation

plan submitted by the defendant Canton Municipal Separate School District on

lan would tend to reestablish the dual school fo

.

I fi

o

C system. The proposed free transfer provision for grades « through nine

likely to result in three elementary schools with all black enrollments and

school with a majority white enrollment. A unitary school ~~

7

nd

m

(S

V

Jo

t

fo

]

=

~

~

\:

, under such circumstances. Green v. New Kent

Wr T——

drows vv. City nroe, (No, 29358

creer ——-

56h Civ. April 23.1970),

Attorney

Department of Justice

SERVICE

I, Daniel F.“Rinzel, an attorney for the United States, do hereby cer-

the above Response to Motion by

] . ' , RL be bt! : : ;

1 \ ( YONT ~ a ~ OW + n i - Pat ( 1 4 ~ : [» a | ~~ C 4 [so oe YILNYRN MN NY 1 ~ AA VR CY A

NOS1L 12 C OPCS of Same in tac United nouaves maia, POS Lage pre JA LG SRT RA SIS ISIC 0F

Mr. Joe R. Fancher, Jr. Mr. Melvyn leventhal

at Law 538=1/2 N. Farish Street

) P, OO. Drawer 250

(OYE ry A cx Pel nk be 4 J ) z ‘ " A A FINE (POR. (AR. ~~ ~

wAllLOLL Misslesi Ppl 390460 JdC Kson, Mlisslssil PPL 39202

10 Columbus Circle su ite 2030

New York s New York 10019

This the /)4 Any of Awngust, 1970.

DANIEL FF. RINZWKL

Attorney

Nenartment of Theatre