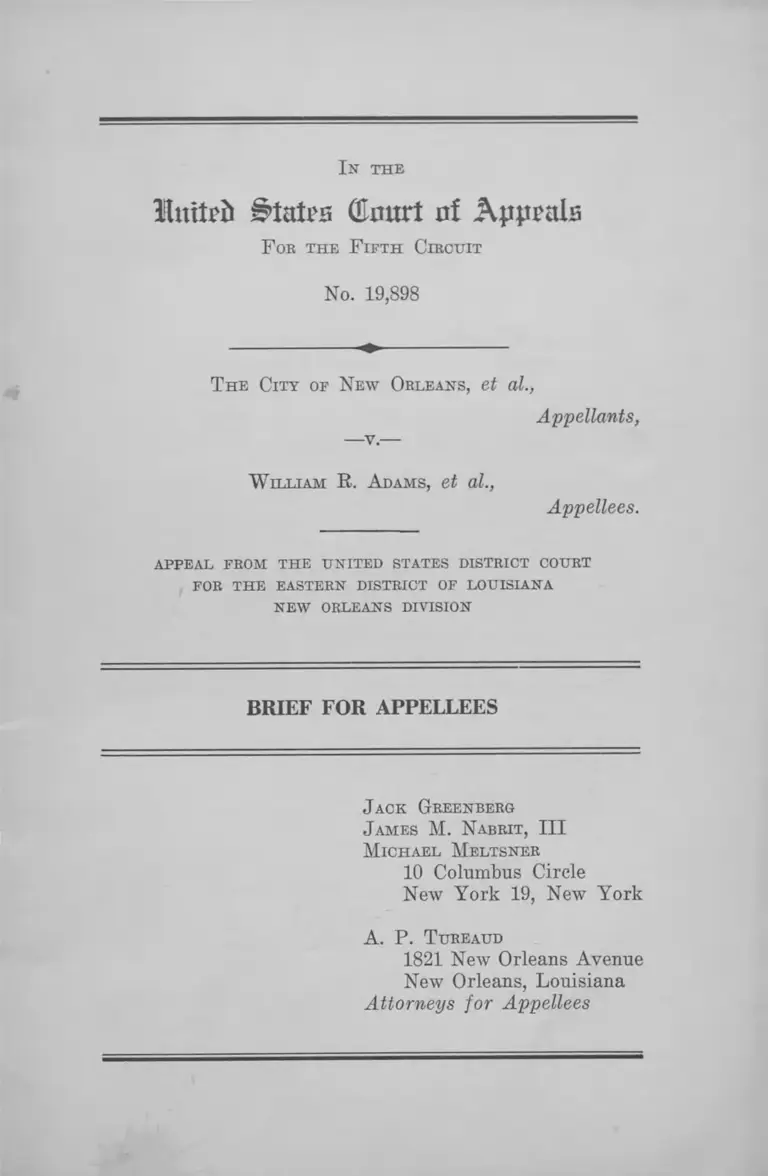

City of New Orleans v. Adams Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of New Orleans v. Adams Brief for Appellees, 1958. 7244d364-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2983b1ea-3277-4b27-8987-4ac0535316bd/city-of-new-orleans-v-adams-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Mntteii States GInurt of Appals

F o r t h e F i f t h C i r c u i t

No. 19,898

T h e C i t y o f N e w O r l e a n s , et al.,

Appellants,

— v .—

W i l l i a m R. A d a m s , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

NEW ORLEANS DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M . N a b r i t , III

M i c h a e l M e l t s n e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

A. P. T u r e a u d

1821 New Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellees

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the C ase....................................................... 1

A r g u m e n t

The Fourteenth Amendment Prohibits the Lessee

of a Municipality, Operating Food and Beverage

Facilities Under an Exclusive Concession at a

City Owned Airport, From Refusing to Serve

Negroes ......................................................................... 5

C o n c l u s i o n ................................................................................................................ 1 0

T a b l e o f C a s e s

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958) ............. 5

Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss.

1961) vacated and remanded 369 U. S. 3 1 .................... 9

Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University v.

Wilson, 340 U. S. 909, affirming 92 F. Supp. 986

(E. D. La. 1956) ............................................................. 9

Brooks v. City of Tallahassee, 202 F. Supp. 56 (N. D.

Fla., 1961) ...................................... 5

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ................................................................................... 5,8,9

Casey v. Plummer, 353 U. S. 924, aff’g Derrington v.

Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956) ......................... 5

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir.

1957) ................................................................................. 5

City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830 (5th

Cir. 1956) 6

PAGE

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d

853 (6th Cir. 1956) ......................................................... 9

Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N. D. Ga.

1960) ................................................................................. 6

Department of Conservation and Development v. Tate,

231 F. 2d 615 (4th Cir. 1956) ........................................ 5

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956)

cert. den. sub nom. Casey v. Plummer, 353 U. S. 924 .. 5, 8

Gliioto v. Hampton, 9 L. ed 2d 170, aff’g Hampton v.

City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th Cir. 1962) .... 6

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th

Cir. 1962), cert. den. sub nom. Ghioto v. Hampton,

9 L. ed 2d 170................................................................. 6

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 284 F. 2d 631

(4th Cir. 1960) ............................................................... 9

MacDuffie v. Hot Shoppes, as yet unreported, No. 123-

62-M-CIV-DD (S. D. Fla., 1962) .................................. 6

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co., 235

U. S. 151 ........................................................................... 7

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association, 347

U. S. 971, vacating and remanding, 207 F. 2d 275

(6th Cir. 1953) ............................................................... 5

Nash v. Air Terminal Service, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D.

Va. 1949) ......................................................................... 9

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ....................... 5, 8

S t a t u t e s

Louisiana Revised Statutes, §§26:1, et seq..................... 7

Louisiana Revised Statutes, §§26:340, et seq................... 7

11

In the

llnxttb States (to rt of Appeals

F o r t h e F i f t h C ir c u i t

No. 19,898

T h e C i t y o f N e w O r l e a n s , et al.,

—v.—

Appellants,

W i l l i a m R. A d a m s , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

N EW ORLEANS DIVISION

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEES

WILLIAM R. ADAMS, HENRY E. BRADEN, III,

AND SAMUEL L. GANDY

Statement of the Case

Appellees do not controvert the Statement of the Case

set forth in the brief of appellants The City of New Orleans,

its Mayor, the Manager of the New Orleans International

Airport and the New Orleans Aviation Board and its

Chairman. Appellees submit, however, that additional facts

and circumstances properly should be brought to the at

tention of this Court.

The facts pertaining to the leasehold agreement entered

into by the City of New Orleans are admirably summarized

in the opinion of the district judge which is reported at

208 F. Supp. 427, 428 (E. D. La. 1962) (R. 167-172). There

2

is no dispute as to the facts in this case (R. 187, 188) and

the Court found that (R. 167):

“ In 1957, the City of New Orleans and the New

Orleans Aviation Board, an agency of the city charged

with the maintenance and operation of the Moisant

International AirjDort, undertook the construction of

a new administration and terminal building for the

airport, which was aided by a substantial loan from

an agency of the federal government. The land on

which the building was constructed and the building

itself were and are now owned and maintained by the

City and its Aviation Board. On September 30, 1957,

pursuant to an ordinance passed by the New Orleans

City Council, the City, after receiving public bids, en

tered into a lease agreement with a Delaware corpora

tion styled Interstate Company, and also known as

Interstate Hosts, Inc., whereby the latter received an

exclusive franchise to operate and maintain restaurant

concessions, bars and other facilities serving food and

beverages at the airport. The lease agreement pro

vided for rental payment to the City based on a per

centage of gross receipts from the operation of the

facilities, with a guaranteed minimum of $5,756,300.00

over a period of fourteen years. The City reserved

the right to review and correct deficiencies in the

quality and quantity of products served, and to re

duce prices if they were found to be not in accord

with those in effect at comparable restaurants and

cocktail lounges in the City of New Orleans. In addi

tion, the lease provides that Interstate discharge any

employee deemed undesirable by the Aviation Board.”

(See R. 28, 34, 35, 43, 44, 47, 48.)'

At the hearing held on appellees’ Motion for Preliminary

Injunction, the Manager of the food and beverag’e facili

3

ties admitted that at least fifty Negroes had been refused

service at the Airport restaurant and bars during the past

two years “ on the basis of race” (R. 192). The district

court found that “At present, Interstate Hosts operates

facilities at the airport known as the Snack Bar, the Coffee

Shop, Le Bar, the International Room, a restaurant, and

the Cocktail Lounge, which adjoins the International Room.

Only the Snack Bar and the Coffee Shop are operated on

a de-segregated basis, the others not being available to

members of the Negro race” (R. 168).

Appellees, three Negro citizens of the United States and

the State of Louisiana brought this action by filing a veri

fied complaint in the district court on May 23, 1960 (R.

113-118) which sought to enjoin the City of New Orleans,

the Interstate Company and their agents from “making

any distinction based upon race or color in regard to ser

vice at the Moisant International Airport” (R. 117). Each

of the appellees had been refused service at the facilities

operated by the Interstate Company (R. 115, 116). Ap

pellees’ action was later consolidated with a suit on behalf

of a similarly situated plaintiff seeking identical relief1

(R. 185, 7-16, 66).

On June 19, 1961, the City of New Orleans, its agents

and Interstate Hosts, Inc., filed their answers controverting

the allegations of the complaint pertaining to acts of racial

discrimination (R. 130, 131, 134). On June 30, 1961, ap

pellees moved for Summary Judgment (R. 137) which mo

tion was denied by the district court (R. 154) on the ground

that “ genuine issues as to material facts” remained to be

resolved. On March 30, 1962, appellees moved for a pre

liminary injunction (R. 155). A hearing was held on this

1 Tliomas P. Harris v. City of New Orleans, et al., Civil Action No. 10,047

in the Eastern District of Louisiana, New Orleans Division.

4

motion on April 11, 1962 (B. 183-198) at which testimony

was taken and the policy of racial discrimination in force

at the Airport food and beverage facilities was admitted

by the City of New Orleans, its agents and lessee (E. 187,

188, 190, 192).

On August 2, 1962, the District Court filed its opinion

(E. 167-172) holding that the “ authorities leave little doubt

that plaintiffs in the case before the Court are entitled to

injunctive relief as a matter of law” (E. 171). A pre

liminary injunction was entered by the Court on August

14, 1962 enjoining the City of New Orleans, its agents and

lessee the Interstate Company, from denying Negroes the

complete, full and unrestricted use of the food and beverage

service areas and facilities located at the New Orleans

International Airport (E. 173-174).

The City of New Orleans and its agents filed Notice of

Appeal on August 16, 1962 (E. 177). The lessee, the Inter

state Company, filed a Notice of Appeal, but to date has

filed no brief in this Court (E. 175). The Trial Court

and this Court denied applications for a stay of the pre

liminary injunction pending appeal.

5

ARGUMENT

The Fourteenth Amendment Prohibits the Lessee of

a Municipality, Operating Food and Beverage Facilities

Under an Exclusive Concession at a City Owned Airport,

From Refusing to Serve Negroes.

Despite a long and compelling line of authorities ex

plicitly holding that lessees of governmental bodies are

subject to the restraints of the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment against discrimination on the

basis of race, the City of New Orleans contends that the

District Court erred in enjoining the admitted denial of

admission to Negroes at leased food and beverage facili

ties at the publicly owned New Orleans International Air

port. But the cases do not support the City’s position. In

fact, it may be said without exaggeration that the consti

tutional status of a lessee paying substantial rent for the

use of publicly owned property and providing a service

beneficial to the public is closed as a litigable issue.

The lessees of government may not make distinctions on

the basis of race. See Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S.

350 (airport restaurant); Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U. S. 715 (restaurant in parking garage);

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association, 347 U. S.

971, vacating and remanding, 207 F. 2d 275 (6th Cir. 1953)

(theatre in city park); Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d

922 (5th Cir. 1956) cert. den. sub nom. Casey v. Plummer,

353 U. S. 924 (courthouse restaurant); City of Greensboro

v. Simkins, 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir. 1957) (golf course);

Department of Conservation and Development v. Tate, 231

F. 2d 615 (4th Cir. 1956) (parks); Aaron v. Cooper, 261

F. 2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958) (leased school); Brooks v. City

of Tallahassee, 202 F. Supp. 56 (N. D. Florida 1961) (air

6

port restaurant); Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579

(N. D. Ga. 1960) (airport restaurant); MacDuffie v. Hot

Shoppes, as yet unreported, No. 123-62-M-CIV-DD (S. D.

Fla., 1962) (turnpike restaurant). Cf. Hampton v. City of

Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th Cir. 1962) cert. den. sub

nom. Gliioto v. Hampton, 9 L. ed 2d 170 (golf course sold;

city retained reversionary interest. Held: vendees sub

ject to constitutional restraints against discrimination on

the basis of race).

Faced with these authorities the City attempts to dis

tinguish the food and beverage facilities at the NeAV Orleans

International Airport on the grounds that: (a) the leased

restaurant is a “ luxury facility” ; (b) alcoholic beverages

are served at the facilities; and (c) the leased property is

surplus (Brief of Appellants, p. 4). Each of these at

tempted distinctions is frivolous.

There is no suggestion in the cases and indeed the City

does not present authority in support of the proposition

that the Fourteenth Amendment differentiates between

public facilities on the basis of the quality of service pro

vided.2 If economic loss is no defense to racial segrega

tion, City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830, 832

(5th Cir. 1956), the assertion that elaborate service ex

cuses compliance with the Constitution is plainly frivolous.

The claim that “ luxury facilities” are immune from the

restraints of the Constitution against discrimination on

the basis of race is analogous to the argument that distinc

tions based on race should be permitted because only a

few Negroes will exercise their constitutional rights, but

the United States Supreme Court long ago rejected such

2 The lessee’s manager testified that the food in the segregated Inter

national Room was no better than the food served in the desegregated Coffee

Shop. It is just that in the International Room there is “more elaborate

service” and higher prices (R. 190, 191).

7

a defense on the ground that it “ makes the constitutional

right depend upon the number of persons who may be dis

criminated against whereas the essence of the constitu

tional right is that it is a personal one” , McCabe v.

Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151, 161.

Appellants’ contention that the public has not “ con

structed space in a public building so that persons having

occasion to go to that building can enjoy an alcoholic

stimulant while there” (Brief for Appellants, p. 7) borders

on the unreal. It need only be pointed out that the Terms

and Conditions for the Restaurant Concession prepared by

the New Orleans Aviation Board and agreed to by the

lessee provide for the sale of alcoholic beverages (R. 34,

35, 46) and that the City has contracted to receive 12%

“ on gross sales derived each month from all liquor, wine,

beer and ale, including cordials” (R. 47).3

The claim that the leased food and beverage facilities

at the New Orleans International Airport are operated on

“ surplus property” is contradicted by the City’s own repre

sentations in the lease that “ In entering into this restaurant

concession in the new terminal building at the Moisant

International Airport, the Board has foremost in mind

providing the public and the air traveler with restaurant

facilities, service and beverages of high quality commen

surate with the trade that is accustomed to using modern

facilities of this land” (R. 46).

N̂o court ever has held that leased property was “ surplus”

and thereby immune from the requirements of the Four

teenth Amendment, notwithstanding the suggestion in

3 The State has a substantial financial interest in the taxes from every

gallon of liquor sold in Louisiana ({§26 :340 et seq., Louisiana Revised Stat

utes), and the State is intimately involved in regulation of the sale and

manufacture of alcoholic beverages ({ {2 6 :1 et seq., Louisiana Revised Stat

utes).

8

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922, 925 (5th Cir. 1956).

Indeed, the restaurant in the Derrington case was held to

be non-surplus because used for a public purpose, i.e., it

was located in a building built with public funds for the

use of the citizens generally and the express purpose of

the lease was to furnish food service for the persons having

business in the building. Identical facts are present in

the instant case. Moreover, in this case, the claim that

the property leased is surplus is patently frivolous in light

of the undisputed admission that the asserted “ surplus

property” produces for the City a guaranteed minimum

rental of over five million dollars over a 14 year period

and that the City’s rent is computed on the basis of a

percentage of gross sales. The concession area, as clearly

revealed from the lease, is a financially and physically in

tegral part of the Airport operated by the City. Burton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 724.

Appellants’ claim that the holdings of the Burton case

and of Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350, do not control the

present case is untenable.4 All the factors found sufficient

to bring the leased premises in those cases within the

purview of the Fourtenth Amendment are present here.

The leased premises are publicly owned and are located

within and form an integral part of a building maintained

and operated by governmental agents for the use of the

public under a lease and concession arrangement with ob

vious benefits, financial and otherwise, to governmental

agencies. Indeed, here, as in Burton, the existence of segre

gated and nonsegregated facilities beneath the same mu

nicipal roof accents the irrationality of the practice now

4 It should be noted that the average annual minimum rent paid to the

City of New Orleans under the lease is over ten times greater than the rent

payed by the restaurant to the Municipal Parking Authority in Burton. See

365 U. S. at 720.

9

scrutinized by this Court. The Court in Burton, 365 U. S.

at 724, characterized such a situation as “ irony amounting

to grave injustice.”

The facts in this case are undisputed, the law to be ap

plied is clear, irreparable injury is established by evidence

of a clear and continued deprivation of constitutional

rights.5 In such circumstances a “ District Court has no

discretion to deny relief by preliminary injunction to a

person who clearly establishes by undisputed evidence that

he is being denied a constitutional right”, Henry v. Green

ville Airport, 284 F. 2d 631, 633 (4th Cir. 1960). See Judge

Rives’ dissenting in Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595,

622 (S. D. Miss. 1961) vacated and remanded, 369 U. S. 31

(“ The defendants should not be allowed to rely upon their

own continued unconstitutional behavior for the purposes

of defeating a motion for preliminary injunction” ) ;

Clemons v. Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853, 857 (6th

Cir. 1956); Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State Uni

versity v. Wilson, 340 U. S. 909, affirming 92 F. Supp. 986

(E. D. La. 1956).

The holding of the District Court that there is “ little

doubt that plaintiffs in the case before this Court are en

titled to injunctive relief as a matter of law” (R. 171) is

amply supported by the facts and applicable precedents

and should be affirmed.

5 Appellees would be entitled to relief even if the “separate-but-equal”

doctrine were an acceptable Constitutional standard, for the only “luxury” res

taurant and the only bars in the airport are segregated (E. 190, 191). See

Nash v. Air Terminal Service, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D. Va. 1949).

10

CONCLUSION

W h e r e f o r e , for the foregoing reasons, appellees pray

this Court affirm the judgment of the Court below.

Respectfully submitted,

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M . N a b r i t , I I I

M i c h a e l M e l t s n e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, NeAV York

A. P. T u r e a tjd

1821 New Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellees

3 8