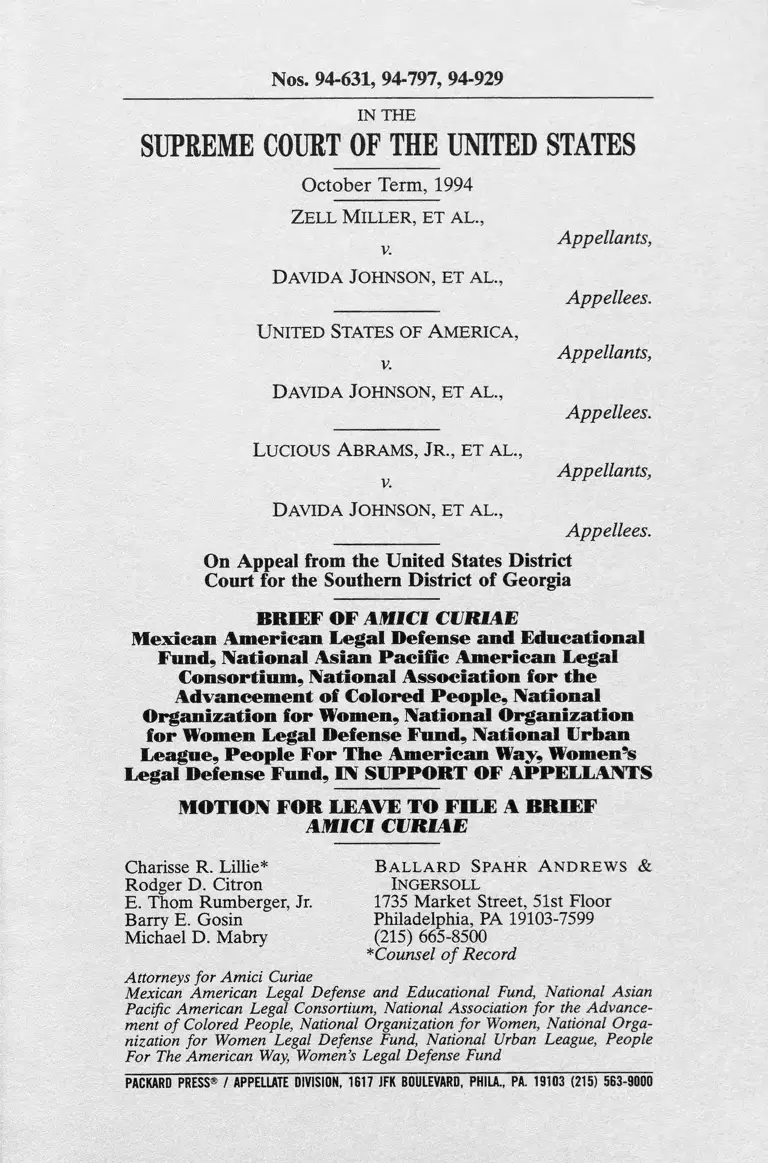

Miller v. Johnson Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miller v. Johnson Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae, 1994. 2c020ab2-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/29aab7a7-9761-48d7-b9a2-8bb0c08a0b24/miller-v-johnson-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 94-631, 94-797, 94-929

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1994

Zell Miller, et al.,

Appellants,

Davida Johnson, et al.,

Appellees.

United States of America,

v Appellants,

Davida Johnson, et al.,

Appellees.

Lucious Abrams, Jr., et al.,

Appellants,

Davida Johnson, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Georgia

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

M exican A m erican L ega l D efen se an d E d u ca tio n a l

F und, N a tio n a l A sian P a c ific A m erican L ega l

C on sortiu m , N a tio n a l A sso c ia tio n fo r th e

A d van cem en t o f C olored P e o p le , N a tion a l

O rg a n iza tio n fo r W om en, N a tio n a l O rg a n iza tio n

fo r W om en L egal D efen se F u n d , N a tio n a l U rban

L eagu e, P e o p le F or T h e A m erican W ay, W om en’s

L egal D efen se F und , IN SUPPO RT OF APPELLANTS

M OTION FO R LEAVE TO FILE A B R IE F

AM ICI CURIAE

Charisse R. Lillie*

Rodger D. Citron

E. Thom Rumberger, Jr.

Barry E. Gosin

Michael D. Mabry'

Ballard Spahr A ndrew s &

INGERSOLL

1735 Market Street, 51st Floor

Philadelphia, PA 19103-7599

(215) 665-8500

*Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, National Asian

Pacific American Legal Consortium, National Association for the Advance

ment o f Colored People, National Organization for Women, National Orga

nization for Women Legal Defense Fund, National Urban League, People

For The American Way, Women’s Legal Defense Fund

PACKARD PRESS® / APPELLATE DIVISION, 16 17 JFK BOULEVARD, PHILA., PA. 19103 (215) 563-9000

Of Counsel:

Anthony Chavez

Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90014

213-629-8016

Margaret Fung

Karen Narasaki

National Asian Pacific American Legal Consortium

1629 K Street, NW

Washington, D.C. 20006

202-296-2300

Wade Henderson

Dennis Courtland Hayes

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

4805 Mt. Hope Drive

Baltimore, MD 21215

202-667-1700

410-358-8900

Kim Gandy

National Organization for Women

1000 16th Street, NW

Washington, D.C. 20036

Deborah Ellis

National Organization for Women Legal Defense and

Education Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

212-925-6635

Rodney G. Gregory

National Urban League

500 East 62nd Street

New York, NY 10021

212-310-9000

Elliot Mincberg

People For The American Way

200 M Street, NW

Washington, D.C. 20036

202-467-4999

Donna R. Lenhoff

Women’s Legal Defense Fund

1875 Connecticut Avenue, NW

Washington, D.C. 20009

202-986-2600

Nos. 94-631, 94-797, 94-929

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1994

Z e l l M il l e r , e t a l .,

Appellants,

D a v id a Jo h n so n , e t a l .,

Appellees.

U n it e d States o f Am e r ic a ,

Appellants,

D a v id a J o h n so n , e t a l .,

Appellees.

Lucious A b r a m s , J r ., e t a l .,

Appellants,

D a v id a J o h n so n , e t a l ..

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Georgia

M OTION FO R LEAVE TO FILE A B R IE F

AM ICI CURIAE

2

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF

AMICI CURIAE

Pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 37, the Mexican Ameri

can Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the National Asian

Pacific American Legal Consortium, the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People, the National Orga

nization for Women, the National Organization for Women

Legal Defense Fund, the National Urban League, People For

The American Way and Women’s Legal Defense Fund,

respectfully move the Court for leave to file the attached brief

as amici curiae in support of the appellants. The appellants

have consented to the filing of this brief. Appellees have

refused to grant consent.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund (“MALDEF”) is a nonprofit, national civil rights orga

nization headquartered in Los Angeles. Its principal objective

is to secure, through litigation and education, the civil rights of

Hispanics living in the United States. Because of the impor

tance of the fundamental right to vote, MALDEF has repre

sented Hispanic voters in numerous voting rights cases, includ

ing City o f Lockhart v. United States, 460 U.S. 125 (1983),

Garza v. County o f Los Angeles, 756 F. Supp. 1298 (C.D. Cal.),

a ff’d, 918 F.2d 763 (9th Cir. 1990), cert, denied, 498 U.S. 1028

(1991), and Hastert v. State Bd. o f Elections, 111 F. Supp. 634

(N.D. 111. 1991) (three-judge court).

The National Asian Pacific American Legal Consortium

(“NAPALC”) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization whose

mission is to advance the legal and civil rights of Asian and

Pacific Americans through a national collaborative structure

that pursues litigation, advocacy, education, and public policy

development. The NAPALC is composed of three organiza

tions based in major urban areas with significant Asian and

Pacific Islander populations: the Asian American Legal

Defense and Education Fund (New York), the Asian Law

Caucus, Inc. (San Francisco), and the Asian Pacific American

Legal Center of Southern California (Los Angeles). The

enforcement of the Voting Rights Act as a means for provid

ing Asian Pacific Americans with meaningful access to the

electoral process is one of NAPALC’s top priority programs.

3

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People (“NAACP”) is a private membership organiza

tion of 500,000 members nationwide. It is the nation’s oldest

and largest civil rights organization. The NAACP was active

in the effort to win passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

and the subsequent amendments enacted thereto. The

NAACP has frequently provided representation to minorities

in voting rights cases and has participated in litigation before

this Court, including NAACP v. Hampton County Election

Comm’n, 470 U.S. 166 (1985), and Statewide Reapportionment

Advisory Comm. v. Theodore, 113 S. Ct. 2954 (1993).

The National Organization for Women (“NOW”) is the

nation’s largest feminist organization devoted to the advance

ment of women’s rights, with over 280,000 members and more

than 600 chapters in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

NOW has, since its inception, advocated the full and complete

political participation of all people, particularly women and

racial and ethnic minorities. Specifically, NOW and NOW’s

political action committee has a project called “Elect Women

For a Change,” that supports the election of women to public

office.

The NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund (“NOW

LDEF”) is a leading national non-profit civil rights organiza

tion that performs a broad range of legal and educational ser

vices in support of women’s efforts to secure equal rights and

to eliminate sex-based discrimination. NOW LDEF was

founded as an independent organization in 1970 by leaders of

the National Organization for Women. A major focus of

NOW LDEF’s work is to promote civil rights for women,

including equal electoral participation.

The National Urban League (“League”), founded in

1910, is the premier social service and civil rights organization

in A m erica. The League is a nonprofit, nonpartisan

community-based organization headquartered in New York

City, with 113 affiliates in 34 states and the District of Colum

bia. The mission of the League is to assist African Americans

in the achievement of social and economic equality. The

League implements its mission through advocacy, bridge

building, program services, and research.

4

People For The American Way (“People For”) is a non

partisan, education-oriented citizens organization established

to prom ote and protect civil and constitutional rights.

Founded in 1980 by a group of religious, civic and educational

leaders devoted to our Nation’s heritage of tolerance, plural

ism and liberty, People For now has over 300,000 members

nationwide. People For has been actively involved in efforts to

combat discrimination and its effects and to promote meaning

ful and effective voter participation by all citizens. These

efforts have included conducting nationally recognized voter

education and registration programs, participating in legisla

tive advocacy on these issues, and serving as counsel or as

amicus curiae in important cases before this Court and courts

across the country.

The Women’s Legal Defense Fund (“WLDF”), founded

in 1971, is a national advocacy organization working at federal

and state levels to promote policies that help women achieve

equal opportunity, quality health care, and economic security

for themselves and their families. WLDF has long advocated

broad application of the constitutional and statutory guaran

tees of civil rights under the law.

All of these organizations advocate on behalf of voters

who are concerned with maintaining complete openness and

diversity in the electoral process. The issue of how congres

sional boundaries are drawn affects them and their constituen

cies of minorities and women, and voters around the country.

The resolution of the issues in this case will have an

impact on the interests of women and minority voters gener

ally as well as on the particular parties before the Court. This

amicus brief focuses on the issues before the Court in light of

the historical development and expansion of the constitutional

right to vote. Amici thus offer a broader perspective regarding

the potential impact and importance of this case, as well as a

more expansive analysis of the public policy issues in question,

than that which is likely to be provided by the particular par

ties to this case. This brief therefore presents arguments that

complement rather than duplicate those of the appellants.

Amici represent several broad-based constituencies who

will be directly affected by the decision herein. Amici also

5

offer arguments and analysis complementary to the briefs filed

by Appellants. Amici therefore respectfully request that the

motion be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Charisse R. Lillie*

B a l l a r d Spa h r A n d r e w s &

INGERSOLL

1735 Market Street, 51st Floor

Philadelphia, PA 19103-7599

(215) 665-8500

* Counsel of Record

for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................................. ii

INTEREST OF A M IC I ........................................................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT........ ................... 2

ARGUMENT .......................................................................... 5

INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 5

I. Amendments to the Constitution Have Resulted

in an Increasingly Diverse and Representative

Electorate ........................ .............. ................... . • 6

II. The Voting Rights Act and its Amendments

Demonstrate the Commitment of Congress to

Enforcing the Constitutional Guarantee of

Equal Political Opportunity.................................... 13

III. The History of Voting Rights Litigation in the

Supreme Court Shows the Court’s Commitment

to Expanding the Right to V o te ............................ 24

CONCLUSION ................................................... 29

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Allen v. State Board o f Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969) . 23, 24

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962)..................................... 9, 26

Breedlove v. Suttle, 302 U.S. 277 (1937)......................... .. 12

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).......... 2

Cady v. State, 31 S.E. 2d 38 (Ga.), cert, denied, 323 U.S.

676 (1944)...................................................................... 12

Castro v. State o f California, 466 P.2d 244 (Cal. 1970) . . . 19

Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380 (1991)............................. 24

City o f Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) . . . . . . . . . 22, 23

Clark v. Roemer, 500 U.S. 646 (1991).............................. 24

Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433 (1965) .............................. 23

Garza v. County o f Los Angeles, 756 F. Supp. 1298 (C.D.

Cal.), a ff’d, 918 F.2d 763 (9th Cir. 1990), cert, denied,

498 U.S. 1028 (1991).......................................... 18,19, 20

Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973)................... 23

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)..................... 9, 26

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927) .............................. 10

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963)......................... 9, 26, 27

Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S. 1215 (1 9 7 1 ) ...... 20

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) ...................... 25

Harper v. Virginia Board o f Elections, 383 U.S. 663

(1966)............................................................................. 2, 28

Hawthorne v. Turkey Creek School District, 134 S.E. 103

(Ga. 1926)..................................................................... 12

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943).............. 21

Houston Lawyers’ Association v. Attorney General, 501

U.S. 419 (1991)........................................ .......... .. 24

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

Cases: Page

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S. Ct. 2647 (1994)................... 24

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)......... 21

League o f United Latin American Citizens v. Midland

Independent School District, 812 F.2d 1494 (5th Cir.),

vacated on other grounds en banc, 829 F.2d 546 (5th

Cir. 1 9 8 7 ) . . . . . ............. 18

Louisiana v. Hayes, No. 94-627 (probable jurisdiction

noted and appeal pending)............... 4

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)............................ .. 10

Naim v. Naim, 87 S.E.2d 749 (Va.), vacated, 350 U.S. 891

(1955)............... 10

NAACP v. Hampton County Elections Commission, 470

U.S. 166 (1985)........................... 23

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970)......................... 28, 29

Pleasant Grove v. United States, 479 U.S. 462 (1987) . . . . 24

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)............................... 10

Powers v. State, 157 S.E. 195 (Ga. 1931)........................... 12

Prewitt v. Wilson, 46 S.W.2d 90 (Ky. Ct. App. 1 9 3 2 )..... 14

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964)................ 9, 13, 28

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S. Ct. 2816 (1993)...........................passim

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944)......................... 25, 26

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966).... 14, 15

Stephens v. Ball Ground School District, 113 S.E. 85 (Ga.

1922).............................................................................. 12

Takao Ozawa v. United States, 260 U.S. 173 (192 2 )...... 21

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953)................................. 26

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) ...................... 23, 24

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

Cases: Page

United States v. Hayes, No. 94-558 (probable jurisdiction

noted and appeal pending)......................................... 4

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964).................. 3, 7, 27, 28

Westminster School District v. Mendez, 161 F.2d 774 (9th

Cir. 1947)........................................................................ 10

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)............................... 16

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1896)......................... 2

Constitution and Statutes:

United States Constitution:

Article 1.......................................................................... 7

Thirteenth Amendment............................................... 8

Fourteenth Amendment........................................... passim

Fifteenth Amendment............................. 9, 10, 11, 13, 25

Seventeenth Amendment................. 11

Nineteenth Amendment........................................... 11, 12

Twenty-Fourth Amendment ........................................ 12

Twenty-Sixth Amendment ............................. 12, 13

Statutes:

National Voter Registration Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-

31, 107 Stat. 77 (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1973gg-l et

seq. (1994))...................................................................... 13

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, 79

Stat. 437 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973

et seq. (1994))..................................... passim

The Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1970, Pub. L. No.

91-285, 84 Stat. 314 (codified as amended at 42

U.S.C. §§ 1973 to 1973bb-l (1994))........................... 15

Statutes: Page

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 Amendments, Pub. L. No.

94-73, 89 Stat. 400 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1973 to 1973bb-l (1994)) .................. ................ passim

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, § 3, Pub. L. No.

97-205, 96 Stat. 131, 134 (codified as amended at 42

U.S.C. § 1973(a) (1994))............................... ............... 22

Voting Rights Act Amendment of 1992, § 2, Pub. L. No.

102-344, 106 Stat. 921 (codified as amended at 42

U.S.C. § 1973aa-la) (1994)) ......................... 22

Miscellaneous:

George Anastaplo, Amendments to the Constitution o f

the United States: A Commentary, 23 Loy. U. Chi.

L.J. 631 (1992) ........................................................... 8, 13

Karen McGill Arrington, The Struggle to Gain the Right

to Vote: 1787-1965, in Voting Rights in America:

Continuing the Quest for Full Participation 34

(Karen McGill Arrington & William L. Taylor eds.,

1992)......... 21

Chandler Davidson, The Voting Rights Act: A Brief His

tory, in Controversies in Minority Voting 7 (Bernard

Grofman & R. Chandler Davidson eds., 1992)........ 7, 8

Lani Guinier, The Triumph o f Tokenism: The Voting

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

Rights Act and the Theory o f Black Electoral Success,

89 Mich. L. Rev. 1077 (1991)....................... ............. .. 6

Eugene Rostow, The Japanese-American Cases — A

Disaster, 54 Yale L.J. 489 (1945)................................. 21

The Voting Rights Act Extension, H. Rep. No. 196, 94th

Cong., 1st Sess. 16, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 24 1975 . . .

17, 18, 20

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 Extension, S. Rep. No.

295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 24 (1975), reprinted in 1975

U.S.C.C.A.N. 790 ...... ................................. 17, 18, 20, 21

v

Miscellaneous: Page

Kris W. Kobach, Rethinking Article V: Term Limits and

the Seventeenth and Nineteenth Amendments, 103

Yale L.J. 1971 (1994).................................................... 11

J. Morgan Kousser, The Voting Rights Act and the Two

Reconstructions, in Controversies in Minority Voting

135 (Bernard Grofman & R. Chandler Davidson

eds., 1992)................................................................... 10

Steven F. Lawson, Black Ballots: Voting Rights in the

South, 1944-1969 (1976)................................................. 14

The Southwest Voter Registration Education Project,

Legacy: 1974-1990.......................................................... 20

National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed

Officials Education Fund — 1993 National Roster of

Hispanic Elected Officials (1993)........................... 19, 20

The Voting Rights Act Language Assistance Amendments

o f 1992, S. Rep. No. 315, 102d Cong., 2d Sess.

(1992).................................................. 21

Amendments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965: Hearings

Before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights

of the Committee on the Judiciary, 91st Cong., 2d

Sess. (1970)................................................................ 15, 16

U.S. Civil Rights Commission, Civil Rights Issues Facing

Asian Americans in the 1990s (1992)........................ 21

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights Act:

Unfulfilled Goals (1981)............................................... 17

United States Senate, Subcommittee on Constitutional

Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary, Extension

of Voting Rights Act of 1965: Hearings on S. 407,

S. 903, S. 1509 and S. 1443, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1975).............................................................................. 17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

Miscellaneous: Page

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, S. Rep. No.

417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in, 1982

U.S.C.C.A.N. I l l (1982).................................... 22, 23

White House Press Release (June 29, 1 9 9 2 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Vll

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1994

Z e l l M il l e r , e t a l .,

Appellants,

D a v id a J o h n so n , e t a l .,

Appellees.

U n it e d States o f A m e r ic a ,

Appellants,

D a v id a J o h n so n , e t a l .,

Appellees.

Lucious A b r a m s , J r ., e t a l .,

Appellants,

D a v id a Jo h n so n , e t a l .,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Georgia

B R IE F OF AM ICI CURIAE

IN SU P P O R T OF A PPELLA N TS

M OTION FO R LEAVE TO FILE A B R IE F

AM ICI CEBIAE

INTEREST OF AMICI

Amici, Mexican American Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, National Asian Pacific American Legal Consor

tium, National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, National Organization for Women, National Organi

zation for Women Legal Defense Fund, National Urban

League, People for the American Way and Women’s Legal

Defense Fund have extensive experience in advocacy on vot

ing rights issues and/or in voting rights litigation, and share the

goal of preventing any retrenchment by the Courts and Con-

1

2

gress of statutes and decisional law which have expanded the

right to vote and resulted in the creation of a more inclusive

democracy.1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Since Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954),

the country has made steady progress in eliminating the

effects of its unfortunate history of segregation and discrimi

nation against African Americans. As a result of the enact

ment and enforcement of the Voting Rights Act of 19652 and

the amendments to the statute, the longstanding exclusion of

minority groups from a voice in governance has begun to

change. In the last decade, the perception of the United States

as a country governed only by whites (or Anglos) has begun

to change. This change in the perception and the reality has

provided an avenue of hope for Americans of all colors and

backgrounds, and has fostered a sense of inclusion and partici

pation that for so long was nonexistent.

The steady progress which this country has made in

expanding the franchise is threatened by the litigation result

ing from this Court’s decision in Shaw v. Reno, 113 S. Ct. 2816

(1993). Through its history our nation has demonstrated an

interest in expanding the franchise and fostering participation

by different parts of society. The decisions of the courts below

and other cases signal a retrenchment which should be

avoided. Amici urge this Court, when ruling on the merits of

these appeals, to consider this case in its historical and legal

context.

The Supreme Court has recognized that “the political

franchise of voting is a ‘fundamental political right, because [it

is] preservative of all rights.’ ” Harper v. Virginia Bd. o f Elec

tions, 383 U.S. 663, 667 (1966); see also Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356, 370 (1896) (recognizing that the right to vote “is

preservative of all rights”). Nevertheless, for many years after

1. Each organization is described fully in the preceding Motion for

Leave to File, which is incorporated by reference herein.

2. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437

(codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973 et seq. (1994)).

3

the founding of this nation, the fundamental right to vote was

denied to all except white male property owners.

The nation continues to make its gradual advance toward

the achievement of a universal right to suffrage for all adult

citizens of the United States, without regard to wealth, race,

previous condition of servitude, color, gender, national origin,

language minority status, or age. As a result, the “fundamen

tal political right” to vote is no longer the province of a small

minority of the citizenry. Rather, it is a right enjoyed and cher

ished by millions of Americans whose lives are affected by the

decisions made by their elected representatives.

Amici are committed to ensuring that the right to vote

and to participate equally in the electoral process receive this

Court’s most esteemed recognition, fervent protection and

reaffirmation. These appeals, which arise from a decision

invalidating one of the districts of the post-1990 Census con

gressional redistricting plan for the state of Georgia (the Elev

enth Congressional District, currently represented by Con

gresswoman Cynthia McKinney), present issues of great

concern to Amici and their members and constituents, all of

whom are concerned with ensuring that constitutional and

statutory provisions prohibiting race-, gender-, wealth-,

English literacy- and age-based restrictions upon the right to

vote are fully enforced.

Amici believe that the right to equal participation in the

election of members of the United States Congress is among

the most cherished rights of citizens of the United States. Jus

tice Hugo Black wrote that the “Constitution’s plain objective

of making equal representation for equal numbers of people

[was] the fundamental goal for the House of Representatives

. . . [and] the high standard of justice and common sense which

the Founders set for us.” Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1, 18

(1964).

Constitutional amendments and congressional enactments

since the Civil War have expanded the right of suffrage, con

sistent with this “plain objective” of the United States Consti

tution. Racial, ethnic and language minorities and women in

America continue to suffer discrimination in employment,

housing and other circumstances, despite the progress which

4

has been made. Amendments to the Constitution, coupled

with federal legislation, have been instrumental to the efforts

to remedy the effects of discrimination against minorities and

women.

The vitality of both the constitutional amendments

extending the franchise, as well as the body of laws enacted by

Congress to enforce these amendments, are at issue in the

appeals now before the Court. Amici join the Appellants in

urging the Court to reverse the decision below, which seriously

conflicts with the fundamental message of the numerous deci

sions of this Court recognizing the importance of the right to

vote. These decisions, acknowledging the damaging and per

sistent effects of the varied means of disenfranchising large

segments of the citizenry of the United States, and remedying

the impact of decades of exclusion from the political process

that is the legacy of many members of the modern electorate,

should not be disturbed.

Our society and the federal courts, including the United

States Supreme Court, have struggled in this era with the

appropriate limits on explicit consideration of race, national

origin and sex. It is important to recognize that congressional

enactments such as the Voting Rights Act represent a signifi

cant and proper balancing of the interests and concerns at

stake.

Amici urge the Court to maintain that balance and to

reject the unwarranted expansion and misreading of Shaw that

has spawned these appeals, and similar lawsuits,3 against post-

1990 Congressional and state legislative districts. It would be

a national tragedy if Shaw was interpreted and followed with

finality in such a manner that it would adversely and unneces

sarily cause a sudden and drastic reduction of African Ameri

can and other minority citizens’ political participation and rep

resentation at this critical time in this still-evolving history of

our democracy. This country’s commitment to democracy, plu

3. See, e.g., United States v. Hays, No. 94-558 (prob. jur. noted and

appeal pending); Louisiana v. Hays, No. 94-627 (prob. jur. noted and appeal

pending).

5

ralism and diversity, which insures and safeguards the rights of

all of our citizens to equal participation in our electoral pro

cess, requires no less.

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

Appellees are a group of black and white registered vot

ers and residents of Georgia’s Eleventh Congressional District

who have successfully challenged Georgia’s 1990 congressional

redistricting on constitutional grounds. Appellees alleged in

their complaint that the configuration of the Eleventh Con

gressional District amounted to unconstitutional racial gerry

mandering in violation of Shaw.

A majority of the district court held that Georgia’s Elev

enth Congressional District violated the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and permanently

enjoined further elections in the district. Amici urge this Court

to review constitutional history, the legislative history of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 (the “Act”) and the case law inter

preting the Act as it considers the questions presented in these

appeals. Shaw acknowledges that race-conscious redistricting

may violate the rights of white citizens under some circum

stances. But Shaw does not require the result reached in the

court below. Amici urge reversal of the decision below. Con

stitutional history, legislative history of the Act and its amend

ments, and the case law interpreting the Act reveal an overall

benefit to all citizens — both whites and members of minority

groups — when expansions of the right to vote are under

taken. The actions of the State of Georgia and the United

States Attorney General are legal and constitutional, and the

Eleventh Congressional District should be preserved.

Appellees below have failed to prove any harm suffered

by them. They have also failed to prove that Georgia’s Elev

enth Congressional District is so bizarre or irrational on its

face that the only conclusion that could be reached by the

Court is that it was created solely on the basis of race. Amici

urge the Court to resist this attempt to expand the reach of

Shaw. Some gradual progress has been made in opening up

6

the American political system to minorities and women. Any

retraction of this progress will have a deleterious effect on the

political process and the political landscape.

The central underpinning of a free and democratic system

of government is the right to vote. The struggle to guarantee

that every citizen has an equal voice in government has long

commanded the attention and the emotions of this Nation.

The expansion of the right to vote is a sign of — and ensures

the promotion of — the vitality of democracy in the United

States. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., once said:

Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry

the federal government about our basic rights.. . . Give us

the ballot and we will fill our legislative halls with men of

good will. . . . Give us the ballot and we will help bring

this nation to a new society based on justice and dedica

tion to peace.4

In his remarks, Dr. King asserted that the protection, availabil

ity and opportunity to use the franchise guarantees the integ

rity of the political process and strengthens the society served

by that process.

Efforts to ensure that the right to vote is one available to

all have been accomplished on several different levels.

Through constitutional amendments, through legislative

enactments and through the courts, our system has continually

protected and broadened this fundamental right.

I. AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION HAVE

RESULTED IN AN INCREASINGLY DIVERSE AND

REPRESENTATIVE ELECTORATE

The nation’s interest in promoting participation in the

political process is evident in the expanding protections of the

right to vote in our Constitution. In its original form, the Con

stitution recognized this right. Several amendments to it have

expanded this right to all persons: first to African Americans,

4. Quoted in Lani Guinier, The Triumph o f Tokenism: The Voting

Rights Act and the Theory o f Black Electoral Success, 89 Mich. L. Rev. 1077,

1082 n.14 (1991).

7

next to women, and later to those between the ages of 18 and

21. The Constitution and its amendments demonstrate the

vital national interest in promoting the participation and

involvement of all segments of our population in the electoral

process.

A rticle I, Section 2 of the Constitution provides that

m em bers of the U nited States H ouse of Representatives

shall be chosen “by the People of the several States” and

shall “be apportioned am ong the several S tates . . .

according to their respective N um bers.” U.S. Const, art.

I, § 2. In his m ajority opinion in Wesberry v. Sanders, 376

U.S. 1, Justice Black reviewed the debate among the del

egates of the Constitutional Convention over whether

election should be by the people. According to Justice

Black, “ [o]ne principle was upperm ost in the minds of

m any delegates: that . . . ‘equal num bers of people ought

to have an equal num ber of representatives. . . . ’ ” Id. at

10-11 (citation omitted).

African Americans were regarded as property for

taxation purposes, and as such, were not allowed to share

in having this equal voice, this im m utable right. The

drafters of the Constitution, in fact, agreed that each

slave would be counted as three-fifths of a free person.

For the first two hundred and fifty years after America

was colonized, most African Americans were enslaved

and unable to vote. No woman of any color, race or

national origin could vote. By the eve of the Civil War,

A frican Americans, w hether “free” or not, were denied

the suffrage in m ost States.5

Nevertheless, what can only be described as a deep-

rooted drive for equality in this country persisted. The

Constitution had recognized and embodied the “ancient

‘right of the people to participate in their legislative

5. African Americans were denied the franchise everywhere except

New York and the New England states (excluding Connecticut where they

were denied the right to vote). Moreover, in New York, African Americans,

but not whites, were required to have $250 worth of property to vote. Chan

dler Davidson, The Voting Rights Act: A Brief History, in Controversies in

Minority Voting 7 (Bernard Grofman & Chandler Davidson eds., 1992).

8

council.’” This, in turn, had been recognized as deriving

from “the immutable laws of nature, the principles of the

English constitution, and the several charters or com

pacts” in the Declaration and Resolves of the First Con

tinental Congress of October 14, 1774.6 In several of the

amendments that followed, the m ovem ent toward univer

sal suffrage, a natural extension of the idea of equality,

would be advanced. Gradually the right to vote was

extended beyond educated, wealthy, white, male citizens

who owned property.

The right of universal suffrage rose to the forefront

of the American political agenda during the Civil War,

and thereafter. The enactm ent of various amendments

enlarging the reach of the franchise reflected this coun

try ’s com m itm ent to its original prom ise of equality

under law for all its citizens regardless of race, color or

heritage.

The Thirteenth Am endm ent formally abolished the

institution of slavery. U.S. Const, am end. X III. This

am endm ent began the process of curing the single great

est failure of the C onstitu tion of 1787, assuring all

Americans, including African Americans, a semblance of

citizenship.

The drafters of the Fourteenth A m endm ent in Sec

tion 2 addressed the issue of the right of suffrage by

penalizing States that deny voting rights.7 In Section 1,

although not explicitly mentioning race, all citizens are

guaranteed their ‘privileges and im m unities’, in addition

to the equal protection and due process of the laws.

Minorities were now provided with a sword with which

they would battle the historical vestiges of discrimina

tion. The battle, however, was yet to come.8

6. See George Anastaplo, Amendments to the Constitution o f the United

States: A Commentary, 23 Loy. U. Chi. L.J. 631, 833 (1992).

7. U.S. Const, amend. XIV, § 2. It is no secret that this part of the

Amendment was overlooked as the franchise for African Americans was

eroded some years later. Davidson, supra note 4, at 9.

8. With respect to right of suffrage, the Fourteenth Amendment did not

serve as a source of authority until the early vote dilution cases. See, e.g.,

9

The Fifteenth Am endm ent was enacted by Congress

in 1870, less than a year after ratification of the Four

teenth Am endm ent and was directed tow ard the im m e

diate goal of securing and protecting m inority voting

rights. It provided, “The right of citizens of the U nited

States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the

United States or by any State on account of race, color

or previous condition of servitude. The Congress shall

have the power to enforce this by appropriate legisla

tion.” U.S. Const, amend. XV. Despite the clear language

of this provision, contrivances by southern States, along

with often violent white southern resistance to African

American suffrage, created the need for further congres

sional action to fully enforce its guarantees.9

Congress made repeated attem pts to p ro tect the

right of suffrage of African Americans, principally in the

Military Reconstruction Acts, the various enforcem ent

acts, Ku Klux Klan acts (to execute the dictates of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth A m endm ents) and the 1875

Civil R ights Act. B ut w hite sou thern in transigence

proved to be a powerful force. African Am erican politi

cal power, albeit in its nascency, was suffocated by a vari

ety of means, from the insidious voting fraud and use of

gerrymandering and at-large elections with white only

prim aries, to outright statu tory suffrage restrictions,

replacem ent of local elections with appointm ents and, of

course, with intimidation and violence.10

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963) (Equal Protection Clause requires that,

once a geographical unit for which a representative is to be chosen is desig

nated, all who participate in the election must have an equal vote regardless

of race or sex); Baker v. Carr; 369 U.S. 186 (1962); Reynolds v. Sims, 377

U.S. 533 (1964); see also Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) (Whit

taker, J., concurring) (noting that the Fourteenth Amendment, in addition to

the Fifteenth Amendment, might provide a source of authority in voting

rights cases).

9. Ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment did not alter the exclusion

of women of color from the United States’ electorate. The right to vote was

not extended to women until 50 years later, with the ratification of the

Nineteenth Amendment.

10. For a detailed analysis of the legal and extralegal means by which

10

M ost African Americans effectively lost the right to

vote by the end of the nineteenth century. Voters enfran

chised during Reconstruction were purged from the rolls.

The nation lapsed back into pre-abolition times. African

A m erican children were consigned to a separate and

often tangibly inferior education. The separate but equal

doctrine served to justify fu rther institutional racism,

supported and enforced through governmental action.

Nationwide, enforced separation in public accommoda

tions and most aspects of social life was common.11 All

this persisted despite the guarantee of racially impartial

suffrage set forth in the Fifteenth A m endm ent, and the

guarantee of equal protection under law provided for in

the Fourteenth Am endm ent.

Just as the door was closing on the struggle for Afri

can Am erican suffrage, the drive for wom en’s suffrage

was gaining m om entum . The Civil War Am endm ents

clearly served as an example and defined the objective

NOTES (Continued)

African American political power was diluted and African Americans were

disenfranchised after the Reconstruction era, see J. Morgan Kousser, The

Voting Rights Act and the Two Reconstructions, in Controversies in Minority

Voting 135 (Bernard Grofman & Chandler Davidson eds., 1992).

11. See generally Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896). African

Americans were not the only minority group subjected to such state-

enforced segregation. Virginia’s anti-miscegenation statute, invalidated by

this Court in Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) was also applied to sanc

tion a Chinese man and white woman who married in North Carolina and

returned to Virginia to live. See Naim v. Naim, 87 S.E. 2d 749 (Va.), vacated,

350 U.S. 891 (1955). The law made “any white person and colored person

. . . [leaving the] State, for the purpose of being married . . . with the inten

tion of returning . . . [and] cohabiting as man and wife” subject to one to five

years imprisonment, if convicted. Loving, 388 U.S. at 4-5. Asian- and Mexi

can American children, like African American children, were required to

attend segregated schools for a substantial part of this century. See, e.g.,

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927) (holding that exclusion of child of

Chinese ancestry from white schools was constitutionally permissible); West

minster Sch. Dist. v. Mendez, 161 F.2d 774 (9th Cir. 1947) (challenging seg

regation of Mexican-American children in public school system).

11

for the movem ent to amend the Constitution to eliminate

gender-based restrictions on the right to vote.12

The next series of voting rights related amendments,

the Seventeenth and N ineteenth A m endm ents, were

enacted during the Progressive era in the first quarter of

this century. The latter had a goal patently similar to that

of the Fifteenth Am endm ent — expanding the franchise,

in this case to include women. The form er’s extension of

popular election for Senators was another im portant

milestone in the development of the right to vote. 13

The N ineteenth A m endm ent, echoing the simple

text of the Fifteenth Amendment, provides, “The right of

citizens of the U nited States to vote shall not be denied

or abridged by the United States or by any State on

account of sex.” U.S. Const, amend. XIX, § 1. The N ine

teenth Am endm ent, as in every other amendm ent of sig

nificance to the right to vote, including the Fourteenth,

the Fifteenth, the Twenty-Fourth and the Twenty-Sixth,

includes a provision granting Congress the power “to

enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” See, e.g.,

U.S. Const, amend. XIX, § 2.

With the enactm ent of the Nineteenth Amendment,

the movement toward universal suffrage in the U nited

States made further strides. The inclusion of women, who

once were excluded from the political process purely on

the basis of sex, was a watershed event in American his

tory. W omen’s suffrage and the ratification of the N ine

teenth A m e n d m e n t continued the process of actualiza

tion of the principle of equality upon which the nation

was founded.14

12. Kris W. Kobach, Rethinking Article V: Term Limits and the Seven

teenth and Nineteenth Amendments, 103 Yale L.J. 1971, 1980 (1994).

13. The Seventeenth Amendment provides that: “The Senate of the

United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected

by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote.

The electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors

of the most numerous branch of the State legislature.” U.S. Const, amend.

XVII.

14. In some parts of the country, women, like the emancipated African

12

The movement toward universal suffrage continued

with the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Sixth Amendments.

The Twenty-Fourth A m endm ent disallowed the use of a

poll tax as a means of withholding the right to vote in

presidential and congressional elections.15 The Twenty-

N O TES (Continued)

American males who preceded them in suffrage, found that even an unam

biguous constitutional amendment could not ensure full incorporation into

political life. In Georgia, for example, ballots cast by newly enfranchised

women voters were targeted in disqualification petitions. See, e.g., Haw

thorne v. Turkey Creek Sch. Dist., 134 S.E. 103 (Ga. 1926); Stephens v. Ball

Ground Sch. Dist., 113 S.E. 85 (Ga. 1922). Within one year after the ratifi

cation of the Nineteenth Amendment, the Georgia legislature enacted laws

extending the poll tax (which was originally enacted after the ratification of

the Fifteenth Amendment) to women registrants. Hawthorne, 134 S.E. at

106-07. The poll tax applied somewhat differently to women than to men,

however. Women, unlike men, were relieved of the obligation of paying any

tax (at the rate of one dollar per year) for years after they became legally

eligible to register (i.e., age 21) but declined to do so. Nolen R. Breedlove,

a 28 year old white man who was unable to demonstrate that he had paid

poll taxes during the seven years in which he was legally eligible to register,

was not allowed to register to vote after refusing to pay his “back” poll

taxes. Breedlove v. Suttle, 302 U.S. 277,280 (1937). Breedlove challenged the

denial of registration on the ground that it violated the Nineteenth Amend

ment and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This

Court rejected Breedlove’s arguments, holding that “women may be

exempted [from payment of accrued poll taxes] on the basis o f . . . [the] bur

dens necessarily borne by them for the preservation of the race,” and

because “[t]he laws of Georgia declare the husband to be the head of the

family and the wife subject to him.. . . [Therefore, t]o subject her to the levy

would be to add to his burden.” Id. at 282.

In the year after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the

Georgia legislature also passed a law which provided “that ‘females’ shall

not be liable to discharge any military, jury, police, patrol or road duty.’”

Powers v. State, 157 S.E. 195 (Ga. 1931). The Georgia Supreme Court held

that this law was “not obnoxious to the Nineteenth Amendment,” id., and

reaffirmed the Powers holding more than a decade later in Cady v. State, 31

S.E. 2d 38, 42 (Ga.), cert, denied, 323 U.S. 676 (1944).

Finally, Georgia was not among the states responsible for the ratifica

tion of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. In fact, the Georgia Legislature

did not ratify the amendment until February 20, 1970. U.S. Const., amend.

XIX (West U.S.C.A. 1987) at 983.

15. U.S. Const, amend. XXIV, § 1.

13

Fourth Am endm ent, “testifies to the now prevalent opin

ion that financial considerations or economic interests

should n o t bear upon o n e ’s eligibility or pow er to

vote.”16

The Twenty-Sixth A m endm ent provides, “The right

of citizens of the U nited States, who are eighteen years

of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged

by the U nited States or by any State on account of age.”

U.S. Const, amend. XXVI. This most recent am endm ent

to the Constitution rem oved yet another great barrier to

participation in the political process. The inclusion of

younger people contributed immensely to the further

expansion of the franchise.

This history of am endm ents to the C onstitu tion

reveals the devotion to expansion and broadening of the

right to vote for all Americans. This history also provides

a fram ework for the following discussion of congres

sional enactments to enforce these constitutional guaran

tees, and the decisions of this Court that have reaffirm ed

them.

II. THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT AND ITS AMEND

MENTS DEMONSTRATE THE COMMITMENT OF

CONGRESS TO ENFORCING THE CONSTITU

TIONAL GUARANTEE OF EQUAL POLITICAL

OPPORTUNITY

In Reynolds v. Sims, this Court recognized that “to the

extent . . . a citizen’s right to vote is debased, he is that much

less a citizen.” 377 U.S. at 567. One year after Reynolds was

decided, Congress exercised its power under Section 2 of the

Fifteenth Amendment to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

An analysis of the legislative history of the Act provides fur

ther evidence of the importance of inclusiveness as a funda

mental principle of a fair and democratic government.

16. Anastaplo, supra note 6, at 836. See also National Voter Registra

tion Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-31, 107 Stat. 77 (codified at 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973gg-l et seq. (1994)) (enhancing access to voter registration and pro

viding, inter alia, for voter registration to be conducted at public assistance

agencies).

14

President Lyndon Johnson’s comments upon signing

the Act into law reveal the aspirations of those who

fought for the A ct’s passage:

The vote is the most powerful instrument ever devised by

man for breaking down injustice and destroying the ter

rible walls which imprison men because they are different

from other men.17

The Act represented a major contribution to the promotion of

fairness and participation in the political process by a coordi

nate branch of government.

In South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966), the

Court upheld the constitutionality of the Act. Under the Act,

literacy tests were suspended in states which had a history of

discrimination in voting.18 The Court upheld this provision of

the Act, explaining that the Act employed this remedy in

response [to] the feeling that States and political subdivi

sions which had been allowing white illiterates to vote for

years could not sincerely complain about ‘dilution’ of

their electorates through the registration of Negro illiter

ates. Congress knew that continuance of the tests and

devices in use at the present time, no matter how fairly

administered in the future, would freeze the effect of past

discrimination in favor of unqualified white registrants.

Id. at 334.

At the conclusion of its opinion in Katzenbach, the Court

stated that the Act is “a valid means for carrying out the com

mands of the Fifteenth Amendment. Hopefully, millions of

17. Steven F. Lawson, Black Ballots: Voting Rights in the South, 1944-

1969 at 3-4 (1976) (quoting President Lyndon B. Johnson).

18. While the use of literacy tests as a device for disenfranchising racial

and language minorities is well known, in at least one state an attempt was

made to invalidate ballots cast by women — but not men — on the ground

of illiteracy. See Prewitt v. Wilson, 46 S.W.2d 90 (Ky. Ct. App. 1932). The

court labelled the disqualification effort “specious” and held that “male vot

ers [we]re not required to meet the same test . . . [so] it is therefore discrimi

natory against [women].” Id. at 92.

15

non-white Americans will now be able to participate for the

first time on an equal basis in the government under which

they live.” Id. at 337.

Since its enactment in 1965, the Act has been amended

four times. Each set of amendments reflects the inexorable

movement toward a more inclusive broad-based democracy.

The first set of amendments, enacted as the Voting Rights Act

Amendments of 1970, Pub. L. No. 91-285, 84 Stat. 314 (codi

fied as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973 to 1973bb-l (1994)),

broadened the franchise by expanding the Act’s coverage to

include many jurisdictions, especially those outside the deep

South, that were exempt from the Act as originally enacted.

The amendments also expanded the franchise by granting

eighteen-year-old citizens the right to vote. Id. The desire for

full inclusion of all American citizens in the political process

was at the core of Congress’ decision to amend the Act. Sena

tor Barry Goldwater, one of the sponsors of the 1970 amend

ments, testified:

Being members of the same political community, it is my

view that all citizens possess the same inherent right to

have a voice in the selection of the leaders who will guide

their government.

Amendments to the Voting Rights Act o f 1965: Hearings before

the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights o f the Committee on

the Judiciary, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 282 (1970) (statement of

Hon. Barry Goldwater). The statement of Attorney General

John N. Mitchell also illustrates the spirit underlying the hear

ings:

The right of each citizen to participate in the electoral

process is fundamental in our system of Government. If

that system is to function honestly, there must be no arbi

trary or discriminatory denial of the voting franchise. . . .

We have come to the conclusion that voting rights is . . . a

national concern for every American. . . . Our commit

ment must be to offer as many of our citizens as possible

the opportunity to express their views at the polls on the

issues and candidates of the day.

16

Id. at 182-83 (statement of Hon. John N. Mitchell).

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), unanimously held

that multimember state House of Representative districts in

two Texas counties violated the constitutional rights of Afri

can Americans and Mexican Americans, in violation of the

Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, by “cancelling]

out or minimiz[ing] thefir] voting strength,” Id. at 765. This

Court specifically noted the district court’s findings that

despite the substantial African American population in Dallas,

“since Reconstruction . . . there ha[d] been only two Negroes

in the Dallas County delegation to the Texas House of Repre

sentatives;” that a “white-dominated organization” in Dallas

County controlled Democratic Party candidate slating; and

that “racial campaign tactics . . . [targeting white voters were

used] to defeat candidates who had the overwhelming support

of the black community.” Id. at 766-67.

Similarly, this Court noted in White that San Antonio’s

Hispanic community, “along with other Mexican-Americans in

Texas, had long suffered from, and continue[d] to suffer from,

the results and effect of invidious discrimination and treat

ment in the fields of education, employment, economics,

health . . . [and] politics.” Id. at 768. The Court also noted that

although Mexican-Americans comprised nearly 30 percent of

the total population of the county, “only five Mexican-

Americans since 1880 ha[d] served in the Texas legislature

from Bexar County.” Id. at 768-79. These factors, among oth

ers, influenced this Court’s decision to affirm the district

court’s holding that “the multimember district, as designed

and operated in Bexar County, invidiously excluded Mexican-

Americans from effective participation in political liege, spe

cifically in the election of the representative to the Texas

House of Representatives.” Id. at 769. In response to these

circumstances, “[s]ingle-member districts were .. . required to

remedy the effects of past and present discrimination against

Mexican-Americans’ . . . and bring the community into the full

stream of political life of the county and State.” Id.

Two years after the White decision, “the minority lan

guage provisions were added to the Act upon determination

by the Congress that ‘voting discrimination against [language

17

minority] citizens . . . is pervasive and national in scope.’ ”

Congress found that because of the denial of equal educa

tional opportunities by State and local governments, language

minorities experienced severe disabilities and illiteracy in the

English language that, together with English-only elections,

excluded them from participation in the electoral process.19

The legislative history accompanying the language minor

ity provisions added to the Voting Rights Act in 1975 (42

U.S.C. §1973b(f)(l)) documents a pattern of discrimination

against language minorities which has interfered with their

exercise of the fundamental right to vote. See, e.g., Voting

Rights Act Extension, H. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

1975; Voting Rights Act of 1965 — Extension, S. Rep. No. 295,

94th Cong, 1st Sess. 1975, reprinted in 1975 U.S.C.C.A.N. 11 A.

Congress found that “[ljanguage minorities, like blacks

throughout the South, must overcome the effects of discrimi

nation as well as efforts to minimize the impact of their politi

cal participation.” H.R. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1975) at 16-17.

Congress recognized that by broadening the prohibition

of “discriminatory tests or devices” so as to preclude English-

only ballots, non-English-speaking citizens were more likely to

realize a meaningful franchise. Id. As in 1965 and 1970, broad

ening the franchise was, again, at the core of the debate:

In the quest for the right to vote, Spanish-speaking citi

zens have had many experiences which were similar to

those of blacks. It is time for the nation to end discrimi

nation which is based on national origin. Just as the Vot

ing Rights Act has brought about progress among blacks

and whites in the South, it can be an instrument of

progress for all people in those areas where there are

Spanish-speaking communities.

19. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights Act: Unfulfilled

Goals 77 (1981), quoting United States Senate, Subcommittee on Constitu

tional Rights o f the Committee on the Judiciary, Extension o f the Voting

Rights Act o f 1965: Hearings on S.407, S.903, S.1509, and S.1443, 94th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1975).

18

Hearings on the Voting Rights Act Amendments Before the

Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights o f the Senate

Judiciary Committee, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 64 (1975) (testi

mony of Hon. Andrew Young).

Some of the barriers to political participation that lan

guage minorities have faced are identical to those used to

impede African American voter participation and dilute Afri

can American voting strength. They include imposition of the

poll tax, erection of barriers to voter registration by hostile

election officials, and the manipulation of election district

boundaries to dilute political support for their preferred can

didates and ensure control of elections by white voting blocs.

H. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975), at 16-20; S. Rep.

No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975), at 26; see also H. Rep.

No. 94-196 at 22 (noting federal court finding that state of

Texas has “a history pockmarked by a pattern of racial dis

crimination that has stunted the electoral and economic par

ticipation of the black and brown communities in the life of

the state”). More recently, the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit, in League o f United Latin American Citi

zens v. Midland Independent Sch. Dist., 812 F.2d 1494 (5th

Cir.), vacated on other grounds en banc, 829 F.2d 546 (5th Cir.

1987), recognized that African American and Hispanic Texans

“share[d] common experiences in past discriminatory prac

tices.” Id. at 1500.

At the beginning of this decade, a federal court found

that Los Angeles, California’s Hispanic community “has borne

the effects of a history of discrimination in the areas of educa

tion, housing, employment, and other socioeconomic areas.”

Garza v. County o f Los Angeles, 756 F. Supp. 1298, 1339-40

(C.D. Cal.), a ff’d, 918 F.2d 763 (9th Cir. 1990), cert, denied, 498

U.S. 1028 (1991). For a decade “in the aftermath of the

Depression, some 200,000 to 300,000 Mexican-Americans

returned to their ‘country of origin a part of a program insti

tuted by the Justice Department. . . . [MJany legal resident

aliens and American citizens of Mexican descent were

[thereby] forced or coerced out of the county.’ ” Id. The court

noted that Mexican-Americans in Los Angeles were blatantly

19

discriminated against in public accommodations and education

throughout the first half of this century:

School officials required Mexican children to have sepa

rate graduation ceremonies from Anglos attending the

same school. . .. California maintained segregated schools

for Hispanics in Los Angeles until 1947 when the Califor

nia Supreme Court struck down such segregation. . . .

However, . . . schools desegregation litigation involving

[Los Angeles County school] districts . . . continued until

1989. . . . [I]t was common during the first decade of this

century, for access to public swimming pools to be

restricted for Mexican-Americans and blacks, usually to

the day before the pool was to be cleaned.

Id. at 1340. It was not until 1970 that the California Supreme

Court invalidated a California constitutional provision “condi

tioning the right of persons otherwise qualified to vote upon

the ability to read the English language.” Id. (citing Castro v.

State o f California, 466 P.2d 244 (Cal. 1970)).

The Garza court also found that Esteban Torres a His

panic candidate for the United States House of Representa

tives, “encountered racial appeals by his opponents in the

form of statements that Mr. Torres catered only to Hispanics

and in the use of his photograph in opponents’ campaign lit

erature.” Id. at 1331, 1341. In Torres’ race, like all but a hand

ful of the elections analyzed by plaintiffs’ experts, non-

Hispanic voters overwhelmingly rejected the Hispanic

candidate. Id. at 1336-37.

Since the extension of the Act in 1975 to cover language

minorities, the number of Hispanic elected officials has

increased dramatically. In 1973, the six states with the largest

Hispanic populations had 1,280 Hispanic elected officials.

Twenty years later this number had jumped to 3,999.20

20. 1993 National Roster of Hispanic Elected Officials at vii (1993)

(Table 18: Hispanic Elected Officials by Selected States, 1984-1993). Pre-

1980 data is available only for the following six states: Arizona, California,

Florida, New Mexico, New York, and Texas. Nationwide data is available

starting in 1984. In that year the total number of Hispanic elected officials

was 3,128; in 1993 it was 4,420. This number excludes 750 local school coun-

20

Unquestionably, the creation of districts which afford Hispanic

voters a realistic opportunity to elect candidates of their

choice has contributed to these gains. Since the extension of

the Act, the Hispanic population has also achieved substantial

gains in its participation in the political process. The number

of Hispanic registered voters nearly doubled from 1972 to

1988, increasing from 2.495 million to 4.573 million.21 This

increased registration manifested itself in higher Hispanic

voter turnout, as well.22 Despite these gains, although Hispan-

ics constitute nine percent of the total population of the

United States, they account for only slightly more than one

percent of the publicly-elected officials in the nation.23 The

work started by the passage of the Act is not yet complete.

The result herein must not create an environment in which the

progress which has been made will be reversed.

The experience of Asian Americans in many respects par

allels the experience of Mexican Americans described by the

Garza court. “[UJntil 1947, a California statute authorized

local school districts to maintain separate schools for children

of Asian descent.” S. Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1975) at 28 (citing Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S. 1215

N O TES (Continued)

cil members in the Chicago area, positions which were not included in the

1984 count.

21. The Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, Legacy: 1974-

1990, at 2. During this period the number of Hispanic registered voters

increased by 83 percent. This number’s true significance becomes apparent

only after comparable rates are considered for other segments of the popu

lation. From 1972 to 1988 the number of white registered voters increased

by 17 percent and that of African Americans by only 44 percent. Id.

22. For five southwestern states (Arizona, California, Colorado, New

Mexico and Texas), votes cast by Hispanics increased 60.9 percent, from

1.016 million in 1976 to 1.634 million in 1988. Legacy, supra note 21, at 2.

Comparison data is available for the period 1984 to 1988. During this time

Hispanic turnout increased 20 percent; for the nation as a whole, it increased

0.3 percent. Id.

23. 5,170 Hispanics (including the Chicago school officials) held

publicly-elected offices in 1993, as compared to 504,404 publicly-elected

offices nationwide (1.0 percent). 1993 National Roster of Hispanic Elected

Officials at viii.

21

(1971)). Hostility toward Asian immigrants led to strict regu

lation of entry to the United States and bans on naturalization.

Persons of Japanese ancestry were once completely denied the

opportunity to become naturalized citizens. Takao Ozawa v.

United States, 260 U.S. 173 (1922). “Filipinos, who were sub

jects of the United States . . . [were nevertheless] ineligible for

citizenship unless they served three years in the U.S. Navy. . . .

[and] Chinese immigrants were not allowed to gain citizenship

until 1943. ”24 Japanese Americans were removed from their

homes and confined to internment camps during World War

II. See Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943); Kore-

matsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944).25 Regrettably, as

Congress noted in the legislative history accompanying the

1975 amendments to the Act, “[discrimination against Asian

Americans is a well-known and sordid part of our history.” S.

Rep. No. 94-295 at 28 n.21.

Limited English proficiency has remained a serious bar

rier to effective political participation for many Asian-

Americans in the United States. See The Voting Rights Act

Language Assistance Amendments o f 1992, S. Rep. No. 315, at

5-6, 102d Cong., 2d Sess. (1992). Although Asian-Americans

comprise almost 10% of California’s population, only one

Asian American, elected in 1992, is serving in the California

state legislature. And in New York City, which has an Asian-

American population of over 512,000, no Asian-American has

ever been elected to the New York City Council or the New

York state legislature. See U.S. Civil Rights Comm’n, Civil

Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990s 157 (1992).

The most recent amendments to the Act were passed with

broad bipartisan support in August 1992, affecting over

200,000 Asian Americans with limited English proficiency

across the nation. The Voting Rights Language Assistance Act

of 1992 expanded the minority language requirements of Sec

tion 203 of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973aa-la, to require multilin

24. Karen McGill Arrington, The Struggle to Gain the Right to Vote:

1787-1965, in Voting Rights in America: Continuing the Quest for Full Par

ticipation (Karen McGill Arrington and William L. Taylor, eds., 1992) at 34.

25. See also Eugene Rostow, The Japanese-American Cases — A Disas

ter, 54 Yale L.J. 489 (1945).

22

gual voting materials and assistance in jurisdictions with at

least 10,000 voting age citizens of a single language minority

group. Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1992, § 2, Pub. L.

No. 102-344,106 Stat. 921 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §

1973aa-la (1994)). These amendments enable the Asian

American community to participate more effectively in the

political process.

The 1982 amendments to the Act, promulgated shortly

after (and in response to) this Court’s decision in City o f

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), reflect Congress’ contin

ued determination to refine the Act so as to expand and

amplify the right to vote and, thereby, prevent vote dilution.

In 1982, Congress rejected an intent-based standard in favor

of a test that focused on the “effect” of a challenged practice.

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, S. Rep. No. 417, 97th

Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in, 1982 U.S.C.C.A.N. 177, 191.

Thus, these amendments fostered access to the political pro

cess by, inter alia, prohibiting voting practices that “result [] in

a denial or abridgment of the r ight . . . to vote.” Voting Rights

Act Amendments of 1982, § 3, Pub. L. No. 97-205, 96 Stat.

131, 134 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1973(a)). These

amendments were enacted to redress the more subtle forms of

discrimination that had emerged during the seventeen year

period since the Act was first passed.

The Senate Report accompanying the 1982 amendments

reveals that, no less than in 1965, expanding the franchise

remains inextricably intertwined with Congress’ intent to

ensure electoral equality in an inclusive democracy:

The Committee bill will extend the essential protection of

the historic Voting Rights Act. It will insure that the hard-

won progress of the past is preserved and that the effort

to achieve full participation for all Americans in our

democracy will continue in the future.

Seventeen years ago, Americans of all races and creeds

joined to persuade the Nation to confront its conscience

and fulfill the guarantee of the Constitution.. . .

As a result of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, hundreds of

23

thousands of Americans can now vote and, equally impor

tant, have their vote count as fully as do the votes of their

fellow citizens.

See S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982), at 214.

On June 29, 1982, President Reagan signed the Voting

Rights Act Amendments of 1982 into law, announcing: “As

I’ve said before, the right to vote is the crown jewel of Ameri

can liberties, and we will not see its luster diminished.”26

In the almost thirty years since the enactment of the Act,

the Court has generally endorsed its application and exten

sion. In 1969, the Court held that minority citizens could assert

a claim for “vote dilution” under the Act. Allen v. State Board

o f Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 569 (1969) (at-large or multimem

ber elections could nullify minority voters’ “ability to elect the

candidate of their choice just as would prohibiting some of

them from voting.”).27 It therefore gave a broad reading to the

preclearance provisions of Section 5 of the Act.28

In 1986, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the 1982

amendments to the Act and eased the evidentiary require

ments for asserting a claim of minority vote dilution by elimi

nating the requirement of proof of discriminatory' intent.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).

In subsequent decisions, the Court approved expanding

the application of Section 5’s preclearance requirement and

invigorated the remedy available to enforce Section 5. The

Court held that Section 5 covered municipal annexation deci

26. White House Press Release (June 29,1982).

27. C f Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433, 439 (1965) (multimember dis

tricting plan that “designedly or otherwise, . . . operatefd] to minimize or

cancel out the voting strength of racial or political elements of the voting

population” would violate the Equal Protection Clause); Mobile, 446 U.S. at

126 (“The Court has long understood that the right to vote encompasses

protection against vote dilution. ‘[T]he right to have one’s vote counted’ is

of the same importance as ‘the right to put a ballot in a box.’ ”) (Marshall,

J. dissenting).

28. See also NAACP v. Hampton County Election Comm’n, 470 U.S.

166, 175-76 (1985); Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973) (holding

that Section 5 must be liberally construed to effectuate its remedial pur

pose).

24

sions motivated by an improper purpose. Pleasant Grove v.

United States, 479 U.S. 462 (1987). It then held that a district

court has the authority to enjoin elections if the challenged

voting statutes have not been precleared under Section 5.

Clark v. Roemer, 500 U.S. 646 (1991).

The Court recently extended the reach of Section 2 to

elected state judiciaries, stating that the Act “should be inter

preted in a manner that provides ‘the broadest possible scope’

in combatting racial discrimination.” Chisom v. Roemer, 501

U.S. 380, 403 (1991) (quoting Allen, 393 U.S. at 567); see also

Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v. Attorney General, 501 U.S. 419

(1991).

Finally, last term in Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S. Ct. 2647

(1994), the Court reaffirmed the Gingles framework for ana

lyzing Section 2 claims and noted that “society’s racial and

ethnic cleavages sometimes necessitate majority-minority dis

tricts to ensure equal political and electoral opportunity.” Id.

at 2661.

Amendments to the Act have resulted in a dramatic