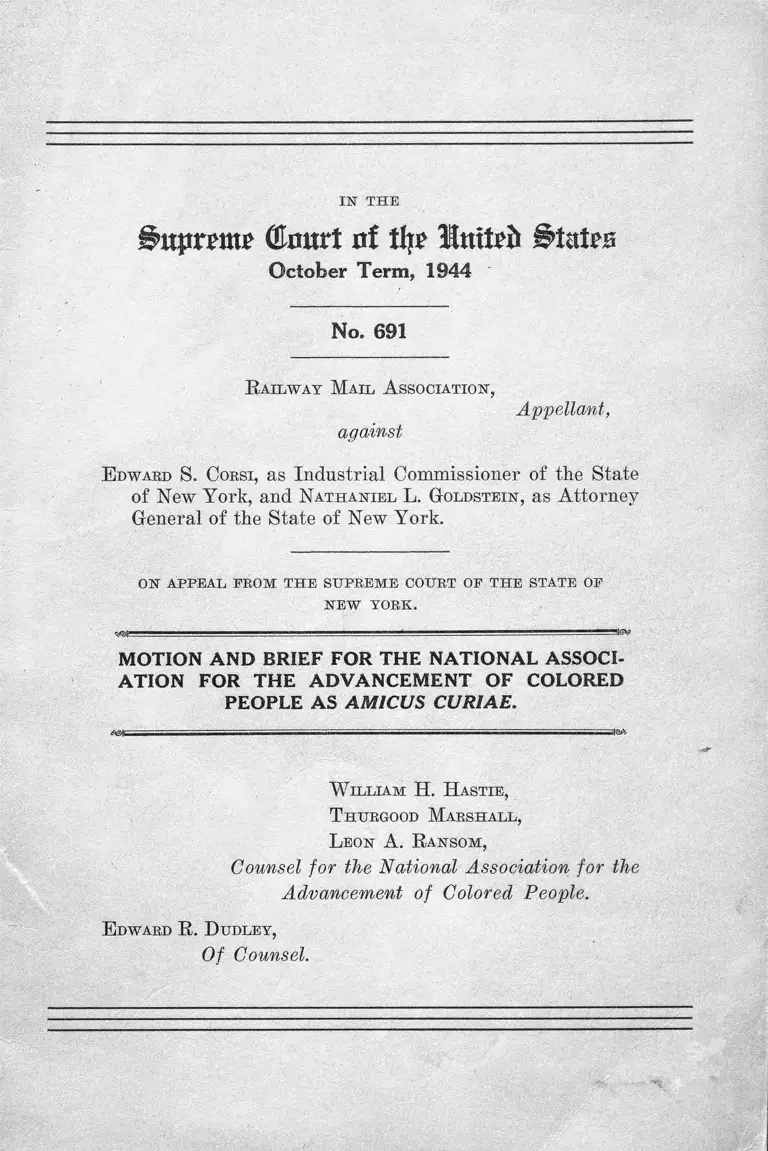

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1944

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Railway Mail Association v. Corsi Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1944. f1fd32ca-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/29c848c1-cba2-4cbf-907a-cbdddcf0e3d2/railway-mail-association-v-corsi-motion-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

(&mvt n! % Inttefc States

October Term, 1944

No. 691

R ailw a y M ail A ssociation ,

against

Appellant,

E dward S. C obsi, as Industrial Commissioner of the State

of New York, and N a t h a n ie l L. G oldstein , as Attorney

General of the State of New York.

O N A P P E A L FR O M T H E SU P R E M E COURT OP T H E STATE OP

N E W Y O R K .

MOTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCI

ATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED

PEOPLE AS AMICUS CURIAE.

*-mr-------i ..............~ ..................................... - ......... ....................'........... ................................ ........................ -----------------------....................:i—

W il l ia m H . H astie,

T hubgood M arsh all ,

L eon A . R an som ,

Counsel for the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People.

E dward R . D udley ,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Brief as amicus curiae--------- 1

Brief for the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People as amicus curiae—_----------- 3

Opinions B elow ------------------------------------------ — 3

Statutes Involved ----------------- 3

Question Presented----------------------------------------- 3

Statement of the Case---------- 4

Argument:

I Analysis of Appellant’s Claim of Unconstitution

ality ____________________________________________ 5

II Social and Economic Effects of Union Discrimina

tion -------------------------------------------- ^

III Reasonableness of Section 43 and its Application

to Appellant------------------------------------------------------- 14

IV Trend of Legislation and Adjudication in Other

States as Additional Indicia of Reasonableness----- 17

V Relation of Section 43 to Federal Authority-------- 20

Conclusion___________________________________ 23

Table of Cases.

Allen-Bradley Local, etc. v. Wisconsin Employment

Relations Boards, 315 U. S. 740, 751 (1941)------------ 21

Cameron v. International Alliance of Theatrical Stage

Employees, 118 N. J. Eq. 11, 176 Atl. 692 (1935);

cert, denied, 298 U. S. 659-------------------------------------- 19

Carpenters and Joiners Union v. Ritters Cafe, 315

U. S. 722 (1941)_________________________-________ 21

Carroll v. Local No. 269, 31 Atl. (2d) 223, 225 (N. J.

1943)______ -________________ ______________ _____ 20

11

PAGE

James v. Marinship Corporation, S. F. No. 17,015------- 18

Kelly v. Washington, 302 U. .S. 1, 10 (1937)___________ 21

Lncke v. Clothing Cutters Assembly, 77 Neb. 396, 26

Atl. 505 (1893) __________________________________ 19

Milkwagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor Dairies, 312

U. S. 287 (1940)__________________________________ 21

Miller v. Ruehl, 166 Misc. 479, 2 N. Y. S. (2d) 394------- 19

Murphy v. Higgins, 12 N. Y. S. (2d) 913-------- -------- -— 19

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Ry. Co., 65 Sup. Ct.

226 (1944) _________ _ ____ ---------------------------------- 22

Wills v. Local No. 106, 26 Ohio N. P. (N. S.) 435______ 19

Statutes.

Executive Order No. 9346, May 27, 1943------------------ 18, 22

Kansas, Act of 1941, Chap. 265---------------------------------- 18

Nebraska, Acts of 1941, Chap. 96 ... ---------------------------- 18

New York State Civil Rights Law----------------------------- 5

Pennsylvania, Acts of 1937, Chap. 294-------------------- —- 18

Wisconsin, Laws of 1939, Chap. 57----------------------------- 18

Miscellaneous.

Cayton and Mitchell, “ Black Worker and the New

Unions” (1939) __________— ----------------------------- 6

Commission of Inquiry, Interchurch World Movement,

Report on Steel Strike of 1919 (1920)----- --------------- 7

Feldman, “ Racial Tension in American Industry”

(1931) ________-____________________ ________ ____ 8

Franklin, “ The Negro Labor Unionist in New York”

(1934)_________________________________________ 6,12

House Report No. 187, 79th Cong. 1st Session-----------18

Northrup, “ Organized Labor and the Negro” (1944) 6, 7,16

Reid, “ Negro Membership in American Labor Unions”

(1930) ________ -___________________________ 6

I l l

PAGE

Report of New York? State Temporary Commission on

the Conditions of Colored Urban Population (Feb

ruary, 1939), New York State Legislative Docu

ment No. 69 (1939) --------------------------------------------- 13

4 Restatement, Torts, Sec. 794, Comment; Sec. 810— 19,20

Senate Report No. 1109, 78th Cong. 2nd Session--------- 18

Spero and Harris, ‘ ‘ The Black Worker” (1931)--------- 6, 8

United States Census of Partial Employment, Unem

ployment and Occupation, 1937----------------------------- 13

Wesley, “ Negro Labor in the United States” (1927)— 6

IN THE

(Emtrt of ti|£ HUnxUb

October Term, 1944

No. 691

R ailw ay M a il A ssociation ,

against

Appellant,

E dward S. Corsi, as Industrial Commissioner of the State

of New York, and N a t h a n ie l L. G oldstein , as Attorney

General of the State of New York.

on appeal from t h e supreme court of th e state of

N E W Y O R K .

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS

AMICUS CURIAE.

To the Honorable, The Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of

the United States:

The undersigned, as counsel for and on behalf of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, respectfully move that this Honorable Court grant

them leave to file the accompanying brief as Amicus Curiae.

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People is a membership organization which has for

the past thirty-five years continuously advocated full

citizenship rights for all American citizens. This Associ

ation has dedicated itself to work for the achievement of

2

functioning democracy and equal justice under the Consti

tution and laws of the United States.

As will more fully appear in the accompanying brief,

this Court is here asked to decide whether a section in the

New York Civil Eights Law which forbids denial of mem

bership in any labor organization to any person by reason

of his race, color or creed is applicable to a labor organiza

tion composed of members employed by the United States

and engaged in the Postal Service. The question is essen

tially whether the Constitution and laws of the United

States forbid a State from enacting such a law applicable

to and regulating equally the conduct of any labor organiza

tion operating within the State, regardless of whether the

said organization is composed of employees of the United

States, the State or private employers.

It is to present written argument on this issue, funda

mental to the good order and economic security of the

community, that this motion is filed.

The Attorney General of New York, on behalf of both

appellees, has consented to the filing of this brief. Counsel

for appellants has been requested but has refused to con

sent to the filing of this brief.

W illiam H . H astie,

T hubgood M arsh all ,

L eon A. R an som ,

Counsel for the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People.

E dwabd E . D udley ,

Of Counsel.

i§>ttpr?mp (SImtrt nf tip States

October Term, 1944

IN THE

No. 691

R ailw ay M ail A ssociation ,

against

Appellant,

E dward S. C orsi, as Industrial Commissioner o f the S tate

o f New York, and N ath a n ie l L. G oldstein , as Attorney

General o f the State o f New York.

O N A PPE A L FRO M T H E SU P R E M E COURT OF T H E STATE OF

N E W Y O R K .

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE AS

AMICUS CURIAE.

Opinions Below.

Statutes Involved.

The opinions below and the statutes involved are set

out in full in the record and in the briefs for both parties

filed herein.

Question Presented.

The question presented by this Appeal and to which this

brief is addressed is :

Is the Statute of the State of New York (Civil Rights

Law, Section 43, enacted L. 1940, C.9) which forbids a labor

3

4

organization, including the appellant association, from de

nying membership in such organization by reason of race,

color or creed unconstitutional?

Statement of the Case.

The appellant herein is a foreign corporation organized

under the laws of the State of New Hampshire. Through

subordinate local units functioning in different parts of the

State of New York it carries on the business of the cor

poration as set out in its charter, viz., “ to conduct the busi

ness of a fraternal beneficiary association for the sole bene

fit of its members and beneficiaries and not for profit; to

promote closer social relationship among railway postal

clerks; to better enable them to perfect any movement that

may be for their benefit as a class or for the benefit of the

Railway Mail Service, * * * ” .

Membership in the Association is limited by its Consti

tution to “ any regular male railway postal clerk or male

substitute postal clerk of the United States Railway Mail

Service who is of the Caucasian race or native American

Indian.” Section 43 of the New York Civil Rights Law pro

vides in part that, “ no labor organization shall hereafter,

directly or indirectly # * * deny person or persons member

ship in its organization by reason of his race, color, or

creed * * *.

Appellant brought an action for a declaratory judgment

seeking to have the Court hold that Sections 41, 43 and 45

of the Civil Rights Law of the State of New York and the

provisions of the labor law do not apply to appellant and

that the Railway Mail Association is not a labor organiza

tion within the meaning and contemplation of said laws.

Appellant also asked the Court to declare “ that if sought

to be applied to the appellant therein, such laws are in

contravention to the Constitution of the Unied States.”

5

The appellees, the Industrial Commissioner of the State

of New York and the Attorney General of the State of New

York, deny appellant’s allegation that it is not a labor

organization within the meaning of Section 43 of the New

York Civil Eights Laws, and the Court of Appeals held that

appellant is in fact and law a labor organization within the

meaning of said statute.

A R G U M E N T .

I.

Analysis of Appellant’s Claim of

Unconstitutionality.

So much of the claim of the appellant as is founded upon

constitutional grounds asserts in essence that the applica

tion of Section 43 of the New York Civil Rights Law to

appellant is made pursuant to arbitrary and unreasonable

classification, and at the same time is an unwarranted in

vasion of an area of Federal jurisdiction and control. The

latter contention cannot mean that a private organization,

particularly a foreign corporation, functioning within a

State is beyond reach of the police power of that State be

cause its members are employees of the United States. To

be even colorable, any argument of interference with a fed

eral function in such a case as this must purport to show

that in attempting to promote its own soverign interests

the State is actually or potentially impeding the nation’s

business or overriding national authority.

To test this contention it becomes necessary to examine

the occasion for and the effect of the legislation in question.

Such examination will reveal that the application of Section

43 to appellant does not interfere with any Federal function

and at the same time that it is predicated upon reasonable

classification. Thus, both branches of the argument of un-

6

constitutionality become untenable in the light of an exposi

tion of the social and economic basis and effect of Section

43.

n.

Social and Economic Effects of Union

Discrimination.

Throughout the history of American organized labor

the exclusion of Negroes from labor unions has promoted

strife between white and colored workmen and operated as

a disturbing factor of major importance in industry and

commerce. Besultant disorders have been so frequent and

so serious as to constitute a substantial menace to the gen

eral security.

As early as 1855, in the State of New York, when white

longshoremen who monopolized the port of New York were

called out on strike, unorganized Negroes were called in

as strikebreakers. Disorder and rioting were the results.1

This is not an isolated case. The sequence of certain unions

excluding Negroes, white workmen striking, unorganized

and embittered Negro strikebreakers replacing the whites,

and then serious racial strife, has been a familiar pattern

in American industrial life for almost a century.2

The great Knights of Labor strike of 1886,3 the national

steel strike of 1919 broken by some 40,000 unorganized

1 Wesley, Negro Labor in the United States (1927) 79-80.

2 See Cayton and Mitchell, Black Workers and the New Unions

(1939) ; Franklin, The Negro Labor Unionist in New York (1934) ;

Northrup, Organized Labor and the Negro (1944 ); Reid, Negro

Membership in American Labor Unions (1930) ; Spero and Harris,

The Black W orker (1931) ; Wesley, op cit. supra note 1.

3 See Northrup, op cit. supra note 2, at 78.

7

Negro workmen,4 the continuing racial strife over railroad

employment,5 the scandalous spectacle of our present war

effort being impeded by the failure of unions to accept

Negro workers are but the most sensational manifestations

of a grave social and economic evil.

The total social effect of such events recurring in com

munity after community is hurtful beyond measure. As

one commentator has put it :

“ Aside from availability in strikes, the employ

ment of Negro labor is used to intimidate the white

workers and to serve as a threat that should they

give up their jobs they may find them filled by the

colored workers. The exclusion of Negroes from the

white unions has aided the employers ’ purpose, since

the more Neg*roes he can intermingle in the plant the

fewer are the possibilities of complete union or

ganization.

“ One of the deplorable results of this oppor

tunism on the part of the Negro is to breed animosity

between white and colored workers, which, along with

other types of irritations, becomes the tinder to set

alight some spark of friction into a roaring flame

of race hatred. The grave social tragedy which some

times results from such a situation is described in a

report of the conditions arising in connection with

a strike in Chicago, from which the following excerpt

is taken:

“ ‘ It was natural that the strikers outside,

whose children were hungry, who saw their desire

thwarted to build on monthly payments a home for

themselves, should find a strong feeling growing

against those who, perhaps all unconsciously, were

lowering, not raising, the standard of living of the

4 See passim Commission of Inquiry, Interchurch World Move

ment, Report on Steel Strike of 1919 (1920).

5 See Northrup, op cit. supra note 2, Ch. 3.

8

community. A new prejudice was developed against

the strike-breaker, whether he was Greek or colored,

who was a commodity of labor hauled and delivered

from one labor battlefield to another. These immi

grant workers took at his human value the colored

worker who joined the union, or who worked by their

side and was a pleasant person. But the colored

strike-breaker was a different creature.’ ” 6

The 1924 Convention of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People expressed the general

alarm of thoughtful persons with reference to this critical

situation in the following open letter “ to the American

Federation of Labor and other groups of organized labor” :7

“ For many years the American Negro has been

demanding admittance to the ranks of union labor.

“ For many years your organizations have made

public profession of your interest in Negro labor, of

your desire to have it unionized, and of your hatred

of the black ‘ scab. ’

“ Notwithstanding this apparent surface agree

ment, Negro labor in the main is outside the ranks

of organized labor, and the reason is, first, that white

union labor does not want black labor, and secondly,

black labor has ceased to beg admission to union

ranks because of its increasing value and efficiency

outside the unions.

“ We face a crisis in inter-racial labor conditions;

the continued and determined race prejudice of white

labor, together with the limitation of immigration,

is giving black labor tremendous advantage. The

Negro is entering the ranks of semi-skilled and

skilled labor and he is entering mainly and necessarily

as a ‘ scab. ’ He broke the great steel strike. He will

6 See Feldman, Racial Factors in American Industry (1931), at

p. 33.

7 Quoted in Spero and Harris, op. cit. supra note 2, at 144.

9

soon be in a position to break any strike when he can

gain economic advantage for himself.

“ On the other hand, intelligent Negroes know

full well that a blow at organized labor is a blow at

all labor, that black labor today profits by the blood

and sweat of labor leaders in the past who have

fought oppression and monopoly by organization. If

there is built up in America a great black bloc of

non-union laborers who have a right to hate the

unions, all laborers, black and white, eventually must

suffer.

“ Is it not time then that black and white labor get

together? Is it not time for white unions to stop

bluffing and for black laborers to stop cutting off

their noses to spite their faces?”

The State of New York has experienced its full share of

the evil consequences of racism in labor organization.

From the already cited waterfront strike of 1855 to the

Ward Line strike of 1895, racial clashes arising out of

union exclusion kept New York in intermittent turmoil.

Rioting, violent death and large scale property destruction

were the recurrent fruits of divisive and discriminatory

union practices. This sorry chapter of New York history

is briefly summarized in the most frequently cited treatise

on American Negro labor:

“ The Negro came into longshore work in the

North before the Civil War. He was brought in for

the most part as a strike breaker or as an instrument

to divide and weaken white workers. His use for

such purposes was so extensive that his presence

came generally to be resented, even when his employ

ment was altogether innocent of anti-organization de

signs. This resentment was frequently so bitter as

to result in riot and bloodshed. Such a riot broke

out in New York in 1855 when Negroes were used to

break a water front strike. The situation was re

1 0

peated in Buffalo in the summer of 1863 when the

boss stevedores tried to fill the places of former white

workers with Negroes and provoked a serious fight

in which twelve black men were badly beaten, while

one was killed in the fighting and two were drowned.

The predominant longshore group of the day was the

Irish, who were then seldom employed at anything

but the cheapest common labor and, accordingly, re

sented competition in new and better kinds of work

in which they were just gaining a foothold. Riots

almost as serious as that in Buffalo were reported

in Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Albany, New York,

Brooklyn, and Boston when Negro strike breakers,

brought in to take the places of Irish strikers, were

greeted by floods of bricks, stones, and broken

bottles. During the spring of 1863 rioting between

the two races along the New York water front was

frequent, and injury and death often resulted.

“ In June of that year, shortly before the trouble

in Buffalo, three thousand Irish longshoremen in

New York lost a strike for higher wages largely be

cause of the introduction of black labor under police

protection. A month later these defeated Irish long

shoremen led the draft riots in an attempt to resist

forced military service in behalf of Negroes whom

they feared and hated as their industrial rivals.

“ Despite indications and the fears of the Irish,

the Negro failed to gain a prominent place in long

shore work at this time. In fact, his role along the

water front in New York and the North generally

became less and less important, while the Irish held

their own. They continued to dominate the trade

down to 1887 when the shipping companies in New

York turned to Italians to break the ‘ big strike,’ led

by the Knights of Labor. Several lines also used

Negro strike breakers on this occasion, but let most

of them go when their old men returned. Six years

later, in an extensive strike in Brooklyn, Italians and

Negroes brought from the South were again used as

strike breakers, but it was the former, who had been

1 1

becoming an increasingly important factor in the in

dustry for the past six years, who really broke the

strike. Fights and brawls between the Irish strikers

and Italian scabs took place all along the water front.

At times the situation became so serious as to require

the calling of police reserves. Soon the strike took

on an interracial aspect and became a fight against

the Italians. Every Italian who came near the water

front, even though he had nothing whatever to do

with the strike, was in danger of attack. The fruit

vendors and peanut men who used to ply their trades

along the docks dared not show themselves. In one

instance, according to the newspapers, an Irishman

who was mistaken for an Italian ‘ because he wore a

sloven hat’ was chased for blocks and pounded before

he could explain. Apparently, it is not the Negroes

alone who have suffered as a group because some of

its members have taken the places of men on strike.” 8

More recently, following the disastrous Harlem race riot

of March 19, 1935, the Mayor’s Commission on Conditions

in Harlem as well as private agencies undertook to survey

the condition of Negro labor in New York. One of the re

sults of this effort was a definitive study by Charles L.

Franklin, published in book form in 1936 and entitled “ The

Negro Labor Unionist in New York.” While noting a

numerical increase in Negro unionists in Manhattan from

1,385 in 1910 to 39,574 in 1935, and a corresponding spread

in occupational distribution, Dr. Franklin concludes his

historical and analytical study with this statement:

“ The foregoing facts and conclusions warrant

two further conclusions—of a more general nature.

First, the labor union situation in Manhattan as it

affects Negroes is similar to that in the United States

as a whole. In Manhattan there is represented every

type of labor union relation, practice and policy in

8 Id, at 179-199.

1 2

regard to Negro workers, as was found by investiga

tors (mentioned in the preface) to exist in the United

States. It has already been pointed out above

that these practices vary from acceptance of Negro

workers into membership on an equal basis with

white workers, as in the International Ladies’ Gar

ment Workers’ Union, to a complete exclusion of

Negro workers by constitutional provision as in the

Masters, Mates and Pilots of America, the railroad

Brotherhoods and others. Between those two ex

tremes are the unions that, put Negro workers in

separate locals or in auxiliary bodies responsible to

white unions, those that neither discourage nor en

courage Negro workers to join their ranks and those

organized independently by Negro workers. Just as

the absence of membership or limitations on full

membership of Negroes in unions over the entire

United States produced the net result of their not

being able to gain a prominent position in the indus

trial life of the American people, so did the same

conditions in Manhattan prevent Negro workers

there from gaining a desirable place in the local labor

movement and industrial life. Lack of organization

has deprived them of the means whereby they could

maintain proper standards of living and assure them

selves of sufficient power to combat low wages, de

plorable working conditions, unjust discrimination

and, in general, all forms of injustice. However,

although there is this similarity between Manhattan

conditions and national conditions, there is some

difference in degree. In Manhattan conditions are

not quite so serious as in the United States as a

whole.” 9

Another measure of the social consequences of racial

discrimination by unions controlling large areas of employ

ment is to be found in the disproportionately large part of

the burden of public relief represented by indigent Negroes

9 See Franklin, op. cit. supra note 2, at 266.

13

unable to find work. In the State of New York, according

to the Unemployment Census of 1937, Negroes constituting

3.3 per cent, of the population, constituted 9.4 per cent, of

the unemployed. Out of 320,826 Negroes of employable age,

91,071 wTere unemployed.10 To remedy such a condition

becomes one of the most serious responsibilities of the

State.

The enactment of Section 43 was recommended to the

New York Legislature by the New York State Temporary

Commission on the Condition of the Colored Urban Popu

lation in its Report of February, 1939.11 The Report fully

confirmed and amplified the earlier private findings as to

the widespread existence and hurtful consequences of union

discrimination. The following excerpt is particularly note

worthy :

“ Collective bargaining may be considered in one

aspect a private agreement between an employer and

his employees concerning only the interests of those

responsible for the agreement. In another sense,

however, such an agreement becomes a broader mat

ter and one concerning the general public interest,

for it involves not only wrage levels for the persons"

in question and the standard of living of a portion

of the community, but also, in the case of a closed

shop, even the work opportunities available to those

who are not participants in the agreement.” * * *

“ That many unions are guilty of such unfair

practices especially toward the Negro group, is a

matter of proven fact. It is openly admitted, even

by trade-union leaders, that a considerable number

of international unions exclude Negroes from mem

bership and privileges, either by provision in the

international constitution, or by practices in the

10 Compiled from United States Census of Partial Employment,

Unemployment and Occupations, 1937.

11 Published by the State as Legislative Document (1939) No. 69.

14

ritual of initiation, or by tacit understanding among

their officers.” * * *

“ The Commission has no complete figure showing

the New York State membership of these unions,

but it is sufficiently large and numerous to exercise

an important influence on the policies of organized

labor toward Negro membership.” # * #

“ Refusal of membership to Negroes has been re

ported in many building trade-union locals, where

again no constitutional bar to Negro membership

exists and where discrimination is accomplished

solely on the authority of local officials. Only a

strong revolt on the part of the liberal members of

the painters’ union of New York City broke down a

discriminatory policy which has been practiced to

ward the Negro painters of the city.” * * *

“ It is with these considerations in mind that the

Commission has recommended legislation designed in

some measure to protect workers of minority groups

from unfair discrimination by labor unions.” 12

III.

Reasonableness of Section 43 and Its

Application to Appellant.

It is in this setting and in the light of this history that

the enactment of Section 43 of the Civil Rights Law in 1940

must be considered. Experience had shown clearly that the

avoidance of strife between white and Negro workers and

their partisans, the assurance of greater employment oppor

tunities for Negroes and the utilization of the full produc

tive capacity of the community were important social ob

jectives to which the State must address itself. Legislation

prohibiting labor union discrimination offered one obvious

approach.

12 Id. at 45, 46, 47.

15

The problem existed with reference to all types of

employment within the State. It was not restricted to

enterprise of exclusively local character or to unions of

employees working for private persons. Economic and

social dislocation, local disorders and the impoverishment of

minority groups resulted as much from practices of unions

whose members were engaged in interstate commerce or

employed by government as from the practices of any other

unions. Indeed, the most recent responsible study of union

racial practices shows such unions among the most serious

offenders:

“ At least fourteen American unions specifically

exclude Negroes from membership by provisions to that

effect in either their constitutions or their rituals. . . .

‘ ‘ To summarize the above in tabular form :

“ I. Union which exclude Negroes by provision in

ritual:

Machinists, International Association of

(AFL)

II. Unions which exclude Negroes by provision in

constitution:

A. AFL Affiliates

Airline Pilots’ Association

Masters, Mates and Pilots, National Organi

zation

Railroad Telegraphers, Order of Railway

Mail Association (italics added)

Switchmen’s Union of North America

Wire Weavers’ Protective Association,

American

B. Unaffiliated Organizations

Locomotive Engineers, Brotherhood of

Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen,

Brotherhood of Railroad Yardmasters of

America

Railroad Yardmasters of North America

16

Railway Conductors, Order of

Train Dispatchers’ Association, Ameri

can.13

It is noteworthy in this connection that although appel

lant denies being a “ labor organization” it has voluntarily

become an “ affiliate” of the American Federation of

Labor. Its activity in the field of labor relations, as con

ventionally defined, is noted in the opinion of the Court of

Appeals in the present litigation, and the finding of that

court as to the character of the appellant as a “ labor organ

ization” within the meaning of the New York statute should

be deemed conclusive on this appeal. Moreover, it is stipu

lated in the Record that “ any Appellate Court may con

sider as exhibits offered by defendants

* * * ‘ The Black Worker’ * * * by * * * Spero and * * *

Harris * * # quotations from pages 67-69” (R. 11, 13). The

following significant excerpt is from the evidence thus in

troduced in this case:

“ It appears from the following resolution, adopted

by the Illinois branch of the Railway Mail Association,

protesting against the appointment of a Negro clerk-in

charge at the Terminal Railway Post Office in Chicago,

that the ‘ high mortality rate among Negro Members’

was only a pretext for excluding others in the future:

“ Whereas, a colored clerk has been appointed in

the Chicago, Illinois, Terminal R. P. O., and

“ Whereas, said clerk-in-charge has direct super

vision over thirty-three clerks of Caucasian birth;

and

“ Whereas, this does not create harmonious rela

tions between clerks and clerks-in-charge, nor would

it in any other case similar in character, nor can the

best interests of the service be obtained under such

condition; and

“ Whereas, we believe that no colored clerk-in

charge can supervise the work of clerks of Caucasian

18 See Northrup, op. cit. supra note 2, at 2, 3-4.

17

birth to best advantage, nor to the best welfare of

the employees, therefore be it

“ Resolved, That the Illinois Branch Sixth Divi

sion R. M. A., in regular session assembled vig

orously protest this assignment or any future assign

ment of a (Negro) clerk-in-charge who will have

direct supervision over a crew any of whom are of

Caucasian birth.

‘ ‘ This branch was not unique in its stand. Other

branches protested similar appointments.”

Thus the appellant is revealed not only to be functioning as

a traditional labor organization, but also to be employing

its representative authority and power to induce the officers

of the Postal Service to discriminate against Negroes.

In such circumstances the legitimate and important pub

lic purpose of Section 43 can be achieved only by requiring

appellant to obey its mandate. Appellant’s voluntary acts

have made such application of Section 43 both reasonable

and necessary. Indeed, any exception in favor of appellant

would be arbitrary and unreasonable.

IV.

Trend of Legislation and Adjudication in Other

States as Additional Indicia of Reasonableness.

While not in themselves decisive of the Constitutional

issues raised by appellant, recent legislation and judicial

decisions in states other than New York comprehensively

striking down arbitrary discrimination in membership by

labor unions, strongly indicate that Section 43 is in line with

enlightened judgment throughout the nation as to the social

18

dangers of union discrimination and the propriety and rea

sonableness of its prohibition by state action.14

Chapter 265 of the Kansas Acts of 1941 forbids labor

organizations which exclude persons from membership

because of race or color from acting as a collective bargain

ing representative in that state. Chapter 96 of the Nebraska

Acts of 1941 approaches the problem somewhat differently

by prohibiting representatives of, labor from racial dis

crimination in collective bargaining. Pennsylvania, by

force of Chapter 294 of the Acts of 1937, denies the protec

tion of the State Labor Relations Act to all unions which

restrict membership because of race, creed or color. Chap

ter 57 of the Wisconsin Laws of 1939 requires the termina

tion of any closed shop agreement if the union arbitrarily

restricts membership.

Several State courts have considered it a proper exercise

of judicial power to restrain arbitrary discrimination in

union membership which has damaged a complainant, even

without legislative declaration of policy. The most recent

and carefully reasoned of these decisions, James v. Marm-

ship Corporation, S. F. No. 17,015, was decided by the Su

preme Court of California in January, 1945, but has not yet

been officially reported. Summarizing the views of other

State courts and indicating its own, the California court

there said:

14 Federal policy indicates the same trend in responsible official

judgment. By express provision of Executive Order Number 9346,

dated May 27, 1943, the President has prohibited ‘ ‘labor organiza

tions” in “ war industries” from discrimination in “ union membership

because of race, creed, color of national origin.” During the 78th

and 79th Congresses committees of both Houses reported favorably

on legislaton prohibiting union discrimination which burdens inter

state commerce. See Senate Report No. 1109, 78th Congress, 2nd

Session, and House Report No. 187, 79th Congress, 1st Session.

19

“ Some courts have held that state legislation is

necessary in order to announce a public policy re

stricting a union’s right to arbitrarily exclude in

dividuals from membership although as a result

thereof excluded persons are unable to find employ

ment in their chosen trade. (See for example, Miller

v. Ruehl, 166 Misc. 479, 2 N. Y. S. 2d 394; Murphy v.

Higgins, 12 N. Y. S. 2d 913.) As said hereinbefore,

however, other authorities have indicated that the

courts without statutory aid, may restrain such con

duct by a union on the ground that it is tortious and

contrary to public policy. Further, as said in 4 Re

statement, Torts, page 136, comment on section 794:

‘ The expression of public policy is not confined to

legislation and criminal law; in passing upon the

propriety of an object (of concerted labor action),

public policy otherwise defined is an important factor.

If the object is an act against which the law has

definitely set its face, it is not a proper object of con

certed action. ’ ’ ’

The New Jersey Chancellor, in Cameron v. International

Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees,15 16 17 enjoined the en-

enforcement of union rules, arbitrarily discriminatory

against certain members. The Maryland Court of Appeals,

in Lucke v. Clothing Cutters Assembly,16 approved an award

of substantial damages to a worker arbitrarily denied ad

mission to a union with the consequence that he lost his job.

An Ohio decree, in Wills v. Local No. 106,17 restrained a

union from picketing for the discharge of Negro employees

whose applications for union membership it had arbitrarily

rejected. The American Law Institute, in its Restatement

15118 N. J. Eq. 11,176 Atl. 692 (1935) cert, denied, 298 U. S.

659.

16 77 Md. 396, 26 Atl. 505 (1893).

17 26 Ohio N. P. (N . S .) 435.

2 0

of the Law of Torts, Section 810, has found the law to be

that “ workers who in concert procure the dismissal of an

employee because he is not a member of a labor union . . .

are . . . liable to the employee if, but only if, he desires to

be a member of the labor union but membership is not open

to him on reasonable terms.”

The underlying concept of public policy upon which

courts have proceeded in this entire line of decisions has

recently been stated by the New Jersey Chancellor in Carroll

V. Local No. 269:18

‘ ‘ A voluntary union should be one in which a law-

abiding individual of good moral character, possess

ing the essential qualifications of his trade, can enter

upon compliance with rules and by-laws reasonably

appropriate for the stability and usefulness of the

association. Autocracy is no less inimical to our

American ideals if practiced by many rather than

by one. Since 1890 we have regarded labor unions as

voluntary associations. Let them in reality continue

to be such.”

As the urgent need for governmental restraint of racial

discrimination by labor unions thus impresses itself upon

increasing numbers of State courts and legislatures, the

burden on those who deny that this is a proper State func

tion becomes heavier.

V.

Relation of Section 43 to Federal Authority.

It cannot rationally be argued that employees of the

Postal Service are “ federal instrumentalities,” and cer

tainly it cannot be argued that appellant, a private cor

18 31 Atl. (2d) 223, 225 (N . J. 1943).

2 1

poration, with entity distinct from its members, is such an

instrumentality. Yet, it appears to be appellant’s conten

tion that any regulation of its conduct is an unconstitutional

interference with a Federal function. But this argument

would also strike down State income taxation in its applica

tion to salaries of postal employees, or local traffic regula

tions in their application to postal employees, or State in

surance laws in so far as they might affect mutual companies

insuring postal employees.

The answer to appellant’s contention is to be found in

the settled principle that “ the exercise by the State of its

police power, which would be valid, if not superseded by

Federal action, is superseded only where the repugnance or

conflict is so ‘ direct and positive’ that the two acts cannot

‘ be reconciled or consistently stand together’ ” , as restated

with extended review of earlier authorities by Mr. Chief

Justice H ughes in Kelly v. Washington.19 This Court has

recently applied that principle in Allen-Bradley Local, etc.

v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board,19 20 to a Wiscon

sin regulation of labor disputes admittedly within the area

of Federal control under the National Labor Relations Act,

reasoning that since state and federal regulations “ as

focused in this case can stand together, the order of the

state Board must be sustained under the rule which has

long obtained in this court.”

The application of Section 43 to appellant in this case,

far from impeding any exercise of federal authority, imple

ments federal policy and requirements as declared by the

19 302 U. S. 1, 10 (1937).

20 3 1 5 U. S. 740, 751 (1941). Cf. Carpenters and Joiners Union

v. Ritters Cafe, 315 U. S. 722 (1941) ; Milkwagon Drivers Union V.

Meadowmoor Dairies, 312 U. S. 287 (1940).

2 2

President in Executive Order Number 9346, dated May 27,

1943:

“ I do hereby reaffirm the policy of the United

States that there shall be no discrimination in the

employment of any person in war industries or in

Government by reason of race, creed, color, or na

tional origin, and I do hereby declare that it is the

ditty of all employers, including the several Federal

departments and agencies, and all labor organiza

tions, in furtherance of this policy and of this Order,

to eliminate discrimination in regard to hire, tenure

terms or conditions of employment, or union member

ship because of race, creed, color, or national origin. ’ ’

(Italics added.)

That such policy of the national sovereign is a matter

not of discretion, but rather of constitutional necessity is an

implicit premise of this Court’s decision at the present

Term in Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Ry. Co.,21 and ex

pressly stated in the concurring opinion of Mr. Justice

M u b p h y :

“ The Constitution voices its disapproval when

ever economic discrimination is applied under au

thority of law against any race, creed or color. A

sound democracy cannot allow such discrimination to

go unchallenged. Racism is far too virulent today

to permit the slightest refusal in the light of a Con

stitution that abhors it, to expose and condemn it

wherever it appears in the course of a statutory

interpretation. ’ ’ 22

In such circumstances there can be not even semblance

of conflict between the state and the’ United States as a

result of the application of Section 43 to appellant.

21 65 Sup. Ct. 226 (1944).

22 Id. at 235.

23

*

C o n c lu s io n .

Appellant’s contention that its Constitutional

rights have been infringed is groundless. The

appeal should be dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

W illiam H . H astie,

T hurgood M arsh all ,

L eon A. R an som ,

Counsel for the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People.

E dward R . D udley ,

Of Counsel.

r>-rr>..2i2 [4187]

L a w yer s P ress, I n c ., 165 William St., N. Y . C .; 'P h on e: BEekman 3-2300