Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 31, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1967. 4b1a5c29-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/29f5cb73-908c-48aa-8db2-1d7cbb7b974b/stell-v-savannah-chatham-county-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

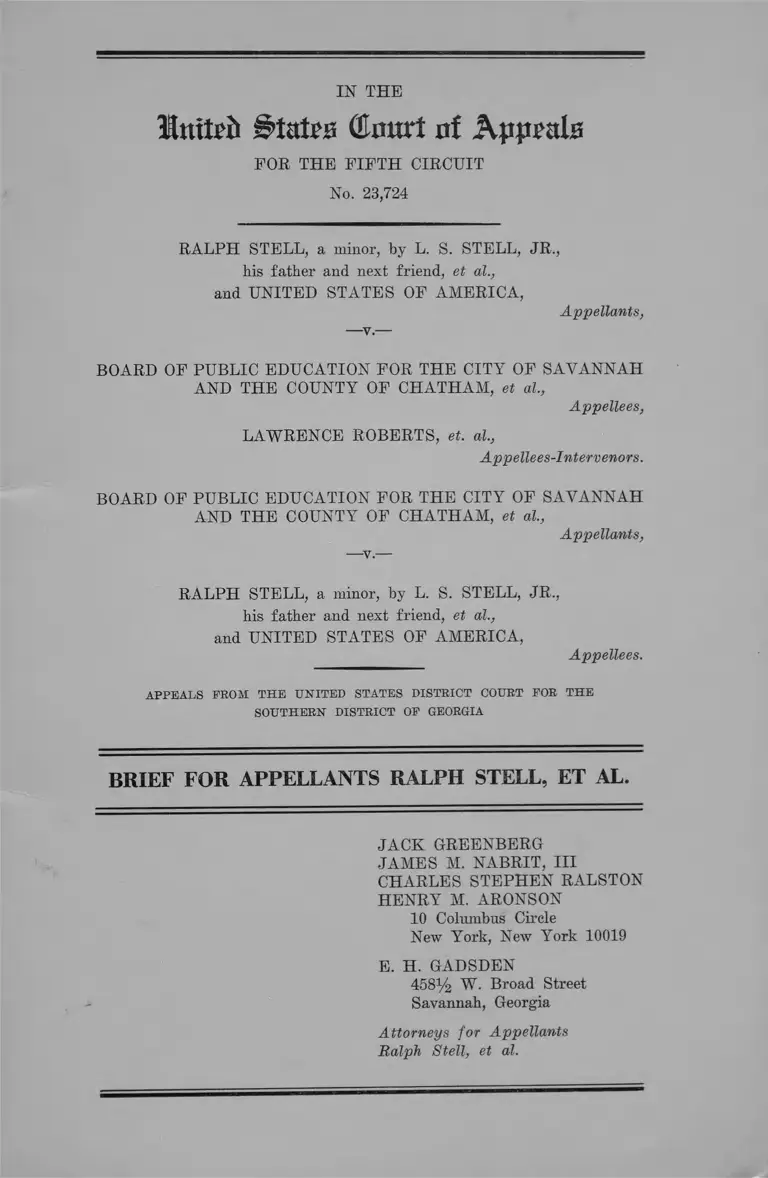

IN THE

Ittitpfc States dnurt nf Appeals

FOR THE FIF T H CIRCUIT

No. 23,724

RALPH STELL, a minor, by L. S. STELL, JR.,

Ms father and next friend, et al.,

and UNITED STATES OF AM ERICA,

Appellants,

— v . —

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF SAVANNAH

AND THE COUNTY OF CHATHAM , et al.,

Appellees,

LAW RENCE ROBERTS, et. al.,

Appellees-Intervenors.

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF SAVANNAH

AND THE COUNTY OF CHATHAM, et al,

Appellants,

— v.-—

RALPH STELL, a minor, by L. S. STELL, JR.,

his father and next friend, et al.,

and UNITED STATES OF AM ERICA,

Appellees.

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS RALPH STELL, ET AL.

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

H ENRY M. ARONSON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. H. GADSDEN

458% W. Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Ralph Stell, et al.

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................. . 1

Specifications of Error ................................ .................... 10

A rgument—

I. The District Court Below Is Required to Enter

a Plan for the Desegregation of the School

System in the City of Savannah and County of

Chatham Which Substantially Complies With

This Court’s Decision in United, States of

America and Linda Stout v. Jefferson County

Board of Education..... ..................... .................... 11

A. The plan entered by the district court failed

in every respect to comply with the require

ments of the Constitution of the United

States and the decisions of the Supreme

Court of the United States and of this Court 11

B. This Court should enter an order directing

the district court to enter an order sub

stantially in accordance with this Court’s

proposed decree in the Jefferson County case 16

II. The White Intervenors Should Be Dismissed

From This Action With Costs and Attorneys’

Fees Because Their Presence Has Unduly De

layed and Prejudiced the Adjudication of the

Rights of the Original Parties to This Action

Within the Meaning of the Federal Rules ...... . 21

Conclusion ............ -..........-.... ...... ................................... 25

Certificate of Service 26

11

T able of Cases

Archer v. United States, 268 F.2d 687 (10th Cir. 1959) 22

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ...............12,14

Carroll v. American Federation of Musicians of U.S.

& Can., 33 F.R.D. 353 (S.D. N.Y. 1963) .................... 22

H. K. Ferguson Co. v. Nickel Processing Corp. of

N.Y., 33 F.R.D. 268 (S.D. N.Y. 1963) ....... ....... ......... 24

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, Va., 304

F.2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) ........... ............ ...................... 14

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Va.,

201 F. Supp. 620 (W.D. Va. 1962), rev’d, 308 F.2d

918 (4th Cir. 1962) ........................................... ........... 14

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg Va.,

203 F. Supp. 701 (W.D. Va. 1962), rev’d, 321 F.2d

230 (4th Cir. 1963) ...................................................... 14

Jones v. School Board of Alexandria, Va., 278 F.2d 72

(4th Cir. 1960) ...................................... ....................... 14

Marsh v. School Board of Roanoke County, 305 F.2d

94 (4th Cir. 1962) ......................................... .......... . 14

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) ....... 14

Roberts v. Stell, 379 U.S. 933 ......................................... 3

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 220 F. Supp. 667 (S.D. Ga. 1963) ...................... 2

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F.2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963) ............................. 2

PAGE

I ll

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964) ......... ........................ 2,14

United States v. Lynd, 301 F.2d 818 (5th Cir. 1962) .... 21

United States of America and Linda Stout, et al. v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, et al., 372

F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966) ............. ..... ............11,16,17,18,

19, 20, 25

Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington County,

Va., 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) .............................. 16

Federal Rules:

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 24(b) .......... 21,22

Other Authorities:

Georgia Educational Directories for 1964-65 and 1966-

67 ............... ........... .................. ...................................... 18

Guidelines for School Desegregation, United States

Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Sec

tion 181.32

PAGE

19

IN THE

Ituttfi Btutm GJmtrt of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 23,724

RALPH STELL, a minor, by L. S. STELL, JR.,

his father and next friend, et al.,

and UNITED STATES OF AM ERICA,

Appellants,

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF SAVANNAH

AND THE COUNTY OF CHATHAM, et al.,

Appellees,

LAW RENCE ROBERTS, et. al.,

Appellees-Intervenors.

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF SAVANNAH

AND THE COUNTY OF CHATHAM, et al.,

Appellants,

RALPH STELL, a minor, by L. S. STELL, JR.,

his father and next friend, et al.,

and UNITED STATES OF AM ERICA,

Appellees.

APPEALS PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OP GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS RALPH STELL, ET AL.

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of Honorable Frank M.

Scarlett, Judge of the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Georgia, requiring the entry of a

desegregation plan with regard to the Board of Public Ed

2

ucation for the City of Savannah and County of Chatham.

The order was entered April 1, 1966.

This action to bring about the desegregation of the

school system of the City of Savannah and the County of

Chatham was tiled in January, 1962 by plain tiff-appellant

Ralph Stell and other students and parents in the City of

Savannah and Chatham County. Subsequent to its tiling,

a motion was made by certain white students and parents,

Lawrence Roberts, et al., to intervene, which motion was

allowed by the district court. At the trial on the merits,

the white intervenors introduced, over the objections of

plaintiffs, voluminous evidence which allegedly went to

prove that Negro students were inherently inferior to

white students. On May 13, 1963, the district court denied

plaintiffs-appellants’ motion for a preliminary injunction

requiring a start in the desegregation of the schools.

Emergency relief was sought from this Court and on May

24, 1963, it directed the district court to enter an order

requiring the school board to submit a plan for desegre

gation not later than July 1, 1963, pending final disposition.

318 F.2d 425, 428.

However, the district court on June 28, 1963, on the

basis of the evidence of the white intervenors, entered an

order dismissing the complaint. 220 F. Supp. 667 (S.D.

Ga. 1963). Subsequently, on June 30, 1963, the district

court refused to approve or disapprove the plan of the

school board submitted pursuant to this Court’s May 24th

order, on the ground it lacked jurisdiction over the matter

while the full appeal was pending. Subsequently, on June

18, 1964, this Court reversed the rulings of the district

court. 333 F.2d 55. In its opinion, the court made it clear

that there could be no basis for refusing to require a plan

to be entered which should bring about the full integration

3

of the public schools in the City of Savannah and Chatham

County.

On July 7, 1964 the plaintiffs, appellants herein, filed

a motion for a judgment in accordance with the opinion

and mandate of this Court (R. 14). In that motion, plain

tiffs also requested that the district court dismiss the in-

tervenors from the action. On August 31, 1964, the de

fendant school board submitted a plan for desegregation

of the schools under its jurisdiction (R. 15-17). Also on

August 31, 1964, the plaintiffs-appellants filed objections

to the desegregation plan (R. 18-20). On September 25,

1964, the district court, upon agreement by all counsel,

entered an order delaying any order and judgment on the

plaintiffs-appellants’ objections to the desegregation plan

on the grounds that the white intervenors had filed a

petition for writ of certiorari in the United States Su

preme Court from the decision of this Court (R. 20-22).

On December 7, 1964, the United States Supreme Court de

nied the petition for certiorari {Roberts v. Stell, 379 U.S.

933).

Subsequently, on January 25, 1965, the plaintiffs-appel

lants moved the court for an order on their objections to

the pending plan filed by the defendant school board (R.

23-24). On March 9, 1965, a hearing was had on the ques

tion of the adequacy of the proposed plan of the defendant

school board (R. 25-117). At that hearing the intervenors

requested the court to again take into consideration the

evidence they had introduced before that allegedly went

to show that Negro students could not adequately par

ticipate in schools with white students. The court agreed

to consider that evidence over the objections of the plain

tiffs-appellants (R. 105-107).

On May 10, 1965, plaintiffs renewed their motion to

dismiss the intervenors, with costs and attorneys’ fees

4

(E. 4-9). The basic ground for the motion was that the

presence of the intervenors in that case had served to

increase the complexity of the original issue of the case,

i.e., whether the public schools were operated on a segre

gated basis. Further, the participation of the intervenors

had and would continue to serve to delay and hinder

judicial supervision of the desegregation of the Chatham

County public schools with all deliberate speed. The plain

tiffs also alleged that the presence of the intervenors had

resulted in a great increase in litigation costs and at

torneys’ fees and would continue to do so in the future

(E. 8-9).

On June 9, 1965, the defendant school board tiled an

amendment to its original and amended desegregation

plan previously tiled in the district court (E. 118). On

August 24, 1965, the district court entered an order on

the plan of desegregation submitted by the defendant

school board (E. 119-30; Second Supplemental Printed

Eecord 1-12). In that order the court again recited various

evidence which allegedly showed that Negroes were of a

lower I.Q. than white students. On the basis of this evi

dence, the court disapproved the plan tiled by the defen

dant school board and the defendants were ordered to

prepare and submit a plan of desegregation that would

assure that integration may be accomplished in such

a manner as to provide the best possible education

for all school children with the greatest benefits to all

school children without regard to race or color, but

with regard to similarity of ages and qualifications

(E. 129).

The court further ordered that the school board should

continue to collect and give effect to test results “so that

race and color as such shall play no part in the assignment

5

of school children or teachers and so that classifications

according to age and mental qualifications may be made

intelligently, fairly and justly” (E. 130). The court failed

to rule on the plaintiffs’ renewed motion to dismiss the

intervenors from the action.

On September 1, 1965, the defendant school board filed

with the district court a motion for a new trial and motion

to amend the judgment (R. 131-36). This motion basically

alleged that the court’s judgment of August 23, 1965, erred

in disapproving the disallowing the plan submitted by the

school board and in requiring the board to present “ an

entirely new Plan based upon intelligence, aptitudes, ages

and qualifications” (R. 133). The board objected to the

order on the ground that to comply with it required a com

plete reorganization of the public school system, a complete

reorganization of personnel, an overwhelming burden on

the school system, and would tend to create discrimina

tions and conflicts among students by segregating them

on the basis of intelligence (R. 134-35). The school board

further alleged that it had been operating under a plan

since July 1963 based upon freedom of choice and hence

under a plan which complied basically with the constitu

tional requirements established by the United States Su

preme Court and by this Court (R. 136). On the same

day, September 1, 1965, the court signed a show cause

order requiring that all parties appear on November 3,

1965 to show cause why the motion of the school board

should not be granted (R. 137-39).

On November 3, 1965, at the hearing, without prior

notice, the intervenors served a copy of a new suggested

order on a desegregation plan which was entirely at

variance with any plans theretofore filed or suggested by

the defendant school board (R. 143). The plaintiffs-appel-

lants requested and were granted an extension of time to

6

permit study of the intervenors’ new plan. On November

9, 1965, the plaintiffs filed their objections to the inter

venors’ new desegregation plan (R. 142-45), alleging that

the plan was “entirely in conflict with the Fifth Circuit’s

orders in this case and any other applicable decisions”

(R. 144). It was further alleged that the plan, if ap

proved, would remove freedom of choice as required by

the decisions of this Court and replace it with a pupil

assignment plan under which pupils would be initially

assigned to segregated schools and/or classrooms, and

under which pupils desiring transfer would be subjected

to “onerous requirements and such transfers would be

subjected to so many tests and subjective standards as

to permit no objective review of the basis for such as

signments” (R. 144). The motion also renewed the plain

tiffs’ motion made in May, 1965 to dismiss the intervenors

and to grant costs and attorney fees against them. The

plaintiffs also moved for further relief, requesting that

the court enter an order requiring a school desegregation

plan in compliance with subsequent decisions of this court

(R. 144-145).

On the same day, November 9, 1965, the United States

of America moved to intervene in the case under the

provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and filed its

objections to the proposed plan for desegregation sub

mitted to the district court on November 3 (R. 139-42).

On January 20, 1966, the United States filed proposed

findings of facts and conclusions of law relating to the

matters in their petition for intervention and in their

objections to the desegregation plan (R. 146-50).

On March 10,1966 the defendant Board of Public Educa

tion filed a copy of a resolution of the Board of Public

Education setting forth the proposed plan of desegrega

7

tion under which the Board would operate for the school

years 1966-67 and 1967-68 (R. 150-170).

On April 1, 1966, the district court entered its order

on the plan of desegregation, the order from which the

present appeals to this Court have been taken (Sup

plemental Printed Record (S.R.) 2-27). The order made

findings of fact, setting out briefly many of the facts

stated above, except that the court found that the counsel

for plaintiffs-appellants filed no objections to the plan

submitted by the white intervenors on November 3, 1965

(S.R. 3). This finding of fact, however, is clearly contra

vened by the record in the case (R. 142-45). In its opinion

the court made extensive conclusions to the effect that

Negroes were inferior in intelligence to whites and that

full and complete integration in the school system would

have a deleterious effect on both white and Negro pupils.

The court therefore ordered that the defendant school

board be enjoined from maintaining in the school system

any distinctions based upon race or color, but the school

board was “enjoined and required to maintain and en

force distinctions based upon age, mental qualifications,

intelligence, achievement and other aptitudes upon a uni

formly administered program” (S.R. 25). The court fur

ther went on to order that no differential be made between

Negro and white school teachers on the basis of their

relative achievement on teacher examinations. Integration

of teaching staff was deferred for a further hearing and

order until the desegregation order was put into effect

(S.R. 26). Except as modified by the order, the revised

plan of desegregation submitted by the white intervenors

was allowed and approved and made a part of the order

(S.R. 27). Thus the actual desegregation plan entered by

the court was that submitted by the white intervenors,

as set out in the Second Supplemental Printed Record

(S.S.R.) at pp. 12 to 18.

8

The plan enjoins the board from making distinctions

based on race or color. It allows the school board to take

into consideration the assignment, transfer or continuance

of pupils within the schools, classrooms and other facili

ties, the choice of the pupil or his parent, the availability

of space, proximity of the school to the residence of the

pupil, and the age and mental qualifications of the pupil

(S.S.R. 12-13). “Where space and facilities are not avail

able for all, priority shall be based on proximity, except

that for justifiable educational reasons and in hardship

cases other factors not related to race may be applied”

(S.S.R. 13). The board was given the authority to es

tablish attendance areas. Assignments and transfers of

pupils were required to be made on forms which would

be available at the Office of the Superintendent of Educa

tion (S.S.R. 14). Applications were required to be signed

by the parent or the legal guardian of the child. Action

on each application was required to be made within 15

days after application was made (S.S.R. 14). If a parent

or guardian had any objection to the determination made,

administrative procedures for hearing such objections were

provided in the plan (S.S.R. 14-16). If the school board

determined from an examination of the record made upon

objections to the assignment of the pupil, or upon an ap

plication for assignment to a designated school that a

pupil is between his “seventh and sixteenth birthdays and

is mentally or physically incapacitated to perform school

duties, or that any such pupil is more than sixteen years

of age and is maladjusted or mentally or otherwise re

tarded so as to be incapable of being benefited by further

education,” the board was authorized to assign the student

to a vocational or special school, or to terminate the

public school enrollment of the student altogether (S.S.R.

p. 16). The plan was amended to include all school grades

for the year 1966-67 (S.S.R. pp. 16-17). Separation of boys

9

and girls in separate classes or in separate schools were

authorized (S.S.R. 17).

The crucial paragraph in the plan is paragraph 14. This

paragraph, which is set out in full in the footnote below,

states in effect that assignments are to be made on the

basis of mental qualifications, “such as intelligence, achieve

ment, progress rate and other aptitudes,” to be determined

on the basis of nationally standardized tests. “No student

shall have the right to be assigned or transferred to any

school or class the mean I.Q. of which exceeds the I.Q. of

the student, nor shall a student be assigned or transferred

to any school or class, the mean I.Q. of which is less than

that of the student, without the consent of the parent or

guardian” (S.S.R. p. 17).1

Plaintiffs-Appellants filed their notice of appeal from

the April 1st order on April 19, 1966 (R. 10-11). The

United States of America and the defendant Board of

Education also filed notices of appeal. Subsequently, the

Board of Education moved this Court for a stay of the

judgment and decree of the district court. This motion

was joined in by the plaintiffs-appellants and by the United

States and was granted by a panel of this Court on June

1 The entire text of paragraph 14 is as follow s:

14. In addition to the criteria hereinbefore set forth, the Defen

dant Board shall in making or granting assignments and/or transfers

take into consideration the similarity of mental qualifications, such

as intelligence, achievement, progress rate and other aptitudes, such

to be determined upon the basis of Nationally standardized tests. No

student shall have the right to be assigned or transferred to any

school or class the mean I.Q. of which exceeds the I.Q. of the student,

nor shall a student be assigned or transferred to any school or class,

the mean I.Q. of which is less than that o f the student, without the

consent of the parent or guardian. New students coming into the

system or moving from one district to another shall be assigned to

their normal neighborhood school. I f a new student is not satisfied

with his school assignment, then his case will be handled as that of

any other student requesting a transfer.

10

7, 1966. The effect of the stay was to leave in full force

and effect the plan of desegregation adopted by the board

on March 8, 1966, and filed in the district court March 10th

(R. 150-170). The plan under which the school board is

presently operating has been set out in the brief on appeal

of the board, together with an affidavit by the Superin

tendent of Schools explaining the present situation in the

schools (Brief for Appellant, the Board of Public Edu

cation for the City of Savannah and the County of Chat

ham, pp. 7-19).

Specifications of Error

1. The court below erred in entering an order requiring

the adoption of a plan of desegregation whose intent and

purpose was to perpetuate the segregation of the races in

the school system of the City of Savannah and the County

of Chatham and which deviated in every material aspect

from the requirements established by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution and the decisions of the

Supreme Court of the United States and this Court.

2. The court below erred in denying plaintiffs-appellants’

repeated motions that the white intervenors be dismissed

from this action and that costs and attorneys’ fees be

awarded against them.

11

ARGUMENT

I.

The District Court Below Is Required to Enter a

Plan for the Desegregation of the School System in

the City of Savannah and County of Chatham Which

Substantially Complies With This Court’ s Decision in

United States of America and Linda Stout v. Jefferson

County Board of Education.

This section of the brief will discuss two questions. The

first is the adequacy of the plan entered by the district

court in its order of April 1, 1966, from which the present

appeal is being taken. The second question deals with the

relief that this Court should grant in light of the plan that

the school system is presently operating under as set out

in the brief filed by the Board of Public Education in this

appeal.

A. The plan entered by the district court failed in

every respect to comply with the requirements of

the Constitution of the United States and the deci

sions of the Supreme Court of the United States

and of this Court.

As may readily be seen by the Statement of Facts above

and by a reading of the record in this case, this litigation

has pursued a long, complex and tortured course. This

has come about by the actions of the white intervenors

who have introduced and reintroduced lengthy testimony

which purports to establish that Negro students are in

herently inferior to white students and therefore the two

groups should not be educated together. The first result

of this evidence was the attempt of the district court

effectively to overrule the decision of the United States

12

Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483.

The second result forms the basis of the present appeal.

The district court below, upon remand by this Court, rely

ing on the same testimony that was rejected by the decision

of this Court, entered a plan whose evident intent was to

hold to an absolute minimum the amount of integration

in the public schools of Savannah and Chatham County.

This order was entered in the face of the opinions of this

Court and in the face of the school board’s attempt to

enter and operate under a freedom-of-choice plan which

complied in many respects with the decisions of this Court.

Instead of allowing the school board to operate under such

a plan, the district court attempted to impose upon the

public schools an entirely different and novel plan which

would require the school board to segregate or group

students according to purportedly objective measurements

of their I.Q.’s.

There are two basic flaws of the district court’s approach.

First, the actual plan it entered had for its purpose and

would have the effect of freezing Negro students in seg

regated schools, as will be demonstrated below. The

second flaw arises from the fact that there is no consti

tutional basis whatsoever for a federal district court re

quiring a school board to group students according to

their I.Q. when the school board has made a judgment

that such grouping wmuld not be in the best educational

interest of its pupils.

The purpose and intent of the district court’s plan is

evident from the court’s reliance, for a second time, on

the evidence introduced by the white intervenors and by

the court’s interpretation of that evidence as showing that

Negroes are inherently inferior to whites and therefore

13

should not be educated with them. The effect of the plan,

if it were allowed to go into operation, is readily apparent

from an examination of it. It is crucial to bear in mind

that the school system lias had a history of white students

being assigned initially to white schools in their attendance

zones and Negro students being assigned to Negro schools

in their attendance zones. Under the plan, a Negro student

seeking to transfer out of the school to which he has been

assigned must go through an onerous and burdensome

administrative process.

Paragraph 14 of the plan, the crucial paragraph, pro

hibits, in effect, the school board from transferring a stu

dent to any school or class “ the mean I.Q. of which exceeds

the I.Q. of the student.” What is apparently meant by the

term “mean I.Q.” is the arithmetical mean or average I.Q.

of all the students in the class or in the school. The

arithmetical mean or average is calculated by adding to

gether the I.Q.’s of all the students in the class for the

school and dividing that sum by the number of students

in the school or class. It is elementary that in any group

so averaged there must be students with I.Q.’s below the

mean, unless the wholly unlikely situation exists where an

entire school or class has exactly the same I.Q. Thus the

plan does not require that no student with an I.Q. below

the average may be educated with students whose I.Q.’s

are at or below the average; quite the contrary. Since

there obviously must already be students in the school with

I.Q.’s below the mean, all the plan does is discriminate

against students who are not already in the school and

who may have I.Q.’s below the mean. It prohibits them

from transferring in even though their I.Q. may be equal

to or above the I.Q. of students already in the school. Of

course, and not surprisingly, the students who would be

attempting to transfer into the school, and who hence

14

might be barred from so doing by the plan, are Negro

students attempting to leave all-Negro schools. Cf., Jones

v. School Board of Alexandria, Va., 278 F.2d 72, 77 (4th

Cir. 1960). It is clear that such a disparity in the treat

ment of Negro students from white students who have

been initially assigned to white schools is not permissible.

Other circuits have struck down similar schemes when they

have been used by school boards. Green v. School Board

of City of Roanoke, Va., 304 F.2d 118, 122-23 (4th Cir.

1962); Marsh v. School Board of Roanoke County, 305

F.2d 94, 96 (4th Cir. 1962); Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d

798, 807-09 (8th Cir. 1961); Jackson v. School Board of

City of Lynchburg, Va., 201 F.Supp. 620, 623-25 (W.D. Va.

1962), rev’d, 308 F.2d 918 (4th Cir. 1962).2

The second and more fundamental defect in the district

court’s approach lies in the court’s assumption that it

could require a school board to group students according

to I.Q.’s. There is nothing whatsoever in the Constitution

or decisions of the federal courts which prohibits a school

board from educating together students of varying I.Q.’s.

The district court’s attempted reliance on language in

both Brown v. Board of Education and in this Court’s

decision in the present case was misplaced. The Brown

decision recognized that a school hoard might make, at

least in a case otherwise free from taint of racial discrim

ination, distinctions between students of different educa

tional ability and age. And, this Court stated in Stell:

In this connection, it goes without saying that there is

no constitutional prohibition against an assignment of

individual students to particular schools on the basis

of intelligence, achievement or other aptitudes upon a

2 For connected decisions in the same case see, 203 F.Supp. 701 (W.D.

Va. 1962), rev’d, 321 F.2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963).

15

uniformly administered program but race must not be

a factor in making the assignments. However, this is

a question for educators and not courts. 333 F.2d at

61-62.

The crucial language in this quote is to the effect that

there is no constitutional prohibition against such assign

ment and that this is a “ question for educators and not

courts.”

It must be kept in mind what this case does and does

not involve. In a situation where the school board itself

has come forward and presented a plan which incorporates

the testing of I.Q.’s and the grouping of students accord

ing to intelligence or other ability factors as a result of

the school board’s own educational judgment, the case

would involve the question of the validity of such an ar

rangement and the duties of a school system -with a prior

history of racial segregation. Such a plan might or might

not be valid depending on its effect and its purpose. (See

cases cited supra.)

This, however, is not such a case. Here, the district

court has attempted to impose such a system on the school

board. The school board, however, has made an educa

tional judgment that it does not want to group students

according to I.Q. Rather, it feels that such a system

would result in feelings of discrimination and tension

between students (R. 134-35). In addition, such a system

would impose great administrative burdens on the school

board (R. 134-36). In the school board’s judgment it de

sires to operate the school in basically the same way

educationally as it has in the past, that is, without group

ing of students according to I.Q.’s. As this Court said

in Stell, such a judgment is for the school board as ed

ucators, and the district court had neither the power nor

16

the right to substitute its educational judgment for that

of the board. See, Wanner v. County School Board of

Arlington County, Va., 357 F.2d 452, 456 (4th Cir. 1966).

The only possible legal basis for the lower court’s judg

ment is that there is some kind of constutional right of

public school pupils to be associated in classrooms and

schools only with pupils whose I.Q.’s are the same as theirs.

There is, however, no such constitutional right, and hence

the court’s order is without legal basis.

B. This Court should enter an order directing the

district court to enter an order substantially in

accordance with this Court’s proposed decree in

the Jefferson County case.

If this were an ordinary appeal from an order of a

district court in a school case, plaintiffs-appellants prob

ably would have filed a motion for summary reversal and

remand for reconsideration in light of this Court’s opinion

in United States and Linda Stout, et al. v. Jefferson

County, et al., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d on re

hearing en banc, March 29, 1967. However, as it has been

demonstrated above, this is in no way an ordinary school

case. Thus, plaintiffs-appellants feel it necessary to dis

cuss the nature of the relief that should be granted and

to urge upon the court the necessity for directing the

lower court to take proper action.

It has been shown that the order entered by the district

court is totally at variance with constitutional requirements

and with the orders and decisions of this Court. How

ever, the school system of Savannah and Chatham County

has never operated under the plan set out by the lower

court. After notices of appeal were filed from the April

1st order, the school board requested this Court for a

stay of that order, which request was joined in by the

17

plaintiffs-appellants and the United States. The stay was

granted, having the effect of permitting the school hoard

to continue to operate under the plan which it had adopted

by resolution on March 8, 1966. The plan as presently

in effect and as presently operating has been set out by

the school board in its brief. The school board urges that

it should be allowed to continue to operate under that

plan and it points out that it is a freedom-of-choice plan

in which all students are required to make choices, and

that under it it is expected that a substantial amount

of desegregation will take place in this coming school

year with 6500 Negro students attending formerly all-

white schools. The school board urges that their plan is

sufficiently in compliance with the Jefferson County decree.

It is the position of plaintiffs-appellants that the Jeffer

son County decision requires that all district courts in

the Fifth Circuit enter decrees that substantially comply

with the proposed decree in that case, unless it is shown

for good reason that variations on the plan are proper.

Plaintiffs-appellants concede that the plan under which

the school board is now operating complies in many im

portant respects with the Jefferson County decree. How

ever, they also contend that there are substantial varia

tions from that decree which may impede the plan’s effec

tiveness in bringing about a totally integrated school

system.

One of the crucial questions concerning the plan con

cerns standards for the determination of choice applica

tions. Although all students are required to exercise a

choice annually, it is not made clear in the plan, as it is

made clear in the Jefferson County decree, precisely what

the criteria are for placing students in schools if not all

students who choose a particular school are able to be

put into it because of overcrowding. Thus, the Jefferson

18

County decree specifies that no preference whatsoever is

to be given students because of their prior attendance in

the school. (372 F.2d at 898.) There is no such statement

in the school board’s plan here, and the absence of such

a statement is a crucial defect. In Paragraph 111(h), cer

tain factors for determining choices are enumerated. Some

of them, such as “ education and courses” of the students,

and “discipline” are not at all clear. Thus, plaintiffs-

appellants feel it is essential that the district court be

ordered to require an amendment of the plan which

clarifies the question of preference and the question of

the criteria for determining choices.

Another substantial question, and one which cannot be

fully explored in this Court but must wait upon a remand,

is that of the attendance zones established by the school

system. The attendance zones and the schools in them

are set out on page 18 of the school board’s brief. In

preparing their brief, plaintiffs-appellants have attempted

to discover, using the Georgia Educational Directories for

1964-65 and 1966-67, issued by the State Superintendent

of Schools, which schools in each attendance area are

formerly all-white and formerly all-Negro. The distribu

tion of such schools, to the best determination of plain

tiffs-appellants, varies considerably from attendance area

to attendance area.3

3 Thus, in Area 1, there are 13 formerly all-Negro schools and 6 for

merly all-white schools. Negro: Bartow; Jackson; Pearl Smith; Butler;

Barnard; Gadsden; Henry; Anderson; East Broad; Hubert; Spencer;

Florence; Thirty-Eighth St. W hite: Massie; Riley; Herty; Pennsylvania

Avenue; Thirty-Seventh St.; Whitney.

In Area 2, the distribution is approximately equal, with 4 formerly

all-Negro schools and 5 formerly all-white schools. Negro: Hodge; De

Renne; Haven; Johnson. W hite: Ellis; Pulaski; Jacob G. Smith; Low;

Thunderbolt.

In Area 3, there are no formerly all-Negro schools and 5 formerly all-

white schools. W hite: Heard; Hesse; Isle o f H ope; White Bluff; Windsor

Forest.

19

Plaintiffs-appellants urge that this Court adopt as the

governing rule concerning such zones the guidelines for

school desegregation of the Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare. Section 181.32 states that:

A school system planning . . . (2) to include more than

one school of the same level in one or more attendance

zones and to offer free choice of all schools within

such zones, must show that such an arrangement will

most expeditiously eliminate segregation and all other

forms of discrimination.

Thus, the validity of the attendance zones here, insofar

as the school board must show that they do not limit the

possibility of free choices by Negro students to transfer

into all-white schools and do not restrict the elimination

of schools with completely Negro student bodies, is a

question that can only be resolved on remand to the court

below and after a full evidentiary hearing.

A reading of the other provisions of the school board’s

plan also shows substantial variations from the Jefferson

County decree. Thus, there is no allowance for students

15 years of age or over or for students in the ninth grade

or above making their own free choice without the need

of the signature of a parent. There is also no requirement

Area 4 comprises 2 formerly all-Negro schools and 6 formerly all-white

schools. Negro: Haynes; Tompkins. W hite: Bloomingdale; Pooler;

Sprague; Port Wentworth; Strong; Gould.

Area 5 contains no formerly all-Negro schools and 2 formerly all-white

schools. W hite: Howard; Tybee.

The attendance areas Nos. 1 and 2 for secondary schools each comprise

an equal number of formerly all-Negro and all-white schools. Attendance

A rea 1.— Negro: Tompkins; Scott. W hite: Groves; Mercer. Attendance

Area 2 — Negro: Beach Senior; Cuyler; Beach Junior; Hubert. White:

Savannah High; Chatham; Shuman; Wilder.

Attendance Area 3 for secondary schools consists of 1 formerly all-

Negro school and 5 formerly all-white schools. Negro: Johnson. White:

Jenkins; Myers; Bartlett; Savannah High; Windsor Forest.

20

for publication of the notice and for the mailing of it and

choice forms to all students in the school system. The

provision for transportation is not as detailed as the

one in the Jefferson County decree, and there are no provi

sions prohibiting harassment or requiring the school board

to act against harassment that occurs.

The provision as regard to faculty and staff is clearly

inadequate when compared to the Jefferson County decree.

It only provides that shifts in faculty shall be made when

vacancies in the faculty of the existing school occur. The

desegregation of faculty planned for the school year

1967-68 involves only supervisory and administrative per

sonnel and special teachers. There is no desegregation

of regular classroom teachers. The Jefferson County

decree requires much more; i.e., the affirmative assign

ment of school teachers at the present time regardless

of present assignments in order to bring about immediate

faculty desegregation for the coming school year. (372

F.2d at 900.)

There is a total absence in the plan of provisions for

the equalization of school facilities, for the examination

of construction of new schools and for periodic reports to

be made to the court and to opposing counsel on the

progress of the school plan.

In view of these substantial deviations from the Jeffer

son County decree and in view of the history of the litiga

tion in this case, plaintiffs-appellants urge that this Court

must not merely reverse the decision of the court below

but direct it to enter an order requiring the adoption of

a plan for desegregation in substantial compliance with

the Jefferson County decree, allowing only such variations

as may be required, on a showing of the school board,

21

because of particular circumstances that may exist in the

Savannah-Chatham County school system.

II.

The White Intervenors Should Be Dismissed From

This Action With Costs and Attorneys’ Fees Because

Their Presence Has Unduly Delayed and Prejudiced

the Adjudication of the Rights of the Original Parties

to This Action Within the Meaning of the Federal Rules.

On three occasions the plain tiff s-appellants moved the

district court to dismiss the white intervenors, Lawrence

Roberts, et al., from this action on the grounds that they

had only served to complicate the issues in the case and

to cause substantial delays in the district court’s render

ing the decision required by the Constitution and the de

cisions of the federal courts (R. 14, R. 4-9, R. 144). Al

though there is nothing in the record to show an express

denial of the motions, the court’s failure to rule on them

was in effect a denial. See, United States v. Lynd, 301

F.2d 818 (5th Cir. 1962).

Although plaintiffs-appellants have not found any case

which specifically deals with the question o f a later dis

missal of parties who have been allowed to intervene

under Rule 24(b), the permissive intervention provision

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, they contend

that the Court does have the power to subsequently dis

miss such an intervening party where it clearly appears

that they have only served to “unduly delay or prejudice

the adjudication of the rights of the original parties,”

F.R.C.P. 24(b). Thus, this Court should apply the same

standards as would be applied in reviewing the initial

22

allowance or denial of a motion to intervene under Rule

24(b).4

An examination of the record in this case, as set out in

the statement of the case above, demonstrates conclusively

that the only function that the intervenors have performed

has been to delay, by years, the entry of an order as re

quired by law in this action. The action was filed in Janu

ary, 1962. At that time the issues were clear-cut; that is,

it was an action between Negro students who were denied

the constitutional right to be taught in desegregated

schools, and the school board responsible for the mainte

nance of segregated schools. The intervention of Lawrence

Roberts, et al., who purported to represent the interests

of white students in the schools, was allowed by the dis

trict court in that year. Action on the complaint and

motions for injunction of the plaintiffs was delayed in

order to allow the white intervenors to introduce lengthy

evidence purporting to show the inferiority of Negro

pupils to white pupils. The result of this was the denial

of all relief to the Negro plaintiffs and the dismissal of

their action by the district court. This necessitated an

emergency appeal to this court for an order requiring the

district court to have the school board file a plan for

desegregation. Despite the mandate of that court, the dis

trict court failed to rule on the adequacy of the plan filed

by the school board and the plaintiffs’ objections to that

plan because of the pending appeal in this Court.

This Court handed down its opinion in May of 1964

remanding the case, with directions for an entry of a plan

of desegregation. The plaintiffs then moved for an order

in compliance with this Court’s mandate in the district

4 See, Archer v. United States, 268 F.2d 687, 690 (10th Cir. 1959);

Carroll v. American Federation of Musicians o f TJ.S. & Can., 33 F.R.D

353 (S.D.N.Y. 1963).

23

court. Action on that motion was further delayed because

the white intervenors had filed a petition for certiorari

in the United States Supreme Court challenging this

Court’s decision. After the Supreme Court denied the

petition for certiorari late in 1964, plaintiffs renewed their

motions for an order on the school plan. The school board

filed a proposed plan and plaintiffs made appropriate

objections to it.

At the hearing on the school board’s plan the white in

tervenors again reintroduced the evidence that they had

introduced previously despite the decision of this court

and denial of certiorari by the United States Supreme

Court. As a result of this evidence, the district court again

failed to rule on the plaintiffs’ motion, but instead, relying

on the intervenors’ evidence, rejected the school board’s

plan and required it to enter a plan which would distin

guish between pupils on the basis of their intelligence.

The school board filed objections to this order and a motion

for new trial, raising objections to the order and urging

that the school board was attempting to implement a

freedom-of-choice plan in conformity to the opinions of

this Court.

At the hearing on the school board’s motion, the white

intervenors, for the first time, filed a completely new plan

which was at variance with the opinions of this Court, as

discussed above. This required the plaintiffs to make ob

jections to the new plan, which they did. At the same time

they renewed their motion to dismiss the intervenors and

moved for further relief for an entry of a plan that would

be in conformance with opinions of this Court. The district

court ignored the motion of the plaintiffs and indeed found

that no such motion had been entered. Rather, on April 1,

1966, it entered the order now appealed from which ap

proved the plan filed by the white intervenors. This order

24

necessitated the present appeal and indeed resulted in a

situation perhaps unique in school litigation, i.e., an appeal

from the order not only by the Negro plaintiffs and the

United States of America, which had in the meantime inter

vened under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, hut hy the

school hoard itself.

Thus, at the present time, five years after the initiation

of the litigation hy the plaintiffs-appellants there has yet

to be entered by the district court an order granting the

relief which the plaintiffs are clearly entitled to under law.

This delay, the repeated appeals, and the complexity of

the case have resulted solely because of the white inter-

venors. The school board itself wishes to carry out a plan

of desegregation according to what it believes are the

requirements of the Constitution and the decisions of this

Court. It is true that it is presently operating under a

plan, but, as stated above, plaintiffs-appellants have made

objections to prior plans and have objections to the present

one. The resolution of these issues, the only ones legiti

mately present in this action, has been prevented because

of the continued attempts, successful to date, of the white

intervenors to interject issues which are irrelevant, which

were decided against them in 1954 by the Supreme Court

of the United States and which have had the purpose and

intent of preventing or minimizing the desegregation of

the school system of the City of Savannah and the County

of Chatham. Cf., II. K. Ferguson Co. v. Nickel Processing

Corp. of N.Y., 33 F.R.D. 268, 275 (S.D.N.Y. 1963). Of

course, this has resulted in the multiplication of the costs

of plaintiffs-appellants and in otherwise unnecessary ex

penditures of considerable time and effort by many

attorneys.

Thus, it is clear that the participation of the white in

tervenors has served solely to delay and prejudice the

25

adjudication of the rights of the original parties, that is,

the Negro plaintiffs and the school board. For this reason,

it is appropriate in this case for the Court to enter an

order dismissing the white intervenors from the action or

at least to assess all costs of the action, together with

reasonable attorneys’ fees, against them.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the decision of the court

below must be reversed and the cause remanded with in

structions to enter a plan in conformance with this Court’s

opinion and decree in the Jefferson County case and to

dismiss the white intervenors, Lawrence Roberts, et al.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen R alston

H enry M. A ronson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. H. Gadsden

458% W. Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Ralph Stell, et al.

26

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that the undersigned, one of the at

torneys for appellants, served a copy of the foregoing

Brief for Appellants upon Basil Morris, Esq., P.O. Bos

396, Savannah, Georgia, and Honorable E. Freeman

Leverett, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, State of

Georgia, Elberton, Georgia, attorneys for appellees; R.

Carter Pittman, Esq., P.O. Box 891, Dalton, Georgia, and

J. Walter Cowart, Esq., 504 American Building, Savannah,

Georgia, attorneys for appellees-intervenors; and Frank

M. Dunbaugh, Esq., Department of Justice, Washington,

D.C., attorney for appellant United States of America, by

mailing copies to them at the above addresses via the

United States air mail, postage prepaid.

Done this day of May, 1967.

Attorney for Appellants

Ralph Stell, et al.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219