Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation and United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 12, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation and United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO Brief Amicus Curiae, 1977. d49affcd-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/29fbd1ac-de50-4386-84b3-2bea9ac69fb6/weber-v-kaiser-aluminum-chemical-corporation-and-united-steelworkers-of-america-afl-cio-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

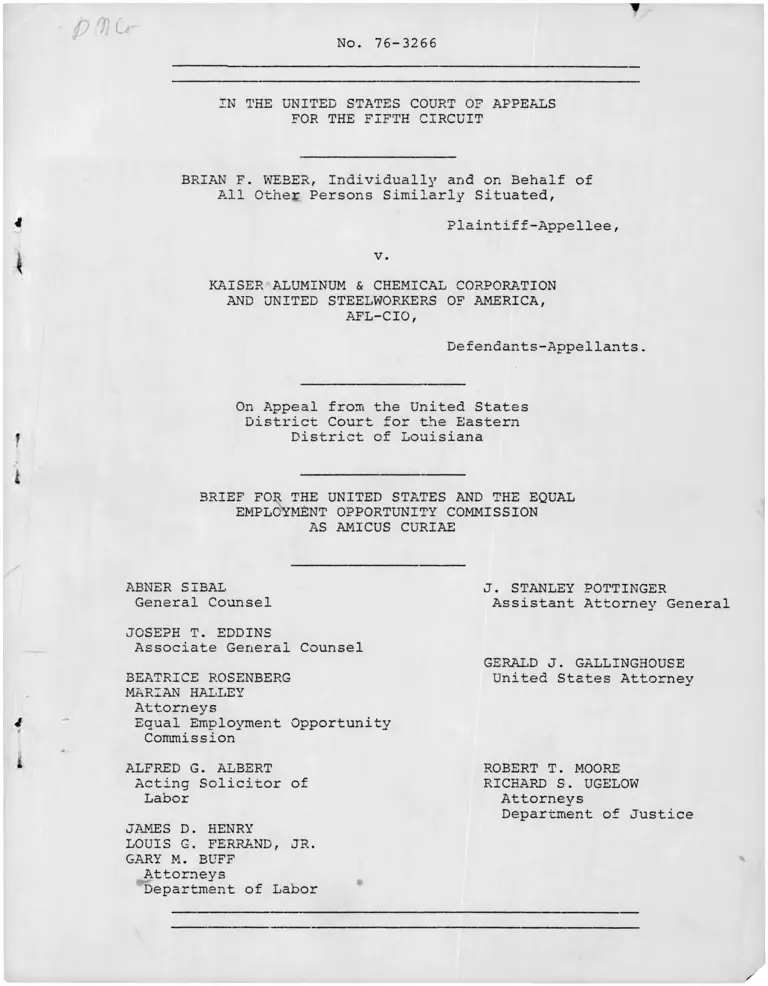

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIAN F. WEBER, Individually and on Behalf of

All Other Persons Similarly Situated,

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION

AND UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO,

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Eastern

District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AND THE EQUAL

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Plaintiff-Appellee

v

Defendants-Appellants.

ABNER SIBAL

General Counsel

J. STANLEY POTTINGER

Assistant Attorney General

JOSEPH T. EDDINS

Associate General Counsel

BEATRICE ROSENBERG

MARIAN HALLEY

Attorneys

Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission

GERALD J. GALLINGHOUSE

United States Attorney

ALFRED G. ALBERT

Acting Solicitor of

Labor

ROBERT T. MOORE

RICHARD S. UGELOW

Attorneys

Department of Justice

JAMES D . HENRY

LOUIS G. FERRAND, JR.

GARY M. BUFF

Attorneys

Department of Labor

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ISSUE PRESENTED................................... 1

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES AND THE EQUAL

* EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION .............. 2

STATEMENT ......................................... 3

Facts of the C a s e ............................... 3

Opinion of the District Court.................. 12

A R G U M E N T ......................................... 13

Issue and Summary.............................. 13

A. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLANS REQUIRED BY

EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246 AND ITS IMPLE

MENTING REGULATIONS DO NOT VIOLATE

* TITLE VII OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF

1964 16

1. Affirmative Action Plans adopted

pursuant to Executive Order 11246

have been approved by the Courts........ 19

2. Affirmative Action Plans, including

Goals and Timetables, implemented to

comply with Executive Order 11246

have been approved by Congress.......... 25

3. Defendants' voluntary efforts at meeting

the requirements of Executive Order 11246

were in accordance with contemplated pro

cedures ................................. 31

B. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN CONCLUDING THAT

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLANS EMBODIED IN CONSENT

/ AGREEMENTS WHICH DO NOT CONTAIN ADMISSIONS OF

DISCRIMINATION AND/OR ARE NOT JUDICIALLY

SANCTIONED VIOLATE TITLE VII ................ 34

Page

C. ANY ALTERATION OF PLAINTIFFS' SENIORITY

EXPECTATIONS WHICH HAS OCCURRED HERE

BECAUSE OF COMPLIANCE WITH EXECUTIVE

ORDER 11246 IS LAWFUL............................ 39

CONCLUSION................ .. ....................... 42

22, 24, 35

Jersey Central Power and Light Co. v.

I.B.fi.W" 508 F . 2d "687 (3d Cif“ 1975) ,

vacated, 425 U.S. 987 (1976), 542 F.2d 8(3d Cir.

1976) ("on remand from S.Ct.)..................

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, 431 F.2d 245

(10th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S.

954 (1971) .....................................

Joyce v. McCrane, 320 F. Supp. 1284

(D.C. N.J. 1970) ............................

Kirkland v. New York, 520 F.2d 420 (2d Cir. 1975),

cert, denied, 97 S.Ct. 73 (1976) ..............

Local 12, Rubber Workers v. N.L.R.B._,

368 F.2d' 12 (5th Cir. 1966) . . ...............

Local 53 Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047 (5tK cir. 1969)"~~........................

Local 189, United Papermakers v. United States,

416 F .2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied,

397 U.S. 919 (1970) ..........................

Maryland Casualty Co. v. United States, 251

u.s. 342 ( i92o) r r .......................... ......................

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency,

395 F.2d 920 (2d Cir. 1968) . . . . • .

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974) . . .

Offermann v. Nitkowski, 378 F.2d 22

(2d Cir. 1967) . .............................

Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers'

Union, 514 F.2d 76'7""(2d Cir. 195) T T T . . .

Porcelli v. Titus, 302 F. Supp. 726 (D. N.J.

— 1969')': aff 'd;~"431 F . 2d 1254 (3d Cir.

1970) .........................................

Sanders v. Dobbs House, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948

(1971) .......................................

Southern Illinois Builders Association

v"! Ogilvie, 327 F . Supp. 1154 (S. D . 111.

1971) 7 aff1d 471 F.2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972) . . .

37

15

24

26

23

18

18

20

23

20

23, 41

20

26

15, 20

TABLE OF CASES

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 4'05 (1975) 7 ................................... 34, 37, 38

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415

U.S. 77 (1974) ............ ........................ 26, 37

Associated General Contractors

of Massachusetts, Inc. v~

Altschuler, 490 F .2d 9 (1st Cir.

1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 ( 1 9 7 4 ) .......... 15, 21

Page

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir.

1972) , cert. denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972).......... 23

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 534 F.2d

77T"(2d Cir. 1976) . . ............................. 21, 24

Contractors Ass'n of Eastern Pa. v. Shultz,

442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 854 (1971) .............................. 14-16, 18, 20,

26, 28, 29, 33

E.E.O.C. v. American Telephone and Telegraph

Co. ;” 5l9 F.Supp. 1022 (E.D. Pa.

1776) ............................................................................................................... 20, 21

E.E.O.C. v. Mississippi Baptist Hospital, 11

EPD [CCH] U 0 , 822 (S.D. Miss. 1976) ................. 35

E.E.O.C. v. N.Y. Times Broadcasting Service,

Inc'.", 542 E.2d 356 (6th Cir. 1975) . T 7 ........ 38

Emporium Capwe11 v. Western Addition Community

Organization, 420 U.S. 573 (1975) ! ! ! ! • ........ 15, 35, 40,

— 41

Farkas v. Texas Instruments Co., 375 F.2d 629

(TtK Cir. 1967), cert, denied,' 389 U.S.

977 (1967)......................................... 18

Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345 U.S. 330

(1953) 7 " ~ ......................................... 39, 41

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. 747 (1976) . . . ............ 15, 37, 39

Gates v. Georgia Pacific Corp., 492 F.2d 292

(7th Cir. 1974) . . . . . 7 ........................... 40

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

“ 7X771) 7— 7 — — ............................ 38

14, 16, 36,

37, 38, 41

41

4

United States v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries,

et aTT> 317 F . 2d 82? (3th Cir. 17737;

cert, denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976) . . . .

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F. 2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971)........ .. . . .

United States v. City of Jackson, 519 F.2d

1147 (5th Cir. 1975) . . . . . ..........

United States v. International Union of

Elevator Constructors, Local Union No. 5, 538 F.2d 1012 (3d Cir.' 1976) . . . .'T- .

United States v. Mississippi Power and Light

Co., 9 EPD [CCH] 110,164 (S.D. Miss. 1975)

United States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973).......... ............

United States v. New Orleans Public Service,

Inc., 8 EPD [CCHJ \9795 (D.C. La. 1974) .

United States v. United States Steel Corp.,

371 F. Supp. 1045 (N.'b. Ala. 1973), reversed

on other grounds, 520 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1775),

cert, denied, 97 S.Ct. 61 (1976) ..............

Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 (1967) ..............

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 502 F.2d 1309

(7th CirT 1974), cert, denied, 97 S.Ct. 2214

(1976) .........................................

Watkins v. United Steelworkers of America,

Lo'caT 2369, 516 F.2d 41 (5th Cir. 19 75)." . . . .

36

20, 30

18, 21

34, 37

18

41

41

22, 24

21, 22, 23,

24

/

The Federal Civil Rights Employment Effort - 1974

Volume 5, To Eliminate Employment Discrimination,

United States Commission on Civil Rights ............ 31

Legislative History of The Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972 ............................ 30

CCH Employment Practices Guide ........................ 35

STATUTES AND OTHER AUTHORITIES

Page

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 , as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et. s e g ........... Passim

Section 703, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 ........................ 20, 21, 24,

29, 39

Section 706, 42 U.S.C. 2 0 0 0 e - 5 ........................... 35

Section 709, 42 U.S.C. 2 0 0 0 e - 8 ........................... 26

Section 715, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-14 ........................... 30

Section 718, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-17 .......................... 30

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,

Public Law 92-261 ...................................... 26

Executive Order 11246 .................................. Passim

Section 202 .............................................12, 18

Section 207 .............................................. 33

Section 209 .............................................. 32

The Secretary of Labor's Regulations Implementing

Executive Order 11246 (Title 41, Code of

Federal Regulations, Part 60-1 et. seg.) ............ Passim

41 CFR §60-1.24 .......................................... 32

41 CFR §60-1.40 ....................................... 26

41 CFR § 6 0 - 2 ............................................ 19

41 CFR §60-2.10.......................................... 19

41 CFR §60-2.14.......................................... 26

110 Cong. Rec. 13650 (1964).............................. 26

118 Cong. Rec. (1972)

Pages:

1385 ...................................... 27

1387-1398 27

1398-1399 29

1664 ...................................... 28

1665 .................................... 28, 29

1676 ...................................... 28

3367-3370 28

3371-3373 28

3372 ..................................... 28

3959-3865 28

122 Cong. Rec. S.17320 (daily ed. Sept. 30, 1976) . . . . 19

42 Fed. Reg. 3454 (1977) 26

35 Fed. Reg. 2586 (1970) 26

employment practices followed by the Company. The parties

stipulated that "substantially all maintenance and craft

personnel employed at Kaiser Gramercy Works were obtained by

hire of persons qualified and trained in such crafts prior

to employment by Kaiser" and that "[t]he available supply

of trained craft and trade personnel available for hire by

the Company as new employees has been, and remains to the

present time, almost entirely made up of white males" (App.

_3/196) .

While maintaining requirements less stringent than

already being fully craft trained and experience require

ments, other Company employment practices pertaining to

craft jobs also had an adverse effect upon minorities.

Two limited on-the-job training programs had been maintained

by Kaiser at Gramercy prior to 1974 and a total of 28 per

sons had been trained, of whom only two were blacks (App.

196-197). One training program, started in 1964 for the

carpenter-painter craft, required one year of prior experi

ence gained outside the Gramercy plant as a condition for

entry (App. 196). The other program, started in 1968 for

the general repairman craft, required three years of

3/ In recognition of the desirability of craft jobs, it

was also stipulated that the "[play rates for crafts are in

general higher than a majority of other jobs at the plant

. . . and such jobs are considered desirable and advantageous

for financial, job security and other reasons" (App. 199).

5

(non-Kaiser) experience up until 1971, at which point the

requirement was relaxed to two years of prior experience

(App. 197). Openings in both programs were filled on the

basis of plant seniority from among qualified bidders

(App. 196-197).

The seniority factor, however, was not the root cause of

the limited minority participation in the programs. Rather,

it was the prior experience requirement. In fact, by 1974,

there remained virtually no non-craft employees in the

plant, of any race, with sufficient qualifying craft experi

ence for entry into either program (App. 115). In 1974

alone, 22 new craftsmen (21 of whom were white) were hired

"through the front gate" for lack of qualified incumbent

employees who could qualify either directly for craft

positions or for the training program leading to craft

positions (App. 103, 112). This effective denial of these

positions and programs to Kaiser employees, whatever their

race, was of concern to the USW (App. 115). More importantly,

however, this resulting reliance on "outside" training and/or

experience had the effect of carrying into Kaiser's craft

positions the product of historical discrimination within

the non-industrial sources of craft training and experience.

Kaiser's industrial relations superintendent testified

that the Company had attempted to hire fully experienced

blacks into all craft categories, but had not been success

ful, even though it had used all available recruitment means

6

such as advertising in minority newspapers and keeping separate

affirmative action files (App. 99, 103-104). A similar lack

of success had been had in obtaining partially experienced

blacks in any numbers for the two training programs (App. 110,

115). The superintendent further testified to a recognition

that blacks lacked craft training and experience because

they had been discriminatorily denied entry into the building

trades unions' programs where such training and experience

was generally gained (App. 100) . It was also the observation

of Kaiser's national director of equal opportunity affairs

that the statistical absence of minorities and females

from the craft field was "a direct result of employment

discrimination over the years, the lack of opportunity on

the part of the blacks in some areas of the community,

Mexican-Americans, certainly, women, to obtain the kind

of training that was necessary to achieve the skills"

(App. 142).

Both Kaiser's national director of equal opportunity

affairs and its industrial relations superintendent testified

that Government officials, through the Executive Order 11246

program, had asked the company to correct the lack of

minorities in the crafts (App. 99, 121, 145-146, 148). The

director of equal opportunity affairs explained (App. 145-

146) :

I don't think I have sat through a compliance

review where it wasn't apparent that there

7

were few, if any, minorities in the craft

occupations, and that there was always, cer

tainly, the suggestion, on the part of the

compliance review officers, that we devise

and come up with methods and systems to

change that particular thing.

The Company's industrial relations superintendent also

testified as to the concern about avoiding Government and

private litigation, and the possibility of substantial back

pay awards and court imposed seniority remedies to which

the Company and Union might have limited input and resulting

difficulties adjusting to (App. 130-132).

It was in this factual context that the defendants,

through the collective bargaining process, established

the affirmative action plan for craft occupations at the

Gramercy plant. On the basis of the available workforce

for the area, the plan established an eventual goal of 39%

minority and 5% female for each of four craft groupings

(App. 95; Kaiser Ex. 1), with an implementing ratio of one

minority or female for each white male selected for future

craft vacancies (App. 117-118; Joint Ex. 2). To insure

that meaningful results would be obtained in light of the

scarcity of minorities and females with prior craft experience,

the plan provided for a new on-the-job training program for

which prior experience was not a prerequisite (App. 100),

with the duration of the training being from 2 1/2 to 3 1/2

years, depending upon the craft category (App. 106). The

8

elimination of all prior experience requirements also satis

fied the legitimate USW objective of increasing craft oppor

tunities for its members in preference to new hires (App.

115). The cost of the program to Kaiser was estimated at be

tween $15,000 and $20,000 per year per trainee (App. 107).

The application of the plan at the Gramercy plant

resulted in the filling, after posting for bid on a plant

wide basis (App. 197), of thirteen training vacancies lead

ing to six crafts, with seven being filled by black employees

and six by white employees (App. 117; Kaiser Ex. 2). Where

more than one vacancy was posted at the same time, selec

tion was made on an alternating basis between the most

senior black and white employees bidding (App. 116). On

two occasions, single vacancies were posted. In order to

maintain the 50% objective, one was filled from among white

bidders only and the other from among black bidders only

_4/

(App. 117). It was stipulated that in each instance,

except for the vacancy limited to white employees, the

successful black bidders were junior in plant seniority

to one or more of the unsuccesssful white bidders (App.

198) .

4/ The plaintiff and another white employee testified that

whites were excluded from bidding on the vacancy filled by a

black (App. 56-57, 88). However, there was no limit on whom

could bid on the vacancy in question (for Insulator Trainee)

as is evidenced by the bid records revealing 13 white and 7

black bidders (Joint Ex. 3). Furthermore, the Supplemental

Memorandum to the 1974 Labor Agreement provided for the

selection of a white had there been "insufficient available

qualified minority candidates" (Joint Ex. 1, pp. 164-165).

9

Because of the low numbers of blacks hired into the

plant between its start-up in 1957-58 and the Company's

adoption of an affirmative action hiring plan in 1969 (see

p. 4, supra), the defendants recognized that without the one-

for-one selection ratio, and on the basis of time in the plant

only, "there would be very few blacks that would get into any

of the crafts for quite a while" (App. 113). Because of the

previous total exclusion of females (App. 105), the same

reasoning and conclusion is equally applicable to females.

In all other respects, the regular Labor Agreement

provision on employee selection controlled the filling of

the training vacancies in issue. That provision provides

that, as between competing employees, the factors to be

considered in addition to seniority are (a) ability to

perform the work and (b) physical fitness (Joint Ex. 1,

p. 57). There was no evidence, or suggestion, that any

unsuccessful bidder had greater ability or was more

physically fit to undertake the on-the-job training offered

than the successful black bidders.

The plaintiff alleged that the use of the 50% ratio to

fill the craft training vacancies violated Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 because it established "a quota

system which illegally discriminates against non-minority

members of the Kaiser Gramercy labor force. . ." (App. 206).

A plaintiff class was certified pursuant to Rule 23(b) (2),

10

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, consisting of all

Gramercy plant employees who "are not members of a minority

group and who have applied or were eligible to apply for on-

the-job training programs since February 1, 1974" (App. 207).

At trial, plaintiff testified, and the bidding records

revealed, that of the three posted vacancies he had bid on,

one was filled by a minority employee with less plant ser

vice than he possessed (App. 76-77; Joint Ex. 3). It was

undisputed, however, that' if the vacancies had been awarded

on the basis of seniority alone, he (Weber) would not have

been the successful bidder with regard to any of them (App.

72, 138; Joint Ex 3). Another white employee testified that

despite his 16 years of plant service, he had been an unsuc

cessful bidder for three posted vacancies which were awarded

to blacks with less seniority (App. 87). Neither of these

white employees had been eligible for full craft status

or for the pre-1974 on-the-job training programs since

they both lacked the then required prior experience (App.

82, 89, 90). In this regard, the plaintiff conceded

that the defendants' 1974 collective bargaining agreements

had opened previously closed craft opportunities for all

Kaiser employees (App. 82, 90).

In the preamble to their Memorandum of Understanding

creating their voluntary affirmative action plan, the

11

Company and Union declared that in adopting such a plan

they were not admitting any previous discrimination in

violation of either Title VII or Executive Order 11246

(Joint Ex. 2). At trial, Kaiser's director of equal

opportunity affairs refused to state that the defendants

had engaged in any prior discrimination against blacks

and testified that he knew of "no specific evidence of

discrimination" at the Gramercy plant (App. 169). The

industrial relations superintendent made a similar denial

and stated the Company's belief that it had not "discrimi

nated inside [the] plant" (App. 122, 128). Both Company

officials also testified that the blacks entering craft

training under the 1974 agreements were not selected be

cause they were known to be victims of specific acts of

past discrimination (App. 128, 154-157). However, the

Company did recognize them to be victims of general

societal discrimination (App. 161-163, 168).

Opinion of the District Court

The district court ruled that the affirmative action

provisions of the collective bargaining agreements implemented

at the Gramercy plant violated Sections 703(a) and 703(d) of

Title VII because they unlawfully discriminated against

white employees on the basis of their race (App. 213). The

district court acknowledged that affirmative action plans

12

could lawfully be ordered by courts. The court reached

this conclusion, however, on the ground that Sections

703(a) and 703(d) "do not prohibit the courts from dis

criminating against employees by establishing quota

systems where appropriate. The proscriptions of the

statute are directed solely to employers" (emphasis

added) (App. 216). The court concluded that no matter

how laudable the defendants' objectives, in the absence

of evidence of prior discrimination and judicial

approval, the court's reading of that portion of the

legislative history of Title VII which it believed

relevant precluded an affirmative action plan from

being lawful. Moreover, the district court was of the

opinion that because the minority and female employees

who benefited from the affirmative action plan had not

been individually and specifically the victims of dis

crimination, it would not be appropriate for a court to

order goals in the context of this case (App. 216-219).

ARGUMENT

Issue and Summary

This case raises the question of whether parties to a

collective bargaining agreement can take voluntary corrective

action to remedy an underutilization of minorities and females

13

in craft jobs and thus comply with the requirements of

Executive Order 11246, as amended, without violating Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The affirmative action plan challenged herein was

designed to correct the virtual exclusion of minorities

and females from highly desirable craft jobs at Kaiser's

Gramercy plant. It is a plan that not only made newly

created craft training opportunities available to

minorities and females on an accelerated basis, but also

made such opportunities available for the first time to

most of the white male incumbents, including the plaintiff.

The instant plan does not require the selection of a less

qualified employee over more qualified employees. Until

the craft positions reflect the surrounding workforce,

it does call for the filling of one half of the training

vacancies with either minorities or women, to the extent

there are sufficient qualified minorities and females

available. In this regard, the provisions of the instant

affirmative action plan are similar to those contained in

the nationwide steel consent decree which were approved

in United States v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries, et al.,

517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 944

(1976).

The lawfulness of affirmative action programs similar

to that challenged herein and adopted to comply with

Executive Order 11246 have been sustained by the courts.

Contractors Ass'n. of Eastern Pa. v. Shultz, 442 F.2d 159

14

(3d Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971); Associated

General Contractors of Massachusetts, Inc, v. Altschuler, 490

F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974);

Southern Illinois Builders Association v. Ogilvie, 327 F.

Supp. 1154 (S.D. 111. 1971), aff'd 471 F.2d 680 (7th Cir.

1972); Joyce v. McCrane, 320 F. Supp. 1284 (D.C. N.J. 1970).

Moreover, the appropriateness of affirmative action

programs under the Executive Order was fully considered

and ratified by the Congress during the course of the

enactment of the 1972 amendments to Title VII. Congress,

at that time, emphasized the Third Circuit's opinion in

Contractors Ass'n of Eastern Pa. v. Shultz, supra, and the

differences between the affirmative action requirements of

the Executive Order and those of Title VII. Attempts to

limit the Executive Order program and to make Title VII the

exclusive federal remedy in employment discrimination mat

ters were rejected.

Further, Kaiser and the USW, as parties to a collective

bargaining agreement, could lawfully remedy the effects of

employment practices that had been identified as having an

adverse impact upon minorities and females. Emporium

Capwell v. Western Addition Community Organization, 420 U.S.

50 (1975); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976).

In sum, we argue herein that the defendants took appro

priate steps to identify and remedy a deficiency in the

15

utilization of minorities and females in the craft positions

of the Gramercy workforce. The adoption of the affirmative

action plan in issue here was an action reasonably calculated

voluntarily to bring the defendants' employment practices

pertaining to craft jobs into compliance with federal law

and regulations without the necessity of litigation and/or

federal intervention, and it did not result in unlawful

discrimination against the plaintiff or the class he

represents.

A. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLANS REQUIRED BY

EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246 AND ITS IMPLE

MENTING REGULATIONS DO NOT VIOLATE

TITLE VII OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF

1964.

The selection of persons to fill the training posi

tions at issue in this case was in accordance with an

affirmative action program which the defendants adopted

to comply with the obligations imposed upon government

_6/contractors under Executive Order 11246, as amended.

6/ Executive Order 11246 is the latest in a series of

presidential orders dating back to 1941, whose purpose has

been to prohibit employment discrimination where federal

government contracts are involved. Each Order has been

premised on the right and responsibility of the executive

branch to determine the terms and conditions upon which the

United States will contract with private parties. See e.g.

United States v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries, et al., 517

F.2d 826 (5th Cir., 1975), cert. denied, 425 U.S. 944

(1976); Contractors Association of Eastern Pa. v. Shultz,

supra.

16

While the district court did not specifically address

the question of the validity of the Executive Order

enforcement program, the clear implication of its hold

ing is that much of what government contractors, such

as Kaiser, are presently obligated to do under that

program is in violation of Title VII. That this is

erroneous is demonstrated by an examination of the

nature of the Executive Order, its enforcement mechanisms,

and the concept of affirmative action.

Among the obligations placed on government contrac

tors and subcontractors by the Executive Order is that

of taking necessary affirmative action with regard to the

hiring and promotion of minorities and females into fu

ture vacancies where they have previously been under

utilized (Executive Order, Section 202(1)).

The concept of what affirmative action contemplates

was, in our view, well stated by Kaiser's national

director of equal opportunity affairs in an exchange

with the district court (App. 170-171):

THE COURT: . . . Since you referred to the term

'affirmative action', why don't we get your

definition of it? I'm not holding you to any

legalistic precision, I'm merely trying to

get your general understanding, as you appre

ciate it.

THE WITNESS: I think the concept of affirmative

action, affirmative action is a plan for

an employer to develop, to do all of those

things that creates opportunities of employ

ment for all citizens. In the process of

that, to remove barriers that would make

that affirmative action a hollow gesture.

17

It's not a passive thing, there is a difference

between equal employment opportunity and affirm

ative action. Those are not synonymous. Open

ing the doors of employment to minorities or

females, where previously they had been barred

from employment, is but one step. To then

create an employment environment where they

can achieve and compete and perform is where

you get into the concept of affirmative action.

I think affirmative action calls for remedial

measures.

THE COURT: In other words, I take it that included

within the concept of affirmative action, as

you understand it to be, is color awareness, as

opposed to color blindness, with regard to those

with whom you've dealing?

THE WITNESS: Certainly. Yes, you would have to be

aware of that.

Under the Executive Order, this affirmative action

obligation is discharged by compliance with implementing

regulations issued by the Secretary of Labor (Ex. Order,

_ 7/ '

Section 202(4)). These implementing regulations require

contractors and subcontractors, inter alia, to analyze

their workforces and to identify areas in which they are

deficient in the utilization of minority group members and

7/ It is well established that Executive Order 11246 has the

force and effect of law. Local 189, United Papermakers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert. denied, 397

U.S. 919 (1970); Contractors Ass'n. of Eastern Pa. v. Shultz,

supra. See also Farkas v. Texas Instruments Co., 375 F.2d

629 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 977 (1967). It

is also well established that regulations issued pursuant to

appropriate authority themselves have the force and effect

of law unless they are in conflict with that authority. See,

e.g., Maryland Casualty Co. v. United States, 251 U.S. 342

(1920); United States v. Mississippi Power and Light Co.,

9 EPD [CCH] 1110,164 (S.D. Miss. 1975) (appeal pending);

United States v. New Orleans Public Service, Inc., 8 EPD [CCH]

119795 (E.D. La. 1974) (appeal pending).

18

the type of preferential treatment prohibited by Section

703 (j) of Title VII. While conceding that in the absence

of a finding of prior discrimination, employers could not

be compelled through a Title VII action because of Section

703 (j) to embrace the type of affirmative action required

to redress an underutilization of minorities or females

under the Executive Order, the Court of Appeals concluded

that "Section 703 (j) is a limitation only upon Title VII,

not upon any other remedies, state or federal." 442 F.2d

at 172. See also Association of General Contractors of

Massachusetts v. Altshuler, supra; E.E.O.C. v. American Tele

phone and Telegraph Co., supra; United States v.

Mississippi Power and Light, supra.

Therefore, it is not, as the district court thought,

significant that the minorities who have benefited by the

plan were not the victims of specific discriminatory acts

(App. 217). To support its contention on this point, the

district court relied on Watkins v. United Steelworkers of

America, Local 2369, 516 F.2d 41 (5th Cir. 1975) and Chance

v. Board of Examiners, 534 F.2d 993 (2d Cir. 1976). We

believe that both of these cases are inapplicable.

Both Watkins and Chance involved challenges to seniority

systems that provided for layoffs on a "last-in-first-out"

basis. In addition, Watkins involved a challenge to the

reverse side of that coin; a recall system based on a

21

females. Where deficiencies are determined to exist, the

contractor must seek to eliminate or modify any employment

practices causing or perpetuating the underutilization and,

furthermore, as part of its affirmative action program,

must develop goals and timetables to remedy the deficiencies

_8/

(41 CFR §60-2.10 et seq.).

1. Affirmative Action Plans adopted pursuant

to Executive Order 11246 have been

approved by the Courts___________________

The approval by the Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit of the "Philadelphia Plan" puts to rest the

8/ We believe that the district court, as well as some of

the parties, incorrectly characterized the selection ratio

called for by the Memorandum of Understanding as a "quota".

The instant Memorandum of Understanding does not require

Kaiser to select any unqualified persons because of their race

or sex or to meet any specific timetables for increasing the

numbers of minorities and females in craft jobs. We believe,

therefore, that the affirmative action plan in issue is more

accurately characterized as establishing "goals" and only

requiring good faith efforts to meet them. See 41 CFR

§60-2.14.

In another context, Congress has recognized this dis

tinction. In discussing the prohibition against hiring g-oa-irs <P<J<5T<ZS

contained in Section 518(b) of the Crime Control Act of 1976,

Senator Hruska distinguished goals from quotas as follows:

"the formulation of goals is not a quota . . . . a goal is a

numerical objective fixed realistically in terms of the

number of vacancies expected and the number of qualified

applicants available. Factors such as lower attrition rate

than expected, bona fide fiscal constraints, or lack of

qualified applicants would be acceptable reasons for not

meeting a goal that had been established and no sanctions

would accrue . . . ." 122 Cong. Rec. S. 17320 (daily ed.

Sept. 30, 1976) .

19

proposition that affirmative action plans necessarily con

flict with Section 703(a) and (d) of Title VII. Contrac

tors Ass'n. of Eastern Pa. v. Shultz, supra. In that

case, the court stated, 442 F.2d at 173:

To read §703 (a) in the manner suggested

by the plaintiffs we would have to attribute

to Congress the intention to freeze the status

quo and to foreclose remedial action under

other authority designed to overcome existing

evils. We discern no such intention either

from the language of the statute or from its

legislative history. Clearly the Philadelphia

Plan is color-conscious. Indeed the only

meaning which can be attributed to the "affir

mative action" language which since March of

1961 has been included in successive Executive

Orders is that Government contractors must

be color-conscious. Since 1941 the Executive

Order program has recognized that discrimina

tory practices exclude available minority man

power from the labor pool. In other contexts

color-consciousness has been deemed to be an

appropriate remedial posture. Porcelli v.

Titus, 302 F. Supp. 726 (D. N.J. 1969), aff'd,

431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir. 1970); Norwalk CORE

v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395 F.2d 920,

931 (2d Cir. 1968); Offermann v. Nitkowski,

378 F.2d 22, 24 (2d Cir. 1967) . . . We

reject the contention that Title VII prevents

the President acting through the Executive

Order program from attempting to remedy the

absence from the Philadelphia construction

labor [force] of minority tradesmen in key

trades. (footnote omitted)

See also United States v. International Union of Elevator Con

structors, Local Union No. 5, 538 F.2d 1012 (3d Cir. 1976);

Southern Illinois Builders Association v. Ogilvie, supra;

E.E,O.C. v. American Telephone and Telegraph Co., 419 F.

Supp. 1022 (E.D. Pa. 1976) (appeal pending).

The court in Contractors Ass'n, also rejected the

further argument that affirmative action goals constitute

20

"last-out-first-in" concept. To follow such systems would, it

was alleged, perpetuate the effects of prior discriminatory acts

and would therefore be unlawful. In essence, those cases

involved the issue of who would be retained or be restored to

_£/

a job. That issue is simply not before the Court in this

case. No employee's present job or continued employment is

or will be in jeopardy as a result of the disputed provisions

of the defendants' collective bargaining agreement. What has

been challenged here is a remedial program applicable only

to future vacancies in training positions.

Although there was a claim in Watkins that the recall

procedures there also involved the filling of future vacancies,

the Court in that case did not address the argument in terms

which recognized such vacancies as being true vacancies to

which no employee had a claim by reason of prior service i’n

10/

the positions involved. In fact, the recall system in

Watkins did not involve real vacancies in that sense, since

the issue involved recall to jobs previously held. On the

9/ Other court of appeals cases focusing on the question of

seniority preference to minorities and females have also been

largely confined to layoff/recall situations. See Jersey

Central Power and Light Co. v. I.B.E.W., 508 F.2d 6(T7 (3d Cir.

1975), vacated, 425 U.S. 987 (1976), 542 F.2d 8 (3d Cir. 1976)

(on remand from S. Ct.) and Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works,

502 F.2d 1309 (7th Cir. 1974) cert, denied, 97 S. Ct. 2214

(1976).

10/ In Watkins the Court concluded, we believe correctly,

that "there is no substantial difference between the layoff

of employees pursuant to employment seniority and the recall

of those employees on the same basis". 516 F.2d at 52.

22

other hand, in the present case, true vacancies are involved.

No Gramercy employee has any prior claim to a future training

11/

vacancy. Neither the plaintiff nor any member of his

class alleges that what is involved is his right to be re

tained on or restored to "his job".

In this regard, unlike Watkins, the present case does

not involve "an employer's use of a long-established

seniority system" nor does it present a challenge to the

"express intent [of Congress] to preserve contractual rights

of seniority as between whites and persons who had not [speci

fically] suffered any effects of discrimination" Watkins v.

United Steelworkers of America, Local 2369, supra, 516

F.2d at 44, 48 (emphasis added). The plaintiff, and the

class he represents, had no prior contractual rights to the

new on-the-job training program devised by the defendants.

Their present contractual rights spring from the 1974 col

lective bargaining agreement which they challenge, and it

is that agreement which provides all employees with a new,

and, indeed, their first opportunity to obtain craft posi

tions .

11/ Judicially imposed goals, when directed toward future

vacancies or job opportunities, have not limited the

minority beneficiaries to "identifiable victims of specific

acts of discrimination". See Local 53 Asbestos Workers v.

Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969); NAACP v. Allen, 493

F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974); Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail

Deliverers' Union, 514 F.2d 767 (2d Cir. 1975); Carter v.

Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 406

U.S. 950 (1972).

23

Unlike the situations in Watkins, Chance, Jersey Central

Power and Light Co. v. I.B.E.W., 508 F.2d 687 (3d Cir. 1975),

vacated, 425 U.S. 987 (1976), 542 F.2d 8 (3d Cir. 1976) (on

remand from S. Ct.), and Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 502

F.2d 1309 (7th Cir. 1974), the selection system challenged

herein, which benefits minority and female employees, is not

one which is sought to be imposed under Title VII upon an

existing seniority system. It is not a system requiring "a

preferential treatment on the basis of race which Congress

specifically prohibited in Section 703 (j)" as an available

remedy under Title VII in the absence of proof of prior

12/

discrimination. Watkins, supra, 516 F.2d at 46. Instead,

it is a system collectively bargained for in compliance with

13/ ‘

Executive Order 11246.

In Chance, the court differentiated between remedial

programs giving preference to minorities in hiring to fill

new vacancies and layoff rights of competing employees

under a collective bargaining agreement. The court there

held that a labor agreement that provided for layoffs

12/ Kirkland v. New York, 520 F.2d 420 (2d Cir. 1975), cert.

denied, 97 S. Ct. 73 (1976), upon which the court below also

relied, is distinguishable from the present case for this same

reason.

13/ In this regard, the court in Jersey Central specifically

found that a conciliation agreement between the company, unions

and the EEOC had not modified the "last-in-first-out" provi

sions of the existing collective bargaining agreement and thus

that court did not, as did not the courts in Watkins, Chance

or Waters, address the issue of the consequence had such a

modification been agreed to.

24

based upon a "last-in-first-out" concept was not unlawful

because Congress had indicated a policy of protecting

such seniority systems as bona fide. 534 F.2d at 997-98.

The court, however, clearly distinguished the protection

accorded such systems from the permissibility of lawful

programs, such as the instant one, that concern future

vacancies and are remedial in nature. 534 F.2d at 998-99.

2. Affirmative Action Plans, including

Goals and Timetables, implemented to

comply with Executive Order 11246

have been approved by Congress._____

The effect of the district court's holding in this

case is to declare that the affirmative action plan adopted

by the defendants is not only precluded by Title VII as a

Title VII remedy, but that it is also precluded by Title VII

from being voluntarily adopted as a remedial Executive Order

measure.. As such, the holding is in clear conflict with

expressed Congressional intent.

From the beginning, the Congress has recognized and

accepted the Executive Order program. As originally enacted,

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made express

reference to the Executive Order in a context which clearly

contemplated continuance of the Executive Order program.

25

would have made Title VII the exclusive Federal remedy for

certain individuals in the field of employment discrimina

tion. 118 Cong. Rec. 3367-3370; 3371-3373; 3959-3965. In

opposing that amendment, Senator Williams, one of the floor

managers of the 1972 bill, made the following statement (118

Cong. Rec. 3372):

Furthermore, Mr. President, this amend

ment can be read to bar enforcement of

the Government contract compliance pro

gram at least, in part. I cannot

believe that the Senate would do that

after all the votes we have taken in

the past 2 to 3 years to continue that

program in full force and effect.

Most importantly, Congress, just two days after hear

ing the comments of Senator Saxbe, quoted above, rejected

an amendment offered by Senator Ervin which would have

proscribed the adoption of goals by government contractors.

118 Coug. Rec. 1676. In speaking against this amendment,

Senator Javits had the Third Circuit's prior approval of

affirmative action goals in Contractors Ass'n. reprinted

in the Congressional Record (118 Cong. Rec. 1665). More

over, he argued that what the Ervin amendment sought to

reach was:

[T]he whole concept of "affirmative action"

as it has been developed under Executive

Order 11246 and as a remedial concept under

Title VII.

28

Section 709(d), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-8(d). Contractors Ass'n.

of Eastern Pa. v. Shultz, supra, 442 F.2d at 171. Indeed,

in the debates concerning adoption of Title VII, Congress

expressly rejected an amendment by Senator Tower which would

have made Title VII the exclusive Federal remedy in the

area of equal employment opportunity. 110 Cong. Rec.

13650-52 (1964); Local 12, Rubber Workers v. N.L.R.B., 368

F.2d 12 (5th Cir. 1966); Sanders v. Dobbs House, Inc., 431

F.2d 1097 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948 (1970);

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, 415 U.S. 36 (1974).

Congress again had an opportunity to review the Executive

Order program in connection with consideration of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (Public L. 92-261), which

amended Title VII. At the time of the debates, the Secretary

of Labor's regulations requiring affirmative action in the

form of goals and timetables had been in effect for several

years. [See, 41 CFR §60-1.40, which, prior to its amendment

in January 1977 (42 Fed. Reg. 3454 (1977)) was last amended

in 1969, and 41 CFR §60-2 (Order No. 4), which was originally

issued in 1970 (35 Fed.Reg. 2586, February 5, 1970)]. Congress

was also well aware of what was meant by "underutilization"

14/

14/ Section 709 (d) provided that the EEOC was to accept

report forms required of employers under the Executive Order

and not require separate or duplicate reports.

26

triggering the establishment of goals. As originally

introduced, the 1972 legislation sought, inter alia, to

transfer the entire Executive Order enforcement program to

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In speaking

in support of his amendment to strike that transfer pro

vision, so as to leave the administration of the Executive

Order with the Department of Labor, then Senator Saxbe

stated:

The OFCC's affirmative action programs

have tremendous impact and require that

260,000 Government contractors in all

industries adopt positive programs to

seek out minorities and women for new

employment opportunities. To accomplish

this objective, the OFCC has utilized

the proven business technique of establish

ing "goals and timetables" to insure the

success of the Executive order program.

It has been the "goals and timetables"

approach which is unique to the OFCC's

efforts in equal employment, coupled

with extensive reporting and monitoring

procedures that has given the promise

of equal employment opportunity a new

credibility.

The Executive order program should not

be confused with the judicial remedies for

proven discrimination which unfold on a

limited and expensive case-by-case basis.

Rather, affirmative action means that all

Government contractors must develop pro

grams to insure that all share equally in

the jobs generated by the Federal Govern

ment's spending. Proof of overt discrim

ination is not required. 118 Cong. Rec.

1385.

Senator Saxbe's proposed amendment was adopted. 118

Cong. Rec. 1387-1398 (1972). In addition to preserving

the Executive Order program in its present form, Congress

at this time also rejected a new amendment which again

27

Philadelphia-type plans are based on

the Federal Government's power to require

its own contractors or contractors on pro

jects to which it contributes— for example,

State projects with a Federal contribution—

to take affirmative action to enlarge the

labor pool to the maximum extent by pro

moting full utilization of minority-group

employees, and by making certain require

ments for those who hire to seek out

minority employees . . . 118 Cong. Rec.

1664 (1972).

Senator Javits, in further stating his objections to the

Ervin amendment, distinguished affirmative action plans

under the Executive Order from those under Title VII:

First, it would undercut the whole

concept of affirmative action as developed

under Executive Order 11246 and thus pre

clude Philadelphia-type plans.

Second, the amendment, in addition

to the dismantling the Executive order

program, would deprive the courts of

the opportunity to order affirmative

action under title VII of the type which

they have sustained in order to correct

a history of unjust and illegal discrim

ination in employment and thereby fur

ther dismantle the effort to correct

these injustices. 118 Cong. Rec. 1665

(1972).

Furthermore, with the decision in Contractors Ass'n., and

its holding that Sections 703(a), 703 (h) and 703 (j) of Title

VII were not applicable to Executive Order remedial programs

clearly before the Congress, the Senate Subcommittee on Labor,

in its section by section analysis of the 1972 Amendments to

Title VII, provided:

In any area where the new law does not

address itself, or in any areas where a

specific contrary intention is not indicated,

it was assumed that the present case law as

29

developed by the courts would continue to

govern the applicability and construction of

Title VII.

Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee on Labor

and Public Welfare, Legislative History of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, at 1844 (1972).

In sum, "[t]here is unusually clear evidence" that

Congress has recognized the existence of the Executive

Order contract compliance program, including its re

quirements as to goals and timetables, and rejected

attempts to curtail or eliminate it. United States v.

International Union of Elevator Constructors, Local

Union No. 5, supra, at 1019-20. In fact, Congress

adopted at least two provisions designed to make the

15/

program work fairly and more effectively. The con

tract compliance program is therefore one in which

Executive action has the implied and express authoriza

tion of Congress.

15/ The two provisions adopted by the Congress were the

Javits amendment (Section 715, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-14) which

created the Equal Employment Opportunity Coordinating

Council and a provision (Section 718, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-17)

requiring a hearing and adjudication prior to terminating

a contract of a government contractor with an approved

affirmative action plan.

30

3. Defendants' voluntary efforts at meeting

the requirements of Executive Order 11246

were in accordance with contemplated pro

cedures__________________________________

The enforcement scheme of the Executive Order relies

primarily upon voluntary compliance with its implementing

regulations. While sanctions, including loss of contracts,

debarment from future contracts and litigation to enforce

contractual obligations, are provided for, the essence of

the program is self-evaluation and voluntary correction

without the direct intervention of the government agencies

16/

charged with enforcement.

Such voluntary compliance is a necessity for the Govern

ment. In 1974, there were approximately 168,000 government

contractors that employed between 30 and 40 million persons.

In the same year, the eighteen federal agencies delegated

Executive Order enforcement responsibility by the Secretary

of Labor were authorized only 1,738 compliance officers to

17/

conduct the reviews necessary to determine compliance.

16/ Contractors, like Kaiser, comply because of the very

real threat of government enforcement proceedings. In this

respect, the compliance mechanism of the Executive Order is

not unlike that contemplated by the Internal Revenue Code.

Not every taxpayer is audited annually. However, there is

substantial compliance with the tax laws because of, inter

alia, the threat of an audit that would reveal deficiencies

and thereby subject a taxpayer to enforcement proceedings.

17/ The Federal Civil Rights Enforcement Effort - 1974,

Volume 5, To Eliminate Employment Discrimination, United

States Commission on Civil Rights, July 1975, at 390.

31

Given the Government's limited resources, it is obvious

that frequent supervision of individual government contractors

is not feasible, but that the effectiveness of the Executive

Order program must rest largely upon good faith efforts by

government contractors to comply with its terms.

Even when intervention is necessary, however, the Execu

tive Order emphasizes informal resolution. Where a contrac

tor is found not to be in compliance with its equal employ

ment obligations, Section 209(b) of the Executive Order

provides:

Under rules and regulations prescribed

by the Secretary of Labor, each contracting

agency shall make reasonable efforts within

a reasonable time limitation to secure com

pliance with the contract provisions of this

Order by methods of conference, conciliation,

mediation and persuasion before proceedings

shall be instituted [upon referral to the

Department of Justice] under Subsection (a)(2)

of this Section, or before a contract shall

be cancelled or terminated in whole or in

part under Subsection (a)(5) . . .

In turn, the Secretary of Labor's implementing regula

tions (41 CFR §60-1.24(c)(2)) require that "whenever possible,"

apparent violations be resolved by informal means.

If any complaint investigation or com

pliance review indicates a violation of the

equal opportunity clause, the matter should

be resolved by informal means whenever pos

sible. Such informal means may include the

holding of a compliance conference by the

agency . . .

In addition, where non-compliance stems in whole or in

part from the adoption or continuation of an employment prac

tice encompassed within a collective bargaining agreement,

32

Section 207 of the Executive Order requires that attempts be

made to involve the appropriate union in the conciliation

effort and to otherwise obtain that union's cooperation "in

the implementation of the purpose of this Order".

The district court's view that an affirmative action

plan, such as was adopted by the defendants, can only be

implemented upon a finding or admission of discrimination,

if affirmed, would undermine the basic reliance which the

Executive Order program places on voluntary, self-initiated

compliance. The need for such conditions as would be imposed

by the court below was specifically addressed and rejected in

Contractors' Ass'n. of Eastern Pa. v. Shultz, supra. The

court in that case held that the Executive Order plan re

quired there did not impose "a punishment for past mis

conduct, [but instead] exacts a covenant for present

performance." 442 F.2d at 176. The court further

explained:

The Philadelphia Plan is valid Executive action

designed to remedy the perceived evil that

minority tradesmen have not been included in the

labor pool available for the performance of con

struction projects in which the federal govern

ment has a cost and performance interest.

★ ★ ★

[D]ata in the September 23, 1969 order

revealing the percentages of utilization

of minority group tradesmen in the six

trades compared with the availability of

such tradesmen in the five-county area,

justified issuance of the order without

regard to a finding as to the cause of

the situation. . . . A finding as to

33

the historical reason for the exclusion

of available tradesmen from the labor

pool is not essential for federal

contractual remedial action. (Emphasis

added) (442 F.2d at 177).

As a very practical matter, employers cannot be expected

voluntarily to adopt remedial measures in compliance with the

Executive Order if they would also be required to admit to

engaging in prior discrimination. It is simply not realistic

to expect an employer to make such an admission and thereby

subject himself to potential litigation by aggrieved parties.

The avoidance of such litigation and potential back pay lia

bility has been recognized by the courts as an important and

legitimate reason for taking affirmative remedial action. In

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417-418 (1975)

the Supreme Court declared:

If employers faced only the prospect of an

injunctive order, they would have little

incentive to shun practices of dubious

legality. It is the reasonably certain

prospect of a backpay award that 'provide[s]

the spur or catalyst which causes employers

and unions to self-examine and to self-

evaluate their employment practices and to

endeavor to eliminate, so far as possible,

the last vestiges of an unfortunate and

ignominious page in this country's history

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479

F.2d 354, 379 (CA 8 1973).

B. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN CONCLUDING

THAT AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLANS EMBODIED

IN CONSENT AGREEMENTS AND WHICH DO NOT

CONTAIN ADMISSIONS OF DISCRIMINATION

AND/OR ARE NOT JUDICIALLY SANCTIONED

VIOLATE TITLE VII

Title VII, like Executive Order 11246, places primary

emphasis upon good faith efforts to obtain voluntary

34

compliance. Section 706 (b) of Title VII specifically calls

upon the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to seek to

"eliminate . . . alleged unlawful employment practice[s] by

informal methods of conference, conciliation, and persua

sion." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(b). In this regard, the Supreme

Court has recognized that "Congress chose to encourage

voluntary compliance with Title VII by encouraging concilia

tory procedures before federal coercive powers could be

invoked." Emporium Capwell v. Western Addition Community

Organization, supra, 420 U.S. at 72. The EEOC meets its

statutory obligations in this regard by the execution of

conciliation agreements, a common feature of many of which

is the adoption by employers of affirmative action obliga

tions, including goals and timetables for the hiring, pro

motion and transfer of minorities and females into future

vacancies. See, CCH, Employment Practices Guide 1M! 1470-

1488; Jersey Central Power and Light Co. v. I.B.E.W.,

18/

supra, 508 F.2d at 695, fn. 18.

Similarly, this Court has sanctioned the voluntary

resolution of Title VII complaints through its approval of

consent decrees, including consent decrees with affirmative

18/ In the rare instance when the issue has been presented,

courts have given full effect to EEOC conciliation agreements.

See, Jersey Central Power and Light Co. v. I.B.E.W., supra;

E.E.0.C. v. Mississippi Baptist Hospital, 11 EPD [CCH]

1110,822 (S.D. Miss. 1976) (requiring specific performance

of a conciliation agreement).

35

action provisions setting forth specific hiring, promotion

and transfer goals. E.g. United States v. City of Jackson,

519 F.2d 1147 (5th Cir. 1975); United States v. Allegheny

Ludlum Industries, et al., supra, (where in addition to

Title VII, violations of Executive Order 11246 were also

alleged and resolved by the consent decree). Further, both

conciliation agreements and consent decrees traditionally

contain disclaimers of wrongdoing.

The district court, however, determined that two

elements are necessary to have a valid affirmative action

plan like the one in question: (1) a finding or admission

of prior discrimination and (2) court supervision. If sus

tained, that holding would render the statutory scheme of

Title VII a nullity and would, as a practical matter, end

the voluntary resolution through affirmative action of

employment discrimination matters under both that Act and

the Executive Order. As we have previously indicated, to

require admission of a violation of the law would expose

a defendant to enormous liability and thus remove a major

incentive for settlement. Moreover, since conciliation

agreements are by their nature not supervised by the courts,

there could never be, in the opinion of the trial court, a

lawful conciliation agreement that contained affirmative

action goals. These results, we respectfully suggest, are

contrary to this Court's recognition "that Congress and the

Supreme Court have expressed a preference for voluntary

36

compliance above all other tools of enforcement[.] United

States v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries, et al. , supra, 517

F.2d at 849. See also, Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

supra; Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, supra.

The holding of the court below is also inconsistent

with the earlier quoted declaration of the Supreme Court

that Title VII places an affirmative obligation on employers

and unions "to self-examine and to self-evaluate their employ

ment practices and to endeavor to eliminate, so far as pos

sible, the last vestiges of an unfortunate and ignominious

page in this country's history." Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 418 quoting from United States v.

N.L. Industries, supra, 479 F.2d at 379.

In this regard, the affirmative action plan adopted by the

defendants was a reasonable attempt to meet any possible

obligations under Title VII without potentially lengthy,

19/

expensive and vexatious litigation. In light of the

19/ At the time the defendants negotiated the 1974 Labor

Agreement, the state of the law was such that they could have

reasonably concluded that an employment practice which re

sulted in only two blacks being admitted to a craft training

program and in an overall percentage of minorities (2%) in

craft jobs which was substantially lower than either the

minority population in the plant (14.8%) or the relevant com

munity (40%) was prima facie a violation of Title VII. Jones

v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 431 F.2d 245 (10th Cir. 1970),

cert, denied, 401 U.S. 954 (1971). Moreover, the then existing

employment practice would have continued disproportionately to

exclude blacks and females because of their inability to ob

tain the necessary craft experience in the building trades

(footnote continued on next page)

37

historical underutilization of minorities in the Gramercy

plant, as recognized by the defendants through the voluntary

adoption by Kaiser in 1969 of affirmative hiring goals, the

defendants could reasonably have expected that in the event

of a Title VII suit, a court would find that the effects of

the prior exclusion of blacks would be perpetuated in any

new on-the-job training program by the adoption of a selec

tion practice based solely on plant seniority. See United

States v. Allegheny Ludlum, supra, 517 F.2d at 880 (discus

sion of female participation in 50/50 goals for trade and

craft jobs which, because of their present extreme under

utilization in the P&M workforce, will result in their

future selection in substantial numbers despite their

minimum seniority compared to that of males); Griggs v..

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

(footnote continued from previous page)

outside the plant. The continued application of an experience

requirement could only be lawful under Title VII if there was

a legitimate business necessity. E.E.0.C. v. N.Y, Times Broad

casting Services, Inc,, 542 F.2d 356 (6th Cir. 1976).

Given these conditions, it was not unreasonable for

the defendants to have self-evaluated their employment

practices, Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975),

to have concluded that their practices were arguably viola

tive of Title VII, and, to have taken steps that would pro

vide relief routinely ordered by courts in Title VII liti

gation. See brief of Union Appellants pp. 21-24.

38

C. ANY ALTERATION OF PLAINTIFFS' SENIORITY

EXPECTATIONS WHICH HAS OCCURRED HERE

BECAUSE OF COMPLIANCE WITH EXECUTIVE

ORDER 11246 IS LAWFUL

The district court correctly recognized that seniority

rights are the product of collective bargaining agreements

and as such are subject to change through the collective

bargaining process (App. 211). The court, however, concluded

that the parties, by agreeing to a 50/50 affirmative action

provision with regard to future craft training vacancies,

had established a discriminatory practice that violated Sec

tion 703 of Title VII.

The Supreme Court has consistently held that seniority

rights are not property rights but rather are expectancies

that may be modified to conform employment practices with

federal law and regulations that prohibit discrimination

in employment. In Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

supra, 96 S. Ct. at 1271, the Court stated:

This Court has long held that employee

expectations arising from a seniority

system agreement may be modified by

statutes furthering a strong public

policy interest. . . . The Court has

also held that a collective bargaining

agreement may go further, enhancing the

seniority status of certain employees for

purposes of furthering public policy

interests beyond what is required by

statute, even though this will to some

extent be detrimental to the expectations

acquired by other employees under the

previous seniority agreement. Ford Motor

Company v. Huffman, 345 U.S. 330 (1953).

And the ability of the union and employer

39

voluntarily to modify the seniority system

to the end of ameliorating the effects of

past racial discrimination, a national

policy objective of the "highest priority,"

is certainly no less than in other areas of

public policy interests." (citations and

footnote omitted)

In the instant case, the parties did precisely what

they were obligated to do by federal law and regulation.

They identified a practice which had an adverse impact on

the training opportunities available to minorities and

females and bargained for an alternative means to correct

and eliminate the effects of that practice.

The plaintiffs have not, however, challenged that

portion of the Labor agreement that made craft opportuni

ties available to them. Rather, they express disappoint

ment that the collective bargaining agreement did not

2 0 /

give them more.

The union has an obligation as the exclusive collective

bargaining agent to "fairly and in good faith represent the

interests of minorities. . . . " Emporium Capwell Co. v.

Western Addition Community Organization, supra, 420 U.S. at

20/ This disappointment is not well founded. Kaiser was

under no obligation to the plaintiffs to create a new

training program, at substantial expense, so as to provide

them a means of obtaining craft jobs. Likewise, having

created such a program, there is nothing in Title VII or any

other act which mandates the use of seniority as a selection

criterion. Indeed, for them to establish a training program

based solely on seniority might have violated Title VII. See

Gates v. Georgia Pacific Corp., 492 F.2d 292 (9th Cir. 1974).

40

64. When the union meets that obligation it also fulfills

its obligations to all members of the bargaining unit be

cause, as the Supreme Court has recognized, particularly in

the area of seniority, "[t]he complete satisfaction of all

who are represented is hardly to be expected." Ford Motor

Co. v. Huffman, supra, 345 U.S. at 338. See also Vaca v.

Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 (1967); Emporium Capwell v. Western

Addition Community Organization, supra.

The defendants herein were simply responsive to the

demands of the Executive Order and to remedial programs

ordered by the courts or obtained by the responsible govern-

21/

ment agencies in consent decrees. E.g. United States v.

Allegheny Ludlum Industries, et al., supra; Patterson v.

Newspaper and Mail Deliverers' Union, 514 F.2d 767 (2d Cir.

1975). We believe that the defendants' actions are in full

compliance with and are not contrary to the Executive Order

nor to Title VII.

21/ The defendants were well aware of the development of the

case law and the requirements of Executive Order 11246. The

USW and its locals, for instance, have been defendants in liti

gation involving issues similar to those sought to be corrected

by the affirmative relief provided by the Supplemental Agree

ment. E.g. United States v. United States Steel Corp.,

371 F. Supp. 1045 (N.D. Ala. 1973) reversed on other grounds,

520 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 97 S. Ct. 61

(1976); United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652

(2nd Cir. 1971). Moreover, the USW was a party to the nation

wide steel industry consent decrees approved by the Court in

United States v. Allegheny Ludlum Industries, et al., supra,

and the agreements in issue here contain many of the elements

of affirmative relief contained in those consent decrees.

41

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, and on the basis of the

authorities cited, the United States respectfully submits

that the district court's decision is contrary to law and

should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J. STANLEY POTTINGER

Assistant Attorney General

JOSEPH T. EDDINS

Associate General Counsel

ABNER SI3AL

General Counsel

Beatrice Rosenberg

Marian Halley

Attorneys GERALD J. GALLINGHOUSE

Equal Employment United States Attorney

Opportunity Commission

ALFRED G. ALBERT

Acting Solicitor of

Labor

JAMES D. HENRY

LOUIS G. FERRAND, JR.

GARY M. BUFF

Attorneys

Department of Labor

ROBERT T. MOORE ^

RICHARD S. UGELOW

Attorneys

Department of Justice

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Richard S. Ugelow, hereby certify that a copy of

the foregoing Brief of the United States and the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission as amicus curiae was

on this 12th day of February, 1977, mailed, first class,

postage prepaid, to the following counsel of record:

Michael Gottesman, Esquire

Bredhoff, Cushman, Gottesman & Cohen

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Michael R. Fontham, Esquire

Stone, Pigman, Walther,

Wittmann & Hutchinson

1000 Whitney Bank Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Robert J. Allen, Jr., Esquire

Legal Department

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corporation

300 Lakeside Drive

Oakland, CA 94612

Frank W. Middleton, Jr.

Taylor, Porter, Brooks & Phillips

P.O. Box 2471

Baton Rouge, LA 70821

OGELOJf.CHARD S

Attorney

U.S. Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

f