Norris v. Virginia State Council of Higher Education Reply Brief of Plaintiffs

Public Court Documents

February 8, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Norris v. Virginia State Council of Higher Education Reply Brief of Plaintiffs, 1971. 03af04b4-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2a02b54d-52c3-4c00-baac-519dc84ba886/norris-v-virginia-state-council-of-higher-education-reply-brief-of-plaintiffs. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

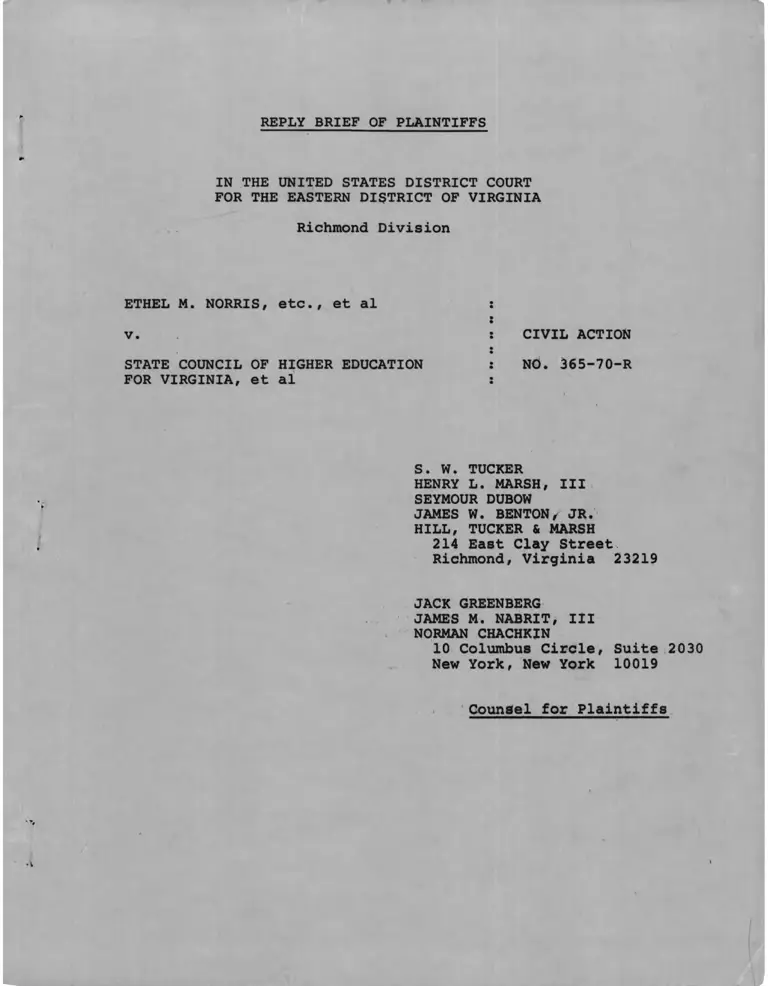

REPLY BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Richmond Division

ETHEL M. NORRIS, etc., et al

v. CIVIL ACTION

STATE COUNCIL OF HIGHER EDUCATION

FOR VIRGINIA, et al

NO. 365-70-R

S. W. TUCKER

HENRY L. MARSH, III

SEYMOUR DUBOW

JAMES W. BENTON, JR.

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I The Evidence Clearly Establishes A Bi-racial

System Of Higher Education ------------------- 1

II The Defendants Had Fair Notice Of Plaintiff's

Claims --------------------------------------- 4

III Community Pressures Favoring Segregation

Have Not Been Overcome---- ------------------- 5

IV The History Of Richard Bland College, As

Reviewed In Its Brief, Does Not Negate

Racial Considerations------------------------ "7

V Two Colleges Cannot Live As Cheaply As One ---- 9

VI This Court Can Enjoin The Proposed Escalation

Without Invalidating Any Statute ------------- 11

A. The Appropriations Act Does Not Mandate

Escalation------------------------------- H

B, The Equitable Remedy May Not Be Circumscribed By The Statures Establishing

Richard Bland As A Part Of William and

Mary------------------------------------- 11

VII The State Council May And Should Be Directed

To Devise A Plan Whereby Colleges Will Be

Desegregated ------------------- 15

l

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Page

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) -------------- 16

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ------- 7

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas,

349 U.S. 294 (1955) ----------------- ---------- 14,16

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (I960) ----- 17

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 ------------ ----- --------------------- 7

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier

County, 429 F. 2d 364 (1970).------------------- 14,15,16

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) — 14

Perkins v. Matthews, ____U.S.____ (No. 46,

October Term 1970) ---------------------------- 17

Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 246 (1941) -- 12

Smith v. North Carolina State Board of Education

(4th Cir., Misc. No. 674, August 3, 1970) ----- 15,16

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) ----------- 2,3

Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F.Supp. 724 (S.D. Ga.

1965) ----------------------------------------- 15,16

Tyrone, Inc. v. Wilkerson, 410 F.2d 639 (4thCir. 1969) ------------------------------------ 12

United States v. The State of Georgia, et al

(N.D. Ga., C. A. #12972) ----------------- ------- 16

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) ---------- 3

Witcher v. Peyton, 382 F.2d 707 (1967) ---------- 3

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, §23-9.6 ----- 10

Fair Jury Selection Procedure, 75 YALE L. J.

322 (1965) ------------------------------------ 3

ii

Page

Finkelstein, The Application of Statistical

Decision Theory to the Jury Discrimination

Case, 80 HARV. L. REV„ 338 (1966) ------------- 3

Swain v. Alabama: A Constitutional Blueprint

for the Perpetuation of the All-white Jury,

52 VA. L. REVo 1157 ' (1966 ------ ------ 3

Use of Peremptory Challenges to Exclude Negroes

from Trial Jury, 79 HARV. L. REV. 135 (1965) -- 3

lii

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Richmond Division

ETHEL M. NORRIS, etc., et al

CIVIL ACTION

STATE COUNCIL OF HIGHER EDUCATION

FOR VIRGINIA, et al

NO, 36 5-7 0-R

REPLY BRIEF

I

The Evidence Clearly Establishes

A Bi-Racial System Q£ Higher Education

In. support of its argument that plaintiffs have

failed to adduce any proof of a state-wide dual system of

higher education, the brief of the State Council and the

Governor asserts that Virginia State College has made a

vigorous effort to secure white students and faculty members,

that Richard Bland has since its inception in 1961 followed

a "non-discrimination" admissions policy and that the

record is devoid of evidence of any disparity of facilities

among the various institutions of higher education.

This argument ignores the plain fact that Virginia

has historically operated a racially dual system of higher

education (PX #4, p. 1). Virginia State College and Norfolk

State College which were created and maintained for the

education of Negroes still enroll over 80% of the black

students attending the four-year institutions in Virginia.

Although black students comprise 12,2% of the total enroll

ment of the 15 four-year institutions, over 92% of the

black students are enrolled in three institutions (Norfolk

State, Virginia State and Virginia Commonwealth University)

and the remaining 8% are attending the remaining 12 insti

tutions. Ten of these 12 institutions have racial minorities

of less than 1.5 per cent (App. I). See pages 2 through 6

and 16 through 19 of plaintiffs' opening brief.

The defendants allege that over one-half of the

34 institutions deviate less than 6% in black enrollment

from a norm of 10.9% of the total enrollment, and cite

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) in support of the

proposition that a 10-15% deviation from the norm is not

in itself proof of racial discrimination.

In the first place, this argument is based on

an erroneous mathematical computation. For example, an

enrollment with 4% black contains a 60% plus deviation

from a norm of 10.9% black rather than a 6% deviation.

Similarly an enrollment with 1% black contains a 90% plus

deviation from a norm of 10.9% black rather than a 9%

deviation, A correct analysis of che extent of the

deviations shown by this record reveals a racially dual

system which is substantially similar to that in existence

prior

/to the Brown decision.

Moreover, Swain itself was based on a similar

mathematical error and has not been followed in subsequent

decisions. In Swain, where Negroes had constituted 10%

2

to 15% of the panels drawn from the jury box in a county

with 26% Negroes in the total population, the Court stated

in justification for its holding the following conclusion:

"We cannot say that purposeful discrimina

tion based on race is satisractorily

proved by showing that an identifiable

group is underrepresented by as much as

10%." (380 UoS. at 208-209) .

What the Court characterized as an underrepresentation by

10% (that being read as a numerical difference between

the 26% of the population and the 10% to 15%, plus, of the

jury pool) was in all reality a diminution of representation

of Negroes by 30% of the number which proportionate

representation would require. See Whitus v. Georgia,

385 U.S. 545 (1967) which was favorably cited in Witcher v.

Peyton, 382 F„ 2d 70-7 (1967) . In Witcher, this circuit listed

the following as commentary critical of Swain: Finkelstein,

The Application of Statistical Decision Theory to the Jury

Discrimination Cases, 80 HARV, L, REV, 338 (1966); Comments,

Swain v. Alabama: A Constitutional B1ueptint for the

Perpetuation of the All-white Jury, 52 VA, L. REV. 1157

(1966); Note, Fair Jury Selection Procedure, 75 YALE L„

J. 322 (1965); Note, Use of Peremptory Challenges to

Exclude Negroes from Trial Jury, 79 HARV, L. REV. 135

(1965). (382 F. 2d, at page 710).

In the instant case, defendants’ submission

to HEW (PX #4) and PX #7 conclusively demonstrate the

continued maintenance of a dual system, and the report

to HEW fails to provide any effective procedures for the

3

disestablishment of the dual character of the system.

II

The Defendants Had Fair

Notice Of Plaintiffs' Claims

Paragraph 3 of the complaint (and particularly

when read in the light of paragraph 10 and the complaint

as a whole) points to the racial ddentiflability of Virginia

State College as an institution for Negroes. The reader

cannot avoid being told that the defendants (as agents of

the state) presently maintain certain institutions of

higher learning wherein all or virtually all of the

students are of one race and certain instutions of higher

learning wherein all or vitually all of the students are

of the other race. Paragraph 3 plainly alleges that the

defendants (presently) have the duty to desegregate the

student body of every such institution,, The statement,

in the present tense, that such duty exists is a state

ment of non-performance. When this particular duty will

have been performed, it will no longer exist.

Paragraphs 3, 10 and 16 and the prayer that the

defendants be required to effectuate the racial desegre

gation of the several colleges and universities ^paragraph

20(c)) leave no doubt as to the plaintiffs' claims.

4

Ill

Community Pressures Favoring

Segregation Have Not Been Overcome

Although the William and Mary Board of Visitors

asserted that this record does not show that community

pressures prevented black students from attending Richard

Bland, its brief was strangely silent on the question of

pressures on white students.

The Virginia State officials testified that,

since 1965, Virginia State College has made an active and

vigorous effort to recruit white students (Tr. 1, p. 69).

Its chief recruitment officer has attended class-night

programs throughout the surrounding area, cooperated and

coordinated with the guidance counselors at the area high

schools, utilized the white faculty members from various

departments to go out into the high schools to recruit

white students (id., p. 68), and exposed the white students

who visit the campus to the white faculty members and

students on the campus (id., p, 68i. He further testified

that if Virginia State is going to attract white students,

they are going to come from an area wi'-hin commuting

distance of the college (id., p. 71). Notwithstanding the

extensive recruiting efforts in this area, most of the

white students attend Richard Bland rather than Virginia

State College (id., p. 71). During the 1970-71 session,

more than 92% (821 out of 891) of the white undergraduate

students commuting to Virginia State or Bland attended Bland,

5

The white parents and students selecting a

college usually ask first of all the percentage of white

at Virginia State and if they [the white students] can

attend Virginia State tid, , p, 62) <,

"This has been one question that is

usually asked. What is the percentage

of whites there? I think they asked us

that first above everything else. It

gives the impression if you had more

white students others would not mind

coming, " (Id.. , p„ 62 ) .

According to Dr. Russell, there would be social

pressures on the white parents who contemplated sending their

children to Virginia State and those whose children were in

attendance at State if Richard Bland is escalated to four-

year status (Id., p. 102). The evidence clearly indicated

that the escalation, of Bland to four-year degree granting

status "would definitely hinder the recruitment of white

students" at Virginia State (Id., p. 77),

Notwithstanding the appreciably lower annual

tuition cost at Bland ($400 as against $6905, only fourteen

black commuting first and second year students elected to

join the virtually all-white student body at Bland where

the administration and faculty are all white, The over

whelming majority of the black students from Southside

Virginia who attend college at Petersburg pay the higher

price to attend the traditionally Negro college. The

"open admissions" policy of the colleges and the

recruiting efforts by Richard Bland and by William and

Mary have proved as ineffective in overcoming community

mores and habits of racial segregation as was "Freedom

6

of Choice" in the public free schools.

The necessity of a showing of pressure or

coercion exerted against students or parents of either

race was obviated by the Supreme Court as early as 1954:

"In the field of public education, the

doctrine of separate but equal has no

place." Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483.

and again in 1968:

"In the context of the state-imposed

segregated pattern of long standing, the

fact that in 1965 the Board opened the

doors of the former 'white' school to

Negro children and of the 'Negro' school

to white children merely begins, not ends,

our inquiry whether the Board has taken

steps adequate to abolish its dual,

segregated system." Green v. School Board

of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 437.

IV

The History Of Richard Bland

College, As Reviewed In Its

Brief, Does Not Negate Racial Considerations

The Higher Education Study Commission, in its

1965 Report to the General Assembly, did not envision the

escalation of Richard Bland as William and Mary and Bland

suggest in their brief at pages 17 and 18. This Commission

recommended that four two-year branches of senior

institutions should be incorporated into the state system

of community colleges, namely:

Danville Division of Virginia Polytechnic

Institute

Eastern Shore Branch of the School of General

Studies of the University of Virginia

7

Patrick Henry College of the University of

Virginia

Richard Bland College of the College of

William and Mary (PX #10, p. 40)

The State Council of Higher Education concurred

in this recommendation. None of these four institutions

has yet achieved four-year status. Only Richard Bland

has sought to override the determination of these bodies.

The other institutions which have recently become

four-year colleges (Clinch Valley, George Mason and

Christopher Newport) were escalated in accordance with the

plans of the State Council (Id. , pp. 2"1, 28 and 41) .

The notion that a four-year course at Bland

would cost a thousand dollars less than at Virginia State

is illusory. There is no evidence of what the tuition

charge would be at Richard Bland if it is escalated.

Certainly„ the increased, size of the institution, the cost

of additional equipment necessitated by escalation and the

increased size and complexity of the faculty (including

many with specialized training required for third and fourth

year courses) would cause an increase in the operating costs

and the tuition charges of a four-year Richard Bland.

There is no reason to presume that the State Council, with

its thorough analysis of all available information and

its educational expertise, did not consider these factors,

especially in view of its expressed concern that competent

students not be deprived of higher educational opportunities

because of high student costs.

Moreover, there is no reason to assume that the

8

Council overlooked the availability of Interstate Highways

85 and 95 when it assessed the commuting third and fourth

year students' time and distance factors between their

respective homes and Virginia State College, as did Dean

McNeer (Tr, III, pp. 128-9) when he acquiesced in the

suggestion of counsel that any student living south of

Richard Eland College would have to drive twenty minutes

longer to get to Virginia State College than he would to

get to Richard Bland, (Tr. Ill, p, 116),

The fact is inescapable that only with respect

to Richard Bland are there persistent attempts to circum

vent the studies and recommendations of the expert

commissions. The administrative and legislative mechanisms

calculated to spur the expansion of Bland are without

parallel. They are and have been unique measures to meet

the unique situation of a traditionally black college

situated where it can serve Southside Virginia,

V

Two Colleges Cannot

Live As Cheaply As One

The William and Mary Board argues that there is

no evidence that "Richard Bland College would be favored

by the General Assembly of Virginia to the detriment of

Virginia State College," This argument overlooks the

action of the General Assembly m disregarding the

decision of a vast array of educational expertise when it

made funds available for the escalation of Richard Bland.

9

All of the agencies which had thoroughly

studied the problem of meeting the higher educational

needs in the Petersburg area had concluded that Virginia

State College was the institution best suited to serve

as the four-year degree-granting institution in that area,

and had recommended that Bland be made a part of the

Community College system of Virginia,

The Higher Education Study Commission's Report

in 1965, the State Council of Higher Education in its 10

year master plan for higher education released in 1967, the

State Council's 1966-68 and 1968-70 Biennial Reports to

the General Assembly, and the testimony of the State Council

officials during the 1970 session of the General Assembly

all had opposed the escalation of Bland. These Councils,

their staffs and their advisory committees had concluded

that it was educationally unsound to overlap similar levels

of programs and degrees in the same area and that Virginia

State College was the institution best able to expand

to accommodate the anticipated enrollment growth for the

area. .

In rejecting these findings and recommendations

of the educational experts, including those who are

charged by law not to act as the representative of any

particular region or institution (Code §23-9,3), the

General Assembly ordained that whatever resources would

henceforth be available for third and fourth year college

education in the Petersburg area would be divided between

Bland and Virginia State, if not indeed concentrated at

Bland.

- 10 -

VI

This Court Can Enjoin The Proposed Escalation

Without Invalidating Any Statute

A

The Appropriations Act Does Not Mandate Escalation

From the testimony of Dr. Paschall (Tr. Ill, pp. 97-

100) and from the Resolution passed on February 16, 1970 by the

Board of Visitors of the College of William and Mary (Paschall

X #2), we learn that just as had been done with respect to

Christopher Newport College, the Board of Visitors proposed to

the General Assembly, then in session, through the House

Appropriations Committee, "the escalation of Richard Bland

College to the status of a four-year undergraduate degree

granting institution, the third-year level program leading to

the degree to be instituted in 1971-72 and a fourth-year program

to be offered in 1972-73, . . . all being subject to the availa

bility of adequate resources". (Paschall X #2). The Resolution,

as submitted to the General Assembly, required -

"That upon the completion of the preparation

of the concentration programs," for which there

would be available qualified faculty, adequate

physical facilities and library holdings, and

justifiable registration, "these programs be

submitted to the Board of Visitors for approval,

and subsequently transmitted to the State

Council of Higher Education for its approval".

The Board of Visitors did not suppose that the General Assembly

would repeal so much of Code Section 23-9.6 as requires the

approval of the State Council or, literally, empowers the Council

with the approval of the Governor "to limit any institutions to

such curriculum offerings as conform to the plans adopted by the

Council".

11

The General Assembly did not alter Code Section 23-9.6.

It did not command the Board of Visitors to escalate Richard

Bland with or without the approval of the Council. It merely

provided the financial means by which escalation could be accom

plished if, after assessing the entire problem and being

satisfied that means were at hand to deal with it, the Board of

Visitors would seek and obtain the permission of the Council to

escalate,. Such was the understanding of Dr. Paschal! and the

Board of Visitors. Presumptively, such was the legislative

intent„

In the light of these facts, this case in its

jurisdictional aspect is on "all fours" with Phillips v. United

States, 312 U.S. 246 (1941), where (at page 252) the Court

stated:

"Some constitutional or statutory provision is

the ultimate source of all actions by state

officials. But an attack on lawless exercise

of authority in a particular case is not an

attack upon the constitutionality of a statute

conferring the authority even though a misreading

of the statute is invoked as justification."

The Court in that case went on to hold that a three-judge court

is not properly convened merely Decause a state official seeks to

invoke a statute as a defense against a charge of questioned

conduct. "In other words-" the Court said, "the complaint must

seek to forestall the demands of some general state policy, the

validity of which he challenges," Supra, at 253 [emphasis added]

See also Tyrone, Inc, v . Wilkerson, 410 F. 2d 639, 4th Cir, 1969)

12

In Phillips, the Governor of Oklahoma invoked his

constitutional and statutory authority to declare martial law

and call out the national guard to forestall "any forcible

obstruction of the execution of the laws or reasonable appre

hension thereof" and, under color thereof, sought to enforce

claims against the Grand River Dam Authority to the work of

which the United States had allotted twenty million dollars.

These state statutory provisions were held insufficient to in

sulate him from the jurisdiction of the single federal judge to

enjoin the Governor's lawless conduct.

Here, the appropriations act merely provides the

financial means by which Bland may be escalated, provided other

requirements of state and federal law will be met. It likewise

is insufficient to insulate the Board of Visitors from the power

of veto which state law vests in the State Council of Higher

Education with the approval of the Governor or from the require

ments of the Fourteenth Amendment that the proposal to escalate

will not be made and that the exercise of the power of veto will

not be declined if, as here, escalation will defeat the Constitu

tional rights of the plaintiffs.

B

The Equitable Remedy May Not Be Circumscribed

By The Statutes Establishing Richard Bland As

A Part Cf William and Mary

Plaintiffs urge the Court to provide for the merger

of Richard Bland College into Virginia State College or the

community college system. Such a transfer to retard the perpet

uation of a dual system of higher education in the Petersburg

13

area would be a matter of remedy, not substance, and does not

require the convening of a three judge court.

The Court, exercising its traditional equity power,

may effect such relief without questioning the constitutional

validity of the state statute which establishes Richard Bland

as a part of William and Mary College. In Brown II, 349 U.S.

294 (1955), the Court stated:

"In fashioning and effectuating the decrees,

the courts will be guided by equitable prin

ciples. Traditionally, equity has been

characterized by a practical flexibility in

shaping its remedies and by a facility for

adjusting and reconciling public and private

needs. These cases call for the exercise of

these traditional attributes of equity power."

Id. at 300.

The Court in the later case of Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S, 145, 154 (1965) expressly stated that "the

court has not merely the power but the duty to render a decree

which will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory

effects of the past as well as bar like discrimination in the

future".

In rejecting the notion that state law can limit the

fashioning of relief, the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit,

in Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County, 429 F.

2d 364, 368 (1970), stated that:

"Appellees' assertion that the District Court . . .

is bound to adhere to Arkansas law, unless the state

law violates some provision of the Constitution, is

not constitutionally sound where the operation of

the state law in question fails to provide the

constitutional guarantee of a non-racial unitary

school system. The remedial power of the federal

courts under the Fourteenth Amendment is not limited

by state law."

14

It is appropriate to note that in Haney, supra, at

369, the court found no error in the district court's decree

annexing one school district to another. See also Turner v.

Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724, 730 (S.D. Ga. 1965) where the district

court exercised its equity power to place the school system of

Taliaferro County, Georgia in receivership in order to redress

constitutional rights of Negro children.

This Court certainly has the power to fashion relief

that will eliminate the perpetuation of the dual system of higher

education in the Petersburg area in particular and in the

Commonwealth of Virginia as a whole.

VII

The State Council May And Should Be DirectedTo Devise A Plan Whereby Colleges Will Be Desegregated

The defendants contend that a state agency may not be

ordered to prepare a general desegregation plan if it is not

authorized by state law to execute such plan. (Brief of State

Council and Governor, pp. 24-25). They point to the July 31,

1970 order and memorandum of decision in Smith v. North Carolina

State Board of Education (4th Cir., Misc. No. 674) filed on

August 3, 1970 by the Honorable J. Braxton Craven, Jr., United

States Circuit Judge, wherein a single judge of the Fourth

Circuit stayed an order of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of North Carolina which had directed the

North Carolina State Board of Education to instruct local school

boards with respect to the preparation of plans for converting

15

to unitary non-racial school systems. They suggest that the

Smith case reflects the law of the Circuit.

In Haney v. County Board of Sevier County, supra, the

Eighth Circuit held that an argument similar to the one the

defendants advance here "is not constitutionally sound where the

operation of the State law in question fails to provide the

constitutional guarantee of a non-racial unitary school system"„

(429 F. 2d at 368o)

The statutory three-judge district court in Turner v.

Goolsby, 255 F„ Supp 724 (S.D. Ga. 1965) placed the school

system of Taliaferro County, Georgia in receivership, appointed

the State School Superintendent as Receiver and through that

officer achieved racial desegregation.

In an unreported order filed December 17, 1969 in

United States v. The State of Georgia, et al, (N.D. Ga., C.A. #

12972) , three of the judges of the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Georgia enjoined the State Board of

Education from the payment of public funds to those local school

districts which failed to measure up to certain standards

established for the desegregation process.

The theory advanced by the defendants here would mean

that if the state legislature did not look ahead and provide

effective procedures under state law for the effectuation of

federal rights, the federal courts would be powerless to pro

vide remedies„ This is contrary to both the spirit and letter

of Brown II, supra, Louisiana, supra, and Haney, supra. See

also Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

16

364 U.S. 339 (1960), and Perkins v. Matthews U.S

(No. 46 October Term 1970). The Constitution of the United

States is_ the Supreme Law of the land.

S. W„ TUCKER

HENRY L. MARSH, III

SEYMOUR DUBOW

JAMES W. BENTON, JR.

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs

C E R T I F I C A T E

I certify that copies of the foregoing reply brief

were mailed to R. D. Mcllwaine, III, Esquire, P. O. Box 705,

Petersburg, Virginia 23803, counsel for Board of Visitors of William and Mary in Virginia, et al; Edward S. Hirschler,

Esquire, and Everette G„ Allen, Jr., Esquire, 2nd Floor,

Massey Building, Fourth and Main Streets, Richmond, Virginia 23219, counsel for The Visitors of Virginia State College;

William G. Broaddus, Esquire, Assistant Attorney General,

Supreme Court Building, Richmond, Virginia 23219 , counsel for

State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, et al; and to

the Honorable John D. Butzner, Jr., Richmond, Virginia, the

Honorable Walter E. Hoffman, Norfolk, Virginia, and the

Honorable Robert R. Merhige, Jr., Richmond, Virginia, members of Three-Judge Court, this 8th day of February, 1971.

Respectfully submitted

7

17