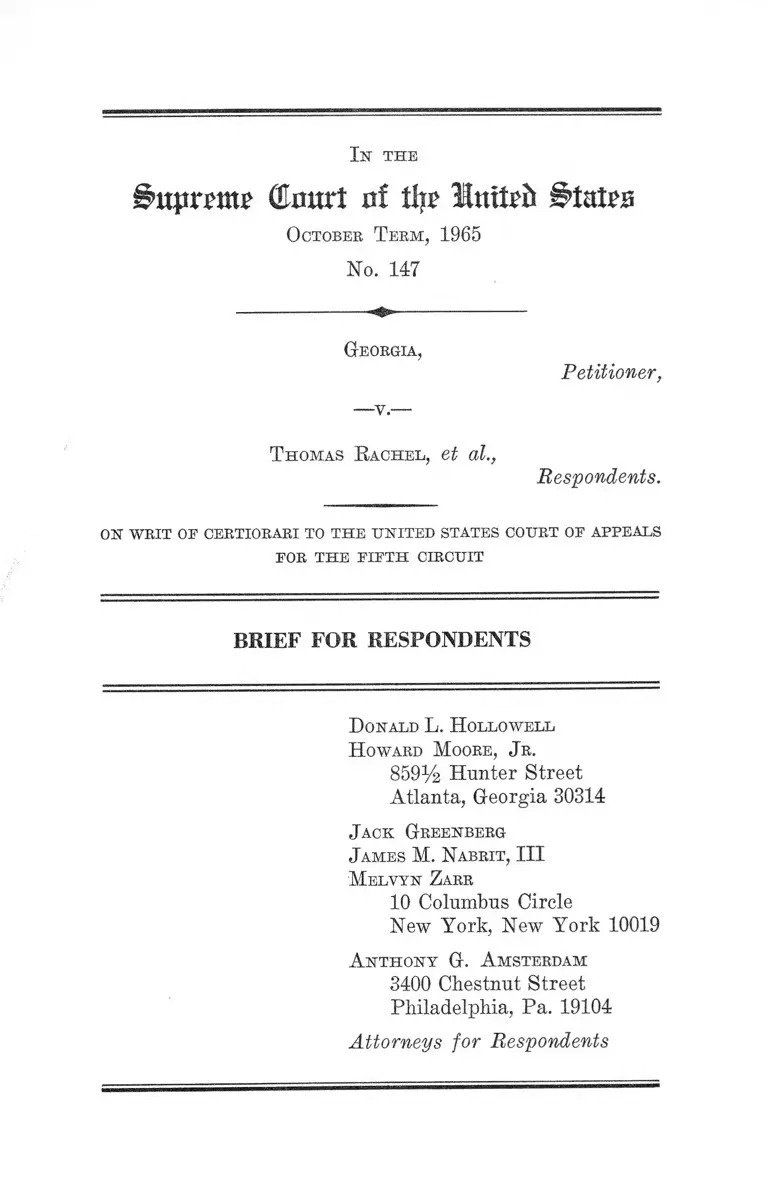

Georgia v. Rachel Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Georgia v. Rachel Brief for Respondents, 1965. aa42d022-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2a0f29d6-18c4-4736-bc2a-5ca0412d0652/georgia-v-rachel-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(Eimrt of % InttTft

October T er m , 1965

No. 147

G eorgia,

—y.—

Petitioner ,

T homas R ach el , et al.,

Respondents.

on w r it of certiorari to t h e u n ited states court of appeals

for t h e f if t h circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

D onald L. H ollow ell

H oward M oore, J r .

859% Hunter Street

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

J ack Green berg

J am es M. Na brit , I I I

M elvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n th on y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys fo r Respondents

I N D E X

Opinions Below .................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 1

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes and Rules In

volved ................................................................................... 2

Questions Presented............................................................ 9

Statement of the C ase ........................................................ 10

Summary of Argument..................................................... 13

Argument ................................................................................... 17

I. The Court of Appeals Did Not Lack Jurisdic

tion of the Appeal by Reason of Asserted Un

timeliness in Filing the Notice of Appeal....... 17

A. As Rule 37(a)(2) Has No Application to

Pre-Verdict Appeals, the Notice of Appeal

Was Timely F ile d ........................................... 18

B. The Court of Appeals Had Jurisdiction to

Review the Remand Order by Proceedings

in the Nature of Mandamus, as to Which

No Time Is Limited by R u le........................ 27

1. The Remand Order Is Reviewable by

Mandamus................................................... 27

2. The Court of Appeals Might Permissi

bly Entertain the Present Proceeding

as on Petition for Mandamus................ 32

PAGE

11

C. This Court May Review the Remand Or

der as on Original Petition for Mandamus 34

II. Defendants Criminally Prosecuted for Con

duct Protected by Title I I of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 May Remove Their Prosecutions

Under 28 U. S. C. § 1443 Without Showing

That the State Criminal Statutes Underlying

Their Prosecutions Are Facially Unconstitu

PAGE

tional or the State Courts Unfair ...„................ 35

A. The Background of 28 U. S. C. § 1443 ........ 36

1. Legislative Background.......................... 36

2. Judicial Background................................ 73

B. The Construction of 28 U. S. C. § 1443 .... 87

1. The Court of Appeals Correctly Held

That Persons Prosecuted for Exercis

ing Their Right to Equal Public Ac

commodations Under the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 Are Thereby Denied and

Unable to Enforce Those Rights,

Within the Meaning of § 1443(1), Not

withstanding the Statutes Underlying

the Prosecutions Are Not Unconstitu

tional on Their Face and the State

Courts Are Not Alleged to Be Unfair 90

2. Persons Prosecuted for Exercising

Their Right to Equal Public Accom

modations Under the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 Are Thereby Prosecuted for

Ill

an Act Under Color of Authority De

rived from the Civil Rights Act, With

in the Meaning of § 1443(2) .................. 104

III . Defendants’ Removal Petition Was Not Defi

cient as a Pleading ............................................. 114

IV. The Court of Appeals’ Directions Governing

Hearing on Remand Were P rop er.................. 118

Conclusion.............................................................................. 119

Appendix

Motion for Stay Pending Appeal................................. la

Order and Judgment on R em itter............................ 4a

T able of Cases

Alabama v. Boynton, S. D. Ala., C. A. No. 3560-65,

April 16,1965 .................................................................... 26, 87

Anderson v. Elliott, 101 Fed. 609 (4th Cir. 1900),

dism’d, 22 S. Ct. 930 (1902)........................................... 41

Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E. D. Ark.

1963) 86

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U. S. 773 (1964) .......... 75

The Astorian, 57 F. 2d 85 (9th Cir. 1932) .................... 33

Babbitt v. Clark, 103 U. S. 606 (1880)............................ 30

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964)........................ 98,112

Bankers Life & Cas. Co. v. Holland, 346 U. S. 379

(1953).................................................................................. 31

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963) .. 98

PAGE

IV

Birsch v. Tumbleson, 31 F. 2d 811 (4th Cir. 1929) ..... 41

Blyew v. United States, 80 U. S. (13 Wall.) 581 (1871) 65

Bowles v. Strickland, 151 F. 2d 419 (5th Cir. 1945) .... 25

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F . 2d 401 (5th Cir. 1961) ........ 71

Brown v. Cain, 56 F . Supp. 56 (E. D. Pa. 1944) ........ 41, 42

Brunei- v. United States, 343 U. S. 112 (1952) ............ 24

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 (1883) ........................ 80, 82

California v. Chue Fan, 42 Fed. 865 (C. C. N. D. Cal.

1890) .................................................................................. 86

California v. Lamson, 12 F . Supp. 813 (N. D. Cal.

1935), petition for leave to appeal denied, 80 F. 2d

388 (Wilbur, Circuit Judge, 1935) .............................. 86

Carter v. Campbell, 285 F. 2d 68 (5th Cir. 1960) ....... 33

Castle v. Lewis, 254 Fed. 917 (8th Cir. 1918) .............. 41

City of Birmingham v. Croskey, 217 F. Supp. 947

(N. D. Ala. 1963) .............................................................. 86

City of Chester v. Anderson, 347 F. 2d 823 (3d Cir.

1965) ..................................................................................... 89

City of Clarksdale v. Gertge, 237 F. Supp. 213 (N. D.

Miss. 1964) ........................................................................ 85

Cobbledick v. United States, 309 U. S. 323 (1940) ..... 24

Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U. S. (6 Wheat.) 264 (1821) .. 39

Colorado v. Symes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932) ...................... 117

Cooper v. Alabama, 5th Cir., No. 22424, December 6,

1965 ......................................................................................... 87

Coppedge v. United States, 369 U. S. 438 (1962) ....... 32

Cox v. Louisiana, 348 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1965) ........ 86

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278

(1961) ....................................................................................... 97

Crump v. Hill, 104 F. 2d 36 (5th Cir. 1939) ................ 32

Cutting v. Bullerdick, 178 F. 2d 774 (9th Cir. 1949) .. 34

PAGE

V

Des Isles v. Evans, 225 F. 2d 235 (5th Cir. 1955) ..... 33

DiBella v. United States, 369 U. S. 121 (1962) .......... 24

Dickey v. United States, 332 F. 2d 773 (9th Cir. 1964) 33

Dilworth v. Riner, 343 F. 2d 226 (5th Cir. 1965) .... 96

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) ............98,112

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) .... 97

Employers Reinsurance Corp. v. Bryant, 299 U. S.

374 (1937) .................... ................................................... 30

England v. Louisiana State Board of Medical E x

aminers, 375 U. S. 411 (1964) .....................................92, 111

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 (1958) ................ 75

Ex parte Collett, 337 U. S. 55 (1949) ................ 25

Ex parte Fahey, 332 U. S. 258 (1947) ............... 30

Ex parte McCardle, 73 U. S. (6 Wall.) 318 (1868) .. 54

Ex parte Newman, 81 U. S. (14 Wall.) 152 (1871) .. 30

Ex parte Peru, 318 U. S. 578 (1943) ............................ 2, 34

Ex parte Tilden, 218 Fed. 920 (D. Ida. 1914) . 41

Ex parte United States, 287 U. S. 241 (1932) ... 35

Ex parte United States ex rel. Anderson, 67 F. Supp.

374 (S. D. Fla. 1946) ................................................... 42

Ex parte Warner, 21 F. 2d 542 (N. D. Okla. 1927) .... 41

Ex parte Wells, 29 Fed. Cas. 633 (No. 17368) (1878) 86

Farmer v. State, 161 So. 2d 159 (1964) .................... 97

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963) ................................ 54,91

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951) ................ 112

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963) ............ 97

Foman v. Davis, 371 U. S. 178 (1962) ........................ 33

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51 (1965) ................ 112

PAGE

VI

Galloway v. City of Columbus, 5th Cir., No. 22935,

November 24, 1965 ....................................................... 87

Gay v. Ruff, 292 U. S. 25 (1934) .................................. 30

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 TJ. S. 565 (1896) ....79, 80, 81,102

Georgia v. Tuttle, 377 U. S. 987 (1964) ................12, 28, 32

Georgia Hardwood Lumber Co. v. Compania de

Navegacion Transmar, S.A., 323 TJ. S. 334 (1945) 32

Hadjipateras v. Pacifica, S.A., 290 F. 2d 697 (5th Cir.

1961) .................................................................................. 33

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 (1964) ..12,13, 36,

88,103,116,118

Heflin v. United States, 358 U. S. 415 (1959) ............ 23, 34

Henry v. City of Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964)........ 97

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 (1954) ............ 75

Hill v. Pennsylvania, 183 F. Supp. 126 (W. D. Pa.

1960) ............................ -..................................................... 86

Hoadley v. San Francisco, 94 U. S. 4 (1876) ............ 25,30

Hughley v. City of Opelika, M. D. Ala., Cr. No. 2319E,

November 19, 1965 .......................................................... 87

Hull v. Jackson County Circuit Court, 138 F . 2d 820

(6th Cir. 1943) .................................................................. 85

Hulson v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co., 289

F. 2d 726 (7th Cir. 1961) ............................................. 33

In re Fair, 100 Fed. 149 (C. C. D. Neb. 1900) ............ 41

In re Hohorst, 150 U. S. 653 (1893) ............................ 32

In re Kaminetsky, 234 F. Supp. 991 (E. D. N. T.

1964) 85

In re Leigh, 139 F. 2d 386 (D. C. Cir. 1943) .............. 33

In re Matthews, 122 Fed. 248 (E. D. Ky. 1902) ........ 42

In re Miller, 42 Fed. 307 (E. D. S. C. 1890) ............ 42

PAGE

V ll

In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1 (1890) ................................ .41, 43, 54

In re Pennsylvania Co., 137 U. S. 451 (1890) ............ 30

In re Wright, M. D. Ala., Cr. No. 11739N, August

3, 1965 ............................................................................... 87

Insurance Co. v. Comstock, 85 U. S. (16 Wall.) 258

(1872) ................................................................................ 30

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) ........60, 61, 82, 84,

85, 86, 89, 90,

92, 93, 95, 96, 98,

99,100,101,102

Knight v. State, 161 So. 2d 521 (1964) ........................ 97

La Buy v. Howes Leather Co., 352 U. S. 249 (1957) 29

Lefton v. City of Hattiesburg, 333 F. 2d 280 (5th Cir.

1964) ................................:.................... ............................. 71

Lima v. Lawler, 63 F. Supp. 446 (E. D. Ya. 1945) .... 41, 42

Local No. 438 v. Curry, 371 U. S. 542 (1963) ............ 28

Lott v. United States, 367 U. S. 421 (1961) ............ 23, 25

Louisiana v. Murphy, 173 F. Supp. 782 (W. D. La.

1959) ................................................................................... 86

Maryland v. Kurek, 233 F. Supp. 431 (D. Md. 1964) 85

Maryland v. Soper (No. 1), 270 U. S. 9 (1926) ....89,116,117

McClellan v. Carland, 217 U. S. 268 (1910) ................ 29

McMeans v. Mayor’s Court of Fort Deposit, M. D.

Ala., Cr. No. 11759N, September 30, 1965 .... 87

McNair v. City of Drew, 351 F. 2d 498 (5th Cir.

1965) .................................................................................. 86

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 (1963) 67,112

Mercantile National Bank v. Langdeau, 371 U. S. 555

(1963)

PAGE

28

V l l l

PAGE

Metropolitan Cas. Ins. Co. v. Stevens, 312 U. S. 563

(1941) ................................................................................. 77

Meyers v. United States, 116 F. 2d 601 (5th Cir.

1940) ........... 23

Missouri Pacific Ey. Co. v. Fitzgerald, 160 U. S. 556

(1896) ................................................................................. 30

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961) ............................ 67,112

Murray v. Louisiana, 163 U. S. 101 (1896) ................ 79, 80

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ................ 97

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1881) .... .......77, 80, 81,82,

92,101,102

New Jersey v. Weinberger, 38 F . 2d 298 (D. N. J .

1930) ................................................................................... 86

New York v. Galamison, 342 F. 2d 255 (2d Cir.

1965) ...........................................33, 89,105,108,109,110, 111

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 (1935) .................... 75

North Carolina v. Alston, 227 F. Supp. 887 (M. D.

N. C. 1964) ........................................................................ 85

North Carolina v. Jackson, 135 F. Supp. 682 (M. D.

N. C. 1955) ........................................................................ 86

Nye v. United States, 313 U. S. 33 (1941) .................... 18,23

O’Neal v. United States, 272 F. 2d 412 (5th Cir. 1959) 33

Orr v. United States, 174 F. 2d 577 (2d Cir. 1949) 25

Parr v. United States, 351 U. S. 513 (1956) ................ 24

Peacock v. City of Greenwood, 347 F. 2d 679 (5th Cir.

1965) ................................................. 86,104,105,108,109, 111

People v. McLeod, 25 Wend. 482 (Sup. Ct. N. Y.

1841) ................................................................................... 42

Platt v. Minnesota Mining & Mfg. Co., 376 U. S. 240

(1964) ................................................................................ 29,31

Pritchard v. Smith, 289 F . 2d 153 (8th Cir. 1961) .... 71

IX

Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F. 2d 336 (5th Cir. 1965), re

hearing denied, 343 F. 2d 909 (5th Cir. 1965) ....... 1

Railroad Co. v. Wiswall, 90 U. S. (23 Wall.) 507

(1874) ................................................................... ............. 28, 30

Rand v. Arkansas, 191 F. Snpp. 20 (W. D. Ark. 1961) 86

Reconstruction Finance Corp. v. Prudence Securities

Advisory Group, 311 U. S. 579 (1941) ...................... 34

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85 (1955) ............................ 75

Reed v. Madden, 87 F . 2d 846 (8th Cir. 1937) ............ 41

Robinson v. Florida, 345 F. 2d 133 (5th Cir. 1965) .... 86

Roche v. Evaporated Milk Assn., 319 U. S. 21 (1943) 31

Roth v. Bird, 239 F. 2d 257 (5th Cir. 1956) ................ 33

Schlagenhauf v. Holder, 379 U. S. 104 (1964) .... ....... 31

Schoen v. Mountain Producers Corp., 170 F. 2d 707

(3d Cir. 1948) .................................................................. 25

Scott v. Sandford, 60 U. S. (19 How.) 393 (1857) .... 56

Semel v. United States, 158 F. 2d 229 (5th Cir. 1946) 26

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 (1959) .................... 97

Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 592 (1896) ................ 79,80

Snypp v. Ohio, 70 F . 2d 535 (6th Cir. 1934) ................ 86

Societe Internationale Pour Participations Indus-

trielles et Commerciales, S.A., v. McGrath, 180 F.

2d 406 (D. C. Cir. 1950) ............................................. 33

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880) ....73, 78, 93,

94,100,103

Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257 (1880) .................... 41

Texas v. Dorris, 165 F. Supp. 738 (S. D. Tex. 1958) .... 86

Thomas v. Mississippi, 380 U. S. 524 (1965) ................ 97

Thomas v. State, 160 So. 2d 657 (1964) .................... 97

PAGE

X

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963) ....................92, 111

Turner v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 106 U. S. 552

(1882) ................................................................................. 30

United States v. Healy, 376 U. S. 75 (1964) ............ 23

United States v. Lipsett, 156 Fed. 65 (W. D. Mich.

1907) ................................................................................... 41

United States v. Rice, 327 U. S. 742 (1946) ................ 30

United States v. Roth, 208 F. 2d 467 (2d Cir. 1953) 26

United States v. Smith, 331 U. S. 469 (1947) ............ 29

United States v. Stromberg, 227 F. 2d 903 (5th Cir.

1955) ................................................................................... 33

United States v. Williams, 227 F . 2d 149 (4th Cir.

1955)..................................................................................... 26

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) 29

United States ex rel. Coy v. United States, 316 U. S.

342 (1942) .............................. 23

United States ex rel. Drury v. Lewis, 200 U. S. 1

(1906).................................................................................. 41

United States ex rel. Flynn v. Fuelhart, 106 Fed. 911

(C. C. W. D. Pa. 1901) ................................................... 41

United States Alkali Export Assn. v. United States,

325 U. S. 196 (1945) ......................................... 31

Van Dusen v. Barrack, 376 U. S. 612 (1964) ............ 31

Van Newkirk v. District Attorney, 213 F. Supp. 61

(E. D. N. Y. 1963) ................................................... 86

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1880) ....60, 61, 74, 76, 77,

78, 81, 82, 89, 90,

92, 93, 95, 96, 98,

99,100,101,102,103

PAGE

X I

PAGE

Walker v. Georgia, 381 U. S. 355 (1965) .................... 103

Weehsler v. County of Gadsden, 351 F. 2d 311 (5th

Cir. 1965) .......................................................................... 86

West Virginia v. Laing, 133 Fed. 887 (4th Cir. 1904) 41

Williams v. Mississippi, 170 IT. S. 213 (1898) ............ 80

Con stitutional and S tatutoky P rovisions

IT. S. Const., Art. VI, el. 2 ..................... -........................... 2

IT. S. Const., Amend. X I I I ........................................... - 62,70

IT. S. Const., Amend. X IV ...................... ..........2, 66, 67, 70, 77

IT. S. Const., Amend. X V .............................................66, 70, 77

18 U. S. C. §242 (1964) ..................................................... 57

18 U. S. C. §1404 (1964) ................................................. 22, 24

18 IT. S. C. §3731 (1964) ................................................. 22, 26

18 IT. S. C. §3771 (1964) ................................................... 19

18 IT. S. C. §3772 (1964) ................................................... 18

28IT.S. C. §1257 (1964) ..................................................... 91

28 U. S. C. §1291 (1964) ................................................... 26,29

28 IT. S. C. §1331 (1964) ................................ 69

28 U. S. C. §1343(3) (1964) ......................................... 68

28 U. S. C. §1441 (1964) ........................................... 37,69

28 IT. S. C. §1442(a) (1) (1964) .............................. 41,107

28 IT. S. C. §1443 (1964) ............2, 9,16, 24, 25, 28, 29, 35, 36,

55, 70, 87, 89, 99,117,118

28 U. S. C. §1443(1) (1964) ....... 11,13,14,15, 35, 60, 72, 73,

76, 78, 88, 89, 90,103,104,105,

107,108,110, 111, 114

28 U. S. C. §1443(2) (1964) ....11,13,15,57,60,73,88,89,

90,104,105,107,108,110,

111, 113,114

XU

28 U. S. C. §1444 (1964) ................................................. 37

28 U. S. C. §1446(a) (1964) .....................................2, 3, 89,117

28 U. S. C. §1446(c) (1964) ............................................. 74

28 U. S. C. §1446(e) (1964) ............................................. 17

28 U. S. C. §1447(d) (1964) .................................2, 3,12, 24, 28

28 U. S. C. §1651 (1964) ................................................. 2, 29, 34

28 IT. S. C. §2106 (1964)..................................................... 25,116

28 IT. S. C. §2107 (1964).................. 23

28 IT. S. C. §2241(c) (2) (1964) ........................... 41

28 U. S. C. §2251 (1964) ............................ 53

42 I '. S. C. §1981 (1964) ...................... 65

42 U. S. C. §1983 (1964) ................................................. 65, 68

42 U. S. C. §1988 (1964) ............ 71

42 U. S. C. §2000a (1964) ..... 2

42 IT. S. C. §2000a-2 (1964) ............................................. 2, 6

Eev. Stat. §641 (1875) .......................... ..64,69,70,73,74,77,

78, 85,106

Eev. Stat. §643 (1875) ...................................................... 106

Eev. Stat. §722 (1875) ...................................................... 71

Eev. Stat. §1977 (1875) ..................................................... 65

Eev. Stat. §1979 (1875) ...................... ............................... 65, 68

28 U. S. C. §74 (1940) ..................................................... 64, 70

28 U. S. C. §76 (1940) ..................................................... 117

28 IT. S. C. §230 (1940) ..................................................... 23

28 U. S. C. §1447(d) (1958) ................................ 25,27,30,73

Act of September 24, 1789, eh. 20, 1 Stat. 73 ............ 38

Act of September 24,1789, ch. 20, §11, 1 Stat. 7 8 ...... 38

Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20, §12, 1 Stat. 7 9 ....... 39

Act of September 24,1789, ch. 20, §14, 1 Stat. 8 1 ....... 39

Act of February 13, 1801, ch. 4, §11, 2 Stat. 89, 92,

repealed by Act of March 8, 1802, ch. 8, 2 Stat. 132 38

PAGE

X l l l

Act of February 4, 1815, ch. 31, §8, 3 Stat. 198 ........ 40

Act of March 3, 1815, ch. 93, §6, 3 Stat. 233 ..... 40

Act of March 3, 1817, ch. 109, §2, 3 Stat. 396 ............ 40

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §1, 4 Stat. 632 . 40

Act of March 2, 1833, eh. 57, §2, 4 Stat. 632 . 40

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §3, 4 Stat. 633 . 40

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §5, 4 Stat. 634 . 40

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §7, 4 Stat. 634 . 41

Act of August 29, 1842, ch. 257, 5 Stat. 539 ................ 42

Act of March 3, 1863, ch. 81, 12 Stat. 755 .................... 43, 74

Act of March 3, 1863, ch. 81, §5, 12 Stat. 755 ....... 43, 48,107

Act of March 7, 1864, ch. 20, §9, 13 Stat. 1 7 ................ 44

Act of June 30, 1864, ch. 173, §50, 13 Stat. 241 ............ 44

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §1, 14 Stat. 2 7 ................ 56

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §2, 14 Stat. 27 .......... 22, 57, 63

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 27 ....... 55, 56, 57

Act of May 11, 1866, ch. 80, 14 Stat. 4 6 ........................ 49

Act of May 11, 1866, ch. 80, §3, 14 Stat. 46 ................ 74

Act of July 13, 1866, ch. 184, 14 Stat. 9 8 .................... 44

Act of July 13,1866, §67,14 Stat. 171 .......... 44

Act of July 13,1866, §68,14 Stat. 172 ................... 44

Act of July 16, 1866, ch. 200, §14, 14 Stat. 176 ............ 45,46

Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 27, 14 Stat. 385 ................ 48

Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 28, 14 Stat. 385 ................ 53

Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 28, §1, 14 Stat. 386 ....... 53, 71

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, 16 Stat. 1 4 0 ......... 66

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §1, 16 Stat. 1 4 0 .............. 66

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§2-7, 16 Stat. 1 4 0 ........ 66

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §8, 16 Stat. 1 4 2 .............. 66

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §16, 16 Stat. 1 4 4 ............ 65

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §17, 16 Stat. 1 4 4 ............ 67

PAGE

XIV

Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §18, 16 Stat. 1 4 4 ............ 67

Act of February 28, 1871, ch. 99, §16, 16 Stat. 438 .... 68

Act of April 20, 1871, ch. 22, 17 Stat. 13 ..... .............. 66, 68

Act of April 20, 1871, ch. 22, §1, 17 Stat. 1 3 ................ 65

Act of March 1,1875, ch. 114, 18 Stat. 335 .................... 68

Act of March 3, 1875, ch. 137, §§1-2, 18 Stat. 470 ........ 68

Act of March 3, 1887, ch. 373, §2, 24 Stat. 553, as

amended, Act of August 13, 1888, ch. 866, 25 Stat.

435 ....................................................................................... 82

Judicial Code of 1911, ch. 231, §31, 36 Stat. 1096........64, 70,

77,106

Judicial Code of 1911, ch. 231, §33, 36 Stat. 1097, as

amended by Act of August 23, 1916, ch. 399, 39

Stat. 532 ............................................................................ 117

Judicial Code of 1911, ch. 231, §297, 36 Stat. 1168 .... 70

Act of September 6, 1916, ch. 448, §2, 39 Stat. 726 .... 91

Act of February 24, 1933, ch. 119, §1, 47 Stat. 904 .... 18, 20

Act of March 8, 1934, ch. 49, 48 Stat. 399 .................... 18

Act of June 7, 1934, ch. 426, 48 Stat. 926 .................... 18

Act of June 25, 1936, ch. 804, 49 Stat. 1921 ...... 18

Act of June 29, 1940, ch. 445, 54 Stat. 688 .................... 19

Act of November 21,1941, ch. 492, 55 Stat. 779 ........ . 18,19

Act of June 25, 1948, ch. 645, 62 Stat. 846 ................18,19, 22

Act of May 24, 1949, ch. 139, §60, 63 Stat. 98 ............ 18,19

Act of May 10,1950, ch. 174, §1, 64 Stat. 158 ................ 19

Act of July 18, 1956, ch. 629, §201, 70 Stat. 573 ........ 24

Act of July 7, 1958, Pub. L. 85-508, §12, 72 Stat. 348 19

Act of March 18, 1959, Pub. L. 86-3, §14, 73 Stat. 11 19

PAGE

XV

Civil Eights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, §201, 78

Stat. 243 ...........................................3, 6,12,13,14, 95, 96,116

Civil Eights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, §203, 78

Stat. 244 ................................................. 7,12,13,14, 95, 97, 98

Civil Eights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, §901, 78

Stat. 266 ........................................................................ 3,12,14,

24, 27, 73

Ga. Code Ann., §26-3005 (1965 Cum. Supp.) ....... 7,11,115

Acts of Virginia, 1865-1866 (Act of Jan. 15, 1866) .... 62

E xiles of C ourt

PAGE

Fed. Eule Civ. Pro. 1 ......................................................... 23, 29

Fed. Eule Civ. Pro. 8(a) ................................................. 117

Fed. Eule Civ. Pro. 73(a) ................................................. 23

Fed. Eule Civ. Pro. 81(b) ............................................... 29

Fed. Eule Grim. Pro. 32(d) ............................................ 22

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 3 3 ............................. 22

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 3 4 .................................................. 22

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 35 ..... ............................................ 22

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 37(a)(1) ..................................... 20,24

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 37(a) (2) ........................ 7,13,17,18, 20,

22, 24, 25, 26

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 37 (b) ............................................ 24

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 37(c) ............................................ 24

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 38(a) ............................................ 24

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 38(b) ....................................... 24

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 38(c) ............................................ 24

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 39 .................................................. 24

Fed. Rule Crim. Pro. 54(b)(1) .......................... 17

Fed. Rule Crim. Pro. 57(b) ................................ 24

Fed. Rule Crim. Pro. 59 ....................................... 17

Orders Prescribing Rules of Court:

292 U. S. 661 ................................................................ 19

327 U. S. 825 ......................................................8,20,21,23

335 IT. S. 917 ................................................................ 21

335 IT. S. 949 ................................................................ 21

346 IT. S. 941 ................................................................ 21

350 U. S. 1019 .............................................................. 21, 22

Letter of Transmittal of Federal Criminal Rules

(1944), 327 IT. S. 823 ...................................................... 21

L egislative M aterials

H. Rep. No. 304, 80th Cong., 1st Sess. (1947) ........18,19, 23

H. Rep. No. 308, 80th Cong., 1st Sess. (1947) ............ 70

H. Rep. No. 352, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (1949), 2 IT. S.

Code Cong. Serv., 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (1949) ..... 18,19

9 Cong. Deb. (1833) ......................................................... 42

Cong. Globe, 27th Cong., 2d Sess. (1942) .... 43

Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 3d Sess. (Jan. 27, 1863) .... 44

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866)....45, 46, 47, 48, 49,

50, 53, 57, 58, 61, 62,

63, 64, 65,108,112

110 Cong. Rec. (1964) ..................................................... 72,91

xvi

PAGE

X V II

Ot h e r S ources

ALI Study of the Division of Jurisdiction Between

State and Federal Courts, Commentary, General

Diversity Jurisdiction (Tent. Draft No. 1, 1963) .... 38

Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions Affecting Fed

erally Guaranteed Civil Rights: Federal Removal

and Habeas Corpus Jurisdiction to Abort State

Court Trial, 113 U. Pa. L. Rev. 793 (1965) ............ 54,89

3 Blackstone, Commentaries (6th ed., Dublin 1775) .. 71

2 Commager, Documents of American History (6th

ed. 1958) .................... 61

Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruc

tion (1898) ........................................................................ 46

3 Elliot’s Debates (1836) ................................................. 39

1 Farrand, The Records of the Federal Convention

of 1787 (1911) .................................................................. 37

The Federalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) (Warner, Phila

delphia ed. 1818) ............................................................. 37, 39

1 Fleming, Documentary History of Reconstruction

(photo reprint 1960) ....................................................... 61

Frankfurter & Landis, The Business of the Supreme

Court (1927) .............. 70

Galphin, Judge Pye and the Hundred Sit-Ins, The

New Republic, May 30, 1964 ....................................... 103

Hart & Wechsler, The Federal Courts and the Fed

eral System (1953) ......... .................... .................... 36,37,38

PAGE

XV111

Lusky, Racial Discrimination and the Federal Law:

A Problem in Nullification, 63 Colum. L. Rev. 1163

(1963) ................................................................................ 28

McPherson, Political History of the United States

During the Period of Reconstruction (1871) ........ 61

Mishkin, The Federal “Question” in the District

Courts, 53 Colum. L. Rev. 157 (1953) ...................... 69

1 Morison & Commager, Growth of the American

Republic (4th ed. 1950) ............................................... 39, 40

1 Warren, The Supreme Court in United States His

tory (rev. ed. 1932) ....................................................... 39

Brief for Respondents Rachel et al., in Georgia v.

Tuttle, 377 U. S. 987 (1964) .................................. 12, 25,103

Petition for Certiorari, Anderson v. City of Chester,

0 . T. 1965, No. 443

PAGE

3 5

I n t h e

Supreme (Emtrt of % luttefc States

October T erm , 1965

No. 147

Georgia,

T homas R achel, et al.,

Petitioner ,

Respondents.

on w rit of certiorari to t h e u n ited states court of appeals

for t h e f if t h circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Opinions Below

The opinions below are appropriately referred to in

Georgia’s Brief (Br. 1-2). The opinion supporting the

judgment here for review is reported as Rachel v. Georgia,

342 F. 2d 336 (5th Cir. 1965) (R. 20). Rehearing was

denied at 343 F. 2d 909 (5th Cir. 1965) (R. 51).

Jurisdiction

The grounds on which the jurisdiction of this Court rests

are appropriately stated in the first paragraph and the

first sentence of the second paragraph of the section titled

“Jurisdiction” in Georgia’s Brief (Br. 2). This Court might

2

also review the remand order of the district court (R. 5-9)

as on petition for an original writ of mandamus directed

to that court. 28 U. S. C. §1651 (1964); E x parte Peru,

318 U. S. 578 (1943). Should this Court deem the exercise

of the latter jurisdiction appropriate, respondents respect

fully request that the Court consider this Brief as a peti

tion for mandamus, together with a motion for leave to file

the petition. See pp. 34-35 infra.

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes

and Rules Involved

1. The case involves the Supremacy Clause, Art. Y I,

cl. 2, of the Constitution of the United States and the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution.

2. The following statutes and rules are also involved:

28 U. S. C. §1443 (1964):

§1443. Civil rights cases.

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prose

cutions, commenced in a State court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot en

force in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the jurisdic

tion thereof;

(2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for refus

3

ing to do any act on the ground that it would be in

consistent with such law.

28 U. S. C. §1446(a) (1964):

§1446. Procedure fo r removal.

(a) A defendant or defendants desiring to remove

any civil action or criminal prosecution from a State

court shall file in the district court of the United States

for the district and division within which such action

is pending a verified petition containing a short and

plain statement of the facts which entitle him or them

to removal together with a copy of all process, plead

ings and orders served upon him or them in such action.

28 U. S. C. §1447(d) (1964) (as amended by Civil Eights

Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, §901, 78 Stat. 266):

§1447. Procedure a fter rem oval generally.

(d) An order remanding a case to the State court

from which it was removed is not reviewable on appeal

or otherwise, except that an order remanding a case

to the State court from which it was removed pursuant

to section 1443 of this title shall be reviewable by ap

peal or otherwise.

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, §§201, 203, 78 Stat.

243-244, 42 U. S. C. §§2000a, 2Q0Ga-2 (1964):

§2000a. Prohibition against discrimination or segrega

tion in places o f public accommodation.

(a) E qual access.

All persons shall be entitled to the full and equal

enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges,

4

advantages, and accommodations of any place of public

accommodation, as defined in this section, without dis

crimination or segregation on the ground of race, color,

religion, or national origin.

(b) Establishm ents affecting interstate commerce or

supported in their activities by State action as

places o f public accom modation; lodgings; facili

ties principally engaged in selling food fo r con

sumption on the prem ises; gasoline stations;

places o f exhibition or entertainment; other cov

ered establishments.

Each of the following establishments which serves

the public is a place of public accommodation within

the meaning of this subchapter if its operations af

fect commerce, or if discrimination or segregation by

it is supported by State action:

(1) any inn, hotel, motel, or other establishment

which provides lodging to transient guests, other

than an establishment located within a building

which contains not more than five rooms for rent

or hire and which is actually occupied by the pro

prietor of such establishment as his residence;

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter, soda fountain, or other facility principally

engaged in selling food for consumption on the prem

ises, including, but not limited to, any such facility

located on the premises of any retail establishment;

or any gasoline station;

(3) any motion picture house, theater, concert hall,

sports arena, stadium or other place of exhibition

or entertainment; and

5

(4) any establishment (A) (i) which is physically

located within the premises of any establishment

otherwise covered by this subsection, or (ii) within

the premises of which is physically located any such

covered establishment, and (B) which holds itself

out as serving patrons of such covered establishment.

(c) Operations affecting com m erce; criteria; “com

m erce” defined.

The operations of an establishment affect commerce

within the meaning of this subchapter if (1) it is one

of the establishments described in paragraph (1) of

subsection (b) of this section; (2) in the case of an

establishment described in paragraph (2) of subsec

tion (b) of this section, it serves or offers to serve

interstate travelers of [sic] a substantial portion of

the food which it serves, or gasoline or other products

which it sells, has moved in commerce ; (3) in the case

of an establishment described in paragraph (3) of sub

section (b) of this section, it customarily presents films,

performances [,] athletic teams, exhibitions, or other

sources of entertainment which move in commerce;

and (4) in the case of an establishment described in

paragraph (4) of subsection (b) of this section, it is

physically located within the premises of, or there is

physically located within its premises, an establishment

the operations of which affect commerce within the

meaning of this subsection. For purposes of this sec

tion, “commerce” means travel, trade, traffic, commerce,

transportation, or communication among the several

States, or between the District of Columbia and any

State, or between any foreign country or any territory

or possession and any State or the District of Colum

6

bia, or between points in the same State but through

any other State or the District of Columbia or a for

eign country.

(d) Support by State action.

Discrimination or segregation by an establishment

is supported by State action within the meaning of this

subchapter if such discrimination or segregation (1) is

carried on under color of any law, statute, ordinance,

or regulation; or (2) is carried on under color of any

custom or usage required or enforced by officials of the

State or political subdivision thereof; or (3) is re

quired by action of the State or political subdivision

thereof.

(e) Private establishments.

The provisions of this subchapter shall not apply

to a private club or other establishment not in fact

open to the public, except to the extent that the facili

ties of such establishment are made available to the

customers or patrons of an establishment within the

scope of subsection (b) of this section. (Pub. L. 88-

352, title II, §201, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 243.)

§20Q0a~2. Prohibition against deprivation of, in terfer

ence with, and punishment fo r exercising rights and

privileges secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l o f this

title.

No person shall (a) withhold, deny, or attempt to

withhold or deny, or deprive or attempt to deprive,

any persons of any right or privilege secured by sec

tion 2000a or 2000a-l of this title, or (b) intimidate,

threaten, or coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten,

7

or coeree any person with the purpose of interfering

with any right or privilege secured by section 2000a or

2000a-l of this title, or (c) punish or attempt to punish

any person for exercising or attempting to exercise any

right or privilege secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l

of this title. (Pub. L. 88-352, title II, §203, July 2, 1964,

78 Stat. 244.)

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3005 (1965 Cum. Supp.):

26-3005. R efusal to leave prem ises o f another when

ordered to do so by owner or person in charge.—It

shall be unlawful for any person, who is on the prem

ises of another, to refuse and fail to leave said prem

ises when requested to do so by the owner or any

person in charge of said premises or the agent or em

ployee of such owner or such person in charge. Any

person violating the provisions of this section shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof

shall be punished as for a misdemeanor. (Acts 1960,

p. 142.)

Fed. Rule Grim. Pro. 37 (a) (2):

(2) Time fo r Taking A ppeal. An appeal by a defen

dant may be taken within 10 days after entry of the

judgment or order appealed from, but if a motion for a

new trial or in arrest of judgment has been made with

in the 10-day period an appeal from a judgment of

conviction may be taken -within 10 days after entry of

the order denying the motion. When a court after trial

imposes sentence upon a defendant not represented

by counsel, the defendant shall be advised of Ms right

to appeal and if he so requests, the clerk shall prepare

8

and file forthwith a notice of appeal on behalf of the

defendant. An appeal by the government when au

thorized by statute may be taken within 30 days after

entry of the judgment or order appealed from.

Order of this Court, February 8, 1946, prescribing Rule

37(a)(2), 327 U. S. 825:

I t I s Ordered on this eighth day of February, 1946,

that the annexed Rules governing proceedings in

criminal cases after verdict, finding of guilty or not

guilty by the court, or plea of guilty, be prescribed

pursuant to the Act of February 24, 1933, c. 119, as

amended (47 Stat. 904; IT. S . Code, Title 18, §688)

for the District Courts of the United States, the United

States Circuit Courts of Appeals, the United States

Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and the

Supreme Court of the United States, and that said

Rules shall become effective on the twenty-first day of

March, 1946.

I t I s F u r th er Ordered that these Rules and the

Rules heretofore promulgated by order dated Decem

ber 26, 1944, governing proceedings prior to and in

cluding verdict, finding of guilty or not guilty by the

court, or plea of guilty, shall be consecutively num

bered as indicated and shall be known as the Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure.

F ebruary 8, 1946.

9

Questions Presented

I. Whether the court of appeals had jurisdiction to

review an order of the district court remanding to the

appropriate state court state criminal cases removed pur

suant to 28 U. S. C. §1443 (1964) where notice of appeal

was tiled sixteen days after the date of the remand order.

II. Whether a removal petition which alleges that the

petitioners are being prosecuted on state criminal trespass

charges for their conduct in attempting to obtain equal

service without racial discrimination in restaurants covered

by the public accommodations title of the Civil Eights Act

of 1964 thereby states a case for removal under 28 U. S. C.

§1443 (1964).

I I I . Whether, as a matter of pleading, respondents’ re

moval petition sufficiently alleges that they are being

prosecuted on state criminal trespass charges for their

conduct in attempting to obtain equal service without racial

discrimination in restaurants covered by the public accom

modations title of the Civil Eights Act of 1964.

IV. Whether the court of appeals properly directed the

district court, in remanding the case to it for hearing on the

allegations of the removal petition, to assume jurisdiction

if it were proved that respondents had been arrested and

charged for seeking service which was denied them “for

racial reasons” at the places of public accommodation

named in their petition.

10

Statement of the Case

February 17, 1964, the twenty respondents (hereafter

called defendants as they were in the district court) filed

in the United States District Court for the Northern Dis

trict of Georgia their petition for removal of state criminal

trespass charges pending against them for trial in the

Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia (R. 1-5). The

petition alleged that defendant Rachel and seven other de

fendants “were arrested on June 17,1963 when they sought

to obtain service, food, entertainment and comfort at Lebco,

Inc., d/b/a Leb’s, a privately owned restaurant opened to

the general public, 66 Lucid e Street, Atlanta, Fulton

County, Georgia” (R. 2). The remaining defendants were

arrested at Leb’s on other dates in May or June of 1963, or

at one of four other restaurants, cafeterias or hotels opened

to the general public on dates between March and June

of 1963 (R. 2-3). Each establishment where arrests were

made was identified in the petition by name and street

location in the city of Atlanta (R. 2-3), except that no

street location was recited for the Henry Grady Hotel,

which was alleged to be “built on real estate owned by the

State of Georgia but leased for a term of years to the

H. & G. Hotel Corporation” (R. 3). Several of the defen

dants were arrested in attempts to obtain service at more

than one of these establishments and/or on more than one

date (R. 2-3). “ [T]heir arrests were effected for the sole

purpose of aiding, abetting, and perpetuating customs, and

usages which have deep historical and psychological roots

in the mores and attitudes which exist within the City of

Atlanta with respect to serving and seating members of the

Negro race in such places of public accommodation and con

11

venience upon a racially discriminatory basis and upon

terms and conditions not imposed upon members of the so-

called white or Caucasian race. Members of the so-called

white or Caucasian race are similarly treated and dis

criminated against when accompanied by members of the

Negro race” (R. 1-2). Each defendant was subsequently

indicted under Georgia’s 1960 criminal trespass statute,

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3005 (1965 Cum. Supp.), penalizing re

fusal to leave premises on request of the owner (see p. 7

supra) (R. 3-4).

Prosecutions growing out of these arrests and indictments

were sought to be removed to the federal court under au

thority of 28 U. S. C. §§1443(1), (2) (1964), p. 2 supra

(R. 4), “to protect the rights guaranteed . . . under the

due process and equal protection clauses of [the] . . .

Fourteenth Amendment . . . and to protect the right of

free speech, association and assembly guaranteed by the

F irst Amendment . . . ” (R. 4). I t was alleged that the

defendants were prosecuted for acts under color of au

thority derived from the federal Constitution and laws (R.

4), and that they were denied and could not enforce in the

Georgia courts their rights under federal law providing for

equal rights, “in that, among other things, the State of

Georgia by statute, custom, usage, and practice supports

and maintains a policy of racial discrimination” (R. 4).

February 18,1964, District Judge Royd Sloan, sua sponte

and without hearing, remanded the prosecutions to the Su

perior Court of Fulton County (R. 5-9). March 5, 1964, de

fendants filed a notice of appeal from that order (R. 9).

March 12, they filed in the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit a motion for a stay of the remand order (App. la-3a,

in fra). The same day, Georgia filed a motion to dismiss

12

the appeal (R. 10-13). That date, March 12, 1964, the court

of appeals granted defendants’ motion for a stay and

postponed the disposition of Georgia’s motion to dismiss

until hearing on the merits (R. 13-14). Georgia there

upon moved this Court for leave to file a petition for pre

rogative writs, commanding the judges of the court of

appeals to vacate their stay order and proceed no further

with the appeal. June 22, 1964, the Court denied the mo

tion without opinion. Georgia v. Tuttle, 377 U. S. 987

(1964).*

July 2, 1964, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted

into law. Pub. L. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241. December 14, 1964,

this Court held in Hamm v. City o f Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306

(1964), that sections 201 and 203 of that act, portions of the

public accommodations title, see pp. 3-7 supra, precluded

state criminal trespass conviction of sit-in demonstrators

who had refused to leave covered establishments from which

they were ordered for racial reasons, even though the sit-

ins occurred, and their prosecutions had been instituted,

prior to the effective date of the 1964 act. March 5,1965, the

court of appeals rendered its opinion and judgment in the

present case, reversing the remand order of the district

court (R. 20-36). Sustaining its appellate jurisdiction under

28 U. S. C. §1447(d) (1964), as amended by section 901 of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 stat. 266, the court held that

defendants’ removal petition adequately alleged that their

prosecutions were in violation of sections 201 and 203 of

the act as construed in Hamm. The court concluded that, if

these allegations were true, criminal prosecution of de

fendants in the Georgia courts denied them their rights

* For the events leading up to this prerogative writ proceeding,

see the documents in the Appendix to Brief for Respondents Rachel

et al., Georgia v. Tuttle, 377 U. S. 987 (1964), pp. 24-51.

13

under §§201 and 203, and made them unable to enforce these

rights, within the meaning of the civil rights removal stat

ute’s first subsection, 28 U. S. C. §1443(1). Without reach

ing any question of the removal petition’s sufficiency under

§1443(2), the court of appeals therefore remanded the case

to the district court for hearing, instructing the district

court to give the defendants “an opportunity to prove the

allegations in the removal petition as to the purpose of the

arrests and prosecutions, and in the event it is established

that the removal of the [defendants] . . . from the various

places of public accommodations was done for racial rea

sons, then under authority of the Hamm case,” to accept

removal jurisdiction and dismiss the prosecutions (R. 31-

32). Georgia’s petition for rehearing en banc (R. 37-49) was

denied April 19, 1965 (R. 51), and this Court granted

Georgia’s petition for certiorari October 11, 1965 (R. 52).

Summary of Argument

I.

The court of appeals did not lack jurisdiction to review

the remand order by reason of untimeliness in filing defen

dants’ notice of appeal. The notice was timely filed. The

ten-day appeal period limited by F ed . R u le Cr im , P ro.

37(a)(2) was prescribed under this Court’s post-verdict

criminal rule-making power and, by the terms of the order

prescribing it, has no application to appeals before verdict

in criminal cases.

Even were Criminal Rule 37(a)(2) applicable, the court

of appeals had jurisdiction to proceed as on petition for

mandamus, without limitation of time. The prerogative writ

14

is the traditional and accepted mode of review of remand

orders, and section 901 of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 pre

serves it as an alternative to appeal. The court of appeals

had the power to treat the present proceeding as before

it on petition for the writ. Should its appellate jurisdiction

be held wanting, the case ought to be remanded to that

court for its determination whether to entertain it as a

prerogative writ proceeding.

However, this Court need not decide any question of the

jurisdiction of the court of appeals in order to reach the

significant and pressing question of removability which the

case presents. The Court might review the remand order

of the district court as on an original petition for mandamus

to that court. The importance of expeditious construction

of the civil rights removal statute justifies the exercise

of the Court’s discretion to so proceed.

n.

Persons criminally prosecuted for attempts to obtain de

segregated restaurant service in the exercise of their equal

civil rights under the public accommodations title of the

Civil Eights Act of 1964 are thereby denied these rights,

and made unable to enforce them, within the meaning of 28

U. S. C. §1443(1). Pending prosecution constitutes intimida

tion and punishment forbidden by section 203 of the 1964

act and an impermissible repression of' the right to restau

rant service free of racial discrimination given by section

201. Federal removal jurisdiction is required to protect

this right from destruction by mesne process during the

delays incident to state court criminal proceedings. There

fore, persons prosecuted may sustain removal under

§1443(1) without inquiry into the questions whether the

1 5

state statute under which they are charged is unconstitu

tional on its face or whether the state courts will not

fairly entertain their federal defenses. The former inquiry

is required by the decisions of this Court only where fed

eral procedural rights, not where federal substantive rights,

are implicated in the state prosecution. The latter inquiry

is entirely impracticable, and is never required under

§1443(1).

Persons prosecuted for the exercise of their right to equal

public accommodations under the Civil Rights Act of 1964

are also thereby prosecuted for an act under color of au

thority derived from the 1964 legislation, within the mean

ing of 28 U. S. C. §1443(2). The legislative history of

§1443(2) and its context in the present Judicial Code in

dicate that its protection is available to private individuals,

not merely to federal officers and those acting under them.

As applied to private individuals, “color of authority” de

rived from civil rights law means the license to act which

these laws give, free of every sort of repression. In no

other sense do federal civil rights laws give authority

to private conduct.

Narrow construction of the civil rights removal juris

diction would defeat the great purpose of the Reconstruc

tion Congresses to extend effective federal judicial protec

tion to the civil liberties which the post-war Amendments

guaranteed. The liberties secured by these Amendments

and by federal civil rights legislation are perpetually in

jeopardy so long as state criminal proceedings may be

used to harass the individuals who dare exercise them.

The civil rights removal jurisdiction is a needed shield

against such harassment.

16

III.

Defendants’ removal petition was not deficient as a plead

ing. It sufficiently alleged each of the three elements re

quired for removal under a proper construction of 28

U. S. C. §1443: that defendants were (1) prosecuted for

criminal trespass for refusal to leave (2) places of public

accommodation covered by the Civil Eights Act of 1964, (3)

where they were ordered out and then arrested by reason

of racial discrimination.

IV.

The court of appeals properly directed the district court,

in remanding the case to it for hearing on the allegations

of the petition, to determine whether the trespass charges

against defendants arose from their refusals to leave places

of public accommodation which they were ordered to leave

for racial reasons. Such a showing brings defendants

within the protection of the public accommodations sec

tions of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, hence of the removal

statute. Georgia does not and cannot seriously contest

coverage of the restaurants in question under the 1964 act,

and the attack made on the foreclosing of other issues on

remand demonstrates only Georgia’s misconstruction of the

removal statute or the court of appeals’ opinion.

17

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Court of Appeals Did Not Lack Jurisdiction of the

Appeal by Reason of Asserted Untimeliness in Filing

the Notice of Appeal.

Because defendants’ notice of appeal, March 5, 1964 (R.

9), was filed more than ten days after the district court’s

order of February 18, 1964 (R. 5-9) remanding their prose

cutions to the state trial court, Georgia urges that the

court of appeals lacked jurisdiction to entertain any pro

ceeding by defendants for review of that order (Br. 13-29).

The argument is that these removed prosecutions are crimi

nal proceedings (Br. 21); that the Federal Rules of Crimi

nal Procedure apply to them by virtue of Rules 54(b)(1)

and 59 (Br. 21-28); that therefore the ten-day appeal period

of Rule 37(a)(2) governs the case (Br. 13-21); and that

failure to file a notice of appeal within the ten-day period is

fatal to the jurisdiction of the court of appeals (Br. 29).

Defendants have no controversy with any but the essential

part of this. They agree that their prosecution is criminal,

that the Federal Criminal Rules govern it at every stage

subsequent to the perfection of federal removal jurisdic

tion by filing and service of their removal petition (see 28

U. S. C. §1446(e) (1964)) on February 17, 1964 (R. 1-5),

and that any applicable appeal period fixed by those rules

goes to the jurisdiction of the circuit court. They share the

view of that court, however, that the ten-day period of

Rule 37(a)(2) does not apply to pre-verdict appeals in any

criminal case, removed or original, governed by the Crimi

nal Rules. And they assert, in any event, that the court

1 8

of appeals clearly had jurisdiction to review the remand

order by prerogative writ, unencumbered by the time

limited by any rule governing appeal.

A. As R u le 3 7 ( a ) ( 2 ) Hag No A pplication to Pre-V erd ict

A ppeals, th e Notice o f A ppeal W as T im ely F iled .

This Court’s power to make rules governing practice and

procedure in federal criminal proceedings derives from two

distinct sources. By the Act of February 24, 1933, ch. 119,

§1, 47 Stat. 904, amended by the Act of March 8, 1934, ch.

49, 48 Stat. 399, the Court was authorized to promulgate

“rules of practice and procedure with respect to any or all

proceedings after verdict, or finding of guilt by the court if

a jury has been waived, or plea of guilty, in criminal cases.

. . . ” That authority is presently codified, substantially

unchanged, in 18 U. S. C. §3772 (1964), as amended.1 Buies

1 The 1933 act authorized rule-making with respect to proceed

ings “after verdict.” Its 1934 amendment expanded the authority

to proceedings “after verdict, or finding of guilt by the court if

a jury has been waived, or plea of guilty,” apparently for the

reason that no distinction seemed justified in post-conviction rules

for jury-tried and jury-waived eases. See Nye v. United States,

313 U. S. 33, 44 (1941). The Nye case held that this language failed

to reach proceedings for criminal contempt. Congress responded

by the Act of November 21, 1941, ch. 492, 55 Stat. 779, extending

the 1933 authorization to criminal contempt eases. These three

statutes were the basis for present 18 U. S. C. §3772, enacted in

the criminal code revision of 1948. Act of June 25, 1948, eh. 645,

62 Stat. 846-847. (The revisers’ note also mentions the Act of

June 7, 1934, eh. 426, 48 Stat. 926, and the Act of June 25, 1936,

ch. 804, 49 Stat. 1921, which changed the names of the trial and

appellate courts in the District of Columbia; the 1948 revision

itself made some other changes in phraseology but none in sub

stance. See H. R ep . No. 304, 80th Cong., 1st Sess. A177-A178

(1947).) Section 3772 was amended by the Act of May 24, 1949,

ch. 139, §60, 63 Stat. 98, to correct the nomenclature of several

courts and a typographical error, see II. R ep . No. 352, 81st Cong.,

1st Sess. (1949), 2 U. S. Code Cong. S erv., 81st Cong., 1st Sess.,

1949, 1264; amendments in 1958 and 1959 merely accommodated

19

announced under it (which we may call in shorthand “post

verdict rules”) become effective without submission to Con

gress. By the Act of June 29, 1940, ch. 445, 54 Stat. 688,

the Court was authorized to prescribe “rules of pleading,

practice, and procedure with respect to any or all proceed

ings prior to and including verdict, or finding of guilty or

not guilty by the court if a jury has been waived, or plea

of guilty, in criminal cases . . . . ” This second authority is

presently codified, substantially unchanged, in 18 IT. S. C.

§3771 (1964), as amended.2 Rules announced under it

(which we may call in shorthand “pre-verdict rules”) be

come effective only upon submission to Congress.

The Court first exercised its post-verdict rule-making

authority by an order dated May 7, 1934 which explicitly

invoked the 1933-1934 legislation, see 292 IT. 8 . 661, in

adopting eleven rules “as the Rules of Practice and Pro

file admission to statehood of Alaska and Hawaii respectively. Act

of July 7, 1958, Pub. L. 85-508, §12(1), 72 Stat. 348: Act of

March 18, 1959, Pub. L. 86-3, §14 (h), 73 Stat. 11.

2 The Act of November 21, 1941, ch. 492, 55 Stat. 779, extended

the pre-verdict 1940 authorization, as well as the post-verdict 1933

authorization, to criminal contempt cases. See note 1 supra. The

1940 and 1941 acts were codified in 1948 as 18 U. S. C. §3771. Act

of June 25, 1948, ch. 645, 62 Stat. 846; see H. R ep . No. 304, 80th

Cong., 1st Sess. A-177 (1947). The Act of May 24, 1949, ch. 139,

§59, 63 Stat. 98, made some changes in judicial nomenclature and

authorized transmission of the rules to Congress by the Chief Jus

tice instead of by the Attorney General as theretofore, see H. R ep .

No. 352, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (1949), 2 U. S. Code Cong. S erv.,

81st Cong., 1st Sess., 1949, 1264. The Act of May 10, 1950, ch. 174,

§1, 64 Stat. 158 altered the time at which the rules might be

submitted to Congress and the period after submission when they

were to take effect. Acts in 1958 and 1959 amended language in

the section to accommodate the admission to statehood of Alaska

and Hawaii respectively. Act of July 7, 1958, Pub. L. 85-508

§12 (k), 72 Stat. 348; Act of March 18, 1959, Pub. L. 86-3, §14(g )’

73 Stat. 11.

20

cedure in all proceedings after plea of guilty, verdict of

guilt by a jury or finding of guilt by the trial court where

a jury is waived, in criminal cases . . . . ” Ibid. Rule III,

governing appeals, prescribed that appeal should be “taken

within five (5) days after entry of judgment of conviction”

(except where a motion for new trial was pending), abol

ished petitions for allowance of appeal and citations, pro

vided that appeal should be taken by filing a notice of

appeal in duplicate in the district court and serving it on

the government, and described its contents. 292 U. S. 662-

663. In 1946, by order dated February 8, the Court pre

scribed Rules 32 to 39 of the new Federal Rules of Criminal

Procedure, effective March 21, 1946. 327 U. S. 821, 825.

It was thereby ordered that these “Rules governing pro

ceedings in criminal cases after verdict, finding of guilty

or not guilty by the court, or plea of guilty, be prescribed

pursuant to the Act of February 24,1933, c. 119, as amended

(47 Stat. 904, U. S. Code, Title 18, §688).” 327 U. S. 825.

Rule 37(a)(2) prescribed that appeal by a defendant should

be “taken within 10 days after entry of the judgment or

order appealed from” (unless a motion for new trial or in

arrest of judgment was pending), required the court to

advise an unrepresented defendant of his right to appeal

following sentence after trial and the clerk to prepare and

file a notice of appeal on request of such a defendant, and

prescribed that an appeal by the government when author

ized by statute should be “taken within 30 days after entry

of the judgment or order apealed from.” 327 U. S. 857-858.

Rule 37(a)(1) provided that appeal should be taken by

filing a notice of appeal in duplicate in the district court,

described its form and contents, abolished petitions for al

lowance of appeal, citations and assignments of error, and

directed the clerk of the district court to notify the adverse

21

party of the appeal and to forward the duplicate notice to

the appellate court with a statement of docket entries. 327

U. S. 857. The rule, which was never submitted to Congress,

is in substance present Rule 3 7 (a ); two subsequent amend

ments—both put into effect without submission to Con

gress—have not changed it in any respect material here.3

On March 21, 1946 Rules 1 to 31 and 40 to 60 of the Fed

eral Rules of Criminal Procedure also became effective.

These had been prescribed to govern “proceedings in crimi

nal cases prior to and including verdict, finding of guilty

or not guilty by the court, or plea of guilty . . . pursuant

to Act of June 29, 1940, ch. 445, 54 Stat. 688.” (Letter of

transmittal from Chief Justice Stone to Attorney General

Biddle, December 26, 1944, 327 IT. S. 823; see id. at 821.)

They became effective following submission to Congress

as required of pre-verdict rules by the 1940 act; subsequent

amendments to them have similarly been submitted.4

Thus the procedural history and explicit language of the

order promulgating Rule 37 make clear that it applies—

because it can only apply—to appeals “after verdict, find

ing of guilty or not guilty by the court, or plea of guilty.”

327 U. S. 825. To apply it to pre-verdict appeals would

attribute to this Court disregard of the specific command

of Congress that pre-verdict rules be submitted to its

scrutiny before they take effect. Georgia’s suggestion (Br.

8 By order dated December 27, 1948, effective January 1, 1949,

the Court substituted the language “court of appeals” for “circuit

court of appeals,” conforming the rule to the phraseology of the

Judicial Code revision of 1948. 335 U. S. 917-918. By order of

April 12, 1954, effective July 1, 1954, contemporaneous with its

adoption of Revised Rules of the Supreme Court, the Court rewrote

Criminal Rule 37 to provide that appeals and petitions for cer

tiorari to the Court were governed by its revised rules. 346 U. S.

941-942.

4 E.g., 335 U. S. 949; 350 IT. S. 1019.

22

16-17) that the codifiers’ cross-reference to Rule 37 in the

1948 Criminal Code, Act of June 25, 1948, ch. 645, 62 Stat.

845, satisfies the submission requirement is extravagant.

Apart from the consideration that this Court has since

amended the Rule without resubmission, 346 U. S. 941-942;

see note 3 supra, the cross-reference is palpably devoid of

substantive effect and—even were it given such effect—

could mean nothing more than acceptance of the rule in the

form in which the Court promulgated it : as a post-verdict

rule. Georgia also has the argument (Br. 17-19) that the

30-day limitation for government appeals in Rule 37(a)(2)

compels construction of that rule as applicable to pre-verdict

appeals. This would be the case only if all government

appeals allowed by statute were pre-verdict appeals, but of

course they are not. See 18 U. S. C. §3731 para. 7 (1964).

Rule 37(a)(2) is, as Georgia suggests, “a nullity as to ‘be

fore verdict’ appeals” by the government (Br. 18), where

such appeals are authorized by statute. See 18 U. S. C.

§§1404, 3731 para. 6 (1964). Its sole purpose is to assure

that the 30-day limitations prescribed by each of these

statutes, see the last sentence of §1404 and paragraph 8

of §3731, are not deprived of force by any implication

derived from Rule 37. See 18 U. S. C. §3772, para. 3 (1964).

Georgia’s contention (Br. 19) that the limitation by Rule

37(a)(2) of a period of ten days “after entry of the judg

ment or order appealed from”-—as contrasted with the

limitation by former Rule I I I of a period “after entry of

judgment of conviction,” 292 U. S. 662,—comports a pur

pose of Rule 37(a)(2) to reach some pre-verdict “order,”

exhibits the same vice of reasoning. The contention would

be tenable if no appealable “order” could be made in a

criminal case after verdict; but see Rules 32(d), 33, 34,

35. The specification of “order” in Rule 37(a)(2) is un

2 3

doubtedly designed principally to reach orders denying

motions for correction of sentence under Eule 35, see Heflin

v. United States, 358 IT. S. 415, 418 n. 7 (1959), in light of

the revelations of United States ex rel. Coy v. United

States, 316 TJ. S. 342 (1942), and M eyers v. United States,

116 F. 2d 601 (5th Cir. 1940).

Indeed, Georgia’s arguments in this aspect would hardly

merit debate5 but for the awkward circumstance that they

point up a casus omissus in the Criminal Eules.6 I f Eule

37(a) (2) is properly read as applicable only to post-verdict

appeals, there is no time limited by the Eules for pre

verdict appeals.7 The omission is of scant practical signifi

6 The order promulgating Rule 37 and its companion rules, con

taining an explicit restriction of their operation to post-verdict

proceedings, 327 U. S. 825, came five years after Nye v. United

States, 313 U. S. 33 (1941), had clearly established that such

explicit restrictions “describe the kinds of cases to which [the rules]

. . . are to be applied.” Id. at 44.

6 Obviously, foresight of every case which may arise in admin

istration of a system of criminal rules is impossible, and it has

previously occurred that lacunae have been discovered in the

Federal Rules. See United States ex rel. Coy v. United States, 316

U. S. 342 (1942) ; Lott v. United States, 367 U. S. 421 (1961) ;

United, States v. Healy, 376 U. S. 75 (1964). One cardinal virtue of

judicial rule-making is that such problems may be effectively cor

rected by the judiciary, whose concern they principally are, and

that correction may be made without unfair surprise to individual

litigants.

7 Defendants agree with Georgia (Br. 27) that neither F ed.

R ule Civ. P eo. 73(a) nor 28 TJ. S. C. §2107 (1964) can be applied

to limit the time for pre-verdict appeals in criminal cases. The

reach of Rule 73 is restricted to civil actions by F ed. Rule Civ. P ro.

1; and the similar restriction of §2107, in contrast to its predecessor,

28 TJ. S. C. §230 (1940), is not inadvertent. See IT. Rep . No. 308,

80th Cong., 1st Sess. A174 (1947). The exclusion of criminal

appeals from the latter section by reason of the revisers’ view that

Criminal Rule 37 governed such appeals, cannot of course be taken

to imply that the revisers or Congress thought Rule 37 applicable

to pre-verdict criminal appeals. They, like this Court in promul

2 4

cance, because the strong tradition against interlocutory

criminal appeals in federal practice disallows pre-verdict

appeal altogether except where expressly authorized by

statute, see DiBella v. United States, 369 U. S. 121 (1962);

Cobbledick v. United States, 309 IT. S. 323 (1940); P arr v.

United States, 351 IT. S. 513 (1956), and each of the few

extant statutory authorizations has a built-in limitations

period. See 18 U. S. C. $§1404, 3731 (1964).8 The sole

exception is the statute under which the present case

arises: 28 IT. S. C. §1447(d) (1964), as amended by §901 of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, 78 Stat. 266,

to provide that “an order remanding a case to the State

court from which it was removed pursuant to section 1443

of [title 28] . . . shall be reviewable by appeal or otherwise.” 9

gating the Criminal Rules, had no occasion to direct their attention

to pre-verdict appeals—a rare form of proceeding whose timeliness

was otherwise regulated by statute. When Congress did subse

quently address the question—authorizing interlocutory appeals

from suppression orders in narcotics cases by the Act of July 18,

1956, ch. 629, §201, 70 Stat. 573, 18 IT. S. C. §1404 (1964)—it did

not assume the applicability of Criminal Rule 37, but included a

thirty-day limitation in the act.

8 It is true, of course, that if Rule 37(a)(2) does not govern

pre-verdict proceedings, neither do any of the provisions of Rules

32-39. This is not a matter of moment, however. Rules 32-36, the

second sentence of Rule 37 (a )(2 ), and Rule 38(a) are, by the

nature of their provisions, inapplicable at pre-verdict stages. Rules

37(b), (c) and 38(b) are merely cross-references to other rules

applicable of their own force. Rules 37 (a )(1 ), 38(c) and 39 are

chiefly housekeeping regulations; authority to proceed in the few

rare pre-verdict appeals with respect to the matters covered by

these rules is amply conveyed by Rule 57(b).

9 The present case was removed, remanded, and an appeal from

the remand order taken prior to the enactment of §901. The court

below held that the statute nevertheless governed the case (R.

20-21), under the ordinary principle that procedural legislation—

including legislation affecting the jurisdiction of particular courts

e.g., Bruner v. United States, 343 U. S. 112 (1952)—is applied to

2 5

Even in §1443 (civil rights removal) cases, absence of a

provision limiting the time for appeal of remand orders is

of little importance because, as indicated in the next section

of this brief, the traditional mode of review of remand

orders by prerogative writ which was revived by the “other