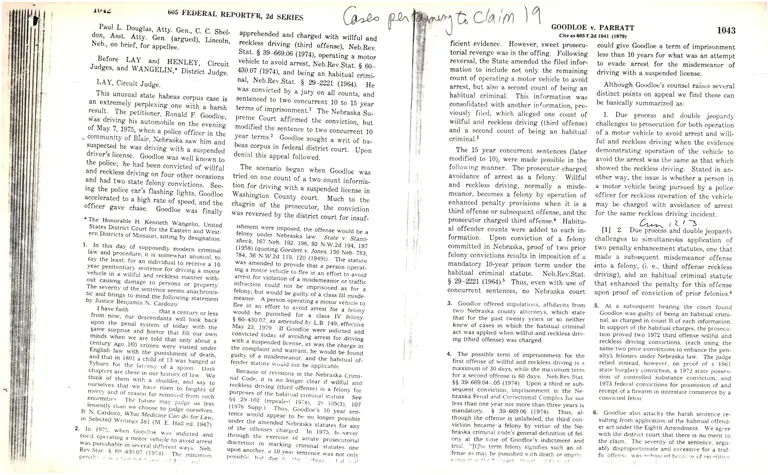

Attorney Notes; Goodloe v. Parratt Court Opinion

Working File

August 28, 1979

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Attorney Notes; Goodloe v. Parratt Court Opinion, 1979. ef3f5c59-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2a873509-2d88-4d37-9603-27ae5e5c6c1e/attorney-notes-goodloe-v-parratt-court-opinion. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

tv,,l 605 FEDERAL REPORTFR" 2d SqRIES Ca^^ p^ 6clain \1

l. Jn this da). of suo

r, * uno' plJi.;il,"1ir,:'::*"IffiffiTl ilsay the least, for an indr'idual ;;;.;;il;';;year penirentrar). senrence ro. o.iring-"' _ltolvehicle in a u.illful and reckless ;;;r;.ffi;:out causing damape,'"'"*,i ii ;il':",'"#":: ::fi ,.j,::;:;I :

j

rrc and brings to mind tfre rofrowinJ.;;;;;H;

by' Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo.

I have faith

rro. no*l"o* a".""nat#,t " j,,:1,ffiuo;:".T

:l:l ,h. penal s).stem of today

".iit-iiiiame surpnse and horror ttrat fitt ";;-";;minds when \.!.e are totd ,t"i

""irX"r,,-lcentury ago 160 crir

engrisi ;'; ;il i,iffiil;ffiff,,:i J;fi.and that in r8ol a "nirj or iJ'*r; #d;;,:iTt'burn for the lrr,l,

.,r,, p,

"..' i." ;'" # i ; "J;', ;i,,: jr"T,:_ "ii:thrnk of them Bith

ourseri.es that *-e ,.,r1 -'tnyor"r,

and say to

merc5 arrd or.""ro,,11", ffi:,:.". ir"i:i:i,.Tenormitir.s l.he furr

Ienrentlf ,t,or,'*=

ruulre nla-v jLidge us less

B N

.Cardozo- u;

"

;' ;:;,", ;""ii"t"J?;:".X:in Selected \i,rrrirrgs 381 (I,t. O. Hr,i

"U.

,rr-iil.

2,.-In, 1g75. ia,hen Goo(llDe u.us indicted andlrleJ, oper.atjng a motor

".fri.f" to,",rn-lal.I.iu'as punishable in sercral d,ffer*r,t ;;;; "ir;:

Rer..Srir. S On .llO OZ i

pen,,!.. , ;. , ,,,'l:':.",1 ."Y.1'' ,T" ml,rrinrrrrn

, Paul L. Douglrrs, Atty. Gen., C. C. Shel_don, Assr. Atty. Gen. 1""gr"ai ;i#,r.Neb., on brief, ior appellee.o---"

sr'revrrt'

,..Yuro.u l1y and HENLEY, CircuirJudges, and WANGEI,IX; n:J.i., ila*.:

LAy, Circuit Judge.

This unusual state habeas corpus case isan extremely perplexing on"

"iir,-"-il".t,result. The petitioner, "Ronald

F. coffi;:fas_driving his automobile on the ;;;;,;:of May ?,lg71, u,hen a poli.u offi.u. in'ttE*lommyni.ty of Blair, Nebraska ."* f,ir'""Jsuspected he was driving *.ith a .r*;;;;driver's license. Goodloe-was *JI-lrrl,", i"the police; he had been convicted of willfuland reckless driving on four

"th"; ;;.*;;;.and had two state

-felory

convictions. See-ing the police car,s fla.hing lig;t.,';#;;

accel_erated to a high rate of ,p""a,

""jli"olllcer gave chase. Goodlos *". -ii""iry,

* The Honorable H. Kenneth Wangelin, UnitedStares District Coun foi trr" e"rt"i"'r"r"#;:Tern Districts of Missouri, .i,,trg Ui: lJe"",il.

apprehended and charged with willful andreckless driving (third offens"), N;.R";.

star.. g B9-669.06 (tsl 4), or""ti;r;;;;*

vehicle to avoid arest, Nel.Rer.Siut.

S

=d

430.07 (1974), and being ,n f,uUitr"i *inii_nal, Neb.Rev.Stat. g n_znl (1964). ;;

r.r'as convicted by a jury on all counts, andsentenced to two concument l0 to 15 vearterms of imprisonment.t The N"U.^t"'S]_

preme Court affirmed the convictior, ir,modified the sentence to two.on.r"r.nt t0year terms.2 Goodloe sought a writ of ha_

beas corpus in federal distiict .";;;. ;;;;denial this appeal followed.

. .The scenario began when Goodloe wastried on one count of a two count inform!_

lj:".t:. driving with a suspended license in

Y*hir"r"-" County court. Much to thecnagTln of the prosecutor, the conviction

was reversed by the district court for insJ

ishment u.ere imposed, the offense would be afelony under Nebraska law. S*" ;'';r;;r:sfreck, t6z Neb. 192, rS6, sZ N.w.ia ,ri,,-iii(1958) (quoting Goedert v. Jones, rrO ile"c,rr;:78,1, 36 N.W.2d lr9, r20 o949)j til:;";;;was amended to provide ,tut u'p"rron ;;.;:;:rng a motor vehrcle to flee in an

"rr"" i" ir:roarrest for violation of a rrusdemeano, o. ,iri,linfracrion could not be jmprisoned ; ;;;^,;

Il.^11,

Orl u.outd be guitr). of a class Iil mrsde_m€anor. A person operating a motor r;;;;l;;

I,"*.i: ln effort to a'oid arrest f.. ; ';;;;,;;woutd be punished for a class l"-,elo"nri

!.6o1|0 07. as amended al. r_ e l+9, .ri".,,rr"May 23,.1979 If Goodloe were indicted andconvicted toda), of avoidi

witrr a susienilr";,;;"r'":'19

arrest for. dnving

rh.. .o-pr;;;;;; ;;;,1i:TJl,: .*:il:

guiltl' of a misdemeanor, and the habrtual of_lender statute s.uuid not be applrcable

felalse ot re\isions in the Nebraska Cnmi-

ll,-l:1":, ir is no ronger crear if witrful andreckless dri\.ing (third offense) i. " f;i";;;;l:rrT.,se-s of the habir,ral crimrnal ,r,,tu,"., SJ"\\^ 29 102 (repeale,t lgiu), ,. ,rSfil, IOi

11978

sunp ) Thus, Goodroe'r ro ;;;; ;;-tence would appear to be no longei ;.r,;j;runder the amended Nebraska .,utr,u, ?;; ;;;ol the oflenses chargcd. I" fSZS. 1,.;"r.;'through the exercjse of

:::i,", . "';:;; ":#:;f :;,"",::,.;Jupon.another. a I0 .v_ear sentence u.as not onl\.l)ossihl,'. hrrt drre r. :r^. .hra. l.rt , r!

GOODLOE v. PARRATT

Clte rs 605 F3d t(Xt (1920)

r043

ficient evidence. However, sweet prosecu- could give Goodloe a term of imprisonment

torial revenge was in theoffing. Following less than 10 years for what was an attempt

reversal, the State amended the filed infor- to evade arrest for the misdemeanor ofmation to include not only the remaining driving with a suspended license.

count of operating a motor vehicle to avoid

arrest, bui also a second count of lreing an Although Goodloe's counsel raises several

habitual criminal. This information was distinct points on appeal we find these can

consolitlated with another information, pre- be basically summarized as:

viously filed, r,r'hich alleged one count of l. Due process and double jeoparcll.

willful and reckless driving (third offense) challenges to prosecution for both operation

and a second count of being an habitual of a motor uuhi.lu to avoid arrest and r+,ilL-criminal.3 ful and reckless driving when the evidence

The 15 year concurrent sentences (latrer demonstrating operation of the vehicle to

modified to 10), were made possible in the avoid the arrest was the same as that which

follorving manner. The prosecutor charged shorved the reckless <iriving. Stated in an-

avoidance of arrest as a felony. Willful other way, the issue is whether a person in

and reckless driving, normally a misde- a motor vehicle being pursued by a police

meanor, becomes a felony by operation of officer for reckless operation of the vehicle

enhanced penalty provisions when it is a may be charged with avoidance of arrest

third offense or subsequent offense, and the for the same ieckless driving incident.

prosecutor charged third offense.r Habitu_ f_,- / t / Jal offender counts were added to each in- tll z. Due"offi, und dorbtu jeopardr

formation. Upon conviction of a felony challenges to simultaneoLs application of

committed in Nebraska, proof of two prior two penalty enhancement statutes, one that

felony convictions results in imposition of a made a subsequent misdemeanor offense

mandatory l0-year prison term under the into a felony, (i. e., third offense reckless

habitual criminal statute. Neb.Rev.Stat. driving), ahd an habitual criminal sratute

S 29-221 (1964).5 Thus, even with use of that enhanced the penalty for this offense

concurrent sentences, no Nebraska court upon proof of conviction of prior felonies.6

3' Goodloe offered stipulations, affidavits from 5. At a subsequent hearing ihe court foundtu'o Nebraska county attorne5.s, which state Goodloe \.\.as guilt), of being an habitual crimi_that for the past twenty years or so neither nal, as charged in count II of each information.knew of cases in which the habitual criminal In support of the habitual charges, the prosecu-

act ,*'as applied when willful and reckless driv- tion proved two lg72 third offense willful anding (third offense) was charged. reckress driving con'ictions, (each using the

4. rhe possibre term or imprisonment ror the :i,ff::;:.fl'J[:::'i,#il;"i:XTH::Xjrl;

first offense of willful and reckless driving is a relied instead, how.ever, on proof of a lg6l

ntaximum of 30 days, u'hile the mayimum term state burglary conviction, a lg72 srate posses-

for a second offense is 60 days. Neb.Rev.Stat. sion of controlled substance con\ictron, and

SS 39-669'04-.05 (1974). Upon a third or sub- lg73 federal convictions for possession of and

sequent conviction, imprisonment in the Ne- receipt of a firearm in interstate commerce b1. abraska Penal and Correctional Complex for Dot convicted felon.

less than one year nor more than three vears is

mandatory' S 39669.06 (t974). Thus, al- 6. Goodloe also attacks the harsh sentence re-thouS'h the offense is unlabeled, the third con- sulting from applicarion of the habirual offend-viction became a felony by virtue of the Ne- er act under the Eighrh Amendment. \f,e agreebraska crimtnal code's general definition of fel- with the distrrct court that there is no merit roonl at the tlme of Goodloe's indictment and the claim. The severit!' of the sentence, argu-tria: "[t]he term felonl' signifies such an of. abll dispropon,rn",.

"nd

excessive for a traf-fense as mal be punished $rth death or inrpri,, fic offen-s, rras o,.henced br-:c.r. -.e of rer ptiti\c

( .rit,.\r ., .i.. \ .' ,Arl. r!. ..1 : ( . ,.t

n\

rr

l{

1

t

t I

r

-.

t'r

F

t r

r

b

b-

E

l

l\r

o tJ

r+

t

r

S

."

F

*i

is

af

+

f\'

['s

oc

uf

rlr

E

S

:;

F

t..

tq

I

r

\(

1n

.C

{6

-'}

r

}

9\

l?

t

5T

0

! r

IF

R

J

rl.

_c

,

tl

I

T

N

F

,A

*c

I-

;

Jw

F

-l

\q

r+

{

rii

r

k

f

\

J

$H

$

t-

\^

t

\r

d

Y

irf

lt

*

L,

-,

*

;

'

F

S

: I

,

D

*'

-q

i

f,

(n

s

+

V

1

IJ

\

oo

t6

-

\ \n (\

U

J

a

ir

crime of operating a motor vehicle to avoid

arrest as applied in his case.8 He makes the

same argument here. We need not pass on

the constitutionality of the statute, but re-

late the challenge to the statute only in a

collateral sense, as it affects the fairness of

Goodloe's conviction under it. See State v.

Etchison, 190 Neb. 6n, Ztt N.W.2d 405

(1973), cert. denied, 416 U.S. 949, 94 S.Ct.

1950, 40 L.Ed.2d 295 (t9?a); Heywood v.

,, , Brainard, 181 Neb. n4, 147 N.W.zd ??2

)Dtt1 (i96?). The statute's Iack of specificity in

t - definition of criminal conduct is reflected in

disputes which arose at trial over whether a

specific prior violation of la,*. had to be

alleged and proved for conviction. While

we hold Goodloe's trial was fundanrentally

unfair due to lack of fair and reasonable

S.Ct. 384, 24 L.Ed.Zd 248 (1969). Nor does rhe

unfettered discretion given the prosecutor un_

der the Nebraska statute render it unconstitu_

tional. Erowzr v. Parratt,560 F.2d 303 (gth Cir.

19?7).

7. We do not make the discretionarl.decision to

apply the concurrent sentence doctrine. Even

if we held the attack made on the willful and

reckless driving conviction failed to disclose a

constitutional infirmity., we could not say there

is no possibility' that adverse collateral conse-

quences w'ould flou' from the ar.oidance of ar-

rest conviction if it $.ere not rerie*,ed. United

srares v. BeIr, 516 F.2d 873, 876 (8rh cir. 1975),

cert. deuied,423 U.S. 1056, 96 S.Ct. ?90, 46

L.Ed.zd 646 (1976).

8. Neb.Rei .Sr"ar. S 60 430.07 ( 1974) reads as

follo'*'s:

Operating motor vehicle to avoid anest;

penalty. It shall be unlarvful for any person

operating any motor vehicle to flee in such

vehicle in an effort to avoid arrest for violat-

ing any la" of this state. Anv person violat_

ing the provisions of th:s section shall, upon

tors: the speciricity of the complaint and

arrest wamant'that alleged flight from ar-

rest for driving with a sg(pended license,

the general language E( tn" information,

the trial court rulingfon the elements of

the offense, the mid-trial switch in the pros-

ecution's case in chief, and the instructions

given.

It is clear from the arregt warrant and

the first information filed, statements made

in court and the progress of the trial, that

.the State based its avoidance of arrest

clarge under the statute on the theory that

the arresb Goodloe was avoiding was an

arrest based upon probable cause that he

was driving with a suspended license. Dur-

ing trial, the court ruled proof Goodloe had

violated a state Iaw was required for the

State to sustain its charge of avoiding ar-

rest. Thus, because Goodloe had been pre-

viously acquitted on the suspended license

charge, the district court ruled that proof of

flight from arrest for driving with a sus-

pended license was precluded and sustained

Goodloe's motion to exclude evidence con-

cerning suspension of his license.e There-

after the State, without amending the in-

formation, changed its theory of prosecu-

tion r0 and,attempted tg prove flisht from

^^m,,[nrhe, gJ

"ity.,fr#a,

ga

sum not exceeding five hundred dollars, (2) V

imprisoned in the county jail for not to ex-

ceed six months, (3) imprisoned in the Ne-

braska Penal and Correctional Complex for a

period not less than one ),ear nor more than

three years, or (4) punished by both such fine

and imprisonment. The court shall, as a part

of the judgment of conliction, order such

person not to operate any motor vehicle for

any purpose for a period of one year from the

date of his release from imprisonment, or in

the case of a fine only, for a period of one

year from the date of satisfaction of the fine.

9. The correctness of the state district court,s

ruling is not before us. Even if the State were

not able to produce competent evidence to

prove that Goodlo,, was driving with a sus-

pended license, the record indicates the offrcer

had a good faith suspicion and could have

stopped him for questioning.

10. In the habeas proceeding in the federal dis,

trict court, Judge Denney found this to be the

case, observing in tris opinion:

Referring to the language of the arrest w,ar_

rant, Coodloe established the undispute(l tJct

them willful and reckless drr r ir€

court allowed the switch, but tr 'ru, of its

concern over'!bg-issu9--Olja*--+otice to

(!qqdlA:6-rjhq q!g--be had :o meet, it

.p""ifl"a tiru ,rna"-".b'ing viola: ron and in-

structed the jury that it must find, as an

element of the offense of operating a motor

vehicle to avoid arrest, that Goodloe "had

violated a Iaw of this State, to-wit: Operat-

ing a motor vehicle in such a manner as to

indicate a willful disregard for the safety of

persons or propert)' ." ll

The fundamental right "to be informed

of the nature and cause of the accusation,"

guaranteed criminal defendants by both the

Nebraska and United States Constitutions,

U.S.Const. Amend. VI; Neb.Const. art. 1,

$ 11, is implemented primarily by charging

7' papers which contain the elements of the

/ off.ense so as to fairly inform a defendant

of the charge against which he must de-

fend. Hamling v. United States, 418 U.S.

87, 117, 94 S.Ct. 2887, 4r L.Ed.2d 590 (1974);

United States v. Brown, 540 F.2d 364, 3?1

(8th Cir. 1976); State v. Harig,192 Neb. 49,

56-57, 218 N.W.zd 884, 889 (1974). This

most basic ingredient of due process, a per-

son's right to reasonable notice of the

charge against him, is incorporated in the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution and thus cannot be

abridged by the states. See fn re Oliver,

333 U.S. 257, ffi S.Ct. 499, 92 L.Ed. 682

(19a8); Cole v. Arkansas,333 U.S. 196, 68

S.Ct. 514, 92 L.Ed. 6a4 (19a8); DeJonge v.

Oregon,299 U.S. 353, 362, 57 S.Ct. j55, 81

& Uu{ar-vf,s\*)

that the pros6cutlon originally intended to

prove that the preexisting violation of law

was the misdemeanor of driving on a sus-

pended license.

The reversal of the county court's decision

foreclosed the State from pursuing this theo-

ry. Forced to adopt another tack, the prose'

cution asserted that the defendant could be

found guiltl'of fleeing to avoid arrest for the

offense of u'rllful reckless driving.

ll. The rnstruction, at least insofar as it stated

that the jury must find Goodloe had violated a

law of the state and r,r'as fleeing in an effort to

avoid arrest for that violation, was upheld b1'

the Nebraska Supreme Court as a correct state-

ment of the law. State v. Goodloe, 197 Neb.

632. 637, 250 N W.2d 606. 6t0 (1977).

330, 3ll8 (6th Cir. 19, i,l.tz

.An information in the words of the stat-

ute creating the offense will generally suf-

fice, Hamling v. United States,418 U.S. at

117, 94 S.Ct. 2887, but the requirement of

fair notice is only met if "those words of

themselves fully, directly, and expressly,

without any uncertainty or ambiguity, set

forth all the elements necessary to consti-

tute the oflence interrded-to-be- punished."

Id. (quoting United States r'. Carll, l0it

U.S. 611, 6L2,26 L.Ed. 1135 (1882)t; see a/so

State v. Abraham,l89 Neb. 7L8,7n40,205

N.W.zd 342,343-4 (1973).

,

The indictment upon which Goodloe u'as

tried charged that hc did, in the words of

"the statute, "unlawfully operate a motor

vehicle to flee in such vehicle in an effort to

avoid arrest for violating any law of this

State." There is no indication from this

statutory language that, as the trial court

held and instructed the jury, an additional

element must be proven for conviction: ac-

tual commission of the violation of state

law for which the arrest.

at-

titled not onl

quire states to observe Fifth Amendment provi-

sions regarding indictment, it does guaratrtee

state prisoners a fair trial. Nexander v. Loui.

srarra, 405 L.i.S. 625. 633, 92 S.Ct. 1221. 3

L.Ed.2d 536 (1972). Sufficiencl of ar] rndrct-

ment or information is primarily a question of

state la\r', but liolations of due process arising

from lack of fair and reascnable notlce are

cognizatrle in habeas corpus. See, e. I, Rjdge

w'ay v. Hutto, 474 F.zd 22 (8th Ctr. 1973):

Blake v. Morford,563 F.2d 248 (6th Cir. 1977),

cert. denied. 43{ U:S. 1038, 98 S Ct. 7?5, 54

L.Ed.2d 787 (1978).

254, 43 L.Ed. 505 (1899); United States r'.

Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 5.{2. 56ffi6. 23 L.Eds8tt

d-ikT,J<-r -I u<cfuu-t ^- r/12. While the Due Process'Clause does not,te-

8J

\,o

t/"

b,-",.t

oIa

o

to notice of that general

of ['hat law

-sg

dP

{ F

*

*$fi$

B

1 3l$

-iS

s_st{

{i l'l'

ftl+

Il$

{-t

j

?J

-\t=

5JJ

,v,f

\5{<I\):

{nH

\

=

1 =5?

{;$}}t{

t' s+

S

iE

l

$ fi$ 3f, =

E

dr::Ir-3

i:jlpi''q

I?ri{i}/ t*f

(Jcl-

@

'->

I lE

S

*R

,fr$$*ti Is

]B

G

i}T

ti;:$i+

}l Y

IT

i

{i}{s i J{fi ! tI

,

{+

I iR

-\ {r1; {i

,*IJJl

-t

=

J\

a-\Z

\5\<3\-a

5\i\t(

Y

.L

Ji-

cs-+

\3J

Tr>;c

{rT

f,J

lo( 6

L

..-.r._;^-_._.

i.:,i .,vv,!! uJ rtrrurrilallull was agg.ra!a_license charge iilustrated, whether i*atou td rv uncertai4ty during trial over whathad.violated a specifie state statute was a {eciric ,i"r"a,r"r'the prosecution wourdcrucial factuar determination. In such " /iou". ti"--i*r" urged, as rate as thesituation' an information which describes conference on instructions, that the jurythe offense in generic terms fails to ade- could find from its proof that the underly-quately inform of the specific offense ing violation wa. eithe" failing to stop at acharged so as to arow preparation of a stop sign, speeding, careless driving or wilr_defense. Russe/1 v. ILnited states, 869 u.s. ful anJ .""kro., i"irrrg, even though the749, ?u-66, g2 S.Ct. 103g, g L.Ed.zd. 240 first three violations were never mentioned(1962); united sfates v--r{ess, r24 U.S.4gB, in a compraint, arrest warrant, or informa-487, 8 s.ct. bzr, 81 L.Ed. b16 (1gs8). Thus tion. Thus, in mid-rriar the State not onrythe information, while couched in the lan_ changed tt" unau.ty:lrg violation it soughtguage of the statute, nev_ertheless failed to to prove, Dgl-j,hen_&iled_tLsg:_qify -Iuhatadequatell'describe the oifense charged be__ ,;nl"tion i'fils attqBptfug to prove. Thecause it did not allege an essential .uu.tun--I.i"t

"ii"t-iFffi the problem of fairtive element. see u1iled states v. caril, notice to Goodli and onry alrowed the jury105 u's' 611' 612' 26 L'Ed' 1185 (1gg2); see to find willful ancr reckless driving as thealso Dutiel v. State, 185 Neb. g11,2g4 N.w. necessary prior violation element of the321 (1939). voidance oi arrest charge. f!:_491[qctionIf a defendant is actuallv notifio.r ^r th" to the jury could not, hoo.""Jfirre thec"ntsfundamentaIunfairnessofreqrriringGood.

?y be met- even if the ation is loe to defend {iifiurt notice oi .p"jri"

"r"-= See United Stut"t iVli{st1 . ments of rhe oifense_ sL^_rcgq.

'- -'-

--T.2d 737,740 (8th cir. 19?6); cf. inited The mid-trial shift, from proof of flightstates v' cartano,5g4 F.2d ?gs, ?g1 (gth to avoid arrest for driving with a suspendedcir')' cert. denied,42g u.s. g4g,9? s.ct. izr, ricense, for which Goodroe had prepared a50 L'Ed'2d 113 (19?6). Goodloe was noti- defense, to proof of flight to avoid arrestfied by complaint and arrest warrant of the for any one of four possible violations, illus-prosecution's theory that he fled arrest for trates the prejudice inherent in an informa-driving with a suspended license. He was tion which fails to specify an essential ele-prepared to defend on those grounris and ment of the offense. The defendant is giv_therefore would not necessarily have been en insufficient notice to prepare a defense,prejudiced if the trial court ruling had been he proceeds to trial with factual issues un-lim.ited to requiring commission of the uio- defined, and the prosecution is left,,free tolation for which his arrest u'as sought, driv- roam at rarge-to shift its theory of crimi-ing with a suspended license, be ploven as nalitl.so as io take advantage of each pass-an essential element of the charge.ll ing vicissitude of the trial and appeal.,,' However, even assuming Goodloe was not Eusse/I v. IJnited states, s6g u.s. at ?6g, g2

prejudiced by the information's lack of no_ S.Ct. at 1049.

absent element, of which Goodlot did have

notice, was changed by events at trial, ef-

fectively amending the already deficient in-

formation or creating a variance; and, be-

cause the State did not specify the element

it sought to prove until the end of trial,

Goodloe had to prepare to meet, or without

notice was unable to meet, proof of four

possible statutory violations. Under these

circumstances, we conclude Goodloe was not

given fair and reasonable notice of the of-

fense charged and the case against which

he had to prepare a defense; the result was

a fundamentally unfair trial that requires

the conviction be set aside. See Watson v.

Jago, 558 F.2d 330 (6th Cir. 1977).t5

t4l Willful and Reckless Driving. Re-

maining is Goodloe's attack on double en-

hancement of his penalty for willful and

reckless driving-punishment as a felony

upon finding the conviction was for a third

or subsequent offense follorved by imposi-

tion of the mandatory 10 year minimum

sentence under the habitual criminal stat-

ute upon proof of two prior felonies.ls

A statute that enhances punishment on

the basis of subsequent convictions fr.rr the

identical offense and an habitual criminal

statute, which enhances the penalty on the

basis of any prior felony convictions, have

been repeatedly upheld against almost ev-

ery conceivable constitutional challenge, in-

cluding due process, douhle jeopardy, and

cruel and unusual punishment. See Spen-

cer v. Texas,385 U.S. 554, 559-60, 87 S.Ct.

fJ 8ao,*/1"kf.*.ts5,"1"o ?1$JJ o,

presenting the substance of his claim to the

Nebraska courts. He brought to the attention

of the trial court, through a motion to dismiss

for insufficient evidence and objections to in-

structicns, prrblerns in definition of the ele-

ments of the offense and the resultant lack of

notice of what underlying l'iolation the State

had sought to prove. Fundamental unfairness,

due to confusion as to lhe elements of the

crime and lack of notice. was raised in a due

process attack on the vague language of the

statute in briefs in both the Nebraska Supreme

Court and this court.

16. \l'e hold the evidence was suftrcient to sup-

port the conviction of willfirl and reckless dnr.

ing. r*'e have revieu'ed the evidence under the

standard set forth in Jack.snrr v. Virginia.

Bennett, 410 l 2d Zltx, Ni (8th Oir. lgt'e).

The reasoning is that the statutes do not

charge a separate and distinct crime so as

to put a defendant again in jeopardy for

the prior offenses, but bear only on permis-

sible punishment for the latest offense.

Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448, 82 S.Ct. 501, 7

L.Ed.% ,U6 (1962); Gryger v. Burke, 3U

u.s. 728, 68 S.Ct. t?56,92 L.Ed. 1683 (19a8);

Graham v. West Virginia, 224 U.S. 616, 32

S.Ct. 583, 56 L.Ed. 91? (f912). Nor is penal-

ty enhancement considered multiple punish-

ment for one offense, but rather,impxrsition

of a heavier punishment for dn offense

aggravated by repetitious criminal conduct.

Gryger v. Burke; Graham v. West Virginia.

Nonetheless, we have been unable to find

any federal cases which consider challenges

under the United States Constitution to

stacking a specific subsequent offense pen-

alty enhancement statute and a general ha-

bitual criminal statute upon one another in

sentencing for a single offense.

Several state court decisions have in-

volved use of a statute ,that enhances :r

misdemeanor to a felony upon repetition of

the same offense and a general habitual

criminal statute. Very few of these cases

address the instant situation, however, in

which the conduct being currently punished,

the offense which "triggers" application of

the habitual criminal statute, is a misde-

meanor that has been enhahced to felony

status only by virtue of its repetition.lT

U.S. --, 99 S.Cr. 2781, 6l L.Ed.2d 560 (1979),

decided subsequent to the federal district

court's opinion.

17. Some cases decide *'hether an "enhanced

misdemeanor" is a felony to be used as a prior

fe,lony conviction to enhance the penaltl' for a

current charge under an habitual criminal stat-

ute. Although it is stated as a general rule that

offenses *'hich are felonres only when those

'*'ho perpetrate them have been prer.iousll,con-

victed of crimes do not constitute "felonies"

within the meaning of prior felonies that en-

hance penalties under habitual criminal stat-

utes, annot., l9 A.L.R.2d 227,232 (1951). state

courts are evenly divrded. Prohibiting use of

enhanced misd"meanors as prior "felonres"

S.E. 874 (1895): Srare v. Bro*'n,9i W.Va. 187.

tice of an esscntial element of the offense, Due to a unique combination of circurn_

3: j*'::.1 :j,lI.,,l.rmatior. rvas com_ rtrn"".,-ir,u i;il ;;;;ff;,". #:il;

notice or amendnrent of the information, in the inf-ormation ,ror-lri:i;,;r:;rir;i::::l

I3. The trial judse realized rhis rrcrioienr., .,.h-- t' ,3:t L+ . "1

; ;:r)ff;*0";;)r^fi'';,JH :'J " ii:':: J:r,Y,:i :'' : ::'' ::

=.*

I:I Ii:,fri:ilfr J;#ffi#,d

:::',:lH, :?".,'1.:',T-"::r,i:.. iil :g::;g ,r: ;, ;;;.;;,';;.';;*,#iJil::Ji: i'j'83:::

::::::,,f: Ti,::,,::"..l:llre_the s_tate shourd r*, in"..,";.;,ffi;,;il;.;ffi,:"il:.i"T:;set out the particular violations underlS,ing the not been stopped and the driver has not been

inforrned he is subject to arrest, proof of a

r i.

ll-2;

marn offense

f\q eter"^e^r-]-s .{tp "($r4< -na ::,:,:..";}:,,,:iJ:.". "",""iil,1"1""I1 i

lo<.1< 6-(

case of flight in an attempt to avoid arrest

I

t

l'

GruJtOe e krov*rn, u^r-,,{ia {r',.^re^ *l <-,n--.tJ ("t*U Sef^h./ WtL^."[L \-*." o 5*!pt,.^-l"c.l (rtezrrse )fu W y c-l,.$rtg

A G,c< z.Q-o-1-i'o.o

r) E.t \^,c-,4 *+# il i,\ u\e. C6L*-.f - l/v t+,1

w/ t-Ja{}*^d lsa*''a-o'@'^ 44 oped-,

,nn.rT,ot.rrr, t o^ t*,

^-A

-'- \ - oc.3 t ., Fto-/ (u' ,r""1[yrrutU'l+

)v of{r r-0 c^1La )

-co.r,.^;t 1L+ b aa,) <.(ea-.,*k" a bvq bo.r1 4"1

(rr- ^r-u&/r, 6,-v4* (* drvr^f witL a luspe,xle<l, ^],r.sen<.eG*t toov{) 4ftr,€ ,*/ &$[m^-^n frffi'C,*?prlu)

%stde^e1 Ltuo ir*l of r1,".,,, 17 N sto/e vritu, L, ,ot-il

*^rtC * )

- cr^ce, +1*/^*trr.,-,-tw,^ l^rrr*.o+) .) s+de .*M u, l^tf

fl^.",/ ..,-^.4a^^-rT (u".- al,,^^\ t^r,t\ t* lil ,;'r-.) r lO

r1- (<^-r ctc LJ L ,\t-^.ot.*T o-ruJ (ox .tt ^ 'l L"*, t u - &-(kZ

Lr-^,t rU1

useri in the general deseription of an him, ." United States v Sim-

mons, supra (96 US at 862). A. oflence it must be accompanied

such a statement of the facts ptic form of indictment in cases

circumstances as will inform the f this kind requires the defendant

go to trial with the chief issue

ption, ndefined. It enables his conviction

rest on one point and the affirm-

Sta 493, 497,31

meandering .tot"*Jit.u'o;;;;"; "" ' .r.j6e us ?esl

to iclentify the subject under inquiry. He *r,r'as not told at the time what

It was said that the hearilgs wele subject the subcommittee was in-.,not . an attack upo, the vestigating. The prior record of the

free press," that the investigatiol subcommittee hearings, rvith which

*r. of "such attempt as may be dis- Price may or may not have been

closed on the part of the Communist familiar, gave a completely confused

Pat.ty to influence or to sub- and inconsistent accottnt of rvhat, if

velt the American press." It rvas anythillg, that subject lvas. Price

also said that "We are simply inyes- was pttt to trial and convictetl upon

tigatipg commlnism whereyer we all indictment 'which did not even

finrl it." In clealing with a witness purport to inform hini in an1'way of

rvho testified sholtly before Price, the identity of the topic under sttb-

co*,sel for the subcommittee em- committee inquiry. At every stage

L-N

8 S Ct 571. See also

Pettibone v United States, 149 US

197,202-204,87 L ed 419, 4ZZ,4ZB,

13 S Ct 542; Btitz v United States,

153 US 308, 31b, 38 L ed 725,727,

14 S Ct 924; Kecli v Unitecl States,

172 US 434,487,43 L ed bOb, b07,

19 S Ct 254; I\{orissette v Unitecl

States, :1.12 US 246, 270, note 80,

96 L ed 2S8, B0l, 72 S Ct Z4O. Cf.

+ l.a(! United States v Petrillo, BB2 US 1,

n",l-E^ 10, 11,12 91 L ed 18?2, 1884, 1985,

U* ' 67-S Ct 1538. That these basic

prfto,*'7"'Ur- princinles of frnrrl:.men-

ern concepts of pleacling, and spe-

cifically nndcr Rule T(c) of the Fed-

eral Rules of Criminal procedure,

is illustrated by many recent fecleral

decisions.13

The vice which inheres in the fail_

ure of an inclictntent urlder Z USC

$ 192 to iclentify the subject uncler

inquiry is thus the violation of the

basic principle ,'that the accuserl

must be apprised by the inrlictnient,

rvith rcasonable certairrty, of the

nature of the accusation against

ance of tXe conviction to rest on

another. (lt gives the prosecution

free hand-bn appeal to fill in the

gaps of proof b1- surmise or conjec-

ture. The Court has hacl occasiorr

before now to condemn just such a

practice in a quite different factual

settifi!1 Cole v Arkansas, B3B US

79G,291,202,92 L ed 61.i, 647, 648,

68 S Ct 514. And the unfairness and

uncertaiuty rvhich have chnracteris-

ticallv infected criminal proceedings

under this statute l.hich rvere based

upon indictments rvhich failed to

specifl. the subject uncler inquir.y

are illustrated by the cases in this

Court u'e have alreacly discussecl.

The same uncertainty ancl unfair-

ness are unclerscored by the records

of the cases now before us. A single

example rvill sufljce to illustrate the

point.

In No. 12, Price v Unitetl States,

the petitioner refused to ansryer a

nurnbel of questions put to him b1,

* [.']69 L:S 7671

the Internal +security Subcomnrittee

of the Seuate Judiciar5' Comntittce.

At the begiruting of the hearing in

question, the Chlrirman and othcr

subconrmittee members made rviclely

^

(, t- I ;ubconrmittee's purpose "to investi- Price was nlet lvith a different

v, II gate Conlmunist infiltration of the !I"o.y-q!r no theorl' at ,!]l=as

phaticalll, denied that it \virs the in .the ensuing criminal proceedi4g

prcss anti other folms of communi- (to what the-tbBle-hcrdt-€6fi. Firr

catigp." But when Plice g,as callecl I from infot'ming Price of the nature

to testify before the subconrnrittee ( of the accttsltion q€3lL1s!-bjn tfre

no one offered eyen to attempt to/ itndictment instead left the DroS€cu:

lnlol'm Illm or \4'niIL suoJecL [Ile suu-l tr r

committee dicl have untler inquity.[ its theor."- of climinalitl' so as to

At the trial the Government tookl take advantage of each passing

12. Rosen v Unitcd States, 161 US 29,

40 L ed 606, 16 S Ct 43,I,480. ireavilv relied

upon ri.r the clissenting opinion, is inappo-site. In that case the Court held thai^an

indictmcnt charging the mailing of obscene

material did not need to spccify the par_

ticular yrortions of the prLli""iior, .,i.,i.h

rvere allegedly obscenc. As pointcd out in

tsartell v United States, 22T US 42i, 4Bt,

!7. ! $ 583, 585, 33 S Ct BS:t, thc .uiu orj

tablislrcd in Rosen rvas ahvrivs r.cgar.rle<t

as-a "u'ell r.ccognizcd exrcl)tion', to usual

in,lictrnorrt rules, applit,lrl,lt, o,,," t" ..ti;;

I'ir.edirrrl of Ir.iut<.tl <rr rvr.itt,.tr nratt.,r

nhich is allcgctl to bc too obsccrr,r <rr in-

decent to be spread upon the recor.ds of

the court." flnder Iloih v Unit, tl States,

q9l_US 4?6, 488, 489, 1 L ed 2cl 1t{rS, 1509,

77 S Ct 1304, the issue dealt rvith in Roseri

would presunrably no longer arise.

13. United States v Lamont (CA2 Ny)

236 P2d 312; ltleer v United States (CA10

Colu) 235 F2d 65; Bahh v liniie,d Stntos

( CAS Tes ) 2 I S F2d-fflT;llofrt,,t-;-,

Fn-ffitllid-ilE'D- rsz n Supp ?:r1;

Unitcd Statcs v Devine's I\Iilk Labora

^oories, Inc. (DC llla.s) 179 F Srrlrp ?{}1,:

U_1ited States v Ape-x DistlibuLing Co.

(DC ill) 1-18 I' Supp 3rj5.

the position that the subjcct under\icissitude of the trial and appeal.

inquiry had been Communist aciivi- i-inquiry had been Communist activi-

ties generally. The district iuqs! nal offense unless the questions lhe

before whom the case was tried refusecl to ansrver. rvere ii fact perti-

founcl that "the questi<-rns ptlt \\'ere nent to a specific toltic untler sub-

pertinent to the matter utlder in- c.mmittee inorrirv at the time he

,! , * [Lii;:r'i;,*#':,iii:;[,1*"*iT, il" c,mmittee inquirv at the time he

'yfu l*.':t,:tix$ilf^H[x;irx ss:ii;%t ']i'i;;,iYt':!

,,, f e/ b,A firming the conviction, likervise \

-trj\ I trt , omitted to state rvhat it thought the It has long been recognized that

i u q{ +U _ subject ttncler inquiry had been. In there is an irnportant cor.ollar."- pur-

'_ir'-.- , OP this Corrrt the Governmettt colttends pose to be sen-ecl by the requirenient

S'2fl1 t"-' - that the subject ttttder inquiry. at ihot r., inclictrnent set out..the spe-

y :.H* ili:}iil".1!".%i*iL',iJx'.illli,1

n

;ii! ;fftffi,ii}1inilii',il,lH"";:

:' ,)r-r: 'crlD rrrsur(" fendant is charged. Tltis pttrpose,

lx.t-*'":e, It is rlilficult to imagine a case in as defined in Unitecl

Lottn F"' ' u'hich an indictnrent's insufficiency Headnote l{ States v Cruikshank, 92

T- ; fu!,-1 resultecl so clearly in the inclici- US 542, 558, 23 L ecl 588,

.lL. k'1, -t ztrr - melt,s failur.e to fulfill its plimary 5C3, is "to inform the court of the

rl,voo Po-' -"-!n oflice-to inform the defenclant of facts alleged, so thrrt it ma1' clecide

a--'- Y'- the nature of the accusation against whether thel'are sufficient in larv to

ao /: t,'x - t 4 him. Price refused to ansq'er some support a conviction, if one should

-Ld,()* questions of a Senate sul;conrmitl.ee. be harl."rs This criterion is oI the

$_f rry w -l I5. This principlc en rrtci:rtcd in Cruik- sevct:rl l'oc(nt cascs attcst. "Arother rer-

t-tJ )14.4 ,tt*-r*@'tt- t'-il,, A +,,t c.tt^t t,4-*<o-d-€oy4 a-'"-Tto" ./fu,ti

H.,^n<-ro.t

r.rri, u s ;uyr. gleatest relevance *here, in the light

. of the difficulties and uncertainties

with which the federal trial and re-

1 viewing courts have had to deal int cases arising under 2 USC g 192, to

which reference has already been

r made. See, e. g., Watkins v United

States, 354 US 178, 1 L ed 2d 1273,

77 S Ct 1173; Deutch v United

States, 367 US 456, 6 L ed 2d 963,

81 S Ct 1587. Viewed in this con-

text, the rule is designed uot alone

for the protection of the defendant,

but for the benefit of the prosecutiorr

as well, by making it possible for

courts called upon to pass on the

validity of convictions under the

statute to bring an enlightened judg-

ment to that task. Cf. Watkins v

United States (US) supra.

It is argued that any deficiency in

the indictments in these qrses could

have been cured by bills of particu-

*[369 US 770]

Iars.* But it is a set-

Eeailnote 15 tled rule that a bill of

particulars cannot save

an invalid indictment. See United

blaLcs v r\r.1.'rrs, zo1 trS blg, 6Z2,

74 L ed 1076, L077,50 S Ct 424;

United States v Lattimore, 94 App

DC 268, 275FZd 847; Babb v United

States (CA5 Tex) 218 F2d EB8;

Steiner v United States (CA9 Cal)

229 FZd 745; United States v Dier-

ker (DC Pa) 164 F Supp 304; 4

Anderson, Wharton's Criminal Law

and Procedure, g 1870. When Con-

gress provided that no one could be

prosecuted under 2 USC g 192 ex-

cept upon an indictment, Congress

made the basic decision that only a

grand jury could determine whether

a person should be held to ansrver

in a criminal trial for refusing to

give testimony peltiirent to a ques-

tion under congressional committee

inquiry. A grancl jurl', in orcler to

make that ultimate detelmination,

must necessarill' determine r,iJrat the

question uncler inquiry rras. {ho al-

lorv the prosecutor, or the court, to

make a subsequent guess as to what

was in the mincls of the grand jury

at the time they returned the indict-

\rt

@.1! and accurately alleged-ii-lb

d i c tm en-Flia'nd-ffiffi i i rniFv c r l o o k e d,

iftO--Cffite the court to decidc rvhethcr

cuse L Rev 389, 392. See also Orfield,

Crirninal Procedure fronr Arrest to Appcal,

226-230.

16. In No. 128, Gojack v United States,

the petitioner filed a timely motion for a

bill of particulars, r'equesting that he be

informed of the question undcr subcom-

nrittee inquiry. The motion rvas denied.

In No. 9, Shelton v United States, the

petitioner filed a similar motion. The mo-

tion rvas granted, and the Covernt.uent re-

sponded orally as follorvs:

"As to the second asking, the Govern-

ment contends, and the indictnrent states,

that the inquiry being conducted rvas pur-

suant to this resolution. \Ye do not Ieel,

and it is not the case, that there rvas any

smaller, more limited inquiry being con-

ducted.

"This conrmittee was conducting the in-

quiry for the purposes containcd in the

rcsolution and no lesser purpose so that,

in that sense, the asking No. 2 of counsel

u'ill be supplied by his reading the resolu-

tion."

In the four other cases no motions for

bills of particulars lvere filed.

the facts alleged are snflicient in larv to

withstand a motion to disnriss the indict-

ment or to support a conviction in the

event that one should be had." United

States v Lamont (DC NY) 18 FRD 27, 31.

"Ir: addition to informing the defendant,

another purpose served by the indictment

is to inform the trial judge u'hat the case

involves, so that, as he presides and is

called upon to make rulings of all sorts,

he may be able to do so intelligently."

Puttkammer, Adnrinistration of Criminal

Law, L25-126. See Flying Eagle Publica-

tions, Inc. v United States (CA1 NH) 273

F2d,?99; United States v Goldberg (CA8

Minn) 225 F2d 180; United States v Sil-

verman (DC Conn) 129 F Supp 496; Unit-

ed Statcs v Richman (DC Conn) 190 F

Supp 889; United States v Callanan (DC

I\{o) 113 F Supp ?66. See 4 Anderson,

Wharton's Criminal Law and Procedure,

506; Orfield, Indictment and Infornration

in Federal Criminal Procedure, 13 Syra-

son [for the requirement that every in-

.t

t

ment would deprive the defendar '

of I basic protection which the

guaranty of the intervention of a

grand jury was designed to secure.

For a defendant could then be con-

victed on the basis of facts not found

by, and perhaps not even presented

to, the grand jury rvhich indicted

him. See Orfield, Criminal Proce-

dure from Arrest to Appeal, 243.

This underlying principle is re-

flected by the settled rule in the fed-

eral courts that an in-

Headnote lG dictment may not be

amended except by re-

submission to the gral'rd jury, unless

the change is merely a matter of

form. Ex parte Bain, 121 US 1, 30

L ed 849, 7 S Ct 781; Unitcd States

v Norris, 281 US 679,74 L ecl 1076,

50 S Ct 424; Stirone v Unitcd States,

361 US 2\2, 4 L ed 2d 252, 80 S Ct

270. "If it lies rvithin the province

of a court to change the charging

part of an indictment to suit its ou'n

notions of what it ought to have

been, or what the grand jury rvould

probably have macle it if their atten-

tion hacl been called to suggested

changes, the great importance rvhich

+t369 US 77tl

the common lalv attaches to *an in-

dictrnent by a grancl jurl', as a pre-

requisite to a prisoner's trial for a

crime, and rvithout which the Con-

stitution says 'no person shall be

irerd to answer,' may be frittered

away until its value is almost de-

stroyed. . Any other doctrine

would place the rights of the eitizen,

which were intended to be protected

by the constitutional provision, at

the mercy or control of the court or

prosecuting attorney; for, if it be

once held that changes can be made

by the consent or the order of the

court in the body of the indictment

as plesented b1'the grand jury, and

the prisoner catl be called uilon to

ansryer to the indictment as thus

changed, the restriction l,hich the

Constitution places upon the power

of the court, in regard to the pre-

requisite of an indictnrent, in reality

no longer exists." Ex parte Bain,

supra (121 US at 10, 13). \\re re-

alErmecl this rule onl)' recently,

pointing out that "The verl' prlr.pose

of the requiremeut that a man be

inrlicterl by grand jury is to limit his

jeopardy to offenses chat'ged by a

group of his fellorv citizens acting

independentll- of either prosecuti4g

attorney or judge." Stirone 'v

United States, supra (361 US at

218;.rz

For these reasons lve conchrde

that an inclictment under 2 USC

$ 192 must state the question under

congressional committee inquiry as

rt369 US 7721

found by the grand jur]-.* Only

17. Sce also Smith v United States, 360

US 1,13,3 L ed 2d 1011,1050,79 S Ct 991

(dissenting opinion); Cornment, 35 l\Iich L

Rev 456.

18. The federal perjury statute, 18 USC

S 1621, makcs it a crinre for a person undcr

oath willfully to state or subscribe to "any

material matter rvhich he does not believe

to be true," The Governmcnt, pointing to

the analogy bctrvecn the perjury nraterial-

ity requiremcnt and the pertincncy rc-

quircnrcnt in 2 USC $ 1C2 recoguized in

Sinclair v United States, 279 US 263, 298,

7ll L ed 692, 699, 49 S Ct 268, contends that

the present cases are controllcd by I\Iark-

harn v tinitcd States, 160 lls :119, 40 L ed

441, 1G S Ct 28S, s lrere t;hc Court sns-

taincd a perjury indictnrcnt. But llrrrk-

hatn is inapposite. Thc analogy betrveen

the pcrjury statute and 2 USC g 192, rvhile

persuasive for some purpos?s, is not per-

suasive here, for the determination of the

subject under inquiry does not play the

central rolc in a perjury prosecution rvhich

it plays under 2 USC S 192. But even

rvere the analogy perfect 1\Iarkham rvould

still not control, for it holds only that a

perjury indictment nce<l not set for.th horv

arrd rvhy the statements rvere allegedly

nratelial. The Court careiully pointed out

that the indictnrent did in fact reveal the

subject under inquily, stating that "as

[the fourth count of indictment] charged

that such statenrent s'as matelial to an

inquiry pending befole, and rvithin the ju-

risdiction of, the Cornmissioner of Pen-

.-r l_rer.soll calllo[ torrense("t;";;;;;""i"=-,li,floll

t{ilf-i:;fl:,rt",,HffHlT:,-i,T

i

offense) not charged a_gainsr

11,n

Lr:'l"l irl . o**ii;;;;;;.rr against doubtedictmenr or information, wherher oi not j"-"arl* Ca,ey;.-;;;;.*rr,sl9 F.zd 184,there was evidence

"t rt, ,i"i-i"-rn"* Lu Orn Cir. t9?5); IJtfrthathehadcommittedthat"rr"*"....'.;;,.*^.zas8;.,;'m.

The information charging fr""iUI".rp" infilo."ou"r, the Sul,rcme Court has held oth_the present case did not advise p"tiuon"" J".o,r" p.o.o.r;;,.';;",ated with a fairthat he must be prepared to ront"o'""i t"i"r,"'n"." r^i.'ii",iir"," infraction canevrden@ that his alleged victim was un- il:: F rreated u.iu'.riu.,

"".o". Gideoncrer the age of 2l years.and to defenJ a ,. 1r.r.i*"irt,il;:i.,;r5,88 S.Ct. ?92,9il"11:;lJt":,:".:mitted ., * ;"; i.e9 r,a d&;)i;iiio .o,,,"r) ; payne

,

rd. at 173,288 p.2d at ? (citations omitted). iT^r"f{ i;;;i,r,i;i.ll 1H:i. ?'# 0t3l what makes statutorv and forcibre 11 sro*r" -dr;;"i."*rage

in core and,rape separate offenses ro. .trurging pu.l oriu.er, supra, indicating that the right to I

poses is ths fact that proor or"air-rele]rt notice of " "r,".*" I basic and the most

:i#:fJ [:i,;:]"lnl ,'"

"r

r**,..1, crearry *,"rri.r,"i"auu 0.o.",, righr or an

"r,r,",iJ*'#:il:J111;.ffiT:;::

accused in a criminar proceeding,-!.h-e.o,- +-trfrl 1r,\

Tp". Neither element is common t;;;;;degrees Because,,"iil$ifll{{"ry; ;@;;ffi,* )p1o/ .

o

rapearedistinct"-j.i::"i:.:::,ffT,,il:m,."o'o,".",gtt

sree rape is not an incrudecr orr"n.", ** .r.ilor;; ;;;;;; JJr.,"ffii:",i.Tiiiil;ilstate was obrigated to comprl' with the sensitivitl' tt ut -u]t ue protected. TheH'IffXlT."J.il:*:"::::;*";;;h* Supreme courr has herd that i

Cite as 662 F2<l 569 (l9r I )

transmute the test to a subjective that principle of due process. Gray,s entire

issue of the respondent's understanding nse to the forcible rape charge was that

lr: of a defective charge would place the

. constitutional purpose in danger. Au-

thoritarian caprice, against which the

whole structure of constitutional law was

erected as a barrier, could begin again to

outflank our objectives of justice and fair

, tzt yt. 387,205 A.zd

407, 409 (1964).t

ln l|'atson v. Jago,558 F.Zd BB0 (6th Cir.

19?7), the Sixth Circuit, in finding that the

state trial court had violated the Si.xth

Amendment right to notice, held:

To allow the prosecution to amend the

indictment at trial so as to enable the

prosecution to seek a conviction on a

charge not brought by the grand jury

unquestionably constituted a denial of

flue process by not giving appellant fair

notice of criminallharges to be brought

against him . .f It a matter of law,

llant w-as prejudiced by the construc-

tive amendment.

sexual relations were consensual. This

'ense gained Gray an acquittal on the

ible rape charge, but as was pointed out

the dissent to the Arizona Supreme

rt's opinion affirming Gray's statutory

conviction,

different defenses are involved, and a

defendant may virtually conr-ict himself

of statutory rapr if he is surpristrl h1 a

statutory rape instruction after present-

ing a consent defense to a forcible rape

charge.

State v. Gray, 122 Ariz. at 450, S9b p.2d at

995 (Justice Grirdon, dissenting). This is

precisely what occurred here. The state

was permitted to wait until Gra1, had put

on evidence of consent as a defense to the

charged offense, and then use that evidence

to convict Gra.r- of the secontl offense. Such

a procedure is repugnant to the concept of

due process and fundamental fairness.2

For these reasons, a reversal is rcquired

based solell' on the inadequaby of the charg-

ing information.

t5] Even if the defendant's actual

knowledge of the victim's age is considered,

the conviction still must be overturned.

sent, did not seem quite certain of its relevance,

for the opinion went on to state:

The lack of pretrial notice dy information

was aggravated b1- uncertainty during trial

over u'hat specific l,iolation the prosecution

would prove. The State urged, as late as the

conference on instructions, that the jury

could find from its proof that the underlying

violation was [any of the four separate

crimes] even though the first three r,l,ere nev-

er mentioned in a cotnplaint, arrest s,arrant.

orinfoJmation

. * t *

The mid-trial shift . . . illustrares the preju

dice inherent in an information *'hich fails t

specifl' an essential clenrent of the rrtfensel

The defendant is given rnsufficrent notlce t

prepare a defense. he proceeds to trial wit

factual issues undefined. and the prosecutio

is left "free to roanr at la;qe-to shift irl

theory of criminalitl. so as ro take advantag

of each passing \.icissitucle of [he trial an

appeal."

g)5 F 2d at l0{6 (enrph.rsis ad.'..t) (..:.1.io

bringing a seconcl desree ;;;;-::..*"::

Dul)reme uourt has held that

*'" in'tl''t ;'l#:"" T:"#11';t

't

l:]:"':'tY:'"lur 'ur"g'u,"a' ror the protec-

obligation. "'"

-:"

Irruct rrs tlon of all u'ho are charged *ittr oirens".

ailure of the prosecutil) :.^.,.n, to be disregarded in o"du. tn

Id. at 339 (footnote and citations omitted)

(emphasis supplied).

The facts in the instant case demonstrate

that Gray's conviction significantly violated

l. A number of states have had occasion recent-

ly to approach this issue. The results have

been remarkably similar. Addis v. State, Ind.,

1404 N.E.2d 59, 62 n.2 (1980) (,.tt woutd be

I fundamental error to convict a criminal defend-

pnt upon a charge never made.")i State v.

Booker, La., 385 So.2d 1186, llgl (1980)

("[N]otice of the specific charge, and a chance

to be heard in a trial of the issues raised by that

charge" are constitutionally mandated.); State

t,. Handley. 585 S.W.2d 458, 461 (t\Io.l9Z9)

("A court is tvrthout jurisdiction to trv a

person for an offense ut-iess the offense has

been charged by information or indictment.',).

2. There is, as noted by the dissent, some sup_

port for rhe proposition that the insufficiency

of an information may not be fatal if the ac_

cused received actual knowledge of the specific

crime with which he is charged. Goodloe v.

Parratt, 605 F.2d lO4l, 1046 (8th Cir. 1979).

This unfortrrrrate di(ta has been ignored by

subsequent decisions which have cited Good-

loe. See generally Ltnited Srates v. Bonilla.6lg

F.2d I373, 1385 86 (lst Cir. l98l): united

States r.. Partsien.5lS F supp 24. 26 (D. N.D

lrl. I , i.

f-r *e ra,ure o, ,1"^ prosecutio\ infrict.merited punishment on some whogive Gray notice in the infoimatU

"] lX are guilry.

:l[il#,j[fiWil.r.;,"3":i'd1y,7, uru s,, ,,, 6s s ct,,

convicting " a"r*a",,""1.i"".xff:r":\ ffiT,T,";::",;:fi,;1?ilIn*"ffi (

:1,#fl,:,":ll.#*::*j"#; tf.: ;;+;,",iill',,{n" court norerr the

ffi;il/,',tttteoscates-.v-3tew{r1technicalnatureoftheobjectionraisedbut

(eth cir. rss,',,-J#Kl'2d 8y.' 907

reasoned that

ffirtro;ret'.Unitedthe[accused]isentitIedtohaveaninfor.

L.Ed.2d 2sz se60); ,,,|"Y.f,;tl :,''"':1,! mation '.",';;;;,,'i;dicate thp exacr or-ta'Lo"zd'ztjz (1e60); united skres v. B""i;;, ;;;";'."'

^

"r'jlj;,:''ili

lT..i* 1r; \

587 l'.2d B40, B4B (6th,Cir. t9?8). ir*; make inrelligent-plJpu.r,ion of his de_ff,|, tff:1[::,J:",",ion must il;"il r"n." ,-i.]oi.,,",*i*o:

I

i-rrr, ar"la;;; :';rq"poses

behind the rhe form of rhe charge is the re-

lH_,::;i,::ffiJ"Jil',tffi,^"*"fl::l ii",:.,11;,1,""j,:t:;::::,ling authorit.r, I

;',",1:""t :: :";,:'""0":",1: Tit;ii""j ii: *,I;::":Xi1;",::rl":i ::*,1::T;:l )

9Y

s\a

$:\\U

I3$\

$

{*\;H

5\$l{

1\ilt Il I F

}!d

li}] fi:i,E

l Jj

:ql

;+

f

gyi

:*:(

r

*rt'

t\-"-r

's,\

i3)

lil{ B

l- uj

------; t\\=

B

\r$

s-__->

B

hL

1IY

t

\-

!>

a

\ \ts\-

\

; I' \ ,\

ki:\

_1 )11

---t 3t

aY

":-, \

\Y

----- S

\\\

\u\o4=

?4te

J3Y

t

I\lL_e{'I13lY

-

E

{

etz:

Yigt+

d

s1

rd

A

J1

,.r1\'-

S

?

--l

d

'/a

?

.\)lYdtP

c2<

>

*_,56a

\)!

/^

4F)\16dov

%

(

,Ll\

'\

'\

,\

--.---__