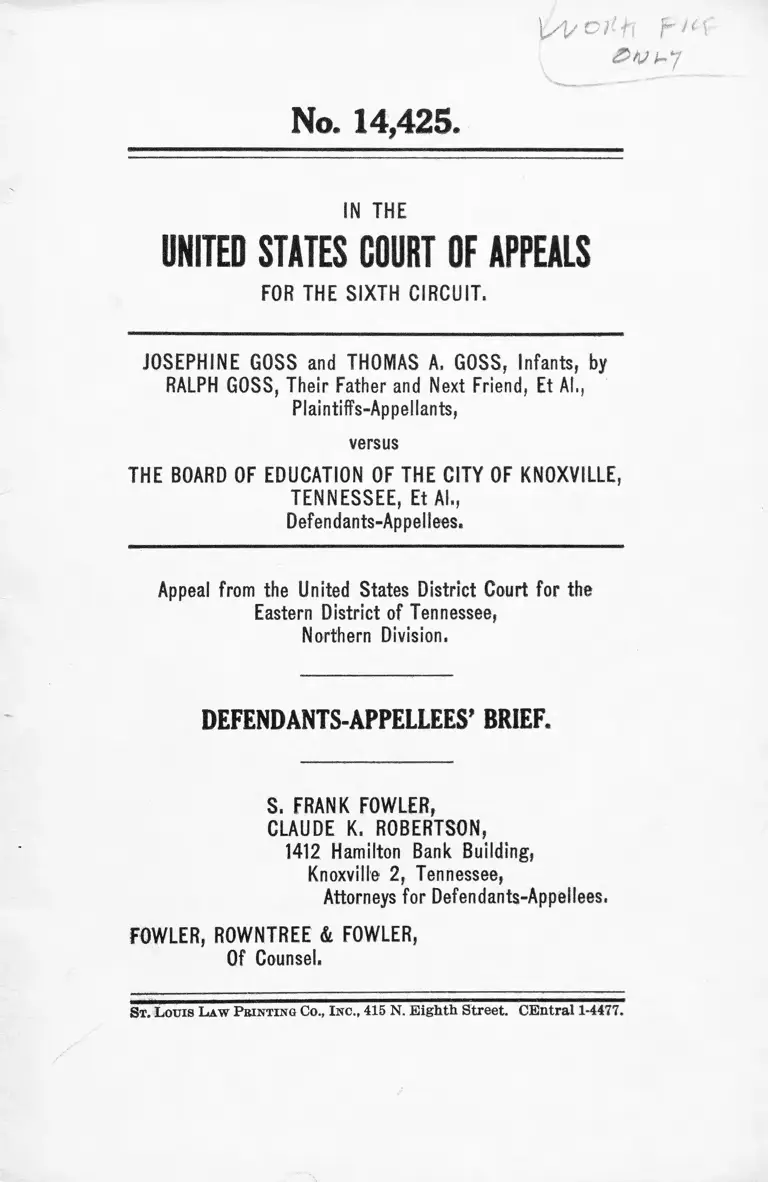

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Defendants-Appellees' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Defendants-Appellees' Brief, 1961. fc55b5f6-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2a979d35-684b-46bb-859d-a92272d3f247/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-defendants-appellees-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 14,425

Iy V V f t f t f^n

£ > V I~ 7

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

JOSEPHINE GOSS and THOMAS A. GOSS, Infants, by

RALPH GOSS, Their Father and Next Friend, Et A!.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF KNOXVILLE

TENNESSEE, Et Al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Tennessee,

Northern Division.

DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES' BRIEF.

S. FRANK FOWLER,

CLAUDE K. ROBERTSON,

1412 Hamilton Bank Building,

Knoxville 2, Tennessee,

Attorneys for Defendants-Appellees.

FOWLER, ROWNTREE & FOWLER,

Of Counsel.

S t . L oots L aw P rinting Co., I nc ., 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

COUNTER STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS INVOLVED.

I. Does the evidence establish that the adoption by the

board of a plan of desegregation for Knoxville public

schools at the rate of one grade a year beginning with

the first grade, rather than at a faster rate, was necessary

in the public interest and consistent with good faith!

The Court below answered the question Yes.

Defendants-appellees contend that the Court’s answer

was correct.

II. Whether the constitutional rights of some of the

plaintiff Negro school children suffered a violation under

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 IT. S. 294, because of

the adoption of a plan of desegregation at the rate of one

grade a year, beginning with the first grade, so that, the

said plaintiff children being in grade two or higher grades

at the time the plan became effective, their annual pro

motion will prevent the desegregation from catching up

with them.

The Court below answered the question No.

Defendants-appellees contend that the Court’s answer

was correct.

III. Whether the constitutional rights of the plaintiff

Negro school children have suffered a violation through

the adoption of a plan of desegregation which includes

the provision that a school child of either race can choose

not to attend a school theretofore used only by the other

race or whose membership, or the membership of the

child’s grade, is predominantly of the other race.

The Court below in effect answered this question No.

Defendants-appellees contend that the Court’s answer

was correct.

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF BRIEF.

Page

Counter Statement of Questions Involved...........Prefaced

Counter Statement of F a c ts ........................................ 1

Argument ...................................................................... 7

Table of Cases.

Board of Education of St. Mary’s County v. Groves

(C. A. 4, 1958), 261 F. 2d 527 .................................. 14

Boson v. Rippy (C. A. 5, 1960), 285 F. 2d 43....... 19,20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954) . . 2, 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 IT. S. 294

(1955) .......................................................2,3,9,10,12,13

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro (C. A. 6,

1956), 228' F. 2d 853 ................................................. 15

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ...................................... 10

Evans v. Buchanan, 152 F. Supp. 886, aff’d 256 F. 2d

688, 172 F. Supp. 508 ................................................. 11

Evans v. Ennis (C. A. 3, 1960), 281 F. 2d 385 .........10,14

^-'' Kelley v. Board of Education of Nashville (C. A. 6,

1959), 270 F. 2d 209 ................................................. 10

, /Kelley v. Board of Education of Nashville, 159 F.

Supp. 272 .................................................................. 20

/fcSwain v. County Board of Education (E. D. Tenn.),

138 F. Supp. 570 ........................................................ 4

Pettit v. Board of Education of Harford County, 184

F. Supp. 452 ............................................................. 14

vf.

Statute Cited.

49 Tenn. Code Ann. 1741-1763 20

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF APPENDIX.

Page

Stipulation Eeacl .......................................................... lb

Excerpts from Transcript of Testimony:

Excerpts from Deposition of Dr. John H. Burk

hart ........................................................................ lb

Excerpts from Deposition of Robert B. Ray ....... 7b

Excerpts from Testimony of Andrew Johnson . . . 8b

Excerpts from Deposition of R. Frank Marable. . . 16b

Excerpts from Deposition of Mrs. J. E. Barber... 20b

Excerpts from Deposition of Elizabeth Pearl Bar

ber .......................................................................... 21b

Excerpts from Deposition of Theotis Robinson, Sr. 21b

Excerpts from Deposition of Berneeze A. W ard... 23b

Excerpts from Deposition of Donald E. Graves . . . 23b

Excerpts from Deposition of Albert J. Winton, Sr. 24b

Excerpts from Deposition of Ralph G oss...... 25b

Excerpts from Testimony of Thomas N. Johnston. 26b

No. 14,425

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

JOSEPHINE GOSS and THOMAS A, GOSS, Infants, by

RALPH GOSS, Their Father and Next Friend, Et AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF KNOXVILLE,

TENNESSEE, Et Al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Tennessee,

Northern Division.

DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES’ BRIEF.

COUNTER STATEMENT OF FACTS.

The answer of clefendants-appellees averred that the

Knoxville public schools for generations have been oper

ated on a segregated basis, that the Negro schools and

schooling were as good as the white, that desegregation

is not sought or desired by the vast majority of both races

2

in this community, that the board has been compelled to

reconcile its duty to desegregate, as set out in Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 TJ. S. 294, with its duty to con

duct efficient, undisturbed and continuous schooling, un

marred by the possibility of interruption from drastic,

unpopular change, that the board felt that the desegrega

tion of schools could be accomplished with a minimum of

disruption only if undertaken in a planned, deliberate

fashion, and that no emergency existed which compelled

immediate preferment of the claims of the plaintiffs over

the continued orderly teaching and training of the chil

dren of Knoxville (32a-34a).

It was admitted by the answer that segregation of

schools in Knoxville was required by the Constitution of

1870 of the State of Tennessee and statutes enacted there

under (30a). Segregation was a part of the social pattern

of Knoxville (93a, 270a).

It was stipulated that at the close of school in June,

1960, the school system of Knoxville consisted of 40

schools, total enrollment of 22,448 students, of whom 4,786

were Negro students and 17,662 were white, that of 879

principals and teachers, 712 were white and 167 were

Negro, that the quality of teaching for Negroes was equal

to that for white pupils, that there is no difference in the

salary schedule of Negro teachers and white teachers and

that the physical facilities for both white and Negro

pupils were excellent (52a).

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court announced its first

opinion in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483.

This was promptly called to the attention of the Board

of Education of Knoxville, who decided to await the

further clarification promised by the Supreme Court

(217a-218a, 237a). At this early date the Board felt that

desegregation in Knoxville would present very few prob

lems (226a).

On May 31, 1955, the Supreme Court announced its sec

ond opinion in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 IT. S.

294.

On June 15, 1955, Thomas N. Johnston became Superin

tendent of Knoxville City Schools (219a, 269a).

On June 16, 1955, Mr. Johnston convened his adminis

trative staff to decide how best to comply with the Brown

decree (26b).

On July 8, 1955, the staff met with the Board of Educa

tion for the same purpose (26b, 220a).

Before July 20, 1955, a committee went to Evansville,

Indiana, and reported back to the Knoxville Board as to

how desegregation had been effected there (26b).

On July 20, 1955, a meeting of white school principals,

staff and board members was held. At that time the

grade-a-year plan was first suggested (27b).

In the first week of August, 1955, a meeting was held

of Negro principals, staff and board members (27b).

On August 2, 1955, a series of staff meetings began

(28b).

On January 26, 1956, a meeting was held of Negro prin

cipals and general supervisors (28b).

On February 2, 1956, began a series of joint meetings

of white and Negro principals (29b).

On March 7, 1956, as a result of study by this group

eight different plans, or different combinations of grades

in step desegregation, were suggested to the board (30b,

227a). The Superintendent submitted a compilation of

materials to the board (127a).

At this point of time the ominous situation at Clinton,

Tennessee (only eighteen miles from Knoxville) began to

claim attention: On January 4, 1956, the United States

__ t>__

4 —

District Court at Knoxville (the same Court and Judge

from which this appeal is taken) had ordered desegrega

tion of the Clinton High School beginning with the fall

term on August 27, 1956 (59a). McSwain v. County Board

of Education, 138 F. Supp. 570. Before August 27th there

were occurrences indicating this desegregation would be

disorderly (130a-131a). This was a source of worry to

the Knoxville Board (229a). This deterrent to desegrega

tion (130-131a) coupled with the demands upon the board

members’ time flowing from an extensive building pro

gram (169a-171a, 223a-224a, 255a-256a, 337a, lib) and

normal tedious budget planning (227a, 228a), and the

wisdom of protecting new buildings from vandalistic de

struction (231a) as well as protecting the children them

selves from disorder and harm (34b) made the Knoxville

Board feel that it would be wise to wait and see how

the Clinton desegregation order should work out (232a).

The Clinton experience in the fall of 1957 was bad.

There were mass meetings and mobs, threats to lives of

the school Principal and Negro students, mobilization

of National Guardsmen 600 strong and concentration also

of 100 State Highway Patrolmen in Clinton, a parade of

hooded individuals in 125 automobiles, blasting of a Negro

home, rock and egg throwing, 16 arrests for violating an

order of the United States District Court, and an investi

gation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation upon direc

tion from the Attorney General of the United States (59a-

60a). The unrest continued: One year later, on October

5, 1958, the Clinton High School was to suffer bomb dam

age in excess of $250,000.00 (63a). In the meantime

serious disturbances of the same nature occurred in the

sister city of Nashville, Tennessee, as well as in Little

Rock, Arkansas (62a) and like trouble was openly threat

ened for Knoxville, notably by John Kasper (61a-62a,

235a).

— 0

The District .Judge brought his own testimony to this

record. The Court was “ concerned—gravely concerned—

with the incidents of unrest and violence which have at

tended the desegregation of schools in nearby communi

ties . . . some are matters with which this Court has had

to deal, and of which it takes judicial notice.” The Court

referred to “ considerations which weigh so heavily upon

the Court,” to “ realities with which it has had acrid ex

perience” (346a) and adds: “ Traditions, ways of think

ing, aspirations, human emotions—all are involved.

Emotions are sometimes stable, sometimes explosive. This

Court has had experience with both. It rather anticipates

that the emotions of the people of Knoxville are under

control. It does not know. It would have had the same

expectation of another community. It was wrong” (347a).

The Knoxville Board felt that these circumstances

compelled delay in desegregation, particularly in view

of the Supreme Court’s “ deliberate speed” language

(231a-232a). Nevertheless the school personnel continued

to work towards a compliance with the Supreme Court’s

Brown decree.

Despite the trouble in neighboring Clinton, the case of

Dianne Ward v. Board of Education of Knoxville was filed

in the United States District Court at Knoxville on Janu

ary 7, 1957, seeking desegregation of Knoxville schools

(61a). This case was later dismissed, for what in effect

was failure to prosecute, on June 1, 1959 (63a).

Up to and since the filing of the Ward case there were

many petitions and applications for desegregation made

to the board by organized groups and by some Negro

parents and preachers (130a, 136a, 139a-140a). The board,

however, felt that it was more reliably informed, in other

ways, that the great bulk of both Negroes and whites in

Knoxville did not want desegregation, or did not want it

under existing conditions of unknown threats (275a)

6 —•

to orderly schooling (93a, 95a, 96a). This opinion of the

board was later fully vindicated and upheld by the unan

imous testimony of those plaintiffs who testified in the

present case of Goss v. Board of Education, for they as

signed, as the only ground for the desired desegregation,

mere convenience of closer proximity to white schools,

varying from a difference of one city block upwards in

distance (20b-25b).

Weighing these factors and others (96a-98a, 151a) the

Board of Education waited until April 8, 1960, before filing

the plan of desegregation now under consideration.

This plan was chosen to start with as promising less dis

turbance in the schools (102a-108a, 149a). Since it in

volved only a comparatively few pupils, administrative

problems would be minimized (271a). This includes

teacher-pupil relationships and problems of discipline

(271a). The normal difficulty of obtaining teachers is

increased least by this plan as compared with other plans

(272a). It provides time to solve problems of zoning,

transfer and assignment (273a) and lessens the opportunity

for development of prejudices (274a-275a). It most nearly

accorded with the sentiment of the community and was

least likely to imperil receipt of public funds needed to

satisfy the school budget (276a). It eliminated problems

stemming from difference in achievement levels of pupils

in the same grade (278a-281a).

— 7 -

ARGUMENT,

The United States District Judge, four members of the

School Board, and the School Superintendent and per

haps his staff are afraid that this community will be

brought to an unjustified risk of personal and property

damage, interruption of schools and internal bitterness.

The Judge ordered the Clinton desegregation and suffered

under the weight of ensuing developments. The School

Board has been sensitive and apprehensive.

There is an irreducible core of wisdom and justice in

the questions, why possibly expose school children and

others to personal indignity and other harm! Why

snatch away an atmosphere of orderly attendance, study

and emotions? Why create a serious risk of bomb or other

damage to expensive hard-to-obtain school buildings?

To this the plaintiffs reply that the Supreme Court

says you must, regardless of these apprehensions.

But the Supreme Court also said: “ Weigh the equities.”

Here we find a conclusion by judge and school board alike

that the public and common benefit, both to whites and

Negroes, far outweighs the convenience to six or eight of

the plaintiff children of walking a shorter distance to

school which is the only equitable factor testified about

in this case on their behalf. They are at no disadvantage

otherwise and have complained of none, except as to Ful

ton High School which is not within our present dis

cussion.1

i At Fulton High School certain technical and vocational courses were

offered to w hite students. At A ustin H igh School the full equivalent

was not offered to Negro students. Paragraph 1 of the Court's judgm ent

directed th a t the board subm it a plan which would m ake the omitted

courses available to Negroes (348a). Such a plan was filed on March 31,

1961.

— 8 —•

T.

Does the Evidence Establish That the Adoption by the

Board of a Plan of Desegregation for Knoxville Public

Schools at the Rate of One Grade a Year Beginning

With the First Grade, Rather Than at a Faster Rate,

Was Necessary in the Public Interest and Consistent

With Good Faith?

The Court Below Answered the Question—Yes.

Defendants-Appellees Contend That the Court’s Answer

Was Correct.

The plaintiffs-appellants miss both the spirit and the

letter of Brown v. Board of Education when they state

that “ only the type of considerations explicitly detailed

by the United States Supreme Court could support” defer

ment of total desegregation, and that the considerations

are limited to the five mentioned in their brief at pag'e 17.

The first Brown opinion (347 U. S. 495) at the very end,

where the Court is striving to clarify the import of its

decision, refers to “ the great variety of local conditions”

and then directs further argument of questions 4 and 5.i * 3

The second part of question 4 was “ may this Court, in

i “4. A ssum ing it is decided th a t segregation in public schools violates

the Fourteen th Amendment.

“ (a ) would a decree necessarily follow providing that, w ith in the

lim its set by norm al geographic school d istric ting , Negro children should

forthw ith be adm itted to schools of the ir choice, or

“ (b) m ay th is Court, in the exercise of its equity powmrs, perm it an

effective g radual adjustm ent to be brought about from existing segre

gated system s to a system no t based on color distinctions?

“5. On the assum ption on which question 4 (a ) and (b) are based,

and assum ing fu rth er th a t th is C ourt will exercise its equity powers to

the end described in question 4 (b),

“ (a) should th is Court form ulate detailed decrees in these cases;

“ (b) if so, w hat specific issues should the decrees reach;

“ (c) should th is C ourt appoint a special m aster to hear evidence w ith

a view to recom m ending specific term s for such decrees;

“ (d) should th is Court rem and to the courts of first instance w ith

directions to fram e decrees in these cases, and if so w hat general direc

tions should the decrees of th is Court include and w hat procedures

should th e courts of first instance follow in a rriv ing a t the specific term s

of more detailed decrees?”

the exercise of its equity powers, permit an effective grad

ual adjustment to be brought about from existing* segre

gated systems to a system not based on color distinctions?”

Question 5 assumed that tlie court would exercise its

equity powers, and then proceeds to ask, among other

things, “ should this Court remand to the courts of first

instance with directions to frame decrees in these cases,

and if so, what general directions should the decrees of

this Court include and what procedure should the courts

of first instance follow in arriving at the specific terms

of more detailed decrees?”

In its second opinion the Court harked back to the first

opinion saying “ Because these cases arose under different

local conditions and their disposition will involve a variety

of local problems, we requested further argument on the

question of relief,” and proceeded to say:

“ Full implementation of these constitutional prin

ciples may require solution of varied local school prob

lems. School authorities have the primary responsi

bility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these

problems; courts will have to consider whether the

action of school authorities constitutes good faith im

plementation of the governing constitutional princi

ples. Because of their proximity to local conditions

and the possible need for further hearings, the courts

which originally heard these cases can best perform

this judicial appraisal. Accordingly, we believe it

appropriate to remand the cases to those courts.

“ In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tradi

tionally, equity has been characterized by a practical

flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility

for adjusting and reconciling public and private

needs. ’ ’

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 IT. S. 294, 300.

These opinions disclose awareness of the existence, but

not the precise outlines, of local problems in countless

school districts in the United States. The Supreme Court

did not claim familiarity with varied local conditions;

foresaw the wisdom of proper evaluation of these by the

local judge; and directed consideration by the equity ap

proach, with decision reconciling public and private rights

and postponing one or the other where unavoidable. We

assume that one objective of this decision was to provide

a way to desegregate with a minimum of bitterness, riot

ing and hate.

The Court would not then stultify itself, as plaintiffs

urge, by adding to this careful disposition an exclusive

enumeration of precise local factors that could be con

sidered by the local judge and school authorities.

In Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, a case cited by the

plaintiffs, the school board in Little Rock, Arkansas sought

to postpone the operation of their plan of desegregation

upon the ground that hostile conditions compelled it. The

Supreme Court denied this application for postponement

because the hostility was directly traceable to actions of

the Governor and the Legislature of Arkansas taken for

the very purpose of circumventing the Court’s decision

in Brown v. Board of Education. That case has no kin

ship with this case at all.

This Court’s decision in the case of Kelley v. Board of

Education of Nashville (C. A. 6, 1959), 270 F. 2d 209 is

controlling here. In that case the grade-a-year plan be

ginning in the first grade was approved by this Court for

the City of Nashville, Tennessee.

The importance of variation in local conditions is dem

onstrated by comparison of the factual background of the

Kelley case (as well as the case at bar) with that of Evans

v. Ennis (0. A. 3, 1960), 281 F. 2d 385, which arose in

11 —

Delaware. In the latter case the Court of Appeals had to

pass upon arguments advanced by the school board much

like those here presented in this Brief, namely, a back

ground of traditional segregation, the emotional impact

ot desegregation, possible interruption of schooling, strife,

etc. However, at the outset of that case the local judge,

Judge Leahy, sitting as the United States District Court

for the District of Delaware, had decided on July 15, 1957,

in the case of Evans v. Buchannan, 152 F, Supp. 886 (af

firmed 256 F. 2d 688 on July 23, 1957) that there should

be no step desegregation in Delaware but that the schools

should be thrown open to Negro pupils at the fall term

ot 1957. Thus the Court of Appeals, Third Circuit, in

reaching its decision on the second appeal, 281 F. 2d 385,

had the support of a decision by the local judge that in

his opinion the factors mentioned above were not of suf

ficient seriousness to outweigh the Negroes’ right to im

mediate fully desegregated schooling. The occasion for

the second appeal of this case to the Court of Appeals was

a decision of District Judge Layton, 172 F. Supp. 508,

rendered on April 24, 1959, in which Judge Layton dis

regarded the mandate of the Court of Appeals and ordered

a grade-a-year plan of desegregation beginning in 1959,

based upon the ground that the mentioned factors of hos

tility, etc., and others were of sufficient weight to require

a slow plan, thus contradicting Judge Leahy’s earlier

decision in which the Court of Appeals had concurred.

The Court of Appeals was fully justified in reversing

Judge Layton’s judgment as being in contravention of its

mandate, and also was doubtless justified in saying, as it

did, “ concededly there is still some way to complete an

unqualified acceptance though we cannot conclude that

the citizens of Delaware will create incidents of the sort

which occurred in the Milford area some five years ago.

We believe that the people of Delaware will perform the

duties imposed on them by their own laws and their own

— 12

courts and will not prove fickle to our democratic way of

life and to our republican form of government.” 281 F.

2d 389.

In this case, however, this honorable court does not

have the comforting benefit of any prior opinion or ad

judication by the District Judge in the Eastern District

of Tennessee that local conditions are such as to permit a

faster desegregation than that proposed by the plan now

under review. On the contrary, the record contains very

strong* expressions from the local judge which reveal deep

grounded fears, predicated upon previous experience vir

tually within the confines of the Knoxville suburban area.

It is likely that the District Judge at Knoxville, in order

ing desegregation at Clinton in 1956, felt the same as the

Knoxville Board of Education felt in May of 1954, when

the first Brown decision was announced, that is, that no

particular difficulty in bringing about desegregation in

Knoxville Public Schools would be encountered. It was

a matter of considerable surprise and horror to the District

Judge and to the citizens in this part of the state that the

Clinton incidents of violence, hatred and prejudice fol

lowed upon an order of the Court which was founded upon

a belief that no such occurrences would take place.

We sincerely urge that this local situation be left to the

handling of the local judge, as the wisdom of the Supreme

Court has directed.

— 13

IT.

Whether the Constitutional Rights of Some of the Plaintiff

Negro School Children Suffered a Violation Under

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, Because

of the Adoption of a Plan of Desegregation at the Rate

of One Grade a Year, Beginning With the First Grade,

So; That, the Said Plaintiff Children Being in Grade

Two or Higher Grades at the Time the Plan Became

Effective, Their Annual Promotion Will Prevent the

Desegregation From Catching Up With Them.

The Court Below Answered the Question—No.

Defendants-Appellees Contend That the Court's Answer

Was Correct.

The plaintiffs’ Brief at page 28 correctly recognizes that

the Brown opinion, 349 U. S. 294, established the principle

that the personal interest of the particular plaintiffs may

he deferred in favor of the public interest.

This admission completely controls this question. The

plaintiffs so far have been subjected to nothing more than

a deferral of their rights. The plaintiffs have full right

to go back to the District Court and ask for a reconsidera

tion, or a further consideration, of their rights, in the

light of the year or two of experience under the plan.

It is impossible to disassociate the plaintiffs themselves

from the other members of the class that they represent.

If it be true that the public interest justifies the grade-a-

year plan, then whatever deferral or deprivation of per

sonal rights these particular plaintiffs suffer is precisely

the same thing to which the balance of the class are sub

jected. The very process of weighing the equities means

that somebody’s rights are going to suffer because they

are not of a weight equal to the opposed rights. This is

the type of judicial handling which the Supreme Court

itself has determined to be the most appropriate for the

— 14 —

adjudication of tills unique problem. If the enrollment of

the plaintiffs themselves would tend to bring about the

feared events, the occurrence of which would work public

injury outweighing the injury or deferral of the plaintiffs’

rights, then it is within the province and even the duty

of the judge of equity to give priority to the public rights.

We remind the Court of the language of the answer of the

defendants in this case, stating that no exigency existed

which required preferment of the rights of these plaintiffs

over the rights of the public, and we also remind the Court

of the proof that these very plaintiffs have asserted in

their testimony as major ground of complaint only that in

some instances white schools were closer to them and they

did not like the inconvenience of going to a school some

what farther away. The opinion in Evans v. Ennis, supra,

assumed that there would be no emotional disturbances,

conflicts or interruptions of the orderly processes of public

education caused by full desegregation. This implies that

if any real fear of these things had existed, the Court

would not have gone the full distance of a wide open

desegregation.

Plaintiffs cite Board of Education of St. Mary’s County

v. Groves (C. A. 4, 1958), 261 F. 2d 527. Here, however,

only one plaintiff was accorded admission ahead of her

Negro brethren, under very special circumstances. It ap

peared that the plaintiff \ akhw was seeking admission to

the segregated twelfth grade; her brother was already in

the desegregated ninth grade, and the plan was proceed

ing on a schedule which "was to bring about the very next

vear the desegregation of the tenth, eleventh and twelfth

grades. The present program of the Knoxville Board of

Education and the circumstances are quite different.

Similarly, in Pettit v. Board of Education of Harford

County, 184 F. Supp. 452, the plaintiff pupil was admitted

to the tenth grade one year before the planned desegrega

tion because he had been erroneously denied admission to

the eighth grade where he desired an academic course

available in the white school but not in the Negro school.

Here was an instance of separate but not equal facilities

(See 184 F. Supp. 458-9).

Plaintiff further cites Clemons v. Board of Education of

Hillsboro (C. A. 6, 1956), 228 F. 2d 853, a case from Ohio

in which the District Judge, despite the fact that the

rezoning to effect desegregation was patently gerryman

dered, refused to issue an injunction because, as he said,

desegregation would seriously disrupt the schools. It is

noteworthy that this Court of Appeals, although holding

that the District Judge abused his discretion, did not un

dertake itself to determine what plan would fit, the local

community, but remanded it for further consideration by

the District Judge.

III.

Whether the Constitutional Rights of the Plaintiff Negro

School Children Have Suffered a Violation Through

the Adoption of a Plan of Desegregation Which In

cludes the Provision That a School Child of Either

Race Can Choose Not to Attend a School Theretofore

Used Only by the Other Race or Whose Membership,

or the Membership of the Child’s Grade, Is Predom

inantly of the Other Race.

The Court Below in Effect Answered This Question—No.

Defendants-Appellees Contend That the Court’s Answer

Was Correct.

It is stated at page 29 of plaintiffs’ Brief that the Chair

man of the School Board, Dr. Burkhart, had testified that

the all-Negro schools in Knoxville will remain segregated

because that will be the effect of the racial transfer plan

adopted in connection with the grade-a-year plan of de

■— 16

segregation. This does not accurately present the facts.

Whatever Dr. Burkhart said at that point in the record

(118a) must be taken against the context of his severe

cross-examination at that point. Moreover, his far greater

commitment and dedication to the practice of medicine and

lack of familiarity with the actual details of the transfer

plan and the handling of the transfer problems as a prac

tical matter in the day-to-day life of the City schools

bring the facts into clearer perspective (4b, 5b, 6b).

Dr. Burkhart testified that the Board of Education

charges the administrative staff with the duty of handling

problems of transfer (5b).

The board did not study details of transfer (5b), didn’t

know who would go to what schools (147a) and didn’t

consider the zones in approving the plan (6b).

The handling of transfers had for many years been the

responsibility of the supervisor of personnel, Frank M a ca

ble. and it would continue to be his responsibility to han

dle any transfers occurring under the plan of desegrega

tion. Mr. Marable testified with respect to transfers

under the plan “ if a white person or a Negro person

wanted to, they would get the same consideration” (16b).

Also, “ so far as I am concerned, there is going to be no

Negro school district and white school district. It is just

a school district, regardless of its color,” and “ Race

wouldn’t come into it at all so far as I am concerned”

(17b).

Mr. Marable does not regard the racial ground for a

requested transfer as automatically entitling' the applicant

to transfer, although “ valid” under Paragraph 6 of the

plan, because other valid reasons may exist for denying

it, such as overcrowding at the school to which transfer

is sought. Mr. Marable further points out that requested

transfers could be granted only when “ consistent with

sound school administration” which is the phrase used

— 1.7

in Paragraph 5 of the plan. His testimony dispels any

thought of race ipso facto as a. factor in transfer policy.

The testimony elicited upon the examination of plain

tiffs’ counsel from board members Burkhart and possibly

Moffett concerning the future operation of the transfer

plan was in the realm of theory on the part of these wit

nesses, with a confessed ignorance of the details involved

in execution of the plan. This is to be contrasted with

Mr. Marable’s immediate responsibility for all problems

of transfer, a responsibility to which he was accustomed

and had for many years been personally administering

and with his testimony regarding the details of the plan

which shows appreciation of the relevance of every word

of the plan and a determination to disregard race in con

sidering transfers, as the plan commanded him.

One unrealistic facet of this case is that the plaintiffs’

counsel apparently want children of both races to be

forced to be together in school, despite the preference of

practically all of them for being educated with their own

race. A court order so requiring would go beyond both

the Constitution and the Brown opinions and decree. It

seems particularly irksome to plaintiffs’ counsel that in

Nashville, as they claimed, most of the Negro children

had chosen each year to go to a school predominantly

Negro. In this aspect of the case, the plaintiffs here seek

the Court’s aid to force upon both races association to an

extent not desired by either at this time. The Brown deci

sion does not warrant this.

The plaintiffs have not attacked the new zone map (Ex

hibit 13, 75a) and must concede that the new zoning is

reasonable. Thus the Negroes’ segregation, so far as it

actually exists under this transfer plan, is due solely to

the clustering of their homes in such a way that properly

determined school zones in which they reside are pre

ponderantly Negro.

— 18

If a white mother residing in such a preponderantly

Negro zone requests transfer of her child to a school out

of this zone on the ground of preponderance of Negroes

in the school she can have acceptable reasons. For in

stance, that it makes her feel uneasy that her child is

subjected to more than the usual risks of childhood; that,

as she imagines, he will have more potential non-friends

than friends and more fights and emotional stress; that

her child will learn more at the white school among

friends already known, and in a less disturbing atmos

phere. So the school principal grants a transfer. This is

not a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment in respect

of the Negro child who would have had the white child

as a schoolmate if no transfer had been granted. The

Negro child has not been denied admission to any school

on any racial ground.

Assume further, that a Negro child in the same school

applies for a transfer to the predominantly white school

to which the white transferee is now assigned. The rea

sons supporting the white child’s transfer do not support

the Negro child’s application, but actually work against

it. The Negro child’s peace of mind and educational de

velopment presumably will be less disturbed in the school

where he is already enrolled.

The reasonableness of the location of the school district

lines is established. Therefore, a child must go to school

in the school there located in the absence of substantial

grounds for transfer, and these grounds must be more

than the mere fact that the pupil is a child (whether

white, yellow, red or black) in that grade and wants to

go to another school. The denial of his application for

transfer is not a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In short, the color line is not being illegally drawn when

the school board transfers a child upon his voluntary

request based upon the true assertion that he will learn

better, with less interruption, at the other school. The

validity of this as justification for requested transfer is

not diminished because it happens that it stems from pre

ponderance of a different race in the school. It could stem

from differences in religion, or from personal peculiarities

of the child applicant, or any one of many reasons having

nothing to do with race.

If a child is denied disadvantage due to race as a ground

for transfer, this goes beyond mere protection of the

Negro child’s Fourteenth Amendment rights and hobbles

the school board in the performance of its duty to edu

cate all pupils the best way it can. In this it cannot avoid

dealing with the results of concentration of Negroes in

one place and whites in another. The process of desegre

gation in Knoxville will not find communities of Negro

and white homes equally and thoroughly mixed together,

but typically faces the problem of one race being absent

or in a small minority in each community. This can handi

cap education in the cases of some pupils. When a pupil

makes a voluntary application for transfer in the interest

of better schooling atmosphere for himself, the board is

obligated to help him out.

The transfer of that child, whether white or black, is

not in itself a racial denial of another child’s application;

and if the latter does make an application which is denied

because not reasonably indicative of an improved class

room atmosphere and an improved peace of mind in the

child, the denial is not a racially discriminatory act, but

is simply an act of enforcement of the policy that no

transfer shall be granted without good reason.

Plaintiffs’ Brief cites (p. 35) Boson v. Rippy (0. A. 5,

1960), 285 F. 2d 43, wherein the same transfer provisions

here involved, namely, Paragraph 5 of the Plan, were

held unconstitutional under this reasoning:

“ Nevertheless, with deference to the views of the

Sixth Circuit, it seems to us that classification ac-

a c

cording to race for purposes of transfer is hardly less

unconstitutional than such classification for purposes

of original assignment to a public school.”

In the quoted language, the Court has entirely over

looked the voluntary aspect of the application for transfer,

as contrasted with the compulsory nature of the assign

ments to schools under the old system of segregation. The

former is the act of the individual; the latter is the act of

the state. Only the latter is proscribed.

We agree with Boson v. Kippy in its holding that the

Texas statute governing assignment and transfer of pnpils

made it unnecessary that the Plan should set out the so-

called “ valid” grounds for transfer, contained in Paragraph

6 of the Plan here involved. In fact-, Tennessee has the

equivalent of the Texas statute; Chapter 13 of the Tennes

see Public Acts of 1957 was entitled in part “ An Act to

regulate the assignment, admission and transfer of pupils

. . . ” and is codified at 49 Tenn. Code Ann. 1741-1763.

The reasoning of Boson v. Rippy that such a statute

renders superfluous the so-called racial reasons for trans

fers seem to us to be substantially the same as that in our

discussion above, namely, that it is not the fact of race

that justifies the board in granting the transfer, but it is

the effect of one or more of the things mentioned in the

Tennessee statute: “ effect on efficiency of operation of

this school;” “ the psychological qualifications of the pupil

for the type of . . . associations involved;” “ the psy

chological effect upon the pupil of attendance at a par

ticular school;” “ the sociological, psychological, and like

intangible social scientific factors . . . ; ” “ the possibility

or threat of friction or disorder among pupils or others;”

etc., etc.

The constitutionality of the Tennessee statute is per

haps doubtful. Kelley v. Board of Education, 159 F. Supp.

272, 277. Since Boson v. Rippy recognizes that the trams-

21

fer grounds set out here in Paragraph 6 of the Plan are

legitimate when not arbitrarily applied, adding nothing to

the authorization of the reasonable Texas statute, these

provisions in Paragraph 6 should be upheld, upon the pre

sumption that the Knoxville Board will not apply them

arbitrarily.

The board feels:

That the people of the community, both white and

Negro, approve the board’s handling; that the community

is grateful that there have been no occurrences, such as

those in Little Rock, New Orleans, and next door here at

Clinton; that practically all feel that both equity and

reason are being' served;

That the City schools are on the path to desegregation

and it will certainly be accomplished;

That a minimum speed has been fixed, but no maximum;

that it is quite possible that either or both of the Court

and board may conclude that the process may be speeded;

and

That special situations, such as Fulton High School’s

Technical and Vocational School, are being taken care of

in a way completely responding to the requirements of the

Brown decree.

It is respectfully submitted that the judgment of the

District Court should be affirmed.

S. FRANK FOWLER,

1412 Hamilton Bank Building,

Knoxville 2, Tennessee,

Attorney for Defendants-Appellees.

CLAUDE Iv. ROBERTSON,

FOWLER, ROWNTREE & FOWLER,

Of Counsel.