Green v. City of Roanoke School Board Brief of Appendix on Behalf of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Green v. City of Roanoke School Board Brief of Appendix on Behalf of Appellees, 1962. 08f90c33-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2a990dff-ca05-42f3-97f1-05c41ed753de/green-v-city-of-roanoke-school-board-brief-of-appendix-on-behalf-of-appellees. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

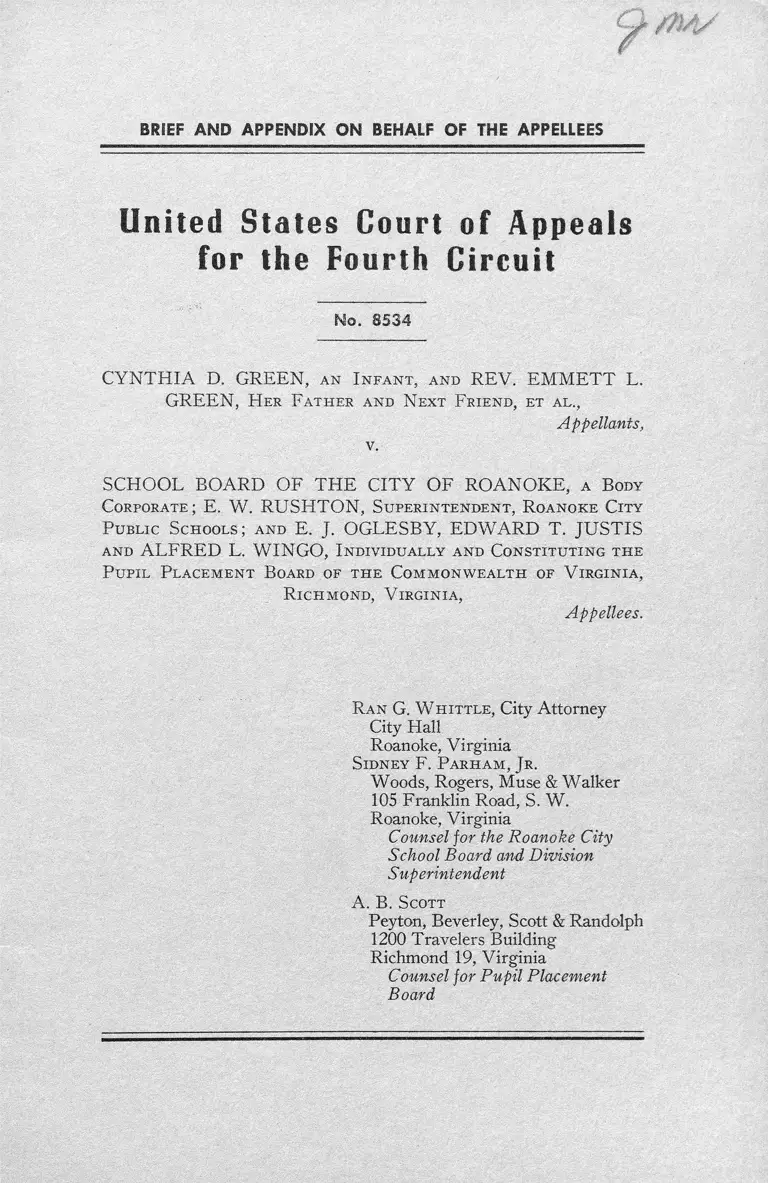

BRIEF AND APPENDIX ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLEES

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 8534

CYNTHIA D. GREEN, a n I n f a n t , a n d REV. EM M ETT L.

GREEN, H er F a t h e r a nd N ext F r ie n d , et a l .,

Appellants,

v,

SCHOOL BOARD OF TH E CITY OF ROANOKE, a B ody

C o r po ra te ; E. W. RUSHTON, S u p e r in t e n d e n t , R o a n o k e C ity

P u b lic S c h o o l s ; a nd E. J . OGLESBY, EDWARD T. JTJSTIS

a nd ALFRED L. WINGO, I n d iv id u a lly a n d Co n s t it u t in g t h e

P u p il P l a c e m e n t B oard of t h e C o m m o n w e a l t h of V ir g in ia ,

R ic h m o n d , V ir g in ia ,

Appellees.

R a n G. W h it t l e , City Attorney

City Hall

Roanoke, Virginia

S id n ey F. P a r h a m , J r .

Woods, Rogers, Muse & Walker

105 Franklin Road, S. W.

Roanoke, Virginia

Counsel for the Roanoke City

School Board and Division

Superintendent

A. B. S cott

Peyton, Beverley, Scott & Randolph

1200 Travelers Building

Richmond 19, Virginia

Counsel for Pupil Placement

Board

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

P r e l im in a r y ................................................... ........-................................... — 1

F acts -------------- ---------------- --------------- -------..................... -..................... 2

A. The Status of the Proceeding................................................. 2

B. The Composition of the Pupil Placement B oard................. 3

C. Integration of Roanoke City Public Schools................ -..... 3

D. “Plan of Desegregation” -----......—-............... -............- 5

I ssues .......................................................................... .......................................... - ^

A r g u m en t ...................................... -......... -.......................................................... 5

1. The Appeal Is Premature ....................................................... 5

2. The Initial Assignment System................................... -........... 6

3. No Discriminatory Criteria Are Applied to Negroes ........... 8

4. The Pupil Placement Protest and Hearing Procedure Is an

Adequate Administrative Remedy..... ................................. - 9

5. The Appellants’ Constitutional Rights Are Individual......... 9

C o n c lu sio n ................... .......................-.......-.............—-............... -.................. 19

A ppe n d ix :

Report of Pupil Placement B oard.................................. — App. 1

Additional Excerpts by Appellees from Transcript......... App. 4

Testimony of E. W. Rushton................ ...................... App. 4

Direct Examination.................................... —- — App. 4

Testimony of B. S. H ilton ........................................... App. 17

Direct Examination ............... - ............................. App. 17

Testimony of Dr. James A. Bayton ...... ............ -....... App. 18

Direct Examination............................. -........... -..... App. 18

Page

Testimony of Dorothy L. Gibney.......................... App. 22

Direct Examination ....................................... App. 22

Testimony of Ernest J . Oglesby............... App. 24

Cross-Examination .... App. 24

Testimony of B. S. Hilton (Recalled) .................... App. 27

Redirect Examination........................ App. 27

Testimony of Dorothy L. Gibney (Recalled) ..............App. 28

Redirect Examination......... ................................... App. 28

TABLE OF CASES

Beckett v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia, 185 F.

Supp. 459 - ......... ............ ......................................... ................ . 3

Briggs v. Elliott (1955), 132 F. Supp. 776..................................... 7

Carson v. Warlick (1956), 238 F. 2d 724.......... ........................ 9, 10

DeFebio v. School Board, et als. (1957), 199 Va. 511, 100 S. E.

(2d) 760 ...... .................................... ................. ........................... 10

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. (2d) 131 ............................................ . 3, 10

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 8534

CYNTHIA D. GREEN, an I n f a n t , and REV. EM M ETT L.

GREEN, H er F a t h e r a n d N ext F r ie n d , et a l .,

Appellants,

v.

SCHOOL BOARD OF TH E CITY OF ROANOKE, a B ody

C orporate ; E. W. RUSHTON, S u p e r in t e n d e n t , R oan o k e C ity

P u b lic S c h o o l s ; and E. J. OGLESBY, EDWARD T. JUSTIS

and ALFRED L. WINGO, I ndiv id u a lly a nd Co n s t it u t in g t h e

P u p il P la c e m e n t B oard of t h e C o m m o n w e a l t h of V ir g in ia ,

R ic h m o n d , V ir g in ia ,

Appellees.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLEES

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

In the appendix of this brief are printed additional ex

cerpts from the transcript of the proceedings before District

Judge Lewis which appellees deem pertinent to the issues

before the court. In addition thereto there is printed in the

appendix the report of the Pupil Placement Board rendered

by it pursuant to the direction of Judge Lewis in his Memo

randum Opinion (Appellants’ Appendix 202a). This report

was mailed directly by counsel for the Pupil Placement

Board to Judge Lewis with copies to all counsel. Apparently

the report was never filed in the Clerk’s Office of the court.

The appellants filed written objections thereto and these are

printed in their appendix at page 212a. It seems appropriate

that the record be completed by the inclusion of this report.

2

FACTS

A.

The Status of the Proceeding

The purpose of the instant action was to secure the admis

sion to certain public schools in the City of Roanoke of

twenty-eight (28) individual Negro pupils who alleged that

the appropriate school authorities had discriminated against

them in denying their applications to attend these schools

because of their race or color. The judgment of the District

Court was that one of the applicants had through admitted

inadvertence and mistake been excluded from a school to

which she was entitled to attend and that she should be

admitted thereo; that applications of fifteen (15) of the

remaining pupils should be reconsidered by the Pupil Place

ment Board, which board was directed to report the results

of its reexamination after the application of “just, reason

able and nondiscriminatory criteria fairly applied” ; and as

to the remaining twelve (12) infant plaintiffs the action of

the school authorities was sustained. The judgment provides

for a hearing at a date to be fixed by the court upon the

report of the Pupil Placement Board and any exceptions

thereto (Appellants’ Appendix 216a et seq.).

The Pupil Placement Board duly reexamined the fifteen

(15) applications and upon such reexamination admitted

five (5) of the original plaintiffs to the schools to which they

sought admission. It reaffirmed its position with respect to

the remaining ten (10) and supplied to the court additional

reasons for its action. Exceptions to this report were filed

by the plaintiffs. No hearing date was requested or set and

the judgment of the court was in fact entered at a date subse

quent to the rendition of the report of the Pupil Placement

Board.

3

B.

The Composition of the Pupil Placement Board

As the court is doubtless aware, an entire new three-man

Pupil Placement Board of Virginia was appointed by Gov

ernor Almond in the summer of 1960. The board so appoint

ed consisted of two members of the State Department of

Education, one of whom is in charge of its Testing Program

in all schools throughout the entire state, and a professor at

the University of Virginia. The actions of this board with

respect to assignment of pupils to the schools of the City of

Roanoke and elsewhere in Virginia are such as to completely

negate the characterization of the original members of the

Pupil Placement Board contained in District Judge Hoff

man’s opinion in Beckett v. School Board of the City of

Norfolk, Virginia, 185 F. Supp. 459, approved by the opin

ion of this court in Farley v. Turner, 281 F. (2d) 131.

C.

Integration of Roanoke City Public Schools

Subsequent to the decision of the Supreme Court of the

United States in the Brown case and prior to the spring of

1960, no individual Negro pupil had sought admission to

any of the public schools of the City of Roanoke theretofore

attended exclusively by white pupils. In 1960 thirty-nine

(39) applications for admission to such schools were re

ceived and in accordance with state law transmitted to the

Pupil Placement Board. Upon consideration of these appli

cations nine (9) pupils were admitted to three (3) schools,

so that for the school year 1960-1961 three (3) of the city’s

schools were desegregated without any action by a federal

court. Two (2) of the remaining thirty (30) pupils were

4

presumptively satisfied with the assignments made by the

Pupil Placement Board, and the remaining twenty-eight

(28) are the infant plaintiffs in this suit. Of that twenty-

eight (28) one (1) was admitted by the court, five (5) were

assigned in accordance with their request upon reexamina

tion of the Pupil Placement Board pursuant to the court’s

direction, and two (2) others (Curtis Strawbridge and

Brenson Long), whose original assignments had been sus

tained by the trial court, were admitted upon reapplication

for the 1961-1962 school term. Thus, of the original thirty-

nine (39) nineteen (19) have now been admitted to desegre

gated schools.

In the spring of 1961 thirty-two (32) additional individ

ual Negro pupils applied for admission to predominantly

white schools. One (1) subsequently indicated a desire to

remain at the school he was then attending and the

following action was taken with respect to the remaining

thirty-one (31): Nine (9) were initially admitted to the

schools applied for and twenty-two (22) denied. Of this

twenty-two (22), twelve (12) protested the initial assign

ments of the Pupil Placement Board and after the hearing

provided by law which was held in Roanoke, the Pupil Place

ment Board reversed its initial action with respect to six (6)

of them and ordered their enrollment in the schools applied

for.

In summary, seventy-one Negro pupils have applied in

two years for admission to predominantly white schools in

the City of Roanoke, Virginia. One (1) voluntarily with

drew his application, twenty-eight (28) are now attending

the schools applied for, twenty-two (22) have not elected

to pursue their applications further, and twenty (20) are

the appellants here.

5

D.

“Plan of Desegregation”

No public announcement has been made or action taken

by the School Board of the City of Roanoke or the Pupil

Placement Board as to the establishment of a “plan of

desegregation”. The plan of the Pupil Placement Board and

the school authorities of the City of Roanoke is to assign

each child to that school which in their judgment is best for

him and the school system without the application of any

discriminatory practice on account of the child’s race or

color.

ISSUES

1. Is the appeal premature with respect to those pupils

whose applications the court below directed the Pupil Place

ment Board to reexamine?

2. Have the individual infant appellants been discrimi

nated against on account of their race or color?

ARGUMENT

1.

The Appeal Is Premature

It is evident from the judgment (Appellants’ Appendix

216a) that the court has taken no final action of any kind

with respect to appellants Melvin Franklin, Walter Wheaton,

Melvin Anderson, Nancy Lee Martin, Robert Harry Rob

erson, Linda Lavern Anderson, Roberta Roberson, Nannie

Roberson, Phillys D. Martin and Cynthia Green. Nothing

in this judgment precludes later action by the district court

6

consistent with the fundamental relief sought by them, i.e.,

admission to particular schools.

The judgment specifically provides for a hearing for these

appellants upon return of the report of the Pupil Placement

Board therein provided. It is submitted that the orderly

admission of justice requires that the appeal of these plain

tiffs be dismissed as premature.

2.

The Initial Assignment System

Appellants’ brief is largely directed toward alleged dis

criminatory practices in the Roanoke school system with

respect to the initial assignment of pupils. They make the

statement that all the Negro schools are organized in a

separate Section II. This is true, but not because they are

schools attended solely by Negroes but because they are

situate in the same geographical area of the City of Roanoke

and spring from the coincidence of residence.

While there is no such actual requirement and none such

was proved, it is only normal and natural that for pre

school registration each year pupils and their parents ordi

narily go to the schools in their area or neighborhood. This

has been a long standing custom, has long been known and

understood, and anything else would be inconvenience and

confusion.

If they do not desire or prefer some other specific school

they do nothing, and the temporary assignment is later acted

on in more or less routine manner.

If, on the other hand, they prefer or desire some other

specific school, they have only to say so, and this is so irre

spective of race. That they can do so, and that in some

instances they do so, is shown by the facts of this case.

7

If no other specific school is requested, whether it be a

white child, or negro child, or a child of any other race,

it is naturally assumed that the pupil and parents are satis

fied and voluntarily desire such placement. This, we submit,

is normal, natural, sensible, and logical practice, applicable

to all races and in all cases; and it involves no essential dis

crimination as to race, for as was said by the court in

Briggs v. Elliott (1955), 132 F. Supp. 776 (one of the

original cases on remand from the Supreme Court of the

United States) :

“Having said this it is important that we point out

exactly what the Supreme Court has decided and what

it has not decided in this case. It has not decided that

the federal courts are to take over or regulate the public

schools of the states. It has not decided that the states

must mix persons of different races in the schools or

must require them to attend schools or must deprive

them of the right of choosing the schools they attend.

What it has decided, and all that it has decided, is that

a state may not deny to any person on account of race

the right to attend any school that it maintains. This,

under the decision of the Supreme Court, the state may

not do directly or indirectly; but if the schools which

it maintains are open to children of all races, no viola

tion of the Constitution is involved even though the

children of different races voluntarily attend different

schools, as they attend different churches. Nothing in

the Constitution or in the decision of the Supreme Court

takes away from the people freedom to choose the

schools they attend. The Constitution, in other words,

does not require integration. It merely forbids dis

crimination. It does not forbid such segregation as

occurs as the result of voluntary action. It merely for

bids the use of governmental power to enforce segre

gation. The Fourteenth Amendment is a limitation

8

upon the exercise of power by the state or state agen

cies, not a limitation upon the freedom of individuals.’'

The City of Roanoke has been in the process of an exten

sive building program. During that period it has not always

been practicable to assign pupils on a strictly geographical

basis on initial assignments. It may well be true that during

that period Negro pupils who live closer to other schools

than to Section II schools have been assigned to Section II

schools. There is nothing in the record to support the as

sumption of appellants that this situation is a fixed policy

of the local school board or one that will not be changed now

that the building program is substantially complete. This

would appear to be particularly true in view of the substan

tial progress made in the city toward a voluntary desegre

gation of the schools.

3.

No Discriminatory Criteria Are Applied to Negroes

The record does not support appellants’ contention

that discriminatory criteria were applied. The trial court

in its opinion (Appellants’ Appendix 202a) specifically

found that certain of the criteria were not discriminatory,

that two criteria were discriminatory and required further

evidence as to a third. The appellees have abandoned those

criteria disapproved by the trial judge and submitted

to the judge evidence supporting the one question. Com

mencing with applications for assignment for the year 1961-

1962 the criteria applied are those not disapproved by the

trial judge.

9

4.

The Pupil Placement Protest and Hearing Procedure

Is an Adequate Administrative Remedy

It is submitted that the opinions of this court and the

district courts in Virginia prior to the constitution of the

present Pupil Placement Board and cited by appellants are

not applicable to the present facts. It is further submitted

that the results of the use of this procedure in applications

for admission to Roanoke City schools for the year 1961-

1962 refutes appellants’ argument. There were twelve (12)

persons who availed themselves of that procedure and six

(6) of them obtained admission to the schools they desire.

The remaining six (6) failed to challenge the protest ma

chinery in the courts.

5.

The Appellants’ Constitutional Rights Are Individual

As was said by the late Chief Judge Parker for a court

including the present Chief Judge of this court and now

Circuit Judge Bryan in Carson v. War lick (1956), 238 F.

2d 724:

“There is no question as to the right of these school

children to be admitted to the schools of North Carolina

without discrimination on the ground of race. They are

admitted, however, as individuals, not as a class or

group; and it is as individuals that their rights under

the Constitution are asserted. Henderson v. United

States, 339 U. S. 816, 824, 70 S. Ct. 843, 94 L. Ed.

1302. It is the state school authorities who must pass

in the first instance on their right to be admitted to any

particular school and the Supreme Court of North

10

Carolina has ruled that in the performance of this duty

the school board must pass upon individual applications

made individually to the board.”

That in Virginia the board must pass upon individual

applications made individually to the board has been enacted

into law by the General Assembly in the Pupil Placement

Law itself, and that such Act is valid has been decided by

the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, in DeFebio v.

School Board, et cds. (1957), 199 Va. 511, 100 S. E. (2d)

760.

This court again as late as June 28, 1960, reaffirmed its

holding in Carson v. War lick, supra, in Farley v. Turner,

supra, when it said:

"This court has consistently required Negro pupils

desirous of being assigned to schools without regard to

race to pursue established administrative procedure

without seeking intervention of a federal court.”

The Supreme Court of the United States in the second

opinion in the original cases on May 1, 1955, 349 U. S. 294,

said:

“Because of their proximity to local conditions and the

possible need for further hearings, the courts which

originally heard these cases can best perform this

judicial appraisal.”

CONCLUSION

Under the particular facts and circumstances of this

case it is respectfully submitted that the judgment of

the trial court should be affirmed with respect to those

infant plaintiffs who are properly before this court on

11

appeal and the case should be remanded to the district court

for such hearing upon the exceptions of the other infant

plaintiffs as may be appropriate.

Respectfully submitted,

R an G. W h it t l e , City Attorney

City Hall

Roanoke, Virginia

S id n e y F. P a r h a m , J r .

Woods, Rogers, Muse & Walker

105 Franklin Road, S. W.

Roanoke, Virginia

Counsel for the Roanoke City

School Board and Division

Superintendent

A. B. S cott

Peyton, Beverley, Scott & Randolph

1200 Travelers Building

Richmond 19, Virginia

Counsel for Pupil Placement

Board

A P P E N D I X

REPORT OF PUPIL PLACEMENT BOARD

(Mailed to Judge on August 16, 1961)

In accordance with the memorandum opinion of the court

under date of July 7, 1961, the Pupil Placement Board has

re-examined and reconsidered all of the specific cases and

makes the following report:

First, as to Applicant # 9 (Sylvia Long) it developed

during the re-examination that she resides closer to the new

Hurt Park Elementary School which is only four (4) blocks

away and which will be opened for use for the first time

for the school session 1961-1962, than she does to the West

End Elementary School which is at least twelve (12) blocks

away, and in order to reach which the pupil will have to cross

two main and extra hazardous thoroughfares. Wherefore,

the Board reports and submits that this pupil should be

placed rather in the Hurt Park school.

Applicant # 6 (Jerome Croan) has been granted request

ed transfer but to Melrose rather than Monroe where there

is no 6th Grade, and his parents have been or will be so

notified.

Applicant # 8 (Brenson Long) has also been granted re

quested transfer but to Monroe rather than Lee, because

Monroe is closer to his home and his parents likewise have

been or will be notified.

Applicant # 7 (Christopher Kaiser) has also been granted

requested transfer to Melrose because of the sibling rela

tionship, he having a brother who was also placed in Mel

rose. The same as to his parents.

Applicant #15 (Alene Green) was also granted requested

transfer to Melrose since she could not be denied on legiti

mate grounds, and Applicant #26 (Paula Green), her sister,

while still deemed academically unqualified was nevertheless

App. 2

granted transfer to Melrose because of the sibling relation

ship. Their parents have been or will be notified to such

effect.

As to all other applicants the Pupil Placement Board is

still of the opinion that their transfers are academically un

sound and should not be granted for the additional reasons

hereafter assigned in each case, namely:

Applicant # 16 (Nancy Martin), and #24 (Phyllis Mar

tin) live closer to the aforesaid new Hurt Park Elementary

School rather than to the school to which transfer is sought,

because of which this Board feels that they should be placed

in due course by administrative transfer in the Hurt Park

Elementary School.

Applicant #17 (Cynthia Green) is below the mean of the

school presently attended and eleven points below that of the

school to which transfer is desired.

Applicant #20 (Linda Anderson) is seeking to enter the

6th Grade and was 1 year, 4 months below in achievement

at the end of the 5th Grade, her reading level in fact, at the

end of the 5th Grade being equivalent to that for the 4th

Grade, in addition to which she is the sister of Applicant

# 14 next hereinafter referred to.

Applicant #14 (Melvin Anderson) seeks entry into the

4th Grade, whereas his reading level is the equivalent only

to that at the end of the 2nd Grade, and is the brother of

Applicant #20.

Applicant #11 (Melvin Franklin) is seeking to enter the

3rd Grade, whereas his academic achievement is just about

at the lower 25th percentile and his teacher says that he is not

even able to do 2nd Grade work.

Applicant #12 (Walter Wheaton) is in many respects

App. 3

below the mean of the school presently attended and below

the lowest 25th percentile of the school to which transfer is

sought and, in addition, the nearest senior high school to his

residence would be Addison High School rather than Mon

roe to which transf er is being sought.

Applicant #23 (Nannie Roberson) is below the mean in

the school presently attended and just about at the level of

the lowest 25th percentile in the school to which transfer

is being sought.

Applicants #18 (Robert Roberson) and #22 (Roberta

Roberson) did not re-apply for transfer by July 1, 1961, in

addition to which Applicant #22 (Roberta Roberson) is one

year deficient in achievement and both are the siblings of

Applicant #23 (Nannie Roberson).

In substantiation of the fact that a sibling relationship is

taken into consideration and applied by the Roanoke City

Public Schools uniformly to white and negro pupils alike,

affidavits of the Director of Personnel of the Roanoke City

Public School dated respectively July 20, July 21, and July

25, 1961, are attached hereto and asked to be read as a part

of this report. (Attached affidavits omitted because origi

nals in record.)

Respectfully submitted,

P u pil P lacement Board of th e

Commonwealth of V irginia

By Counsel

A. B. Scott, of

Christian, Marks, Scott & Spicer

1309 State-Planters Building

Richmond 19, Virginia,

Special Counsel for the

Pupil Placement Board.

App. 4

ADDITIONAL EXCERPTS BY APPELLEES

FROM TRANSCRIPT

Testimony of E. W. Rush ton

DIRECT EXAMINATION

[tr. PP. 56-58]

Q Mr. Rushton, is it true that there was no action by

the Board or response, as such, on the Plaintiffs’ petition that

came with these individual applications ?

M r. P arham : Which board do you mean?

M r. N abrit : The local School Board.

T he W itness : No action with respect to the decision on

these Plaintiffs.

By M r. N a brit :

Q No, no. On that formal petition that came with the

Pupil Placement form and letter from Mr. Lawson.

A We—if I understand—

Q Petition denied or petition granted ?

A No, no. We sent the applications, as I said, we sent

them to the Pupil Placement Board as they were presented

to me.

Q All right. Now, in your handling of this matter, did

you work under explicit instructions from the Roanoke

County Board, the Roanoke City School Board or did they

allow you to use your own judgment ?

A That was an administrative matter and I handled it

that way.

Q Did you keep them advised as you went along?

A Yes.

Q Did they tell you what to do? Did you have any

meetings where they told you what to do with handling

these ?

A No, no. At the time I met with the Board, I said, I

presented them to the Board and told them that I was going

to send them on to the Pupil Placement Board.

Q Now, before you went down to the Pupil Placement

Board to have this conference, did you make your local board

members aware of the information that you had on these

various pupils; discuss that ?

A We didn’t discuss it, the information that we had. I

told them about the information that was called for and we

were going down with the information that the Pupil Place

ment Board asked us to bring. We had informal meetings

of the Board at which time they were informed about that.

Q Did they give you any instructions or make any rec

ommendations to you or what did you tell them what you

were going to do?

A I just said I was going to, at the request of the Pupil

Placement Board, to meet with them on the 15th of August,

and I got no instructions from them as to what, how they

would proceed or anything of the kind.

Q Did you tell your local board at this time what the

situation was or anything about these various individual

pupils or groups of pupils among this 39 ?

A We just talked in general about the applications we

had, information that I was called to bring and that is what

I was going to go down to talk with the Pupil Placement

Board about. Since we had no responsibility for making

any decisions, there was no need, as I saw it, to do anything

about it here; I mean locally.

* * *

App. 5

App. 6

[ t r . p p . 67-80]

T he Court : That is what they do.

Now I say if you have got any evidence that a guardian

wants a transfer he hasn’t received, then you ought to bring

that guardian in here and let him tell me. Because the

Court is going to assume that is a fact until somebody tells

me to the contrary. And I don’t need counsel on either side.

The best evidence is the person himself. Now, you have 30

of them here who are in that category. Their guardians have

requested a transfer.

M r. N abrit : Your Honor, we are dealing with the moti

vation and the feelings and speculating—the 4000 Negro

children—and why they don’t do something. I cannot agree

on any general reason why those people didn’t do something.

And I am not trying to get you, too, sir.

T he Court: Whether you want to agree to it or not

doesn’t make the slighest difference to the Court. The facts—

M r. N a brit : Very well.

T h e Court: The facts are these: That there is an estab

lished procedure, which you concede on the face of it is con

stitutional, whereby any student who doesn’t like, through

his guardian, the assignment that is routinely made shall

follow a certain procedure. And the procedure is to apply

for a transfer. Now, until either this Court or some other

Court says that basic procedure is wrong, that is, illegal,

then the Court is duty bound to follow it. It cannot do

otherwise.

Mr. N a brit : Well. I would say that I wouldn’t concede

that the statute was constitutional when it is superimposed

upon the fact that the Roanoke situation:—I say its consti

tutional phase, I mean it is constitutional in that it is on the

statute book without any reference to any specific situation.

A p p .7

That was the contention that I thought I made yesterday.

That is what Your Honor was referring to.

T he Court: You are not attacking the constitutionality

of the Pupil Placement Act in this proceeding. If you are,

you need a three-judge court, as far as I am concerned.

M r. N a brit : Yes, sir.

T he Court : So we are accepting it as being a valid enact

ment of law for this purpose.

M r. N abrit : That is correct, sir.

T he Court: And that law, as I understand it, provides

that the pupil shall be in the school where they are duly and

ordinarily assigned except in those cases where the guardian

or parent wants him transferred.

Now, if that is the law, then the burden is upon the appli

cant to do two things: First, to make application for a trans

fer. And, if that transfer is denied, on the ground of race,

then this Court will upset it. If it is not denied on that

ground, then, of course, this Court will not upset it.

Now, that is what we are trying to find out. The only one

thing in this case is whether the 29 or 30, whatever the

number is, whoever complied with the law and filed their

applications, whether or not the denial of their requests was

made on the discriminative basis, on the ground of color.

If it were, the Court has no hesitancy—turn down every

one of those assignments. Now, the burden is upon you to

show that there was discrimination insofar as these trans

fers are concerned. And the only reason, the only legal

reason that they were not assigned to the school of their

choice was because they are colored. Now, I have been

waiting to hear evidence on that subject. That is the only

thing, in substance, that I am going to consider in this case.

App. 8

M r. N abrit : Your Honor, I understand that to be a part

o£ my burden. I maintain that there is another question.

T he Court : What is that ?

Mr. N a brit : Your Honor, that would be the validity of

using it to keep it that way—a segregated school. Now,

when I say the Pupil Assignment Law is valid on its face,

I did not mean it is valid when you use it to preserve segre

gation.

T he Court : Then you or somebody ought to file a proper

suit and test the validity of that very assertion. Because

the Court must start with some premise and the premise is

that everybody is satisfied with his assignment except those

who have made a request for a transfer and it has been

denied. Now, I have to accept that premise. If you say that

the premise is illegal or is a false premise or one that the

Court ought not to accept, then, of course, that would be a

question the Court would have to pass on in an appropriate

proceeding, but this is not it.

Mr. N a brit : I don’t know. I say that it doesn’t matter

for the purpose of the argument I am trying to make.

Perhaps if I state my argument another way, it may be

clearer. That the school authorities, all of them, whatever

their respective duties under the situation are, they have

the duty to initiate desegregation—U.S. Supreme Court.

That they don’t accomplish that by using the Pupil Place

ment Statute to keep a school segregated. They don’t ac

complish that by continuing to make—they don’t live up to

that duty by continuing to make initial assignments on the

basis of race, by having feeder systems, by having all-Negro

schools feed all-Negro schools, and things like that, by pre

serving these various facets of the segregated situation—

perpetuated.

App. 9

T h e Court : I understand what you are talking about.

I had it in Richmond and I had it in several other cases.

If you want this Court to answer it, then you ought to file

the appropriate proceeding before the Court—either use

Roanoke or anybody else you want to and say that they are

in violation of the decision laid down in the Brown Case in

that the local School Board or local body is making no plans

or preparation or isn’t doing anything to reassign the chil

dren so that they be on an integrated basis. If you make that

contention, the Court will have to pass on it in an appro

priate suit. But I am not going to pass on it in this kind of

suit.

M r. N abrit : Your Honor, I don’t want to. We will be

happy to defer the question or whatever Your Honor wishes.

T he Court : The Court in this specific case, the Court

understands that case to be a case whereby the Court is called

upon to determine the individual rights of the applicants

who made application in due form for a transfer to a school

other than that to which they were assigned. And, if the

Court finds that that transfer was denied solely or basically,

without using the word “solely”—too limited—basically on

the ground of color, the Court has no hesitancy in saying

and it will say that it is an improper assignment. Conversely,

if the Court finds that there were basic, solid grounds for

the assignment, refusal of the request, the Court will so

indicate. And that is all that we are going to determine in

this case.

In other words, I am not going to determine—

Mr. N abrit : D o you want me to respond to that, sir, or

save it for later?

T he Court: Y ou may respond, if you want to. Unless

you convince me I am wrong, that is all I am going to

determine.

App. 10

Mr. N a brit : I would point out to the Court at this time

that the Court of Appeals for this circuit has three cases

involving pupil assignments—within the past year, Virginia

pupil assignments: The Jones Case, decided in 1960, involv

ing Alexandria; the Hill Case, involving Norfolk, and the

Dodson Case, involving Charlottesville schools. In each of

those cases—considered the type of presentation that you

have discussed in terms of individual rights as well as con

sidered the overall system of the school system to determine

whether the school authorities have fulfilled their obligation

—developed arrangements for the earliest, practical elimina

tion of discrimination in the system. This is what the

Brown Case, the second Brown Case required.

T he Court: May I ask you this—that is correct; it did

do that.

M r. N abrit : They even—

T he Court : Wait a minute. It did do that a time when

the local bodies, the local School Boards were attempting to

fulfill the function of controlling the assignment of children

from a local level. Subsequent thereto, the State has adopted

a present pupil assignment plan which takes away from the

locality any duty or any responsibility. You say that is not—

M r. N a brit : N o, sir. I would say that law which you

have just mentioned that takes away the duty was in effect

when all of these cases were considered at the trial level and

at the appellate level. As I have tried to explain yesterday,

the Norfolk case, Judge Hoffman disregarded the Pupil

Placement record but in the Northern Virginia case, Judge

Bryan disregarded Pupil Placement for another reason,

which we urged here, which is the lack of adequate adminis

trative remedy under Pupil Placement. But in both of those

cases, the trial judges were sustained.

App. 11

T h e Court : Judge Bryan did what you said he did. Why

is the Pupil Placement Board in existence ?

M r. N abrit : In existence ?

T he Court: Yes.

M r. N abrit : I think they have—

T he Court: I understood you to tell me that Judge

Bryan ruled the complexity or the cumbersomeness of the

procedures followed by Pupil Placement Board were so

ornate that nobody paid any attention to it. Now, if that is

so—

M r. N abrit : I don’t know if Your Honor had an oppor

tunity to look at the opinion I referred to. but I have it right

here.

T he Court: I will read that opinion very carefully and

get the whole record and talk to Judge Bryan about it. He

is the Chief Judge in my district. So I will understand

exactly what Judge Bryan ruled before I decide on this case.

But, if one moment you tell me that we don’t pay any atten

tion to Pupil Placement Board because their procedure is too

complex and, therefore, you do not have to comply with it,

and if that is true, then I ought to determine that question.

But we are wasting a lot of time in finding out what they

did, what they don’t do. I cannot do both.

M r. N abrit : No, sir. I submit the two inquiries are not

mutually inconsistent. The first inquiry, on a legal basis,

is whether the State Pupil Placement Board has, under the

statute, provided a reasonable administrative remedy; that

is, a prerequisite to Plaintiff’s coming into court and asking

for relief of any nature. The second question would be

whether, in the circumstances shown of the actual practices

and procedures used, the Pupil Placement Board is using

some or any procedures which are constitutionally permissi

App. 12

ble; and what Judge Bryan did hold that he invited them to

come into the case, if they wanted to contest it and they

never accepted the invitation. And when you read the Harm

Case, you don’t see any discussion of this, because those

rules of Judge Bryan were not entirely argued on the appeal

by the State. They didn’t even appeal them. This opinion

that I keep referring to is the opinion Judge Bryan wrote

in the mandate, came back from the Harm Case, dated June

3, 1959.

T he Court: Well, if I should rule in this case that it

wasn’t necessary to file an application with the Pupil Place

ment Board, wouldn’t I have to rule that somebody else had

to do it ? Somebody has got to assign these children.

M r. N abrit : That is correct, sir. Judge Bryan’s view

was that perhaps you had to file a Pupil Placement form

which we have done. We did it under protest. We filed the

form. And we have been in the position of being ready to

furnish any school authority any information he wanted,

as far as his parents were concerned. Mr. Lawson wrote a

letter and said, “We are going to cooperate. What do you

want us to do ?” But we do insist that we are not required

to conform to these various rules and regulations.

T he Court : Any rules applied by whom ?

Mr. N a brit : I don’t think the Pupil Placement Board

applies any. It is the local authority.

T he Court: Y ou said you don’t have to—such as the

60-day rule or such provision as this protest appeal. Those

are the two principal things.

You say that you don’t have to do that. And, if you are

right, then you must have to comply with the rules that some

body makes. Now, whose rules are you going to comply

with on the assignment? You have to comply with some

App. 13

body. Certainly, the student couldn’t just go to any school

he wanted to, white or colored; if you did that, you would

have chaos.

M r. N a brit : I never suggested such.

T he Court : You tell us what you have to comply with.

M r . N a brit : Pertaining to what ?

T h e Court : What ?

M r . N a brit : P ertain ing to request for transfer.

T h e Court : Pertaining to your right to at least 29 chil

dren who go to school that they wanted to go to. Now, what

do you comply with ?

Mr. N a br it : I will try to state it as best I can. I would

say that these pupils have to abide and submit to all pro

cedures. It may be measured by all qualifications and stand

ards. It may be judged by all criteria. You will have to

submit to any type of rules or regulations or procedures

that applied to all students on initial assignment and all stu

dents on transfers.

T h e Court : By whom ?

M r. N a brit : By whomever established the particular

rule in question.

T he Court: Y ou certainly lost me. I understood you

to say that you don’t have to comply with the Pupil Place

ment Board’s procedure because—for various reasons. Now,

if you don’t have to follow what they laid down, you either

have to follow what the local school board lays down or

what somebody lays down. There must be rules for the

organization of anything, including a baseball game. You

couldn’t even play baseball without rules.

M r. N a b r it : Certainly wouldn’t be any question. For

App. 14

example, these Plaintiffs are bound by that statute that they

have to be six years old to go to school.

T he Court : By what right do they claim they go to the

school that they want to and w 1k > is the judge of whether

they can or cannot go to the school ? I mean, I have before

me the request of 30 pupils.

M r. N a brit : Twenty-eight.

T he Court: —who want to go to a specific school. Now,

the Roanoke City people say, “I didn’t send them to that

school and I didn’t deny them the right for them to go to

that school. I have no authority. I referred their applica

tions to a State body.” The State body said they heard it.

And 28 of those students—what they considered to be good,

valid reasons, they were improper transfers. Aren’t we lim

ited to the question of whether the reasons that they said

were valid or whether they are false because, if they are false

and if their only reason for not transferring these children

was on account of race, I will certainly upset it.

M r. N abrit : Yes, sir, I understand that. But this doesn’t

at all exclude the other question. That is, what are the gen

eral assignment procedures used in the Roanoke system by

either the local authorities and/or ratified by the Pupil Place

ment Board by acquiescence, such as the feeder system or

initiated by the Pupil Placement Board by themselves. What

are the procedures which contribute ?

T he Court: Didn’t the Defendants stipulate that the

procedure being followed in the Roanoke schools, that is it ?

Mr. N a brit : Yes, sir.

T he Court: That is the procedure that everybody is

being assigned in Roanoke.

M r. N a brit : My only point before the Court is a ques

App. 15

tion as to what relief it shall grant to insure the systematic

elimination of these various facets of segregation that still

exist, that are still applied by perpetuating segregation?

That is it. And the Court can also determine on what basis

they shall be eliminated as to the parties in time schedule,

on the second Brown Case.

T he Court : Are you not then attacking the procedure

that is in effect in Roanoke as being unconstitutional or

invalid.

M r. N abrit : I think that these Plaintiffs in the class they

represent are being denied the rights under the equal protec

tion clause by this present arrangement.

T he Court : All right.

M r. N abrit : But this question of a three-judge court,

that certainly doesn’t come in.

T he Court: N ow, I want you to produce evidence—

show me that the procedure they have used in this case, in

the case of these petitioners, is in any degree different than

the procedure they used for the transfer of all other students

in Roanoke City, both white and colored. Now, if they have

two standards, one for the colored and one for the white,

then the 14th Amendment is violated. But I want you to

produce evidence to show me that they have two systems.

M r. N abrit : The 4th Circuit proves something else and

establishes the same point in the Jones Case. That is what

the Court said. This is in 27B Fed. Section on page 77.

T h e Court : I take it that you are not in a position in

this case to prove that the procedure, whatever it is which

we have agreed upon, is different in the case of white trans

ferred students than it is in the case of colored. You are

going to use another method ?

App. 16

M r. N a brit : What I am prepared to prove—that any

white transferred students, they are certainly in a different

position than the Negro-transferred students. I mean, we

know for a fact that nobody here went through this. Cer

tainly, it is clear in the deposition. And we haven’t heard it

today. Nobody else went through this and subjected to this

kind of screening or screening of this kind of personal pres

entation to the State Pupil Placement Board, this kind of

examination. So, we know that. But even if they were, I

would still have this other information.

T he Court: I say, you show me the evidence. That is

what I want to hear—they put the colored children in an

entirely different type of test than they put the white children

that the}' want to transfer.

M r. N abrit : They made a separate evaluation of these

people and, therefore, used the results which they have for

everybody in a different way.

T he Court: Where is that evidence before the Court?

That is what I would like to get.

M r. N abrit : I will try to produce that. At least I hope

this discussion has clarified what I am trying to do.

T he Court : You present this afternoon any and all evi

dence, positive evidence that you have, as to any different

procedure being used by the State Pupil Placement Board

in passing upon the transfer of white or other children as

distinguished from the specific procedure used in the trans

fer of these children. And, if you show me a difference, I

want to hear it by evidence and not by argument. And I

want to know the reasons, either through your evidence or

through somebody’s evidence, as to why these children were

turned down, so that I can evaluate whether it was on the

App. 17

ground of race or not. That is all I want to hear and no

more.

I will recess for lunch, until 2:15.

(Whereupon the luncheon recess was taken.)

(The hearing was resumed at 2:15 o’clock p.m., with the

same appearances as at the morning session.)

^ 5jC

Testimony of B. S. Hilton

DIRECT EXAMINATION

[TR. P. 105]

Q Now, since you have been executive secretary, did

your Board ever take—-strike that.

M r. N a brit : Your Honor, I was about to ask a ques

tion on the matter we have stipulated on, I believe. I don’t

recall whether our stipulation with reference to the policy

included about not having a desegregation plan, did that

include both the Pupil Placement Board and the local board ?

Does Counsel recall ?

T he Court : I will ask him. He wants to know if you

will stipulate that the State Pupil Placement Board does not

have a fixed plan for desegregating?

Mr. P a r h a m : The Commonwealth has a plan of not

segregating on account of race, creed and color. I will

stipulate that.

T he Court: D o you stipulate that they have made no

plans to desegregate all of the schools in the State of Vir

ginia ?

M r. Scott: I will stipulate that the Pupil Placement

Board has no plans other than the fact that they will not

App. 18

discriminate replacement transfers on the grounds of race,

creed or color; no plan other than that.

T he Court: What is the specific stipulation that you

want to ask that they will make ?

M r. Scott : I will stipulate that, sir.

* * *

Testimony of Dr. James A. Baytoix

DIRECT EXAMINATION

[TR. PP. 124-129]

T he Court: Let me ask you this question, and then I

will let Mr. Nabrit continue. Could you take these children,

who are designated on these sheets here, and given the time,

could you give them tests from a scientific standpoint and,

as a result of those tests, determine whether the findings on

these sheets are correct or incorrect ?

T he W it n e s s : Could I personally do that?

T he Court: Yes, sir, as a Ph. D. psychologist, can you?

T he WTtness : Yes, I personally could do that. But there

are other clinical psychologists that could, too, plenty.

T he Court : And they could tell whether that is a correct

finding or not; isn’t that right ?

T he W it n e ss : Yes.

T pie Court : Now, if you had the burden of showing that

this is an incorrect finding, wouldn’t the best way to do it

be to take at least one or two of these statements and come

up with some scientific finding so the Court would know

which is the correct situation ?

T he W it n e ss : Yes, sir. I don’t know—I would say this:

App. 19

If the Court is going to consider such a statement as this

child’s behavior as not well adjusted, I would ask that it

consider it on the basis of the competency of the person who

made the statement.

T h e Court: Now, I ask you if you had the burden of

advising the Court if the information pertaining to this

child, which we will call one, from top to bottom, was correct

or incorrect, could you do it by professional, scientific exam

ination of the child ?

T he W it n e s s : It seems to me that the person making

the claim has the burden on them to demonstrate this.

T he Court: I am not asking you what the burden is.

The physical examination or scientific examination would

bring a better result than this would bring ?

T he W it n e ss : Yes.

T h e Court : Can you tell by examining these forms, all

of them, whether or not any of this information is correct

or incorrect?

T he W it n e ss : No, sir. I cannot.

T he Court : So it doesn’t make any difference how many

you would examine, you couldn’t tell whether they are cor

rect or incorrect?

T h e W it n e ss : I have never seen these. I am going by

the record.

T he Court: Y ou don’t know if the record is correct on

this child or not?

T he W it n e ss : No, sir.

T he Court : You have no reason to know that it is in

correct ?

T h e W itness : No, I have no reason to know it is incor

rect. I raise the question about the competency of the person.

App. 20

By M r. N a brit :

Q Is it your statement that no trained person can tell

from that information about the child, about whether it is

correct or incorrect?

A I don’t know how a trained person can say this state

ment is correct or not; just take this without seeing the child

and say this is correct.

T he Court : However, the people who made this not only

have seen the child, they have been teaching him for a good

many years. They may not be a psychologist, but they have

been supervising the education of this particular child for

X number of years. And, based upon their records contained

over the years, they came up with certain factual informa

tion which they say is correct. Now, I am asking you, can

you take that same information and tell the Court whether

it is not correct?

T he W itness : Could I make an analogy on this ?

T he Court: Yes.

T he W it n e ss : Let us say that the record here had

health, sex and the teacher had written down here something

like headaches and high blood pressure. That is a statement

for me to make my point. Now, the statement of headaches

tied in with blood pressure, that is the kind of diagnostic

statement that only a licensed physician, it seems to me,

would make; neither matter has a legal point, as made by a

licensed physician.

T he Court: Y ou don’t mean, Doctor, that an MD can

tell me any better whether I have a headache than you can?

T he W it n e ss : I am not—I will try to establish—

T he Court: Well, a headache is subjective. It relies on

what I can tell him.

App. 21

T he W itness : Well, when it gets down to the cause of

the headache—

T h e Court: He doesn’t know if I have it unless I tell

him, does he?

T he Court: I am trying to establish professional com

petency, sir.

By M r . N a brit :

Q Can you explain further what you were trying to say

about high blood pressure ? That was the clinical term that

you were addressing yourself to.

A I was trying to establish that this might be in the

record. But if this becomes a matter of legalism, whether

or not this person has this condition, it would be certainly

established by competent medical authority. The medical

authority might so that the teacher was right. But to make

an action to that individual, taking a health statement that

wasn’t established by a medically competent person, I don’t

see how they can do that.

T h e Court: You don’t mean the health record in the

school, that is compiled by the school officials, including

dental condition and so forth. I mean, they keep regular

records and they are not done by a doctor. Everybody is not

a doctor in the school. You don’t tell me they have no value?

T he W it n e s s : I don’t say they have no value, but I am

raising this point. Suppose by some stretch of the imagina

tion a legal matter developed because of this medical diffi

culty. I am trying to say that I believe that at that level

whether or not in fact this medical difficulty, which is cited

on the record, exists would have to be done by a medically

competent professional. That is the only issue I am trying

to bring.

App. 22

T he Court: If you have a burden to show that it was

incorrect, then you would want to get that professional

advice ?

T he W it n e s s : Yes, sir.

T he Court : I would like to hear the professional advice

myself. That is what I am here to listen to, any advice,

professional or otherwise, to show me that these evaluations

are wrong. That is what I want to hear.

M r. N a rb it : Your Honor, I don’t presume to object to

the Court’s questions, but did I understand the Court to

state, the Court’s view, that Plaintiff has the burden of

establishing the mental health of these Plaintiffs ?

T he Court: No. I said the Court is of the opinion that

the Plaintiff has the burden of showing that these transfers

were withheld on the ground of race. The burden is on you

in this case.

M r. N abrit : It would certainly seem— perhaps I should

continue with the evidence and argue later.

* =1= *

Testimony of Dorothy L. Gibney

DIRECT EXAMINATION

[TR. PP. 191-192]

T he Court: The Court deems it necessary in determi

nation of this case, of course, it will have to go through each

one of these itself. Of course, I think, Mr. Nabrit, it would

be more informative to ask these questions of the Pupil

Placement Board rather than this witness. This witness

merely says this is factual information she gave to the Board.

Now, the Board reached the conclusion and if you give them

this material it would be more informative to the Court to

App. 23

ask the Board. I mean these specific questions as to why they

did or did not do something instead of asking this witness

because she didn’t do anything other than furnish statistical

information. She said she made no recommendation.

M r. Na brit : Yes, sir.

T h e Court : So, it would be more helpful to the Court

if you want to put it in, specifically if you want to find out

specific reasons why a child, for example, was denied admis

sion, that you adduce that information from the ones whose

responsibility it was to assign her.

M r. Nabrit : Let me question this witness about this

pupil number 9 before I release her, Your Honor. I think

this is a factual situation we have here.

T he Court: I don’t want to cut you off. Everything

that is on here in substance was available to the Pupil Place

ment Board. And this information plus what else they had

was the basis of their judgment. So, they are the ones to

ask and question, question the validity of their judgment,

not this witness. Frankly, if she had the responsibility of

assigning on this factual information she may or may not

have come up with a different conclusion than the Pupil

Placement Board did. But, so what if she did? Theirs was

the ones that counts.

Mr. N a brit : I am trying to get an interpretation of

Court Exhibit No. 1.

T he Court: You may ask her. Go ahead.

By Mr. N abrit :

Q Referring to pupil number 14 and 20, I believe—

A May I see their names ? Numbers are so blurred here.

* * *

App. 24

Testimony of Ernest J. Oglesby

CROSS-EXAMINATION

[t r . p p . 227-230]

Q Can you give me an illustration of each. Before—

how many of those have you had?

A I am not sure, sir. We have had several involving

whites. But, may I give you the illustration that I remember

best, which was the case of the 39 white people in Waynes

boro who protested the action of our Board in giving them

the school that they had been assigned to by the local

Waynesboro people?

M r. N a brit : Your Honor, the objection—testimony

along that line is totally irrelevant and immaterial and no

bearing on the case.

T h e Court : Objection overruled.

T he W it n e ss : A group of citizens from Waynesboro

came to our Board and protested and they were within the

limit of their IS days and made a formal protest. We ad

vertised as quickly as we could, following the law as to the

minimum amount of time that we had to allow between the

protest—

By M r. Scott :

Q What was the result of that ?

A The result in this case was that we went to Waynes

boro and had an all-day meeting and granted the petitions

of these 39 people.

Q In other words, you reversed ?

A We reversed ourselves.

Q And the other case, what was the history of that, or

do you recall ?

A The case in Richmond was one where we had made

App.25

a decision based entirely upon distance. The protesting par

ents came before us and asked us why we had made the

decision we had. And we told them it was made purely on

distance. And they put in evidence which indicated that we

had been wrong in our decision with respect to distance. We

had conflicting evidence. So, we arranged to have a surveyor

measure the actual distance so we would know. We found

out that the parents were wrong; that the evidence we had

gone before us was correct and we did not reverse our deci

sion based upon the surveyor’s evidence. May I give you

the time element on that ?

A Wait a second. What is your policy with regard to

hearing protests as to whether they are in Richmond or in

the community of the protestants ?

M r. N abrit : Your Honor, may we have an understand

ing that I continue my objection through this entire line of

questioning ?

T h e Court : Yes. You are making an objection and it is

overruled. Objection is overruled. Go ahead.

By M r. S cott :

0 Do you understand the question ?

A I think I do, sir. It has been our policy and it is our

present intention to go to the community where the protest

is made if the number is sufficient to justify that, to have the

hearing there because we feel we can find out more right on

the ground where the situation takes place than we can in

Richmond, and also it would be much simplier for this Board

to make that trip than have the parents and children involved.

One of the principal reasons we hope in the future to go to

the home of the parents because we feel that we are going to

be able to get an awfully lot more information when we

actually have the parent and children involved in before

the Board for them to tell us the story than for us to have

App. 26

it decided on technical and the evidence that we get from the

lawyers involved in it. We would like to know as much as

we can.

Q In these protests that you have heard, has a court

reporter been there, taking down everything?

A Yes, sir.

Q What has been the time element, your best recollec

tion, consumed in these protests that you have had ?

A The very minimum that the law allowed us to per

form, there are certain restrictions how long we have got

to advertise and how long we have to wait. We did it as

quickly as possible, though by law we have—allowed 30 days

from our decision. We made the decision in Waynesboro in

four days and we made the decision in Richmond in 15 days.

The 15 days—we took about all of that time to get the survey

figures in and call them in.

Q So, in those cases from the time the protest was filed

until your findings in the individual cases and your conclu

sions of fact were filed, roughly speaking, how long did it

take?

A Less than three weeks, I think. It would be a little

more in the Richmond case because we had to allow certain

time for the figures in that case. About 15 between the

protest filed and the time we had the hearing, 15 days for

the Board to make a decision.

Q In general, what, in individual cases, is your policy so

far as pupils are concerned and insofar as over-all education

is concerned ?

M r. N abrit : Now, I couldn’t hear.

Q What is your policy, over-all, in connection with pu

pils and over-all—education ?

App. 27

A We believe we exist for the purpose of doing the best

we can for the over-all education of the people of Virginia as

well as for the protection of the civil rights and so on of

those children involved in the protest.

* *

Testimony of B. S. Hilton (Recalled)

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

[tr. p p . 285-288]

Q Have you on the administrative side of the staff ever

made any routine inquiries as to the local practices on such

things as overlapping school zones, feeder systems ?

T he Court: I am only going to sustain the objection

because the Board itself said it did not and it wasn t inter

ested in the local school setup. And what he did administra

tively is immaterial. The Board’s policy is what governs

and they are bound by their own policy. And they say that

they do not have that information and did not seek it. What

difference does it make ?

M r. N abrit : I withdraw that question, sir.

* *

M r. N abrit : I have no further questions, Your Honor.

M r. Scott : I have none.

M r. P arham : No questions.

Mr. M cI l w a in e : No questions.

T he Court : Step down.

(The witness withdrew from the witness stand.)

T h e Court : Call your next witness.

M r. N abrit : Miss Gibney, please.

App. 28

Testimony of Dorothy L. Gibney (Recalled)

REDIRECT EXAMINATION

By M r. N abrit :

Q Miss Gibney, this piece of—this large piece of graph

paper with the information on it and the—part of Court

Exhibit 2, can you tell me who prepared this ?

A Yes. This is Mr. A. B. Camper’s handwriting.

Q And do you recall that this was exhibited to the Place

ment Board at that meeting or what—

T he Court : The Court already—it was there available

for them. It was before the Pupil Placement Board.

M r. Na br it : I am trying to find out whether it was in

the room. I acknowledge previous testimony it was in the

room. I—

T he Court : The Court understands that all of this in

formation was not only in the room but it was examined or

that portion thereof that they wanted to examine and it

was all available for their use. They asked for it and that

is what they got.

By M r. N abrit :

Q Is that your understanding ?

T he Court : Regardless of whether it is her understand

ing, it is the Court’s understanding. Objection sustained.

Maybe you don’t want to accept it as a fact.

By Mr. N abrit :

Q Miss Gibney, were the accumulative folders of the

students exhibited to the Placement Board. Is that your

same ruling?

T he Court : I don’t understand you. It is perfectly clear

the Court has accepted in evidence that information that it

App.29

obtained under Court Exhibit No. 2 as being all statistical

data furnished by the school board of Roanoke at the request

of the State Pupil Placement Board and it was all before

them and was used by them along with other information

that they got orally in reaching the conclusions that they

reached in these individual cases. I don’t know how you can

establish that fact any better. Because, regardless of what

this witness says, that is a fact.

By M r. N abrit :

O Was this information before the Pupil Placement

Board for any longer—

T he Court: Objection sustained. Next question.

M r. N a brit : No further questions.

T he Court : Step down.

(The witness withdrew from the witness stand.)

T h e Court : Call your next witness.

M r. N abrit : May it please the Court, we have no further

witnesses to present. We have agreed to stipulations of Mr.

Parham which I wrote out in my handwriting.

M r. P arham : I will be delighted if you will read it. It is

your handwriting.

T he Court : Read the stipulations.

M r. N abrit : First stipulation was that the current school

year ends June 9, 1961.

Second stipulation was that none of the infants’ parents

or guardians filed protests with the Pupil Placement Board

after the August 15th, 1960, decision.

T he Court : So stipulated by all parties to this suit. And,

if there is no objection, the stipulations shall be made a part

of the record.

* * *

Printed Letterpress by

L E W I S P R I N T I N G C O M P A N Y • R I C H M O N D , V I R G I N I A