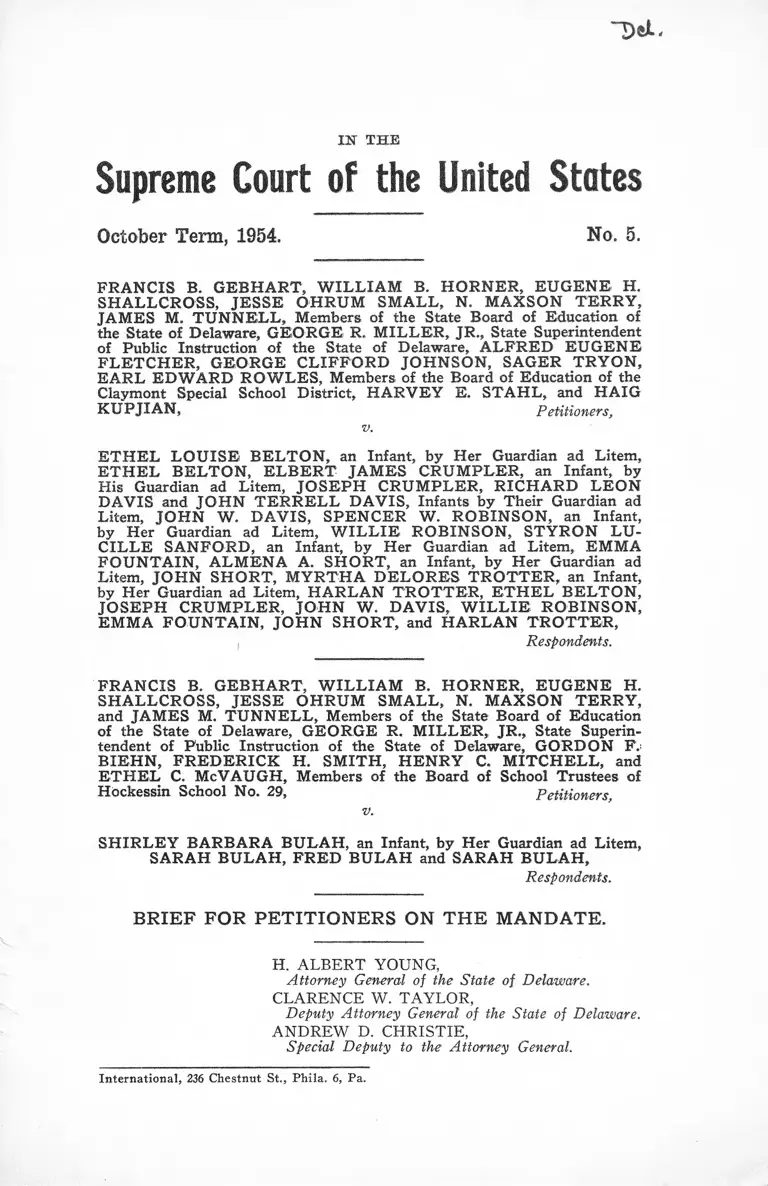

Gebhart v. Belton Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gebhart v. Belton Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate, 1954. 5e910ef2-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2ac8ab51-c027-4b9f-a1f5-a85a10e04f80/gebhart-v-belton-brief-for-petitioners-on-the-mandate. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

"Del.

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1954. No. 5.

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, WILLIAM B. HORNER, EUGENE H.

SHALLCROSS, JESSE OHRUM SMALL, N. MAXSON TERRY,

JAMES M. TUNNELL, Members of the State Board of Education of

the State of Delaware, GEORGE R. MILLER, JR., State Superintendent

of Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, ALFRED EUGENE

FLETCHER, GEORGE CLIFFORD JOHNSON, SAGER TRYON,

EARL EDWARD ROWLES, Members of the Board of Education of the

Claymont Special School District, HARVEY E. STAHL, and HAIG

KUPJIAN, Petitioners,

v.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem,

ETHEL BELTON, ELBERT JAMES CRUMPLER, an Infant, by

His Guardian ad Litem, JOSEPH CRUMPLER, RICHARD LEON

DAVIS and JOHN TERRELL DAVIS, Infants by Their Guardian ad

Litem, JOHN W. DAVIS, SPENCER W. ROBINSON, an Infant,

by Her Guardian ad Litem, WILLIE ROBINSON, STYRON LU

CILLE SANFORD, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem, EMMA

FOUNTAIN, ALMENA A. SHORT, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad

Litem, JOHN SHORT, MYRTHA DELORES TROTTER, an Infant,

by Her Guardian ad Litem, HARLAN TROTTER, ETHEL BELTON,

JOSEPH CRUMPLER, JOHN W. DAVIS, WILLIE ROBINSON,

EMMA FOUNTAIN, JOHN SHORT, and HARLAN TROTTER,

Respondents.

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, WILLIAM B. HORNER, EUGENE H.

SHALLCROSS, JESSE OHRUM SMALL, N. MAXSON TERRY,

and JAMES M, TUNNELL, Members of the State Board of Education

of the State of Delaware, GEORGE R. MILLER, JR., State Superin

tendent of Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, GORDON F.‘

BIEHN, FREDERICK H. SMITH, HENRY C. MITCHELL, and

ETHEL C. McVAUGH, Members of the Board of School Trustees of

Hockessin School No. 29, Petitioners,

v.

SHIRLEY BARBARA BULAH, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem,

SARAH BULAH, FRED BULAH and SARAH BULAH,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS ON THE MANDATE.

H. ALBERT YOUNG,

Attorney General of the State of Delaware.

CLARENCE W. TAYLOR,

Deputy Attorney General of the State of Delaware.

ANDREW D. CHRISTIE,

Special Deputy to the Attorney General.

International, 236 Chestnut St., Phila. 6, Pa.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Status o f the Cases ................................................................. 2

Prelim inary ................................................................................. 3

Factual Background in Delaware ...................................... 4

I. School System as It Existed Prior to the Decision in

This Case ....................................................................... 4

(A) Legal B a s is ............................... 4

(B) State Board of Education.................................... 5

(C) Local School Districts for White Children . . . . 5

(D) Local School Districts for Colored Children . . . 7

(E) School Finances ................................................... 9

II. Desegregation to D a te ................................................... 10

(A) Progress ............................................................... 10

(B) Opposition.................................................... 12

(C) Summary of Delaware’s Situation............ 16

Argument—Form o f Mandate ............................................... 17

I. The Decree of the Court of Chancery, as Affirmed by

the Supreme Court of the State of Delaware, Should

Be Affirmed ................................................................... 17

II. Recommendation With Respect to the M andate.......... 18

(A) Introduction ........................................... , ........... 18

(B) This Court May and Should Permit a Gradual

Adjustment From Segregated Public Education

to a System Without Race Distinction............. 19

(C) This Court Should Remand the Cases to the

Lower Courts for Formulation of Decrees for

the Admittance of Plaintiffs to Public Schools

Without Regard to Race as Soon as Practicable

Within a Time Limit to Be Set by This Court 24

Conclusion ....................... 28

Page

CASES CITED.

Ballard v. Searls, 130 U. S. 50, 9 S. Ct. 418, 32 L. ed. 846 .. 25

Briggs v. Elliott, 98 Fed. Supp. 529 ......................................... 20

Briggs v. Eliott, 103 Fed. Supp. 920 ........................................... 19

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 98 Fed. Supp. 797 . . . 19

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483, 98 L.

ed. (Advance p. 583), 74 S. Ct. 686 ................................... 3, 17

Burr v. Board of School Commissioners of the City of Balti

more (Oral opinion Judge James K. Cullen, October 5,

1954, in the Superior Court of Baltimore City, Docket

1954, Folio 830) ................................................................... 11

Caretti v. Broring Building Co., (Md. Ct. App. 1926) 150

Md. 198, 132 A. 619, 46 ALR 1 .......................................... 21

Davis v. County School Board, 103 Fed. Supp. 337 ................ 20

Eccles v. Peoples Bank of Lakewood Village, 333 U. S. 426,

431, 92 L. ed. 784, 68 S. Ct. 641, 644 ............................... .. 20

Fischer v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147, 68 S. Ct. 389, 92 L. ed. 604 .. 23

Gebhart v. Belton, — Del. Ch. —, 91 A. 2d 137 ....................2, 17, 19

Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206 U. S. 230, 51 L. ed. 1038,

27 S. Ct. 618; 237 U. S. 474, 59 L. ed. 1054, 35 S. Ct.

631; 237 U. S. 678, 59 L. ed. 1173, 35 S. Ct. 752; 240

U. S. 650, 60 L. ed. 846, 36 S. Ct. 465 ............................... 21, 27

Hecht Co v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321, 88 L. ed. 754, 64 S. Ct. 587 20

Hughson v. Wingham, (Wash. S. Ct. 1922) 120 Wash. 327,

207 P. 2, 27 ALR 327 ........................................................... 21

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education,

339 U. S. 637, 70 S. Ct. 851, 94 L. ed. 1149 ....................23, 26

Mercoid Corp. v. Mid-Continent Investment Co., 320 U. S.

661, 88 L. ed. 376, 64 S. Ct. 268 ......................................... 21

Northern Securities Co. v. United States, 193 U. S. 197, 3624

S. Ct. 436 ............................................................................... 20

New Jersey v. New York, 283 U. S. 473, 75 L. ed. 1176, 51

Sup. Ct. 519; 284 U. S. 585, 75 L. ed. 506, 52 S. Ct. 120;

296 U. S. 259, 80 L. ed. 214, 56 S. Ct. 188 ......................22, 27

Panama Mail S. S. Co. v. Vargas, 281 U. S. 670, 50 S. Ct.

448, 74 L. ed. 1105 ........................................................... 25

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 41 L. ed. 256, 16 S. Ct. 1138 19

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U. S. 395, 90 L. ed. 1332,

66 Supp. Ct. 1086

Page

21

CASES CITED (Continued).

Rogers v. The St. Charles, 19 How. (U. S.) 108, IS L. ed. 563 25

Russell v. Southard, 12 How. (U. S.) 139, 13 L. ed 927 .......... 25

Securities and Exchange Comm. v. U. S. Realty and Improve

ment Co., 310 U. S. 434, 84 L. ed. 1293, 60 S. Ct., 1044 . . . 21

Lillian Simmons v. Edmund F. Steiner, et al., Del. Ch. ,

2 A. 2d ............................................................................14,15

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, 332

U. S. 631, 68 S. Ct. 299, 92 L. ed. 247 (Law School) .. .23,25

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U. S. 1, 31 S. Ct. 502,

55 L. ed. 619 .........................................................................22,27

State v. Hutchins, (N. H. S. Ct. 1919) 79 N. H. 132, 105 A.

519, 2 LAR 1685 ................................................................. 21

State of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 59

S. Ct. 232, 83 L. ed. 208 ..................................................... 23

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 70 S. Ct. 848, 94 L. ed. 1114

(University of Texas Law School) ..................................... 23, 25

United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U. S. 106, 31 S. Ct.

632, 55 L. ed. 663 ........................................................... 22, 25, 27

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U. S. 319, 67 S. Ct.

1634, 91 L. ed. 2077 ............................................................. 22,27

United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U. S. 131, 92

L. ed. 1260 .............................................................................22,27

Universal Battery Co. v. United States, 281 U. S. 580, 50 S. Ct.

422, 74 L. ed. 1051 ............................................................... 25

Virginian Railway Co. v. System Federation No. 40, 300 U. S.

515, 552, 81 L. ed. 789, 57 S. Ct. 592, 601 .......................... 21

Page

AUTHORITIES CITED.

Page

46 ALR pp. 35-37 ................................... ................................... 21

The Book of States 1954-1955, Frank Smothers, Editor, The

Council of State Governments (1953), p. 245 .................... 9

Opinion of John M. Dalton, Attorney General of Missouri,

June 30, 1954 ......................................................................... 11

Robert C. Stewart, A Proposed Plan for the Reorganization

of Administrative Units in the State of Delaware (1948)

(an unpublished study) ....................................................... 4, 7

CONSTITUTIONS AND STATUTES CITED.

Page

14 Delaware Code (1953) ......................................................... 4

14 Delaware Code, Chapter 1 (1953) ....................................... 5

14 Delaware Code, Chapters 3, 5, 7 and 9 (1 9 5 3 )...................... 6

14 Delaware Code, Chapter 11 (1953)

14 Delaware Code, Chapter 13 (1953) .

14 Delaware Code, Chapter 17 (1953) ..

14 Delaware Code, Chapter 29 (1953) .

14 Delaware Code, Section 141 (1953)

Delaware Constitution of 1897, Article II, Section 19

Delaware Constitution of 1897, Article X, Section 1 ..

Delaware Constitution of 1897, Article X, Section 2 ..

32 Delaware Laws, Ch. 160 (1921) ..........................

49 Delaware Laws, Chapter 217 at page 386 ..............

49 Delaware Laws, Chapter 337 (1953) ..................................... 10

Revised Code of Delaware, 1852, Chapter 4 2 ............................ 5

I K T H E

Supreme Court of the United States.

October T erm , 1954. No. 5.

Francis B. Gebhart, William B. Horner, Eugene H. Shall-

cross, Jesse Olirum Small, N. Maxson Terry, James M.

Tunnell, Members of the State Board of Education of

the State of Delaware, George R. Miller, Jr., State

Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of

Delaware, Alfred Eugene Fletcher, George Clifford

Johnson, Sager Tryon, Earl Edward Rowles, Members

of the Board of Education of the Claymont Special

School District, Harvey E, Stahl, and Haig Kupjian,

Petitioners,

v.

Ethel Louise Belton, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem,

Ethel Belton, Elbert James Crumpler, an Infant, by

His Guardian ad Litem, Joseph Crumpler, Richard

Leon Davis and John Terrell Davis, Infants by Their

Guardian ad Litem, John W. Davis, Spencer W. Robin

son, an Infant, by His guardian ad Litem, Willie

Robinson, Styron Lucille Sanford, an Infant, by Her

Guardian ad Litem, Emma Fountain, Almena A. Short,

an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem, John Short,

Myrtha Delores Trotter, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad

Litem, Harlan Trotter, Ethel Belton, Joseph Crumpler,

John W. Davis, Willie Robinson, Emma Fountain, John

Short, and Harlan Trotter,

Respondents.

Francis B. Gebhart, William B. Horner, Eugene H. Shall-

cross, Jesse Ohrum Small, N. Maxson Terry, and James

M. Tunnell, Members of the State Board of Education

of the State of Delaware, George R. Miller, Jr., State

Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of

Delaware, Gordon F. Biehn, Frederick H. Smith, Henry

C. Mitchell, and Ethel C. MeVaugh, Members of the

Board of School Trustees of Hockessin School No. 29,

Petitioners,

v.

Shirley Barbara Bulah, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad

Litem, Sarah Bulah, Fred Bulah and Sarah Bulah,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS ON THE MANDATE.

STATUS OF THE CASES.

Petitioners seek review of final judgments of the Su

preme Court of the State of Delaware affirming orders of

the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware. Petition

ers are members of the Board of Education of the State of

Delaware and of the Boards of Education of Olaymont Spe

cial School District and Hockessin School District #29.

The provision from which petitioners seek relief is the same

in both cases and is as follows:

“ That . . . the defendants and each of them,

their agents and employees are enjoined from denying

to infant plaintiffs and others similarly situated, be

cause of color or ancestry, admittance as pupils in the

. . . ” (designated schools).

This Court heard oral argument on December 11, 1952.

Petitioners, pursuant to leave of the Court filed a brief on

December 31, 1952.

On June 8, 1953, this Court ordered the case restored

to the docket and assigned for reargument. The subject

matter of the reargument was directed to the history and

construction of the Fourteenth Amendment and the relief

to be granted.

This Court heard oral argument, and at that time it

was pointed out that the Delaware cases are before this

Court on the narrow issue of the type of relief which should

have been granted. In other words, where there had been

a finding of inequality, does the Fourteenth Amendment

require immediate admission of respondents to schools

maintained for white children!

By its decision of May 17,1954, this Court struck down

the principle of “ separate but equal” educational facilities.

In the Fall of 1952, respondents, in compliance with the

order of the Chancellor, as affirmed by the Supreme Court

of Delaware,1 were granted admission to the respective

2 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

1. Gebhart v. Belton, — Del. Ch. —, 91 A. 2d 137.

white schools. These respondents have remained in those

schools or have completed their education according to that

order. The admission of the negro children to those schools

has taken place without incident. The request to afford the

State a reasonable period of time within which to equalize

the facilities in those two specific districts is no longer

before the Court.

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 3

PRELIMINARY.

This Court by decision of May 17, 1954 disposed of the

constitutional issues involved in the several cases before it.

The Court reserved for further consideration the ques

tion of the type of relief to which the successful parties are

entitled. The parties have been requested to present fur

ther argument on questions previously propounded dealing

with the power and propriety of effecting a gradual adjust

ment to non-segregated public education and the forum best

suited to the administration of such relief.2

This brief is submitted in compliance with the Court’s

request. It is directed to (1) a factual review of the Dela

ware educational system, the experience of this State in

its efforts to effect desegregation since this Court’s decision

of May 17, 1954, the degree of social acceptability or un

acceptability of desegregation in Delaware, and (2) a dis

cussion of the legal precedents and policy considerations by

which this Court should be governed in disposing of the

cases before it.

2. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483, 98

L. ed. (Advance p. 583), 74 S. Ct. 686. Footnote 13. “4. Assuming

it is decided that segregation in public schools violates the Fourteenth

Amendment, “ (a) would a decree necessarily follow providing that,

within the limits set by normal geographic school districting, Negro

children should forthwith be admitted to schools of their choice, or

“ (b) may this Court, in the exercise of its equity powers, permit an

effective gradual adjustment to be brought about from existing segre

gated systems to a system not based on color distinctions? “5. On

the assumption on which question 4 (a) and (b) are based, and

assuming further that this Court will exercise its equity powers to

the end described in question 4 (b), “ (a) should this Court formulate

4 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

FACTUAL BACKGROUND IN DELAWARE.

I. School System as It Existed Prior to the Decision in

This Case.

(A) Legal Basis.

The Constitution of the State of Delaware adopted in

1897, states that “ the General Assembly shall provide for

the establishment and maintenance of a general and efficient

system of free public schools.” 8 The Constitution pro

vides for equitable apportionment of certain appropriations

among the School Districts and further provides “ that in

such apportionment, no distinction shall be made on account

of race or color, and separate schools for white and col

ored children shall be maintained”.* 3 4

Since there is little additional detail in the Constitu

tion, the Delaware education system is governed largely

by statute.5 The present pattern of education stems largely

from the School Code of 19216 which was enacted after

lengthy study. Prior to that date schools were in general

locally run from local funds.7

detailed decrees in these cases; “ (b) if so, what specific issues should

the decrees reach; “ (c) should this Court appoint a special master to

hear evidence with a view to recommending specific terms for such

decrees; “ (d) should this Court remand to the courts of first instance

with directions to frame decrees in these cases, and if so, what gen

eral directions should the decrees of this Court include and what

procedures should the courts of first instance follow in arriving at

the specific terms of more detailed decrees?”

3. Delaware Constitution of 1897, Article X, Section 1.

4. Delaware Constitution of 1897, Article X, Section 2. The

separate requirement also appears at 14 Del. Code, Section 141

(1953).

5. Title 14, Delaware Code (1953).

6. 32 Delaware Laws, Ch. 160 (1921).

7. For a careful legal history of Delaware education see Robert

C. Stewart, A Proposed Plan for the Reorganization of Administra

tive Units in the State of Delaware (1948) an unpublished study.

5

(B) State Board of Education.

The general administration and supervision of the free

public schools in Delaware is vested in the State Board of

Education.8 The Board consists of sis residents appointed

by the Governor from various parts of the State. No one

subject to the authority of the Board may serve thereon,

and the members receive only their expenses and twenty-

five dollars per meeting.

The Board in turn appoints a Superintendent of Pub

lic Instruction who acts as Executive Secretary. The State

Board employs a number of other executive officers, and

administrative assistants. The State Board through its

staff has almost complete charge of several important

phases of the State system such as: education of handi

capped children, student driving training and education

of the handicapped. The Board makes the budget recom

mendations for all public schools to the State Budget Com

mission and to the General Assembly; it also must approve

all capital improvements. But the State Board’s most

important function is the administrative and instructional

supervision which it exercises in varying degrees over all

the schools through its general powers.

(C) Local School Districts for White Children.

The entire State is divided into local districts for the

education of white children and such districts have rather

definite geographical boundaries. The boundary lines for

the original districts were set more than a hundred years

ago.9 Frequent changes were made by statute until 1897

when the present State Constitution was adopted. The Con

stitution now forbids local or special laws relating to the

creation or changing the boundaries of school districts.10

Many consolidations and some changes in boundaries have

8. See generally Chapter 1, Title 14, Delaware Code (1953).

9. See Revised Code of Delaware, 1852, Chapter 42.

10. Delaware Constitution of 1897, Article II, Section 19.

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

taken place under various statutes of general application

although such statutes make changes difficult.11

There remain, however, sixty-three local school dis

tricts in the State for the education of white children.12

Sixteen of the most populated local districts are known

as “ Special School Districts” and in such districts the

local boards exercise a great deal more authority than do

the other local boards in the State. The most important

Special School District comprises the entire city of Wil

mington. The Wilmington schools have always operated

as an almost separate school system although they receive

the same uniform State appropriations as do other schools.

Forty-seven of the local districts are known as ‘ ‘ School

Districts”. Here the local boards act largely on behalf

of the State Board and make fewer individual decisions.

Most of the local districts whether they are School

Districts or Special School Districts, have certain charac

teristics in common. All have a school board made up of

local residents who are responsible for maintaining the

buildings and hiring all personnel for the school involved.

All such boards receive uniform State appropriations and

all are subject to a certain amount of general supervision

from the State Board. In all cases the local board, after

favorable referendum, may levy local taxes to supplement

the funds received from the State. Most of the local boards

are elected by the residents of the district but in most of

the districts in New Castle County, including Wilmington,

the boards are appointed by the resident judge of the Su

perior Court.13

Many of the local districts have no high school and

the State Board arranges for high school education by set

ting up high school attendance areas which sometimes in

clude several local districts. At present the local district

11. 14 Del. Code (1953), Ch. 11.

12. Some of these are now integrated. See “Desegregation to

Date”, infra.

13. 14 Del. Code (1953), Chs. 3, 5, 7 and 9.

6 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 7

operating the high school bears whatever local cost there

is for such high school and the other districts have no ex

pense in connection therewith. In one ease however, a large

high school district was established to serve several local

districts without being operated by the board of any of the

districts served. Those served within the geographic area

of that high school district are subject to local school taxes

for the high school.

Several of the districts serve large and populated areas

with more than one building and with a school superin

tendent as well as principals for each building. Such dis

tricts are in a position to adjust their educational program

to some form of integration with less difficulty than are

the eleven rural districts which still maintain schools with

only one or two teachers.

The State Board has long recognized that greater edu

cational opportunities as well as administrative economies

would result from consolidation of many of the existing

districts. Attempts to obtain local approval of such con

solidations have met with frequent set-backs, and the Gen

eral Assembly has refused to liberalize the statutory re

quirements for consolidation. It is apparent, therefore,

that there is strong local opinion in many parts of the State

against changing the current school arrangements. This

opinion was frequently expressed long before integration

played any part in such discussions.

(D) Local School Districts for Colored Children.

In addition to the sixty-three white districts discussed

above there are forty-two School Districts which operate

schools for colored children. These districts were devel

oped at a later date than the white school districts and with

less definite boundries.14 Some colored districts exist en

tirely within white districts while others include parts of

14. Robert C. Stewart op. cit. p. 28.

two or more districts. Two of the colored high school dis

tricts include entire counties.15 All of the colored schools

operate within the uniform State appropriations and capi

tal outlays are paid without local contributions. There is

no attempt to collect local school taxes from colored resi

dents except in Special School Districts. In other respects

the colored school boards operate exactly as the white

boards and the same statutes govern both. The school

boards, whether they are white or colored, are made up of

respected local citizens, many of whom oppose any change

or consolidation.

The picture is further complicatead by the existence

of several colored schools under the direct jurisdiction of

white Special School Districts. In thirteen instances in

cluding the City of Wilmington, a single board operated

both the white and colored schools of the district. Exhibit 1

lists all of the colored schools of the State and shows the

complicated geographic and administrative relation of

these districts and the white districts.

It is apparent that those Special School Districts which

already operate separate schools for white and colored chil

dren are in the best position to integrate such schools with

a minimum of administrative adjustment. Orderly integra

tion can be more satisfactorily accomplished by reorgani

zation of other school districts in the State. White or

colored districts should cease to exist as such and new dis

tricts should be formed. Such reorganization would nor

mally be a function of the State Legislature. Since the

school laws are largely statutory rather than constitutional,

a simple majority in the General Assembly with approval

by the Governor would be sufficient to make the necessary

changes. However, representation in the General Assem

bly is heavily weighted in favor of the less populated areas

15. The William M. Henry Comprehensive School in Kent

County and the William C. Jason Comprehensive School in Sussex

County.

8 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 9

where consolidation of school districts in general has long

been opposed.

Legislative reorganization of the public school district

ing in this State will permit a more orderly transition to a

non-segregated public education system. However, the

composition of the General Assembly is such that the ma

jority of the members are elected from sections which

are sincerely opposed to integration. Legislation which

will aid in the integration of our public schools will be

met with strong opposition. On the other hand, realization

that integration is to become a reality, whether by court

edict or legislative act, may result in enactment of legisla

tion which will lessen the impact of this Court’s decision

in those areas where the dominant mood is opposed to

integration.

(E) School Finance.

The State pays more than 90% of the operating ex

penses of the Delaware public schools. The balance is paid

by the local school districts through local taxes. No other

state government pays so large a percentage of the cost.16

In the administration of these funds units of children are

the basis of calculation and there is no differentiation based

on color. There is a minimum salary schedule for teachers

and other school personnel and these salaries are paid from

State funds.17 There are uniform State allowances to each

district for all other expenses and such allowances are based

on the number of pupils in attendance.18 Transportation of

pupils is provided at State expense.19

16. The Book of States 1954-1955, Frank Smothers, Editor, The

Council of State Governments (1953), p. 245.

17. 14 Del. Code (1953), Chapter 13.

18. The appropriations are based on “units of pupils” as defined

in the statute. 14 Del Code (1953), Chapter 17.

19. 49 Delaware Laws, Chapter 217 at page 386; 14 Del. Code

(1953), Chapter 29.

The most recent school construction program provides

for improvements costing over $17,000,000, more than

$12,000,000 of which is to he paid from State funds while

local districts contribute about $5,100,000.2° The colored

school districts and many white districts have no local

school taxes at all. Many of the white districts have had to

levy local property taxes to amortize bonds issued to pay

the local share of capital improvements. Some districts

also levy taxes to supplement the State appropriations for

general expenses and salaries.

Any reorganization of school districts will necessarily

involve a rearrangement of the present local school tax pic

ture. Attention must also be given to the bonded indebted

ness of the various districts.

10 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

II. Desegregation to Date.

(A) Progress.

Since the decision of the Court, issued May 17, 1954,

significant progress has been made toward abolishing segre

gation in parts of the Delaware public school system.

Shortly after that decision, the State Board of Education

sought the opinion of the Delaware Attorney G-eneral as to

whether it could immediately set integration machinery in

motion in those districts already prepared for desegrega

tion or whether it was necessary to await the final mandate

of the United States Supreme Court. The opinion of the

Attorney General, dated June 9, 1954, held in effect that

school districts could proceed with integration, in accord

ance with the decision of May 17, 1954 in this case, without

doing violence to the constitution and laws of our own State

and notwithstanding the fact that the mandate of the United 20

20. 49 Delaware Laws (1953), Chapter 337.

States Supreme Court had not yet been handed down.21

(Exhibit 2).

As a result of the Attorney General’s opinion, the

State Board of Education developed and adopted Policy

Statement I, as of July 11, 1954 (Exhibit 3). This granted

permission to the Wilmington school authorities to move

promptly into a partial integration program (See Exhibit

4). It urged that other school authorities together with

interested citizen groups take immediate steps to formulate

integration plans in the various districts and to submit

these plans to the State Board of Education for review.

The Policy Statement brought various phases of the prob

lem to the attention of those concerned and pledged co

operation of the State Board with the local school units.

On August 19, 1954, the State Board of Education

adopted Policy Statement II (Exhibit 5) which concerned

the opening of schools in September, 1954. In this state

ment all schools with four or more teachers were requested

to prepare and present tentative plans for integration in

their area on or before October 1, 1954.

On August 26, 1954, the State Board of Education

adopted Policy Statement III (Exhibit 6). This statement

was designated to assist the local school authorities in their

plans for integration by bringing to their attention various

more specific items and suggestions which should be con

sidered in connection with their plans.

Several school districts promptly submitted plans for

partial or complete integration and the State Board of

Education approved several such plans, effective at the be

ginning of the present school year, 1954-1955. Exhibit 7

shows that in areas containing about 28% of the total

negro school population of the State, integration has been

21. For similar holdings see: Opinion of John M. Dalton, Attor

ney General of Missouri, June 30, 1954; Burr v. Board of School

Commissioners of the City of Baltimore, (Oral opinion, Judge James

K. Cullen, October 5, 1954, in the Superior Court of Baltimore City,

Docket 1954, Folio 830).

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 11

undertaken without incident. It should be observed, how

ever, that most of the integration has been in the northern

part of New Castle County where there is the greatest con

centration of the population of the State. Furthermore

an inspection of the districts involved would reveal that

a comparatively small number of colored children are tak

ing advantage of their right to attend schools which were

formerly all white.

The significant fact is that voluntary steps toward de

segregation have taken place in a number of districts on

a partial basis and that the resultant integration has met

with community acceptance.

(B) Opposition.

In the lower counties of the State the dominant mood

is opposed to integration. Some of the school districts have

made no plans looking toward eventual integration; other

districts merely indicate a willingness to take whatever

steps the court may direct.! In the Laurel school district,

located near the southern border of the State of Delaware,

a public opinion poll conducted with the approval of the

local school board registered 1258 to 31 against desegrega

tion.22 )

At the beginning of the 1954-1955 school year, the Board

of the Milford Special School District admitted ten Negro

children to the tenth grade of the Milford High School.

These pupils continued to attend the high school through

September 17, 1954, a period of nine school days, without

incident. On September 17, there was a mass meeting at

tended by about 1,500 persons who were opposed to the

admission of the Negro children. The school session was

dispensed with on September 20,1954 in order that a special

meeting of the parents of the school children and the mem

bers of the School Board could be held to discuss the prob

22. The poll was held at the white school and only seven negro

residents voted.

12 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

lem of the integration of the Negro children into the white

schools.

A petition was presented to the local School Board re

questing it to rescind its action in admitting the ten Negro

pupils. The Milford School remained closed during the en

tire week beginning September 20th. The Board of the

Milford Special School District resigned on September 23,

1954.

The feeling against the admission of these ten Negro

children in the Milford Special School District continued

to run high. Beginning on September 26, 1954, mass meet

ings were conducted by an organization known as the Na

tional Association for the Advancement of White People.

A major objective of these meetings was the boycotting of

all schools, and the Milford High School in particular, in

order to bring pressure upon the local school authorities

to remove the Negro children from the Milford High School

and to prevent further action in lower Delaware directed

toward integration. The meetings of the National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of White People were de

signed to (1) incite anti-Negro feeling among white peo

ple, (2) inspire a willingness to commit violence in order

to perpetuate segregation, and (3) to advocate violation

of the State School Attendance Laws.

The State Board of Education reopened the Milford

High School on September 27th with the ten colored chil

dren in attendance. On that day, crowds milled around

the school, and some people took names of children that at

tended school. School attendance was only 456 pupils of

1,562 pupils enrolled. A motorcade of cars decorated with

streamers and carrying placards reading ‘ ‘ Send them back

to Africa” and “ Join the NAAWP” passed the school.

Circulars were distributed among the crowds urging boy

cott of the Milford School. On September 29th, attendance

in neighboring school districts dropped to a small fraction

of their enrollment.

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 13

A new Board of the Milford Special School District,

organized September 30th, removed the names of the col

ored students from the rolls of the Milford High School,

thus compelling the Negro pupils to withdraw from the Mil

ford High School and attend a colored school.

The President of the Board of Milford Special School

District stated that:

“ Public demonstrations against the Negro stu

dents attending the white school were of such propor

tions that the schools were closed during the week of

September 20 to September 24 inclusive and were re

opened on September 27 by the State Board of Educa

tion and under its direction and supervision. There

after the public demonstrations increased and threats

of violence were made, because of which school attend

ance dropped to approximately one-third, and the whole

educational program of the Milford Special School Dis

trict was disrupted.

“ On September 30, 1954, the Board of Education

of the Milford Special School District notified all of

said Negro students that their names had been re

moved from the rolls of the Milford High School. This

action by the Milford Board of Education was done

with a view of aiding and restoring law and order to

the school district, in the interest of the educational

program of the school district and for the general wel

fare of the entire student body, and was prompted par

ticularly for the safety of the colored students.” (Affi

davit of Edmund F. Steiner, October 7, 1954); Lillian

Simmons v. Edmund F. Steiner, et al., Del. Ch.

, 2 A. 2d

Suit was immediately filed on behalf of the ten Negro

children in the Delaware Court of Chancery requesting that

the Board of the Milford Special School District be en

joined from denying admission to the Negro children.

14 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 15

The Attorney General appeared as amicus curiae and

urged that the ten Negro pupils had acquired a status as

students in the Milford High School by their admittance

by the Milford School Board, and that a later Board could

not expel them and, further, that the Negro children hav

ing acquired such status could not be expelled because of

threats of violence and unlawful disruption of the public

order.

The Court of Chancery in deciding the issue in the

preliminary steps of the proceeding granted an injunction

preserving the status of the Negro children as pupils in

the Milford High School. Vice-Chancellor William Marvel

stated:

“ Except for their names now being withdrawn

from the records of the school, plaintiffs’ position is

no different than that of other Negro students of Dela

ware now attending partially integrated schools on

the basis of their rights to equal protection under the

Constitution of the United States. It would be un

realistic to maintain that these other students are un

lawfully in school during the present phase of permis

sive integration.

“ I hold that plaintiffs, having been accepted and

enrolled, are entitled to an order protecting their status

as students at Milford High School; that their right

to a personal and present high school education having

vested on their admission, they need not wait for de

crees in the cases decided by the United States Su

preme Court in May as a prerequisite to the relief they

seek.” Lillian Simmons v. Edmund F. Steiner, et al.,

supra.

This case is now on appeal before the Delaware Su

preme Court. By virtue of a stay granted by the Delaware

Supreme Court, the ten Negro children presently attend a

Negro High School located sixteen miles from the Milford

High School.

16

(C) Summary of Delaware’s Situation.

Although Delaware contains only three counties, the

administration of its educational system is a complex mix

ture of centralized administrative and financial authority

and autonomous local control. Partial desegration has pro

gressed satisfactorily in all but one of the districts where

it has been undertaken. In the lower part of the State

there is strong opposition to immediate integration.

In certain areas in Delaware a gradual transition from

a segregated school system to a non-segregated school sys

tem is necessary to insure permanency and community ac

ceptance.

The events at Milford demonstrate that:

1. Public opinion in lower Delaware has been aroused

against desegregation and that a significant percentage of

the people in parts of Delaware are not ready to accept

integration.

2. The immediate admission of Negro children to white

schools under the old “ separate but equal” doctrine is

inconsistent with orderly gradual transition from separate

to integrated schools in areas where such immediate ad

mission is opposed by the local population. The decision

of the Supreme Court of the State of Delaware makes im

mediate admission mandatory where separate facilities are

not equal. Since many instances of unequal facilities may

be presented to the courts for immediate relief under the

“ separate but equal” doctrine, gradual integration depends

upon the time element to be provided for in this Court’s

mandate during this period of transition. The mandate of

this Court should make it clear that, notwithstanding in

equality of facilities, the local courts shall in the exercise

of their equity powers be permitted to grant such relief as

they deem proper after consideration of the physical, eco

nomic and social conditions of the community and upon a

showing of a bona fide effort directed toward orderly de

segregation.

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 17

ARGUMENT—FORM OF MANDATE.

I. The Decree of the Court of Chancery, as Affirmed by the

Supreme Court of the State of Delaware, Should Be

Affirmed.

The two cases from the State of Delaware which are

before this Court presented the question of the propriety of

the Order of the Chancellor directing admission of Negro

children to two public schools formerly restricted in ac

cordance with the Constitution of the State of Delaware to

white children where the Court found that the facilities

available to the Negro students were not equal to those

available to white students. The issue for determination

by this Court was whether the proper decree should not

have been one directing the authorities in charge of public

education in the State of Delaware to equalize the sepa

rate facilities.

The decision of this Court in Brown v. Board of Edu

cation of Topeka, 347 IT. S. 483, 98 L. ed. (Advance p. 583),

74 S. Ct. 686 has eradicated the principle of “ separate but

equal” education upon which the Delaware cases were

predicated and hence has foreclosed the issues of the in

stant cases, with the exception of the question involving

the immediacy of the right of the Negro children to admis

sion to the public schools formerly available only to white

students. The matter before the Court now is the imple

mentation of its decision of May 17,1954 by an appropriate

decree or mandate.

In compliance with the decrees of the Chancellor which

were affirmed by the Supreme Court of Delaware,23 the

plaintiffs in these cases were admitted to the Hockessin

and Claymont Schools. Inasmuch as they have remained

in those schools since the Fall of 1952 without incident or

social repercussion, it is felt that the conditions which war

23. Gebhart v. Belton, — Del Ch. —, 91 A. 2d 137.

rant postponement of desegregation in parts of Delaware

as well as in certain other states which we believe do jus

tify a deferment of the relief to which the plaintiffs are

entitled do not exist with respect to the two districts in

volved in the Delaware cases.

This Court has determined that further maintenance

of segregated public education violates the Constitution of

the United States. The primary reason for delaying relief

is an existing severe social inflexibility which would make

impracticable the immediate admission of Negro children

in white schools. The Court below found no such need for

postponement with respect to the plaintiffs in the Delaware

cases. Experience has sustained the wisdom of the result

decreed by the Delaware Courts. It is, therefore, our

recommendation, that the proper order to be entered in the

instant Delaware cases, involving the named plaintiffs, is

an affirmance of the decision of the Supreme Court of

Delaware.

II. Recommendations With Respect to the Mandate.

18 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

(A) Introduction.

This Court in its decision on May 17, 1954 requested

that the parties to the several actions before this Court

present further argument on questions formerly pro

pounded by this Court with respect to the form of relief

to be given pursuant to its decision. The Court expressed

a willingness to receive the views of the Attorney General

of the United States and the Attorneys General of those

States which either require or permit segregated public

education.

In view of the foregoing recommendation with respect

to the Delaware cases, our discussion of the questions raised

by this Court is for the assistance of the Court in the formu

lation of a proper mandate. The discussion is presented as

an aid to the Court, recognizing that many of the problems

raised by the other States bear a striking similarity to prob

lems existing in parts of the State of Delaware. Moreover,

the relief granted by this Court in the cases before it will

be the prophetic handiwork from which must flow the

orderly desegregation of public education in a large seg

ment of the country.

(B) This Court May and Should Permit a Gradual Adjust

ment from Segregated Public Education to a System

Without Race Distinction.

By the decision of May 17, 1954, this Court has in

validated almost a century of social tradition which has

been perpetuated under apparent constitutional sanction

for two generations.24 25 Social thinking, public mores and

school expenditures have been founded upon the time-

accepted doctrine of “ separate but equal” public education.

The factual review which appears earlier in this brief, as

well as similar reviews made in the briefs submitted on be

half of other states, demonstrate the somber extent to which

the doctrine of segregation in public education saturates

the thinking of the citizens of some of our states. This

Court has eradicated the constitutional sanction of this

tradition. A transition is required which only time can

effectuate. Shock is not the medium by which this transi

tion can be accomplished.

In formulating the appropriate relief, it must be borne

in mind that this Court has redefined a basic constitutional

right. In all of the cases before this Court, with the excep

tion of the Delaware cases,26 the lower courts either found

factual equality26 or avoided the consequences which the

Court now considers by allowing the public school author

ities an opportunity to improve their facilities in order to

24. Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 41 L. ed. 256, 16 S. Ct.

1138.

25. Gebhart v. Belton, — Del. Ch. -—, 91 A. 2d 137.

26. Brown, v. Board of Education of Topeka, 98 Fed. Supp. 797;

Briggs v. Elliott, 103 Fed. Supp. 920.

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 19

meet the requirements of the “ separate but equal” doc

trine.27 Opportunity to equalize facilities is now of no

significance if there is racial segregation. For the first

time, this Court has eliminated considerations of equality

of treatment. The Court in its interdiction of segregated

facilities has struck at the very heart of the public school

system in many states and of necessity has put in issue the

status of not only the named plaintiffs but all children who

are a part of segregated school systems.

The cases before this Court are from courts of equity.

One of the characteristics which has perpetuated the great

ness of equity jurisdiction is its flexibility of remedy. In

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321, 329, 88 L. ed. 754, 64

S. Ct. 587, 592, this Court said:

“ The essence of equity jurisdiction has been the

power of the Chancellor to do equity and to mould each

decree to the necessities of the particular case. Flex

ibility rather than rigidity has distinguished it. The

qualities of mercy and practicality have made equity

the instrument for nice adjustment and reconciliation

between the public interest and the private needs as

well as between competing private claims.”

Equity “ may mold its decree so as to accomplish practical

results—such results as law and justice demand.” North

ern Securities Co. v. United States, 193 U. S. 197, 360, 24

S. Ct. 436, 466.

In the formulation of equitable relief, “ it is always the

duty of a Court of equity to strike a proper balance between

the needs of the plaintiff and the consequences of the giving

of the desired relief. ’ ’ Eccles v. Peoples Bank of Lakewood

Village, 333 U. S. 426, 431, 92 L. ed. 784, 68 S. Ct. 641, 644.

Considerations of the public interest are of great im

portance in the formulation of an appropriate equity decree.

27. Davis v. County School Board, 103 Fed. Supp. 337; Briqqs

v. Elliott, 98 Fed. Supp. 529.

20 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 2 1

“ Courts of equity may, and frequently do go

much farther both to give and withhold relief

in furtherance of public interest than they are ac

customed to go when only private interests are in

volved.” Virginian Railway Go. v. System Federation

No. 40, 300 U. S. 515, 552, 81 L. ed. 789, 57 S. Ct. 592,

601; see also Mercoid Corp. v. Mid-Continent Invest

ment Co., 320 U. S. 661, 88 L. ed. 376, 64 S. Ct. 268;

Securities and Exchange Comm. v. U. S. Realty and

and Improvement Co., 310 U. S. 434, 84 L. ed. 1293, 60

S. Ct., 1044; Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U. S.

395, 90 L. ed. 1332, 66 S. Ct. 1086.

Time for adaptation or readjustment to a policy de

clared by a court is an important potion to which the courts

have adverted in striving for the equitable remedial bal

ance. This principle has been applied in at least two im

portant branches of the law, namely in cases involving elim

ination of nuisances and in cases of violation of the anti

trust laws.

In the nuisance field, the leading case of Georgia v.

Tennessee Copper Company, 206 II. S. 230, 51 L. ed. 1038,

27 S. Ct. 618, is an example in which this Court determined

that injunctive relief should be given “ after allowing a

reasonable time to the defendants to complete the struc

tures that they are now building, and the effort that they

are making to stop the fumes.” The decisions of various

state courts are in accord with the Georgia case, supra.

Hughson v. Wingham (Wash. S. Ct. 1922) 120 Wash. 327,

207 P. 2, 27 ALR 327; Caretti v. Broring Building Co. (Md.

Ct. App. 1926) 150 Md. 198, 132 A. 619, 46 ALR 1; State v.

Hutchins (N. H. S. Ct. 1919) 79 N. H. 132, 105 A. 519, 2

ALR 1685.28

Another case in which this Court allowed a reasonable

time for adjustment to the court’s holding is the case of

28. Other cases granting a reasonable time for adjustment to the

holding of the court in the field of nuisance appear in an annotation

in 46 ALR pp. 35-37.

New Jersey v. New York, 283 U. S. 473, 75 L. ed. 1176, 51

S. Ct. 519. By this decision, this Court held that the State

of New Jersey was entitled to relief from the dumping of

New York City garbage into the ocean off the New Jersey

coast. This Court permitted New York City to have a

period of approximately one and a half years to conform

to its decision. New Jersey v. New York, 284 U. S. 585, 75

L. ed. 506, 52 S. Ct. 120. Subsequent action before this

Court resulted in postponing the finality of the court’s de

cision until December 1935, a period of four years from

the entry of the first order in 1931.29

The complexity of modern business organization has

on various occasions led this and other courts to provide

for deferred relief. In cases where immediate injunctive

relief would have caused substantial public injury by cut

ting off the flow of vital commodities, this Court has per

mitted a period of transition. TJ. 8. v. American Tobacco

Co., 221 U. S. 106, 31 S. Ct. 632, 55 L. ed. 663; Standard Oil

Co. v. United States, 221 IT. S. 1, 31 S. Ct. 502, 55 L. ed. 619.

The Court will consider the best method of accomplishing

the declared result “ with as little injury as possible to the

interests of the general public.” United States v. Ameri

can Tobacco Co., supra.

Courts have faced the realities of complex situations

and after determination of the basic rights involved have

permitted extended periods for the formulation of an equi

table plan to implement the Court’s decision. United States

v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 IT. S. 131, 92 L. ed. 1260,

68 S. Ct. 915; United States v. National Lead Co., 332 IT. S.

319, 67 S. Ct. 1634, 91 L. ed. 2077. This Court, in passing

upon the length of the period of transition, has extended

that period beyond that fixed by the lower court. United

States v. American Tobacco Co., supra.

In the light of the numerous actions of this Court in

permitting flexible adaptation of relief to existing condi

29. New Jersey v. New York, 296 U. S. 259, 80 L. ed. 214, 56

S. Ct. 188.

22 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

tions, there is ample precedent for the granting of time

for adjustment in the cases now before this Court.

This Court must determine whether the equitable bal

ance militates in favor of gradual rather than immediate

relief. Under the “ separate but equal” doctrine, this Court

declared that a plaintiff who was deprived of educational

facilities equal to those made available by the state to any

other race was being deprived of a personal right,30 of a

nature which entitled the injured party to immediate ad

mittance to white educational facilities.31 The cases in

which that doctrine was announced involved institutions

of higher learning.32 The determination of the respective

cases affected few except the individual plaintiffs. Deseg

regation was effected at a level where the intellectual and

philosophical approach to the racial problem and the ma

turity of those affected in all probability would lead to a

degree of acceptance or tolerance not to be found in elemen

tary and high schools. The extent of racial desegregation

involved in those cases was minimal.

Whether the right to immediate admission to white

schools is an absolute right even under the “ separate but

equal” doctrine remains open to question. In the case of

Fischer v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147, 68 S. Ct. 389, 92 L. ed. 604,

this Court had occasion to consider whether the order en

tered by the District Court pursuant to the mandate of

this Court in Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of

Oklahoma, supra, properly complied with the mandate.

30. State of Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337,

59 S. Ct. 232, 83 L. ed. 208.

31. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education,

339 U. S. 637, 70 S. Ct. 851, 94 L. ed. 1149.

32. Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, 332

U. S. 631, 68 S. Ct. 299, 92 L. ed. 247 (Law School); Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 70 S. Ct. 848, 94 L. ed. 1114 (University of

Texas Law School) ; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for

Higher Education, supra, (University of Oklahoma) ; State of Mis

souri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra, (School of Law of State Uni

versity of Missouri).

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 23

The order of the District Court, which alternatively di

rected (1) that plaintiff he admitted to the University or

(2) that defendant refuse admission to all applicants until

a separate law school of equal facilities and standing could

be established, was held by this Court not to have departed

from this Court’s mandate.

Factors which weighed in favor of immediate relief

under the “ separate but equal” cases are overweighed by

problems of social acceptance and social, economic and

facility readjustment growing out of the decision of May

17, 1954. At least in some areas, there must be a twilight

era when personal rights must give way to community prob

lems and general public welfare.

Recognizing the pressing need in certain areas for

permitting gradual readjustment to the principle of non

segregation, we direct the Court’s attention to the need

for clarification of the position of the old “ separate but

equal” doctrine, insofar as there may be factual educa

tional inequality. As we have pointed out, heretofore, a

finding of inequality has been held to justify immediate ad

mission to a theretofore segregated school. If this prin

ciple is to continue and is applied at the elementary and

high school level, there is no doubt of the serious repercus

sions which will follow. Hence, it is submitted that this

Court should make amply clear that any relief in the field

of public education should be given on the basis of the

rights declared by this Court in its decision of May 17,

1954 and that all relief should be based upon the principles

which we have discussed.

(C) This Court Should Remand the Cases to the Lower

Courts for Formulation of Decrees for the Admit

tance of Plaintiffs to Public Schools Without Regard

to Race as Soon as Practicable Within a Time Limit to

Re Set by This Court.

Based upon the conclusion reached in the foregoing

section that a period of gradual adjustment to non-segre-

24 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 25

gated public education is advisable in some localities, it is

necessary to consider the best method of accomplishing this

result.

From the factual review appearing in this brief, as well

as those appearing in briefs filed on behalf of other states,

it is evident that a wide diversity of public attitude exists

on the subject of non-segregation. This diversity exists not

only between states but even within the states, as in the case

of the State of Delaware. Immediate desegregation result

ing in an uneventful transition in one locality would result

in strong community upheaval in another locality. Hence,

there is no standard formula, no elixir by which the transi

tion can be uniformly effected.

The transition can be moulded only through wisdom

based upon a knowledge of the facts and circumstances and

psychology of the community affected. These facts can

best be obtained and the transition can be most smoothly

effectuated by the courts in which these cases arose.

This Court has on numerous occasions remanded cases

to lower courts for proceedings in accordance with the man

date of this Court. Russell v. Southard, 12 How. (U. S.)

139, 13 L. ed. 927; Universal Battery Co. v. United States,

281 U. S. 580, 50 8. Ct. 422, 74 L. ed. 1051; Sipuel v. Board

of Regents of Oklahoma University, supra; Sweatt v.

Painter, supra.

The ultimate disposition of the cases before the Court

requires the determination of additional facts. Where ad

ditional facts are required, this Court has remanded cases

to the lower court for ascertainment of those facts. Pan

ama Mail S. S. Co. v. Vargas, 281 U. S. 670, 50 S. Ct. 448,

74 L. ed. 1105; Universal Battery Co. v. United States, su

pra; Ballard v. Searls, 130 U. S. 50, 9 S. Ct. 418, 32 L. ed.

846. This procedure has been followed in fixing the relief

to be given. Rogers v. The St. Charles, 19 How. (U. S.)

108, 15 L. ed. 563; United States v. American Tobacco Co.,

supra.

This Court does not have before it, nor should it under

take, the Herculean task of outlawing the existing system

of public education, nor of creating a substitute. This

Court has before it the rights of individual children. Those

rights can best be brought to fruition at the local level by

the courts of first instance. To this end, the cases should be

remanded for determination of the immediacy or remote

ness of the relief.

The mandate or decree of this Court should be the bea

con light by which the further action of the lower courts

can be guided. It should make clear that the rights enun

ciated in the decision of May 17, 1954 are to be effectuated

by appropriate relief either immediately or as soon there

after as community acceptance will permit. Eelief should

be deferred by the local courts only after thorough consid

eration is given to numerous factors such as the history

of race relations in the community affected, the extent of

social and economic segregation within the community, the

permanency of the population, the extent of migration to

and from the community, and the condition and capacity

of existing facilities. Eecognizing that the ultimate

achievement is the granting of full relief to the plaintiffs,

in order to entertain a deferment in the perfection of that

goal, the Court must be convinced that those charged with

the responsibility of effecting total integration are taking

constructive steps toward the elimination of the segrega

tion barrier and that those steps are being bona fidely car

ried out as expeditiously as it is possible.

In approaching this problem, the realization must be

ever present that the Court is the instrumentality through

which an individual is given the opportunity to exercise

his constitutional right. It cannot and does not undertake

to create or enforce social acceptance for an individual or

race. The words of Chief Justice Yinson in the case of

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Educa

tion, supra, are particularly pertinent. He stated (at p.

454):

“ The removal of the state restrictions will not

necessarily abate individual and group predilections,

26 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate 27

prejudices and choices. But at the very least, the state

will not be depriving appellant the opportunity to se

cure acceptance by his fellow students on his own

merits. ’ ’

A further subject for inclusion in the mandate or de

cree of this Court is designation of a final or ultimate date

within which communities may expect courts to defer the

granting of immediate relief to those claiming violation of

their constitutional rights because of a segregated public

education system. Recognizing the local resistance to the

perfection of relief under the decision of May 17, 1954 and

a strong desire to defer the piercing of the segregation bar

rier for an extended—not an indefinite—period, it is felt

that although broad discretion should be vested in the lower

courts in deferring relief, this Court should set a cut-off or

ultimate date for the deferring of relief in order that the

decision of May 17, 1954 may not be completely thwarted.

In the prior section of this brief dealing with the advis

ability of providing for a period of time within which re

lief is to be ultimately granted, we have cited various cases

in which this Court has permitted a deferral of ultimate

relief. Deferral periods of six months33 and one year34

have received the approval of this Court in the anti-trust

field. An adjustment over a four year period was per

mitted in the New York City garbage case,85 and there was

a span of nine years before ultimate disposition in the case

in which copper companies were prohibited from discharg

ing noxious gases over the State of Georgia.86 33 34 35 36 * * *

33. Standard Oil Co. v. United States, supra; United States v.

American Tobacco Co., supra; United States v. Paramount Pictures,

Inc., supra.

34. United States v. National Lead Co., supra.

35. New Jersey v. New York, 283 U. S. 473, 75 L. ed. 1176, 51

S. Ct. 519; 284 U. S. 585, 75 L. ed. 506, 52 S. Ct. 120; 296 U. S.

259, 80 L. ed. 214, 56 S. Ct. 188.

36. Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206 U. S. 230, 51 L. ed.

1038, 27 S. Ct. 618; 237 U. S. 474, 59 L. ed. 1054, 35 S. Ct. 631;

237 U. S. 678, 59 L. ed. 1173, 35 S. Ct. 752; 240 U. S. 650, 60 L. ed.

846, 36 S. Ct. 465.

28 Brief for Petitioners on the Mandate

Although these precedents are not factually analogous

to the present situation, they are indicative of the extent

to which this Court has permitted deferment of relief in

order to effect a gradual transition. We respectfully sub

mit that this Court out of the bounty of its wisdom should

fix as an ultimate date beyond which there will be no fur

ther postponement of relief under the decision of May 17,

1954 a date which will afford to the States an opportunity

to plan, educate and promote community acceptance and

orderly physical fruition of desegregation.

CONCLUSION.

In the light of the decision of this Court of May 17,

1954 and the successful integration of respondents into the

Claymont and Hockessin Schools, the two Delaware cases

should be affirmed.

The mandate of this Court should include instructions

to the lower courts that, in granting or deferring immediate

relief, they shall exercise equitable discretion according to

local conditions provided that a constructive transitional

program is shown to be in progress and subject to the lim

itation that ultimate relief by way of admission on a non-

segregated basis shall be effected no later than a date which

this Court should fix.

Respectfully submitted,

H. Albert Young,

Attorney General of the State of Delaware,

Clarence W. Taylor,

Deputy Attorney General of the State of Delaware,

A ndrew D. Christie,

Special Deputy to the Attorney General.

D

is

tri

ct

s

Sc

ho

ol

s

EXHIBIT 1

SCHOOLS, SCHOOL DISTRICTS, AND ATTENDANCE AREAS FOR THE EDUCATION OF COLORED CHILDREN, SEPTEMBER, 1954

(A)

Colored Schools in the

Special Districts

and colored

School Districts

(B)

White Dist. in which the

school bldg, of Column

(A) is geographically

located

(C)

Spec. Dists. which

have Administrative

Jurisdiction over

schs. listed in

Column (A)

(D)

Attendance Area of

schs. and sch. dists.

in Col. (A) totally

within the boundary

of a Spec. Dist.

(E)

Attendance Area of schs.

and sch. dists. in Col.

(A) totally within bound

ary of a white State

School District

(F)

Attendance Area of Schools or School Dists. in Col, (A) within the

boundaries of more than one white district

Special Districts Other White School Districts

Star Hill Caesar Rodney Caesar Rodney Caesar Rodney

Dunbar Caesar Rodney Caesar Rodney Caesar Rodney

Claymont Col. Claymont Claymont Claymont

Booker T. Washington Dover Dover Dover, Caesar Rodney, Frederica, Kenton, Hartly, Magnolia, Fel-

Smyrna ton, Leipsic, Little Creek, Clayton, Oak

Point, Rose Valley, Wiley’s

Richard Allen Georgetown Georgetown Georgetown

P. S. duPont Harrington Harrington Harrington

Paul L. Dunbar Laurel Laurel Laurel Delmar, Bethel

Lewes Col. Lewes Lewes Lewes, Rehoboth

Benjamin Banneker Milford Milford Milford

Newark Col. Newark Newark Newark

Booker T. Washington New Castle New Castle New Castle

Buttonwood New Castle New Castle New Castle

Frederick Douglas Seaford Seaford Seaford Blades

Thomas D. Clayton Smyrna Smyrna Smyrna Clayton

Delaware City Delaware City Delaware City

Hockessin Col. Hockessin Hockessin, Yorklyn

Iron Hill Newark Newark

Leis Chapel Townsend Townsend

L. L. Redding Middletown Newark, Smyrna Delaware City, Townsend, Middletown,

Odessa, Commodore MacDonough,

Port Penn, Eden, Clayton

Millside Rose Hill-Minquadale Rose Hill-Minquadale

Mt. Pleasant Middletown Middletown

Newport Newport Alexis I. duPont Newport, Marshallton, Christiana, Hoc-

kessin, Stanton, Alfred I. duPont,

Yorklyn, Richardson Park, Oak Grove

Townsend Townsend Townsend

Cheswold Dover Dover

Fork Branch Dover Dover

Henry Comprehensive Dover Dover, Smyrna, Caesar Felton, Oak Point, Magnolia, Rose

Pligh School Rodney, Harrington Valley, Wiley’s, Frederica, Leipsic,

Hartly, Little Creek, Kenton, Clayton

Kenton Kenton Kenton

Lockwood Hartly Hartly

Mt. Olive Magnolia Magnolia

Union Frederica Harrington Frederica, Felton, Magnolia

Viola Felton Caesar Rodney Felton

Woodside Caesar Rodney Caesar Rodney

Blocksom’s Seaford Seaford

Bridgeville-T rinity Bridgeville Bridgeville

Delmar Delmar -— ----———— D etear——-———— —---- '-- ----•. " '

Drawbridge Lewes Lewes, Georgetown

Ellendale Ellendale Ellendale

Frankford J. M. Clayton J. M. Clayton, Lord Baltimore, Roxana

Jason Comprehensive All Special Dists. in All State Board Unit schools in Sussex

High School Georgetown Sussex County County

Greenwood Greenwood Greenwood, Farmington

Lincoln Lincoln Lincoln

Millsboro Millsboro Millsboro

Milton Milton Milton

Nanticoke Indian Millsboro Millsboro

Nassau Lewes Lewes

Owen’s Corner Delmar Delmar

Portsville Laurel Laurel Bethel

Rabbit’s Ferry Lewes Lewes

Rehoboth Rehoboth Rehoboth

Ross Point Laurel Laurel

Selbyville Selbyville Selbyville, Roxana

Slaughter Neck Milford Milford Lincoln, Milton

Warwick 203 Millsboro Millsboro

Warwick 225 Millsboro Millsboro

Williamsville Selbyville Selbyville

Exhibit 2 31

EXHIBIT 2

June 9, 1954

Mr. J. Olirum Small

President, State Board of Education

Delaware Trust Building

Wilmington, Delaware

Re: Gebhart v. Belton, et al. and Bulah, et al.

Dear Mr. Small:

The United States Supreme Court, by its unanimous

decision in Brown v. Board of Education, has struck down

‘ ‘ the separate hut equal doctrine ’ ’ in the field of public edu

cation.

The Court decided that segregation of children in pub

lic schools solely on the basis of race, even though the phys

ical facilities and other tangible factors may be equal, de

prives the children of the minority group of equal educa

tional opportunities.

The Court said, “ separate educational facilities are

inherently unequal” and concluded that, “ the plaintiffs

and others similarly situated, for whom the actions have

been brought, are, by reason of the segregation complained

of, deprived of the equal protections of the laws guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment.

According to the opinion, we are required to submit

briefs by October 1, 1954 for the purpose of assisting the

Court in formulating decrees to bring about an effectual

gradual adjustment from existing segregated systems to a

system not based on color distinctions.

The Court recognized that the decision presents prob

lems of considerable complexity because of the great variety

of local conditions. The opinion nullifies our constitutional

provision and its statutory counterpart providing for sep

arate hut equal educational facilities. The Court an

nounced that segregation is a denial of the equal protection

of the laws.

32 Exhibit 2

The opinion is not a self-executing one and does not

call for immediate integration. It is possible for any school

district, however, where circumstances permit and the sit

uation warrants, to effect integration consonant with the

law of the land as now announced by the recent Supreme

Court opinion without doing violence to the Constitution

and laws of our own State, notwithstanding the fact that

the mandate of the United States Supreme Court has not

yet been handed down.

On the other hand, the State Board of Education may

well require time within which to bring about integration in

an orderly fashion within the spirit and meaning of the

recent Supreme Court decision. I am sure that the Board

will formulate some concrete plan directed towards an ef

fective gradual adjustment from existing segregation in

the public schools in Delaware to a system of non-segre

gation in accordance with the spirit, purpose and intent of

the opinion as expeditiously as it is possible for it to do so.

I should like to meet with the members of your Board

so that we may review together a number of problems, some

of which we touched upon at our conference with the Gover

nor, relating to specific localities in our State in order that

I may be in a position to inform the members of the United

States Supreme Court what plan for de-segregation has

been adopted by our Board of Education of the State of

Delaware, and when we expect it may finally be put into

effect.

Based upon the plan your Board has made and the in

formation given me to carry that plan into effect, I will be

able to present to the United States Supreme Court the

specific terms and directions upon which the decree or man

date should be framed.

Very truly yours,

/ s '/ H. Albert Y oung

A ttorney General

HAY :mjw

Exhibit 3 33

EXHIBIT 3

State Board of Education Policies (I) Regarding Desegre

gation of the Schools of the State

The State Board of Education held a special meeting

in Dover, Friday evening, June 11, and issued the following