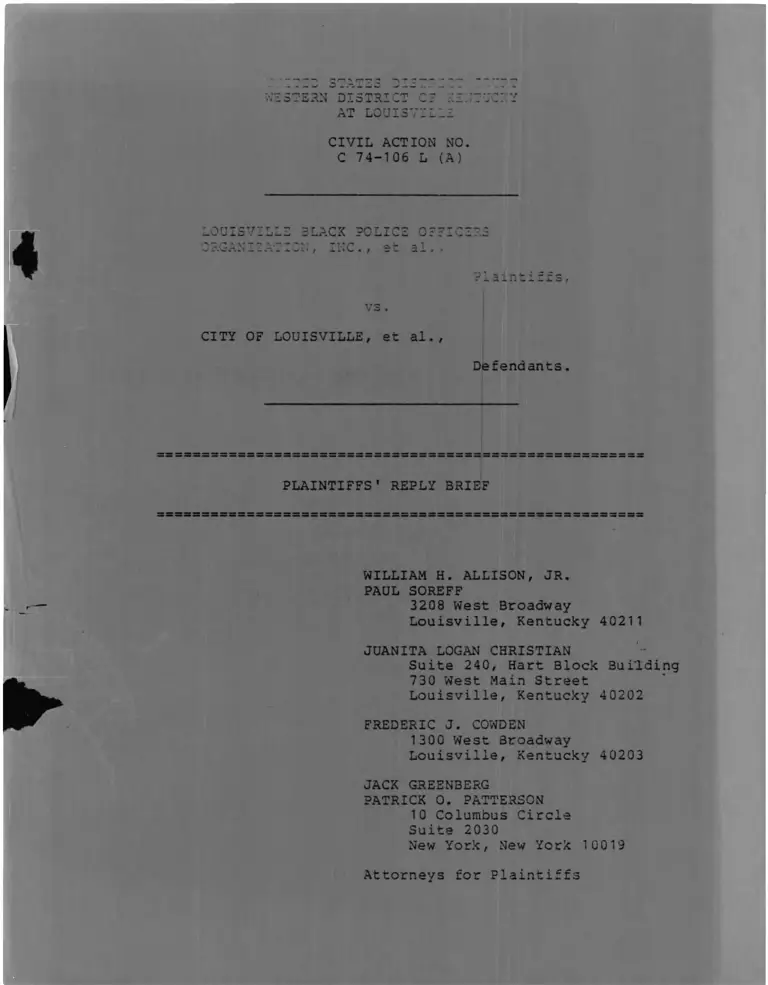

Louisville Black Police Officers Organization Inc. v. City of Louisville Plaintiffs' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

May 18, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Louisville Black Police Officers Organization Inc. v. City of Louisville Plaintiffs' Reply Brief, 1979. 597cc5f2-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2ad1d906-b7c2-4302-bbbf-688cc0fde1cd/louisville-black-police-officers-organization-inc-v-city-of-louisville-plaintiffs-reply-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

WESTERN DISTRICT CE IT

AT LOUISVILLE

CIVIL ACTION NO.

C 74-106 L (A)

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

0 RQ AN H A T TEN , INC., e t a 1. ,

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al.,

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' REPLY 3RIEF

WILLIAM H. ALLISON, JR.

PAUL SOREFF

3208 West Broadway

Louisville, Kentucky 40211

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN

Suite 240, Hart Block Building

730 West Main Street

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

FREDERIC J. COWDEN

1300 West Broadway

Louisville, Kentucky 40203

JACK GREENBERG

PATRICK 0. PATTERSON

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

INDEX

Table of Authorities ......................... iv

Table of Abbreviations........................ x

Cross Reference Table .................................... xi

ARGUMENT .................................................. 1

I. THE DEFENDANTS' POST-TRIAL BRIEFS AND

PROPOSED FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

CONTAIN NUMEROUS ERRORS AND MISSTATEMENTS

OF THE FACTS AND THE LAW ..................... 1

A. Defendants Have Made Serious Factual

Errors and Misstatements of the

Record .................................... 1

1. Major Statistical Errors ............. 2

2. Misstatements on Minority

Recruitment .......................... 3

3. Misstatements and Errors on Tests

and Test Validation ................. 6

4. Contradictory Statements ............. 6

B. Defendants Have Made Many Errors

of Law .................................... 3

II. PLAINTIFFS ARE NOT REQUIRED TO PROVE

INTENTIONAL RACIAL DISCRIMINATION TO

ESTABLISH A VIOLATION OF EITHER TITLE VII

OR SECTION 1981 ................................ 10

A. The Extension of the Title VII Effect

Rule to Public Employers Was a Valid

Exercise of Congressional Power Under

Both the Commerce Clause and Section 5

of the Fourteenth Amendment .............. 12

1. The Commerce Clause .................. 13

2. Section 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment ............................ 14

Page

- i -

Page

B. Evidence of Discriminatory Intent Is Not

Required to Prove a Violation of

Section 1981 ............................. 19

C. The Record Shows, in any Event, that

Defendants Engaged in Intentional

Discrimination ........................... 22

III. PLAINTIFFS HAVE ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE

CASE OF INTENTIONAL DISCRIMINATION WHICH

DEFENDANTS HAVE FAILED TO REBUT ............... 23

A. Plaintiffs Have Established a Prima

Facie Case of Intentional

Discrimination ........................... 24

1. Defendants have misconstrued

Hazelwood ............................ 24

2. Even under defendants' theory of

the relevant labor market,

plaintiffs have established a

prima facie case ..................... 28

B. Defendants Have Failed To Rebut Plaintiffs'

Prima Facie Case of Intentional

Discrimination ........................... 33

1. When defendants' computational errors

and arbitrary assumptions are corrected,

their labor market analysis for the

statutory liability periods provides

further support for plaintiffs'

prima facie case ..................... 34

a. §§ 1981, 1983 and the Fourteenth

Amendment ........................ 3 4

b. Title VII ........................ 39

2. When defendants' computational errors

and arbitrary assumptions are corrected,

their applicant flow analysis provides

further support for plaintiffs'

prima facie case ..................... 41

3. Defendants have applied an incorrect

legal standard to plaintiffs'

testimonial evidence that black

applicants were treated in an arbitrary,

subjective, and discriminatory

manner ................................ 45

- ii -

IV. DEFENDANTS HAVE NOT CARRIED THEIR BURDEN OF

SHOWING THAT TEST 165.1 IS MANIFESTLY RELATED

TO PERFORMANCE OF THE JOB OF A LOUISVILLE

POLICE OFFICER ................................. 50

* A. Federal Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures Are Entitled to Great Deference

and Should Be Followed in this Case ....... 50

B. Defendants Have Not Demonstrated that

Test 165.1 Is Valid for Use in Selecting

Louisville Police Officers ............... 56

1. Construct Validity ................... 58

2. Content Validity ..................... 62

3. Concurrent Validity ................. 70

4. Predictive Validity .................. 75

5. Cutoff Score and Ranking ............. 7 7

6. Elimination of Adverse Impact ......... 80

V. THE COURT SHOULD GRANT AFFIRMATIVE HIRING

RELIEF AND AN INTERIM AWARD OF COUNSEL FEES

TO PLAINTIFFS .................................. 85

CONCLUSION ............................................... 89

Appendix A: Brief Amicus Curiae for the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

in County of Los Angeles v. Davis, No. 77—1553

*

g a g e

- iii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases p age

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ..... 10,11,50,51,

54,55,58,71,

81,85

Allen v. City of Mobile, 18 FEP Cases 217 (S.D.

Ala. 1978) ......................................... 51,56,77,79,

80,82,83

Association Against Discrimination v. City of

Bridgeport, 19 FEP Cases 115 (2d Cir.

1979) .............................................. 78,83

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport Civil

Service Commission, 354 F. Supp. 778 (D. Conn.),

aff'd in pertinent part, 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir.1973),

cert, denied, 421 U.S. 991 (1 975) ................. 70

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport Civil Service

Commission, 497 F.2d 1113 (2d Cir. 1 974).......... 86

California v. Taylor, 353 U.S. 553 (1 957) .............. 13

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) .............. 27,30,37,39,

42,43

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434

U.S. 412 (1 978) .................................... 85

County of Los Angeles v. Davis, 47 U.S.L.W. 4317

(March 27, 1 979) ................................... 1 1,20

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334

(9th Cir. 1977), vacated as moot, 47 U.S.L.W.

4317 (March 27, 1 979) ............................. 1 1 , 1 2

Detroit Police Officers Association v. Young,

446 F. Supp. 979 (E.D. Mich. 1 978) ................ 27,29

Donnell v. General Motors Corp., 576 F.2d 1292

(8th Cir. 1 978) .................................... 42

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) .......... 10,11,15,42,48

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976 (D.C.

Cir. 1 975) ......................................... 60

EEOC v. Local 14, Operating Engineers, 553 F.2d

251 (2d Cir. 1 977) .................................. 29

Euclid v. Ambler Realty, 272 U.S. 365 ( 1 926) .......... 18

Evans v. United Air Lines, Inc., 431 U.S. 554

(1 977) ............................................. 26

IV

Page

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. City

of St. Louis, 549 F.2d 506 (8th Cir.),

cert. denied, 434 U.S. 819 (1 977) ................. 19

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 ( 1 976) ............. 1 5

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

( 1 976) ............................................. 45

Friend v. Leidinger, 446 F. Supp. 361 (E.D. Va. 1977),

aff'd, 588 F . 2d 61 (4th Cir. 1 978) ................ 27,29

Fry v. United States, 421 U.S. 542 ( 1 975) .............. 13

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 57 L.Ed. 2d 957

(1978) ............................................. 11,46,80

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969).... 17

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ......... 10,12,17,23,

46,47,50,51,

81

Guardians Association v. Civil Service Commission,

490 F . 2d 400 (2d Cir. 1973) ....................... 54

Harrington v. Vandalia-Butler Board of Education,

418 F. Supp. 603 (S.D. Ohio 1976) ................ 19

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433

U.S. 299 (1 977) .................................. 8,1 5,22-28

30,32,33,38,

40,41,44

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 ( 1 978) ................... 86,88

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) .................... 11,12,23,24,27,

28,33,42,45,46,

47,49

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28

(5th Cir. 1 968) .................................... 43

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421

U.S. 454 ( 1 975) .................................... 1 9

Jones v. Milwaukee County, 13 FEP Cases 307 (E.D.

Wis. 1 976) ........................................ 1 9

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ............. 15,16,18

- v -

Kirkland v. New York State Dept, of Correctional

Services, 374 F. Supp. 1361 (S.D.N.Y. 1974),

aff'd in pertinent part, 520 F.2d 420 (2d

Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 974 (1976) .... 79

Lassiter v. Northampton Election Board, 360 U.S.

45 ( 1 959) .......................................... 15

l

Long v. Ford Motor Co., 496 F .2d 500 (6th Cir. 1974) ... 20

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ............................................. 11,46,47,80

National League of Cities v. Usery, 426 U.S.

833 (1976) ......................................... 12,13,14

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 1 12 (1 970) ................ 15,1 6,1 8

Parden v. Terminal Railway Co., 377 U.S. 184

(1964) ............................................. 13

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 ( 1978) ................................ 1 9,82

Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d

333 (1 0th Cir. 1 975) ................................ 43

Richardson v. McFadden, 540 F.2d 744 (4th Cir. 1976) ... 21

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F .2d 1340,

vac'd and rem'd on other grounds, 423

U.S. 809 (1 975) .................................... 74

Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F.2d 511

(6th Cir. 1 976) .................................... 46

Smith v. Union Oil Co., 17 FEP Cases 960 (N.D. Cal.

1977) .............................................. 29

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966) ............................................. 15,16,18,70

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F. Supp. 87 (E.D.

Mich. 1973), aff'd in pertinent part sub nom EEOC v.

Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d 301 (6th Cir. 1975),

vac'd and rem'd on other grounds, 431

U.S. 951 (1 977) ........ ........................... 29

Trustees of Keene State College v. Sweeney, 58 L.Ed. 2d

21 6 ( 1 978) ......................................... 1 1

United States v. California, 297 U.S. 175 (1936) ....... 13

vi

Page

United States v. City of Chicago, 573 F.2d 416

(7th Cir. 1 978).................................... 19,54

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906

(5th Cir. 1 973) ................................... 53,54,77

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d

544 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984

(1971) ........ 7777................................ 28

United States v. South Carolina, 445 F. Supp. 1094

(D.S.C. 1977), aff'd mem, sub nom National

Education Association v. South Carolina, 434 U.S.

1026 (1978) ........................................ 52,67,68,69

United States v. Virginia, 454 F. Supp. 1077

(E.D. Va. 1 978) ................................... 75

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977), on remand, 558 F.2d 1283 (7th Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1 025 ( 1 978) ........ 20

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490

F. 2d 387 (2d Cir. 1 973) ........................... 61

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ............... 12,13,15,25,

52

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes, Rules, and Regulations

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment ....... passim

United States Constitution, Art. I, § 8, cl. 3 ......... 13

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ........................................ passim

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ........................................ passim

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. §§ 2000e £t seq.............................. passim

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 79 Stat. 438 ................ 1 6

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1970, 84

Stat. 315, 42 U.S.C. § 1973a ...................... 16

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,

86 Stat. 103 ....................................... 12

- vii -

Page

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Guidelines

On Employee Selection Procedures, formerly

29 C.F.R. § 1607 ................................... 52, 53,54,55,

70,76

Federal Executive Agency Guidelines on Employee

Selection Procedures, 41 Fed. Reg.

51734 (1976) ....................................... 51,54,55,60,

61,73,76 ,

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures (1978), 43 Fed. Reg. 38290

(Aug. 25, 1978), 43 Red. Reg. 40223 (Sept. 11,

1978) ............................................. 51,55,56,57,

58,60-68,75,

76,78,80,82,

83

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 33 ............... 86

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 34 ............... 87

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 37 ............... 87

Legislative History

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong.

1st Sess. (1971) .................................... 12,16,17,18

S. Rep No. 92-415, 92dCong., 1st Sess. (1971) ......... 12,16,17,18

118 Cong. Rec. 790 (1 972) ................................ 17

Other Authorities

American Psychological Association, Standards for

Educational and Psychological Tests ( 1 974) ...... 50,53,54, 59,63,

; 69,70,71,76

APA Division of Industrial-Organizational Psychology,

Principles for the Validation and Use of

Personnel Selection Procedures ( 1 975) 77.......... 50,53,60,61 ,

----- ------------------------- 70,76

Cohen, Congressional Power to Interpret Due Process

and Equal ProtectionT 2 7 Stan. L. Rev. 603

(1 975 ) ............................................. 1 8

Finkelstein, The Application of Statistical Decision

Theory To Jury Discrimination Cases, 513

Harv. L. Rev. 338 ( 1 966) ......................... 38

- viii -

Page

F. Mosteller, R. Rourke & G. Thomas, Probability

with Statistical Applications (2d ed. 1 97 0") ...... 38

Note, Federal Power to Regulate Private Discrimination:

The Revival of the Reconstruction Era Amendments,

74 Colum. L. Rev. 449 ( 1 974) ................... .... 18

i

Orloski, The Enforcement Clauses of the Civil War

Amendments: A Respository of Legislative

Power, 4 9 St. John's L. Rev. 4 93 ( 1 975) .......... 18

An Overview of the 1978 Uniform Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures, 43 Fed.

Reg. 38290 (Aug. 25, 1 978) ....................... 55

Questions and Answers on the Uniform Guidelines,

44 Fed. Reg. 11996 (March 2, 1979) ............. 14,48,76,83-84

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, For All The People

. . . By All The People (1969) .... ............... 16,17

Yackle, The Burger Court, "State Action" and

Congressional Enforcement of the Civil War

Amendments, 27 Ala. L. Rev. 479 ( 1975) ............ 18

I X

TABLE OF ABBREVIATIONS

"City Brief" Defendants' Post-Trial Brief

"City FOF"; "City COL" Defendants' Proposed Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law

"FOP Brief" Intervening Defendants' Post-

Trial Brief

"FOP FOF"; "FOP COL" Intervening Defendants' Proposed

Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law

"Plaintiffs' Brief" Plaintiffs' Post-Trial Brief

"Plaintiffs' FOF";

"Plaintiffs' COL" Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law

For other abbreviations, see Plaintiffs' Brief at xii.

x -

CROSS REFERENCE TABLE

The following table lists the pages in this reply

brief where plaintiffs' responses to many of defendants'

proposed findings of fact can be found. Plaintiffs have not

attempted to respond to every factual error or to each mis

statement of the record. See pp. 1-8, infra.

City Defendants' Proposed

Findings of Fact

____ (City FOF Numbers)

Plaintiffs' Reply Brief

(Page Numbers)

Section IV

25A . .

25G ............................ 5

28 ............................ 7

34 7

48 48

79 7

84 80

91 37

91-92 ........................... 7-8

Section V

96-260 (also,

FOP FOF 3-4, 11-17)............. 45

Section VI

262-287 .........................3-4

298 ............................ 4

327-328 ........................ 4

345 ............................. 4

Section VIII

412 ................. 2,3,8,35,36,37

413-422 ........................ 42

413-414 ........................ 34

41 6-420 ........................ 43

420 ............................. 43

421 ............................. 7

422 ............................ 34

424 . . ........................... 5

425 ............................ 43

xi

City Defendants' Proposed

Findings of Fact

____ (City FOF Numbers)

Plaintiffs' Reply Brief

(Page Numbers)

Section VIII (cont'd.)

433

434-435

435

436-438

438-440

439

442___

447 ...

. . . 42

2,36,40

6-7,39

. . . 34

. . . 42

7

8

. . . 42

Section IX

459 7-8

461 80

464-478 57

468-472 74

484 80

492-494 63

522 63

523-546 64

531 65

556 66

559 66

561-562 66

568-570 72

573 63

580 . 73

581 . 80

587-588 63

590 62

594 54

602 ............................ 62

610 70

612 .6,71

613 . 72

619 65

622 . 77

623 . 77

625 . 79

626 . 78

627 . 78

629 . 78

630 . 79

635 73

639 76

649 76

652-657 54

- x n

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY

AT LOUISVILLE

CIVIL ACTION NO.

C 74-106 L (A)

LOUISVILLE BLACK POLICE OFFICERS

ORGANIZATION, INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

CITY OF LOUISVILLE, et al.,

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' REPLY BRIEF

I. THE DEFENDANTS' POST-TRIAL BRIEFS AND PROPOSED

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS CONTAIN NUMEROUS

ERRORS AND MISSTATEMENTS OF THE FACTS AND THE LAW.

A * Defendants Have Made Serious Factual Errors

and Misstatements of the Record.

The trial of the issues presently before the Court in

this case took approximately five weeks; it generated more

than 4,000 pages of recorded testimony and thousands of addi

tional pages of documentary exhibits. In plaintiffs' proposed

findings of fact and in our principal brief, we set forth and

substantiated in careful detail the relevant facts contained in

this record.

1/ 2/

The defendants and the intervening defendants, in

more than 350 pages of post-trial briefs and proposed findings of

fact and conclusions of law, have not identified a single erroneous

reference to the record by plaintiffs. In contrast, the defen

dants have made a substantial number of serious factual errors

2/and misstatements of the record. Although plaintiffs have

not attempted to list every such error and misstatement, we have

compiled a cross reference table, pp. , supra, which collects

references from throughout this reply brief to the defendants'

proposed findings. Some of the more glaring examples are discussed

below.

1. Major Statistical Errors

Defendants have substantially undercounted the number

of police officers selected between March 14, 1969, and the time

of trial. They entirely excluded three classes of police recruits

(City FOF 412, 434; City Brief at 49); they incorrectly identified

another recruit class as having been selected before the beginning

of the Title VII liability period (City FOF 435; City Brief at 51);

they improperly classified many post-March 14, 1974, selections

j_/ The defendants are the City of Louisville, the Mayor,

the Chief of Police, the Civil Service Board and its members,

and the Personnel Director. See Plaintiffs' FOF 3. Defendants

are collectively referred to herein as "the City".

2/ The intervening defendants are the Fraternal Order of

Police, Louisville Lodge No. 6 and its president. Intervening

defendants are collectively referred to herein as "the

FOP" .

3/ The factual errors made by the intervening defendants are

for the most part similar to those of the defendants and are

not treated separately here.

2

as having occurred before this suit was filed (City FOF 412;

City Brief at 49); and they erroneously used the number of whites

selected as the total number selected in each of three years

(City Brief at 49; but cf. City FOF 412). See pp. 34-37,

infra. This astonishing string of errors has invalidated their

attempt to rebut plaintiffs' statistical evidence of discrimina

tion. See section III B, infra.

2. Misstatements on Minority Recruitment

When defendants were asked shortly after the filing of

this lawsuit in 1974 whether they have "now or ... ever had any

program to actively seek black or other minority persons as

officers for the purpose of increasing the numbers of minority

group officers in the Department," they responded as follows:

There is presently an agreement in this respect

with the Louisville Urban League. Also, pursuant

to EEOC guidelines, an affirmative action program

for minority recruitment is presently being drafted.

★ ★ *

The thrust of the program will be active

minority recruitment; it is too early yet to

evaluate any results. (Defendants' Answers to

Plaintiffs' Interrogatories No. 13-14; PX 3).

Defendants now claim that they made substantial efforts

to attract minority applicants for jobs as police officers

between 1969 and 1974. See City Brief at 41; City FOF 263-87.

But the record supports their prior admission that they did not;

until defendants were sued, virtually all significant minority

recruiting was done by the Urban League and by the plaintiff

Louisville Black Police Officers Organization. Coleman, Vol. IV,

9/29/77 at 614-15, 623. See Plaintiffs' FOF 22.

3

Defendants' attempt to take credit for the Urban League's

recruitment efforts and advertising (City FOF 267, 284) is

refuted by the record. See Hughes, Vol. I, 3/9/77 at 130-31,

4/

137-44; Holt, Vol. II, 3/10/77 at 402-403. And, contrary to

defendants' assertion that three black officers were "actively

involved" in minority recruitment on behalf of the Police Depart

ment (City FOF 283), the record shows that Officer Lyons was

assigned in late 1973 to Major Johnson and Sergeant Walters, that

they shot films of him walking two beats and made some posters,

and that this effort "ended in early '74, didn't last too long."

Lyons, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 652. Major Johnson "made a couple of

trips out of town to college campuses ...." Ponder, Vol. I,

3/8/77 at 71. This entire effort, such as it was, took place only

after plaintiffs had filed charges of discrimination with the EEOC.

See Plaintiffs' FOF 55, 57; Ponder, Vol. I, 3/8/77 at 72.

Defendants claim that the Civil Service "encouraged the

efforts of the Urban League during this time and did everything

it could to assist in those efforts" (City FOF 269). But this

and other factual assertions based on the testimony of Jack

Richmond (City FOF 262-66, 269-71, 282) are entitled to no weight

whatsoever. Richmond, the Director of Civil Service from 1965

through late 1974, repeatedly contradicted himself in sworn state

ments concerning the numbers of applicants for jobs as police

officers between 1965 and 1972 (compare Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at

87-88, 102-103, 5/23/77 at 210 and City FOF 264, 282 with PX 5,

£/ Other radio and television advertising claimed by defendants

(City Brief at 41, citing City FOF 298, 327-28, 345) did not

begin until 1974.

4

Defendants' Answer to Interrogatory No. 19(i) ); concerning the

issue of how many applicants failed the written tests (compare

Richmond Dep., 5/23/77 at 226-27 with PX 5, Defendants' Answer to

Interrogatory No. 19(i) ); and concerning the question whether his

office maintained records of the race of applicants (compare

Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 61—62 and 5/23/77 at 230 with Defendants'

Answer to Interrogatory No. 20). He also testified that applicants

who passed the oral examination were placed on a certification

list in a rank order determined by their scores on the written

examination. (Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 91-92; City FOF 25G, 424).

But Jerry Lee, an employee in Richmond's office since 1964,

testified that before 1975 there were no official eligibility

lists and that as applicants completed each step in the selection

process they "got closer and closer to the front of the drawer"

until they were given an oral examination, after which they were

appointed. Lee, Vol. II, 6/21/77 at 260-67. See also, Coleman,

Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 629; Arnold, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 767.

Contrary to Richmond's testimony and defendants' asser

tions, the record shows that Richmond was asked and refused to

assist the Urban League in recruiting black applicants. Arnold,

Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 771. The testimony not only of plaintiffs'

witnesses but also of the former Director of Safety, James

Thornberry, establishes that Richmond was biased against blacks

and that he put his personal prejudice into effect in excluding

blacks from the Louisville Division of Police. Thornberry, Vol.

Ill, 6/22/77 at 409-413; Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 634-35;

Arnold, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 771. See Plaintiffs' Brief at 30-32.

5

3. Misstatements and Errors on Tests and Test Validation

Defendants have displayed a pattern of misrepresenting

the testimony of plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Richard Barrett, con

cerning the validity of Test 165.1. See p. 63 n.67, p. 65 n.69 ,

and p. 79 n.82, infra. They have erroneously claimed that

Examination No. 0044 did not have an adverse impact on blacks (p. 48

n.50 , infra); that there was empirical evidence demonstrating a

relationship between the abilities purportedly measured by Test

165.1 and the job performance of police officers (p. 62 n.65,

infra); that they conducted a local content validation study of

Test 165.1 (p. 66 n.73 , infra); that their expert Terry Talbert

regarded Test 165.1 as the best police officer test he had

seen (p. 80 n.83, infra). They have made self-contradictory

statements as to whether or not they are asserting construct

validity (pp. 58-59, infra); they have given four conflicting

definitions of content validity (p. 63 and n.67, infra); and

they have variously claimed that a statistical correction for

racial bias was made at two of the four concurrent validity study

sites, City Brief at 92, or only at one of the sites, City FOP

612 (p. 71 n.74, infra).

4. Contradictory Statements

In addition to their contradictory assertions with

respect to the validity of Test 165.1, defendants have made

conflicting statements on a number of other significant issues.

For example:

(a) They variously claim that the beginning date of the

statutory liability period under Title VII is August 8 (City FOF

6

435), August 22 (City Brief at 51), and August 26, 1 972 (id. ) .

The correct date is June 1, 1972. See p. 39, infra.

(b) They state that in 1965 applicants could not

secure an application form unless they had "no felony convictions

and no more than 2 misdemeanor convictions" (City FOF 25A), but

they later admit that until 1971 persons were "automatically

disqualified for arrests ..." (icL 28). The record shows that

applicants were subject to discretionary disqualification on the

basis of arrest records even after 1971 (PX 21E, 21F). See

Plaintiffs' Brief at 21; Plaintiffs' Supplemental Post-Trial

Brief.

(c) They assert that they abandoned specific height

and weight requirements in 1975 (City FOF 34, 79), yet they claim

that Sandra Richardson and Ora Seay were disqualified in October

1975 because their weight was too great for their height. See

Plaintiffs' Brief at 44-45.

(d) Defendants claim in their brief that a total of

197 police officers were appointed between July 1973 and January

1977, of whom 35 (or 17.7%) were black (City Brief at 52). But

In DX 63 (cited in City FOF 421 and 439) they state that a total

of 243 police officers, of whom 43 were black, were appointed

during this same period. The record shows that a total of 261

officers were appointed during this period, and that 37 of them

(14.2%) were black. See p. 36 and p. 44 n.49, infra.

(e) Defendants state that "no person has been hired

to begin police recruit school from among the Louisville police

officer applicants who were administered Test 165.1 in January of

1977" and that "[n]o police recruit training classes have been

7

held since December of 1 976" (City FOF 459; see also, _id. 91-92).

But they also claim that ”[i]n 1977, the last person selected

from the eligibility list in effect after the MPOE examination

was number 48" (City FOF 442; see also, _id. 412; City Brief at

49). In fact, a total of 53 whites and one black were selected

in 1977 from the eligibility list reflecting applicants' scores

on Test 165.1 (75%) and an oral examination (25%). see p. 36

and n.37, infra.

B. Defendants Have Made Many Errors of Law.

5/

Defendants and intervening defendants have also made

many errors and misstatements of law which are discussed in the

following sections of this reply brief. Defendants have erred in

arguing that the Title VII effect rule is unconstitutional

as applied to state and local government employers and in arguing

that proof of discriminatory intent is required under § 1981.

(Section II.) They have misconstrued the decision in Hazelwood

School District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977), and then

have relied on their misconstruction both in attacking plain-

5/ The intervening defendants raise two issues which this

Court has decided before: whether there is a proper class repre

sentative (FOP Brief at 1-8) and whether the Court has jurisdic

tion over plaintiffs' Title VII claims (i_d. at 9-13). The Court

has rejected the arguments of defendants and intervening defen

dants on these issues in the past. See Orders of June 27, 1975;

Jan. 28, 1976; March 8, 1977 (oral order); April 22, 1977. The

Court should reject these arguments again. See Plaintiffs'

Memorandum in Response to Defendants' Renewed Joint Motion to

Dismiss Title VII Claims and in Response to Other Motions to

Dismiss Title VII Claims, dated March 8, 1977; Memorandum of

Plaintiffs in Opposition to Defendants' "Renewed Motion to

Decertify Class," dated Oct. 12, 1977.

8

tiffs' prima facie case of discrimination and in attempting to

rebut it. (Section III A and B.) They have applied the incorrect

legal standard to plaintiffs' proof of arbitrary, subjective, and

discriminatory treatment of black applicants. (Section III

B(3).) On the one hand, they have erroneously rejected the

applicable federal guidelines and professional standards on

employee selection procedures and test validation, while on the

other they have misapplied those guidelines and standards in

^^9uing that Test 165. 1 is valid. (Section IV. ) The intervening

defendants have applied an erroneous legal standard to the

question whether plaintiffs are entitled to an interim award of

6/

counsel fees. (Section V.)

The evidence demonstrates the following violations

of the rights of the plaintiffs and the classes they represent:

(1) A conspicuous and longstanding pattern of inten

tional discrimination against blacks in recruitment, testing,

selection, and hiring for jobs as police officers, in violation

of Title VII, § 1981, and § 1983 and the Fourteenth Amendment.

See Plaintiffs' Brief at 11-45; sectipn III, infra.

(2) The disproportionate exclusion of blacks from the

police force by the use of selection procedures and criteria

which are not related to job performance — including unvalidated

written tests, juvenile and adult arrest records, maximum weight

standards,and financial status — in violation of Title VII and

§ 1981. See Plaintiffs' Brief at 19-25, 40-41.

W The City defendants have not presented any argument on this

question or on the other forms of relief requested by plaintiffs.

See Plaintiffs' Brief at 104-120; Plaintiffs' Proposed Order and Judgment.

9

(3) The use of Test 165.1 in a manner which has an

extreme adverse impact on black applicants and does not validly

measure their qualifications for the job, in violation of Title

VII and § 1981. See Plaintifs' Brief at 46-103; section IV, infra.

In order to remedy these violations, the Court has the power

and the duty to require the defendants to hire qualified blacks

as police officers on an accelerated basis until the effects

of defendants' past discrimination have been eliminated. See

Plaintiffs' Brief at 104-117. Once the Court determines that

defendants have engaged in unlawful discrimination, plaintiffs

should also be granted an interim award of counsel fees. See

Plaintiffs' Brief at 118-20; section V, infra.

II. PLAINTIFFS ARE NOT REQUIRED TO PROVE INTENTIONAL

RACIAL DISCRIMINATION TO ESTABLISH A VIOLATION

OF EITHER TITLE VII OR SECTION 1981.

While proof of a racially discriminatory intent or purpose

is necessary to show a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's

Equal Protection Clause and of 42 U.S.C. § 1983, such proof is

not a prerequisite for establishing a violation of either Title

VII or 42 U.S.C. § 1981. See Plaintiffs' Brief at 6-10. Under

the latter statutes, a prima facie case may be established by

evidence that facially neutral practices have a disproportionate

racial impact; the burden then shifts to the employer to prove

7/

that the practices are job related. Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

!_ / If the employer meets this burden, the plaintiff may show

that other selection devices without a similar discriminatory

effect would also serve the employer's legitimate interests.

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 329 (1977); Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 425 (1975).

1 0

401 U.S. 424, 431-32 (1971) (Title VII); Davis v. County of Los

Anqeles, 566 F.2d 1334, 1338-40 (9th Cir. 1977), vacated as moot,

8/

47 O.S.L.W. 4317 (March 27, 1979) (§ 1981).

Defendants concede that, at least under Title VII, "[a]n

unrebutted prima facie case can ... result in a final judgment

for the plaintiff in the absence of an actual finding of discrimi-

9/

natory intent." City Brief at 3. But they contend that

Title VII as interpreted by Griggs cannot constitutionally be

applied to public employers, and that proof of a discriminatory

motive is required to show a violation of § 1981. Defendants are

wrong on both counts, and their arguments in any event have

little or no practical significance for this case because the

8/ While the Supreme Court majority in Davis stated that its

decision vacating the judgment of the court of appeals "deprives

that court's opinion of precedential effect," 47 U.S.L.W. at 4320

n.6, Justice Powell, joined in his dissent by the Chief Justice,

noted that the opinion of the court of appeals "will continue

to have precedential weight and, until contrary authority is

decided, is likely to be viewed as persuasive authority if not

the governing law of the Ninth Circuit," î d. at 4323 n.10.

9/ Although the quoted statement is correct, defendants

Have applied the wrong legal standard to the question of

what an employer must prove to rebut a prima facie disparate

impact case. The decisions in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973), Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters,

57 L.Ed. 2d 957 (1 978Ti and Trustees of Keene State College v.

Sweeney, 58 L.Ed. 2d 216 (1978), concern "the order and alloca

tion of proof in a private non-class action . . .," McDonnell

Douglas, 411 U.S. at 800. As the Court noted in Furnco, 57 L.Ed.

2d at 966 n.7, different principles govern the establishment and

rebuttal of a prima facie case involving, for example, employ

ment tests (Griggs and Albemarle Paper, supra), particularized

job requirements such as height and weight standards (Dothard

v. Rawlinson, supra), or a pattern or practice of discrimina

tion (International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 344, 358 (1977)). See pp. 45-47, 80-81, infral

evidence clearly establishes a pattern or practice of intentional

10/

racial discrimination.

A. The Extension of the Title VII Effect Rule

to Public Employers Was a Valid Exercise of

Congressional Power Under Both the Commerce

Clause and Section 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

In amending Title VII by enactment of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972, 86 Stat. 103, Congress intended to extend

the effect rule of Title VII to state and local government employers.

The statutory language makes no distinction between the employment

practices which are proscribed for public employers and those pro

scribed for private employers; the legislative history shows that the

statute was meant to prohibit public as well as private employers

from using invalid selection techniques which have a dispropor

tionately adverse effect on blacks. See S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d

Cong., 1st Sess. 10 (1971); H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong., 1st

Sess. 17 (1971). Defendants appear to concede that this was the

intent of Congress, but they argue that in the light of the Supreme

Court's decisions in National League of Cities v. Usery, 426

10/ Defendants' use of Test 165.1 in 1977 had an extreme adverse

impact on blacks and was not shown to be job related. See Plaintiffs'

Brief at 46-103 and section IV, infra. The record also shows that,

both before and after the filing of this lawsuit, defendants used

other written tests and selection procedures which had an adverse

impact on blacks and were not job related. See Plaintiffs' Brief at

19-25, 40-41. This evidence, standing alone, might not prove inten

tional discrimination but would prove a violation of Title VII and

§ 1981 under the standards of Griggs and County of Los Angeles v.

Davis, supra. In this one respect, therefore, the question whether

these statutes require proof of discriminatory intent may be signifi

cant. However, if this evidence is viewed, as plaintiffs contend it

should be, as part of the "totality of the relevant facts," Washington

v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976), it not only proves independent

disparate impact violations but also constitutes relevant evidence of

disparate treatment. See Teamsters, suora, 431 U.S. at 335 n.15.

U.S. 833 (1976), and Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976),

Congress did not have the power to effectuate its intent

under either the Commerce Clause, Art. I, § 8, cl. 3 of the

Constitution, or Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. See City

Brief at 4-13. Defendants have overdrawn the scope of National

League of Cities and the impact of Washington v. Davis. Both

the Commerce Clause and the Fourteenth Amendment support Title

VII as amended in 1972.

1• The Commerce Clause

National League of Cities established that Congress

does not have the same unfettered control over state and local

government activities affecting interstate commerce that it has

over private business, and that a statute proper as to private

industry may be invalidated if it interferes excessively with the

"integral governmental functions" of states or cities. 426 U.S.

at 851. The constitutionality of such legislation depends upon

"the degree of intrusion upon the protected area of state

sovereignty" and the extent to which its object is, as a legal or

practical matter, an area of substantial federal interest. Id.

at 852-53. Contrary to defendants' contentions, the

Jja.tlQnal League of Cities does not indiscriminately bar

all federal legislation enacted pursuant to the Commerce

Clause that would regulate state agencies in their role

as employers. The Court specifically declined to overrule

Fry v. United States, 421 U.S. 542 (1975) (sustaining

congressional power to apply a wage freeze to employees

of state government); Parden v. Terminal Railway Co., 377

U.S 184 (1964) (sustaining congressional power"to apoly

the Federal Employers Liability Act to state-owned rall-

r°ads)? P.aM fornia v. Taylor, 353 U.S. 553 (1 957) (sustainina

congressional power to apply the Railway Labor Act to state-'

( m V f c lr?adSh' °r United States v. California. 297 U.S. 175 io) (sustaining congressional power to apply "the Safety

Appliance Act to state—owned railroads).

13

federal interest in protecting racial minorities is well estab

lished in our constitutional system, and it transcends the type

of concern at issue in National League of Cities. Conformity

with Title VII's effect rule, unlike the minimum wage in National

League of Cities, will not increase the payroll costs of complying

jurisdictions. Since Title VII prohibits selection practices

which have an adverse impact and are not job related, compliance

will not interfere with any legitimate state or local policies

and may well contribute significantly to the efficacy of defendants'

personnel methods.

2. Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment

Defendants suggest that the issue here is whether

"the federal government [may] require the City of Louisville

to validate its police officer applicant examinations in one of

the particular ways described in the Federal Guidelines before

it may recruit and hire more police officers." City Brief

at 9. This statement of the issue is grossly misleading, since

the legal obligation to validate a selection procedure arises

only when that procedure has an adverse impact on a racial,

sex, or ethnic group. See Plaintiffs' Brief at 46-47. Indeed,

the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, 43 Fed.

Reg. 38290 (Aug. 25, 1978) (see section IV, infra), specifically

authorize employers to eliminate the adverse impact of their

procedures as an alternative to demonstrating the validity of

those procedures. Uniform Guidelines, § 6A; Questions and

Answers on the Uniform Guidelines, 44 Fed. Reg. 1 1996, II 31

(March 2, 1979). See pp. 83-84, infra.

- 14 -

The real issue is whether Congress acted within the scope of

its Fourteenth Amendment enforcement power when it provided in

Title VII that public employers may not use tests and other

selection practices which have an adverse imDact on blacks unless

12/

those practices are shown to be job related. Defendants

correctly recognize (City Brief at 9 n.2) that Congress can and

did exercise its Fourteenth Amendment power to prohibit racial

discrimination in state and local government employment. See

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976). They also recognize

(City Brief at 9-10) that Congress, acting under § 5 of the

Fourteenth Amendment, has the authority to prohibit conduct which

is not forbidden by the Washington v. Davis interpretation of § 1

of the Amendment? the test is whether the statute "may be regarded

as an enactment to enforce the Equal Protection Clause, whether

it is 'plainly adapted to that end' and whether it is not pro

hibited by but is consistent with 'the letter and spirit of the

Constitution.'" Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S 641, 651 (1966)

(footnote omitted). Compare Lassiter v. Northampton Election

Board, 360 U.S. 45 (1959), with South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383

U.S. 301 (1966); Katzenbach v. Morgan, supra; and Oreqon v.11/Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970). Defendants' contention,

12/ Contrary to defendants' claim, in neither Hazelwood School

District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977), nor Dothard v.

Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 3 21 0 977), did the Court allude to this as

an "open issue." City Brief at 5. In both cases, the Court

merely noted that the issue was not presented. Hazelwood at

306-307 n.12; Dothard at 323 n.1.

13/ Lassiter held that, in the absence of proof of discrimina

tory purpose or administration, North Carolina's literacy test

for voter registration did not violate either the Fourteenth

15

then, must be that the extension of the Title VII effect rule to

state and local governments does not satisfy this standard.

Defendants are wrong as a matter of constitutional law.

It is undisputed that Congress extended the effect rule to

public employers in order to enforce the Equal Protection

Clause. Congress found that it was necessary to prohibit "both

institutional and overt discriminatory practices" by state and

local governments, S. Rep. No. 92-415, supra at 10; H. R. Rep.

14/

No. 92-238, supra at 17; and Congress was aware that

13/ cont'd.

or the Fifteenth Amendment. Congress subsequently enacted

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 4(a) of which suspended all

literacy tests in the areas covered by the Act based upon evi

dence of discriminatory purpose or motivation in some areas,

while § 4(e) prohibited the use of English literacy requirements

as a condition of voting for certain persons educated in Puerto

Rico. 79 Stat. 438. South Carolina v. Katzenbach upheld § 4(a) a

appropriate legislation to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment, and

Katzenbach v. Morgan upheld § 4(e) as appropriate legislation

to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment.

The ban on literary tests was extended nationwide by § 201

of the Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1970, 84 Stat. 315, 42

U.S.C. § 1973a, under which no state or political subdivision

is permitted to use a literacy test even though it has never

discriminated in voting in the past and has never used such a

test in a discriminatory manner or with a discriminatory purpose

Oregon v. Mitchell upheld this section as appropriate legisla

tion to enforce both the Fourteenth and the Fifteenth Amendments

14/ Both congressional committee reports relied on findings

of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in For All The People

. . .By All The People (1969), indicating "that widespread

discrimination against minorities exists in State and local

government employment, and that the existence of this discrimina

tion is perpetuated by the presence of both institutional and

overt discriminatory practices. The report cites widespread

perpetuation of past discriminatory practices through de facto

segregated job ladders, invalid selection techniques, and

stereotyped misconceptions by supervisors regarding minority

1 6

"[b]arriers to equal employment are greater in police and

fire departments than in any other area of State and local

government," 118 Cong. Rec. 790 (1972), reprinting excerpts

from U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, For All The People ...

11/By All The People at 71 (1969). See Plaintiffs' Brief at

108-109. Application of the Griggs rule was plainly adapted to

the solution of this problem, it was not prohibited by any

provision of the Constitution, and it was consistent with the

11/Fourteenth Amendment. Although Congress might have chosen

14/ cont'd.

group capabilities. The study also indicates that employment

discrimination in State and local governments is more pervasive

than in the private sector." H. R. Rep. No. 92-238, at 17.

See also, S. Rep. No. 92-415, at 10.

15/ Congress was also aware of the Commission's findings

that "Negroes are not employed in significant numbers in police

. . . departments"; that "Negro policemen . . . hold almost

no positions in the officer ranks"; and that police departments

"have discouraged minority persons from joining their ranks by

failure to recruit effectively and by permitting unequal treat

ment on the job including unequal promotional opportunities,

discriminatory job assignments, and harassment by fellow

workers." 118 Cong. Rec. 790 (1972).

16/ Congress could properly conclude that, in many cases in

which an employer uses a test or other device which excludes

disproportionate numbers of blacks or other minorities, but

which is not in fact job related, the employer is intentionally

using that procedure to discriminate. Since many tests and

other selection procedures have an adverse impact on minorities

because of inadequate education, Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at

430, and since that inadequate education is often itself due to

past racial or other discrimination by state and local govern

ments, Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969), the

use of such procedures by a state or local government will

involve a problem of past intentional discrimination not appli

cable to private employers. Congress, rather than requiring

detailed proof that a selection procedure fell into one of

these categories of unconstitutional action, could reasonably

establish a simple rule prohibiting the use of such procedures

17

an enforcement mechanism which balanced the conflicting interests

in a different way, "[i]t is not for [the Court] to review the

congressional resolution of these factors. It is enough that

[the Court] be able to perceive a basis upon which the Congress

might resolve the conflict as it did." Katzenbach v. Morgan,

11/supra, 384 U.S. at 653.

16/ cont'd.

if they were not job related. Title VII, viewed in this light,

falls within the general rule that "the inclusion of a reason

able margin to insure effective enforcement will not put upon

a law, otherwise valid, the stamp of invalidity." Euclid v.

Ambler Realty, 272 U.S. 365, 388-89 (1926). This rule clearly

applies to the congressional Fourteenth Amendment enforcement

power. See Orloski, The Enforcement Clauses of the Civil War

Amendments: A Repository of Legislative Power, 49 St. John' s

L. Rev. 493, 506-507 (1975); Yackle, The Burger Court, "State

Action," and Congressional Enforcement of the Civil War Amendments,

27 Ala. L. Rev. 479, 562-66 (1975); Cohen, Congressional Power

To Interpret Due Process and Equal Protection, 27 Stan. Li Rev.

603, 613-16 (1975); Note, Federal Power To Regulate Private

Discrimination: The Revival of the Enforcement Clauses of the

Reconstruction Era Amendments, 74 Colum. Li Rev. 449, 505-510

(1974).

17/ Defendants' attempt to distinguish Katzenbach v. Morgan

(City Brief at 11-13) is unpersuasive. In extending the Title

VII effect rule, as in enacting the statutes prohibiting literacy

tests for voter registration which the Court upheld in Morgan,

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, and Oregon v. Mitchell, supra, Con

gress properly applied the prohibition across the board, without

regard to whether a particular state or local government had

previously used any tests or devices in a discriminatory manner

or with a discriminatory purpose; Congress specifically determined

that the Griggs rule should be extended; Congress sought to

eliminate employment discrimination "in those government activi

ties which are most visible to the minority communities (notably

education, law enforcement, and the administration of justice)

...," H. R. Rep. No. 92-238, supra at 17, where the exclusion of

minorities "not only promotes ignorance of minority problems in

the particular community, but also creates mistrust, alienation,

and all too often hostility toward the entire process of government,"

S. Rep. No. 92-415, supra at 10; Congress recognized that states

and cities have no greater need for employment tests which do not

predict job performance than for literacy tests which do not

18

This basis clearly is present here. As a number of courts

have recognized, the extension of the Title VII effect rule to state

and local government employers was a proper exercise of congres

sional power under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. United

States v. City of Chicago, 573 F.2d 416, 422-24 (7th Cir. 1978);

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. City of St. Louis,

549 F .2d 506, 510 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 819 (1977);

Harrington v. Vandalia-Butler Board of Education, 418 F. Supp.

603, 607 (S.D. Ohio 1976); Jones v. Milwaukee County, 13 FEP

Cases 307, 309 (E.D. Wis. 1976).

B. Evidence of Discriminatory Intent Is Not

Required To Prove a Violation of Section 1981.

Defendants have mischaracterized this issue as "whether the

extension of Title VII to governmental agencies . . . implicitly

amended Section 1981." City Brief at 17. The Supreme Court has

held that these two statutory remedies for employment discrimi

nation, "although related, and although directed to most of the

17/ cont'd.

guarantee an informed and intelligent electorate; Congress did

not impose an unnecessary administrative burden on public employers

but merely required them to show that their selection procedures

are valid if they insist on using procedures with an adverse

impact on minorities (an option which was not available under the

flat prohibitions of literacy tests for voter registration); and

Congress ratified the use of race-conscious remedies for employment

discrimination which sometimes operate to upset the expectations of

whites hoping to benefit from a continuation of discriminatory

practices, just as it has approved the use of race-conscious re

districting plans which deprive whites of bloc voting strength, see

Regents of the University of California v. 3akke, 438 U.S. 265,

353-54 n.28, 366 n.41 (1978) (opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall,

and Blackmun, JJ. ) .

19

same ends, are separate, distinct, and independent." Johnson v.

Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454, 461 (1975). Thus,

the real question is whether § 1981 itself should be construed

18/

as requiring proof of discriminatory intent.

Defendants appear to concede that the present answer in this

circuit is that of Long v. Ford Motor Company: A prima facie viola

tion of § 1981 may be established by proof of either disparate treat

ment or disparate impact. 496 F.2d 500, 506 (6th Cir. 1974).

See City Brief at 17-18. The language and history of § 1981

indicate that this answer is correct. See Brief Amicus Curiae

for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., in

County of Los Angeles v. Davis, No. 77-1553, at 9-37 (attached

19/

hereto as Appendix A).

Section 1981 was originally enacted as § 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27. The language of § 1 of the

18/ Contrary to defendants' contention (City Brief at 15-16),

neither the Supreme Court nor the Seventh Circuit decided this

question sub silentio in Village of Arlington Heights v.Metro

politan Housing Development Corp.̂ 429 U.S. 252 (1977), on

remand, 558 F .2d 1283 (7th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

1025 Cl 978). As the Supreme Court stated in County of Los

Angeles v. Davis, 47 U.S.L.W. 4317, 4318 (March 27, 1979), it

had granted certiorari in that case for the express purpose of

determining "whether the use of arbitrary employment criteria,

racially exclusionary in operation, but not purposefully dis

criminatory, violate [sic] 42 U.S.C. § 1981 . . . " Had the Court

decided this question in Arlington Heights, there would have

been no need to address it in Davis. The Court ultimately did

not decide the issue in Davis because it found that the case had

become moot. 47 U.S.L.W. at 4319-20.

19/ Because the Court adopted the argument in section I of this

amicus brief that the case had become moot, see County of Los

Angeles v. Davis, supra, 47 U.S.L.W. at 4319, 4322, the Court did

not reach the issues discussed in section II concerning the

interpretation of § 1981.

20

1866 Act, unlike the language of § 2 and of some other con

temporary statutes, was not limited to cases of intentional

discrimination; rather, it provided that all "citizens, of

every race and color, without regard to any previous condition

of slavery or involuntary servitude . . . shall have the same

right . . . to make and enforce contracts . . . as is enjoyed

by white citizens." Appendix A at 14-15. When this provision

was enacted in 1866, and when it was re-enacted in 1870 to ex

pand the group protected from "citizens of the United States"

to "all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States,"

Congress intended the protection of the statute to be broader

than that of the Fourteenth Amendment in a number of respects.

Id♦ at 10-11. Indeed, the one undisputed goal of the Civil

Rights Act was to abrogate the oppressive "Black Codes" of the

post-Civil War South, many of which were racially neutral on

their face but discriminatory in their effect — ■ a consequence

of the drastically different social, educational, and economic

status of blacks and whites, which was in turn rooted in the

history of slavery and discrimination. Id_. at 15-29. Practices

in the 1970s, such as the use of non-job related employment

tests which have the same negative impact on blacks for sub

stantially the same reasons as the practices of the 1870s, are

not insulated from the reach of § 1981 by the mete passage of

time. See _id_. at 29-37. Plaintiffs thus submit that § 1981,

properly construed, prohibits employment practices which are

discriminatory in effect and unrelated to job performance. See

cases cited in Plaintiffs' Brief at 10.

21

C . The Record Shows, in any Event, that Defendants

Engaged in Intentional Discrimination.

Contrary to defendants' argument (City Brief at 22-24),

not only would the record in this case support a finding of

intentional discrimination, but a finding that defendants had

not engaged in intentional discrimination would be clearly

erroneous. The statistical evidence of the exclusion of blacks,

which itself is overwhelming, is buttressed by evidence showing

the segregationist history of defendants' police employment

2 0/

practices, purposeful discrimination in recruitment and

selection practices at least until the filing of this action in

1974, use of tests and other selection procedures both before

and after 1974 which adversely affected blacks and were not job

related, and numerous instances in which black applicants were

subjected to unexplained delays and were disqualified on the

basis of arbitrary, subjective, and discriminatory criteria.

See Plaintiffs' Brief at 11-103 and section III, infra. Thus,

even if Title VII and § 1981 could be construed as requiring

proof of discriminatory intent, those requirements would be

satisfied here. Cf. Hazelwood School District v. United States,

supra, 433 U.S. at 306-307 n.12.

20/ This fact alone is sufficient to distinguish this case from

Richardson v. McFadden, 540 F.2d 744 (4th Cir. 1976). See City

Brief at 23-24. There the court found no intentional discrimina

tion in the administration of the South Carolina bar examination,

noting that it was "perhaps of controlling importance" that there

had never been laws or rules of court prohibiting blacks from

practicing law in the state or imposing different standards on

blacks than on whites. Id. at 747. Moreover, the court found

it "statistically clear tnat admission to the State's Bar has

been relatively open to blacks . . . " I_d. Here the statistical

picture is equally clear, but what it shows is that the City's

police force has been closed to all but a handful of blacks

for the last 40 years.

22

III. PLAINTIFFS HAVE ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE

CASE OF INTENTIONAL DISCRIMINATION WHICH

DEFENDANTS HAVE FAILED TO REBUT.

Defendants, misconstruing both the plaintiffs' arguments

and the Supreme Court's decisions in International Brotherhood

of Teamsters v. United States and Hazelwood School District v.

United States, supra, contend that plaintiffs have failed to

establish a prima facie case "even under the rule of Griggs."

City Brief at 26, 46. Defendants apparently do not understand

that the Teamsters and Hazelwood decisions concern the order

and allocation of proof in cases alleging a pattern or practice

of intentional "disparate treatment" based on race, not in

cases involving non-racially motivated "disparate impact" such

as Griggs. See Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 335 and n.15; Hazelwood,

433 U.S. at 306-307 n.12. Plaintiffs submit that the record

here establishes a clear disparate impact violation; but, like

the Government in Teamsters and Hazelwood, plaintiffs submit that

the evidence also establishes disparate treatment by showing that

the defendants "regularly and purposefully treated Negroes ...

less favorably than white persons." Hazelwood, supra at 307

n.12; Teamsters, supra at 335. See Plaintiffs' Brief at 8-9,

11-45. Contrary to defendants' arguments, plaintiffs have

satisfied the standards of these decisions for establishing

a prima facie case of intentional and purposeful discrimination

against blacks, and defendants have failed to rebut this prima

facie case.

23

A. Plaintiffs Have Established a Prima Facie

Case of Intentional Discrimination.

1. Defendants have misconstrued Hazelwood.

Defendants have conceded that under Teamsters "it

is ordinarily to be expected that nondiscriminatory hiring

practices will in time result in a work force more or less

representative of the racial and ethnic composition of the

population in the community from which employees are hired,"

and that ”[e]vidence of longlasting and gross disparity between

the composition of a work force and that of the general popula-

11/tion thus may be significant 431 U.S. at 340 n.20.

City Brief at 27. But defendants have badly misconstrued the

Hazelwood decision and then have relied on their misconstruction

to argue that plaintiffs have not established a prima facie case.

See City Brief at 28-30, 48, 51.

The Government in Hazelwood brought a Title VII

action alleging a pattern or practice of racial discrimination in

the hiring of school teachers by a suburban St. Louis school

district. The Government there, like the plaintiffs here,

adduced evidence of (1) a history of racially discriminatory

practices, (2) statistical disparities in hiring, (3) standardless

21/ Defendants seek to distinguish Teamsters on the ground

that the Court there was faced with a case of "the inexorable

zero" in which no blacks had been hired in a particular job

classification. City Brief at 27 n.8. This, on the other

hand, appears to be a case of "the inexorable two"; although

between 15 and 82 new white officers were accepted into police

recruit school classes which graduated in each year from 1964

until the year this lawsuit was filed, no more than two new

black officers were ever allowed in recruit school classes

which graduated in any of those years. See Plaintiffs' FOF 8.

24

and subjective hiring procedures, and (4) specific instances of

22/

discrimination against black applicants. 433 U.S. at 303. The

district court found this evidence insufficient to establish

a prima facie violation of Title VII, holding inter alia that

there was not a substantial disparity between the percentage

of black teachers and the percentage of black students in

23/

the school district. Ld. at 304. The Eighth Circuit

reversed. Id_. at 304-306. It rejected the trial court's

comparison of black teachers to black students and held

instead that the proper comparison was between black teachers

employed by Hazelwood and black teachers in the relevant

labor market area, which the appellate court found to be St.

Louis County and St. Louis City taken together. Id. at 305.

22/ Plaintiffs here, unlike the Government in Hazelwood, also

adduced evidence that the defendants used selection procedures

which had an adverse impact on blacks and were not job-related.

See Plaintiffs' Brief at 19-25, 40-41, 46-103. This evidence

not only provides additional proof of intentional discrimina

tion, see Washington v. Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 253

(Stevens, J., concurring), but also establishes an independent

"disparate impact” violation of Title VII which is not con

ditioned upon any proof of racially motivated discrimination,

Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 335 n.15.

23/ Defendants erroneously state that the district court

ruled "that plaintiffs had established a prima facie case of

employment discrimination by demonstrating that there was a

substantial discrepancy between the black participation rate in

Hazelwood's teacher work force and the district's black student

population." City Brief at 28. In fact, the district court

found that "statistics showing that relatively small numbers of

Negroes were employed as teachers were ... nonprobative, on the

ground that the percentage of Negro pupils in Hazelwood was

similarly small." 433 U.S. at 304.

25

The substantial disparity oetween the percentage of black

teachers in this area and the percentage of black teachers

on Hazelwood's staff, together with the evidence showing the

school district's history of discrimination, its subjective

hiring procedures, and instances of discrimination against

individual black applicants, established a prima facie case

which the school district had failed to rebut. The court of

appeals therefore directed judgment for the Government. Id.

at 305-306.

On certiorari, the question addressed by the Supreme Court

was not whether a prima facie case had been established but

whether the court of appeals had improperly relied upon "undif

ferentiated work force statistics to find an unrebutted prima

facie case of employment discrimination." Id_. at 306 (emphasis

added). Neither Hazelwood nor any of the other Title VII cases

cited by defendants (City Brief at 46-48) holds that statistics

showing the racial composition of an employer's work force must

be disregarded merely because those statistics reflect pre-Act as

well as post-Act employment decisions. In Evans v. United Air

Lines, Inc. , 431 U.S. 554 (1 977), the Court simply held that a

charge of discrimination must be filed with the EEOC within the

statutory period following the occurrence of a violation; it is

undisputed that this requirement was satisfied here. See Plain

tiffs' FOF 55-57. In Hazelwood, the Supreme Court specifically

approved the view of the court of appeals that, for the purpose

of establishing a prima facie case, "a proper comparison was

between the racial composition of Hazelwood's teaching staff and

the racial composition of the qualified public school teacher

26

population in the relevant labor market." Id. at 303 (footnote

omitted). A number of defendants' other cases also expressly

hold that work force statistics reflecting the results of both

pre- and post-Act employment decisions may properly be con

sidered in determining the existence of a prima facie case.

See Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 340 n.20; Friend v. Leidinger, 446 F.

Supp. 361 , 368 (E.D. Va. 1 977), aff 'd, 588 F .2d 61 (4th Cir.

1978); Detroit Police Officers Association v. Young, 446 F. Supp.

979, 996 (E.D. Mich. 1978).

In deciding whether a prima facie case had been established,

there was no need for the Court in Hazelwood to choose between

the 15.4% comparison figure suggested by the Government and the

5.7% figure urged by the employer; "even assuming, arguendo, that

the 5.7% figure ... is correct, the disparity between that figure

and the percentage of Negroes on Hazelwood's teaching staff would

be more than fourfold for the 1972-1973 school year, and threefold

for the 1973-1974 school year." 433 U.S. at 309 n.14. The

significance of this disparity was confirmed by the statistical

analysis explained in Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 496-97

n.17 (1977). See Plaintiffs' Brief at 16-17.

Thus, the court of appeals in Hazelwood had correctly

held that the evidence established a prima facie case of

intentional discrimination, but it had erred in disregarding

"the possibility that this prima facie statistical proof in

the record might at the trial court level be rebutted by

statistics dealing with Hazelwood's hiring after it be

came subject to Title VII." 433 U.S. at 309. As the Supreme

27

Court noted, the selection of the relevant labor market area

might well have a bearing on the strength of the defendant's

rebuttal evidence. Id. at 310-11 and n.17. In addition, the

defendant could come forward with post-Act applicant flow

data. _Id. at 310, 313 n.21; see also i_a. at 314 (Brennan, J. ,

concurring). The case therefore was remanded to give the

employer an opportunity to rebut the Government's prima facie

case by showing that "the claimed discriminatory pattern is a

product of pre-Act hiring rather than unlawful post-Act dis

crimination." Id. at 310; Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 360.

2. Even under defendants' theory of the

relevant labor market, plaintiffs have

established a prima facie case.

Plaintiffs submit that the proper figure to use in

determining whether the evidence here establishes a prima

facie case, as well as in setting an appropriate goal for

affirmative hiring relief, is the general population of the

City of Louisville, which was 23.8% black in 1970. See

24/

Plaintiffs' Brief at 14-15 n.4, 107-114. But here, as

24/ Defendants' cases (see City Brief at 30-48) do not

support their argument that the only appropriate figure is the

10% black proportion of the 1970 civilian labor force in the

Louisville SMSA who were between the ages of 20 and 34 and who were

high school graduates or above in educational level. See DX 28;

Spar. Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 354-55. These cases indicate instead,

as conceded by the intervening defendants (FOP Brief at 42),

that courts have compared the racial composition of a defendant's

membership or work force to the racial composition of a wide

variety of arguably relevant populations. See, e.g., United

States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544, 551 and n.19.

(9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971) (city which has

the single largest population within unions' jurisdiction and

in which unions' main offices, hiring halls, and training

28

in Hazelwood, it is not necessary for the Court to choose

between the figure suggested by plaintiffs and the figure

suggested by defendants; even if defendants' 10% figure is

used, the disparity between that figure and the percentage

of blacks on the Louisville police force is so substantial

that it creates an inference of intentional discrimination.

The comparison which the Court made in Hazelwood for the

purpose of determining a prima facie case was between the

racial composition of the defendant's work force on and after

the effective date of Title VII and the racial composition

of the labor market area suggested by the defendant. 433 U.S.

at 309 n.14. If the same comparison is made here, it reveals a

25/disparity of 3.1 standard deviations as of January 1, 1970,

between the actual number of black officers on the Louisville

24/ cont'd.

facilities are located); EEOC v. Local 14, Operating Engineers,

553 F.2d 251, 254 (2d Cir. 1977) (labor pool in the region from

which unions draw their members); Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co.,

365 F. Supp. 87, 111 (E.D. Mich. 1973), aff'd in pertinent part

sub nom EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F .2d 301 (6tn Cir.

1975), vac'd and rem'd on other grounds, 431 U.S. 951 (1977)

(area from whieh employees are drawn); Friend v. Leidinger,

supra, 446 F. Supp. at 368 (general population of the SMSA);

Detroit Police Officers Association v. Young, supra, 446 F.

Supp. at 994-96 (E.D. Mich. 1978) (persons possessing minimum

requirements and residing in tri-county area in which the bulk

of all applicants are found); Smith v. Union Oil Co., 17 FEP

Cases 960, 967-68 (N.D. Cal. 1977) (court finds it appropriate

to consider three different figures: clerical SMSA labor force,

overall SMSA labor force, and weighted overall SMSA labor force).

See also, cases cited in Plaintiffs' Brief at 14-15 n.4; FOP

Brief at 42-48.

25/ Under the applicable statute of limitations, KRS § 413.120,

defendants here are liable for violations of §§ 1981 and 1983 and

the Fourteenth Amendment occurring on and after March 14, 1969.

See City COL 666.

29

police force (39) and the number one would expect to find on the

force as the result of nondiscriminatory hiring practices (62).

See Plaintifs' FOF 6. Castaneda v. Partida, supra, 430 U.S. at

26/

496-97 n.17. The disparity in 1970 was even greater in com

parison to the black proportion of the population of either Jefferson

County or the City of Louisville. Moreover, the disparities

steadily increased in relation to all three comparison figures

from 1970 until 1974, when this lawsuit was filed, and they

remained significant even after defendants had been sued.

Because "a fluctuation of more than two or three standard

deviations would undercut the hypothesis that decisions were

being made randomly with respect to race," Hazelwood, supra,

433 U.S. at 311 n.17, these disparities indicate the existence of