Correspondence from Rodney to Quigley, Wilson, and Karlan; Motion for an Injunction Pending Appeal or, in the Alternative, for Issuance of the Mandate; Memorandum in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellants' Motion for an Injunction Pending Appeal, Or, In the Alternative, For Issuance of the Mandate

Public Court Documents

May 9, 1988

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Correspondence from Rodney to Quigley, Wilson, and Karlan; Motion for an Injunction Pending Appeal or, in the Alternative, for Issuance of the Mandate; Memorandum in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellants' Motion for an Injunction Pending Appeal, Or, In the Alternative, For Issuance of the Mandate, 1988. 53fcbd36-f211-ef11-9f89-0022482f7547. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2adb01a2-7bc9-4b91-9f00-0e564a5ad35b/correspondence-from-rodney-to-quigley-wilson-and-karlan-motion-for-an-injunction-pending-appeal-or-in-the-alternative-for-issuance-of-the-mandate-memorandum-in-support-of-plaintiffs-appellants-motion-for-an-injunction-pending-appeal-or-in-t. Accessed July 15, 2025.

Copied!

,

MdGLINCHEY, STAFFORD, MINTZ, CELLINI 8c LANG, PC

GRAHAM STAFFORD (1940-1987)

DERMOT S. McGLINCHEYM

SAMUEL LANG

DONALD R. MINTZ ,.

DANDO B. CELLINIm

D. ANDREW LANG

COLVIN G. NORWOOD, JR. M

DAVID S. WILLENZIK 111

FRANK VOELKER, JR.

FREDERICK R. CAMPBELL m

B. FRANKLIN MARTIN, III m

E. FREDRICK PREIS, JR.

HENRI WOLBRETTE, III Ill

LEOPOLD Z. SHER

WILLIAM V. DALFERES, JR. Ill

MICHAEL J. MAGINNIS III

MICHAEL T. PULASKI.

PETER L. HILBERT, JR. (I)

CONSTANCE CHARLES WILLEMS

ERNEST P. GIEGER, JR..

PAUL M. BATIZAm

MICHAEL R. SISTRUNK.

THOMAS P. ANZELMOm

STEVEN I. KLEIN (21

SANDRA MILLS FEINGERTS 121

BENNET S. KOREN

RALPH J. ZATZKIS

JAMES M. FANTACI

GARY E. MERINGER

KENNETH H. LABORDE

MAUREEN O'CONNOR SULLIVAN

SUSAN WHITTINGTON LEIDNER 121

KATHLEEN A. MANNING

J. FORREST HINTON

KENNETH A. WEISS.)

JOHN GREGORY ODOM

JAMES D. MORGAN

MICHAEL S. MITCHELL

ELWOOD F. CAHILL, JR.

MICHAEL S. GUILLORY

LANCE S. OSTENDCYRF

JAMES C. CRIGLER, JR.

SIDNEY J. HARDY

MICHAEL M. NOONAN

RICHARD P. RICHTER

DAVID ISRAEL

MARIE A. MOORE

VICTORIA KNIGHT McHENRY

RUDY J. CERONE

DEBRA FISCHMAN COTTRELL

ANTHONY ROLLO

EVE B. MASINTER

TIMOTHY P. HURLEY

GENE W. LAFITTE, JR.

STEPHEN W. RIDER

ROY J. RODNEY, JR.

ERIC SHUMAN

ARTHUR H. LEITH

DAVID L. BARNETT

STEPHEN P. BEISER

LAURA HOBSON BROWN

STEPHANIE M. LAWRENCE

LISA J. MILEY

CHRISTOPHER J. AUBERT

KATHLEEN K. CHARVET

PATRICIA A. CARTEAUX

RICHARD B. EHRET

MARK M. GLOVEN

MAUREEN L. HOGEL

ALEXANDER M. McINTYRE, JR.

RICHARD M. MOVED

LAUREN A. WELCH

CARL A. BUTLER

SHARON L. GROSS

THOMAS P. McALISTER

TRUDY RODNEY BENNETTE

SUSAN T. BROUSSARD

CYNTHIA M. CANADA

ROBERT W. MAXWELL

KRISTINA B. WEBB

FABIO M. FAGG!.

PAUL A. OBERER (3,

PATRICIA L. MANSON

CHRISTOPHER C. JOHNSTON

DAVID P. BUEHLER

MICHAEL J. OE BLANC, JR.

BROOKE DUNCAN III

KEITH W. McDANIEL

CHARLOTTE G. BORDENAVE

GERARD J. SONNIER

ELISE M. BEAUCHAMP

MARJORIE R. ESMAN

N. VICTORIA HOLLADAY

ANITA T. LECHNER

LAWRENCE B. MANDALA

SHARON D. SMITH

ROY C. BEARD

JOE GIARRUSSO, JR.

JONATHAN YOUNG

MLAW CORPORATION OBOARD CERTIFIED TAX ATTORNEY (3)NOT ADMITTED IN LOUISIANA

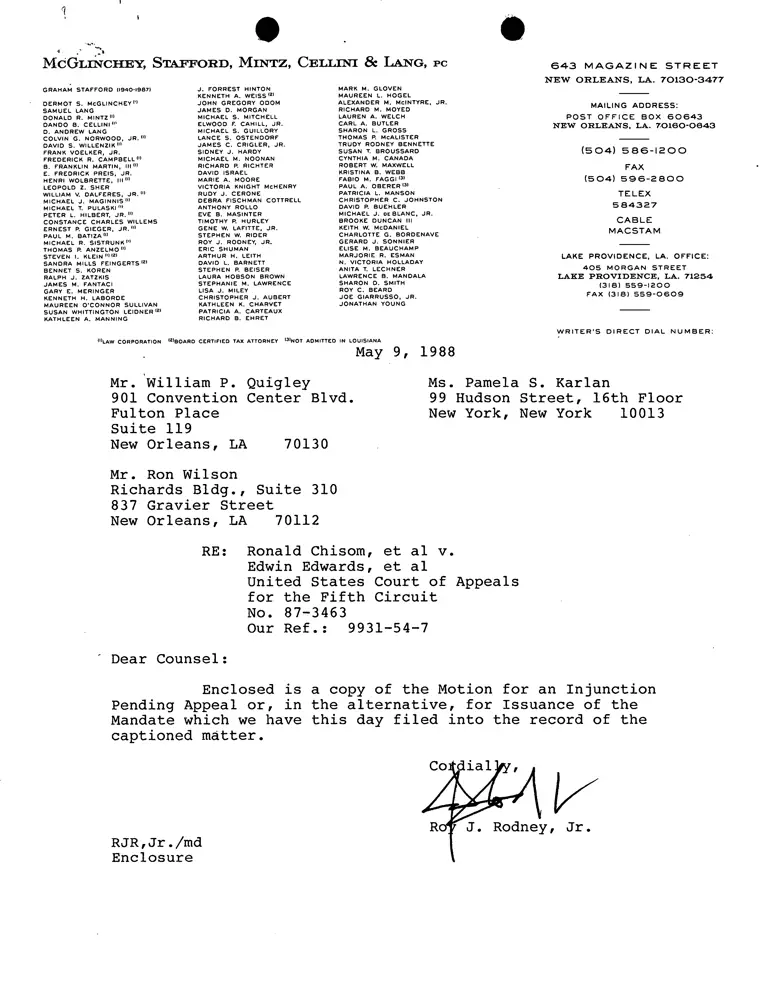

Mr. William P. Quigley

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place

Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

Mr. Ron Wilson

Richards Bldg., Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

May 9, 1988

643 MAGAZINE STREET

NEW ORLEANS, LA. 70130-3477

MAILING ADDRESS:

POST OFFICE BOX 6 0 643

NEW ORLEANS, LA. 70160-0643

(5 04) 586-1200

FAX

(504) 596-2800

TELEX

584327

CABLE

MACSTAM

LAKE PROVIDENCE, LA, OFFICE:

405 MORGAN STREET

LAKE PROVIDENCE, LA. 71254

13181 559-1200

FAX (3181 559-0609

WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL NUMBER:

Ms. Pamela S. Karlan

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

RE: Ronald Chisom, et al v.

Edwin Edwards, et al

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

No. 87-3463

Our Ref.: 9931-54-7

' Dear Counsel:

Enclosed is a copy of the Motion for an Injunction

Pending Appeal or, in the alternative, for Issuance of the

Mandate which we have this day filed into the record of the

captioned matter.

RJR,Jr./md

Enclosure

1110,

M IY1 tGLINCHEY, STAFFORD, INTZ, CELLINI & LANG, PC

Mr. William P. Quigley

Mr. Ron Wilson

Ms. Pamela S. Karlan

May 9, 1988

Page 2

CC: Mr. William J. Guste, Jr. (w/encl.)

Mr. M. Truman Woodward, Jr. (w/encl.)

Mr. Blake G. Arata (w/encl.)

Mr. A. R. Christovich (w/encl.)

Mr. Moise W. Dennery (w/encl.)

Mr. Robert G. Pugh (w/encl.)

Mr. Mark Gross (w/encl.)

Mr. Paul D. Kamener (w/encl.)

Mr. Michael H. Rubin (w/encl.)

Mr. John L. Maxey II (w/encl.)

•

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH 'CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V .

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

MOTION FOR AN INJUNCTION PENDING APPEAL OR, IN THE

ALTERNATIVE. FOR ISSUANCE OF THE MANDATE

Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 8(a) and 41(a), appellants ask

that this Court issue an injunction restraining defendants from

conducting any elections to fill positions on the Louisiana

Supreme Court from the First Supreme Court Judicial District

pending the disposition of appellants' challenge to the current

use of a multi-member election district. Appellants have

challenged the present election scheme under both section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, and

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

They seek a preliminary injunction on only their section 2

claim. In the alternative, appellants request that this Court

issue its mandate, despite the pendency of a petition for

rehearing and rehearing en banc. This would permit appellants to

move for a preliminary injunction and summary judgment in the

district court.

The grounds for this motion are set out in the attached

affidavits of Judge Israel M. Augustine, Jr., Judge Revius 0.

Ortique, Jr., Sheriff Paul R. Valteau, Jr., Dr. Richard L.

Engstrom, and Silas Lee, III, and the accompanying memorandum of

law.

Respectfully submitted,

,,1616A LcAA-v

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place

Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

Dated: May 1988

2

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

C. LANI GUINIER

PAMELA S. KARLAN

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

RON WILSON

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Roy Rodney, Jr., hereby certify that on May 1988, I

served copies of the foregoing motion upon the attorneys listed

below via United States mail, first class, postage prepaid:

William J. Guste, Jr., Esq.

Atty. General

La. Dept. of Justice

234 Loyola Ave., Suite 700

New Orleans, LA 70112-2096

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

1100 Whitney Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Blake G. Arata, Esq.

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, LA 70170

A. R. Christovich, Esq.

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Moise W. Dennery, Esq.

21st Floor Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

Robert G. Pugh

330 Marshall Street, Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

Mark Gross, Esq.

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20035

Paul D. Kamener, Esq.

Washington Legal Foundation

1705 N Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

S

Michael H. Rubin, Esq.

Rubin, Curry, Colvin & Joseph

Suite 1400

One American Place

Baton Rouge, LA 70825

John L. Maxey II

P.O. Box 22666

Jackson, MS 39205

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

4

IN-THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V..

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS'

MOTION FOR AN INJUNCTION PENDING APPEAL OR, IN THE

ALTERNATIVE. FOR ISSUANCE OF THE MANDATE

Appellants Ronald Chisom et al., black registered voters in

Orleans Parish, Louisiana, have moved for an injunction pending

appeal restraining defendants (hereafter "the State") from

conducting any elections to fill positions on the Louisiana

Supreme Court from the First Supreme Court Judicial District

until the disposition of appellants' challenge to the current use

of a multi-member election district. Appellants have challenged

the present election scheme under both section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 ("section 2"),

and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

They seek an injunction on only their section 2 claim. In the

alternative, appellants request that this Court issue its

mandate, despite the pendency of a petition for rehearing and

rehearing en banc. This would permit appellants to move for a

preliminary injunction and summary judgment in the district

court.

The Procedural History of this Case

The Louisiana Supreme Court consists of seven judges. Five

of these justices are elected from single-member districts. The

other two are elected from the only multi-member district--the

First Supreme Court District--which contains Orleans, St.

Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson Parishes. Justices serve

ten-year terms. One of the two justiceships allocated to the

First Supreme Court District is scheduled to be filled by

election in the fall of 1988; the other seat is to be filled by

election in the fall of 1990.

On September 19, 1986, two years before the first scheduled

election, appellants filed a complaint, in the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, challenging

the use of an election scheme that submerged Orleans Parish's

predominantly black electorate in a majority-white multi-member

district. They challenged the present system under both the

"results" prong of section 2 and under the intent standard of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

The State moved for, and received, an extension of time

within which to answer the complaint. On March 18, 1987, it

moved to dismiss the complaint pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P.

12(b)(6), on the grounds that section 2 did not apply to the

election of judges.

The district court held oral argument on the State's motion

to dismiss on April 15, 1987. In an opinion and order dated May

2

1, 1987, and subsequently amended on July 10, 1987--after

appellants' brief on the merits had been filed in this Court--the

district court granted the motion, holding that section 2 did not

apply to judicial elections and that plaintiffs had failed to

plead discriminatory intent with sufficient specificity on their

constitutional claims.

On July 9, 1987, when appellants filed their opening brief

on appeal, they had also moved for an expedited hearing in this

Court, due to the pendency of the 1988 elections. That motion

was denied. The State moved for, and received, two extensions of

time within which to file its brief, which was not filed until

September 21, 1987. Subsequently, the State unsuccessfully

sought, after the case was scheduled for oral argument, to

postpone the argument for an additional month.

On December 10, 1988, a panel of this Court--consisting of

Judge Johnson, Judge Higginbotham, and Senior Judge Brown--heard

oral argument. On February 29, 1988, it issued a unanimous

opinion which held both that section 2 applies to judicial

elections and that the complaint adequately pleaded its

constitutional allegations. Chisom V. Edwards, 831 F.2d 1056

(5th Cir. 1988).

The State subsequently moved ex parte for extension of time

within which to file a petition for panel reconsideration and a

suggestion for rehearing en banc. On March 14, 1988, the Clerk's

Office granted that motion to and including April 13, 1988. On

April 13, 1988, the State filed its petition and suggestion.

3

I. Why This Court Should Enjoin the Upcom'eg Elections Now

• As the chronology just laid out shows, appellants sought

relief in the district court long before the scheduled election.

Had the State not sought extensions of time at virtually every

turn, the case might well be over by now, and the issue of

injunctive relief pending appeal might never have arisen.

One of the two seats on Louisiana Supreme Court which is

elected by the voters in the First Supreme Court District is to

be filled by an election now scheduled for October 1, 1988. The

filing dates for candidacy are July 27-29, 1988.

As the affidavits of Judges Augustine and Ortique and of

Sheriff Valteau and Mr. Lee indicate, a candidate considering a

judicial race needs substantial lead time prior to the election

to determine whether he or she can attract the necessary

financial and political support to justify running and then to

obtain that support. As the affidavits and Section II.A.1,

infra, show, no black candidate is likely to run for the seat to

be filled as long as the current district configuration is used.

But even if appellants were to prevail on their claims and a new

district were to be drawn prior to the filing date or election

day, experienced candidates and political observers firmly

believe that the time remaining is too short to permit a black

candidate to mount a serious campaign.

II. This Court Should Grant an Injunction Pending Appeal

4

The test for whether this Court should issue an injunction

focuses on four issues: (1) whether the plaintiff is likely to

prevail on the merits; (2) whether there is a substantial threat

of irreparable injury; (3) whether the threatened injury

outweighs the• threatened harm an injunction might do to the

defendant; and (4) whether granting an injunction will serve the

public interest. Canal Authority v. Callaway, 489 F.2d 567, 572

(5th Cir. 1974). Consideration of each of these issues militates

in favor of granting an injunction.

A. Appellants Are Likely To Succeed on the Merits

In its unanimous opinion holding that section 2 applies to

judicial elections, this Court held that "section 2, by its

express terms, extends to state judicial elections." Chisom v.

Edwards, 839 F.2d at 1060:

Minorities may not be prevented from using section 2 in

their efforts to combat racial discrimination in the

election of state judges; a contrary result would

prohibit minorities from achieving an effective voice

in choosing those individuals society elects to

administer and interpret the laws. The right to vote,

the right to an effective voice in our society cannot

be impaired on the basis of race in any instance

wherein the will of the majority is expressed by

popular vote.

Id. at 1065.

One of the primary sources on which this Court relied in

reaching its conclusion that section 2 covers judicial elections

was the legislative history of the 1982 amendments to section 2.

See 839 F.2d at 1061-63.

The purpose of those 1982 amendments was to eliminate the

5

requirement that plaintiffs show that challenged voting practices

are the product of purposeful discrimination. Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.S. , 92 L.Ed.2d 25, 37, 42 (1986). The Senate

Report accompanying the 1982 amendments, which Gingles

characterized as an "authoritative source" for interpreting

section 2, Thornburg V. Gingles, 92 L.Ed.2d at 42 n. 7, lists

nine "[t]ypical factors" that can serve to show a violation of

section 2's "results test." S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 28 (1982)

("Senate Report") 1

1 These factors are:

"1. the extent of any history of official

discrimination in the state or political subdivision

that touched the right of the members of the minority

group to register, to vote, or otherwise to participate

in the democratic process;

2. the extent to which voting in the elections of

the state or political subdivision is racially

polarized;

3. the extent to which the state or political

subdivision has used unusually large election

districts, majority vote requirements, anti-single shot

provisions, or other voting practices or procedures

that may enhance the opportunity for discrimination

against the minority;

4. if there is a candidate slating process,

whether the members of the minority group have been

denied access to that process;

5. the extent to which members of the minority

group in the state or political subdivision bear the

effects of discrimination in such areas as education,

employment and health, which hinder their ability to

participate effectively in the political process;

6. whether political campaigns have been

characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the minority

group have been elected to public office in the

jurisdiction.

[8.] whether there is a significant lack of

responsiveness on the part of elected officials to the

particularized needs of the members of the minority

group.

6

Gingles represents the Supreme Court's "gloss" on these

Senate factors. Carrollton Branch of NAACP V. Stallings, 829

F.2d 1547, 1555 (11th Cir. 1987). In the context of at-large

elections, "the most important Senate Report factors . . . are

the 'extent to which members of the minority group have been

elected to public office in the jurisdiction' and the 'extent to

which voting in the elections of the state or political

subdivision is racially polarized.'" Thornburg v. Gingles, 92

L.Ed.2d at 45, n. 15. 2 The other factors are "supportive of, but

not essential to, a minority voter's claim." Id,

Because this case was before this Court on appeal from an

order of dismissal under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6), defendants

have not yet answered the allegations of plaintiffs' complaint,

which this Court held to have stated a cause of action under both

section 2 and the Constitution. Nor, of course, have any

[9.] whether the policy underlying the state or

political subdivision's use of such voting

qualification, prerequisite to voting, or standard,

practice or procedure is tenuous."

S. Rep. No. 97-417, pp. 28-29 (1982). "[T]here is no requirement

that any particular number of factors be proved, or that a

majority of them point one way or the other." Id. at 29.

2 This assessment led the Court to distill from the

Senate factors a three-part test for challenges to at-large

elections that seek a single-member district remedy: first, the

minority group must show that it is sufficiently large and

geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-

member district; second, it must show that it is politically

cohesive, that is, that its members tend to support the same

candidates; third, it must show that the white majority usually

votes sufficiently as a bloc to result in the defeat of the

minority group's preferred candidates. Thornburg V. Gingles, 92

L.Ed.2d at 46.

7

discovery or pretrial proceedings taken place. Nonetheless,

sufficient undisputed evidence already exists, much of which is

subject to judicial notice under Fed. R. Evid. 201, to show that

plaintiffs are likely to prevail on the merits of their section 2

claim.

1. The Essential Gingles Factors

With regard to the first of these factors, the evidence is

undisputed and, as this Court has already noted, "particularly

significant," Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d at 1058: "[N]o black

person has ever been elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court,

either from the First Supreme Court District or from any one of

the other five judicial districts." Id.

Indeed, no black candidate has run. The affidavits of Judge

Revius 0. Ortique, Jr., Judge Israel M. Augustine, Jr., Sheriff

Paul R. Valteau, Jr., and Silas Lee explain why: the current

configuration of the First Supreme Court District makes it

impossible for a black candidate to win, and thus deters black

candidates from running. In cases such as this one, "the lack of

black candidates is a likely result of a racially discriminatory

system." McMillan V. Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037, 1045 (11th

Cir. 1984). See. e.g., Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of

Gretna, 636 F. Supp. 1113 1119 (E.D. La. 1986) ("axiomatic" that

when minorities are face with dilutive electoral structures

"candidacy rates tend to drop'") (quoting Minority Vote Dilution

15 (C. Davidson ed. 1984)), aff'd, 834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987);

8

Hendrix V. McKinney, 460 F. Supp. 626, 631-32 (M.D. Ala. 1978),

(fact of racial bloc voting, when combined with at-large

elections for county commission "undoubtedly discourages black

candidates because they face the certain prospect of defeat").

With regard to the second factor--the presence of racially

polarized voting--the evidence is also clear. Maior V. Treen,

574 F. Supp. 325 (E. D. La. 1983) (three-judge court), struck down

a congressional districting scheme which diluted the strength of

Orleans Parish's predominantly black electorate by splitting that

electorate in half and submerging the two parts in majority-

white suburban congressional districts. The combined area of the

two districts constituted essentially the First Supreme Court

District being challenged in this case. See 574 F. Supp. at 328.

The Major Court found "a substantial degree of racial

polarization exhibited in the voting patterns of Orleans Parish."

Id. at 337. It also held that voting preferences in the

"adjacent suburban parishes, whose recently enhanced populations

can be partially ascribed to the exodus from New Orleans of white

families seeking to avoid court-ordered desegregation of the

city's public schools" made those parishes even less receptive to

black candidates. Id. at 339.

Major's finding of legally significant racial polarization

rested in significant part on the existence of racial bloc voting

in local judicial elections. The court expressly relied on a

regression analysis performed by plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Gordon

Henderson, which studied the results of thirty-nine elections in

9

Orleans Parish during the period 1976 to 1982 in which black

candidates ran. _age 574 F. Supp. at 337-38. Thirteen, or one-

third, of these elections involved judicial positions.

Racial bloc voting in judicial elections for positions on

lower courts within the First Supreme Court District continues to

this day. Dr. Richard L. Engstrom, a nationally recognized

expert in the quantitative analysis of racial voting patterns,

see Gingles, 92 L.Ed.2d at 48 n. 20, 50 & 60 (citing Dr.

Engstrom's scholarly writings with approval), was asked by the

plaintiffs in Clark V. Edwards, No. 86-435-A (M.D. La.), a case

challenging the method of electing Louisiana district court

judges, to analyze judicial election contests involving black and

white candidates during the period 1978 to 1987. Dr. Engstrom

used the analytic techniques--bivariate ecological regression and

extreme case analysis--approved by the Supreme Court in Gingles,

92 L.Ed.2d at 48. As part of his analysis, Dr. Engstrom analyzed

election returns from the geographic area relevant to this case

involving sixteen black candidates in fourteen separate contests.

In thirteen of fourteen races, a black candidate was the

preferred choice of black voters. In no election was a black

candidate the choice of white voters. In the thirteen contests

in which the black community supported a black candidate, an

average of 78.25 percent of the black electorate voted for the

preferred black candidate, 3 while only 14.26 percent of white

3 Two of these races involved more than one black

candidate. In one (the Feb. 2, 1982 election for Orleans-

Criminal I), Julien was the plurality victor among black voters,

10

voters voted for the preferred black candidate.

Finally, the Supreme Court has noted that plaintiffs in

cases challenging multi-member districts and seeking single-

member districts as a remedy must show that the minority group of

which they are members "is sufficiently large and geographically

compact . . . [that it could] constitute a majority in a single-

member district." Gingles, 92 L.Ed.2d at 46. Clearly, the black

population of Orleans Parish satisfies this requirement. Over

half the First Supreme Court District's population lives in

Orleans Parish, and, as of March 31, 1988, slightly over 52

percent of the registered voters in Orleans Parish are black.

See Affidavit of Silas Lee, III. Judicial districts are not

required to comply with the requirement of one-person, one-vote.

See Chisom, 839 F.2d at 1060. Thus, there is no need--

particularly in assessing appellants' likelihood of success on

the merits, as opposed to actually imposing a remedial plan--for

this Court to address the precise contours of a proper division

of the present First Supreme Court District.

2. The Supportive Senate Factors

This Court may take judicial notice of findings by other

courts with regard to several of the other, historical factors

and 72.3 percent of black voters preferred one of the black

candidates. Julien subsequently received over 88 percent of the

black vote in the runoff. In the other (the Feb. 1, 1986

election for Orleans-Civil F), Magee was the choice of 75.3

percent of black voters, and 97.1 percent of black voters

preferred one of the black candidates.

11

mentioned in the Senate Report. Fed. R. Evid. 201; Age United

Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 198 n. 1 (1979) (findings of

discrimination in craft unions were so numerous as to be a proper

subject for judicial notice).

With regard to the first of the Senate factors--a history of

official discrimination touching upon the right to vote--

Louisiana's actions cannot seriously be disputed. As Judge

Politz, writing for the three-judge court in Major v. Treen

noted, from 1898 to 1965, the State used a variety of stratagems,

including educational and property requirements for voting, a

"grandfather" clause, an "understanding" clause, poll taxes,

discriminatory purging procedures, an all-white primary, a ban on

single-shot voting, and a majority-vote requirement to

"suppres(s) black political involvement . . . ." 574 F. Supp. at

340; see also. e.g., Citizens for a Better Gretna, 636 F. Supp.

at 1116-17. These two district courts also discussed the effect

of the fifth Senate factor: discrimination in education,

employment and health that has hindered blacks political

participation. See id. at 1117; Major V. Treen, 574 F. Supp. at

341.

Finally, with regard to the third Senate factor--the use of

voting practices or procedures that may enhance discrimination

against black voters--we note that all three practices expressly

identified by the Senate Report are present in this case. First,

the First Supreme Court District is an "unusually large election

distric(t)," Senate Report at 29. It is far larger in population

12

than any other Supreme Court District. Moreover, it is the only

multi-member district, and thus departs from the standard Supreme

Court District, which elects a single justice. Second, Louisiana

has a majority-vote requirement for judicial elections. See

Senate Report at 29. This means that even if the majority white

electorate were to split its votes among several candidates, a

black candidate would not have the opportunity to win by a

plurality. According to Major, this requirement "inhibits

political participation by black candidates and voters and

"substantially diminishes the opportunity for black voters to

elect the candidate of their choice. 574 F. Supp. at 339.

Third, elections from the First Supreme Court District are

subject to the functional equivalent of an "anti-single shot"

provision, Senate Report at 29. Single-shot voting requires

multi-position races. See City of Rome v. United States, 446

U.S. 156, 184 (1980). But because the terms of the two justices

from the First Supreme Court District are staggered, only one

seat is filled at any election. Thus "the opportunity for

single-shot voting will never arise." ;d. at 185 n. 21 (internal

quotation marks omitted; quoting U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, The

Voting Rights Act: Ten Years After 208 (1975)); see also. e.g.,

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, p. 18 (1982) (condemning staggered terms).

Thus, appellants have demonstrated that it is likely that,

on remand, they will prevail, at a minimum, on their section 2

results claim. Indeed, that claim is appropriate for summary

13

judgment.

B. There Is a Substantial Threat of Irreparable Injury to

Appellants If The Upcoming Election Is Not Enjoined

This Court has held that an injury is irreparable "if it

cannot be undone through monetary remedies." Deerfield Medical

Center v. City of Deerfield Beach, 661 F.2d 328, 338 (5th Cir.

1981). The right at issue in this case is entirely nonpecuniary,

and no amount of financial compensation can redress its

deprivation.

The right to vote is the "fundamental political right,

because preservative of all rights." Yick Wo. V. Hopkins, 118

U.S. 356, 370 (1886). That right "can be denied by a debasement

or dilution of the weight of a citizen's vote just as effectively

as by wholly prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise."

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 555 (1964). As this Court has

already held in this case, "[t]he right to vote, the right to an

effective voice in our society cannot be impaired on the basis of

race in any instance wherein the will of the majority is

expressed by popular vote." 839 F.2d at 1065 (emphasis added).

The courts have long recognized that conducting elections

under systems that impermissibly dilute the voting strength of an

identifiable group works an irreparable injury on both that group

and the entire fabric of representative government. In Reynolds

v. Sims, the Supreme Court noted that "it would be the unusual

case in which a court would be justified in not taking

appropriate action to insure that no further elections are

14

conducted under the invalid Plan. 377 U.S. at 585 (emphasis

added). See, e.g., Watson v. Commissioners Court of Harrison

County, 616 F.2d 105, 107 (5th Cir. 1980) (per curiam) (ordering

district court to enjoin elections because failure to do so would

subject county residents to four more years of government by an

improperly elected body); Harris v. Graddick, 593 F. Supp. 128

(M.D. Ala. 1984) (impediment to right to vote "would by its

nature be an irreparable injury"); Cook v. Luckett, 575 F. Supp.

479, 484 (S.D. Miss. 1983) (noting the "irreparable injury

inherent in perpetuating voter dilution"); cf. Elrod v. Burns,

427 U.S. 347, 373 (1976) (denial of rights under the First

Amendment "unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury");

Middleton-Keirn V. Stone, 655 F.2d 609, 611 (5th Cir. 1981)

(irreparable injury to both black workers and Nation's labor

force as a whole is presumed in Title VII cases).

There is a substantial threat in this case of such a

dilution of black voting strength in the October 1, 1988,

election. First, the voting strength of Orleans Parish's

predominantly black electorate will be subsumed within the

larger, majority-white suburban electorate. See supra Section

II.A.1.

Second, as the affidavits of Judges Augustine and Ortique

show, the present election scheme will deter candidates who rely

primarily on the support of black voters from running. And those

candidates will be unable to obtain the financial backing

necessary for a credible candidacy as long as the present

15

district configuration continues. Thus, black voters will not

even have an equal opportunity to vote for candidates of their

choice, let alone the equal opportunity to elect such candidates

promised by section 2.

C. The State Will Suffer No Injury If the Upcoming

Election Is Postponed

The State will not be adversely affected in any way if the

1988 election is postponed until the merits of appellants' claims

are determined. Such a postponement would continue the terms of

the two sitting justices from the First Supreme Court District.

Cf. Kirksey V. Allain, Civ. Act. No. J-85-960(B) (S.D. Miss. May

28, 1986) (enjoining elections of state court judges pending

outcome of section 2 suit); 4 Kirksey V. Allain, 635 F. Supp. 347

(S.D. Miss. 1986) (three-judge court) (enjoining judicial

elections for unprecleared jurisdictions). Thus, the Louisiana

Supreme Court will be able to continue its work unaffected.

The only potential injury defendants might suffer is the

expense of conducting a special election, should the district

court ultimately conclude that such an election is required. See

Cook v. Luckett, 575 F. •Supp. 479, 485 (S.D. Miss. 1983). It is

entirely possible, however, that any future election to fill

seats on the Supreme Court can be coordinated with regularly

4 Subsequently, in Kartin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183

(S.D. Miss. 1987), the district court found that Mississippi's

use of multi-member, numbered post judicial districts in certain

parts of the state violated section 2. At the present time,

remedy proceedings are underway, and judicial elections in the

affected districts have been postponed for the past two years.

16

scheduled elections, and such expense avoided entirely. See.

e.g., Smith V. Paris, 386 F.2d 979 (5th Cir. 1967) (per curiam)

(shortening terms of officials elected under discriminatory at-

large scheme so that new elections would coincide with next

regularly scheduled elections).

D. The Public Interest Would Best Be Served By Enjoining

the Upcoming Election

Because appellants sought relief over two years before the

scheduled election, if this Court denies an injunction pending

appeal and appellants ultimately prevail on the merits, the

results of the upcoming election will have to be set aside. See,

s.„2„.., Hamer v. Campbell, supra. A justice elected in 1988

pursuant to an election system that dilute black political power

cannot be permitted to serve for 10 years, until 1998 when the

term would normally expire. See, e.g., Watson v. Commissioners

Court, 616 F.2d at 107 (service for another four years too long);

Smith v. Paris, 386 F.2d at 980 (ordering special election at

next regularly scheduled election, in two years); Hamer v.

Campbell, 358 F.2d at 222 (service for another four years too

long). And the public interest in having a judiciary free from

racial discrimination in its selection is obviously of the

highest importance, as this Court's decision in Chisom

recognized.

In light of appellants' likely success on the merits, the

public interest would best be served in not conducting an

election in 1988. First, such an election would likely have to

17

be repeated in two years. This possibility might dampen interest

both in seeking office and in voting and might decrease financial

support for candidates. Second, given the probable illegitimacy

of the present system, it would be unfair for a candidate to run

under the present scheme and thereby have an unfair advantage as

an incumbent only two years later. gg,_ Major v. Treen, 574 F.

Supp. at 355. Third, the qualities of deliberation and non-

politicization that the decade-long term of office now serves

might be undermined by creating, in essence, a two-year term.

No public interest could be more important than the

eradication of racial discrimination that impairs the right to

vote. Thus, appellants have satisfied all four prongs of this

Court's test for a preliminary injunction and this Court should

therefore order the postponement of the upcoming elections.

III. In the Alternative, This Court Should Issue Its Mandate

If this Court is not inclined to grant an injunction pending

appeal itself, it should issue the mandate, currently stayed by

•the State's petitions for rehearing and rehearing en banc. The

issuance of the mandate would return the case to the district

court, where appellants could renew their motion for a

preliminary injunction, seek expedited discovery, and soon move

for summary judgment.

Otherwise, it is abundantly clear that the merits of this

case will not be determined in time for the October 1, 1988,

election, let alone far enough before the election for potential

18

candidates who enjoy the support of the black community to meet

filing requirements, raise sufficient funds, and run serious

campaigns. Even if this Court were to rule immediately on the

State's pending petitions, the State might still petition for

certiorari. The mandate will automatically be stayed for an

additional 30 days to give the State an opportunity to prepare

its petition, see Fed. R. App. P. 41, and, even if the State

decides it needs more time to prepare its petition, it will be

able, by ex parte motion, to seek further stays under this

Court's Rule 10.

In any event, if the State petitions for certiorari, the,

petition is unlikely to be filed before the beginning of June.

That filing will, of course, further stay issuance of the

mandate. Given the manner in which the Supreme Court schedules

petitions for consideration at Conference, it is unlikely, even

if appellants were to waive their right to respond or to file an

opposition long before their 30 days to reply had run, that the

case could be considered before the Supreme Court recesses for

the summer. Thus, the petition for certiorari is unlikely to be

disposed of before the first Monday in October, after the

scheduled election.

Conclusion

Two years ago, appellants filed a lawsuit challenging the

method of electing justices from the First Supreme Court District

in the hope that by 1988 a fair election system would be in

19

place. Despite their diligent efforts to prosecute their suit,

they now face the threat that once again their voices will not be

heard equally in the election process. Accordingly, they ask

this Court either to enjoin the present, illegitimate system or

to provide them with an opportunity to seek that relief from the

district court.

Respectfully submitted,

17awsigS165)6&

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place

Suite 901

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

20

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

C. LANI GUINIER

PAMELA S. KARLAN

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

ROY RODNEY, JR.

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

Dated: May J, 1988

RON WILSON

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF sERvIcg

I, Roy Rodney, Jr., hereby certify that on May 1988, I

served copies of the foregoing memorandum upon the attorneys

listed below via United States mail, first class, postage

prepaid:

William J. Guste, Jr., Esq.

Atty. General

'La. Dept. of Justice

234 Loyola Ave., Suite 700

New Orleans, LA 70112-2096

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

1100 Whitney Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Blake G. Arata, Esq.

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, LA 70170

A. R. Christovich, Esq.

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Moise W. Dennery, Esq.

21st Floor Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

Robert G. Pugh

330 Marshall Street, Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

Mark Gross, Esq.

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20035

Paul D. Kamener, Esq.

Washington Legal Foundation

1705 N Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

22

• •

Michael H. Rubin, Esq.

Rubin, Curry, Colvin & Joseph

Suite 1400

One American Place

Baton Rouge, LA 70825

John L. Maxey II

P.O. Box 22666

Jackson, MS 39205

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Appellants