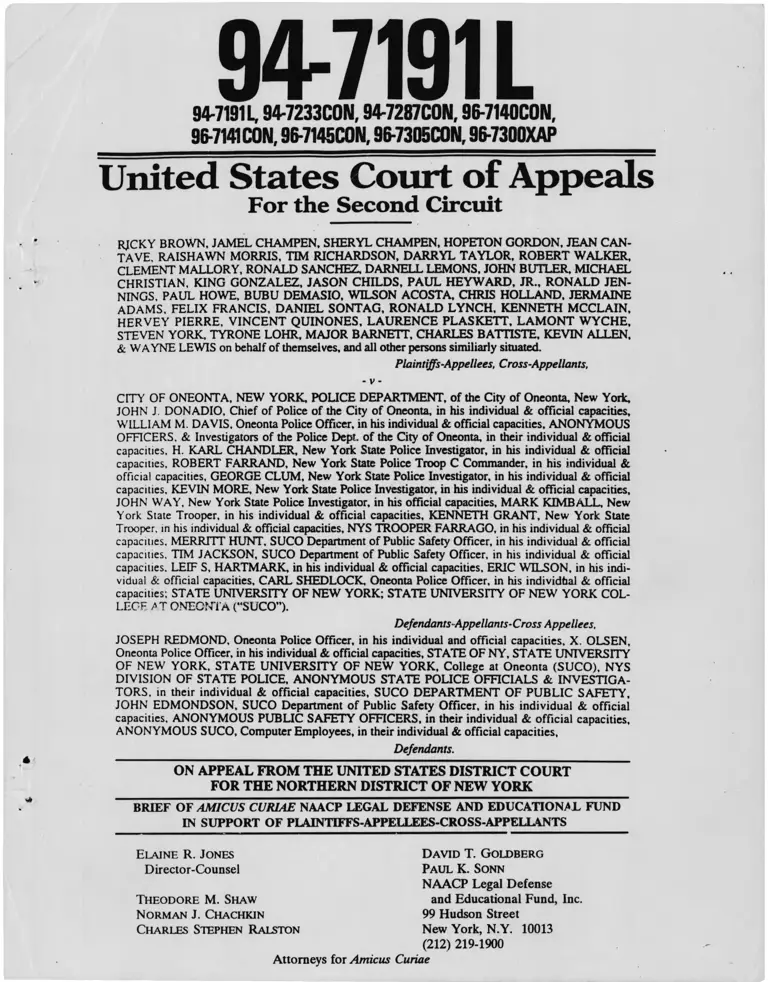

Brown v. City of Oneonta, New York, Police Department Brief of Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees-Cross-Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 29, 1996

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. City of Oneonta, New York, Police Department Brief of Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees-Cross-Appellants, 1996. 5b72ede1-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2ae63bf2-a86f-479e-bd5c-406db2e2597f/brown-v-city-of-oneonta-new-york-police-department-brief-of-amicus-curiae-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-in-support-of-plaintiffs-appellees-cross-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

947191L

94-7191L, 94-7233C0N, 94-7287C0N, 96-7140CON,

________ 96-7141 CON, 96-7145CON, 96-7305CQN, 96-7300XAP________

United States Court of Appeals

F o r th e S econd C ircu it

RJCKY BROWN, JAMEL CHAMPEN, SHERYL CHAMPEN, HOPETON GORDON. JEAN CAN-

TAVE. RAISHAWN MORRIS, TIM RICHARDSON, DARRYL TAYLOR, ROBERT WALKER,

CLEMENT MALLORY, RONALD SANCHEZ, DARNELL LEMONS, JOHN BUTLER, MICHAEL

CHRISTIAN. KING GONZALEZ, JASON CHILDS, PAUL HEYWARD, JR., RONALD JEN

NINGS, PAUL HOWE, BUBU DEMASIO, WILSON ACOSTA, CHRIS HOLLAND, JERMAINE

ADAMS. FELIX FRANCIS, DANIEL SONTAG, RONALD LYNCH, KENNETH MCCLAIN,

HERVEY PIERRE, VINCENT QUINONES, LAURENCE PLASKETT, LAMONT WYCHE,

STEVEN YORK, TYRONE LOHR, MAJOR BARNETT, CHARLES BATTISTE, KEVIN ALLEN.

& WAYNE LEWIS on behalf of themselves, and all other persons similiarly situated.

Plaintiffs-Appellees, Cross-Appellants,

- v -

CITY OF ONEONTA, NEW YORK, POLICE DEPARTMENT, of the City of Oneonta, New York,

JOHN J. DONADIO, Chief of Police of the City o f Oneonta, in his individual & official capacities,

WILLIAM M. DAVIS, Oneonta Police Officer, in his individual & official capacities, ANONYMOUS

OFFICERS, & Investigators of the Police Dept, of the City o f Oneonta, in their individual & official

capacities. H. KARL CHANDLER, New York State Police Investigator, in his individual & official

capacities, ROBERT FARRAND, New York State Police Troop C Commander, in his individual &

official capacities, GEORGE CLUM, New York State Police Investigator, in his individual & official

capacities, KEVIN MORE, New York State Police Investigator, in his individual & official capacities,

JOHN WAY, New York State Police Investigator, in his official capacities, MARK KIMBAI.L, New

York State Trooper, in his individual & official capacities, KENNETH GRANT, New York State

Trooper, in his individual & official capacities, NYS TROOPER FARRAGO, in his individual & official

capacities, MERRITT HUNT, SUCO Department o f Public Safety Officer, in his individual & official

capacities, TIM JACKSON, SUCO Department of Public Safety Officer, in his individual & official

capacities, LEEF S, HARTMARK, in his individual & official capacities, ERIC WILSON, in his indi

vidual & official capacities, CARL SHEDLOCK, Oneonta Police Officer, in his individtial & official

capacities; STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK; STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK COL

LEGE AT ONEONTA (“SUCO”).

Defendants-Appellants-Cross Appellees,

JOSEPH REDMOND, Oneonta Police Officer, in his individual and official capacities, X. OLSEN,

Oneonta Police Officer, in his individual & official capacities, STATE OF NY, STATE UNIVERSITY

OF NEW YORK, STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK. College at Oneonta (SUCO). NYS

DIVISION OF STATE POLICE, ANONYMOUS STATE POLICE OFFICIALS & INVESTIGA

TORS, in their individual & official capacities, SUCO DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY,

JOHN EDMONDSON, SUCO Department o f Public Safety Officer, in his individual & official

capacities, ANONYMOUS PUBLIC SAFETY OFFICERS, in their individual & official capacities,

ANONYMOUS SUCO, Computer Employees, in their individual & official capacities,

Defendants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES-CROSS-APPEULANTS

Elaine R. Jones David T. Goldberg

Director-Counsel PAUL K. SONN

NAACP Legal D efense

Theodore M. Shaw and Educational Fund, Inc.

Norman J. Chachkin 99 Hudson Street

Charles Stephen Ralston New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.........................................ii

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS C U R I A E .................... 1

FACTS AND PROCEEDINGS BELOW ................................ 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................ 8

ARGUMENT . . . -............................................... 12

I. The Decision Below Rests on a Basic Misapprehension

of Equal Protection Law: Express Racial

Classifications Always Require Close Judicial

Scrutiny...........................................12

II. Identification of a Similarly Situated, But

Differently Treated, Nonminority Class Is Merely

One Way Among Many of Proving Racial

Discrimination, in Violation of the Equal

Protection Clause ................................ 17

III. Requiring Identification of a "Similarly Situated"

Class Is Plainly Inappropriate in Cases Involving

Racial Discrimination ............................ 25

IV. The Complaint Alleges Governmental Conduct

Violative of Rights Clearly Established Under the

Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments................ 2 9

CONCLUSION................................................ ...

4

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

C A SE S

Adarand v. Pena,

132 L. Ed. 2d 158 (1995) ...............

Albert v. Carovano,

851 F .2d 561 (2d Cir. 1988) ...........

Anderson v. Martin,

375 U.S. 399 (1964) ....................

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev.

429 U.S. 252 (1977) ....................

Batson v. Kentucky,

476 U.S. 79 (1986) . ....................

......... passim

..............20

. . 9, 15, 25, 34

Corp.,

......... passim

............. 1

Blue v. Koren,

72 F . 3d 1075 (2d Cir. 1995) ............................ 12

Bray v. Alexandria Women's Health Clinic,

122 L. Ed. 2d 34 (1993) ................................. 18

Brown v. Board of Educ.,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) 1

Brown v. City of Oneonta (Brown II),

858 F. Supp. 340 (N.D.N.Y. 1 9 9 4 ) ......................... 5

Brown v. City of Oneonta (Brown III),

911 F. Supp. 580 (N.D.N.Y 1996) passim

Brown v. City of Oneonta (Brown IV),

916 F. Supp. 176 (N.D.N.Y. 1 9 9 6 ) ......................... 5

Brown v. Texas,

443 U.S. 47 (1979)....................................... 31

ii

Buffkins v. City of Omaha,

922 F . 2d 465 (8th Cir. 1 9 9 2 ) ........................ 32, 37

City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr., Inc.,

473 U.S. 432 (1985) ................................. 6, 13

City of Los Angeles v. Garza,

918 F . 2d 763 (9th Cir. 1 9 9 0 ) ............................ 17

City of Richmond v. J. A. Croson Co.,

488 U.S. 469 (1989) .................................passim

City of Richmond v. United States,

422 U.S. 358 (1975) 10, 21

Davis v. Mississippi,

394 U.S. 721 (1969) ..................................... 1

Delaware v. Prouse,

440 U.S. 648 (1979) ..................................... 38

Department of Agriculture v. Moreno,

413 U.S. 528 (1973) ..................................... 28

Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co.,

500 U.S. 614 (1991) 35

Esmail v. Macrane,

53 F . 3d 176 (7th Cir. 1995) ............................ 28

FCC v. Beach Communications, Inc.,

124 L. Ed. 2d 211 (1993)................................. 27

Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972) 1

Gehl Corp. v. Koby,

63 F.3d 1528 (10th Cir. 1995) .......................... 25

Guinn v. United States,

238 U.S. 347 (1915) 13

iii

Hall v. Pennsylvania State Police,

570 F .2d 86 (3d Cir. 1978) . 16, 31, 35

Hishon v. King & Spalding,

467 U.S. 69 (1984)....................................... 24

INS v. Delgado,

466 U.S. 210 (1984)....................................... 38

Imbler v. Pachtman,

424 U.S. 409 (1976) ..................................... 25

Johnson v. Transportation Agency,

480 U.S. 616 (1987) ..................................... 32

Kaluczky v. City of White Plains,

57 F . 3d 202 (2d Cir. 1995) ............................ 12

Kolender v. Lawson,

,461 U.S. 352 (1983) ..................................... 34

Korematsu v. United States,

323 U.S. 214 (1944) ................................. 20, 31

Lankford v. Gelston,

364 F . 2d 197 (4th Cir. 1 9 6 6 ) ............................ 32

Leatherman v. Tarrant County,

122 L. Ed. 2d 517 (1993)................................. 22

Lehnhausen v. Lake Shore Auto Parts Co.,

410 U.S. 356 (1973)....................................... 27

Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 (1967) ............................ 1, 9, 15, 29

Malley v. Briggs,

475 U.S. 335 (1986) ..................................... 25

McFarland v. Smith,

611 F.2d 414 (2d Cir. 1979) ............... 29, 30, 31, 34

IV

Miller v. Johnson,

132 L. Ed. 2d 762 (1995)............................ passim

Mitchell v. Baldridge,

759 F . 2d 80 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 8 5 ) ............................ 20

Mitchell v. Forsyth,

472 U.S. 511 (1985) ..................................... 7

Moran v. Burbine,

475 U.S. 412 (1986) ..................................... 31

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button,

371 U.S. 415 (1963) ..................................... 1

Orange Lake Associates Inc. v. Kirkpatrick,

21 F . 3d 1214 (2nd Cir. 1 9 9 4 ) ........... 9, 13, 18, 26, 28

Palmore v. Sidoti,

466 U.S. 429 (1984) ..................................... 31

People v. Bower,

24 Cal.3d 638, 597 P.2d 115 (1979) .................... 16

People v. Hollman,

79 N . Y . 2d 181, 581 N.Y.S.2d 619 (1992)................. 23

Personnel Adm'r of Massachusetts v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256 (1979) ................................. 9, 13

Plyler v. Doe,

457 U.S. 202 (1982) ..................................... 27

Powers v. Ohio,

499 U.S. 400 (1991) .................................passim

Regents of University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978) ........................ 11, 14, 30, 39

Reid v. Georgia,

448 U.S. 438 (1980) ..................................... 33

v

28

26

26

sim

14

22

35

9

20

1

20

20

38

38

Romer v . Evans,

No. 94-1039, 1996 U.S. LEXIS 3245 (May 20,

Sector Enters., Inc. v. Dipalermo,

779 F. Supp. 236 (N.D.N.Y. 1991) . . . . .

Samaad v. City of Dallas,

940 F .2d 925 (5th Cir. 1991) . . .........

Shaw v. Reno,

125 L. Ed. 2d 511 (1993) .................

Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1 (1948) ........................

Siegert v. Gilley,

500 U.S. 226 (1991) ......................

Smith v. Goguen,

.415 U.S. 566 (1974) ......................

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ........................

Talley v. Bravo Pitino Restaurant, Ltd.,

61 F .3d 1241 (6th Cir. 1995) .............

Terry v. Ohio,

392 U.S. 1 (1968) ........................

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Thurston,

469 U.S. Ill (1985) ......................

U.S. Postal Service Bd. v. Aikens,

460 U.S. 711 (1983) ......................

United States v. Harvey,

16 F .3d 109 (6th Cir. 1994) .............

United States ex rel. Haynes v. McKendrick,

481 F .2d 152 (2nd Cir. 1973) ...........

1996)

34,

vi

25, 31

United States v. Armstrong,

No. 95-157, 64 U.S.L.W. 4305 (May 13, 1996)

United States v. Bautista,

684 F . 2d 1286 (9th Cir. 1982) ...................... 30, 32

United States v. Beck,

602 F . 2d 726 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 9 ) ............................ 30

United States v. Brignoni-Ponce,

422 U.S. 873 (1975) ........................ 10, 29, 30, 32

United States v. Ceballos,

684 F . 2d 177 (2d Cir. 1981) ........................ 11, 32

United States v. Hooper,

955 F . 2d 484 (2d Cir. 1991) ............................ 38

United States v. Laymon,

730 F. Supp. 332 (D. Colo. 1 9 9 0 ) .................... 16, 31

United States v. Lopez-Martinez,

25 F . 3d 1481 (10th Cir. 1 9 9 4 ) ...................... 30, 34

United States v. Manuel,

992 F.2d 272 (10th Cir. 1993) ............. 8, 30, 31, 37

United States v. Martinez-Fuerte,

428 U.S. 543 (1976) ..................................... 32

United States v. Nicholas,

448 F . 2d 622 (8th Cir. 1 9 7 1 ) ............................ 31

United States v. Paradise,

480 U.S. 149 (1987) ..................................... 32

United States v. Patrick,

899 F . 2d 169 (2d Cir. 1990) ............................ 34

United States v. Prandy-Binett,

995 F . 2d 1069 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 9 3 ) .......................... 31

vii

United States v. Rias,

524 F . 2d 118 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 5 ) ............................ 32

United States v. Taylor,

956 F . 2d 572 (6th Cir. 1 9 9 2 ) ............................ 37

United States v. Thomas,

787 F. Supp. 665 (E.D. Tex. 1992) ...................... 37

United States v. Travis,

62 F . 3d 170 (6th Cir. 1995) ............... 11, 16, 30, 31

United States v. Williams,

714 F . 2d 777 (8th Cir. 1 9 8 3 ) ............................. 30

Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229 (1976) ................................. 17, 18

Washington v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1,

458 U.S. 457 (1982) ................................. 9, 17

Williams v. Alioto,

549 F . 2d 136 (9th Cir. 1 9 7 5 ) .........'.................. 32

Williamson v. Lee Optical,

348 U.S. 483 (1955) 26

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Educ.,

476 U.S. 267 (1986) 32

Yale Auto Parts v. Johnson,

758 F . 2d 54 (2d Cir. 1 9 8 5 ) ............................... 26

Yusef v. Vassar College,

35 F.3d 709 (2d Cir. 1994) 19

ST A T U T E S AND RULES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b) (6) ................................. passim

Fed. R. Civ. P. 2 3 ............................................ 4

viii

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b) 4

20 U.S.C. § 1 2 3 2 g ............................................. 2

28 U.S.C. 1 2 9 1 ................................................ 7

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 ........................................... passim

MISCELLANEOUS

Note, Developments in the Law -- Race and the

Criminal Process, 101 Harv. L. Rev. 1472

(1988)................................................ 34, 36

Sheri Lynn Johnson, Race & The Decision to Detain a

Suspect, 93 Yale L.J. 214 (1983)........................ 33

U.S. Sentencing Comm'n, Annual Report (1995) ............... 6

IX

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) was

incorporated in 1939 under the laws of New York State, for the

purpose, inter alia, of rendering legal aid free of charge to

indigent "Negroes suffering injustices by reason of race or color."

Its first Director-Counsel was Thurgood Marshall.

LDF has appeared as counsel of record or amicus curiae in

numerous cases before the Supreme Court, and before this and other

federal Courts of Appeals, involving the proper scope of

constitutional and statutory civil rights guarantees. See, e.g.,

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954); Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 (1967) ; see also N .A .A.C .P . v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422

(1963) (describing Legal Defense Fund as a "'firm' . . . which has

a corporate reputation for expertness in presenting and arguing the

difficult questions of law that frequently arise in civil rights

litigation").

As part of its mission of eradicating racial injustice from

all aspects of American life, the Legal Defense Fund has long had

a special concern for the influence of race in the administration

of criminal justice. Accordingly, LDF has played an active role in

cases seeking to ensure fair treatment in law enforcement, e.g.,

Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968); Davis v. Mississippi, 394 U.S.

721 (1969), and in all phases of the criminal justice process,

e.g., Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986); Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972).

FACTS AND PROCEEDINGS BELOW

This is an appeal from two district court orders in a civil

rights action arising from the conduct of various governmental

officials, as well as the City of Oneonta, New York, the State

University College at Oneonta ("SUCO"), and the State University

system. The relevant facts of the .case are, for the most part,

undisputed.1

In the early morning of September 4, 1992, police received a

report of an attempted burglary and assault committed a few hours

earlier at a private residence just outside Oneonta, New York. The

complaining witness, a 77-year-old woman who was an overnight guest

in the home, reported having been assaulted at knife-point in a

darkened room. She alleged that her assailant was a young black

man who, she said, had sustained a cut on his hand or arm in the

course of committing the offense.

The police reacted in sweeping fashion. The day the crime was

reported, officers appeared at the local campus of the State

University, urging university officials to generate and turn over

to them a list of every African-American male enrolled at the

institution. Notwithstanding a statutory obligation to maintain

the privacy of students' personal records, see 20 U.S.C. § I232g,2

university officials satisfied the police request, compiling a list

with the names and addresses of 78 black male SUCO students.

JGiven the present posture of the case, of course, this Court

must assume that the allegations of plaintiffs Brown, et al., are

true .

2The Federal Educational Records Privacy Act or "FERPA."

2

A concerted effort to interrogate and physically examine (for

scars) every black male student ensued. Various students were

accosted at their homes and dormitory rooms, while others were

stopped while walking or driving on campus and compelled to

identify themselves, account for their whereabouts, and submit to

physical inspection. In several instances, this questioning was

belligerent in tone, and a number of the students were subjected to

repeated interrogations, at the instigation of different officers.

When this campus-wide operation failed to yield a suspect, the

police cast a still wider net. Over the next five days, from

September 4 to September 9, 1992, police sought to detain for

questioning and physical examination every African-American male

they, could locate in and around the City of Oneonta.3 In several

instances, doing so entailed pulling cars over for no reason (save

for the fact that an occupant was an African-American man), see,

e.g., J .A . at 584-85, 595-96 (second amended complaint at 122-

23, 168-69), and preventing African Americans from boarding buses

at the Oneonta terminal, unless and until they submitted to

questioning and physical inspection, see, e.g., Brown v. City of

Oneonta, 911 F. Supp. 580, 586 (N.D.N.Y 1996). In the end, this

blanket, race-based dragnet fared no better than the on-campus

effort; no suspect was apprehended, nor have any arrests yet been

made in connection with the crime.

3Thus, defendant Chandler, a senior investigator with the

state police told a local newspaper, "We've tried to examine hands

of all the black people in the community." J.A. at 247.

3

In 1993, plaintiffs-appellees-cross-appellants brought this

suit in federal court against the City, County, State, and

University officials who had taken part in the police action, as

well as against the City of Oneonta and the State University,

complaining, inter alia, of violation of their rights under the

Fourth Amendment, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, the "equal benefits" guarantee of 42 U.S.C. § 1981,4

FERPA, and New York state law. Plaintiffs sought certification

under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 of two classes, one consisting of the 78

students whose records had been handed over by the university

officials, the other comprised of the estimated 100 to 300 other

African-American men5 who had been stopped in the course of the

City's five-day sweep.6 The defendants moved for dismissal and for

442 U.S.C. § 1981(a) provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall

have the same right in every State and Territory to make and

enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to

the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the

security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and

to no other.

Because the court below subjected plaintiffs' § 1983 claims based

on violations of the Equal Protection Clause and their § 1981

"equal benefits" claims to essentially the same (mistaken)

analysis, the term "Equal Protection" claims will, unless otherwise

indicated, be used to refer to both the constitutional and the

statutory claim.

5A1 so included was at least one woman. See J.A. at 582-83

(second amended complaint at 1H| 113-17) .

Although the SUCO plaintiffs were certified as a class, the

court below denied certification to the second group, on the ground

that plaintiffs' Fourth Amendment claims did not present

sufficiently common legal and factual questions to warrant class

4

summary judgment on the various claims, asserting, inter alia, that

they were entitled to qualified immunity and that plaintiffs had

failed to make out a claim on which relief could be granted, Fed.

R. Civ. P. 12(b) (6) .

In a series of rulings culminating in the orders from which

this appeal was taken,7 the district court (1) granted summary

judgment on many of the individual Fourth Amendment claims,

(2) ruled that various defendants were not qualifiedly immune from

liability arising from FERPA violations, and (3) dismissed -- as

failing to state a claim, see Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b) (6) -- all

plaintiffs' claims against Oneonta officials alleging violations of

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the

equal benefits guarantee of 42 U.S.C. § 1981.6

certification, see Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b), as their disposition would

in the end depend on the reasonableness of the relation between the

quantum of individualized suspicion and the scope of the restraint

on individual liberty. In a later opinion, the court recognized

that Rule 23 (b) might be satisfied with respect to the Equal

Protection claims of the second class, but declined to revisit the

issue until plaintiffs stated a claim upon which relief could be

granted, Brown v. City of Oneonta, 858 F. Supp. 340, 348 (N D N Y

1994) .

'See Brown v. City of Oneonta, 916 F. Supp. 176 (N.D.N.Y.

1996) ("Brown IV"); Brown v. City of Oneonta, 911 F. Supp. 580

(N.D.N.Y 1996) ("Brown III"). An earlier decision was reported at

858 F. Supp. 340 (N.D.N.Y. 1994) ("Brown II"): the first opinion

relating to the amended complaint ("Brown I") was delivered orally

and is reproduced in the Joint Appendix at 326-362 (Transcript of

Proceedings (Dec. 13, 1993)).

eThe court dismissed the Equal Protection and § 1981 claims

against the City defendants with prejudice, on the ground that even

if plaintiffs amended their complaint so as to state a claim, those

defendants would be entitled to summary judgment, based on the

contents of crime reports they had turned over to plaintiffs.

Because the facts surrounding State defendants' treatment of

"similarly situated" white individuals, see infra, were not known

5

Reasoning that the Equal Protection Clause is "essentially a

direction that all persons similarly situated be treated alike,"

Brown III, 911 F. Supp. at 588 (quoting City of Cleburne v.

Cleburne Living Ctr. , Inc., 473 U.S. 432, 439 (1985)), the district

court held that 12(b)(6) dismissal was warranted because plaintiffs

had failed to allege that a "similarly situated class of non

minorities" had been treated differently in the past (i.e., not

been subject to a city-wide, race-based police dragnet, in response

to a victim's report that the perpetrator of a violent crime had

been a "white male") or that "a group of similarly situated non

minorities even exist[ed]," id.9 On the court's view, the apparent

to the court (the State defendants had not produced their crime

reports), the Equal Protection claims against State officers were

dismissed without prejudice and with leave to amend, Brown III, 911

F . Supp. at 589 .

Although numerous other issues were addressed in the decisions

below, including some -- the FERPA-based claims, for example --

that are before this Court, this brief's focus will be on the Equal

Protection claims.

"While seemingly accepting that there was no precedent for a

race-based sweep involving a suspect described as "white" (and

legally constrained, under Rule 12(b)(6), to accept as true

plaintiffs' allegations that defendants "have not . . . during an

investigation of a crime in which the suspect was a white male,

attempted to seek out every white male in and around Oneonta, New

York," J.A. at 610, 618, 620, 625-26, 627-28, 634, 639 (M 230,

260, 266, 287, 294, 319, 339), the court was unwilling to let the

case go forward, in light of the complete absence from recent

Oneonta crime reports of any references to a "white male" or "young

white male" being sought in connection with a violent crime.

Importantly, the court never determined that white men, in

fact, have never committed (or been suspected of committing)

equally serious crimes, but only that, in the reports it had seen,

"Oneonta police had not categorized the suspects of violent crimes

as white or non white." Nationwide, white offenders account for an

estimated 30-45% of those who commit various types of violent

crime, see, e.g., U.S. Sentencing Comm'n, Annual Report at 45 (1995)

6

non-existence of a sufficiently "similar" non-minority cohort

necessitated concluding, "beyond all doubt," id., that no set of

facts could be established entitling plaintiffs to relief under

§ 1981 or the Fourteenth Amendment, Fe d. R. Civ. P. 12(b) (6) .

Additional inquiry into defendants' racially discriminatory intent

was unnecessary, the court further explained, because proof of a

"bad motive" is "not enough" to establish denial of Equal

Protection. Brown III, 911 F. Supp. at 588 (citing Sector Enters.,

Inc. v. DiPalermo, 779 F. Supp. 236, 247 (N.D.N.Y. 1991)).10

On March 3, 1996, the plaintiffs filed a timely notice of

appeal.11

(table 11), and there is no reason apparent why Oneonta whites

would be an exception to this pattern.

1 “Significantly, the court expressly held, in Brown III, that

a genuine factual issue existed as to whether defendants had acted

with the discriminatory animus required to make out a § 1981 claim.

See 911 F. Supp. at 590 (setting forth facts supporting inference

of discriminatory purpose).

“This case is before this Court on interlocutory appeal from

a "final decision," 28 U.S.C. 1291, denying various defendants

qualified immunity on various claims. See Mitchell v. Forsyth, 472

U.S. 511 (1985). Accordingly, the court need not (and, i n ’some

instances, may not) review all of the rulings of the district

court. This brief will focus principally on the claims of race-

based treatment -- improperly dismissed by the court below -- that

are, for reasons set forth herein, see infra note 13, and in the

Brief of Brown, et al. , properly addressed by the Court at this

stage of the litigation.

7

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The events giving rise to this lawsuit describe an astonishing

instance of official disregard for the basic constitutional right,

secured by the Equal Protection Clause, to be treated by the

government as an individual, rather than as a member of a "suspect"

group defined in overtly racial terms. The failure of the court

below-to perceive the grave constitutional questions presented by

defendants' conduct -- and the jarring conclusion that plaintiffs

could adduce no set of facts entitling them to relief under the

Fourteenth Amendment -- stem from several serious, interrelated

legal errors, each warranting this Court's correction.

The decision below rests on a serious misapprehension of the

substance of the Equal Protection guarantee. The Fourteenth

Amendment vests each person with a right to be treated as an

individual, rather than as a member of a racial group, and limits

governmental use of the "highly suspect tool," City of Richmond v.

J. A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469, 493 (1989), of racial

classification to instances when such resort is narrowly tailored

to the achievement of compelling governmental purposes -- a

restraint that appears to have been flagrantly disregarded by the

governmental defendants in this case. See United States v. Manuel,

992 F .2d 272, 275 (10th Cir. 1993) ("selecting persons for

consensual [police] interviews based solely on race is deserving of

strict scrutiny").

For these reasons, cases under the Equal Protection Clause

teach: (l) that when a governmental policy relies --as the policy

8

challenged here plainly did -- on an express racial classification,

strict judicial scrutiny is triggered, with no further need for

inquiry into discriminatory purpose or effect, see Personnel Adm'r

of Massachusetts v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 272 (1979); Orange Lake

Associates Inc. v. Kirkpatrick, 21 F.3d 1214, 1226-27 (2d Cir.

1994); and (2) that governmental action does not escape scrutiny --

or invalidation -- solely because it can be shown that "similarly

situated" minority and non-minority individuals are subject to the

same (race-based) treatment, see, e.g., Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S.

400 (1991); Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967); Anderson v.

Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964).

The decision below cannot be squared with these core

principles, nor is it even a proper application of the distinct

mode of Equal Protection analysis the district court (erroneously)

presumed should govern -- i.e., that which applies to challenges to

facially neutral (but allegedly racially discriminatory) government

action. While many cases challenging facially neutral government

action do entail identification of a "similarly situated"

nondisadvantaged class, to insist that such an identification is an

indispensable element of any Equal Protection claim is to confuse

a constitutional violation with the ways in which that violation

may be proven. The Supreme Court has left no doubt, however, that

" [p]urposeful discrimination is 'the condition that offends the

Constitution,'" Washington v. Seattle School List. No. 1 , 458

U.S. 457, 484 (1982) (quoting Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ. , 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971)), and that invidious purpose may be

9

proved in myriad ways, Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266-68 (1977). See generally Miller v.

Johnson, 132 L. Ed. 2d 762, 777-78 (1995) (clarifying that odd

district shape is neither "a necessary element" nor a "threshold

requirement" -- but "rather . . . persuasive circumstantial

evidence" of an Equal Protection violation in legislative

apportionment cases).

Were the reasoning of the decision below to prevail, by

contrast, racially motivated governmental action that is

unprecedented or sui generis would be wholly immune from Equal

Protection scrutiny -- even when a plaintiff could adduce direct

evidence of discriminatory intent. Such a legal regime would be

constitutionally intolerable, and it would be contrary to the

practice, see City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358

(1975), and express teaching, see Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at

266 n.14, of the Supreme Court.

Finally, the decision below is also at odds with a substantial

body of established law that bridges the Fourth and Fourteenth

Amendments, governing the role that racial classifications

may constitutionally play in governmental decisions and the

standards for reviewing race-conscious action. Although

consideration of race is not treated as illegitimate per se, see

Adarand v. Pena, 132 L. Ed. 2d 158 (1995) (Fourteenth Amendment),

Shaw v. Reno, 125 L. Ed. 2d 511, 525 (1993) (same); United States

v. Bngnoni-Ponce, 422 U.S. 873 (1975) (Fourth Amendment), it is

established that race "standing alone," id. at 887, cannot supply

10

the "reasonable suspicion" that the Fourth Amendment requires to

justify even the minimal intrusion entailed by an investigative

stop, United States v. Ceballos, 684 F.2d 177, 186 (2d Cir. 1981),

just as it has been held that peculiarly close Equal Protection

scrutiny is required when race is the "sole criterion" -- rather

than one of many -- in other governmental decisions. See Regents

of University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 317 (1978)

(Opinion of Powell, J.); see also United States v. Travis, 62 F.3d

170, 173 (6th Cir. 1995) (consensual searches "initiated solely

based on racial considerations" may violate Equal Protection

Clause) (emphasis supplied).

The reasons for the skepticism -- expressed in a consistent

line of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence -- about the use of race in

law enforcement mirror those articulated in the Equal Protection

setting -- i.e., that race is an untrustworthy proxy for individual

characteristics and one whose use risks serious societal and

individual harm. Each deficiency is implicated to a substantial

degree in this case.12 It would simply be unacceptable to apply

to this case involving racial discrimination against African

Americans a standard of judicial review less vigilant than the one

that the Supreme Court has held in "reverse-discrimination" cases

governs benign racial classifications fashioned to assist African

12Here, if police interrogated only 200 African-American men

(a conservative estimate) , the fact remains that each individual

was accosted -- and treated as if he were a suspect -- despite an

objective, 99.5% (100% - 1/200) certainty that he was not involved

m the crime under investigation. It is not easy to imagine

another characteristic having so little probative value and so

great an effect on police behavior.

11

Americans and other minorities counter the effects of past and

present discrimination. See Adarand, 132 L. Ed. 2d at 180

(emphasizing need for "consistency" in Equal Protection

adjudication); Miller, 132 L. Ed. 2d at 790 (O'Connor, J.(

concurring) (stressing that "the driving force behind the adoption

of the Fourteenth Amendment was the desire to end legal

discrimination against blacks").

ARGUMENT13

I. The Decision Below Rests on a Basic Misapprehension

of Equal Protection Law: Express Racial Classifications

Always Require Close Judicial Scrutiny

By its singular focus on the existence vel non of a "similarly

situated" class of nonminority citizens, the decision below strayed

fatefully from the Equal Protection principles that should control

the analysis (and ultimate disposition) of this case. The primary

error of the decision below is its failure to acknowledge the

existence of three analytically distinct claims under the Equal

Protection Clause: (1) a claim that governmental action

“ Chiefly for the reasons stated in the Brief for Plaintiffs-

Appellees- Cross-Appellants Brown, et al. , it is clear that the

dismissal of the Fourteenth Amendment and § 1981 claims are

properly before this Court. The State defendants have expressly

appealed from the lower court decision denying them qualified

immunity on these claims, see Br. of Defendant-Appellants at 38-42,

and they themselves acknowledge the rule that "a necessary

concomitant to the determination of whether the constitutional

right asserted by a plaintiff is 'clearly established' at the time

the defendant acted is the determination of whether the plaintiff

has asserted a violation of a constitutional right at all "

Siegert v. Gilley, 500 U.S. 226, 232 (1991). That question, of

course, is "inextricably intertwined," see Kaluczky v. City of

White Plains, 57 F.3d 202, 206-07 (2d Cir. 1995), with the

determination whether plaintiffs' (identical) allegations against

the City defendants state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

See also Blue v. Koren, 72 F.3d 1075, 1084 (2d Cir. 1995).

12

unjustifiably incorporates a racial classification; (2) the quite

different assertion that governmental action race-neutral on its

face was, in fact, invidiously motivated; and (3) the claim that a

governmental action, though not based on a suspect classification,

is nonetheless invalid as unrelated to a legitimate governmental

interest, see City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr., Inc., 473

U.S. 432 (1985). See generally Orange Lake Associates, Inc. v.

Kirkpatrick, 21 F.3d 1214, 1226-27 (2d Cir. 1994) (discussing

standards of judicial review for these different claims).14

These claims implicate fundamentally different regimes of

Equal Protection analysis, requiring different modes of proof. The

second category requires a plaintiff to show the presence of

"purposeful discrimination," through "such circumstantial and

direct evidence of intent as may be available," Arlington Heights,

429 U.S. at 266, -- a category that includes, but is not limited

to, evidence, like that so avidly sought by the court below, of an

actual "similarly situated," yet differently treated, class, see

infra. However, an explicit racial classification is "immediately

suspect," Shaw, 125 L. Ed. 2d at 526 (emphasis supplied),

triggering "detailed examination, both as to ends and as to means,"

14In fact, Equal Protection jurisprudence acknowledges still

another "rare," Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266, category,

between the first and second: cases in which a "neutral"

classification is plainly a "pretext" for an impermissible one,

e.g., Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) (grandfather

clause voting requirement), or where its impact is so "stark" as to

be "unexplainable on grounds other than race." Arlington Heights,

429 U.S. at 266. Such hybrids are treated as equivalent to express

racial classifications and are subject to immediate, strict

scrutiny, see Feeney, 442 U.S. at 272.

13

Adarand, 132 L. Ed. 2d at 188. Such a classification may be

invalidated without any allegation of impermissible motive and may

be upheld only when shown to be narrowly tailored to serve a

compelling governmental interest. Shaw, 125 L. Ed. 2d at 525-26.

This highly "skeptical" approach to express racial

classifications itself rests on a basic principle of Equal

Protection jurisprudence: that the Fourteenth Amendment not only

guarantees equal treatment by the government, it also secures a

right to be treated as an individual -- and not "simply [as a]

component[] of a racial . . . class" Miller, 132 L. Ed. 2d at 776

(internal quotation marks omitted); see generally Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 22 (1948) (the "rights created by the first

section of the Fourteenth Amendment are . . . guaranteed to the

individual"). This requirement, the Supreme Court recently

affirmed, is "at the heart of the Constitution's guarantee of equal

protection," Miller, 132 L. Ed. 2d at 776, and its claimed

violation is "analytically distinct," Shaw, 125 L. Ed. 2d at 532,

from any assertion that "similarly situated" members of one race

are being treated better -- or worse -- than any other. Accord

Croson, 488 U.S. at 493 (Fourteenth Amendment's promise of "equal

dignity and respect" is always "implicated by a rigid rule erecting

race as the sole criterion in an aspect of public decisionmaking") ;

Bakke, 438 U.S. at 299 (Powell, J.) (when a governmental act

"touch[es] upon an individual's race or ethnic background, he is

entitled to a judicial determination that the burden he is asked to

bear on that basis is precisely tailored to serve a compelling

14

governmental interest").

These precepts -- wholly neglected in the decisions of the

court below -- yield an important corollary, bearing directly on

this case: race-based governmental action does not become

constitutionally impregnable solely "because members of all races

are subject to like treatment." Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400, 410

(1990) .15 Thus, though the court below was quite right to believe

Equal Protection would be denied by a statute (or policy)

authorizing police to accost all black men whenever a violent crime

is alleged to have been committed by a black man (but precluding

similar treatment of whites when a white is the suspect), it went

quite wrong in assuming that a statute providing for wholesale,

race-based suspicion on an "even-handed" basis would raise no

serious constitutional difficulty. This notion, that the

constitutionality of race-based treatment of innocent African-

American individuals could be salvaged if innocent whites were also

subject to race-based treatment, "has no place in . . . modern

equal protection jurisprudence," Powers, 499 U.S. at 410.16

15In Powers, the Court refused to exempt from Equal Protection

scrutiny race-based peremptory challenges, despite a recognition

that black and white venirepersons would both be subjected to race-

based treatment. Similarly, in Shaw v. Reno, the majority squarely

rejected the argument, pressed vigorously in dissent, that Equal

Protection harm is limited to cases where one racial group's voting

power is diluted (i.e., given less weight than the votes of

similarly situated members of another group), explaining that

"classifying citizens by race . . . threatens special harms that

are not present in our vote-dilution cases. It therefore warrants

different analysis." Shaw, 125 L. Ed. 2d at 530.

16See also Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399, 403-04 (1964)

(refusing to accept that statute mandating that candidates' race be

printed on the ballot was "nondiscriminatory" simply "because

15

There is no basis in logic -- and no support in the case law

-- for requiring proof regarding "similarly situated" individuals

when a racial classification (or governmental action "unexplainable

in terms other than race") is alleged. On the contrary, when such

a classification is complained of, the governmental defendant

"immediately," Shaw, 125 L. Ed. 2d at 526, must come forward with

a justification for the race-based action. The disposition of Hall

v. Pennsylvania State Police, 570 F.2d 86 (3d Cir. 1978), is

instructive: there, the Third Circuit reinstated a § 1981

complaint challenging a police notice that banks should photograph

"suspicious looking black persons," with no suggestion that the

policy's legality would depend on whether or to what extent non

blacks committed bank robberies. Accord United States v. Travis,

62 F .3d 170, 174 (6th Cir. 1995) ("Once [a criminal] defendant has

produced some factual or statistical evidence, the officers must

then produce evidence that contradicts defendant's claim that they

acted solely on racial considerations, or identify a compelling

interest for the race-based interviews") ; cf. also United States v.

it applie[d] equally to Negro and white") ; Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1, 8 (1967) (rejecting State's contention "that, because

its miscegenation statutes punish equally both the white and the

Negro participants in an interracial marriage, these statutes,

despite their reliance on racial classifications, do not constitute

an invidious discrimination").

On the district court's reasoning, a policy requiring police

to question every white or black person who is seen in a

neighborhood predominately inhabited by "other-race" individuals

not only would be constitutionally untroublesome -- it would be

immune from challenge. But cf. People v. Bower, 24 Cal . 3d 638, 597

P • 2d 115, 119 (1979) ("the fact that appellant was a white man

[seen by an officer in a predominantly black neighborhood] could

raise no reasonable suspicion of crime").

16

Laymon, 730 F. Supp. 332, 339 (D. Colo. 1990) (Fourth and

Fourteenth Amendments violated when "irrefutable evidence" -- which

did not include rates at which white and minority drivers commit

traffic violations -- showed officer made traffic stops "primarily

based on out-of-state license plates and the driver's race or

ethnicity").

II. Identification of a Similarly Situated,

But Differently Treated, Nonminority Class Is Merely

One Way Among Many of Proving Racial Discrimination,

in Violation of the Equal Protection Clause

Moreover, even if one accepted the district court's erroneous

disregard for the distinction between (inherently suspect) express

racial classifications and facially "neutral" -- but allegedly

discriminatory -- governmental action, the decision below could not

be upheld even as an application of the latter, more common mode of

Equal Protection inquiry. The second crucial flaw in the district

court's Equal Protection analysis is its confusion of what is

sufficient to make out a claim of discrimination under the Equal

Protection Clause with what is necessary: although a race-neutral

policy of police detention and interrogation might be shown to

violate the Equal Protection Clause by proof that it "bears more

heavily" on African Americans than on whites, Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976), the Constitution does not insist that a

denial of Equal Protection must be shown that way. Instead, the

Supreme Court has taught that " [P]urposeful discrimination is 'the

17

condition that offends the Constitution,'"17 Seattle School Dist.,

458 U.S. at 484, cautioning that "[i]t is the presumed racial

purpose of . . . state action, not its stark manifestation, that

[is] the constitutional violation." Miller, 132 L. Ed. 2d at 778;

see also id. at 777 (clarifying that odd district shape is neither

"a necessary element" nor a "threshold requirement" -- but rather

"may be persuasive circumstantial evidence" of an Equal Protection

violation in apportionment).

In Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. at 242, the Court, while

acknowledging that impact evidence of the sort sought by the

district court in this case "is not irrelevant," id., to the

ultimate constitutional question, held that it is not the "sole

touchstone of an invidious discrimination," id., either. See

Orange Lake Associates, Inc., 21 F.3d at 1226-27 (applying Davis) .

And in Arlington Heights, the Court undertook to canvas some of the

other kinds of evidence that might bear on the Equal Protection

inquiry. These included:

The historical background of the decision . . . , particularly

if it reveals a series of official actions taken for invidious

purposes. . . . The specific sequence of events leading up to

the challenged decision [,] . . . [d]epartures from the normal

procedural sequence [,] . . . [s]ubstantive departures],]

[t]he legislative or administrative history . . . , especially

It is important to stress that while "discriminatory purpose"

is, in the absence of an express classification, a prerequisite for

an Equal Protection claim, antipathy is not. See City of Los

Angeles v. Garza, 918 F.2d 763, 778 (9th Cir. 1990) (Kozinski, J.,

concurring) . Accord Bray v. Alexandria Women's Health Clinic', 122

L. Ed. 2d 34, 46 (1993) ("animus" required by 42 U.S.C. § 1985does

not imply "malicious [] motivat[ion]," only "a purpose that focuses

upon women by reason of their sex") (emphasis omitted).

18

where there are contemporary statements by members of the

decisionmaking body, minutes of its meetings, or reports.

429 U.S. at 267-68. Even this catalogue, however, the Court took

care to underscore, did not "purport [] to be [an] exhaustive

[summary of the] subjects of proper inquiry in determining whether

racially discriminatory intent existed." Id. at 268. See also

Miller, 132 L. Ed. 2d at 779 (Equal Protection violation is made

out in apportionment case "either through circumstantial evidence

. . . or through more direct evidence going to purpose") (emphasis

supplied).

The recognized need for flexibility in proof of discrimination

has been illustrated in the vast case law pertaining to violations

of the Equal Protection Clause and other laws forbidding

discrimination on the basis of a suspect classification. Arlington

Heights itself gave no indication that plaintiffs' claim should

stand or fall depending whether a zoning variance similar to the

one denied in that case had ever been granted under "similar"

circumstances, and in Yusef v. Vassar College, 35 F.3d 709, 715 (2d

Cir. 1994), this Court reinstated a complaint alleging gender

discrimination in violation of Title IX, based on the male

plaintiff's allegations that: (1) every man accused of sexual

harassment had been found culpable by a college disciplinary

tribunal; and (2) the tribunal's proceedings were marred by

irregularities. Nowhere did the Court suggest that the claim was

doomed for failure to allege that "similarly situated" females were

escaping similar punishment or that "a group of similarly situated

19

non-[males] even exist [ed] . 1,18 Employment discrimination cases

universally recognize that regardless whether there is

circumstantial evidence of discrimination such as better treatment

of similarly situated non-minority employees, liability can always

be established by "direct evidence" of a discriminatory

classification. See, e.g., Talley■ v. Bravo Pitino Restaurant,

Ltd., -61 F .3d 1241, 1246-48 (6th Cir. 1995); Trans World Airlines,

Inc. v. Thurston, 469 U.S. Ill, 121-22 (1985). Cf. U.S. Postal

Service v. Aikens, 460 U.S. 711, 713 & n.3 (1983) (in Title VII

case, ultimate fact of "discrimination vel non" may be proved "by

direct or circumstantial evidence").16 * * 19

A rule mandating identification of a "similarly situated,"

differently treated, class in every Equal Protection case,

moreover, would have the constitutionally intolerable effect of

immunizing from judicial scrutiny any governmental action that is

unique or without precedent. On the rationale of the decision

below, a complaint challenging internment of Japanese-Americans

might well founder for a plaintiff's inability to identify a

16Albert v. Carovano, 851 F.2d 561 (2d Cir. 1988) (en banc)

presented a very different factual scenario. There, the

plaintiffs' claims of race-based and disparate treatment were

undermined by their own complaint, which suggested that some

students were disciplined for reasons not prohibited by § 1981 and

that non-minority individuals -- certain of the plaintiffs -- were

given precisely the same punishment for the same offense,

foreclosing any claim that a racial classification had been

employed. Id. at 572.

19In the employment discrimination setting, courts have

expressly rejected the suggestion that a plaintiff's failure to

allege that she was "as or more qualified" than the person hired

warrants granting a motion to dismiss. See Mitchell v. Baldridqe

759 F.2d 80 (D.C. Cir. 1985) (R.B. Ginsburg, J .).

20

national emergency comparable to World War II,20 and a challenge

to a one-time municipal annexation would similarly founder for

failure to identify a sufficiently "comparable" move, but see City

of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358, 378 (1975) ("An

official action, whether an annexation or otherwise, taken for the

purpose of discriminating against Negroes on account of their race

has no legitimacy at all under our Constitution") . Indeed, the

Arlington Heights decision recognized as much:

[A] consistent pattern of official racial discrimination is

[not] a necessary predicate to a violation of the Equal

Protection Clause. A single invidiously discriminatory

governmental act . . . would not necessarily be immunized by

the absence of such discrimination in the making of other

comparable decisions.

429 U.S. at 266 n.14.

As the foregoing makes clear, the concern of the Equal

Protection Clause extends not only to whether a similarly situated

class has been treated differently in the past -- i.e., as a matter

of historical fact -- but also to whether the government would have

treated the plaintiff differently had he not been a member of the

racial minority. (Even then, of course, "even-handed" but unduly

race-based treatment would be unconstitutional, see supra page 15

2°But cf. Adarand, 132 L. Ed 2d at 188 (emphasizing that

constitutional scrutiny in Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214

(1944), was insufficiently aggressive). Even an allegation of

failure to intern German-Americans might not save the complaint, as

a court could decide, reasoning along the lines of the district

court in this case, that the acts of espionage attributed to (the

few disloyal) German- or Italian-Americans were not as serious as

were the crimes blamed on (the few disloyal) Japanese-Americans.

Dismissal on that basis (like the dismissal decision below) would

treat as irrelevant: (1) whether the decision was motivated by

animus, and (2) whether the race-based internment of all was a

permissible response to the disloyalties of a few individuals.

21

(discussing Powers v. Ohio), hut see Samaad v. City of Dallas, 940

F.2d 925 (5th Cir. 1991) .21) Although such a showing is typically

more difficult to make out when there is no historical record

making clear that treatment was race-based -- and "conclusory

allegations" of animus alone are not enough -- there is no sanction

in the Fourteenth Amendment or the Federal Rules for barring the

courtroom door to plaintiffs making other sorts of allegations --

involving prior discriminatory conduct, direct admissions, or

telling departures from ordinary practices -- that would support an

21 In Samaad, which was cited by the court below, the Fifth

Circuit held that plaintiffs -- who objected to the operation of a

motor race track in their (predominantly black) neighborhood, would

not show an Equal Protection violation even if they proved that

(1) governmental actors had "discriminatory animus," 940 F.2d at

942, and (2) government officials would not have allowed

objectionably loud races had the neighborhood been mostly white.

The Fifth Circuit's conclusion, that "such conduct, however

offensive, would not violate the Equal Protection Clause," id. at

941, cannot be reconciled with common sense -- or with the

controlling Supreme Court precedent -- discussed supra.

The inquiry into what officials "would have" done is hardly as

exotic as the Fifth Circuit's opinion in Samaad might suggest: to

the contrary, the "hypothetical" question whether a defendant would

have taken the same action absent discriminatory motive is a staple

of Fourteenth Amendment analysis. See Arlington Heights, 429 U S

at 270 & n . 20 .

Not only is the analytical framework adopted by the court

below indistinguishable from the sort of "heightened pleading

standard" for civil rights actions that the Supreme Court held, in

Leatherman v. Tarrant County, 122 L. Ed 2d 517 (1993) , federal

courts are without authority to impose, but, as a substantive

matter, its criteria are poor choices for screening out

nonmeritorious claims. See Siegert v. Gilley,, 500 U.S. at 236

(Kennedy, J., concurring) (pleading standard is wrong to demand

direct, as opposed to circumstantial, evidence). That said, a fair

reading of the complaint in this case (not to mention the generous

one that Rule 12(b)(6) requires) suggests that plaintiffs here have

cleared the unauthorized, unduly high, and arbitrary threshold the

district court erected.

22

inference of discriminatory treatment.22

The fact-pattern of this case should itself have sufficed to

suggest the defectiveness of the district court's approach: either

(1) Oneonta whites never have, in fact, committed violent crimes

-- in which case, under the court's rationale, the Equal Protection

Clause imposes no limit whatsoever on the action that may be taken

against law-abiding black citizens (until a white does commit such

a crime) --or (2) whites have committed violent crimes, but police

simply would not record a description if the only information

available were that the suspect was a "young white male," in which

case matters would be even worse. Then, a practice that denied

Equal Protection (i.e., similar treatment to similarly situated

individuals) on even the narrow understanding of the court below

would persist in perpetuity, without any opportunity for those

mistreated even to state an Equal Protection claim.

The more comprehensive Equal Protection inquiry that precedent

requires, by contrast, demands a less grudging look at plaintiffs'

allegations and the context in which they arise. First, they have

22In this case, for example, it is apparent that the police

officers flouted the duty, imposed by the New York Constitution,

not to approach innocent individuals absent a "founded suspicion of

individual involvement in criminal activity," see People v

Hollman, 79 N.Y.2d 181, 581 N.Y.S.2d 619 (1992). This deviation

from a state-law norm when black individuals are involved is

significant not because the Equal Protection Clause "incorporates"

state law in any sense, but rather because it is probative of race-

based treatment. This precise point was made by Justice O'Connor

in Miller v. Johnson, where she emphasized that compactness and a

state's other "traditional districting principles," though plainly

not compelled by the federal Constitution, are nonetheless relevant

(when departed from) in Equal Protection analysis. See 132 L Ed

2d at 790.

23

alleged that there is no precedent in Oneonta for a whites-only

police sweep, meaning that, to the extent that there has been a

similar offense committed by a white man (but not reported as

such), their claim would satisfy the supercharged notion of what

Equal Protection requires that was adopted by the court below. See

Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69, 73 (1984) (complaint should

be dismissed "only if it is clear that no relief could be granted

under any set of facts that could be proved consistent with the

allegations") . Even, however, if Oneonta white men actually are a

singularly non-violent lot, the absence of any known precedent, in

jurisdictions where white people are known to commit violent

crimes, for such a "sweep" casts some doubt on the possibility that

Oneonta stands alone in adhering to an "even-handed" race-based

sweep policy. Finally some significance should attach to the fact

that defendants have never represented (for good reason) that they

do, in fact, follow such a policy, i.e., that they will, in the

future, respond to a "young white male" violent crime report in the

same manner they reacted here, cf. Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at

270 (discussing burden on defendant to show that it would have

taken steps absent discrimination). In fact, defendants' policy

for future white suspects (or, more precisely, for innocent white

people when a white suspect is sought) almost surely is the one

that the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments counsel, see infra: no

race-based sweeps. On any understanding, Equal Protection should

24

entitle law-abiding African Americans to nothing less.23

III. Requiring Identification of a "Similarly Situated" Class

Is Plainly Inappropriate in Cases Involving Racial Discrimination

The third Equal Protection error of the decision below was its

failure to acknowledge the fundamental divide in Equal Protection

23The Supreme Court's recent decision in United States v.

Armstrong, No. 95-157, 64 U.S.L.W. 4305 (May 13, 1996), cannot be

read as supporting the decision below. Armstrong dealt with the

issue of when a criminal defendant claiming "selective prosecution"

is entitled to discovery against the government, and the Court's

opinion heavily stresses this special context -- in which a

"presumption that a prosecutor has not violated equal protection,"

can be overcome only by "clear evidence to the contrary." 64

U.S.L.W. at 4308. This "hestitan[ce] to examine the decision

whether to prosecute," the Court has explained, is rooted in (1)

separation of powers concerns; (2) the "relative competence of

prosecutors and courts" to determine whether a case should be

brought; and (3) the societal costs of proceedings collateral to

criminal prosecutions (including the possibility that a guilty --

if unfairly selected -- criminal will be let free) . Id. These

concerns are totally absent in the instant case, which involves

actions that, unlike prosecutions, do not require independent

determinations of "probable cause" and involve officials who are

not, like prosecutors, sworn officers of the court, subject to

sanction for unethical conduct. Compare Imbler v. Pachtman, 424

U.S. 409 (1976) (prosecutors enjoy absolute immunity), with Malley

v. Briggs, 475 U.S. 335 (1986) (rejecting claim that police

officers should enjoy absolute, rather than qualified, immunity in

certain situations).

The Armstrong Court in no way suggested that it was departing

from settled rules for analyzing practices that rely on express

racial classifications, and the opinion explicitly acknowledges

that a different rule might apply in cases (like this one)

"involving direct . . .[evidence] of discriminatory purpose." Id.

Finally, the Court noted that the very term "selective prosecution"

implies that a selection has taken place," meaning that a person

making such an allegation is, of necessity, asserting that

similarly situated individuals exist. Whatever showing might

fairly be required of such a claimant -- in the context of a

discovery request collateral to his own prosecution -- has little,

if any, relevance to other Equal Protection claims, where

"selectivity" is not asserted (or even relevant) , see, e.g.

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964). Cf. Gehl Corp. v. Roby,

63 F.3d 1528, 1539 (10th Cir. 1995) (summary judgment appropriate

on selective prosecution claim, when probable cause existed to

indict plaintiff but not other fundraisers).

25

doctrine between claims of discrimination on the basis of race and

other "suspect classifications," and other non-"suspect" bases for

disparate treatment. See, e.g., Williamson v. Lee Optical, 348

U.S. 483 (1955)(upholding different treatment of opticians and

optometrists). The few authorities cited below in support of a

"similarly situated" requirement fall, for the most part, into this

latter category, but see supra note 21 (discussing Samaad v. City

of Dallas, 940 F.2d 925 (5th Cir. 1991) ) . Yale Auto Parts v.

Johnson, 758 F.2d 54 (2d Cir. 1985), for example, involved a

business owner's challenge to a denial of his application for a

zoning variance; the plaintiff made no claim of race or other

class-based discrimination, but rather complained that the decision

had been arbitrary and politically motivated. Noting that

plaintiffs had not alleged "discriminatory purpose or conduct,"

- -e •, that city officials "had intentionally treated their

application differently from other similar applications," id. at

61, the Court upheld dismissal under Rule 12(b)(6). Likewise, the

plaintiffs in Sector Enterprises, state government employees whose

opportunities for outside employment were restricted by conflict-

of-interest policies, appear to have alleged no basis (suspect or

not) -- apart from a generic assertion of "bad faith" -- for their

allegedly unfair treatment. Sector Enters., Inc. v. DiPalermo, 779

F. Supp. 236, 247 (N.D.N.Y. 1991) . See generally Orange Lake

Associates, 21 F.3d at 1227 ("To establish a claim of intentional

discrimination under [a] classification [subject to rational basis

review, plaintiff] must allege that similarly situated individuals

26

have been treated differently").

To claim that a governmental action "discriminates" in

violation of the Equal Protection Clause on a basis other than

race, ethnicity, religion or another basis held constitutionally

suspect is a daunting prospect. Such actions arrive in court

"bearing a strong presumption of validity," FCC v. Beach

Communications, Inc., 124 L. Ed. 2d 211, 222 (1993), and to

succeed, a plaintiff challenging differential treatment not alleged

to be grounded on a suspect classification must "negative every

conceivable basis" which might support it, id. (quoting Lehnhausen

v. Lake Shore Auto Parts Co., 410 U.S. 356, 364 (1973)). Thus,

while courts recognize the "inevitab [ility] . . . that some persons

who have an almost equally strong claim to favored treatment [will]

be placed on different sides of the line," principles of judicial

restraint require that "initial discretion" to decide whether

individuals are "'different' . . . or 'the same' resides"

[with] the States," Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 216 (1982), and --

unless an "invidious basis" for different treatment is claimed --

such judgments are "virtually unreviewable," Beach Communications,

124 L. Ed. 2d at 223.24 Precisely because courts must be so

deferential to governmental classifications -- and because the

24See generally Plyler, 457 U.S. at 216 ("A legislature must

have substantial latitude to establish classifications that roughly

approximate the nature of the problem perceived, that accommodate

competing concerns both public and private, and that account for

limitations on the practical ability of the State to remedy every

ill"); see also U.S. Railroad Board v. Fritz, 457 U.S. 202, 216

(1982) ("[T]he fact [that] the line might have been drawn

differently at some points is a matter for legislative, rather than

judicial, consideration").

27

plaintiff's burden of disproving all conceivable grounds for his

treatment is so weighty -- it is not inappropriate, in the typical

cases, to demand that the plaintiff identify a similarly --or even

nearly identically -- situated class or individual.25 But even if

that requirement is properly imposed at the pleading stage in such

a case, cf. Orange Lake Assocs., it plainly has no place there when

the plaintiff complains of unequally -- or unduly -- race-based

treatment.

But even were the Court to read its cases as requiring

identification of a "similar situation," finally, any such

prerequisite was satisfied here. Although the district court

referred to plaintiffs as "suspects," the class of individuals to

whom they are similarly situated for Equal Protection purposes are

not white "suspects," but rather individual white citizens, bearing

no objective indicia of criminality, who happen to walk the public

streets of Oneonta in the days after a crime had been committed.

Of course, defendants might yet be able to escape liability if the

court were persuaded that dissimilar treatment meted out to these

individuals was warranted, because: (a) a crime had recently

"’The suggestion below that "bad motive is not enough" to prove

an Equal Protection violation is demonstrably false when race-base

treatment is alleged, and is of uncertain validity even in cases

involving other, non-suspect classifications. There is authority

suggesting that the Equal Protection duty of impartial governance

can be breached by an extreme instance of individual oppression,

see Esmail v. Macrane, 53 F.3d 176 (7th Cir. 1995), and that "a

bare desire to harm a politically unpopular group," Department of

Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U.S. 528, 534 (1973), cannot supply a

"legitimate governmental interest," even under deferential

"rational basis review," accord Romer v. Evans, No. 94-1039 1996

U.S. LEXIS 3245 (May 20, 1996).

28

(allegedly) been committed by an African American; (b) the crime

was sufficiently more serious than others to explain disparities in

police response; and (c) the government's interests were

sufficiently weighty (and its race-neutral alternatives

sufficiently unappetizing) to justify (a) resort to race-based

measures generally, and (b) the sweeping measures actually adopted.

But such considerations would simply go to liability -- not to

whether plaintiffs' allegations state a claim for relief.

IV. The Complaint Alleges Governmental Conduct Violative of

Rights Clearly Established Under the Fourth

and Fourteenth Amendments

Although the actions here are challenged as violating two

distinct constitutional protections -- the Fourteenth Amendment

Equal Protection guarantee and the freedom from unwarranted

government intrusions on liberty secured by the Fourth Amendment,

this case arises at a point of substantial doctrinal convergence.26

With respect to the role that race permissibly may play in

government decision-making, the case law under both Amendments is

consistent: while the government is not denied all power to take

26It is not at all unusual, of course, for governmental conduct

to violate two distinct constitutional provisions . Loving v.

Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), in which the Virginia anti

miscegenation law was invalidated both as a denial of Equal

Protection and as an infringement of the Due Process right to

marry, is a paradigmatic example. Cf. McFarland v. Smith, 611 F.2d

414, 416 (2d Cir. 1979) ("when race prejudice is injected into a

criminal trial, the due process and equal protection clauses

overlap or at least meet") (citation omitted). In this case, the

Fourth Amendment has been interpreted as regulating only the

government's conduct toward those individuals whose liberty of

movement is sufficiently restrained to constitute a "seizure."

Plaintiffs in this case who are found to have been seized are

entitled to relief under both the Equal Protection and the Fourth

Amendment claims.

29

race into account, Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U.S. at 887; Adarand, 132 L.

ed. 2d 158 (1995); McFarland v. Smith, 611 F.2d 414, 417 (2d Cir.

1979) (not "every race-conscious argument [by an attorney] is

impermissible"), it must do so carefully and within definite,

judicially enforceable bounds. Thus, a person's race "standing

alone," Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U.S. at 887, may never supply the

government with the requisite individual suspicion the Fourth

Amendment requires for even the "minimal intrusion" entailed by an

investigatory stop, just as a "rigid rule erecting race as the sole

criterion in an[y other] aspect of public decisionmaking," Croson,

488 U.S. at 493, will be subject to "detailed judicial inquiry,"

Adarand, 132 L. ed. 2d at 182, with the person affected entitled to

a "determination that the burden he is asked to bear on that basis

is precisely tailored to serve a compelling governmental interest,"

Bakke, 438 U.S. at 299 (Powell, J.). See generally United States

v. Travis, 62 F.3d at 173 ("We hold that consensual searches may

violate the Equal Protection Clause when they are initiated solely

based on racial considerations"); United States v. Manuel, 992 F.2d

272, 275 (10th Cir. 1993) ("selecting persons for consensual

[police] interviews based solely on race is deserving of strict

scrutiny"); McFarland, 611 F.2d at 416 (prosecutor's reference to

race of defendant violated his Fourteenth Amendment rights because

"race is an impermissible basis for any adverse governmental action

in the absence of compelling justification").27

2 Accord, e.g., United States v. Lopez-Martinez, 25 F.3d 1481,

1486 (10th Cir. 1994)(Hispanic ancestry of passengers in car near

border "could not, by itself, create the reasonable suspicion

30

required under the Fourth Amendment"); United States v. Beck, 602

F.2d 726, 727 (5th Cir. 1979); United States v. Bautista, 684 F.2d

1286, 1289 (9th Cir. 1982) ("race or color alone is not a

sufficient basis for making an investigatory stop"); United States

v. Williams, 714 F.2d 777, 780 (8th Cir. 1983) ("Police cannot have

grounds for suspicion based solely on the race of the suspect");

United States v. Nicholas, 448 F.2d 622, 624 (8th Cir. 1971)

("momentary detention of citizen" unsupported by "generalized

suspicion that any black person driving an auto with out-of-state

license plates might be engaged in criminal activity"); United

States v. Laymon, 730 F. Supp. 332, 339 (D. Colo. 1990).

Of course, racial classifications used by law enforcement

officials are as subject to strict scrutiny as are any other, see,

e.g., Manuel, 992 F.2d 272; Travis, 62 F.3d 170; Hall, 570 F.2d 86;

see also Adarand, 132 L. Ed. 2d at 182 ("courts should take a

skeptical view of all governmental racial classification")

(emphasis supplied); McFarland, 611 F.2d at 417 (prosecutor's

reference to defendant's race "must be justified by a compelling

state interest"). Indeed, the Court first formulated the "strict

scrutiny" standard in Korematsu, a case arising from a criminal

prosecution for violating a military order during time of war.

Equal Protection standards have been held fully applicable in

contexts that are as or more sensitive, see, e.g., Miller, 132 L.

Ed. 2d at 779 (recognizing that review of districting legislation

is "a serious intrusion into the most vital of local functions");

Palmore v. Sidoti, 466 U.S. 429, 433 (1984) (overturning race-based

child custody award, in the face of State's "substantial" interest

in "granting custody based on the best interests of the child").